Excluded from public financial aid because of their immigration status, undocumented youth in the United States frequently depend on private schools’ merit-based financial aid. This aid, which operates according to a neoliberal logic, provides them with a critical pathway to tertiary education and potentially to institutional and national inclusion. Yet this private-sector inclusion ultimately harms their sense of public belonging, as shown by the experiences of undocumented Latino youth in Nashville, Tennessee. Students who cannot meet the schools’ high standards cannot access either institutional or civic inclusion; those who can meet the standards experience inclusion as contingent on continued excellence. Their experiences reveal the critical role that private institutions play in mediating undocumented people’s national inclusion and how neoliberal merit restricts the terms of this inclusion. [undocumented migrants, inclusion, exclusion, higher education, neoliberalism, bureaucratic documents, United States]

Emma was stalling.1 Sitting at a computer, she was finishing up her college application in the cramped office at Succeeders, a preparatory program for achievement in higher education for Latino youth in Nashville, Tennessee.2 She had dutifully logged in to her application, but rather than click Submit, she kept turning away from the blinking cursor to gossip with me and the program coordinator.

As I encouraged her to finish the application, she suddenly began to cry and shared her reasons for stalling. Emma explained that the application presented her with what she wanted: the fun of college, a path toward higher-paying work, and the chance to start “being somebody.” It also confronted her with the fact that college, and the hopes she attached to it, might not work out for one reason: as an undocumented person, she was ineligible to file the Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA), an 108-question form on financial information from tax returns, that is used to determine most students’ financial aid. Her status thus made her ineligible for federal and state aid, as well as many scholarships.3 Like most low-income undocumented youth, Emma could not afford college on her own. She cried because she was afraid of what would happen to her without the money she needed for college.

Emma and her peers link access to higher education with national inclusion. For them, getting into college was a way to mark themselves as worthy of such inclusion at a time when Latinos’ value as members of the nation is politically and publicly questioned (Chavez 2008). This form of inclusion had two connected parts. One was a sense of sociocultural membership, that is, national incorporation through participation in daily civic, social, and cultural life that exists beyond juridical definitions of membership as citizen or noncitizen (cf. Bosniak 2006; Ong 1996; Soysal 1994). The other was a sense of belonging, an “emotional attachment” to and “feeling at home” in the nation and its institutions (Yuval-Davis 2006, 197). Both belonging and sociocultural membership are aspects of civic inclusion that emerge not only from citizenship laws—though, as I show, such laws enduringly shape the terms of civic inclusion—but also from daily experiences, attachments, and participation in institutions, including schools, churches, and workplaces (Abu El-Haj 2015; Coutin 2000; Ho 2009; Gálvez 2010). In practice, institutions become locations for national inclusion.

For youth, educational institutions are a charged location of these modes of inclusion. Young people spend significant time there, making it a critical space in their lives. Moreover, primary and secondary (hereafter, K–12) public schools provide judicially mandated incorporation into a national institution, thus offering a uniquely powerful form of civic inclusion when compared with other institutions (Abrego 2006; Gonzales 2011, 2016).4 Most critically, although US public schools are sites of stratification where students can feel marginalized for many reasons, they are also places where young migrants, including undocumented youth, are and have historically been “invited to ‘become citizens’” (Abu El-Haj 2015, 6). In forging national community through shared practice, schools have been critical to US citizenship and nation building (Abu El-Haj 2015, 5–6; see also Gonzales 2016, 13–15).

K–12 public schools provide opportunities to gain skills, make friends, develop shared cultural practices, and build citizen identities, thereby offering undocumented students like Emma “an experience of inclusion atypical of undocumented adult life” (Gonzales 2011, 608; see also Nicholls 2013). In K–12 education, undocumented students are primed to see themselves not as illegal interlopers but as citizen-students, as part of the nation, because they participate in this key social, and socializing, institution (Gleeson and Gonzales 2012, 5). Furthermore, students learn from teachers and others that academic achievement portends civic inclusion and economic mobility if they succeed in the educational meritocracy (Abrego 2006; Gleeson and Gonzales 2012; Gonzales 2011).5 Unsurprisingly, students hope to maintain this sense of civic inclusion in college, even if they remain formally excluded because of their immigration status (Gonzales 2011, 2016).

Educational institutions are, however, also where “the boundaries of the national imaginary are … contested” (Abu El-Haj 2015, 6). This contestation manifests in students’ college access. For undocumented youth, being denied financial aid means being denied continued access to the civic inclusion they felt in K–12 schools. Fraught encounters with the FAFSA are among the first confrontations youth have with how a juridical citizenship regime that is restrictive excludes them from membership entitlements. While students begin to experience the consequences of undocumented status in other domains (e.g., driver’s licenses), financial aid alerts them to how their undocumented status could exclude them from both education and what it has represented, a privileged site of national inclusion (Gonzales 2011, 603–4). The Succeeders I worked with believed that higher education could maintain the national inclusion they gained in K–12 contexts and were losing in others. Leaving school meant civic exclusion, hastening the “transition to illegality” (Gonzales 2011, 605; Gonzales and Chavez 2012). Emma’s tears and her application, with its missing FAFSA, physically manifested her fear of losing school and being civically excluded.

Weeks later, Emma was admitted to Baldwin—a private, Christian college. The question of money reemerged, but potentially with a solution. As a private school, Baldwin is free from determining financial aid exclusively through the FAFSA, and it awards aid to high-achieving undocumented students like Emma for academic merit. Emma’s excellent score of 27 on the ACT, a standardized entrance exam in the United States, made her eligible for enough merit aid to enroll, feel proud, and belong. In the aid process, Emma made a budget using the Presupuesto, an alternative financial-planning document from Succeeders. This document was critical to her participation in a private aid process that marked her, to herself and admissions gatekeepers, as the right kind of meritocratic student and citizen.

Emma’s positive experience with private-school financial aid exemplifies why undocumented Succeeders look to private universities like Baldwin whose aid process does not always require the FAFSA. These private aid processes and associated documents are blind to immigration status and thus more open to undocumented youth than those of public higher education. In this way, they allow for educational access and the context for civic inclusion it represents. At the same time, these private systems manifest a different set of exclusions based on auditable notions of merit, such as high test scores, that inhibit institutional and civic inclusion.

The use of merit rather than need as a main criterion for aid is symptomatic of the neoliberal turn in higher education—the infiltration of market logic into the university’s practices and purposes. As a result, profitability, corporate interests, and auditable notions of merit determine university governance, education’s relationship to the public good, and metrics for student (and faculty) achievement (Brenneis, Shore, and Wright 2005; Posecznick 2014; Shore and Wright 1999). While Emma’s scores allowed her educational and civic access, her and others’ experiences of merit-based, non-FAFSA aid processes and documents made visible and material the criteria for educational access, demonstrating how restricted the neoliberal criteria are for access, aid, and, ultimately, civic inclusion.

As undocumented youth navigate merit-based aid processes, their private-sector bureaucratic encounters harm their sense of public belonging and membership. Broadly, low achievers fail to meet high-merit standards and are therefore isolated from education and the civic inclusion it could bring. High achievers leverage accomplishments to educational access; however, they experience the educational and civic inclusion that stems from this access as contingent on their continued performance. While high and low achievers fare differently, their experiences illustrate the limitations of nonjuridical civic inclusion and the role played by neoliberal educational institutions in setting its limits. Private, neoliberal bureaucratic inclusion, in which excellence trumps illegality, provides a critical but limited pathway to educational access that has deleterious civic effects on all undocumented youth.

My findings are based on 12 months of fieldwork in 2012–13 with Succeeders youth. My methods were semistructured interviews with 31 students (high, average, and low academic achievers, who were representative of the broader pool of Succeeders participants); participant observation in and out of the Succeeders program; and analysis of its curriculum. I worked as a volunteer at Succeeders, and students saw me as a resource. As our friendships deepened, I became privy to intimate aspects of students’ lives. I analyze students’ aid experiences with private colleges and the non-FAFSA financial planning documents—budgets, tallies, case studies—created and appropriated by Succeeders’ students and staff.

Private-sector bureaucratic documents, processes, and their relationship to civic inclusion for undocumented youth have three implications. First, as public goods become privatized, private institutions become critical social actors that arbitrate public belonging and membership. The inclusion they offer is not an alternative to the state’s but rather evidence of how the processes and locations of national inclusion shift toward the private sector. Thus, the neoliberal turn in these bureaucratic contexts merits attention, because these ideological underpinnings set some of the terms of inclusion. Second, the institutional and civic inclusion experienced in the private sector remains fraught: as private institutions include undocumented populations in one way, they exclude them in others. The civic inclusion produced through private-sector, neoliberal aid is more expansive than juridical inclusion, but also has its own modes of exclusion (here, merit) that may not supersede juridical exclusion. Third, documents and application processes are the materials and circumstances through which youth negotiate their place in the nation. Such planning documents were the material anchor through which youth experienced the aid process and its accounting of their merit as students and citizens. Attending to the material of these private processes demonstrates how everyday exclusions map onto social ones and how fragile bureaucratic and civic inclusion are for undocumented youth.

Latino Succeeders

In the late 1990s, Nashville’s Latino population rapidly rose, reaching 10 percent of the city by 2010 (Odem and Lacy 2009, xviii; Winders 2013, 19). Like other southeastern “new destinations,” Nashville drew newcomers with its availability of work, low cost of living, and seemingly low levels of nativism and crime (Odem and Lacy 2009, xii). As in other southern cities, Nashville’s schools understood ethnoracial difference in terms of an English monolingual, black-white racial binary, paying little attention to non-English-speaking Others and their needs (Winders 2013). Schools in new destinations, including Nashville, had misaligned services that worked according to a deficit construction of Latino learners—positioning them as academically lacking (Wortham et al. 2002). This school setting led to poor results, including a low Latino high school graduation rate (43 percent in 2003).6 In contrast to other cities’ public schools, Nashville’s became more responsive in part because of educational nonprofits like Succeeders (Flores 2015; Winders 2013).

Founded in 2002, Succeeders began as an offshoot of a larger nonprofit that ran occasional programming aimed at increasing the Latino graduation rate. Now mostly funded by corporations, Succeeders serves about 500 youth, who chose to join, in six public high schools. It works through after-school programming focused on college access and leadership, tours of universities and workplaces, enrichment programming, and individual case management. Staffers also participate in personal realms of students’ lives. The students are largely of Mexican and Central American family origin, low-income, and undocumented (60–75 percent), and they have varied abilities and interests.

The program is successful. In 2013, 94 percent of Succeeders graduated high school; the local Latino graduation rate was 72 percent.7 Of graduating Succeeders, 85 percent applied to university. All applicants were accepted to a community college or a selective institution, and 64 percent of accepted students enrolled. In comparison, Nashville’s average college-going rate—the percentage of spring high school graduates enrolled in higher education by the fall—was 55 percent overall and 34 percent for Latinos, according to the most recent data (2012).8

Why do Succeeders who are admitted to higher education not enroll? Money is central. Undocumented Succeeders who enrolled full-time did so in aid-granting private colleges in Tennessee or in a Kentucky public university that provided reduced tuition. Most of them did not attend Tennessee’s public four-year colleges in either of the state’s two public systems: the University of Tennessee or the Board of Regents. The latter does not provide aid or in-state tuition, while the University of Tennessee system maintains an unofficial ban on undocumented students, making these options untenable (Garrison 2014). Youth did enroll in Board of Regents community colleges, mostly part-time, because undocumented students are not granted in-state tuition or aid, and costs are prohibitive.

Documenting membership: Bureaucracies of belonging

Undocumented Succeeders’ attempts to enter the public and private programs described above illustrate how the experiences of the financial-aid process and its documents shape civic and institutional inclusion. Bureaucratic documents, such as aid forms and identity cards, are linked to bureaucratic processes because they form the setting where people exchange, manipulate, and thereby give meaning to such documents.9 Thus, neither documents nor processes can be fully understood without the other, since together they form the material and context through which people experience the parameters of institutional and civic inclusion (cf. Hull 2012).

Most centrally, bureaucratic processes and their documents mediate institutional and national inclusion for undocumented immigrants (e.g., Coutin 2000; Diaz-Strong et al. 2011; Ticktin 2011). This mediation is accomplished through two interlocking, simultaneous mechanisms. The first is technical—how bureaucrats adhere to and uphold certain criteria in the rules and auditing of paperwork to determine if the applicant is “legally” permitted the entitlements that membership affords, such as property, welfare, or financial aid (Hall and Held 1989, 175). Technical, in this way, also refers to the mechanistic technicalities and systems that bureaucrats and others consider as they arbitrate access. For example, undocumented migrants’ claims to state benefits (like financial aid) are contested because they lack the immigration or citizenship documents often presumed as the technical prerequisite to (juridical) membership’s entitlements. This technical exclusion precludes undocumented migrants from entitlements even if they, like Emma, have a sense of national membership through participating in national institutions like schools.

The second mechanism is emotional—how people respond, in mediated ways, to their collective circumstances in the bureaucratic encounter (Ho 2009, 789–92). The intensity of Emma’s tears as she filled out her application reveals that bureaucratic processes have deeply felt consequences that need consideration. As a first principle, bureaucracies are “emotive domains,” wherein documents are “capable of carrying, containing, or inciting affective energies when … put to use in specific webs of social relation” (Navaro-Yashin 2006, 282; 2007, 81; see also Herzfeld 1992). Bureaucratic processes and documents also elicit emotional responses related to civic inclusion because those in power determine rights claims and membership by defining, accounting for, and legitimizing modes of personhood (Coutin 2000; Leshkowich 2014; Reeves 2013). For example, immigration law and the documents its participants produce (applications) and withhold (identification documents) are “implicated in struggles over personhood and legitimacy” and come to represent people and whether they deserve to be civically included (Coutin 2000, 9, 49, 77). The judgments made by deciding individuals through these documents, which function as the supplicants’ avatars, have emotional consequences that add up to a sense of civic inclusion or exclusion even when a document or process is made unavailable—as the FAFSA and public aid were for Emma. Finally, bureaucratic processes and paperwork produce emotions because belonging is emotional (Ho 2009, 789–792). Bureaucratic attempts to circumscribe belonging will therefore be experienced emotionally, as Emma’s tears attest. While emotional attachment to the nation seems like something that could be isolated from bureaucratic exclusion, the Succeeders’ experiences show it cannot.

I primarily focus on the technical mediation of exclusion in Succeeders’ aid experiences. Public aid excludes technically through the criteria of immigration status, whereas private aid excludes by merit; both, however, mark certain undocumented students as outside of the category of citizen-student. I also highlight students’ emotional responses of joy, worry, or fear because these feelings map onto feelings of belonging. For example, without the FAFSA, Emma is fearful and compelled to stall her college application and to feel excluded; in contrast to these states, her scholarship letters incited pride, joy, and the feeling of belonging.

Clearly, public-sector bureaucracies, processes, and documents are central sites where bureaucrats arbitrate civic and institutional inclusion and supplicants feel the effects of this arbitration. For undocumented people, immigration documents and processes are paramount in determining an aspect of their civic inclusion, their juridical membership (Coutin 2000). Undocumented immigrants, however, also gain sociocultural membership and belonging through school, work, and other private institutions (Chauvin and Garcés-Mascareñas 2014; Coutin 2000; Gleeson and Gonzales 2012). Thus, public-sector exclusions may not map onto the expansiveness of lived inclusion. Moreover, the arbitration of nonimmigration and nonstate processes and paperwork, like private financial aid, also confronts undocumented youth with exclusion. The private sector has its own exclusionary criteria, illustrating the centrality of private-sector institutional actors in deciding some terms of national and institutional inclusion and exclusion (Abrego 2006; Diaz-Strong et al. 2011; Gonzales 2016; Menjívar 2006). Central to this point is an understanding of educational settings as charged and changing locations for youth’s experiences of belonging and sociocultural membership. The shifting ideological contexts of private educational bureaucracies affect the modes of institutional and civic inclusion available to undocumented youth. Institutional and civic inclusion are practically and ideologically complicated as private educational institutions prove more inclusive, differently exclusive, and central to civic inclusion in neoliberal times. I now turn to these ideological contexts.

Forms of exclusion: Neoliberal universities, financial aid, and undocumented youth

In the past 40 years, neoliberal ideology—a complex of beliefs in the sensibility of applying extreme free-market principles beyond the market—has infiltrated myriad aspects of social life, including public and private higher education (cf. Comaroff and Comaroff 2001). The application of neoliberal ideology—neoliberalization—has shifted universities’ funding, organizational and hiring structures, and role in negotiating civic inclusion as schools worldwide become more profit-driven and focused on slippery, but quantified, measures of merit and excellence to govern the university and those within it (Posecznick 2014; Reading 1996; Saunders 2010; Shore and Wright 1999).

In analyzing education’s neoliberalization, one concern has been how it shifts the university’s purpose away from being a “public right and means to liberate and cultivate citizens” (Wright and Rabo 2010, 2; see also Fallis 2007; Readings 1996). In a neoliberal university, “financial returns are now increasingly cast as the public good,” potentially narrowing the university’s mission to education’s economic, not civic, ends (Shore and McLauchlan 2012, 268, 280–83). A pivotal and related concern is how the auditing of merit harms both faculty members’ (Shore 2008) and students’ (Oxlund 2010) sense of personhood and institutional and civic inclusion (see also Shore and Wright 1999, 559).

Yet higher education’s neoliberalization, even if it seems totalizing, is “partial and incomplete,” with neoliberal logics coexisting with others, including the inclusionary civic logic, “in overlapping and contradictory ways” (Brenneis, Shore, and Wright 2005, 3). This is true for aid. The neoliberal turn in higher education has created an aid system that prioritizes profit and measureable merit, but also a private-sector system that provides a surprising window of access for undocumented students through this very same attention to auditable merit. Thus, Emma’s score of 27 on the entrance exam was judged by admissions gatekeepers as sufficiently meritorious for admission and the civic inclusion she believes it holds. All youth can exploit, or be exploited by, this merit accounting, but because undocumented youth are denied public aid, the window of access through merit is often the only opportunity to gain the civic inclusion that they believe college promises. Yet this is a narrow window that ultimately excludes high and low achievers alike.

Modern US financial aid is an excellent case study of how enacting neoliberalization affects students’ sense of institutional and national inclusion. Briefly, public financial aid dates to the Higher Education Act of 1965 and the programs that followed throughout the 1960s and early 1970s, including Pell Grants (Wilkinson 2005, 61). Prior federal programs existed, such as the GI Bill (Wilkinson 2005, 46–62), but the initial goals of post-1965 federal aid were to ameliorate educational opportunity gaps for low-income and minority students more widely and to promote these students’ civic and educational inclusion by removing fiscal barriers (Wilkinson 2005, 55, 115–21).10 This development of aid bureaucracies following the civil rights movement and the War on Poverty matches the rendering of higher education’s civically inclusive purpose as a “public right” and “means to liberate and cultivate citizens” (Wright and Rabo 2010, 2).

State, federal, and most public and some private aid processes begin when applicants complete and submit the FAFSA (online or by mail) to the Office of Federal Student Aid. The form is so iconic as a paper gatekeeper to the entire aid process that Succeeders, documented or not, referred to the financial aid process as “doing the FAFSA.” When filing the FAFSA, students list up to 10 schools that will receive the information from the document to use in determining their institutional aid. State higher-education agencies will also receive FAFSA data, though students may have to file additional paperwork for state aid.

Only citizens, permanent residents, and the holders of particular immigration statuses—detailed below—can file the FAFSA and thereby receive federal and most state aid. This provision technically excludes certain migrants because a Social Security number is not required for filing; rather, all that is required is a tax return from the student or the student’s parents if they are dependents. Thus, students who are citizens, but whose parents are undocumented, can file a FAFSA as long as the student files taxes under their Social Security number or their parents file taxes using an individual tax identification number (Olivas 2009, 411–12).

FAFSA and public aid’s status limitations draw technical boundaries around just who “the citizens” are to be cultivated in higher education (Wright and Rabo 2010, 2). Moralizing judgments about immigrants’ fitness for membership help determine FAFSA eligibility, since some immigration statuses are deemed worthy and others are not, even though they have similar temporal limitations or frameworks (Ticktin 2011). The following immigrants are eligible to apply for federal and state aid by submitting the FAFSA: I-94 holders, but only those designated Cuban-Haitian Entrant, Refugee, Asylum Granted, Parolee (with restrictions), or Conditional Entrant (with restrictions); T-visa recipients (given to those who have been trafficked); and those who qualify as “battered immigrant” (under the Violence against Women Act).11 In contrast, the following immigrants cannot receive federal and most state aid, though their families may file the requisite federal tax returns: those exempted from deportation under the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) policy, those granted U visas (given to victims of crimes), those granted Temporary Protected Status (TPS), and those who lack any immigration authorization (Olivas 2009). Denying access to higher education has historically been a strategy “to further disenfranchise vulnerable communities” (Diaz-Strong et al. 2011, 108). The denial of public aid to undocumented youth is but the contemporary example. This denial pushes higher education away from its civic purpose and pushes aid away from its idealistic roots as a mechanism for civic inclusion.

The technical limitations on granting financial aid according to immigration status demonstrate the central role that educational institutions play in determining the boundaries of national inclusion (Abu El-Haj 2015, 6). These aid processes gain traction in their exclusions by aligning with other modes of exclusion. For example, the circulation of the “Latino threat narrative” in the media—wherein Latinos not only represent a problematic demographic transition away from whiteness but also fundamentally challenge an imagined core of white, Protestant values (Chavez 2008, 3). Most materially, legislators have kept meaningful aid legislation off the table (Olivas 2012, 64–86).

To return to the aid process, once eligible students file their FAFSAs, the Office of Federal Student Aid processes them to calculate students’ federal aid eligibility. Once the FAFSA is processed, students receive a Student Aid Report from the office listing their eligibility and their estimated family contribution (EFC)—what the office determines the family can pay for the next year of college. Students may also receive information on state aid from state higher-education agencies. Finally, they receive an award letter regarding need-based aid from the individual colleges (public and private) that students shared their FAFSA with when initially submitted. Individual schools’ award packages are calculated by subtracting the EFC from the school’s cost of attendance (Dynarski and Scott-Clayton 2013, 14). Additionally, private schools often have funds for supporting certain kinds of students (e.g., at Christian colleges, the children of ministers) and for awarding aid based on merit. Such scholarships often do not require a FAFSA, freeing private schools to include undocumented students, whereas public schools cannot, because they usually determine all aid through the FAFSA.

As public and private university administrators became more neoliberal in their practice, contemporary aid became ideologically murky, shifting away from its civic ends (Long and Riley 2007; Wilkinson 2005). Profitability has “led institutions to alter admissions policies and priorities by focusing on full-paying and well-qualified students who will cost less to serve” (Saunders 2010, 56). Thus, some university administrations have dropped a commitment to need-blind admissions and the shrinking of opportunity gaps. Additionally, public aid now often focuses on defraying costs for the middle class rather than on opening access to those least served and least able to pay (Dynarski 2000). While admissions and aid have long been audits of students’ excellence, the neoliberal turn has led institutions to jockey for these “high-achieving/performing students who can raise the academic profile (and rank) of the school” and pay for it (Weis, Cipollone, and Jenkins 2014, 12). In these admissions and aid processes, students defined by both merit and ability to pay experience anxiety that can lead to alienation (Demerath 2009). While the shift from need to merit disadvantages all economically and scholastically marginal students, the stakes were higher for undocumented youth, since merit aid is often the only form available to them.

The private universities that Succeeders attend are committed to opening access, because of their administrators’ personal, religious, and political beliefs in promoting undocumented students’ rights. In admitting and aiding undocumented students, these private institutions are uniquely inclusive, given that few private institutions are afforded institutional support and the financial means to enable undocumented youths’ educational access. This is a laudable commitment to access—a commitment that is, however, subject to a merit-and market-based logic in two ways.

First, unlike public community colleges or nonselective public universities, these private schools can and do have rigorous admissions criteria, for example, high minimum scores on standardized tests. The admissions process is already restricted by merit. Selectivity is an important criterion for the neoliberal ranking of universities; thus, private, and some public, schools are incentivized to be selective (Weis, Cipollone, and Jenkins 2014, 12). Indeed, Baldwin’s student center recently featured a banner that highlighted the school’s high position in U.S. News and World Report’s college rankings, which frequently foreground acceptance-rate selectivity.

Second, because merit, not need, determines aid, schools make a calculated decision based on the financial bottom line. While they want to include undocumented youth because of their ideological commitments to them, they would bear a fuller financial commitment if they also granted these students aid based on need. This is not to say that need is not considered at all. Undocumented Succeeders and admissions gatekeepers would go back and forth on what the family could pay. Students who got to this step, however, were those deemed sufficiently meritorious. In private schools, blindness to immigration status makes these universities more open than public ones, yet it establishes a different kind of exclusivity based on merit—a neoliberal sentiment that both includes and excludes, though in a different way. For high achievers like Emma, being excluded from the FAFSA because of migration status is tempered by access in the private sector. Low achievers, whose experiences I track below, are doubly disinherited, first by status and then by merit, and their alternative avenue for educational and civic access is closed.

The shifting ideological ethos of private-school bureaucracies affects aid processes and the inclusion that students feel in and through school. These effects manifest through the aid encounter and the documents students collect and create. I shift to how these financial-planning documents and processes manifest the local educational bureaucracy that students experience.

The Presupuesto: Making bureaucracy and modes of inclusion visible

The local educational complex that will mediate students’ institutional and civic inclusion begins at Succeeders. Liz, Succeeders’ coordinator, and colleagues designed the Presupuesto (Budget) for a joint workshop with undocumented families convened by Succeeders and other local educational-access organizations (see Figure 1). The goal of the document was to provide undocumented youth with a FAFSA-like form to calculate school costs. Since the Presupuesto does not require students to be citizens or documented to use it, it conceptually includes undocumented youth as part of the population bound for higher education, just as the Succeeders program does. When one is barred from using the most basic form of financial aid, such a document is not a trivial one for families, who often brought the form or homemade variations on it to meetings with admissions gatekeepers.

Figure 1.

The Presupuesto (Budget) works to calculate monthly contributions to college costs for undocumented students, who are barred from applying for federal financial aid. (Courtesy of Succeeders)

The Presupuesto also demonstrates the private, neoliberal bureaucratic arrangements that technically make possible educational access and the potential civic inclusion it is imagined to bring. After the successful joint workshop, Liz and Succeeders’ director, Sofía, adapted the form for evening aid meetings with parents and student activities, where I first observed the form’s use as part of the curriculum. Like Emma, students then used the form as they made their budgets. As students or parents calculated what they had to pay in Succeeders meetings, they asked about Baldwin and other private schools, checking on information from family and former Succeeders who had successfully navigated the private system. Obliquely highlighted in these questions was the organization’s role in this aid system and Liz and Sofía’s excellent relationships with private schools’ admissions gatekeepers. The women were careful to say that they had good relations across many schools.12 Only their relationships with private-school gatekeepers, however, could be leveraged for aid for high achievers. For example, an admissions gatekeeper told me she relied on Liz and Sofía to tell her “who I should fight for” as aid packages were hashed out. Together, the nonprofit and private schools formed a privatized higher-educational bureaucracy that was more technically inclusive. This bureaucratic formation was in accord with higher education’s civic mission and could offer institutional and potentially civic inclusion.

Another aspect of the private educational bureaucracy was reflected in the Presupuesto: the corporation. These financial-aid meetings, additional handouts, and PowerPoint presentations were cosponsored by and cobranded with a Succeeders corporate funder, Friendly Insurance. While corporate interests and funding have been problematically integrated in higher education (Giroux 2002), for the Presupuesto and the Succeeders program in general, corporate sponsorship played a positive role, allowing undocumented youth to participate in the program and in the aid process.

Furthermore, while the Tennessee and federal aid systems do not fund undocumented youth, Friendly Insurance does. It and other Succeeders sponsors funded the program’s status-blind scholarships. Each year the program awards $40,000 to $60,000 to about 40 students in varied amounts. Most scholarships are branded with a corporate sponsor, such as the Friendly Insurance Scholarship. Additionally, staff match students’ academic interests to that of the sponsor. For example, Eddy, who studies hospital administration, received his 2013 scholarship from Mockingbird Managed Care, a health-care corporation. Succeeders receive a corporate scholarship that fills in the aid that the state does not give, and in doing so they are marked as aligned with the corporation’s interests. Students’ financial dependence makes them beneficiaries, and perhaps members, of the corporation. Educational and civic inclusion comes from the corporation and private educational bureaucracy—in the financial-planning documents, in the aid itself, and in the private schools where students end up.

Students understood this bureaucratic reality. On a tour at Baldwin, I noticed that Javier, a soft-spoken Succeeder, was wearing the college’s sweatshirt. On the bus, I asked him why he wanted to go there. “Because I have to,” he said. “I have to go to a private college, because I’m illegal.” He said “all” he had to do was do well on the university entrance exam, get good grades, and continue with his extracurricular leadership to earn Baldwin’s merit aid and the Succeeders’ scholarship. He was right. With a Succeeders scholarship and Baldwin’s merit aid, Javier matriculated at the college whose sweatshirt he owned. Javier’s path, from Succeeders to Baldwin, shows that students were aware of the practicalities of the neoliberal private system—be excellent to get in, be more excellent to get aid.

The Presupuesto manifests the private educational bureaucracy and how it serves as a bulwark of educational inclusion that could provide a sense of civic inclusion for Javier and others. In this way, private settings set public inclusion. As shown in the following sections, there are cracks in this bulwark that harm youth’s institutional and civic inclusion, especially for low-achieving youth.

Maria and Fernando: The limits of merit for low-achieving youth

The Presupuesto was accompanied by fictional case studies of undocumented students Maria and Fernando (see Figures 2 and 3). These documents were created to show that there were educational options for all undocumented youth—high and low achievers—and that different levels of achievement could affect these options. In the case studies, the conversations around them, and in the aid process, students were introduced to the logic of excellence for access and were forced to measure their chances against the auditable notions of excellence that Maria and Fernando made visible. Being a Maria or a Fernando was about more than the opening and closing of certain educational options; it was about facing how citizenship and then merit could marginalize someone in educational systems and beyond. Here it is possible to see how private systems prove differently exclusive—and in the case of low-achieving students, doubly so—with negative impacts on students’ sense of civic inclusion.

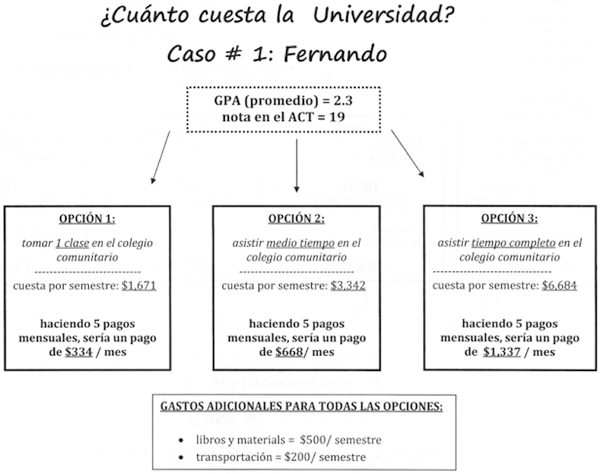

Figure 2.

“Fernando,” a fictional case study created for undocumented students who aspire to attend college, represents a low-achieving student who has limited higher-educational options. (Courtesy of Succeeders)

Figure 3.

“Maria,” a fictional case study created for undocumented students who aspire to attend college, represents a high-achieving student who can leverage her academic success into enrollment at a private, four-year institution. (Courtesy of Succeeders)

While not based on an actual Maria or Fernando, these characters were composites of student trajectories, accurately portraying local understandings of how students would fare in the neoliberal accounting of merit. Fernando is an average student. He has average grades (2.3 out of 4.0) and a 19 (out of 36) on the university entrance exam, three points above the average at Succeeders’ high schools. Fernando has three options: taking a single class or enrolling part-time or full-time in community college. Maria is the high-merit student. She has high grades (3.4) and a score of 24, putting her in the top 25 percent of test takers nationally and six points ahead of Nashville’s average. Thanks to her merit, Maria has one more option, “Opción 4”: enrolling full-time at a private college.

Though Maria and Fernando were created to emphasize the availability of higher education to students across achievement levels, it was difficult for students to accept the community-college options. This difficulty was tied explicitly to the valorization of merit by the neoliberal educational bureaucracy and implicitly by the Maria case study. Community college is not selective and was a default option that did not confer the same sense of accomplishment. The Fernando example caused a feeling of shame among students who were unable to access selective schools. Ángel, a student who barely passed high school, underscored that he wanted to go to “college college”—a four-year institution. When outlining her plans, Janitza, a once-struggling student, told me she would start at community college, “then transfer to a real college.” Janitza, Ángel, and others saw private college as a better way to demonstrate that they were worthy of national inclusion because these schools were exclusive. Auditing affects how people see themselves and their worth—not meeting merit criteria can lead to crestfallen learners, as it did for Ángel when he recognized that he would not get into Baldwin and would face remedial courses in community college (cf. Shore and Wright 1999). Succeeders’ students understood the logic of neoliberal higher education and neoliberal inclusion—only Marias, only the meritocratic, can be members of the institution and nation.13

While engaging with these case studies and related documents, students began to see themselves, and their chances for institutional and civic inclusion, in stark terms. Students parroted back the importance of auditable achievement to staff, each other, and me. Being a member of Succeeders was already a way that students marked themselves as Marias committed to success, partially understood as having high test scores and grades and being involved in extracurricular activities. For students who were more Fernando than Maria, the failure to obtain merit aid often harmed their sense of self, membership, and belonging.

Consider Natalia’s experience. When I first met Natalia, she giddily told me of her love for Boston (my hometown) and her desire to enroll in medical school there. As I got to know her, it became clear to me that she was impressive: an intensely curious student, star of her high school stage, the president of her school’s Succeeders chapter. Natalia was also an adept advocate for achievement, pointing out to her classmates the increased options highlighted by the Maria document and having conversations around it. She implored them to attend tutoring, get involved in clubs, and study—sometimes to conspicuous eye-rolls. She understood the value of being a Maria. Yet her many involvements and family commitments left her scrambling to study. As a result, her low grades and scores did not reflect the passionate learner I knew.

When I asked Natalia why college and academic achievement were important to her, she said, “That piece of paper [college diploma] defines you. […] I want to be defined as somebody good, not a bum. […] I want people to look at me as ‘Wow, she did it, and she’s Hispanic.’ […] I want people to say, ‘Oh, she’s good.’” Natalia saw higher education reflecting well on her as a person and in particular as a Latina.14 School was a way to prove she belonged as a valuable member of the nation.

Natalia aspired to attend Baldwin; she did not want to go to community college but rather to “someplace big.” As she applied to four-year schools, Natalia’s status—in terms of immigration and achievement—became clearer, complicating her sense of civic belonging and membership. Natalia had TPS and was therefore ineligible for the FAFSA. This contrasted with how she had seen herself as a legal resident with entitlements. As we talked about her plans, Natalia’s mind wandered to the 2012 election:

I’m trying to have somebody that’s going to benefit me and benefit students who came here legal. […] Do we get anything? Because sometimes—I’m so happy that they’re giving illegal people good things—but sometimes I’m just like, “Well, what about people who followed the rules?”

While she told me she did not think she was “better than” undocumented students, she nonetheless felt that she should have entitlements that they should not—she was “legal.” The FAFSA, however, would technically exclude her because TPS holders cannot file it, making her “illegal.” Natalia experienced this exclusion emotionally. As Sofía and Liz spoke with her, Natalia would repeatedly ask if she could file the FAFSA, each time appearing confused, angry, and hurt. She disengaged. She thought she was “legal” and a legitimate American. Financial aid confronted her, technically and emotionally, with the fact that she was not.

Natalia was admitted to Baldwin. She was elated, proudly posting her acceptance letter on a social-networking site and showing signs of her optimism. Yet, Natalia’s low test scores did not qualify her for merit aid and ultimately prevented her from attending Baldwin. She also faced the reality that besides not wanting to attend community college, she could not afford it. If she could not attend Baldwin or any other school, she could not demonstrate to others that she was “somebody good,” worthy of institutional and national inclusion. While Liz and Sofía encouraged her to negotiate her aid or enroll in one class at the community college, Natalia did neither and isolated herself, a common response when students faced newfound commonality with the undocumented population (Gonzales 2016).

Natalia was doubly marginalized—first by status, then by merit. Confronting the limits of her status was destabilizing enough; confronting the limits of her merit in further negotiating aid would be too destabilizing. She may have been a Maria in her enthusiasm for learning, but her academic status, as a Fernando, would keep her from the private sector that could more easily include her institutionally and potentially civically. Natalia weighed online programs and tried to regain her characteristic optimism and sense of herself as “somebody good.” Private aid, while a mode of partial civic and educational inclusion, is just that—partial—with negative impacts on low-achieving youth’s educational trajectories and sense of civic inclusion.

Neveah’s aid: The limits of merit for high-achieving youth

High-achieving undocumented students’ enrollment in private colleges should not be seen as an unproblematic mode of accessing education and the civic inclusion it could bring. While Emma was overjoyed to get aid, it was a process that unfolded painfully and fitfully though myriad forms, bills, and letters. At one point, Emma considered community college or just not going because her unsure financing was causing her great stress. Emma felt isolated from her classmates and keenly aware of the limits of her membership, money, and merit. Emma’s sharply funny fellow Succeeder, Neveah, could also successfully leverage her excellence to admissions, but she found this educational inclusion, and the civic inclusion it maps onto, permanently conditioned on her continued excellence. This facet of Neveah’s experience illustrates how private, neoliberal, merit-based aid harms youth civically; to see this, it is necessary to trace Neveah’s path from admission to conditional inclusion. This path is made clearest by her budget.

Neveah applied and was accepted to three private, Christian schools, including Baldwin. She was not sure she could attend because of money. During a meeting in which students were to work on scholarship applications, Neveah created and filled out her own budget, like Emma and other Succeeders I knew had. Students’ complex, homemade forms suggested their worries over costs, their understanding of the precarious position of undocumented students, and their belief that through merit they could achieve institutional and potentially civic inclusion in the private sector. These documents rendered bureaucratic realities and instantiated what these realities held for their futures.

Neveah’s budget and her aid trajectory illustrate the impact of aid documents and processes on students’ civic belonging and sociocultural membership. In her budget, Neveah listed the cost of three private schools she had been admitted to, her scholarships, her family’s contribution (a high estimate), and what would be left to pay.

“Man, this would be a lot easier if we were legal!” she joked to her sister.

Javier, the student with the Baldwin sweatshirt, warned Neveah about the risks of working—the outcome she saw as inevitable based on the “left to pay” row on her budget. Javier explained that if she took on a job, she might fall behind in her preparation for the university entrance exam, as he had done now that he was working. Neveah included another table, tellingly titled “Potential” that showed how her academic scholarships increased if she brought up her standardized-test score a few points. Herein lies Neveah’s, and all high achievers’, dilemma: she can, through work, earn the money for school, which will likely result in sacrificing her studies. Alternatively, she can “intellectually earn” the money by focusing on test prep to increase her scores and gain scholarships. Those points are potential, not guaranteed, earnings. Even though she gained educational access through the private sector, this access was tempered by merit. She can be included institutionally and potentially civically only if she meets the merit standards for aid. By the end of the meeting, Neveah decided to take on a few hours at McDonald’s once her work permit came in, increasing her hours to full-time over the summer to make the $10,000–$13,000 she needed to attend school—for that year. She would also retake the standardized test, hoping for just one more point.

Neveah enrolled in Baldwin, with the help of her job, her Succeeders scholarship, and her high test score. Her wages and scholarships, however, did not solve her aid issues. Over fries, we talked through the pressures of her merit aid and its demand that she continue to discipline herself to achieve excellence:

I’m just, like, freaking out to keep up my GPA. Like, if I get up to 3.5 and I get scholarships for 3.5, I’m going to have to keep it up at college when I could barely keep it up at high school. […] I’m just like, “Oh my God, if I go to college, I’m going to have to have a job, but then I’m going to have to learn how to balance all this other stuff. I’m going to have to do extracurricular activities so I can keep scholarships and stuff like that.” I don’t know what I’m going to do.

Neveah worried about meeting quantifiable scholarship criteria. Admission and institutional inclusion in the private sector were never guaranteed—they would be possible only if she could keep up her merit and continue to “be” a 3.5 (cf. Shore 2008 for a similar case facing faculty). Unlike her documented and citizen peers, she has neither an alternative mode of financing (like bank loans) nor a readily available, or equally powerful, alternative mode of institutional and civic inclusion beside school. While her merit aid and the private college system enabled her educational inclusion, her emotional state of “freaking out” about maintaining her grades points to the conditionality of this educational inclusion and the emotional distress it causes (Shore 2008, 282).

If this private educational inclusion was conditional on merit, so was the civic inclusion that it portended. Neveah and I had breakfast at Waffle House and discussed this article, her budgets, and her struggles to maintain her grades and job. She took pride in being what she called “that kind of person” who could earn aid through achievement. While the neoliberalization of higher education has negative consequences for many (Shore and Wright 1999), for Neveah, her success in neoliberal auditing—while nerve-racking and continual—was also positive. This achievement, however, didn’t automatically translate to a firm sense of sociocultural membership and belonging, as she hoped. Although she could get merit aid, Nevaeh still felt “mad” that she couldn’t get public-sector merit scholarships—even though, were she documented, she could qualify. I asked Neveah to expand on her anger at being unable to access state scholarships and whether that mattered to her sense of herself. Her response revealed how merit-based and state financial aid were important to her:

I see all these people around me getting these benefits—scholarships, HOPE [a public merit scholarship]—where I can qualify for them just like anyone else here. Yet I can’t receive it. It used to be the same way with a job, insurance, and a [driver’s] license. I couldn’t get any of it, and it honestly felt it was because I didn’t deserve it. It’s because I am not entitled to something that makes me feel like I don’t deserve it. And even now that I was finally given these things [work permit, license, scholarships], it’s still the same feeling—like I’m less and these things should not be given to me but I took them anyways, without deserving it. […] I was raised here and this is my home, yet I still feel like I don’t belong.

Even though Neveah has lived in the United States since she was a toddler, has institutional belonging through admission at Baldwin, and has received private-sector merit aid, she feels she is “less” and still “doesn’t belong.” Merit-based, private-sector inclusion does not erase the emotional and civic consequences of public-sector exclusion. Part of this feeling of not belonging is based on conditional belonging at Baldwin—her inclusion is not because she is accepted as a member, but rather is contingent on her continually proving her merit, her deservingness to belong. Neveah must “deserve” both admissions and the civic inclusion it represents based on her merit: she cannot “deserve” a priori. She feels the incompleteness of this institutional inclusivity, and the civic inclusion it maps onto, because both are predicated on continued excellence. Thus, this mode of inclusion through institutions has limits: limits on its ability to engender the feelings and benefits of civic inclusion and limits determined by neoliberal institutional norms.

There is another limit of private aid located in Neveah’s reasoning and experience: it can never make up for the exclusion from the public sector that categorically determines one’s civic inclusion and entitlements. While Neveah may be a sociocultural member of the private educational sector and feel conditional belonging there, her exclusion from the public sector as a noncitizen still affects her sense of national inclusion. Despite her private conditional belonging, she still feels like “I don’t belong.” The public and private sectors’ ethics of aid fail to recognize that membership is a social, lived reality that is sufficient grounds, without conditions, for the material rights, responsibilities, and benefits of national membership.

Conclusion: Aiding inclusion?

Historically, “equal access to postsecondary education in the United States has always been contested because higher education represents a potential relationship to political, social, and economic capital” (Diaz-Strong et al. 2011, 109). For the Succeeders and others like them, it also represents a relationship to civic inclusion. This linkage between education and civic inclusion has been apparent in undocumented youth activists’ representational strategies as they leverage their identities as students—in the use of graduation caps and gowns in protests—as evidence that they deserve juridical inclusion, marginalizing the experiences of low-achieving undocumented youth (Nicholls 2013).

Undocumented Succeeders’ struggles for educational access are part of this national movement while also part of their local understanding of school as the means to be recognized as members of US society. As Cristián, a Succeeder, said, “I think of myself as American because I grew up here. I learned things from here.” Aid processes mediate educational access and its link to civic inclusion. Counting undocumented youth like Cristián as citizen-students entitled to public and need-based private aid recognizes their lived status as sociocultural members, even if they lack juridical membership. This inclusionary view runs contrary to pervasive sentiments governing contemporary membership’s entitlements, but is aligned with how membership is lived. Even if aid were granted, students like Ángel would still face poverty, racism, and poor academic preparation for college. Allowing aid would be one fewer hurdle to college access and the civic inclusion they imagine it will bring.

Until aid is extended to all, its documents and processes will be mechanisms of educational and civic exclusion. Examining the material objects and bureaucratic processes of these everyday instances of educational exclusion illustrates how processes of national exclusion operate locally and institutionally. Educational access is a context in which educational gatekeepers decide who belongs to the nation and its institutions. These instances of inclusion and exclusion can be understood through not only the experiences of Succeeders youth but also the bureaucratic paperwork they use to navigate the aid process. The FAFSA, the Presupuesto, Maria and Fernando, and Emma and Neveah’s budgets are not ephemera but the material, technical, and emotional basis for youths’ educational and civic inclusion or exclusion.

Except for the FAFSA, these documents and processes are part of the private sector. By focusing on the use of these private-sector documents and their shifting ideological context in the private educational sector, I demonstrate how critical the private sector is for undocumented populations’ institutional and civic inclusion. These lived modes of inclusion—in churches, schools, and nonprofits—are central in undocumented persons’ lives for both national attachments and material benefit (Coutin 2000; Gálvez 2010). As this case shows, inclusion, as membership and belonging, is not just mediated by the state and law; rather, it is produced in daily life and, increasingly, in the bureaucratic workings of the private sector. Indeed, undocumented immigrants’ rights to membership are often weighed according to “institutional third parties that may act as grantors and guarantors of deservingness” (Chauvin and Garcés-Mascareñas 2014, 426). Additionally, private institutions are central to delivering public goods, like education, in neoliberal times. The inclusivity extended in the private sector is therefore no longer just informal but one of great importance as these institutions become arbiters of belonging and membership.

Undocumented youth’s national and institutional inclusion is made both possible by the private sector and made fraught as private processes and paperwork prove more inclusive, differently exclusive, and of central importance. For the high-achieving Succeeders, their institutional inclusion in private colleges and by corporate sponsors portends an important mode of educational and social inclusion that could perhaps supersede their public-sector exclusion. Yet, in Neveah’s case, it does not, illustrating the limits of institutional inclusion in leading to national inclusion and the enduring power of public-sector exclusion on civic life.

Deservingness, for aid, admissions, and ultimately, civic inclusion, is weighed through neoliberal logics that prioritize excellence. Higher education’s neoliberalization can alienate those within the system, harming their sense of institutional and civic inclusion as they fail to meet the standards necessary for these modes of inclusion or they experience the inclusion offered as contingent (Shore and Wright 1999). Despite being more expansive because it is nonjuridical, lived sociocultural membership in the nation through institutions can also be exclusionary according to the institutions’ ideological principles. Notions of productivity—be they expressed in grades, test scores, or volunteering in the private sector for the public good—pervade constructions of the good institutional citizen, and potential national citizen, in a neoliberal era (cf. Muehlebach 2012).

When merit-based conditions are imposed on civic inclusion, its very meaning is destabilized and its lived dimensions ignored. Using merit or slippery notions of excellence to mediate civic inclusion means that the standards can become narrower, more exclusive, more ideologically driven by neoliberalism and ideologies that come in its wake. Those who fail to earn enough, study enough, or do what is considered meritorious enough in such a system are excluded from the benefits of substantive and imagined inclusion that they attempt to access in their earning, studying, or doing. Inequalities are entrenched, as opportunity gaps between rich and poor, documented and undocumented increase. Merit becomes shorthand for civic inclusion, just as a 3.5 or 27 becomes shorthand for the included undocumented learner-citizen. Demonstrating how youth leverage or fail to leverage excellence toward civic inclusion in private educational systems points to how limited and fraught these educational pathways to civic inclusion are for undocumented youth.

Acknowledgments.

I am deeply grateful to the Succeeders who shared their lives and dreams with me. Liz and Sofía at Succeeders deserve thanks for their support. I also thank the following for their gracious feedback: Chelsea Cormier-McSwiggin, Susan Ellison, Kevin Escudero, Sohini Kar, Jessaca Leinaweaver, Sarah Newman, and Stacey Vanderhurst. Finally, I am grateful to the anonymous reviewers, Niko Besnier, and Angelique Haugerud for their constructive and thorough comments. This research was funded by the Ruth Landes Memorial Research Fund.

Footnotes

All individual and organizational names in this article are pseudonyms.

In the United States, college refers to higher education generally, institutions that grant only undergraduate degrees, and the university’s unit that grants undergraduate degrees. I use college in the sense of higher education generally, according to my interlocutors’ convention.

Following others (Abrego 2006, 216; Menjívar 2006), I designate as “undocumented” both youth without documented immigration statuses and those youth with “quasi-legal” statuses—for example, those granted Temporary Protected Status (TPS) or barred from deportation under Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA)—since these statuses also render students ineligible for aid and thus structurally include them in the undocumented population. Besides being barred from receiving public financial aid, undocumented people are ineligible for bank loans unless they have a citizen guarantor. Texas, California, New Mexico, Minnesota, Oregon, and Washington offer undocumented youth state aid, according to the National Conference of State Legislatures, “Undocumented Student Tuition,” accessed March 23, 2016, http://www.ncsl.org/research/education/undocumented-student-tuition-overview.aspx.

The 1982 Supreme Court case Plyler vs. Doe guarantees undocumented youth the right to public K–12 schooling. There is no entitlement for higher education.

This is not to say that success in K–12 or tertiary education remediates all marginalization. Even with educational success, people continue to be marginalized by race, class, gender, nationality, and other axes of difference.

Metropolitan Nashville Public Schools, “MNPS Way ahead of the Curve for Graduation Rates,” accessed March 10, 2013, https://web.archive.org/web/20100619104613/http://mnps.org/Page58227.aspx.

Tennessee Department of Education, “2012–2013 Report Card,” accessed March 23, 2016, https://www.tn.gov/education/topic/report-card.

Tennessee Higher Education Commission, “College Participation of High School Graduates,” accessed March 23, 2016, http://tnmap.tn.gov/thec/.

It is important to distinguish between documents as a category (forms, visa applications, and budgets) and documents as colloquially meaning immigration authorizations. I identify the latter as “immigration authorization documents.” Otherwise, I mean the former—a category of bureaucratic forms, worksheets, and budgets, including those implicated in immigration.

Increasing access to minorities was not a universal goal (Wilkinson 2005, 123).

Office of Federal Student Aid, “Who Gets Aid: Non-U.S. Citizens,” accessed March 10, 2014, http://studentaid.ed.gov/sa/eligibility/non-us-citizens.

Succeeders had advocates at public colleges, but because of public schools’ policies, these advocates were unable to grant financial aid.

Community college offered chances to salvage institutional and social belonging. Community college pathways present challenges, including low transfer rates to four-year institutions.

There are politics of naming in the use of Latino/a or Hispanic. While I use Latino/a most commonly in my work, Succeeders—including Natalia—used both terms interchangeably.

References

- Abrego Leisy Janet. 2006. “‘I Can’t Go to College Because I Don’t Have Papers’: Incorporation Patterns of Latino Undocumented Youth.” Latino Studies 4 (3): 212–31. [Google Scholar]

- Abu El-Haj, Thea Renda. 2015. Unsettled Belonging: Educating Palestinian American Youth after 9/11. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bosniak Linda. 2006. The Citizen and the Alien: Dilemmas of Contemporary Membership. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Brenneis Don, Shore Cris, and Wright Susan. 2005. “Getting the Measure of Academia: Universities and the Politics of Accountability.” Anthropology in Action 12 (1): 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Chauvin Sébastien, and Blanca Garcés-Mascareñas. 2014. “Becoming Less Illegal: Deservingness Frames and Undocumented Migrant Incorporation.” Sociology Compass 8 (4): 422–32. [Google Scholar]

- Chavez Leo R. 2008. The Latino Threat: Constructing Immigrants, Citizens, and the Nation. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Comaroff Jean, and Comaroff John L.. 2001. Millennial Capitalism and the Culture of Neoliberalism. Durham, NC: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Coutin Susan Bibler. 2000. Legalizing Moves: Salvadoran Immigrants’ Struggle for U.S. Residency. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. [Google Scholar]

- Demerath Peter. 2009. Producing Success: The Culture of Personal Advancement in an American High School. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Diaz-Strong Daysi, Christina Gómez, Luna-Duarte Marie E., and Meiners Erica R.. 2011. “Purged: Undocumented Students, Financial Aid Policies, and Access to Higher Education.” Journal of Hispanic Higher Education 10 (2): 107–19. [Google Scholar]

- Dynarski Susan. 2000. “Hope for Whom? Financial Aid for the Middle Class and Its Impact on College Attendance” NBER Working Paper 7756. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research. [Google Scholar]

- Dynarski Susan and Judith Scott-Clayton. 2013. “Financial Aid Policy: Lessons from Research” NBER Working paper 18710. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fallis George. 2007. Multiversities, Ideas, and Democracy. Toronto: University of Toronto. [Google Scholar]

- Flores Andrea. 2015. “Empowerment and Civic Surrogacy: Community Workers’ Perceptions of Their Own and Their Latino/a Students’ Civic Potential.” Anthropology and Education Quarterly 46 (4): 397–413. [Google Scholar]

- Gálvez Alyshia. 2010. Guadalupe in New York: Devotion and the Struggle for Citizenship Rights among Mexican Immigrants. New York: New York University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Garrison Joey. 2014. “Tennessee Universities Differ on Accepting Undocumented Students.” Tennessean, March 10 Accessed March 21, 2014 http://www.tennessean.com/story/news/education/2014/03/10/tennessee-universities-differ-on-accepting-undocumented-students/6272945/. [Google Scholar]

- Giroux Henry A. 2002. “Neoliberalism, Corporate Culture, and the Promise of Higher Education: The University as a Democratic Public Space.” Harvard Educational Review 72 (4): 425–63. [Google Scholar]

- Gleeson Shannon, and Gonzales Roberto G.. 2012. “When Do Papers Matter? An Institutional Analysis of Undocumented Life in the United States.” International Migration 50 (4): 1–19.24899733 [Google Scholar]

- Gonzales Roberto G. 2011. “Learning to Be Illegal: Undocumented Youth and Shifting Legal Contexts in the Transition to Adulthood.” American Sociological Review 76 (4): 602–19. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzales Roberto G. 2016. Lives in Limbo: Undocumented and Coming of Age in America. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzales Roberto G., and Chavez Leo R.. 2012. “Awakening to a Nightmare.” Current Anthropology 53 (3): 255–81. [Google Scholar]

- Hall Stuart, and Held David. 1989. “Citizens and Citizenship” In New Times: The Changing Face of Politics in the 1990s, edited by Hall Stuart and Jacques Martin, 173–88. London: Lawrence and Wishart. [Google Scholar]

- Hertzfeld Michael.1992. The Social Production of Indifference: Exploring the Symbolic Roots of Western Bureaucracy. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ho Elaine Lynn-Ee. 2009. “Constituting Citizenship through the Emotions: Singaporean Transmigrants in London.” Annals of the Association of American Geographers 99 (4): 788–804. [Google Scholar]

- Hull Mathew S. 2012. “Documents and Bureaucracy.” Annual Review of Anthropology 41:251–67. [Google Scholar]

- Leshkowich Ann Marie. 2014. “Standardized Forms of Vietnamese Selfhood: An Ethnographic Genealogy of Documentation.” American Ethnologist 41 (1): 143–62. [Google Scholar]

- Long Bridget Terry, and Riley Erin. 2007. “Financial Aid : A Broken Bridge to College Access?” Harvard Educational Review 77 (1): 39–63. [Google Scholar]

- Menjívar Cecilia. 2006. “Liminal Legality: Salvadoran and Guatemalan Immigrants’ Lives in the United States.” American Journal of Sociology 111 (4): 999–1037. [Google Scholar]

- Muehlebach Andrea. 2012. The Moral Neoliberal: Welfare and Citizenship in Italy. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Navaro-Yashin Yael. 2006. “Affect in the Civil Service: A Study of a Modern State-System.” Postcolonial Studies. 9 (3): 281–94. [Google Scholar]

- Navaro-Yashin Yael. 2007. “Make-Believe Papers, Legal Forms and the Counterfeit: Affective Interactions between Documents and People in Britain and Cyprus.” Anthropological Theory 7 (1): 79–98. [Google Scholar]

- Nicholls Walter J. 2013. The DREAMers: How the Undocumented Youth Movement Transformed the Immigrant Rights Debate. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Odem Mary E., and Lacy Elaine. 2009. Introduction to Latino Immigrants and the Transformation of the U.S. South, edited by Odem Mary E. and Lacy Elaine, ix–xxvii. Athens: University of Georgia Press. [Google Scholar]

- Olivas Michael A. 2009. “Undocumented College Students, Taxation, and Financial Aid: A Technical Note.” Review of Higher Education 32 (3): 407–16. [Google Scholar]

- Olivas Michael A. 2012. No Undocumented Child Left Behind: Plyler v Doe and the Education of Undocumented Schoolchildren. New York: New York University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ong Aihwa. 1996. “Cultural Citizenship as Subject-Making: Immigrants Negotiate Racial and Cultural Boundaries in the United States.” Current Anthropology 37 (5): 737–62. [Google Scholar]

- Oxlund Bjarke. 2010. “Responding to University Reform in South Africa: Student Activism at the University of Limpopo.” Social Anthropology 18 (1): 30–42. [Google Scholar]

- Posecznick Alex. 2014. “On Theorising and Humanizing Academic Complicity in the Neoliberal University.” Learning and Teaching 7 (1): 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Readings Bill. 1996. The University in Ruins. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Reeves Madeline. 2013. “Clean Fake: Authenticating Documents and Persons in Migrant Moscow.” American Ethnologist 40 (3): 508–24. [Google Scholar]

- Saunders Daniel B. 2010. “Neoliberal Ideology and Public Higher Education in the United States.” Journal for Critical Education Policy Studies 8 (1): 41–77. [Google Scholar]

- Shore Cris. 2008. “Audit Culture and Illiberal Governance: Universities and the Politics of Accountability.” Anthropological Theory 8 (3): 278–98. [Google Scholar]

- Shore Cris, and Laura McLauchlan. 2012. “‘Third Mission’ Activities, Commercialisation, and Academic Entrepreneurs.” Social Anthropology 20 (3): 267–86. [Google Scholar]

- Shore Cris, and Wright Susan. 1999. “Audit Culture and Anthropology: Neo-liberalism in British Higher Education.” Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute. 5 (4): 557–75. [Google Scholar]

- Soysal Yasemin. 1994. Limits of Citizenship: Migrants and Postnational Membership in Europe. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ticktin Miriam. 2011. Casualties of Care: Immigration and the Politics of Humanitarianism in France. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Weis Lois, Cipollone Kristin, and Jenkins Heather. 2014. Class Warfare: Class, Race, and College Admissions in Top-Tier Secondary Schools. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson Rupert. 2005. Aiding Students, Buying Students: Financial Aid in America. Nashville, TN: Vanderbilt University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Winders Jamie. 2013. Nashville in the New Millennium: Immigrant Settlement, Urban Transformations, and Social Belonging. New York: Russell Sage Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Wortham Stanton, Murillo Enrique G. Jr., and Hamann Edmund T., eds. 2002. Education in the New Latino Diaspora: Policy and the Politics of Identity. Westport, CT: Ablex. [Google Scholar]

- Wright Susan, and Rabo Annika. 2010. “Introduction: Anthropologies of University Reform.” Social Anthropology 18 (1): 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Yuval-Davis Nira. 2006. “Belonging and the Politics of Belonging.” Patterns of Prejudice 40 (3): 197–214. [Google Scholar]