Abstract

Objective

While excessive daytime sleepiness (EDS) can predate the clinical diagnosis of Parkinson disease (PD), associations with underlying PD pathogenesis are unknown. Our objective is to determine if EDS is related to brain Lewy pathology (LP), a marker of PD pathogenesis, using clinical assessments of EDS with postmortem follow-up.

Methods

Identification of LP was based on staining for α-synuclein in multiple brain regions in a sample of 211 men. Data on EDS were collected at clinical examinations from 1991 to 1999 when participants were aged 72–97 years.

Results

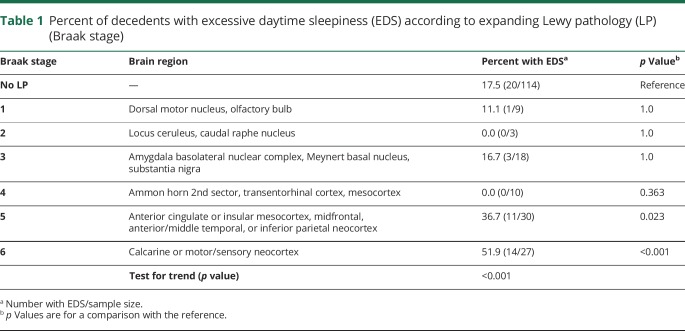

Although EDS was more common in the presence vs absence of LP (p = 0.034), the association became stronger in neocortical regions. When LP was limited to the olfactory bulb, brainstem, and basal forebrain (Braak stages 1–4), frequency of EDS was 10% (4/40) vs 17.5% (20/114) in decedents without LP (p = 0.258). In contrast, compared to the absence of LP, EDS frequency doubled (36.7% [11/30], p = 0.023) when LP reached the anterior cingulate gyrus, insula mesocortex, and midfrontal, midtemporal, and inferior parietal neocortex (Braak stage 5). With further infiltration into the primary motor and sensory neocortices (Braak stage 6), EDS frequency increased threefold (51.9% [14/27], p < 0.001). Findings were similar across sleep-related features and persisted after adjustment for age and other covariates, including the removal of PD and dementia with Lewy bodies.

Conclusions

The association between EDS and PD includes relationships with extensive topographic LP expansion. The neocortex could be especially vulnerable to adverse relationships between sleep disorders and aggregation of misfolded α-synuclein and LP formation.

Excessive daytime sleepiness (EDS) is known to predate the clinical diagnosis of Parkinson disease (PD).1 Whether EDS is causally related to PD or is a consequence of an underlying neuropathologic process that appears before the classic motor symptoms of PD is unknown. As part of this process, aggregation of misfolded α-synuclein in the form of Lewy pathology (LP) is a noteworthy benchmark of PD pathogenesis and progression that can develop decades before the clinical diagnosis of PD.2 Evidence further suggests that LP proliferation follows a sequence of stages with origins in the myenteric plexus of the gut and dorsal motor nucleus of the vagal nerve (Braak stage 1).3–5 Infiltration continues to progress into the locus ceruleus (Braak stage 2), the substantia nigra (Braak stage 3), and finally the cerebral cortex (Braak stages 4–6). When Braak stage 3 is reached, the classic motor symptoms of PD begin to appear.5 With continued expansion into Braak stages 5–6, clinical features become fully expressed. Whether EDS is part of this process or has any relationship with LP is unknown. The purpose of this report is to determine if EDS is related to LP and its distribution based on assessments of EDS during clinical examinations of men in the Honolulu–Asia Aging Study (HAAS) with later postmortem surveys of LP and their expansion into multiple brain regions.

Methods

Background and study sample

From 1991 to 1993, the HAAS was launched as a continuation of the ongoing Honolulu Heart Program (HHP) with a dedicated focus on neurodegeneration, cognition, and healthy brain aging.6 As a forerunner to the HAAS, the HHP began as a broadly focused study of cardiovascular disease in a community-based sample of 8,006 men of Japanese ancestry. Participants were aged 45–68 years and longitudinally followed since receipt of inaugural examinations from 1965 to 1968.7 Following a rigid study protocol, all cohort members were given physical examinations with careful documentation of cardiovascular risk factors and related outcomes. During the course of follow-up, participants received repeat examinations with ongoing review of medical records, hospitalizations, and autopsy reports.

Among the original HHP sample, 3,734 men aged 71–93 years were later enrolled in the HAAS (approximately 80% of surviving HHP members). Coinciding with the beginning of the HAAS, an autopsy study was launched following a rigorous protocol of brain dissection. For this report, microscopic surveys of LP from multiple brain regions followed a modified Braak staging protocol in a selected sample of 250 decedents among 491 autopsies that were performed from 1992 to 2003.8 Those selected included all participants with known LP as determined by standardized microscopic evaluation of the substantia nigra and locus ceruleus (24 decedents had PD, 8 had dementia with Lewy bodies, and 85 had incidental Lewy bodies). The remaining participants were without LP. After excluding 39 cases with missing data on the clinical assessment of EDS, a sample of 211 remained (84.4%). Of the 241 decedents who were not selected for Braak staging, assessments of EDS were available in 177 (73.4%). Prevalence of EDS in those selected was 23.2% (49/211). In those not selected, prevalence was 26.6% (47/177). The difference in EDS prevalence between the groups was not significant (p = 0.449).

Standard protocol approvals, registrations, and participant consents

Study methods adhered to institutional guidelines and received approval from an institutional review board. Study participants provided written informed consent.

Assessment of EDS and sleep-related features

Assessment of daily sleep patterns was based on questionnaires that were given at 3 repeat examinations from 1991 to 1999. Questionnaires were administered by trained research technicians following a standardized protocol.9 Similar questionnaires have been used elsewhere.10–13 Assessment of EDS and sleep-related features was based on the most recently available questionnaire prior to death. Here, EDS was defined as present when a participant reported being sleepy most of the day. Data on the duration of EDS and when it began are not available. Other sleep-related features included the average hours of nighttime sleeping, minutes of napping, difficulty falling asleep, loud snoring, and pauses in breathing. Loud snoring and pauses in breathing were considered present when participants responded “often” or “always” to the question “When you are sleeping, how often do you do the following, or has someone told you do the following:” with separate replies for loud snoring and pauses in breathing. Loud snoring was also defined as present when a participant gave a positive response to the question “Has your spouse or other housemate(s) complained about your loud snoring?” Dream enactment behavior was not assessed.

Determination of LP

Standardized gross and microscopic assessment and procedures for identifying LP from hematoxylin & eosin–stained sections of the substantia nigra and locus ceruleus have been described previously.8,14,15 Immunohistochemical staining for α-synuclein was completed in the 211 brains available for this report in sections from the olfactory bulb, medulla, pons, midbrain, hippocampus, amygdala, striatum at the level of the nucleus accumbens, basal forebrain, and 9 cortical regions (anterior cingulate, anterior temporal mesocortex, entorhinal cortex, insular cortex, midfrontal, anterior superior and midtemporal, inferior parietal, calcarine, and superior precentral and postcentral gyri).8 Across the regions, modified Braak staging was undertaken using a semiquantitative pathology density analysis.5 LP was defined as positive by the presence of Lewy bodies or Lewy neurites. Diagnoses of PD and dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) were based on clinical criteria as described elsewhere and pathologically confirmed by the presence of LP.16,17

Other characteristics measured during life

Other characteristics measured during life included age at EDS assessment, age at death, time from EDS assessment to death, midlife cigarette smoking and daily coffee intake, constipation, cognitive function, depressive symptoms, and the use of antidepressants, antipsychotics, and sedatives. Prevalence of cardiovascular disease was also recorded. Midlife smoking (pack-years) and coffee intake (mL/d) at initiation of the HHP (1965–1968) were used as measures of an overall lifetime of exposure to these factors. Data on the intake of coffee at the time of EDS assessment were not collected, and cigarette smoking in late life was too uncommon to be a useful marker of typical smoking behavior. Coffee intake was recorded by a dietician using 24-hour recall methods with validation in a subset of cohort members based on 7-day food frequency records.18–20 The most recently available performance score from the Cognitive Abilities Screening Instrument (CASI) prior to death was used as a measure of cognitive function.21 CASI scores range from 0 to 100 with higher performance scores reflecting better cognition. Constipation was measured at initiation of the HAAS (1991–1993) and defined as <1 bowel movement/d. Data on depressive symptoms and the use of antidepressants, antipsychotics, and sedatives were collected at initiation of the HAAS (1991–1993) and at examinations received from 1999 to 2000. Treatment with antidepressants, antipsychotics, or sedatives at either examination was defined as the use of such medications. A definition of depressive symptoms was based on an 11-item modification of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale.22 Participants with scores >8 at the most recent assessment were defined as having depressive symptoms. Participants with a history of coronary heart disease or stroke at any time up until EDS assessment were defined as having prevalent cardiovascular disease.23,24

Statistical methods

The percent of decedents with EDS are reported for those without LP and according to its increasing topographic expansion (Braak stages 1–6). Frequency of EDS is compared between each Braak stage vs the absence of LP using standard χ2 tests of association. In cases where sample sizes are small, tests of significance rely on Fisher exact test. To help describe the association that EDS has with the other characteristics measured during life, comparisons are made between those with and without EDS based on standard t tests for continuous variables and χ2 or Fisher exact test for features that are dichotomous.

As a follow-up, the relative odds of EDS (and 95% confidence interval [CI]) comparing decedents with LP falling within a range of Braak stage vs decedents without LP are adjusted for age at the time of EDS assessment using logistic regression models. While EDS was assessed before autopsy, its proximity to LP development (before or after) is unknown. As the direction of association is not clear, we chose to model EDS as a simple binary dependent variable with age and LP as independent variables. Modeling Braak stage as an ordinal dependent variable produces similar results. Additional adjustments were made for age at EDS assessment, the time from EDS assessment to death, and possible confounding effects from other characteristics measured during life, including cigarette smoking, coffee intake, and constipation, with known independent associations with LP or PD.25,26 Analyses are repeated after removing cases of PD and DLB. In instances when EDS frequency is low, logistic regression models were estimated using exact testing methods.27 The association between EDS and LP is also examined within strata of the other sleep-related features. All reported p values are based on 2-sided tests of significance.

Data availability

Restricted access and data-sharing agreements prevent the data from being made publicly available. Data access will be granted within an approved framework of understanding.

Results

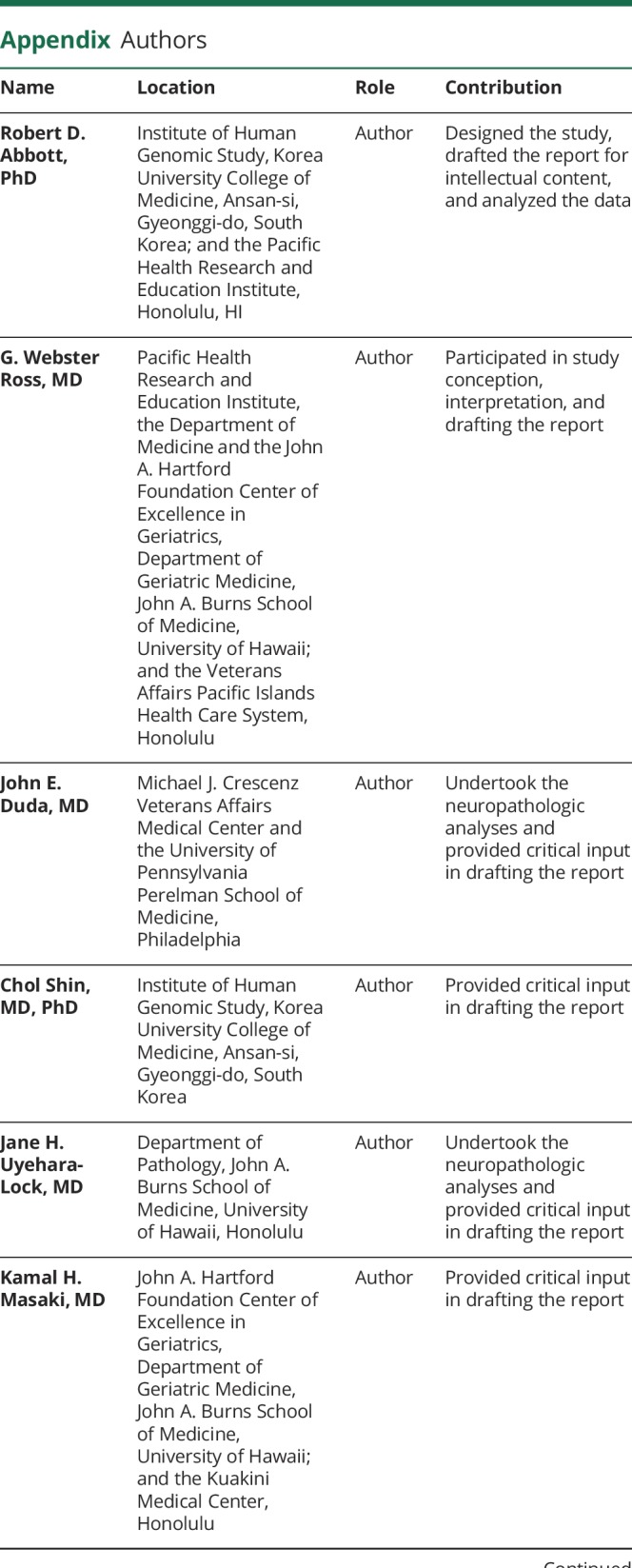

As questionnaires on EDS in the HAAS were not administered until participants were aged 71–93 years, EDS status earlier in life, its duration, and its time of onset relative to postmortem examination are unknown. Among the 211 participants with postmortem examinations and EDS assessments that were made at some time from 1991 to 1999, LP was found in 46% (97/211) of decedent brains. In those with LP, EDS occurred in 29.9% (29/97) of participants vs 17.5% (20/114) when LP was absent. Although the overall excess of EDS in the presence vs absence of LP was statistically significant (p = 0.034), the association between EDS and LP depended on the extent of LP expansion. As seen in table 1, EDS frequency was lower when LP distribution was limited to the olfactory bulb, medulla, and pons (Braak stages 1–2). Its frequency remained low with further expansion into the midbrain, hippocampus, amygdala, and basal forebrain (Braak stages 3–4). Across Braak stages 1–4, EDS occurred in 10.0% (4/40) of decedents. While lower than the frequency of EDS in the absence of LP (17.5%), the difference was not significant (p = 0.258).

Table 1.

Percent of decedents with excessive daytime sleepiness (EDS) according to expanding Lewy pathology (LP) (Braak stage)

As LP expansion increased, however, EDS became significantly more common (p < 0.001). In comparison to those without LP, EDS frequency was doubled (36.7% [11/30], p = 0.023) when LP infiltration reached the anterior cingulate gyrus, insula mesocortex, and midfrontal, midtemporal, and inferior parietal neocortices (Braak stage 5). With further expansion into the calcarine or primary sensory and motor fields of the neocortex (Braak stage 6), frequency increased threefold (51.9% [14/27], p < 0.001).

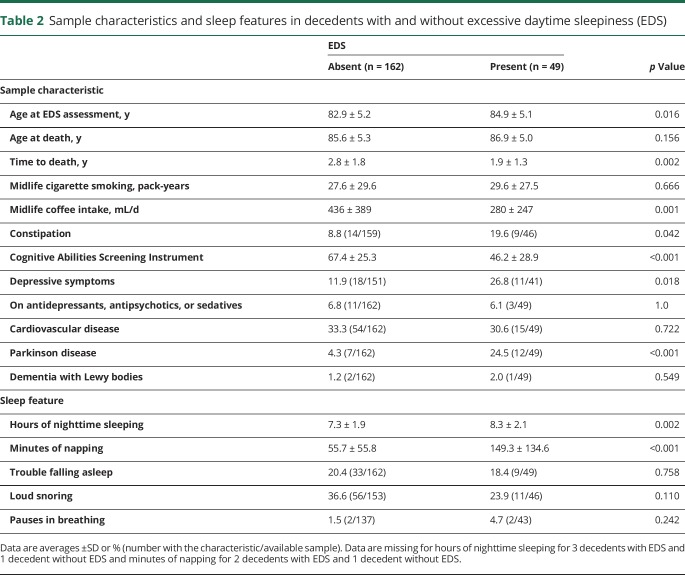

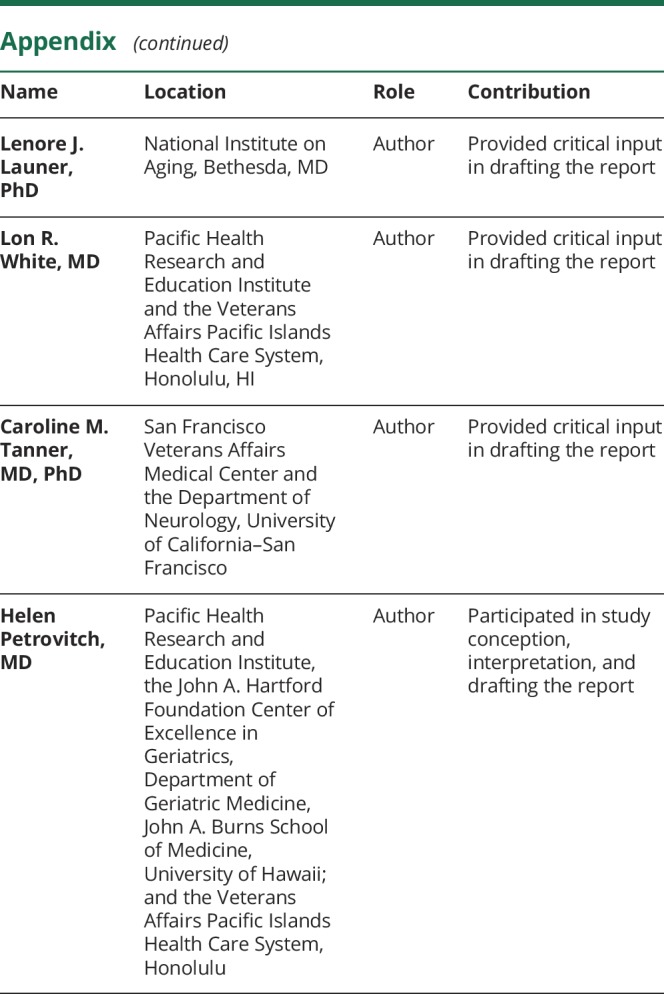

Comparison of possible confounders measured during life between those with and without EDS appear in table 2. In contrast to those without EDS, those with EDS were 2 years older on average at the time of EDS assessment (p = 0.016). While age at death was similar between the groups, the time from EDS assessment to death was longer in those without EDS (2.8 vs 1.9 years, p = 0.002). Midlife pack-years of smoking was also similar between the groups but the sample without EDS consumed more coffee during midlife vs those with EDS (436 vs 280 mL/d, p = 0.001). Those with EDS were twice as likely to have constipation (19.6 vs 8.8%, p = 0.042). Cognitive function between the groups was also different, with CASI performance lower in the presence vs the absence of EDS (46.2 vs 67.4, p < 0.001). In decedents with EDS, frequency of depressive symptoms was more than doubled (26.8 vs 11.9%, p = 0.018), while prevalence of PD was 5 times higher than when EDS was absent (24.5 vs 4.3%, p < 0.001). Use of antidepressants, antipsychotics, and sedatives was similar between those with and without EDS. While not shown in table 2, only 2 of the 12 patients with PD with EDS were on antidepressants, antipsychotics, or sedatives. Among the 7 patients with PD without EDS, none was receiving these medications. Prevalence of cardiovascular disease was similar between the EDS groups, while DLB was too uncommon to provide a meaningful comparison.

Table 2.

Sample characteristics and sleep features in decedents with and without excessive daytime sleepiness (EDS)

Among the sleep-related features, hours of nighttime sleeping in those with EDS was an hour longer on average than in those without EDS (8.3 vs 7.3 hours, p = 0.002). Participants with EDS napped an average of 90 minutes longer than those without EDS (149.3 vs 55.7 minutes, p < 0.001). Associations with the other sleep-related features were less clear.

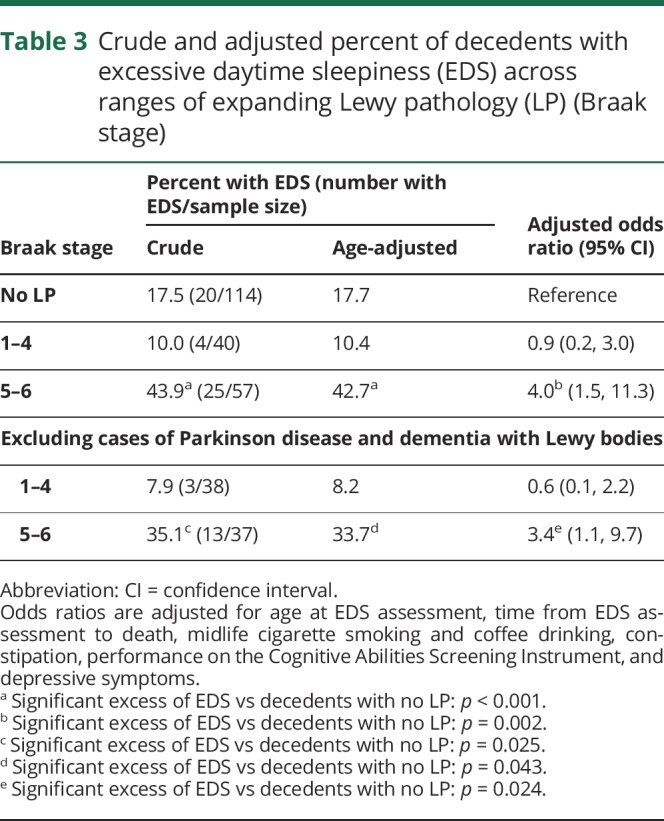

Table 3 attempts to account for the role of possible confounders in explaining the association between EDS and LP that was observed in table 1. As shown, after adjusting for age at the time of EDS assessment, the percent of participants with EDS is unchanged in decedents without LP, in those where LP is limited to Braak stages 1–4, and in those where LP has reached Braak stages 5–6. Creating different groupings of Braak stage or presenting data separately for each stage adds little to these findings. With additional adjustments for time to death and other characteristics measured during life, the odds of EDS was fourfold higher when LP distribution reached the neocortex (Braak stages 5–6) as compared to when LP was absent (95% CI 1.5–11.3, p = 0.002). Findings persisted after removing cases of PD and DLB.

Table 3.

Crude and adjusted percent of decedents with excessive daytime sleepiness (EDS) across ranges of expanding Lewy pathology (LP) (Braak stage)

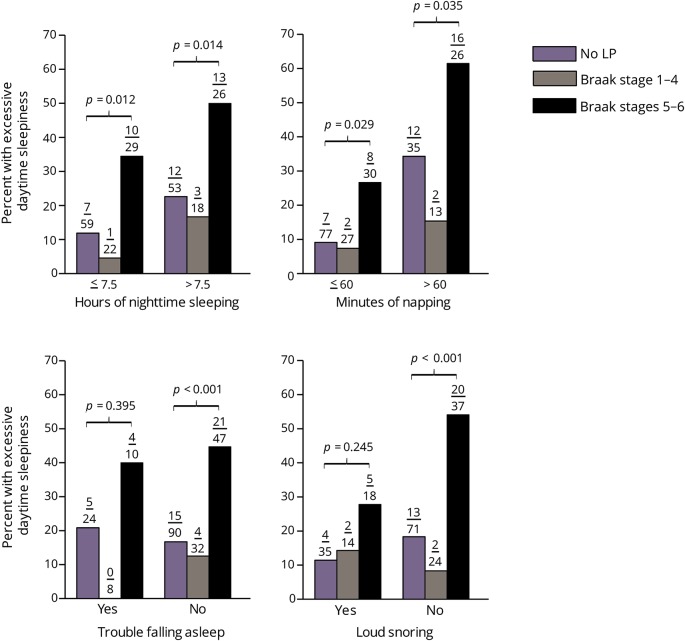

The association between EDS and LP is further examined within strata of the other sleep-related features (figure). Here, EDS frequency is shown for decedents without LP and separately within Braak stages 1–4 and Braak stages 5–6. Data on pauses in sleep are not provided since its occurrence is low (4/180). As can be seen, associations between EDS and LP are similar across the sleep-related strata. In each instance, the percent of decedents with EDS is approximately doubled when LP expansion reaches Braak stages 5–6 vs decedents without LP. A similar excess of EDS for those with more limited LP expansion (Braak stages 1–4) is absent. EDS was the only sleep-related feature having an independent association with the distribution of LP in Braak stages 5–6.

Figure. Excessive daytime sleepiness (EDS) frequency across ranges of expanding Lewy pathology (LP) (Braak stage) within sleep-related strata.

p Values compare the percent of decedents with EDS in the absence of LP vs LP in Braak stages 5–6. There are no significant differences in the frequency of EDS in the absence vs the presence of LP in Braak stages 1–4. Numbers above the bars are the number of decedents with EDS/the sample size. Data are missing for hours of nighttime sleeping for 4 decedents, minutes of napping for 3 decedents, and loud snoring for 10 decedents.

Discussion

Evidence suggests that earlier findings of an association between EDS and PD may be partly explained by a relationship that EDS has with extensive topographic LP expansion.1 As this is a cross-sectional study, mechanisms that explain the relationship between EDS and LP are difficult to identify. While possible explanations include direct or bidirectional pathways, EDS and LP could also evolve simultaneously through an underlying initiating cause. Rather than a direct pathophysiologic link, associations between EDS and LP could be the result of common neurodegenerative processes that have broad effects on brain aging.

It might seem reasonable that EDS could be induced by LP in regions of the brain closely aligned with sleep coordination (Braak stages 2–3) but evidence in support of such a relationship is lacking. There exists the possibility that when EDS was reported in the HAAS, LP distribution could have reached Braak stages 2–3, and with time, it ascended into stages 5–6, where it was ultimately identified at the time of autopsy. Duration of EDS could have been longer in those with extensive LP expansion as time is needed for LP to progress through lower regions of the brain.5 Although the duration of EDS cannot be determined, LP was not the cause of EDS in 41% (20/49) of EDS cases, as LP was absent at the time of autopsy. For the remaining cases, the order of occurrence of EDS relative to the development of LP is unknown.

In contrast to the inducement of EDS by LP, EDS could predate or cause LP through the same mechanisms that link sleep with enhancements in glymphatic clearance of β-amyloid.28–30 Similar pathways could augment the clearance of tau and α-synuclein.28–30 Based on PET neuroimaging in a relatively large sample of humans without dementia, EDS was longitudinally associated with increased deposition of β-amyloid.31 Efficiency in glymphatic clearance of toxic proteins could also have regional variation, possibly contributing to the association between EDS and LP in neocortical areas that failed to appear elsewhere in the brain. Specific regions of the brain also show increased susceptibility to the accumulation of β-amyloid from EDS.31 Some of these regions are in close proximity to those that correspond with advanced PD staging (Braak stages 5–6).

While this report provides evidence that the neocortex is especially vulnerable to potential adverse relationships between EDS and LP, the available sample size used to address this issue is small. As is often typical of autopsy studies, generalizability is uncertain. In spite of these limitations, data from the HAAS have some positive attributes. The HAAS has the advantage of having accumulated a large series of PD cases in a free-living community-based sample. Studies of PD are generally difficult to undertake because of its low prevalence compared to Alzheimer disease. Brain surveys of LP in multiple brain regions are also rare among such samples.

Although EDS is the only sleep feature in the HAAS with a consistent relationship with PD and LP,1 it is also an imprecise marker of underlying sleep disorders, with possibly numerous causes.31 Whether EDS is secondary to a loss of sleep or other sleep disorder cannot be addressed in the HAAS. Regardless of having long or short nighttime sleep durations, those with EDS could have experienced more frequent episodes of wakefulness and poorer sleep quality than those without EDS. It seems interesting that the association between EDS and LP persists in participants with both short and long nighttime sleep times and between strata of other sleep-related features (figure). One might have expected that if sleep is neuroprotective, the association between EDS and LP should weaken with increased nighttime sleep duration. Prolonged sleep duration, however, may not be neuroprotective as short and long sleep time can increase the risk of cognitive impairment, dementia, and death.32–34 EDS that remains unresolved after long nighttime sleep times could be a marker of a more serious sleep disturbance where associations with LP seem to persist (figure).

Validation of the questionnaire used to assess EDS is also uncertain, although EDS in the HAAS has been shown to have associations with chronic medical conditions that often coexist with sleep disruptions.9 Earlier reports from the HAAS also describe associations of EDS with cognitive decline and dementia.35,36 Measures of EDS across studies, however, can vary widely. In the elderly, EDS frequency is likely underestimated as it is often poorly recognized in subjective reporting.37 In our earlier study on incident PD,1 EDS frequency was 7.9%, markedly lower than the reported prevalence of 17% in the Cardiovascular Health Study.12 Others report frequencies that can range from 1% to 47% in healthy controls or in participants without PD.10,11,37,38 For those with PD, prevalence can vary from 15% to 76%. In our current autopsy sample, EDS frequency is 23.2% (49/211). Although variation in EDS assessment is high, it remains the most common reason for referral to neurology sleep clinics among all sleep disorders.39 Combined with the finding that EDS has associations with PD and LP, improvements in the measurement of EDS and identifying its cause and relationship with other sleep disorders are clearly warranted.

Glossary

- CASI

Cognitive Abilities Screening Instrument

- CI

confidence interval

- DLB

dementia with Lewy bodies

- EDS

excessive daytime sleepiness

- HAAS

Honolulu–Asia Aging Study

- HHP

Honolulu Heart Program

- LP

Lewy pathology

- PD

Parkinson disease

Appendix. Authors

Study funding

Supported by a grant from the Brain Pool Program from the National Research Foundation of Korea (no. 2018H1D3A2065629), by a contract (N01-AG-4-2149) and grants (1 UO1 AG19349 and 5 R01 AG017155) from the US National Institute on Aging, by a contract (N01-HC-05102) from the US National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, by a grant (5 R01 NS041265) from the US National Institute of Neurologic Disorders and Stroke, by a grant from the US Department of the Army (DAMD17-98-1-8621), by the Office of Research and Development, Medical Research Service, US Department of Veterans Affairs, by the Kuakini Medical Center, Honolulu, HI, and in part by the Intramural Research Program of the US National Institute on Aging. The information contained in this article does not necessarily reflect the position or the policy of the US Government, and no official endorsement should be inferred.

Disclosure

The authors report no disclosures relevant to the manuscript. Go to Neurology.org/N for full disclosures.

References

- 1.Abbott RD, Ross GW, White LR, et al. Excessive daytime sleepiness and the subsequent development of Parkinson's disease. Neurology 2005;65:1442–1446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Markesbery WR, Jicha GA, Liu H, Schmitt FA. Lewy body pathology in normal elderly subjects. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 2009;68:816–822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Del Tredici K, Rub U, De Vos RA, Bohl JR, Braak H. Where does Parkinson disease pathology begin in the brain? J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 2002;61:413–426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Braak H, de Vos RAI, Bohl J, Tredici KD. Gastric α-synuclein immunoreactive inclusions in Meissner's and Auerbach's plexuses in cases staged for Parkinson's disease-related brain pathology. Neurosci Lett 2006;396:67–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Braak H, Ghebremedhin E, Rüb U, Bratzke H, Del Tredici K. Stages in the development of Parkinson's disease-related pathology. Cell Tissue Res 2004;318:121–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.White L, Petrovitch H, Ross GW, et al. Prevalence of dementia in older Japanese-American men in Hawaii: the Honolulu-Asia aging study. JAMA 1996;276:955–960. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kagan A, Harris BR, Winkelstein W, Jr, et al. Epidemiologic studies of coronary heart disease and stroke in Japanese men living in Japan, Hawaii and California: demographic, physical, dietary and biochemical characteristics. J Chronic Dis 1974;27:345–364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Milber JM, Noorigian JV, Morley JF, et al. Lewy pathology is not the first sign of degeneration in vulnerable neurons in Parkinson disease. Neurology 2012;79:2307–2314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Babar SI, Enright PL, Boyle P, et al. Sleep disturbances and their correlates in elderly Japanese American men residing in Hawaii. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2000;55A:M406–M411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kumar S, Bhatia M, Behari M. Sleep disorders in Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord 2002;17:775–781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Factor SA, McAlarney T, Sanchez-Ramos JR, Weiner WJ. Sleep disorders and sleep effect in Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord 1990;5:280–285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Newman AB, Enright PL, Manolio TA, Haponik EF, Wahl PW. Sleep disturbance, psychosocial correlates, and cardiovascular disease in 5201 older adults: the Cardiovascular Health Study. J Am Geriatr Soc 1997;45:1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Foley DJ, Monjan AA, Brown SL, Simonsick EM, Wallace RB, Blazer DG. Sleep complaints among elderly persons: an epidemiologic study of three communities. Sleep 1995;18:425–432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Petrovitch H, White LR, Ross GW, et al. Accuracy of clinical criteria for AD in the Honolulu-Asia Aging Study, a population-based study. Neurology 2001;57:226–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ross GW, Petrovitch H, Abbott RD, et al. Parkinsonian signs and substantia nigra neuron density in decendents elders without PD. Ann Neurol 2004;56:532–539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McKeith IG, Galasko D, Kosaka K, et al. Consensus guidelines for the clinical and pathologic diagnosis of dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB): report of the consortium on DLB international workshop. Neurology 1996;47:1113–1124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ward CD, Gibb WR. Research diagnostic criteria for Parkinson's disease. Adv Neurol 1990;53:245–249. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tillotson JL, Kato H, Nichaman MZ, et al. Epidemiology of coronary heart disease and stroke in Japanese men living in Japan, Hawaii, and California: methodology for comparison of diet. Am J Clin Nutr 1973;26:177–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hankin JH, Nomura A, Rhoads GG. Dietary patterns among men of Japanese ancestry in Hawaii. Cancer Res 1975;35:3259–3264. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McGee D, Rhoads G, Hankin J, Yano K, Tillotson J. Within person variability of nutrient intake in a group of Hawaiian men of Japanese ancestry. Am J Clin Nutr 1982;36:657–663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Teng EL, Hasegawa K, Homma A, et al. The Cognitive Abilities Screening Instrument (CASI): a practical test for cross-cultural epidemiological studies of dementia. Int Psychogeriatr 1994;6:45–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kohout FJ, Berkman LF, Evans DA, Cornoni-Huntley J. Two shorter forms of the CES-D (Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression) depression symptoms index. J Aging Health 1993;5:179–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huh JY, Ross GW, Chen R, et al. Total and differential white blood cell counts in late-life predict 8-year incident stroke: the Honolulu Heart Program. J Am Geriatr Soc 2015;63:439–446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wahab N, Chen R, Curb JD, Willcox BJ, Rodriguez BL. The association of fasting glucose, insulin, and C-peptide, with 19-year incidence of coronary heart disease in older Japanese-American men: the Honolulu Heart Program. Geriatrics 2018;3:22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ross GW, Abbott RD, Petrovitch H, et al. Association of coffee and caffeine intake with the risk of Parkinson disease. JAMA 2000;283:2674–2679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Abbott RD, Ross GW, Petrovitch H, et al. Bowel movement frequency in late-life and incidental Lewy bodies. Mov Disord 2007;22:1581–1586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mehta CR, Patel NR. Exact logistic regression: theory and examples. Stat Med 1995;14:2143–2160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mendelsohn AR, Larrick JW. Sleep facilitates clearance of metabolites from the brain: glymphatic function in aging and neurodegenerative diseases. Rejuvenation Res 2013;16:518–523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xie L, Kang H, Xu Q, et al. Sleep drives metabolic clearance from the adult brain. Science 2013;342:373–377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Holth J, Patel T, Holtzman DM. Sleep in Alzheimer's disease: beyond amyloid. Neurobiol Sleep Circadian Rhythms 2017;2:4–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Carvalho DZ, St Louis EK, Knopman DS, et al. Association of excessive daytime sleepiness with longitudinal β-amyloid accumulation in elderly persons without dementia. JAMA Neurol 2018;75:672–680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liang Y, Qu LB, Liu H. Non-linear associations between sleep duration and the risks of mild cognitive impairment/dementia and cognitive decline: a dose-response met-analysis of observational studies. Aging Clin Exp Res 2018;31:309–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ohara T, Honda T, Hata J, et al. Association between daily sleep duration and risk of dementia and mortality in a Japanese community. J Am Geriatr Soc 2018;66:1911–1918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cappuccio FP, D’Elia L, Strazzullo P, Miller MA. Sleep duration and all-cause mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. Sleep 2010;33:585–592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Foley DJ, Monjan AA, Masaki KH, et al. Associations of symptoms of sleep apnea with cardiovascular disease, cognitive impairment, and mortality among older Japanese-American men. J Am Geriatr Soc 1999;47:524–528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Foley D, Monjan A, Masaki K, et al. Daytime sleepiness is associated with 3-year incident dementia and cognitive decline in older Japanese-American men. J Am Geriatr Soc 2001;49:1628–1632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brodsky MA, Godbold J, Roth T, Olanow CW. Sleepiness in Parkinson's disease: a controlled study. Mov Disord 2003;18:668–672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tandberg E, Larsen JP, Karlsen K. Excessive daytime sleepiness and sleep benefit in Parkinson's disease: a community-based study. Mov Disord 1999;14:922–927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kretzschmar U, Werth E, Sturzenegger C, Khatami R, Bassetti CL, Baumann CR. Which diagnostic findings in disorders with excessive daytime sleepiness are really helpful? A retrospective study. J Sleep Res 2016;25:307–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Restricted access and data-sharing agreements prevent the data from being made publicly available. Data access will be granted within an approved framework of understanding.