Abstract

In the field of audiology, change is inevitable: changes in technologies with hearing devices, changes in consumer knowledge, and changes in consumer-driven solutions. With these changes, the audiologist must adapt to meet the needs of the consumer. There are potential predictors that the audiologist could use to determine who is more likely to pursue and use amplification; by using these data, the audiologists may increase their productivity and increase patient satisfaction. The goal of this article is to investigate the MarkeTrak 10 (MT10) data to determine the trends in adoption and use of hearing aids as well as examine predictive factors that can be used to determine hearing aid adoption.

Keywords: hearing aid adoption, hearing aid use, satisfaction

In hearing health care, the question is why some people pursue amplification while others do not. Approximately 38 million individuals, representing 10% of the U.S. population, have some degree of hearing loss. Data from MT10 suggest that more than 35 million adults could benefit from using hearing aids for some listening conditions; yet, hearing aid adoption by age in this survey ( Fig. 1 ) shows 41.6% of those 65+ with hearing difficulty currently have a hearing aid, along with 22.93% of 35 to 64 year-olds and 29.5% of those younger than 35 years. Data from this survey, along with previous MarkeTrak surveys, suggest there are approximately 11 million nonadopters with moderate-to-severe hearing loss.

Figure 1.

Hearing aid adoption rate by age.

Some industry leaders believe that the number of those who do not use hearing aids is lower due to an overestimation of the pool of potential hearing aid consumers, as not everyone with a hearing loss needs or believes that they need a hearing aid. Regardless, the rate of nonadoption is significant. Still, the rate of hearing aid adoption has increased over time. MarkeTrak9 2014 (MT9) reported a 30.2% hearing aid adoption rate for the sample, while MT10 reports a 34.1% adoption rate. 1 Factors influencing adoption rate may include increased access to hearing devices, the expanding definition of hearing device, reduction of stigma toward ear-level devices, or increase in patient knowledge related to the negative impact of untreated hearing loss. Since many people with hearing difficulties still do not use amplification, it is of interest to examine if there are predictive variables related to who is likely to pursue hearing aids and audiologic services.

Demographics

Many demographic characteristics were collected in the MT10, several with direct relevance to clinicians. In line with previous MarkeTrak reports, the majority of those with self-reported hearing loss are older than 60 years (see Fig. 2 and Table 1 ). 2 3 Nonowners are younger than owners whose mean age is 66 years. Most hearing aid owners are first-time purchasers, making this purchase on average at 59 years of age, and have had hearing aids for several years. Men report higher rates of hearing loss (12.8%) than women (8.9%), which is also consistent with previous reports. These data may help audiologists with targeting the demographic most likely in need of a solution or willing to pursue a solution.

Figure 2.

Hearing difficulty by age.

Table 1. Reported Age Demographics.

| Age estimates (from part 2) | All ages ( n = 3,132) | |

|---|---|---|

| Mean | Median | |

| Current age of individuals with hearing difficulty ( n = 3,132) | 58 | 61 |

| Current age of nonowners ( n = 2,163) | 54 | 57 |

| Current age of all HA owners ( n = 969) | 66 | 71 |

| Age when all owners got 1st HA (n = 845) | 59 | 65 |

| Current age of first-time purchasers ( n = 566) | 65 | 70 |

| Age when first-time purchasers got HA | 62 | 67 |

| Current age of repeat purchasers (on 2nd+ HA now) ( n = 381) | 69 | 75 |

| Age when repeat owners got 1st HA | 56 | 62 |

Abbreviation: HA, hearing aid.

How may a person's demographic characteristics predict hearing aid purchase? The data and descriptions throughout this report, unless otherwise attributed, are from survey (therefore self-reported) responses from MT10. Approximately 314 in 1,000 people older than 65 years have a perceived hearing loss and 40 to 50% of people 75 and older have a hearing loss. One in six baby boomers (age 41–59), or 14.6%, report hearing problems. One in 14 Generation Xers (ages 29–40), or 7.4%, already perceive hearing loss. 4 The rates of hearing aid purchase also increase with age (see Fig. 2 ). The rates of hearing aid adoption for adults younger than 35 is higher than those who are 35 to 64 years old. It is interesting to consider the potential reasons for the decrease during middle age. Likely, those who are younger than 35 were identified as children who have worn devices since childhood. It is also possible that those who are under the age of 35 who report hearing loss have more severe hearing difficulty requiring hearing aids as compared with those who are 35 to 64 years of age. Those with more severe degrees of self-perceived hearing loss are more likely to pursue amplification ( Fig. 3 ). Previous data from MarkeTrak along with MT10 suggest that for individuals with perceived moderate hearing loss, the usage rate is over 60% for individuals older than 75 years, but only around 20% for people with perceived hearing loss in the age range of 55 to 64 years. 3 The age range of 55 to 64 would have to have self-perceived severe/profound hearing loss before their hearing aid adoption would exceed 60%. Data suggest that asking a patient to rate his or her hearing on a scale of 1 to 10 was a predictor in hearing aid purchase. 5 MT10 data support this method. When someone reports that they have greater difficulty hearing and they are more likely to pursue amplification, this is independent of their measured hearing status.

Figure 3.

Reported level of hearing loss by hearing aid purchase.

Men are more likely to have self-perceived hearing loss with 12.8% of men reporting hearing loss while only 8.9% of women reporting hearing loss. When comparing the rate of hearing aid adoption, 33.9% of both men and women report that they have purchased hearing devices. This has remained consistent across MarkeTrak studies but diverges from one study that reported there was a greater reported use of hearing aids among males. 6 They attributed this difference to the variation in the configuration of hearing loss with men having more high frequency sloping hearing loss as compared with the flat hearing loss of the women in their study. In the MT10 data, the degree of hearing loss was also investigated. As was suggested previously, those who report a higher degree of hearing loss are more likely to pursue amplification; MT10 did not investigate configuration specifically given that these survey results are based on self-perceived hearing difficulty rather than audiometric data. So, while audiologists may appear to see more male patients than women, the rates of adoption are consistent across genders according to the MT10 survey, but degree or configuration of hearing loss may have an effect on whether someone pursues amplification.

Those who have amplification report having their hearing loss longer than those who do not have amplification. On average, people with hearing loss today report becoming aware of it approximately 12 years ago. Those who have amplification have had self-perceived hearing loss longer (14.6 years) as compared with nonowners reporting 10.5 years of hearing difficulty, but this may be explained in part by owners being older than nonowners. It is likely that someone who has had perceived hearing loss longer has a greater degree of hearing loss and would be more likely to pursue amplification than the person with a lesser degree of perceived hearing loss. These data are consistent with previous MarkeTrak data. MarkeTrak asked patients how long after they learned they had hearing loss did they pursue amplification. 2 That data suggested that hearing aid owners pursued amplification 6.7 years after they were diagnosed, while nonowners reported 10.5 years of knowing they had a hearing loss. While this is a different question than reported hearing problems, it suggests that there is something fundamentally different for those who pursue amplification, and knowledge or perception of hearing loss does not answer the entire question.

Cost is often discussed as a limiting factor to amplification purchase. We compared MT10 data to EuroTrak data to shed light on this assertion. Most of those people surveyed in EuroTrak have access to no cost or low-cost amplification as part of their national health care plans. 7 Respondents to EuroTrak reported 41.6% adoption rate, while MT10 reports 34.1%. 7 There is only a 7% difference; this does not appear to be as stark of a contrast as would be expected if lack of adoption were due to cost alone. Specifically looking at nonowners (see Table 2 ), those in the top 50% of self-perceived hearing loss (worse hearing) are slightly older, have a lower income, less college education, and are less likely to be retired than those who are in the bottom 50% loss (better hearing). This could suggest that for those with worse perceived hearing loss who do not have any device, income may have an impact on their decision to pursue amplification. Combined, these data suggest that if a person has a significant perception of hearing loss and knows they need a hearing aid, cost may be the reason that they do not have one. However, if they do not perceive significant hearing difficulty and do not have a hearing device, cost is not likely the sole reason for not pursuing amplification.

Table 2. Reported Demographic Information for HA Nonowners.

| Demographics | HA nonowners | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| All nonowner ( n = 2,132) | Top-50% loss segments ( n = 904) | Bottom-50% loss segments ( n = 1,259) | |

| Median age | 57 | 58 | 55 |

| Average age | 54 | 57 | 52 |

| % Male | 58% | 55% | 60% |

| % Married | 58% | 57% | 58% |

| % College degree | 32% | 25% | 37% |

| % Retired | 38% | 42% | 35% |

| % Working (FT or PT) | 43% | 35% | 49% |

| Median income | $55.5K | $49.7K | $60.1K |

| Average income | $67.3K | $61.9K | $71.3K |

Abbreviations: HA, hearing aid; FT, full time; PT, part time.

Outside of Europe and other national health care plans, some people can get hearing aids through their health insurance plans. In MT10, people were asked about their likelihood of pursuing amplification if they had insurance coverage for devices (see Fig. 4 ). When asked, people report that they are more likely to pursue hearing aids in the next 2 years if they have insurance coverage. The rates of the likelihood of adoption increase with increased rates of coverage. However, data from the Department of Veteran's Affairs, where hearing aids are free to eligible veterans, suggest that there is a small percentage of people who are more likely to get hearing aids when they are provided, but, like EuroTrak, there was not a sharp increase in adoption when hearing aids are provided at no cost. 7 8 These data suggest that people report that they would get hearing aids if they were mostly or fully covered by insurance, but their actual adoption (action) may not materialize. For some, it appears that the cost of the hearing devices does inhibit their ability to acquire devices; however, this does not appear to be the only reason that they do not pursue amplification.

Figure 4.

Reported likelihood of purchasing hearing aids in the next 2 years.

As far as predictive factors related to demographics, age is a predictor of hearing aid adoption; those who are older are more likely to pursue amplification. Additionally, those who have higher self-perception of hearing loss are more likely to pursue amplification, if they have the finances to do so. While audiologists may see more men than women due to men having higher rates of hearing loss, the actual rate of amplification purchase is similar across men and women. It is encouraging that the rate of hearing aid adoption is steadily increasing over time from 30.2 to 34.1% in the MT10 data. It may be useful for audiologists to integrate these demographic predictors in their presentations to patient when describing hearing loss and amplification options.

Personal Intervening Factors

While some demographic characteristics predict hearing aid adoption, there are also many intrinsic factors that could be used to forecast if a person is more likely to purse amplification.

Many audiologists start a clinical visit with the question “What brings you in today?.” This question often provides insight into motivation for making the appointment. Whether a person is brought in by their family, referred by their primary care physician, or decided to make the appointment themselves, MT10 data suggest that people are more likely to purchase devices when they are willing to admit they have a hearing loss. This line of questioning is in agreement with data from Palmer et al who reported that people are more likely to purchase devices when they recognize that they have a hearing loss and are motivated to do something about it. 5 While the motivation of making an appointment may not be a predictor of the intent to buy hearing aids, the recognition that they have a problem may be a predictor of taking action. Very often motivation comes from the influence of family and friends. This is the same reason that people who seek a solution for other problems, such as psychological problems, alcoholism, or drug addiction; personal need recognition, whether internally or externally motivated, are more likely to seek a solution and follow through with recommendations.

Boatman et al suggested that most bedside testing and asking someone if they have hearing loss are inaccurate assessment of hearing ability; however, asking someone how they hear in noise is a better predictor of hearing loss. 9 In the MT10, researchers assessed participants' self-perceived situational listening difficulty. Participants were asked to assess their difficulty in a variety of situations without the use of their hearing aids or other devices. As shown in Table 3 , respondents report that hearing in noise remains the most common complaint. The rates of concern are higher in those people who are hearing aid owners; however, as discussed previously, it is possible that these people are more aware of their hearing difficulty. Given these data, asking people how well they hear in noise may be a predictor of hearing loss, but does not appear to be a strong predictor in actual hearing aid purchase. However, asking questions about specific speech-in-noise situations, such as hearing a speaker in a large room or hearing while watching the TV at a normal volume, may be better questions for counseling a person toward purchasing hearing aids to create a listening solution in these situations.

Table 3. Reported Situational Difficulty without Aid Use.

| Key BHI hearing check items Top-2 agreement—5-point scale (when not using HA or other device) |

Total ( n = 3,132) | HA owners ( n = 969) | Nonowners ( n = 2,163) |

|---|---|---|---|

| I have trouble hearing conversations in a noisy background | 87% | 93% | 84% |

| Family members and friends have told me they think I may have hearing loss | 78% | 84% | 75% |

| I have trouble following the conversation when 2+ people are talking | 71% | 80% | 66% |

| I have trouble understanding things on TV | 66% | 78% | 60% |

| I have trouble understanding the speaker in a large room | 59% | 75% | 50% |

| I get confused about where sounds come from | 46% | 55% | 42% |

Abbreviations: BHI, Better Hearing Institute; HA, hearing aid.

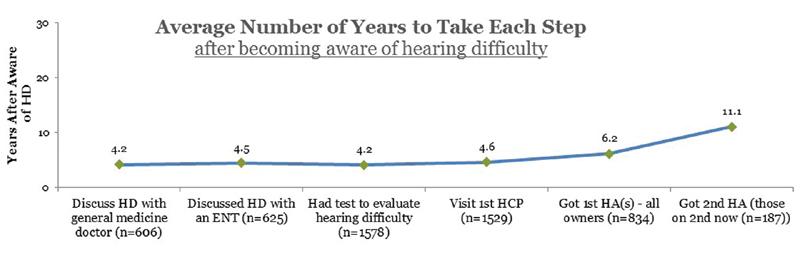

Seventy-eight percent of people report that family members have told them they may have hearing loss ( Table 3 ). MT10 sought to determine if family members pushing a person toward devices was an influencing factor in seeking hearing aids. Specifically, MT10 asked people if the person who encouraged them toward hearing device purchase made them more or less likely to seek a solution to their hearing problems (see Fig. 5 ). It appears that device owners are more likely to listen to the suggestions of their physicians, ENTs, and hearing health care professionals (HHCP). Furthermore, MT10 data suggest that recommendations for professionals whose job is directly related to hearing (e.g., ENT, HHCP) have a greater influence on solution seeking than advice from a general physician. MT10 data also suggest that most people (61%) classify an HHCP to be an audiologist. Those respondents who did not pursue amplification were not as influenced by any professional and were equally motivated and not motivated. On average, people wait over 4 years after perceiving hearing loss prior to seeking information (see Fig. 6 ) and 6 years post confirming their hearing loss before getting their first hearing aid. Interestingly, there is a 1.6-year delay between seeing the HHCP and getting their first hearing aid.

Figure 5.

Motivation to seek a solution to hearing loss based on who recommended it.

Figure 6.

Average number of years after noticing a hearing loss to seek solution.

The MT10 survey attempted to determine what path people took to purchase hearing aids. Participants who reported hearing loss were asked with whom they discussed hearing loss/hearing aids, who confirmed their hearing loss and recommended aids, and whether the individual purchased the aids (see Fig. 7 ). Of those who report that they have hearing loss, 78% report that they have discussed it with a health care professional. The remaining 22% of those who report hearing loss but had not sought professional help may be in an earlier stage of contemplation concerning pursuit of help. This follows most medical data suggesting that approximately 25% of people with a medical condition are in the contemplation phase of health change. 10 While there are many theories of change behavior, most models include precontemplation, contemplation, preparation, action, and maintenance. In relation to audiology, precontemplation would be patients who have hearing loss but either do not recognize or acknowledge that they have it. Contemplation would be a patient who identifies that they have a hearing problem but are not ready to seek solutions (the 22%). The next group, preparation, includes individuals seeking information about hearing solutions. MT10 data suggest that 27% of individuals report that they discuss their hearing difficulties with their physician as their first point of information seeking. However, of those 27% who discussed their hearing loss with their physician, only 17% of physicians recommended hearing aids and only 7% of the people who reported their physician recommended hearing aids ultimately purchased them. These data suggest that although audiologists may put time into educating physicians about hearing loss and appropriate referrals, investing a lot of time into getting referrals from a physician may not materialize into hearing aid purchase.

Figure 7.

Reported journey to hearing aid adoption.

The low rate of physician referral to audiology even when hearing loss is suspected or confirmed has been documented by several studies and is not surprising. 11 Interestingly, and maybe more concerning, the rate of hearing aid recommendation is the same from an ENT physician despite documentation of hearing loss more often. ENTs were the first point of entry for those people in the preparation phase for 24% of those surveyed. Both ENTs and general physicians recommended only 12% of people identified as having hearing problems consider pursuing hearing aids. The reasons for not recommending hearing aids for patients with confirmed hearing loss is unknown; however, the similar rate of referral is interesting given that ENTs should, in theory, have a better understanding of the importance of treating hearing loss. Alternatively, 60% of people reported that the first person they sought information from is an HHCP. In this case, 52% had confirmed hearing loss, and 41% reported that hearing aids were recommended. These data suggest that the audiologist's energy should be focused on patient education and motivating patients to come to their office when a hearing loss is suspected. If they can get a person in the preparation phase in their door to discuss hearing aids, they are more likely to move into the action phase of pursuing a solution. The theories of change suggest that after a person has acted, they then move into the maintenance phase, and then eventually will go back through the cycle when the time comes to get new devices. Data on motivation and point of entry could be used for audiologists to focus their energy on education and marketing. Patients are more likely to buy hearing aids if they recognize they have a hearing loss and are seeking information about it; if they get that information from an HHCP first, they are more likely to act on their concerns of hearing loss and seek treatment.

In some cases, patients may be influenced to pursue hearing aids or move into the action phase of change if they have other health conditions. Research on other health care conditions suggests that if a person has a life-altering condition, such as diabetes or history of cancer, the general practitioner is more likely to focus on that condition in their appointment than screening for other conditions. 12 However, a person with a history of concurrent medical conditions may be more likely to seek health care than their healthy counterparts. So, it is of interest if other health conditions may predict a person's likelihood of seeking a solution to hearing concerns. Other than hearing loss and tinnitus, 46.9% of respondents reported that they had some other medical condition. When dividing these by age categories, as expected, respondents who were older reported a higher percentage of other medical conditions. When investigating the relationship between hearing loss and cognition, in this survey, those with self-perceived hearing loss were over four times more likely to report cognitive or memory concerns than those without hearing concerns (see Fig. 8 ). These data are consistent with the large body of literature relating hearing loss and cognition. 13 14 Those with cognitive concerns are more likely to report hearing loss; however, the symptoms of undiagnosed hearing loss overlap with the symptoms of cognitive decline. 15 Therefore, it is possible that those with cognitive concerns are more likely to dismiss the symptoms of hearing loss as cognitive aging; it is not until those concerns begin to have a daily impact that they seek solutions. If those who have hearing loss are more likely to report cognitive concerns and memory problems, audiologists may consider conducting cognitive screening to personalize their rehabilitation and approaches to education. Cognitive screening typically consists of oral questionnaires and the individual should use amplification (e.g., non-custom amplifier in the office) for the purpose of completing this type of screening.

Figure 8.

Reported rates of hearing and memory concerns.

When looking at health care conditions as a whole, as reported previously, 61.5% of the respondents reported a concurrent medical condition. Participants were asked if they had any of the following conditions: falling/balance issues, poor eyesight, depression, loneliness/social isolation, diabetes, high blood pressure, arthritis, back problems, or any type of cancer. Furthermore, if the respondent reported more than one of the conditions, they were four times more likely to report hearing difficulty. Of note, it is possible that those people who are willing to acknowledge they have hearing loss are also more likely to report that they have other medical conditions and seek treatment for those conditions. On the other hand, HHCPs can use the higher rates of comorbid conditions to provide a holistic approach to rehabilitation and to target other health care providers who work with these populations to provide education about the impact of untreated hearing loss.

As people live longer, the incidences of hearing loss, vision loss, and the loss of both senses are increasing. Loss of both senses can markedly diminish quality of life. Previous studies have shown a relationship between sensory loss and symptoms of depression particularly when the person reports hearing and vision loss. 16 17 Dual sensory impairment reduces cognitive ability and increases social isolation. 18 19 When discussing hearing aids and hearing aid options, vision impairment should be considered, as 67.9% of respondents reported vision impairment and 58.6% of people with self-reported hearing loss also reported vision impairment.

Experience

Previous experience with devices or seeing others' experiences may be a predictor in hearing aid purchase and use. Another article in this edition of Seminars focuses on PSAP (personal sound amplification device) use; however, MT10 data suggest that of the 40.6% of people who report hearing loss and own a device, 31% have only hearing aids (see Fig. 9 ). A PSAP may have been the gateway into the purchase of hearing aids and does appear to influence their current device satisfaction. As stated earlier, the majority of those surveyed in this study were first-time hearing aid users. However, previous hearing aid use does influence a person's perception of and satisfaction with hearing aids. The chapter by Dr. Erin Picou covers features and programming of a hearing aid that may influence a patient's satisfaction.

Figure 9.

Reported amplification product adoption rate. Abbreviations: HA, hearing aid; PSAP, personal sound amplification product.

There remains the question of how a patient finds out about hearing aids and makes their decisions about hearing aids. MT10 asked patients what route they used to find information. Thirty-eight percent of respondents report that they actively search for information after they become aware of their hearing loss. Most individuals who search (63%) report using online platforms to search for information including Google, while others are influenced by print ads (25%). A few (18%) reported that they were influenced by TV. For online personal connectivity platforms, over half (61%) are active on social media, 90% of respondents report that they have and use a Facebook account, followed by YouTube at 49%. This suggests that if an audiologist uses online advertising, Facebook advertising may increase their visibility. Furthermore, having a clinic Facebook page may help with patients locating the clinic. While print ads and offering discounts do influence some people to seek audiologic services, online advertising appears to be the most effective way to gain visibility to potential patients. When evaluating a clinic or product, 40% of participants report that they ask their friends, family, and physicians about hearing aids. Those who are actively pursuing options are more likely to search and be influenced by advertising. MT10 reports that 69% of those searching were specifically looking to find information about hearing loss and 42% were looking to find out about hearing aids sold by an HHCP; a much lower number reported that they sought information about a specific brand of hearing aids. Only 44% of owners of hearing aids can name the brand of their current hearing aids. These data suggest that once they found their HHCP, they left the decisions to the professional. When looking at the small group that took action as a response to advertising (6%), 48% reported that direct mailings prompted them to make the hearing assessment appointment; this is much higher than any other type of print ad, but, all in all, the proportion responding to any kind of advertising is small. However, as discussed previously, many more people use social media and word-of-mouth to gain information about hearing aids, hearing loss, and HHCP practices. Overall the usage of social media is a significant tool for individuals with hearing loss as they seek information prior to their purchase of hearing aids. Some look at PSAP devices, but most are current owners of hearing aids. PSAP devices may influence some people, but not the current majority of hearing aid owners. These data suggest that audiologists have the largest impact on the purchase once the patients enter the office.

Clinic

As discussed previously, hearing aid owners are directed to an HHCP office by a variety of means: physician, ENT, friend, print ad, online advertising, etc. Once a person has decided to seek a hearing loss solution, they may be influenced by the clinic and the health care provider. MT10 sought to determine information about the participant's experience at their HHCP clinic.

MT10 initially sought to determine why a person made the initial appointment for those who reported some specific event that triggered their appointment and who also reported a specific referral source. MT10 respondents noted several specific meaningful situations that they identified as the trigger for making an appointment with their HHCP (see Table 4 ). When they sought a HHCP referral, often (52%) they found their specific HHCP through a friend referral. However, those who reported that they were told to seek a HHCP by a friend were less likely to purchase hearing aids. This suggests that if the patient does not make the appointment themselves where they see the need for the HHCP appointment, they are less likely to purchase aids. Over a third of respondents report that they have dreaded social situations, which could lead to social isolation and further impact the patient's lives. To address these concerns and ensure that patients do see improvement through the use of hearing devices, many audiologists ask patients about specific situations in which they would like to hear better through a questionnaire like the Client Oriented Scale of Improvement (COSI). This strategy could appear to meet the needs of the patient, as those specific situations are why they came for assistance; additionally, it appears that if the patient is the one seeking the appointment, they are more likely to purchase devices. Furthermore, if they feel their hearing concerns are validated, they may be more likely to keep and use the devices.

Table 4. Reported Experience that Triggered Appointment and who Recommended the HHCP.

| Type of trigger experience | Total ( n = 420) | Current HA owners ( n = 256) | Current HA nonowners ( n = 164) |

| Not able to hear things that matter (e.g., children) | 48% | 56% | 34% |

| Not enjoying or dreading social situations | 37% | 37% | 38% |

| Avoiding situation(s) or becoming isolated | 25% | 26% | 23% |

| Relationship issue/stressor | 21% | 21% | 22% |

| Work performance issue | 15% | 15% | 14% |

| Embarrassing moment | 12% | 12% | 14% |

| Hearing difficulty worse b/c other condition | 12% | 9% | 17% |

| Accident | 5% | 3% | 9% |

| Close call | 4% | 4% | 5% |

| Some other type | 9% | 8% | 11% |

| Who recommended | Total ( n = 182) | Current HA owners ( n = 118) | Current HA nonowners ( n = 64) |

| Friend | 44% | 52% | 27% |

| Spouse or partner | 34% | 25% | 53% |

| Customer who went there | 20% | 25% | 8% |

| Child | 11% | 11% | 12% |

| Sibling | 10% | 8% | 15% |

| Coworker/boss | 9% | 7% | 12% |

| Grandchild | 4% | 5% | 3% |

| Someone else | 15% | 16% | 13% |

Abbreviations: HA, hearing aid; HHCP, hearing health care professional.

MT10 asked participants how they found the clinic and what type of facility they visited. The majority of respondents report that they visited a private practice HHCP, and as noted previously, the HHCP was most often classified as an audiologist (61%). Respondents reported that their primary purpose of visiting the facility was to get their hearing assessed (68%); however, only 38% of those who purchased aids made their appointment with the specific intent to buy aids. Owners were more likely to visit a private practice than nonowners (54 vs. 40%). Eighteen percent of owners reported they got their hearing aids from the VA or other government organization. Doctors' offices were visited by 12% of respondents, but only 5% reported they got their hearing aids there. This low rate was also reported by patients who went to an ENT (11%) and only 7% reported they purchased their hearing aids at the ENT office. Very few respondents (7%) reported going to a store that has an HHCP onsite such as club store, pharmacy, or mass merchandise store (e.g., Costco, Walgreens, and Walmart). This suggests that most people who purchase hearing aids are visiting private practices and are visiting with the intent to purchase hearing aids. As noted previously, there is a lag of 1.6 years between having a hearing test and getting hearing aids. This is interesting given that many people report that getting hearing aids is the primary objective of the visit. MT10 provided some insight into what was conducted at the appointments and the recommendations that were given.

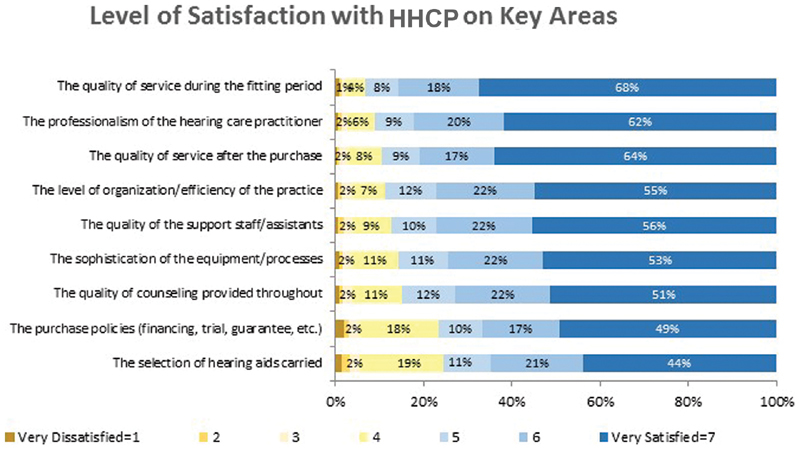

Overall, the respondents were satisfied with their HHCP with 83% of nonowners and 94% of hearing aid owners reporting general satisfaction. On the key areas of HHCP practice (see Fig. 10 ), respondents reported that they were satisfied with the professionalism and quality of service. They were least satisfied with the selection of current hearing aids and the purchase policies. This information may be useful to audiologists to know they need to be transparent and communicate about the hearing aids they provide, the reasons for a specific recommendation, and their purchase policies. It is expected that patients remember only a portion of what was told or recommended to them; written information may improve patient information retention and therefore satisfaction. 20

Figure 10.

Reported level of satisfaction with hearing health care professional (HHCP).

When asked about the actual appointment, participants reported that they had a hearing test 95% of the time and 64% reported a speech in noise test. They were, in general, satisfied with the quality of the testing, how the results were explained to them (94% reported satisfaction), and that testing addressed their specific needs (89%). Discrepancies between hearing aid owners and nonowners were reported when patients considered hearing aids. Purchasers of hearing aids were recommended hearing aids 87% of the time and nonowners were recommended hearing aids only 39% of the time. For hearing aid owners who also perceive that they have hearing loss, most (91%) were recommended that they get hearing aids; interestingly, this suggests that for 9% of people, they perceived they have hearing loss but were not recommended hearing aids. On the other hand, of the hearing aid nonowners, 39% reported were told they had a hearing loss; and of those, only 53% were recommended to get hearing aids. This suggests that nearly half of the nonadopters of hearing aids with confirmed hearing loss listened to the HHCP professional and did not get them despite being told they had hearing loss. Nonowner respondents reported that they did not get a hearing aid because they perceived their hearing loss was not bad enough (24%), a hearing aid would not help them (11%), or they should wait and be retested (13%). Overall 11% of owners were told to hold off on the purchase of hearing aids, while 46% of nonowners reported they were instructed to wait.

As stated previously, patients report that they would listen to the recommendation of their HHCP with regard to recommendations for hearing aids. Hearing aid owners felt that the HHCP sufficiently addressed their questions 94% of the time, while nonowners reported having their questions addressed only 81% of the time. Even more drastically, 90% of owners reported that the HHCP considered their needs and abilities when recommending specific hearing aids, while nonowners reported that they were satisfied only 60% of the time. Seventy-two percent of nonowners reported that the office looks like a clinic, like a doctor's office, while 57% of purchasers felt this way and 22% of the nonowners felt that the HHCP was more focused on making the sale while this was only reported by 11% of owners. It appears that audiologists are not necessarily recommending hearing aids or are downplaying the importance of amplification to where some patients do not see the need to pursue them at the time of the appointment. The owners appear to feel that the HHCP took their needs into account, made them feel welcome, and approached the solution holistically rather than as delivering technology. As was reported in the November 2016 and August 2019 editions of Seminars , having a welcoming environment to your practice does influence the patient's purchase. Additionally, setting expectations and addressing patient-specific needs appear to be highly valued by respondents. The top-three contributors to patient satisfaction with their HHCP were setting expectations, considering specific needs, and addressing specific questions. The importance of addressing patient-specific needs and expectations is further supported as the number one reason nonuser past owners reported they returned their aids was that the hearing aid did not perform as well as they had expected.

Despite all the upfront investigation that respondents reported doing when considering amplification, the majority of users of hearing aids could not report the name of the devices they received (56%). They were, however, able to describe what their hearing aid did or did not do and the features within their devices. Only 32% of hearing aid owners reported that their HHCP completed real-ear probe microphone measurements. This is consistent with data which states that one-third of audiologists complete these measures despite the evidence-base for target-verified hearing aid fittings which is accomplished through real-ear probe microphone measurement. 21 Further use of real-ear probe microphone measures improves patient satisfaction with hearing aids. 22 Over 90% of hearing aid owners reported that their HHCP adjusted the hearing aid to make it bearable/manageable, while only 77% of nonowners who tried hearing aids reported the same. Verification (probe microphone) and validation (adjustments based on patient report) are the best way to ensure patient success with hearing aids. 23 Ninety-one percent of hearing aid owners reported the HHCP adjusted the hearing aid to meet their needs and 77% reported the HHCP used effective techniques to determine their benefit from hearing aids. Despite data disputing the real-world applicability of aided loudness judgements and functional booth testing, 73% of owners reported their HHCP asked them to judge loudness of different sounds with and without their hearing aids and 66% reported they were asked to repeat words with and without hearing aids. 24 25 Thirty-seven percent reported they were given tools and techniques to retrain their brain. It is unknown as to what types of information and techniques they were given. It is reported that although patients report being given the training tools, few actually complete the training. 26 In general, those people who purchased and kept their hearing aids are satisfied with the procedures and protocols followed by their HHCP more so than nonpurchasers. It is unknown as to how the nonowners judged their HHCP protocols and that they likely did not experience as much of the hearing aid protocol as the hearing aid owners, but it is possible that their lack of confidence in the HHCP could have influenced their lack of hearing aid uptake. HHCPs set up their patients' success when they discussed hearing aid expectations. However, it appears that many HHCP continue to use poorly supported testing such as aided functional performance rather than evidence-based verification techniques that quantify audibility across frequency and input levels.

In line with anecdotal evidence, about half of the MT10 respondents reported that their HHCP offered more than one brand of hearing aid. Interestingly, 55% of hearing aid owners reported the variety of brand options, while only 40% of nonowners answered that they observed the variety. This suggests that having a variety of options and not being tied to one manufacturer could increase the number of patients who adopt hearing aids. About half (51%) of owners reported that they were given a trial period with hearing aids without any financial obligation of purchase. Most commonly patients were given a 30-day trial with the hearing aids; however, some reported much longer trial periods with a small percentage (9%) reporting a trial prior of more than 90 days. While half of purchasers reported getting a no obligation trial period, having a trial period did not correlate with hearing aid purchase. New hearing aid owners are more satisfied with their hearing aids than people who have owned their aids for more than 5 years ago. The majority of people reported that they kept their hearing aids and 75% reported that they wear them daily. If they did return the hearing aids, it was because they did not perform as expected (22%), they decided to get a PSAP or device on their own (21%), or they never really intended to get a device (18%). Owners of hearing aids do like going to an HHCP that they feel is not associated with a specific manufacturer. Owners of new hearing aids are more satisfied with their new hearing aids than previous hearing aids; this could be due to the halo effect discussed in literature about purchasing of any new piece of equipment. People tend to be more satisfied when they have committed to the purchase and are happy with their purchase. In line with data presented by previous research, no obligation trial does not lead to an increase in hearing aid uptake. 27

Overall, hearing aid purchasers are satisfied with their HHCP. Patients most often visit an HHCP at a private practice and they classify the HHCP as an audiologist. There is a significant increase in hearing aid purchase when the audiologist presents information about hearing aids in a manner that directly addresses the patient concerns. Patients are more likely to purchase when they see the HHCP as welcoming and enthusiastic about their recommendations. They tend to trust the HHCP more when they are not tied to one manufacturer. It does appear that many HHCPs are still not completing hearing aid fittings using guideline-based, such as target-based, verification. 28 29 The majority of patients are satisfied with their HHCP protocols, possibly because they do not know that there are other accepted techniques. After the fitting, the majority of patients choose to keep their hearing aids.

MT10 data can be used to determine what factors drive patients to see hearing health care providers and what factors may convince them to adopt a solution to manage their hearing loss. This article presented suggestions that the audiologist may consider when marketing to patients or when gathering information. Self-reported information does not always accurately reflect the details of actual experiences but can still be noteworthy as it reflects patients' memory and perceptions. The information presented could be used by the audiologist to better tailor their scheduling and their presentation of hearing aid options to better meet the needs of their patients and increase hearing aid adoption.

References

- 1.Abrams H B, Kihm J. An introduction to MarkeTrak IX: a new baseline for the hearing aid market. Hearing Rev. 2015;22(06):16. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kochkin S. MarkeTrak VIII: 25-year trends in the hearing health market. Hearing Rev. 2009;16(11):12–31. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kochkin S. MarkeTrak V: “Why my hearing aids are in the drawer”: the consumers' perspective. Hear J. 2000;53(02):34–36. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mueller H, Ricketts T, Bentler R. San Diego, CA: Plural; 2014. Modern Hearing Aids: Pre-Fitting Testing and Selection Considerations. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Palmer C V, Solodar H S, Hurley W R, Byrne D C, Williams K O. Self-perception of hearing ability as a strong predictor of hearing aid purchase. J Am Acad Audiol. 2009;20(06):341–347. doi: 10.3766/jaaa.20.6.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bainbridge K E, Ramachandran V. Hearing aid use among older U.S. adults; the national health and nutrition examination survey, 2005-2006 and 2009-2010. Ear Hear. 2014;35(03):289–294. doi: 10.1097/01.aud.0000441036.40169.29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hougaard S, Ruf S. EuroTrak I: a consumer survey about hearing aids in Germany, France, and the UK. Hearing Rev. 2011;18(02):12–28. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Valente M, Amlani A M. Cost as a barrier for hearing aid adoption. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2017;143(07):647–648. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2017.0245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boatman D F, Miglioretti D L, Eberwein C, Alidoost M, Reich S G. How accurate are bedside hearing tests? Neurology. 2007;68(16):1311–1314. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000259524.08148.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Painter J E, Borba C P, Hynes M, Mays D, Glanz K. The use of theory in health behavior research from 2000 to 2005: a systematic review. Ann Behav Med. 2008;35(03):358–362. doi: 10.1007/s12160-008-9042-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Popp P, Hackett G.Survey of primary care physicians: hearing loss identification and counseling 2002. Audiology Online. Available at:https://www.audiologyonline.com/articles/survey-primary-care-physicians-hearing-1179. Accessed December 31, 2019

- 12.Snyder C F, Frick K D, Peairs K S et al. Comparing care for breast cancer survivors to non-cancer controls: a five-year longitudinal study. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(04):469–474. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-0903-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lin F R, Yaffe K, Xia J et al. Hearing loss and cognitive decline in older adults. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(04):293–299. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.1868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ford A H, Hankey G J, Yeap B B, Golledge J, Flicker L, Almeida O P. Hearing loss and the risk of dementia in later life. Maturitas. 2018;112:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2018.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jorgensen L E, Palmer C V, Pratt S, Erickson K I, Moncrieff D. The effect of decreased audibility on MMSE performance: a measure commonly used for diagnosing dementia. J Am Acad Audiol. 2016;27(04):311–323. doi: 10.3766/jaaa.15006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Capella-McDonnall M E. The effects of single and dual sensory loss on symptoms of depression in the elderly. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2005;20(09):855–861. doi: 10.1002/gps.1368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cosh S, von Hanno T, Helmer C, Bertelsen G, Delcourt C, Schirmer H; SENSE-Cog Group.The association amongst visual, hearing, and dual sensory loss with depression and anxiety over 6 years: The Tromsø Study Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 20183304598–605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mitoku K, Masaki N, Ogata Y, Okamoto K. Vision and hearing impairments, cognitive impairment and mortality among long-term care recipients: a population-based cohort study. BMC Geriatr. 2016;16(01):112. doi: 10.1186/s12877-016-0286-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schneider J M, Gopinath B, McMahon C M, Leeder S R, Mitchell P, Wang J J. Dual sensory impairment in older age. J Aging Health. 2011;23(08):1309–1324. doi: 10.1177/0898264311408418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kessels R P. Patients' memory for medical information. J R Soc Med. 2003;96(05):219–222. doi: 10.1258/jrsm.96.5.219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mueller H G, Picou E M. Survey examines popularity of real-ear probe-microphone measures. Hear J. 2010;63(05):27–28. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mueller H G. Probe-mic measures: hearing aid fitting's most neglected element. Hear J. 2005;58:21–22. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jorgensen L E. Verification and validation of hearing aids: opportunity not an obstacle. J Otol. 2016;11(02):57–62. doi: 10.1016/j.joto.2016.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Humes L E, Halling D, Coughlin M. Reliability and stability of various hearing-aid outcome measures in a group of elderly hearing-aid wearers. J Speech Hear Res. 1996;39(05):923–935. doi: 10.1044/jshr.3905.923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wu Y H, Bentler R A. Do older adults have social lifestyles that place fewer demands on hearing? J Am Acad Audiol. 2012;23(09):697–711. doi: 10.3766/jaaa.23.9.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sweetow R W, Sabes J H. Auditory training and challenges associated with participation and compliance. J Am Acad Audiol. 2010;21(09):586–593. doi: 10.3766/jaaa.21.9.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kasewurm G A. Gaining greater adherence from patients for amplification. Semin Hear. 2019;40(03):245–252. doi: 10.1055/s-0039-1693491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.American Speech Language and Hearing Association.Guidelines for hearing aid fitting for adults 1998. Available at:https://www.asha.org/policy/GL1998-00012/. Accessed December 31, 2019

- 29.Valente M. Audiological management of adult hearing impairment. Audiol Today. 2006;18(05):32–36. [Google Scholar]