Abstract

The first officially recognized otolaryngology resident at Mayo Clinic started training in 1908. In the following years, the residency program evolved through emerging national standards and regulations for medical education, declining and resurgent interest in the specialty, and radical changes in otolaryngology as a practice. This article details the growth of the Mayo Clinic otolaryngology residency program, often in the words of the pioneering physicians involved in the process, from “filler-ins” for the staff to today’s nationally recognized program.

Abbreviations and Acronyms: ACS, American College of Surgeons; ENT, otorhinolaryngology; RRC, Residency Review Committee

From the vantage point of the 21st century, it is very easy to overlook the fact that when Mayo Clinic practice began in 1864, Minnesota was still part of the Old West (Figure 1). In fact, when Dr William Worrall Mayo brought his family to Rochester in 1863, Jesse James had not yet robbed the Northfield Bank, Billy the Kid was still shooting his way through the West, and Calamity Jane was only 11 years old. When Saint Marys Hospital opened its doors in 1889, the Coca-Cola Company was incorporated, Vincent Van Gogh painted The Starry Night, the first issue of the Wall Street Journal was published, and Charlie Chaplin and Adolph Hitler were born just days apart from each other. In Rochester, streets were unpaved, the horse was still the main mode of transportation, and the city’s first municipally owned power plant would not generate electricity until 1894.1 On the medical front, cocaine, heroin, morphine, and laudanum were everyday ingredients in medical “remedies,” peddled for toothaches, coughs, and fussing, teething babies.2

Figure 1.

Downtown Rochester, Minnesota, circa 1868.

Reproduced with permission of the W. Bruce Fye Center for the History of Medicine, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota.

Similarly, medical education was waiting for the next advancement. When the first officially recognized otolaryngology resident at Mayo Clinic, Dr Margaret I. Smith (Figure 2), started training in 1908, US medical schools were mainly private, for-profit, and not affiliated with a university.3,4 On average nationwide, the ratio of patients per doctor was 568:1,4 what Abraham Flexner would describe in his 1910 report on the state of medical education in the United States as an “over-production of uneducated and ill trained medical practitioners.”4 There were few requirements of medical schools, and likewise few requirements to qualify as a medical doctor, much less a medical student. There was no specialized medical training beyond completing medical school and working side-by-side with a physician, often performing little more than “scut work” to gain experience and start a practice. Perhaps the most valuable post–medical school training up to World War I consisted of traveling to Europe to observe in operating theaters.5 This certainly was a large part of Drs William J. (Will) and Charles H. (Charlie) Mayo’s education after they completed medical school and throughout their lives.

Figure 2.

Margaret I. Smith, MD, is the first officially recognized otology and rhinology trainee at Mayo Clinic, starting her training in 1908 and leaving Mayo Clinic in 1911. She went on to practice medicine in Minneapolis, Minnesota, and become the director of clinical/pathology laboratories at Northwestern Hospital there.6

In some ways, the Mayo brothers were actually the first surgical residents at Mayo Clinic, working alongside their father, William W. Mayo, MD (Figure 3). While they were growing up, apprenticeships were the norm for training physicians, but they recognized early that physicians and surgeons on the whole were not fully sharing their knowledge and that trainees were mired in drudge work. After visiting a medical school in the East, Dr Will noted, “[The residents] seemed to spend their days in subservient yessir-ing, in being flunkie for the permanent staff.”7 Drs Will and Charlie learned from their father’s teaching method—which included nonmedical lessons, such as sending his young inexperienced sons to wrangle an ill-tempered cow he had bought from a patient8—that hands-on experience and open communication were the best methods for learning (Figure 4). Dr Will, in an address to the Mayo Alumni Association in 1919, reflected on the reason for the growth of Mayo Clinic and its educational shield: “the desire to advance in medical education by research, by diligent observation, and by the application of knowledge gained from others; and most important of the desire to pass on to others the scientific candle this spirit has lighted.”9

Figure 3.

Dr William W. Mayo, circa 1904.

Reproduced with permission of the W. Bruce Fye Center for the History of Medicine, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota.

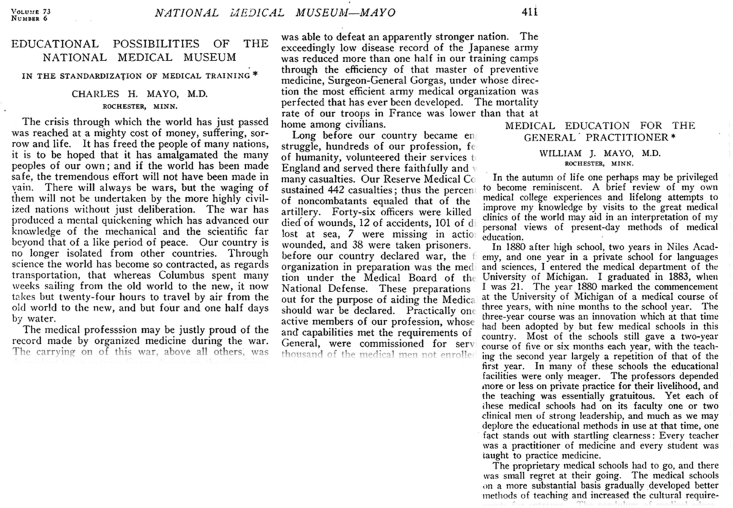

Figure 4.

Educational articles published by Drs Will and Charlie Mayo in 1927 and 1919, respectively.10,11

The Harold I. Lillie Era

Preaccreditation

Mayo Clinic originated before the establishment of the National Confederation of State Medical Examining and Licensing boards in 1890, and medical school graduates traveled to Mayo Clinic for training long before standards or regulations for graduate medical training were published.

The nationwide need for standards and regulations was made glaringly evident in 1910, when Abraham Flexner and the Carnegie Foundation released Medical Education in the United States and Canada: A Report to the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching, a pivotal report that analyzed the state of medical education and ultimately changed the face of medical education in the United States. The Flexner report only peripherally addressed postgraduate education and therefore did not affect Mayo Clinic directly, because at the time Mayo Clinic did not have a medical school as such but rather took on medical graduates for further training. It would, however, have an eventual impact on the quality and variety of graduates who came to Mayo to train,12,13 particularly regarding the unintended consequences of the Flexner report on female and black medical students who were heavily impacted by medical school closures, setting medical training opportunities for such students back decades.12, 13, 14 Relevant to the state of Minnesota, the Flexner report congratulated the University of Minnesota for “absorbing all other medical schools in the state.”4

In 1915, the Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research was established, which included an integral partnership with the University of Minnesota. The University of Minnesota conferred graduate medical degrees for Mayo Clinic until 1983.5,15 In total, by 1922 more than 1000 prospective candidates sought positions for graduate medical training at Mayo Clinic.16 Of course, since Dr Charlie himself was keenly interested in head and neck surgery, otorhinolaryngology (ENT) fellows (Mayo Clinic training programs used the term fellows until the 1970s for both residents and fellows, reminiscent of European terminology5) had been training at Mayo Clinic long before then, with the training program established in 1908 with fellow Margaret I. Smith, MD. By 1923, as a specialty ENT-ophthalmology, or “eye-ears-nose-throat” was nationwide the most popular specialty to practice, followed by general surgery and distantly by internal medicine. Unfortunately, this was also the era of ENT specialty training that otolaryngologist George E. Shambaugh described as producing “carpenters in oto-laryngology,”7 certainly not a flattering description of the state of otolaryngology education in the United States during this boom of popularity.

Throughout the 1920s, the primary teaching method in otolaryngology continued to be the apprenticeship model—the traditional teaching method since the beginning of medical education in the United States. However, in a 1924 report to the Mayo Clinic Board of Governors, department chair Dr Harold I. Lillie refined the definition of the apprenticeship model (Figure 5). Instead of the traditional one-on-one relationship between master and apprentice in which learning relied almost exclusively on direct observation and was limited by the abilities and teaching inclinations of the master,17 apprenticeship in otolaryngology at Mayo Clinic meant “being made responsible for a patient and his care under the direction of the consultant’s advice,”18 thus establishing the backbone of ENT training to the present time and giving a nod to the hands-on learning directly advocated by the Mayo brothers.19

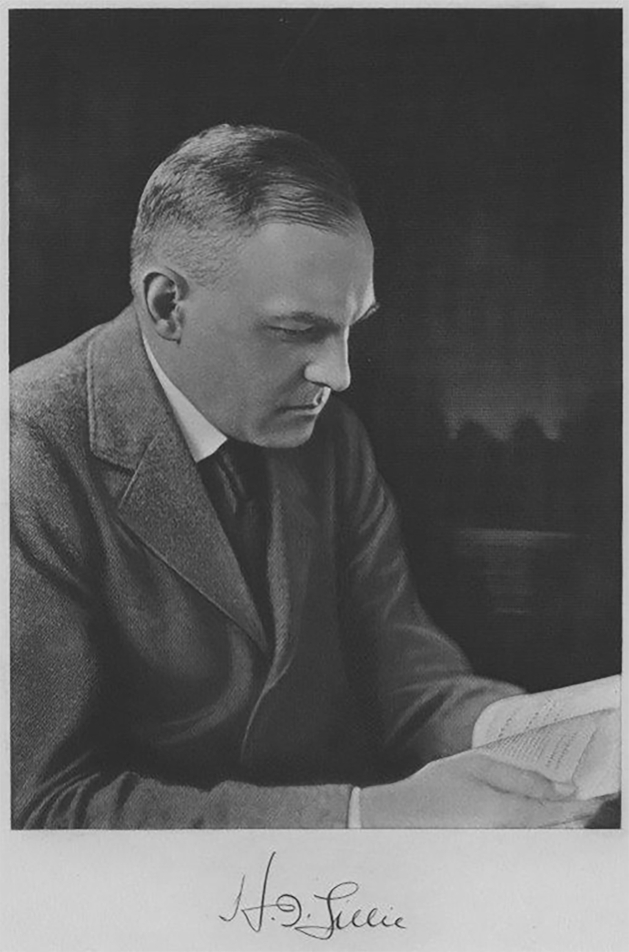

Figure 5.

Harold I. Lillie, MD, served as the department chair from 1919 to 1953, not only overseeing the formation of the early Otolaryngology Section but also laying the foundation of the otolaryngology residency program.

Reproduced with permission of the W. Bruce Fye Center for the History of Medicine, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota.

At the time, the arrangement between staff and their fellows was symbiotic—the fellows benefited from graduated educational experiences and faculty mentorship: “The men are gradually allowed to assume responsibilities under surveillance commensurate with their ability to do so.”18 However, equally so, the faculty benefited from the fellows’ execution of menial service tasks so that they might have more time for “thought, study, and preparation of articles for publication.”18 Thus, although there was no question about the dedication of faculty to the education of their trainees, the driving force behind the number of fellows accepted each year closely paralleled clinical volume and the need for assistance with routine work.

It was not until 1938 that a curriculum beyond case work was mentioned in the annual departmental report to the Board of Governors: “Individual case demonstrations [have] proven to be the most satisfactory of teaching the fellowship men. Courses of reading are suggested. Seminars will be inaugurated this year.”18 The inauguration of seminars in 1938 may have been a reaction to outside pressure throughout the 1920s and 1930s for accountability and standardization. In 1924, the National Board of Examiners in Otolaryngology was established in part to “produce a safe and sane man to practice in the specialty.”7 Graduates now had to demonstrate competence before they were allowed to practice independently. On the program side, in 1928, the American Medical Association published “Essentials of Approved Residencies and Fellowships”20—the first published standard for residency and fellowship programs. Later, in 1939, the American College of Surgeons (ACS) published “Graduate Training for General Surgery and the Surgical Specialties,”21 spelling out what was or should be required of both hospitals and the residents to make a successful residency.

Interestingly, the focus of the ACS requirements was quite different from today’s accreditation requirements. In particular, they did not address what the program was supposed to provide for the trainee. Rather, even when discussing what the program should consist of, the ACS addressed the trainee directly and pointedly: it is the trainee’s responsibility to provide everything they need to succeed, including keeping a record of their progress and periodically submitting “for the consideration of their preceptors a prescribed summary of their work.”21 In contrast, once accreditation became a requirement, the onus was put fully on the program to not only provide requisite resources but to also ensure that the residents made full use of them.

The road to accreditation was not newly paved in the 1920s and 1930s. Solid steps had been taken as early as 1896 when what is now named the American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery was established, which led to the first specialty boards—ophthalmology in 1916 and otolaryngology in 1924.22 Furthermore, individual states enacted legislation requiring licensure of physicians beginning in the late 1800s. In 1887, Minnesota was the first to enact a law requiring a minimum of medical education prior to practicing.23 With licensure came examinations and the boards, and accreditation would follow.

The Road to Accreditation

The Mayo Clinic otolaryngology residency program was first accredited in 1952 by what would eventually become the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. To reach accreditation, however, the program had to traverse declining interest, turf battles, radical changes in otolaryngology as a practice, and a devastating world war.

Throughout the early 1940s, the annual reports to the Mayo Clinic Board of Governors were filled with roll calls of able-bodied otolaryngologists and fellows who were already commissioned by the military and contingency plans if they were all called to duty. The worst-case scenario saw one surgeon, Dr H. I. Lillie, who would do surgery all day and one medical otolaryngologist, Dr B. E. Hempstead, who would consult in the office all day, noting, “It is certain, however, that the service to the patients in general will suffer greatly because it will be physically impossible for two consultants adequately to perform the duties of six consultants.”24 The report continued, “It may be difficult to obtain physicians on the fellowship services unless certain ones who [cannot] meet the physical requirements of the military services apply.” Thus, by 1943, it was noted that all fellows except for one were exempt from military service “due to physical defects,” and the one who would meet the military’s physical requirements was not a naturalized citizen.

During this stressful time, Dr H. I. Lillie noted, “For some unknown reason, perhaps the general nervous tension, there has crept into the service a spirit of rivalry never previously encountered.” He continued, “Under the present stress of the national emergency I do not propose to make any radical changes in the personnel, but if the relationship does not change, a change may be urged.” In the same report, he lamented that the fellowship left “much to be desired and there seems no way immediately in the future to correct the situation.” By the end of the war, however, a “notable improvement in the esprit de corps” came with a salary adjustment and a return to regular vacation time.24 Not only was the department able to stay staffed throughout the war, but patient and surgical counts did not plummet as originally projected. The training program continued throughout the war even when Drs H. L. Williams, K. M. Simonton, H. A. Brown, and O. E. Hallberg were called to service in 1940.

World War II was not the only strain on attracting “suitable men…applying for training in ear, nose, and throat.” This time, the deficiency was due to the changing nature of the otolaryngology practice, as well as the changing landscape of medical education on the whole. For one thing, there was more competition for fellows “because of the influence of American Examination Board [sic]” and more “available opportunities for training more men in the field.”24 Furthermore, because other otolaryngology programs across the United States were aggressively expanding specialty jurisdiction through turf battles with rivaling specialties, the most “suitable men” were seeking their education at other programs with greater training opportunities (H. B. Neel III, MD, written communication, undated).

It was during this time that a turf contest between otolaryngology and neurosurgery developed in the years prior to the United States joining World War II, climaxing in 1939-1940 when Dr H. I. Lillie declared that “the attitude of the chief of neural surgery is unreasonable.”24 A year later, the controversy had not been resolved:

No disposition has been made of the controversy between the ear, nose and throat staff and the neural surgical staff. The matter has been brought to the attention of [the Board of Governors] on previous occasions. The relationship is not too cordial and there is always evident some restraint which may be detrimental to the patient’s welfare. If credit could be given where credit might belong, it might make possible a better service to the patient. Unjust criticism of technical procedures in which there is no unanimity of opinion among the profession is not conducive to cordiality.24

Thereafter, when discussing “Relationship to Other Departments, Hospitals, and Institutions” (a regular section in the report to the Board of Governors), Dr Lillie repeated the same paragraph each year word-for-word: “There has been no interruption in the hospital consultation services. Every effort is made to co-operate with other services. We are in turn deeply appreciative of the fine co-operation that has been extended to this service. It is my feeling that all extramural relationships are cordial.”24 No mention of an actual solution was ever made; however, it was clear in subsequent reports that otolaryngology and neurosurgery reestablished a clear and mutually beneficial clinical partnership.

The otolaryngology section at Mayo Clinic was slow in responding to the need to grow subspecialties and consolidate regardless of turf wars. While today otolaryngology-head and neck surgery as a specialty is generally divided into 7 subspecialties—otology/neurotology, rhinology, laryngology, head and neck surgery, pediatric otolaryngology, facial plastic reconstruction, and sleep surgery—in the first half of the 20th century at Mayo Clinic only a few physicians aligned themselves with a subspecialty now linked to otolaryngology, and they were in different sections apart from otolaryngology. The 1941 Board of Governors report appears to be the first to mention a “gradual splitting off from the service of certain borderline types of conditions.” Certainly, trends foreshadowing this split, not just at Mayo Clinic but within otolaryngology as a whole, had been in sight for several years, starting with the advent of sulfonamides and penicillin, which by curing infections without surgery, reduced the surgical volume for otolaryngology residents and consultants alike.19 Throughout the 1940s, concerns were raised that fellows had insufficient surgical experience in cases such as mastoidectomies because of new medical rather than surgical treatment. Indeed, by 1949, the consensus was that “outstanding men in the field will need to have very broad medical background training and the borderline surgical fields will be included in the scope of the specialty.”24

At this point in time, programs at other institutions, such as the universities of Iowa, Michigan, Illinois, and Pennsylvania, were already transitioning, broadening the scope of their training. At Mayo Clinic, Dr Lillie was fighting the tendency to confine specialty surgical fields “to structures within the mucocutaneous margin of the involved anatomic structures,” declaring it “too arbitrary and actually a very short-sighted and silly position to take.” Specialists, he argued, required the same medical education and training as general surgeons. Thus, the focus after World War II was “centered on arranging the teaching of fellowship men on a curriculum which will conform to that suggested by the American Board of Otolaryngology,” and research work for the consultants was suspended while they worked at reorganizing the program. Such a narrow definition of the practice, he argued, would result in a decline in the number of future physicians going into otolaryngology and thus future fellows, a possibility “looked upon with increasing apprehension by the older staff members.”24

Certainly, in Dr Lillie’s last report to the Board of Governors in 1950 before Dr H. L. Williams became the department chairman, he wondered why so few graduates were seeking training in otolaryngology. The demand, he noted, was there. Salaries were $9000 to $15,000, and the “auspices are all that could be desired.” Still, at the time there was only one fellow on board, and he would be completing his training the following October. Dr Lillie admitted that “the glamor of the surgery has lessened, as it has in all training centers,” but he noted the way the specialty had developed to interrelate general medical problems with otolaryngological disorders made training in otolaryngology “well-rounded…‘doctors’ first and ‘specialists’ secondarily.”24 No longer regarding the fellows as “filler-ins,”18 a second pair of hands for the consultant, the focus was now on their training, noting that required case presentations, examinations by the American Board, library work, and editing their “literary efforts” were all beneficial for their education.24

Throughout the 1940s, suggested reading schedules and didactic seminars—sometimes with extramural speakers and including instruction in anatomy and pathology—supplemented traditional clinical and surgical hands-on training, and by 1952, the program was accredited. Having accomplished this noteworthy feat, Dr H. I. Lillie retired from Mayo Clinic in 1953 after serving 34 years as department chair and died at home in 1957.25

Glimmers of the Future

Accreditation

Another era of change was upon the otolaryngology residency program after Dr H. I. Lillie stepped down. The 1950s and 1960s swirled with challenges and threats, as well as possibility and promise. In the 1950s, the ENT department was solidly split into 2—a consequence of events that can be traced to the beginnings of Mayo Clinic. Approximately a decade after the doors of Saint Marys Hospital officially opened, a number of physicians were hired to manage conditions that overlapped with the modern otolaryngology practice: Drs J. Matthews and Gordon B. New, laryngology and rhinology; Dr Carl Fisher, ophthalmology and otology; Dr Henry S. Plummer, upper aerodigestive endoscopy and thyroid disease; and Drs Edward Starr Judd and Walter E. Sistrunk, head and neck tumors.19 Although this increase in staff would seem to be the start of a cohesive, modern ENT department, in fact these surgeons were instead divided between surgical specialties. At the time, there was really no way to anticipate how the ENT specialty would come together, encompassing otology, rhinology, laryngology, head and neck surgery, and more. The only permanent separation in this group would eventually be ophthalmology.

In 1917, ENT was further transformed after the affiliation between Mayo Clinic and the University of Minnesota was made permanent and with the formal establishment of a separate Section on Laryngology, Oral and Plastic Surgery headed by Dr G. B. New, while Dr Lillie was appointed otolaryngology section head. At this point, it was stipulated that two-thirds of laryngology cases would go to the new laryngology section with the remainder going to otolaryngology and rhinology. However, the other third often did not carry over.19 Indeed, in 1937, Dr Lillie reinforced the division: “This understanding has never been insisted upon because as the work developed it was found that the paranasal sinus and the ear work so greatly increased that it was impossible to consider doing any operative laryngology. Operative laryngology is done so well in the other section this understanding has been overlooked.”18

Unfortunately, this division would prove severely detrimental to the residency training program. In Dr Williams’ first report to the Board of Governors in 1952, he noted a “waning spirit of co-operation between the two sections as far as the training program for fellowship men in our specialty was concerned.”24 The Section on Laryngology, Oral and Plastic Surgery had developed their own fellowship program in plastic surgery, and the time the otolaryngology residents spent in that section was cut from 1 year to 6 months. Opportunities for the otolaryngology residents for observation and training during that 6 months were limited, and, Dr Williams noted, “it seemed to me at times that the Section on Laryngology, Oral and Plastic Surgery was attempting to deny their share of the responsibility for the fellowship in otology, rhinology and laryngology.” At the same time in other institutions, the specialty was expanding to include areas that were divided at Mayo Clinic, such as skull base surgery, head and neck surgery, and facial trauma. Otolaryngology at Mayo Clinic was, in Dr Williams’ words, “deteriorating not only relatively to [other institutes’ training programs] but absolutely.”18

After negotiations with the Section on Laryngology, Oral and Plastic Surgery, including a vetoed suggestion that the 2 fellowships be combined under the Section on Otolaryngology and Rhinology, the situation remained virtually status quo except that fellows were able to spend a full year in laryngology, and assurances were given that the otolaryngology fellows would have the same learning opportunities as the fellows in plastic surgery.

Despite the division, the otolaryngology residency program made do with the resources available. At this time, training encompassed a year in the Section on Laryngology, Oral and Plastic Surgery, 6 months of training in pathology, regular Tuesday evening seminars consisting of case presentations by the residents and lectures by staff, dissections in the Anatomy Laboratory including cadaver surgery and practice with surgical flaps, suturing, and knot tying, and training in medical otolaryngology and allergy treatments. While the Section on Laryngology, Oral and Plastic Surgery focused on and advanced treatments for sinus, pharynx, and larynx malignancies and other surgeries, the Section on Otolaryngology and Rhinology was tackling deafness and vestibular disorders, a patient population that had few, if any, options prior to this era and was regularly turned away from Mayo Clinic. The rise of this field kept a portion of the specialty in the operating room with canal fenestrations, mastoidectomies, and labyrinthectomies. At the same time, relationships with otology and neurosurgery had improved enough that they were able to collaborate on certain conditions, such as Bell palsy and hemifacial spasm.24

Unfortunately, this richness in education was precariously dependent on interdepartmental cooperation, especially with what could be viewed as competing fellowships, so while Dr Williams declared in 1953, “The future of otology, rhinology, and laryngology…never seemed brighter,” he followed quickly with:

It is very important that the associations between the Sections on Otolaryngology and Rhinology and of Plastic Surgery and Laryngology be maintained at the present cordial level or even better strengthened. With the opportunities for fellowship training that are offered elsewhere, we will not be able to obtain the most desirable type of man for our fellowship unless we are able to offer them training in the surgical care of malignancies of the head and neck, otolaryngologic plastic surgery, repair of injuries in the region of the head and neck and bronchoscopy commensurate with that received elsewhere.24

As soon as the following year, the Council on Medical Education and Hospitals of the American Medical Association made “inquiries in regard to the actual amount of surgery done by our fellows.”24 Thus began a threat to program accreditation.

In 1954, Dr Williams frankly noted that “all of our fellows are not equally competent,” that cadaver studies could be a partial solution, but it was “impossible to obtain the necessary anatomic material.”24 Furthermore, he cited the decline in resident surgical experience as stemming from a “continued attrition in the numbers of surgical patients” with the introduction of antibiotics. Furthermore, he noted that surgical numbers were divided between “too many individuals so that it is difficult for one man to develop outstanding skill.” This then affected referrals (and eventually surgical experience for the fellows), which had also declined, because none of their individual surgeons were “well-known” enough: “It is possible that the levelling process in our section has been carried too far.” He went on to cite a lack of control in distributing surgical cases and an “unusual amount of unused time” or overstaffing in the department. Again, he suggested the consolidation of the 2 sections, to which one of the reviewers from the Board of Governors responded in the margin, “This seems so logical, I wonder it has not been accomplished long ago.”24

The next few years are a testament to increasing pressure from the Board of Otolaryngology and competition from other medical institutions that were expanding their training programs to 4 and 5 years. Dr Williams remarked in his 1956 report, “I fear that some time in the near future the Board of Otolaryngology will pronounce our training program inadequate.” He defended the training program, although revealing his own innate prejudices at the same time: “[Other institutions] are training head and neck surgeons rather than otorhinolaryngologists. These men must sit around their offices until someone refers them a malignancy and would prove inadequate in general practice of the specialty.”24 The noose tightened the following year when the American Board of Otolaryngology required that candidates for board certification would need to be prepared in otology, rhinology, laryngology, bronchoscopy, and surgery for nose, sinus, and pharyngeal malignancies. The following year, a fourth year in general surgery would be required.24

When Dr K. M. Simonton took over the chairmanship from Dr Williams in 1958, he acknowledged a core deficiency in the training program to the Board of Governors: “Our surgical training is considered by the fellows to be one of the weak points of the program. This is the result of the nature of our practice.” However, Dr Simonton pointed out that cadaver dissection and a program for teaching microsurgery of the ear were instituted just a few years before to help bolster surgical training and asserted that the “surgical competence of the men who have finished the training course in the past” was an indication of the success of the program.24

Perhaps a little paradoxically, it was during this rather austere time in the Mayo ENT residency program that a slow but significant practice change was happening, which would affect the residency for years to come. Otorhinolaryngology as a specialty, it seemed, was deemed desirable because of the varied surgical experience, and physicians who had been trained in ENT were interested in practicing the full breadth of the evolving specialty. The division in the department meant the ENT side was limited with few, if any, laryngology, head and neck, facial trauma, and other procedures. As late as 1958, Dr Williams was bemoaning the limitations put on the practices of ENT residents at Mayo, thus limiting recruitment. However, just a year later, Dr Simonton noted a “gradual division of surgical work” taking place in the department. Otorhinolaryngology surgeons were subspecializing into rhinologists, laryngologists, and otologists.24 This trend had been gathering momentum for many years—for example with Dr J. Lillie specializing in laryngologic surgery—but the value of subspecialization was just being recognized. With this shift, Mayo ENT surgeons were able to carve out a name for themselves within their subspecialty, thereby increasing referrals and recognition of the ENT department at Mayo Clinic. In turn, the residency program was able to take advantage of this depth of knowledge and change its system of rotations. Starting in 1960, fellows would work with one staff member per quarter. In this way, the fellow would gain experience working among the staff members throughout the department, an innovation on the preceptorship style of education that removed the risk of limited experience for the fellow who worked with a single mentor throughout training.24 This system of rotations has carried through to the present day, with residents training in each of the subspecialities by working one-on-one with a physician in that subspeciality for 3 months at a time throughout their residency and getting multiple perspectives on a wide array of cases.

Unfortunately, back in the 1960s, this innovation was not enough. After a review of the training program in 1961 by the Residency Review Committee (RRC), concern was officially raised about the amount of hands-on surgical training offered in the program. With that concern raised, the American Board of Otolaryngology “insisted that we broaden the scope of our training.”24 By 1962, the program was on probation.

Probation

Although formal accreditation was initiated in 1952, the Mayo Foundation appeared on the list of “Approved Residencies and Fellowships” for some time before that. In the 1942-1943 edition, “Mayo Foundation Fellowships—The Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research, Rochester, Minn., under the direction of D. C. Balfour” offered approved, 3-year fellowships in coordination with the University of Minnesota. These fellowships were in anesthesia, dermatology and syphilology, internal medicine, neurology and psychiatry, neurosurgery, obstetrics and gynecology, ophthalmology, orthopedic surgery, otolaryngology, pathology, pediatrics, physical medicine, plastic surgery, proctology, radiology, surgery, and urology with a stipend of $900 per year.26 The listings of approved residencies at Mayo Clinic changed little over time, even when the residency program went on probation for 5 years.

After the warning in 1961, it was official: “Our program has been placed on probation by the Residency Review Committee. The reason for the probation is that we have not been providing surgical experience that is comparable to other institutions.” Dr Simonton cited 2 distinct reasons for the probation in a letter to the Board of Governors. First, unlike today when institutions like Mayo Clinic are clearly teaching institutes and patients understand up front that they will be working with fellows and residents under a consultant’s supervision, there was a hesitancy to turn patients over to residents for surgery because Mayo Clinic was a private practice. Interestingly, this was counter to previous concerns throughout the 1920s that patients would consider the fellows to be their doctors, which at the time was considered detrimental to Mayo Clinic. Second, as always, the division of labor between the ENT section and the general surgery section (neck dissection and salivary gland surgery), the Department of Plastic Surgery (head and neck tumor surgery), the medical chest section (peroral endoscopy), and the allergy section clearly reduced hands-on experience in the operating room.

Measures were put in place to mitigate the dissatisfaction of the RRC. In 1964, the fourth-year fellows were assigned to outside institutions as far away as Shreveport, Louisiana, for a 6-month rotation to get training and experience in neck dissection and head and neck oncology. Furthermore, “certain selected fellows with above-average ability” would get “some improvement” in neck dissection with Dr O. H. Beahrs in general surgery.24 However, even when the fellows were receiving the required training in all areas of ENT by placement with other institutes and other departments within Mayo Clinic, the probationary status remained intact because “a relatively small proportion of the training required for certification in Otolaryngology” was being managed by the otolaryngology section itself. Dr Simonton noted that reorganizing the otolaryngology section would require “some change in the basic philosophy of the Clinic which has been to have one area of work done entirely by one group.” He also revealed that a plan from the previous year to reassure the RRC had failed. Placing Dr Devine’s and Dr Lillie’s names on otolaryngology departmental letterhead “was recognized for what it is…‘lip service.’ ”24

By 1967, changes were under way. Leadership of the department was about to change from Dr Simonton to Dr Thane Cody. Drs K. Devine and J. Lillie were moving into the Department of Otorhinolaryngology, leaving the Department of Plastic Surgery. In addition, Dr Beahrs agreed to allow the department to approach “a promising general surgical resident” for a combined training program in general surgery and otolaryngology, which would lead to a position in otolaryngology with the express purpose of performing radical neck dissections and salivary gland procedures.24 The following year, Dr L. DeSanto joined ENT. In addition, a Chief Residency Program was well under way, opening up patients’ willingness to be treated by residents. In 1968, the ENT residency program averted the threatened shutdown, instead receiving the “full approval of the Residency Review Committee.”

Later accounts of how the section overcame probation are varied. One account even goes so far as to state that neither the ENT department nor Mayo Clinic was aware of the residency’s probationary status (T. J. McDonald, MD, written communication, June 17, 2002).19 In truth, the Board of Governors was notified before probation and given updates as the department worked through the problem. In Dr K. M. Simonton’s unpublished memoir of his time at Mayo Clinic, he credits incoming chair Dr Cody with bringing the department together and recruiting the needed faculty.27 However, a careful reading of the 1967 report to the Board of Governors indicates that Dr Simonton, still the chair of the department, would have played a large part in the process. Undoubtedly, he and Dr Cody worked together with the other members of the education committee, but another hint comes in 1973 with Dr Cody’s Biennial Department Review, which begins with a retrospective of the history of the ENT department and indicates that the Board of Governors “determined that it was advisable that at least some of the traditional areas of Otorhinolaryngology such as laryngology and head and neck oncology return to the Department of Otorhinolaryngology.” Thus, it may have been the intervention of the Board of Governors itself that finally pulled the section into a distinct, recognizable Department of Otorhinolaryngology.

The Mayo Clinic ENT residency program had made it into the Space Age, but not without hitches. Ten years after coming off its near-terminal probation, the residency program had another brush with the RRC. Being located in a relatively rural area of the country, residents in Rochester were not receiving sufficient surgical education in facial trauma. Otorhinolaryngology was able to establish a practice at Saint Marys Hospital, but because the cases were too few and far between, the partnership with the University of Minnesota, which still conferred the graduate medical degrees from Mayo Clinic, was expanded so that Mayo residents would spend a month at Hennepin County Medical Center to gain that experience. This is a partnership that has lasted to the present day, even after the original agreement with the university was terminated.

Mayo Clinic was expanding, and the medical field itself was booming beyond medical advancements with the rise of pharmaceutical giants and the reign of powerful insurance companies. The regulation and standardization of graduate medical education solidified with the formation of the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. The ENT residency program at Mayo Clinic expanded from 15 residents per year to a maximum of 25 per year, from 9 teaching staff members in 1970 to 18 in 2018, from 4 years of training to 5 years and encompassing all elements of ENT, from 100 applications per year for residency to over 350. In 1987, Dr H. B. Neel III, was able to note that the residency program had grown to include residents from across the country: “Finally, we have a ‘national’ residency program, I believe.”

Graduated Responsibility

Throughout the 1970s and 1980s, the Department of Otolaryngology saw department chairs Drs D. T. Cody and H. B. Neel continuing the difficult process of consolidating the ENT practice and recruiting faculty into each of the subspecialties, which significantly broadened the scope of learning for residents.

By the end of the 1980s, the rotation schedule was set, and with this focused training, residents were able to take on more responsibility for patient care earlier in their residency, which prepared them for their fifth year of residency when they were promoted to Chief Resident Associate in addition to Clinical Instructor and given their own semiautonomous clinic to run side-by-side with faculty. Besides caring for patients in the clinic and achieving near autonomy in the operating room, the chief resident gained enough experience and knowledge to step into the educator role with weekly Chief Resident Associate Grand Rounds and supervising junior residents in the operating room.

Historically, not all residency structures functioned like this. From the start, the ENT residency program at Mayo Clinic was built on a rectangle system,5,28,29 a system that was formally recognized in 1937 as developed by Edward Delos Churchill but practiced at Mayo Clinic from its initiation.28,30 In contrast, most other institutes across the country practiced the traditional pyramidal (Halsted) system, in which residencies began with a full complement of trainees and then each year trainees would be eliminated until eventually at the end of the residency only the very “best” resident would have completed the program in its entirety.31,32 Although residents who were eliminated from the program were still capable and able to find positions,29 the pyramidal system compounded the already incredible stress and competition of the residency. Arguably, trainees’ concentration was not on patient care; it was on survival. In a rectangular system, all trainees who succeeded and persisted would be assured of the opportunity to complete the residency in its entirety and thus have a full range of prospects after graduation, whether to private practice, academic otolaryngology, or research, which was a late addition to the residency.

At the start, residents were generally not involved in research projects at all. Occasionally a “volunteer student” would join the group for a limited time to work on research,33 rather like today’s research fellows. Research was always acknowledged as a benefit both to patient care and to establish Mayo Clinic’s and its physicians’ reputations, but until the arrival of Dr Thane Cody in 1961, research and writing were relegated to physicians’ spare time after clinic hours, which makes the extensive research of early Mayo physicians such as H. I. Lillie, H. F. Wilkinson, and W. B Stark all the more impressive. The only exception to this restriction was granted to Dr Williams, who was allowed to use a portion of his mornings and not report to the clinic on his surgical days so he could work on projects.24 Dr Cody was the first to be hired with the understanding that he would have dedicated research time twice a week, with time funded by grants rather than the department.24 At the same time, he was immediately able to draw residents into his projects, thus opening the residency to fully embrace the research shield, and by the early 1980s, residents were taking significant national honors in research.34

Today, although the residency program is significantly different from more than 100 years ago and while oversight of residencies in the United States has grown into an industry unto itself, many of today’s challenges echo days past (Figure 6). As in the 1920s, great effort is made to recruit the most competent residents, although now concern is primarily recognizing and recruiting talent beyond the “fellow men” of the 20s. As in the 1950s, branding the residency program through recognition of the faculty’s and residents’ accomplishments not just clinically but also in research and education takes effort. In addition, the timeworn frustration of today’s burgeoning administrative duties required of faculty and residents was echoed more than 45 years ago by Dr Cody:

Figure 6.

Teaching in the operating room now (A) and then (B; circa 1913, Dr Charlie pictured on the right).

Reproduced with permission of the W. Bruce Fye Center for the History of Medicine, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota.

Although it is recognized that the committee system is democratic and desirable, anything can be done in excess…. It is my own personal opinion that this Biennial Department Report is an excellent example of how a consultants [sic] time can be wasted by the demands of a committee. Everything in this report…has been presented to various committees or subcommittees, or appeared in annual reports, residency review reports or grant applications. I hope that the committee will see fit to either discontinue the annual report or the biennial review.34

Administration of residencies is no longer reliant on the annual departmental report to the sponsoring institution; now there are annual program evaluations, self-studies, site visits, and periodic reviews, as well as monthly reports to maintain oversight, thus opening the door to the education program coordinator role. The ENT residency program at Mayo Clinic found its first official program coordinator in Ms Barbara Chapman, who was in that position for 37 years. In 2019, the residency got a new name, Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery, reflecting the change in the now-called American Board of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery. Those long familiar initials, ABOto, are now replaced by ABO-HNS, signaling not only the future direction of the residency but also the future of ENT as a specialty.

Today the “clinic in the cornfield” has grown out of the cornfield, from a home in the Masonic Temple to stretching between more than 65 clinics, warehouses, office buildings, electrical plants, and historical sites throughout the Rochester area, and, of course, beyond Rochester, Minnesota, to Arizona and Florida. As a school of graduate medicine, Mayo has trained more than 23,000 residents and fellows,16 more than 300 of whom have gone through the otolaryngology residency program. Of course, the city of Rochester has grown with Mayo Clinic and all its residency programs and fellowships. The streets are paved, electricity flows, and a bucket and shovel are no longer required to clean up after traffic (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

A, Downtown Rochester, Minnesota, circa 1902 and present day. B, Saint Marys Hospital, circa 1898 and present day.

Reproduced with permission of the W. Bruce Fye Center for the History of Medicine, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota.

Footnotes

Potential Competing Interests: The authors report no competing interests.

References

- 1.Rochester Public Utilities. History. https://www.rpu.org/about-rpu/history.php Accessed November 27, 2018.

- 2.Amondson C. 10 Dangerous drugs once marketed as medicine. Best Medical Degrees website. https://www.bestmedicaldegrees.com/10-dangerous-drugs-once-marketed-as-medicine/ Published April 8, 2013. Accessed November 27, 2018.

- 3.Cantrell R.W., Goldstein J.C. The American Board of Otolaryngology, 1924-1999: 75 years of excellence. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1999;125(10):1071–1079. doi: 10.1001/archotol.125.10.1071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Flexner A. Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching; New York, NY: 1910. Medical Education in the United States and Canada: A Report to the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching. Bulletin No. 4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boes C.J., Long T.R., Rose S.H., Fye W.B. The founding of the Mayo School of Graduate Medical Education. Mayo Clin Proc. 2015;90(2):252–263. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2014.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Physicians of the Mayo Clinic and the Mayo Foundation. University of Minnesota Press; Minneapolis, MN: 1937. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stevens R. University of California Press; London: 1971. American Medicine and the Public Interest. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Teamwork at Mayo Clinic Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research. Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research; Rochester, MN: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nelson C.W. Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research; Rochester, MN: 1990. Mayo Roots: Profiling the Origins of Mayo Clinic. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mayo W.J. Medical education for the general practitioner. J Am Med Assoc. 1927;88(18):1377–1379. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mayo C.H. Educational possibilities of the National Medical Museum: in the standardization of medical training. J Am Med Assoc. 1919;73(6):411–413. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cooke M., Irby D.M., Sullivan W., Ludmerer K.M. American Medical Education 100 years after the Flexner report. N Engl J Med. 2006;335(13):1339–1344. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra055445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Duffy T.P. The Flexner Report—100 years later. Yale J Biol Med. 2011;84(3):269–726. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dornan T. Osler, Flexner, apprenticeship and 'the new medical education.'. J R Soc Med. 2005;98(3):91–95. doi: 10.1258/jrsm.98.3.91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Braasch W.F. Charles C Thomas; Springfield, IL: 1969. Early Days in the Mayo Clinic. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Frank A. History of Mayo Clinic School of Graduate Medical Education: #ThrowbackThursdays. Mayo Clinic Laboratories website. https://news.mayocliniclabs.com/2017/03/23/history-mayo-clinic-school-graduate-medical-education-throwbackthursdays/ Published March 23, 2017. Accessed January 31, 2019.

- 17.Mirza M., Koenig J.F. In: Surgeons as Educators: A Guide for Academic Development and Teaching Excellence. Köhler T.S., Schwartz B., editors. Springer International Publishing; Cham, Switzerland: 2018. Teaching in the operating room; pp. 137–160. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mayo Historical Unit. MHU-0002: Board of Governors Records. Box 072; Subgroup 02; Series 03, Subseries 07; Folders 001-015. W. Bruce Fye Center for the History of Medicine. Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN.

- 19.Carlson M.L., Olsen K.D. The History of otorhinolaryngology at Mayo Clinic. Mayo Clin Proc. 2017;92(2):e25–e45. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2016.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Medical education in the United States and Canada: thirty-ninth annual presentation of educational data by the Council on Medical Education and Hospitals of the American Medical Association. J Am Med Assoc. 1939;113(9):757–831. [Google Scholar]

- 21.American College of Surgeons Graduate training for general surgery and the surgical specialties. Bull Am Coll Surg. 1939;24(1):5–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Powell D.E., Hunt D. In: Longitudinal Integrated Clerkships: Principles, Outcomes, Practical Tools, and Future Directions. Poncelet A., Hirsh D., editors. Alliance for Clinical Education; North Syracuse, NY: 2016. LICs and the relationship to accreditation and oversight: a U.S. perspective; pp. 283–292. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hamowy R. The Early Development of Medical Licensing Laws in the United States, 1875-1900. J Libert Stud. 1979;3(1):73–119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mayo Historical Unit. MHU-0002: Board of Governors Records. Box 073; Subgroup 02; Series 03, Subseries 07; Folders 016-048. W. Bruce Fye Center for the History of Medicine. Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN.

- 25.Harold Irving Lillie: 1888-1957. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1957;66(4):1198–1201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Medical education in the United States and Canada: 1942-1943. JAMA. 1943;122(16):1085-1125. Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education website. www.acgme.org/About-Us/Publications-and-Resources/AMA-Green-Books Accessed January 31, 2019.

- 27.Simonton KM. Otolaryngology and head and neck surgery at the Mayo Clinic 1885-1970. Mayo Historical Unit. MHU 0670: General and Staff Memoir Collection. Box 13; Folder 243. W. Bruce Fye Center for the History of Medicine. Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN.

- 28.Grillo H.C., Edward D. Churchill and the "rectangular" surgical residency. Surgery. 2004;136(5):947–952. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2004.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ludmerer K.M. Oxford University Press; New York, NY: 2015. Let Me Heal: The Opportunity to Preserve Excellence in American Medicine. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Verrier E.D. The elite athlete, the master surgeon. J Am Coll Surg. 2017;224(3):225–235. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2016.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pellegrini C.A. Surgical education in the United States: navigating the white waters. Ann Surg. 2006;244(3):335–342. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000234800.08200.6c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Polavarapu H.V., Kulaylat A.N., Sun S., Hamed O. 100 Years of surgical education: the past, present, and future. Bulletin of the American College of Surgeons website. http://bulletin.facs.org/2013/07/100-years-of-surgical-education/ Published July 1, 2013. Accessed November 28, 2018. [PubMed]

- 33.Mayo Clinic . Saunders; Philadelphia, PA: 1926. Sketch of the History of the Mayo Clinic and the Mayo Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mayo Historical Unit. MHU-0002: Board of Governors Records. Box 074; Subgroup 02; Series 03, Subseries 07; Folders 049-061. W. Bruce Fye Center for the History of Medicine. Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN.