Abstract

Background

Coaches have the potential to support athlete mental wellness, but many are unsure what to do and concerned they may unintentionally engage in behaviours that negatively impact their athletes. Education has the potential to help coaches engage in primary, secondary and tertiary preventive behaviours related to athlete mental health; however, there exists no empirical or consensus basis for specifying the target behaviours that should be included in such education.

Objective

The aim of this research was to review extant literature about the role of sport coaches in mental health prevention and promotion, and obtain expert consensus about useful, appropriate and feasible coach behaviours.

Design

Modified Delphi methodology with exploration (ie, narrative review) and evaluation phase.

Data sources

Twenty-one articles from PubMed, PsycINFO and ProQuest, and grey literature published by prominent sport organisations.

Eligibility criteria for selecting studies

All studies were English-language articles that focused on the role of coaches as they relate to (1) culture setting in sport, (2) addressing athlete mental health and (3) providing ongoing support to athletes with mental health concerns. No study design, publication date limits or sport characteristics were applied.

Results

The coach’s role should include fostering team cultures that support athlete mental health, encouraging care-seeking and supporting athletes currently receiving mental healthcare.

Summary/Conclusion

The behaviours specified herein have implications for coach education programme development. This study is the first to use a structured Delphi process to develop specific recommendations about the role coaches can play in supporting athlete mental health.

Keywords: athlete, education, mental, health promotion, sport

What is already known?

Coaches can play a role in supporting athlete mental health, but many are unsure what to do and are concerned that they may unintentionally engage in behaviours that negatively impact athletes’ mental well-being.

Mental health education can assist coaches in supporting athlete mental health, with useful education requiring specifying target behaviours for end users.

What are the new findings?

Coaches should foster team cultures that support athlete mental health, help identify and connect at-risk athletes to appropriate mental health resources, and provide ongoing support to athletes currently seeking mental healthcare.

Introduction

Adolescence and emerging adulthood are periods of peak presentation for mental illness.1 While research indicates athletes have better general physical health than their non-athlete peers,2 they experience similar rates of mental illness.3–5 Further, sport participation confers a unique combination of mental health-related risk and protective factors, suggesting the importance of context-specific intervention to prevent harm and promote optimal functioning.4 For example, athletes may be exposed to unique psychological stressors, such as injury, heavy training demands, media attention, performance pressures, identity foreclosure and sport retirement.4 5 Athletes may also participate in sport environments where there is heightened perceived stigma related to mental illness and help-seeking.6 This can impede the early identification of athletes who would benefit from mental health support, either to address mental illness or help heighten subjective wellness.6 7 Mental health concerns left untreated are subsequently associated with worsened symptomatology,5 decreased athletic performance abilities and loss of interest in participating in sporting activities.8

Despite these potential threats, sport has the potential to help promote mental health. Prospective data suggest regular exercise reduces risk of depression.9 Additional potential social, psychological and emotional benefits of sport participation, such as improved communication skills, resilience and self-esteem,2 10 11 are contextually dependent and mediated in part by the types of behaviours, practices and approaches that are normative and valued on a given sports team.12

In recent years, there has been a noted increase in the expectation—from sport organisations and parents—that coaches be involved in supporting athletes’ mental health.8 13 14 Across all levels of sport, coaches are integral in the lives of athletes,15–17 and athletes view sport as an engaging context for learning about mental health.18 However, many coaches are unsure what to do19 and are concerned they may unintentionally engage in behaviours that negatively impact the mental health of their athletes.8 Education has the potential to support coaches in this role4; however, there is currently a lack of theory-based or evidence-based mental health education targeted at the potentially unique learning needs of coaches.20 21 Suggestions have been made that education for coaches should aim to increase their mental health literacy,5 22 and that coaches should be trained to recognise mental health symptomatology, how to facilitate athletes’ help-seeking behaviours and how to refer athletes to evidence-based interventions.5 6 These broad behavioural categories, however, have not been operationalised into concrete behaviours, and there is as yet no consensus or empirical data about whether these behaviours are appropriate for the coach’s role or feasible for coaches to implement. For education to contribute to behaviour change, content must be relevant to the target behaviours.23 Thus, there is a critical need to establish consensus about the role of the coach related to mental health promotion. The present study sought to address this gap by unifying research recommendations and aggregating expert opinion to develop a list of behaviours for coaches in supporting athletes’ mental health.

Methods

Overview and theoretical frameworks

Using a modified Delphi methodology with an exploration and an evaluation phase,24 the goal of the present study was to obtain expert consensus about useful, appropriate and feasible coach behaviours related to mental health promotion.

Mental health definition

We conceptualise mental health using the WHO’s25 definition: ‘a state of well-being in which every individual realizes his or her own potential, can cope with the normal stresses of life, can work productively and fruitfully, and is able to make a contribution to her or his community’. Thus, we discuss mental health as not just the presence or absence of mental health pathology, but also the presence or absence of subjective well-being, consistent with Keyes’s26 dual continuum model. The use of the dual continuum model in sport psychology research is supported by the International Society of Sport Psychology.5

Prevention framework

We conceptualise mental health prevention as occurring at three time points, consistent with the WHO’s prevention framework27: primary population-wide intervention, secondary intervention to reduce prevalence, and tertiary intervention to reduce the burden of disability and prevent relapse. Within the context of sport, this prevention framework has been applied to research exploring the incidence of injury and concussion.28 29 With respect to mental health, we conceptualise primary prevention as efforts to reduce new incidence of mental illness at a population level by modifying existing environments and equipping individuals with the ability to cope with stressful situations.30 As mental illness will inevitably occur despite effective primary prevention, secondary prevention aims to reduce the duration and prevalence of mental illness through early detection and appropriate treatment.30 Tertiary prevention then involves efforts to reduce residual defect among individuals who have been diagnosed and are recovering from mental illness.30

Exploration phase

Narrative review

Guided by the prevention framework,27 30 a narrative review with specific focus on the role of coaches and mental health help-seeking behaviours was conducted in relation to (1) culture setting in sport, (2) addressing athlete mental health and (3) providing ongoing support to athletes with mental health concerns. PubMed, PsycINFO and ProQuest databases were searched for English-language articles using the following key terms: ‘Athlete’, ‘Coach’, ‘Sport’, ‘Team’, ‘Culture’, ‘Climate’, ‘Mental Health’, ‘Mental Illness’, ‘Mental Health Literacy’, ‘Help Seeking’, ‘Support Provision’, ‘Coach-Athlete Relationship’, ‘Stigma’, ‘Barrier’, ‘Facilitator’ and ‘Review’. Pearling of articles was performed to identify additional references. Twenty-one articles were included. Grey literature published by prominent national sport organisations was also reviewed. No study design, publication date limits or sport setting characteristics (eg, age, level of competition) were applied; however, most published literature focused on intercollegiate athlete populations.

Preliminary behaviours

A preliminary list of potential coach behaviours was generated by the authors based on this review. Initial feedback on this preliminary list was sought by an internal working group of content experts, which included coaches, athletes, health educators and licensed mental health professionals, to optimise statement clarity and ensure each statement was reasonable. Behaviours were grouped within three temporal categories, guided by the public health prevention framework.27 30

Evaluation phase

Content experts (coaches, athletes, licensed mental health professionals [counselling psychologists, psychiatrists, team doctors], health educators) were recruited to vote on the preliminary list. A key informant and snowball sampling process guided recruitment. Key informants were members of the National Collegiate Athletic Association’s (NCAA) Mental Health Task Force and USA-based authors of the IOC consensus statement on mental health in elite athletes.31 A subset of individuals meeting one of these criteria were invited to participate as content experts in the study or to refer another individual to participate; coach and athlete participants in particular were recruited through this key informant-led snowball sampling method. A total of 15 participants were recruited through this process (2 coaches, 3 athletes, 8 licensed mental health professionals, 2 health educators). All athlete participants were above 18 years of age.

Content experts were emailed a copy of the narrative review, which they were asked to read before voting, and a link to an anonymous survey hosted on the Qualtrics platform. Voting on each statement occurred on three dimensions: utility, appropriateness and feasibility of the items, each on a 1–9 scale, where higher scores indicated a statement that was more useful/appropriate/feasible.32 Following completion of voting, the mean scores were calculated. Candidate statements achieving a non-rounded value of ≥7 were retained and deemed a consensus ‘yes’, while those with a mean score ≤3 were eliminated and deemed a consensus ‘no’.32 Statements with mean scores ranging between 3 and 7 were revised based on themes emergent from the open-ended comments provided by experts. A second round of voting, which followed the same procedure outlined above (voting and narrative feedback), occurred for the items that required modification. Consistent with prior guidance, voting concluded after two rounds,33 when barriers emergent from the narrative feedback were considered unaddressable within the context of minor statement modifications. Coefficients of variation (CV) were calculated and inspected for each statement (where CV <0.50 indicated acceptable within-item variability) and inspected for stability between rounds of voting to triangulate this qualitative determination that a stopping point had been reached.

Results

Exploration phase: narrative review

Primary prevention

Mental health stigma is a commonly referenced barrier to help-seeking,4 with sport-specific elements of stigma including a belief that care-seeking will result in lost playing time or being perceived as mentally weak in a setting that prioritises toughness.6 20 34 Despite efforts to bring awareness to the issue of mental health, normative and socially reinforced reluctance to seek help has persisted.34 Coaches have the potential to help shape team cultures that normalise, destigmatise and are supportive of mental health help-seeking,6 35 which may function as a form of primary prevention by shifting the willingness of team members to seek care should their own mental health challenges arise.

We define culture as a product of a given social group’s value systems, assumptions and artefacts (eg, language systems, rituals, ceremonies), which emerge through the behaviours and interactions of group leaders and members to shape group norms.36 37 Group leaders are integral to establishing culture since their own behaviours and interactions with group members will shape a group’s accepted normative social behaviours.36 Group members communicate accepted values, assumptions and artefacts to new members, socialising them to behave in accordance with the group’s norms.37 This process of establishing and maintaining culture occurs through modelling and observational learning, which shape expected behavioural outcomes.38

While we were unable to find empirical literature specific to associations between coaching, team culture and mental health, the literature more broadly underscores the importance of coaches in establishing team culture. Schroeder39 interviewed 10 NCAA coaches who successfully established or changed their teams’ cultures to develop winning teams and found that successful cultures are established when coaches clearly communicate a team’s values. The process of establishing team culture is expedited when coaches themselves model value-consistent behaviours and provide positive reinforcement to athletes who demonstrate behaviours consistent with a team’s desired culture.39 Such role modelling and reinforcement are of particular importance since espoused values and knowledge translation efforts about mental health may be undermined if athletes observe behaviours that differ from endorsed behaviours.13 39 Consistent with this conceptualisation, coaches can shape team culture with respect to mental health by shaping the expected consequences of help-seeking.5 22 34 40 Coaches may further reinforce culture by engaging important allies to endorse desired behaviours,6 such as teammates, family and individuals affiliated with sport organisations. Among these allies, peers may be of particular importance,6 18 with strong within-team connections helping facilitate the process of supporting teammates’ mental health.18

A recent review about elite athlete mental health focused on the role of coaches in establishing their team’s organisational climate.4 While culture and climate are different concepts, they are explicitly linked, with climate being understood as the enactment of the values, assumptions and artefacts that comprise a culture.36 Rice and colleagues’4 review concluded that sport climate is influenced by the expectations and environment set by coaches, which can either positively or negatively impact athletes’ levels of stress, anxiety and ability to cope with challenges. Coaches may reduce athlete stress and anxiety, and enhance coping abilities, by establishing a team climate that emphasises process outcomes as opposed to performance outcomes.4 18 Thus, team climate or culture with respect to mental health can be understood as a multidimensional construct that can contribute to both the presence or absence of mental health pathology (through a pathway involving stressors and help-seeking) and the presence or absence of subjective well-being (through a pathway involving a process-oriented approach to sport), consistent with a dual process conceptualisation of mental health.26

Secondary prevention

Consistent with our definition of secondary prevention, effective management of athlete mental health requires early detection of potential concerns and referral to appropriate evidence-based intervention.4 5 22 41 Coaches have the potential to play a key role in this process because they interact with athletes frequently,16 21 and can thus monitor and respond to changes in athletes’ behaviour that may indicate the early onset of potential mental health concerns.5 8 Coaches in many cases are also able to communicate with athletes in a trusted manner that may not be easily replicated by other stakeholders, such as family, peers or academic personnel.8 As such, both athletes6 and parents13 identify coaches as suitable gatekeepers for helping connect athletes to mental health services.

For coaches to successfully act as gatekeepers, it is helpful if they exhibit positive attitudes towards help-seeking,6 conveying to athletes that such behaviours are beneficial and desirable. Further, it is important for coaches to develop strong coach–athlete relationships founded on trust and openness.13 Athletes identify that having a trusting relationship with their coach is a critical factor in determining whether they will speak with their coach about mental health18 and abide by a coach’s encouragement to seek help.6

Foundational to coaches engaging in secondary prevention is being aware of signs and symptoms associated with mental health concerns.14 18 21 22 42 Coaches also need to be aware of their designated responsibilities during emergency and non-emergency mental health situations.14 There is a paucity of literature specifying the role of coaches during mental health emergencies; however, Neal and colleagues41 developed a consensus document outlining emergency mental health referral responsibilities for athletic trainers consistent with our understanding of secondary prevention. The document suggests that when athletes appear violent, emergency services should be contacted immediately, and if athletes appear non-violent but suicidal it is best to call for assistance and remain with the athlete until receiving further instruction. During emergency and non-emergency mental health situations, mental health best practices developed by the NCAA14 underscore that the coach’s role is to facilitate referral to appropriate support. Referral should be made to a licensed practitioner who possesses appropriate competencies and qualifications to provide mental health services.14

Tertiary prevention

Once athletes have chosen to seek help for mental health concerns, encouraging treatment adherence should theoretically help limit morbidity.27 Integral to providing support to athletes receiving mental healthcare is maintaining athletes’ privacy, as breaching confidentiality is a noted barrier to athletes seeking future help.6 In addition, given the sensitivity of mental health concerns, coaches should respect that athletes may desire different levels of communication with their coaches regarding their care.6

Coaches can also limit psychosocial and structural impediments to athletes’ continued access of mental healthcare. This may include checking in with athletes seeking care8 and providing positive reinforcement for such care-seeking behaviours.39 It may also include working with athletes to ensure that sport responsibilities and schedules do not preclude care-seeking, as time constraints are a common barrier that limits athletes’ abilities or willingness to seek help.6 7 43

Additionally, when athletes are taking a break from athletics participation—whether due to care-seeking for mental illness or physical injury—coaches can help athletes stay engaged with the team. Involvement in recreational sport has been shown to help combat social isolation experienced by individuals recovering from mental health challenges,44 and researchers recommend keeping injured athletes engaged with their team to help minimise the risk of developing associated mental health concerns.45 46 Independent of mental health pathology, and consistent with a dual pathway model for mental health, ongoing engagement with the key social network of the sports team can help with the subjective wellness of the care-seeking athlete.4

Evaluation phase: consensus voting

Results from both rounds of voting, as well as an overview of the statement modification process, are included as online supplementary tables. Online supplementary table S1 provides a summary of the first-round voting results. All candidate statements were scored as useful (mean >7); however, concerns arose regarding the appropriateness and feasibility of eight statements. Experts’ open-ended comments were reviewed for these eight statements and modifications were made where appropriate. Online supplementary table S2 provides an overview of statement modifications. Modified candidate statements were then distributed for second round voting. Online supplementary table S3 provides a summary of the second-round voting results. All eight statements were scored as useful and appropriate; feasibility concerns arose with four statements. After reviewing experts’ second-round, open-ended comments and comparing the CV between the rounds of voting (see online supplementary table S4), voting was concluded. Based on the results from the two rounds of voting, a finalised list of coach target behaviours was compiled (see table 1).

Table 1.

List of coach behaviours with expert consensus on utility, appropriateness and feasibility in supporting athlete mental health

| Coach target behaviours | |

| Primary prevention | 1.1 Coaches should verbally communicate to athletes their role in supporting athlete mental health, consistent with their sport organisation’s mental health protocol. |

| 1.2 Coaches should verbally communicate their intention to encourage athletes to consult with a licensed practitioner with mental health service competencies when behaviours that represent mental health concerns are observed. | |

| 1.3 Coaches should verbally communicate with athletes that they believe it is important to seek help (such as, but not limited to, medical, psychological and social support) for mental health concerns. | |

| 1.4 Coaches should verbally communicate with athletes that they believe it is important to support peers in seeking help for mental health concerns. | |

| 1.5 Coaches should enlist the support of relevant stakeholders (including, but not limited to, parents, administrators and support staff) to endorse the importance of athletes seeking help for mental health concerns. | |

| 1.6 Coaches should communicate that sport-specific decision-making (eg, roster selections, playing time and so on) will not be dictated by an athlete’s mental health concerns and/or care-seeking behaviour unless the decision is endorsed by a licensed practitioner with mental health service competencies. | |

| 1.7 Coaches should share with athletes that addressing mental health concerns may improve athletic performance. | |

| 1.8 Coaches should establish bidirectional coach–athlete relationships that emphasise honesty and openness. | |

| 1.9 Coaches should engage in healthy self-care practices. | |

| 1.10 Coaches should not use language that stigmatises mental illness and mental health help-seeking. | |

| 1.11 Coaches should positively reinforce athlete behaviours that are consistent with a team culture supportive of mental health and mental health help-seeking. | |

| 1.12 Coaches should communicate to athletes that they are receptive to feedback in how to improve the team’s culture surrounding athlete mental health. | |

| 1.13 Coaches should communicate to athletes that they are receptive to feedback in how to improve their own abilities in supporting athlete mental health. | |

| Secondary prevention | 2.1 Coaches should attend to changes in athlete behaviour that may indicate the emergence of a mental health concern. |

| 2.2 If coaches are concerned that an athlete is experiencing a non-emergency mental health concern, they should ask how the athlete is feeling and listen to the athlete’s concern to initiate next steps consistent with their sport organisation’s mental health protocol. | |

| 2.3 Coaches should verbally communicate boundaries that govern what they can and cannot do when an athlete discloses mental health concerns or relevant behaviours are observed. | |

| 2.4 Coaches should provide information to athletes experiencing a potential mental health concern about local resources for accessing licensed practitioners with mental health service competencies. | |

| 2.5 In non-emergency situations, coaches should provide the athlete (or the athlete’s parent/guardian if the athlete is a minor) with information about where care can be sought from a licensed practitioner with mental health service competencies. | |

| 2.6 If coaches think an athlete may be an immediate threat to the safety of others, coaches should contact emergency services. | |

| 2.7 If coaches think an athlete may be a threat to themselves, coaches should follow their sport organisation’s emergency mental health protocol, unless there is no protocol in which case coaches should remain with the athlete until emergency services or a licensed practitioner with mental health service competencies has initiated next steps for care. | |

| Tertiary prevention | 3.1 Coaches should provide positive reinforcement to athletes who are actively engaged in seeking mental healthcare. |

| 3.2 Coaches should provide consistent ongoing support to all athletes regardless of an athlete’s relative athletic ability and skill level. | |

| 3.3 Coaches should protect the confidentiality of athletes’ mental health help-seeking, consistent with athletes’ preferences. | |

| 3.4 Coaches should respect athletes’ desired levels of coach involvement in discussing and supporting the medical and/or psychological management of mental health concerns. | |

| 3.5 Coaches should express to athletes a willingness to modify sport-related responsibilities to accommodate treatment and recovery. | |

| 3.6 Coaches should continue to offer athletes opportunities for engagement in team activities if athletes are taking a break from competition due to mental health concerns. |

bmjsem-2019-000676supp001.pdf (96.1KB, pdf)

Discussion

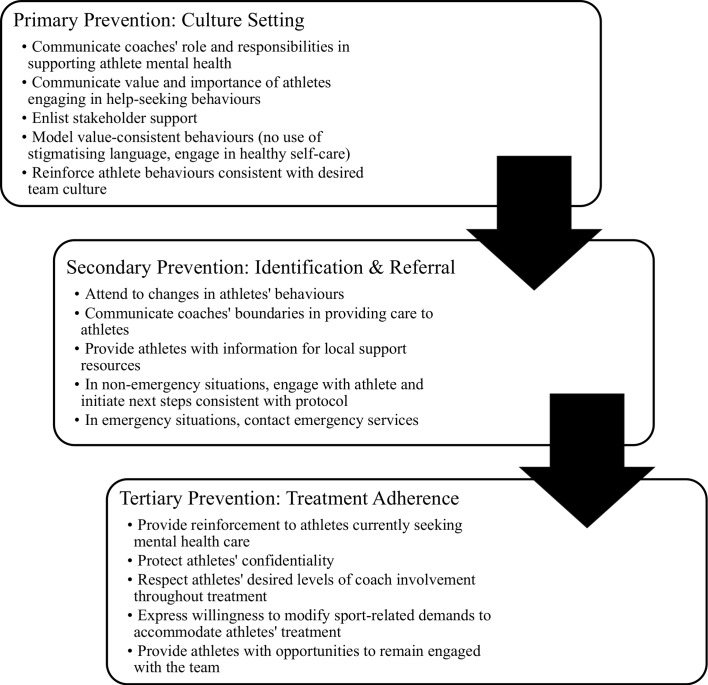

Findings from the present study identify useful, appropriate and feasible behaviours for coaches inclusive of primary, secondary and tertiary prevention of poor mental health. This study is the first to unify specific behavioural recommendations for coaches based on extant literature and use a structured Delphi process to determine a suggested behavioural role of coaches in supporting athlete mental health. The identified behaviours (summarised in figure 1) may be used to inform the development of appropriately targeted mental health coach education. Critically, a recent systematic review of sport-specific mental health awareness programmes highlighted the lack of theory-based or evidence-based education targeted at the unique learning needs of coaches.20 This review found that the majority of existing coach education focuses primarily on developing coaches’ abilities to detect at-risk athletes and connect them with support resources.20 Mental health coach education developed by the NCAA47 provides an example of a more holistic educational approach since it not only addresses signs, symptoms and referral procedures, but also provides examples of behaviours coaches may engage in to foster positive team cultures surrounding mental health. None of these existing resources address all of the behavioural responsibilities emergent from the present Delphi process. Perhaps most critically, given the gap between expert recommendations and resources for coaches, is the need for programming to help develop coaches’ behavioural capacities to foster team cultures that are supportive of athlete mental health and provide support to athletes after they have sought care.

Figure 1.

Summary of the principal primary, secondary and tertiary behavioural capacities for coaches in supporting athlete mental health.

Results from expert voting also highlighted various areas where despite suggested target behaviours being deemed useful and appropriate, experts felt they were not feasible. Several of these feasibility concerns related to uncertainty about organisational buy-in and engagement, such as experts’ perceptions that most sport organisations have yet to develop mental health policies. This suggests that while coaches may play an important role in fostering a culture that is supportive of athlete mental health, a top-down approach may be needed to assist coaches in assuming this role. Similarly, feasibility concerns arose in terms of available and accessible resources, as well as time demands on coaches. Collectively, this suggests a need for future research to identify what resources and support are needed to help coaches engage in this expanded role related to mental health promotion.

Additional feasibility concerns arose about asking coaches to engage in behaviours that are not necessarily encouraged or supported within their sport environment. For example, several participants felt the emphasis sport culture places on winning may induce pressure that interferes with coaches’ abilities to adequately support their athletes’ mental health. As such, the recommendation that coaches moderate sport-related demands during high stress time periods was not deemed feasible. Open-ended feedback noted that high personal stress time periods (eg, final exams) may coincide with periods in which coaches are expected to have their athletes at peak performance. Interestingly, this conflicts with prior research indicating that athletes’ performances may be negatively impacted if a sport-related requirement coincides with the timing of another substantial life-cycle event, such as when athletes must compete at the same time as completing exams.48 Helping moderate athletics demands during these time periods may in fact help with performance optimisation. Thus, it may be useful to share information with coaches about how helping manage stressors and promoting athlete mental wellness can positively impact their team’s athletic performance. Broader organisational efforts may also be needed,49 such as structuring coach incentives where mental health promotion is valued independent of how it impacts athletic performance.

Similar feasibility concerns also arose in relation to the recommendation that coaches share with athletes ways in which they personally tend to their own mental well-being, suggesting that coaches may partake in poor self-care practices and raising questions around how coaches receive support for their own mental health. Prior research has found that elite sport coaches face various performance and organisational stressors that can impact their well-being50; however, there is limited research exploring how coaches tend to their personal mental health. Literature on physician burn-out provides a somewhat comparable context, and a recent review of physician well-being interventions suggests that combining the use of various self-care practices, such as emotion regulation, relaxation techniques and coping strategies, may help minimise the threat of burn-out if implemented at both an individual and institutional level.51 While research specific to sport coaches is limited, one intervention study using mindfulness training among a sample of collegiate coaches showed positive results for improved general well-being, evidenced by coaches experiencing decreased levels of anxiety, greater emotional stability, improved work–life balance and more effective interactions with their athletes.52 Collectively, these findings suggest that providing coaches with their own resources to manage their respective mental health may improve their abilities to support athlete mental health and is a viable area for future research.

Expert voting further highlighted feasibility concerns regarding coaches’ abilities to maintain open communication in relation to athletes’ general life stressors, athletes previously identified to have mental health concerns, and to seek feedback on their support provision practices. Feasibility concerns were largely related to athletes’ confidentiality and hesitancy that coaches would not have the skills to engage in appropriate conversation, while also alluding to perceptions that such open communication is not commonplace within sport. Prior research has suggested that coaches are often able to communicate in a more trusted manner with athletes when compared with other stakeholders,8 and there is existing online coach education highlighting the importance of open communication surrounding mental health and wellness between coaches and athletes.47 Feasibility concerns about this behaviour suggest a need to better support coaches in developing their communication skills related to athletes’ well-being. Future research should seek to explore how such skills may be built into coach education and explore whether such communication training may be sufficiently completed in an online format or require in-person training.

Collectively, the feasibility concerns raised in the present study provide an important commentary on present-day sport culture surrounding mental health. Group leaders—and in the sport setting, coaches—have tremendous power to shape group norms and in doing so affect cultural change. However, coach behaviour is nested in their organisational context that tells them what is valued by what is rewarded, and the broader contemporary sport culture that communicates messaging about what it means to be a successful athlete or coach. Regardless of aetiology, if coaches are not actively prioritising and discussing mental health, there is a likelihood that athletes may follow suit and not engage in healthy mental health behaviours themselves.

Lastly, it is important to note that the coach is only one stakeholder in mental health promotion, and that their role, while important, is also limited. For example, return to play is an area that should be determined by a licensed mental health practitioner and not a coach. As such, future research should seek to explore potential policy-level areas that help to more clearly strengthen the role definition of coaches and enable coaches to feel more comfortable and empowered within their defined role. At present, there are no consistent coaching requirements about any health or safety-related topics. As interest continues to grow in mental health promotion among sport settings, there may be opportunity for policy-level approaches to universally introduce required mental health training for coaches, consistent with previous researcher recommendations.5

Study limitations

While the selected expert sample size was within the appropriate guidelines of a Delphi process,53 the sample was small, meaning that opinions will not reflect all experiences despite efforts to reach a diverse group of experts. Second, findings from this study may or may not be generalisable to all/other levels of sport (eg, recreational, professional) and do not distinguish between noted differences in help-seeking behaviours between genders and team/individual sport athletes. Based on the present review and consensus process, findings do not indicate that coach behaviours should differ depending on athlete gender or team/individual sport participation. Nonetheless, coaches working with male athletes6 40 and individual sport athletes4 should be made aware that these athletes may experience more difficulty in seeking help when compared with female and team sport athletes. Third, findings from this study do not identify what coaches need to know in relation to athlete mental health, focusing rather on behaviourally operationalising the role of the coach. Lastly, this study is a consensus process based on opinion, meaning that if new data become available the suggested target behaviours may need to be revised. Ideally, there will be enough empirical data and evidence in the future to answer the present research questions in a systematic quantitative manner. The paucity of literature explicitly exploring the role of coaches in supporting athletes’ mental health explains why a narrative and not a systematic review was used in the present study. The researchers acknowledge the limitations associated with using a narrative review, including the likelihood of findings being presented in a biased manner that better represents researchers’ perspectives54; however, given the limited completeness of relevant literature on this topic, a systematic review may have been too stringent to produce an overview of literature that would adequately inform experts during the voting process.

Conclusion

Supporting athlete mental health requires a cultural shift within sport, which includes recognising the importance of and varied ways in which to engage coaches in mental health promotion. Existing educational resources for coaches do not address all of the ways in which coaches can usefully, appropriately and feasibly promote athlete mental health. Programme development work is needed to build educational resources that support coaches in engaging in the range of behaviours identified through the present consensus process. However, organisational and cultural barriers to coach action must be considered, with coach education one component of a multilevel approach to creating sport cultures that support athlete mental health.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all those who contributed their time and effort to the consensus voting process.

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors have made substantial contribution to either the conception and design, analysis and interpretation of data, or drafting and reviewing the article. All authors have seen and given final approval for submission of the article.

Funding: The study was funded by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (SSHRC), Michael Smith Foreign Study Supplement.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: Study activities were classified as exempt by the University of Washington Institutional Review Board.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. National Institute of Mental Health Mental illness, 2017. Available: https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/mental-illness.shtml [Accessed 7 Mar 2019].

- 2. Snyder AR, Martinez JC, Bay RC, et al. Health-Related quality of life differs between adolescent athletes and adolescent nonathletes. J Sport Rehabil 2010;19:237–48. 10.1123/jsr.19.3.237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Gulliver A, Griffiths KM, Mackinnon A, et al. The mental health of Australian elite athletes. J Sci Med Sport 2015;18:255–61. 10.1016/j.jsams.2014.04.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Rice SM, Purcell R, De Silva S, et al. The mental health of elite athletes: a narrative systematic review. Sports Med 2016;46:1333–53. 10.1007/s40279-016-0492-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Schinke RJ, Stambulova NB, Si G, et al. International society of sport psychology position stand: Athletes’ mental health, performance, and development. Int J Sport Exerc Psychol 2018;16:622–39. 10.1080/1612197X.2017.1295557 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gulliver A, Griffiths KM, Christensen H. Barriers and facilitators to mental health help-seeking for young elite athletes: a qualitative study. BMC Psychiatry 2012;12:157 10.1186/1471-244X-12-157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. López RL, Levy JJ. Student athletes' perceived barriers to and preferences for seeking counseling. J Coll Couns 2013;16:19–31. 10.1002/j.2161-1882.2013.00024.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Mazzer KR, Rickwood DJ. Mental health in sport: coaches' views of their role and efficacy in supporting young people's mental health. Int J Health Promot Educ 2015;53:102–14. 10.1080/14635240.2014.965841 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Motl RW, Birnbaum AS, Kubik MY, et al. Naturally occurring changes in physical activity are inversely related to depressive symptoms during early adolescence. Psychosom Med 2004;66:336–42. 10.1097/01.psy.0000126205.35683.0a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Eime RM, Young JA, Harvey JT, et al. A systematic review of the psychological and social benefits of participation in sport for children and adolescents: informing development of a conceptual model of health through sport. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2013;10:98 10.1186/1479-5868-10-98 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Holt NL, Neely KC, Slater LG, et al. A grounded theory of positive youth development through sport based on results from a qualitative meta-study. Int Rev Sport Exerc Psychol 2017;10:1–49. 10.1080/1750984X.2016.1180704 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Fraser-Thomas JL, Côté J, Deakin J. Youth sport programs: an Avenue to foster positive youth development. Physical Education & Sport Pedagogy 2005;10:19–40. 10.1080/1740898042000334890 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Brown M, Deane FP, Vella SA, et al. Parents views of the role of sports coaches as mental health gatekeepers for adolescent males. International Journal of Mental Health Promotion 2017;19:239–51. 10.1080/14623730.2017.1348305 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14. National Collegiate Athletic Association Mental health best practices, 2017. Available: http://www.ncaa.org/sport-science-institute/mental-health-best-practices [Accessed 18 Mar 2019].

- 15. Bloom GA, Falcão W, Caron J. Coaching high performance athletes: Implications for coach training : Gomes AR, Resende R, Albuquerque A, Positive human functioning from a multidimensional perspective. Hauppage, NY: Nova Science, 2014: 107–32. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kim J, Bloom GA, Bennie A. Intercollegiate coaches’ experiences and strategies for coaching first-year athletes * . Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health 2016;8:394–408. 10.1080/2159676X.2016.1176068 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Watson JC, Connole I, Kadushin P. Developing young athletes: a sport psychology based approach to coaching youth sports. Journal of Sport Psychology in Action 2011;2:113–22. 10.1080/21520704.2011.586452 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Swann C, Telenta J, Draper G, et al. Youth sport as a context for supporting mental health: adolescent male perspectives. Psychol Sport Exerc 2018;35:55–64. 10.1016/j.psychsport.2017.11.008 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kroshus E, Chrisman S, Coppel D, et al. Coach support of high school student-athletes struggling with anxiety or depression. Journal of Clinical Sport Psychology 2018:1–26. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Breslin G, Shannon S, Haughey T, et al. A systematic review of interventions to increase awareness of mental health and well-being in athletes, coaches and officials. Syst Rev 2017;6:177 10.1186/s13643-017-0568-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Sebbens J, Hassmén P, Crisp D, et al. Mental health in sport (MHS): improving the early intervention knowledge and confidence of elite sport staff. Front Psychol 2016;7 10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00911 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Henriksen K, Schinke R, Moesch K, et al. Consensus statement on improving the mental health of high performance athletes. International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology 2019;14:1–8. 10.1080/1612197X.2019.1570473 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bartholomew LK, Parcel GS, Kok G. Intervention mapping: a process for developing theory and evidence-based health education programs. Health Educ Behav 1998;25:545–63. 10.1177/109019819802500502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Adler M, Ziglio E. Gazing into the Oracle: The Delphi Method and Its Application to Social Policy and Public Health. London, England: Jessica Kingsley Publishers, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 25. World Health Organization Mental health: a state of well-being, 2014. Available: https://www.who.int/features/factfiles/mental_health/en/ [Accessed 26 Mar 2019].

- 26. Keyes CLM. The mental health continuum: from languishing to flourishing in life. J Health Soc Behav 2002;43:207–22. 10.2307/3090197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. World Health Organization Prevention and Promotion in Mental Health. World Health Organization, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Drew MK, Cook J, Finch CF. Sports-Related workload and injury risk: simply knowing the risks will not prevent injuries: narrative review. Br J Sports Med 2016;50:1306–8. 10.1136/bjsports-2015-095871 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Tator CH. Sport concussion education and prevention. J Clin Sport Psychol 2012;6:293–301. 10.1123/jcsp.6.3.293 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Caplan G, Grunebaum H. Perspectives on primary prevention. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1967;17:331–46. 10.1001/archpsyc.1967.01730270075012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Reardon CL, Hainline B, Aron CM, et al. Mental health in elite athletes: international Olympic Committee consensus statement (2019). Br J Sports Med 2019;53:667–99. 10.1136/bjsports-2019-100715 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Rivara FP, Ennis SK, Mangione-Smith R, et al. Quality of care indicators for the rehabilitation of children with traumatic brain injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2012;93:381–5. 10.1016/j.apmr.2011.08.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Thangaratinam S, Redman CWE. The Delphi technique. The Obstetrician Gynaecologist 2005;7:120–5. 10.1576/toag.7.2.120.27071 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Bauman NJ. The stigma of mental health in athletes: are mental toughness and mental health seen as contradictory in elite sport? Br J Sports Med 2016;50:135–6. 10.1136/bjsports-2015-095570 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Castaldelli-Maia JM, Gallinaro JGdeMe, Falcão RS, et al. Mental health symptoms and disorders in elite athletes: a systematic review on cultural influencers and barriers to athletes seeking treatment. Br J Sports Med 2019;53:707–21. 10.1136/bjsports-2019-100710 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ostroff C, Kinicki A, Muhammad RS. Organizational culture and climate : Weiner IB, Schmitt NW, Highhouse S, Handbook of Psychology, Vol 12: Industrial and Organizational Psychology. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, 2013: 643–76. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Schein EH. Organizational culture and leadership. San Francisco, CA: John Wiley & Sons, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Bandura A. Social Foundations of Thought and Action: A Social Cognitive Theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Schroeder PJ. Changing team culture: the perspectives of ten successful head coaches. Journal of Sport Behavior 2010;33:63–88. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Moreland JJ, Coxe KA, Yang J. Collegiate athletes' mental health services utilization: a systematic review of conceptualizations, operationalizations, facilitators, and barriers. J Sport Health Sci 2018;7:58–69. 10.1016/j.jshs.2017.04.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Neal TL, Diamond AB, Goldman S, et al. Inter-association recommendations for developing a plan to recognize and refer student-athletes with psychological concerns at the collegiate level: an executive summary of a consensus statement. J Athl Train 2013;48:716–20. 10.4085/1062-6050-48.4.13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Etzel EF. Understanding and promoting College student-athlete health: essential issues for student Affairs professionals. NASPA Journal 2006;43:518–46. 10.2202/0027-6014.1682 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Watson JC. Student-athletes and counseling: factors influencing the decision to seek counseling services. College Student Journal 2006;40:35–42. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Magee J, Spaaij R, Jeanes R. “It’s recovery united for me”: Promises and pitfalls of football as part of mental health recovery. Sociol Sport J 2015;32:357–76. 10.1123/ssj.2014-0149 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Cassilo D, Sanderson J. From social isolation to becoming an advocate: Exploring athletes’ grief discourse about lived concussion experiences in online forums. Communication Sport 2019;7:678–96. 10.1177/2167479518790039 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Putukian M. The psychological response to injury in student athletes: a narrative review with a focus on mental health. Br J Sports Med 2016;50:145–8. 10.1136/bjsports-2015-095586 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. National Collegiate Athletic Association Supporting student-athlete mental wellness. Available: http://s3.amazonaws.com/ncaa/files/ssi/mental-health/toolkits/coach/story_html5.html [Accessed 17 Jul 2019].

- 48. Thatcher J, Day MC. Re-appraising stress appraisals: the underlying properties of stress in sport. Psychol Sport Exerc 2008;9:318–35. 10.1016/j.psychsport.2007.04.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Liddle SK, Deane FP, Vella SA. Addressing mental health through sport: a review of sporting organizations' websites. Early Interv Psychiatry 2017;11:93–103. 10.1111/eip.12337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Thelwell RC, Weston NJV, Greenlees IA, et al. Stressors in elite sport: a coach perspective. J Sports Sci 2008;26:905–18. 10.1080/02640410801885933 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Wiederhold BK, Cipresso P, Pizzioli D, et al. Intervention for physician burnout: a systematic review. Open Med 2018;13:253–63. 10.1515/med-2018-0039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Longshore K, Sachs M. Mindfulness training for coaches: a mixed-method exploratory study. J Clin Sport Psychol 2015;9:116–37. 10.1123/jcsp.2014-0038 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53. McPherson S, Reese C, Wendler MC. Methodology update: Delphi studies. Nursing Research 2018;1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Grant MJ, Booth A. A typology of reviews: an analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Info Libr J 2009;26:91–108. 10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjsem-2019-000676supp001.pdf (96.1KB, pdf)