Abstract

Aims

Dietetic intervention improves glycaemic control of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM). The aim of this study was to explore the views of Australian dietitians with respect to the nutritional management of people with T2DM, patient access to dietitians and any suggested improvements for access to and delivery of dietetic services.

Methods

Semi-structured interviews were conducted via telephone with 31 dietitians counselling people with T2DM and consulting a minimum of two sessions per week in private and/or non-private practice.

Results

Participants came from urban and rural areas, public and private practice and with a range of years of practice. Themes that emerged from the interviews included the importance of dietetic services for people with T2DM; the referral pathways and beliefs about lack of referrals to dietitians; the perceptions on adequacy of the current dietetic services available for people with T2DM; and the recommendations on services available for people with T2DM.

Conclusion

Considering the evidence that diet is key in the prevention and management of T2DM, it is suggested current funding and service provision be reviewed with a focus on treating the aetiology of diabetes.

Keywords: Diet, Health sciences, Public health, Clinical research, Health profession, Type 2 diabetes mellitus, Diabetes, Diet, Dietitian, Qualitative research, Health services

Diet; Health sciences; Public health; Clinical research; Health profession; Type 2 diabetes mellitus; Diabetes; Diet; Dietitian; Qualitative research; Health services

1. Introduction

Non-communicable, chronic conditions are the major cause of morbidity and mortality in the western world with metabolic diseases such as obesity, diabetes and cardiovascular disease predominant. The pandemic of obesity has resulted in an unprecedented increase in the prevalence of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) in the 21st century [1, 2].

T2DM accounts for 90% of all diabetes and is one of the most disabling chronic conditions worldwide, resulting in significant human, social and economic costs and placing enormous demands on health care systems [3]. According to the International Diabetes Federation (IDF), around half a billion people have diabetes [4], with the World Health Organisation reporting global numbers rising [5]. The economic burden of diabetes worldwide is estimated at $1.3 trillion, or 1.8% of the global gross domestic product (GDP) [6]. In Australia, about 1.2 million people have T2DM with the total annual cost impact being estimated at $14.6 billion [7]. Diabetes prevalence rates increase with age [8], which is concerning considering our ever-increasing ageing population [9].

It is estimated that two million Australians are at high risk of developing T2DM and are already showing early signs of the condition, commonly known as pre-diabetes [7]. Recent changes to the food supply and dietary patterns, combined with less physical activity means most populations are experiencing more obesity and more T2DM [10].

T2DM can often be managed solely through lifestyle modifications such as following a healthy diet and being physically active [11]. Both diet and exercise help manage blood glucose concentrations and adiposity, via increasing insulin sensitivity and facilitating a healthier body composition. Although, diet is a critical determinant for both the prevention and management of T2DM, changing one's eating habits is a complex undertaking [12, 13]. It requires detailed nutrition knowledge, skills in food preparation, access and affordability for healthy foods such as vegetables, fish, and grainy breads of low glycaemic index as well as the motivation to change. Accredited practising dietitians (APDs) have the training and experience to deliver the counselling and support the patient journey to achieve the dietary patterns that optimize control of blood glucose concentration and other risk factors such as dyslipidaemia, hypertension and obesity.

It has been previously shown that better clinical outcomes are achieved when the dietary intervention is led by a dietitian, as opposed to any other health professional [14]. Even a single session with a dietitian improves HbA1c levels [15]. Dietitian-led counselling improves fasting blood glucose, cholesterol and triglyceride concentrations [16, 17].

It is postulated that improved access to and delivery of dietetic services may improve T2DM outcomes. The aim of this study was to gain insight into the experiences and perspectives of dietitians who counsel people with T2DM, in regards to current dietetic services available including patient access and any suggested improvements in order to derive informed recommendations for delivery of such services.

2. Material and methods

APDs seeing people with T2DM, working in private practice and/or hospital or community centre and counselling patients at least twice a week were invited to participate in the study via an advertisement posted on the electronic newsletter that the Dietitians Association of Australia (DAA) circulates weekly. The total number of APDs involved in diabetes care that this would reach is unknown, but a majority of private practice dietitians are APDs and there were more than 3,600 APDs across all areas of dietetic practice in Australia listed on the database. The recruitment period was from the 13th June 2018 until the 5th July 2018. Participants that volunteered to be interviewed via an email response, were provided with the Participant Information Statement containing information on the research and interview and were interviewed after they provided written informed consent.

Semi-structured interviews via telephone were conducted by one researcher, following a script developed a priori and tested with one APD who was not part of the research study. This qualitative method was used to investigate the participants' insights and experiences given its high reliability and validity [18, 19]. Dietitians were asked details about the sector in which they practiced across Australia; the number of people with T2DM they counselled each week; their beliefs in regards to the importance of dietetic counselling; referrals and their thoughts on the dietetic services available for people with T2DM. They were also asked about their beliefs as to why doctors may not refer patients to dietitians. Opportunity was given to freely explore other themes of their choosing at the conclusion of the interview. The script for the semi-structured interview is shown in Box 1. Following completion of the interview participants received a $20 voucher for their time. This study was approved by the University of Sydney Human Research Ethics Committee (2018/106).

Box 1. Key questions to guide discussion.

-

1)

Do you practice in private or public practice and how many years have you been practicing for?

-

2)

How many patients with type 2 diabetes would you see in a typical week?

-

3)

How important do you think dietetic services are for people with type 2 diabetes? (Can you please elaborate?)

-

4)

Who typically refers you patients with type 2 diabetes? (PROMPT: What is the rough breakdown? - If referrals come from more than one sources)

-

5)

What do you think about the current health services available for people with type 2 diabetes?

-

6)

How many minutes and sessions would you typically spend with a patient with type 2 diabetes? (PROMPT: Do you see them for a follow-up?)

-

7)

Why do you think some people with type 2 diabetes never consult with a dietitian?

-

8)

What do you think of the current number of Medicare-subsidised sessions for people with type 2 diabetes?

-

9)

Would you make any recommendations for the services for people with type 2 diabetes?

-

10)

What other services would you recommend for people with type 2 diabetes? (PROMPT: Aside dietetic services.)

-

11)

Is there anything else you would like to add?

Alt-text: Box 1

Interview transcripts were entered verbatim into NVivo Pro (11th edition) qualitative computer software program (QSR International 2015). Inductive thematic data analysis [20] was used by one author (GS) to determine themes within the interview answers. The focus of the analysis was to synthesise the dietitians' views and experiences regarding the access to and availability of dietetic services for people with T2DM. Initially, five transcripts were used to inform the broad themes for exploration. New themes were added as they emerged until a final coding frame was produced. The findings are reported according to the COnsolidated criteria for REporting Qualitative studies (COREQ) checklist [21].

3. Results

3.1. Participant recruitment and characteristics

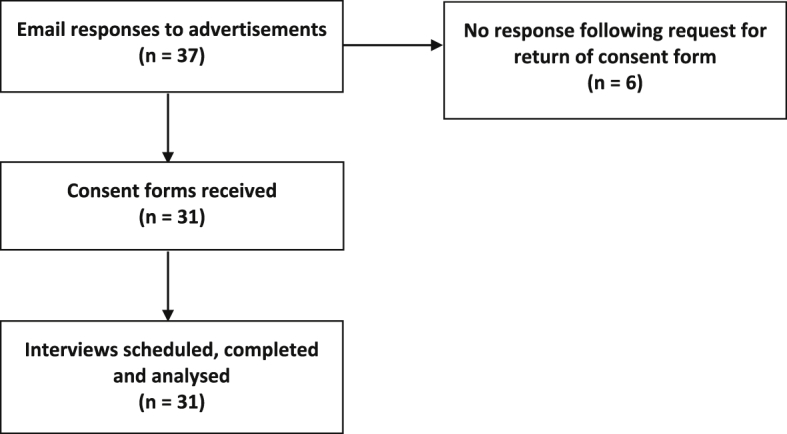

Participant recruitment can be seen in Figure 1. Thirty one participants returned the signed consent form and were interviewed. Six participants did not reply to the email asking for consent; a follow-up email was sent as a reminder to no avail. Interviews lasted from 13 to 25 min. One participant provided written responses to the last five questions of the semi-structured interview due to a bad telephone reception.

Figure 1.

Participant recruitment sequence.

Participant demographic characteristics are shown in Table 1. The participants were recruited from six of the eight states and territories of Australia. More than three quarters of the responders (24) were practising in major metropolitan centres and about one quarter (7) was practising in rural and remote areas, where the workforce population is small. More than half the dietitians had been practising for 10 years or more (52%), about one third had been practising between 5 and 10 years (35%) and the remainder (13%) had been practising for less than 5 years. Both private and public (non-private) practice dietitians were included, with 12 dietitians only practising in private practices, 17 only in public and two practising in both. Of the 19 dietitians in public practice, six practise in hospitals, 10 in community centres, two in non-government organisations (NGO) and one both in a hospital and a community centre. The majority of the interviewees were females (29), reflecting the gender distribution of the profession.

Table 1.

Participant demographic characteristics.

| Sex (M:F), n | 2:29 |

| Seniority, n | |

| ≤2 years | 4 |

| >2 years and ≤5 years | 7 |

| >5 years and ≤10 years | 4 |

| >10 years and ≤20 years | 9 |

| >20 years | 7 |

| Practice1,2, n | |

| Private | 14 |

| Public (Non-Private) | 19 |

| Hospital | 7 |

| Community Centre | 11 |

| Non-Government Organisation (NGO) | 2 |

| Territories3, n | |

| New South Wales (NSW) | 13 |

| Victoria | 12 |

| Australian Capital Territory (ACT) | 5 |

| South Australia (SA) | 1 |

| Tasmania | 1 |

| Northern Territory (NT) | 1 |

| Queensland | 0 |

| Western Australia (WA) | 0 |

| Remoteness of practice location4, n | |

| Metropolitan/Major Cities | 24 |

| Large rural centres | 0 |

| Small rural centres | 2 |

| Other rural areas | 4 |

| Remote centres | 1 |

| Other remote areas | 0 |

Two dietitians practice both in private and in non-private practice.

One dietitian works both in hospital and in community centre.

Two dietitians work in two territories (NSW & ACT).

According to the “Guide to remoteness classifications” produced by the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIWH) in March 2004 [22].

3.2. Dietetic consult characteristics

Dietetic consult characteristics can be seen in Table 2. Most dietitians interviewed see patients one-on-one, with only three reporting running group education. Dietitians reported conducting on average eight counselling sessions with people with T2DM per week. The duration of the one-on-one appointment ranged from 30-90 min for the initial and 20–60 min for follow up visits. Most dietitians (26) report conducting a 60 min initial appointment. The initial appointment was reported to be less, only 30–45 min, in self-reportedly “very busy community centres” that experience a high volume of people with T2DM. A community centre dietitian reported conducting the initial appointment in conjunction with the nurse/diabetes educator. Two dietitians reported running group sessions that are of varied duration, some run for a couple of hours, others for the whole day (7.5hr). The reported duration of the follow-up appointments ranged from 30-60 min, with most dietitians (20) conducting 30 min review appointments. One dietitian working at a reportedly very busy community centre emphasized that the dietetic department is greatly understaffed and experiences such a high volume of patients that dietitians there “try their best to not offer a review”. Most dietitians report seeing each patient on average twice, the initial consult and one follow-up.

Table 2.

Dietetic consult characteristics.

| Estimated average number of people with T2DM seen per week (range), n 8 | (1–18) |

| Most reported range of T2DM people seen by full-time dietitians | 10–15 |

| Most reported range of T2DM people seen by part-time dietitians | 5–6 |

| Average duration of dietetic consult appointment (range), min | |

| Initial (range) | 60 (30–90) |

| Follow-up (range) | 30 (20–60) |

| Average number of sessions per year with same patient1, n | 2 (1–6) |

T2DM, type 2 diabetes mellitus.

One dietitian reported a value based on a true audit. The rest reported estimates.

3.3. Major themes

Four main themes emerged from the 31 interviews following data synthesis, namely the dietitian's opinions on the importance of dietetic services for people with T2DM, the referral pathways and beliefs about lack of referrals to dietitians, the perceptions on adequacy of the current dietetic services available for people with T2DM, and the dietitians' recommendations on services available for people with T2DM.

3.3.1. Importance of dietetic services for people with T2DM

All dietitians (APDs) interviewed emphasized the importance of dietetic consults for the optimal management of T2DM. Words and phrases such as “very important”, “extremely important”, “hugely important”, “crucial”, “critical”, “essential”, “key to management”, “cornerstone with exercise” were used. One dietitian drew attention to the importance of prevention and another to the need for early diagnosis.

“Oh, it is critical! Lots of patients with type 2 diabetes for over 20 years never see a dietitian and it is critical for the management of the condition.” – Participant 1 (M, Urban, Public, 9y experience).

“Extremely important! Often dietetic services are not seen as important. They are not seen as a priority, they usually come after podiatry etc. First we look after the feet of the patient and only if the medication does not work then we look at the diet.” – Participant 6 (F, Rural, Public & Private, 11y experience).

“Dietetic education and counselling are extremely important. Especially to prevent prediabetes developing to diabetes and to reduce use of medication. Losing weight makes such a big difference. Everyone needs to see a dietitian.” – Participant 12 (F, Urban, Private, 2y experience)

3.3.2. Referral pathways and beliefs about lack of referrals to dietitians

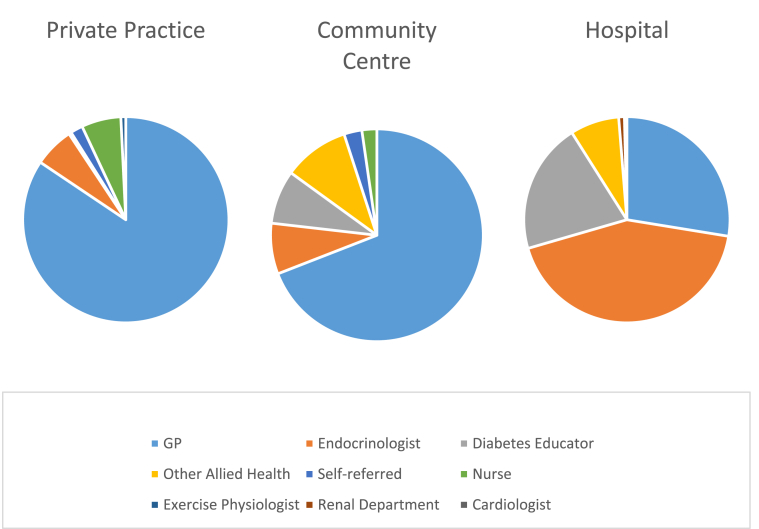

Figure 2 shows the breakdown of sources of referrals in private practices, community centres and hospitals for the participating dietitians. In private practices, the majority of referrals come from general practitioners (GPs) and some practice nurses. In community centres, the majority of referrals also come from GPs, with endocrinologists and diabetes educators contributing the remainder. In hospitals, endocrinologists are the major source of referrals, followed by GPs, diabetes educators and other allied health professionals. Two dietitians working in non-government organisations ran group education sessions for people with T2DM, as well as occasional individual patient consultations. These dietitians reported that their patients come from the National Diabetes Services Scheme (NDSS). In all three settings, very few patients are self-referred.

Figure 2.

Source of referrals in private practices, community centres and hospitals. Dietitians in these three settings were asked what was the rough breakdown of referrals received from different sources (question 4). According to their answers, the majority of referrals to the dietitian in private practice and community centres comes from general practitioners (GP), followed by endocrinologists, whereas in the hospital from endocrinologists and then GP and diabetes educators.

Dietitians had common beliefs about why people with T2DM do not see a dietitian. These include GP-related reasons, patient-related reasons and access-related reasons. The main GP-related reason reported by dietitians was the lack of referrals from GPs. Dietitians believe that many GPs prefer to consult their own patients in regards to diet and do not emphasise to the patient the importance of seeing a dietitian. A few dietitians suggested that some GPs may be lacking an understanding of the benefits of dietetic services for people with T2DM.

“I do not know if GPs value the service that dietitians bring. Some do and they refer their patients but others don't or are not aware of what dietitians can do.” – Participant 22 (F, Urban, Public, 10y experience)

“It really depends on how well the GP sells it [seeing a dietitian]. Sometimes GPs do not refer or they just refer to the practice nurses.” – Participant 16 (F, Urban, Public, 10y experience)

With respect to patient-related reasons for not seeking dietetic services, dietitians believed that patients had limited knowledge about the role of diet or what a dietitian might offer to them with respect to the management of their condition.

“Some patients don't see the value in seeing a dietitian. They think they already know what to do and that the dietitian will tell them what they already know.” – Participant 25 (F, Remote, Public, 8y experience)

Some dietitians stated patients may perceive they already had sufficient knowledge or that they could find all the information they needed on the internet e.g. using Google. Dietitians also stated some patients were reluctant to consult for fear of being shamed or judged that they had made poor diet choices and were to blame for their condition.

“Some patients fear not knowing how they will be perceived. The dietitian is not like the physio(therapist) doing a physical intervention; more like a counsellor, some people fear counselling.” – Participant 12 (F, Urban, Private, 2y experience)

“There is fear that they [patients] are at fault.” – Participant 27 (F, Rural, Private, 4y experience)

Dietitians reported some patients may be completely reluctant to changing their diet and thus seeing a dietitian. It was also suggested that patients had misconceptions about dietitians or that a previous bad experience prohibited them from visiting dietitians again.

“Some patients see us as the food police and they are worried that we will take away all the pleasures of life.” – Participant 9 (F, Urban, Public, 16y experience)

Access-related reasons can be grouped into spatial, temporal and financial access. Spatial access barriers to consulting a dietitian included lack of available services in the area and the clinic's room schedule. Dietitians stated that in clinics where the rooms were far apart, the patient elected to leave the hospital after seeing the doctor and nurse rather than walk all the distance to see the dietitian. The long waiting time for appointments in certain hospitals was a barrier to access but was only reported by one dietitian. Dietitians who worked in paediatric units, mentioned family reasons as a barrier specific in that setting.

“Our approach is family based. If the parents are not willing to make changes e.g. lose weight themselves then they won't bring the kid back. There are other reasons too e.g. not wanting to miss school, pay for parking, transport reasons etc.” – Participant 30 (F, Urban, Public, 27y experience)

Financial access was highlighted as an issue for people seeing dietitians privately, especially in areas of low socioeconomic status (SES).

3.3.3. Perceptions on adequacy of the current dietetic services available for people with T2DM

Answers in regards to the adequacy of dietetic services currently available for people with T2DM were mixed. Dietitians from well-organized urban community centres that offer a variety of programs were satisfied with the level of current services, whereas dietitians practising in remote areas reported that the current offering is not meeting the demand.

“Newly diagnosed patients are given very basic support. We are missing the opportunity to prevent complications at an early stage. As the number of patients increases, the number of services does not, they are not meeting the demand. The quality of expertise is not good. We need more specialized[(diabetes] dietitians.” – Participant 6 (F, Rural, Public & Private, 11y experience)

“There is chronic understaffing. If there is no complication, a type 2 patient may never get an appointment [with a dietitian]. Only if their HbA1c is greater than 11–12 they get an appointment.” – Participant 17 (F, Rural, Public & Private, 20y experience)

“Services are quite limited in our setting. We are an outreach service. Remote Australia is understaffed. We have four dietitians that service 20 remote communities. They used to be six, but now they are down to four”. – Participant 25 (F, Remote, Public, 8y experience)

Two dietitians indicated poor communication from GPs with respect to follow-up correspondence. Another dietitian voiced the need for more specialist dietitians, i.e. diabetes dietitians, to improve the level of expertise and service delivered to the relevant patient. Also the need for adolescent-specific care was raised and the fact that this is yet to be addressed in some states.

Dietitians agreed that the number of government-subsidised sessions is insufficient to ensure the long-term management of a chronic progressive condition such as T2DM, including its possible complications that may require the involvement of nearly the whole spectrum of allied health professions. A few dietitians mentioned most patients they see use all of funded sessions on podiatry. The dietitians also stressed they know that research shows that regular follow-ups with the dietitian are needed for optimal weight management, a key contributor to the success of T2DM management.

“Five visits are definitely not enough at all for someone with a chronic condition, especially type 2 diabetes. These people need to see podiatrists, exercise physiologists to lose weight etc. There should be at least one visit per allied health. Ideally it should be like the mental health plan. It is a good idea to look at the income [of the patient] and charge a gap per visit.” – Participant 2 (F, Urban, Private, 5y experience)

APDs emphasized that there should be a number of sessions designated to the dietitian due to its importance in the management of T2DM. Dietitians stated the recommended average number of sessions with the dietitian should be four per year, especially for the newly diagnosed patients. Others suggested that the number of allocated sessions to the dietitian should be determined by the patients' HbA1c concentrations.

3.3.4. Recommendations on services available for people with T2DM

Participants were asked what other services, besides dietetics, they consider key for the effective management of T2DM. The majority of dietitians reported that psychology and exercise physiology sessions are paramount.

“Psychology might help, especially people having emotional issues with food.” – Participant 12 (F, Urban, Private, 2y experience)

“Diabetes stress is very common. Many people do not manage their diabetes well because they have other things in their lives which they prioritise. If they can manage other aspects of their life better with the help of a psychologist, then their diabetes management could also improve.” – Participant 20 (F, Rural, Public, 4y experience)

Exercise physiology was seen equally as important and the need for several sessions with an exercise physiologist was emphasised.

“Nobody will change their habits by seeing an exercise physiologist just once. People need a good 10–12 regular sessions before a change takes place.” – Participant 8 (F, Rural, Private, 11y experience)

A couple of dietitians reported difficulty in finding the right program or exercise physiologist to refer their patients to. Podiatry was also strongly recommended by the dietitians and about one-third suggested referral to a diabetes educator was important. Dietitians agreed that all allied health has a place in the effective management of T2DM and they stressed that patients should be exposed to different services in a progressive manner, so that they “do not get overwhelmed”.

“Muscle is important for diabetes management and overall wellbeing. However, sometimes I find it hard to find the right program and exercise physiologist to refer to.” – Participant 31 (F, Urban, Private, 10y experience)

Three dietitians raised the importance of prevention. It was strongly suggested to place emphasis on earlier diagnosis of prediabetes and of T2DM through better histories obtained by the GP or nurse and annual screenings of HbA1c, ideally to prevent prediabetes progressing to diabetes. Better communication between GPs and dietitians and education of GPs as to the benefits of dietetic intervention were indicated. Other suggestions included better utilization of group education to cut back on clinician time, an increase in the number of dietitians to match the demand in specific areas and an increase in government funding, including an increase in the government subsidy, to improve access and reduce waiting times. The importance of a consistent long-term intervention was stressed.

“Some patients see the referral with the dietitian and the exercise physiologist as all they need, i.e. to see them once. Whereas really this is just the starting point and a long-term intervention involving many sessions is needed to achieve positive outcomes.” – Participant 27 (F, Rural, Private, 4y experience)

A dietitian working in a remote area with a high turnover of staff added:

“Here in remote Australia there is some fly-in/fly-out services but there are limitations. We need long-term staff to build relationships with patients. The patient is reluctant to engage with a new carer all the time. It is a very expensive and ineffective model.” – Participant 25 (F, Remote, Public, 8y experience).

Another suggested changes at a legislative level:

“People are eating an addictive diet full of sugar and fat. Changes need to be made on a government and legislative level so that people don't need to make decisions, the decisions have been made for them. People then can make mindless decisions knowing that the options are healthy.” – Participant 31 (F, Urban, Private, 10y experience)

4. Discussion

The aim of this research was to study the experiences and perspectives of dietitians who counsel people with T2DM in regards to current dietetic services available, including patient access and any suggestions for the improvement of access to and delivery of these services. The findings highlight the dietitians' belief that dietary counselling is crucial for people with T2DM. Dietitians suggested that people with T2DM need to consult with them on average four times per annum and emphasized a current lack of referrals from physicians, with some believing it stems from a preference of GPs to counsel their patients themselves concerning their diets. Dietitians stated patient barriers to seeing a dietitian were misconceptions about the dietitian's role and lack of understanding of the value this type of counselling adds to the management of their condition. Dietitians recognized the importance of other allied health professionals' input, particularly of exercise physiology and psychology, especially early on, to prevent further progression and deal with stress. Dietitians commented the limited current reimbursement offered by Medicare for allied health visits, the cost of seeing a dietitian privately and the lack of such services in rural and remote areas, prevented optimal dietary management for people with T2DM.

Dietitians reported initial consultations average 60 min and follow-ups 30 min. This agrees with standard dietetic practices in Australia [23]. Appointment time has been recognised as an important factor in terms of patient engagement, in addition to a “patient-centred-care” approach [24].

Barriers to seeing dietitians for people with T2DM were both person-centred and system-centred. Dietitians expressed concern that patients often have misconceptions about the dietetic profession that prevent them from seeing a dietitian. It is important that physicians clearly understand the role of dietitians to support their patients and encourage them to consult an APD [12, 13, 14, 16, 17].

Affordability is a major factor impeding access to dietitians. The government's chronic disease management program only subsidises a maximum of five allied health visits per annum [25]. This is insufficient when it must be spread among all allied health visits. Although it has been previously reported that even a single session with a dietitian improves HbA1c levels [15], to achieve the long-term results desired in a chronic condition such as T2DM, often including fat loss, patients require frequent visits to the dietitian [26]. Considering body composition changes require time to occur [27], most dietitians recommended an increase of the number of government-subsidised sessions, with the consensus being four to five mandatory sessions committed to the dietitian. A few dietitians suggested the current Medicare subsidy amount of $52.95 is low and in many cases it is not enough to cover the dietitian's fee, in agreement with previous reports [28]. Investing in the dietary management of T2DM is likely to decrease the risk of complications and therefore alleviate the $14.6 billion burden placed on the national budget by T2DM [7]. A systematic review estimated a return-on-investment (ROI) of about NZ$5.50–$99 for every NZ$1 spent on dietetic intervention [29]. A 2012 report from the Netherlands showed a ROI of €14 to €63 for every €1 spend on dietary counselling: “€56 in terms of improved health, €3 net savings in total health care costs and €4 in terms of productivity gains” [30]. An alternative solution may be a case-by-case evaluation, where there can be a gap surcharge calculated according to the SES of the patient.

Dietitians in the public sector acknowledged that the services in these practices are free and thus cost is not a barrier. However, wait time may be an issue and some dietitians reported limited dietetic services due to chronic understaffing especially in remote areas. A recent mapping of the Australian dietetic workforce indicated an undersupply of services in rural and remote areas [31]. A better match of service provision to demand would yield beneficial results, as the progressive worsening nature of T2DM means seeing a dietitian early is an important component to prevent further complications [32]. More research is needed in regards to access to a dietitian, to elucidate the areas in Australia that need more dietitians to match the demand.

Family reasons were presented as a barrier to seeing a dietitian in the context of paediatric patients. Dietitians working in such units stated that parents who are not willing to embrace a healthy lifestyle refuse to bring the child back to the clinic. Since the number of fat cells stays fairly constant in adulthood and thus the predisposition to obesity by an enhanced capacity to store fat through an increased adipocyte number happens during childhood and adolescence [33], it is important that obesity and diabetes management start at an early stage of life too.

Dietitians often found that psychological barriers prevented patients from following a healthy lifestyle and thus emphasized the need for counselling and support by a psychologist or social worker [34]. Exercise physiology was strongly suggested. This is also supported by a recent Cochrane review that showed that neither diet, nor physical activity alone, compared to standard treatment, had an impact on the risk of T2DM in people at increased risk of developing T2DM. The combination of diet plus exercise reduced or delayed the incidence of T2DM in people with impaired glucose tolerance [35]. Exercise, together with diet, is key for both the management T2DM as well as importantly the prevention of prediabetes and of prediabetes developing into diabetes [36]. Muscle is a crucial organ in the regulation of insulin sensitivity and exercise is the stimulus needed to build and maintain it [37].

The dietitians also raised the need for earlier diagnosis of prediabetes and of T2DM, for prevention. In Australia, it is estimated that the number of people with undiagnosed T2DM ranges between 350,000 and 550,000 (depending on which test is used for the diagnosis) and the number of people with prediabetes is estimated at roughly two million [38]. The need for better communication between physicians and dietitians was apparent, especially since diabetes requires a long-term multidisciplinary intervention.

This research provided a rich dataset enabling the formation of sound conclusions in regards to the current status of dietetic services for people with T2DM. There are however some limitations. The voluntary participation method of recruitment is more likely to recruit dietitians that wish “to be heard”. There is a possibility that people that are more dissatisfied might be more willing to participate in order to voice their issues and concerns, rather than people that may be satisfied with their practice. Given that participants are commenting on the importance of use of their professional services, it is also possible that responses reflect personal and professional interests. The sampling method failed to recruit dietitians from one populous and one smaller state and it remains unknown if their opinions would have been divergent. In general, more in-depth feedback was given by more senior and experienced dietitians. Most of the dietitians interviewed followed the questions used to guide discussion and offered limited additional open conversation. It is acknowledged that only one researcher (GS) coded the interviews.

5. Conclusions

Considering the strong evidence that dietetic consultation improves clinical outcomes for T2DM, government initiatives should focus on improving the equity of access to dietetic services. Investing in dietetic services and exercise physiology is likely to alleviate the heavily burdened national health budget for T2DM associated complications. It is suggested that the number of visits to dietitians and exercise physiologists be reviewed and instead of focusing on treating the symptoms, such as neural and pedal complications [39], the focus is placed on treating the aetiology. Doctors would benefit from improved knowledge of the benefits of dietitian consultations as to how individualised nutrition counselling can improve their patient outcomes. Further research that elicits the opinions of patients and doctors is indicated.

Declarations

Author contribution statement

G. Siopis: performed the experiments; analyzed and interpreted the data; contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; wrote the paper.

M. Allman-Farinelli: conceived and designed the experiments; contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; wrote the paper.

S. Colagiuri: analyzed and interpreted the data; wrote the paper.

Funding statement

G. Siopis was supported by the University of Sydney International Strategic (USydIS) fund scholarship and by the Neville Whiffen scholarship.

Competing interest statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

No additional information is available for this paper.

References

- 1.Ginter E., Simko V. Type 2 diabetes mellitus, pandemic in 21st century. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2012;771:42–50. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4614-5441-0_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Seidell J.C. Obesity, insulin resistance and diabetes—a worldwide epidemic. Br. J. Nutr. 2000;(Suppl 1):S5–8. doi: 10.1017/s000711450000088x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zheng Y., Ley S.H., Hu F.B. Global aetiology and epidemiology of type 2 diabetes mellitus and its complications. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2018;14:88–98. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2017.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.International Diabetes Federation. 2017. http://www.diabetesatlas.org/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.World Health Organisation . 2017. Diabetes Fact Sheet.http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs312/en/ [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harvard School of Public Health . 2018. Worldwide economic burden of diabetes estimated at $1.3 trillion.https://www.hsph.harvard.edu/news/hsph-in-the-news/worldwide-economic-burden-diabetes/ [Google Scholar]

- 7.Diabetes Australia. 2015. https://www.diabetesaustralia.com.au/diabetes-in-australia [Google Scholar]

- 8.Australian Bureau of Statistics . 2018. National Health Survey: First Results, 2017-18.https://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/Lookup/by%20Subject/4364.0.55.001~2017-18~Main%20Features~Diabetes%20mellitus~50 [Google Scholar]

- 9.World Health Organisation . 2017. Life Expectancy.http://www.who.int/gho/mortality_burden_disease/life_tables/situation_trends_text/en/ [Google Scholar]

- 10.Popkin B.M., Adair L.S., Ng S.W. NOW and then: the global nutrition transition: the pandemic of obesity in developing countries. Nutr. Rev. 2012;70(1):3–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2011.00456.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lean M.E., Leslie W.S., Barnes A.C. Primary care-led weight management for remission of type 2 diabetes (DiRECT): an open-label, cluster-randomised trial. Lancet. 2017;391(10120):541–551. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)33102-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Delahanty L., Dalton K.M., Porneala B. Improving diabetes outcomes through lifestyle change--A randomized controlled trial. Obesity. 2015;23(9):1792–1799. doi: 10.1002/oby.21172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Parker A., Byham-Gray L., Denmark R. The effect of medical nutrition therapy by a registered dietitian nutritionist in patients with prediabetes participating in a randomized controlled clinical research trial. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2014;114(11):1739–1748. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2014.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Trento M., Basile M., Borgo E. A randomised controlled clinical trial of nurse-, dietitian- and pedagogist-led Group Care for the management of Type 2 diabetes. J. Endocrinol. Invest. 2008;31(11):1038–1042. doi: 10.1007/BF03345645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ouyang C.M., Dwyer J.T., Jacques P.F. Diabetes self-care behaviours and clinical outcomes among Taiwanese patients with type 2 diabetes. Asia Pac. J. Clin. Nutr. 2015;24(3):438–443. doi: 10.6133/apjcn.2015.24.3.03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barakatun M., Ruzita A., Norimah A. Medical nutrition therapy administered by a dietitian yields favourable diabetes outcomes in individual with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Med. J. Malaysia. 2012;68(1) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu H., Zhang M., Wu X. Effectiveness of a public dietitian-led diabetes nutrition intervention on glycemic control in a community setting in China. Asia Pac. J. Clin. Nutr. 2015;24(3):525–532. doi: 10.6133/apjcn.2015.24.3.07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guba E.G. Criteria for assessing the trustworthiness of naturalistic inquiries. ECTJ. 1981;29(2):75. [Google Scholar]

- 19.May C. More semi than structured? Some problems with qualitative research methods. Nurse Educ. Today. 1996;16(3):189–192. doi: 10.1016/s0260-6917(96)80022-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Braun V., Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tong A., Sainsbury P., Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int. J. Qual. Health Care. 2007;19:349–357. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzm042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Australian Institute of Health and Welfare . 2004. Rural, Regional and Remote Health. A Guide to Remoteness Classifications.http://ruralhealth.org.au/sites/default/files/other-bodies/other-bodies-04-03-01.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brown J.A., Lee P., Ball L. Time and financial outcomes of private practice dietitians providing care under the Australian Medicare program: a longitudinal, exploratory study. Nutrition and Dietetics. J. Dietitians Assoc. Aust. 2015;73(3):296–302. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hancock R.E., Bonner G., Hollindale R. 'If you listen to me properly, I feel good': a qualitative examination of patient experiences of dietetic consultations. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2012;25(3):275–284. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-277X.2012.01244.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cant R., Ball L. Decade of Medicare: the contribution of private practice dietitians to chronic disease management and diabetes group services. Nutr. Diet. 2015;72(3):284–290. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Franz M.J., Boucher J.L., Evert A.B. Evidence-based diabetes nutrition therapy recommendations are effective: the key is individualization. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. 2014;7:65–72. doi: 10.2147/DMSO.S45140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Haw J.S., Galaviz K.I., Straus A.N. Long-term sustainability of diabetes prevention approaches: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. JAMA Intern. Med. 2017;177(12):1808–1817. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.6040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cant R. Public health nutrition: the accord of dietitian providers in managing Medicare chronic care outpatients in Australia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Publ. Health. 2010;7:1841–1854. doi: 10.3390/ijerph7041841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Howatson A., Wall C.R., Turner-Benny P. The contribution of dietitians to the primary health care workforce. J Prim. Health Care. 2015;7(4):324–332. doi: 10.1071/hc15324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lammers M., Kok L. Commissioned by the Dutch Association of Dietitians; 2012. Cost-benefit analysis of dietary treatment. Version 22. SEO Report No. 2012-76A. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Siopis G., Jones A., Allman-Farinelli M. The dietetic workforce distribution geographic atlas provides insight into the inequitable access for dietetic services for people with type 2 diabetes in Australia. Nutr. Diet. 2020 doi: 10.1111/1747-0080.12603. [publised online ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wan E.Y.F., Fung C.S.C., Jiao F.F. Five-year effectiveness of the multidisciplinary risk assessment and management programme-diabetes mellitus (RAMP-DM) on diabetes-related complications and health service uses-A population-based and propensity-matched cohort study. Diabetes Care. 2018;41(1):49–59. doi: 10.2337/dc17-0426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Spalding K.L., Arner E., Westermark P.O. Dynamics of fat cell turnover in humans. Nature. 2008;453(7196):783–787. doi: 10.1038/nature06902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Young-Hyman D., de Groot M., Hill-Briggs F. Psychosocial care for people with diabetes: a position statement of the American diabetes association. Diabetes Care. 2016;39(12):21126–22140. doi: 10.2337/dc16-2053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hemmingsen B., Gimenez-Perez G., Mauricio D. Diet, physical activity or both for prevention or delay of type 2 diabetes mellitus and its associated complications in people at increased risk of developing type 2 diabetes mellitus. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017;12:CD003054. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003054.pub4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.König D., Hörmann J., Predel H.G. A 12-month lifestyle intervention program improves body composition and reduces the prevalence of prediabetes in obese patients. Obes. Facts. 2018;11(5):393–399. doi: 10.1159/000492604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Roberts C.K., Henever A.L., Barnard R.J. Metabolic syndrome and insulin resistance: underlying causes and modification by exercise training. Comp. Physiol. 2013;3(1):1–58. doi: 10.1002/cphy.c110062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dunstan D.W., Zimmet P.Z., Welborn T.A. The rising prevalence of diabetes and impaired glucose tolerance: the Australian Diabetes, Obesity and Lifestyle Study. Diabetes Care. 2002;25:829–834. doi: 10.2337/diacare.25.5.829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mitchell L., Capra S., Macdonald-Wicks L. Structural change in Medicare funding: impact on the dietetics workforce. Nutr. Diet. 2009;66(3):170–175. [Google Scholar]