Abstract

Current guidelines consider thrombosis as a potential (and reversible) cause of cardiorespiratory arrest (CA). However, cardiac thrombus formation (TF) is likely to be the consequence of the forward blood flow ceasing during cardiac standstill. We present the case of a young man who was hospitalized for infective endocarditis, complicated by multiorgan disease and sudden CA on the 5th day. Prompt cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) warranted a return of spontaneous circulation in 16 min but, unexpectedly, a TF was recognized in the right atrium at echocardiography. The blood clot resolved with rapid administration of endovenous heparin and continued chest compressions. Even though cardiac ultrasound is not ready for a routine use during CPR, the present study confirms a key role in the management of CA patients.

Keywords: Cardiac arrest, cardiac thrombus, cardiopulmonary resuscitation, echocardiography, emergency ultrasound

INTRODUCTION

High-quality chest compression with minimal interruptions, defibrillation as soon as possible, ventilation support, and intensive postarrest care assistance are strong items to increase the chance of surviving sudden cardiorespiratory arrest (CA). Life-saving procedures by experts’ committees focus on both outside and inside the hospital management, remarking the need for high-quality chest compressions, especially during the early steps of cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) in all victims of CA, but some questions about current algorithms are open yet. Return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC) is established as the carotid pulse and/or the electrocardiography (ECG) signal reappears upon CPR. However, the need for an effective feedback on what is going on into the heart between CA and ROSC is a challenging issue for rescuers, albeit chest compressions are proficient.[1,2,3]

Early diagnosis of any reversible cause of CA is also emphasized by guidelines in order to establish suitable solutions for the victims. In this regard, point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS) has been proposed as a powerful tool for recognizing such mechanism (s), as well as distinguishing a true from a false asystole, but a stable role in the CPR procedures is still debating.[1,4,5,6,7]

Among the right heart diseases, deep venous thrombosis and intracardiac thrombosis are the most common sources of pulmonary embolism, at times leading to CA as pulmonary arteries are massively thrombosed.[1,2,8]

However, cardiac thrombus formation (TF) can also be the consequence of forward blood flow ceasing in patients with CA, and unawareness of this complication can undermine the efforts to ROSC.[9,10,11]

We present the case of a patient with endocarditis complicated by inhospital CA who developed right atrial TF during guideline-driven CPR. The role for POCUS-enhanced algorithms and therapeutic options for contrasting blood clots in cardiac standstill settings are discussed.

CASE REPORT

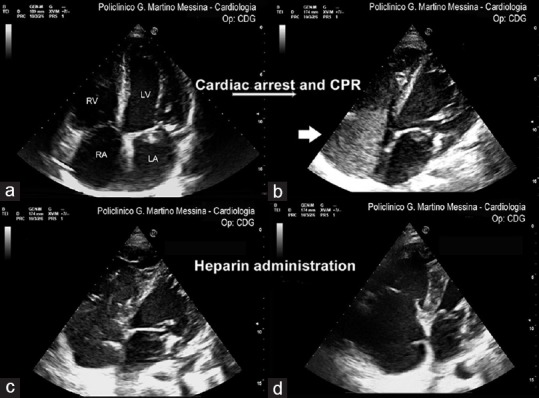

A 35-year-old male was admitted to our cardiology unit with a 15-day history of unremitting fever, chest and abdominal pain, and palpitation. Although the patient's vitals were stable, general conditions appeared critical. Unspecific ECG abnormalities were present at entry. Signs of endocarditis were disclosed at transthoracic echocardiography to involve both the aortic and mitral valve leaflets [Figure 1a].

Figure 1.

Ultrasound imaging of the heart during cardiopulmonary resuscitation in the patient. (a) four-chamber apical view at baseline, with endocarditis vegetation on the mitral valve leaflets. (b) right atrial and ventricular thrombus formation (arrow) following 16-min cardiopulmonary resuscitation with apparent ROSC. (c) first endovenous administration of heparin 5000 IU and continued chest compression. (d) blood clot disappearance after the second bolus of heparin. RA = right atrium, RV = right ventricle, LA = left atrium, LV = left ventricle

Optimal medical therapy was initiated in the cardiac care unit, with challenging clinical efficacy. He was established to be at a high risk for cardiac surgery due to multiorgan (pulmonic, kidney, and metabolic) failure from a septic condition. A daily echocardiographic examination was then scheduled.

However, on the 5th day, his clinical course complicated with CA. High-quality chest compressions and advanced cardiac life support procedures warranted a ROSC in 16 min. This allowed the rescuer performing further echocardiographic check for cardiac function. Unexpectedly, a large TF was seen in the right atrium [Figure 1b, movie]. The decision was made to administer rapid endovenous heparin (5000 + 5000 IU) and continued chest compressions until the thrombus disappeared [Figure 1c and d]. The patient was then moved to the intensive care department, but his prognosis remained poor.

DISCUSSION

This study demonstrates cardiac TF as a potential complication of CA in spite of standard CPR protocols. Although it occurred in such a difficult clinical setting, the case presented deserves some considerations.

Blood clots have been previously reported as a result of CA. In 2014, left ventricular TFs were described by Budhram et al.[10] soon after the induction of ventricular fibrillation in test patients. Approximately 90% of TFs formed in <6 min, in accordance with their in vivo clotting times (6–10 min). Blood clots dissolved soon after mechanical circulatory support, but the authors were unable to establish whether these really dissolved or (more likely, in their opinion) were disseminated into systemic circulation. Of interest, echocardiography was demonstrated to be a valuable diagnostic and prognostic tool.

It is undeniable that optimized chest compressions and prompt defibrillation for shockable rhythms are the pillars of CPR procedures in CA patients. However, the effective feedback of chest compressions’ efficacy remains challenging in most cases, being also dependent on several variables, first of all, chest conformation, underlining cardiac disease, and constancy of the rescuer(s) approach.[1,2,3,6] In fact, it is hard to establish whether chest compressions are powered enough to warrant a minimal bloodstream to the brain and the heart, especially in difficult clinical settings like in our patient.

Thinking of the Virchow's triad, the forward blood flow ceasing is the strongest mechanism of TF. Even if thrombolytic agents and heparin have been reported as the first-line therapy in event of massive pulmonary embolism, there are no indications about anticoagulant drug use in the course of routine CPR.[1,2,4,8]

Unfortunately, we could not identify the main cause of CA in our patient, but serial echocardiographic examinations performed everyday likely excluded a primary right heart thrombus. More likely, this was due to a blood sludge, which was seen as a strong echo contrast on ultrasound, quickly disappearing after endovenous heparin administration and continued chest compression. The septic syndrome surely played a key role for hypercoagulability in this patient, because infectious agents and their products can directly activate the coagulation cascade enzymatically and trigger platelet aggregation and pro-thrombotic responses, especially in the event of acidosis and tissue hypoperfusion.[9,12]

A similar case was demonstrated as a consequence of CA in a patient undergoing liver transplantation, successfully treated with heparin.[13]

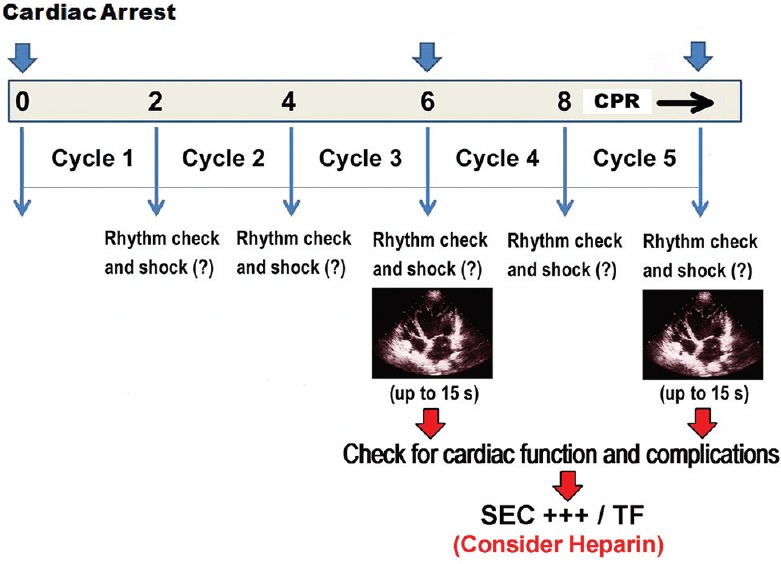

As hypothesized in Figure 2, patients experiencing inhospital CA may take advantage from intravenous heparin during prolonged CPR, at least in presence of prothrombotic conditions and marked spontaneous echo contrast forming within the right (or left) cardiac chambers, except for hemorrhagic-shocked individuals. As from recent literature, cardiac POCUS is the only technique to get effective feedback about a potential thrombogenic condition.[6,7,10,11,12,13,14]

Figure 2.

Proposal of ultrasound-implemented cardiopulmonary resuscitation algorithm in order to check for cardiac function and/or complications during forward blood flow ceasing in cardiorespiratory arrest (description in text). SEC+++ = marked spontaneous echo-contrast, TF = thrombus formation

Conversely, time loss is the most important limitation to a wider ultrasound use during CPR.[1,2,3] On the other hand, a good correlation between ROSC and serial echocardiographic examinations has been proven in CA patients admitted to emergency department. Fast-track examinations every 2 min upon the CPR timeline was found to predict ROSC in unshockable rhythm patients, with no significant time loss.[5,11]

Based on the current knowledge and present findings, we have hypothesized a fast cardiac ultrasound protocol by skilled operators, to be performed at least after 3–4 cycles (6–8 min) of chest compressions, using the pause for rhythm check (5–15 s) to quickly attain a four-chamber apical or subcostal view and assess both ventricular function and potential complications, like TF [Figure 2].

In conclusion, even though cardiac ultrasound has not been approved for a routine use during CPR for CA, recent studies and our experience suggest a key role in the management of such victims. Other than an early causative screening, cardiac POCUS is likely to provide important information about cardiac function and potential complications of prolonged forward blood flow ceasing.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form the patient(s) has/have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Olasveengen TM, de Caen AR, Mancini ME, Maconochie IK, Aickin R, Atkins DL, et al. 2017 international consensus on cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiovascular care science with treatment recommendations summary. Circulation. 2017;136:e424–40. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Soar J, Donnino MW, Maconochie I, Aickin R, Atkins DL, Andersen LW, et al. 2018 International consensus on cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiovascular care science with treatment recommendations summary. Circulation. 2018;138:e714–30. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Considine J, Gazmuri RJ, Perkins GD, Kudenchuk PJ, Olasveengen TM, Vaillancourt C, et al. Chest compression components (rate, depth, chest wall recoil and leaning): A scoping review. Resuscitation. 2019 doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2019.08.042. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2019.08.042. (in press) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.MacCarthy P, Worrall A, McCarthy G, Davies J. The use of transthoracic echocardiography to guide thrombolytic therapy during cardiac arrest due to massive pulmonary embolism. Emerg Med J. 2002;19:178–9. doi: 10.1136/emj.19.2.178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Flato UA, Paiva EF, Carballo MT, Buehler AM, Marco R, Timerman A, et al. Echocardiography for prognostication during the resuscitation of intensive care unit patients with non-shockable rhythm cardiac arrest. Resuscitation. 2015;92:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2015.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zengin S, Gümüşboǧa H, Sabak M, Eren ŞH, Altunbas G, Al B, et al. Comparison of manual pulse palpation, cardiac ultrasonography and doppler ultrasonography to check the pulse in cardiopulmonary arrest patients. Resuscitation. 2018;133:59–64. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2018.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Long B, Alerhand S, Maliel K, Koyfman A. Echocardiography in cardiac arrest: An emergency medicine review. Am J Emerg Med. 2018;36:488–93. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2017.12.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pedley DK, Morrison WG. Role of thrombolytic agents in cardiac arrest. Emerg Med J. 2006;23:747–52. doi: 10.1136/emj.2006.038067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Monie DD, DeLoughery EP. Pathogenesis of thrombosis: Cellular and pharmacogenetic contributions. Cardiovasc Diagn Ther. 2017;7:S291–8. doi: 10.21037/cdt.2017.09.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Budhram GR, Mader TJ, Lutfy L, Murman D, Almulhim A. Left ventricular thrombus development during ventricular fibrillation and resolution during resuscitation in a swine model of sudden cardiac arrest. Resuscitation. 2014;85:689–93. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2014.01.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim S, DeMaria S, Jr, Cohen E, Silvay G, Zerillo J. Prolonged intraoperative cardiac resuscitation complicated by intracardiac thrombus in a patient undergoing orthotopic liver transplantation. Semin Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2016;20:246–51. doi: 10.1177/1089253216652223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Morgan RW, Fitzgerald JC, Weiss SL, Nadkarni VM, Sutton RM, Berg RA, et al. Sepsis-associated in-hospital cardiac arrest: Epidemiology, pathophysiology, and potential therapies. J Crit Care. 2017;40:128–35. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2017.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim HB, Suh JY, Choi JH, Cho YS. Can serial focussed echocardiographic evaluation in life support (FEEL) predict resuscitation outcome or termination of resuscitation (TOR)? A pilot study. Resuscitation. 2016;101:21–6. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2016.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu RB, Bogucki S, Marcolini EG, Yu CY, Wira CR, Kalam S, et al. Guiding cardiopulmonary resuscitation with focused echocardiography: A report of five cases. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2019 doi: 10.1080/10903127.2019.1626955. doi: 10.1080/10903127.2019.1626955 (in press) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]