Abstract

Aim:

Multiple drug intolerance syndrome (MDIS) is a unique clinical entity distinct from other drug hypersensitivity syndromes. The aim of this review was to critically appraise the various aspects of MDIS.

Methods

A review was conducted to search for the causes, mechanism, clinical features, and management of MDIS.

Results

The most common cause of MDIS is antibiotics followed by non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). Although some non-specific immunological mechanisms are involved, the immunological tests for MDIS are negative. Rashes, gastrointestinal reflux, headache, cough, muscle ache, fever, dermatitis, hypertension, and psychiatric symptoms are the usual manifestations. Treatment is mostly symptomatic with the withdrawal of the offending drug. Drug re-challenges and desensitization may be required for the management of this syndrome.

Conclusion

MDIS occurs by a nonimmune mechanism which requires a prompt withdrawal of the offending drug(s), and in some cases may require drug re-challenge and desensitization.

Keywords: Multiple drug intolerance syndrome, antibiotics, hypersensitivity, immunological reactions, floctafenine, pyrazolones

1. INTRODUCTION

Drug hypersensitivity is a common public health problem. It affects 7% of the population [1]. About 30-40% of adverse drug reactions (ADRs) attribute to drug hypersensitivity [2]. Hypersensitivity to more than one drug is common. About one-third of patients attending an allergic clinic reported the same [3]. Multiple drug hypersensitive syndrome (MDH) or multiple drug allergic syndrome (MDAS), multiple drug intolerance syndrome (MDIS), cross reaction and flare-up reactions are some nomenclatures assigned to these reactions based on their characteristics. The MDIS is described as “a clinical entity characterized by adverse drug reactions to at least three chemically, pharmacologically and immunogenically unrelated drugs, manifested upon three different occasions, and with negative immunological (allergic) test(s)” [2-4]. The term MDAS was used for describing conditions where patients are hypersensitive to two or more chemically different drugs and who are positive for an immunological or allergy test(s) [3, 5]. This term was then revised to MDH [6]. The reactions to drugs with similar structures, common metabolic pathways or pharmacological mechanisms are the characteristics of a cross-reaction [7]. Flare-up reactions are an exacerbation of the existing hypersensitive reactions due to early switch of therapy to another drug [7]. Different nomenclatures have been assigned for MDIS to various drug classes. The term “multiple antibiotic sensitivity syndrome” (MASS) has been used for antibiotic-induced MDIS. Likewise, “multiple non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) sensitivity” (MNS) has been used for NSAID induced MDIS [8, 9].

The MDIS patients and their treating physicians are often scared. This is due to the past history of multiple reactions to different classes of drugs. They are often negative for the allergic test(s) [4]. They also believe that they are allergic to all drugs [4]. Although this is a public health problem, only a few published review articles are available on this particular syndrome. Thus, this important under-reported clinical entity needs a comprehensive discussion. In this narrative review, we present the prevalence, causative agents, risk factors, clinical features, diagnosis and management of MDIS.

2. EPIDEMIOLOGY

The prevalence of MDIS in the general population is around 2.1-10.05% in different countries [4, 10-13]. The prevalence is more common in females (6.1%) compared to males (2.9%) [11]. The median age of patients with MDIS varies from 57 to 68.3 years [4, 11, 13]. MDIS patients are heavier compared to normal healthy individuals [4]. The number of reactions per MDIS patient has been reported to be 4.95 with a range of 3-13 [2]. Table 1 summarizes the published studies involving MDIS from various databases [2, 4, 8, 10-15].

Table 1. Studies involving multiple drug intolerance syndrome (MDIS) patients.

|

Author/

Year of Publication |

Study Design | Place of Study | Criteria for MDIS |

Total

Number of Patients Studied |

Type of Studied

Population |

No. of MDIS Patients

Reported [Number (%)] |

Drug Allergy

Work-up |

Drugs

Involved |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antoniou et al., 2016 [10] |

Retrospective analysis | UK | Documented history (at referral or new patient visit) of intolerance to at least three unrelated classes of antihypertensive |

786 | Adult hypertensive patients | 79 (10.05%) | NR | Antihyper-tensives |

| Asero et al., 2002 [8] |

Prospective study | Italy | Patients with a history of MNS | 36 | Adult patients with multiple intolerances to NSAIDs |

22 (NR) | Autologous serum skin test (ASST) |

NSAIDs |

| Blumenthal et al., 2018 [13] |

Retrospective record based study | USA | Intolerances to ≥3 drug classes | 746,888 | Adult patients with documented drug allergy | 47,634 (6.4%) | NR | Multiple drug class |

| De Pasquale et al., 2012 [15] |

Prospective study | Italy | DHR to ≥3 unrelated drugs on 3 different occasion with negative allergy test | 30 | Adult female MDIS patients | 30 (NR) | Skin test, patch test, IgE titers | Multiple drug class |

| Macy et al., 2012 [4] |

Retrospective record based study | USA | Intolerance to 3 or more unrelated medications | 2,375,424 | Patients with documented drug allergy | 49,582 (2.1%) | NR | Multiple drug class |

| Okeahialam et al., 2017 [12] |

Retrospective record based study | Nigeria | Patients intolerant of three or more drugs with no clear immunological mechanism |

489 | Adult hypertensive patients attending follow up for BP control | 15 (3.06%) | NR | Anti- hypertensives |

| Omer et al., 2014 [11] |

Retrospective record based study | UK | Adverse drug reactions to three or more drugs without a known immunological mechanism | 25,695 | Adult patients with documented drug allergy | 1,250 (4.86%) | NR | Multiple drug class |

| Patriarca et al., 1991 [14] |

Prospective study | Italy | DHR to ≥3 unrelated drugs on 3 different occasion with negative allergy test | 20 | Adult female MDIS patients | 20 (NR) | Skin test, patch test, IgE titers | Multiple drug class |

| Schiavino et al., 2007 [2] |

Prospective study | Italy | DHR to ≥3 unrelated drugs on 3 different occasion with negative allergy test | 480 | Adult patients with history of adverse reactions to more than 3 drug | 480 (NR) | Skin test, patch test, IgE titers & serum ECP level | Multiple drug class |

ECP: Eosinophilic Cationic Protein; DHR: Drug Hypersensitivity Reactions; MNS: Multiple Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs) sensitivity; USA: Unites States of America; UK: United Kingdom; NR: Not reported.

3. DRUGS RESPONSIBLE FOR MDIS

The most common group of drugs causing MDIS is antibiotics followed by NSAIDs. Previous studies have mentioned MDIS in patients taking drugs from various therapeutic classes. These are drugs acting on the respiratory system, gastrointestinal, nervous, and cardiovascular system, corticosteroids, local and general anesthetics, iodinated contrast media, and vitamins [2, 4]. β-lactam antibiotics are the most common culprits for MDIS. However, the incidence of a particular antibiotic is lacking in the published literature. Aspirin, propionic acid, diclofenac, tolmetin, ketorolac, piroxicam, pyrazolones, morniflumate, paracetamol, nimesulide, floctafenine, and rofecoxib have been reported to be associated with MNS [8]. Morais-Almeida et al. have reported a case of multiple drug intolerances to etoricoxib and several other NSAIDs, such as aspirin, nimesulide, paracetamol, diclofenac, and tramadol. Finally, the patient tolerated niflumic acid at a cumulative dose of 125 mg [16]. About 10% of patients attending special blood pressure centers experience multiple drug reactions to antihypertensive drugs. This results in uncontrolled BP due to insufficient medication intake [10].

4. MECHANISMS UNDERLINING MDIS

The pathogenesis of MDIS is unknown. But, the occurrence this syndrome could be due to the following mechanisms:

Pseudo-allergic reactions due to mast cell mediator release, T-cell or Mrgprx mediated reactions. Mrgprx is a novel mast cell G-protein coupled receptor. It helps in mast cell degranulation in response to cationic drugs [6].

Serum autoantibodies target the immunoglobulin E (IgE) receptor (FceRI) inducing histamine release [11]. Serum of MDIS patients presents these autoantibodies.

Off-target actions of the drugs (side effects) [6].

Abnormal T-regulatory cell function [6].

5. CLINICAL FEATURES

The clinical features of this syndrome are rashes, gastrointestinal reflux, headache, cough, muscle ache, fever, dermatitis, and hypertension. Patients may have features of psychiatric illness, such as depression and anxiety [6, 15, 17]. Schiavino et al. reported most reactions related to skin. Severe reactions are rare in MDIS compared to immune-mediated reactions. This may be due to the non-immune mediated mechanism responsible for MDIS [2].

6. DIAGNOSIS

MDIS is a diagnosis of exclusion. There are no specific biomarker and confirmatory in-vitro test available to diagnose MDIS. Hence, a detailed history of previous drug reactions is essential for assessing risk factors. These risk factors are the intake of drugs causing MDIS, gender, the age of the patient, multiple co-morbidities or hospitalizations, frequent use of allergic and psychiatric services, spontaneous urticarial history, cross-tolerance to NSAIDs, severe anaphylaxis or cutaneous drug reaction, and presence of atopic diseases [6]. Drug-drug interactions also contribute towards MDIS. Schiavino et al. mentioned that the serum total IgE and eosinophil cationic protein in most of the MDIS patients were within the normal reference range. So, these tests are not of particular use in this condition [2]. Therefore, a general approach to exclude immune-mediated reactions can be followed after conducting skin tests, patch tests, and measurements of specific IgE level.

7. DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

The differential diagnoses of MDIS are MDAS or MDH, drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS) syndrome, cross reaction and flare-up reaction. Table 2 describes the differentiating features of these clinical entities [18, 19].

Table 2. Differential diagnosis of MDIS [18, 19].

| Clinical Features | MDIS | MDAS/MDH | DRESS | Cross Reactions | Flare up Reactions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of drugs involved | > 3 chemically different drugs | > 2 chemically different drugs |

One or more | One or more | Second reaction to the same drug |

| Duration of drug exposure before occurrence of reaction | < 1 hr in NSAIDs intolerance |

> 3 days | >10 days | Varies from drug to drug | 2 to 4 hours - 2 days |

| Expansion of drug induced T-cells |

UN | Days or weeks | Days or weeks | 2 -3 days | Only activation, no expansion |

| Main symptoms | Simple rashes to urticaria, anaphylaxis and bronchospasm |

Similar or different reactions to the first MDH | DRESS/ exanthema |

Cutaneous eruptions to severe hypersensitivity Syndrome |

Identical to the first reaction |

| Sensitization (skin tests/LTT) | No | Yes (≥ 2 drugs) | Yes | Yes | No |

| Persistence | Yes | Yes | No | Depends on amount of precursor T-cells |

No |

| Management | Start a drug from other class under supervision. Rechallenge or desensitization, when needed | Start a drug from other class under supervision. rechallenge or desensitization, when needed | Avoid drug causing DRESS. Start another drug from different class | Premedication with antihistamines and corticosteroids; start another drug from a structurally different class or rechallenge when needed | Start another drug |

DRESS: drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms, LTT: lymphocyte transformation test, MDAS: multiple drug allergic syndrome, MDH: multiple drug allergic syndrome, MDIS: multiple drug intolerance syndrome, NSAIDs: non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, UN: Unknown).

8. MANAGEMENT

8.1. General Considerations

A detailed medication history and the related symptoms are necessary for identifying the culprit drug. This should also be recorded for future management. The offending drugs should be avoided in the future. Alternative drugs should be prescribed after a successful tolerance challenge test (if required on a case to case basis). The drug challenge under close medical observation in an emergency setup is essential. These drug tolerance tests help in immediate intervention in case of emergency. This also boosts the patient’s confidence for the treatment [2].

Not only the patients but also treating physicians fear such drug reactions. Thus, their treating physicians often avoid prescribing drugs. But, these reactions are usually not very severe in nature [18]. Psychological components play an important role in this syndrome [2]. Psychological stress is more prevalent in elder females. Poly-pharmacy in elder age adds to this. So, the reduction of poly-pharmacy may help in decreasing the incidence of MDIS [4].

Peter J has mentioned that most of the patients can tolerate required medications after an appropriate evaluation [6]. Drug rechallenge is mandatory when there is no alternate option. An anticipation of a life-threatening reaction also needs drug rechallenge. Rechallenge can be dangerous and thus is not indicated in the patients with the following conditions. These are drug-induced toxic epidermal necrolysis, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, generalized bullous fixed drug eruption, acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP), severe hepatitis, nephritis, hemolytic anemia, severe anaphylaxis, drug-induced auto-immune diseases such as, systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), pemphigus vulgaris, bullous pemphigoid, etc., and particularly angioedema associated with use of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors [4, 20].

Appropriate skin test or in-vitro IgE measurements warrants for IgE-mediated reactions. Anaphylaxis, shortness of breath and hives are some examples of IgE mediated reactions. If the result of such tests is negative, rechallenge can be performed under close observation. In case of positive skin test or in-vitro test, the patients should be desensitized for one therapeutic course. For most of the mild ADRs, drug rechallenge performed under close observation is essential [21-24]. Maculopapular rash, fixed drug eruption, nausea, vomiting, gastrointestinal upset, diarrhea, and drug fever are some examples of mild ADRs.

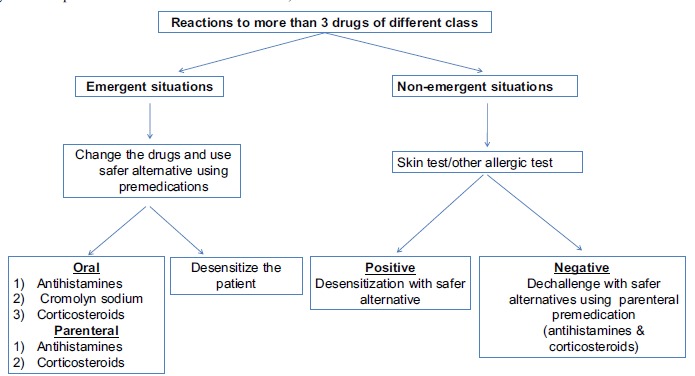

MDIS patients are more anxious, depressed and alexithymic compared to normal individuals. Thus, these patients need psychiatric evaluation. This also helps in increasing the tolerance to next drug administration. Besides this, it increases tolerance in patients who consider themselves intolerant to all the drugs [15]. Ramam et al. revealed that none of the patients qualified for having MDIS in an oral provocation test [23]. They also mentioned that these reactions were self-reported by the patients. They concluded that drug phobia rather than true allergic reactions may be the possible reason for such reactions. Fig. (1) describes the general guidelines for the management of MDIS.

Fig. (1).

9. ANTIBIOTIC-INDUCED MDIS

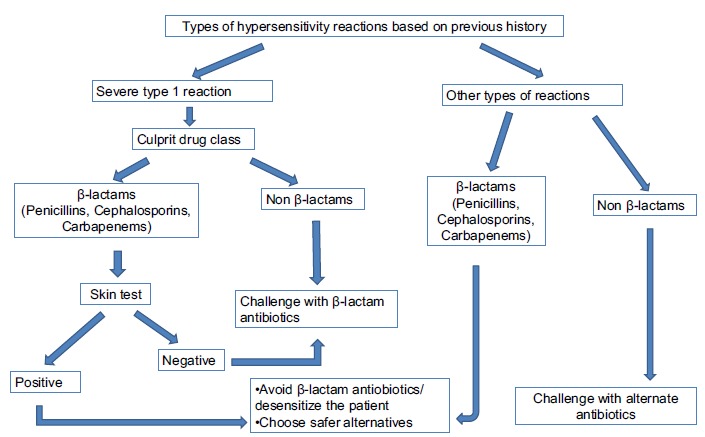

Overuse of antibiotics is one of the causes of antibiotic-induced MDIS [9]. The incidence of MDIS can be reduced by restricting the unnecessary use of antibiotics. MDIS to β-lactam antibiotics is common. Yet, these patients rarely develop serious drug reactions to other antibiotics [9]. Reactions to penicillins or cephalosporins with a previous history of urticarial rashes, pruritus, angioedema, bronchospasm, hypotension or arrhythmia warrant appropriate skin test before drug administration. If skin test result is negative, a challenge with penicillin or cephalosporin can be performed. But, in patients with a previous history of life-threatening reactions, a graded challenge with low starting dose should be performed under supervision. When the skin test result is positive, the use of β-lactam antibiotics should be avoided. Rather, desensitization should be performed in an emergency setup [9]. Patients with a history of other types of reactions can be challenged with penicillin, cephalosporin or carbapenem except for first-generation cephalosporin and cefamandole. Desensitization is needed for patients having the previous history of reactions to antibiotics other than β-lactam antibiotics if skin test is positive. In the case of negative skin test, drug challenge can be performed. Anti-histamines can be administered for non-urticarial rashes [9]. The general approach to the management of MDIS related to antibiotics is shown in Fig. (2). Schiavino et al. suggested the use of sodium cromolyn for the prevention of non-allergic hypersensitive reactions. Sodium cromolyn stabilizes the lysosomal membrane of mast cells and basophils. Stabilization of lysosomal membrane prevents degranulation of these cells [2]. Prophylactic use of oral anti-histamines was found to be successful in 89% of patients. Anti-histamines prevents degranulation of mast cells and basophils. Antileukotrienes can also be considered for this condition [25].

Fig. (2).

10. NSAIDS-INDUCED MDIS (MNS)

Schiavino et al. mentioned the drugs responsible for NSAIDs-induced MDIS. They also reported nimesulide and acetaminophen are the most tolerated NSAIDs. This is because of their poor of cyclooxygenase (COX) inhibitory activity [2]. In case of any adverse reactions to these drugs, selective COX-2 inhibitors should be taken into consideration. The reasons for preferring non-selective COX inhibitors over COX-2 inhibitors as described by Asero R [26] are:

To establish the sensitivity to one or multiple NSAIDs,

Long-term use of COX-2 inhibitors is associated with fatal cardiovascular adverse effects, and

The analgesic and anti-inflammatory potency of the nimesulide, paracetamol, and meloxicam are inferior compared to non-selective NSAIDs.

Oral tolerance or provocation tests with incremental doses until the therapeutic dose can be carried out. Generally, the patients need two doses (1/4th and 3/4th of a therapeutic dose) at a one-hour interval. This is considered safe, convenient, and sensitive for the detection of multiple intolerances to NSAIDs [27, 28]. But, the patients should be observed for at least 1.5 hours after the last dose administration [29]. This is the time limit for the occurrence of most of the adverse drug reactions [29]. For patients with an aspirin-exacerbated respiratory disease, desensitization is recommended [30]. But, in the case of intolerance to multiple NSAIDs, rechallenge is recommended with NSAID with minimum or no COX-1 inhibitory action such as nimesulide, celecoxib, valdecoxib, and paracetamol). Schiavino et al. used premedication with sodium cromolyn, antihistamines, or corticosteroids, alone or in combination. They also followed the desensitization procedures for some MDIS patients [2].

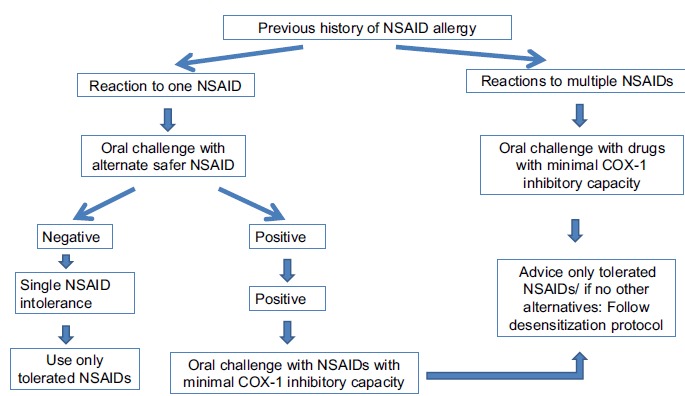

Asero R in 2007 warned to use drug provocation test for diagnosing NSAID-induced MDIS. The rechallenge test may cause a severe life-threatening reaction. Thus, a chemically distinct, alternative drug with similar efficacy can be substituted [26]. About 24% of patients who were intolerant to single NSAID other than aspirin did not tolerate aspirin. 18% of subjects also did not tolerate NSAIDs with minimum or no COX-1 inhibitory activity on subsequent oral challenges [27]. He further mentioned that 60% of patients with acute urticaria induced by aspirin did not tolerate ketoprofen. 37% of the ketoprofen intolerant patients also did not tolerate nimesulide [28]. Aspirin and ketoprofen were chosen for rechallenge in these studies based on their COX-1 inhibitory property [31]. A tolerance test with a chemically distinct COX-1 inhibitor can be used in a patient with a history of urticaria or angioedema caused by a single COX-1 inhibitor (e.g., diclofenac, piroxicam, naproxen, aspirin) [32]. Patients with aspirin-induced acute urticaria developed more multiple NSAID intolerance compared to patients with a history of urticaria induced by other NSAID (60% vs 24%) [32]. Asero R also observed similar findings in his study. He reported that NSAID intolerant patients with a history of aspirin-induced urticaria are more prone to develop chronic urticaria than patients without the same history [26]. Patients with a previous history of multiple NSAIDs intolerance, with or without underlying chronic urticaria can undergo oral tolerance test with drugs exerting little or no COX-1 inhibition [27]. The schematic diagram for the management of MNS is shown in Fig. (3).

Fig. (3).

11. ANTI-HYPERTENSIVE DRUG-INDUCED MDIS

In a previous study, 10% of hypertensive patients attending specialist blood pressure center developed multiple intolerances to antihypertensive medications. This also resulted in inadequate drug therapy [10]. The authors used Bart algorithm for managing these patients. The algorithm was based on the drug administration in various dosage forms in a step-wise manner based on patient preference [10].

12. ANTIARRHYTHMIC INDUCED MDIS

Yager et al. used phenytoin as an alternative to antiarrhythmic drugs in patients with multiple drug intolerances for treating ventricular tachycardia [33].

CONCLUSION

Multiple drug intolerance syndrome (MDIS) is a distinct clinical entity. Antibiotics and NSAIDs are the most common culprits for MDIS. Rashes, gastrointestinal reflux, headache, cough, muscle ache, fever, dermatitis, hypertension, and occasional psychiatric symptoms are the usual manifestations of this syndrome. The offending drug(s) need(s) prompt withdrawal. Safer alternative(s) from a structurally different class should be administered. Drug rechallenge and desensitization play a major in the management of this syndrome.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Declared none.

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

Not applicable.

FUNDING

None.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest, financial or otherwise.

REFERENCES

- 1.Demoly P., Adkinson N.F., Brockow K., et al. International Consensus on drug allergy. Allergy. 2014;69(4):420–437. doi: 10.1111/all.12350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schiavino D., Nucera E., Roncallo C., et al. Multiple-drug intolerance syndrome: clinical findings and usefulness of challenge tests. Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2007;99(2):136–142. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)60637-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chiriac A.M., Demoly P. Multiple drug hypersensitivity syndrome. Curr. Opin. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2013;13(4):323–329. doi: 10.1097/ACI.0b013e3283630c36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Macy E., Ho N.J. Multiple drug intolerance syndrome: prevalence, clinical characteristics, and management. Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2012;108(2):88–93. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2011.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sullivan T. Studies of the multiple drug allergy syndrome. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 1989;83:270. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Peter J. Multiple-drug intolerance syndrome. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2016;29:152–156. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pichler W.J., Daubner B., Kawabata T. Drug hypersensitivity: flare-up reactions, cross-reactivity and multiple drug hypersensitivity. J. Dermatol. 2011;38(3):216–221. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.2010.01142.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Asero R., Tedeschi A., Lorini M. Autoreactivity is highly prevalent in patients with multiple intolerances to NSAIDs. Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2002;88(5):468–472. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)62384-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Robinson J.L., Hameed T., Carr S. Practical aspects of choosing an antibiotic for patients with a reported allergy to an antibiotic. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2002;35(1):26–31. doi: 10.1086/340740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Antoniou S., Saxena M., Hamedi N., et al. Management of hypertensive patients with multiple drug intolerances: A single-center experience of a novel treatment algorithm. J. Clin. Hypertens. (Greenwich) 2016;18(2):129–138. doi: 10.1111/jch.12637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Omer H.M.R.B., Hodson J., Thomas S.K., Coleman J.J. Multiple drug intolerance syndrome: a large-scale retrospective study. Drug Saf. 2014;37(12):1037–1045. doi: 10.1007/s40264-014-0236-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Okeahialam B.N. Multidrug intolerance in the treatment of hypertension: result from an audit of a specialized hypertension service. Ther. Adv. Drug Saf. 2017;8(8):253–258. doi: 10.1177/2042098617705625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Blumenthal K.G., Li Y., Acker W.W., et al. Multiple drug intolerance syndrome and multiple drug allergy syndrome: Epidemiology and associations with anxiety and depression. Allergy. 2018;73(10):2012–2023. doi: 10.1111/all.13440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Patriarca G., Schiavino D., Nucera E., Colamonico P., Montesarchio G., Saraceni C. Multiple drug intolerance: allergological and psychological findings. J. Investig. Allergol. Clin. Immunol. 1991;1(2):138–144. [PMID: 1669570]. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.De Pasquale T., Nucera E., Boccascino R., et al. Allergy and psychologic evaluations of patients with multiple drug intolerance syndrome. Intern. Emerg. Med. 2012;7(1):41–47. doi: 10.1007/s11739-011-0510-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Morais-Almeida M., Marinho S., Rosa S., Gaspar A., Rosado-Pinto J.E. Multiple drug intolerance including etoricoxib. Allergy. 2006;61(1):144–145. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2005.00878.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pichler W.J., Srinoulprasert Y., Yun J., Hausmann O. Multiple drug hypersensitivity. Int. Arch. Allergy Immunol. 2017;172(3):129–138. doi: 10.1159/000458725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Asero R., Tedeschi A., Lorini M., Caldironi G., Barocci F. Sera from patients with multiple drug allergy syndrome contain circulating histamine-releasing factors. Int. Arch. Allergy Immunol. 2003;131(3):195–200. doi: 10.1159/000071486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Romano A., Guéant-Rodriguez R-M., Viola M., Gaeta F., Caruso C., Guéant J-L. Cross-reactivity among drugs: clinical problems. Toxicology. 2005;209(2):169–179. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2004.12.016. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.tox.2004.12.016]. [PMID: 15767031]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aberer W., Bircher A., Romano A., et al. Drug provocation testing in the diagnosis of drug hypersensitivity reactions: general considerations. Allergy. 2003;58(9):854–863. doi: 10.1034/j.1398-9995.2003.00279.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gangemi S., Guarneri C., Romeo P., Guarneri F. Safety and reliability of the drug tolerance test: our experience in 739 patients. Pharmacology. 2011;87(1-2):90–95. doi: 10.1159/000323227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1398-9995.2011

- 23.Ramam M., Bhat R., Jindal S., et al. Patient-reported multiple drug reactions: clinical profile and results of challenge testing. Indian J. Dermatol. Venereol. Leprol. 2010;76(4):382–386. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.66587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nettis E., Colanardi M.C., Paola R.D., Ferrannini A., Tursi A. Tolerance test in patients with multiple drug allergy syndrome. Immunopharmacol. Immunotoxicol. 2001;23(4):617–626. doi: 10.1081/IPH-100108607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.White A., Ludington E., Mehra P., Stevenson D.D., Simon R.A. Effect of leukotriene modifier drugs on the safety of oral aspirin challenges. Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2006;97(5):688–693. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)61101-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Asero R. Clinical management of adult patients with a history of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug-induced urticaria/angioedema: update. Allergy Asthma Clin. Immunol. 2007;3(1):24–30. doi: 10.1186/1710-1492-3-1-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Asero R. Oral aspirin challenges in patients with a history of intolerance to single non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Clin. Exp. Allergy. 2005;35(6):713–716. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2005.2228.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Asero R. Use of ketoprofen oral challenges to detect cross-reactors among patients with a history of aspirin-induced urticaria. Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2006;97(2):187–189. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)60011-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cormican L.J., Farooque S., Altmann D.R., Lee T.H. Improvements in an oral aspirin challenge protocol for the diagnosis of aspirin hypersensitivity. Clin. Exp. Allergy. 2005;35(6):717–722. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2005.02261.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Macy E., Bernstein J.A., Castells M.C., et al. Aspirin challenge and desensitization for aspirin-exacerbated respiratory disease: a practice paper. Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2007;98(2):172–174. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)60692-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Warner T.D., Giuliano F., Vojnovic I., Bukasa A., Mitchell J.A., Vane J.R. Nonsteroid drug selectivities for cyclo-oxygenase-1 rather than cyclo-oxygenase-2 are associated with human gastrointestinal toxicity: a full in vitro analysis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1999;96(13):7563–7568. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.13.7563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Asero R. Intolerance to nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs might precede by years the onset of chronic urticaria. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2003;111(5):1095–1098. doi: 10.1067/mai.2003.1444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yager N, Wang K, Keshwani N, Torosoff M. Phenytoin as an effective treatment for polymorphic ventricular tachycardia due to QT prolongation in a patient with multiple drug intolerances. Case Rep 2015; 2015bcr2015209521. 2015 doi: 10.1136/bcr-2015-209521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]