Abstract

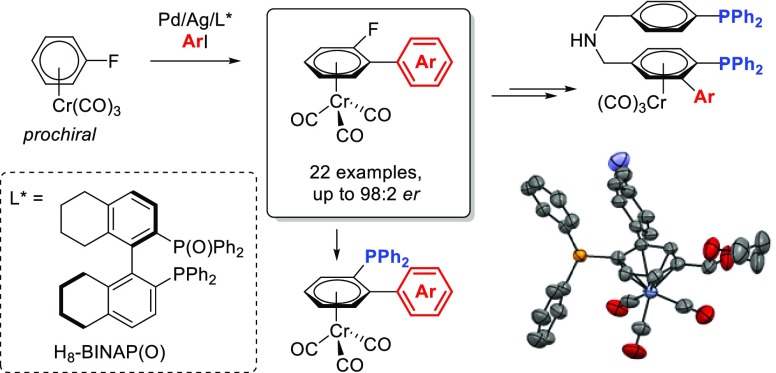

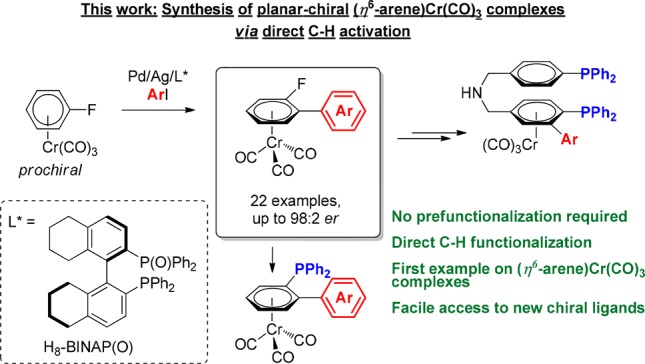

A catalytic asymmetric direct C–H arylation of (η6-arene)chromium complexes to obtain planar-chiral compounds is reported. The use of the hemilabile ligand H8-BINAP(O) is key to providing high enantioselectivity in this transformation. We show that this methodology opens the door to the synthesis of a variety of planar-chiral chromium derivatives which can be easily transformed into planar chiral mono- or diphosphines. Mechanistic studies, including synthesis and characterization of Pd and Ag complexes and their detection in the reaction mixture, suggest a Pd-catalyzed/Ag-promoted catalytic system where Ag carries out the C–H activation step.

Keywords: asymmetric catalysis, C−H activation, (arene)-chromium complexes, planar-chirality, chiral ligands

1. Introduction

Unsymmetrically substituted metallocenes and (η6-arene)chromium complexes are two notable families of planar-chiral transition-metal organometallic complexes, and they have extensively been applied as stoichiometric auxiliaries and/or starting materials for asymmetric synthesis of biologically interesting substances.1,2 Derivatives of ferrocene have been extensively investigated as optically active ligands in catalysis.3 In contrast, the use of (arene)chromium complexes as chiral ligands has been significantly less explored with only a small selection of such ligands reported to date (Figure 1). In spite of this, a variety of (arene)Cr(CO)3-based chiral ligands have been successfully used in asymmetric C–C bond formation reactions, such as cross-coupling reactions,4 addition of dialkylzinc to benzaldehyde,5 1,4-additions to Michael acceptors,5,6 hydrovinylations,7 1,2-additions of phenylboroxines to imines6 and nucleophilic substitutions.6b,8 Such ligands have also been employed in asymmetric reductions,8b,9 hydroaminations,8b hydroborations,10 and hydrosilylations.11

Figure 1.

Representative (η6-arene)Cr(CO)3 complexes used as planar-chiral ligands in asymmetric catalysis.

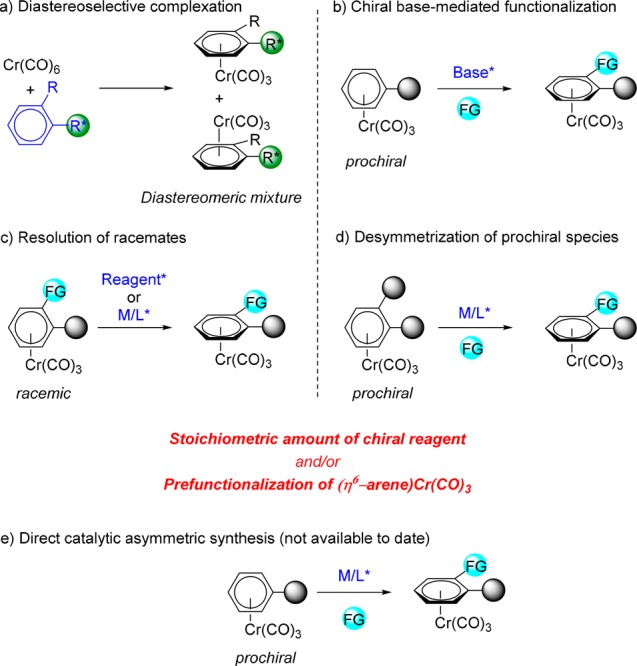

Formation of optically active (arene)chromium species is usually accomplished by means of either resolution of racemates,12 or asymmetric synthesis via diastereoselective complexation,13 diastereo- or enantioselective deprotonation/electrophile quenching,14 and nucleophilic addition/hydride abstraction sequences15 (Scheme 1a–c). All these methods employ stoichiometric chiral reagents or auxiliaries. Additionally, many of these processes are hampered by the use of sensitive organometallic reagents, poor functional group compatibility, and/or low atom economy. Conversely, the more attractive access to nonracemic (arene)chromium complexes via asymmetric catalysis has been significantly less explored. Uemura first reported the desymmetrization of o-dichlorobenzene chromium tricarbonyl complexes via asymmetric Pd-catalyzed cross-coupling with various vinylic metals.16 Subsequently, several examples of desymmetrization of suitably difunctionalized (arene)chromium complexes have been reported, including methoxycarbonylation17 or hydrogenolysis of haloarene-chromium derivatives,18 intramolecular Mizoroki-Heck reactions,19 gold-catalyzed intramolecular nucleophilic additions20 and Mo-catalyzed kinetic resolution6a (Scheme 1d). In all of these cases, prefunctionalization of the η6-complexed arene is required. In contrast, a catalytic asymmetric approach to planar-chiral (arene)chromium complexes from nonprefunctionalized starting materials has never been reported (Scheme 1e).

Scheme 1. Synthesis of Planar-Chiral (Arene)Cr(CO)3 Complexes.

While transition-metal catalyzed asymmetric C–H functionalization faces the challenge of discriminating between “inert” enantiotopic C–H bonds, it provides a straightforward approach for the preparation of chiral molecules.21 Several strategies have been developed to introduce central- and axial-chirality by enantioselective C–H bond activation.22 However, the use of asymmetric C–H bond functionalization for the creation of planar chirality has been relatively underexplored and limited exclusively to ferrocenes.23 These methods all rely on the formation of a chiral metallacyclic intermediate via an intramolecularly directed C–H activation.24,25 Thus, they are limited to substrates with suitable directing groups, reducing the generality and applicability of the process. To the best of our knowledge, there are no methods reported to synthesize enantioenriched planar-chiral chromium tricarbonyl complexes from unfunctionalized precursors in a catalytic fashion. In this paper, we report the first catalytic direct asymmetric C–H arylation of simple prochiral (η6-fluoroarene)chromium complexes (Scheme 2). In addition, we demonstrate that the enantioenriched products can be easily converted into planar-chiral phosphines providing access to an array of novel (arene)chromium-based chiral phosphine ligands.

Scheme 2. Synthesis of Planar-Chiral (Arene)Cr(CO)3 Complexes via C–H Activation.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Optimization of the Conditions of the Direct Asymmetric C–H Arylation

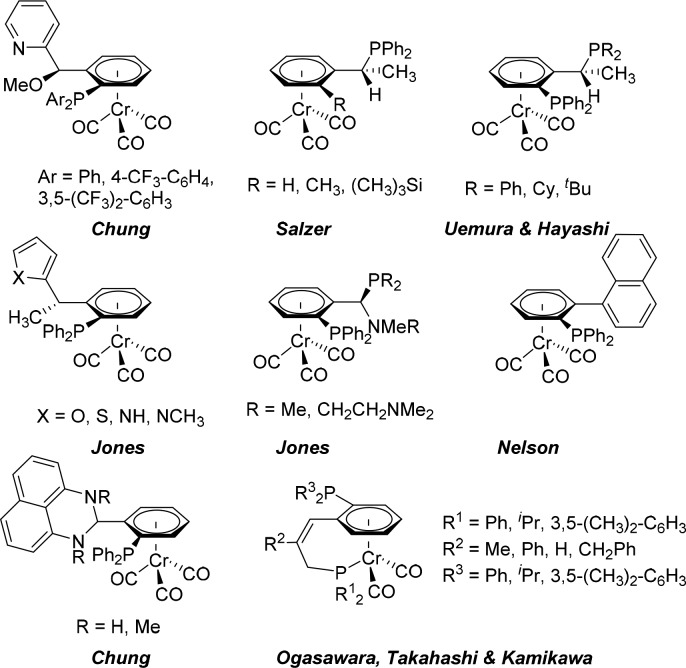

We have recently demonstrated that (fluoroarene)Cr(CO)3 complexes such as 1a can undergo Pd-catalyzed/Ag-mediated direct arylation affording excellent yields of ortho-substituted biaryls with high regioselectivity.26 A combination of stoichiometric and kinetic mechanistic studies showed that PPh3 ligated Ag(I)-carboxylates are responsible for the C–H activation step.27 With this in mind, we envisaged that the process could be rendered asymmetric in the presence of a chiral phosphine ligand suitable for distinguishing between the two enantiotopic C–H bonds of a prochiral complex. Furthermore, the presence of a C–F bond in the aromatic core should allow for the subsequent easy transformation of the resulting products into chiral arylphosphine derivatives via phosphination.28

We started our investigation testing similar conditions to those reported for the (nonasymmetric) ortho-arylation of (fluorobenzene)Cr(CO)3 (1a) complexes26a as a benchmark for reactivity. Under these conditions good reactivity was observed with 41% of racemic monoarylated product 3aa and 31% of bisarylated 4aa formed (Table 1, entry 1). We then replaced Pd(PPh3)4 with Pd(dba)2 and (S)-BINAP (L1), but under these conditions no reactivity was observed (entry 2). We had previously observed that the use of the highly hindered amine TMP (2,2,6,6-tetramethylpiperidine) as an additive enhances the reactivity of η6-coordinated arenes toward C–H arylation.29 Gratifyingly, the use of this additive promoted the reaction, forming monoarylated chromium complex 3aa in 28% yield and a low but promising enantioselectivity (38:62 er) (entry 3). A screen of Pd(II) sources revealed that Pd(CH3CN)4(BF4)2 gave similar yield to Pd(dba)2 with a slightly higher enantiomeric ratio (entry 4). Given that the carboxylic acid is involved in the C–H activation step, we expected the enantioselectivity of the process to be heavily influenced by the nature of the carboxylate. Indeed, carboxylic acid screening showed that dicyclohexylacetic acid enhanced both the reactivity and, importantly, the enantioselectivity (er: 18:82–16:84, entries 5 and 6). Conversely, reaction in the absence of the carboxylic acid gave a low yield of arylation and the enantiomeric ratio dropped to 55:45 (entry 7). Reactivity was completely shut down in the absence of silver carbonate (entry 8), whereas in the absence of K2CO3 a slightly lower yield and enantioselectivity were obtained (entry 9).30 Unreacted starting material was observed in all reactions. In some cases, free arene(s) was detected due to decomplexation of starting material and/or product and/or bisarylated byproduct.

Table 1. Optimization of the Asymmetric C–H Arylation of Complex 1a with 2a.

| Entry | Conditions | Yield 3aa (%)a | er3aab | Yield 4aa (%)a |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1c | Pd(PPh3)4, 1-AdCO2H | 41 | – | 31 |

| 2 | Pd(dba)2, 1-AdCO2H | 0 | – | 0 |

| 3 | Pd(dba)2, 1-AdCO2H, 2 equiv TMP | 28 | 38:62 | 9 |

| 4 | Pd(CH3CN)4(BF4)2, 1-AdCO2H, 2 equiv TMP | 28 | 36:64 | 7 |

| 5 | Pd(CH3CN)4(BF4)2, Cy2CHCO2H, 2 equiv TMP | 39 | 18:82 | 33 |

| 6d | Pd(CH3CN)4(BF4)2, Cy2CHCO2H, 2 equiv TMP | 43 | 16:84 | 39 |

| 7d | Pd(CH3CN)4(BF4)2, 2 equiv TMP | 24 | 55:45 | 2 |

| 8d,e | Pd(CH3CN)4(BF4)2, Cy2CHCO2H, 2 equiv TMP | 0 | – | 0 |

| 9d,f | Pd(CH3CN)4(BF4)2, Cy2CHCO2H, 2 equiv TMP | 40 | 19:81 | 27 |

Determined by 1H NMR spectroscopy using 1,3,5-trimethoxybenzene as internal standard.

Determined by HPLC (Chiralpak IB hexane/isopropyl alcohol).

Reaction carried out without L1.

Reactions carried out with 2 equiv of ArI.

Reaction carried out without Ag2CO3.

Reaction carried out without K2CO3.

We then set out to explore a variety of chiral ligands (Table 2). In comparison with BINAP (L1), the more sterically hindered 3,5-xylyl-BINAP (L2) gave a similar arylation yield but significantly lower enantioselectivity (Table 2, entries 1 and 2). On exploring the effect of the bite angle, we found that SegPhos (L3), with its smaller bite angle than L1, decreased the enantiomeric ratio while keeping similar reactivity; DIOP (L4), which has a larger bite angle than L1, also gave very low enantioselectivity (entries 3 and 4), suggesting that bite angles similar to that of L1 were ideal for this transformation. Good conversion but low er was observed when the monophosphine MeO-MOP (L5) was used (entry 5). Phosphoramidite MonoPhos (L6) and the P,N-ligand PPFA (L7) both completely inhibited the reaction (entries 6 and 7), while H8-BINAP (L8) led to similar reactivity to its unsaturated counterpart BINAP (L1) but with slightly higher er (entry 8). Finally, we tested BINAP(O) (L9), a ligand that has been rarely used in asymmetric catalysis,31 which contains both a strong and a weak donor atom, providing it the ability to act as a di- or monodentate ligand. Interestingly, in the presence of this hemilabile ligand, the yield and enantioselectivity of the process increased up to 47% and 14:86 er, respectively (entry 9).

Table 2. Screening of Chiral Ligands in the Asymmetric C−H Arylation of Complex 1a with 2a.

| Entry | Ligand | Yield 3aa (%)a | er3aab | Yield 4aa (%)a |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | (S)-L1 | 42 | 18:82 | 31 |

| 2 | (S)-L2 | 40 | 32:68 | 26 |

| 3 | (S)-L3 | 45 | 25:75 | 28 |

| 4 | (R,R)-L4 | 39 | 51:49 | 29 |

| 5 | (S)-L5 | 46 | 46:54 | 34 |

| 6 | (S)-L6c | 0 | – | 0 |

| 7 | (S,Sp)-L7c | 0 | – | 0 |

| 8 | (S)-L8 | 40 | 16:84 | 31 |

| 9 | (S)-L9 | 47 | 14:86 | 25 |

Determined by 1H NMR spectroscopy using 1,3,5-trimethoxybenzene as internal standard.

Determined by HPLC (Chiralpak IB hexane/isopropyl alcohol).

Reactions carried out with 10 mol % of ligand.

2.2. Synthesis and Reactivity of H8-BINAP(O) and H8-BINAP Derivatives

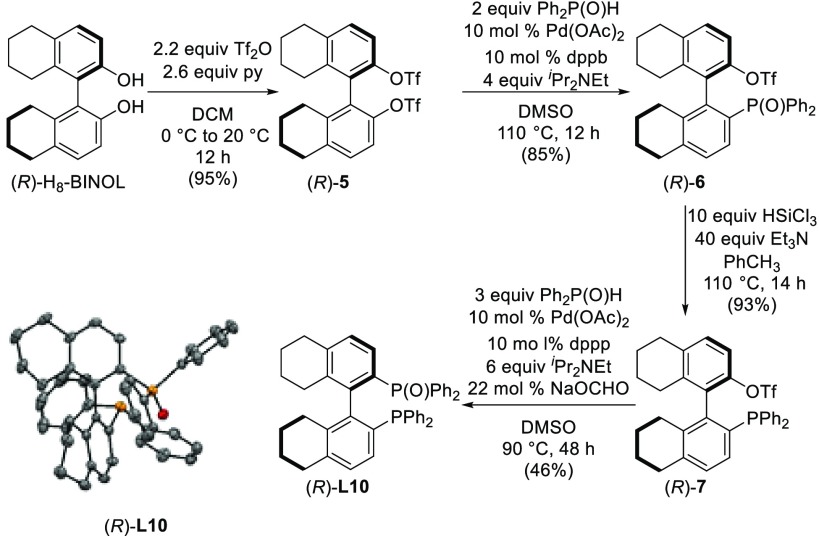

As the best results of reactivity and selectivity were found when H8-BINAP (L8) and BINAP(O) (L9) were used as chiral ligands, we decided to synthesize H8-BINAP(O) and other partially hydrogenated BINAP variants to test them as chiral ligands in the C–H asymmetric arylation of chromium complexes.

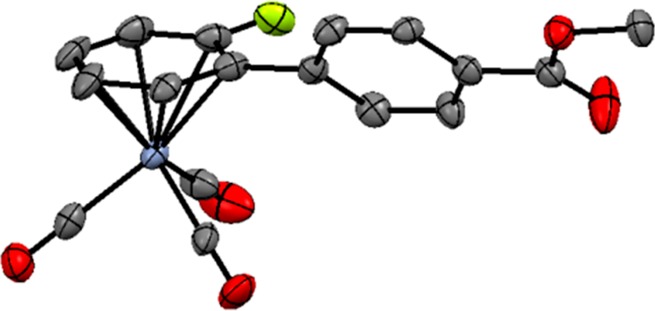

(R)-(2′-(Diphenylphosphanyl)-5,5′,6,6′,7,7′,8,8′-octahydro-[1,1′-binaphthalen]-2-yl)diphenylphosphine oxide ((R)-H8-BINAP(O), (R)-L10)32 was prepared in four steps following a methodology similar to that used for the synthesis of its unsaturated analogue BINAP(O) (Scheme 3).33 The preparation of (R)-L10 from commercially available (R)-H8-BINOL was accomplished by sequential substitution of the homotopic triflate groups of (R)-5 by diphenylphosphine oxide.34,35 The absolute configuration of the final product (R)-L10 was confirmed by X-ray diffraction analysis (Scheme 3). With the aim of investigating the influence on the modification of electronic and steric properties of the H8-BINAP(O) ligand on the reactivity and enantioselectivity of the reaction, we synthesized a range of H8-BINAP derivatives (L11–L18) following similar experimental procedures to those reported for their BINAP analogues (see Supporting Information).36

Scheme 3. Synthesis and ORTEP Plot of (R)-H8-BINAP(O) Ligand (R)-L10.

All hydrogen atoms are omitted for clarity.

Gratifyingly, when H8-BINAP(O) (L10) was tested as the ligand, high reactivity and enantioselectivity were observed for the arylation of 1a (Table 3, entry 1). We then tested ligands in which the weaker donor atom of the mono-oxidized H8-BINAP(O) was substituted by different functional groups. When the chiral ligand contained an ester group (L11) reactivity decreased while the product obtained was almost racemic (entry 2). A similar result was observed with a ligand bearing an alcohol substituent (L12) (entry 3). Interestingly, the more coordinating amide-derivative (L13) yielded 37% of product 3aa with a moderate 27:73 er (entry 4). These results demonstrate that the oxidized phosphine is essential to achieve high enantioselectivity. To evaluate the influence of the phosphine fragment, we tested the bis-oxidized H8-BINAP ligand (L14). This led to a racemic product in similar yield to that obtained in the absence of chiral ligand (29% of 3aa and 12% of 4aa), indicating that the phosphine moiety is necessary for coordination to the metal center. Once we had established that the combination of phosphine–phosphine oxide is the most adequate for achieving high reactivity and enantioselectivity, we decided to investigate the influence of the substituents in both of these groups. A ligand containing the P(O)(4-methoxyphenyl)2 fragment (L15) gave analogous results to H8-BINAP(O) ligand (L10) in terms of both reactivity and er (entry 6). However, when the phenyl groups were replaced by 3,5-dimethylphenyl groups (L16), both reactivity and enantioselectivity decreased (entry 7). The same scenario, but with even lower er, was observed when the aryl groups of the oxidized phosphine were replaced by alkylic cyclopentyl fragments (L17) (entry 8). Finally, replacing the phenyl groups in the PPh2 fragment with the more electron-donating 4-methoxyphenyl substituents (L18), led to only a moderate enantiomeric ratio (entry 9).

Table 3. Screening of H8-BINAP Derivatives in the Asymmetric C–H Arylation of Complex 1a with 2a.

| Entry | Ligand | Yield 3aa (%)a | er3aab | Yield 4aa (%)a |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | (S)-L10 | 42 | 7:93 | 27 |

| 2 | (S)-L11 | 33 | 46:54 | 16 |

| 3 | (S)-L12 | 27 | 46:54 | 7 |

| 4 | (S)-L13 | 37 | 27:73 | 22 |

| 5 | (S)-L14 | 33 | 50:50 | 19 |

| 6 | (S)-L15 | 46 | 10:90 | 24 |

| 7 | (S)-L16 | 37 | 20:80 | 20 |

| 8 | (S)-L17 | 37 | 27:73 | 22 |

| 9 | (S)-L18 | 40 | 18:82 | 22 |

Determined by 1H NMR spectroscopy using 1,3,5-trimethoxybenzene as internal standard.

Determined by HPLC (Chiralpak IB hexane/isopropyl alcohol).

2.3. Enantioselective C–H Activation of (η6-Fluoroarene)Cr(CO)3 Complexes

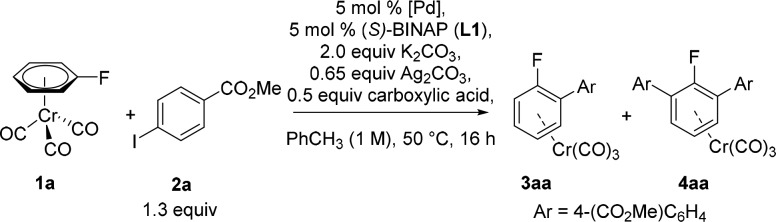

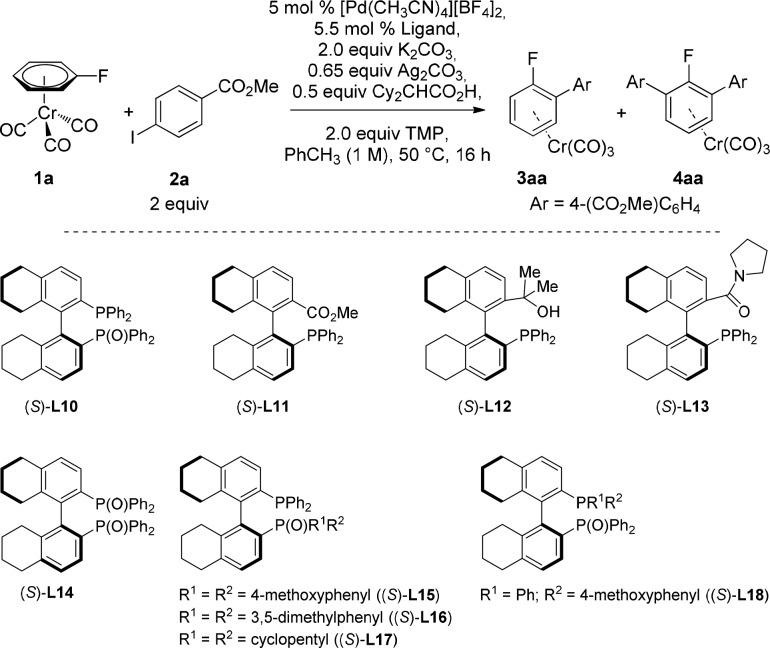

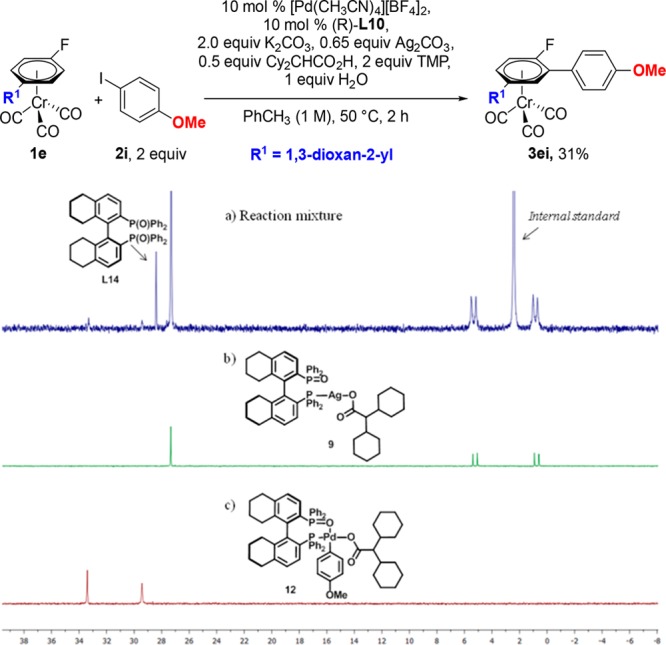

With the optimized conditions for the asymmetric arylation reaction, we set out to explore the generality of the methodology with respect to the fluoroarene chromium complex (Scheme 4a). Unsubstituted fluoroarene chromium derivatives showed good reactivity and er (3aa,ab). The presence of a methyl substituent on the fluoroarene did not produce a significant difference in terms of yield or enantiomeric ratio (3bb); however, when the substituent was an ester or a methoxy group a slight decrease in the enantiomeric ratio was observed (3cb,db). Interestingly, when the fluoroarene core contains a masked aldehyde in the form of a 1,3-dioxane group, the enantioenriched product was obtained in a 97:3 enantiomeric ratio (3eb). Different protecting groups for the aldehyde gave similar results of yield and enantioselectivity to 1,3-dioxane (3fb,gb,fc). The absolute configuration of the planar-chiral products could be unambiguously confirmed by X-ray diffraction analysis of a monocrystal of enantioenriched 3aa, showing that when (R)-L10 is used as a chiral ligand, the major isomer obtained is (Sp)-3aa (Figure 2)

Scheme 4. Scope of the Asymmetric Arylation of (Fluoroarene)Cr(CO)31a–g with Iodoarenes 2a–q,,

Reactions performed at 0.1 mmol scale.

er determined by chiral HPLC.

Isolated yields in brackets.

Yield determined by 1H NMR spectroscopy using 1,3,5-trimethoxybenzene as internal standard.

Figure 2.

ORTEP plot of the major enantiomer of 3aa, obtained using (R)-L10 ligand. All hydrogen atoms are omitted for clarity.

Then, we turned our attention to the effect of substitution at the iodoarene coupling partner (Scheme 4b). A variety of functional groups at the para- and meta-positions of iodoarenes, including electron-donating and electron-withdrawing substituents, were tolerated, affording the corresponding chiral biaryl chromium complexes 3 in moderate yield and high enantioselectivities. The reaction is compatible with carbonyl functionalities such as ester, ketone, and aldehydes (3ea,ek,el). Nitrogen-containing substituents, such as nitro (3ed) and cyano (3ec), can be present on the iodoarene. The reaction is also compatible with Br and Cl substituents (3eg,em), which would allow for further functionalization via cross-couplings, CF3 substituents (3ef) and 3,5-disubstituted iodoarenes (3eo). For p-substituted iodoarenes, higher er values are obtained with electron-poor arenes (3ea–3eg) than with electron-rich derivatives (3ei). However, similar enantioselectivities were observed for m-substituted iodoarenes regardless of their electronic properties (3ek–3en). On the other hand, ortho-substituted iodoarenes showed low reactivity (3ap,aq).

Analysis over time of the reaction of 1e with 2b shows that at low conversions the product 3eb is formed in 92:8 er. However, the er increases steadily throughout the reaction, in parallel to the formation of bisarylation product 4eb, with er reaching 98:2 when 27% of bisarylated 4eb has been formed (see SI). This suggests that the observed er values in Scheme 4 are the result of an asymmetric C–H arylation step compounded with a kinetic resolution of the product.

2.4. Mechanistic Studies

2.4.1. Role of Ag(I) Salts in Asymmetric Arylation of (Fluoroarene)Cr(CO)3 Complexes

Recent studies by our group on Pd-catalyzed direct functionalization of aryl C–H bonds in the presence of silver salts revealed that phosphine ligated silver carboxylate can metalate the C–H bonds in arenes bound to a Cr(CO)3 fragment;27 the resulting arylsilver(I) complex is then proposed to transfer its aryl moiety to a palladium intermediate. Similar conclusions were also drawn by Sanford37 and Hartwig,38 in the case of thiophenes and (poly)fluoroarenes, and we have recently exploited this activation mode to develop the first direct α–arylation of benzo[b]thiophenes and thiophenes at room temperature.39

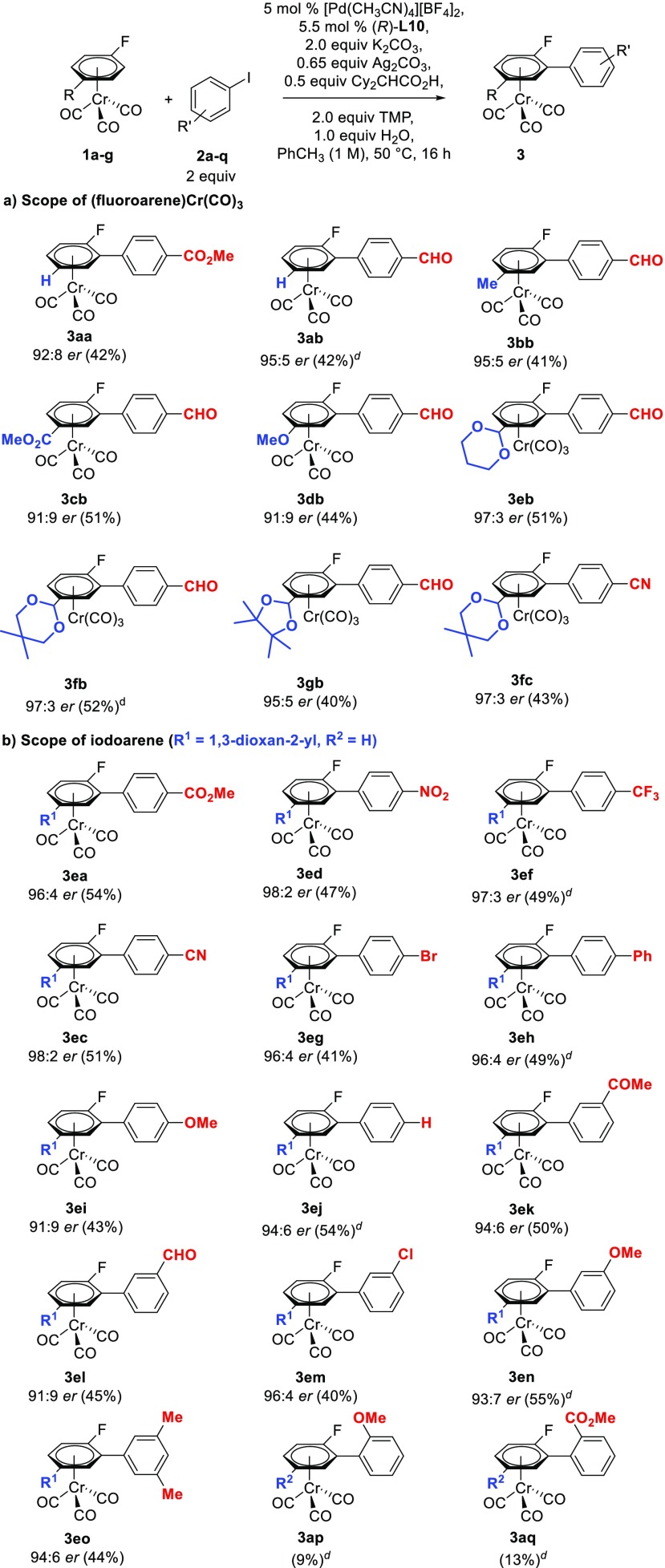

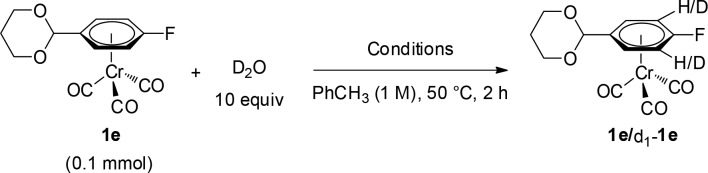

As this reaction did not proceed in the absence of silver (Table 1, entry 8), we hypothesized that in this case the silver salt would also be involved in the C–H bond cleavage step. To test this hypothesis, we studied the H/D exchange of 1e with 10 equiv of D2O in the presence of different combinations of additives (Table 4). No deuteration was observed when 1e was submitted to the standard reaction conditions in the absence of the silver salt (Table 4, entry 1). Deuterated complex d1-1e was not detected when the reaction was carried out only in the presence of Ag2CO3 (entry 2), or in combination with the chiral ligand L10 with or without the carboxylic acid (entries 3–4). Importantly, in entries 2–4, the silver salt was appreciably insoluble in toluene. On the other hand, addition of TMP to Ag2CO3 led to formation of 32% of d1-1e (entry 5). This is consistent with a higher solubility of the Ag-salt either through coordination or increased solvent polarity. Addition of 5.5 mol % of L10 led to an increased H/D exchange of 54% (entry 6), consistent with an enhanced rate of C–H activation of the Ag-L10 complex. Similarly enhanced H/D exchange was obtained when both L10 and the carboxylate were added in the presence of TMP (entry 7). Interestingly, 1H and 31P NMR analysis of the reaction mixture in entry 7 revealed the presence of a Ag-L10 complex. These results are consistent with a silver(I)-mediated C–H activation step in operation under the present reaction conditions that likely involves a coordinated L10 ligand.

Table 4. H/D Exchange Experiments of 1ea.

| Entry | Conditions | d1-1e (%)a |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Standard conditions without Ag2CO3 | 0 |

| 2 | 0.65 equiv Ag2CO3 | 0 |

| 3 | 0.65 equiv Ag2CO3, 5.5 mol % (R)-L10 | 0 |

| 4 | 0.65 equiv Ag2CO3, 5.5 mol % (R)-L10, 0.5 equiv Cy2CHCO2H | 0 |

| 5 | 0.65 equiv Ag2CO3, 2 equiv TMP | 32 |

| 6 | 0.65 equiv Ag2CO3, 5.5 mol % (R)-L10, 2 equiv TMP | 54 |

| 7 | 0.65 equiv Ag2CO3, 5.5 mol % (R)-L10, 0.5 equiv Cy2CHCO2H, 2 equiv TMP | 48 |

Determined by 1H NMR spectroscopy using 1,3,5-trimethoxybenzene as internal standard.

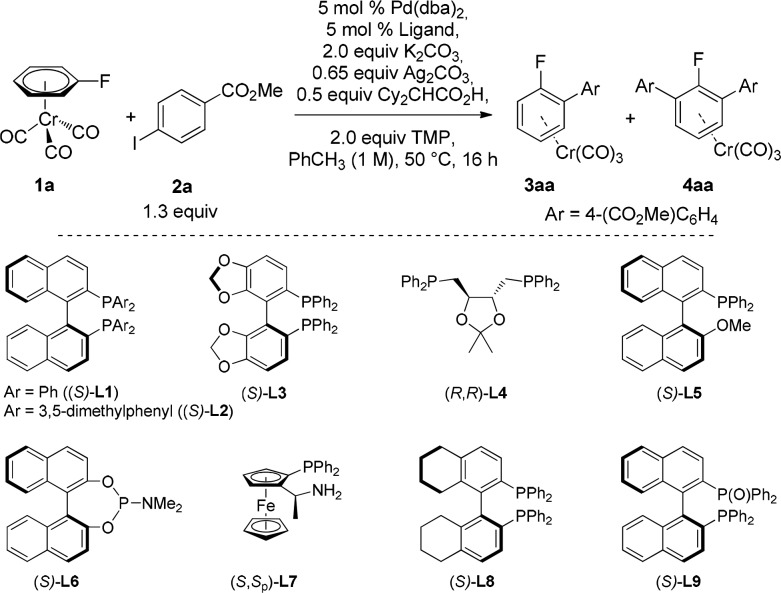

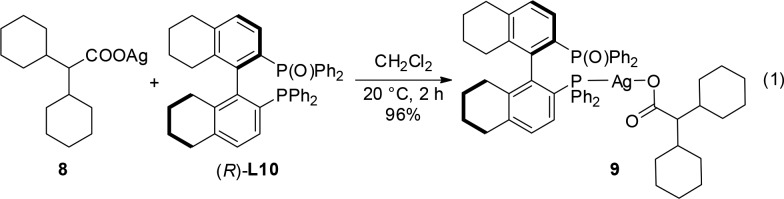

Reaction of silver carboxylate 8 with 1 equiv of (R)-H8-BINAP(O) ((R)-L10) in CH2Cl2 at room temperature afforded the phosphine-ligated Ag(I) carboxylate 9 in 96% yield (eq 1). Its structure was confirmed by X-ray diffraction analysis (Figure 3). 1H and 31P NMR analysis of 9 matched with those observed in the reaction mixture of Table 4, entry 7, confirming the presence of the Ag-L10 complex.38,40 Furthermore, 31P NMR analysis of the reaction of 1e with 2i under our standard conditions, after 2 h (Figure 4a), clearly showed resonances corresponding to the (R)-H8-BINAP(O)-ligated silver carboxylate 9, strongly suggesting its participation in the catalytic cycle (Figure 4b).

|

1 |

Figure 3.

ORTEP plot of (R)-H8-BINAP(O)-ligated silver carboxylate 9. Selected bonds and angles: P(1)–Ag(1), 2.330(2) Å; P(2)–Ag(1), 3.463(2) Å; O(1)–Ag(1), 3.270 (4) Å; O(2)–Ag(1), 2.797 (5) Å; O(3)–Ag(1), 2.107 (5) Å; O(3)–Ag(1)–P(1), 123.35°. All hydrogen atoms omitted for clarity.

Figure 4.

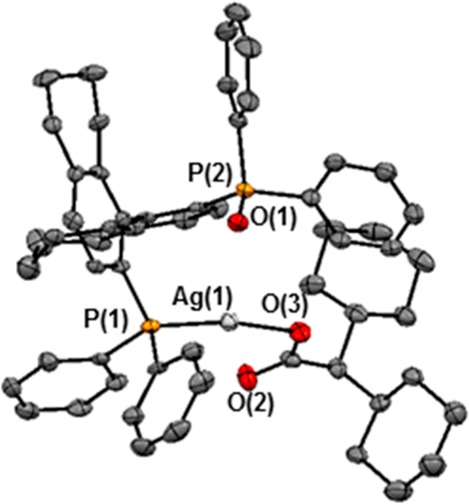

31P NMR spectra in CDCl3 of (a) reaction mixture of 1e with 2i under asymmetric catalytic conditions after 2 h; (b) (R)-H8-BINAP(O)-ligated silver carboxylate 9; (c) L*PdAr-carboxylate 12.

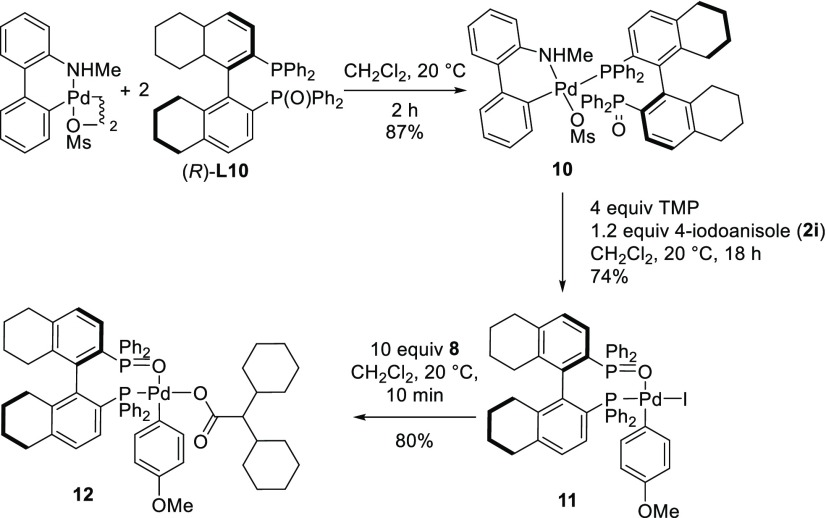

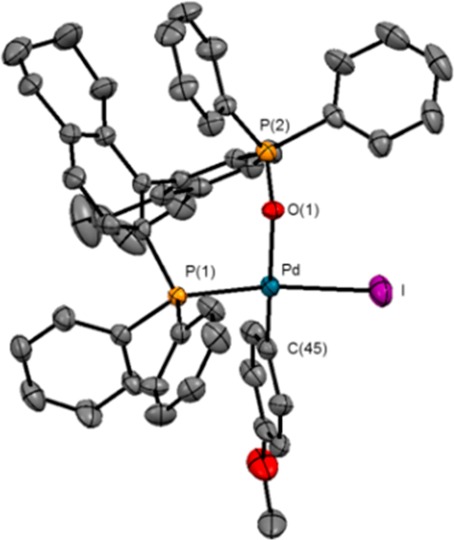

Interestingly, another smaller set of signals, presumably corresponding to a PdL* compound, were present in the 31P NMR spectrum of the reaction mixture (Figure 4a). We speculated that these could correspond to Pd-complexes 11 or 12 (Scheme 5). Complex 11 was synthesized via the Buchwald-type palladium derivative 10,41 which underwent smooth oxidative addition with 4-iodoanisole to give 11 (Scheme 5). The structure of 11 was confirmed by single-crystal X-ray diffraction analysis (Figure 5). 12 was prepared from 11 by reaction with AgO2CCHCy2 (8). Comparison of the 31P NMR of both 11 and 12 with those observed in the analysis of the catalytic reaction mixture, revealed that the small set of signals in the latter corresponded to 12 (Figure 4c). This analysis highlights that the ligand L10 can coordinate to both Ag and Pd in the reaction. While qualitative analysis suggests that the majority of L10 would be coordinated to Ag, it cannot be discarded that it also plays a role in the reactivity of the Pd-species.

Scheme 5. Synthesis of H8-BINAP(O)-Ligated Palladium Complexes.

Figure 5.

ORTEP plot of (R)-H8-BINAP(O)-ligated IArPd complex 11. Selected bonds and angles: I–Pd, 2.6352(9) Å; Pd–P(1), 2.282(2) Å; Pd–O(1), 2.234(6) Å; Pd–C(45), 1.980(10) Å; P(1)–Pd–I, 167.66(6)°; O(1)–Pd–I, 93.88(17)°; O(1)–Pd–P(1), 87.32(18)°; C(45)–Pd–I, 85.8(3)°; C(45)–Pd–P(1), 94.1(3)°; C(45)–Pd–O(1), 174.7(3)°. All hydrogen atoms are omitted for clarity.

2.4.2. Proposed Catalytic Cycle

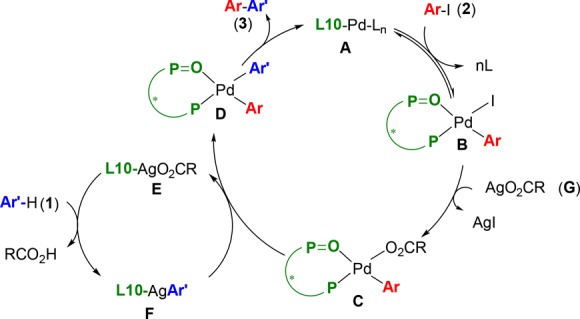

From the experiments above and previous work in the field,27 we propose the bimetallic catalytic cycle outlined in Scheme 6 to be in operation. In this mechanism, a Pd(0)-L10 complex A undergoes oxidative addition to B, which after transmetalation affords arylcarboxylate-Pd derivative C, structurally related to complex 12. In a parallel catalytic cycle, silver carboxylate E carries out C–H activation on η6-coordinated arene 1 to form arylsilver intermediate F, presumably by a carboxylate assisted CMD mechanism.37 Transmetalation from silver intermediate F to the palladium-arylcarboxylate C(38) would form D, which would in turn release the product 3 after reductive elimination. We propose that L10 is coordinated to both Ag and Pd, throughout the process. Two possible enantiodetermining steps must thus be considered: an enantioselective C–H activation by complex E, followed by a fast transmetalation with C, or alternatively a fast reversible C–H activation, followed by a rate and enantioselectivity determining transmetalation. However, further experiments will be necessary to understand this process fully, which is further complicated by the low solubility of some of the species in toluene.

Scheme 6. Proposed Mechanism.

2.5. Synthesis and Derivatization of Enantioenriched Planar-Chiral (Arene)Chromium Tricarbonyl Phosphines

The presence of a C–F bond in the aromatic core of the chiral (arene)chromium complexes allows easy functionalization via a variety of nucleophilic aromatic substitutions,42 including phosphination reactions, to obtain arylphosphine derivatives easily.

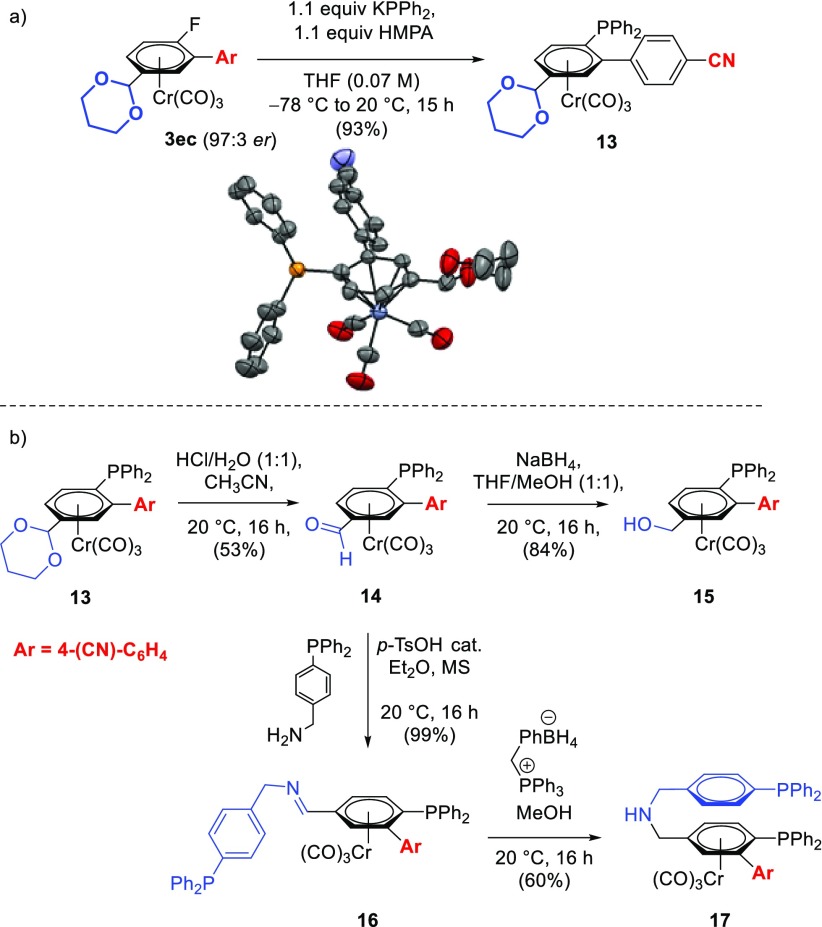

Nelson and co-workers investigated the effectiveness of optically active arylmonophosphine Cr-complexes as ligands in asymmetric catalysis in the Pd(II)-catalyzed alkylation of allylic acetates under Trost’s conditions,8b thus demonstrating that chromium-complexed arylphosphines provide chiral equivalents of triarylphosphine ligands that are ubiquitous in late transition-metal chemistry and catalysis. To test the applicability of our approach for the synthesis of new planar-chiral phosphines we carried out the asymmetric arylation of 1e with 4-iodobenzonitrile (2c) at 1 mmol scale under the standard catalytic conditions. Enantioenriched product 3ec was obtained in 48% yield with 97:3 er. Reaction of 3ec with potassium diphenylphosphide resulted in nucleophilic aromatic substitution to afford the chiral planar triarylphosphine (Sp)-13 in 93% yield and 97:3 enantiomeric ratio. The structure and absolute stereochemistry of 13 was confirmed by X-ray diffraction analysis (Scheme 7a).

Scheme 7. (a) Synthesis and ORTEP Plot of 13; (b) Derivatization of Planar-Chiral Monophosphines, and Synthesis of Novel Planar-Chiral Diphosphines.

All hydrogen atoms omitted for clarity.

The protected aldehyde on 13 provides an ideal handle for further derivatization and tuning of electronic properties of this chiral phosphine. Accordingly, treatment of 13 under acidic conditions revealed the aldehyde to obtain 14, which could then be reduced by NaBH4 to the alcohol derivative 15 (Scheme 7b). Both the aldehyde in 14 and the alcohol in 15 could then be easily transformed into a variety of functionalities. Over the past few decades, chiral diphosphines have proven to be among the most useful and versatile ligands for metal-catalyzed asymmetric reactions and the design and preparation of such diphosphines remains as active an area of research as ever.43 The synthesis of C2-symmetric diphosphine ligands has long received the most attention, due perhaps to the relative ease of obtaining these molecules.44 However, studies have showed that C2 symmetry is not a necessary condition for attaining high enantioselectivity in catalysis.45 Our functionalized planar chiral phosphines, such as 14 and 15, are ideal starting points for the synthesis of novel classes of planar chiral diphosphines. Reaction of the aldehyde derivative 14 with p-(diphenylphosphino)benzylamine in the presence of a catalytic amount of acid afforded the diphosphine-imine derivative 16 in quantitative yield. This compound can be reduced by benzyltriphenylphosphonium tetrahydroborate to give the corresponding chiral amine-diphosphine derivative 17, providing a novel class of bidentate chiral phosphines (Scheme 7b).

3. Conclusions

In conclusion, we have developed the first protocol for catalytic direct C–H asymmetric arylation of (η6-arene)chromiumtricarbonyl complexes to afford enantioenriched planar-chiral products in one step. The development of this methodology required the synthesis of a new family of H8-BINAP derivatives, finding that H8-BINAP(O) was the most suitable chiral ligand for the reaction. Optimized catalytic conditions were applied to a variety of iodoarenes and (fluoroarene)Cr(CO)3 complexes affording the corresponding chiral products in good yield and excellent enantioselectivity. Mechanistic studies suggest that the reaction proceeds through a Pd/Ag bimetallic double catalytic cycle where the C–H activation is carried out by Ag. These enantioenriched aryl-complexes can be used for the synthesis of chiral planar monodentate phosphines and a new class of chiral planar bidentate phosphines. The application of these new chiral ligands to asymmetric catalysis is currently under investigation.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EPSRC, EP/L014017/2) and the Marie Skłodowska Curie actions (IF-702177 to M.B.) for funding.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acscatal.9b00918.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- a Pape A. R.; Kaliappan K. P.; Kündig E. P. Transition-Metal-Mediated Dearomatization Reactions. Chem. Rev. 2000, 100, 2917–2940. 10.1021/cr9902852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Rose-Munch F.; Rose E. In Modern Arene Chemistry; Astruc D., Ed.; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, 2002; pp 368–399. [Google Scholar]; c Gibson S. E.; Ibrahim H. Asymmetric Catalysis Using Planar Chiral Arene Chromium Complexes. Chem. Commun. 2002, 2465–2473. 10.1039/b205479p. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; d Kündig E. P.; Pache S. H. In Science of Synthesis; Imamoto T., Ed.; Thieme: Stuttgart/New York, 2002, Vol. 2, pp 155–228. [Google Scholar]; e Salzer A. Chiral Mono- and Bidentate Ligands Derived from Chromium Arene Complexes-Synthesis, Structure and Catalytic Applications. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2003, 242, 59–72. 10.1016/S0010-8545(03)00059-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; f Schmalz H.-G.; Siegel S. In Transition Metals for Organic Synthesis. Building Blocks and Fine Chemicals; Beller M., Bolm C., Eds.; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, 2004, Vol. 1, pp 550–559. [Google Scholar]; g Uemura M.Benzylic Activation and Stereochemical Control in Reactions of Tricarbonyl(arene)chromium Complexes. In Organic Reactions; Uemura M., Ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2006; Vol. 67, pp 217–657. [Google Scholar]; h Rosillo M.; Domínguez G.; Pérez-Castells J. Chromium Arene Complexes in Organic Synthesis. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2007, 36, 1589–1604. 10.1039/b606665h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; i Patra M.; Merz K.; Metzler-Nolte N. Planar Chiral (η6-Arene)Cr(CO)3 Containing Carboxylic Acid Derivatives: Synthesis and Use in the Preparation of Organometallic Analogues of the Antibiotic Platensimycin. Dalton Trans. 2012, 41, 112–117. 10.1039/C1DT10918A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Applications in asymmetric total synthesis of natural products:; a Uemura M.; Daimon A.; Hayashi Y. An Asymmetric Synthesis of an Axially Chiral Biaryl via an (Arene)chromium Complex: Formal Synthesis of (−)-Steganone. J. Chem. Soc., Chem. Commun. 1995, 0, 1943–1944. 10.1039/C39950001943. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Majdalani A.; Schmalz H.-G. Chiral η6-Arene-Cr(CO)3 Complexes in Organic Synthesis: A Short and Highly Selective Synthesis of the 18-nor-seco-Pseudopterosin Aglycone. Tetrahedron Lett. 1997, 38, 4545–4548. 10.1016/S0040-4039(97)00995-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Schellhaas K.; Schmalz H.-G.; Bats J. W. Chiral [η6-Arene-Cr(CO)3] Complexes as Synthetic Building Blocks: A Short Enantioselective Total Synthesis of (+)-Ptilocaulin. Chem. - Eur. J. 1998, 4, 57–66. . [DOI] [Google Scholar]; d Ratni H.; Kündig E. P. Synthesis of (−)-Lasubine(I) via a Planar Chiral [(η6-arene)Cr(CO)3] Complex. Org. Lett. 1999, 1, 1997–1999. 10.1021/ol991158v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Kamikawa K.; Uemura M. Stereoselective Synthesis of Axially Chiral Biaryls Utilizing Planar Chiral (Arene)chromium Complexes. Synlett 2000, 2000, 938–949. [Google Scholar]; f Monovich L. G.; Le Huérou Y.; Rönn M.; Molander G. A. Total Synthesis of (−)-Steganone Utilizing a Samarium(II) Iodide Promoted 8-Endo Ketyl-Olefin Cyclization. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000, 122, 52–57. 10.1021/ja9930059. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; g Bringmann G.; Gulder T.; Gulder T. A. M.; Breuning M. Atroposelective Total Synthesis of Axially Chiral Biaryl Natural Products. Chem. Rev. 2011, 111, 563–639. 10.1021/cr100155e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Hayashi T. In Ferrocenes; Togni A., Hayashi T., Eds.; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, 1995; pp 105–142. [Google Scholar]; b Togni A. In Metallocenes; Togni A., Halterman R. L., Eds.; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, 1998; Vol. 2, pp 685–722. [Google Scholar]; c Fu G. C. Enantioselective Nucleophilic Catalysis with “Planar-Chiral” Heterocycles. Acc. Chem. Res. 2000, 33, 412–420. 10.1021/ar990077w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Dai L.-X.; Tu T.; You S.-L.; Deng W.-P.; Hou X.-L. Asymmetric Catalysis with Chiral Ferrocene Ligands. Acc. Chem. Res. 2003, 36, 659–667. 10.1021/ar020153m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Colacot T. J. A Concise Update on the Applications of Chiral Ferrocenyl Phosphines in Homogeneous Catalysis Leading to Organic Synthesis. Chem. Rev. 2003, 103, 3101–3118. 10.1021/cr000427o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f Barbaro P.; Bianchini C.; Giambastiani G.; Parisel S. L. Progress in Stereoselective Catalysis by Metal Complexes with Chiral Ferrocenyl Phosphines. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2004, 248, 2131–2150. 10.1016/j.ccr.2004.03.022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; g Fu G. C. Asymmetric Catalysis with “Planar-Chiral” Derivatives of 4-(Dimethylamino)pyridine. Acc. Chem. Res. 2004, 37, 542–547. 10.1021/ar030051b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; h Gomez Arrayás R. G.; Adrio J.; Carretero J. C. Recent Applications of Chiral Ferrocene Ligands in Asymmetric Catalysis. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2006, 45, 7674–7715. 10.1002/anie.200602482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; i Fu G. C. Applications of Planar-Chiral Heterocycles as Ligands in Asymmetric Catalysis. Acc. Chem. Res. 2006, 39, 853–860. 10.1021/ar068115g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; j Ganter C. In Phosphorus Ligands in Asymmetric Catalysis; Börner A., Ed.; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, 2008; pp 393–407. [Google Scholar]

- Uemura M.; Miyake R.; Nishimura H.; Matsumoto Y.; Hayashi T. New Chiral Phosphine Ligands Containing (η6-Arene)chromium and Catalytic Asymmetric Cross-Coupling Reactions. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry 1992, 3, 213–216. 10.1016/S0957-4166(00)80193-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Uemura M.; Miyake R.; Nakayama K.; Shiro M.; Hayashi Y. Chiral (η6-Arene)chromium Complexes in Organic Synthesis: Stereoselective Synthesis of Chiral (Arene)chromium Complexes Possessing Amine and Hydroxy Groups and Their Application to Asymmetric Reactions. J. Org. Chem. 1993, 58, 1238–1244. 10.1021/jo00057a042. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Ogasawara M.; Wu W.-Y.; Arae S.; Watanabe S.; Morita T.; Takahashi T.; Kamikawa K. Kinetic Resolution of Planar-Chiral (η6-Arene)Chromium Complexes by Molybdenum-Catalyzed Asymmetric Ring-Closing Metathesis. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 2951–2955. 10.1002/anie.201108292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Ogasawara M.; Tseng Y.-Y.; Arae S.; Morita T.; Nakaya T.; Wu W.-Y.; Takahashi T.; Kamikawa K. Phosphine–Olefin Ligands Based on a Planar-Chiral (π-Arene)chromium Scaffold: Design, Synthesis, and Application in Asymmetric Catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 9377–9384. 10.1021/ja503060e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Englert U.; Haerter R.; Vasen D.; Salzer A.; Eggeling E. B.; Vogt D. Optically Active Transition-Metal Complexes. 91. A General Stereoselective Route to α-Chiral (R)-Tricarbonyl(η6-ethylbenzene)chromium Complexes. Novel Organometallic Phosphine Catalysts for the Asymmetric Hydrovinylation Reaction. Organometallics 1999, 18, 4390–4398. 10.1021/om990386q. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Hayashi Y.; Sakai H.; Kaneta N.; Uemura M. New Chiral Chelating Phosphine Complexes Containing Tricarbonyl (η6-Arene)chromium for Highly Enantioselective Allylic Alkylation. J. Organomet. Chem. 1995, 503, 143–148. 10.1016/0022-328X(95)05541-V. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Nelson S. G.; Hilfiker M. A. Asymmetric Synthesis of Monodentate Phosphine Ligands Based on Chiral η6-Cr[arene] Templates. Org. Lett. 1999, 1, 1379–1382. 10.1021/ol990929s. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Han J. W.; Jang H.-Y.; Chung Y. K. Synthesis and Use in Palladium-Catalyzed Asymmetric Allylic Alkylation of New Planar Chiral Chromium Complexes of 1,2-Disubstituted Arenes Having Pyridine and Aryl Phosphine Groups. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry 1999, 10, 2853–2861. 10.1016/S0957-4166(99)00296-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; d Vasen D.; Salzer A.; Gerhards F.; Gais H.-J.; Stürmer R.; Bieler N. H.; Togni A. Optically Active Transition-Metal Complexes. 10.1 Bifunctional Arene-Chromium-Tricarbonyl Complexes Derived from (R)-Phenylethanamine: Easily Accessible Planar-Chiral Diphosphines and Their Application in Enantioselective Hydrogenation, Hydroamination, and Allylic Sulfonation. Organometallics 2000, 19, 539–546. 10.1021/om9907674. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Jones G. B.; Heaton S. B.; Chapman B. J.; Guzel M. On the Origins of Enantioselectivity in Oxazaborolidine Mediated Carbonyl Reductions. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry 1997, 8, 3625–3636. 10.1016/S0957-4166(97)00497-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Pasquier C.; Naili S.; Pelinski L.; Brocard J.; Mortreux A.; Agbossou F. Synthesis and Application in Enantioselective Hydrogenation of New Free and Chromium Complexed Aminophosphine–Phosphinite Ligands. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry 1998, 9, 193–196. 10.1016/S0957-4166(97)00642-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Son S. U.; Jang H.-Y.; Lee I. S.; Chung Y. K. Synthesis of Planar Chiral (1,2-Disubstituted arene)chromium Tricarbonyl Compounds and Their Application in Asymmetric Hydroboration. Organometallics 1998, 17, 3236–3239. 10.1021/om980228j. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Weber I.; Jones G. B. Bidentate Planar Chiral η6-Arene Tricarbonyl Chromium(0) Complexes: Ligands for Catalytic Asymmetric Alkene Hydrosilylation. Tetrahedron Lett. 2001, 42, 6983–6986. 10.1016/S0040-4039(01)01471-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Solladie-Cavallo A.; Solladie G.; Tsamo E. Chiral (Arene)tricarbonylchromium Complexes: Resolution of Aldehydes. J. Org. Chem. 1979, 44, 4189–4191. 10.1021/jo01337a039. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Davies S. G.; Goodfellow C. L. Asymmetric Synthesis of α-Substituted o-Methoxybenzyl Alcohols via Stereoselective Additions to Kinetically Resolved o-Anisaldehyde- (tricarbony1)chromium. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 1 1989, 192–194. 10.1039/P19890000192. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Nakamura K.; Ishihara K.; Ohno A.; Uemura M.; Nishimura H.; Hayashi Y. Kinetic Resolution of (η6-Arene)chromium Complexes by a Lipase. Tetrahedron Lett. 1990, 31, 3603–3604. [Google Scholar]; d Bromley L. A.; Davies S. G.; Goodfellow C. L. Stereoselective Synthesis of Homochiral Alpha Substituted o-Metboxybenzyl Alcohols VZQ Nucleophilic Additions to Kinetically Resolved Homocbiral Tricarbonyl (η6-o-anisaldehyde)chromium(0). Tetrahedron: Asymmetry 1991, 2, 139–156. 10.1016/S0957-4166(00)80533-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; e Malézieux B.; Jaouen G.; Salatin J.; Howell J. A. S.; Palin M. G.; McArdle P.; O’Gara M.; Cunningham D. Enzymatic Generation of Planar Chirality in the (Arene)tricarbonylchromium Series. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry 1992, 3, 375–376. 10.1016/S0957-4166(00)80279-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Solladie-Cavallo A.; Quazzotti S.; Colonna S.; Manfredi A. Arene-chromium-tricarconyl Complexes: Stereoselective Reactions with Isocyanide. Tetrahedron Lett. 1989, 30, 2933–2936. 10.1016/S0040-4039(00)99162-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Alexakis A.; Mangeney P.; Marek I.; Rose-Munch F.; Rose E.; Semra A.; Robert F. Resolution and Asymmetric Synthesis of Ortho-Substituted (Benzaldehyde)tricarbonylchromium Complexes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1992, 114, 8288–8290. 10.1021/ja00047a049. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Schmalz H.-G.; Millies B.; Bats J. W.; Dürner G. Diastereoselective Complexation of Temporarily Chirally Modified Ligands: Enantioselective Preparation and Configurational Assignment of Synthetically Valuable η6-Tricarbonylchromium- 1-tetralone Derivatives. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 1992, 31, 631–633. 10.1002/anie.199206311. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; d Kündig E. P.; Leresche J.; Saudan L.; Bernardinelli G. Chiral Tricarbonyl(η6-cyclobutabenzene)chromium Complexes. Diastereoselective Synthesis and Use in Asymmetric Cycloaddition Reactions. Tetrahedron 1996, 52, 7363–7378. 10.1016/0040-4020(96)00257-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; e Jones G. B.; Guzel M. Enantioselective Cycloadditions Catalyzed by Face Resolved Arene Chromium Carbonyl Complexes. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry 1998, 9, 2023–2026. 10.1016/S0957-4166(98)00200-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Coote S. J.; Davies S. G.; Goodfellow C. L.; Sutton K. H.; Middlemiss D.; Naylor A. Tricarbonylchromium(0) Promoted Stereoselective Transformations of Ephedrine and Pseudoephedrine Derivatives. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry 1990, 1, 817–842. 10.1016/S0957-4166(00)80447-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Kondo Y.; Green J. R.; Ho J. Tartrate-Derived Aryl Aldehyde Acetals in the Asymmetric Directed Metalation of Chromium Tricarbonyl Arene Complexes. J. Org. Chem. 1993, 58, 6182–6189. 10.1021/jo00075a008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Price D. A.; Simpkins N. S.; MacLeod A. M.; Watt A. P. Chiral Base-Mediated Asymmetric Synthesis of Tricarbonyl(η6-arene)chromium Complexes. J. Org. Chem. 1994, 59, 1961–1962. 10.1021/jo00087a004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; d Kündig E. P.; Quattropani A. Planar Chiral Arene Tricarbonylchromium Complexes via Enantioselective Deprotonation/Electrophile Addition Reactions. Tetrahedron Lett. 1994, 35, 3497–3500. 10.1016/S0040-4039(00)73219-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; e Alexakis A.; Kanger T.; Mangeney P.; Rose-Munch F.; Perrotey A.; Rose E. Enantioselective ortho-Lithiation of Aminals of Benzaldehyde Chromiumtricarbonyl Complex. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry 1995, 6, 47–50. 10.1016/0957-4166(94)00348-F. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; f Alexakis A.; Kanger T.; Mangeney P.; Rose-Munch F.; Perrotey A.; Rose E. Enantioselective Ortho-Lithiation of Benzaldehyde Chromiumtricarbonyl Complex. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry 1995, 6, 2135–2138. 10.1016/0957-4166(95)00283-U. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; g Han J. W.; Son S. U.; Chung Y. K. Chiral Auxiliary-Directed Asymmetric Ortho-Lithiation of (Arene)tricarbonylchromium Complexes. J. Org. Chem. 1997, 62, 8264–8267. 10.1021/jo9712761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; h Gibson née Thomas S. E.; Reddington E. G. Asymmetric Functionalisation of Tricarbonylchromium(0) Complexes of Arenes by Non-Racemic Chiral Bases. Chem. Commun. 2000, 989–996. 10.1039/a909037a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; i Tan Y.-L.; Widdowson D. A.; Wilhelm R. Reversal of Asymmetric Induction in Arenetricarbonyl-chromium(0) Complexes via Dilithiation with the (−)-Sparteine/BuLi System and Enantioselective Quench. Synlett 2001, 2001, 1632–1634. 10.1055/s-2001-17445. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; j Alexakis A.; Tomassini A.; Andrey O.; Bernardinelli G. Diastereoselective Alkylation of (Arene)tricarbonylchromium and Ferrocene Complexes Using a Chiral, C2-Symmetrical 1,2-Diamine as Auxiliary. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2005, 2005, 1332–1339. 10.1002/ejoc.200400662. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Fretzen A.; Kündig E. P. Enantioselective Synthesis of Planar Chiral (Cr(η6-Arene)(CO)3] Complexes via Nucleophilic Addition/Hydride Abstraction. Helv. Chim. Acta 1997, 80, 2023–2026. 10.1002/hlca.19970800619. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Fretzen A.; Ripa A.; Liu R.; Bernardinelli G.; Kündig E. P. 1,2-Disubstituted [(η6-Arene)Cr(CO)3] Complexes by Sequential Nucleophilic Addition/endo-Hydride Abstraction. Chem. - Eur. J. 1998, 4, 251–259. . [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Uemura M.; Nishimura H.; Hayashi T. Catalytic Asymmetric Induction of Planar Chirality by Palladium-Catalyzed Asymmetric Cross-Coupling of a meso (Arene)chromium Complex. Tetrahedron Lett. 1993, 34, 107–110. 10.1016/S0040-4039(00)60069-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Gotov B.; Schmalz H.-G. A Catalytic-Enantioselective Entry to Planar Chiral π-Complexes: Enantioselective Methoxycarbonylation of 1,2-Dichlorobenzene–Cr(CO)3. Org. Lett. 2001, 3, 1753–1756. 10.1021/ol0159468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Böttcher A.; Schmalz H.-G. Catalytic-Enantioselective Methoxycarbonylation of 1,3-Dichloroarenetricarbonyl-chromium(0) Complexes: A Desymmetrization Approach to Planar Chirality. Synlett 2003, 1595–1598. 10.1055/s-2003-41417. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Kündig E. P.; Chaudhuri P. D.; House D.; Bernardinelli G. Catalytic Enantioselective Hydrogenolysis of [Cr(CO)3(5,8-Dibromonaphthalene)]. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2006, 45, 1092–1095. 10.1002/anie.200502688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Mercier A.; Urbaneja X.; Yeo W. C.; Chaudhuri P. D.; Cumming G. R.; House D.; Bernardinelli G.; Kündig E. P. Asymmetric Catalytic Hydrogenolysis of Aryl Halide Bonds in Fused Arene Chromium and Ruthenium Complexes. Chem. - Eur. J. 2010, 16, 6285–6299. 10.1002/chem.201000011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamikawa K.; Harada K.; Uemura M. Catalytic Asymmetric Induction of Planar Chirality: Palladium Catalyzed Intramolecular Mizoroki–Heck Reaction of Prochiral (Arene)chromium Complexes. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry 2005, 16, 1419–1423. 10.1016/j.tetasy.2005.02.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Murai M.; Uenishi J.; Uemura M. Gold(I)-Catalyzed Asymmetric Synthesis of Planar Chiral Arene Chromium Complexes. Org. Lett. 2010, 12, 4788–4791. 10.1021/ol1019376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Murai M.; Sota Y.; Onohara Y.; Uenishi J.; Uemura M. Gold(I)-Catalyzed Asymmetric Induction of Planar Chirality by Intramolecular Nucleophilic Addition to Chromium-Complexed Alkynylarenes: Asymmetric Synthesis of Planar Chiral (1H-Isochromene and 1,2-Dihydroisoquinoline)chromium Complexes. J. Org. Chem. 2013, 78, 10986–10995. 10.1021/jo401893f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- For selected recent publications, see for example:; a Liao K.; Negretti S.; Musaev D. G.; Bacsa J.; Davies H. M. L. Site-Selective and Stereoselective Functionalization of Unactivated C–H Bonds. Nature 2016, 533, 230–234. 10.1038/nature17651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Chen G.; Gong W.; Zhuang Z.; Andrä M. S.; Chen Y.-Q.; Hong X.; Yang Y.-F.; Liu T.; Houk K. N.; Yu J.-Q. Ligand-Accelerated Enantioselective Methylene C(sp3)–H Bond Activation. Science 2016, 353, 1023–1027. 10.1126/science.aaf4434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Chen X.; Cheng Z.; Guo J.; Lu Z. Asymmetric Remote C-H Borylation of Internal Alkenes via Alkene Isomerization. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 3939. 10.1038/s41467-018-06240-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Liu W.; Ren Z.; Bosse A. T.; Liao K.; Goldstein E. L.; Bacsa J.; Musaev D. G.; Stoltz B. M.; Davies H. M. L. Catalyst-Controlled Selective Functionalization of Unactivated C–H Bonds in the Presence of Electronically Activated C–H Bonds. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 12247–12255. 10.1021/jacs.8b07534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Mazzarella D.; Crisenza G. E. M.; Melchiorre P. Asymmetric Photocatalytic C–H Functionalization of Toluene and Derivatives. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 8439–8443. 10.1021/jacs.8b05240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f Pedroni J.; Cramer N. Enantioselective C–H Functionalization–Addition Sequence Delivers Densely Substituted 3-Azabicyclo[3.1.0]hexanes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 12398–12401. 10.1021/jacs.7b07024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g Sun Y.; Cramer N. Enantioselective Synthesis of Chiral-at-Sulfur 1,2-Benzothiazines by CpxRhIII-Catalyzed C–H Functionalization of Sulfoximines. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2018, 57, 15539–15543. 10.1002/anie.201810887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- For reviews, see:; a Giri R.; Shi B.-F.; Engle K. M.; Maugel N.; Yu J.-Q. Transition Metal-Catalyzed C–H Activation Reactions: Diastereoselectivity and Enantioselectivity. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2009, 38, 3242–3272. 10.1039/b816707a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Peng H. M.; Dai L.-X.; You S.-L. Enantioselective Palladium-Catalyzed Direct Alkylation and Olefination Reaction of Simple Arenes. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2010, 49, 5826–5828. 10.1002/anie.201000799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Wencel-Delord J.; Colobert F. Asymmetric C-(sp2)-H Activation. Chem. - Eur. J. 2013, 19, 14010–14017. 10.1002/chem.201302576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Engle K. M.; Yu J.-Q. Developing Ligands for Palladium(II)-Catalyzed C–H Functionalization: Intimate Dialogue between Ligand and Substrate. J. Org. Chem. 2013, 78, 8927–8955. 10.1021/jo400159y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Zheng C.; You S.-L. Recent Development of Direct Asymmetric Functionalization of Inert C–H Bonds. RSC Adv. 2014, 4, 6173–6214. 10.1039/c3ra46996d. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; f Ye B.; Cramer N. Chiral Cyclopentadienyls: Enabling Ligands for Asymmetric Rh(III)-Catalyzed C–H Functionalizations. Acc. Chem. Res. 2015, 48, 1308–1318. 10.1021/acs.accounts.5b00092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g You S.-L. In Asymmetric Functionalization of C–H Bonds; You S.-L., Ed.; RSC: Cambridge, 2015. [Google Scholar]; h Newton C. G.; Wang S.-G.; Oliveira C. C.; Cramer N. Catalytic Enantioselective Transformations Involving C–H Bond Cleavage by Transition-Metal Complexes. Chem. Rev. 2017, 117, 8908–8976. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.6b00692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; i Saint-Denis T. G.; Zhu R.-Y.; Chen G.; Wu Q.-F.; Yu J.-Q. Enantioselective C(sp3)–H Bond Activation by Chiral Transition Metal Catalysts. Science 2018, 359, eaao4798. 10.1126/science.aao4798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- For recent reviews, see:; a Arae S.; Ogasawara M. Catalytic Asymmetric Synthesis of Planar-Chiral Transition-Metal complexes. Tetrahedron Lett. 2015, 56, 1751–1761. 10.1016/j.tetlet.2015.01.130. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Lopez L. A.; Lopez E. Recent Advances in Transition Metal-Catalyzed C–H Bond Functionalization of Ferrocene Derivatives. Dalton. Trans. 2015, 44, 10128–10135. 10.1039/C5DT01373A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Zhu D.-Y.; Chen P.; Xia J.-B. Synthesis of Planar Chiral Ferrocenes by Transition-Metal Catalyzed Enantioselective C-H Activation. ChemCatChem 2016, 8, 68–73. 10.1002/cctc.201500895. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; d Gao D.-W.; Gu Q.; Zheng C.; You S.-L. Synthesis of Planar Chiral Ferrocenes via Transition-Metal-Catalyzed Direct C–H Bond Functionalization. Acc. Chem. Res. 2017, 50, 351–365. 10.1021/acs.accounts.6b00573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Sokolov V. I.; Troitskaya L. L.; Reutov O. A. Asymmetric Cyclopalladation of Dimethylaminomethylferrocene. J. Organomet. Chem. 1979, 182, 537–546. 10.1016/S0022-328X(00)83942-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Günay M. E.; Richards C. J. Synthesis of Planar Chiral Phosphapalladacycles by N-Acyl Amino Acid Mediated Enantioselective Palladation. Organometallics 2009, 28, 5833–5836. 10.1021/om9005356. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Zhang H.; Cui X.; Yao X.; Wang H.; Zhang J.; Wu Y. Directly Fused Highly Substituted Naphthalenes via Pd-Catalyzed Dehydrogenative Annulation of N,N-Dimethylaminomethyl Ferrocene Using a Redox Process with a Substrate. Org. Lett. 2012, 14, 3012–3015. 10.1021/ol301063k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Gao D.-W.; Shi Y.-C.; Gu Q.; Zhao Z.-L.; You S.-L. Enantioselective Synthesis of Planar Chiral Ferrocenes via PalladiumCatalyzed Direct Coupling with Arylboronic Acids. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 86–89. 10.1021/ja311082u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Pi C.; Li Y.; Cui X.; Zhang H.; Han Y.; Wu Y. Redox of Ferrocene Controlled Asymmetric Dehydrogenative Heck Reaction via Palladium-Catalyzed Dual C–H Bond Activation. Chem. Sci. 2013, 4, 2675–2679. 10.1039/c3sc50577d. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; f Shi Y.-C.; Yang R.-F.; Gao D.-W.; You S.-L. Enantioselective Synthesis of Planar Chiral Ferrocenes via Palladium-Catalyzed Annulation with Diarylethynes. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2013, 9, 1891–1896. 10.3762/bjoc.9.222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g Cheng G.-J.; Chen P.; Sun T.-Y.; Zhang X.; Yu J.-Q.; Wu Y.-D. A Combined IM-MS/DFT Study on [Pd(MPAA)]-Catalyzed Enantioselective C-H Activation: Relay of Chirality through a Rigid Framework. Chem. - Eur. J. 2015, 21, 11180–11188. 10.1002/chem.201501123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; h Xu J.; Liu Y.; Zhang J.; Xu X.; Jin Z. Palladium-Catalyzed Enantioselective C(sp2)–H Arylation of Ferrocenyl Ketones Enabled by a Chiral Transient Directing Group. Chem. Commun. 2018, 54, 689–692. 10.1039/C7CC09273C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Fukuzawa S.-i.; Yamamoto M.; Hosaka M.; Kikuchi S. Preparation of Chiral Homoannularly Bridged N,P-Ferrocenyl Ligands by Intramolecular Coupling of 1,5-Dilithioferrocenes and Their Application in Asymmetric Allylic Substitution Reactions. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2007, 2007, 5540–5545. 10.1002/ejoc.200700470. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Gao D.-W.; Yin Q.; Gu Q.; You S.-L. Enantioselective Synthesis of Planar Chiral Ferrocenes via Pd(0)Catalyzed Intramolecular Direct C–H Bond Arylation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 4841–4844. 10.1021/ja500444v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Deng R.; Huang Y.; Ma X.; Li G.; Zhu R.; Wang B.; Kang Y.- B.; Gu Z. Palladium-Catalyzed Intramolecular Asymmetric C–H Functionalization/Cyclization Reaction of Metallocenes: An Efficient Approach toward the Synthesis of Planar Chiral Metallocene Compounds. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 4472–4475. 10.1021/ja500699x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Ma X.; Gu Z. Palladium-Catalyzed Intramolecular Cp–H Bond Functionalization/Arylation: an Enantioselective Approach to Planar Chiral Quinilinoferrocenes. RSC Adv. 2014, 4, 36241–36244. 10.1039/C4RA07832B. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; e Liu L.; Zhang A.-A.; Zhao R.-J.; Li F.; Meng T.-J.; Ishida N.; Murakami M.; Zhao W.-X. Asymmetric Synthesis of Planar Chiral Ferrocenes by Enantioselective Intramolecular C–H Arylation of N-(2-Haloaryl)ferrocenecarboxamides. Org. Lett. 2014, 16, 5336–5338. 10.1021/ol502520b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f Gao D.-W.; Zheng C.; Gu Q.; You S.-L. Pd-Catalyzed Highly Enantioselective Synthesis of Planar Chiral Ferrocenylpyridine Derivatives. Organometallics 2015, 34, 4618–4625. 10.1021/acs.organomet.5b00730. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; g Gao D.-W.; Gu Y.; Wang S.-B.; Gu Q.; You S.-L. Palladium(0)-Catalyzed Asymmetric C–H Alkenylation for Efficient Synthesis of Planar Chiral Ferrocenes. Organometallics 2016, 35, 3227–3233. 10.1021/acs.organomet.6b00569. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; h Nottingham C.; Müller-Bunz H.; Guiry P. J. A Family of Chiral Ferrocenyl Diols:Modular Synthesis, Solid-State Characterization, and Application in Asymmetric Organocatalysis. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 11115–11119. 10.1002/anie.201604840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; i Luo S.; Xiong Z.; Lu Y.; Zhu Q. Enantioselective Synthesis of Planar Chiral Pyridoferrocenes via Palladium-Catalyzed Imidoylative Cyclization Reactions. Org. Lett. 2018, 20, 1837–1840. 10.1021/acs.orglett.8b00348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Ricci P.; Krämer K.; Cambeiro X. C.; Larrosa I. Arene–Metal π-Complexation as a Traceless Reactivity Enhancer for C–H Arylation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 13258–13261. 10.1021/ja405936s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Whitaker D.; Batuecas M.; Ricci P.; Larrosa I. A Direct Arylation-Cyclisation Reactionfor the Construction of Medium-Sized Rings. Chem. - Eur. J. 2017, 23, 12763–12766. 10.1002/chem.201703527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitaker D.; Burés J.; Larrosa I. Ag(I)-Catalyzed C–H Activation: The Role of the Ag(I) Salt in Pd/Ag Mediated C–H Arylation of Electron-Deficient Arenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 8384–8387. 10.1021/jacs.6b04726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comte V.; Tranchier J. P.; Rose-Munch F.; Rose E.; Perrey D.; Richard P.; Moïse C. Reactivity of Metallophosphide Anions with Electrophilic (Arene)tricarbonylmetal Complexes. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2003, 2003, 1893–1899. 10.1002/ejic.200200531. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ricci P.; Krämer K.; Larrosa I. Tuning Reactivity and Site Selectivity of Simple Arenes in C–H Activation: Ortho-Arylation of Anisoles via Arene–Metal π-Complexation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 18082–18086. 10.1021/ja510260j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- More optimization details can be found in the Supporting Information.

- a Wöste T. H.; Oestreich M. BINAP versus BINAP(O) in Asymmetric Intermolecular Mizoroki–Heck Reactions: Substantial Effects on Selectivities. Chem. - Eur. J. 2011, 17, 11914–11918. 10.1002/chem.201101695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Wöste T. H.; Oestreich M. Hemilabile BINAP(O) as a Chiral Ligand in Desymmetrizing Mizoroki–Heck Cyclizations. ChemCatChem 2012, 4, 2096–2101. 10.1002/cctc.201200300. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X.; Noboru S.. Method for making an optically active diphosphine ligand. Patent US5922918(A), October 24, 1997.

- Gladiali S.; Pulacchini S.; Fabbri D.; Manassero M.; Sansoni M. 2-Diphenylphosphino-2′-diphenylphosphinyl-1,1′-binaphthalene (BINAPO), an Axially Chiral Heterobidentate Ligand for Enantioselective Catalysis. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry 1998, 9, 391–395. 10.1016/S0957-4166(98)00009-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gladiali S.; Dore A.; Fabbri D. Novel Heterobidentate Ligands for Asymmetric Catalysis: Synthesis and Rhodium-catalysed Reactions of S-Alkyl (R)-2-Diphenylphosphino-l,l′-binaphthyl-2′-thiol. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry 1994, 5, 1143–1146. 10.1016/0957-4166(94)80141-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kurz L.; Lee G.; Morgans D.; Waldyke M. J.; Ward T. Stereospecific Functionalization of (R)-(−)-1,1′-Bi-2-naphthol Triflate. Tetrahedron Lett. 1990, 31, 6321–6324. 10.1016/S0040-4039(00)97053-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Berthod M.; Mignani G.; Woodward G.; Lemaire M. Modified BINAP: The How and the Why. Chem. Rev. 2005, 105, 1801–1836. 10.1021/cr040652w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lotz M. D.; Camasso N. M.; Canty A. J.; Sanford M. S. Role of Silver Salts in Palladium-Catalyzed Arene and Heteroarene C–H Functionalization Reactions. Organometallics 2017, 36, 165–171. 10.1021/acs.organomet.6b00437. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S. Y.; Hartwig J. F. Palladium-Catalyzed, Site-Selective Direct Allylation of Aryl C–H Bonds by Silver-Mediated C–H Activation: A Synthetic and Mechanistic Investigation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 15278–15284. 10.1021/jacs.6b10220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colletto C.; Panigrahi A.; Fernández-Casado J.; Larrosa I. Ag(I)–C–H Activation Enables Near-Room-Temperature Direct α-Arylation of Benzo[b]thiophenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 9638–9643. 10.1021/jacs.8b05361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- For examples on silver carboxylates ligated by a phosphine, see:; a Ng S. W.; Othman A. H. Silver Acetate-Triphenylphosphine Complexes. Acetatobis(triphenyl- phosphine)silver(I) and its Sesqui- hydrate, and Bis[acetato(triphenyl- phosphine)silver(I)] Hydrate and its Hemihydrate. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. C: Cryst. Struct. Commun. 1997, 53, 1396–1400. 10.1107/S0108270197006690. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Paramonov S. E.; Kuzmina N. P.; Troyanov S. I. Synthesis and Crystal Structure of Silver(I) Carboxylate Complexes, Ag(PnBu3)[C(CH3)3COO] and Ag(Phen)2[CF3COO]·H2O. Polyhedron 2003, 22, 837–841. 10.1016/S0277-5387(03)00011-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Partyka D. V.; Deligonul N. Phosphine- and Carbene-Ligated Silver Acetate: Easily-Accessed Synthons for Reactions with Silylated Nucleophiles. Inorg. Chem. 2009, 48, 9463–9475. 10.1021/ic901371g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruno N. C.; Niljianskul N.; Buchwald S. L. N-Substituted 2-Aminobiphenylpalladium Methanesulfonate Precatalysts and Their Use in C–C and C–N Cross-Couplings. J. Org. Chem. 2014, 79, 4161–4166. 10.1021/jo500355k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- For reviews, see:; a Semmelhack M. F.; Chlenov A. In Transition Metal Arene π-Complexes in Organic Synthesis and Cataysis; Kündig E. P., Ed.; Springer: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2004; pp 43–69. [Google Scholar]; For selected examples, see:; b Yamamoto Y.; Danjo H.; Yamaguchi K.; Imamoto T. Formation of 1,4-Diphosphinobenzenes via tele-Substitution on Fluorobenzenechromium Complexes. J. Organomet. Chem. 2008, 693, 3546–3552. 10.1016/j.jorganchem.2008.08.030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Shirakawa S.; Yamamoto K.; Maruoka K. Phase-Transfer-Catalyzed Asymmetric SNAr Reaction of α-Amino Acid Derivatives with Arene Chromium Complexes. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 838–840. 10.1002/anie.201409065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Kinoshita S.; Kamikawa K. Stereoselective Synthesis of N-Arylindoles and Related Compounds with Axially Chiral N–C Bonds. Tetrahedron 2016, 72, 5202–5207. 10.1016/j.tet.2015.11.053. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- See for example:; a RajanBabu T. V.; Casalnuovo A. L. Role of Electronic Asymmetry in the Design of New Ligands: The Asymmetric Hydrocyanation Reaction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1996, 118, 6325–6326. 10.1021/ja9609112. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Reetz M. T.; Beuttenmüller E. W.; Goddard R. First Enantioselective Catalysis using a Helical Diphosphane. Tetrahedron Lett. 1997, 38, 3211–3214. 10.1016/S0040-4039(97)00562-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Zhu G.; Cao P.; Jiang Q.; Zhang X. Highly Enantioselective Rh-Catalyzed Hydrogenations with a New Chiral 1,4-Bisphosphine Containing a Cyclic Backbone. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1997, 119, 1799–1800. 10.1021/ja9634381. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; d Pye J. P.; Rossen K.; Reamer R. A.; Tsou N. N.; Volante R. P.; Reider P. J. A New Planar Chiral Bisphosphine Ligand for Asymmetric Catalysis: Highly Enantioselective Hydrogenations under Mild Conditions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1997, 119, 6207–6208. 10.1021/ja970654g. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; e Pye P. J.; Rossen K.; Reamer R. A.; Volante R. P.; Reider P. J. [2.2]PHANEPHOS-Ruthenium(II) Complexes: Highly Active Asymmetric Catalysts for the Hydrogenation of β-Ketoesters. Tetrahedron Lett. 1998, 39, 4441–4444. 10.1016/S0040-4039(98)00842-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; f Jiang Q.; Jiang Y.; Xiao D.; Cao P.; Zhang X. Highly Enantioselective Hydrogenation of Simple Ketones Catalyzed by a Rh-PennPhos Complex. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 1998, 37, 1100–1103. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g Qiu L.; Wu J.; Chan S.; Au-Yeung T. T.-L.; Ji J.-X.; Guo R.; Pai C.-C.; Zhou Z.; Li X.; Fan Q.-H.; Chan A. S. C. Remarkably Diastereoselective Synthesis of a Chiral Biphenyl Diphosphine Ligand and Its Application in Asymmetric Hydrogenation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2004, 101, 5815–5820. 10.1073/pnas.0307774101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; h Li W.; Zhang X. In Phosphorus(III) Ligands in Homogeneous Catalysis: Design and Synthesis; Kamer P. C. J., van Leeuwen P. W. N. M., Eds; Wiley: Chichester, 2012; pp 27–80. [Google Scholar]; i Zhang R.; Xie B.; Chen G.-S.; Qiu L.; Chen Y.-X. Synthesis of Novel Chiral Biquinolyl Diphosphine Ligand and Its Applications in Palladium-Catalyzed Asymmetric Allylic Substitution Reactions. Tetrahedron Lett. 2016, 57, 845–848. 10.1016/j.tetlet.2016.01.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; j Sartorius F.; Trebing M.; Brückner C.; Brückner R. Reducing Diastereomorphous Bis(phosphaneoxide) Atropisomers to One Atropisomerically Pure Diphosphane: A New Ligand and a Novel Ligand-Preparation Design. Chem. - Eur. J. 2017, 23, 17463–17468. 10.1002/chem.201704800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; k Diehl neé Knobloch E.; Brückner R. Turning the Nitrogen Atoms of an Ar2P-CH2-N-N-CH2-PAr2 Motif into Uniquely Configured Stereocenters: A Novel Diphosphane Design for Asymmetric Catalysis. Chem. - Eur. J. 2018, 24, 3429–3433. 10.1002/chem.201706160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- For review and books, see:; a Whitesell J. K. C2 Symmetry and Asymmetric Induction. Chem. Rev. 1989, 89, 1581–1590. 10.1021/cr00097a012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Kagan H. B. In Asymmetric Synthesis; Morrison J. D., Ed.; Academic Press: Orlando, FL, 1985; Vol. 5, pp 1–39. [Google Scholar]; c Brunner H.; Zettlmeir W.. Handbook of Enantioselective Catalysis with Transition Metal Compounds; Vol. II; VCH: Weinheim, 1993. [Google Scholar]; d Noyori R.Asymmetric Catalysis in Organic Synthesis; Wiley: New York, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- a Inoguchi K.; Sakuraba S.; Achiwa K. Design Concepts for Developing Highly Efficient Chiral Bisphosphine Ligands in Rhodium-Catalyzed Asymmetric Hydrogenations. Synlett 1992, 1992, 169–178. 10.1055/s-1992-21306. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Togni A.; Breutel C.; Schnyder A.; Spindler F.; Landert H.; Tijani A. A Novel Easily Accessible Chiral Ferrocenyldiphosphine for Highly Enantioselective Hydrogenation, Allylic Alkylation, and Hydroboration Reactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1994, 116, 4062–4066. 10.1021/ja00088a047. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Yoshikawa K.; Yamamoto N.; Murata M.; Awano K.; Morimoto T.; Achiwa K. A New Type of Atropisomeric Biphenylbisphosphine Ligand, (R)-MOC-BIMOP and Its Use in Efficient Asymmetric Hydrogenation of α-Aminoketone and Itaconic Acid. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry 1992, 3, 13–16. 10.1016/S0957-4166(00)82304-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; d Cereghetti M.; Arnold W.; Broger E. A.; Rageot A. (R)- and (S).6,6′-Dimethyl- and 6,6′-Dimethoxy-2,2′-diiodo-l,l′-biphenyls: Versatile Intermediates for the Synthesis of Atropisomeric Diphosphine Ligands. Tetrahedron Lett. 1996, 37, 5347–5350. 10.1016/0040-4039(96)01090-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; e Franciò G.; Faraone F.; Leitner W. Asymmetric Catalysis with Chiral Phosphane/Phosphoramidite Ligands Derived from Quinoline (QUINAPHOS). Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2000, 39, 1428–1430. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.