Abstract

Zika virus (ZIKV) is a mosquito-borne flavivirus that has recently been responsible for a serious outbreak of disease in South and Central America. Infection with ZIKV has been associated with severe neurological symptoms and the development of microcephaly in unborn fetuses. Many of the regions involved in the current outbreak are known to be endemic for another flavivirus, dengue virus (DENV), which indicates that a large percentage of the population may have pre-existing DENV immunity. Thus, it is vital to investigate what impact pre-existing DENV immunity has on ZIKV infection. Here, we use primary human myeloid cells as a model for ZIKV enhancement in the presence of DENV antibodies. We show that sera containing DENV antibodies from individuals living in a DENV-endemic area are able to enhance ZIKV infection in a human macrophage-derived cell line and primary human macrophages. We also demonstrate altered pro-inflammatory cytokine production in macrophages with enhanced ZIKV infection. Our study indicates an important role for pre-existing DENV immunity on ZIKV infection in primary human immune cells and establishes a relevant in vitro model to study ZIKV antibody-dependent enhancement.

Keywords: Dengue immunity, Zika virus, antibody-dependent enhancement, macrophages, primary cell model

Introduction

Zika virus (ZIKV) is a rapidly emerging flavivirus that is spread primarily by the mosquito vector Aedes aegypti [1]. ZIKV can also be transmitted by Aedes albopictus, and this species is more widely distributed throughout the USA [2], though it is unclear at this time what impact ZIKV will have in the USA. Zika fever is similar to dengue fever, caused by dengue virus (DENV). Infection is characterized by mild headache, maculopapular rash, fever, malaise, conjunctivitis and joint pain [3]. There are no targeted therapeutics or prophylactic drugs, and treatment is generally palliative. No complications of Zika fever have been described until the recent outbreak that is currently spreading throughout the Western Hemisphere [4]. The current ZIKV outbreak in South America has been associated with a 20-fold increase in the rate of babies born with microcephaly – a neurodevelopmental disorder that is defined as a head circumference more than two standard deviations below the mean for age and sex [4, 5]. Newborns with microcephaly typically have significant neurological defects and seizures, and the degree of intellectual and functional disability is highly variable [6]. In addition, recent evidence also points to viral infection in the brain and a link between ZIKV infection and the development of Guillain–Barré syndrome [7–9].

The mosquito-borne flaviviruses, DENV1–4, yellow fever and West Nile, are important human pathogens in tropical American countries. The products of the adaptive immune response to a single DENV infection have been shown to both be protective and pathologic for a subsequent DENV infection [10, 11]. This increased disease severity has been related to antibody-enhanced infection of DENV in Fc-receptor bearing target host cells. Epidemiological studies suggest that antibodies to each of the four DENV and to Japanese encephalitis are capable of enhancing DENV infections. This phenomenon has been studied extensively in vitro and modelled in mice [12–15]. It has been previously shown that ZIKV infection can be enhanced by flaviviral antibodies in a mouse macrophage-derived cell line, P388D [10]. In addition, it was recently shown that DENV antibodies can enhance ZIKV in human cell lines and that ZIKV antibodies can enhance DENV infection in vitro [16–18]. Of note, is that the current ZIKV outbreak across Central and South America is in regions known to be endemic for DENV. This indicates that a large amount of the population likely have DENV antibodies, which may be capable of enhancing ZIKV infection in humans. ZIKV is genetically very close to the DENVs, which means surface proteins on Zika are likely quite similar to surface proteins on DENV, and the structure of the ZIKV envelope was recently shown to be quite similar to DENV [19, 20]. As macrophages are known to be involved in DENV antibody-dependent enhancement (ADE) [21] and it has been shown that ZIKV can infect placental macrophages [22], it is imperative that we examine DENV-antibody enhancement of ZIKV in primary human myeloid cells.

Here, we investigated the potential for human serum containing DENV antibodies to enhance ZIKV infection in a human macrophage-derived cell line as well as primary human macrophages/myeloid cells. We also evaluated levels of pro-inflammatory cytokine secreted during infection. Together, our findings demonstrate a critical role for dengue antibodies during ZIKV infection of primary human immune cells. These data establish a relevant in vitro model to further study ZIKV ADE and, together with the results of others, provides a warning regarding ZIKV infection in regions endemic for DENV and in administration of a DENV vaccine in areas likely to have a ZIKV epidemic.

Results

Dengue immune sera enhances ZIKV infection of human macrophages

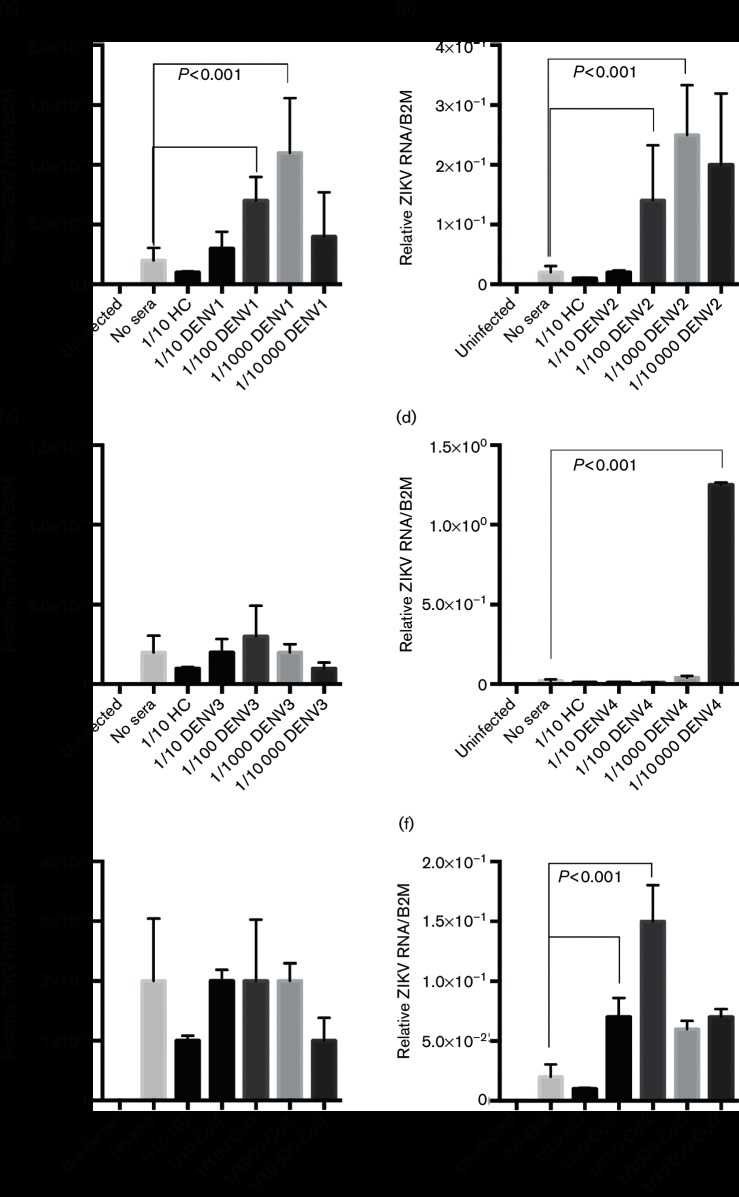

Macrophages are known targets of flavivirus infection and ADE during DENV infection. To investigate whether they play a role in possible ADE during ZIKV infection, we used U937, a macrophage-derived (myeloid) cell line, and isolated primary human macrophages. A schematic of our experimental procedure is shown in Fig. S1 (available in the online Supplementary Material). In our ADE assays, we used human sera from a DENV-endemic region in Colombia, South America, or pooled healthy controls (HC) from the USA (Table 1). The sera were classified as serotype confirmed (DENV1–4), or serotype unknown but positive for DENV antibodies (labeled COL1 and COL2) or DENV-naïve (pooled HC). All sera containing DENV antibodies were able to neutralize DENV1–4 and ZIKV in a plaque reduction neutralization-50 assay. For the ADE experiments, ZIKV MR766 was incubated with dilutions of sera ranging from 1 : 10 to 1 : 10 000 and the virus–sera mixtures were then added to cultured macrophage-derived U937 cells. At 48 hours post-infection (p.i.), cells were lysed for RNA isolation. The RNA was used in quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) analysis to quantify ZIKV infection. We found that sera containing DENV antibodies from most groups enhanced ZIKV infection in U937 cells, at varying levels (Fig. 1).

Table 1.

Dengue patient sera characterization

| ELISA results* | qRT-PCR results* | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Serum ID | Age | Sex | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| DENV1 | 31 | M | +++ | ++ | − | + | + | − | − | − |

| DENV2 | 11 | M | + | +++ | − | + | − | + | − | − |

| DENV3 | 1 | F | + | + | ++ | + | − | − | + | − |

| DENV4 | 3 | M | + | + | − | +++ | − | − | − | + |

*ELISA and qRT-PCR positive (+) and negative (−) results are listed by DENV serotype (1–4).

Fig. 1.

DENV immune sera enhances ZIKV infection in human macrophage-derived cells. Human sera containing DENV antibodies (DENV1–4 are serotype confirmed, Col are serotype unknown), or HC were diluted 1 : 10–1 : 10 000 and incubated with ZIKV. Sera are described in Table 1. U937 human macrophage-derived cells were infected with either ZIKV alone or the ZIKV–sera mixtures. (a) DENV1 antibody-containing sera; (b) DENV2 antibody-containing sera; (c) DENV3 antibody-containing sera; (d) DENV4 antibody-containing sera; (e) DENV-antibody sera from Colombian individual 1; (f) DENV-antibody sera from Colombian individual 2. Infection was measured by qRT-PCR analysis at 48 hours p.i. Both infections and qRT-PCR analysis were done in triplicate. Technical and biological replicates were done in triplicate. Data are pooled and error bars indicate standard deviation. Student's t-test and multiple comparison ANOVA were used for statistical analysis. *P<0.001.

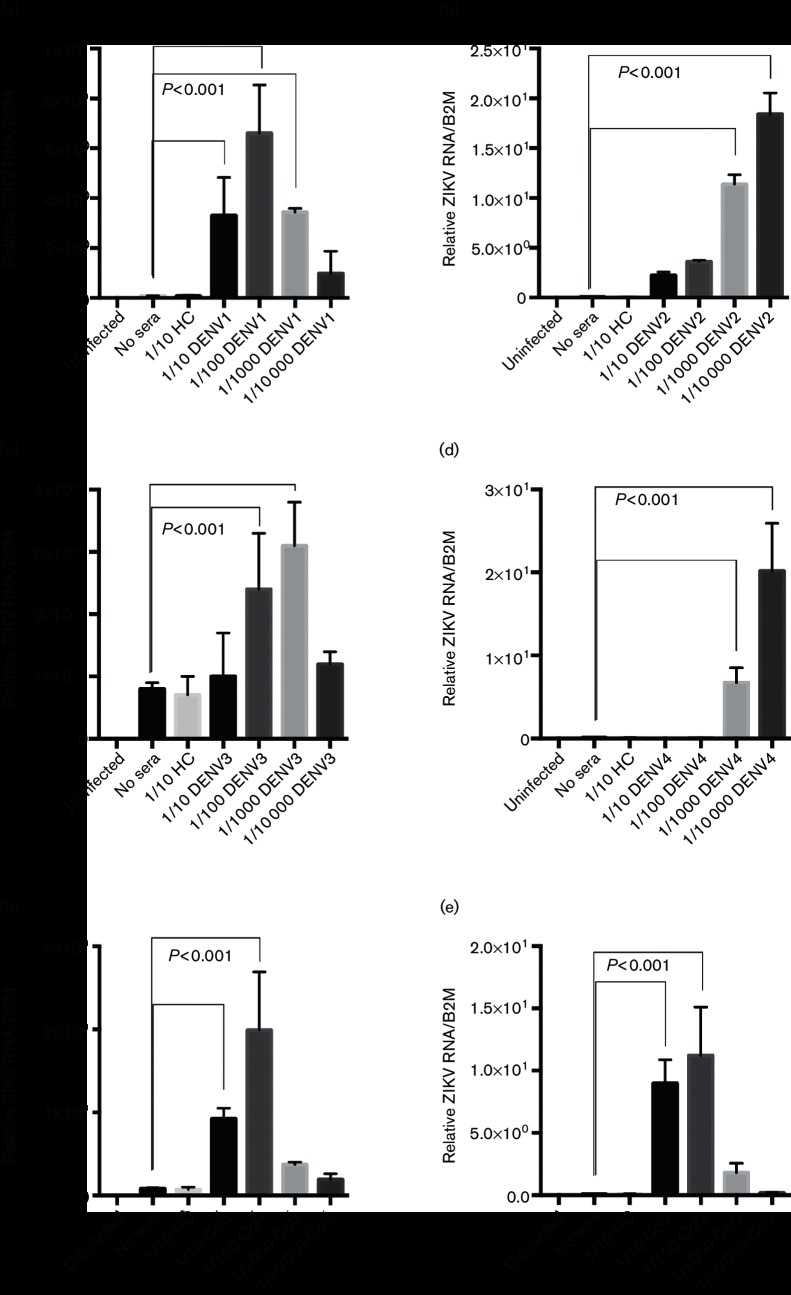

We next wished to validate the ZIKV ADE seen with DENV sera in primary human macrophage cells. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were purified from fresh blood as described in Methods. Human macrophages were isolated as described in Methods and experiments were done on day 6 of isolation. ZIKV MR766 was again incubated with dilutions of human sera ranging from 1 : 10 to 1 : 10 000 and the virus–sera mixtures were then added to cultured primary human macrophages. At 48 hours p.i., cells were lysed for RNA isolation. Supernatants were stored at −80 °C for future assays. The RNA was used in qRT-PCR analysis to quantify ZIKV infection. We again found that sera containing DENV antibodies from all groups significantly enhanced ZIKV infection in human macrophages (Figs 2 and S2). In addition, immunofluorescence staining at 24 hours p.i. revealed that a greater number of cells were infected with ZIKV in the presence of DENV-immune sera than with the virus alone (Fig. S3). We next used a ZIKV strain from the recent outbreak associated with Puerto Rico (PRVABC59) in our ADE assay to investigate possible differences between ‘African’ and ‘Asian’ strains. Although infection was less robust with PRVABC59 than ZIKV MR766, as is usual for this strain, we saw similar enhancement of ZIKV infection in the presence of DENV-immune sera (Fig. S4).

Fig. 2.

DENV immune sera enhances ZIKV infection in primary human macrophages. Human sera containing DENV antibodies (DENV1–4 are serotype confirmed, Col are serotype unknown), or HC were diluted 1 : 10–1 : 10 000 and incubated with ZIKV. Sera are described in Table 1. Primary isolated human macrophages were infected with either ZIKV alone or the ZIKV–sera mixtures. (a) DENV1 antibody-containing sera; (b) DENV2 antibody-containing sera; (c) DENV3 antibody-containing sera; (d) DENV4 antibody-containing sera; (e) DENV-antibody sera from Colombian individual 1; (f) DENV-antibody sera from Colombian individual 2. Infection was measured by qRT-PCR analysis at 48 hours p.i. Technical and biological replicates were done in triplicate. Data are pooled and error bars indicate standard deviation. Student's t-test and ANOVA were used for statistical analysis. *P<0.001.

Infection with ZIKV–dengue antibody immune complexes alters pro-inflammatory cytokine production

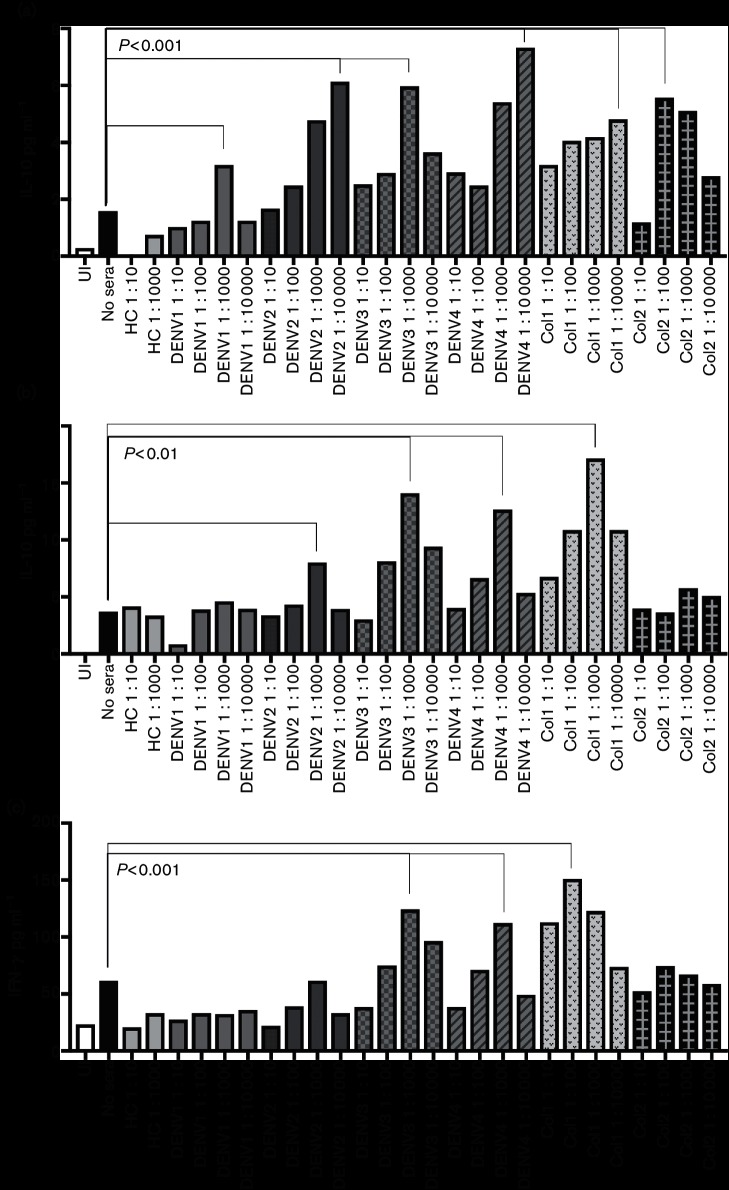

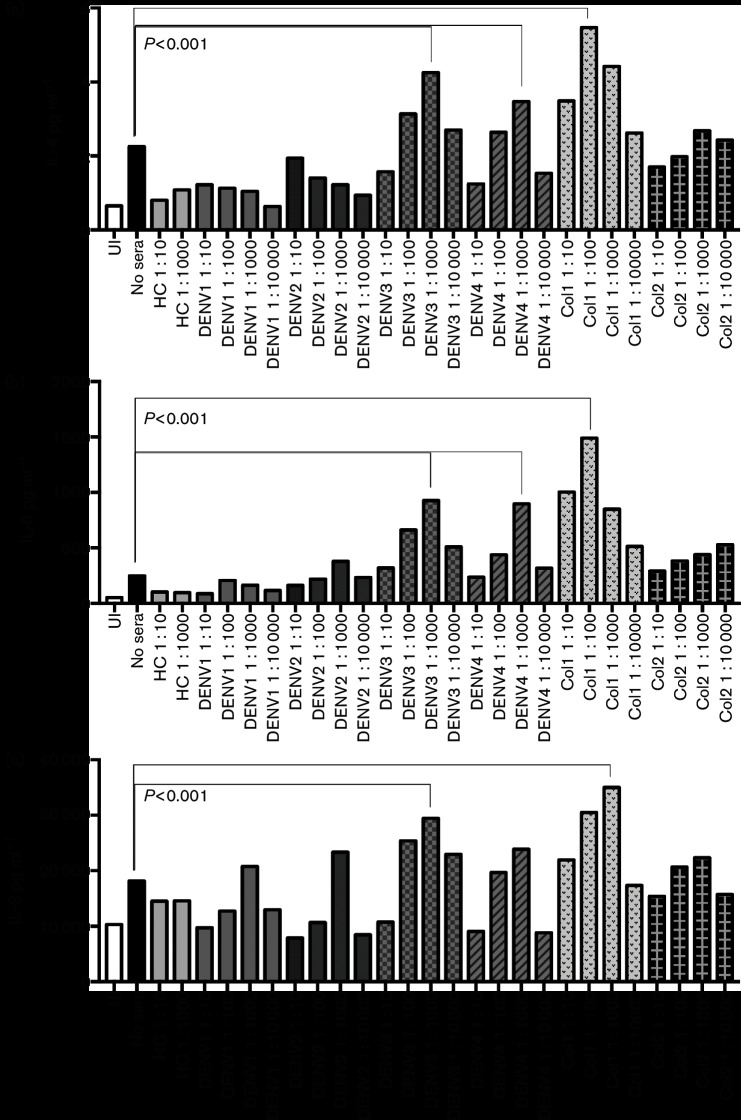

Altered expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines is a hallmark of ADE during DENV infection of human immune cells such as macrophages [23]. Accordingly, we measured a panel of inflammatory cytokines in the supernatant of our ZIKV-infected primary human macrophages, with and without incubation in the presence of DENV immune sera. The cytokines measured were interleukins IL-2, IL-4, IL-6, IL-8, IFN-gamma, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-alpha and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), using a magnetic bead Bioplex kit (Bio-Rad). We found that exposure to at least one dilution of serum containing antibodies recognizing at least one serotype of DENV resulted in an increase of each inflammatory cytokinetested as compared to infection with ZIKV alone (Figs 3, 4 and S5). Exposure to sera containing antibodies to DENV3 had the greatest effect on cytokine production, resulting in an increase of IL-10 from 1.58 to 5.97 pg ml−1 and IFN-gamma from 61.63 to 124.18 pg ml−1 in the presence of a 1 : 1000 dilution of DENV3-antibody sera as compared to infection with ZIKV alone. All sera containing DENV antibodies resulted in increased expression of inflammatory cytokines, which was expected as we saw ZIKV infection enhancement in the presence of these sera.

Fig. 3.

Dengue ADE of ZIKV infection alters levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines released by human macrophages. Human sera containing DENV antibodies, or HC sera, were diluted 1 : 10–1 : 10 000 and incubated with ZIKV. Sera are described in Table 1. Primary isolated human macrophages were infected with either ZIKV alone or the ZIKV–sera mixtures. Supernatants were collected at 48 hours p.i. and used in a Bio-Plex assay to measure levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines. Data were analysed using Data Pro software and one-way ANOVA was used for statistical analysis. P values are indicated for the most significant variation for each serum category. (a) IL10; (b) GM-CSF; (c) IFN-gamma.

Fig. 4.

Dengue ADE of ZIKV infection alters levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines released by human macrophages. Human sera containing DENV antibodies, or HC sera, were diluted 1 : 10–1 : 10 000 and incubated with ZIKV. Sera are described in Table 1. Primary isolated human macrophages were infected with either ZIKV alone or the ZIKV–sera mixtures. Supernatants were collected at 48 hours p.i. and used in a Bio-Plex assay to measure levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines. Data were analysed using Data Pro software and one-way ANOVA was used for statistical analysis. P values are indicated for the most significant variation for each serum category. (a) IL-4; (b) IL-6; (c) IL-8.

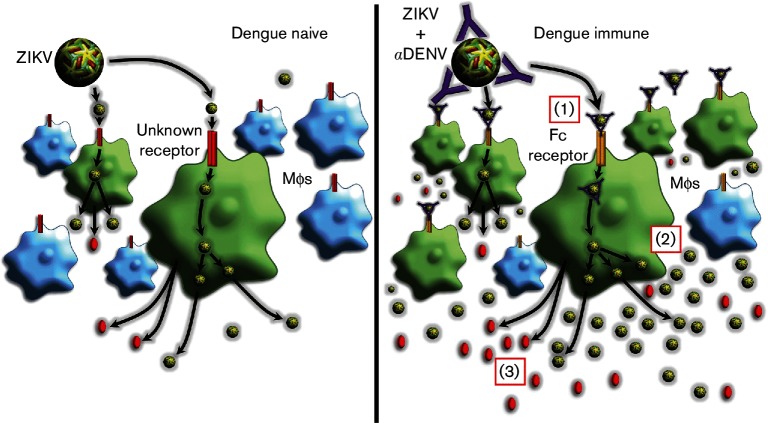

In summary, our studies have established a model of ADE for ZIKV infection using DENV patient sera and human macrophage cells, and evaluated the impact of ADE during ZIKV infection on pro-inflammatory cytokine production by human macrophages. A graphic illustration of our conclusions is shown in Fig. 5.

Fig. 5.

Graphical abstract of ADE of ZIKV by dengue antibodies. Left panel: ZIKV infection in dengue naïve individuals (no antibodies to DENV are present). Right panel: ZIKV infection in dengue immune individuals (antibodies to DENV are present). (1) Antibodies in dengue immune sera allow ZIKV entry into macrophages via the Fc-gamma receptor. In addition, more individual macrophages are infected in the presence of DENV antibody (green cells). (2) Entry via ADE results in higher virus replication and/or production in the macrophages (green circles). (3) Macrophages infected via ADE produce higher amounts of pro-inflammatory cytokines (red circles) than cells infected with Zika alone.

Discussion

This is the first study, to our knowledge, to investigate the potential for ADE of ZIKV by antibodies in dengue patient immune sera in primary human myeloid cells, an ideal model system for the investigation of flaviviral ADE. There has recently been a substantial increase in the association of ZIKV infection with neurological complications and severity of neurological involvement [24, 25]. Very little is currently known about ZIKV infection in primary human immune cells such as monocytes or macrophages, or in nervous system cells such as microglia and neurons. In addition, there is little known about the interactions and effects of ZIKV infection in the presence of pre-existing flavivirus immunity, which is of great importance given the current ZIKV outbreak in dengue-endemic regions of South and Central America and the associated neurological complications. As the current outbreak in the Americas is in a DENV endemic area, the contribution of pre-existing DENV immunity to ZIKV severity and severe neurological involvement needs to be investigated. Several groups have recently published on the ability of DENV antibodies to interact with, bind and/or enhance ZIKV infection [16, 17, 20, 26–28]. This is the first study to look at the ability of DENV antibodies to enhance ZIKV infection in primary human immune cells. Our results add to the growing body of evidence indicating the importance of pre-existing flavivirus immunity in ZIKV infection and provide data useful for ZIKV treatment and flavivirus vaccine development.

We saw enhancement of ZIKV infection in human macrophages in the presence of sera containing antibodies that recognized each of the four serotypes of DENV. We also saw interesting variation of enhancement between serotype-specific antibodies, with DENV2 and DENV4 patient sera having the most significant enhancement of ZIKV infection in primary macrophages, though more samples need to be tested to conclusively determine a serotype-based difference. For now, we can conclude that antibodies from any DENV serotype are able to enhance ZIKV infection in primary human myeloid cells, which is in agreement with previous studies using DENV patient plasma in the U937 cell line [26] and patient sera in the K562 cell line [29]. If further evidence does support variation in enhancement due to DENV serotype, this could be due to differences/similarities between ZIKV and that serotype. This could also be attributed to the amount of antibody and timing of DENV infection in the individual serum samples or other variables, such as sex or age. Further research must be done in order to fully characterize the ability of various DENV serotype antibodies to bind and enhance ZIKV infection, especially with regards to monotypic or multitypic antibody sera. In recent years, there has been increased epidemic activity and geographic expansion of DENV, with cases occurring in Asia, the Americas, Africa, and Pacific and Mediterranean regions [30–33]. In addition, there have been recent outbreaks in Texas and Florida where transmission occurred on American soil [34, 35]. Our preliminary results, as well as the results of others [16, 18, 27], suggest that a ZIKV outbreak in a region where DENV is either endemic or sporadic could result in rapid transmission and more severe cases. These data also indicate that ZIKV transmission and severity in a DENV endemic area may both be increased as compared to a non-endemic region.

Macrophages are known to be primary targets during DENV and other flavivirus infections, have been shown to be readily infected with ZIKV, and are presumed to be major targets during ZIKV infection [22, 36, 37]. In addition, during ADE of DENV, macrophages play a key role in allowing the immune complexes to infect and in the resulting enhancement [21, 38]. Several studies have demonstrated both DENV ADE and altered pro-inflammatory cytokine production, such as of IL-10, during DENV ADE in U937 cells as well as in primary human macrophages [23, 39–41]. In a study of U937 cells, there was an increase in IL-6, IL-12p70 and TNF-alpha, as well as prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) during DENV ADE as compared to cells that were directly infected [38]. We found that all eight inflammatory cytokines examined in our studies (IL-2, IL-4, IL-6, IL-8, IFN-gamma, TNF-alpha and GM-CSF) were increased to some extent during ZIKV ADE with at least one dilution of DENV patient sera. More work remains to be done both to characterize the inflammatory profile during mild and severe ZIKV infection, during ZIKV infection with neurological complications, and during ADE of ZIKV infection by pre-existing DENV immunity.

In immune cells, flaviviral ADE is mediated via the Fc-gamma receptor uptake of immune complexes. Many neuronal cells also have Fc receptors. In fact, Fc-receptor-mediated endocytosis and the endosome/autophagosome systems have been previously described in antibody-mediated brain pathology [42]. Recent studies have shown that ADE during DENV infection can upregulate cellular autophagy as a mechanism to suppress the activation of early antiviral responses [43]. Antibody immune complexes have also been identified inside neural lysosomes, suggesting the involvement of the endosome/lysosome pathway in antibody-mediated clearance of immune aggregates [42, 44, 45]. This suggests that the uptake of DENV antibody–viral antigen immune complexes by Fc receptors might be possible in the presence of pre-existing DENV immunity, resulting in ADE during ZIKV infection in Fc-bearing cells such as neural cells. Further research remains to be done on this, especially to examine whether the antibody-opsonized virus can cross the blood–brain barrier. Additionally, DENV uses autophagic machinery for viral replication in certain non-immune cells (i.e. liver) suggesting that the double-membrane autophagosome could be a scaffold for flaviviral RNA replication [46]. It is possible that a similar mechanism could be involved in ZIKV infection and enhancement in neuronal cells.

An important consideration in light of the findings here and from others is the recent approval of the Sanofi Pasteur tetravalent dengue vaccine (Dengvaxia) in several DENV endemic regions. It is unknown what role this vaccine will have on ZIKV infection in those individuals. The vaccine elicits antibodies against four DENV serotypes, which we show here can enhance ZIKV infection in human macrophages. Dengvaxia is recommended by the WHO for limited use in regions that are highly endemic for DENV infection [47]. However, in light of evidence that DENV antibodies can enhance ZIKV infection, more exploratory studies must be done to assess the risk of DENV vaccination for future ZIKV infections, especially with regards to neurological consequences. An important future direction is to characterize the role of pre-existing DENV immunity on ZIKV infection in neuronal cells.

In conclusion, our study establishes a relevant in vitro human primary myeloid/macrophage cell model for ZIKV ADE that can be used to further examine this phenomenon. Our results demonstrate that previous DENV infection can play an important role in ZIKV infection of human immune cells. We present novel data showing that patient sera containing antibodies against each of the four serotypes of DENV are able to enhance ZIKV infection and alter the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines in primary human macrophages. Overall, our data establish ADE during ZIKV infection in an accepted DENV ADE model. Further studies must be done to validate these results in vivo.

Methods

Cell line

Cells from the human myelomonocytic cell line U937 (ATCC CRL-1593.2) were grown in RPMI 1640 complete medium with 10 % FBS at 37 °C with 5 % CO2.

Primary human macrophages

Institutional Review Board (IRB)-exempt approval for the collection of human PBMCs from healthy volunteers was granted by the University of South Carolina IRB in 2015. Briefly, 20 ml of blood was obtained from healthy, anonymized volunteers and processed immediately. Human PBMCs were isolated using Lymphoprep and SepMate (Stemcell Technologies) and stored at −80 °C until use. PBMC aliquots were cultured for 1 h at 37 °C. After washing, adherent cells were cultured at 37 °C in complete medium 10 % RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 50 ng ml−1 recombinant human macrophage colony stimulation factor (rhM-CSF) to allow differentiation into macrophages. After five days of culture, 1 ml of 50 ng ml−1 rhM-CSF was added to the culture. Macrophages were harvested for experiments on day 6. All blood was tested by ELISA to confirm that flavivirus-naïve cells were used for ZIKV infection experiments.

Human serum samples

Serum samples from a cohort obtained from participants living in Colombia – Norte de Santander, South America – were included in this study. Collection of samples was approved by IRBs at Universidad de Pamplona (Colombia, South America) and Los Patios Hospital [48] and were provided as unidentified, anonymized samples. Samples were de-identified and investigators had no access to patient information or identifiers. All human sera were carefully tested by ELISA and qRT-PCR to characterize them as DENV-antibody positive (serotype-specific or unspecific) or DENV negative (see Table 1). ELISA testing was done using serotype-specific whole virions and human IgG-HRP, and qRT-PCR was done using primers specific to each serotype of DENV. A strong advantage of this serum collection is that all sera were obtained before the recent introduction of ZIKV and all serum samples tested negative for ZIKV by ELISA and qRT-PCR. All sera containing DENV antibodies were able to neutralize DENV1–4 and ZIKV in standard plaque reduction neutralization-50 assays.

ZIKV propagation

ZIKV strain MR766 (BEI Resources, NR-50065) and PRVABC59 (a kind gift of Dr Stephen Higgs, KSU) were used for all infection studies. ZIKV stocks were propagated in C6/36 cells, as is routinely done in our laboratory for all flaviviruses, as previously described [49, 50]. Briefly, the virus was added to cells for infection at a multiplicity of infection (m.o.i.) of 1.0. Cell supernatant was collected when cytopathic effect (c.p.e.) was greater than 80 %, which is typically within 8 days. Supernatant was centrifuged and virus stocks stored at −80 °C until use. Virus titres were determined by plaque assay on Vero cells (ATCC).

ZIKV infection and ADE model

The ADE assays were performed as described elsewhere [43]. Briefly, human serum serial dilutions were mixed with each ZIKV isolate and incubated for 1 h at 37 °C with 5 % CO2 to allow the formation of immune complexes. Complexes were added to cells (U937 or human primary macrophages) at a final m.o.i. of 0.1 and incubated for 2 h at 37 °C. Cells were washed twice with 1× Dulbecco's phosphate-buffered saline to remove any remaining virus or immune complexes and incubated with fresh media. Experiments were stopped at time points indicated in figure legends. Gene expression analysis was done on isolated RNA to measure ZIKV infection by qRT-PCR using published probes [51].

qRT-PCR analysis

Briefly, total RNA from cells was isolated using the RNeasy kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Qiagen). qRT-PCR was conducted using the QuantiFast SYBR Green RT-PCR kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Qiagen). We used previously published primers for detection of ZIKV RNA and normalized data to human B2M housekeeping gene [51].

Immunofluorescence

For staining, cells were fixed in 4 % paraformaldehyde for 20 min at room temperature, washed with PBS(−) and then labelled for infection using 4G2 anti-flavivirus antibody (MAB10216, Millipore) and an appropriate FITC secondary antibody, as indicated in the figure legends. DAPI was used to counterstain. Representative images are shown.

Inflammatory cytokine expression levels

Infected cell culture supernatant was used to quantify the secretion of indicated cytokines using the Magnetic Multiplex Immunoassay Pro-Inflammatory 8-Plex System according to the manufacturer’s instructions (M50000007A, Bio-Rad).

Supplementary Data

Supplementary File 1

Funding information

The work in this study was supported by the National Institutes of Health (1K22 AI103067) and funding from the University of South Carolina School of Medicine, Department of Pathology, Microbiology and Immunology.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Norte de Santander Community, The Colombian Administrative Department of Science, Technology and Innovation (Colciencias) and the University of Pamplona for supporting the current research. We also thank Dr Carole Oskeritzian and Ms Piper Wedmen at the University of South Carolina School of Medicine for the use of equipment and experimental insights.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical statement

Collection of samples was approved by Institutional Review Boards at Universidad de Pamplona (Colombia, South America) and Los Patios Hospital [48] and were provided as unidentified, anonymized samples. Samples were de-identified and investigators had no access to patient information or identifiers. Some of these data have been presented in a preliminary form at The American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene Annual Meeting in Atlanta, GA, in November 2016.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: ADE, antibody-dependent enhancement; DENV, dengue virus; GM-CSF, granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor; HC, healthy controls; p.i., post-infection; PBMCS, peripheral blood mononuclear cells; qRT-PCR, polymerase chain reaction; ZIKV, Zika virus.

Five supplementary figures are available with the online Supplementary Material.

References

- 1.Hayes EB. Zika virus outside Africa. Emerg Infect Dis. 2009;15:1347–1350. doi: 10.3201/eid1509.090442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grard G, Caron M, Mombo IM, Nkoghe D, Mboui Ondo S, et al. Zika virus in Gabon (Central Africa) – 2007: a new threat from Aedes albopictus? PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2014;8:e2681. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fauci AS, Morens DM. Zika virus in the Americas—yet another Arbovirus threat. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:601–604. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1600297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Oliveira Melo AS, Malinger G, Ximenes R, Szejnfeld PO, Alves Sampaio S, et al. Zika virus intrauterine infection causes fetal brain abnormality and microcephaly: tip of the iceberg? Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2016;47:6–7. doi: 10.1002/uog.15831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schuler-Faccini L, Ribeiro EM, Feitosa IM, Horovitz DD, Cavalcanti DP, et al. Possible association between Zika virus infection and microcephaly — Brazil, 2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65:59–62. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6503e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Staples JE, Dziuban EJ, Fischer M, Cragan JD, Rasmussen SA, et al. Interim guidelines for the evaluation and testing of Infants with possible congenital Zika virus infection — United States, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65:63–67. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6503e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Martines RB, Bhatnagar J, Keating MK, Silva-Flannery L, Muehlenbachs A, et al. Notes from the field: evidence of Zika virus infection in brain and placental tissues from two congenitally infected newborns and two fetal losses — Brazil, 2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65:159–160. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6506e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Oehler E, Watrin L, Larre P, Leparc-Goffart I, Lastere S, et al. Zika virus infection complicated by Guillain-Barre syndrome – case report, French Polynesia, December 2013. Euro Surveill. 2014;19:20720. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES2014.19.9.20720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wise J. Study links Zika virus to Guillain-Barré syndrome. BMJ. 2016;352:i1242. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i1242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fagbami AH, Halstead SB, Marchette NJ, Larsen K. Cross-infection enhancement among African flaviviruses by immune mouse ascitic fluids. Cytobios. 1987;49:49–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Halstead SB, Porterfield JS, O'Rourke EJ. Enhancement of dengue virus infection in monocytes by flavivirus antisera. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1980;29:638–642. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1980.29.638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Morens DM, Halstead SB, Marchette NJ. Profiles of antibody-dependent enhancement of dengue virus type 2 infection. Microb Pathog. 1987;3:231–237. doi: 10.1016/0882-4010(87)90056-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Costa VV, Fagundes CT, Valadão DF, Ávila TV, Cisalpino D, et al. Subversion of early innate antiviral responses during antibody-dependent enhancement of dengue virus infection induces severe disease in immunocompetent mice. Med Microbiol Immunol. 2014;203:231–250. doi: 10.1007/s00430-014-0334-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Balsitis SJ, Williams KL, Lachica R, Flores D, Kyle JL, et al. Lethal antibody enhancement of dengue disease in mice is prevented by Fc modification. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:e1000790. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Halstead SB, Mahalingam S, Marovich MA, Ubol S, Mosser DM. Intrinsic antibody-dependent enhancement of microbial infection in macrophages: disease regulation by immune complexes. Lancet Infect Dis. 2010;10:712–722. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(10)70166-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Priyamvada L, Quicke KM, Hudson WH, Onlamoon N, Sewatanon J, et al. Human antibody responses after dengue virus infection are highly cross-reactive to Zika virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2016;113:7852–7857. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1607931113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stettler K, Beltramello M, Espinosa DA, Graham V, Cassotta A, et al. Specificity, cross-reactivity, and function of antibodies elicited by Zika virus infection. Science. 2016;353:823–826. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf8505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kawiecki AB, Christofferson RC. Zika virus–induced antibody response enhances dengue virus serotype 2 replication in vitro . J Infect Dis. 2016;214:1357–1360. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiw377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dai L, Song J, Lu X, Deng YQ, Musyoki AM, et al. Structures of the Zika virus envelope protein and its complex with a flavivirus broadly protective antibody. Cell Host Microbe. 2016;19:696–704. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2016.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barba-Spaeth G, Dejnirattisai W, Rouvinski A, Vaney MC, Medits I, et al. Structural basis of potent Zika–dengue virus antibody cross-neutralization. Nature. 2016;536:48–53. doi: 10.1038/nature18938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Halstead SB. Dengue antibody-dependent enhancement: knowns and unknowns. Microbiol Spectr. 2014;2 doi: 10.1128/microbiolspec.AID-0022-2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Quicke KM, Bowen JR, Johnson EL, McDonald CE, Ma H, et al. Zika virus infects human placental macrophages. Cell Host Microbe. 2016;20:83–90. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2016.05.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen RF, Wang L, Cheng JT, Yang KD. Induction of IFNα or IL-12 depends on differentiation of THP-1 cells in dengue infections without and with antibody enhancement. BMC Infect Dis. 2012;12:340. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-12-340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cao-Lormeau VM, Blake A, Mons S, Lastère S, Roche C, et al. Guillain-Barré syndrome outbreak associated with Zika virus infection in French Polynesia: a case-control study. Lancet. 2016;387:1531–1539. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00562-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Araúz D, de Urriola L, Jones J, Castillo M, Martínez A, et al. Febrile or exanthematous illness associated with Zika, dengue, and chikungunya viruses, Panama. Emerg Infect Dis. 2016;22:1515–1517. doi: 10.3201/eid2208.160292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dejnirattisai W, Supasa P, Wongwiwat W, Rouvinski A, Barba-Spaeth G, et al. Dengue virus sero-cross-reactivity drives antibody-dependent enhancement of infection with Zika virus. Nat Immunol. 2016;17:1102–1108. doi: 10.1038/ni.3515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Harrison SC. Immunogenic cross-talk between dengue and Zika viruses. Nat Immunol. 2016;17:1010–1012. doi: 10.1038/ni.3539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Swanstrom JA, Plante JA, Plante KS, Young EF, McGowan E, et al. Dengue virus envelope dimer epitope monoclonal antibodies isolated from dengue patients are protective against Zika virus. MBio. 2016;7:e01123-16. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01123-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Paul LM, Carlin ER, Jenkins MM, Tan AL, Barcellona CM, et al. Dengue virus antibodies enhance Zika virus infection. Clin Transl Immunology. 2016;5:e117. doi: 10.1038/cti.2016.72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gubler DJ. Epidemic dengue/dengue hemorrhagic fever as a public health, social and economic problem in the 21st century. Trends Microbiol. 2002;10:100–103. doi: 10.1016/S0966-842X(01)02288-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Burke DS, Kliks S. Antibody-dependent enhancement in dengue virus infections. J Infect Dis. 2006;193:601–603. doi: 10.1086/499282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mackenzie JS, Gubler DJ, Petersen LR. Emerging flaviviruses: the spread and resurgence of Japanese encephalitis, West Nile and dengue viruses. Nat Med. 2004;10:S98–S109. doi: 10.1038/nm1144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Guzman MG, Halstead SB, Artsob H, Buchy P, Farrar J, et al. Dengue: a continuing global threat. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2010;8:S7–S16. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Murray KO, Rodriguez LF, Herrington E, Kharat V, Vasilakis N, et al. Identification of dengue fever cases in Houston, Texas, with evidence of autochthonous transmission between 2003 and 2005. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2013;13:835–845. doi: 10.1089/vbz.2013.1413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Muñoz-Jordán JL, Santiago GA, Margolis H, Stark L. Genetic relatedness of dengue viruses in Key West, Florida, USA, 2009-2010. Emerg Infect Dis. 2013;19:652–654. doi: 10.3201/eid1904.121295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hall WC, Crowell TP, Watts DM, Barros VL, Kruger H, et al. Demonstration of yellow fever and dengue antigens in formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded human liver by immunohistochemical analysis. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1991;45:408–417. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1991.45.408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bhoopat L, Bhamarapravati N, Attasiri C, Yoksarn S, Chaiwun B, et al. Immunohistochemical characterization of a new monoclonal antibody reactive with dengue virus-infected cells in frozen tissue using immunoperoxidase technique. Asian Pac J Allergy Immunol. 1996;14:107–113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Puerta-Guardo H, Raya-Sandino A, González-Mariscal L, Rosales VH, Ayala-Dávila J, et al. The cytokine response of U937-derived macrophages infected through antibody-dependent enhancement of dengue virus disrupts cell apical-junction complexes and increases vascular permeability. J Virol. 2013;87:7486–7501. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00085-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tsai TT, Chuang YJ, Lin YS, Chang CP, Wan SW, et al. Antibody-dependent enhancement infection facilitates dengue virus-regulated signaling of IL-10 production in monocytes. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2014;8:e3320. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0003320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rolph MS, Zaid A, Rulli NE, Mahalingam S. Downregulation of interferon-β in antibody-dependent enhancement of dengue viral infections of human macrophages is dependent on interleukin-6. J Infect Dis. 2011;204:489–491. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jir271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dong T, Moran E, Vinh Chau N, Simmons C, Luhn K, et al. High pro-inflammatory cytokine secretion and loss of high avidity cross-reactive cytotoxic T-cells during the course of secondary dengue virus infection. PLoS One. 2007;2:e1192. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Krishnamurthy PK, Deng Y, Sigurdsson EM. Mechanistic studies of antibody-mediated clearance of Tau aggregates using an ex vivo brain slice model. Front Psychiatry. 2011;2:59. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2011.00059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Huang X, Yue Y, Li D, Zhao Y, Qiu L, et al. Antibody-dependent enhancement of dengue virus infection inhibits RLR-mediated Type-I IFN-independent signalling through upregulation of cellular autophagy. Sci Rep. 2016;6:22303. doi: 10.1038/srep22303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Masliah E, Rockenstein E, Adame A, Alford M, Crews L, et al. Effects of α-synuclein immunization in a mouse model of Parkinson's disease. Neuron. 2005;46:857–868. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tampellini D, Magrané J, Takahashi RH, Li F, Lin MT, et al. Internalized antibodies to the Aβ domain of APP reduce neuronal Aβ and protect against synaptic alterations. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:18895–18906. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M700373200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jackson WT, Giddings TH, Jr, Taylor MP, Mulinyawe S, Rabinovitch M, et al. Subversion of cellular autophagosomal machinery by RNA viruses. PLoS Biol. 2005;3:e156. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Govindarajan D, Guan L, Meschino S, Fridman A, Bagchi A, et al. A rapid and improved method to generate recombinant dengue virus vaccine candidates. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0152209. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0152209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Londono-Renteria B, Drame PM, Weitzel T, Rosas R, Gripping C, et al. An. gambiae gSG6-P1 evaluation as a proxy for human-vector contact in the Americas: a pilot study. Parasit Vectors. 2015;8:533. doi: 10.1186/s13071-015-1160-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Colpitts TM, Cox J, Nguyen A, Feitosa F, Krishnan MN, et al. Use of a tandem affinity purification assay to detect interactions between West Nile and dengue viral proteins and proteins of the mosquito vector. Virology. 2011;417:179–187. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2011.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Colpitts TM, Barthel S, Wang P, Fikrig E. Dengue virus capsid protein binds core histones and inhibits nucleosome formation in human liver cells. PLoS One. 2011;6:e24365. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0024365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lanciotti RS, Kosoy OL, Laven JJ, Velez JO, Lambert AJ, et al. Genetic and serologic properties of Zika virus associated with an epidemic, Yap State, Micronesia, 2007. Emerg Infect Dis. 2008;14:1232–1239. doi: 10.3201/eid1408.080287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary File 1