Abstract

Introduction

The lack of effective, consistent, reproducible and efficient asthma ascertainment methods results in inconsistent asthma cohorts and study results for clinical trials or other studies. We aimed to assess whether application of expert artificial intelligence (AI)-based natural language processing (NLP) algorithms for two existing asthma criteria to electronic health records of a paediatric population systematically identifies childhood asthma and its subgroups with distinctive characteristics.

Methods

Using the 1997–2007 Olmsted County Birth Cohort, we applied validated NLP algorithms for Predetermined Asthma Criteria (NLP-PAC) as well as Asthma Predictive Index (NLP-API). We categorised subjects into four groups (both criteria positive (NLP-PAC+/NLP-API+); PAC positive only (NLP-PAC+ only); API positive only (NLP-API+ only); and both criteria negative (NLP-PAC−/NLP-API−)) and characterised them. Results were replicated in unsupervised cluster analysis for asthmatics and a random sample of 300 children using laboratory and pulmonary function tests (PFTs).

Results

Of the 8196 subjects (51% male, 80% white), we identified 1614 (20%), NLP-PAC+/NLP-API+; 954 (12%), NLP-PAC+ only; 105 (1%), NLP-API+ only; and 5523 (67%), NLP-PAC−/NLP-API−. Asthmatic children classified as NLP-PAC+/NLP-API+ showed earlier onset asthma, more Th2-high profile, poorer lung function, higher asthma exacerbation and higher risk of asthma-associated comorbidities compared with other groups. These results were consistent with those based on unsupervised cluster analysis and lab and PFT data of a random sample of study subjects.

Conclusion

Expert AI-based NLP algorithms for two asthma criteria systematically identify childhood asthma with distinctive characteristics. This approach may improve precision, reproducibility, consistency and efficiency of large-scale clinical studies for asthma and enable population management.

Keywords: asthma, asthma epidemiology, paediatric asthma

Key messages.

Can expert artificial intelligence (AI)-based natural language processing (NLP) systematically identify childhood asthma and a subgroup of asthmatic children with distinctive clinical characteristics by leveraging electronic health records (EHRs)?

Expert-AI-based NLP algorithms unlocks the vast yet valuable information in free text embedded in EHRs in a way systematically identifying childhood asthma and reducing methodological heterogeneity of identifying asthma in capturing its true biological heterogeneity.

Expert AI-based NLP algorithms helps clinicians and researchers systematically identify childhood asthma and its subgroups with distinctive characteristics from EHRs with precision, reproducibility and affordability.

Introduction

Important concerns in the current asthma care and research are the use of inconsistent asthma criteria, asthma ascertainment processes and sampling frame.1 The resultant variability in identification of asthma across the practice and research settings may cause inconsistent results of studies including genome-wide association studies, clinical trials and biomarker studies and delayed translation of important study findings into clinical practice eventually deterring translation of study results into clinical practice.2–10 For example, one previous study reported that 60 different definitions of childhood asthma have been used among 122 published studies.1 This is in part due to: (1) the lack of consensus for asthma ascertainment, (2) inherent limitations of structured data to ascertain asthma (eg, poor sensitivity of International Classification of Diseases (ICD) codes, 31%11), (3) expensive and difficult to use suggested biomarkers for ascertaining asthma for large-scale studies and (4) labour-intensive, expensive and inconsistent manual chart review of great volumes of records to apply asthma criteria despite their availability.

Given the growing deployment of electronic health records (EHRs) systems enabling large practice-based longitudinal data mining, advancement in artificial intelligence (AI) approaches such as natural language processing (NLP; expert AI) may potentially enable us to address these challenges as it can extract, process and classify free-text data from EHRs.12–15 For example, we recently developed and validated NLP algorithms for two existing retrospective criteria for childhood asthma (NLP algorithms for Predetermined Asthma Criteria (NLP-PAC) and NLP algorithms for Asthma Predictive Index (NLP-API)).14 15 The performance of individual NLP algorithm determining asthma status based on comprehensive EHRs including free text was almost close to that by humans (eg, 97% sensitivity and 95% specificity for NLP-PAC).14 We also demonstrated external validation of our NLP algorithms for these asthma criteria across different study settings despite different population, practice and EHRs systems.16 17 Thus, such capabilities of NLP using EHRs are poised to potentially address the current challenges in asthma research and care described above by applying the existing asthma criteria to cohorts of children in a consistent manner on a large scale.

While the two asthma criteria are complementary, it is unknown whether NLP algorithms for the two asthma criteria systematically identify childhood asthma and its subgroup with distinctive clinical characteristics. We applied the NLP algorithms to a large birth cohort in a real-word setting and systematically characterised subgroups of asthmatic children.

Methods

Study design

This is a cross-sectional analysis nested in the retrospective birth cohort study using the 1997–2007 Olmsted County Birth Cohort. We applied NLP algorithms for the two asthma criteria to the EHRs of the birth cohort to identify children with asthma and characterise subgroups of these children by using supervised cross-sectional analysis for the whole birth cohort. Then, we replicated the original results by performing unsupervised cluster analysis for asthmatic subgroups and a cross-sectional analysis for laboratory and pulmonary function test (PFT) data of a random stratified sample of 300 children.

Patient and public involvement

This research was done without patient involvement. Patients were not invited to comment on the study design and were not consulted to develop patient relevant outcomes or interpret the results. Patients were not invited to contribute to the writing or editing of this document for readability or accuracy.

Study setting

Olmsted County, Minnesota, is a virtually self-contained healthcare environment (only two healthcare providers provide clinical care to Olmsted County, Minnesota residents), and 98% of residents authorise their medical records to be used for research.18 Under the auspices of the Rochester Epidemiology Project (REP), all clinical diagnoses and procedures are linked between healthcare providers and individual patients and retrievable from medical records.18

Study subjects

We enrolled all eligible children who were born at Mayo Clinic Rochester and received their primary care there throughout the study period (1997–2015). We excluded: (1) children who did not have research authorisation, (2) those who visited a non-Mayo Clinic healthcare provider in the community with a diagnostic code related to asthma (eg, asthma, bronchiolitis, pneumonia and wheezing), which was captured in the REP database and (3) those who did not have any visits at Mayo Clinic within the last 3 years.

Asthma defined by NLP-PAC and NLP-API as predictor variables

The renowned asthma researchers, Drs Yunginger and Reed developed and validated PAC for retrospective studies among children and adults based on comprehensive medical record review (table 1-1),19 which has been extensively used for asthma research over time. PAC is conceptually similar to the 2015 Canadian Thoracic and Canadian Pediatric Society asthma criteria consisting of: (1) recurrent wheezing episodes or airflow obstruction, (2) reversibility to bronchodilator and (3) exclusion of alternative diagnoses.20 Since most cases of probable asthma became definite asthma over time, both definite and probable asthma were considered as PAC positive.19 Although the API was originally developed to predict asthma among preschoolers, the National Asthma Education and Prevention Program recommended it for identification of asthmatic children for timely asthma treatment (table 1-2).14 15 We previously reported the details for the development and validation of both NLP algorithms14 15 with a great performance (sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value and negative predictive value: 97%, 95%, 90% and 98% for NLP-PAC, and 86%, 98%, 88% and 98% for NLP-API). Briefly, both NLP algorithms had the sequential process to determine positivity for asthma criteria: (1) the text extraction that searches evidence concepts for asthma in EHRs, (2) processing the extracted concepts based on rules for asthma criteria and (3) categorising asthma status accordingly. The algorithm was implemented using the open-source NLP pipeline MedTagger (http://ohnlp.org/index.php/MedTagger) developed by Mayo Clinic.21 NLP-PAC has been externally validated at both Mayo Clinic and another study setting with a different practice, population and EHRs (Epic Systems) (Sioux Falls, South Dakota).16 17 We applied these two NLP algorithms, NLP-PAC and NLP-API, to the entire EHRs of the eligible subjects of the 1997–2007 Olmsted County Birth Cohort up to 31 August 2015, or the last follow-up date, and categorised them into four groups: both criteria positive (NLP-PAC+/NLP-API+), PAC only positive (NLP-PAC+ only), API only positive (NLP-API+ only), and both criteria negative, non-asthmatic (NLP-PAC−/NLP-API−). An asthma index date was defined as when PAC or API was met, whichever came first.

Table 1.

Asthma criteria

| 1–1. Predetermined Asthma Criteria (PAC) | |

| |

| 1–2. Asthma Predictive Index (API) | |

| Major criteria | Minor criteria |

|

|

*Asthma is determined by frequent wheezing episodes (two or more) plus at least one of two major criteria or two of three minor criteria.

FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 s; FVC, forced vital capacity.

Clinical variables for characterising subgroups of asthmatic children:

To characterise subgroups of the birth cohort, we collected pertinent variables from EHRs listed in tables 2 and 3. Socioeconomic status (SES) at birth defined by the validated HOUsing-based Index of SocioEconomic Status (HOUSES).22 We also identified asthma-associated infectious and inflammatory multimorbidities (AIMs) based on the previously reported conditions associated with asthma.23

Table 2.

Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics for subgroups of asthma by NLP-PAC and NLP-API.

| NLP-PAC+/ NLP-API+ (n=1614) |

NLP-PAC+ only (n=954) |

NLP-API+ only (n=105) | NLP-PAC−/ NLP-API− (n=5523) |

Total (n=8196) |

P value | |

| Age at the last follow-up date, years, mean (SD) | 12.2 (3.1) | 12.2 (3.1) | 11.8 (3.2) | 11.6 (3.2) | 11.8 (3.2) | <0.001 |

| Male, n (%) | 959 (59) | 521 (55) | 58 (55) | 2664 (48) | 4202 (51) | <0.001 |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | 0.007 | |||||

| White | 1289 (80) | 779 (82) | 77 (73) | 4414 (80) | 6559 (80) | |

| Black | 93 (6) | 53 (6) | 8 (8) | 244 (4) | 398 (5) | |

| Hispanic | 50 (3) | 27 (3) | 7 (7) | 233 (4) | 317 (4) | |

| Asian | 69 (4) | 26 (3) | 5 (5) | 270 (5) | 370 (5) | |

| Others | 101 (6) | 60 (6) | 7 (7) | 314 (6) | 482 (6) | |

| HOUSES* at birth in the lowest quartile, n (%) | 343 (21) | 191 (20) | 23 (22) | 971 (18) | 1528 (19) | 0.004 |

| Overweight†, n (%) | 281 (17) | 179 (19) | 20 (19) | N/A | 480 f (18) | 0.62‡ |

| Maternal smoking history during pregnancy, n (%) | 131 (8) | 88 (9) | 12 (11) | 105 (2) | 336 (4) | 0.52 |

| Family history of asthma, n (%) | 586 (36) | 135 (14) | 36 (34) | 826 (15) | 1583 (19) | <0.001 |

| Well-child visit per year, mean (SD) | 0.95 (0.31) | 0.90 (0.29) | 0.96 (0.36) | 0.93 (0.36) | 0.93 (0.34) | <0.001 |

The percentage of each variable was calculated with the number of each group (column %).

*HOUSES: individual-level housing-based socioeconomic status measure in quartile.

†Overweight at asthma index date (for children age 2 years or more, body mass index-for-age at or above 85% used (https://www.cdc.gov/obesity/childhood/defining.html)); for those age less than 2 years, weight-for-lengths at or above 95%; (https://www.cdc.gov/nccdphp/dnpao/growthcharts/who/using/).

‡Overweight for NLP-PAC−/NLP-API− group is not available; p values were calculated among asthmatic group, n=2673 (NLP-PAC+/NLP-API+, NLP-PAC+ only and NLP-API+ only).

NLP, natural language processing; NLP-API, NLP algorithms for Asthma Predictive Index; NLP-PAC, NLP algorithms for Predetermined Asthma Criteria.

Table 3.

Asthma-specific clinical and laboratory characteristics for the study subjects by subgroup

| NLP-PAC+/ NLP-API+ (n=1614) |

NLP-PAC+ only (n=954) | NLP-API+ only (n=105) | NLP-PAC−/ NLP-API− (n=5523) |

Total (n=8196) |

P value | |

| Asthma diagnosis | ||||||

| Physician diagnosed asthma, n (%) | 1123 (70) | 554 (58) | 2 (2) | N/A | 1679j (21) | <0.001 |

| Age at first physician diagnosis of asthma, years, mean (SD) | 4.3 (3.4) | 6.1 (4.3) | 8.8 (0.5) | N/A | 4.9j (3.8) | <0.001 |

| Age at asthma onset by PAC or API, years, mean (SD) | 3.3 3.2) |

4.6 (4.2) | 6.4 (4.8) | N/A | 3.9j (3.8) | <0.001 |

| Atopic status | ||||||

| Eczema, n (%) | 794 (49) | 127 (13) | 62 (59) | 1403 (25) | 2386 (29) | <0.001 |

| Allergic rhinitis, n (%) | 646 (40) | 150 (16) | 30 (29) | 660 (12) | 1486 (18) | <0.001 |

| Eosinophilia*, n (%) | 565 (35) | 120 (13) | 33 (31) | 905 (16) | 1623 (20) | <0.001 |

| Unavailable, n (%) | 527 (33) | 443 (46) | 30 (29) | 2740 (50) | 3740 (46) | |

| Total IgE (kU/L)>300, n (%) | 50 (3) | 8 (1) | 1 (1) | 19 (0) | 78 (1) | 0.02 |

| Unavailable, n (%) | 1438 (89) | 918 (96) | 97 (92) | 5387 (98) | 7840 (96) | |

| Elevated IgE to any aeroallergen†, n (%) | 59 (4) | 13 (1) | 1 (1) | 38 (1) | 111 (1) | 0.55 |

| Unavailable, n (%) | 1459 (90) | 922 (97) | 99 (94) | 5405 (98) | 7885 (96) | |

| Asthma outcomes | ||||||

| FEV1/FVC <0.85, n (%) | 346 (21) | 91 (10) | 4 (4) | 37 (1) | 478 (6) | <0.001 |

| Unavailable, n (%) | 1021 (63) | 756 (79) | 100 (95) | 5424 (98) | 7301 (89) | |

| Acute exacerbation of asthma, n (%) | 359 (22.2) | 72 (8) | 4 (4) | N/A | 435j (16) | <0.001 |

| HEDIS-defined persistent asthma, n (%) | 423 (26) | 112 (12) | 1 (1) | N/A | 53§ (20) | <0.001 |

| Asthma-associated Infectious and inflammatory multimorbidities | ||||||

| Pneumonia, n (%) | 539 (33) | 245 (26) | 23 (22) | 764 (14) | 1571 (19) | <0.001 |

| Tympanostomy tube, n (%) | 192 (12) | 80 (8) | 13 (12) | 337 (6) | 622 (8) | <0.001 |

| Pertussis, n (%) | 39 (2) | 18 (2) | 5 (5) | 71 (1) | 133 (2) | <0.001 |

| Zoster, n (%) | 37 (2) | 14 (2) | 3 (3) | 77 (1) | 131 (2) | 0.05 |

| Appendicitis, n (%) | 30 (2) | 9 (1) | 8 (8) | 67 (1) | 114 (1) | <0.001 |

| Frequency of viral infection per year, mean (SD) | 0.67 (0.43) | 0.51 (0.34) | 0.50 (0.42) | 0.32 (0.28) | 0.41 (0.35) | <0.001 |

| Frequency of strep infection‡ per year, mean (SD) | 0.15 (0.18) | 0.14 (0.18) | 0.13 (0.15) | 0.12 (0.16) | 0.13 (0.17) | <0.001 |

| Coeliac disease, n (%) | 21 (1) | 5 (1) | 0 (0) | 44 (1) | 70 (1) | 0.10 |

The percentage of each variable was calculated with the number of each group (column %).

*Eosinophilia defined by >300/µL (PAC) or ≥4% (API).

†Elevated IgE defined by >0.35 kU/L to any aeroallergen among alternaria tenuis, cat epithelium, dog dander, house dust mite/D.F., house dust mite/D.P., elm, oak, short ragweed and timothy grass.

‡Strep infection, Streptococcus pyogenes upper respiratory infection.

§Physician-diagnosed asthma, age at first physician diagnosis of asthma, age at asthma onset by PAC or API, acute exacerbation of asthma and HEDIS-defined persistent asthma for NLP-PAC−/NLP-API− group are not available; p values were calculated among asthmatic group, n=2673 (NLP-PAC+/NLP-API+, NLP-PAC+ only and NLP-API+ only).

FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 s; FVC, forced vital capacity; HEDIS, Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set; NLP-API, NLP algorithms for Asthma Predictive Index; NLP-PAC, NLP algorithms for Predetermined Asthma Criteria.

Replication of the initial results by analysing lab and PFT data of a random sample and performing unsupervised cluster analysis

We performed an unsupervised cluster analysis to replicate the initial results based on a supervised cross-sectional analysis as described in the Statistical Analysis section. In addition, as not all subjects had laboratory and PFT data available in EHRs of the birth cohort, to replicate the initial supervised cross-sectional analysis results based on the whole birth cohort, we performed a stratified random sampling of a total of 300 subjects from four subgroups of the whole cohort described above and prospectively enrolled them to obtain laboratory and PFT data. We included total and specific IgE, serum eosinophil count, exhaled nitric oxide (eNO), serum periostin and forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1)/forced vital capacity (FVC). Serum periostin was measured by Periostin ELISA kit (Shino-Test Corporation).

Statistical analysis

Baseline characteristics for the four groups described above were summarised using frequencies for categorical variables and means (±SD) for continuous variables in both the whole cohort and the random sample. Statistical significance for the associations of individual clinical and laboratory variables of the four groups was tested using Pearson’s χ2 or Fisher’s exact test and Kruskal-Wallis rank-sum test. For an unsupervised cluster analysis, we performed a non-negative matrix factorisation approach24 to identify clusters of variables and subgroups of subjects with asthma (excluding non-asthmatics) described above. The variables for cluster analysis comprised the same variables included in the initial analysis for the whole cohort (see tables 2 and 3). The optimal number of clusters were determined by finding the first value for which the cophenetic coefficient, which measures the stability of the clusters, starts decreasing drastically.25 Once the optimal number of clusters was determined, clusters were created by following standard approaches for non-negative matrix factorisation.24 All analyses were performed using R statistical software.

Results

Sociodemographic characteristics

Characteristics of study subjects are summarised in table 2. Of the total number of 22 011 Olmsted County Birth Cohort, we excluded 13 815 subjects (n=1528 for no research authorisation, n=4412 for asthma-related diagnosis outside Mayo Clinic EMRs and n=7875 for no visit within 3 years) resulting in 8196 children. Of the eligible 8196 subjects, 51% were male, 80% were white and mean age (±SD) at the last follow-up date was 11.8 (±3.2) years. Asthmatic children (those who met either or both asthma criteria) were more likely to be male (p<0.001) and had lower SES at birth as measured by HOUSES compared with those without asthma (p=0.004). The frequency of well-child visits in the NLP-PAC+/NLP-API+ group was clinically similar to that of non-asthmatics (about one visit per year), while children in NLP-PAC+ only group seem to have slightly lower frequency of well-child visit (p<0.001). There was no difference between asthmatics and non-asthmatics with regard to birth season or maternal smoking rate during pregnancy. The maternal smoking rate during pregnancy in this birth cohort was only 4%.

Prevalence of asthma

During the study period, 1679 (21%) children had a physician diagnosis of asthma in EHRs, and the mean age at the first physician diagnosis was 4.9 (±3.8) years, whereas 2568 (31%) and 1719 (21%) children met PAC and API, respectively. With inclusion of all three asthmatic groups (NLP-PAC+/NLP-API+, NLP-PAC+ only and NLP-API+ only), the mean age at asthma index date by both algorithms was 3.9 (±3.8) years. The resulting breakdown asthma prevalence of all four groups is as follows: 1614 (20%, NLP-PAC+/NLP-API+), 954 (12%, NLP-PAC+ only), 105 (1%, NLP-API+ only) and 5523 (67%, NLP-PAC−/NLP-API−; no asthma). Ninety-one per cent of PAC positive children were definite asthma by PAC. The highest proportion of those with a physician diagnosis of asthma (70%) and the earliest onset of asthma (4.3 years) were observed among children who met both criteria (NLP-PAC+/NLP-API+ group) (table 3).

Characteristics of subgroups of asthma

As expected, the NLP-PAC+/NLP-API+ and NLP-API+ only groups were more likely to have a history of allergic rhinitis, eczema, a family history of asthma, elevated eosinophil count and total IgE level than their counterparts in the NLP-PAC−/NLP-API− and NLP-PAC+ only groups tables 2 and 3). Importantly, the NLP-PAC+/NLP-API+ group was more likely to have impaired lung function, frequent asthma exacerbations, persistent asthma and overall higher risk of AIMS, compared with other asthmatic groups (either NLP-PAC+ only or NLP-API+ only) (table 3).

Laboratory and PFT measures for a random sample of subjects from subgroups

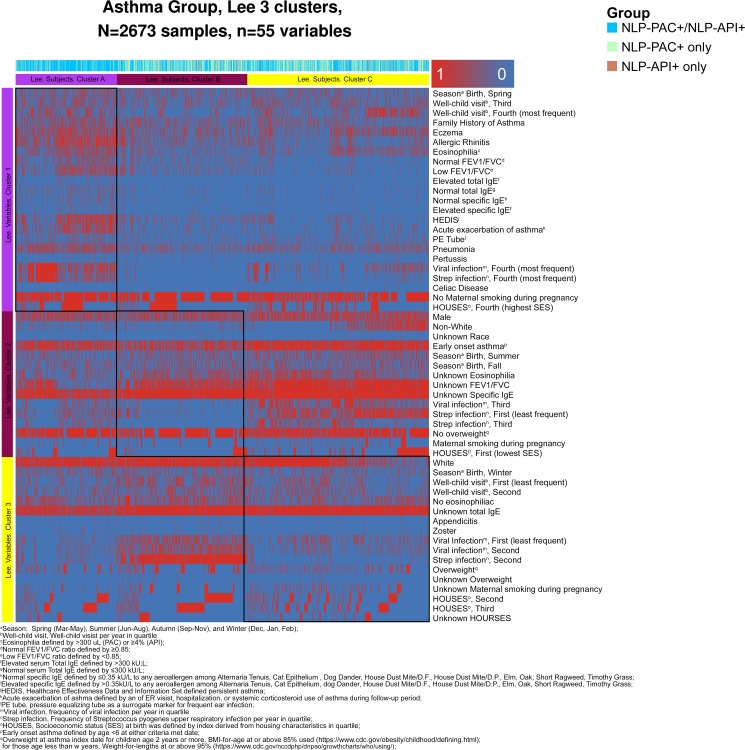

Among a random stratified sample of study subjects (n=300) for replicating the results based on the whole cohort, 53% were male, 81% were white and mean age (±SD) at the enrolment date was 13.2 (±2.5) years similar to the whole cohort. NLP-PAC+/NLP-API+ children showed the highest likelihood of atopic conditions, allergic sensitisations, Th2-high immune responses (elevated eNO and serum periostin) and impaired pulmonary function compared with other groups (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Characteristics of laboratory and pulmonary function test results among a random sample of the original study cohort (n=300). NLP, natural language processing; NLP-API, NLP algorithms for Asthma Predictive Index; NLP-PAC, NLP algorithms for Predetermined Asthma Criteria.

Unsupervised cluster analysis:

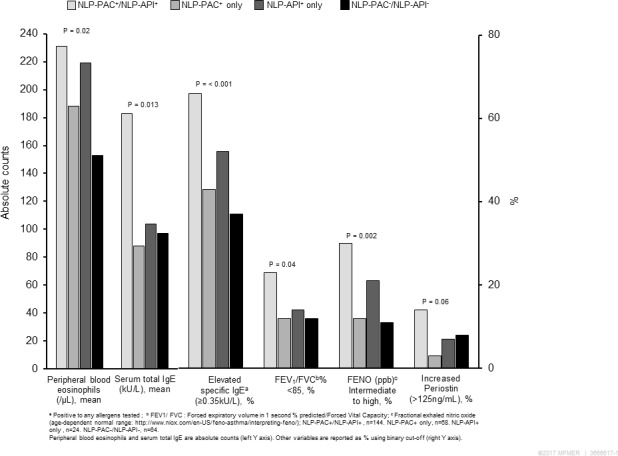

In an independent cluster analysis among asthmatics only, three clusters of subjects emerged and cluster A was most distinctive based on heatmap in figure 2 and table 4. Subjects in cluster A defined in the purple column and row (n=655) were characterised by a greater likelihood of persistent asthma, asthma exacerbation, pneumonia, pertussis, Pressure Equilizer (PE) tube, coeliac disease, viral and streptococcal infection, family history of asthma, eczema, allergic rhinitis, eosinophilia, no smoking during pregnancy, higher SES and spring birth. Importantly, cluster A had a disproportionately higher proportion of NLP-PAC+/NLP-API+ (82%) compared with cluster B (51%) or cluster C (55%). As most of cluster A represented NLP-PAC+/NLP-API+ group, these results are consistent with those by the supervised analysis of entire study subjects (table 1 and figure 1).

Figure 2.

A heatmap of variable clusters (rows) and subject clusters (columns) among asthmatics (NLP-PAC+/NLP-API+, NLP-PAC+ only and NLP-API+ only group), which was identified by non-negative matrix factorisation with three optimal clusters (see Statistical analysis section for details). This heatmap consists of two cluster axis, while the three horizontal (rows) clusters present the sociodemographic and clinical variable clusters (eg, cluster 1 includes more children with spring birth, family history of asthma and history of eczema), the three vertical (columns) clusters present patient clusters (eg, 82% of cluster A represented group of NLP-PAC+/NLP-API+ (light blue)). Each rectangular red box in the map represents presence of each variable (eg, cluster 1 includes more children with history of allergic rhinitis compared with other two clusters), while each blue box represents absence of each variable. Subject cluster A (n=655) had the following characteristics: spring birth, more frequent family history of asthma, eczema, allergic rhinitis, eosinophilia, persistent asthma, asthma exacerbation, pneumonia, pertussis, tympanostomy tube, coeliac disease, no smoking during pregnancy, high SES defined by HOUSES and viral and streptococcal infection, compared with cluster B and C (see online supplementary table 4 above). HOUSES, HOUsing-based Index of SocioEconomic Status; NLP-API, NLP algorithms for Asthma Predictive Index; NLP-PAC, NLP algorithms for Predetermined Asthma Criteria; SES, socioeconomic status.

Table 4.

Characteristics for the clusters using non-negative matrix factorisation technique among asthmatics (NLP-PAC+/NLP-API+, NLP-PAC+ only and NLP-API+ only group) (the three clusters were depicted in the heatmap analysis in figure 2)

| Cluster A (n=655) | Cluster B (n=843) | Cluster C (n=1175) | Total (n=2673) | P value | |

| Group defined by NLP, n (%) | <0.001* | ||||

| Group 1 (NLP-PAC+/NLP-API+) | 536 (82) | 430 (51) | 648 (55) | 1614 (60) | |

| Group 2 (NLP-PAC+ only) | 110(17) | 369 (44) | 475 (40) | 954 (36) | |

| Group 3 (NLP-API+ only) | 9 (1) | 44 (5) | 52 (4) | 105 (4) | |

| Male, n (%) | 369 (56) | 442 (52) | 727 (62) | 1538 (58) | <0.001* |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | <0.001* | ||||

| White | 575 (88) | 765 (91) | 805 (69) | 2145 (80) | |

| HOUSES at birth in lowest quartile, n (%) | 114 (17) | 112 (13) | 331 (28) | 557 (21) | <0.001* |

| Overweight†, n (%) | 108 (17) | 176 (21) | 196 (17) | 480 (18) | 0.021* |

| Unknown, n (%) | 2 (0) | 13(2) | 9 (1) | 24 (1) | |

| Maternal smoking history during pregnancy, n (%) | 42 (6) | 63 (8) | 126 (11) | 231 (9) | <0.001* |

| Unknown, n (%) | 44 (7) | 104 (12) | 162 (14) | 310 (12) | |

| Infrequent well-child visit per year in quartile in the lowest quartile, n (%) | 101 (15) | 332 (39) | 235 (20) | 668 (25.0) | <0.001* |

| Family history of asthma, n (%) | 242 (37) | 244 (29) | 271 (23) | 757 (28) | <0.001* |

| Early onset asthma‡, n (%) | 475 (73) | 532 (63) | 1031 (88) | 2038 (76) | <0.001* |

| Eczema, n (%) | 329 (50) | 254 (30) | 400 (34) | 983 (37) | <0.001* |

| Allergic rhinitis, n (%) | 389 (59) | 22 7(27) | 210 (18) | 826 (31) | <0.001* |

| Eosinophilia, n (%)§ | 271 (41) | 147 (17) | 300 (26) | 718 (27) | <0.001* |

| Unknown, n (%) | 153 (23) | 329 (39) | 518 (44) | 1000 (37) | |

| Total IgE (kU/L)>300, n (%) | 41 (6) | 7 (1) | 11 (1) | 59 (2) | 0.32* |

| Unknown, n (%) | 520 (79) | 809 (96) | 1124 (96) | 2453 (92) | |

| Elevated IgE to any aeroallergen, n (%)¶ | 48 (7) | 11 (1) | 14 (1) | 73 (3) | 0.68* |

| Unknown, n (%) | 535 (82) | 813 (96) | 1132 (96) | 2480 (93) | |

| FEV1/FVC<0.85, n (%) | 238 (36) | 136 (16) | 67 (6) | 441 (17) | 0.65* |

| Unknown, n (%) | 237 (36) | 590 (70) | 1050 (89) | 1877 (70) | |

| Acute exacerbation of asthma, n (%)** | 262 (40) | 77 (9) | 96 (8) | 435 (16) | <0.001* |

| HEDIS††-defined persistent asthma, n (%) | 306 (47) | 123 (15) | 107 (9) | 536 (20) | <0.001* |

| Pneumonia, n (%) | 301 (46) | 179 (21) | 327 (28) | 807 (30) | <0.001* |

| PE tube, n (%) | 106 (16) | 57 (7) | 122 (10) | 285 (11) | <0.001* |

| Pertussis, n (%) | 23 (4) | 19 (2) | 20 (2) | 62 (2) | 0.047* |

| Zoster, n (%) | 17 (3) | 23 (3) | 14 (1) | 54 (2) | 0.026* |

| Appendicitis, n (%) | 11 (2) | 23 (3) | 13 (1) | 47 (2) | 0.023* |

| Coeliac disease, n (%) | 9 (1) | 6 (1) | 11 (1) | 26 (1) | 0.42* |

| Frequent viral infection per year in group in the highest quartile, n (%) | 403 (62) | 13 (2) | 253 (22) | 669 (25) | <0.001* |

| Frequent strep infection per year in the highest quartile, n (%) | 323 (49) | 9 (1) | 102 (9) | 434 (16) | <0.001* |

*Pearson’s χ2 test.

†Overweight at asthma index date (for children age 2 years or more, BMI for age at or above 85% used (https://www.cdc.gov/obesity/childhood/defining.html)).

‡Early onset asthma defined by age at either criteria met date <6 years old.

§Eosinophilia defined by >300/µL (PAC) or ≥4% (API).

¶Elevated IgE defined by >0.35 kU/L to any aeroallergen among alternaria tenuis, cat epithelium, dog dander, house dust mite/D.F., house dust mite/D.P., elm, oak, short ragweed, timothy grass.

**Acute exacerbation of asthma defined by any of ER visit, hospitalisation or systemic corticosteroid use for asthma during follow-up period.

††Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set.

‡‡PE tube, pressure equalising tube as a surrogate marker for frequent ear infection.

§§Strep infection, Streptococcus pyogenes upper respiratory infection.

¶¶Season: spring (March–May), summer (June–August), autumn (September–November) and winter (December, January and February).

BMI, body mass index; HOUSES, HOUsing-based Index of SocioEconomic Status; NLP, natural language processing; NLP-API, NLP algorithms for Asthma Predictive Index; NLP-CAP, NLP algorithms for Predetermined Asthma Criteria.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study demonstrating that the AI using NLP algorithms for two asthma criteria systematically identified childhood asthma and its subgroup with distinctive clinical characteristics on a large scale.

Clinical characteristics of NLP-PAC+/NLP-API+ subjects observed in our study are consistent with those of children who had poor asthma outcomes in the literature as male, early onset, a family history of asthma and atopic tendency, which have been reported to be predictors for poor asthma outcomes.7 26 They had a greater likelihood of Th2-high, persistent asthma, frequent asthma exacerbation, impaired lung function and high risk of AIMs compared with non-asthmatics and those who met only NLP-PAC or NLP-API. Importantly, the findings based on a supervised cross-sectional analysis (tables 2 and 3) were replicated by a stratified random sample of 300 children selected from the four subgroups as shown in figure 1, which showed NLP-PAC+/NLP-API+ had a high likelihood of atopy (high eosinophil count, total IgE and allergen-specific IgE), Th2-high profile (FeNO and serum periostin) and impaired lung function (FEV1/FVC <85%), suggesting application of NLP-based phenotyping to a large sample-sized population is reasonable when lab test is not feasible. Also, an independent unsupervised cluster analysis for asthmatic subgroups corroborated the findings as it identified cluster A (defined in the purple column and row in figure 2) characterised by atopy, persistent asthma, frequent asthma exacerbation, impaired lung function and high risk of AIMs as shown in table 5. Importantly, cluster A had a disproportionately higher proportion of NLP-PAC+/NLP-API+ (82%) compared with cluster B (51%) or cluster C (55%).

Table 5.

List of ICD-9 and Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes used for identifying asthma-associated infectious and inflammatory diseases comorbidities

| Asthma-associated comorbidities | ICD-9 codes | CPT codes | Lab result |

| Pneumonia | 486 | N/A | N/A |

| Pertussis | 033, V01.89 (pertussis only) | N/A |

Bordetella pertussis PCR (+), B.pertussis Ab, IgM, S (+) |

| Zoster | 53 | N/A | N/A |

| Appendicitis | 540–541 | N/A | N/A |

| PE tube placement | 20.01–20.1 | 126, 69421, 69433, 69436, 69620, 69631–69 633, 69641, 69643 and 69644 |

|

| Coeliac disease | 579 | N/A | N/A |

In our study, 30% of children with NLP-PAC+/NLP-API+ did not have a physician diagnosis of asthma. In the context of ‘under-diagnosis’ of asthma,27 28 the lack of diagnosis might deter access to preventive and therapeutic interventions for asthma. As the asthma index date by the criteria was almost 1 year earlier than the first date of physician diagnosis of asthma (3.9 years vs 4.9 years), our NLP algorithms may be helpful as a population management or clinical decision support tool in the era of EHRs for early identification of asthmatic children. For example, in our recent clinical trial (Developing and Implementing Asthma-Guidance and Prediction System (a-GPS) for Better Asthma Management, Young J Juhn, MD), these two algorithms were used to inform clinicians of their patients who met two criteria without a diagnosis of asthma to help with a timely diagnosis. Nonetheless, given the wide range of different asthma ascertainment methods (eg, 60 different criteria in the literature)1 causing inconsistent results,1–10 delaying translation of scientific findings into practice and obscuring the true biological heterogeneity of asthma, our study provides an effective, consistent, reproducible and cost-efficient method of asthma ascertainment on a large scale, while not relying on self-report or ICD codes. At present, the literature on application of NLP to asthma is severely limited. One study applied a machine learning technique on EHR data (ie, codes, drugs and clinical text) in order to identify children with asthma.29 Their approach relied on a physician diagnosis of asthma (instead of asthma criteria) and did not take into account the patient’s asthma symptoms that could precede the physician’s asthma diagnosis. Thus, timely identification of asthma might not be feasible, and this approach is not able to provide physicians with evidence of the likelihood of asthma that would assist in their clinical decision making. A few studies demonstrated feasibility of extracting PFT information and smoking status from structured and semistructured data by applying NLP,13 30 while other studies attempted to predict asthma outcomes by applying machine learning or artificial neural network approaches.31 32 Nonetheless, as rich clinical information for asthma exists in free text embedded in EHRs, it is crucially important to develop an emerging and innovative AI approach enabling automated chart review and extraction or retrieval of relevant data for asthma from EHRs to make precision medicine in asthma care scalable in the future. In this respect, our study results demonstrate feasibility of such approach in a real-world setting, and this is a significantly understudied area.

The main strength of our study is the design that uses a large population-based birth cohort with longitudinal follow-up. Our study setting also has the epidemiological advantages of being a self-contained healthcare environment with a medical record linkage system through the REP enabling comprehensive medical record review for all eligible children. Our study results are based on two asthma criteria,19 33 which have been extensively used for epidemiological investigations for asthma studies. NLP-PAC was validated at both our study setting and another study setting (Sioux Falls, South Dakota) (external validity).14 17 This suggests that the NLP algorithm can be adapted in a different care setting with comparable performance, which may enable us to define and identify childhood asthma in a timely manner. This supports feasibility of application of our NLP algorithms to other study settings while recognising further multisite studies in the future. Along these lines, we discussed the results of our study with the Research Advisory Board for Community Engagement consisting of parents, community members and representatives of community agencies to seek their inputs. The advisory board provided valuable feedback for implementation of NLP algorithms in clinical care (eg, timely identification of children with asthma). This study has the inherent limitation of retrospective studies in that laboratory, and lung function data are not available for all study subjects. However, we included prospectively obtained laboratory and PFT measures for a random sample of the whole cohort that replicated the findings observed in the whole cohort. The two asthma criteria used in this study are not intended to replace a physician diagnosis of asthma. However, it is challenging to determine asthma in young children retrospectively as tests for the diagnosis of asthma are frequently not feasible, and to our knowledge, these two criteria are the only validated criteria that have been retrospectively applied to EHRs. In our study, children who met NLP-PAC during the first 4 years of life, compared with those who did not, were more likely, at a later date, to have a timely physician diagnosis of asthma (62% vs 10%, p<0.001) and reduction in FEV1/FVC (<0.85) (p<0.001). These data suggest that for research purposes, the PAC is a reasonable asthma ascertainment criteria for younger children largely overlapping with the Canadian Thoracic Society guidelines for asthma diagnosis for preschoolers.20 Even though asthma is a dynamic condition that changes over time, we had not addressed this issue in this study as it goes beyond the scope of this study. However, recently, we developed and validated an NLP algorithm for asthma prognosis after asthma onset.34 We should be able to extend NLP algorithms for asthma prognosis to the same birth cohort and report the results in near future.

In conclusion, an expert AI-based NLP algorithms for two existing asthma criteria systematically identified childhood asthma on a large scale and its subgroup with distinctive characteristics minimising methodological heterogeneity in defining asthma and maximising our abilities to detect true biological heterogeneity among asthmatic patients. In the era of EHRs, it enables precision population management strategies for asthma care and the execution of large-scale clinical studies with improved precision, reproducibility and affordability.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Mrs Kelly Okeson for her administrative assistance. We would also like to thank Drs Rohit D Divekar, Thanai Pongdee, Bong Seok Choi and Mrs Julie C Porcher for their review and helpful comments. Funding information: National Institute of Health (NIH)-funded R01 grant (R01 HL126667), R21 grants (R21AI116839-01 and R21AI142702) and T. Denny Sanford Paediatric Collaborative Research Fund. The resources of the Rochester Epidemiology Project (R01-AG34676) from the National Institute on Ageing and CTSA Grant Number UL1 TR000135 from the National Centre for Advancing Translational Sciences.

Footnotes

Contributors: Study concept and design: HL, WC, SS, ER, MAP, HK, IC and YJ; acquisition, analysis or interpretation of data: HYS, MCR, HL, WC, SS, ER, JO, SMA, JDW and YJ; drafting of the manuscript: HYS, MCR, WC, HL and YJ; critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: HYS, MCR, HL, WC, SS, ER, MAP, HK, JO, IC, SMA, JAC-R, JDW and YJ; statistical analysis: WC, ER and SMA; study supervision: HL, WC, SS, ER, MAP, HK and YJ.

Funding: National Institute of Health (NIH)-funded R01 grant (R01 HL126667) and R21 grant (R21AI116839-01 and R21AI142702), and T. Denny Sanford Pediatric Collaborative Research Fund. The resources of the Rochester Epidemiology Project (R01-AG34676) from the National Institute on Aging and CTSA Grant Number UL1 TR000135 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at Mayo Clinic (14-009934).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: No data are available. The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available as they include protected health information. Access to data could be discussed per the institutional policy after the IRB at Mayo Clinic approves it.

References

- 1. Van Wonderen KE, Van Der Mark LB, Mohrs J, et al. . Different definitions in childhood asthma: how dependable is the dependent variable? Eur Respir J 2010;36:48–56. 10.1183/09031936.00154409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Li X, Howard TD, Zheng SL, et al. . Genome-Wide association study of asthma identifies RAD50-IL13 and HLA-DR/DQ regions. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2010;125:328–35. 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.11.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ferreira MAR, Matheson MC, Duffy DL, et al. . Identification of IL6R and chromosome 11q13.5 as risk loci for asthma. Lancet 2011;378:1006–14. 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60874-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Meyers DA, Deborah AM. Genetics of asthma and allergy: what have we learned? J Allergy Clin Immunol 2010;126:439–46. 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.07.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ducharme FM, Lemire C, Noya FJD, et al. . Preemptive use of high-dose fluticasone for virus-induced wheezing in young children. N Engl J Med 2009;360:339–53. 10.1056/NEJMoa0808907 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Panickar J, Lakhanpaul M, Lambert PC, et al. . Oral prednisolone for preschool children with acute virus-induced wheezing. N Engl J Med 2009;360:329–38. 10.1056/NEJMoa0804897 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Haldar P, Pavord ID, Shaw DE, et al. . Cluster analysis and clinical asthma phenotypes. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2008;178:218–24. 10.1164/rccm.200711-1754OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Moore WC, Meyers DA, Wenzel SE, et al. . Identification of asthma phenotypes using cluster analysis in the severe asthma research program. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2010;181:315–23. 10.1164/rccm.200906-0896OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Fitzpatrick AM, Teague WG, Meyers DA, et al. . Heterogeneity of severe asthma in childhood: confirmation by cluster analysis of children in the National Institutes of Health/National heart, lung, and blood Institute severe asthma research program. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2011;127:382–9. 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.11.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lazic N, Roberts G, Custovic A, et al. . Multiple atopy phenotypes and their associations with asthma: similar findings from two birth cohorts. Allergy 2013;68:764–70. 10.1111/all.12134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Wu ST, Sohn S, Ravikumar KE, et al. . Automated chart review for asthma cohort identification using natural language processing: an exploratory study. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2013;111:364–9. 10.1016/j.anai.2013.07.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Nadkarni PM, Ohno-Machado L, Chapman WW. Natural language processing: an introduction. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2011;18:544–51. 10.1136/amiajnl-2011-000464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sauer BC, Jones BE, Globe G, et al. . Performance of a natural language processing (Nlp) tool to extract pulmonary function test (PFT) reports from structured and semistructured veteran Affairs (Va) data. EGEMS 2016;4:1217 10.13063/2327-9214.1217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wi C-I, Sohn S, Rolfes MC, et al. . Application of a natural language processing algorithm to asthma ascertainment. an automated chart review. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2017;196:430–7. 10.1164/rccm.201610-2006OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kaur H, Sohn S, Wi C-I, et al. . Automated chart review utilizing natural language processing algorithm for asthma predictive index. BMC Pulm Med 2018;18:34 10.1186/s12890-018-0593-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Sohn S, Wang Y, Wi C-I, et al. . Clinical documentation variations and Nlp system portability: a case study in asthma birth cohorts across institutions. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2017. doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocx138. [Epub ahead of print: 30 Nov 2017]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wi C-I, Sohn S, Ali M, et al. . Natural language processing for asthma ascertainment in different practice settings. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2018;6:126–31. 10.1016/j.jaip.2017.04.041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. St Sauver JL, Grossardt BR, Yawn BP, et al. . Data resource profile: the Rochester epidemiology project (Rep) medical records-linkage system. Int J Epidemiol 2012;41:1614–24. 10.1093/ije/dys195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Yunginger JW, Reed CE, O'Connell EJ, et al. . A community-based study of the epidemiology of asthma. incidence rates, 1964-1983. Am Rev Respir Dis 1992;146:888–94. 10.1164/ajrccm/146.4.888 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ducharme FM, Dell SD, Radhakrishnan D, et al. . Diagnosis and management of asthma in preschoolers: a Canadian thoracic Society and Canadian paediatric Society position paper. Can Respir J 2015;22:135–43. 10.1155/2015/101572 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Liu H, Bielinski SJ, Sohn S, et al. . An information extraction framework for cohort identification using electronic health records. AMIA Jt Summits Transl Sci Proc 2013;2013:149–53. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Juhn YJ, Beebe TJ, Finnie DM, et al. . Development and initial testing of a new socioeconomic status measure based on housing data. J Urban Health 2011;88:933–44. 10.1007/s11524-011-9572-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Juhn YJ. Risks for infection in patients with asthma (or other atopic conditions): is asthma more than a chronic airway disease? J Allergy Clin Immunol 2014;134:247–57. quiz 58-9 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.04.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lee DD, Seung HS. Algorithms for non-negative matrix factorization. Advances in neural infromation processing systems 2001:5–12.

- 25. Brunet J-P, Tamayo P, Golub TR, et al. . Metagenes and molecular pattern discovery using matrix factorization. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2004;101:4164–9. 10.1073/pnas.0308531101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Paaso EMS, Jaakkola MS, Rantala AK, et al. . Allergic diseases and asthma in the family predict the persistence and onset-age of asthma: a prospective cohort study. Respir Res 2014;15:1–9. 10.1186/s12931-014-0152-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Siersted HC, Boldsen J, Hansen HS, et al. . Population based study of risk factors for underdiagnosis of asthma in adolescence: Odense schoolchild study. BMJ 1998;316:651–5. discussion 5-6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ownby DR, Tingen MS, Havstad S, et al. . Comparison of asthma prevalence among African American teenage youth attending public high schools in rural Georgia and urban Detroit. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2015;136:595–600. 10.1016/j.jaci.2015.02.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Afzal Z, Engelkes M, Verhamme KMC, et al. . Automatic generation of case-detection algorithms to identify children with asthma from large electronic health record databases. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2013;22:826–33. 10.1002/pds.3438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Meystre SM, Deshmukh VG, Mitchell J. A clinical use case to evaluate the i2b2 hive: predicting asthma exacerbations. AMIA Annu Symp Proc 2009;2009:442–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Finkelstein J, Jeong IC. Machine learning approaches to personalize early prediction of asthma exacerbations. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2017;1387:153–65. 10.1111/nyas.13218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Khatri KL, Tamil LS. Early detection of peak demand days of chronic respiratory diseases emergency department visits using artificial neural networks. IEEE J Biomed Health Inform 2018;22:285–90. 10.1109/JBHI.2017.2698418 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Wi C-I, Park MA, Juhn YJ. Development and initial testing of asthma predictive index for a retrospective study: an exploratory study. J Asthma 2015;52:183–90. 10.3109/02770903.2014.952438 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Sohn S, Wi C-I, Wu ST, et al. . Ascertainment of asthma prognosis using natural language processing from electronic medical records. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2018;141:2292–4. 10.1016/j.jaci.2017.12.1003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]