ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND:

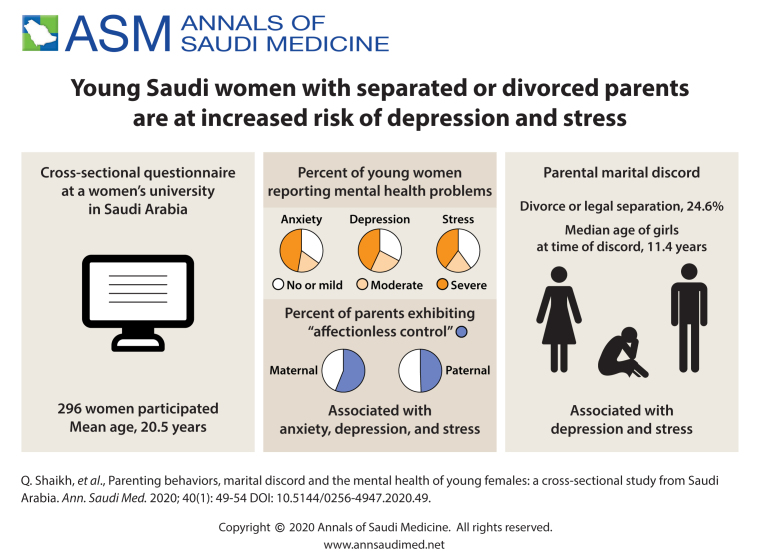

Divorce is considered a sentinel event influencing the economic, psychosocial and physical health of the family as a whole. Research shows a negative impact of parental marital discord (PMD) on the psychological health and social well-being of children. Only one study from Saudi Arabia has assessed educational and social attainment among young females, and the children were school girls aged 12-16 years.

OBJECTIVES:

Explore the relationship between parental marital discord and depression, anxiety, stress, social support and self-esteem of the female child. We also studied the parenting behaviors and their association with the psychosocial health of adolescents.

DESIGN:

Cross-sectional questionnaire.

SETTINGS:

Women's university in Saudi Arabia.

SUBJECTS AND METHODS:

REDCap was used for collecting data through email invitations sent to all students at the university. Data on family structure, parental relationship, self-esteem and psycho-social health was collected.

MAIN OUTCOME MEASURES:

Depression, anxiety, stress, self-esteem and social support of the adolescent. Parenting behaviors of both parents were also assessed.

SAMPLE SIZE:

296.

RESULTS:

The mean (SD) age of participants was 20.5 (2.4) years (median 20.0, IQR 19-22). The frequency of PMD was 24.6% (73/296). Overall, 38% of the students had extra severe anxiety, 26.5% had extra severe depression and 20.5% had extra severe stress on the Depression Anxiety and Stress Scale (DASS). The mean self-esteem score was 20.8 (5.5) and social support score was 57 (19.7). Both parents demonstrated low care and high protection trait on the Parental Bonding Instrument (PBI). Among those with PMD, mean (SD) age at discord was 11.4 (6.7) years. Mean (SD) duration of parental marriage was 20.9 (10.7) years and 35% of daughters received no financial help from the father. There was a significant association between PMD and depression, anxiety, stress and poor social support. PMD was associated with low paternal care and high protection trait.

CONCLUSIONS:

The study showed an alarming burden of mental health problems including depression, anxiety and stress among young Saudi females. Marital discord is prevalent in Saudi Arabia and is significantly related to poor psychosocial health in the child. Parents undergoing marital discord should be educated about healthy parenting styles and their children should be provided with counselling and coping strategies to maintain their emotional and psychological well-being.

LIMITATIONS:

Online survey could lead to volunteer bias. Only females are included in the study.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST:

None.

INTRODUCTION

Divorce is considered a sentinel event influencing the economic, psychosocial and physical health of the family as a whole. The Centers for Disease Control currently reports a divorce rate of 3.2/1000 population in the United States.1 Countries in Europe have divorce rates as high as 60%.2 Gulf countries including Saudi Arabia have also reported high rates of divorce in the past. Figures show a divorce prevalence of 27% in Bahrain, 26% in UAE, 37% in Kuwait and 35% in Qatar.3 Similarly, Saudis are reported to have 127 divorces/day or five divorces/hour which translates to a rate of approximately 35%.4 The highest rate of divorce, reported from the Eastern province and Tabuk, was around 36% while in Riyadh 31% marriages ended in divorce. Parental divorce is a source of lifelong distress, psychological ill-health and behavioral problems in a child.5 The literature indicates that children of divorcees receive less emotional support which can create a gap between the parent and child.6 Parental divorce leads to poor development of social skills for handling social conflicts7 and low self-esteem in dealing with peer interaction.8 The fear of peer rejection is doubled and kids demonstrate antisocial behavior, depression and anxiety9 leading to poor school achievement and performance in these children.10 Longitudinal studies in Sweden from 1968-2000, showed, that despite legal protection, rights of guardianship and sociocultural acceptability of divorce, the adverse outcomes for children including poor psychological health has not shown any significant improvement.11 A systematic review reported that these adverse outcomes manifest due to inter-parental conflict, co-parenting issues and inconsistency in parenting styles among the parents after the discord. There is negative socioeconomic impact of discord in such families and hence a pathway leading to poor psychological and physical health is triggered.12 There is a paucity of literature from the Arab world on this important health issue. A study from the UAE reported poor psychological outcomes, sleep disorders, lack of concentration in school and economic instability among children aged 1-18 years from families who go through divorce.13 We found only one study from Saudi Arabia where school girls aged 12-16 years were assessed on educational and social attainment. Saudi girls adjustment to parental divorce in that study was controlled by sociocultural factors.14 Hence, we planned to explore the burden of parental marital discord (either divorce or separation) and its relationship to psychosocial health including self-esteem, social support and mood of the female child into adulthood.

SUBJECTS AND METHODS

This cross-sectional study was conducted at Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, the largest women-only university in the world with approximately 20 different colleges and 50 000 female students situated in the capital of Saudi Arabia, Riyadh. We used Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) software, a browser-based software and workflow methodology for designing clinical and translational research databases (Vanderbilt University, United States). Students were invited to participate through an email bearing the link to the survey. Data was collected on a self-designed, pre-coded tool in Arabic language which included demographic information and details of family like siblings, step siblings, parents' education, duration of parent's marital relationship and remarriage of parents in case of marital discord. For this survey, we defined “marital discord” as either ‘legal divorce’ or ‘separation’ of parents without legal divorce’. We measured self-esteem through the Arabic version of Rosenberg's Self-esteem scale.15 The 10 item tool uses a Likert's scale with four responses option “Strongly Disagree” one point, “Disagree” two points, “Agree” three points, and “Strongly Agree” four points. The higher score indicates high self-esteem. It has been validated by Zaidi et al in Arabic language and showed a Cronbach's alpha of 0.72 in 2015.16 Mood was evaluated through the Depression anxiety and distress scale (DASS).17 The tool consists of 42 questions. The answers are based on a four point Likert's scale ranging from zero for “Did not apply to me”, one for “Applied to me to some degree” two for “Applied to me to a considerable degree” and three for “Applied to me very much”. The tool has a high reliability with a Cronbach's alpha of greater than 0.9 for each of the 3 subscales of Depression, Anxiety and Stress.18 It was validated in Arabic in 2017.19 Social support was assessed through a nine item Medical Outcomes Study (MOS) social support survey with scores ranging from 0-95.20 It includes the following subdomains: Emotional/informational support consisting of eight items (score range 0-40), tangible support consisting of four items (score range 0-20), affectionate support consisting of three items (score range 0-15), positive social interaction consisting of three items (score range 0-15) and the final score, the sum of the subdomain scores and the response to an additional item (q 19). It has been translated into Arabic and validated by Dafaalla et al in 2016 in Arabic language and showed a Cronbach's alpha of greater than 0.9 for all items.21 The relationship with parents was evaluated by the Parental Bonding Instrument (PBI).22 It comprises of two subscales consisting of 12 items on a “Care” scale and 13 items on a “Control” scale that measures the parents' fundamental style of upbringing reported by the child. The PBI has shown a Cronbach's alpha of above 0.8 for both the maternal and paternal scales.23

A sample of at least 327 girls was required to achieve a precision of 5% with a confidence level of 95% if the prevalence of divorce was estimated to be 31%.4 We chose only Saudi females for the study in order to investigate the relationship in the context of Saudi cultural and social norms. Data was analyzed using JMP Version 12 SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, 1989-2007. Descriptive statistics were reported as means (standard deviation) or median and Interquartile range (IQR) and frequency (percentage) for continuous and categorical variables respectively. Mann Whitney U or Kruskal-Wallis test was used to compare means among groups. A two tailed P value of <.05 was considered significant. The study was conducted after ethical approval from the university's ethical committee under approval number 17-0148. All data was password protected, deidentified and accessible only to the research team. The students had the right to withdraw at any point during the study. Responses with missing data were excluded from the analysis.

RESULTS

The survey was sent to all 48 481 students and the survey remained live from 7 November 2017 to 30 December 2017 when the desired sample size was reached. The number of responders was 331 but due to missing data on demographic variables the number of valid responses was eventually reduced to 296. The mean (SD) age of respondents was 20.5 (2.4) years (median 20.0, IQR 19-22). All had Saudi fathers while 290 (97.9%) had Saudi mothers. Kuwaiti and Egyptian mothers represented 1% (n=3) each. The prevalence of parental divorce in our sample was 13.3% (n=40) while that of parents living separately but not legally divorced was 10.9% (n=33). Together, the prevalence of marital discord (divorced or separated) was 24.6% (73/296). The median number of brothers and sisters was 3 each (IQR=0-10 and 0-13 respectively).

The percentage of students having any level of anxiety was 73% (n=215) (Table 1) with most participants suffering from severe anxiety (N=112; 38%). The participants suffering from any level of depression on the DASS was 75.6% (n=224) while those suffering from any stress at all were 70% (n=206). The mean (SD) score for overall social support was 57 (19.7), that for emotional support was 22.8 (9.6), tangible support was 13.4 (4.6), affectionate support was 9.1 (3.9) and positive social interaction was 9.2 (3.8). The mean score on the Rosenberg's self-esteem scale was 20.8 (5.5). The parental bonding instrument revealed low maternal care (Table 2) among 188 participants (66.4%) while maternal protection was high among 201 (70%). For the father, the score showed low paternal care among 173 (62.2%) while high paternal protection was demonstrated among 201 (75.5%). The most prominent parenting style was “affectionless control” both among mothers (n=157, 56%) and fathers (n=130, 49.6%). Among the 73 (24.6%) participants who reported parental discord, 62/73 (90%) reported it to be their parent's first marriage. The mean (SD) duration of marriage for the families suffering from discord was 20.9 years (10.7) and the mean (SD) age of the girls was 11.4 (6.7) at the time of the marital discord. Among these, 23 (31%) reported that their fathers remarried after the discord. More than half of the girls visited the other parent after the discord. Approximately 70% (n=49) had step siblings while only 8% (n=6) reported that their fathers beared all their financial expenses.

Table 1.

Psychosocial characteristics of study participants.

| Anxiety (n=293) | |

| No anxiety | 78 (26.6) |

| Mild | 25 (8.5) |

| Moderate | 53 (18.1) |

| Severe | 25 (8.5) |

| Extra severe | 112 (38.2) |

| Depression (n=294) | |

| No depression | 70 (23.8) |

| Mild | 26 (8.8) |

| Moderate | 71 (24.1) |

| Severe | 49 (16.6) |

| Extra severe | 78 (26.5) |

| Stress (n=293) | |

| No stress | 86 (29.3) |

| Mild | 32 (10.9) |

| Moderate | 57 (19.4) |

| Severe | 58 (19.8) |

| Extra severe | 60 (20.5) |

| Social support scorea | 57.2 (19.7) |

| Emotional/informational supporta | 22.8 (9.6) |

| Tangible supporta | 13.4 (4.6) |

| Affectionate supporta | 9.1 (3.9) |

| Positive social interactiona | 9.2 (3.8) |

| Self-esteem scorea | 20.8 (5.5) |

Data are n (%).

Mean (SD).

Table 2.

Parenting behaviors of the parents of the study participants.

| Parenting behaviours | Maternal | Paternal |

|---|---|---|

| PBI categories | ||

| Affectionate constraint | 41 (14.6) | 69 (26.3) |

| Optimal parenting | 53 (19.0) | 33 (12.6) |

| Affectionless control | 157 (56.3) | 130 (49.6) |

| Neglectful parenting | 28 (10.0) | 30 (11.4) |

| Attributes | ||

| Care (n=283) | ||

| Low | 188 (66.4) | 173 (62.2) |

| High | 95 (33.6) | 105 (37.7) |

| Protection (n=284) | ||

| Low | 83 (29.2) | 65 (24.4) |

| High | 201 (70) | 201 (75.5) |

Data are number (%). PBI: Parental bonding instrument

Among the psychosocial characteristics, self-esteem, depression, and stress showed significantly higher mean scores (Table 3) among daughters from families with parental marital discord (P<.05). Social support, was higher among the group from intact families but the difference was not statistically significant. Paternal care was significantly low while protection was significantly higher in the group with marital discord (P<.0001). We also explored the association of psychosocial factors with parenting behaviors of both parents (Tables 4, 5) and found that the highest levels of depression, anxiety, stress were associated with ‘affectionless control’ parenting style in both parents (P<.05) while the lowest social support (P<.05) was also exhibited with this parenting style of both mother and father (Tables 4, 5). Self-esteem was highest among daughters exposed to this parenting style (P<.05).

Table 3.

Scores for marital discord factors between girls with and without parents with marital discord.

| Parental marital status | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Discord n=73 | No discorda n=223 | ||

| Social support score | 54.0 (19.0) | 58.6 (19.8) | .09 |

| Self esteem score | 22.3 (5.7) | 20.4 (5.4) | .02 |

| Anxiety score | 17.2 (11.0) | 15.5 (11.1) | .2 |

| Depression score | 22.7 (11.4) | 18.3 (11.4) | .005 |

| Stress score | 25.1 (11.7) | 21.4 (10.6) | .009 |

| Maternal care | 22.7 (8.9) | 21.2 (9.4) | .3 |

| Maternal protection | 17.1 (7.2) | 17.9 (6.5) | .3 |

| Paternal care | 13.2 (8.9) | 20.4 (9.5) | <.0001 |

| Paternal protection | 19.6 (8.3) | 17.5 (7.0) | .04 |

Data are mean (SD).

No divorce or separation

Table 4.

Relationship of father's parenting behavior with psychosocial factors.

| Mean (SD) | PBI categories | P value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Affectionate constraint | Optimal parenting | Affectionless control | Neglectful parenting | ||

| Social Support score | 64.6 (19.4) | 73.4 (16.8) | 50.9 (18.1) | 55.6 (17.2) | <.0001 |

| Self-esteem score | 20.1 (5.1) | 17.0 (4.3) | 22.4 (5.5) | 19.4 (5.1) | .04 |

| Anxiety score | 12.8 (10.8) | 10.6 (10.9) | 19.0 (10.9) | 15.0 (10.5) | .003 |

| Depression score | 17.5 (10.7) | 12.1 (11.0) | 22.5 (11.6) | 17.6 (10.2) | .02 |

| Stress score | 18.5 (10.1) | 17.1 (11.3) | 25.0 (10.5) | 23.9 (11.2) | <.0001 |

Data are mean (SD).

Table 5.

Relationship of mother's parenting behavior with psycho-social factors.

| Mean (SD) | Parental bonding instrument categories | P value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Affectionate constraint | Optimal parenting | Affectionless control | Neglectful parenting | ||

| Social support score | 69.2 (16.7) | 69 (17.5) | 50.3 (18) | 55.5 (17.0) | <.0001 |

| Self-esteem score | 19.1 (5.6) | 18.4 (5.2) | 22.1 (5.0) | 21.1 (5.4) | <.0001 |

| Anxiety score | 11.6 (10.5) | 12.0 (10.3) | 18.6 (11.1) | 15.3 (9.4) | .0004 |

| Depression score | 16.3 (11.9) | 13.3 (10.0) | 22.3 (11.0) | 21.3 (11.3) | <.0001 |

| Stress score | 18.9 (11.7) | 17.6 (10.8) | 24.7 (10.4) | 23.9 (8.0) | <.0001 |

Data are mean (SD).

Subgroup analysis was done between divorced and separated parent families to detect any differences and it was found that the girl's mean (SD) self-esteem score was higher in the divorced group compared to the separated parents group (22.3 [3.1] vs 20.9 [2.2] respectively; P<.05). Similarly, mean (SD) duration of parents remaining together was 15.9 (8.7) vs 27.9 (9.5) in the divorced vs separation group (P<.0001). There was no significant difference between divorced and separated parent families when the girls were compared with respect to self-esteem, social support, depression, anxiety or stress scores (results not shown).

DISCUSSION

This is the first attempt to explore the psychosocial impact of parental marital discord among Saudi girls. We believe it is an important area of research and the findings are alarming. We found a high burden of anxiety, depression and stress among the girls. This is similar to previous reports showing a prevalence of 48% for mental health issues among Saudis overall and 51% among women only.24 Our results show that marital discord among parents is significantly related to depression, anxiety and stress among Saudi girls. Although most developed countries now have regulations on child custody and their subsequent financial support and even though sociocultural acceptability of divorce has improved over the last century, research shows that there has been little reduction in its psychological impact on children.25 Both Saudi parents demonstrated low care and a high protection trait of parenting, hence falling under the moiety of “affectionless control”, as per the Parental Bonding Instrument.22 This instrument classifies parenting behaviors into 4 types; ‘Affectionate constraint’ (high care and high protection), ‘Optimal parenting’ (high care and low protection), ‘Affectionless control’ (low care and high protection) and ‘Neglectful parenting’ (low care and low protection). It has been shown that children of parents exhibiting “Affectionless Control” have a high burden of mental health issues including depression, neuroticism and dysfunctionality among children. This parenting style of both parents is significantly related with depression, stress and anxiety in the girls among our study sample. Our results depict that marital discord among parents is significantly associated with low paternal care for the girls. Hence, parental divorce seems to distort the father-daughter relationship more as they tend to stay with mothers after the divorce and subsequently the fathers become overprotective and exhibit low care.26

The self-esteem scores in this study were similar to previous reports from 201 527 among Saudi women in one study and male psychology students in another study from Saudi Arabia.28 In our study the self-esteem scores were significantly higher among girls from families with marital discord compared to those where parents were still married. Subgroup analysis showed that girls from divorced families had higher self-esteem than those from separated parent families. This may be due to the fact that divorce brings an end to the straining, conflict-filled relationship and allows the child to distance themselves from parental mutual abuse and hence improves their self-esteem. Social support was significantly higher among intact family groups. It was also seen that optimal parenting from the father was associated with the highest social support score since the girls feel they have someone to depend on when fathers are supportive. These findings may be unique to the Saudi culture where girls are largely dependent on the male members of the family for social and financial support. Moreover, there is evidence to believe that girls are affected more by the long term consequences of parental divorce compared to boys who show little or no effect.29

The response rate for the survey was relatively low but as data collection was stopped upon achievement of the desired sample, it may be assumed that more responses may have been gathered if the survey continued. There is a chance of information bias in the survey because of the nature of the questions, but the proportion of missing information was very low hence minimizing any such possibility. The reason for choosing an online survey was the sensitivity of questions on the parent's marital status and conflict and we expected a lower response rate and missing information if the survey was performed by data collectors performing one to one interviews. We believe the theme of our research was a sensitive topic for the girls but still we received a good response, which helped us achieve our sample size. We chose females as the study subjects because the literature shows that the impact of parental marital discord on a female child is greater compared to a male child,29 which may hold true in the Saudi society where females are given less social and financial freedom compared to males.

We included parents who were living separately to compare the results with those who were legally divorced because divorce represents the tip of the iceberg in this culture where polygamy is legal and religiously permissible and hence many women continue to remain in a conflict-filled marriage because of social and financial gains. We found no difference in psychosocial impact among the two subsets of marital discord, although the data was underpowered for this subgroup analysis.

It may be insightful to further explore the difference between families with parental divorce and separation in the future. Longitudinal studies are needed to estimate the risk of adverse psychosocial outcomes of children among families where parents are divorced/separated. The results highlight the need for extending a similar investigation among the male children from such families. We advocate the need for family counselling centers and social support groups for the victims of parental marital discord. The society as a whole needs to develop coping strategies by creating awareness and education on the topic. Affected parents should be advised to undergo counselling for help in the upbringing of their children. We believe there is a dire need to explore the reasons for the high prevalence of mental health disorders in Saudi females and find tangible solutions to prevent further generations from suffering.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We would like to acknowledge the support provided by the bioinformatics department of the Health Sciences Research Center, PNU in developing and conducting the survey.

Funding Statement

None.

REFERENCES

- 1.CDC. Marriage and Divorce 2017. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/marriage-divorce.htm.

- 2.Insider B. MAP: Divorce Rates Around The World 2014. Available from: http://www.businessinsider.com/map-divorce-rates-around-the-world-2014-5.

- 3.News A. Divorce rates increase in GCC countries 2010. Available from: http://www.arabnews.com/node/359689.

- 4.News A. 5 divorces every hour in KSA 2016. Available from: http://www.arabnews.com/node/948551/saudi-arabia.

- 5.Cunningham M, Waldock J.. Consequences of Parental Divorce during the Transition to Adulthood: The Practical Origins of Ongoing Distress. Divorce, Separation, and Remarriage: The Transformation of Family: Emerald Group Publishing Limited; 2016. p. 199-228. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zill N, Morrison DR, Coiro MJ.. Long-term effects of parental divorce on parent-child relationships, adjustment, and achievement in young adulthood. Journal of family psychology. 1993;7(1):91. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Strohschein L. Parental divorce and child mental health trajectories. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2005;67(5):1286-300. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Verrocchio MC, Marchetti D, Fulcheri M.. Perceived Parental Functioning, Self-Esteem, and Psychological Distress in Adults Whose Parents are Separated/Divorced. Frontiers in psychology. 2015;6:1760. Epub 2015/12/05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Amato PR, Sobolewski JM.. The effects of divorce and marital discord on adult children's psychological well-being. American Sociological Review. 2001:900-21. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kinard EM, Reinherz H.. Effects of marital disruption on children's school aptitude and achievement. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1986:285-93. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gähler M, Garriga A.. Has the association between parental divorce and young adults' psychological problems changed over time? Evidence from Sweden, 1968-2000. Journal of Family Issues. 2013;34(6):784-808. [Google Scholar]

- 12.DJPVL Rui A. Nunes-Costa1, Figueiredo3 Bárbara F. C.. Psychosocial adjustment and physical health in children of divorce. Jornal de Pediatria. 2009. doi: 0021-7557/09/85-05/385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Al Gharaibeh FM. The Effects of Divorce on Children: Mothers' Perspectives in UAE. Journal of Divorce & Remarriage. 2015;56(5):347-68. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Al-Zamil AF, Hejjazi HM, AlShargawi NI, MA-A Al-Meshaal, HH. Soliman. The effects of divorce on Saudi girls' interpersonal adjustment. International Social Work. 2016;59(2):177-91. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rosenberg M. Rosenberg self-esteem scale (RSE). Acceptance and commitment therapy Measures package. 1965;61:52. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zaidi U, Awad SS, Mortada EM, Qasem HD, Kayal GF.. Psychometric evaluation of Arabic version of Self-Esteem, Psychological Well-being and Impact of weight on Quality of life questionnaire (IWQOL-Lite) in female student sample of PNU. European Medical, Health and Pharmaceutical Journal. 2015;8(2). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lovibond Lovibond P. Manual for the depression anxiety stress scales. The Psychology Foundation of Australia Inc; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brown TA, Chorpita BF, Korotitsch W, Barlow DH.. Psychometric properties of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS) in clinical samples. Behaviour research and therapy. 1997;35(1):79-89. PubMed PMID: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moussa MT, Lovibond P, Laube R, Mega-head HA.. Psychometric properties of an arabic version of the depression anxiety stress scales (DASS). Research on Social Work Practice. 2017;27(3):375-86. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sherbourne CD, Stewart AL.. The MOS social support survey. Social science & medicine. 1991;32(6):705-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dafaalla M, Farah A, Bashir S, Khalil A, Abdulhamid R, Mokhtar M, et al. . Validity and reliability of Arabic MOS social support survey. SpringerPlus. 2016;5(1):1306. doi: 10.1186/s40064-016-2960-4. PubMed PMID: . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Parker G, Tupling H, Brown L.. A parental bonding instrument. Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice. 1979;52(1):1-10. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kapci EG, Kucuker S.. [The parental bonding instrument: evaluation of psychometric properties with Turkish university students]. Turk psikiyatri dergisi = Turkish journal of psychiatry. 2006;17(4):286-95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Almutairi AF. Mental illness in Saudi Arabia: an overview. Psychology research and behavior management. 2015;8:47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gähler M, Palmtag E-L.. Parental divorce, psychological well-being and educational attainment: Changed experience, unchanged effect among Swedes born 1892–1991. Social Indicators Research. 2015;123(2):601-23. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Riggio HR. Parental marital conflict and divorce, parent?child relationships, social support, and relationship anxiety in young adulthood. Personal Relationships. 2004;11(1):99-114. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kazi ARH, Aljohara MA.. Self-esteem and its correlates in Saudi women in Riyadh, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Asian Academic Research Journal of Social Science & Humanities. 2015;2(5):213-27. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Alyami M, Ullah E, Alyami H, Hill A, Henning M.. The impact of self-esteem, academic self-efficacy and perceived stress on academic performance: A cross-sectional study of Saudi psychology students. Eur J Educ Sci. 2017;4(3):51-63. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Huurre T, Junkkari H, Aro H.. Long–term Psychosocial effects of parental divorce. European archives of psychiatry and clinical neuroscience. 2006;256(4):256-63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]