ABSTRACT

Immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICI) therapies can achieve meaningful tumor responses in a subset of patients with most types of cancer that have been investigated. However, the majority of patients treated with these drugs do not experience any clinical benefit. Because not all patients benefit from ICIs, and some may experience more meaningful tumor response if treated with chemotherapy or other treatments, there is a compelling need for predictive biomarkers to facilitate more informed selection of therapy. Tumor mutational burden (TMB) is one feature of a tumor that has predictive value for ICI therapy across multiple cancer types. In a pan-cancer analysis of over 1,600 patients, higher TMB was associated with longer survival and higher response rates with ICI therapy. While this effect was seen in the majority of cancer types, indicating that TMB underlies fundamental aspects of immune-mediated tumor rejection, the optimal predictive cut-point varied widely by histology, suggesting that there is unlikely to be one tissue-agnostic definition of high TMB that is useful for predicting ICI response. More comprehensive predictive models integrating TMB with other factors – including genetic, immunologic, and clinicopathologic markers – will be needed to potentially achieve a tissue-agnostic predictor of benefit from ICIs.

KEYWORDS: Tissue-agnostic, pan-cancer, tumor mutational burden, cutoffs

Introduction

Since it was first shown in 1996 that anti-CTLA-4 antibodies led to tumor regression in mouse models,1 and subsequently in 2010, that the agent ipilimumab improved overall survival in patients with stage IV melanoma,2 immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICI) drugs have been recognized as a therapy that has activity across many types of human cancer.3–7 In addition to demonstrating benefit in a subset of patients with nearly every cancer type tested, ICIs have also achieved long-term, sustained tumor regressions in some patients.

Despite these impressive results, only a minority of patients experience tumor response, and very few experience durable disease control. In fact, it is estimated that only 12% of all cancer patients will benefit from ICIs,8 a number that, while likely to increase further, remains modest. In addition, even though severe adverse effects occur with less frequency than with cytotoxic chemotherapies, some adverse effects can be permanent. Recently, some emerging evidence has suggested that a small percentage of patients (perhaps up to 10–20%) may experience tumor “hyperprogression” from ICIs.9 Considering the probabilities of response, immune-related adverse events, and potentially even hyperprogression, it is clear that approaches are needed to identify patients with higher or lower likelihood of benefit from ICIs.

Significant progress has been made in identifying biomarkers for ICI effectiveness in certain cancer types such as melanoma and non-small cell lung cancer. Some biomarkers with predictive value for ICIs include: tumor mutational burden (TMB), PD-L1 expression, gene expression derived measures of T-cell infiltration, and human leukocyte antigen (HLA) genotype or loss of heterozygosity.10 However, until recently, these markers have not been assessed in a pan-cancer fashion, in order to determine if they represent biology that is broadly applicable across many cancer types.

TMB as a predictive biomarker for ICIs

The hypothesis that TMB would influence tumor response to ICI therapy stems directly from the concept of mutation-derived neoantigens that can be recognized by immune cells. During cancer development, genetic mutations may, if expressed and processed, result in the formation of novel peptide sequences that can be presented via HLA class I to T-cells, which may then elicit a cytotoxic immune response. The higher the number of somatic nonsynonymous mutations, the higher the likelihood of generating neoantigens that can be recognized by the immune system, and thus the higher likelihood of tumor rejection when checkpoints on T-cells are removed by ICI therapies. The first studies that supported this hypothesis were by Snyder et al.11 and Rizvi et al.,12 which showed that higher numbers of nonsynonymous mutations were associated with higher rates of objective response and progression-free survival in patients with melanoma treated with anti-CTLA-4 therapy, and non-small cell lung cancer treated with anti-PD-1 therapy, respectively. This hypothesis has subsequently been extensively supported by others in the context of melanoma, lung, and bladder cancer.13–15

We speculated that TMB would have wide applicability for prediction of ICI response across many or most cancer histologies, but until recently, data had been limited to these specific cancer types (melanoma, non-small cell lung, and bladder). Furthermore, the extant data were limited to tumors undergoing whole exome sequencing, which is not widely used in routine clinical care. In practice, most tumors are profiled with targeted gene panels sequenced at high depth.

Recently, we performed a study linking genomic and clinical data in a large cohort of patients with advanced cancer treated at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC).16 Our study included 1,662 patients representing 10 cancer types treated with ICIs (anti-CTLA-4 or anti-PD-1/PD-L1 drugs). TMB was defined as the number of nonsynonymous mutations from the MSK-IMPACT gene panel (341 or 410 genes) normalized by the number of megabases sequenced. Examining tumors by their TMB rank within the same cancer type, we observed a clear dose-response relationship between TMB and overall survival from the time of ICI initiation. Patients whose tumors were in the top 10% of TMB within histology experienced longer overall survival than patients in the 10–20% range, whose overall survival was longer than those in the lowest 80%. This effect was seen across a wide range of cut-points, ranging from top 10% to top 50% within histology, showing that this association was robust and not dependent on a specific threshold. Higher TMB was also associated with better objective response rates and progression-free survival for cancer types with available response data.

In a comparison cohort of 5,371 MSKCC patients who had never received treatment with ICI drugs, there was no association between TMB and survival, showing that the association between TMB and survival in ICI-treated patients is unlikely to reflect a general prognostic effect of TMB. Instead, the association of TMB with outcome is specific to the context of immunotherapy, indicating that TMB is a predictive, but not a prognostic, biomarker. The fact that these associations were present for a TMB value determined from genomic sequencing of a small percentage (approximately 3%) of the exome by MSK-IMPACT suggests that targeted panels may be able to estimate TMB with sufficient predictive value to be clinically useful.

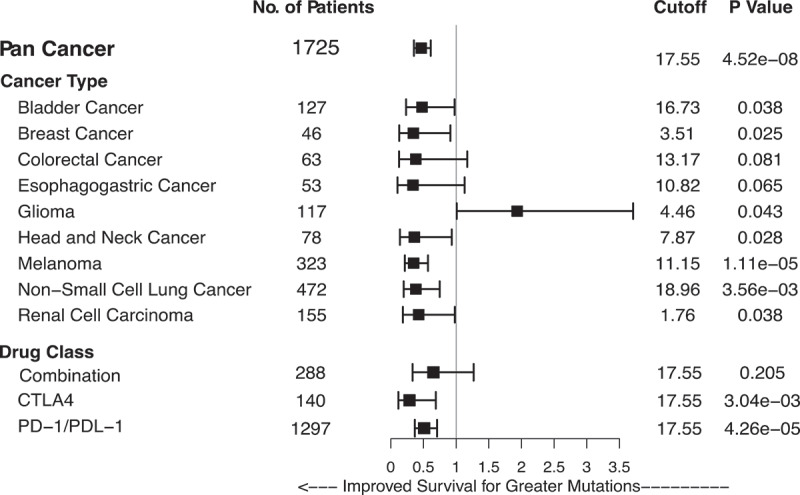

However, an important quality of TMB revealed by our study was that the cutoff defining high TMB, and the optimal predictive cut-point for clinical benefit, varied markedly between cancer histologies. Within this dataset, an exploratory analysis to determine the optimal TMB cut-point that discriminates longer overall survival can be determined for each cancer type. Indeed, this value appears likely to differ markedly between cancer types (Figure 1). It should be noted that this type of analysis to determine optimal cutpoints must be considered hypothesis-generating, and furthermore, is likely to also vary by sequencing platform. For these reasons, it seems unlikely that a single universal value of TMB would have predictive value for ICI treatment decision-making in a tissue-agnostic manner, even if there is an underlying association between TMB and response that is present in most cancer types.

Figure 1.

Higher TMB is associated with longer overall survival in many cancer types. Tumor-normal pairs were sequenced with the targeted MSK-IMPACT next-generation sequencing panel, and an exploratory analysis performed to plot survival by optimal cutoffs. Forest plot shows hazard ratio for overall survival, with the optimal TMB cutoff determined by maximum chi-squared analysis.

Does TMB hold promise as a tissue-agnostic indication for ICIs?

In 2017, pembrolizumab, an anti-PD-1 agent, received the first tissue-agnostic approval by the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the indication of solid tumors of any histology harboring microsatellite instability (MSI).17 Since MSI-high tumors have very elevated mutational loads as a result of DNA mismatch repair deficiency, some have debated whether additional tissue-agnostic approvals are feasible for similar markers such as high TMB.

In the case of MSI, it is not yet completely understood if the association between MSI and ICI response differs by cancer site or histology. The data that led to the FDA-accelerated approval of pembrolizumab for MSI-high tumors were aggregated from mostly non-controlled, phase II clinical trials that included a total of 149 patients across 15 cancers, of which, only 59 patients had non-colorectal cancers. Of the 15 cancer types, 7 had only 1 patient and 2 had only 2 patients. For instance, these trials included only one patient with sarcoma. Subsequent literature has confirmed that MMR deficient sarcomas indeed tend to have higher TMB, but unfortunately, none of 3 MSI-high sarcoma cases in a recent study responded to ICIs.18 Therefore, at present, the association between MSI and response to ICIs, while very promising, has not been confirmed to be identical across a large number of solid tumor types. The FDA-accelerated approval process requires confirmatory studies to be performed, which will hopefully allow for a better understanding of how high TMB associated with MMR deficiency modulates ICI response.

Given that we have yet to fully understand how cancer site affects the association of MSI with ICI response, the association of high TMB, outside of the MSI context, certainly requires additional confirmation. Although using TMB as a tissue-agnostic indication for ICI therapy may increase the pool of patients that benefit from this promising treatment modality, it will also dramatically increase the number of cancer patients receiving ICI therapy, and it remains unclear how many will benefit. There are several caveats regarding TMB as a tissue-agnostic indication, analogous to the issues surrounding MSI. First, data from our study showed marked variability between cancer types in the distribution of TMB (Table 1).16 This implies that a universal cutoff for “high TMB” is unlikely to be possible, and that each cancer type will need its own cutoff (Figure 1). If a single cutoff is chosen, a bias will be introduced towards cancer types with higher TMB. Additionally, while our data indicate that TMB has predictive value across a large number of cancer types, it is quite possible that there are cancer types in which TMB has minimal or no predictive value. Data from our study and others indicate that, at the moment, there is no clear evidence for single nucleotide variant-derived TMB measures having predictive value for ICI therapy in gliomas and renal cell cancers.

Table 1.

Tumor mutational burden as determined by MSK-IMPACT next-generation sequencing by cancer type.

| Variable | N | Mean | SD | Median | IQR | 80th Percentile |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bladder cancer | 214 | 12.9 | 17.8 | 7.9 | 10.4 | 17.6 |

| Breast cancer | 45 | 5.4 | 7.7 | 3.9 | 3.6 | 5.9 |

| Cancer of unknown primary | 90 | 10.5 | 15.2 | 5.3 | 8.2 | 14.7 |

| Colorectal cancer | 110 | 26.7 | 37.2 | 7.9 | 39.5 | 55.6 |

| Esophagogastric cancer | 126 | 8.3 | 10.9 | 5.6 | 4.7 | 8.8 |

| Glioma | 117 | 7.8 | 13.8 | 4.4 | 3.0 | 5.9 |

| Head and neck cancer | 138 | 7.1 | 8.3 | 5.3 | 5.9 | 10.5 |

| Melanoma | 321 | 18.6 | 8.9 | 8.9 | 20.6 | 30.7 |

| Non-small cell lung cancer | 350 | 9.9 | 10.0 | 6.9 | 8.3 | 14.0 |

| Renal cell carcinoma | 151 | 4.3 | 2.9 | 3.9 | 2.6 | 5.9 |

Our study was the largest to date that analyzed the relationship between TMB and clinical outcomes in cancer patients treated with immune checkpoint blockade. Our data support the importance of this biomarker across many cancer types. Despite being clearly biologically important, there are several remaining issues that need to be resolved: lack of research into the optimal agent for patients with high TMB, the practicalities of measuring TMB in the real world, and the complex, multifactorial mechanisms responsible for neoantigen generation, presentation, and response.

First, there have been no published prospective studies to date that have compared the effectiveness of ICI versus standard of care therapies for tumors of multiple histologies with high TMB, defined in any way. We view such a prospective trial as a necessary step before considering a tissue-agnostic indication for ICIs based on high TMB.

Second, with regards to issues with real world measurement of TMB, the most pressing is that we do not have a standard protocol for measuring and defining high TMB. A number of different methodologies have been used to measure TMB, including whole genome sequencing, whole exome sequencing, and gene panels, performed in tumor or even in circulating tumor DNA in blood.19 Apart from our study, the published literature consists mostly of whole exome sequencing data, which is not widely used in clinical practice. The cohort in our study was sequenced with targeted next-generation sequencing of tumor-normal DNA pairs. There are no similar sized cohorts of tumors analyzed with other panels, and it is unknown whether these allow for determination of TMB values with the same predictive capacity.14 Currently ongoing harmonization efforts will be necessary to determine whether different molecular diagnostic assays produce TMB results that are equally informative.20

Finally, the focus on TMB should not neglect the complex and multifactorial nature of neoantigen generation, presentation, and response.10 The number of nonsynonymous somatic mutations does not necessarily result in robust tumor rejection. First, novel proteins have to bind to HLA, and the new amino acid sequences may or may not confer strong binding. In addition, the degree of heterozygosity in a person’s HLA alleles affects ICI response, and is likely to influence the diversity of the neoantigen repertoire presented to the immune system.21 Even after recognition of a new antigen, T-cell response is highly variable and depends on a complex interaction between inhibitory and stimulatory signals in the immune microenvironment. With TMB representing only one part of the complex process of neoantigen production, processing, presentation, and T-cell response, it is clear that more comprehensive immunogenomic measures will be needed. We are optimistic that simple but more comprehensive multivariable models incorporating the above factors, and other critical clinicopathologic features, beyond simply TMB, will ultimately allow for more precise, and perhaps tissue-agnostic, prediction of ICI response.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by AACR-AstraZeneca Immunotherapy Fellowship (R.M.S.), Pershing Square Sohn Cancer Research grant (T.A.C.), the PaineWebber Chair (T.A.C.), Stand Up To Cancer (T.A.C.), NIH R01 CA205426 (T.A.C.), the STARR Cancer Consortium (T.A.C.), NCI R35 CA232097 (T.A.C.), Precision Immunotherapy Kidney Cancer Fund (T.A.C.), The Frederick Adler Fund, Cycle for Survival, NIH K08 DE024774 and NIH R01 DE027738 (L.G.T.M.), Fundacion Alfonso Martin Escudero (C.V.), and MSKCC through NIH/NCI Cancer Center Support Grant (P30 CA008748).

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the bravery of our patients in this study, as well as their families, and our colleagues at the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center. We are grateful to members of the Diagnostic Molecular Pathology Service in the Department of Pathology and the Marie-Josée and Henry R. Kravis Center for Molecular Oncology at MSKCC.

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

R.M.S, T.A.C. and L.G.T.M. are inventors on a provisional patent application (62/569,053) filed by Memorial Sloan Kettering (MSK) relating to the use of TMB in cancer immunotherapy. T.A.C. is an inventor on a PCT patent application (PCT/US2015/062208) filed by MSK relating to the use of TMB in lung cancer immunotherapy. MSK and the inventors may receive a share of commercialization revenue from license agreements relating to these patent applications. T.A.C. is a cofounder of Gritstone Oncology and holds equity. T.A.C. holds equity in An2H. T.A.C. acknowledges grant funding from Bristol-Myers Squibb, AstraZeneca, Illumina, Pfizer, An2H and Eisai. T.A.C. has served as an advisor for Bristol-Myers Squibb, Illumina, Eisai and An2H. MSK has licensed the use of TMB for the identification of patients that benefit from immune checkpoint therapy to PGDx. MSK and T.A.C. receive royalties as part of this licensing agreement. L.G.T.M. received consulting fees from Rakuten Aspyrian and speaker fees from Physician Educational Resources.

References

- 1.Leach DR, Krummel MF, Allison JP.. Enhancement of antitumor immunity by CTLA-4 blockade. Science. 1996;271:1734–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hodi FS, O’Day SJ, McDermott DF, Weber RW, Sosman JA, Haanen JB, Gonzalez R, Robert C, Schadendorf D, Hassel JC, et al. Improved survival with ipilimumab in patients with metastatic melanoma. New Engl J Med. 2010;363(8):711–23. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1003466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Seiwert TY, Burtness B, Mehra R, Weiss J, Berger R, Eder JP, Heath K, McClanahan T, Lunceford J, Gause C, et al. Safety and clinical activity of pembrolizumab for treatment of recurrent or metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck (KEYNOTE-012): an open-label, multicentre, phase 1b trial. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17(7):956–65. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(16)30066-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fuchs CS, Doi T, Jang RW, Jang RW, Muro K, Satoh T, Machado M, Sun W, Jalal SI, Shah MA, et al. Safety and efficacy of pembrolizumab monotherapy in patients with previously treated advanced gastric and gastroesophageal junction cancer: phase 2 clinical KEYNOTE-059 trial. JAMA Oncol. 2018;4:e180013–e180013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sharma P, Retz M, Siefker-Radtke A, Baron A, Necchi A, Bedke J, Plimack ER, Vaena D, Grimm M-O, Bracarda S, et al. Nivolumab in metastatic urothelial carcinoma after platinum therapy (CheckMate 275): a multicentre, single-arm, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18(3):312–22. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(17)30065-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goldberg SB, Gettinger SN, Mahajan A, Chiang AC, Herbst RS, Sznol M, Tsiouris AJ, Cohen J, Vortmeyer A, Jilaveanu L, et al. Pembrolizumab for patients with melanoma or non-small-cell lung cancer and untreated brain metastases: early analysis of a non-randomised, open-label, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17(7):976–83. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(16)30053-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nghiem PT, Bhatia S, Lipson EJ, Kudchadkar RR, Miller NJ, Annamalai L, Berry S, Chartash EK, Daud A, Fling SP, et al. PD-1 blockade with pembrolizumab in advanced merkel-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(26):2542–52. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1603702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haslam A, Prasad V. Estimation of the percentage of US patients with cancer who are eligible for and respond to checkpoint inhibitor immunotherapy drugs. JAMA Network Open. 2019;2(5):e192535–e192535. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.2535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kamada T, Togashi Y, Tay C, Ha D, Sasaki A, Nakamura Y, Sato E, Fukuoka S, Tada Y, Tanaka A, et al. PD-1+ regulatory T cells amplified by PD-1 blockade promote hyperprogression of cancer. Proc National Acad Sci. 2019;116(20):9999–10008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Havel J, Chowell D, Chan T. The evolving landscape of biomarkers for checkpoint inhibitor immunotherapy. Nat Rev Can. 2019;19:133–50. doi: 10.1038/s41568-019-0116-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Snyder A, Makarov V, Merghoub T, Yuan J, Zaretsky JM, Desrichard A, Walsh LA, Postow MA, Wong P, Ho TS, et al. Genetic basis for clinical response to CTLA-4 blockade in melanoma. New Engl J Med. 2014;371(23):2189–99. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1406498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rizvi NA, Hellmann MD, Snyder A, Kvistborg P, Makarov V, Havel JJ, Lee W, Yuan J, Wong P, Ho TS, et al. Mutational landscape determines sensitivity to PD-1 blockade in non–small cell lung cancer. Science. 2015;348(6230):124–28. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa1348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hellmann MD, Callahan MK, Awad MM, Calvo E, Ascierto PA, Atmaca A, Rizvi NA, Hirsch FR, Selvaggi G, Szustakowski JD, et al. Tumor mutational burden and efficacy of nivolumab monotherapy and in combination with ipilimumab in small-cell lung cancer. Cancer Cell. 2018;33(5):853–61. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2018.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goodman AM, Kato S, Bazhenova L, Patel SP, Frampton GM, Miller V, Stephens PJ, Daniels GA, Kurzrock R. Tumor mutational burden as an independent predictor of response to immunotherapy in diverse cancers. Mol Cancer Ther. 2017;16(11):2598–608. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-17-0386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rosenberg JE, Hoffman-Censits J, Powles T, van der Heijden MS, Balar AV, Necchi A, Dawson N, O’Donnell PH, Balmanoukian A, Loriot Y, et al. Atezolizumab in patients with locally advanced and metastatic urothelial carcinoma who have progressed following treatment with platinum-based chemotherapy: a single-arm, multicentre, phase 2 trial. Lancet. 2016;387(10031):1909–20. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00561-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Samstein RM, Lee C-H, Shoushtari AN, Hellmann MD, Shen R, Janjigian YY, Barron DA, Zehir A, Jordan EJ, Omuro A, et al. Tumor mutational load predicts survival after immunotherapy across multiple cancer types. Nat Genet. 2019;51(2):202–06. doi: 10.1038/s41588-018-0312-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.United States Food and Drug Administration . FDA approves first cancer treatment for any solid tumor with specific biomarker. [Accessed March 3, 2019] https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-first-cancer-treatment-any-solid-tumor-specific-genetic-feature. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Doyle LA, Nowak JA, Nathenson MJ, Thornton K, Wagner AJ, Johnson JM, Albrayak A, George S, Sholl LM. Characteristics of mismatch repair deficiency in sarcomas. Mod Pathol. 2019. doi: 10.1038/s41379-019-0202-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stenzinger A, Allen JD, Maas J, Stewart MD, Merino DM, Wempe MM, Dietel M. Tumor mutational burden standardization initiatives: recommendations for consistent tumor mutational burden assessment in clinical samples to guide immunotherapy treatment decisions. Genes Chromosomes Can. 2019;58(8):1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Allgäuer M, Budczies J, Christopoulos P, Endris V, Lier A, Rempel E, Volckmar A-L, Kirchner M, von Winterfeld M, Leichsenring J, et al. Implementing tumor mutational burden (TMB) analysis in routine diagnostics—a primer for molecular pathologists and clinicians. Transl Lung Can Res. 2018;7(6):703–15. doi: 10.21037/tlcr.2018.08.14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chowell D, Morris LG, Grigg CM, Weber JK, Samstein RM, Makarov V, Kuo F, Kendall SM, Requena D, Riaz N, et al. Patient HLA class I genotype influences cancer response to checkpoint blockade immunotherapy. Science. 2018;359(6375):582–87. doi: 10.1126/science.aao4572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Citations

- United States Food and Drug Administration . FDA approves first cancer treatment for any solid tumor with specific biomarker. [Accessed March 3, 2019] https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-first-cancer-treatment-any-solid-tumor-specific-genetic-feature. [DOI] [PubMed]