Abstract

Background

Malaria is a major public health problem affecting humans, particularly in the tropics and subtropics. Children under 5 years old are the group most vulnerable to malaria infection because of less developed immune system. Countries have set targets that led to control and eliminate malaria with interventions of the at-risk groups, however malaria infection remained a major public health challenge in endemic areas.

Objective

This study aimed at determining the magnitude of malaria and associated factors among febrile children under 5 years old in Arba Minch “Zuria” district.

Methods

The study was conducted from April to May 2017. Blood samples were collected from 271 systematically selected febrile children under 5 years old. Thin and thick blood smears were prepared, stained with 10% Giemsa and examined under light microscope. Data of sociodemographic data, determinant factors, and knowledge and prevention practices of malaria were collected using a pretested structured questionnaire. Data were analyzed using binomial and multinomial regression model in SPSS® Statistics program, version 25.

Results

Among those febrile children, 22.1% (60/271) were positive for malaria; 50.0%, 48.33% and 1.66% of them were positive for Plasmodium falciparum, Plasmodium vivax and mixed infections of both parasites, respectively. Malaria infection was associated with nearby presence of stagnant water to resident areas (AOR=8.19; 95%CI: 3.62-18.5, P<0.0001). Children who slept under insecticide-treated mosquito nets (ITNs) were more likely to be protected from malaria infection than those did not sleep under an ITNs (AOR=9.65; 95%CI: 4.623-20.15, P<0.0001).

Conclusion

Malaria infection is highly prevalent in children aged between 37 and 59 months old, in Arba Minch “Zuria” district. The proximity of residence to stagnant water and the use of ITNs are the most dominant risk factor for malaria infection. Improved access to all malaria interventions is needed to interrupt the transmission at the community level with a special focus on the risk groups.

Keywords: malaria, Plasmodium, children, febrile illness, intervention

Introduction

Globally about 3.2 billion people are at risk of malaria and an estimated 212 million cases were reported worldwide, leading to 429,000 deaths in 2015, particularly in parts of sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia, Latin America and the Middle East countries.1 However, malaria is declining in Africa, in some areas the burden of malaria has remained unchanged or increased. In 2016, approximately 216 million clinical cases and about 450,000 deaths reported in worldwide.2 Malaria is caused by five protozoan species, namely Plasmodium falciparum, P. vivax, P. malariae, P. ovale, and P. knowlesi. The deadliest of these is P. falciparum which is predominant in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA).3

Malaria is a major factor for poverty in resource-poor settings, particularly in tropical regions throughout the world. Some population groups are at considerably higher risk of contracting malaria, and developing severe disease including infants, children under 5 years old, pregnant women, and patients with HIV/AIDS as well as non-immune migrants, mobile populations and travelers.4 The impact of malaria also extends beyond health facilities to homes and everyday lives: children may develop long-term neurological sequelae following severe malaria attacks, further subtle developmental and cognitive impairments as a result of both severe and uncomplicated episodes, and families also face substantial economic consequences5

Children under five years old are among the most vulnerable to malaria infection as they have not yet developed any immunity to the disease. Children who survive malaria may suffer long-term consequences of the infection. Repeated episodes of fever and illness reduce appetite and restrict play, social interaction, and educational opportunities, thereby contributing to poor development. Child mortality rates are known to be higher in poorer households and malaria is responsible for a substantial proportion of these deaths.6

Malaria is a leading public health problem in Ethiopia where, approximately 68% of the land mass of the country have favorable conditions for malaria transmission, and 60% of the population are at risk. Many Ethiopians communities have unstable and seasonal, usually characterized by frequent focal, and from low-to-high of malaria transmission.7 It is a reason in these endemic areas that results in low host immunity. The major transmission follows June to September rains and occurs between September and December in almost every part of the country while the minor transmission season occurs between April and May following the February to March rains.8 P. falciparum (70%) and P. vivax (30%) are the common causes of malaria.9 The primary malaria vector in the country is Anopheles arabiensis and the secondary vector is Anopheles pharoensis.10

Currently, there are challenges such as identifying optimum mechanisms to maintain high Insecticide Treated Net (ITN) coverage between mass-distribution campaigns, improved case management at facility and community level, and overcoming behavioral challenges to encourage correct and consistent use of ITNs and reduce presumptive use of artemisinin-combination therapies, both by health workers and community members.11,12 Although the magnitude of malaria infection was reported by health departments as major top disease in the population, there is limited information on the prevalence of malaria among febrile children under 5 years old attending health facilities and associated determinant factors. This result provides a clue on maintaining of asymptomatic reservoir of malaria among children due to the magnitude of the parasite in younger children. It is also important to consider and implement malaria interventions to achieve elimination target.

The aim of the present study was therefore to provide current information on the magnitude of malaria infection at health center level in an unstable malaria endemic area in South Ethiopia from where there is no published data concerning children under five years. In addition, the study aimed at identifying determinant factors associated with Plasmodium infection in this population.

Methods and Materials

Study Area and Period

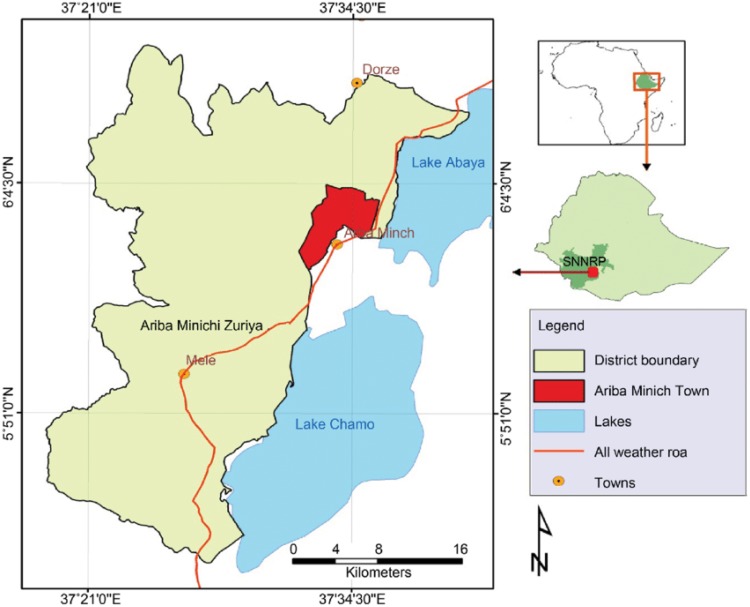

The study was conducted around Arba Minch Zuria district (AZD) kebele in Kolla-Shele health center from April to May, 2017. AZD is one of the districts of Gamo zone in the South, Ethiopia. Kolla-Shele health center is located about 27 km from Arba Minch town and 532 km from Addis Ababa. According to the centeral statistical agency of Ethiopia(CSA,2007), the total population of the district is 164,529 of whom 82,330 are men and 82,330 women. The area lies between 1200 and 3125 meters above sea level (ASL), with an average rainfall from 750 mm3 to 930 mm3 with mean annual temperature range 16 to 37°c. Malaria transmission is highly seasonal, and markedly unstable. The study area has an entomological inoculation rate of 17.1 infectious bites per person per year.13 Malaria infection is primary due to P. falciparum. Subsistence farming and fishing are the main occupation in the area. Water for mosquito breeding is available throughout the year because of rivers such as the Sille and Elgo, and Lake Chamo (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Location map of Arba Minch Zuria district (Google Map).

Study Design

This is an institution based cross-sectional study conducted from April to May 2017 in children under five years old (children aged between 12 months and 59 months). Children under 5 years old who attend the health center were the source population, and those children under 5 years with febrile cases who attended in the health center during the study period were the study population. Children <12 months old, and children <5 years’ old who did underwent chemotherapy with antimalaria drugs three months prior to the study commencing and during the study were excluded.

Sample Size Determination and Sampling Technique

The sample size was calculated using single population proportion formula based on a prevalence rate of 22.8% as reported by a study of Haile Mariam and Gebre.14 A sample size of 271 children was calculated with the assumption of 22% expected prevalence, 0.05 margin error and 10% non response rate. Systematic random sampling technique was used to select the study participants, and then blood samples and sociodemographic data were taken and analyzed as outlined in the next section.

Semi-Structured Questionnaire Data

Parents or guardians of eligible of children were given oral informed assent to allow the children to participate in the study. Data of sociodemographic, economic, and environmental were collected from their parents/caregivers using structured and pretested questionnaire using trained data collectors. Data including sex, age, caregivers age, level of education, place of residence (rural or urban), important points about knowledge of malaria, type of block of the house, type of the ceiling of the house, ownership and number of ITNs, usage of ITNs, IRS with in the six months prior to the survey and other relevant demographics were collected from the selected children’s parents or guardians visiting the health center. All data of sociodemographic data, determinant factors, and knowledge and prevention practices of malaria were prepared and reviewed by the investigative team including data collection. All information on questionnaire was standard and adapted from the national malaria survey of Ethiopia and other published research on reputable journals. The questionnaire was developed in English language and was translated into Amharic and local languages.

Blood Specimen Collection and Processing

Capillary blood specimen was collected from finger prick or big toe aseptically using sterile blood lancet to prepare thick and thin blood film smears. Blood specimen collection and processing was done by medical laboratory professional of Shele health center while children attending the health center due to febrile illness. In brief, the smears were air dried. Thin films were fixed with methanol, and both thin and thick films were stained with 10% Giemsa stain for 15 minutes. All dried slides placed in slides boxes and were examined by laboratory technologist at the health center laboratory in Kolla Shele. The presence of malaria parasites on thick blood smear and the identification of Plasmodium species from smear was done, through oil immersed objective (100×), at 1000× magnification. The thick smear was used to determine whether the malaria parasites were present or absent and thin smear was used to identify the type of Plasmodium species. During the microscopic examination, a slide was regarded as negative after 200 fields had been examined without finding of Plasmodium parasite by two laboratory technologists. To assure quality of the microscopic examinations, all positive and 10% of the negative slides were reexamined by a third reader to remove discrepant result.

Data Quality Assurance

To maintain the quality of the data, Standard Operating Procedure (SOP) was used and followed in each step of the test procedures and structured questionnaires and a check list was used. The working solution of Giemsa was prepared by filtering the crystals. In addition, the glass slides were labeled in such a way that the slide code matched the file of the particular individual. During blood sample collection one sterile lancet was used per one child and a color atlas was used during microscopic examination and the smear was examined by three readers.

Data Analysis

The data was analyzed using binomial and multinomial regression models. Bivariate and multivariate logistic regression, and chi-squared tests were used to assess the association between dependent and independent variables. During analysis P-value <0.05 was considered as statistically significant. The analysis was performed using SPSS® Statistics program, version 25 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

Sociodemographic Characteristics of Children

A total of 271 febrile children under five years old were included in this study. One hundred fifty-seven (58.0%) were males and 114 (42.0%) were females. Of these, 91 (33.6%), 87 (32.1%) and 93 (34.3%) were children were between 12 and 24, 25 and 36 and 37 and 59 months, respectively. The mean age was 31.2 months. The minimum and maximum age of the children were 12 and 59 months respectively (Table 1).

Table 1.

Sociodemographic Characteristics of Children Under 5 Years, in Arba Minch Zuria District, South Ethiopia, 2017

| Total (n=271) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Variables | n (%) | |

| Residence | Rural | 113 (41.7) |

| Urban | 158 (58.3) | |

| Sex | Male | 157 (58.0) |

| Female | 114 (42.0) | |

| Age, months | 12–24 | 91 (33.6) |

| 25–36 | 87 (32.1) | |

| 37–59 | 93 (34.3) | |

Plasmodium Parasite Distribution with Sociodemographic Variables

The overall prevalence of Plasmodium malaria was 60 (22.1%) in this study. Of these, males were 32 (53.4%), females were 28 (46.6%). Malaria prevalence in sex was not statistically significantly different (P=0.5). Among Plasmodium parasite infected children, 26 (27.9%), 22 (25.3%) and 12 (13.1%) were age group between 37 and 59, 25 and 36, and 12 and 24 months, respectively. Younger children had a low prevalence of Plasmodium parasite with statistically significant difference (P<0.05). There was higher prevalence of malaria parasite in rural residents’ children 40 (25.3%) compared to urban residents of children 20 (18.5%). The difference was not statistically significant in the different place of residents (P=0.1). Among those who had positive malaria result, the dominant Plasmodium species were P. falciparum 30 (50.0%), followed by P. vivax 29(48.33%), the remaining one (1.66%) showed mixed infections of P. falciparum and P. vivax (Table 2).

Table 2.

Sociodemographic Variables and Malaria Infection among Children Under 5 Years, in Arba Minch Zuria District, South Ethiopia, 2017

| Characteristics | n | Positive n (%) | P. falciparum n(%) | P. vivax n (%) | Mixed n(%) |

Negative n (%) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Male | 157 | 32 (20.4) | 17 (53.1) | 14 (43.7) | 1 (3.1) | 125 (79.6) | 0.5 |

| Female | 114 | 28 (24.5) | 13 (46.4) | 15 (53.5) | – | 86 (75.5) | ||

| Age, months | 12–24 | 91 | 12 (13.1) | 9 (75.0) | 3 (25.0) | – | 79 (86.8) | 0.04 |

| 25–36 | 87 | 22 (25.3) | 10 (45.4) | 11 (50.0) | 1 (1.15) | 65 (74.7) | ||

| 37–59 | 93 | 26 (27.9) | 12 (46.0) | 14 (53.8) | – | 67 (72.0) | ||

| Residence | Urban | 113 | 20 (18.5) | 12 (60.0) | 9 (45.0) | – | 93 (41.7) | 0.1 |

| Rural | 158 | 40 (25.3) | 18 (45.0) | 11 (27.5) | 1 (2.5) | 119 (58.3) | ||

| Total | 271 | 60 (21.1) | 30 (50.0) | 29 (48.4) | 1 (1.66) | 211 (77.9) | ||

Prevalence of Malaria and Knowledge of Parents/Caregivers

About 117 (43.2%) of parents/caregivers had not been attended formal education; whereas 154 (56.8%) had attained various levels of formal education. High prevalence of parasitic infection 20 (25.0%) and 28 (23.9%) were observed in parents who are primary attendants and illiterate, respectively. Among 271 parents/caregivers, 254 (93.7%) believed that malaria can be a curable disease. A total of 184 (67.9%) had a knowledge of malaria transmissibility between individuals in this study. One hundred ninety-three (71.2%) participants had a knowledge that mosquitoes are a vector for the transmission of malaria. On the contrary, high prevalence of malaria was observed among the parents who had knowledge about mosquitoes. Although high prevalence of malaria was observed, knowledge about the breeding site of mosquitoes was answered by 202 (74.5%) of the study participants. Similarly, 185 (68.2%) parents were well informed about the importance of using ITNs as prevention of malaria. However, a high number of study participants did not have information on IRS which is the primary method of malaria prevention (Table 3).

Table 3.

Sociodemographic Characteristics and Knowledge of Parents/Caregivers with the distribution of malaria among Children under 5 years, in AZW District, South Ethiopia

| Knowledge | Variables | Total n (%) | Positive n (%) | Negative n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Level of education | Illiterate | 117 (43.2) | 28 (23.9) | 89 (76.1) |

| Read and write | 47 (17.0) | 9 (19.1) | 38 (80.9) | |

| Primary education | 80 (29.2) | 20 (25.0) | 60 (75.0) | |

| Secondary education | 17 (6.3) | 2 (11.8) | 15 (88.2) | |

| Higher education | 10 (3.7) | 1 (10.0) | 9 (90.0) | |

| Malaria is curable | Yes | 254 (93.7) | 56 (22.0) | 198 (78.0) |

| No | 17 (6.3) | 4 (23.5) | 13 (76.5) | |

| Malaria is transmittable | Yes | 184 (67.9) | 43 (23.4) | 141 (76.6) |

| No | 42 (15.5) | 8 (19.0) | 34 (81.0) | |

| I do not know | 45 (16.6) | 9 (20.0) | 36 (89.0) | |

| Malaria can be prevented | Yes | 268 (98.9) | 59 (22.0) | 209 (78.0) |

| No | 3 (1.1) | 1 (33.3) | 2 (66.7) | |

| Mode of transmission | Bite of mosquitoes | 193 (71.2) | 46 (23.8) | 147 (72.2) |

| Patient contact | 3 (1.1) | 1 (33.3) | 2 (66.7) | |

| Dirty water | 34 (12.5) | 6 (17.6) | 28 (82.4) | |

| Weather | 41 (15.1) | 7 (17.1) | 34 (82.9) | |

| Breeding site of mosquitoes | Stagnant water | 202 (74.5) | 49 (24.3) | 153 (75.7) |

| Running water | 36 (13.2) | 8 (22.2) | 28 (77.8) | |

| Soil | 13 (4.8) | 1 (77.7) | 12 (92.3) | |

| Do not know | 20 (7.4) | 2 (10.0) | 18 (9.0) | |

| Method of malaria prevention mentioned | ITN | 185 (68.2) | 42 (22.7) | 143 (77.3) |

| IRS | 2 (66.7) | 0 | 2 | |

| Drug | 29 (10.7) | 6 (20.7) | 23 (79.3) | |

| Environmental management | 55 (20.3) | 12 (21.8) | 43 (78.2) |

Malaria Positivity with Respect to Determinant Factors

Fifty (38.2%) of malaria infection was observed in children who live near to mosquitoes breeding site in this study. Children who also live near to the health facilities and those who live at distant from health facilities did not have difference in malaria positivity. Households who had an ITNs were more protected than those who lacked an ITN. Number of ITNs per household had also differences in malaria positivity. The prevalence malaria on those children who slept under an ITN was 6.7%, indicating that a highly significant number of children were more protected in the study area (Table 4).

Table 4.

Determinant Factors with respect to the distribution of malaria parasite among Children under 5 years, in AZW District, South Ethiopia, 2017

| Variables | Malaria Status | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total n (%) | Positive n (%) | Negative n (%) | ||

| Mosquitoes breeding site in residents | Yes | 131 (48.4) | 50 (38.2) | 81 (61.8) |

| No | 140 (51.6) | 10 (7.1) | 130 (92.9) | |

| Nearby to health facilities | Yes | 261 (96.3) | 57 (21.8) | 204 (78.2) |

| No | 10 (3.7) | 3 (30.0) | 7 (70.0) | |

| Distance from Health center, hours | ≤1 hr | 193 (71.2) | 41 (21.2) | 152 (78.8) |

| >1hr | 97 (28.8) | 19 (24.9) | 78 (75.6) | |

| Availability of ITN | Yes | 235 (86.7) | 48 (20.4) | 187 (79,6) |

| No | 36 (23.3) | 12 (33.3) | 24 (66.7) | |

| Number of ITN/house | 0 | 36 (23.3) | 12 (33.3) | 24 (66.7) |

| 1 | 59 (21.7) | 12 (20.3) | 47 (79.2) | |

| 2 | 153 (56.5) | 34 (22.2) | 119 (77.8) | |

| 3 | 23 (8.5) | 2 (8.7) | 21 (91.3) | |

| Structure of house | Grass thatched | 82 (30.2) | 23 (28.0) | 59 (72.0) |

| Made of mud | 177 (65.3) | 35 (19.8) | 142 (80.2) | |

| Semi-permanent | 12 (4.5) | 2 (16.7) | 10 (83.3) | |

| <5 sleeping under ITN | Yes | 149 (55.0) | 10 (6.7) | 139 (93.3) |

| No | 122 (45.0) | 50 (41.0) | 72 (59.0) | |

| Number of beds suitable for ITN hanging | >2 | 3 (1.1) | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | 77 (28.4) | 14 (18.2) | 63 (81.8) | |

| 1 | 182 (67.1) | 41 (22.5) | 141 (79.5) | |

| 0 | 9 (3.4) | 5 (55.6) | 4 (44.4) | |

Factors Associated with Malaria Infections

Among the determining factors identified regarding the Plasmodium parasite positivity age being 25–36 and 37–59 months compared to an age of 12–24 months, the availability of ITN compared to absence of ITN in the household; number of beds/household; children sleeping under ITN and compared to sleeping not under an ITN were significantly associated with positive test result for malaria. Compared to age group between 37 and 59 months old (crude OR [cOR]= 2.55; 95%CI: 1.19–5.88), those between 25 and 36 months were more likely to have positive test result for malaria (cOR=2.28; 95%CI: 1.02–4.84) as compared to those in the age group between 12 and 24 months old. Residents near to mosquito breeding site were more likely to have positive test result for malaria infections (adjusted OR [aOR]=8.19; 95%CI:3.62–18.5, P=0.0001) as compared to those who live far from mosquitoes breeding site. Children who slept under an ITN at night time were more likely to be protected from malaria parasite (aOR = 9.65; 95%CI: 4.623–20.15, P= 0.0001) as compared to those children who did not utilize an ITN (Table 5).

Table 5.

Binary and Multivariate Logistic Regression for Determinants Factors of Malaria Infection Among Children under 5 years, in AZW District, South Ethiopia, 2017

| Variables | Positive n, (%) | Negative n, (%) | COR (95%CI) | AOR (95%CI) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mosquitoes breeding site in residents | Yes | 50 (38.2) | 81 (61.8) | 8.18 (3.85–16.71)* | 8.19 (3.62–18.5)* | 0.0001 |

| No | 10 (7.1) | 130 (92.9) | 1 | |||

| Nearby to health facilities | Yes | 57 (21.8) | 204 (78.2) | 1 | 0.79 (0.132–4.79) | 0.8 |

| No | 3 (30.0) | 7 (70.0) | 0.5 (0.384–6.21) | |||

| Distance from health center, hours | <1hr | 41 (21.2) | 152 (78.8) | 1 | 1.22 (0.53–2.776) | 0.5 |

| >1hr | 19 (24.9) | 78 (75.6) | 0.5 (0.64–2.233) | |||

| Availability of ITN | Yes | 48 (20.4) | 187 (79,6) | 0.8 (0.909–4.174) * | 1.248 (0.177–8.97) | 0.8 |

| No | 12 (33.3) | 24 (66.7) | 1 | |||

| <5 children sleeping under ITN | Yes | 10 (6.7) | 139 (93.3) | 1 | 9.65 (4.623–20.15)* | 0.0001 |

| No | 50 (41.0) | 72(59.0) | 9.6 (4.62–20.16)* | |||

| Number of beds suitable for ITN hanging | 2 | 14 (17.7) | 65 (82.3) | 1 | 0.66 (0.312–1.401) | 0.2 |

| 1 | 41 (22.5) | 142 (77.6) | 0.3 (1.381–2.93) | |||

| 0 | 5 (55.6) | 4 (44.4) | 0.01 (1.381–24.398)* | |||

Note: * indicates P<0.05 statistically significant.

Discussion

This present study showed that malaria is a public health problem among children under 5 years old in the study site. The study revealed that the overall malaria prevalence was 21.0%. It is also aimed to determine the major determinant factor for high prevalence of malaria. This finding was consistent with a prior study in Ethiopia; the prevalence of malaria was 22.8% in children under five in Arsi Negele, Ethiopia. It was a retrospective study and the result was more limited and did not show determining factors.14 The present study is similar to another study conducted in Mali; the prevalence increased from the previous years, however many interventions in children under 5 years old.15 In contrast, a study which was conducted in villages surrounding Lake Langano, Oromia region, Ethiopia showed a much higher prevalence of malaria 66.4%.16 This difference might be seasonal variation for high prevalence of malaria parasite in the study site. Contrary to this, our study was conducted in a minor malaria transmission season. Additionally, the prevalence was low as compared to a study of India which was 36.6% in children under 5 years old in malaria endemic forest villages. However, the variation in parasite species might be due to rapid diagnostic test (RDT) of the study.17

In contrast with other findings of Plasmodium infection, febrile illness increases with increasing age of a children in this study. There might be an evidence for the occurrence; these children live in unstable malaria transmission endemic areas and are not as capable of producing protective immunity as those children who live in areas of high malaria transmission intensity to develop age-related immunity due to the continuous exposure to infective mosquito bites.18,19

The present study tried to investigate sociodemographic, household structure and availability of bed nets of the participants were not significantly associated with malaria infection; this agreed with research conducted in Uganda. However, there were lack knowledge about breeding site of mosquito and mode of transmission, in some of the participants similar to the previous study in Uganda20 compared to this study. Inconsistent with our finding, sociodemographic factors, use of mosquito nets and unimproved conditions of housing structure were associated with higher malaria prevalence.21

About 79.3% of the study participants were aware of the fact that Plasmodium is the cause of death in malaria endemic areas. Of the 271 parents/caregivers, 71.2% knew about the mode of malaria transmission via mosquitoes’ bite. This result was relatively similar when compared to other African courtiers, Uganda (77.6%)22 and Kampala (84%).23

According to WHO malaria control and elimination strategies, access to all interventions enhance reduction in malaria, mainly, implementing improved case management, and scale-up of long-lasting insecticidal nets (LLINs) and indoor residual spraying (IRS) and early diagnosis and treatment and environmental managements.2 However; coverage and the utilization of ITN was high, still IRS has not been largely implemented and known as one of the major vector control measures in household of study participants. The study results in the need to increase the coverage of IRS, and other interventions together with ITNs in order to reduce the burden and transmission of malaria particularly for high risk groups of the population.

Among the study participants, 72.0% knew the suitable breeding site of mosquitoes is stagnant water. Several studies have showed malaria vector density and living in the nearest proximity of water body like river and streams could be an important factor influencing malaria transmission.24,25 Based on the study the presence of mosquito breeding site near to their residents was significantly associated with malaria infection; this finding was similar with a previous study in Tanzania. It also indicated that significant association between age, sex and marital status with prevalence of malaria,26 however; this was contradicted with the present study that revealed no significant association between age, sex and residence.

ITN availability was observed among 86.7% participants. Despite the fact that the use of ITNs is considered as one of the protective methods, it was further being identified that the prevalence of malaria among those who were using the ITNs was not significantly observed as compared to those who were not using ITN. However, this is not always significantly associated with reduced malaria prevalence. The utilization of ITN is a powerful vector control tool for prevention of malaria transmission.2 This study revealed that those children who slept under ITN decreased 9.65 times the risk of malaria positivity compared to those who did not sleep under ITN. This result is supported by a study conducted in Hadiya zone which stated that those who did not use bed nets were more likely to be infected.27 Moreover, another study also showed that individuals who did not use mosquito nets at night were more likely to have malaria than those who did.21

A two-year prospective cohort study done at Arba Minch Zuria district, Ethiopia showed that the ITNs use fraction reached 69%, but the utilization in under 5 year old children it was very low.28 Similarly, there was high percentage (93.3%) access for ITN by parents’/caregivers, still it is not considerably applied for under 5 year old children. However, children who slept under ITN was 55.0% and they were significantly (aOR, 9.65; (4.623–20.15, P=0.0001) protected from malaria infection as compared to children who did not sleep under ITN in this study. Considering utilization, this result is not extended as a sub-Saharan Africa ITN utilization; the proportion of children under 5 years old and sleeping under ITNs much more increased from <2% in the year 2000 to an estimated 68% (95%CI: (61–72%) in 2015.29 In contrast, a study which conducted in Gamo-Gofa zone, Ethiopia identified that only 37.2% of children under 5 years of age utilized ITNs at a night time.30 Since our study is a cross sectional study and without evidence of follow-up observation, the interpretation of results is limited concerning the utilization of ITNs by households. However, the result showed the significance of ITNs agreeing with the percentage of ITNs use by households. Thus, longitudinal study design would be valuable in the future. Since this study was conducted in minor malaria transmission season; the result may vary from the major transmission seasons of the study area. The study has limitations due to no additional information regarding data of infected Anopheles’ mosquitoes that live close with the population and observation of households.

Conclusion

Malaria infection is highly prevalent in children under 5 years old particularly those aged between 37 and 59 months old, in Arba Minch “Zuria” district. The proximity of residence to stagnant water and the use of ITNs are the most dominant risk factors for malaria infection. Improved access to all malaria interventions is needed to interrupt the transmission at the community level with a special focus on the at-risk group.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Arba Minch University for giving ethical clearance and providing necessary materials. The authors are grateful for Shele health center laboratory professionals and parents/caregivers as well as study participants. The abstract of this paper was presented at Ethiopian Public Health Association (EPHA) annual conference as poster presentation talk with interim findings. The poster abstract was published in “Poster Abstracts” in EPHA website.

Abbreviations

AZD, Arba Minch Zuria district; IRS, indoor residual spraying; ITNs, insecticide-treated nets; FMOH, Federal Ministry of Health; LLINs, long lasting insecticidal nets; WHO, World Health Organization.

Ethics Approval and Informed Consent

Ethical clearance was obtained from ethical committee of Arba Minch University, College of Medicine and Health Sciences. Health Sciences Research coordination office approved with session. Department of Medical Laboratory Sciences provided letter to conduct the study in Shele Health Center. We also obtained permission with written informed consent from parents/caregivers of children. Confidentiality will be kept for the information obtained from the participants. Study participants whose blood examination positive for malaria infection were treated using the standard guideline by the attending health professionals. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Data Sharing Statement

The original data for this study is available from the corresponding author.

Author Contributions

AA, TY Conception of the research idea, designing, data analysis and interpretation. AN, WT Designing and collection of data. MD Manuscript drafting and revised the paper. All authors contributed to data analysis, drafting or revising the article, gave final approval of the version to be published, and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.WHO. World Malaria Report 2016. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 2.WHO. Global Vector Control Response 2017–2030. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gething PW, Elyazar IR, Moyes CL, et al. A long-neglected world malaria map: Plasmodium vivax endemicity in 2010. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2012;6:e1814. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001814 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.FMOH. “National Five-Year Strategic Plan for Malaria Prevention and Control in Ethiopia” 2006-2010. Addis Ababa Ethiopia, FDRE Ministry of Health; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Holding PA, Kitsao-Wekulo PK. Describing the burden of malaria on child development: what should we be measuring and how should we be measuring it? Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2004;71(Suppl.2):71–79 12. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2004.71.2_suppl.0700071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mwageni et al. Household Wealth Ranking and Risk of Malaria Mortality in Rural Tanzania. Arush Tanzania, Bethesda, MO: Multilateral Initiative on Malaria; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ministry of Health. National Malaria Indicator Survey. Addis Ababa: Ministry of Health; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 8.WHO. World Malaria Report 2018. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ministry of Health. National Malaria Elimination Road Map. Ethiopia: Addis Ababa; Ministry of Health; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Adhanom T, Deressa W, Witten KH, Getachew A, Seboxa T. Epidemiology and Ecology of Health and Disease in Ethiopia. Addis Ababa: Shama Books; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Clark S, Berrang-Ford L, Lwasa S, et al.; IHACC Research Team. A longitudinal analysis of mosquito net ownership and use in an indigenous batwa population after a targeted distribution. PLoS One. 2016;11(5):e0154808. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0154808 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Theiss-Nyland K, Ejersa W, Karema C, et al. Operational challenges to continuous LLIN distribution: a qualitative rapid assessment in four countries. Malaria J. 2016;15:131. doi: 10.1186/s12936-016-1184-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Massebo F, Balkew M, Gebre-Michael T, Lindtiørn B. Entomologic inoculation rates of Anopheles arabiensis in southwestern Ethiopia. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2013;89:466–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mengistu H, Solomon G. Trend analysis of malaria prevalence in Arsi Negele health Centre, Southern Ethiopia. J Infect Dis Immunol. 2015;7(1):1–6. doi: 10.5897/JIDI2014.0147 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zgambo M, Mbakaya BC, Kalembo FW. Prevalence and factors associated with malaria parasitaemia in children under the age of five years in Malawi: a comparison study of the 2012 and 2014 Malaria Indicator Surveys (MISs). PLoS One. 2017;12(4):e0175537. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0175537 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mulugeta B. Prevalence of Malaria and Utilization of ITN in Children Under Five. Oromia Regional State, Ethiopia; 2013:46–47. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Qureshi I, Qureshi MA, Gudepu RK, Arlappa N. Prevalence of malaria infection among under five year tribal children residing in malaria endemic forest villages [version 1; referees: peerreviewdiscontinued]. F1000Research. 2014;3:286. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.5632.1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rogier C. Natural history of Plasmodium falciparum malaria and determining factors of the acquisition of antimalaria immunity in two endemic areas, Dielmo and Ndiop (Senegal). Bull Mém Académie R Médecine Belg. 2000;155:218–226. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schellenberg D, Menendez C, Kahigwa E, et al. African children with malaria in an area of intense Plasmodium falciparum transmission: features on admission to the hospital and risk factors for death. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1999;61:431–438. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1999.61.431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Danielle R. Prevalence and Risk Factors of Malaria in Children Under the Age of Five Years Old. Uganda: SACEMA Quarterly; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hasyim H, Dale P, Groneberg DA, Ulrich Kuch U, Müller R. Social determinants of malaria in an endemic area of Indonesia. Malar J. 2019;18:134. doi: 10.1186/s12936-019-2760-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Batega DW. Knowledge, Attitudes and Practices About Malaria Treatment and Prevention in Uganda: A Literature Review. Department of Sociology, Makerere University; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Okafor E, Emeka A, Amzat J. Problems of malaria menace and behavioral interventions for its management in sub-Saharan Africa. Hum Ecol. 2007;21::155–162. doi: 10.1080/09709274.2007.11905966 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhou S, Zhang S, Wang J, et al. Spatial correlation between malaria cases and water-bodies in Anopheles sinensis dominated areas of Huang-Huai plain, China. Parasit Vectors. 2012;5:106. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-5-106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Haryanti T, Maharani NE, Kristanto H. Effect of characteristics breeding site against density of larva anopheles in Tegalombo Sub District Pakistan Indonesia. Int J Appl Environ Sci. 2016;11(3):799–808. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vander, Konradsen F, Dijkstra DS, Amerasinghe PH, Amerasinghe FP. Risk factors for malaria: a micro epidemiological study in a village in Sri Lanka. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2011;92:265–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Delil RK, Dileba TK, Habtu YA, Gone TF, Leta TJ. Magnitude of Malaria and Factors among febrile cases in Low transmission Areas of Hadiya Zone, Ethiopia: A facility Based Cross Sectional Study. PLoS ONE; 2016:11(5):e0154277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shumbullo EL. Variation in Malaria Transmission in Southern Ethiopia, the Impact of Prevention Strategies and a Need for Targeted Intervention. Norway: University of Bergen; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 29.WHO. World Malaria Report. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Admasie A, Zemba A, Paulos W. Insecticide-treated nets utilization and associated factors among under-5 years old children in Mirab Abaya District, Gamo-Gofa Zone, Ethiopia. Front Public Health. 2018;6:7. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2018.00007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]