Abstract

Introduction

Significant gaps remain in the training of health professionals regarding the care of individuals who identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT). Although curricula have been developed at the undergraduate medical education level, few materials address the education of graduate medical trainees. The purpose of this curriculum was to develop case-based modules targeting internal medicine residents to address LGBT primary health care.

Methods

We designed and implemented a four-module, case-based, interactive curriculum at one university's internal medicine residency program. The modules contained facilitator and learner guides and addressed four main content areas: understanding gender and sexuality; performing a sensitive history and physical examination; health promotion and disease prevention; and mental health, violence, and reproductive health. Knowledge, perceived importance, and confidence were assessed before and after each module to assess curricular effectiveness and acceptability. General medicine faculty delivered these modules.

Results

Perceived importance of LGBT topics was high at baseline and remained high after the curricular intervention. Confidence significantly increased in many areas, including being able to provide resources to patients and to institute gender-affirming practices (p < .05). Knowledge improved significantly on almost all topics (p < .0001). Faculty felt the materials gave enough preparation to teach, and residents perceived that the faculty were knowledgeable.

Discussion

This resource provides an effective curriculum for training internal medicine residents to better understand and feel confident addressing LGBT primary health care needs. Despite limitations, this is an easily transferable curriculum that can be adapted in a variety of curricular settings.

Keywords: LGBTQ, Primary Care, Communication Skills, Competency-Based Medical Education, Cultural Competence, Gender Identity, Gender Issues in Medicine, Human Sexuality, Case-Based Learning, Diversity, Inclusion, Health Equity, Editor's Choice

Educational Objectives

By the completion of this curriculum, participants will be able to:

-

1.

Define sexual orientation, gender identity, gender expression, and minority stress.

-

2.

Identify at least three risk factors believed to underlie lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) health disparities and the sociocultural context of patients who identify as LGBT.

-

3.

Describe gender affirmation and gender-affirming care.

-

4.

Identify preventive care recommendations for men who have sex with men and women who have sex with women with respect to cancer screening, HIV, human papillomavirus, and hepatitis.

Introduction

Individuals identifying as lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) face difficulties in accessing and receiving health care, which may contribute to the well-established health disparities experienced by LGBT communities.1 Despite the nondiscrimination policies in the Affordable Care Act, LGBT individuals remain uninsured or underinsured compared to heterosexual or cisgender counterparts.2 Even when able to access health care, LGBT individuals may face challenges in finding clinicians who are able to provide welcoming and responsible care inclusive of sexual orientation, gender identity, and gender expression.3 This is particularly true for gender-nonconforming and transgender individuals, as skilled clinicians are often siloed into larger cities.3,4 Recognizing this, numerous national medical organizations—including the American College of Physicians and the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC)—have called for improved health professional training to care for individuals with diverse sexual orientations, gender identities, and gender expressions.5,6

Over the past decade, preliminary research has identified curricular gaps across training levels with respect to providing quality care for LGBT individuals. The largest national study to date found that a majority of undergraduate medical education (UME) institutions taught the definitions of sexual orientation and gender identity, as well as information related to HIV and sexually transmitted infections. However, most UME curricula failed to address topics that disproportionally affect LGBT communities, such as mental health, preventive care, gender-affirming care, and sociocultural factors influencing care.7 Even less research has been done at the graduate medical education (GME) level, which may arguably be the most important time to implement curricula as young physicians are learning the care practices that they ultimately will use during independent practice. Only one needs assessment has been performed at the GME level, in which it was found that 70% of emergency medicine residency programs do not have curricula specifically related to LGBT health.8

Despite foundational research clarifying the substantial amount of work required to provide adequate physician training in quality, responsible care for LGBT individuals, there remain few evidence-based curricular resources that measure outcomes in improvement in LGBT health care provision. At the UME level, available evidence-based curricula include standardized patient cases,9,10 small-group materials,11 and large-group didactic instruction.12 Given the paucity of curricular content available at the UME level, there is a dire need for materials that target GME specifically. One residency program recently developed an HIV primary care track for internal medicine residents specifically addressing HIV-related and LGBT care,13 demonstrating the feasibility and efficacy of material created specifically for GME.

Given that there is a need for content that specifically addresses the health concerns disproportionally affecting LGBT communities and that most of these concerns can be addressed by primary care, the purpose of this curriculum was to train internal medicine residents in the primary health care needs of LGBT patients. Furthermore, as faculty may have little prior knowledge in this area and resources for curricula may be limited,14 a secondary purpose was to develop an LGBT curriculum that could easily be taught by nonexpert faculty and easily transferred into a variety of curricular settings.

Methods

Setting

Internal medicine residents (N = 153) and faculty preceptors (N = 35) across three different ambulatory clinic sites at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center participated in the curriculum. The curriculum was implemented as part of the residency ambulatory program curriculum, utilizing a 45-minute, case-based preclinic conference format.

Curriculum Development and Implementation

The developers of the curriculum included trainees from internal medicine, medicine-pediatrics, and psychiatry residency programs; an associate program director for ambulatory training; and a content area expert on LGBT health. We based the learning objectives for each module (Appendix A) on the AAMC competency domains described in Implementing Curricular and Institutional Climate Changes to Improve Health Care for Individuals Who Are LGBT, Gender Nonconforming, or Born With DSD: A Resource for Medical Educators.6 Content to address these objectives was primarily derived from the Fenway Guide to Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Health,15 among other resources. We divided the objectives and content into four modules: (1) Understanding LGBT Issues (Appendix B); (2) Cultural Competencies, Performing a Sensitive History and Physical Exam (Appendix C); (3) Health Promotion and Disease Prevention (Appendix D); and (4) Mental Health, Violence, and Reproductive Health (Appendix E). Each module was composed of a faculty preceptor guide containing the teaching content and the resident learner guide. To ensure ease of teaching, and appropriateness of content and timing, we piloted the curriculum with a group of general internal medicine education fellows and incorporated their feedback into the final modules.

We developed the modules to be stand-alone modules that could be implemented flexibly based on curricular time available and the needs of an individual program. We presented the modules on an alternating monthly block schedule between residents' outpatient and inpatient blocks. In each given month, only half of the residents were assigned to their outpatient block, such that each resident received two modules per outpatient block. We provided the faculty preceptors with the preceptor guide in advance of the modules.

For each module, faculty reviewed the appropriate faculty guide prior to the session. Prior to the first session, the faculty asked the residents to complete the presurvey (Appendix F), which had previously been sent to them via email. The faculty then facilitated a discussion with a group of four to eight residents, using the case-based, guided questions (Appendices B–E). Following each session, the residents were asked to complete the appropriate postsurvey (see Appendix F). Each module was taught over a 45-minute time period prior to a clinical session. The curriculum implementation took a longitudinal approach, as the four modules were taught over the span of 4 months. Other topics in primary care being covered during that time were often interleaved with an individual session's module content. Implementation might be varied, and modules could be combined if necessary; however, we would suggest devoting 30–45 minutes of curricular time for each module.

Curriculum Assessment

All residents and faculty preceptors were given a presurvey (Appendices F and G, respectively) prior to initiation of the modules to assess their knowledge of LGBT primary care, attitudes toward the importance of LGBT health topics, and confidence in providing LGBT primary care. Survey questions were developed to address the learning objectives for each module. In addition, a postsurvey (Appendices F and G) asked participants to pick the two modules most impactful to their education and to answer questions about the acceptability of the curriculum, such as the amount of time dedicated to the topic. Faculty and residents were asked to assess whether the written materials were informative on a 5-point Likert-type scale (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree). Faculty were asked how prepared they felt, on a scale from 1 to 5, after reading the provided materials. The residents were also asked to judge the level of preparedness of the faculty. The survey was administered on REDCap, and participants were invited by email. Each participant was asked to create a unique identifier that was used to link presurveys to postsurveys.

Statistical Analysis

Summary statistics were calculated for the resident data and faculty data. The data were analyzed using StataSE v14.1 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas).

Results

Participation

One hundred residents and 29 faculty completed the presurvey (65% and 83% response rates, respectively). The majority of resident respondents identified as female (53%), the mean age of residents was 29.0 ± 5.3 years, and residents were almost evenly split across postgraduate year.16 The mean age of faculty was 42.5 ± 11.8 years.16 Of the individuals completing the presurvey, 57 residents (57%) and 14 faculty (48%) completed the first postsurvey. For the remaining three modules, resident response rates were 31%, 25%, and 27%, respectively, whereas faculty response rates were 17%, 10%, and 38%, respectively. Consistent with prior research,7 70% of residents and 90% of faculty reported less than 2 hours of prior exposure to formal LGBT curricular content. The results of the knowledge, importance, and confidence questions have been published previously.16 In summary, there was a statistically significant increase in overall knowledge from the presurvey to the postsurvey on multiple-choice questions. The residents and faculty rated the curricular topics to be equally important from pre- to postsurvey. They also reported that their confidence increased significantly in a majority of assessed LGBT health topics.16

Resident Outcomes

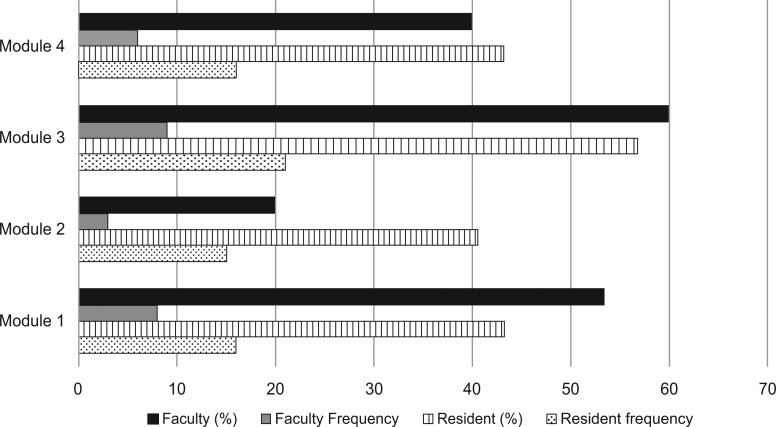

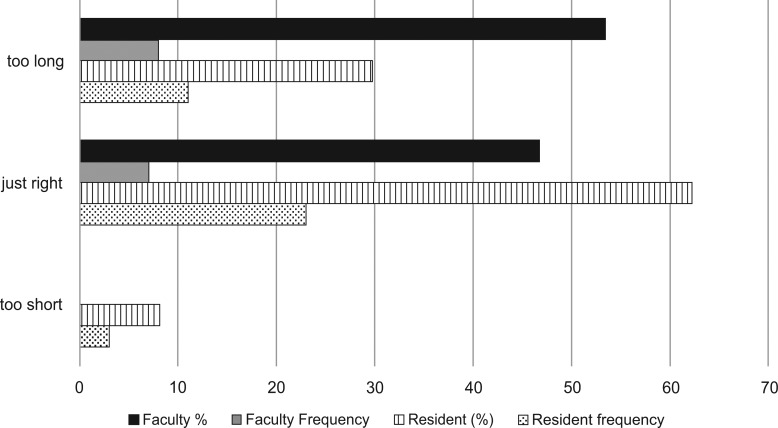

Residents felt that faculty were prepared and knowledgeable on the topic of LGBT health (M ± SD = 4.3 ± 0.1) and also agreed that the written materials were informative (M ± SD = 4.3 ± 0.1; Table). A slight majority of residents (57%) chose module 3 (Health Promotion and Disease Prevention) as the most impactful, followed by module 1 (Understanding LGBT Issues) and 4 (Mental Health, Violence, and Reproductive Health), both of which were chosen by slightly less than half of the residents (43%; Figure 1). Two-thirds of the residents (62%) felt that the curriculum length was appropriate (Figure 2). Finally, a majority of residents (84%) reported that the curriculum increased their conceptualization of barriers that patients who identify as LGBT face when obtaining health care.

Table. Acceptability of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Module Materialsa.

| Module 1 (N = 57) |

Module 2 (N = 47) |

Module 3 (N = 38) |

Module 4 (N = 37) |

Overall | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Respondents and Item | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD |

| Residents | ||||||||||

| The faculty were prepared and knowledgeable. | 4.3 | 0.7 | 4.5 | 0.6 | 4.3 | 0.8 | 4.2 | 0.7 | 4.3 | 0.1 |

| The written materials were informative. | 3.9 | 0.7 | 4.2 | 0.6 | 4.2 | 0.7 | 5.0 | 0.9 | 4.3 | 0.1 |

| Faculty | ||||||||||

| The faculty were prepared and knowledgeable. | 4.1 | 0.7 | 4.3 | 0.9 | 4.4 | 1.0 | 4.1 | 0.8 | 4.2 | 0.1 |

| The written materials were informative. | 4.4 | 0.5 | 4.3 | 0.5 | 4.5 | 0.5 | 4.3 | 0.5 | 4.4 | 0.0 |

Rated on a 5-point Likert-type scale (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree).

Figure 1.

Impactfulness of the modules. The four modules were module 1: Understanding LGBT Issues; module 2: Cultural Competencies, Performing a Sensitive History and Physical Exam; module 3: Health Promotion and Disease Prevention; and module 4: Mental Health, Violence, and Reproductive Health.

Figure 2.

Faculty and residents' response regarding the length of the lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender curriculum.

Faculty Outcomes

The faculty reported that they felt prepared and knowledgeable to teach the topic of LGBT health after reading the provided materials (M ± SD = 4.2 ± 0.1). They also considered written materials to be informative (M ± SD = 4.4 ± 0.0; Table). A majority of faculty (60%) chose module 3 (Health Promotion and Disease Prevention) as the most impactful, followed by module 1 (Understanding LGBT Issues), which was chosen by 53% of faculty (Figure 1). Around half of the faculty (47%) felt that the curriculum length was appropriate, whereas another half (53%) felt that the curriculum was too long (Figure 2). Almost all faculty (93%) reported that the curriculum increased their conceptualization of barriers that patients who identify as LGBT face when obtaining health care.

Discussion

This interactive, four-module, case-based curriculum focusing on LGBT topics in primary care for internal medicine residents fills a void in GME given the current paucity of LGBT health instructional materials targeted specifically to the GME level. Content was selected based upon the AAMC competencies in caring for individuals with diverse sexual orientations and gender identities; these competencies set a national standard for medical education curriculum integration identities.6,17 Although lack of faculty knowledge has been cited as an educational barrier, the curriculum was implemented by nonexpert faculty without additional preparation or research. Both residents and faculty felt that LGBT primary health care was important; however, consistent with prior research, residents and faculty had received little prior instruction on this topic.14 The curriculum resulted in improved knowledge and confidence among internal medicine residents and increased resident and faculty overall understanding of barriers faced by patients who identify as LGBT when interacting with the health care system.16 The curriculum could be implemented in the future for the benefit of other primary care residents (e.g., family medicine, adolescent medicine) and advanced practice providers.

Although a majority of faculty felt that the amount of time dedicated to this topic was excessive, a majority of residents felt that the amount of time was appropriate. This difference in opinion is somewhat surprising, since both residents and faculty believed that the topic was important to cover in the curriculum. Faculty may have felt that the time allotted was excessive because they were more attuned to the scarcity of curricular time for new innovations. However, residents lacking this education may have felt it was integral to their training due to growing cultural awareness and exposure to more diverse practice environments.

Considering that this was a single-site implementation, results may not be generalizable to other institutions with different curricular structures; however, the modular design of this curriculum permits users to tailor delivery according to local needs. A majority of both faculty and residents identified module 3, which addresses health promotion and disease prevention, as being the module that most impacted knowledge attainment. Importantly, only knowledge (i.e., performance at the “knows”/“knows how” level) and perception of confidence were assessed; future iterations should include assessment of performance and application of knowledge (i.e., the “shows”/“shows how” level), as well as patient-level or systems-level outcomes. Several other enhancements could be considered in the future. A flipped classroom model could be utilized to present the background information provided in module 1. Communication skills could be practiced via role-play or standardized patient encounters to provide formative feedback on students' history and physical examination skills (module 2). A didactic format could be retained for health promotion and disease prevention (module 3). Finally, module 4, which focuses on mental health, was rated least impactful by both residents and faculty; overall curriculum length could be further streamlined by condensing this information into the other modules.

Appendices

A. Mapped Educational Objectives.docx

B. Module 1 - Preceptor and Resident.docx

C. Module 2 - Preceptor and Resident.docx

D. Module 3 - Preceptor and Resident.docx

E. Module 4 - Preceptor and Resident.docx

F. Resident Pre-Postsurvey.docx

G. Preceptor Pre-Postsurvey.docx

All appendices are peer reviewed as integral parts of the Original Publication.

Disclosures

None to report.

Funding/Support

None to report.

Prior Presentations

Ufomata E, Eckstrand K, Hasley PB, Jeong K, Rubio D, Spagnoletti CL. Development and implementation of a curriculum for internal medicine residents in optimal primary care of patients who identify as lesbian, bisexual, gay or transgender [SGIM abstract 2701966]. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(2)(suppl):S667–S668.

Ufomata E, Eckstrand K, Hasley PB, Jeong K, Rubio D, Spagnoletti CL. Internal medicine residents and faculty implicit bias towards lesbian, bisexual, gay and transgender patients: a needs assessment [SGIM abstract 2704257]. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(2)(suppl):S231.

Ethical Approval

Reported as not applicable.

References

- 1.Institute of Medicine. The Health of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender People: Building a Foundation for Better Under-standing. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gonzales G, Henning-Smith C. The Affordable Care Act and health insurance coverage for lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults: analysis of the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. LGBT Health. 2017;4(1):62–67. https://doi.org/10.1089/lgbt.2016.0023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grant JM, Mottet LA, Tanis JE, Harrison J, Herman JL, Keisling M. Injustice at Every Turn: A Report of the National Transgender Discrimination Survey. Washington, DC: National Center for Transgender Equality and National Gay and Lesbian Task Force; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harrison J, Grant J, Herman JL. A gender not listed here: genderqueers, gender rebels, and OtherWise in the National Transgender Discrimination Survey. LGBTQ Policy J Harv Kennedy Sch. 2012;2(1):13–24. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Daniel H, Butkus R; for Health and Public Policy Committee of the American College of Physicians. Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender health disparities: executive summary of a policy position paper from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163(2):135–137. https://doi.org/10.7326/M14-2482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hollenbach AD, Eckstrand KL, Dreger A, eds. Implementing Curricular and Institutional Climate Changes to Improve Health Care for Individuals Who Are LGBT, Gender Nonconforming, or Born With DSD: A Resource for Medical Educators. Washington, DC: Association of American Medical Colleges; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Obedin-Maliver J, Goldsmith ES, Stewart L, et al.. Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender–related content in undergraduate medical education. JAMA. 2011;306(9):971–977. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2011.1255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moll J, Krieger P, Moreno‐Walton L, et al.. The prevalence of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender health education and training in emergency medicine residency programs: what do we know? Acad Emerg Med. 2014;21(5):608–611. https://doi.org/10.1111/acem.12368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eckstrand K, Lomis K, Rawn L. An LGBTI-inclusive sexual history taking standardized patient case. MedEdPORTAL. 2012;8:9218 https://doi.org/10.15766/mep_2374-8265.9218 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Underman K, Giffort D, Hyderi A, Hirshfield LE. Transgender health: a standardized patient case for advanced clerkship students. MedEdPORTAL. 2016;12:10518 https://doi.org/10.15766/mep_2374-8265.10518 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bakhai N, Shields R, Barone M, Sanders R, Fields E. An active learning module teaching advanced communication skills to care for sexual minority youth in clinical medical education. MedEdPORTAL. 2016;12:10449 https://doi.org/10.15766/mep_2374-8265.10449 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sullivan W, Eckstrand K, Rush C, Peebles K, Lomis K, Fleming A. An intervention for clinical medical students on LGBTI health. MedEdPORTAL. 2013;9:9349 https://doi.org/10.15766/mep_2374-8265.9349 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fessler DA, Huang GC, Potter J, Baker JJ, Libman H. Development and implementation of a novel HIV primary care track for internal medicine residents. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(3):350–354. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-016-3878-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tamas RL, Miller KH, Martin LJ, Greenberg RB. Addressing patient sexual orientation in the undergraduate medical education curriculum. Acad Psychiatry. 2010;34(5):342–345. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ap.34.5.342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Makadon HJ, Mayer KH, Potter J, Goldhammer H. Fenway Guide to Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Health. 2nd ed Philadelphia, PA: American College of Physicians; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ufomata E, Eckstrand KL, Hasley P, Jeong K, Rubio D, Spagnoletti C. Comprehensive internal medicine residency curriculum on primary care of patients who identify as LGBT. LGBT Health. 2018;5(6):375–380. https://doi.org/10.1089/lgbt.2017.0173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eckstrand KL, Potter J, Bayer CR, Englander R. Giving context to the Physician Competency Reference Set: adapting to the needs of diverse populations. Acad Med. 2016;91(7):930–935. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000001088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

A. Mapped Educational Objectives.docx

B. Module 1 - Preceptor and Resident.docx

C. Module 2 - Preceptor and Resident.docx

D. Module 3 - Preceptor and Resident.docx

E. Module 4 - Preceptor and Resident.docx

F. Resident Pre-Postsurvey.docx

G. Preceptor Pre-Postsurvey.docx

All appendices are peer reviewed as integral parts of the Original Publication.