Abstract

Although intimate partner violence (IPV) is highly prevalent among lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) young adults, only little is known regarding gender identity disparities in this population. Furthermore, virtually no research has examined IPV-related help-seeking patterns among LGBTQ young adults, including whether there are gender identity disparities in these rates and whether specific services are most likely to be used by LGBTQ young adults across IPV type. Participants were 354 LGBTQ young adults (ages: 18–25, 33.6% transgender and gender nonconforming [TGNC]) who experienced IPV victimization during their lifetime. TGNC young adults experienced more identity abuse victimization and reported 2.06 times the odds of seeking medical services, 2.15 times the odds of seeking support services, and 1.66 times the odds of seeking mental health services compared to cisgender sexual minority young adults. LGBTQ young adults with physical abuse victimization reported 2.63 times the odds of seeking mental health services, 2.93 times the odds of seeking medical care, and 2.40 times the odds of seeking support services compared to LGBTQ young adults without physical abuse victimization. Finally, LGBTQ young adults with identity abuse reported 2.08 times the odds of seeking mental health services and 2.58 times the odds of seeking support services compared to LGBTQ young adults without identity abuse. These findings provide a more complete understanding of gender identity as both risk and protective factors for IPV and IPV-related help-seeking. This study also provides implications for training providers, service availability, and resource allocation for LGBTQ young adults with IPV victimization.

Keywords: help-seeking, intimate partner violence, LGBTQ young adults, gender identity disparities

Intimate partner violence (IPV) victimization has a substantial impact on health care service use and cost (Rivara et al., 2007), with rates exceeding $4.1 billion in service delivery costs resulting from IPV victimization (Coker, Reeder, Fadden, & Smith, 2004). Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) young adults are at an increased risk for IPV victimization compared to cisgender heterosexual young adults (e.g., Dank, Lachman, Zweig, & Yahner, 2014; Reuter, Sharp, & Temple, 2015). One study found that lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth experience physical IPV victimization (43.0%), psychological IPV victimization (59.0%), cyber dating victimization (37.0%), and sexual coercion (23.0%) at greater rates than heterosexual youth, who reported rates of 29.0%, 46.0%, 26.0%, and 12.0%, respectively (Dank et al., 2014). Dank et al. (2014) also found that transgender youth were among those who reported the greatest IPV victimization rates; however, only 18 transgender youth were included in the sample (Dank et al., 2014).

In addition, prior studies primarily among cisgender heterosexual female young adults with IPV victimization found an increase in help-seeking behavior (e.g., inpatient hospitalization and mental health care) compared to those without IPV victimization (Amar & Gennaro, 2005; Coker et al., 2004). Nevertheless, virtually no studies have looked at IPV-related help-seeking patterns among LGBTQ young adults with IPV exposure and whether these patterns differed across various types of IPV exposure and gender identity. This study first seeks to assess patterns of IPV victimization among a large sample of an at-risk population, LGBTQ young adults. Then, gender identity disparities on physical, psychological, and identity abuse victimization between transgender and gender nonconforming (TGNC) and cisgender male and female young adults are examined. Next, IPV-related help-seeking patterns among LGBTQ young adults and potential gender identity disparities for each of these factors are assessed. Finally, this study examines whether IPV victimization forms are associated with specific IPV-related help-seeking patterns among LGBTQ young adults.

Adolescence and emerging adulthood represent developmental periods in which young adults begin to form their own individual identities, including developing one’s own sexual and gender identity and navigating dating relationships (Gillum & DiFulvio, 2012). In addition to developmental changes that all young adults experience (e.g., physical, psychological, and cognitive growth), for many LGBTQ young adults, developing a positive sexual or gender identity often occurs in the context of a cissexist (i.e., a system that results in disadvantages for TGNC individuals) and heterosexist environment (i.e., a system that privileges heterosexual individuals; Katz-Wise & Hyde, 2012). This overall context of stigma-related stress may have a direct impact on the ability of these at-risk young adults to develop healthy relationships, thus contributing to their increased risk of IPV victimization (Gillum & DiFulvio, 2012; Marrow, 2004).

IPV encompasses varying levels and forms of abuse, including physical, sexual, psychological, and emotional abuse within romantic relationships (Mulford & Giordano, 2008). While there is a dearth of literature on IPV victimization among LGBTQ young adults, among studies that do exist, findings suggest that LGBTQ young adults are at an increased risk for IPV victimization compared to cisgender heterosexual young adults (Dank et al., 2014; Edwards, Sylaska, & Neal, 2015; Mustanski, Andrews, Herrick, Stall, & Schnarrs, 2014; Reuter et al., 2015). Results from a recent study of more than 10,000 young adults in Massachusetts demonstrated that sexual minority female young adults who identified as lesbian (42.0%), bisexual (42.0%), or unsure (25.0%) reported IPV victimization more often than heterosexual female young adults (16.0%; Martin-Storey, 2015). In addition, gay (32.0%), bisexual (20.0%), and unsure (36.0%) identified male young adults reported IPV victimization more often than heterosexual male young adults (6.0%; Martin-Story, 2015). While it is important to compare prevalence rates of IPV victimization between sexual minority and cisgender young adults, the exclusion of TGNC young adults in IPV research is problematic, as it contributes to a traditional gender-based heterosexual model of IPV that ignores the specific needs of TGNC populations (Goldenberg, Jadwin-Cakmak, & Harper, 2018).

While TGNC young adults navigate similar developmental tasks (e.g., developing relationships and gaining independence) as sexual minority young adults, TGNC young adults may be particularly vulnerable to negotiating social and interpersonal challenges specific to their gender identity (Corliss, Belzer, Forbes, & Wilson, 2007; Neinstein, 2002). In fact, one longitudinal study found that TGNC young adults reported 3.42 times the odds of experiencing physical IPV victimization compared to cisgender sexual minority young adults (Whitton, Newcomb, Messinger, Byck, & Mustanski, 2016). Given these concerns, more research is needed to specifically assess for gender identity disparities among LGBTQ young adults’ experiences of other forms of IPV victimization that are salient in this community (e.g., identity-based victimization, described as follows) to develop appropriate prevention and intervention strategies across vulnerable subgroups of the LGBTQ community.

The nature of IPV victimization against LGBTQ individuals, and in particular, LGBTQ young adults, may be characteristically different from that used against cisgender, heterosexual individuals, given their unique experiences of intrapsychic, interpersonal, and structural forms of stigma that may be used as tactics of control within a relationship (Balsam & Szymanski, 2005; Scheer, Woulfe, & Goodman, 2019; Woulfe & Goodman, 2018). Building on this, LGBTQ IPV scholars have identified a unique form of IPV that may be specifically relevant for LGBTQ individuals, including young adults, namely, identity abuse (Guadalupe-Diaz & Anthony, 2017; Woulfe & Goodman, 2018). Identity abuse includes targeting discrediting, belittling, and devaluing a partner’s already-stigmatized LGBTQ identity and has four broad domains: (a) disclosing a partner’s LGBTQ status to others such as family members or an employer; (b) undermining, attacking, or denying a partner’s LGBTQ identity; (c) using slurs or derogatory language regarding a partner’s LGBTQ status; and, (d) isolating a partner from LGBTQ communities (Guadalupe-Diaz & Anthony, 2017; Woulfe & Goodman, 2018). There is limited literature to date, however, examining the rates of identity abuse victimization among LGBTQ young adults, because until recently, there has been no formal measure to assess for LGBTQ-specific identity abuse (Scheer et al., 2019; Woulfe & Goodman, 2018).

Many LGBTQ young adults may not turn to adults, peers, families, or communities for help when experiencing IPV due to fear of disapproval or rejection based on their sexual orientation or gender identity (Marrow, 2004), in addition to skeptical or dismissive attitudes after revealing their abusive experiences (Ismail, Berman, & Ward-Griffin, 2007; Weisz, Tolman, Callahan, Saunders, & Black, 2007). Instead, many may seek formal services, such as shelters, transitional living programs, and advocacy services (Durso & Gates, 2012). However, to our knowledge, there is virtually no research examining IPV-related help-seeking patterns among LGBTQ young adults with recent IPV victimization. Most research on help-seeking patterns in general has focused on identifying disparities between non-LGBTQ and LGBTQ individuals, overlooking potential differences among LGBTQ young adults (Macapagal, Bhatia, & Greene, 2016) or focused on sources of help without assessing the reasons for seeking help (Baams, De Luca, & Brownson, 2018). Importantly, research suggests that IPV-related help-seeking patterns may systematically differ among subgroups of LGBTQ young adults. Drawing on the assertions made by Marrow (2004), TGNC young adults with exposure to IPV may be especially vulnerable to barriers accessing affirming support from family, peers, and community and thus may turn to formal IPV-related services at greater rates than cisgender sexual minority young adults. Furthermore, virtually no research has examined whether specific IPV forms are associated with patterns of IPV-related help-seeking among LGBTQ young adults, for instance, identifying whether various types of IPV exposure are predictive of seeking certain services over others. These findings could contribute to a nuanced understanding of specific services that are sought by LGBTQ young adults with exposure to different forms of IPV victimization, which may have important and pragmatic implications for practitioners, service availability, and resource allocation.

The Present Study

This is among the first studies to examine IPV-related help-seeking patterns among a large sample of an at-risk population, LGBTQ young adults, as well as assess for potential gender identity disparities for each of these factors. Building on the aforementioned empirical evidence, this study hypothesized that TGNC young adults will report higher levels of IPV victimization and greater help-seeking of IPV-related services than cisgender sexual minority young adults. The final aim of this study was to examine whether IPV victimization forms are associated with specific IPV-related help-seeking patterns among LGBTQ young adults.

Method

Participants and Procedures

Participants were 354 LGBTQ young adults (Mage = 21.60, SD = 2.12, range = 18–25) who completed surveys that assessed for type and frequency of IPV victimization in the past year and across their lifetime and IPV-related help-seeking behavior during the past year. The full sample of participants identified as 25.7% bisexual, 20.9% queer, 17.5% lesbian, 14.1% gay, 12.1% pansexual, 5.7% “other non-heterosexual identity,” 4.0% asexual; and, 2.3% heterosexual. Most participants identified as cisgender women (50.8%) followed by TGNC (35.6%) and cisgender men (13.6%). Full demographic information is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Study Respondents.

| Variable | Full Sample M (SD)/Frequency | TGNC (n/%) | Cisgender Male (n/%) | Cisgender Female (n/%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age in years | 21.69 (2.12) | 21.75 (2.10) | 22.15 (2.11) | 21.53 (2.13) |

| Gender identity | ||||

| Cisgender woman | 50.8% | |||

| Cisgender man | 13.6% | |||

| TGNC | 35.6% | |||

| Sexual orientation identity | ||||

| Heterosexual | 2.3% | 6.3% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| Lesbian | 17.5% | 7.9% | 0.0% | 28.9% |

| Gay | 14.1% | 10.4% | 72.9% | 1.1% |

| Bisexual | 25.7% | 17.5% | 14.6% | 34.4% |

| Queer | 20.9% | 34.1% | 8.3% | 15.0% |

| Pansexual | 12.1% | 12.7% | 0.0% | 15.0% |

| Asexual | 4.0% | 7.1% | 0.0% | 2.8% |

| Other non-heterosexual identity | 5.7% | 10.3% | 4.2% | 2.8% |

| IPV victimization | ||||

| Psychological abuse | 54.5% | 65 (51.6%) | 27 (56.3%) | 101 (56.1) |

| Identity abuse | 30.5% | 47 (37.3%)*** | 12 (25.0%) | 49 (27.2%) |

| Physical abuse | 29.7% | 38 (30.2%) | 19 (39.6%) | 48 (26.7%) |

| IPV-related services | ||||

| Housing | 7 (1.9%) | 7 (5.5%)** | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Mental health services | 134 (37.8%) | 58 (46.0%)** | 10 (20.8%) | 66 (36.6%) |

| Medical care | 77 (21.7%) | 37 (29.3%)* | 6 (12.5%) | 34 (18.8%) |

| Support services | 63 (17.7%) | 32 (25.3%)* | 6 (12.5%) | 26 (14.4%) |

Note. Statistical significance for gender identity evaluated by MANOVA. TGNC = transgender and gender nonconforming; IPV = intimate partner violence; MANOVA = multivariate analyses of variance.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Participants were recruited from online groups, listservs, and forums (e.g., events, social media, and e-mail broadcasts distributed by LGBTQ- and IPV-related organizations). A secure online data collection tool was used to collect survey responses. All potential participants received instructions directing them to a link to the survey, where they consented to participate in the study. Inclusion criteria were young adults between the ages of 18 and 25, identifying as LGBTQ, and having experienced some form of IPV victimization across their lifetime. There were 1,344 people who began the survey; 354 (26.34%) met full inclusion criteria based on the screener that assessed for sexual orientation, gender identity, current age, and IPV victimization at some point in their lifetime: psychological abuse (14-item psychological maltreatment of women inventory [PMWI]; Tolman, 1999), physical abuse (6-item conflict tactics scale; Straus, Hamby, Boney-McCoy, & Sugarman, 1996), and identity abuse (7-item identity abuse scale; Woulfe & Goodman, 2018). Study protocols were approved by the host institution’s Institutional Review Board.

Measures

Demographics

Participants reported their current age and sexual orientation identity (response options included: heterosexual, lesbian, gay, bisexual, pansexual, queer, asexual, and “other”). Sexual orientation identity was assessed with the following question, “What is your current sexual orientation identity?” Gender identity was assessed with the following question, “What is your current gender identity?” Gender identity response options included: cisgender female, cisgender male, transgender or gender nonconforming, and “other.” Those who identified as heterosexual (n = 8) also identified as transgender or gender nonconforming and so were included in the analyses. For the multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA), gender identity was collapsed into the following categories: (a) cisgender male, (b) cisgender female, and (c) transgender, gender nonconforming, or “other” (TGNC). In order to fulfill the main aims of the article, gender identity was dummy coded as a dichotomous variable (0 = cisgender male or female; 1 = TGNC or “other”) for the correlation and logistic regression analyses.

IPV-related help-seeking

Participants reported whether they sought the following IPV-related services within the past year: housing (shelter and/or transitional living program), support services (hotline use, advocacy services, and/ or legal services), mental health services (support group and/or individual psychotherapy), and medical care (medication management and/or medical services). Response options for each type of health care service ranged from 0 (Never/not in the past year) to 4 (More than 10 times in the past year). For each of the analyses, IPV-related services (i.e., housing support, support services, mental health counseling, and medical care) were used as dichotomous variables (0 = No; 1 = Yes).

Identity abuse

The Identity Abuse Scale (IA Scale; Woulfe & Goodman, 2018) is a self-report measure that evaluated exposure to identity abuse in intimate partnerships during the past year. An example item includes, “The person questioned whether my sexual orientation or gender identity was real.” Response options ranged from 0 (did not occur) to 7 (occurred more than 20 times in the past year). The reliability and validity of the IA Scale has been established among a large sample of LGBTQ youth and adults ages 18–69 (α = .90; Scheer et al., 2019). The internal consistency estimate for IA during the past year among the current sample was α = .89. A mean score was created, and higher average scores represent greater exposure to IA during the past year.

Physical abuse

The Conflict Tactics Scale, short form (CTS-2; Straus et al., 1996) assessed physical abuse during the past year. The CTS-2 contains 20 items that assessed victimization in four domains: assault, injury, psychological aggression, and sexual coercion. An example item includes, “My partner slapped me.” The survey excluded the psychological aggression items and combined the four physical assault items and two sexual coercion items to form one physical abuse scale. Response options ranged from 0 (did not occur) to 7 (occurred more than 20 times in the past year). The reliability and validity of the CTS-2 has been explored among lesbian women (Matte & Lafontaine, 2011; α = .86; McKenry, Serovich, Mason, & Mosack, 2006; α = .92). The internal consistency estimate for CTS-2 during the past year among the current sample was α = .86. A mean score was created, and higher average scores represent greater exposure to physical abuse during the past year.

Psychological abuse

The PMWI (Tolman, 1999) measures past-year partner psychological aggression including dominance-isolation and emotional-verbal abuse. An example item includes, “My partner monitored my time and made me account for my whereabouts.” Participants responded to items by indicating the frequency of psychological abuse during the past year using a scale that ranged from 1 (did not occur) to 7 (occurred more than 20 times in the past year). The PMWI has been used among gay and lesbian individuals with adequate reliability (α = 90; McKenry et al., 2006). The internal consistency estimate for PMWI during the past year among the current sample was α = .95. A mean score was created, and higher average scores represent greater exposure to psychological abuse during the past year.

Data Analysis

Basic demographic characteristics of the sample were assessed. All analyses were completed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS), version 24. There was minimal missing data, ranging from 0.1% to 0.5% across the items (i.e., there was between 1 to 4 missing values for a specific item). Given that the study is exploratory, and the subject matter indicates that some missing data could be expected (Groza & Ryan, 2002), this study used the expectation maximization technique with inferences assumed. Statistical significance was determined at α = .05 level. Pearson’s r correlations were conducted to determine bivariate relationships among the abuse measures, frequency of IPV-related help-seeking within the past year, and age. Two MANOVAs were used to test for gender identity disparities between TGNC, cisgender sexual minority male young adults, and cisgender sexual minority female young adults on physical, psychological, and identity abuse victimization as well as on IPV-related help-seeking in the past year. Bonferroni post hoc comparisons were made when the follow-up MANOVAs and ANOVAs were significant.

Next, four binary logistic regression analyses (Model 1) were performed to determine potential gender identity disparities in IPV-related help-seeking behavior with housing, mental health services, medical care, and support services as separate outcome variables in each model with gender identity as the indicator, controlling for sexual orientation and age. Finally, we ran four multivariate binary logistic regression analyses (Model 2) to examine whether there were differences in IPV-related help-seeking behavior among LGBTQ young adults who experienced identity abuse, psychological abuse, and physical abuse victimization, with IPV-related services as separate outcome variables in each model with type of IPV victimization as the indicator variables, controlling for sexual orientation and age.

Results

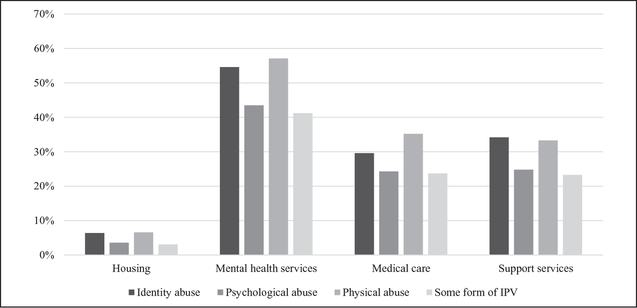

Based on inclusion criteria for the study, all LGBTQ young adults reported experiencing some type of IPV victimization over the course of their lifetime. Regarding past year IPV victimization exposure, most LGBTQ young adult participants reported experiencing psychological abuse victimization (54.5%), 30.5% reported experiencing identity abuse victimization, and 29.7% of LGBTQ young adults reported experiencing physical abuse victimization (see Table 1). Following any exposure to IPV victimization during the past year, 1.9% of LGBTQ young adults sought housing support, 37.8% sought mental health services, 21.7% sought medical care, and 17.7% sought support services during the past year. In addition, 37.6% of all LGBTQ young adults (regardless of whether they experienced IPV in the past year or across the lifetime) reported seeking some type of IPV-related health care service within the past year. LGBTQ young adults with identity and physical abuse exposure were more likely to seek housing support; those with psychological abuse and any IPV exposure were more likely to seek mental health services (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Proportion of IPV-related help-seeking behavior by IPV victimization type among LGBTQ young adults.

Note. IPV = intimate partner violence; LGBTQ = lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer.

Bivariate associations between study variables are reported in Table 2. Variables were associated in conceptually consistent directions. A MANOVA tested for gender identity disparities on physical, psychological, and identity abuse victimization between TGNC and cisgender male and female young adults. There was a significant omnibus effect, Wilks’ Λ = .93, F (6, 698.00) = 4.09, p < .001, η2p= .03. Bonferroni post hoc comparisons for variables wherein the follow-up ANOVAs were significant indicated that TGNC young adults (n = 126) experienced more identity abuse victimization than cisgender sexual minority male young adults (n = 48; p = .03) and cisgender sexual minority female young adults (n = 180; p < .001).

Table 2.

Bivariate Associations Between Study Variables.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Identity abuse | — | ||||||||

| 2. Psych abuse | .45*** | — | |||||||

| 3. Physical abuse | .34*** | .37*** | — | ||||||

| 4. Housing | .21*** | .13* | .22*** | — | |||||

| 5. Mental health | .23*** | .13* | .26*** | .18*** | — | ||||

| 6. Medical care | .13* | .07 | .23*** | .27*** | .59*** | — | |||

| 7. Support services | .28*** | .19*** | .26*** | .25*** | .47*** | .38*** | — | ||

| 8. Age | −. 16** | −.15** | −.13* | −.14** | −.08 | −.10 | −. 15** | — | |

| 9. Gender identity | .11* | −.04 | .01 | .19*** | .13* | .14** | .14** | .02 | — |

| M (SD) | 0.31 (0.46) | 1.55 (0.49) | 1.29 (0.46) | 0.02 (0.14) | 0.37 (0.48) | 0.21 (0.41) | 0.18 (0.38) | 21.69 (2.12) | 0.35 (0.47) |

Note. Psych abuse = psychological abuse; Housing = shelter and/or transitional living program; Mental health = individual psychotherapy and/or support group; Medical care = medication management and/or medical care; Support services = legal services, advocacy services, and/or hotline; Gender = gender identity (0 = cisgender sexual minority male and female; 1 = TGNC). TGNC = transgender and gender nonconforming.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

A second MANOVA tested for gender identity disparities across each of the IPV-related services that were sought following IPV exposure. There was a significant omnibus effect, Wilks’ Λ = .94, F (8, 696.00) = 2.87, p = .01, η2p = .03. Bonferroni post hoc comparisons for variables wherein the follow-up ANOVAs were significant indicated that TGNC young adults (n = 126) were more likely to seek housing support (p = .01) and support services (p = .04) than cisgender sexual minority female young adults (n = 180). In addition, TGNC young adults (n = 126) were more likely to seek mental health services (p = .01) and medical services (p = .04) than cisgender sexual minority male young adults (n = 48).

Binary logistic regression analyses adjusted for age and sexual orientation confirmed the MANOVA results, demonstrating that TGNC young adults reported 2.06 times the odds of seeking IPV-related medical care services, adjusted odds ratio (AOR) = 2.06, p = .01, 95% confidence interval (CI) = [1.21, 3.50], 1.66 times the odds of seeking IPV-related mental health services (AOR = 1.66, p = .03, 95% CI = [1.05, 2.62]), and 2.15 times the odds of seeking IPV-related support services compared to cisgender sexual minority male and female young adults (AOR = 2.15, p = .01, 95% CI = [1.21, 3.81]; see Table 3). We also explored specific services that were most likely to be used by LGBTQ young adults across IPV victimization type. Multivariate binary logistic regression analyses adjusted for age and sexual orientation demonstrated that LGBTQ young adults with exposure to physical abuse victimization in the past year reported 2.63 times the odds of seeking mental health services (AOR = 2.63, p < .001, 95% CI = [1.56, 4.50]), 2.93 times the odds of seeking medical care (AOR = 2.93, p < .001, 95% CI = [1.62, 5.29]), and 2.40 times the odds of seeking support services (AOR: 2.40, p = .01, 95% CI = [1.28, 4.52]) compared to LGBTQ young adults who did not experience physical abuse victimization in the past year. Finally, LGBTQ young adults with exposure to identity abuse victimization in the past year reported 2.08 times the odds of seeking mental health services (AOR = 2.08, p = .01, 95% CI = [1.21, 3.59]) and 2.58 times the odds of seeking support services (AOR = 2.58, p = .01, 95% CI = [1.34, 4.99]) compared to LGBTQ young adults who did not experience identity abuse victimization in the past year.

Table 3.

Binary Logistic Regression Analyses Assessing IPV-Related Help-Seeking Patterns (n = 354).

| Type of IPV-Related Service |

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Housing |

Mental Health Services |

Medical Care |

Support Services |

|||||||||

| AOR | AOR SE | AOR 95% CI | AOR | AOR SE | AOR 95% CI | AOR | AOR SE | AOR 95% CI | AOR | AOR SE | AOR 95% CI | |

| Model 1 | ||||||||||||

| Constant | 0.01 | 0.01 | 2.49 | 1.19 | 3.67 | 1.40 | 11.22 | 1.51 | ||||

| Gender identity comparing TGNC with cisgender (ref = cisgender) | 0.01 | 0.01 | [0.99, 1.00] | 1.66* | 0.23 | [1.05, 2.62] | 2.06** | 0.27 | [1.21, 3.50] | 2.15** | 0.29 | [1.21, 3.81] |

| Age | 0.52* | 0.26 | [0.31, 0.86] | 0.92 | 0.05 | [0.83, 1.02] | 0.88* | 0.05 | [0.78, 0.99] | 0.82** | 0.07 | [0.72, 0.94] |

| Sexual Orientation | 0.81 | 0.22 | [0.53, 1.24] | 1.06 | 0.07 | [0.93, 1.21] | 0.96 | 0.08 | [0.82, 1.12] | 1.02 | 0.09 | [0.86, 1.20] |

| Model 2 | ||||||||||||

| Constant | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.51 | 1.29 | 1.19 | 1.50 | 0.99 | 1.67 | ||||

| Identity abuse victimization (ref = no exposure) | 0.01 | 0.40 | [0, 1.01] | 2.08** | 0.28 | [1.21, 3.59] | 1.39 | 0.32 | [0.74, 2.62] | 2.58** | 0.34 | [1.34, 4.99] |

| Psychological abuse victimization (ref = no exposure) | 0.01 | 0.43 | [0, 1.01] | 0.90 | 0.27 | [0.53, 1.52] | 0.76 | 0.33 | [0.40, 1.44] | 1.32 | 0.37 | [0.64, 2.75] |

| Physical abuse victimization (ref = no exposure) | 0.01 | 0.39 | [0, 1.01] | 2.63*** | 0.27 | [ 1.56, 4.45] | 2.93*** | 0.30 | [1.62, 5.29] | 2.40** | 0.32 | [1.28, 4.52] |

| Age | 0.65 | 0.27 | [0.38, 1.09] | 0.97 | 0.06 | [0.87, 1.08] | 0.92 | 0.07 | [0.81, 1.04] | 0.88 | 0.07 | [0.77, 1.02] |

| Sexual orientation | 0.86 | 0.28 | [0.50, 1.48] | 1.09 | 0.07 | [0.96, 1.26] | 1.01 | 0.08 | [0.86, 1.18] | 1.07 | 0.09 | [0.89, 1.26] |

Note. IPV = intimate partner violence; Housing = shelter and/or transitional living program; Mental Health = mental health counseling and/or support group; Medical Care = medication management and/or medical services; Support Services = hotline, legal services, and/or advocacy services; AOR = adjusted odds ratio; 95% CI = 95% confidence interval; TGNC = transgender and gender nonconforming; ref = referent group.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Discussion

Given the pervasiveness of transphobic and homophobic stigma in the United States and the complexities of the lives of TGNC young adults in particular (Goldenberg et al., 2018), it is important to understand patterns of IPV victimization and IPV-related help-seeking among LGBTQ young adults as well as examine gender disparities within these patterns. This study is among the first, to our knowledge, to test for gender identity disparities in psychological, physical, and identity abuse IPV victimization, as well as in IPV-related help-seeking patterns across specific types of IPV-related services (e.g., housing and mental health services) among a large sample of at-risk LGBTQ young adults, all of whom had some form of IPV victimization exposure during their lifetime. In line with our hypotheses, our findings demonstrated that TGNC young adults experienced more identity abuse than cisgender sexual minority male and female young adults, and more physical abuse than cisgender female young adults. In addition, TGNC young adults were more likely to seek IPV-related medical care (e.g., medication management), support services (e.g., hotline use), and mental health services (e.g., psychotherapy) than cisgender sexual minority male and female young adults. Furthermore, LGBTQ young adults with exposure to physical abuse victimization in the past year were more likely to seek IPV-related mental health services, medical care, and support services than LGBTQ young adults who did not experience physical abuse victimization in the past year. Finally, LGBTQ young adults with exposure to identity abuse victimization in the past year were more likely to seek IPV-related mental health services and support services than LGBTQ young adults who did not experience identity abuse victimization in the past year.

Gender Identity Disparities in IPV Victimization

While all LGBTQ young adults in this sample reported experiencing some form of IPV over the course of their lifetime, a little more than half of the sample reported experiencing psychological abuse during the past year (54.5%), 29.7% reported experiencing physical abuse during the past year, and 30.5% reported experiencing identity-based partner victimization during the past year. These findings map on to and extend previous evidence demonstrating that LGBTQ individuals, particularly young people, are at an increased risk for IPV (Reuter et al., 2015). This study provided novel findings suggesting that TGNC young adults may experience greater rates of identity abuse victimization than cisgender sexual minority male and female young adults, and greater rates of physical abuse than cisgender sexual minority female young adults. These findings underscore the importance of developing effective interventions targeting TGNC young adults whose partners (who may also identify as LGBTQ) may use physical abuse as a tactic of control in the relationship and in addition, who may undermine or belittle their self-concept, as it relates to their gender identity development (Burgess, 1999; Levitt & Ippolito, 2014).

IPV-Related Help-Seeking Patterns and Gender Identity

While almost a third of LGBTQ young adults experienced IPV, less than half of these participants who experienced IPV sought IPV-related services. Consistent with prior studies, our findings indicate that the majority of LGBTQ young adults who are exposed to IPV do not seek IPV-related services following these violence experiences (Marrow, 2004). However, when looking at gender identity disparities in health care utilization patterns among LGBTQ young adults, TGNC young adults were more likely to seek housing support and support services related to IPV than cisgender sexual minority male and female young adults. In addition, TGNC young adults were more likely to seek mental health and medical services than cisgender sexual minority male young adults. Extending previous research, it is possible that TGNC young adults exposed to IPV may be especially vulnerable to barriers accessing affirming support from family, peers, and community and thus may turn to formal IPV-related services at greater rates than cisgender sexual minority young adults (Ismail et al., 2007; Marrow, 2004; Weisz et al., 2007). Taken together, it is critical for agencies and service providers to both increase their catchment of LGBTQ young adults in their service delivery and to become more aware of the unique experiences of TGNC young adults, given their likelihood of serving these populations in particular.

Associations Between IPV Forms and IPV-Related Help-Seeking Patterns

We found that LGBTQ young adults with exposure to physical abuse victimization were more likely to seek mental health services, medical care, and support services than LGBTQ young adults who did not experience physical abuse victimization. Moreover, LGBTQ young adults with exposure to identity abuse victimization were more likely to seek mental health and support services than LGBTQ young adults who did not experience identity abuse victimization. These noteworthy findings provide novel information of the IPV help-seeking patterns of LGBTQ young adults with various forms of IPV exposure that several pragmatic implications, including: (a) the importance of training providers across these types of services to screen for these specific abuse histories and (b) the need for programmatic shifts related to resource allocation and service availability for this population based on their unique IPV experiences.

Strengths and Limitations

There are several strengths of this study. This study is among the first to document that TGNC young adults may be more likely to seek formal IPV-related services than their cisgender heterosexual peers, a finding that provides important contributions to help tailor these services to meet the needs of TGNC young adults with IPV exposure. This study also is among the first to examine multiple forms of IPV victimization as predictors of IPV-related help-seeking patterns among LGBTQ young adults. Finally, this study is among the first to use a newly developed and validated measure of identity-based partner victimization—a form of abuse that is salient among LGBTQ individuals, including young adults (Scheer et al., 2019; Woulfe & Goodman, 2018).

While these findings advance research on gender identity disparities in IPV victimization and IPV-related help-seeking patterns among LGBTQ young adults with IPV victimization, there are some limitations to note. The data were non-experimental; thus, causality cannot be determined in the associations. Longitudinal research could provide stronger evidence for directionality of associations between IPV exposure and help-seeking behavior. In addition, we did not include “unsure” or “questioning” as response options for sexual orientation or gender identity, which could have limited the generalizability of some of our findings. In addition, we did not have a sufficient sample of gender nonconforming individuals to investigate comparisons between this group and transgender individuals. Given that gender nonconforming young adults with exposure to IPV are a highly marginalized and difficult to reach population, this reflects an ongoing challenge to address in future research. Although we used non-probability sampling methods in effort to target a difficult-to-reach population, our reliance on LGBTQ- and IPV-specific listservs, groups, and forums may have yielded a sample with unique attributes, posing challenges to the generalizability of the associations found for this sample. For instance, this sample may have reported greater IPV victimization and IPV-related help-seeking than the general population of LGBTQ IPV survivors by the very fact that participants were connected to LGBTQ- and IPV-specific online groups. Future studies should aim to use representative sampling approaches when studying IPV victimization and IPV-related help-seeking patterns among this population. Studies should also assess for general help-seeking patterns beyond past year exposure. Finally, this study did not assess for other important demographic characteristics that could influence IPV victimization and IPV-related help-seeking patterns (e.g., race and ethnicity, socioeconomic status, immigration status, education level; Chase, Treboux, & O’Leary, 2002; Tjaden & Thoennes, 2000). This limitation should be addressed in future research.

Implications for Research and Practice

This study provides several directions for future research. Future studies could benefit from longitudinal analyses that investigate how IPV victimization impacts IPV-related help-seeking patterns and satisfaction in services among LGBTQ young adults. Subsequent research should also assess for bi-directionality in abuse patterns (i.e., IPV perpetration) as well as other factors to better understand the context of IPV among this population. In addition, although this study assessed IPV victimization and IPV-related help-seeking patterns across gender identity, future research should assess whether the differences detected in this study might be associated with mental and physical health outcomes, including substance use and sexual risk behavior, two common outcomes reported among LGBTQ young adults with IPV victimization (Reuter, Newcomb, Whitton, & Mustanski, 2017).

Results from this study suggest that IPV victimization exposure is associated with several IPV-related services accessed among LGBTQ young adults (e.g., housing and mental health services). Interventions targeting IPV among LGBTQ young adults may benefit from adapting existing services and programs that are tailored to address specific needs of the LGBTQ community, and in particular, TGNC young adults. In addition, agencies and providers who serve LGBTQ young adults should be aware of LGBTQ IPV and increase their outreach efforts to this population as well as use formalized assessments of IPV for all LGBTQ young adults.

Conclusion

Studies of IPV patterns are critically important from a public health perspective (Johnson, Giordano, Manning, & Longmore, 2015). This study provided initial evidence that TGNC young adults report higher rates of IPV and IPV-related help-seeking compared to cisgender sexual minority young adults. Our study also indicated various forms of IPV victimization that are associated with IPV-related help-seeking patterns among LGBTQ young adults. Taken together, given the high prevalence of IPV and relatively low IPV-related help-seeking behavior among LGBTQ young adults, health care service providers and policy workers should be aware of risk factors associated with IPV and help-seeking patterns among LGBTQ young adults.

Acknowledgments

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This study was funded in part by the LGBT Dissertation Grant of the American Psychological Association and by the Boston College Lynch School of Education Doctoral Dissertation Fellowship in support of Jillian Scheer. The National Institute of Mental Health at the National Institutes of Health in support of Jillian Scheer supported manuscript preparation in part under grant number 5T32MH020031-20.

Author Biographies

Jillian R. Scheer, PhD, is a T32 postdoctoral fellow at the Center for Interdisciplinary Research on AIDS at the Yale School of Public Health. Dr. Scheer’s research broadly focuses on social and structural determinants of health disparities and violence exposure among sexual and gender minority youth and young adults.

Laura Baams, PhD, works as an assistant professor at the Pedagogy and Educational Sciences Department at the University of Groningen. Overall, Dr. Baam’s research addresses health disparities among LGBTQ youth and how these can be exacerbated or diminished by social environmental factors.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Amar AF, & Gennaro S (2005). Dating violence in college women: Associated physical injury, healthcare usage, and mental health symptoms. Nursing Research, 54, 235–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baams L, De Luca SM, & Brownson C (2018). Use of mental health services among college students by sexual orientation. LGBT Health, 5, 421–430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balsam KF, & Szymanski DM (2005). Relationship quality and domestic violence in women’s same-sex relationships: The role of minority stress. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 29, 258–269. [Google Scholar]

- Burgess JP (1999). Framing the homosexuality debate theologically: Lessons from the Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.). Review of Religious Research, 41, 262–274. [Google Scholar]

- Chase KA, Treboux D, & O’Leary KD (2002). Characteristics of high-risk adolescents’ dating violence. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 17, 33–49. [Google Scholar]

- Coker AL, Reeder CE, Fadden MK, & Smith PH (2004). Physical partner violence and Medicaid utilization and expenditures. Public Health Reports, 119, 557–567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corliss HL, Belzer M, Forbes C, & Wilson EC (2007). An evaluation of service utilization among male to female transgender youth: Qualitative study of a clinic-based sample. Journal of LGBT Health Research, 3, 49–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dank M, Lachman P, Zweig JM, & Yahner J (2014). Dating violence experiences of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youth. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 43, 846–857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durso LE, & Gates GJ (2012). Serving our youth: Findings from a national survey of service providers working with lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender youth who are homeless or at risk of becoming homeless. Los Angeles, CA: The Williams Institute, True Colors Fund, and the Palette Fund. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards KM, Sylaska KM, & Neal AM (2015). Intimate partner violence among sexual minority populations: A critical review of the literature and agenda for future research. Psychology of Violence, 5, 112–121. [Google Scholar]

- Gillum TL, & DiFulvio G (2012). “There’s so much at stake”: Sexual minority youth discuss dating violence. Violence Against Women, 18, 725–745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldenberg T, Jadwin-Cakmak L, & Harper GW (2018). Intimate partner violence among transgender youth: Associations with intrapersonal and structural factors. Violence and Gender, 5, 19–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groza V, & Ryan SD (2002). Pre-adoption stress and its association with child behavior in domestic special needs and international adoptions. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 27, 181–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guadalupe-Diaz XL, & Anthony AK (2017). Discrediting identity work: Understandings of intimate partner violence by transgender survivors. Deviant Behavior, 38, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Ismail F, Berman H, & Ward-Griffin C (2007). Dating violence and the health of young women: A feminist narrative study. Health Care for Women International, 28, 453–477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson WL, Giordano PC, Manning WD, & Longmore MA (2015). The age-IPV curve: Changes in the perpetration of intimate partner violence during adolescence and young adulthood. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 44, 708–726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz-Wise SL, & Hyde JS (2012). Victimization experiences of lesbian, gay, and bisexual individuals: A meta-analysis. Journal of Sex Research, 49, 142–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levitt HM, & Ippolito MR (2014). Being transgender: The experience of transgender identity development. Journal of Homosexuality, 61, 1727–1758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macapagal K, Bhatia R, & Greene GJ (2016). Differences in healthcare access, use, and experiences within a community sample of racially diverse lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and questioning emerging adults. LGBT Health, 3, 434–442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marrow DF (2004). Social work practice with gay, lesbian, bisexual and transgender adolescents. Families in Society, 85, 91–99. [Google Scholar]

- Martin-Storey A (2015). Prevalence of dating violence among sexual minority youth: Variation across gender, sexual minority identity and gender of sexual partners. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 44, 211–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matte M, & Lafontaine MF (2011). Validation of a measure of psychological aggression in same-sex couples: Descriptive data on perpetration and victimization and their association with physical violence. Journal of GLBT Family Studies, 7, 226–244. [Google Scholar]

- McKenry PC, Serovich JM, Mason TL, & Mosack K (2006). Perpetration of gay and lesbian partner violence: A disempowerment perspective. Journal of Family Violence, 21, 233–243. [Google Scholar]

- Mulford C, & Giordano PC (2008). Teen dating violence: A closer look at adolescent romantic relationships. National Institute of Justice Journal, 261, 31–40. [Google Scholar]

- Mustanski B, Andrews R, Herrick A, Stall R, & Schnarrs PW (2014). A syndemic of psychosocial health disparities and associations with risk for attempting suicide among young sexual minority men. American Journal of Public Health, 104, 287–294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neinstein LS (Ed.). (2002). Adolescent health care: A practical guide (4th ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. [Google Scholar]

- Reuter TR, Newcomb ME, Whitton SW, & Mustanski B (2017). Intimate partner violence victimization in LGBT young adults: Demographic differences and associations with health behaviors. Psychology of Violence, 7, 101–109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reuter TR, Sharp C, & Temple JR (2015). An exploratory study of teen dating violence in sexual minority young adults. Partner Abuse, 6, 8–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivara FP, Anderson ML, Fishman P, Bonomi AE, Reid RJ, Carrell D, & Thompson RS (2007). Healthcare utilization and costs for women with a history of intimate partner violence. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 32, 89–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheer JR, Woulfe JM, & Goodman LA (2019). Psychometric validation of the identity abuse scale among LGBTQ individuals. Journal of Community Psychology, 47, 371–384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA, Hamby SL, Boney-McCoy S, & Sugarman DB (1996). The revised Conflict Tactics Scales (CTS2): Development and preliminary psychometric data. Journal of Family Issues, 17, 283–316. [Google Scholar]

- Tjaden P, & Thoennes N (2000). Prevalence and consequences of male-to-female and female-to-male intimate partner violence as measured by the National Violence Against Women Survey. Violence Against Women, 6, 142–161. [Google Scholar]

- Tolman RM (1999). The validation of the Psychological Maltreatment of Women Inventory. Violence and Victims, 14, 25–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisz AN, Tolman RM, Callahan MR, Saunders DG, & Black BM (2007). Informal helpers’ responses when adolescents tell them about dating violence or romantic relationship problems. Journal of Adolescence, 30, 853–868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitton SW, Newcomb ME, Messinger AM, Byck G, & Mustanski B (2016). A longitudinal study of IPV victimization among sexual minority youth. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 34, 912–945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woulfe JM, & Goodman LA (2018). Identity abuse as a tactic of violence in LGBTQ communities: Initial validation of the identity abuse measure. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. Advance online publication. doi: 10.1177/0886260518760018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]