Abstract

Background

Although the number of older people serving community sentences (probation) after conviction for a criminal offence in England and Wales has increased rapidly since about 2006, this population has received little research attention.

Aim

To examine the mental health, substance use, and executive functioning of older probationers.

Methods

Thirty-two male probationers aged 50 years and older were recruited from probation services in the Thames Valley, England, and administered validated semistructured interviews for psychiatric disorders, symptom checklists for depression and substance use, cognitive impairment screens, and neuropsychological tests of executive functioning (examining verbal fluency and response inhibition).

Results

We found that older probationers presented with a high prevalence of mental health difficulties (overall caseness n = 22; 69%, 95% CI [53–85]) that exceed estimates in the older general population. Prevalences of depression (25%) or alcohol abuse or dependence (19%) were found to be high. In comparison with normative data, however, older probationers did not present with deficits in tested executive functioning.

Conclusions and implications for practice

Mental health and substance use problems were more prominent than cognitive deficits in this sample of older probationers. Further work should include older community controls to inform service planning and to determine how these mental health factors interact with offending.

Keywords: executive functioning, mental health, elderly, probation, substance abuse

1. Introduction

The number of people aged 50 years and older in the criminal justice system has grown rapidly in recent years. Between 2006 and 2016, the number of men aged 50 years and older serving community or suspended sentences doubled, and exceeded 10,500 by the end of 2016 (Ministry of Justice [MOJ], 2017). The growth of the older adult population does not fully explain this increase; the rise in reported sex crimes, increased use of custodial sentences, longer sentences and postrelease supervision periods are contributing factors (Codd & Bramhall, 2002; Howse, 2003; Office for National Statistics, 2015). Sexual offences are disproportionately represented in groups of older men who offend and account for 48–62% of offences in prison and probation samples (Codd & Bramhall, 2002; Curtice, Parker, Wismayer, & Tomison, 2003; Fazel, Hope, O'Donnell, & Jacoby, 2001; Hayes, Burns, Turnbull, & Shaw, 2012; Kennedy & Kitt, 2013).

Older people who offend have distinct criminological profiles and mental health needs, and it has been suggested that services for them cannot be based on information from younger offending groups or elderly people in the community (Fazel & Grann, 2002). Furthermore, the criminal justice system may not be the most appropriate service to meet their needs (Yorston & Taylor, 2006). It is important to have an understanding of older probationers in order to implement effective preventative and rehabilitation strategies (Brooker, Syson-Nibbs, Barrett, & Fox, 2009; Lewis, Fields, & Rainey, 2006). The chaotic lifestyles typically reported in many people who offend are thought to result in a health status 10 years older than someone in the general population (Cooney & Braggins, 2010; Omolade, 2014). Consequently, a cut-off of 50 years has been used to study old age in this group (Hayes et al., 2012).

There is a paucity of research on the mental health of older probationers. Probationers of all ages have more mental health needs than the general population, and comorbidity is common (Sirdifield, 2012). An epidemiological survey in one English county identified that 39% of probationers had a mental illness, 48% personality disorder, and 60% substance use problems (Brooker, Sirdifield, Blizard, Denney, & Pluck, 2012). There has been growing interest in the health and social needs of older people in prison, but it is important to look at other areas of the criminal justice pathway. Neuropsychological studies with older offending groups have primarily focused on generalised cognitive impairment and dementia, and less is known about distinct neuropsychological domains such as executive functioning (Fazel & Grann, 2002; Hayes et al., 2012). Executive functioning is an umbrella construct used to define a range of processes that enable individuals to perform purposive, goal-directed, and self-serving behaviours (Lezak, Howieson, Bigler, & Tranel, 2012). There is yet to be consensus on an operational definition for what processes constitute executive functions (Andrewes, 2015), but it is generally accepted that working memory, cognitive flexibility, planning, inhibition, initiation, and monitoring of action are types of executive function (Barkley, 2012).

Studies on executive function in older people who offend have yielded inconsistent findings. One assessed executive functioning in male prisoners aged above 59 years and compared the performance of those convicted of sex offences to those convicted of nonsex offences. No differences were found between these groups or when compared with data from older community controls (Fazel, O'Donnell, Hope, Gulati, & Jacoby, 2007). This has been recently confirmed in an Australian study (Rodriguez & Ellis, 2017), but other research reports contrasting findings (Combalbert et al., 2016).

The aim of this study is to examine the mental health, substance use, and executive functions in a sample of older male probationers, with focus on the executive functions of mental flexibility and response inhibition. Difficulties in these areas may particularly predispose people to criminal behaviour. Mental flexibility is the capacity to adapt and shift thinking in changing situations (Meltzer, 2014), so, reduced mental flexibility is expected to prevent people who offend from switching to more functional behaviours or finding new solutions to problems (Broomhall, 2005; Meijers, Harte, Jonker, & Meynen, 2015). Response inhibition is the process of suppressing responses that distract from, and interfere with, goal-directed behaviour (Mostofsky & Simmonds, 2008). It is a form of attentional control that allows one to resist temptations and impulsive action (Diamond, 2014).

We hypothesised that older probationers would have higher rates of psychiatric disorders and substance use than the general population, would obtain lower executive functioning scores than the normative average, and that these executive functioning scores would negatively correlate with age, drug, alcohol, and depression scores.

2. Method

Research approval was granted by the University of Oxford's Central University Research Ethics Committee (CUREC, ref: R47292/RE001) and the National Offender Management Service (NOMS, ref: 2016–290).

2.1. Sample

Thirty-two male probationers, aged 50 years and older, were recruited from various probation sites within Berkshire, Oxfordshire, and Buckinghamshire. Recruitment took place over 5 months. Probation services are provided by the National Probation Service (NPS) and the Community Resettlement Companies (CRCs). The NPS supervise probationers assessed as high risk and all sex offenders, whereas the CRCs supervise all other probationers.

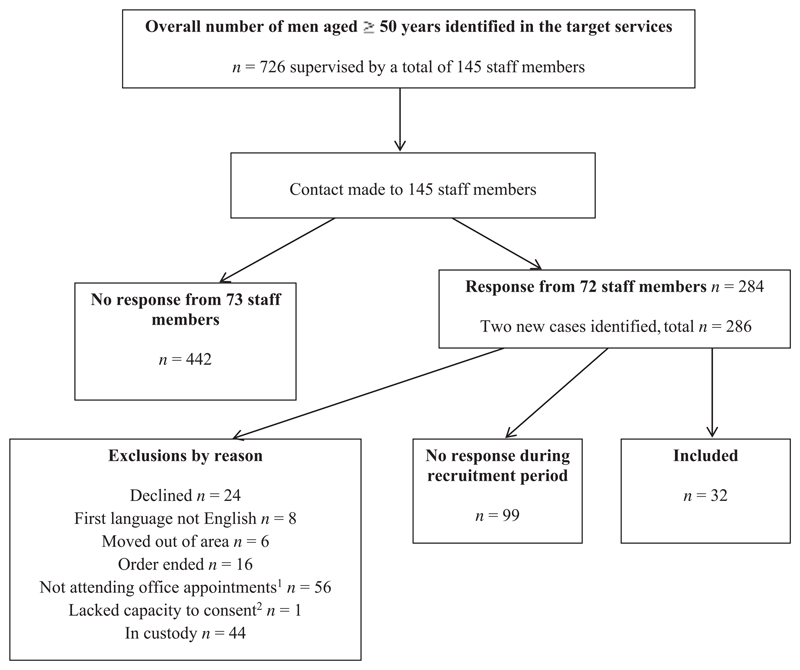

Inclusion criteria required participants to be currently supervised by a probation service within the community, aged at least 50 years old, and male. Due to the small number of older women on probation in the target sites, they were excluded to decrease demographic variability and to protect anonymity. Probationers were also excluded if their first language was not English, if they could not provide informed consent, or if there were concerns about risk of harm to the researcher (as indicated by probation staff). These wide inclusion and narrow exclusion criteria were decided in order to recruit as representative a sample of older probationers as possible. Figure 1 illustrates recruitment into the study.

Figure 1. Flowchart illustrating recruitment into the study within the five-month recruitment period.

2.2. Measures

The Test of Premorbid Functioning (TOPF; PsychCorp, 2009) estimates premorbid intellectual functioning and was used to provide descriptive information about the sample as a proxy measure of general intellectual abilities. Participants are required to read phonetically irregular words of increasing difficulty. Numbers of correct responses are scored, adjusted for education, and converted to an estimated full-scale intelligence quotient (FSIQ) score. The TOPF is considered a valid and reliable measure that correlates highly with the WAIS-IV FSIQ scores (PsychCorp, 2009; Watt, Gow, Norton, & Crowe, 2016).

The Verbal Fluency test: Delis–Kaplan Executive Function System (D–KEFS; Delis, Kaplan, & Kramer, 2001). The Letter Fluency and Category Fluency conditions from the D–KEFS verbal fluency test were used to assess mental flexibility. Participants are asked to produce as many words spontaneously as they can in 1 minute, following prespecified rules. The Verbal Fluency tests have been used in a range of studies with offender samples (Morgan & Lilienfeld, 2000), including older offenders (Combalbert et al., 2016; Fazel et al., 2007). The D–KEFS Letter and Category Fluency tests have acceptable validity and reliability (Delis et al., 2001).

The Color-word interference test (D–KEFS; Delis et al., 2001) was used as a measure of response inhibition. The inhibition condition on this test simulates the traditional Stroop task (and will be referred to as the Stroop test). Participants are shown a list of colour words naming colours but printed in different colour ink from the colour named and are asked to name the colour of the ink and not the read the word. The D–KEFS color-word interference test has acceptable validity and reliability (Delis et al., 2001) and has been used with offender samples (Broomhall, 2005; Hancock, Tapscott, & Hoaken, 2010).

The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI 5.0.0; Sheehan et al., 1998) is a brief diagnostic interview that assesses current and past symptoms of mental disorders, based on ICD-10 (World Health Organization, 1993) and DSM-IV (American Psychiatric Association, 2000) criteria. The participant is asked a range of screening questions for different psychiatric disorders and symptoms. It has good reliability and validity and has been used widely in research with offending groups, including probationers and elderly prisoners (Brooker et al., 2012; Combalbert et al., 2016; Lurigio et al., 2003; Rivlin, Hawton, Marzano, & Fazel, 2010).

The Geriatric Depression Scale–short form (GDS-15; Yesavage et al., 1983) measures current symptoms of depression. One point is scored for each of the depression criteria met (with a maximum score of 15). A score of 5 is used as a cut-off for likely depression. The GDS-15 is regarded as a good screening tool for major depression in older populations, with acceptable sensitivity and specificity (Almeida & Almeida, 1999). Using a cut-off score of 4 or 5, the GDS-15 has acceptable reliability and validity across different ages, genders, and health statuses (Nyunt, Fones, Niti, & Ng, 2009). The GDS-15 has been used in research with older offending groups (Murdoch, Morris, & Holmes, 2008).

The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT; Babor, Higgins-Biddle, Saunders, & Monteiro, 2001) is used to screen for risky or harmful alcohol use across 10 multiple-choice questions (scored from 0 to 4). It has a maximum score of 40, and scores of 8 and over indicate hazardous drinking. The AUDIT has satisfactory levels of validity and reliability (de Meneses-Gaya, Zuardi, Loureiro, & Crippa, 2009). It is a measure routinely used by the NPS and has been used in research with probationers (Brooker et al., 2012).

The Drug Abuse Screening Test–short form (DAST-10; Skinner, 1982) is a 10-item self-report-screening tool for assessing problematic drug use. Each indicator of drug abuse scores one point, yielding a maximum score of 10. A score of 3 or more indicates drug abuse or dependence. The DAST-10 has moderate to high levels of validity and reliability (Yudko, Lozhkina, & Fouts, 2007). It has been used in research with probationers (Brooker et al., 2012).

The Six-Item Cognitive Impairment Test (6CIT; Katzman et al., 1983) is a six-item brief screening tool assessing cognitive deficits across domains of memory, orientation, and calculation/attention. A higher score indicates more impairment, with a total possible score of 28 (all items incorrect). Scores of 0 to 7 are within the normal range and scores of 8 and over indicate difficulties warranting further assessment. Screening tools such as the 6CIT have been recommended for use with older offending groups (Curtice et al., 2003) but are not specifically validated for older probationers.

2.3. Procedure

A data analyst from probation services identified all male probationers aged 50 years and older together and the name of their probation officer. The researcher contacted each of these probation officers with the aim of recruiting all identified cases. The researcher provided the probation officers with a staff information letter and requested that they invite their client to participate with an invitation letter and information sheet. If the probationer were interested in participating in the project, the probation officer arranged for the researcher to meet him at the probation office as part of a routine appointment. Assessment sessions lasted, on average, 1 hour. Each participant was interviewed to obtain demographic and clinical information (age, ethnicity, educational and occupational history, current medication, and history of any psychiatric, cardiovascular, or neurological disorders including hospitalisation for a head injury) that could be used to inform neuropsychological test interpretation. The study measures were then administered in a standardised order. Every participant consented to the researcher accessing their probation record and after the assessments were completed details of participants' index offence, and risk scores were recorded. Risk scores were calculated using the Offender Group Reconviction Scale—Version 3 (OGRS [Taylor, 1999]). The OGRS offers predictions of risk of reoffending within one and 2 years using a logistic regression model incorporating criminal history and demographic factors.

2.4. Data analysis

Statistical analyses were completed using the SPSS (version 24.0) for Mac. All neuropsychological test scores were cross-checked by a psychology doctoral student independent of the authors. Each participant's raw scores on the neuropsychological tests were converted to an aged-scaled score using the test manual. One-sample t tests were used for the between-group analyses where these scaled scores were compared with the average-scaled score for the normative sample (Delis et al., 2001). There were two items of missing data, and statistical analyses were completed with these data omitted. Correlation analyses were used to assess the relationship between scores on these tests and depression, drug and alcohol scores and age as well as years of education, and TOPF scores. Normality and linearity assumptions were not met for all of these variables, therefore, nonparametric correlation methods were favoured. Descriptive statistics were used to present psychiatric and substance use scores.

3. Results

Table 1 provides descriptive information about the participants. Only one probationer had to be excluded from participation due to lack of capacity. According to the MINI, 69% of participants scored case positive for clinically meaningful symptoms, with a high proportion of these participants (73%) presenting with comorbidity (Table 2). The three most common current disorders were depression (25%), agoraphobia (19%), and alcohol abuse or dependence (19%).

Table 1. Characteristics of probationers aged 50 years and older who participated.

| Characteristic | Mean (SD) | Range | % (n) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 58.1 (6.9) | 50–75 | — |

| 50–59 years | — | — | 72 (23) |

| 60–69 years | — | — | 16 (5) |

| 70+ years | — | — | 13 (4) |

| Ethnicity | |||

| White British | — | — | 94 (30) |

| White Irish | — | — | 3 (1) |

| Afro-Caribbean | — | — | 3 (1) |

| Service | |||

| NPS | — | — | 84 (27) |

| CRCs | — | — | 16 (5) |

| Offence type | |||

| Violent | — | — | 16 (5) |

| Sexual | — | — | 66 (21) |

| Weapon carrying | — | — | 9 (3) |

| Other | — | — | 9 (3) |

| Type of sentence | |||

| Community order | — | — | 31 (10) |

| Suspended sentence | — | — | 34 (11) |

| Custody | — | — | 34 (11) |

| Length of sentence | |||

| Life | — | — | 9 (3) |

| Indeterminate (IPP) | — | — | 13 (4) |

| Over 10 years | — | — | 0 (0) |

| 5–10 years | — | — | 3 (1) |

| Up to 5 years | — | — | 59 (19) |

| Up to 1 year | — | — | 16 (5) |

| Prediction of reoffending (OGRS) | |||

| 1 year | 9% (12) | 1–59% | — |

| 2 years | 16% (16) | 3–75% | — |

| Years of educationa | 12.2 (1.8) | 8–17.5 | — |

| Estimated IQ (TOPF) | 97.0 (9.7) | 74–117 | — |

| Selfreported | |||

| Past head injury | — | — | 22 (7) |

| With loss of consciousness | — | — | 13 (4) |

| Cardiovascular or neurological conditionsb | — | — | 41 (13) |

| Mental health conditionsc | — | — | 47 (15) |

| Depression scores (GDS-15) | 4.0 (4.2) | 0–14 | — |

| Depression indicated (scores >5) | — | — | 31 (10) |

| Alcohol scores (AUDIT) | 7.2 (8.5) | 0–36 | - |

| Hazardous drinking indicated (scores ≥8) | — | — | 31 (10) |

| Drug use scores (DAST-10) | 0.2 (0.8) | 0–4 | — |

| Abuse/dependence indicated (scores ≥ 3) | — | — | 3 (1) |

| Cognitive impairment scores (6CIT) | 2.8 (3.0) | 0–12 | |

| Below cut-off indicating difficulties (scores ≤ 7) | — | — | 6 (2) |

Note: AUDIT: Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test; CRCs: Community Rehabilitation Companies; DAST-10: Drug Abuse Screening Test; GDS-15: Geriatric Depression Scale-Short Form; IPP: Imprisonment for Public Protection; NPS: National Probation Service; OGRS: Revised Offender Group Reconviction Scale; TOPF: Test of Premorbid Functioning; 6CIT: Six-Item Cognitive Impairment Test.

Ninety-seven percent completed at least secondary education, 91% had academic qualifications of at least a Certificate in Secondary Education, 9% were educated to a Higher National Diploma Level, and 9% to university level.

Of whole sample, 3% transient ischemic attack, 3% angina, 3% cardiac event, 3% pulmonary embolism, 3% cavernous sinus thrombosis, and 31% hypertension.

Of whole sample, 3% emotionally unstable personality disorder, 34% depression, 6% psychosis, 16% anxiety, 3% Asperger's syndrome, 3% post-traumatic stress disorder, 3% insomnia, 3% bipolar disorder, and 3% erotomania.

Table 2. Mental health diagnoses of 32 older probationers.

| % (n) | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|

| Current disorders (past month) | ||

| Depressive disorder | 25 (8) | 10–40 |

| Panic disorder | 0 (0) | — |

| Agoraphobia | 19 (6) | 5–32 |

| Social phobia | 13 (4) | 10–24 |

| Generalised anxiety disorder | 16 (5) | 3–28.2 |

| Post-traumatic stress disorder | 9 (3) | 0–20 |

| Obsessive compulsive disorder | 3 (1) | 0–9 |

| Alcohol abuse or dependence | 19 (6) | 5–32 |

| Substance abuse or dependence | 3 (1) | 0–9 |

| Psychotic disorder | 3 (1) | 0–9 |

| Eating disorder | 0 (0) | — |

| Past disorders (lifetime) | ||

| Panic disorder | 19 (6) | 5–32 |

| Psychotic disorder | 19 (6) | 5–32 |

| Antisocial personality disorder | 6 (2) | 0–15 |

| Other clinical symptoms | ||

| Suicidalitya | 52 (16) | 34–69 |

| Current symptoms only | 32 (10) | 5–32 |

| Past attempt only | 19 (6) | 5–33 |

| Hypomanic episode | ||

| Current symptoms | 0 (0) | — |

| Past symptoms | 0 (0) | — |

| Manic episode | 0 (0) | — |

| Current symptoms | 0 (0) | — |

| Past symptoms | 34 (11) | 18–51 |

| Caseness in any area | 69 (22) | 53–85 |

Overlap between symptoms present. Confidence intervals are for the percentage prevalence estimates. One participant did not complete the suicide screen on the MINI.

Note: CI: confidence interval; MINI: Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview.

Suicidality for 31 participants only.

3.1. Measures of executive functioning

On the Letter Fluency test, participants obtained higher scores (M = 12.3, SD = 3.4) than the normative sample (M = 10, SD = 3): t(31) = 3.9, P<0.001 (95% CI of mean difference: 1.1–3.6) with a medium effect size (d= 0.7). Scores on the Category Fluency test were also higher (M = 12.8, SD = 3.0) than the normative sample (M = 10, SD = 3), t(30) = 5.3, P<0.001 (95% CI of mean difference: 1.8–3.9) with a large effect size (d= 1.0). On the Stroop test, scores (M = 10.9, SD = 2.7) were higher than the normative sample (M = 10, SD= 3) but not significantly so, t(30) = 1.9, P = 0.07 (95% CI of mean difference: −0.1–1.9), with a small effect size (d= 0.3). None of the participants had difficulties on the naming and reading conditions. Using Spearman's Rank Order Correlation coefficient, the only significant relationships identified were between TOPF and Letter Fluency scores (rs= 0.43, P = 0.016) and TOPF and Stroop scores (rs = 0.49, P = 0.006).

4. Discussion

This study with 32 older probationers examined mental health, substance use, and executive functioning using validated semistructured interviews. Over two thirds of the sample presented with clinically relevant mental health symptoms, with high rates of comorbidity. Consistent with studies investigating mental health in older prisoners, two of the most prevalent conditions identified were current depression and alcohol abuse (Hayes et al., 2012). Rates of depression were more similar to prevalence rates observed in older prisoners (30% [Fazel et al., 2001]; 34% [Hayes et al., 2012]) than to older adults in the general population (U.K. survey estimates 6–14% [McManus, Meltzer, Brugha, Bebbington, & Jenkins, 2007]). Rates of alcohol abuse and dependence were comparable with rates in men aged 45 years and older in the general population (17–30% in a U.K. household survey [McManus et al., 2007]) and older prisoners (Hayes et al., 2012) but lower than rates identified in younger probationers (56% [Brooker et al., 2012]). Resettlement back into the community, experiences of loss, and the impact of a criminal conviction on relationships and occupations may predispose older probationers to mental health difficulties (Combalbert et al., 2016; Evans & Cubellis, 2015; Forsyth et al., 2014; Hayes, Burns, Turnbull, & Shaw, 2013). Only two participants were identified as having difficulties according to the cognitive impairment screen—a similar prevalence rate to that of prisoners aged 50 years and older (Hayes et al., 2012). Overall, there is no evidence that older probationers presented with gross cognitive impairment (as measured on the 6CIT cognitive screen). There was a lower rate of self-reported head injuries in the probationers (22%) than has been identified in imprisoned men in England (60%, Williams et al., 2010). The reasons for this are unclear and could reflect the small-sample size, different proportions of offender categories in this probation sample than in a general prison population, or cohort effects (as the sample was older).

In comparison with normative general population data, older probationers did not show impairment on measures of mental flexibility and response inhibition, despite the prevalence of conditions that might reduce performance, such as past head injuries. The finding that older probationers' verbal fluency scores were significantly above the normative average was unexpected. One explanation for this finding is based on the limitations of the normative comparison data used. The verbal fluency raw scores obtained in this probation population were more similar to those obtained by an older male English general population sample (Skirbekk, Stonawski, Bonsang, & Staudinger, 2013) and an Australian sample of men who had committed nonsexual offences (Rodriguez & Ellis, 2017). Significant correlations were not seen between executive functioning and older age, depression or substance use scores contrary to our hypothesis, and similar to another investigation (Combalbert et al., 2016). Such findings could reflect the complex interaction between mental health, substance use, and executive functioning. Executive dysfunction is not inevitable with the presence of a psychiatric condition or substance abuse (Testa & Pantelis, 2009). It remains unclear how the results from specific executive function tests relate to the complicated processes involved in offending behaviours (Massau et al., 2017). A range of other sociodemographic and biopsychosocial factors, and how they contribute to offending, were not addressed in the current study. In relation to the former, some older sex offenders may overall have less-recidivistic and criminogenic backgrounds. Given the larger proportion of men convicted for sex offences, the association of possible paraphilia and executive function in older probationers needs further research.

4.1. Strengths and limitations

This study contributes to the small number on older offending samples and, to our knowledge, is the first providing information on the mental health and neuropsychological functioning of older probationers. Participants were mostly White-British men in their 50s, an age representation similar to the national proportion of probationers over 50 years (with 76% aged between 50 and 69 years [Ministry of Justice, 2017]). A higher proportion of participants, however, were on probation for sex offences in this sample than older male probationers in the region (NPS cases: 78% vs. 59% [J. Rakestrow-Dickens, May 2017, Personal Communication]). Therefore, our findings may relate more to older men who commit sex offences than those who commit other crimes. Lack of capacity, however, given only one probationer in this state, had little impact on the overall findings.

The low-inclusion rate reflects the challenges of completing research within the probation service. It may have been possible to increase recruitment rates if participants were reimbursed for their time and/or if invitation were not dependent on probation officers volunteering their time to assist with recruitment. The findings should be interpreted with caution as the between-group comparisons for the Stroop test and the correlation analyses did not have sufficient power to detect an effect. Further, the absence of an individually recruited, carefully matched, comparison sample is a limitation. Although all of the measures used in this study have been previously used in neuropsychological and mental health research with offending samples, they have not been specifically validated for probationers and were selected to balance test reliability and validity with feasibility (considering the age group of the participants and the time available for interview).

4.2. Future research and service implications

We have shown that measuring older probationers' executive functioning and mental health is feasible. Future studies could address some of the limitations in the current investigation—by including a control group and measuring mental health needs. Validating and adapting current measurement tools for probation populations may also be required. Our study found that at least one psychiatric diagnosis was present in more than half of older probationers. The prevalence of mental health needs of older probationers deserves further exploration; particularly how these factors may interact with offending, risk, and recidivism (Chang, Lichtenstein, Långström, Larsson, & Fazel, 2016). Despite the important role mental health may have in protecting the public and reducing reoffending (Chang, Larsson, Lichenstein, & Fazel, 2015), there is currently no national strategy for mental health for probationers in England and Wales, and their access to mental health services is reported to be difficult (Brooker & Ramsbotham, 2014). There is a need for a national study of the mental health of probationers (Brooker et al., 2012) and clear mental health pathways informed by this. The latter could involve increasing staff awareness in all parts of the criminal justice system as well as better links between probation, mental health, and drug and alcohol services (Brooker, 2015). Future studies might also consider addressing other variables to better understand risk and protective factors for offending behaviour in older probationers. Understanding the characteristics and stability of criminogenic behaviour and qualitative accounts from older probationers on how they understand their offending and desistance would help to gain more evidence on this underresearched group.

5. Conclusions

This study provides preliminary information on older probationers' mental health, substance use, and neuropsychological functioning. There was a high prevalence of mental health difficulties and alcohol use among older probationers. When compared with normative data, older probationers did not present with deficits in executive functioning. Further research is required to clarify the extent to which the reported disorders represent unmet needs.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the probationers and staff members within Thames Valley probation for their participation. In addition, we are grateful to Ian Britton for his assistance with recruitment and Dr. David Murphy for his helpful guidance and comments on the study.

Funding Information

The research for this article was supported by Oxford Health NHS Foundation Trust (L.F) and Wellcome Trust Senior Research Fellowship (S.F. #202836/Z/16/Z).

Footnotes

ORCID

Lucy Fitton http://orcid.org/0000-0002-3663-967X

Declaration of Interest or Conflict of Interest

None.

References

- Almeida OP, Almeida SA. Short versions of the geriatric depression scale: A study of their validity for the diagnosis of a major depressive episode according to ICD-10 and DSM-V. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 1999;14:858–865. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1099-1166(199910)14:10<858::AID-GPS35>3.0.CO;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th ed. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Andrewes D. Neuropsychology: From theory to practice. 2nd ed. Hove, England: Psychology Press Ltd; 2015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Babor TF, Higgins-Biddle JC, Saunders JB, Monteiro MG. AUDIT: The alcohol use disorders identification test: Guidelines for use in primary health care. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Barkley RA. Executive functions: What they are, how they work, and why they evolved. New York, NY: The Guildford Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Brooker C. Healthcare and probation: The impact of government reforms. Probation Journal. 2015;62:1–5. doi: 10.1177/0264550515587971. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brooker C, Ramsbotham LD. Probation and mental health: Who cares? British Journal of General Practice. 2014;64:170–171. doi: 10.3399/bjgp14X677743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooker C, Sirdifield C, Blizard R, Denney D, Pluck G. Probation and mental illness. Journal of Forensic Psychiatry & Psychology. 2012;23:37–41. doi: 10.1080/14789949.2012.704640. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brooker C, Syson-Nibbs L, Barrett P, Fox C. Community managed offenders' access to healthcare services: Report of a pilot study. Probation Journal. 2009;56:45–59. doi: 10.1177/0264550509102401. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Broomhall L. Acquired sociopathy: A neuropsychological study of executive dysfunction in violent offenders. Psychiatry, Psychology and Law. 2005;12:367–387. doi: 10.1375/pplt.12.2.367. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chang Z, Larsson H, Lichenstein P, Fazel S. Psychiatric disorders and violent reoffending: A national cohort study of convicted prisoners in Sweden. Lancet Psychiatry. 2015;2:891–900. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(15)00234-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang Z, Lichtenstein P, Långström N, Larsson H, Fazel S. Association between prescription of major psychotropic medications and violent reoffending after prison release. JAMA. 2016;316:1798–1807. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.15380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Codd H, Bramhall G. Older offenders and probation: A challenge for the future. Probation Journal. 2002;49:27–34. doi: 10.1177/026455050204900105. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Combalbert N, Pennequin V, Ferrand C, Vandevyvère R, Armand M, Geffray B. Mental disorders and cognitive impairment in ageing offenders. Journal of Forensic Psychiatry & Psychology. 2016;27:853–866. doi: 10.1080/14789949.2016.1244277. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cooney F, Braggins J. Doing time: Good practice with older people in prison–The views of prison staff. London, England: Prison Reform Trust; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Curtice M, Parker J, Wismayer FS, Tomison A. The elderly offender: An 11-year survey of referrals to a regional forensic psychiatric service. Journal of Forensic Psychiatry & Psychology. 2003;14:253–265. doi: 10.1080/1478994031000077989. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- de Meneses-Gaya C, Zuardi AW, Loureiro SR, Crippa JAS. Alcohol use disorders identification test (AUDIT): An updated systematic review of psychometric properties. Psychology & Neuroscience. 2009;2:83–97. doi: 10.3922/j.psns.2009.1.12. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Delis DC, Kaplan E, Kramer JH. Delis-Kaplan executive system (D-KEFS) San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Diamond A. Executive functions. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2014;64:135–168. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-113011-143750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans DN, Cubellis MA. Coping with stigma: How registered sex offenders manage their public identities. American Journal of Criminal Justice. 2015;40:593–619. doi: 10.1007/s12103-014-9277-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fazel S, Grann M. Older criminals: A descriptive study of psychiatrically examined offenders in Sweden. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2002;17:907–913. doi: 10.1002/gps.715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fazel S, Hope T, O'Donnell I, Jacoby R. Hidden psychiatric morbidity in elderly prisoners. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2001;179:535–539. doi: 10.1192/bjp.179.6.535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fazel S, O'Donnell I, Hope T, Gulati G, Jacoby R. Frontal lobes and older sex offenders: A preliminary investigation. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2007;22:87–89. doi: 10.1002/gps.1648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forsyth K, Senior J, Stevenson C, O'Hara K, Hayes A, Challis D, Shaw J. “They just throw you out”: Release planning for older prisoners. Ageing and Society. 2014;35:2011–2025. doi: 10.1017/S0144686X14000774. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hancock M, Tapscott JL, Hoaken PNS. Role of executive dysfunction in predicting frequency and severity of violence. Aggressive Behavior. 2010;36:338–349. doi: 10.1002/ab.20353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AJ, Burns A, Turnbull P, Shaw JJ. The health and social needs of older male prisoners. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2012;27:1155–1162. doi: 10.1002/gps.3761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AJ, Burns A, Turnbull P, Shaw JJ. Social and custodial needs of older adults in prison. Age and Ageing. 2013;42:589–593. doi: 10.1093/ageing/aft066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howse K. Growing old in prison: A scoping study in older prisoners. London, England: Prison Reform Trust; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Katzman R, Brown T, Fuld P, Peck A, Schechter R, Schimmel H. Validation of a short orientation-memory-concentration test of cognitive impairment. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1983;140:734–739. doi: 10.1176/ajp.140.6.734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy S, Kitt I. Developing services for older offenders in Northumbria. 2013 Retrieved from http://www.tdi.org.uk/files/downloads/research_older%20offenders.pdf.

- Lewis CF, Fields C, Rainey E. A study of geriatric forensic evaluees: Who are the violent elderly? The Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law. 2006;34:324–332. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lezak MD, Howieson DB, Bigler ED, Tranel D. Neuropsychological assessment. 5th ed. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Lurigio AJ, Cho YI, Swartz JA, Johnson TP, Graf I, Pickup L. Standardized assessment of substance-related, other psychiatric, and comorbid disorders among probationers. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology. 2003;47:630–652. doi: 10.1177/0306624X03257710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massau C, Tenbergen G, Kärgel C, Weiß S, Gerwinn H, Pohl A, Schiffer B, et al. Executive functioning in pedophilia and child sexual offending. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society. 2017;23:1–11. doi: 10.1017/S1355617717000315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McManus S, Meltzer H, Brugha T, Bebbington P, Jenkins R. Adult psychiatric morbidity in England, 2007: Results of a household survey. London, England: The NHS Information Centre for health and social care; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Meijers J, Harte JM, Jonker FA, Meynen G. Prison brain? Executive dysfunction in prisoners. Frontiers in Psychology. 2015;6:2–7. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meltzer L. Teaching executive functioning processes: Promoting metacognition, strategy use, and effort. In: Goldstein S, Naglieri JA, editors. Handbook of Executive Functioning. New York, NY: Springer; 2014. pp. 445–494. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Justice. Offender management statistics quarterly: Probation: 2016. 2017 Retrieved from https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/offender-management-statistics-quarterly-october-to-december-2016.

- Morgan AB, Lilienfeld SO. A meta-analytic review of the relation between antisocial behavior and neuropsychological measures of executive function. Clinical Psychology Review. 2000;20:113–136. doi: 10.1016/S0272-7358(98)00096-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mostofsky S, Simmonds D. Response inhibition and response selection: Two sides of the same coin. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 2008;20:751–761. doi: 10.1162/jocn.2008.20500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murdoch N, Morris P, Holmes C. Depression in elderly life sentence prisoners. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2008;23:957–962. doi: 10.1002/gps.2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nyunt MSZ, Fones C, Niti M, Ng TP. Criterion-based validity and reliability of the geriatric depression screening scale (GDS-15) in a large validation sample of community-living Asian older adults. Aging & Mental Health. 2009;13:376–382. doi: 10.1080/13607860902861027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Office for National Statistics. Crime statistics, focus on violent crime and sexual offences: Chapter 1: Violent crime and sexual offences—Overview. 2015 Retrieved from http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/dcp171776_394474.pdf.

- Omolade S. The needs and characteristics of older prisoners. 2014 Retrieved from Ministry of Justice https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/needs-and-characteristics-of-older-prisoners-spcr-survey-results.

- PsychCorp. Test of premorbid functioning (TOPF): Administration and scoring manual. San Antoniou, TX: The Psychological Corporation; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Rivlin A, Hawton K, Marzano L, Fazel S. Psychiatric disorders in male prisoners who made near-lethal suicide attempts: Case-control study. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2010;197:313–319. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.110.077883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez M, Ellis A. The neuropsychological function of older first-time child exploitation material offenders: A pilot study. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology. 2017:1–17. doi: 10.1177/0306624X17703406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan H, Amorim P, Janavas J, Weiller E, Dunbar GC, et al. The mini-international neuropsychiatric interview (M.I.N.I.): The development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 1998;59(supplement 20):22–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sirdifield C. The prevalence of mental health disorders amongst offenders on probation: A literature review. Journal of Mental Health. 2012;21:485–498. doi: 10.3109/09638237.2012.664305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skinner HA. The drug abuse screening test. Addictive Behaviors. 1982;7:363–371. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(82)90005-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skirbekk V, Stonawski M, Bonsang E, Staudinger UM. The Flynn effect and population aging. Intelligence. 2013;41:169–177. doi: 10.1016/j.intell.2013.02.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor R. Predicting reconvictions for sexual and violent offences using the Revised Offender Group Reconviction Scale. Home Office research, development and statistics directorate research findings no. 104. London: Home Office; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Testa R, Pantelis C. The role of executive functions in psychiatric disorders. In: Wood SJ, Allen NB, Pantelis C, editors. The neuropsychology of mental illness. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press; 2009. pp. 117–137. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Watt S, Gow B, Norton K, Crowe SF. Investigating discrepancies between predicted and observed adult intelligence scale-version IV full-scale intelligence quotient scores in a non-clinical sample. Australian Psychologist. 2016;51:380–388. doi: 10.1111/ap.12239. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Williams WH, Mewse AJ, Tonks J, Mills S, Burgess CNW, Corday G. Traumatic brain injury in a prison population: Prevalence and risk for re-offending. Brian Injury. 2010;24:1184–1188. doi: 10.3109/02699052.2010.495697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. International statistical classification of diseases and related health problems 10th revision (ICD-10) 1993 Retrieved from http://apps.who.int/classifications/icd10/browse/2015/en.

- Yesavage JA, Brink TL, Rose TL, Lum O, Huang V, Adey MB, Leirer VO. Development and validation of a geriatric depression screening scale: A preliminary report. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 1983;17:37–49. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(82)90033-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yorston GA, Taylor PJ. Commentary: Older offenders—No place to go? Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law. 2006;34:333–337. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yudko E, Lozhkina O, Fouts A. A comprehensive review of the psychometric properties of the Drug Abuse Screening Test. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2007;32:189–198. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2006.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]