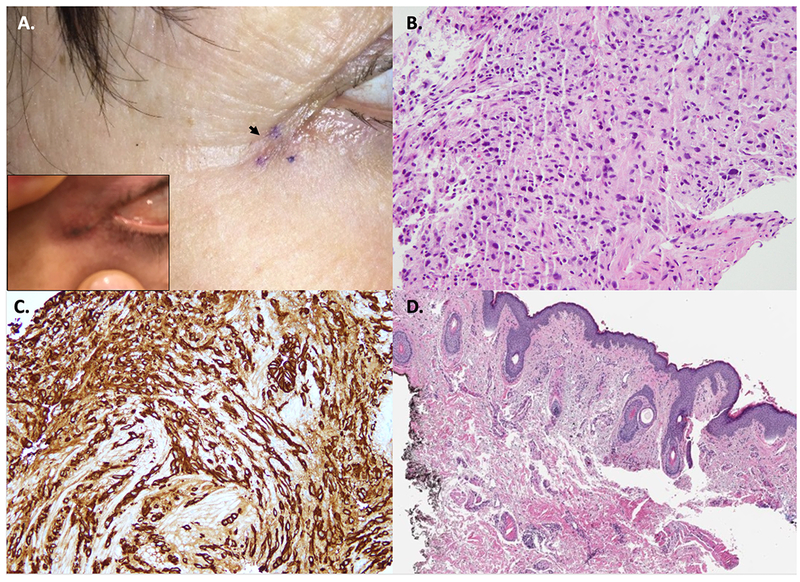

A 62-year-old, skin type III Female was referred for a recently diagnosed metastatic breast carcinoma to periocular skin. The patient had an infiltrating lobular breast carcinoma status post lumpectomy, ipsilateral axillary nodal dissection, radiotherapy, and tamoxifen treated 18 years ago. She presented with a 1-cm dark pigmented streak along right lateral canthus (Figure 1A, insert). Two punch biopsies revealed a poorly differentiated carcinoma (Figure 1B). The neoplastic cells showed AE1/AE3 (Figure 1C), GATA-3, and cytokeratin-7 immunoreactivity. There was also focal staining for estrogen receptor. A PET-CT showed no evidence of systemic metastasis. Due to her breast cancer history, a diagnosis of a metastatic lobular carcinoma was favored. Letrozole was initiated and the patient was referred to dermatology for excision of the solitary cutaneous metastasis.

Figure 1:

A. Clinical picture of the biopsy site along right lateral canthus showing a healing scar (black arrow). Photo taken by the patient showed a dark streak (insert). B. Tissue fragment of poorly differentiated carcinoma (H&E, 20X magnification). C. The tumor cells were immunoreactive for cytokeratins (AE1/AE3) (20X magnification). D. Excision of surrounding the biopsy site depicted in panel A showing a scar with no evidence of carcinoma (H&E, 4X magnification).

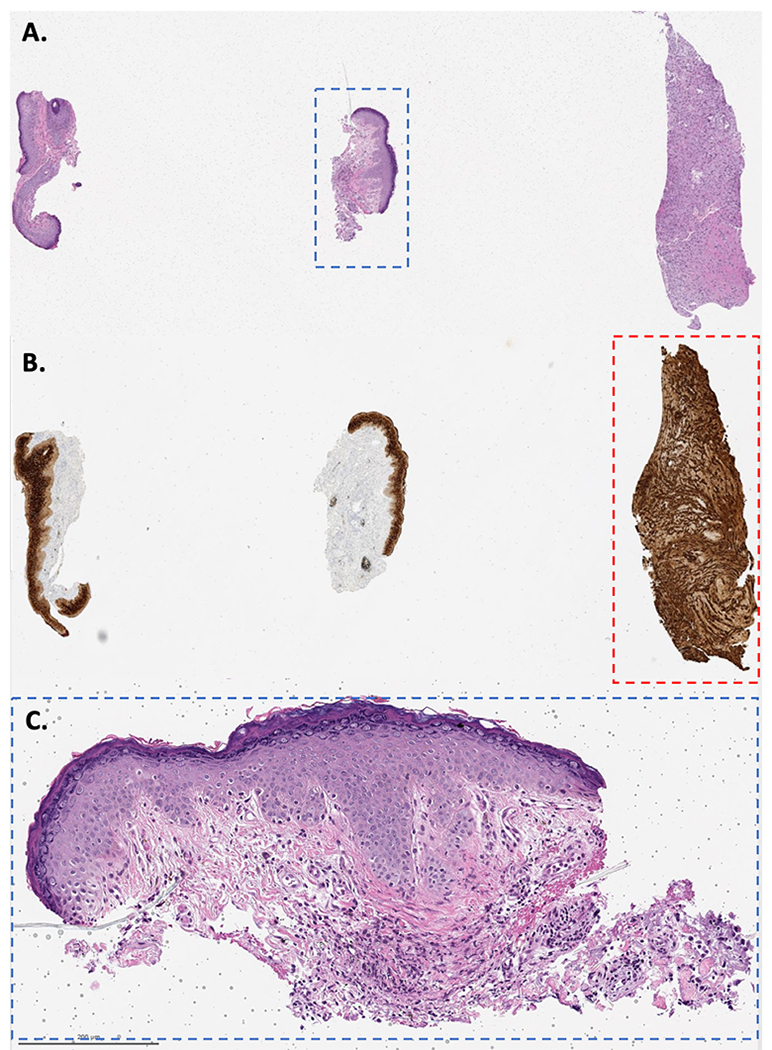

During patient examination in dermatology, no residual clinical lesion was visible/palpable. A conservative excision was performed for presumed cutaneous breast cancer metastasis. Histopathologic examination showed no carcinoma (Figure 1D). The case was discussed at tumor board given unusual presentation and lack of clinical-pathological correlation. Observation of a third tissue piece on the original biopsy slide (Figure 2A–B) by a dermatopathologist (that was not described in the gross-description), raised concern for tissue contamination. DNA-testing was performed to compare the initial breast cancer tissue from our patient to the ‘metastatic tissue’. No match was found, confirming tissue contamination. In fact, the test result revealed that the breast carcinoma tissue fragment (contaminating tissue) was from a male individual. Letrozole was withdrawn and patient was reassured. Final diagnosis was a foreign body granuloma (Figure 2C).

Figure 2:

A. The pathology slide of the original right lateral canthus biopsy contained 3 pieces of tissue (H&E); however, the biopsy-report gross description stated: “two minute skin punches biopsies each measuring 0.1 × 0.1 cm in diameter”. B. Immunoreactivity to AE1/AE3 highlighting the carcinoma (contaminating tissue, red dashed square). The third piece of tissue contained only tumor, no epidermis, measured at least 2 mm and was transected. C. The punch biopsies showed foreign body-type granulomas (blue dashed square, H&E, 10X magnification).

Contamination of pathology samples with exogenous malignant tissue is an uncommon phenomenon. When it occurs, however, it can lead to several adverse effects including death. In this case, an incorrect diagnosis of metastatic breast cancer to skin resulted in unnecessary workup, surgery, drug initiation, and cancer anxiety.

Patient and tissue misidentification are mostly secondary to human error and can occur at any step.1, 2 Tissue mismatch involving prostate or breast needle core biopsies have been documented1, 3 even in most regulated settings such as clinical trials. In the large REDUCE trial, evaluating dutasteride in prostate cancer, there was a biopsy rate and blood samples mismatch of 0.4% and 0.5% at year 2, respectively.2 Another study reported 0.43% surgical specimen identification errors.4 In a review of 272 claims, 13 cases involved specimen ‘mix-ups’; none involved a skin cancer. The most common were breast and prostate biopsies.3 In our patient, we can hypothesise that tissue contamination could have occurred from a prior case on the grossing table (unclean instruments) or tissue transposition during embedding (unclean waterbath).

Strategies to correctly identify suspected mismatched tissue include DNA profiling.2 In the REDUCE trial, the rate of misidentification was reduced from 0.4% to 0.02% after mandatory DNA profiling.2 Some authors have even proposed ‘DNA time-out’ to potentially eliminate identification errors among prostate biopsies; however, cost-effective analysis is lacking (~US$1,500/test).1, 2 Unfortunately, many commercial dermatopathology laboratories lack detailed gross description, which makes the detection of contamination errors very difficult.

Any major discordance between the clinical picture and the reported pathologic diagnosis begs for a possible explanation and reconciliation. Multidisciplinary tumor board discussions enable better clinical-pathological communication and help identify sources of errors.5

Founding source:

This research is funded in part by a grant from the National Cancer Institute / National Institutes of Health (P30-CA008748) made to the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: The authors have not conflict of interest to declare.

References:

- 1.Suba EJ, Pfeifer JD, Raab SS. Patient identification error among prostate needle core biopsy specimens--are we ready for a DNA time-out? J Urol. 2007; 178: 1245–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marberger M, McConnell JD, Fowler I, Andriole GL, Bostwick DG, Somerville MC, Rittmaster RS. Biopsy misidentification identified by DNA profiling in a large multicenter trial. J Clin Oncol. 2011; 29: 1744–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Troxel DB. Error in surgical pathology. Am J Surg Pathol. 2004; 28: 1092–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Makary MA, Epstein J, Pronovost PJ, Millman EA, Hartmann EC, Freischlag JA. Surgical specimen identification errors: a new measure of quality in surgical care. Surgery. 2007; 141: 450–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mori S, Navarrete-Dechent C, Petukhova TA, Lee EH, Rossi AM, Postow MA, et al. Tumor Board Conferences for Multidisciplinary Skin Cancer Management: A Survey of US Cancer Centers. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2018; 16: 1209–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]