Abstract

Papacarie Duo™ is clinically used and has proven effectiveness; however, it is necessary to improve its antimicrobial action. The combined treatment of Papacarie Duo™ with Urucum (Bixa Orellana) could create a potential tool for dental caries treatment; its extract obtained from the seeds’ pericarp contains a water-soluble primary pigment (cis-bixin) with smaller amounts of other carotenoids. The dicarboxylic acid salts of cis-norbixin and trans-norbixin occur in heated alkaline solutions. To analyze the absorption spectra and cytotoxicity (with human dermal fibroblasts) in different concentrations of Urucum, associated or not with Papacarie Duo™, we performed this in vitro study. The effects of pure Urucum, Papacarie Duo™, and PapaUrucum™ on the microstructure of collagen were also analyzed. The application of papain-based gel with Urucum did not present cytotoxicity, its exhibit UV absorption spectrum peak around 460 ± 20 nm. Also, it showed that the compound used did not alter the chemical structure of collagen. Consequently, this product could be used as a chemomechanical method to remove dentin caries as well as being a potential product for antimicrobial photodynamic therapy (aPDT) application.

Keywords: Cytotoxicity, Papain-based gel, Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy, Dentin

Introduction

Papacarie™ is a gel for the chemomechanical removal of carious lesions, composed of papain and chloramine [1–4]. Since 2003, when it was released, several clinical trials have been developed to explore its potential [5–9]. Positive results were found by examining procedure time [10], patient comfort [10, 11], costs [10], and pain [10, 12], and it is indicated as an excellent alternative for the treatment of carious lesions in children [4]. Also, commercially available, Papacarie Duo™, developed in 2011, has the same mechanism of action of the original version, Papacarie™, but with some improved properties, such as more extended durability, no need for refrigeration, and better viscosity [13]. Some clinical trials evaluated the potential of these products compared with the traditional method (low-speed bur), finding no significant differences between them [4, 13]. A study assessed the effectiveness of Papacarie Duo™ at inhibiting the growth of Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans and found that inhibition was lower when compared with other chemomechanical products for caries removal, which can be explained by the chloramine, present in the gel, injuring the microbial action in alkaline environments [14]. In contrast, it is still necessary to improve its antimicrobial activity.

Bixa Orellana (Fig. 1), a Brazilian plant that is also known as “Urucum” or “Annatto”, has seeds that have a natural colorant [15]. Bixa Orellana seeds contain carotenoids, mainly bixin and norbixin, the primary color pigments, which are essential pigments in cosmetic, pharmaceutical, and food industries [15]. The color of the pigment ranges from yellow to red. There are several studies which have observed the antimicrobial activity of the Urucum extract, commonly called Annatto extract [15–17]. This extracts are obtained in several ways, being commercially available in solutions or suspensions of the pigment in oil or in water alkaline solution [14] (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Chemical structures of Bixa Orellana (Bixin) and papain

Fig. 2.

Shows the peak positions in the UV-Vis and absorption spectra of the annatto solution extracted from the fruit of the Bixa Orellana (pure Urucum), papain gel (Papacarie Duo), and Papain-gel with Urucum (PapaUrucum)

A change in Papacarie™ composition was suggested to improve its properties and applicability so that it can be used as an agent for removing the necrotic dentin tissue and also acts as an antimicrobial agent. This change was performed by adding Urucum (Bixa Orellana extract) pigment to be used as a photosensitizer when associated with a blue light source, increasing its antimicrobial activity, and could be used for antimicrobial photodynamic therapy (aPDT). This produced a new product formulation called Papacarie Duo™, based on the combination of Urucum extract and the papain gel.

The use of Bixa Orellana (bixin) and papain as aPDT is a promising treatment to inactivate microorganisms because it employs a non-toxic red dye that can be activated by blue light. When the photosensitizer is light activated, it induces the formation of reactive oxygen species (ROS). This reactive oxygen species can kill bacteria present in the infected dentin of carious lesions. Based on the minimally invasive approach to preserve dental tissue, some recent studies [18–21] demonstrated that aPDT is a promising adjunctive therapy to the treatment of caries lesions.

ROS has two parallel generation pathways: type I reaction, which involves electron transfer to oxygen primarily forming superoxide and finally hydroxyl radicals, and type 2 reactions, which comprises energy transfer to ground state triplet oxygen and production of singlet oxygen [18].

The present “in vitro” study had the aim to investigate the absorption spectra, the human dermal fibroblast cytotoxicity, and the microstructure of collagen using pure Urucum, Papacarie Duo™, and PapaUrucum™, to observe if it is feasible for clinical use.

Materials and methods

Experimental design

To analyze the absorption spectra, cytotoxicity (with human dermal fibroblasts) and alteration effects on the collagen microstructure after application of pure Urucum pigment, Papacarie Duo™, and PapaUrucum™, we performed this in vitro study.

For the first analysis, the absorbance of different samples following the concentrations of Urucum (40 μM), Urucum associated with Papacarie™ (PapaUrucum™ 40 μM), and (Papacarie Duo™, 40 μM) was evaluated by the ultraviolet-visible (UV-Vis) absorption spectra of the annatto solution extracted from the fruit of the Bixa Orellana (pure Urucum), papain gel (Papacarie Duo™), and papain-gel with Urucum (PapaUrucum™), the peak positions in the UV-Vis.

The second analysis was the evaluation of the effects of pure Urucum, Papacarie Duo™, and PapaUrucum™ on the microstructure of collagen. Twenty discs of bioabsorbable collagen membranes were randomly distributed into four experimental groups (n = 5) to be treated with the following substances: G1col (Milli-Q water), G2col (Papacarie Duo™), G3col (Urucum), G4col (PapaUrucum™). After treatments, the composition and integrity of the triple helix of the collagen were evaluated by Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR).

Statistical analysis was performed individually for the second and third experimental phases. For that purpose, each treatment was considered a separate block, and the experimental unit was the membrane disks for the second experimental phase, and the dentin slabs for the third experimental phase. The significance level considered was 5% (α = 0.05).

Absorption spectra analysis of Papacarie Duo™, PapaUrucum™, and pure Urucum

The dilution of pure Urucum was 3 ml of H2O added to 1.88 g of Urucum total concentration of 10%. The stock solutions were prepared in 100 μM and then diluted in different concentrations in 1 ml of H2O.

The acquisition of the UV absorption spectra was made by a spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific Evolution 300 UV-Vis, ratio 450/550). The purity of the Urucum samples in the presence of protein dye could be determined using the ratio between 200 and 700 nm of the UV absorptions of the sample.

Cytotoxicity study

We used human dermal fibroblast cell line (ATCC PCS-201-012TM). Five thousand cells were cultured and then incubated for 24 h at 37 °C with a 0.5% CO2 atmosphere on a 1.5 high-performance cover glass (0.170± 0.005 mm) coated with poly-D-lysine. Subsequently, papain-based gel with Urucum (PapaUrucum™) was added in different concentrations of 20–40 μM for 20 min. After that, the cells were washed 3× with PBS, and the medium (DMEM) replaced before incubation for 1 h. Human primary dermal fibroblasts (ATCC PCS-201-012™) were used and cultured in DMEM in 96-well plates. Five thousand cells were cultured and then incubated for 24 h at 37 °C with a 0.5% CO2 atmosphere on a 1.5 high-performance cover glass (0.170± 0.005 mm) coated with poly-D-lysine. Subsequently, PapaUrucum™ was added in different concentrations of 20–40%. After that, the cells were washed 3× with PBS, and the medium (DMEM) replaced before incubation for 1 h. Cytotoxicity was verified through cell viability immediately after and 3, 6, 9, 24, 48, and 72 h later. For the MTT assay, the cells were incubated for 4 h with 10 μL reagent (10% dilution of the reagent added to 100 μL of DMEM medium) and reducing environment within viable cells converts the MTT reagent to an intensely red fluorescent dye (excitation 560 nm and emission 590 nm).

Confocal fluorescence microscopy for subcellular localization

Human dermal fibroblasts (ATCC PCS-201-012™, 5000 cells) were cultured for 24 h on 1.5 high-performance cover glasses (0.170± 0.005 mm) coated with poly-D-lysine. After 24 h, PapaUrucum™ with a concentration of 20 μM was added for 20 min during light interval. After that, the cells were washed 3× with PBS, and the medium (DMEM) was replaced and incubated for 1 h. Fluorescent probes stained the cellular organelles. MitoTracker® Green was used to stain mitochondria (excitation 490 nm and emission 516 nm, 50 nM) (Fig. 3), LysoTracker® Red to stain lysosomes (excitation 577 nm and emission 590 nm, 75 nM), and Hoechst trihydrochloride trihydrate to stain nuclei (excitation 350 nm, emission 510 nm, 4 μg/ml, 40 μL). All probes were incubated for 45 min, after that, the medium was removed, and 100 μL of Live Cell Imaging Solution (Molecular Probes®) was added to provide better clarity and reduce signal-to-noise ratio and cell viability. Fluorescence images were acquired with an Olympus BX51 microscope (zm1-3 OIB image immersion) with an augmentation of × 20, visualized using a confocal microscope.

Fig. 3.

Cytotoxicity—MTT assay with pure Urucum and PapaUrucum

Analysis of the effects of pure Urucum, Papacarie Duo™, and PapaUrucum™ on collagen microstructure

For this analysis, we used 20 discs of sponges of type-I collagen from bovine Achilles deep tendon of bioabsorbable membranes (Technodry Liofilizados Médicos, MG, Brazil), composed of type-I collagen from bovine Achilles deep tendon. The samples were 5 × 2 mm respectively in diameter and thickness. After sample preparation, the disks were randomly distributed among four experimental groups (n = 5), as shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Description of the experimental groups used for the second phase of this study

| Group | Treatment | Description |

|---|---|---|

| G1col | Glow Washing with Milli-Q water (negative control group) | Samples washed with Milli-Q water for 30s and dried with absorbing paper |

| G2col | PapacarieDuo™ 2 min | Application time: 2 min; samples were washed in Milli-Q water for 30s and dried with absorbing paper |

| G3col | Pure Urucum (Bixa orellana) | Urucum (F&A; São Paulo); application time: 2min; samples washed in Milli-Q water for 30s and dried with absorbing paper |

| G4col | Papain gel with Urucum | Application time: 2min; samples washed in Milli-Q water for 30s and dried with absorbing paper |

In the G1 group (negative control), each sample was washed with Milli-Q water (Millipore, Bedford, MA, USA) for 30 s and, after that, dried with absorbing paper (Whatman no. 6, Whatman International, England). In the other groups (Group 2, Group 3, and Group 4), each membrane was fully covered with gel Papacarie Duo™ (F&A, São Paulo, Brazil), pure Urucum (Bixa Orellana), and PapaUrucum™ (papain-based gel with Bixa Orellana), respectively, for 2 min; after this time, the samples were abundantly washed with Milli-Q water for 30 s and dried with absorbing paper (Whatman no. 6, Whatman International, England). After that, collagen samples were abundantly washed with Milli-Q water for 30 s and dried with absorbing paper (Whatman no. 6, Whatman International, England). All treatments were performed just before the analysis of each sample by FTIR to avoid dehydration or excessive water incorporation into samples. If the FTIR analyses were conducted so late, excessive dehydration can compromise the spectra obtained.

We used the attenuated total reflectance technique (using a diamond crystal coupled to the spectrometer, as previously described [18]) of Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (ATR-FTIR, Varian 610, Agilent Technologies, CA, USA) for analyzing the collagen composition. Each sample had their ATR-FTIR spectra obtained in the range of 4000 to 500 cm−1 (resolution of 4.0 cm−1, with 80 scans−1). A single spectrum was collected from each sample after subtraction of the background. After data acquisition, the recording and conversion of absorption spectra were performed using the Varian Resolutions Pro software program (Agilent Technologies, CA, USA); the spectra had subtraction of a baseline and were vectorial normalized and peak heights of each infrared band were analyzed (Origin Pro 8—OriginLab Corp., USA).

For analysis of the integrity of the collagen triple helix, the peak absorbance ratios of 1235 cm−1/1450 cm−1 were considered, in which a ratio closer to 1 denotes the maintenance of the integrity of amide III and CAH bonds of the pyrrolidine ring of the type-I collagen triple helix [19].

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed individually for each experimental phase of this study. Levene’s test and the Shapiro–Wilk test were carried out to determine the occurrence of equal variances and normality. For the evaluation of the integrity of the triple helix of collagen, the data were statistically analyzed using Kruskal–Wallis and Student–Newman–Keuls tests (Minitab 14, Minitab Inc.), at a 5% significance level. We used Mood’s median test to evaluate the cytotoxicity.

Results

Absorption spectra analysis of Papacarie Duo™, PapaUrucum™, and pure Urucum

We observed the optical characterization of Urucum absorption spectra in Papacarie Duo™, PapaUrucum™, and pure Urucum, and it shows that Papacarie Duo™ has no absorption band on the visible, while PapaUrucum™ has.

The UV absorption spectrum of Papa Urucum™ and pure Urucum exhibit a peak around 460 ± 20 nm on UV-range emission light, which is the same as annatto.

Cytotoxicity assay

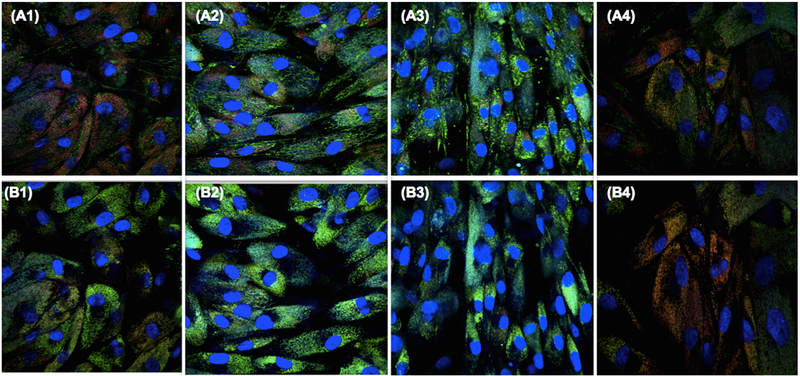

Based on the images obtained after confocal microscopy, shown in Fig. 4, there was no difference in the cell viability among the groups. In the viability assay, it was apparent that the values increased from 0 to 72 h with increasing dye concentration and time compared with the pure Urucum, both using 10–50 μM. Further, the assay shows there was a linear increase after 72-h incubation.

Fig. 4.

Organelles localize mitochondria and lysosomes in live cells, MitoTracker Green applied with PapaUrucum and Hoesch® were used. (A1) PapaUrucum 10 μM. (A2) PapaUrucum 20 μM. (A3) PapaUrucum 30 μM. (A4) PapaUrucum 40 μM. To localize lysosomes, LysoTracher® red was used; for internalization, Papa Urucum™. (B1) Papa Urucum 10 μM. (B2) PapaUrucum 20 μM. (B3) PapaUrucum 30 μM. (B4) PapaUrucum 40 μM

Confocal Fluorescence Microscopy for Subcellular Localization

To stain organelles and localize mitochondria in live cells and to localize lysosomes, LysoTracher® red was used; for internalization, PapaUrucum™ shows signal-to-noise ratio, and cell viability in all groups with different concentrations was applied to fibroblasts in the dark to evaluate any dark-cytotoxicity in vitro. Using both viability assays, it was apparent that the values increased with increasing dye concentration either pure Urucum or PapaUrucum™. In Fig. 4, we can see that there was a linear increase in hours up to 10–50 μM equivalent.

There was no statistical difference between the concentrations 10 up to 50 μM, but a linear increase was observed in hours up to equivalent 72 h after application with PapaUrucum™ and pure Urucum groups using either viability assay or MTT assay (Kruskal–Wallis p = 0.8).

Analysis of the effects of Papacarie Duo™, PapaUrucum™, and pure Urucum on collagen microstructure

Figure 5 evidences the normalized infrared spectra of the Urucum extract used in the present work. It is possible to see infrared bands corresponding to DNA (830 cm−1), deoxyribose (887 cm−1), carotenoid (945 cm−1), proteins such as amide I (1648 cm−1) and amide III (1250 cm−1), lipids (CH3 bending at 1468 cm−1 and 2870 cm−1), and O–H stretching (3426 cm−1).

Fig. 5.

(A) Mean infrared spectrum of Urucum (Bixa Orellana extract) obtained in region of 4000 to 600 cm−1. The arrows indicate the main peaks of greater intensity. (B) Mean infrared spectra of control and PapaUrucum obtained in the region of 4000 to 600 cm−1. The arrows indicate the main peaks of greater intensity

The normalized infrared spectra of control (Papacarie Duo™) and PapaUrucum™ are shown in Fig. 5. Both products present the same infrared bands that corresponded to the vibrations of DNA (839 cm−1), deoxyribose and ribose (924 and 945 cm−1, respectively), C–O stretching and bending of carbohydrates (1045 cm−1), polysaccharides (1108 cm−1), proteins such as amide I and III (1648 cm−1 and 1250 cm−1, respectively), lipids (CH3 bending at 1468 cm−1 and 2870 cm−1), and O–H stretching (3426 cm−1). The incorporation of pure Urucum into control (Papacarie Duo™) was not able to promote the appearance or disappearance of the infrared bands.

Figure 6 shows the average normalized infrared spectra of type-I collagen membrane treated with Milli-Q water, PapaUrucum™, and Papacarie Duo™ in the region of 4000 to 600 cm−1 (Fig. 6A) and the fingerprint region (Fig. 6B). It is noted that the application of a papain-based gel, with or without Urucum extract added, did not promote the appearance or disappearance of infrared bands, which indicates that these substances did not promote the degradation of collagen. However, all these substances increased the intensity of some infrared bands, such as O–H stretching (3426 cm−1) and polysaccharides (1108 cm−1).

Fig. 6.

Mean infrared spectra of type-I collagen membranes treated with Milli-Q water, PapaUrucum, and Papacarie Duo™. (A) Region of 4000 to 600 cm−1; (B) Region of 1800 to 700 cm−1

The application of PapaUrucum™ significantly increased the intensity of infrared bands located in the region between 1450 and 1045 cm−1, which corresponds to methyl groups of proteins (1450 and 1402 cm−1), CH2 wagging (1340 cm−1), amide III (1280 cm−1), a ring of polysaccharides (1107 cm−1), and C–O stretching and C–O bending of C–OH groups of carbohydrates (1045 cm−1).

Table 2 shows the results of the analysis of the integrity of the collagen triple helix for all experimental groups in the present study. It was noticed that the application of control (Papacarie Duo™) reduced the ratio of 1235 cm−1/1450 cm−1 peaks when compared with the Milli-Q water; the Urucum extract alone also decreased this ratio, but the reduction was less than that promoted by control (Papacarie Duo™). The application of PapaUrucum™ propitiated a higher decrease in the values of the ratio of 1235 cm−1/1450 cm−1 peaks when compared with control (Papacarie Duo™), and the statistical analysis (Kruskal–Wallis + Student Newman Keuls) evidenced no significant differences among groups at a 5% significance level.

Table 2.

Values (mean ± standard deviation) of the ratio of 1235 cm−1/1450 cm−1 peaks obtained for all experimental groups of this study

| Experimental group | Ratio |

|---|---|

| G1 - (Milli-Q water) | 1.000 ± 0.01 |

| G2 - (Control) | 0.884 ± 0.02 |

| G3 - (Pure Urucum) | 0.949 ± 0.04 |

| G4 - (PapaUrucum) | 0.923 ± 0.04 |

Discussion

The present study investigated the action of a Papacarie Duo™ (papain-based gel), anatto extract (Bixa Orellana extract), and PapaUrucum™ (the combination of Papacarie Duo™ with annatto) for the minimally invasive removal of carious lesions on dentin with safe application, aimed at reducing the population of cariogenic microorganisms and preserving sound dental tissue.

This is the first experimental study to evaluate the effectiveness of annatto to Papacarie Duo™ to perform application on live cell and collagen microstructure. Therefore, minimally invasive treatment combined with knowledge of dental caries such as this could be applied in dental treatment, as well as having a possibility of antimicrobial action in deep carious lesions with the help of photodynamic therapy.

The UV absorption spectrum of annatto has a peak at approximately 460 nm on UV-range emission light. Therefore, comparing the absorbance spectrum between 200 to 700 nm, that product could be used with an absorbance range between 230 and 550 nm. This justifies the application with blue light (550 nm) for photodynamic therapy.

According to the literature, an active dentine carious lesion is divided into four layers [8, 13, 22–24]. The necrotic surface layer must be removed. The underlying infected dentin exhibits a large number of bacteria, is entirely demineralized, has disorganized collagen, and must also be removed. Immediately below this layer, the affected dentin has undergone little change in its three-dimensional collagen structure and is capable of remineralization, exhibiting few or no bacteria, and should, therefore, be preserved. We should also maintain the deepest layer of dentin because it is more mineralized and still has intact collagen fibers [23, 24].

In our study, we observed that after the application of pure Urucum, Papacarie Duo™, and PapaUrucum, the collagen fibers’ microstructure integrity was maintained. One explanation for that observation is that healthy tissue contains alpha-1-antitrypsin, which is an antiprotease that blocks the action of the known proteolytic activity of papain [18, 23, 24].

PapaUrucum™ and pure Urucum were applied to human dermal fibroblasts. The dermal fibroblast lineage is similar to the dental pulp fibroblasts’ lineage and has relevance to the structural tissue organization of dentine. This is the first step to use the new papain-gel-added Urucum. The results are shown in Fig. 2.

It was apparent that the values increased from 0 to 72 h with increasing dye concentration and time 10% compared with the pure Urucum both using 10–50 μM. Using the MTT assay, there was a linear increase in hours up to 10–50 μM equivalent. The explanation for this increase in measures of viability, we believe, can be explained by the tendency of PapaUrucum™ to localize in mitochondria where it can act as an acceptor in the electron transport chain [20].

Since both assays (MTT) rely on the measurement of mitochondrial activity, this increase can be explained by either PapaUrucum™ or pure Urucum, causing an increase in electron transport in the mitochondria.

There was no statistical difference between the pure Urucum and PapaUrucum™ groups using either viability assay or the MTT assay (Kruskal–Wallis p = 0.8).

When using confocal fluorescence microscopy with organelle-species green fluorescent probes and blue nuclear stains to examine the subcellular localization in cells cultured with PapaUrucum™ or pure Urucum (Fig. 4), we observed that cationic dye present in the PapaUrucum™ could localize both in mitochondria and in lysosomes.

It can be seen that there were no significant differences between PapaUrucum™ and pure Urucum for cell viability, as we confirm on confocal microscopy in the images Fig. 4 A1–A4 and B1–B4, it can be seen that there is less red fluorescence due to photobleaching of the PapaUrucum™ dye.

ATR-FTIR spectroscopy is extremely indicated for the study of the chemical changes produced in the collagen structure. Moreover, type-I collagen fibers from human dentin are structurally similar to bovine Achilles deep tendon (employed in the present study) when evaluated using FTIR [25]. In the FTIR analysis, the helical structure of collagen is observed by the intensities of amides I and II. As well, the secondary structure of proteins can be evaluated by the intensity of amide I [26, 27]. Both amides I and II bands absorb in different regions if they are in an A-like helix or b-sheets [28]. Also, the hydrogen-bonding interactions, which are indicative of poly-peptide chains and assume regular secondary structures, can alter the infrared bands of amides I and II [27]. The amide I band is predominantly a C=O stretching mode, while the amide III band results from a mixture of N–H in-plane bending and C–N stretching as well as C–C stretching.

The integrity of the collagen triple helix evaluation is performed considering the ratio of the absorbance bands at 1235 cm−1, which corresponds to the amide III absorption band, and 1450 cm−1, which corresponds to the stereochemistry of the pyrrolidine rings and is independent of the ordered structure of collagen [29]. In the present study, Papacarie Duo™, both in its pure form and modified with a photosensitizing agent (PapaUrucum™), did not lead to the degradation of collagen, as demonstrated by FTIR (absorbance ratio values ≥ 0.8). The triple helix of collagen fiber integrity was maintained, considering that values near to 0.5 denote alteration on the three-dimensional structure of the type-I collagen triple helix, while a ratio about 1 indicates that the integrity of the secondary structure of type-I collagen is preserved [29].

The FTIR spectrum is characteristic of each molecule, which presents infrared bands that are characteristic of the vibrations of its functional groups. In this way, the structural information of a molecule depends on these infrared bands [30]. The range of the most significant use for the characterization of organic compounds is the mid-infrared (4000 and 400 cm−1) range [31–33], the same range used in the present study.

In this study, it was possible to characterize some aspects of the chemical structure of Urucum added to Papacarie Duo™. Infrared bands characteristic of carotenoids, proteins, and lipids were observed. Also, it was possible to evidence that the addition of this substance did not alter the chemical composition of Papacarie Duo™, as there was no appearance, disappearance, or displacement of its vibrational bands. However, the addition of the pigments reduced the intensity of the bands corresponding to the C–O, ν(CO), and ν(CC) bonds and polysaccharides. The addition of Bixa Orellana to the Papacarie Duo™ gel led to a decrease in the intensity of all bands in the collagen fingerprint region as well as decreased the intensity of the bands at 2874 and 2922 cm−1, corresponding to the CH3 and CH2 vibrations of lipids, respectively.

Future trends will try to produce different concentrations of annatto and papain that could be used to caries removal, preserving the affected dentin. Investigate the antioxidative effects of annatto on pork patties of collagen type-I membrane and interaction with light, to evaluate the possibility of the clinical use of PapaUrucum™, as well as its possible use for aPDT. This work confirms other studies on the concept ‘Minimally Invasive Dentistry’ through maximal preservation of healthy dental structures. Within cariology, this concept includes the use of all available information and techniques ranging from accurate diagnosis of caries, caries risk assessment and prevention, to technical procedures in repairing restorations.[34–36], [37, 38].

Conclusions

We can conclude that the application of Papa Urucum™ did not present cytotoxicity, its exhibit UV absorption spectrum peak around 460 ± 20 nm, which is compatible with blue light activation for PDT use. The PapaUrucum™ did not alter the chemical structure of collagen indicating that it is a potential tool for the treatment of carious lesions, combining the action of Papacarie Duo™ with a possible antimicrobial activity, as well as being a potential product for antimicrobial photodynamic therapy (aPDT) application.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully to Nove de Julho University to the technological support.

Funding information Z. Santos S. Jr. was finanacially supported by CAPES-Brazil grant 99999.002158/2014–00. M.R. Hamblin was financially supported by US NIH grant R01AI050875.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

The authors declare non-financial interests concerning the work described. M.R. Hamblin is also a present member of the Transdermal Cap, Inc. scientific advisory board.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Bussadori SK, Castro LC, Galvão AC (2006) Papain gel: a new chemo-mechanical caries removal agent. J Clin Pediatr Dent 30(2): 115–119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bussadori S, Guedes C, Hermida Bruno M, Ram D (2008) Chemo-mechanical removal of caries in an adolescent patient using a pa-pain gel: case report. J Clin Pediatr Dent 32(3):177–180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Motta LJ, Bussadori SK, Campanelli AP, Silva AL, Alfaya TA, Godoy CHL et al. (2014) Randomized controlled clinical trial of long-term chemo-mechanical caries removal using PapacarieTM gel. J Appl Oral Sci 22(4):307–313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Motta LJ, Bussadori SK, Campanelli AP, Silva AL, Alfaya TA, Godoy CHL et al. (2014) Efficacy of Papacarie¯ in reduction of residual bacteria in deciduous teeth: a randomized, controlled clinical trial. Clinics. 69(5):319–322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bohari MR, Chunawalla YK, Ahmed BMN (2012) Clinical evaluation of caries removal in primary teethusing conventional, chemomechanical and lasertechnique: an in vivo study. J Contemp Dent Pract 13(1):40–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kochhar GK, Srivastava N, Pandit I, Gugnani N, Gupta M (2011) An evaluation of different caries removal techniques in primary teeth: a comparitive clinical study. J Clin Pediatr Dent 36(1):5–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Singh S, Singh DJ, Jaidka S, Somani R (2011) Comparative clinical evaluation of chemomechanical caries removal agent Papacarie® with conventional method among rural population in India: in vivo study. Braz J Oral Sci 10(3):193–198 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bussadori S, Guedes C, Bachiega J, Santis T, Motta L (2011) Clinical and radiographic study of chemical-mechanical removal of caries using Papacarie: 24-month follow up. J Clin Pediatr Dent 35(3):251–254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kotb RMS, Abdella AA, El Kateb MA, Ahmed AM (2009) Clinical evaluation of Papacarie in primary teeth. J Clin Pediatr Dent 34(2):117–123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aguirre Aguilar AA, Rios Caro TE, Huamán Saavedra J, França CM, Fernandes KPS, Mesquita-Ferrari RA et al. (2012) Atraumatic restorative treatment: a dental alternative well-received by children. Rev Panam Salud Publica 31(2):148–152 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carrillo C, Tanaka M, Cesar M, Camargo M, Juliano Y, Novo N (2008) Use of papain gel in disabled patients. J Dent Child 75(3): 222–228 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jawa D, Singh S, Somani R, Jaidka S, Sirkar K, Jaidka R (2010) Comparative evaluation of the efficacy of chemomechanical caries removal agent (Papacarie) and conventional method of caries removal: an in vitro study. J Indian Soc Pedod Prev Dent 28(2):73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Matsumoto SFB, Motta LJ, Alfaya TA, Guedes CC, Fernandes KPS, Bussadori SK (2013) Assessment of chemomechanical removal of carious lesions using Papacarie Duo™: randomized longitudinal clinical trial. Indian J Dent Res 24(4):488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kush A, Thakur R, Patil SDS, Paul ST, Kakanur M (2015) Evaluation of antimicrobial action of Carie Care™ and Papacarie Duo™ on Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans a major periodontal pathogen using polymerase chain reaction. Contemp Clin Dent 6(4):534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fleischer T, Ameade E, Mensah M, Sawer I (2003) Antimicrobial activity of the leaves and seeds of Bixa orellana. Fitoterapia. 74(1): 136–138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shahid-ul-Islam Rather LJ, Mohammad F (2016) Phytochemistry, biological activities and potential of annatto in natural colorant production for industrial applications – A review. Journal of Advanced Research 7 (3):499–514 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Galindo-Cuspinera V, Rankin SA (2005) Bioautography and chemical characterization of antimicrobial compound (s) in commercial water-soluble annatto extracts. J Agric Food Chem 53(7):2524–2529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Betsy J, Prasanth CS, Baiju KV, Prasanthila J, Subhash N (2014) Efficacy of antimicrobial photodynamic therapy in the management of chronic periodontitis: a randomized controlled clinical trial. J Clin Periodontol 41:573–581 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Deppe H, Mucke T, Wagenpfeil S, Kesting M, Sculean A (2013) Nonsurgical antimicrobial photodynamic therapy in moderate vs severe peri-implant defects: a clinical pilot study. Quintessence Int 44:609–618 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Van Cuong T, Chin KB (2016) Effects of annatto (Bixa orellana L.) seeds powder on physicochemical properties, antioxidant and antimicrobial activities of pork patties during refrigerated storage. Korean J Food Sci Anim Resour 36(4):476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Garcez AS, Neto JG, Sellera DP, Fregnani E (2015) Effects of antimicrobial photodynamic therapy and surgical endodontic treatment on the bacterial load reduction and periapical lesion healing. Three years follow up. Photodiagn Photodyn Ther 12:575–580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Frencken JE, Makoni E, Sithole WD (1996) Atraumatic restorative treatment and glass ionomer cement sealants in school oral health programme in Zimbawe. Evaluation after 1 year. Caries Res 30(6): 428–33. 10.1159/000262355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brostek A (2003) Early diagnosis and minimally invasive treatment of occlusal caries–a clinical approach. Oral Health Prev Dent 2: 313–319 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Whitaker EJ (2006) Primary, secondary and tertiary treatment of dental caries: a 20-year case report. J Am Dent Assoc 137(3): 348–352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Botta SB, Ana PA, Santos MO, Zezell DM, Matos AB (2012) Effect of dental tissue conditioners and matrix metalloproteinase inhibitors on type I collagen microstructure analyzed by Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater 100(4):1009–1016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Williams RW, Dunker AK (1981) Determination of the secondary structure of proteins from the amide I band of the laser Raman spectrum. J Mol Biol 152(4):783–813 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Susi H (1972) Infrared spectroscopy–conformation. Methods Enzymol 26:455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ramabrahmam V (2005) Being and becoming: a physics and Upanishadic awareness of time and thought process.

- 29.Sylvester M, Yannas I, Salzman E, Forbes M (1989) Collagen banded fibril structure and the collagen-platelet reaction. Thromb Res 55(1):135–148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stuart B (2005) Infrared spectroscopy: Wiley online library. 10.1002/0471238961.0914061810151405.a01.pub2 [DOI]

- 31.Karoui R, Downey G, Blecker C (2010) Mid-infrared spectroscopy coupled with chemometrics: a tool for the analysis of intact food systems and the exploration of their molecular structure− quality relationships− a review. Chem Rev 110(10):6144–6168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Júnior ZSS, Botta SB, Ana PA, França CM, Fernandes KPS, Mesquita-Ferrari RA et al. (2015) Effect of papain-based gel on type I collagen-spectroscopy applied for microstructural analysis. Sci Rep 23(5):11448 10.1038/srep11448 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.George A, Veis A (1991) FTIRS in water demonstrates that collagen monomers undergo a conformational transition prior to thermal self-assembly in vitro. Biochemistry. 30(9):2372–2377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rojas JC, Bruchey AK, Gonzalez-Lima F (2012) Neurometabolic mechanisms for memory enhancement and neuroprotection of methylene blue. Prog Neurobiol 96(1):32–45 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ericson D, Kidd E, McComb D, Mjör I, Noack MJ (2003) Minimally invasive dentistry–concepts and techniques in cariology. Oral Health Prev Dent 1:1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bittencourt S, Pereira J, Rosa A, Oliveira K, Ghizoni J, Oliveira M (2010) Mineral content removal after Papacarie application in primary teeth: a quantitative analysis. J Clin Pediatr Dent 34(3):229–231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Banerjee A, Frencken JE, Schwendicke F, Innes NPT (2017) Contemporary operative caries management: consensus recommendations on minimally invasivecaries removal. Br Dent J 223(3):215–222. 10.1038/sj.bdj.2017.672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mackenzie L, Banerjee A (2017) Minimally invasive direct restorations: a practical guide. Br Dent J 223(3):163–171. 10.1038/sj.bdj.2017.661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]