Abstract

Objectives:

To compare the outcomes and comorbidities of children with MtD undergoing HTx to children without MtD.

Study design:

Using a unique linkage between the PHIS and SRTR databases, pediatric HTx recipients from 2002-2016 with a diagnosis of cardiomyopathy were included. Post-HTx survival and morbidities were compared between patients with and without MtD.

Results:

A total of 1,330 patients were included, including 47 (3.5%) with MtD. Post-HTx survival was similar between patients with and without MtD over a median follow-up of 4 years. Patients with MtD were more likely to have stroke after HTx (11% vs 3%, P = .009), require a longer duration of mechanical ventilation post-HTx (3 vs 1 day, p<0.001), and have longer post-HTx ICU length of stay (10 vs. 6 days, p=0.007). Absence of hospital readmission within the first post-transplant year was similar among patients with and without MtD (61.7% vs 51%, p = 0.14). However, patients with MtD who were readmitted demonstrated a longer length of stay compared with those without [median 14 days vs. 8 days, p = 0.03].

Conclusion:

Patients with MtD can successfully undergo HTx, with survival comparable with patients without MtD. Patients with MtD have greater risk for post-HTx morbidities including stroke, prolonged mechanical ventilation, and longer ICU and readmission length of stay. These results suggest that the presence of MtD should not be an absolute contraindication to HTx in the appropriate clinical setting.

Mitochondrial disease (MtD) is associated with the development of cardiomyopathy in up to 40% of patients (1). MtD is rare when considered individually, but as a group of conditions it is diagnosed with an estimated incidence of 1 in 5000 live births (2). Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy is the most common presentation of heart disease in this population, but dilated cardiomyopathy and left ventricular non-compaction also occur (1, 3). In patients with MtD, cardiomyopathy is the leading cause of death. Patients with MtD and cardiomyopathy have a reported mortality of 82% at 16 years of age, compared with 5% mortality in those without evidence of cardiac involvement (1).

The presence of cardiomyopathy may prompt consideration of heart transplantation (HTx) in children with MtD. However, there are limited data on HTx outcomes in this population and the presence of MtD may be considered a contraindication to HTx by some centers (4). The aim of this project was to utilize a novel linkage between administrative and clinical registry data to identify and compare HTx outcomes for children with MtD compared with those without.

Patients

This was a nested case-control study, utilizing a national cohort of patients with linked clinical and administrative data to compare transplantation outcomes in patients with and without MtD.

This study utilized a unique linkage between the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients database (SRTR, Hennepin Healthcare Research Institute, Minneapolis, MN) and the Pediatric Health Information System (PHIS, Children’s Hospital Association, Lenexa, KS) administrative and billing database. Records were linked at the patient level using indirect identifiers, the results of which have been validated for accuracy and previously described (5). The SRTR data system includes data on all donors, waitlisted candidates, and transplant recipients in the U.S., submitted by the members of the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN). The Health Resources and Services Administration, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services provides oversight to the activities of the OPTN and SRTR contractors. SRTR data are derived from multiple sources including the OPTN, transplant programs, organ procurement organizations, histocompatibility laboratories, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, and the National Technical Information Service’s Death Master File. The SRTR database includes data from every organ transplant and waitlist addition within the U.S. since October 1987. The PHIS database is an administrative database that collects clinical and resource utilization data for hospital encounters from >50 large children’s hospitals. Data collected includes encounter-level diagnosis and procedural International Classification of Diseases (ICD)-9 and ICD-10 codes, payer information, and detailed billing data for inpatient hospitalizations, observation, ambulatory surgery, and emergency department visits. (5).

All pediatric patients who underwent HTx with a diagnosis of cardiomyopathy were identified from the linked database for inclusion (2002 – 2016). For the purposes of this study, patients with ICD-9 or ICD-10 codes specific to MtD (Table I; available at www.jpeds.com) at any encounter are designated as having MtD, though confirmatory testing was not necessarily performed. The SRTR database did not contain codes for mitochondrial disease and was not used to identify patients with MtD.

Table 1.

Identifying the patient population

| ICD-9/10 Code | Diagnosis |

|---|---|

| 277.87* | Disorders of mitochondrial metabolism |

| E78.71 | Barth syndrome |

| E88.40 | Mitochondrial metabolism disorder, unspecified |

| E88.41 | MELAS syndrome |

| E88.42 | MERRF syndrome |

| E88.49 | Other mitochondrial metabolism disorders |

| G71.3 | Mitochondrial myopathy, not elsewhere classified |

| H49.81 | Kearns-Sayre syndrome |

| H49.811 | Kearns-Sayre syndrome, right eye |

| H49.812 | Kearns-Sayre syndrome, left eye |

| H49.813 | Kearns-Sayre syndrome, bilateral |

| H49.819 | Kearns-Sayre syndrome, unspecified eye |

ICD 9/10 codes shown in this table were used to query the linked PHIS and SRTR database. Patients with any combination of the above diagnoses at pre-transplantation, transplantation, or post-transplantation hospitalizations were included for analysis.

Denotes ICD-9. Other codes listed are ICD-10

Abbreviations: MELAS = mitochondrial encephalopathy, lactic acidosis, and stroke; MERRF = mitochondrial encephalopathy with ragged red fibers.

Pre-transplant clinical characteristics and post-transplant outcome data were derived from the linked data set. Primary outcomes of interest included survival to discharge, graft survival, and freedom from readmission. Immediate post-operative outcomes assessed prior to discharge from the HTx hospitalization included: rejection, pacemaker placement, cardiac reoperation, other surgical reoperation, chylothorax, use of extracorporeal membranous oxygenation (ECMO), dialysis, need for inhaled nitric oxide, intensive care unit (ICU) and total hospital length of stay, length of mechanical ventilation, and stroke. ICD codes indicating muscle weakness were also examined due to the potential for a higher incidence in the MtD population. Details of outcome identification are provided in Table 2 (available at www.jpeds.com).

Table 2.

Identifying patient outcomes

| Outcome | SRTR | PHIS |

|---|---|---|

| Muscle weakness | ICD 9: 728.87, V46.3, 359.89 ICD 10: M62.81, Z99.3, G71.3, G71.8, G72.89 |

|

| Chylothorax | ICD 9: 457.8 ICD 10: I89.8 |

|

| Stroke | REC_POSTX_STROKE | |

| Dialysis | REC_POSTX_DIAL | |

| Pacemaker | REC_POSTX_PACEMAKER | |

| Rejection | REC_POSTX_DRUG_TREAT_REJ | |

| Cardiac reoperation | REC_POSTX_CARDIAC_REOP | |

| Other operation | REC_POSTX_SURG | |

| iNO post-transplant | CTC code: 521173 | |

| In-hospital mortality | PHIS flag | |

| ECMO post-transplant | CTC code: 521180 - 521182 | |

| Total LOS | X | |

| ICU LOS | X | |

| Days of ventilation | X | |

| Days of iNO | X | |

| Readmission LOS | X | |

| Status and date of last known follow-up | X |

ICD 9/10 and SRTR codes shown in this table were used to query the linked PHIS and SRTR database to identify patient characteristics pre-transplantation, and outcomes post-transplantation.

X denotes that length of stay data was derived from the respective data bank

Abbreviations: ECMO = extracorporeal membranous oxygenation, ICU = intensive care unit, iNO = inhaled nitric oxide, LOS = length of stay

Statistical Analyses

Patient characteristics and post-HTx outcomes were compared between patients with and without MtD. Continuous variables were compared using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test and categorical variables were compared using the Fisher exact test, with a prespecified 2-sided alpha level of 0.05 considered the standard for statistical significance. To evaluate post-transplant graft survival, survival curves were generated using the Kaplan-Meier method (censoring at death, retransplantation, or last known follow-up) and compared using the log-rank test with a prespecified alpha level of 0.05 considered the standard for statistical significance. The Kaplan-Meier method was similarly employed to evaluate freedom from readmission within the first post-transplant year amongst patients with and without MtD. Power analysis and sample size calculations were not performed, as this was a retrospective analysis of all available data. All statistical analyses were performed in SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute; Cary, NC) or STATA version 15 (StataCorp LLC; College Station, TX).

To account for the observation that patients with MtD were younger, smaller and hospitalized longer pre-operatively, the primary analysis was repeated using a matched control group. The control group was randomly selected (5 controls for every 1 subject) after matching for age (+/−12 months), the need for VAD support, and the need for ventilator support at the time of HTx.

This project was approved by SRTR, PHIS and the Vanderbilt University Institutional Review Board.

Results:

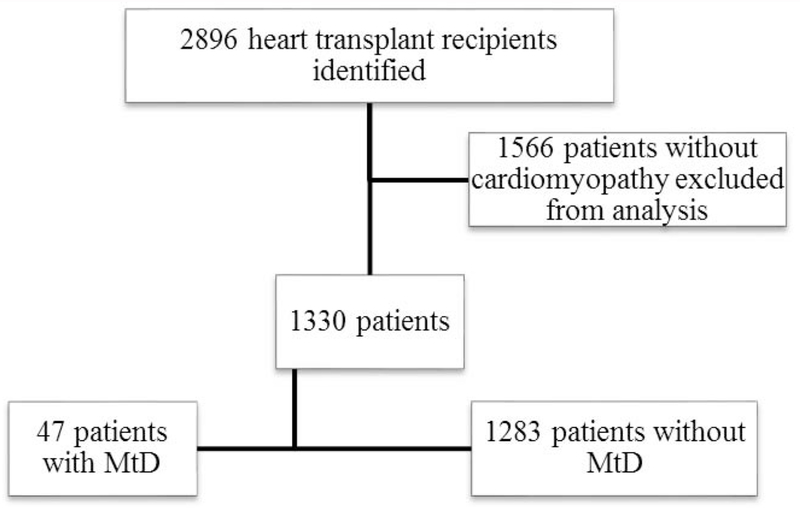

A total of 1,330 patients with cardiomyopathy were identified from the linked database and included in the analysis. Of this group, 47 (3.5%) patients were identified with MtD diagnosis codes (Figure 1; available at www.jpeds.com). The first occurrence of an ICD code defining MtD was noted prior to the transplant admission in 14 patients (30%). For the remaining patients, the first occurrence of an ICD code defining MtD occurred during (N=25, 53%) or following (N=8, 17%) the transplant admission. Patients with MtD also had higher incident muscle weakness than those without (29.8% vs. 3.5%, p <0.001).

Figure 1:

Identifying the patient population

Flow diagram describing the patient selection process. Abbreviation: MtD = mitochondrial disorder.

Patient demographics and pre-transplant clinical characteristics are shown in Table 3. Patients with MtD were significantly younger than those without (median age 22 months vs. 89 months, p = 0.004). Patients with MtD were also significantly smaller at time of HTx than those without (median weight 11 kg vs. 23 kg, p = 0.001). Of patients with MtD, 39 (83%) had dilated cardiomyopathy, 6 (13%) had hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, and 1 patient each had left ventricular non-compaction and histiocytoid cardiomyopathy. No patients with MtD carried a diagnosis of restrictive cardiomyopathy. Patients with MtD had a significantly longer pre-HTx hospital length of stay (median 41 days vs. 23 days, p = 0.004). There were no significant differences in sex, Unified Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) listing status, use of mechanical circulatory support, inotropic support, or inhaled nitric oxide at the time of HTx between those with and without MtD.

Table 3:

Pre-transplantation clinical characteristics

| Without MtD (n = 1,283) | With MtD (n = 47) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male | 650 (50.7%) | 26 (55.3%) | 0.56 |

| Age (months) at HTx* | 89 (14 – 168) | 22 (8 – 74) | 0.004 |

| Weight (kg) at HTx | 23 (9 – 50) | 11 (7 – 20) | 0.001 |

| Type of Cardiomyopathy | |||

| Dilated | 1,008 (78.6%) | 39 (83.0%) | 0.006 |

| Restrictive | 154 (12%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Hypertrophic | 73 (5.7%) | 6 (12.7%) | |

| Other | 48 (3.7%) | 2 (4.3%) | |

| Status at HTx | |||

| 1A | 1,105 (86.1%) | 42 (89.4%) | 0.15 |

| 1B | 111 (8.7%) | 1 (2.1%) | |

| 2 | 67 (5.2%) | 4 (8.5%) | |

| IV Inotrope requirement | 642 (50%) | 21 (44.7%) | 0.55 |

| VAD Pre HTx | 368 (28.7%) | 17 (36.2%) | 0.26 |

| ECMO Pre HTx | 58 (4.5%) | 0 (0%) | 0.26 |

| Pre-transplant length of stay (days)* | 23 (1 – 60) | 41 (12 – 82) | 0.004 |

| iNO Pre HTx | 46 (3.6%) | 2 (4.3%) | 0.69 |

| Muscle weakness | 45 (3.5%) | 14 (29.8%) | <0.001 |

For categorical variables, Fisher s exact test used. For continuous variables, Wilcoxon rank-sum used.

Abbreviations used: ECMO = extracorporeal membranous oxygenation, HTx = Heart transplantation, iNO = inhaled nitric oxide, MtD = Mitochondrial disease, VAD = Ventricular assist device

Results reported as: Median (Interquartile range)

Unmatched post-HTx outcomes are shown in Table 4. The in-hospital mortality following HTx was not different between those with and without MtD (2.1% vs. 1.8%, p=0.58). Patients with MtD had a significantly higher prevalence of post-operative stroke (11.1% vs. 2.7%, p=0.009), longer post-HTx (median 23 vs. 15 days; p<0.001) and ICU length of stay (median 10 vs. 6 days; p=0.007) and longer duration of mechanical ventilation post-HTx (median 3 days vs. 1 day, p<0.001). Patients requiring mechanical support (either VAD or ECMO) prior to transplantation had a significantly higher prevalence of post-HTx stroke than patients without pre-HTx mechanical stroke (Table 5; available at www.jpeds.com). When adjusting for pre-HTx use of mechanical support, MtD is independently associated with higher prevalence of post-HTx stroke (Table 6; available at www.jpeds.com). No statistically significant differences were noted between the two groups in terms of post-HTx need for ECMO, inhaled nitric oxide, pacemaker placement, dialysis, cardiac or non-cardiac surgery, or in the prevalence of chylothorax or rejection prior to hospital discharge.

Table 4:

Unadjusted outcomes after heart transplantation

| No MtD (n = 1,283) | MtD (n = 47) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| In Hospital Mortality | 23 (1.8%) | 1 (2.1%) | 0.58 |

| Stroke | 34 (2.7%) | 5 (11.1%) | 0.009 |

| ECMO Post-HTx | 99 (7.7%) | 3 (6.4%) | 1.0 |

| Nitric Oxide | 567 (44.3%) | 17 (36.2%) | 0.29 |

| Dialysis | 35 (2.74%) | 1 (2.3%) | 1.0 |

| Rejection | 131 (11.2%) | 4 (8.5%) | 0.81 |

| Pacemaker | 6 (0.5%) | 0 (0%) | 1.0 |

| Chylothorax | 38 (3.0%) | 0 (0%) | 0.64 |

| Cardiac Surgery | 49 (4.9%) | 2 (5.6%) | 0.69 |

| Non-cardiac Surgery | 93 (9.4%) | 5 (13.2%) | 0.39 |

| Tracheostomy | 20 (1.6%) | 2 (4.3%) | 0.18 |

| Post HTx hospital length of stay (days)* | 15 (11 – 24) | 23 (13 -47) | <0.001 |

| ICU length of stay (days)* | 6 (4 -13) | 10 (4 -28) | 0.007 |

| Time requiring mechanical ventilation (days)* | 1 (1 – 4) | 3 (2 – 9) | <0.001 |

| Time requiring inhaled nitric oxide (days)* | 3 (2 – 5) | 3 (2 – 4) | 0.43 |

| Readmission within 1 year of HTx | 644 (51%) | 29 (61.7%) | 0.14 |

| Readmission length of stay (days) | 8 (4 – 19) | 14 (8 – 23) | 0.03 |

For categorical variables, Fisher’s exact test used. For continuous variables, Wilcoxon rank-sum used.

Abbreviations used: ECMO = extracorporeal membranous oxygenation, HTx = heart transplantation, ICU= intensive care unit, MtD = Mitochondrial disease

Results reported as: Median (Interquartile range)

Table 5.

Univariate analysis of stroke and mechanical support

| Stroke | No stroke | P-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| VAD (N = 381) | 21 (5.5%) | 360 (94.5%) | 0.001 |

| ECMO (N = 58) | 8 (13.7%) | 50 (86.3%) | < 0.001 |

| No Mech. Support (N = 893) | 13 (1.5%) | 880 (98.5%) | < 0.001 |

Abbreviations: VAD = Ventricular Assist Device. ECMO = Extracorporeal membranous oxygenation. ECMO in this table refers to ECMO use prior to heart transplantation.

Data were compared using Fisher’s Exact Test.

Table 6.

Multivariable analysis of stroke

| Adjusted Odds Ratio | 95% CI | P-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mitochondrial Disease | 5.37 | 1.9 – 14.7 | <0.001 |

| ECMO pre-Tx | 8.6 | 3.62 – 20.4 | <0.001 |

| VAD pre – Tx | 3.23 | 1.67 – 6.26 | <0.001 |

Abbreviations: VAD = Ventricular Assist Device. ECMO = Extracorporeal membranous oxygenation. ECMO in this table refers to ECMO use prior to heart transplantation.

Data were analyzed using multivariable logistic regression with the binary outcome “postoperative stroke.”

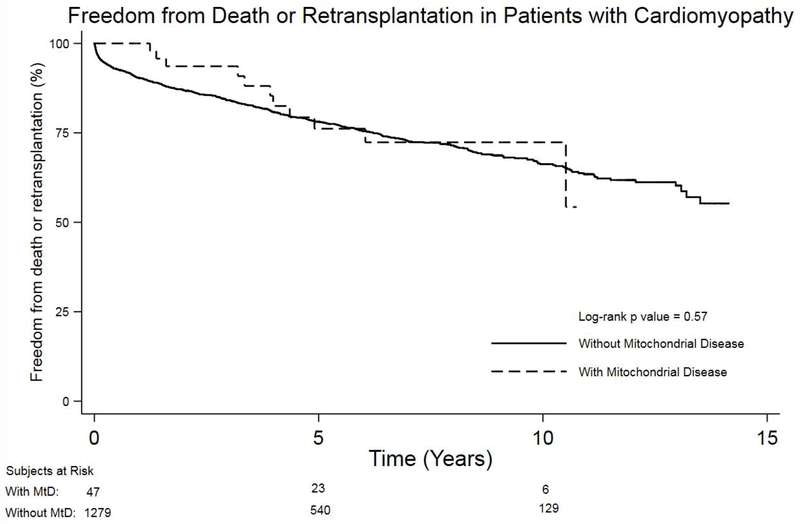

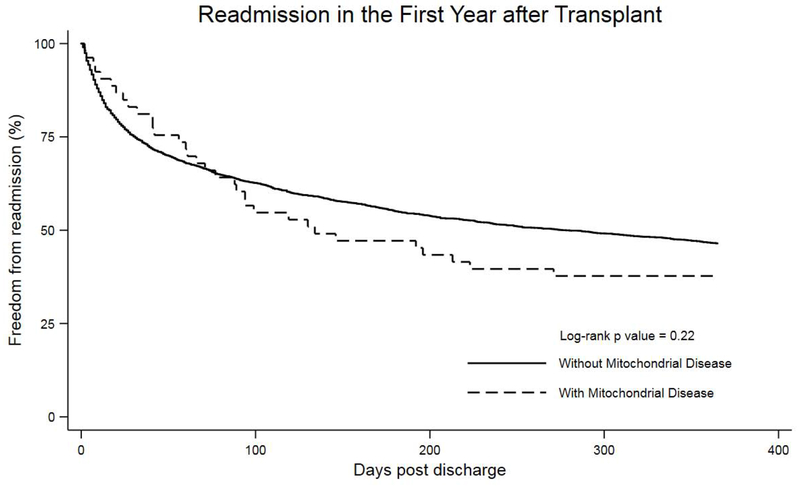

There was no difference in post-transplant graft survival in patients with MtD compared with those without (p=0.57) with a median follow-up of 4 years (range 1 – 11 years) (Figure 2). In the first year following hospital discharge, there was no difference in the frequency of readmission between patients with and without MtD (61.7% vs. 51%, p=0.14). Similarly, no significant difference was shown in time to readmission for patients with MtD compared with those without (p=0.22) (Figure 3). However, when readmitted to the transplant hospital, patients with MtD had a significantly longer length of stay compared with those without (median 14 days vs. 8 days, p = 0.03).

Figure 2:

Kaplan-Meier survival analysis comparing freedom from death or retransplantation between heart transplant recipients with and without mitochondrial disease.

Figure 3.

Kaplan-Meier survival curve comparing freedom from readmission in the first year after transplant between patients with and without mitochondrial disease.

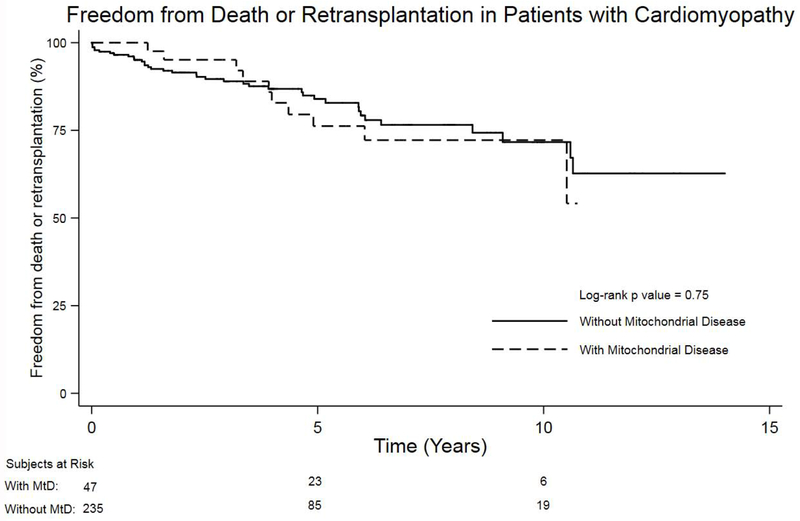

Results of the secondary matched analysis are summarized in the supplemental material. When matched for age, VAD support, and ventilator support, the prevalence of post-HTx stroke remained significantly higher in the MtD group (11.1% vs. 2.1%, p=0.01) (Table 7; available at www.jpeds.com). Similar to the primary analysis, there was no difference in post-transplant graft survival between patients with and without MtD (p=0.75) when using a matched control group (Figure 4; available at www.jpeds.com).

Table 7.

Matched control group secondary analysis

| Controls (n = 235) | MtD (n = 47) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at HTx (months)* | 20 (9 – 78) | 22 (8 – 74) | 0.99 |

| Weight at HTx (kg)* | 11 (7 – 23) | 11 (7 – 20) | 0.88 |

| In Hospital Mortality | 5 (2.1%) | 1 (2.1%) | 1.0 |

| Stroke | 5(2.1%) | 5 (11.1%) | 0.01 |

| ECMO Post-HTx | 23 (9.8%) | 3 (6.4%) | 0.59 |

| Nitric Oxide | 109 (46.6%) | 17 (36.2%) | 0.20 |

| Dialysis | 6 (2.6%) | 1 (2.3%) | 1.0 |

| Rejection | 19 (8.5%) | 4 (8.5%) | 1.0 |

| Pacemaker | (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1.0 |

| Chylothorax | 8(3.4%) | 0 (0%) | 0.36 |

| Cardiac Surgery | 12 (6.7%) | 2 (5.6%) | 0.58 |

| Non-cardiac Surgery | 20 (11.2%) | 5 (13.2%) | 0.78 |

| Total hospital length of stay (days)* | 59 (24 – 97) | 69 (28 – 140) | 0.10 |

| ICU length of stay (days)* | 7 (4 - 15) | 10 (4 -28) | 0.11 |

| Time requiring mechanical ventilation (days)* | 2 (1 – 6) | 3 (2 – 9) | 0.15 |

| Time requiring inhaled nitric oxide (days)* | 3 (2 – 5) | 3 (2 – 4) | 0.43 |

| Readmission within 1 year of HTx | 130 (55.3%) | 29 (61.7%) | 0.52 |

| Readmission length of stay (days) | 8 (4 – 24) | 14 (8 – 23) | 0.11 |

Patients with mitochondrial disease codes (MtD) matched 5:1 with controls for age (+/− 12 months, VAD, and ECMO support pre HTx).

For categorical variables, Fisher’s exact test used. For continuous variables, Wilcoxon rank-sum used.

Abbreviations used: ECMO = extracorporeal membranous oxygenation, HTx = heart transplantation, ICU= intensive care unit, MtD = Mitochondrial disease

Results reported as: Median (Interquartile range)

Figure 4:

Kaplan-Meier survival analysis comparing freedom from death or retransplantation between heart transplant recipients with mitochondrial disease and age/support matched controls.

Discussion:

There are limited prior data describing transplant outcomes in patients with MtD. Case reports and case series describe successful transplantation in patients with cardiomyopathy secondary to MtD (6–11). Bates et al. describe a series of five patients with cellular evidence of MtD (using endomyocardial biopsy pre-transplant) but with no manifestation of disease in other organs. These patients had normal post HTx courses. (7) In addition, several cases of HTx in patients with MtD with isolated cardiac disease have been reported (6, 8). Other case reports exist which highlight transplantation in patients with mitochondrial encephalopathy, lactic acidosis, and stroke-like episodes (MELAS) who also had successful outcomes. (9, 12). Conversely, Parikh et al. caution against solid organ transplantation in this population, citing postoperative complications and graft failure in 6 of 11 HTx patients (4).

Patients in our analysis likely represent a select cohort with minimal comorbidities. Patients with MtD and significant extra-cardiac manifestations are more likely to be precluded from transplant candidacy. The utilization of an MtD code was made in only 30% of patients during a hospitalization prior to HTx with the majority of patients receiving this diagnostic code during or following their HTx admission. This suggests that for some patients, transplant providers may have been unaware of the MtD diagnosis at the time of listing for HTx. Although our data support that HTx in this group can achieve similar outcomes to patients without MtD, these data may not be generalizable to patients with MtD and significant extra-cardiac comorbidities, and careful assessment of transplant candidacy in each patient is warranted.

When considering morbidity patterns in these patients, it is notable that patients with MtD demonstrate a significantly higher prevalence of post-HTx stroke than those without. Multiple possible explanations could account for this finding. Several mitochondrial diseases, most notably MELAS, confer a higher risk of metabolic stroke. It is also possible that having any level of impaired mitochondrial function, coupled with the stress of heart failure, cardiopulmonary bypass, and postoperative recovery can increase the risk of stroke-like episodes.

Patients with MtD required a longer duration of mechanical ventilation in the post-HTx period and had longer post-HTx total and ICU length of stay. Although the etiology for these findings cannot be precisely determined in our analysis, the presence of muscle weakness (whether apparent or sub-clinical) in patients with MtD may prolong the need for post-operative positive pressure ventilation, resulting in a longer post-HTx length of stay. Patients with MtD did demonstrate a significantly higher incidence of muscle weakness, supporting this as a possible etiology for our findings. Given that we found no difference in other post-HTx complications including rejection, dialysis, ECMO, pacemaker, cardiac or non-cardiac reoperation, it is reasonable to consider the significant difference in mechanical ventilation time as a likely contributor to the prolonged length of stay.

Although the length of stay post-transplant is increased in patients with MtD, readmission after transplantation are similar between groups. However, when patients with MtD are readmitted to the hospital, they again demonstrate a significantly longer length of stay compared with patients without MtD. The etiology of this finding is unclear and warrants further investigation.

The higher prevalence of metabolic stroke and muscle weakness in HTx patients with MtD should inform physicians in their perioperative management of this population. As an example, this population may benefit from different ventilation strategies given their propensity for impaired respiratory mechanics. It can be hypothesized that the higher prevalence of metabolic stroke is a result of metabolic demand and impaired respiratory chain metabolism, for which prophylaxis would be difficult. Knowledge of this risk can be used to inform pre-HTx counseling and to prepare the intensive care unit for careful neurologic monitoring after HTx.

There are inherent limitations to this study. The diagnosis of MtD is challenging, and assessment of these diagnoses using ICD codes may introduce error due to mis-coding. This may result in patients with MtD who were not identified, or patients without MtD incorrectly labelled as having MtD. Unfortunately, there are limited options to validate this classification within the linked database. Although the linkage between SRTR and PHIS provides a platform to assess transplantation outcomes in this population, it does not contain data from all pediatric transplant centers. Therefore, it may miss some patients with MtD who have undergone HTx. In addition, the SRTR-PHIS linkage does not include patients who were listed but not transplanted; therefore, waitlist outcomes for this group are not known. Also, there is likely a selection bias in patients with MtD listed, with only the “healthiest” progressing to transplantation. Although ICD coding allowed identification of patients with probable MtD, there may be inaccuracies in coding and limited options to verify these data. Additionally, “mitochondrial disease” is a heterogeneous term representing a host of rare diseases with similar cellular physiology but potentially variable pathology; comparing post-operative morbidity among these patients may be biased by a preponderance of one specific diagnosis. Unfortunately, ICD 9 codes do not allow identification of specific forms of MtD. This improved with ICD 10 coding, but only a minority of our patients had these codes, limiting our ability to define specific forms of MtD. When considering stroke, data were not available to compare those with metabolic stroke (more inherent in the MtD population) to embolic or ischemic stroke.

These results suggest that a diagnosis of MtD alone should not serve as an absolute contraindication to heart transplantation. However, because of the likely selection bias in our cohort, these data may not be generalizable to all patients with MtD and each patient should be evaluated on an individual basis to determine transplant candidacy.

Acknowledgments

Supported through internal funding from the Katherine Dodd Faculty Scholar Program at Vanderbilt University (to J.G.). Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health (T32HL05334 [to J.W.] and K23HL123938 [to J.S.] [Bethesda, Maryland]. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

- SRTR

Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients database

- PHIS

Pediatric Health Information System

- OPTN

Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network

- ICD

International Classification of Diseases

- ECMO

extracorporeal membranous oxygenation

- ICU

intensive care unit

- VAD

ventricular assist device

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References:

- 1.Scaglia F, Towbin JA, Craigen WJ, Belmont JW, Smith EO, Neish SR, et al. Clinical spectrum, morbidity, and mortality in 113 pediatric patients with mitochondrial disease. Pediatrics. 2004;114(4):925–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bannwarth S, Procaccio V, Lebre AS, Jardel C, Chaussenot A, Hoarau C, et al. Prevalence of rare mitochondrial DNA mutations in mitochondrial disorders. J Med Genet. 2013;50(10):704–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Limongelli G, Tome-Esteban M, Dejthevaporn C, Rahman S, Hanna MG, Elliott PM. Prevalence and natural history of heart disease in adults with primary mitochondrial respiratory chain disease. Eur J Heart Fail. 2010;12(2):114–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Parikh S, Karaa A, Goldstein A, Ng YS, Gorman G, Feigenbaum A, et al. Solid organ transplantation in primary mitochondrial disease: Proceed with caution. Mol Genet Metab. 2016;118(3):178–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Godown J, Thurm C, Dodd DA, Soslow JH, Feingold B, Smith AH, et al. A unique linkage of administrative and clinical registry databases to expand analytic possibilities in pediatric heart transplantation research. Am Heart J. 2017;194:9–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Golden AS, Law YM, Shurtleff H, Warner M, Saneto RP. Mitochondrial electron transport chain deficiency, cardiomyopathy, and long-term cardiac transplant outcome. Pediatr Transplant. 2012;16(3):265–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bates MG, Nesbitt V, Kirk R, He L, Blakely EL, Alston CL, et al. Mitochondrial respiratory chain disease in children undergoing cardiac transplantation: a prospective study. Int J Cardiol. 2012;155(2):305–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Santorelli FM, Gagliardi MG, Dionisi-Vici C, Parisi F, Tessa A, Carrozzo R, et al. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and mtDNA depletion. Successful treatment with heart transplantation. Neuromuscul Disord. 2002;12(1):56–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bhati RS, Sheridan BC, Mill MR, Selzman CH. Heart transplantation for progressive cardiomyopathy as a manifestation of MELAS syndrome. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2005;24(12):2286–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schmauss D, Sodian R, Klopstock T, Deutsch MA, Kaczmarek I, Roemer U, et al. Cardiac transplantation in a 14-yr-old patient with mitochondrial encephalomyopathy. Pediatr Transplant. 2007;11(5):560–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bonnet D, Rustin P, Rotig A, Le Bidois J, Munnich A, Vouhe P, et al. Heart transplantation in children with mitochondrial cardiomyopathy. Heart. 2001;86(5):570–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fayssoil A Heart diseases in mitochondrial encephalomyopathy, lactic acidosis, and stroke syndrome. Congest Heart Fail. 2009;15(6):284–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]