Summary

Cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I) is the preferred treatment for chronic insomnia and sleep-related cognitions are one target of treatment. There has been little systematic investigation of how sleep-related cognitions are being assessed in CBT-I trials and no meta-analysis of the impact of CBT-I on dysfunctional beliefs about sleep, a core cognitive component of treatment. Academic Search Complete, Medline, CINAHL and PsychInfo from 1990–2018 were searched to identify randomized controlled trials of CBT-I in adults (≥18 years) reporting some measure of sleep-related cognitions. Sixteen randomized controlled trials were identified comparing 1134 CBT-I and 830 control subjects. The Dysfunctional Beliefs and Attitudes about Sleep Scale was utilized almost exclusively to assess sleep-related cognitions in these trials. Hedge’s g at 95% confidence interval (CI) was calculated to assess CBT-I effect size at post-treatment compared to controls. CBT-I significantly reduced dysfunctional beliefs about sleep (g = −0.90, 95% CI −1.19, −0.62) at post-treatment Three trials contributed data to estimate effect size for long-term effects (g= −1.04 (95% CI −2.07, −0.02) with follow up time ranging from 3 – 18 months. We concluded that cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia has moderate to large effects on dysfunctional beliefs about sleep.

Keywords: Dysfunctional Beliefs about Sleep, DBAS, Cognitive Behavioral Therapy, Insomnia, CBT-I, Sleep-related cognitions

Numerous systematic reviews and meta-analyses have established the efficacy of cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I) for improving several sleep-wake parameters and insomnia symptoms (1–10). Research across CBT-I trials has primarily focused on the behavioral components of treatment, mainly sleep restriction and stimulus control. Both strategies have been shown to be effective for insomnia even if delivered as standalone treatments (11–16). Less attention has been given to the cognitive components of CBT-I. The objective of cognitive strategies in CBT-I is to break the cycle of dysfunctional beliefs about sleep that can lead to, maintain, or worsen insomnia. Cognitive restructuring, which involves identifying and challenging dysfunctional cognitions and unrealistic expectations that can perpetuate insomnia, along with Socratic questioning to facilitate learning (17,18), is one widely used cognitive strategy. There have been limited systematic reviews of the effectiveness of cognitive components of CBT-I and measurement of sleep-related cognitions in randomized trials.

Several theoretical models of insomnia recognize sleep-related cognitions that perpetuate insomnia symptoms. Increased worry and rumination about lack of sleep can increase cognitive arousal and decrease likelihood of falling asleep (19,20). Lack of sleep can lead individuals to engage in failed explicit attempts to produce sleep further increasing cognitive arousal (21). Individuals may also develop erroneous beliefs about sleep that lead to maladaptive behaviors such as napping or avoiding challenging tasks (22). The measurable concepts associated with these mechanisms could potentially include, but are not limited to: sleep locus of control (23), dysfunctional beliefs and attitudes about sleep (22), sleep effort (24), sleep self-efficacy (25), sleep-related worry (26), anxiety and preoccupation about sleep (27), and insomnia symptom rumination (28). However, it is unclear whether changes in sleep-related cognitions are being reported and which measures, if any, are being collected in CBT-I trials.

We thus conduct a literature review and meta-analysis to answer the following research questions:

How are sleep-related cognitions assessed and reported across CBT-I trials?

What is the effect of CBT-I on sleep-related cognitions?

METHODS

We performed a systematic review and meta-analysis in accordance with the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines (29). We assessed for risk of bias using the Revised Cochrane risk-of-bias tool for randomized trials (RoB 2) from the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews (30). The predetermined methods were registered online with PROSPERO (Reg. CRD42018112173).

Data Sources and Searches

We searched Academic Search Complete, Medline, CINAHL, and PsychInfo with the terms “cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia,” “sleep restriction,” “cognitive restructuring,” and “sleep behavior therapy” for publications from 1990–2018 in peer-reviewed journals and written or translated in English. We also reviewed the reference lists of 5 review articles (1,4,31,32).

Study Selection

We sought to identify randomized controlled trials (RCT) of CBT-I in adults (aged ≥18 years) reporting some measure of sleep-related cognitions. We identified the following treatments as being part of CBTI: relaxation, sleep restriction, stimulus control, and cognitive restructuring, including identifying and challenging dysfunctional thoughts about sleep. Acceptable control groups included wait list, no treatment/usual care, sleep hygiene or general health education, or alternative inactive control condition. We did not specify mode of delivery or length of treatment as inclusion criteria to maximize data capture. All measures targeting sleep-related cognitions as identified in our search were allowed, including the Dysfunctional Beliefs and Attitudes Scale (DBAS) (22), Sleep Locus of Control Scale (23), Sleep Effort Scale (24), Sleep Self-efficacy Scale (25), Sleep-related Worry Questionnaire (33), Anxiety and Preoccupation about Sleep Questionnaire (19), Sleep Disturbance Questionnaire (34) and Daytime Insomnia Symptom Response Scale (28). We excluded trials with only measures of hyperarousal or testing cognitive performance or impairment without any measure of sleep-related cognitions.

Data Extraction

For each CBT-I trial, the first author completed all data collection, extraction and coding. Trials in which the effect on sleep-related cognitions were reported, were also investigated for protocol papers and other primary or secondary results papers if necessary, for extracting relevant data for the meta-analysis and summary of evidence tables. Trials testing multiple treatments or modes of delivery were included but only data for arms testing CBT-I and an acceptable control condition were extracted for meta-analysis. When necessary data were missing, the authors of the articles were contacted and requested to provide these data. No inter-rater reliability ratings were collected because all data were extracted and coded by the first author.

Data Synthesis and Analysis

We examined the effects reported immediately after treatment (post-test) for the intervention versus control groups using the available published statistics or obtained from the corresponding author. Hedges’s g, a variation of Cohen’s d correcting for possible bias due to small sample size was used as the standardized effect size (35). Effect sizes were computed using post-intervention means and their standard deviations or standard errors. Pooled effect sizes were weighted by the inverse standard error, considering the precision of each study. A random effects model was chosen for all analyses. A negative value was chosen to indicate an effect size in the expected direction, e.g., less dysfunctional beliefs. If necessary, independence of results was ensured by averaging effect sizes across all subgroups so that only one result per study was used for each quantitative data synthesis. Effect sizes of 0.56–1.2 can be assumed to be large, while effect sizes of 0.33–0.55 are moderate, and effect sizes of 0–0.32 are small (36).

To calculate the individual effect sizes as well as the pooled mean effect size we used the computer program Comprehensive meta-analysis (CMA) version 3.3.070 for Windows, developed for support in meta-analysis (www.metaanalysis.com). Long-term effect sizes were estimated for studies with DBAS assessments beyond post-treatment for intervention and control groups using the time point furthest from baseline. Publication bias was assessed with funnel plots, Trim and Fill method (37) and the Egger test (38).

RESULTS

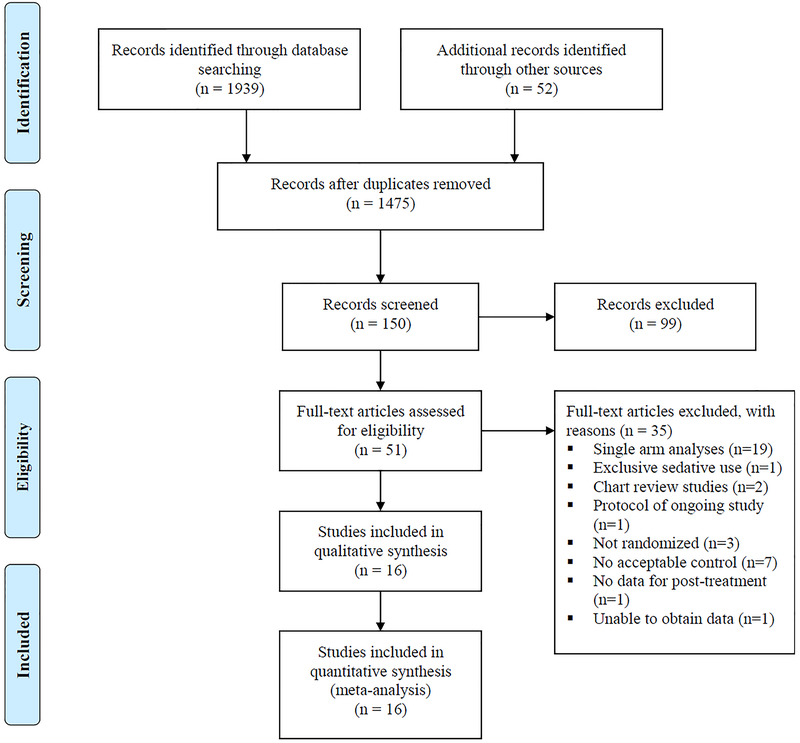

Our search strategy identified 1475 references for review of the title and abstract after removal of duplicates. Of these, 150 articles were considered potentially appropriate for inclusion and the full text was obtained and reviewed for 51 studies. Sixteen studies met the criteria for inclusion and contributed data to the pooled estimates presented (39–54). The study flow diagram with reasons for exclusion is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of Literature Search Results

Study Characteristics

Table 1 reports descriptive data for the 16 included studies, which involved a total of 1964 participants (range 34 to 312 participants per study): 1134 in CBT-I, and 830 in control. Most study populations were of late or middle age (mean age 49.7 years). Sex was predominantly female (68.1%), and all trials were performed in developed countries. Three trials recruited from health centers either by direct referral from clinicians (39,41,42), one from identification of electronic health records (45), and the remaining recruited individuals in the general community through print and online advertisements. Eleven trials defined insomnia using criteria from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (55) (40–44,47,48,50–53) while three referred to research diagnostic criteria defined by the American Academy of Sleep Medicine (56) (45,46,49). The remaining two trials used the Insomnia Severity Index score indicating mild chronic insomnia for eligibility (39,54). Several trials targeted populations with specific comorbidities including cancer (39,42), heart disease (54), and osteoarthritis (45). Only 2 trials excluded individuals on the basis of sedative or hypnotic medication use (42,51) and one trial included information about a cessation program for participants wishing to discontinue sedative/hypnotic use under medical supervision as part of the CBT-I intervention (39).

Table 1.

Characteristics of Randomized Trials of CBT-I

| Study, year | N total | Diagnosis | Mean Age (SD) | Location | % Women | CBT-I protocol when/how often | Mode of Delivery | Comparator | DBAS Item # |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Casault, 201539 | 38 | Nonmetastatic cancer and insomnia | 56.9 | Canada | 92.1 | 9 sessions over 6 weeks | Self-help book/telephone reinforcement | Usual care | 13 |

| Chow, 201840 | 303 | Insomnia | 43.3 (11.6) | USA | 72.0 | 1 module released 7 days after completion of the previous, total 6 modules | Online fully automated | Selfmanagement education | 16* |

| Edinger, 200147 | 70 | Insomnia | 55.3 (10.5) | USA | 46.7 | 6 sessions over 6 weeks | Individual inperson, first session audiotape | Behavioral placebo | 10 |

| Horsch, 201748 | 153 | Insomnia | 41.0 (13.9) | Netherlands | 64.0 | 6–7 weeks self-paced | Online fully automated | Waitlist | 16 |

| Jernelov, 201249 | 135 | Insomnia | 47.9 (13.9) | Sweden | 82.0 | Self-help book or book with 6 weekly telephone calls | Telephone | Waitlist | 30 |

| Lancee, 201550 | 63 | Insomnia | 50.0 (13.7) | Netherlands | 83.3 | 6 modules over 6 weeks | Online with individual email feedback | Waitlist | 16 |

| Lovato, 201451 | 118 | Insomnia | 64.0 | Australia | 50.0 | 4 sessions over 4 weeks | In-person group | Waitlist | 16 |

| Mimealt, 199952 | 54 | Insomnia | 50.8 (12.6) | Canada | 59.0 | Self-paced over 6 weeks with telephone support, materials mailed once per week | Self-paced with and without weekly telephone reinforcement | Waitlist | 30 |

| Morin, 200253 | 38 | Insomnia | 65.0 (6.5) | USA | 64.1 | 8 sessions over 8 weeks | In-person group | Medication placebo | 28 |

| Redeker, 201754 | 48 | Heart failure and insomnia | 59.2 (14.8) | USA | 52.1 | 8 sessions over 8 weeks | In-person group alternating telephone support | Selfmanagement education | 28* |

| Sandlund, 201841 | 129 | Insomnia | 55 (17.1) | Sweden | 71.7 | 7 sessions over 10 weeks | In-person group | Usual care | 16 |

| Savard, 201442 | 241 | Breast cancer and insomnia | 54.4 (8.8) | Canada | 100 | 6 sessions over 6 weeks or 6 videos | In-person individual or video | Usual care | 16 |

| Strom, 200443 | 81 | Insomnia | 44.1 (12.0) | Sweden | 71.0 | 5 sessions over 5 weeks | Online with individual email feedback | Waitlist | 28 |

| Taylor, 201444 | 34 | Insomnia | 20.0 (2.5) | USA | 41.2 | 6 sessions over 6 weeks | In-person Individual | Waitlist | 16 |

| Vitiello, 201345 | 245 | Osteoarthritis and insomnia | 73.0 (8.4) | USA | 80.3 | 6 sessions over 6 weeks | In-person group | Selfmanagement education | 10 |

| Yan-Yee Ho, 201446 | 312 | Insomnia | 38.5 (12.5) | China | 71.1 | Self-paced over 6 weeks, materials delivered once per week | Online | Waitlist | 10 |

CBT-I was delivered over a minimum of 6 and maximum of 10 weeks either in-person group (n=4), self-paced in print or online (n=6), in-person individual (n=3), or telephone (n=4) (non-mutually exclusive groups). Comparator control groups consisted of a waiting list or usual treatment (n=11), self-management education (n=3), alternative behavioral intervention (n=1), and medication placebo (n=1). Of the 16 included trials, four trials had more than one intervention group; in three out of these four trials a self-help format of CBT-I was compared to a self-help format with telephone support from a designated intervention provider (46,49,52) and the remaining trial tested individual in-person to pre-packaged DVD CBT-I program (42) All intervention providers were either trainee or licensed mental health professional. Six trials reported that either audio or video recordings of CBT-I sessions were reviewed to assess the interventionists’ fidelity to the treatment protocol (42,44,47,51,54,57) while four trials utilized debrief and consultation sessions between interventionists and professionals experienced with CBT-I (40,41,45,50), and the remaining provided no details about fidelity.

The DBAS was employed in all trials assessing sleep-related cognitions. The majority of trials selected the 16-item DBAS as the primary sleep-cognition instrument (7 out of 16 trials) (40,42,44,48,50,51,53), five trials used the 30 or 28-item (43,49,52–54), three trials used 10-item (45–47), and one trial used 13-item (39). One trial included two additional sleep-cognition measures: Sleep Locus of Control and Sleep Self-efficacy (40), and another trial included Sleep Disturbance Questionnaire (54). The primary outcome for 13 out of 16 trials was the Insomnia Severity Index (58); two trials used measures of sleep-wake time (43,52); and the remaining trial used the Fatigue Severity Scale (59) (41).

In referring to the cognitive component of therapy, 13 of 16 trials reported cognitive restructuring as the primary technique. Two trials did not include any cognitive components of CBT-I: Vitiello et al. (2013) combined behavioral components of CBT-I with cognitive behavioral therapy for pain, and Horsch et al. (2017) included only relaxation, sleep restriction, and sleep hygiene (45,48).The remaining trial made reference to techniques to improve sleep and cope with worry with no mention of cognitive restructuring, specifically (41). Additionally, one trial reported using the Automatic Thought Record technique where participants are asked to explore the situation and intensities of emotions associated with automatic thoughts about sleep (46), and another reported using the Constructive Worry technique in which the time, place and method of worry is clearly prescribed such that the process is not sleep disruptive (41).

Study Quality

Methods for randomization were generally reported in detail with a few exceptions (Table 2). Bias due to deviations from intended interventions were avoided by a majority of the studies by using intent-to-treat analyses resulting in a low risk assessment for that domain. Trials used single and multiple imputation methods to adjust for differential retention rates across groups and address missing outcome data, resulting in generally low risk assessment. Most studies did not use blinding techniques for participants because in many cases it wasn’t feasible due to the nature of the intervention and a wait list or no treatment control group. Per the Cochrane risk of bias tool (30), knowledge of intervention rises to the level “Some concerns” for outcomes where it is unlikely that knowledge of intervention could influence reporting of that outcome, i.e. bed time or rise time. “High” risk assessment is indicated for outcomes where it is likely that knowledge of intervention could influence reporting of that outcome, as in the DBAS. For example, “…insomnia is ruining my ability to enjoy my life…” is a DBAS item where it is likely that participant reporting could be influenced by knowledge of the intervention and thus judged as “High”. As a result, 73.3% of included trials with either waitlist or no treatment control groups were judged as “High” risk for bias in measurement of outcome domain.

Table 2.

Risk-of-bias assessment

| Author, year | Bias arising from the randomization process | Bias due to deviations from intended interventions | Bias due to missing outcome data | Bias in measurement of the outcome | Bias in selection of the reported result | Overall assessment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Casault, 201539 | Low | Low | Low | High | Low | Some concerns |

| Chow, 201840 | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Edinger, 200147 | Low | Low | High | Low | Low | Some concerns |

| Horsch, 201748 | Low | Low | Low | High | Low | Some concerns |

| Jernelov, 201249 | Low | Low | Low | High | Low | Some concerns |

| Lancee, 201550 | Some concerns | Low | Low | High | Low | Some concerns |

| Lovato, 201451 | Some concerns | Low | Low | High | Some concerns | Some concerns |

| Mimealt, 199952 | Some concerns | Low | Low | High | Low | Some concerns |

| Morin, 200253 | Low | Low | Low | Some concerns | Some concerns | Some concerns |

| Redeker, 201754 | Some concerns | Some concerns | Low | Low | Low | Some concerns |

| Sandlund, 201841 | Low | Low | Low | High | Low | Some concerns |

| Savard, 201442 | Low | Some concerns | Some concerns | High | Low | Some concerns |

| Strom, 200443 | Some concerns | Some concerns | High | High | Low | Some concerns |

| Taylor, 201444 | Low | Low | Low | High | Low | Some concerns |

| Vitiello, 201345 | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Yan-Yee Ho, 201446 | Low | Low | Low | High | Low | Some concerns |

Post-Treatment Effects

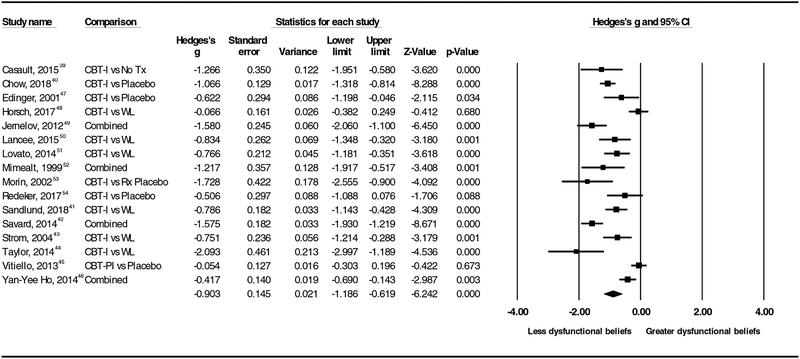

As seen in Figure 2 under the random effects model the point estimate and 95% confidence interval for the combined studies is g= −0.90 (−1.19, −0.62). Using Trim and Fill method, these values are unchanged. The significant effect sizes ranged from large (−2.09) to moderate (−.42). Effect sizes for three trials did not reach statistical significance; two of those three trials included only behavioral components of CBT-I and no cognitive components. Egger’s test of asymmetry in the distribution of effect sizes did not reach statistical significance (p= 0.09). Three studies contributed data to estimate effect size for long-term effects (g= −1.04, 95% CI −2.07, −0.02) with follow up time ranging from 3 – 18 months.

Figure 2.

Forest Plot of Included Trials and Effect Sizes, No Tx – No treatment, Placebo – placebo behavioral control, WL – waitlist, Rx Placebo – medication placebo, Combined – Effect size is averaged between 2 comparisons of intervention and control (3 arm trials).

DISCUSSION

Our first aim was to understand how sleep-related cognitions were being assessed across CBT-I trials. We found that the DBAS was the primary sleep-related cognitions instrument for all 16 included trials. One reason for the popularity of the DBAS could be that several validated CBT-I programs specifically mention identification and challenging of dysfunctional beliefs about sleep as a core component (18,60,61). This component is meant to facilitate identification of maladaptive sleep cognitions, challenging their validity, and reframing them as more adaptive thoughts. The principal beliefs and attitudes addressed are based on the Dysfunctional Beliefs and Attitudes Scale (DBAS) 30-items which include five subscales (a) misattribution or amplification of the consequences of insomnia (e.g. “I cannot function without adequate sleep”), (b) control and predictability of sleep (e.g. “Insomnia is destroying my entire life”), (c) unrealistic sleep expectations (e.g. “I should sleep as well as my bed partner”), (d) misconceptions about the causes of insomnia (e.g. “Insomnia is due to a chemical imbalance”) and (e) faulty beliefs about sleep-promoting practices (e.g. “If I try harder, I will eventually fall asleep”) (62). We found that 6 of the 16 included trials utilized the 16-item version, three utilized the 10-item, one utilized the 13-item, and the remaining the 30 or 28-item versions. The psychometric properties of the 10, 16 and 30-item DBAS have been compared and a significantly greater reduction in total DBAS scores was found in CBT-I vs waitlist for all 3 versions (63).

Some protocols suggested that participants complete the DBAS as part of the intervention which allows the interventionist to focus attention on strongly held dysfunctional beliefs. As such, the DBAS could be considered both a process and intervention outcome for the trials that included DBAS scoring within the intervention. However, the level of detail provided about the cognitive components of treatment varied, from trials reporting fully outlined sessions to little explanation other than “cognitive restructuring.” Therefore, it was not always clear whether the DBAS was utilized within the intervention as a scored assessment or whether the individual items were used as examples to illustrate dysfunctional beliefs. This difference in trial procedures could result in some participants being exposed to the DBAS pre and post-treatment and others having an added exposure during the intervention. This potential difference could introduce bias that we were not able to fully assess. Future trials should provide more detail about cognitive components of CBT-I and employ placebo behavioral control groups to address potential sources of bias from knowledge of the intervention.

We were surprised to find that the DBAS was used almost universally in trials assessing sleep-related cognitions. One possible reason is that researchers may not see the addition of other sleep-related cognition measures as contributing unique information beyond the DBAS because of the significant moderate to high positive correlation between the DBAS and other measures, i.e. Glasgow Sleep Effort Scale (r = 0.50, p<.0001) (24), the Anxiety and Preoccupation about Sleep Questionnaire (APSQ) (r = .50 –.61, p<.01) (64), and the Sleep Disturbance Questionnaire (SDQ) (r =0.56, p < .0001)(54). Only two included trials employed alternative measures of sleep-related cognition along with the DBAS. Chow et al. (2018) tested an online format of CBT-I and found that those receiving the intervention had significantly higher Internal Sleep Locus (p=.03, indicating greater control over sleep problems) as well as significantly lower levels of Chance Sleep Locus (p < 0.01, indicating less attribution of sleep-problems to external forces) (40). Chow (2018) also found no significant difference between groups in Sleep Self-efficacy at post-intervention (40). Redeker et al. (2017) collected data on the Sleep Disturbance Questionnaire and found intervention group score at post-intervention was not significantly different compared to the attention control group (54). We found a single trial that met all inclusion criteria and used the Anxiety and Preoccupation about Sleep Questionnaire (APSQ) as the primary sleep-cognition instrument without DBAS data (64). This trial could not contribute to the meta-analysis but reported significant differences between intervention and control in APSQ scores pre to post-treatment (p<.01). These results underscore the need to focus future research on sleep-related cognition measures other than the DBAS.

In our meta-analysis we found that the CBT-I interventions reduced dysfunctional beliefs about sleep. The overall moderate to large effect sizes of CBT-I on dysfunctional beliefs were in line with CBT-I effects on insomnia severity (g=.98, 95% CI 0.82,1.15)(65). We also found moderate to large long-term effect sizes (g= −1.04, 95% CI −2.07, −0.02) with follow up time ranging from 3 – 18 months. Few trials contributed data on long-term effects, in part because waitlist control groups were often not followed beyond post-treatment. Our findings are important because improvements in dysfunctional beliefs about sleep among people with insomnia are associated with improvements in sleep quality (66), daytime symptoms (67), depressive symptoms (33), fatigue (41,68) and better maintenance of treatment gains (53,69). How and to what extent changes in dysfunctional beliefs are associated with improvement in insomnia and related symptoms such as mental health warrant future investigation (70). Our data was limited to published trials therefore we were unable to discern differences in DBAS subscale scores. More detailed reporting of subscale scores of the DBAS could help elucidate which elements of dysfunctional beliefs are most sensitive to change.

Despite the various modes of intervention delivery employed, improvement in sleep-related cognitions was consistently observed. For example, fully automated online CBT-I interventions reduced DBAS scores which suggests that self-administered exercises can yield benefits for dysfunctional cognitions without interventionist facilitation (40,43,46,48,50) Duration of treatment and average age of participants did not vary widely across studies. Eleven out of 16 trials delivered CBT-I over 6 weeks and only two trials had an average participant age of less than 40 years which suggests some standardization of the intervention in the field and targeting of middle and older age groups with higher prevalence of insomnia than younger age groups. Other preliminary research suggests individuals with low sleep self-efficacy and high level of dysfunctional beliefs regarding the consequences of poor sleep and helplessness related to insomnia may be particularly good candidates for CBT-I (71).

There were three trials with non-significant effects of CBT-I on DBAS(45,48,54). One trial was a small study exclusively among individuals with heart failure whose experience of insomnia may not be representative of individuals without life threatening medical comorbidity (54). This trial among individuals with heart failure reported statistically significant group × time interaction effects on DBAS in the CBT-I group after controlling for age and comorbidity across multiple time points (baseline, post-treatment, 6 mos) compared to the control group where there was no decrease (54). The remaining two trials included only behavioral components of CBT-I (sleep restriction and stimulus control) and showed no significant effects on DBAS(45,48). Few studies have investigated the effect of different components of CBT-I on dysfunctional beliefs. Eidelman et al. (2016) found that behavioral components alone (sleep restriction and stimulus control) had a significant and sustained improvement in dysfunctional beliefs about sleep, and that cognitive components (whether alone or in combination with behavioral components) had a stronger effect than the behavioral components alone (72). Jannson-Frojmark et al. (2012) found that constructive worry added to the effect of sleep restriction and stimulus control, which resulted in greater reductions in sleep-related worry (73). Further study is needed to confirm the added benefit of the different strategies within the cognitive component of CBT-I in reducing dysfunctional beliefs about sleep and determine whether it is cost-effective when translated into practice.

In conclusion, we found that the DBAS was employed almost universally to assess sleep-related cognitions in randomized trials evaluating CBT-I and that CBT-I was effective in reducing dysfunctional beliefs about sleep with moderate to large effects.

Practice Points.

Cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia is effective with moderate to large overall effects on dysfunctional beliefs about sleep.

Fully automated online cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia can change dysfunctional beliefs about sleep without interventionist facilitation.

Research Agenda.

There is a dearth of research on the impact of cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia on measures of sleep-related cognitions other than Dysfunctional Beliefs and Attitudes Scale. Future studies including more detailed reporting of subscale scores of the DBAS could help elucidate which elements of dysfunctional beliefs or sleep-related cognitions are most sensitive to change.

Future randomized controlled trials can address potential sources of bias from participants’ knowledge of group assignment by utilizing placebo behavioral control groups.

Further study of the cognitive component of cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia could elucidate which specific cognitive strategies provide enough benefit to be cost-effective relative to behavioral components alone.

How and to what extent changes in dysfunctional beliefs are associated with improvement in insomnia and related symptoms such as mental health warrant future investigation.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by a grant from the National Institute on Aging (R01-AG053221, PIs Drs. Vitiello, Von Korff, McCurry).

Glossary

- Cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT)

a structured program to treat insomnia by eliminating common sleep-disruptive behaviors and correcting the beliefs/attitudes that support such practices.

- Dysfunctional beliefs about sleep

faulty beliefs about consequences of poor sleep, uncontrollability and helplessness related to sleep, sleep-promoting behaviors, and the causes of insomnia that are instrumental in exacerbating sleep disturbances

- Stimulus control

CBT strategy is based on the assumption that both the timing (bedtime) and sleep setting (bed/bedroom) are associated with repeated unsuccessful sleep attempts and, over time, become conditioned cues for arousal that perpetuate insomnia. As a result, the goal of this strategy is that of re-associating the bed and bedroom with successful sleep attempts.

- Sleep restriction

goal of this CBT strategy is to reduce nocturnal sleep disturbance primarily by restricting the time allotted for sleep each night so that, eventually, the time spent in bed closely matches the individual’s presumed sleep requirement.

- Relaxation therapy

goal of this CBT strategy is to reduce or eliminate sleep-disruptive physiological (e.g., muscle tension) and/or cognitive (e.g., racing thoughts) arousal.

- Cognitive restructuring

process of challenging expectations for good sleep, ability to tolerate a poor night of sleep, and misattribution of causes and consequences of insomnia

- Automatic Thought Record

goal of this CBT strategy is to explore the situations and intensities of emotions associated with the automatic thoughts about sleep

- Constructive Worry

strategy where time, place and method of worry is clearly prescribed such that the process is not sleep disruptive

- Placebo Behavioral Control

a psychological placebo for behavioral treatment that occupies hours of patient-therapist interaction

- Blinding

concealment of group allocation from one or more individuals involved in a clinical research study

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflicts of Interest Dr. Von Korff was the Principal Investigator of grants to Group Health Research Institute (GHRI) now Kaiser Permanente Washington Health Research Institute, from Pfizer and the Campbell Alliance Group. Dr. Morin has served as a consultant for Abbott, Merck, Pfizer, and Phillips, and received research support from Idorsia. The remaining authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ballesio A, Aquino MRJV., Feige B, Johann AF, Kyle SD, Spiegelhalder K, et al. The effectiveness of behavioural and cognitive behavioural therapies for insomnia on depressive and fatigue symptoms: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Sleep Med Rev [Internet]. 2018. February 1 [cited 2018 Nov 7];37:114–29. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1087079217300266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zachariae R, Lyby MS, Ritterband LM, O’Toole MS. Efficacy of internet-delivered cognitive-behavioral therapy for insomnia – A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Sleep Med Rev [Internet]. 2016. December 1 [cited 2018 Nov 7];30:1–10. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1087079215001483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Irwin MR, Cole JC, Nicassio PM. Comparative meta-analysis of behavioral interventions for insomnia and their efficacy in middle-aged adults and in older adults 55+ years of age. Heal Psychol. 2006;25(1):3–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Geiger-Brown JM, Rogers VE, Liu W, Ludeman EM, Downton KD, Diaz-Abad M. Cognitive behavioral therapy in persons with comorbid insomnia: A meta-analysis. Sleep Med Rev [Internet]. 2015. October 1 [cited 2018 Nov 7];23:54–67. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1087079214001312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cheng SK, Dizon J. Computerised Cognitive Behavioural Therapy for Insomnia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Psychother Psychosom. 2012;81(4):206–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Finan PH, Buenaver LF, Runko VT, Smith MT. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for comorbid insomnia and chronic pain. Sleep Med Clin. 2014;9(2):261–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Belleville G, Cousineau H, Levrier K, St-Pierre-Delorme M-E. Meta-analytic review of the impact of cognitive-behavior therapy for insomnia on concomitant anxiety. Clin Psychol Rev. 2011;31:638–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Okajima I, Komada Y, Inque Y. A meta-analysis on the treatment effectiveness of cognitive behavioral therapy for primary insomnia. Sleep Biol Rhythms. 2011;9(1):24–34. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Taylor DJ, Pruiksma KE. Cognitive and behavioural therapy for insomnia (CBT-I) in psychiatric populations: A systematic review. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2014;26(2):205–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mitchell MD, Gehrman P, Perlis M, Umscheid CA. Comparative effectiveness of cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia: A systematic review. BMC Fam Pract. 2012;25(13):40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dirksen SR, Epstein DR. Efficacy of an insomnia intervention on fatigue, mood and quality of life in breast cancer survivors. J Adv Nurs [Internet]. 2008. March 1 [cited 2018 Nov 11];61(6):664–75. Available from: http://doi.wiley.com/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04560.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Buysse DJ. Effects of a Brief Behavioral Treatment for Late-Life Insomnia : Preliminary Findings. J Clin Sleep Med. 2005;2(4):403–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *13.Morin CM, Bootzin RR, Buysse DJ, Edinger JD, Espie CA, Lichstein K. Psychological and behavioral treatment of insomnia: Update of the recent evidence (1998–2004). Sleep. 2006;29(11):1398–414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Edinger JDD, Fins AII, Sullivan RJJ, Marsh GRR, Dailey DSS, Young M. Comparision of cognitive-behavioral therapy and clonazepam for treating periodic limb movement disorder. Sleep. 1996;19(5):442–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Epstein DR, Sidani S, Bootzin RR, Belyea MJ. Dismantling multicomponent behavioral treatment for insomnia in older adults: A randomized controlled trial. Sleep [Internet]. 2012. June 1 [cited 2018 Nov 11];35(6):797–805. Available from: https://academic.oup.com/sleep/article-lookup/doi/10.5665/sleep.1878 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lichstein KL, Reidel BW, Wilson NM, Lester KW, Aguillard RN, Riedel BW, et al. Relaxation and sleep compression for late-life insomnia: A placebo-controlled trial. J Consult Clin Psychol [Internet]. 2001. [cited 2018 Nov 11];69(2):227–39. Available from: https://www.med.upenn.edu/cbti/assets/user-content/documents/LichsteinandSleepcompressionjccp2001.pdf [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Morin CM, Azrin NH. Behavioral and cognitive treatments of geriatric insomnia. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1988;56:748–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *18.Morin CM. Insomnia: Psychological assessment and management [Internet]. New York:NY: Guilford Press New York; 1993. [cited 2019 Mar 14]. Available from: https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1993-98362-000 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tang NK, Harvey AG. Effects of cognitive arousal and physiological arousal on sleep perception. Sleep. 2004;27(1):69–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harvey AG. A Cognitive Theory and Therapy for Chronic Insomnia. J Cogn Psychother [Internet]. 2005. March [cited 2018 Nov 19];19(1):41–59. Available from: http://connect.springerpub.com/lookup/doi/10.1891/jcop.19.1.41.66332 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Espie CA, Broomfield NM, MacMahon KMA, Macphee LM, Taylor LM. The attention–intention–effort pathway in the development of psychophysiologic insomnia: A theoretical review. Sleep Med Rev [Internet]. 2006. August 1 [cited 2018 Nov 19];10(4):215–45. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1087079206000219?via%3Dihub [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *22.Morin CM, Stone J, Trinkle D, Mercer J, Remsberg S. Dysfunctional beliefs and attitudes about sleep among older adults with and without insomnia complaints. Psychol Aging [Internet] 1993. [cited 2018 Nov 12];8(3):463–7. Available from: http://doi.apa.org/getdoi.cfm?doi=10.1037/0882-7974.8.3.463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vincent N, Sande G, Read C, Giannuzzi T. Sleep Locus of Control: Report on a New Scale. Behav Sleep Med [Internet]. 2004. May [cited 2018 Nov 19];2(2):79–93. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15600226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Broomfield NM, Espie CA. Towards a valid, reliable measure of sleep effort. J Sleep Res [Internet]. 2005. December 1 [cited 2018 Nov 19];14(4):401–7. Available from: http://doi.wiley.com/10.1111/j.1365-2869.2005.00481.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lacks P Behavioral treatment for persistent insomnia. New York: Pergamon Press; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Watts FN, Coyle K, East MP. The contribution of worry to insomnia. Br J Clin Psychol [Internet]. 1994. May 1 [cited 2018 Nov 19];33(2):211–20. Available from: http://doi.wiley.com/10.1111/j.2044-8260.1994.tb01115.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Norell-Clarke A, Jansson-Fröjmark M, Harvey AG, Linton SJ, Lundh L-G. Psychometric Properties of an Insomnia-Specific Measure of Worry: The Anxiety and Preoccupation about Sleep Questionnaire. Cogn Behav Ther [Internet]. 2011. March [cited 2019 Jan 12];40(1):65–76. Available from: http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/16506073.2010.538432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Carney CE, Harris AL, Falco A, Edinger JD. The relation between insomnia symptoms, mood, and rumination about insomnia symptoms. J Clin Sleep Med [Internet]. 2013. June 15 [cited 2018 Nov 19];9(6):567–75. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23772190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *29.Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M, Ghersi D, Liberati A, Petticrew M, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Rev Esp Nutr Humana y Diet [Internet]. 2016. December 1 [cited 2019 Feb 14];20(2):148–60. Available from: https://systematicreviewsjournal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/2046-4053-4-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *30.Higgins JP, Savović J, Page MJ, Sterne JA. A revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomized trials. In: Chandler J; McKenzie J; Boutron I; Welch V, editor. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (online) [Internet]. 2018. Available from: https://sites.google.com/site/riskofbiastool/welcome/rob-2-0-tool/current-version-of-rob-2 [Google Scholar]

- *31.Schwartz DR, Carney CE. Mediators of cognitive-behavioral therapy for insomnia: A review of randomized controlled trials and secondary analysis studies. Clin Psychol Rev [Internet]. 2012. November 1 [cited 2018 Nov 7];32(7):664–75. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0272735812000955 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Carnes D, Homer KE, Miles CL, Pincus T, Underwood M, Rahman A, et al. Effective delivery styles and content for self-management interventions for chronic musculoskeletal pain: a systematic literature review. Clin J Pain. 2012;28(4):344–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sunnhed R, Jansson-Fröjmark M. Are changes in worry associated with treatment response in cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia? Cogn Behav Ther [Internet]. 2014. January 2 [cited 2018 Nov 7];43(1):1–11. Available from: http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/16506073.2013.846399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *34.Espie CA, Inglis SJ, Harvey L, Tessier S. Insomniacs’ attributions: Psychometric properties of the Dysfunctional Beliefs and Attitudes about Sleep Scale and the Sleep Disturbance Questionnaire. J PsychosomRes [Internet]. 2000. February 1 [cited 2019 Mar 16];48(2):141–8. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0022399999000902 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hedges LV Estimation of effect size from a series of independent experiments. Psychol Bull [Internet]. 1982. [cited 2018 Dec 2];92(2):490–9. Available from: http://content.apa.org/journals/bul/92/2/490 [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fritz CO, Morris PE, Richler JJ. Effect size estimates: Current use, calculations, and interpretation. J Exp Psychol Gen [Internet]. 2012. [cited 2019 Mar 29];141(1):2–18. Available from: http://doi.apa.org/getdoi.cfm?doi=10.1037/a0024338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Duval S, Tweedie R. Trim and fill: A simple funnel-plot-based method of testing and adjusting for publication bias in meta-analysis. Biometrics [Internet]. 2000. June [cited 2019 Mar 12];56(2):455–63. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10877304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ [Internet]. 1997. September 13 [cited 2018 Dec 2];315(7109):629–34. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9310563 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Casault L, Savard J, Ivers H, Savard MH. A randomized-controlled trial of an early minimal cognitive-behavioural therapy for insomnia comorbid with cancer. Behav Res Ther [Internet]. 2015. April 1 [cited 2018 Nov 7];67:45–54. Available from: http://ezproxy.lib.umb.edu/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=psyh&AN=2015-12473-006&site=ehost-live [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chow PI, Ingersoll KS, Thorndike FP, Lord HR, Gonder-Frederick L, Morin CM, et al. Cognitive mechanisms of sleep outcomes in a randomized clinical trial of internet-based cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia. Sleep Med [Internet]. 2018. July 1 [cited 2018 Dec 6];47:77–85. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1389945717315915 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sandlund C, Hetta J, Nilsson GH, Ekstedt M, Westman J. Impact of group treatment for insomnia on daytime symptomatology: Analyses from a randomized controlled trial in primary care. Int J Nurs Stud [Internet]. 2018. September 1 [cited 2018 Dec 4];85:126–35. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0020748918301147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Savard J, Ivers H, Savard M-H, Morin CM. Is a video-based cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia as efficacious as a professionally administered treatment in breast cancer? Results of a randomized controlled trial. Sleep [Internet]. 2014. August 1 [cited 2018 Nov 7];37(8):1305–14. Available from: https://academic.oup.com/sleep/article-lookup/doi/10.5665/sleep.3918 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ström L, Pettersson R, Andersson G. Internet-Based Treatment for Insomnia: A Controlled Evaluation. 2004. [cited 2018 Nov 12]; Available from: https://s3.amazonaws.com/academia.edu.documents/44813003/Internet-Based_Treatment_for_Insomnia_A_20160417-28053-51ew3q.pdf?AWSAccessKeyId=AKIAIWOWYYGZ2Y53UL3A&Expires=1542055400&Signature=Mlv1OfyR3dGAbg3XpphcHRm4ay0%253D&response-content-disposition=inline%25 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 44.Taylor DJ, Zimmerman MR, Gardner CE, Williams JM, Grieser EA, Tatum JI, et al. A Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial of the Effects of Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy for Insomnia on Sleep and Daytime Functioning in College Students. Behav Ther [Internet]. 2014. May 1 [cited 2018 Nov 7];45(3):376–89. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0005789413001433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vitiello MV, McCurry SM, Shortreed SM, Balderson BH, Baker LD, Keefe FJ, et al. Cognitive-behavioral treatment for comorbid insomnia and osteoarthritis pain in primary care: The Lifestyles randomized controlled trial. J Am Geriatr Soc [Internet]. 2013. [cited 2019 Jan 11];61(6):947–56. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1111/jgs.12275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ho FY-Y, Chung K-FF, Yeung W-FF, Ng TH-Y, Cheng SK-W. Weekly brief phone support in self-help cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia disorder: Relevance to adherence and efficacy. Behav Res Ther [Internet]. 2014. December 1 [cited 2018 Nov 7];63C(147–156):147–56. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S000579671400165X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Edinger JD, Wohlgemuth WK, Radtke RA, Marsh GR, Quillan RE. Does cognitive-behavioral insomnia therapy alter dysfunctional beliefs about sleep? Sleep. 2001;24(5):591–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Horsch CH, Lancee J, Griffioen-Both F, Spruit S, Fitrianie S, Neerincx MA, et al. Mobile Phone-Delivered Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Insomnia: A Randomized Waitlist Controlled Trial. J Med Internet Res [Internet]. 2017. April 11 [cited 2019 Mar 5];19(4):e70 Available from: http://www.jmir.org/2017/4/e70/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jernelöv S, Lekander M, Blom K, Rydh S, Ljótsson B, Axelsson J, et al. Efficacy of a behavioral self-help treatment with or without therapist guidance for co-morbid and primary insomnia -a randomized controlled trial. BMC Psychiatry [Internet]. 2012. January 22 [cited 2018 Nov 7];12(1):1–13. Available from: http://bmcpsychiatry.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1471-244X-12-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lancee J, Eisma MC, van Straten A, Kamphuis JH. Sleep-related safety behaviors and dysfunctional beliefs mediate the efficacy of online CBT for insomnia: A randomized controlled trial. Cogn Behav Ther [Internet]. 2015. September;44(5):406–22. Available from: http://ezproxy.lib.umb.edu/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=psyh&AN=2015-44381-005&site=ehost-live [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lovato N, Lack L, Wright H, Kennaway DJ. Evaluation of a brief treatment program of cognitive behavior therapy for insomnia in older adults. Sleep. 2014. January 15;37(1):117–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mimeault V, Morin CM. Self-help treatment for insomnia: Bibliotherapy with and without professional guidance. J Consult Clin Psychol [Internet]. 1999. [cited 2018 Nov 12];67(4):511–9. Available from: http://doi.apa.org/getdoi.cfm?doi=10.1037/0022-006X.67.4.511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *53.Morin CM, Blais F, Savard J. Are changes in beliefs and attitudes about sleep related to sleep improvements in the treatment of insomnia? Behav Res Ther [Internet]. 2002. July 1 [cited 2018 Nov 7];40(7):741–52. Available from: http://ezproxy.lib.umb.edu/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=psyh&AN=2002-01977-001&site=ehost-live [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Redeker NS, Conley S, Anderson G, Cline J, Andrews L, Mohsenin V, et al. Effects of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Insomnia on Sleep-Related Cognitions Among Patients With Stable Heart Failure. Behav Sleep Med [Internet]. 2017. July 26 [cited 2018 Dec 4];17(3):1–13. Available from: http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=hbsm20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Association AP. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-5®). American Psychiatric Pub; 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Edinger JD, Bonnet MH, Bootzin RR, Doghramji K, Dorsey CM, Espie CA, et al. Derivation of Research Diagnostic Criteria for insomnia: Report of an American Academy of Sleep Medicine Work Group. Sleep [Internet]. 2004. December 15 [cited 2019 Feb 21];27(8):1567–96. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15683149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Norell-Clarke A, Tillfors M, Jansson-Fröjmark M, Holländare F, Engström I. How does cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia work? An investigation of cognitive processes and time in bed as outcomes and mediators in a sample with insomnia and depressive symptomatology [Internet] Vol. 10, International Journal of Cognitive Therapy. Norell-Clarke, Annika, Centre for Research on Child and Adolescent Mental Health, Karlstad University, SE-651 88, Karlstad, Sweden: Guilford Publications; 2017. December [cited 2018 Dec 4]. Available from: http://ezproxy.lib.umb.edu/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=psyh&AN=2018-00268-003&site=ehost-live [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bastien CH, Vallières A, Morin CM, Vallieres A, Morin CM. Validation of the Insomnia Severity Index as an outcome measure for insomnia research. Sleep Med [Internet]. 2001. July 1 [cited 2019 May 16];2(4):297–307. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1389945700000654 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Krupp LB, LaRocca NG, Muir-Nash J, Steinberg AD. The Fatigue Severity Scale. Arch Neurol. 1989;46:1121–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gonder-Frederick L, Bailey E, Morin C, Saylor D, Ritterband L, Thorndike F. Development and Perceived Utility and Impact of an Internet Intervention for Insomnia. E-Journal Appl Psychol [Internet]. 2013. [cited 2019 Mar 14];4(2):32–42. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20953264 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *61.Morin CM, Espie CA. Insomnia: A Clinical Guide to Assessment and Treatment (Google eBook) [Internet]. New York: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 2003. [cited 2019 Mar 14]. 190 p. Available from: https://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=nmfjBwAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PA1&ots=Fw3KUB2lXP&sig=LLd6Db_C9SJmFycCwF8_GldU7ho#v=onepage&q&f=false [Google Scholar]

- *62.Morin CM, Vallieres A, Ivers H, Bouchard S, Bastien CH. Dysfunctional Beliefs and Attitudes about Sleep (DBAS): Validation of a briefer version (DBAS-16). . Vol. 26, Sleep. 2003. p. A294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Chung KF, Ho FYY, Yeung WF. Psychometric comparison of the full and abbreviated versions of the dysfunctional beliefs and attitudes about sleep scale. J Clin Sleep Med [Internet]. 2016. June 15 [cited 2019 Aug 7];12(6):821–8. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26857054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Roetger A, Maercker A, Birrer E, Heim E, Lorenz N. Randomized Controlled Trial to Test the Efficacy of an Unguided Online Intervention with Automated Feedback for the Treatment of Insomnia. Behav Cogn Psychother [Internet]. 2018. [cited 2018 Dec 4];1–16. Available from: https://www.cambridge.org/core/services/aop-cambridge-core/content/view/2A676F7D05F20CCE9B356882C2C98DC1/S1352465818000486a.pdf/randomized_controlled_trial_to_test_the_efficacy_of_an_unguided_online_intervention_with_automated_feedback_for_the_treatment_o [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.van Straten A, van der Zweerde T, Kleiboer A, Cuijpers P, Morin CM, Lancee J. Cognitive and behavioral therapies in the treatment of insomnia: A meta-analysis [Internet]. Vol. 38, Sleep Medicine Reviews. 2018. [cited 2018 Dec 5]. p. 3–16. Available from: 10.1016/j.smrv.2017.02.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Carney CE, Edinger JD. Identifying critical beliefs about sleep in primary insomnia. Sleep. 2006;29(4):444–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Jansson-Fröjmark M, Linton SJ. The role of sleep-related beliefs to improvement in early cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia. Cogn Behav Ther [Internet]. 2008. March;37(1):5–13. Available from: http://ezproxy.lib.umb.edu/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=psyh&AN=2008-04211-002&site=ehost-live [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Fairholme CP, Manber R. Safety behaviors and sleep effort predict sleep disturbance and fatigue in an outpatient sample with anxiety and depressive disorders. J Psychosom Res [Internet]. 2014. March 1 [cited 2019 Mar 16];76(3):233–6. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0022399914000038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Edinger JD, Wohlgemuth WK. Psychometric comparisons of the standard and abbreviated DBAS-10 versions of the dysfunctional beliefs and attitudes about sleep questionnaire. Sleep Med [Internet]. 2003/November/01 2001;2(6):493–500. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=14592264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Sunnhed R, Jansson-Fröjmark M. Cognitive Arousal, Unhelpful Beliefs and Maladaptive Sleep Behaviors as Mediators in Cognitive Behavior Therapy for Insomnia: A Quasi-Experimental Study. Cognit Ther Res [Internet]. 2015. December 5 [cited 2019 Aug 8];39(6):841–52. Available from: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s10608-015-9698-0 [Google Scholar]

- 71.Montserrat Sánchez-Ortuño M, Edinger JD. A penny for your thoughts: Patterns of sleep-related beliefs, insomnia symptoms and treatment outcome. Behav Res Ther [Internet]. 2010. February 1 [cited 2018 Nov 6];48(2):125–33. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0005796709002393#bib10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Eidelman P, Talbot L, Ivers H, Bélanger L, Morin CM, Harvey AG. Change in dysfunctional beliefs about sleep in behavior therapy, cognitive therapy, and cognitive-behavioral therapy for insomnia. Behav Ther [Internet]. 2016. January 1 [cited 2018 Nov 7];47(1):102–15. Available from: http://ezproxy.lib.umb.edu/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=psyh&AN=2016-00569-010&site=ehost-live [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Jansson-Fröjmark M, Lind M, Sunnhed R. Don’t worry, be constructive: A randomized controlled feasibility study comparing behaviour therapy singly and combined with constructive worry for insomnia. Br J Clin Psychol [Internet]. 2012. June 1 [cited 2018 Dec 6];51(2):142–57. Available from: http://doi.wiley.com/10.1111/j.2044-8260.2011.02018.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]