Abstract

Compared with younger adults, older adults tend to favor positive information more than negative information in their attention and memory. This “positivity effect” has been observed in various paradigms, but at which stage it impacts cognitive processing and how it influences processing other stimuli appearing around the same time remains unclear. Across four experiments, we examined how older adults prioritize emotional information in early attention. Both younger and older adults demonstrated emotion-induced blindness - identifying targets in a rapid serial display of pictures with less accuracy after emotional compared to neutral distractors-but older adults demonstrated a positivity bias at this early attentional level. Moreover, the bias toward positive but not negative information in older adults was reduced when they had a working memory load. These results suggest that a selective bias toward positive, but not negative, information occurs early in visual processing, and the bias relies on cognitive control resources.

When it comes to the emotional tinting of everyday stimuli and events, it appears that older adults view the world through rose-colored glasses whereas younger adults have a darker view (Mather & Carstensen, 2005). Relative to younger adults, older adults tend to attend to and remember positive more than negative information, leading to an age-by-valence interaction known as the “positivity effect” (Charles, Mather, & Carstensen, 2003; Mather & Carstensen, 2003, 2005).

Socioemotional selectivity theory posits that the age-related positivity effect results from age differences in time perspective, such that older adults prioritize processing positive information because they view their time left as limited and so want to optimize present experience (Barber, Opitz, Martins, Sakaki, & Mather, 2016; Carstensen, 2006). The notion that the positivity effect is due to age-related shifts in goals leads to the prediction that older adults’ positivity bias depends on cognitive control processes that support goal implementation (Knight et al., 2007; Mather & Knight, 2005; but see Cacioppo, Berntson, Bechara, Tranel, & Hawkley, 2011). Older adults’ cognitive control abilities are generally worse than younger adults and also require increased prefrontal cortex activation to achieve cognitive control performance similar to younger adults (e.g., Paxton, Barch, Racine, & Braver, 2008). Nevertheless, evidence suggests that the positivity effect is dependent on such cognitive control resources: for example, when Mather and Knight had participants recall images, compared to younger adults, older adults tended to remember positive more than negative images, but showed no such preference when they completed a cognitively demanding task while encoding the images (Mather & Knight, 2005). It is thus proposed that older adults employ a “chronic” emotion regulation strategy that prioritizes positive information, deprioritizes negative information, and requires cognitive control resources (Knight et al., 2007; Mather & Knight, 2005). In this model, younger adults can shift into this strategy when needed, whereas older adults tend to default to this emotion regulation strategy unless their cognitive control processes are taxed. One interesting implication of this model of chronically active emotion regulation processes is that positivity/anti-negativity biases should influence even early phases of attention - that is, as soon as the valence of a stimulus is detected, that valence should influence its processing.

In general, one of the most dramatic things that emotional stimuli can do is to interfere with processing other stimuli competing for attention. This power of emotional stimuli is exemplified in the ‘emotion-induced blindness’ paradigm in which participants show impairment in identifying the direction that an image in a rapid stream of pictures is rotated if there is an emotional picture appearing shortly before the rotated picture (e.g., Most, Chun, Widders, & Zald, 2005). Emotion-induced blindness occurs after both negative and positive stimuli in younger adults, and is believed to reflect an early, spatiotemporal competition between representations of emotional distractors and subsequent targets (Wang, Kennedy, & Most, 2012). In the current series of experiments, we examined whether there are age differences in emotion- induced blindness to examine the early attentional consequences of emotional distractors in younger and older adults. Such age differences would suggest that older adults utilize an emotion regulation strategy that occurs at an early attentional level - illuminating how pervasively older adults employ such mechanisms, while also gaining insight into the dramatic way that older adults may experience the environment differently than younger adults.

Previous research studies that have examined how quickly an age-related positivity effect emerges present mixed findings. In terms of attentional biases when viewing two faces next to one another (one neutral and one emotional), two studies found that the age-by-valence positivity effect pattern does not emerge until at least 500 or 1000 ms after onset of the faces (Isaacowitz, Allard, Murphy, & Schlangel, 2009; Orgeta, 2011), whereas another study found that older adults showed a stronger happy face bias than younger adults at 100 ms but younger adults showed a stronger angry face bias at 500 ms (Gronchi et al., 2018). Startle findings mirror positivity biases in older adults to demonstrate rapid age-by-valence differences in the impact of task-irrelevant emotional stimuli: when participants were startled within seconds after seeing an emotional stimulus, younger adults were most startled after negative stimuli, but older adults were most startled after positive stimuli (Feng, Courtney, Mather, Dawson, & Davison, 2011; Le Duc, Fournier, & Hébert, 2016; Mather, 2016), though the time course of the startle effects remain unknown. Nevertheless, these previous studies do not indicate whether there are age differences in how emotional stimuli interfere with processing other neutral stimuli in early stages of attention. Some other studies have examined age differences in emotional interference with rapidly displayed stimuli (Mickley Steinmetz, Muscatell, & Kensinger, 2010; Thomas & Hasher, 2006). On each trial in Thomas and Hasher’s (2006) design, a positive, negative or neutral word appeared between two digits for 200 ms followed by a blank screen during which participants had to respond whether both digits were odd/even or not. Patterns consistent with an age-related positivity effect were seen in both reaction times and incidental memory for the words, but as responding was self-paced and stimuli were not masked, effects may have reflected processing after the initial 200 ms display time.

Mickley Steinmetz and colleagues (2010) examined age-by-valence interactions by employing a rapid serial visual presentation, “attentional blink” design. Unlike emotion-induced blindness, the attentional blink usually requires participants to report two non-emotional task-relevant targets in a rapid stream, with the common finding that participants can report the first target well but at the expense of the second target when it is presented soon after the first (e.g., Chun & Potter, 1995; Raymond, Shapiro, & Arnell, 1992). When using an emotional version of the attentional blink paradigm, participants often have an even harder time reporting the second task-relevant target when the first is emotional compared to neutral (e.g., Schwabe et al., 2011; Schwabe & Wolf, 2010). The emotional version of the attentional blink is thus phenomenally similar to emotion-induced blindness, such that an emotional attention-grabbing stimulus impairs the detection of a second item presented after it (although the phenomena differ because of the task-relevance of the first target; see Wang et al., 2012 for more discussion on this point). By employing an emotional version of the attentional blink, Mickley Steinmetz et al. sought to understand how emotional words may quickly impact attention for younger and older adults differently. In their study, participants were instructed to report two words presented in blue font amongst otherwise white-font words in a rapid stream. The first blue-colored word was either a neutral, negative, or positive word, and the second blue-colored word was always a neutral word that followed soon after the first target word. The researchers found no evidence of a positivity effect, however also failed to demonstrate the typical attentional blink pattern altogether. One interpretation of their results is that the design critically deviated from most attentional blink studies because of the oddball nature of the two targets compared to all other stimuli presented, such that there was no appropriate mask after the target words were presented. Accordingly, due to no appropriate mask of the target words, participants tended to report the second target more than the first target - exactly opposite of typical patterns in the attentional blink - and the effects of emotion were seemingly confounded with recency effects and representational competition between the two targets. The authors also collapsed the data across several presentation lags between the first and second target words - making the temporal impact of the emotional words of their results difficult to interpret. Thus, while the question intended by their experiment speaks to the question at hand, their design limits the conclusions that can drawn from their results.

In the current series of experiments, we employed emotion-induced blindness tasks to examine the early attentional consequences of emotional distractors in younger and older adults. We hypothesized that if they have chronically active emotional regulation goals, older adults would not be as distracted by negative images as younger adults in an emotion-induced blindness task, as even in early attention older adults would be engaging cognitive resources to diminish the impact of these negative stimuli. We found that, consistent with our predictions, age-by-valence interactions occurred within the rapid perceptual context of these tasks. In addition to providing novel information about how emotional stimuli interfere with attention in older adults, the results have important implications for understanding the mechanisms of the positivity effect.

Experiment 1

Previous research demonstrates disruption in early attention from emotionally negative distractors in younger adults (Most et al., 2005; Wang et al., 2012). The positivity effect - whereby older adults prioritize positive information and deprioritize negative information compared to younger adults - has been demonstrated across mostly slower paced attention and memory tasks (see Reed, Chan, & Mikels, 2014 for review), such as tasks requiring participants to recall images they previously saw (Charles et al., 2003), or tasks requiring participants to respond to stimuli presented in the same or different location as emotional or neutral images (Mather & Carstensen, 2003). In Experiment 1, we tested whether a greater negativity bias would manifest for younger adults compared to older adults in early attention from rapidly presented emotionally negative stimuli, due to age-related differences in the priority of negative stimuli.

Method

Participants.

Twenty-two younger adults (ages 18–26; M = 20.32 years old, 95% CI [19.52, 21.12]; 15 female, 7 male) and twenty older adults1 (ages 63–80; M = 70.55 years old, 95% CI [67.96, 73.14]; 7 female, 13 male) participated in the experiment. Younger adult participants were recruited through the USC psychology participant pool, and older adult participants were recruited from the community through the USC Healthy Minds Database. Sample size was determined based on the typical sample size of previous emotion-induced blindness experiments with younger adults (e.g., Most et al., 2005). Since chance performance was at 50%, we excluded participants with lower than 55% accuracy on the overall task. Due to poor performance accuracy on the picture rotation task (< 55% overall accuracy), we excluded one older adult participant’s data, and due to a computer error excluded one younger adult participant’s data. All participants provided written informed consent, and the experiment was approved by the USC Human Subjects Institutional Review Board. Participants were compensated at a rate of $15 per hour, and the entire study session took about ninety minutes.

Materials and Procedure.

We programmed the experiment using the Psychophysics Toolbox for Matlab (Brainard, 1997; Pelli, 1997) and ran sessions in a dimly lit room with the LCD monitor refresh rate set at 60 Hz. Participants’ head position was not fixed.

The experiment consisted of four blocks of 72 trials. On every trial, participants saw a rapid serial visual presentation (RSVP) that contained a distractor image, a target image, and 15 filler images. Images were colored, 320 × 240 pixel photographs that were normalized for luminance using the SHINE Toolbox (Willenbockel et al., 2010).

Distractor images were emotionally negative, emotionally neutral, or “baseline” images. 56 negative and 56 neutral images were gathered from the International Affective Picture System (IAPS; Lang, Bradley, & Cuthbert, 2008). Images were selected based on the valence and arousal ratings norms provided by IAPS (valence: negative = 1 to positive = 9; arousal: 1 = low arousal to 9 = high arousal). The negative image set had more negatively valenced ratings (M = 2.57, 95% CI [2.38, 2.77]) and more arousing ratings (M = 6.41, 95% CI [6.26, 6.55]), than neutral images (valence: M = 5.47, 95% CI [5.29, 5.65]; arousal: M = 3.44, 95% CI [3.31, 3.57]), ts ≥ 22.00, ps < 0.001. Baseline distractor images were selected from the same set of images as the filler images (see below).

Two hundred and fifty-two filler images depicted landscape and architectural scenes and appeared upright. Target images came from a bank of 64 landscape or architectural scene images and were rotated 90 degrees to the left and 90 degrees to the right (128 images total). Target and filler images were the same as those used in previous emotion-induced blindness experiments (e.g., Kennedy & Most, 2015; Most et al., 2005).

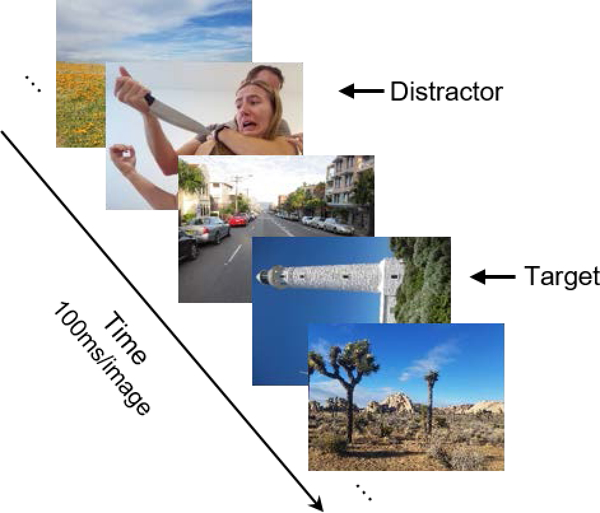

Depending on the trial, the distractor appeared at serial position 3, 4, 5, 6, or 7. Targets were always presented after the distractor - either as the second (lag-2) or fourth (lag-4) image after the distractor in the RSVP stream. Trials began with images presented one at a time in an RSVP stream, centered on the screen against a gray background. Each image in the RSVP stream was presented for 100 ms, and replaced immediately with the next image in the RSVP (see Figure 1). Participants were instructed to view the RSVP stream on every trial and to look out for the direction of the one rotated picture. After all 17 images in the RSVP were presented, participants saw a blank screen, which signaled for participants to make their response by indicating the direction that the target was rotated by pressing the appropriate arrow key on the keyboard (left arrow or right arrow) with their preferred hand. If participants were correct, they heard a “ding” noise in the headphones and heard nothing if they were incorrect. Participants had no time restriction to make their response. The next trial started 500 ms after participants made their response.

Figure 1.

Illustration of a partial lag-2 trial. Participants were instructed to indicate if the one rotated image in the RSVP stream was rotated 90° clockwise or counterclockwise. Photographs presented in this figure are original photographs that are similar in content to those used in the experiments. The distractor photograph presented here depicts the first author, with permission. See text for details.

Participants completed three questionnaires to assess individual differences: an in-house demographics questionnaire, a memory task from the CERAD (Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease; Welsh et al., 1994), and the WTAR (Wechsler Test of Adult Reading; Holdnack, 2001). In the CERAD memory task, participants were shown ten words presented in the same order three times and were asked to immediately recall as many words that they could remember. After about a ten-minute delay, participants were asked to again recall the list of words presented, and then were asked to identify which of twenty words were originally presented. Performance on the CERAD was calculated as hits minus false alarms on the delay recall and recognition tests, and scores were interpreted as an indicator of cognitive status. Heart rate, respiration, and pupil size were also collected throughout the experiment, but psychophysiology data are not reported here.

At the beginning of the session, participants were shown examples of the emotional and neutral images to ensure that they were comfortable viewing them, and then completed the consent form and questionnaires. Participants then started the rotation detection task, with a 6-trial practice session. During the practice session, the rate of the RSVP gradually sped up from 200ms to 100ms in order for participants to get used to the task. Once participants completed the rotation detection task, they completed additional tasks for another experiment, which are not reported here, and were debriefed about the goals of the study.

Within-subject confidence intervals (Cousineau, 2005; Loftus & Masson, 1994) for emotion-induced blindness results were calculated for both age groups separately. See Table 1 for means and confidence intervals for the emotion-induced blindness results in all experiments.

Table 1.

Means and 95% within-subject confidence intervals of emotion-induced blindness results for Experiments 1–4, separated by each age group, lag, and distractor condition. NL = no load, HL = high load.

| Younger Adults | Older Adults | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negative Distractor Trials | Positive Distractor Trials | Neutral Distractor Trials | Baseline Distractor Trials | Negative Distractor Trials | Positive Distractor Trials | Neutral Distractor Trials | Baseline Distractor Trials | |||||||||

| M(%) | 95% CIs(%) | M(%) | 95% CIs(%) | M(%) | 95% CIs(%) | M(%) | 95% CIs(%) | M(%) | 95% CIs(%) | M(%) | 95% CIs(%) | M(%) | 95% CIs(%) | M(%) | 95% CIs(%) | |

| Exp 1 Lag-2 | 75.89 | [73.31, 78.47] | - | - | 82.54 | [80.59, 84.49] | 89.58 | [87.09, 92.08] | 73.68 | [71.10, 76.27] | - | - | 73.14 | [70.94, 75.33] | 81.36 | [79.07, 83.65] |

| Lag-4 | 81.94 | [79.59, 84.30] | - | - | 87.60 | [85.43, 89.77] | 88.00 | [86.29, 89.70] | 78.51 | [76.86, 80.16] | - | - | 80.48 | [78.72, 82.25] | 80.70 | [78.71, 82.69] |

| Exp 2 Lag-2 | 73.50 | [69.90, 77.09] | 70.49 | [67.32, 73.65] | 84.72 | [82.14, 87.30] | 89.35 | [87.31, 91.40] | 78.40 | [74.05, 82.74] | 71.91 | [68.49, 75.34] | 78.70 | [76.26, 81.15] | 81.48 | [78.37, 84.60] |

| Lag-5 | 87.38 | [85.21, 89.56] | 86.34 | [84.08, 88.61] | 90.74 | [88.33, 93.16] | 91.78 | [89.58, 93.98] | 77.31 | [74.23, 80.39] | 77.16 | [74.46, 79.86] | 81.02 | [78.04, 84.00] | 84.72 | [82.08, 87.37] |

| Exp 3 Lag-1 | 67.20 | [62.97, 71.44] | 73.48 | [69.66, 77.29] | 78.14 | [74.86, 81.41] | 86.02 | [83.20, 88.84] | 76.73 | [73.35, 80.11] | 74.92 | [71.15, 78.68] | 73.10 | [69.37, 76.83] | 88.78 | [86.19, 91.37] |

| Lag-2 | 68.46 | [64.73, 72.19] | 75.45 | [71.34, 79.55] | 82.62 | [79.82, 85.41] | 84.23 | [81.20, 87.26] | 75.58 | [72.40, 78.75] | 72.77 | [69.32, 76.23] | 81.52 | [78.09, 84.94] | 88.12 | [85.46, 90.77] |

| Lag-3 | 79.75 | [76.14, 83.35] | 79.39 | [76.25, 82.53] | 86.56 | [83.81, 89.31] | 84.77 | [81.92, 87.61] | 78.38 | [75.19, 81.57] | 77.72 | [74.50, 80.94] | 87.79 | [85.12, 90.46] | 89.44 | [86.87, 92.01] |

| Lag-4 | 83.51 | [80.49, 86.53] | 83.69 | [80.91, 86.48] | 88.53 | [85.98, 91.08] | 88.89 | [86.35, 91.43] | 84.65 | [81.94, 87.37] | 82.51 | [79.48, 85.54] | 88.94 | [86.41, 91.47] | 89.44 | [86.96, 91.92] |

| Lag-5 | 85.30 | [82.56, 88.05] | 89.61 | [87.20, 92.01] | 87.63 | [85.04, 90.23] | 89.96 | [87.32, 92.61] | 85.15 | [82.44, 87.86] | 86.80 | [84.38, 89.21] | 87.95 | [85.24, 90.67] | 87.95 | [85.04, 90.87] |

| Lag-6 | 87.81 | [84.84, 90.78] | 85.84 | [82.97, 88.72] | 88.53 | [86.10, 90.96] | 88.71 | [86.10, 91.32] | 87.13 | [84.16, 90.10] | 86.63 | [83.92, 89.34] | 88.94 | [86.56, 91.32] | 88.12 | [85.57, 90.67] |

| Lag-7 | 86.56 | [83.68, 89.44] | 87.10 | [84.51, 89.68] | 88.53 | [85.52, 91.54] | 86.74 | [84.40, 89.08] | 86.96 | [84.16, 89.76] | 88.12 | [85.43, 90.81] | 87.13 | [84.85, 89.41] | 89.60 | [87.19, 92.01] |

| Lag-8 | 86.38 | [83.82, 88.94] | 86.92 | [84.35, 89.48] | 87.81 | [85.06, 90.56] | 87.10 | [84.32, 89.87] | 86.14 | [83.40, 88.87] | 85.31 | [82.51, 88.12] | 86.63 | [83.72, 89.54] | 88.78 | [86.51, 91.05] |

| Exp 4 Lag-2, NL | 79.17 | [74.82, 83.52] | 76.85 | [72.91, 80.79] | 89.35 | [86.16, 92.55] | 90.28 | [87.29, 93.27] | 82.37 | [78.68, 86.05] | 75.00 | [70.81, 79.19] | 89.06 | [86.32, 91.80] | 89.96 | [87.46, 92.45] |

| Lag-2, HL | 79.17 | [75.32, 83.02] | 80.09 | [76.39, 83.80] | 89.35 | [86.68, 92.03] | 90.28 | [87.61, 92.94] | 82.14 | [78.16, 86.12] | 80.36 | [77.09, 83.62] | 87.72 | [85.00, 90.45] | 91.52 | [89.59, 93.44] |

| Lag-5, NL | 89.58 | [86.46, 92.71] | 95.60 | [93.73, 97.47] | 92.13 | [89.09, 95.17] | 92.59 | [89.84, 95.35] | 90.18 | [87.21, 93.15] | 89.51 | [86.70, 92.31] | 89.96 | [87.51, 92.40] | 90.18 | [87.28, 93.08] |

| Lag-5, HL | 90.51 | [88.06, 92.96] | 90.74 | [88.66, 92.82] | 93.98 | [91.39, 96.58] | 92.59 | [90.57, 94.61] | 87.05 | [83.82, 90.29] | 88.17 | [85.71, 90.63] | 90.40 | [87.15, 93.66] | 93.97 | [91.27, 96.68] |

| Lag-7, NL | 94.91 | [93.16, 96.65] | 91.20 | [87.76, 94.65] | 95.37 | [93.35, 97.39] | 94.21 | [91.97, 96.45] | 86.61 | [83.31, 89.90] | 91.29 | [88.70, 93.89] | 93.08 | [90.62, 95.55] | 90.40 | [87.58, 93.23] |

| Lag-7, HL | 90.74 | [87.90, 93.59] | 92.82 | [90.56, 95.09] | 92.82 | [90.51, 95.14] | 91.67 | [88.87, 94.47] | 90.18 | [87.78, 92.58] | 87.28 | [84.14, 90.42] | 91.52 | [88.78, 94.26] | 91.07 | [88.54, 93.60] |

Results

Questionnaires

Younger and older adults demonstrated no difference in their vocabulary as measured by the WTAR, or recognition memory on the CERAD task (see Table 2). There were age differences in recall memory on the CERAD task, such that older adults tended to recall fewer words than younger adults. However, responses on none of these measures correlated with negative distraction compared to neutral distraction at lag 2, which was our main comparison for the emotion-induced blindness effect.2

Table 2.

Means and 95% within-subject confidence intervals of questionnaire responses from Experiments 1 and 2, separated and compared between age groups.

| Younger Adults | Older Adults | Younger Adults vs. Older Adults | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | 95%> CIs | M | 95%> CIs | t-test | |

| Exp 1 WTAR | 41.86 | [39.75, 43.96] | 43.84 | [41.44, 46.25] | t (38) = 1.31, p = .199, d = 0.414 |

| CERAD recall | 9.05 | [8.68, 9.41] | 7.05 | [5.92, 8.18] | t (38) = 3.53, p = .002, d = 1.116 |

| CERAD recognition | 9.95 | [9.85, 10.05] | 9.52 | [9.03, 10.02] | t (38) = 1.78, p = .090, d = 0.565 |

| Exp 2 WTAR | 42.75 | [41.14, 44.36] | 44.44 | [42.12, 46.77] | t (40) = 1.29, p = .203, d = 0.403 |

| CERAD recall | 8.42 | [7.59, 9.24] | 7.44 | [6.51, 8.38] | t (40) = 1.62, p = .113, d = 0.505 |

| CERAD recognition | 9.63 | [9.35, 9.90] | 9.56 | [9.21, 9.91] | t (40) = 0.33, p = .742, d = 0.103 |

| DASS total | 10.17 | [6.71, 13.62] | 8.47 | [5.58, 11.36] | t (39) = 0.74, p = .464, d = 0.234 |

| DAS-depression | 3.54 | [1.73, 5.35] | 1.35 | [0.46, 2.24] | t (39) = 1.99, p = .054, d = 0.630 |

| DAS-anxiety | 1.92 | [0.94, 2.89] | 2.29 | [1.35, 3.23] | t (39) = 0.56, p = .578, d = 0.178 |

| DAS-stress | 4.71 | [3.26, 6.16] | 4.82 | [3.04, 6.61] | t (39) = 0.11, p = .917, d = 0.033 |

Rotation Detection Task

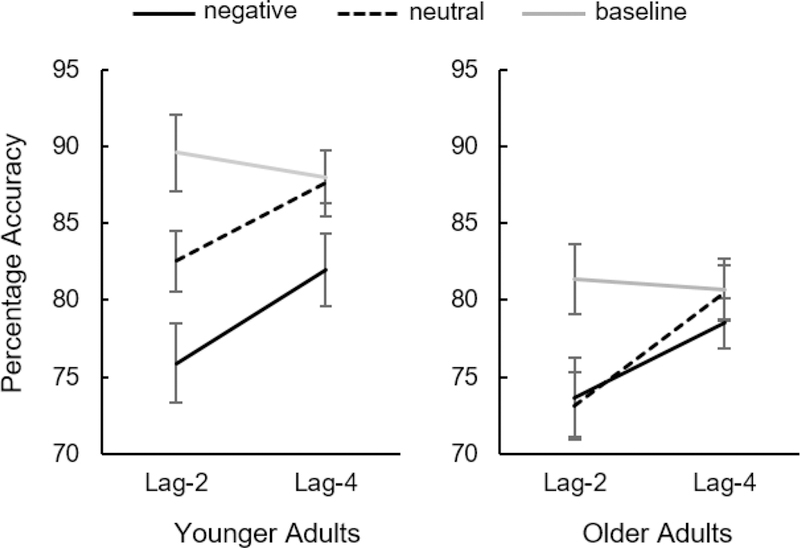

A 3 (distractor type: negative vs neutral vs baseline) x 2 (lag: 2 vs 4) x 2 (age group: older adults vs younger adults) mixed ANOVA revealed a significant main effect of age group, F(1,38) = 8.67, p = .006, ηp2 = 0.186, such that older adults’ overall target performance accuracy was worse than that of younger adults (Figure 2). There was also a significant main effect of distractor type, F(2,76) = 31.45, p < .001, ηp2= 0.453; overall, target performance was worse after negative distractors and best after baseline distractors. The main effect of lag was also significant, F(1,38) = 90.34, p < .001, ηp2 = 0.704 - overall performance was better on lag-4 trials than lag-2 trials. There was a significant distractor type x lag interaction, F(2,76) = 12.41, p < .001, ηp2 = 0.25, with generally better performance at lag-4 than lag-2. The distractor type x lag x age group interaction was not significant, F(2,76) = 0.60, p = .551, ηp2 = 0.016, nor was the lag x age group interaction, F(1,38) = 0.81, p = .374, ηp 2 = 0.021 - however, there was a significant distractor type x age group interaction, F(2,76) = 5.17, p = .008, ηp2 = 0.120, indicating the impact of negative distractors compared to neutral and baseline distractors differed between younger and older adults.

Figure 2.

Emotion-induced blindness results from Experiment 1. Error bars represent within-subject, 95% confidence intervals.

Younger adults demonstrated the typical emotion-induced blindness pattern, with significantly worse performance for negative compared to neutral trials at lag 2, t(20) = 4.50, p < .001, dz = 0.982, and at lag 4, t(20) = 3.12, p = .005, dz = 0.681. Performance in baseline distractor trials at lag 2 was better than performance in both lag-2 negative distractor trials t(20) = 5.96, p < .001, dz = 1.300, and neutral distractor trials, t(20) = 3.90, p = .001, dz = 0.852. At lag 4, performance on baseline trials was still better than on negative trials, t(20) = 3.46, p =.002, dz = 0.775, but there was no difference in performance accuracy between baseline trials and neutral distractor trials at lag 4, t(20) = 0.29, p = .778, dz = 0.062.

Older adults demonstrated no difference in performance accuracy between negative and neutral distractors at lag 2, t(18) = .30, p = .771, dz = 0.067, and no difference in performance at lag 4, t(18) = 1.33, p = .202, dz = 0.304. At lag 2, performance was significantly better on baseline distractor trials compared to both negative, t(18) = 3.72, p = .002, dz = 0.853, and neutral, t(18) = 4.54, p < .001, dz = 1.041, trials. At lag 4, there was no difference between baseline distractor trials and negative, t(18) = 1.61, p = .126, dz = 0.368, nor neutral, t(18) = 0.15, p = .884, dz = 0.034, trials.

Discussion

Younger adults demonstrated typical emotion-induced blindness, with worse performance on negative trials than on neutral trials. Older adults overall were less accurate than younger adults and did not demonstrate emotion-induced blindness, as they were no more impaired on negative trials than on neutral trials at either lag. The emotion-induced blindness pattern did not correlate with differences in vocabulary measured by the WTAR or cognitive ability measured by the CERAD memory tests. Altogether, these results suggest that older adults do not experience negative emotional information the same way in early attention as do younger adults. In particular, the age-by-valence interaction indicates that a positivity effect occurs within a few hundred milliseconds of emotional images appearing, since older adults were less impacted by negative stimuli than younger adults were. However, an alternative explanation may be that older adults simply do not inhibit attention after any type of emotionally impactful images.

Experiment 2

It is well-documented that attentional inhibition of task-irrelevant information is decreased in older adults compared to younger adults (Hasher & Zacks, 1988; Lustig, Hasher, & Zacks, 2007). The Arousal Biased Competition (ABC) theory - which may predict the performance patterns in emotion-induced blindness - suggests that emotion prioritizes attention toward important information and simultaneously inhibits attention toward less important information (Mather, Clewett, Sakaki, & Harley, 2016; Mather & Sutherland, 2011). If older adults’ attentional system simply fails to inhibit information, attention-grabbing emotional stimuli - regardless of valence - may not inhibit subsequently presented targets in the emotion- induced blindness task for older adults in the same way that they do for younger adults. That is, older adults may not exhibit emotion-induced blindness simply because they do not inhibit information presented after emotionally powerful distractors.

In Experiment 2, to assess the possible role of inhibition in our results, we introduced positive stimuli as distractors. While the majority of emotion-induced blindness studies employ only negative emotional distractors, previous literature has demonstrated that younger adults experience emotion-induced blindness from both positive and negative distractors (e.g., Kennedy, Newman, & Most, 2018; Most, Smith, Cooter, Levy, & Zald, 2007). If older adults’ lack of emotion-induced blindness in Experiment 1 was due to failure to stimulate inhibition of subsequent stimuli, we should observe no emotion-induced blindness after either negative distractors or positive distractors. In contrast, if the lack of negative-emotion-induced blindness was due to a positivity effect in early attentional processes, we should see greater emotion- induced blindness from positive compared to negative distractors, in older adults compared to younger adults.

Given the numerical, though not significant, decrease in older adults’ performance on negative trials across lags in Experiment 1, we replaced lag-4 trials with lag-5 trials in Experiment 2 to increase the chance of capturing any delayed blindness effects. Indeed, some evidence suggests that attentional and early cognitive processing can be delayed in older adults compared to younger adults (see Zanto & Gazzaley, 2014). We also included emotional ratings of some of the distractor images in Experiment 2, to determine whether subjective ratings of arousal and valence correspond with the age difference observed in the emotion-induced blindness task.

Method

Participants.

Twenty-four younger adults (ages 18–23; M = 19.71 years old, 95% CI [19.13, 20.29]; 13 female, 11 male) and twenty-one older adults (ages 59–79; M = 68.38 years old, 95% CI [65.93, 70.83]; 13 female, 8 male) participated in Experiment 2, recruited from the same participant pools as in Experiment 1. The sample size of twenty-one participants per group was determined using data from Experiment 1 (performance at lag-2 between negative vs. neutral conditions for older and younger adults; 80% power, α = .05, computed with G*Power). Due to the online system of recruiting younger adults from the subject pool, we stopped on the day we achieved our sample N. We excluded three older adult participants’ data from analyses for poor performance (overall performance accuracy < 55%). Due to time constraints, one older adult participant did not complete the DASS-21 questionnaire. Participants were compensated $15 per hour for their participation, and the session took around 90 minutes.

Materials and Procedure.

The materials and procedure in Experiment 2 were similar to Experiment 1, with the following exceptions.

Experiment 2 was run in a dimly lit room with a CRT monitor set at a rate of 60 Hz. Distractor images in Experiment 2 included emotionally negative, emotionally positive, emotionally neutral, and “baseline” images. Emotionally negative, emotionally positive, and neutral images were chosen from the IAPS image database, and there were thirty-six images per distractor category in Experiment 2. All negative, neutral, and baseline images were from Experiment 1, but we reduced the number of distractor images to thirty-six per category so that each image was shown exactly twice in the experiment. The negative distractor images depicted mutilated or injured bodies, threatening animals, and threatening situations, while positive distractor images depicted erotica, extreme sports, and babies or happy couples. We purposely chose images to ensure that emotional categories represented a broad range of content. Most previous emotion-induced blindness experiments have found greatest impact from highly arousing, taboo, erotic, or extreme sport stimuli as positive stimuli (Arnell, Killman, & Fijavz, 2007; Most et al., 2007). These stimuli are often used because they are positive images that elicit the highest arousal ratings. However, due to using an older adult cohort—who sometimes do not rate the emotional qualities of such stimuli the same as younger adults (Backs, Da Silva, & Han, 2005)—we chose to include an additional “sweet” positive distractor category with other less- arousing, but still emotionally impactful images. Negative images (valence: M = 2.66, 95% CI [2.37, 2.94]; arousal: M = 6.55, 95% CI [6.39, 6.71]) and positive images (valence: M = 7.14, 95% CI [6.92, 7.36]; arousal: M = 5.86, 95% CI [5.56, 6.16]) had both more arousing normative ratings and significantly different valence ratings from neutral images (valence: M = 5.38, 95% CI [5.15, 5.61]; arousal: M = 3.39, 95% CI [3.24, 3.54]), ts > 11.38, ps < .001, and negative images differed from positive images both in valence and arousal ts > 4.09, ps < .001, with negative images having more negative and more arousing ratings than positive images.

Like Experiment 1, Experiment 2 contained 4 blocks of 72 trials. The trial structure in Experiment 2 was mostly the same as Experiment 1, except the 500 ms inter-trial interval was replaced with two fixation periods on every trial: one 2-second fixation before the RSVP, and one 2-second fixation between the end of the RSVP and response screen.3 To differentiate between this fixation period of rest and the period to make a response, participants were instructed to fixate when they saw a “+” on the screen, and make their response when they saw a “×”. As soon as participants made their response, the program advanced to the next trial.

Immediately after the rotation detection task, participants completed a ratings task, where they rated valence for nine distractor images from the rotation detection task, and then rated arousal for the same nine images. Ratings of valence and arousal were made on a nine-point scale from 1 (very negative/very non-arousing) to 9 (very positive/very arousing). All participants rated the same nine images in the same order, and the images were chosen to represent varied content that comprised each emotion type.

Before starting the rotation detection task, participants in Experiment 2 also completed the DASS-21 (Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scales; Lovibond & Lovibond, 1995), which was analyzed as an aggregate score as well as in subscores for depression, anxiety and stress.

Results

Questionnaires

There were no differences between younger and older adult performance on the WTAR vocabulary scores, CERAD recall scores or recognition memory scores, or the DASS-21 total score, nor in the DASS-21 subscales for depression, anxiety, or stress (see Table 2). Individual scores on these measures also did not correlate with the emotion-induced blindness effect.4

Rotation Detection Task

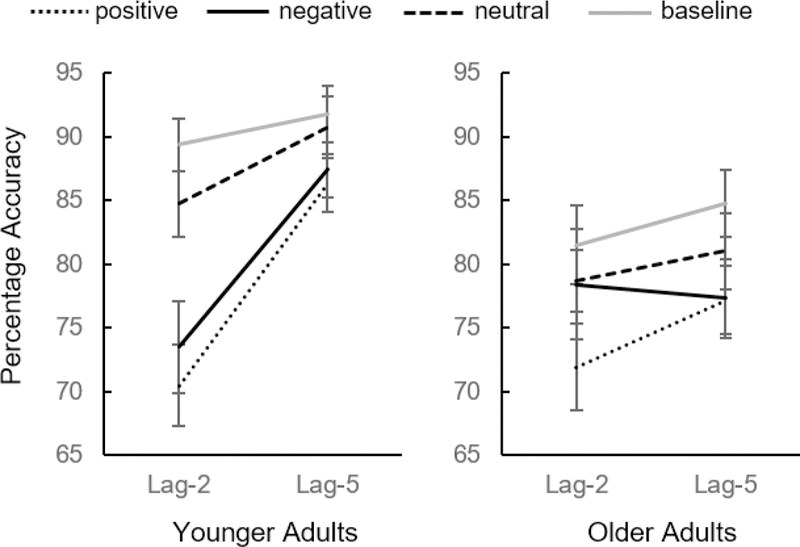

A 4 (distractor type: negative vs positive vs neutral vs baseline) x 2 (lag: 2 vs 5) x 2 (age group: older adults vs younger adults) mixed ANOVA revealed a significant main effect of age group, F(1,40) = 6.63, p = .014, ηp2 = 0.142, with worse target performance accuracy in the older adult group than in the younger adult group (Figure 3). There was also a significant main effect of distractor type, F(3,120) = 38.22, p < .001, ηp2 = 0.489, with worse performance overall in trials with positive and negative distractors and best performance in trials with baseline distractors. The main effect of lag was also significant, F(1,40) = 79.86, p < .001, ηp2 = 0.666, with better overall performance on lag-5 trials than lag-2 trials. The distractor type x lag interaction was also significant, F(3,120) = 5.22, p = .002, ηp2 = 0.116 - target performance impairment at lag-2 generally recovered at lag-5. There was also a significant distractor type x age group interaction, F(3,120) = 3.05, p = .031, ηp2 = 0.071, a lag x age group interaction, F(1,40) = 28.20, p < .001, ηp2 = 0.413 and a significant distractor type x lag x age group interaction, F(3,120) = 5.66, p = .001, ηp2 = 0.124.

Figure 3.

Emotion-induced blindness results from Experiment 2. Error bars represent within-subject, 95% confidence intervals.

Younger adults demonstrated emotion-induced blindness in both negative and positive distractor conditions. At lag-2, performance was worse in trials with negative distractors, t(23) = 4.67, p < .001, dz = 0.954, and positive distractors, t(23) = 6.12, p < .001, dz = 1.250, compared to trials with neutral distractors. However, there was no difference in lag-2 performance between negative and positive distractor trials, t(23) = 1.18, p = .250, dz = 0.241. Negative, positive, and neutral distractor conditions at lag 2 were also all worse than baseline performance at lag 2, ts ≥ 2.69, ps ≤ 0.013. At lag-5, there was no significant difference between negative and neutral trials, t(23) = 1.80, p = .086, dz = 0.367, or negative and positive trials, t(23) = 0.67, p = .508, dz = 0.137, but positive distractors were still more impactful than neutral distractors at lag 5, t(23) = 2.71, p = .012, dz = 0.554. At lag 5, there was a significant performance impairment in both negative, t(23) = 3.37, p = .003, dz = 0.688, and positive, t(23) = 3.05, p = .006, dz = 0.623, distractor trials compared to baseline lag-5 distractor trials, but no difference between neutral distractor trials and baseline performance at lag 5, t(23) = 0.69, p = .495, dz = 0.141.

In older adult lag-2 conditions, there was no difference in performance accuracy between trials with neutral and negative distractors, t(17) = 0.12, p = .907, dz = 0.028, but performance was worse in trials with positive distractors compared to neutral distractors, t(17) = 2.89, p =.010, dz = 0.682. Performance in positive distractor conditions was also worse than negative distractor conditions, t(17) = 2.36, p = .031, dz = 0.556. In addition, at lag 2, neither negative nor neutral distractor condition performance differed from baseline performance, ts ≤ 1.72, ps ≥ .104, but positive distractor performance did differ from baseline performance, t(17) = 3.60, p = .002, dz = 0.802. At lag 5, there were no significant differences between negative and neutral distractor trials, t(17) = 1.76, p = .097, dz = 0.414, negative and positive distractor trials, t(17) = 0.07, p = .944, dz = 0.017, nor positive and neutral distractor trials, t(17) =1.98, p = .064, dz = 0.467. Compared to baseline distractor conditions at lag 5, there was significant impairment in both negative, t(17) = 3.74, p = .002, dz = 0.880, and positive distractor trial conditions, t(17) = 3.35, p = .004, dz = 0.791, but no difference between neutral and baseline lag-5 trial conditions, t(17) = 1.82, p = .086, dz = 0.429.

Image Ratings

We next analyzed the valence and arousal ratings that participants gave to the nine exemplar images. Three older adult participants did not complete the image ratings task, because they ran out of time during their session. Overall, younger and older adults did not significantly differ in their arousal or valence ratings for positive (younger adults: arousal: M = 5.18, 95% CI [4.67, 5.69]; valence: M = 6.36, 95% CI [5.85, 6.88]; older adults: arousal: M = 5.98, 95% CI [5.33, 6.62]; valence: M = 6.27, 95% CI [5.65, 6.89]), negative (younger adults: arousal: M = 5.78, 95% CI [4.90, 6.65]; valence: M = 2.00, 95% CI [1.35, 2.65]; older adults: arousal: M = 6.38, 95% CI [5.13, 7.63]; valence: M = 2.40, 95% CI [1.61, 3.19]), or neutral (younger adults: arousal: M = 2.15, 95% CI [1.72, 2.58]; valence: M = 5.44, 95% CI [5.06, 5.83]; older adults: arousal: M = 4.31, 95% CI [3.39, 5.23]; valence: M = 5.42, 95% CI [4.58, 6.26]) images except for the arousal ratings of neutral images, as older adults rated neutral images as more arousing than younger adults, t(37) = 4.95. p < .001, d = 1.538. Younger adults rated negative, neutral, and positive images as all differently valenced (ts ≥ 4.52, ps < .001); older adults rated negative images as more negatively valenced than neutral and positive images (ts ≥ 5.13, ps < .001), and rated positive images as similarly valenced as neutral images, t(14) = 1.79, p = .095, dz = 0.203. Both younger and older adults rated negative and positive images as more arousing than neutral images (ts ≥ 2.53, ps ≤ .024), and both age groups rated no difference in arousal between negative and positive images (ts ≤ 1.23, ps ≥ .233).

Discussion

Younger adults demonstrated a typical emotion-induced blindness pattern, with greatest distraction at an early lag from positive and negative distractors compared to neutral and baseline distractors. Older adults still showed no more impairment in negative compared to neutral distractor conditions, but did show impairment in the positive distractor condition at lag 2 - consistent with a positivity effect in older adults. Younger and older adults performed similarly in measures of general cognitive ability (vocabulary and memory performance on the CERAD task) and depression, anxiety, and stress levels - and the individual differences did not correlate with the emotion-induced blindness patterns at lag 2. Emotional ratings of the images were also similar between older and younger adults, suggesting that the age difference in how distracting the negative images was not due to an age difference in how subjectively negative the pictures were.

Experiment 3

Experiment 3 was designed to capture the time course of emotion-induced blindness from negative and positive distractors in younger and older adults. We hypothesized that, like Experiments 1 and 2, compared to younger adults, older adults would be more distracted by positive compared to negative distractors. We also hypothesized that this difference would be most apparent at early lags than at later lags in the rotation detection task. Previous research with younger adults shows that emotion-induced blindness is generally greatest at lag 1 and performance gradually increases with increasing lag, up to around lag 4 or 5 (Ciesielski, Armstrong, Zald, & Olatunji, 2010; Kennedy & Most, 2015).

Method

Participants.

Participants in Experiment 3 were recruited online through Turk Prime and Amazon Mechanical Turk. We used Turk Prime to recruit participants based on their age (Litman, Robinson, & Abberbock, 2017), and we further verified participants’ ages by having them enter their age and year of birth during the experiment. One hundred four younger adults (ages 20–33; M = 26.28 years old, 95% CI [25.75, 26.81]; 32 female, 71 male, 1 unknown sex) and 103 older adults (ages 57–98; M = 64.93 years old, 95% CI [63.88, 65.98]; 50 female, 53 male) participated in the study (three other adults participated but were not included as they reported ages—between 40 and 44—that were in neither of the requested groups). Since the number of trials per condition in Experiment 3 were one sixth of what they were in Experiment 2, we recruited enough participants to mimic 30 trials per condition per each participant in Experiment 2. Data from eleven younger adult participants and two older adult participants were excluded due to poor performance (overall accuracy < 55%). Participants were compensated $3.00 for the 20-minute task.

Materials and Procedure.

Unlike Experiments 1 and 2, Experiment 3 was conducted online, and programmed through Inquisit.

In Experiment 3, distractor images were emotionally negative, emotionally positive, neutral, or “baseline” images. These came from a bank of 24 images per distractor type - all a subset of the 36 images in Experiment 3, to maintain the condition that each distractor image was shown twice in the experiment. Negative images (valence: M = 2.44, 95% CI [2.14, 2.75]; arousal: M = 6.56, 95% CI [6.34, 6.78]) and positive images (valence: M = 7.21, 95% CI [6.93, 7.48]; arousal: M = 5.92, 95% CI [5.55, 6.28]) had different valence and arousal rating norms than neutral images (valence: M = 5.27, 95% CI [5.01, 5.53]; arousal: M = 3.33, 95% CI [3.13, 3.53]), ts ≥ 10.55, ps < .001, and negative and positive images differed in both valence and arousal ratings, ts ≥ 3.09, ps ≤ .003.

Experiment 3 had two blocks of 96 trials. The distractor appeared in serial positions 3, 4, 5, or 6, and the target appeared at lag 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, or 8. Before every trial, there was a 1- second fixation period between trials, and immediately after the RSVP trial, participants saw a screen that asked them to press the “F” or “J” button to make their response. If they answered correctly, they saw text that read “Correct!”, and if they answered incorrectly, saw text that read “Incorrect.”

Participants viewed and agreed to the consent form online, and then started with an 8-trial practice round. At the end of the study, participants completed a short demographic questionnaire, and were debriefed about the goals of the study.

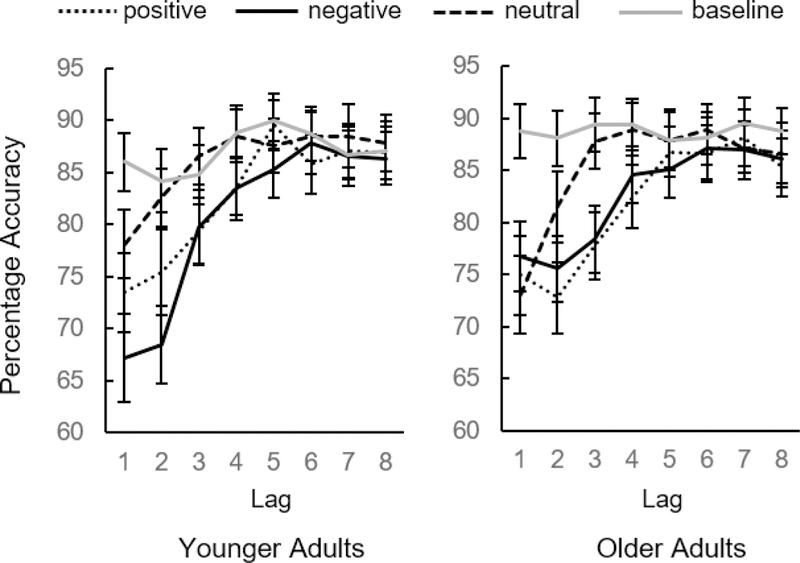

Results

A 4 (distractor type: negative vs positive vs neutral vs baseline) x 8 (lag: 1 through 8) x 2 (age group: older adults vs younger adults) mixed ANOVA revealed no significant main effect of age group, F(1,192) = 0.18, p = .671, ηp 2 = 0.01, to suggest that overall percentage accuracy was similar between younger and older adults in Experiment 3 (Figure 4). The main effect of distractor type was significant, F(3,576) = 60.77, p < .001, ηp2 = 0.240, with worse overall performance in negative and positive distractor conditions and best performance in baseline conditions. There was also a significant main effect of lag, F(7,1344) = 60.43, p < .001, ηp2 = 0.239 - percentage accuracy generally improved with increased lag. There was also a significant distractor type x age group interaction, F(3,576) = 4.11, p = .007, ηp2 = 0.021, and a significant distractor type x lag x age group interaction, F(21,4032) = 1.80, p = .014, ηp2 = 0.009, but no significant lag x age group interaction, F(7,1344) = 1.00, p = .429, ηp2 = 0.005, indicating that performance was generally similar across lags between younger and older adults, but the pattern of distractor types across lags differed between the age groups.

Figure 4.

Emotion-induced blindness results from Experiment 3. Error bars represent within-subject, 95% confidence intervals.

Younger adult participants performed worse in negative compared to positive trials at lag-1, lag-2, and lag-5, ts ≥ 2.33, ps ≤ .022, but at no other lags, ts ≤ 0.91, ps ≥ .364. Performance on negative distractor trials was also worse than on neutral distractor trials at early lags 1–4, ts ≥ 2.53, ps ≤ .013, but not at later lags 5–8, ts ≤ 1.25, ps ≥ .215. Performance was worse on positive distractor trials than on neutral distractor trials at lags 2–4, ts ≥ 2.59, ps ≤ 0.011, but not at lag-1, t(91) = 1.81, p = .074, dz = 0.189, or lags 5–8, ts ≤ 1.50, ps ≤ .136. Compared with performance on baseline trials, accuracy on positive distractor trials was worse at lags 1–4, ts ≥ 2.54, ps ≤ .013, but not 5–8, ts ≥ 1.30, ps ≤ .196. Similarly, performance was worse on negative distractor trials than on baseline distractor trials at lags 1–5, ts ≥ 2.00, ps ≤ .048, but there was no difference in performance on lags 6–8, ts ≤ 0.46, ps ≥ .644.

Older adult participants’ performance did not differ between negative and positive trials at any lag, ts ≤ 1.18, ps ≥ .239. Performance on negative distractor trials did not differ from neutral distractor trials at lag-1, t(100) = 1.43, p = .155, dz = 0.146, or lags 5–8, ts ≤ 1.49, ps ≥ .141, but was worse on negative distractor trials compared to neutral distractor trials on lags 2–4, ts ≥ 2.31, ps ≤ .023. Accuracy on positive distractor trials was worse than on neutral distractor trials at lags 2–4, ts ≥ 3.29, ps ≤ .001, but not at lag-1, t(100) = 0.65, p = .514, dz = 0.065, or lags 5–8, ts ≤ 1.32, ps ≥ .191. Performance on negative distractor trials was worse than on baseline distractor trials at lags 1–4, ts ≥ 2.56, ps ≤ .012, but not lags 5–8, ts ≤ 1.44, ps ≥ .155; and performance on positive distractor trials was worse on baseline distractor trials at lags 1–4, ts ≥ 3.16, ps ≤ 0.002, and lag-8, t(100) = 2.01, p = .048, dz = 0.200, but not lags 5–7, ts ≤ .82, ps ≥ .416.

Discussion

Younger adults were more impaired in detecting the target at early lags, especially after negative distractors and positive distractors. In previous research (including Experiment 2), positive distractors tend to be more distracting than negative distractors (Arnell et al., 2007; Most et al., 2007). However, the lowered arousal of the set of positive images that we used in this experiment compared to past experiments may have decreased their distracting power compared to the negative images. Nevertheless, the interaction between negative and positive distractors across young and older age groups at early lags was consistent with a positivity effect in older adults. That is, while younger adults showed greater impairment for negative than positive distractor conditions, older adults showed no difference between negative and positive distractor conditions. Older adults also showed similar impairment for neutral, negative, and positive distractors at lag 1, but faster recovery across lags for neutral compared to negative and positive distractors.

Experiment 4

Previous studies show that dual-task designs that divert cognitive resources eliminate the positivity effect for attention and memory in older adults (Knight et al., 2007; Mather & Knight, 2005). Such a pattern suggests that older adults prioritize positive information over negative information by employing their cognitive resources to match their emotional goals. If taxing cognitive resources diminishes the positivity effect at an early attentional level, it would indicate that cognitive control mechanisms underlie the positivity effect patterns we observed in early attention. In Experiment 4, we introduced a working memory task on half of trials, to see if older adults’ relatively greater emotion-induced blindness for positive than negative stimuli compared with younger adults requires attentional control resources on the part of older adults. We hypothesized that this would be the case, as would be expected if the age-by-valence interaction is driven by emotion regulation goals.

Method

Participants.

Participants in Experiment 4 were recruited online through Turk Prime (Litman et al., 2017) and Amazon Mechanical Turk. In total, fifty-six younger adult participants (ages 22–34; M = 29.54 years old, 95% CI [28.67, 30.40]; 10 female, 46 male) and fifty-seven older adult participants (ages 54–73, M = 63.70, 95% CI [62.57, 64.83]; 38 female, 19 male) took part in the study. Sample size was determined to emulate a similar number of trials as Mather and Knight’s 2004, Experiment 3 design. An additional four participants were not included because their ages (from 39–49 years old) did not fall within the range of either age group. Data from two younger adults and one older adult were excluded for poor performance (average performance accuracy < 55%). Participants were compensated $5.44 for their participation, and the task took about 35 minutes to complete.

Materials and Procedure.

The materials and procedure in Experiment 4 were similar to Experiment 3, with the following exceptions.

Experiment 4 comprised four blocks of forty-eight trials, and included the same distractors used in Experiment 3. Distractors were presented at serial position 3, 4, 5, or 6 and targets were presented at lag 2, 5, or 7. The working memory (WM) manipulation was completed using a blocked design. Blocks were assigned as either high WM load or no WM load, and were presented in an ABAB order, such that half of participants were randomly assigned to the high working memory load condition first, and the other half of participants were assigned to the no working memory load condition first. On high WM load trials, participants saw a one-second fixation cross, followed by 3 digits presented at 500ms each. After the digits, there was another 500ms fixation screen, followed by the RSVP stream of pictures. At the end of the RSVP stream, participants were asked to detect rotations as in Experiment 3, and then report the digits in order. On the no WM load trials, the trial structure was the same, but participants saw three symbols (“\”, “@”, “#”, “$”, “%”, “:”, “&”, “*”, or “/”) instead of digits, and did not report them - the next trial advanced as soon as participants made their response for the rotated target.

Results

Working memory performance

To be sure that participants were engaging in the working memory task, we first looked at performance accuracy in the high working memory load condition, to see if participants were able to accurately report the three digits that were presented before the RSVP stream. Overall performance accuracy was high in both younger (M = 94.73%, 95% CI = [93.33, 96.13]) and older (M = 95.94%, 95% CI = [94.73, 97.16]) adults, and all participants scored above 77% overall accuracy on the working memory portion of the task.

Rotation detection performance

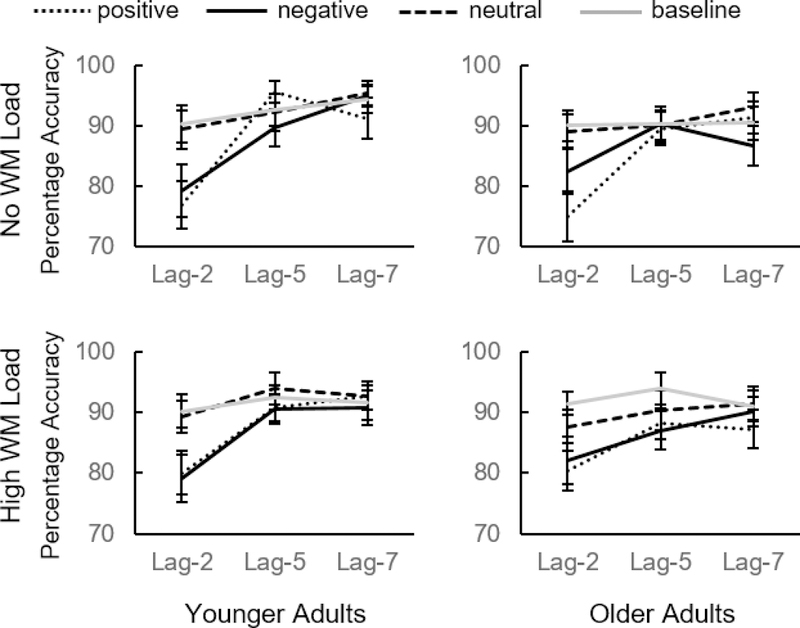

A 4 (distractor type: negative vs positive vs neutral vs baseline) x 3 (lag: 2 vs 5 vs 7) x 2 (WM load: high load vs no load) x 2 (age group: older adults vs younger adults) mixed ANOVA revealed no significant main effect of age group, F(1,108) = 1.96, p = .164, ηp2 = 0.018, indicating that overall performance accuracy was similar between younger and older adults (Figure 5). There was a significant main effect of both distractor type, F(3,324) = 42.85, p < .001, ηp2 = 0.284, and lag, F(2,216) = 108.43, p < .001, ηp2 = 0.501, with worse performance on trials with negative and positive emotional distractors over neutral and baseline distractors, and worse performance on early compared to later lags. There was also a significant distractor type x lag interaction, F(6,648) = 17.33, p < .001, ηp2 = 0.138, with performance increasing faster from earlier to later lags in emotional distractor conditions compared to neutral and baseline distractor conditions. The main effect of WM load was not significant, F < 1. There was also no significant interaction between WM load x distractor type, F < 1, or WM load x lag, F(2,216) = 2.15, p = .119, ηp2 = 0.020. In the other two-way interactions, distractor type x age group was not significant, F(3,324) = 1.11, p = .343, ηp2 = 0.010, nor was the WM load x age group interaction, F < 1, but there was a significant interaction of lag x age group, F(2,216) = 5.35, p = .005, ηp2 =0.047, such that younger and older adults differed in their overall performance across lags, with younger adults improving in performance more over lags. The three-way interactions were not significant between distractor type x lag x age group, F(6,648) = 1.28, p = .266, ηp2 = 0.012, distractor type x WM load x age group, F < 1, or WM load x lag x age group, F < 1. There was, however, a significant distractor type x WM load x lag interaction, F(6,648) = 2.18, p = .043, ηp2 = 0.20, as well as a significant distractor type x WM load x lag x group interaction, F(6,648) = 2.30, p = .034, ηp2 = 0.21, indicating that working memory load impacted the pattern of different distractor types across lags, and that this impact differed between younger adults and older adults.

Figure 5.

Emotion-induced blindness results from Experiment 4. Error bars represent within-subject, 95% confidence intervals.

Younger adults demonstrated emotion-induced blindness after both negative and positive distractors regardless of working memory load. At lag-2, in both WM load conditions, performance on both negative and positive distractor trials was worse than on both neutral and baseline distractor trials, ts ≥ 3.47, ps ≤ 001. Across both WM load conditions, there was no performance difference at lag-2 between negative and positive distractor conditions, ts ≤ .83, ps ≥ .410, nor between neutral and baseline distractor conditions, ts ≤ .44, ps ≥ .659. In general, at later lags, performance gradually improved in all distractor conditions for younger adults.1

Older adults also demonstrated emotion-induced blindness regardless of working memory load. At lag 2, across WM load conditions, performance was significantly impaired on both negative and positive distractor trials compared to neutral and baseline distractor trials, ts ≥ 2.32, ps ≤ .024. However, unlike younger adults, performance at lag-2 was significantly worse on positive distractor trials compared to negative distractor trials when there was no ongoing working memory task, t(55) = 2.92, p = .005, dz = 0.390, but there was no difference between negative and positive distractor trial types when there was an ongoing working memory task, t(55) = 0.61, p = .544, dz = 0.082. There was also no difference between neutral and baseline distractor conditions when there was no ongoing working memory task, t(55) = 0.53, p = .597, dz = 0.071, but there was significantly worse performance in neutral compared to baseline distractor conditions when there was an ongoing working memory task, t(55) = 2.18, p = .034, dz = 0.291. Older adults’ performance generally increased or plateaued with greater lag for all distractor type trials.

Discussion

Cognitive load did not affect younger adults’ performance at early lags. However, the cognitive load did impact older adult performance, such that their greater distraction from positive distractors compared to negative distractors at lag-2 disappeared when WM resources were limited. These results suggest that the positivity effect - which we observe in this task at early stages of attention - relies on cognitive control resources, and no longer presents itself when cognitive resources are otherwise occupied.5

General discussion

Emotional stimuli grab attention, but often at the cost of attention to anything around them in time and space. The emotion-induced blindness effect is a striking example of this trade-off, as people have difficulty detecting rotated pictures appearing shortly after emotional distractors even though the emotional distractors are irrelevant to the main task (Kennedy & Most, 2015; Most et al., 2005; Wang et al., 2012).

In terms of grabbing attention, a number of studies have found that positive stimuli have more pull than negative stimuli for older adults but not for younger adults (e.g., Bannerman, Regener, & Sahraie, 2011; Fairfield, Di Domenico, Palumbo, & Mammarella, 2016; Isaacowitz, Wadlinger, Goren, & Wilson, 2006; Knight et al., 2007; Sasse, Gamer, Büchel, & Brassen, 2014; for meta-analysis see Reed et al., 2014). Yet it has not been clear how early this age-related positivity effect emerges and whether it comes with a cost of processing stimuli presented immediately afterwards. In the current study, both younger adults and older adults demonstrated emotion-induced blindness. These results suggest that older adults’ general decrease in attention inhibition does not keep them from experiencing emotion-induced blindness. However, in older adults, distraction from negative stimuli was not always present (Experiments 1 & 2), and distraction from positive stimuli compared with negative stimuli was generally greater than it was for younger adults (Experiments 2–4) - suggesting a positivity effect in early attention. These findings indicate that age differences in the impact of positive versus negative stimuli emerge at quite early stages of attention - in the first few hundred milliseconds of an image appearing.

While a lack of the effect altogether could be accounted for by age-related impairments in inhibition (e.g., Hasher & Zacks, 1988; Lustig, Hasher, & Zacks, 2007), the fact that positive distractors induce blindness for subsequent targets for older adults indicates that the age-related emotion differences are not due to age-related declines in inhibition. Moreover, it is worth noting that participants were aware of their performance accuracy of every trial. Older adults can sometimes find these situations as threatening or uncomfortable (e.g., Barber & Mather, 2014), but this age-related positivity effect was maintained throughout the task despite this possible negative influence on older adults.

Another possibility is that older adults show less emotion-induced blindness for negative than positive stimuli because of impaired brain mechanisms for rapidly detecting negative, potentially threatening, stimuli (e.g., ‘aging-brain hypothesis,’ Cacioppo et al., 2011; but see Nashiro, Sakaki, & Mather, 2012). Given the rapid onset of the positivity effect within the current experiments, this explanation sounds plausible. On the other hand, Socioemotional Selectivity Theory posits that the positivity effect emerges because of shifts in the relevance of emotional goals that require cognitive control resources.

To test whether the availability of cognitive control resources influenced the positivity effect seen in this paradigm, in Experiment 4 we had participants perform half of the trials while keeping in mind three digits whereas the other trials involved no concurrent working memory load. We found that the positivity effect was reduced when older adults simultaneously performed a WM task-similar to previous memory studies that show dual-task, divided attention conditions eliminate the age-related positivity effect (Knight et al., 2007; Mather & Knight, 2005). Specifically, in the current paradigm, older adults showed greater blindness after viewing positive distractors compared to negative distractors when they had full attention than when they had a cognitive load. These results suggest that the positivity effect is a rapidly implemented bias that occurs within a fraction of a second of stimulus presentation but nevertheless is mediated by the same cognitive control resources needed for working memory.

Our results are not without their limitations. We only tested healthy older adults - and while the literature is mixed as to how the positivity effect can change with cognitive decline (e.g., Bohn, Kowng See, & Fung, 2016; Fleming, Kim, Doo, Maguire, & Potkin, 2003; Gorenc-Mahmutaj, Degen, Wetzel, Urbanowitsch, & Funke, 2015; Leal, Noche, Murray, & Yassa, 2016) - it is unclear how older adults with reduced cognitive abilities may be affected at this early attentional level. We also did not control for handedness in our study, which some research indicates can prioritize positive or negative images when responses are made with the dominant versus non-dominant hand (Freddi et al., 2016; Song, Chen, & Proctor, 2017). In our study, participants responded with their preferred hand to rotated images - and not emotional images per se - but future emotion-induced blindness studies could incorporate handedness with button responses to see if hand dominance modulates the impact valenced distractors. Moreover, while we have identified that cognitive load plays a role in the manifestation of the positivity effect at an early attentional level, future neuroimaging work may aid in identifying more specific brain mechanisms or networks involved in this early attentional impact, such as prefrontal regions related to emotion regulation (see Ochsner & Gross, 2005).

Beyond mechanistic understanding for age-related changes in attentional prioritization, the way in which emotion can impact our attention has implications for the way we interact in the environment. Compared to younger adults, older adults prioritize positive information over negative information in their early attention. This speaks to situations when selective attention is needed (e.g., driving) and evaluating the possible distracting influence of emotional information (e.g., billboards). It also has implications in the way that we communicate and prioritize information with older adults compared to younger adults and provides more insight into how taxing cognitive demands changes the way that older adults experience the environment around them.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank Carmina Raquel for her help on this project. This research was supported by the National Institute On Aging of the National Institutes of Health R01AG025340 to MM and F32AG057162 to BLK. Data for this project and supplemental material are available online at https://osf.io/8jhse/. Emotional stimuli used in these experiments are from the International Affective Picture System, and the list of images used in these studies is also available at https://osf.io/8jhse/.

Footnotes

Across all four experiments, there was a wide variability in the ages of older adult participants. Nevertheless, when we restricted the analyses to include only older adult participants between the ages of 60–75 years old, the age x valence effects remained the same across all experiments.

In Experiment 1, we correlated individual performance for all participants on the rotation detection task with their questionnaire responses. Neither individual vocabulary or CERAD recognition memory scores correlated with overall performance on the rotation detection task, rs ≤ .151, ps ≥ .353, nor did they correlate with the amount of distraction from negative compared to neutral distractors, rs < .242, ps > .132. CERAD recall memory scores did correlate with performance at lag 4: recall memory scores positively correlated with overall performance on the rotation detection task, r(40) = .397, p = .011, and also positively correlated with distraction from negative compared to neutral distractors at lag 4, r(40) = .321, p = .043. Recall scores did not, however, correlate with negative distraction compared to neutral distraction at lag 2, r(40) = .132, p = .418, which was our main lag of interest for the emotion-induced blindness effect.

The reason for this change was to collect pupil size after the stream of images on every trial (note that pupil data are not reported here).

In Experiment 2, individual scores on the WTAR vocabulary task and CERAD recall or recognition tests did not correlate with a) overall performance on the rotation detection task, b) distraction from negative compared to neutral images, c) distraction from positive compared to neutral images, or d) distraction from negative compared to positive distractors, rs ≤ .231, ps ≥ .141. The DASS-21 and subscales also did not correlate with overall performance, rs ≤ .267, ps ≥ .092, nor distraction from negative compared to neutral distractors at either lag, rs ≤ .110, ps ≥ .493. There were two significant correlations between the DASS-21 and performance on lag 5 trials: a) there was a significant correlation between the DASS anxiety subscale and worse performance on positive lag-5 compared to neutral lag-5 distractor trials, r(41) = .360, p = .021, and b) there was a significant correlation between overall DASS-21 score and worse performance on positive lag 5 compared to negative lag 5 trials, r(41) = .329, p = .035. The DASS-21 measures did not otherwise correlate with performance on trials with positive compared to neutral distractors or positive compared to negative distractors at lag 5, rs ≤ .301, ps ≥ .056. Significant correlations were only found at lag 5 - there was also no correlation between the DASS-21 scores and performance at lag-2, rs ≤ .243, ps ≥ .126, which again was the main lag of interest for the emotion-induced blindness effect.

The age-related positivity effect is operationalized as an age-by-valence interaction that can take the form of a negativity bias among younger adults or a positivity bias among older adults (Reed & Carstensen, 2012). Thus, conceptually, it is not surprising that in Experiment 3, the age-by-valence interaction was driven by greater impact of negative than positive pictures for younger adults than for older adults. However, what is puzzling is that the specific nature of the age-by-valence interaction shifted from Experiment 3 to Experiment 4, which used the same stimuli and recruited from the same participant pool. The main difference between the two experiments was the insertion of digits or symbols in Experiment 4 that mimicked a “countdown” to the start of the RSVP trial, and restricted possible lags for the target items. Previous studies have noted that participants can tune their attention to the temporal patterns within rapid serial visual presentations (e.g., Ambinder & Lieras, 2009; Shin, Chang, & Cho, 2015). Thus, it is possible that the experimental conditions of Experiment 4 yielded more accurate and tuned expectations of targets in the rapid stream. As such, participants’ performance in Experiment 4 may have benefitted from this temporal expectation, and the relative benefit of temporal expectation may have interacted with the relative distraction induced by positive vs. negative images for each age group.

References

- Ambinder MS, & Lleras A (2009). Temporal tuning and attentional gating: Two distinct attentional mechanisms on the perception of rapid serial visual events. Attention, Perception & Psychophysics, 71(7), 1495–1506. 10.3758/APP.7L7.1495 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnell KM, Killman KV, & Fijavz D (2007). Blinded by emotion: Target misses follow attention capture by arousing distractors in RSVP. Emotion, 7(3), 465–477. 10.1167/4.8.359 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Backs RW, Da Silva SP, & Han K (2005). A comparison of younger and older adults’ self-assessment Manikin ratings of affective pictures. Experimental Aging Research, 31(4), 421–440. 10.1080/03610730500206808 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bannerman RL, Regener P, & Sahraie A (2011). Binocular rivalry: A window into emotional processing in aging. Psychology and Aging, 26(2), 372–380. 10.1037/a0022029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barber SJ, & Mather M (2014). Stereotype threat in older adults: When and why does it occur and who is most affected ? In Verhaeghen P & Hertzog C (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Emotion, Social Cognition, and Problem Solving in Adulthood. 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199899463.013.008 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barber SJ, Opitz PC, Martins B, Sakaki M, & Mather M (2016). Thinking about a limited future enhances the positivity of younger and older adults’ recall: Support for socioemotional selectivity theory. Memory & Cognition, 44, 869–882. 10.3758/s13421-016-0612-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohn L, Kowng See ST, & Fung HH (2016). Time perspective and positivity effects in Alzheimer’s disease. Psychology and Aging, 31(6), 574–582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brainard DH (1997). The Psychophysics Toolbox. Spatial Vision, 10(4), 433–436. 10.1163/156856897X00357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cacioppo JT, Berntson GG, Bechara A, Tranel D, & Hawkley LC (2011). Could an aging brain contribute to subjective well-being?: The value added by a social neuroscience perspective. In Todorov A, Fiske S, & Prentice D (Eds.), Social Neuroscience: Toward understanding the underpinnings of the social mind (pp. 249–262). 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195316872.003.0017 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carstensen LL (2006). The influence of a sense of time on human development. Science, 312(5782), 1913–1915. 10.1126/science.1127488 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charles ST, Mather M, & Carstensen LL (2003). Aging and emotional memory: The forgettable nature of negative images for older adults. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 132(2), 310–324. 10.1037/0096-3445.132.2.310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chun MM, & Potter MC (1995). A two-stage model for multiple target detection in rapid serial visual presentation. Journal of Experimental Psychology. Human Perception and Performance, 21(1), 109–27. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7707027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciesielski BG, Armstrong T, Zald DH, & Olatunji BO (2010). Emotion modulation of visual attention: Categorical and temporal characteristics. PLoS ONE, 5(11). 10.1371/journal.pone.0013860 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cousineau D (2005). Confidence intervals in within-subject designs: A simpler solution to Loftus and Masson’s method. Tutorials in Quantitative Methods for Psychology, 1(1), 42–45. [Google Scholar]

- Fairfield B, Di Domenico A, Palumbo R, & Mammarella N (2016). Aging and visual serial search for schematic emotional faces. Journal of Geriatric Medicine and Gerontology, 2(1), 2:009. [Google Scholar]

- Feng MC, Courtney CG, Mather M, Dawson ME, & Davison GC (2011). Age-related affective modulation of the startle eyeblink response: Older adults startle most when viewing positive pictures. Psychological Aging, 6(3), 752–760. 10.3816/CLM.2009.n.003.Novel [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming K, Kim SH, Doo M, Maguire G, & Potkin SG (2003). Memory for emotional stimuli in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. American Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease & Other Dementias, 18(6), 340–342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freddi S, Brouillet T, Cretenet J, Heurley LP, Dru V, & Dru V (2016). A continuous mapping between space and valence with left- and right-handers. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 23, 865–870. 10.3758/s13423-015-0950-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorenc-Mahmutaj L, Degen C, Wetzel P, Urbanowitsch N, & Funke J (2015). The positivity effect on the intensity of experienced emotion and memory performance in mild cognitive impairment and dementia. Dementia and Geriatric Cognitive Disorders, 5, 233–243. 10.1159/000381537 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gronchi G, Righi S, Pierguidi L, Giovannelli F, Murasecco I, & Viggiano MP (2018). Automatic and controlled attentional orienting in the elderly: A dual-process view of the positivity effect. Acta Psychologica, 185, 229–234. http://doi.org/10.1016Zj.actpsy.2018.02.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasher L, & Zacks RT (1988). Working memory, comprehension, and aging: A review and a new view. Psychology of Learning and Motivation - Advances in Research and Theory. 10.1016/S0079-7421(08)60041-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Holdnack HA (2001). Wechsler Test of Adult Reading: WTAR. San Antonio: The Psychological Corporation. [Google Scholar]

- Isaacowitz DM, Allard ES, Murphy NA, & Schlangel M (2009). The time course of age-related preferences toward positive and negative stimuli. Journals of Gerontology - Series B Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 64(2), 188–192. 10.1093/geronb/gbn036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isaacowitz DM, Wadlinger H a, Goren D., & Wilson HR. (2006). Is there an age-related positivity effect in visual attention? A comparison of two methodologies. Emotion, 6(3), 511–516. 10.1037/1528-3542.6.3.511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy BL, & Most SB (2015). The rapid perceptual impact of emotional distractors. Plos One, 10(6), e0129320. 10.1371/journal.pone.0129320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy BL, Newman VE, & Most SB (2018). Proactive deprioritization of emotional distractors enhances target perception. Emotion, 18(7), 1052–1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight M, Seymour TL, Gaunt JT, Baker C, Nesmith K, & Mather M (2007). Aging and goal-directed emotional attention: Distraction reverses emotional biases. Emotion, 7(4), 705–14. 10.1037/1528-3542.7A705 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang PJ, Bradley MM, & Cuthbert BN (2008). International affective picture system (IAPS): Affective ratings of pictures and instruction manual. Technical Report A-8. http://doi.org/10.1016Zj.epsr.2006.03.016 [Google Scholar]

- Le Duc J, Fournier P, & Hébert S (2016). Modulation of prepulse inhibition and startle reflex by emotions: A comparison between young and older adults. Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience, 8(FEB), 1–8. 10.3389/fnagi.2016.00033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leal SL, Noche JA, Murray EA, & Yassa MA (2016). Positivity effect specific to older adults with subclinical memory impairment. Learning & Memory, 23, 415–421. 10.1101/lm.042010.116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litman L, Robinson J, & Abberbock T (2017). TurkPrime.com: A versatile crowdsourcing data acquisition platform for the behavioral sciences. Behavior Research Methods, 49(2), 433–442. 10.3758/s13428-016-0727-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loftus GR, & Masson MEJ (1994). Using confidence intervals in within-subject designs. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 1(4), 476–490. 10.3758/BF03210951 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovibond SH, & Lovibond PF (1995). Manual for the Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale-21 items (DASS-21). Manual for the Depression Anxiety & Stress Scales, 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Lustig C, Hasher L, & Zacks RT (2007). Inhibitory deficit theory: Recent developments in a new view In Gorfein DS & MacLeod CM (Eds.), The Place of Inhibition in Cognition (59th ed, pp. 145–162). American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Mather M (2016). Commentary: Modulation of prepulse inhibition and startle reflex by emotions: A comparison between young and older adults. Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience, 8(106). 10.3389/fnagi.2016.00106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mather M, & Carstensen LL (2003). Aging and attentional biases for emotional faces. Psychological Science, 14(5), 409–415. 10.1111/1467-9280.01455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mather M, & Carstensen LL (2005). Aging and motivated cognition: The positivity effect in attention and memory. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 9(10), 496–502. http://doi.org/10.1016Zj.tics.2005.08.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mather M, Clewett D, Sakaki M, & Harley CW (2016). Norepinephrine ignites local hot spots of neuronal excitation: How arousal amplifies selectivity in perception and memory. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 39 10.1017/S0140525X15000667 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mather M, & Knight M (2005). Goal-directed memory: The role of cognitive control in older adults’ emotional memory. Psychology and Aging, 20(4), 554–570. 10.1037/0882-7974.20A554 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]