Abstract

Purpose

Women with anorexia nervosa, a psychiatric disorder characterized by self-induced starvation and low body weight, have impaired bone formation, low bone mass and an increased risk of fracture. IGF-1 and leptin are two nutritionally-dependent hormones that have been associated with low bone mass in women with anorexia nervosa. We hypothesized that IGF-1 and leptin would also be positively associated with estimated bone strength in women with anorexia nervosa.

Methods

In this cross-sectional study of 38 women (19 women with anorexia nervosa and 19 normal-weight controls), we measured serum IGF-1 and leptin and performed finite element analysis of high resolution peripheral quantitative CT images to measure stiffness and failure load of the distal radius and tibia.

Results

IGF-1 was strongly correlated with estimated bone strength in the radius (R=0.52, p=0.02 for both stiffness and failure load) and tibia (R=0.55, p=0.01 for stiffness and R=0.58, p=0.01 for failure load) in the women with anorexia nervosa but not in normal-weight controls. In contrast, leptin was not associated with estimated bone strength in the group of women with anorexia nervosa or normal-weight controls.

Conclusions

IGF-1 is strongly associated with estimated bone strength in the radius and tibia in women with anorexia nervosa. Further studies are needed to assess whether treatment with recombinant human IGF-1 will further improve bone strength and reduce fracture risk in this population.

Keywords: Finite element analysis, Anorexia Nervosa, IGF-1, Leptin

Summary

IGF-1 and leptin are two nutritionally-dependent hormones associated with low bone mass in women with anorexia nervosa. Using finite element analysis, we estimated bone strength in women with anorexia nervosa and found that IGF-1 but not leptin correlated significantly with estimated bone strength in both the radius and tibia.

Introduction

Anorexia nervosa is a psychiatric illness characterized by low body-weight and an intense fear of gaining weight[1]. Anorexia nervosa, which serves as a model of chronic starvation, is associated with a number of medical co-morbidities, the most common being low bone mass. Approximately 85% of women with anorexia nervosa have bone mineral density (BMD) values more than one-standard deviation below an age-comparable mean[2] and importantly, this low bone mass is associated with a significantly increased risk of fracture[3, 4].

We have previously shown that BMD is not a predictor of prevalence of fracture in adolescents with anorexia nervosa[5]. This is likely due to the fact that the ability of bone to resist fracture is dependent not only on bone mass but also on microarchitectural properties. High resolution peripheral quantitative CT (HR-pQCT) provides a method of quantifying cortical and trabecular parameters of bone microarchitecture at the radius and tibia, which have been shown to predict fracture independently of BMD in postmenopausal women[6]. Importantly, failure load and stiffness, two estimates of bone strength, can be estimated using microfinite element analysis and these estimates of bone strength are similarly able to predict fracture independently of BMD[7]. Therefore, defining the determinants of estimated bone strength may reveal new insight into fracture risk in anorexia nervosa.

In addition to low bone mass, anorexia nervosa is also characterized by functional hypothalamic amenorrhea and growth hormone resistance, both of which may represent adaptations to chronic starvation through the reduction in associated expenditure of energy on reproduction and growth. A reduction in the adipose tissue derived hormone leptin is associated with functional hypothalamic amenorrhea in anorexia nervosa[8] and when levels of leptin are normalized in women with functional hypothalamic amenorrhea by treatment with recombinant human leptin, luteinizing hormone pulsatility is restored[9]. A consequence of GH resistance is reduced production of IGF-1, a liver-derived hormone which mediates most of the growth-promoting effects of GH[10, 11]. IGF-1 has been shown to be an important regulator of BMD in animal models [12] and in postmenopausal women, IGF-1 has been associated with both BMD [13] and an increased fracture risk even after controlling BMD [14]. Similarly, in anorexia nervosa, low levels of both leptin and IGF-1 have been associated with low BMD [15–17]. Indeed, treatment with recombinant human IGF-1 increases bone formation markers in individuals with anorexia nervosa[18, 19] and treatment with recombinant human leptin increases markers of bone formation in women with hypothalamic amenorrhea[9]. Therefore, low levels of both leptin and IGF-1 appear to mediate the low bone mass in anorexia nervosa but whether they are also mediators of bone strength is not known, providing rationale to test the hypothesis that low levels of IGF-1 and leptin are associated with decreased estimated bone strength in anorexia nervosa.

Materials and Methods

Subjects

38 women were studied: 19 with anorexia nervosa (28.3 ± 4.6 years (mean ± SD)) and 19 normal-weight controls of comparable age, (27.3 ± 3.4 years; p=0.47). BMD and microarchitecture data from a subset of the women with anorexia nervosa and normal-weight controls were previously published[20–23]. Women with anorexia nervosa were recruited through referrals from local eating disorder providers and on-line advertisements, and controls were recruited through on-line advertisements. Subjects with anorexia nervosa met DSM-5 criteria. All normal-weight control subjects were having regular menstrual cycles and were receiving no medications known to affect bone mass. No subject had received estrogen within three months of the study. Normal-weight controls did not have a past or present history of an eating disorder. Subjects with abnormal thyroid function tests or chronic diseases known to affect bone mineral density (other than anorexia nervosa) were excluded from participation.

All study subjects were examined and blood was drawn for laboratory studies at a study visit at the MGH Translational and Clinical Research Center. Height was measured as the average of 3 readings on a single stadiometer, and subjects were weighed on an electronic scale while wearing a hospital gown. Frame size was estimated using caliper measurement of elbow breadth with comparison to norms based on U.S Health and Nutritional Examination Survey I data and percent ideal body weight was calculated based on 1983 Metropolitan Life Height and Weight tables[24]. BMI was calculated using the formula [weight (kg)/height (meter)2].

The study was approved by the Partners Institutional Review Board and complied with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act guidelines. Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects.

Biochemical Assessment

IGF-1 was measured by a luminescent immunoassay analyzer (ISYS Analyzer; Immunodiagnostics Corporation, Woburn, MA) with a detection limit of 4.4 ng/mL and an intra-assay coefficient of variation (CV) of 2.2% and an inter-assay CV of 5.1%. Leptin was measured by ELISA (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) with a detection limit of 0.78 ng/mL and an intra-assay CV of 3.2% and an inter-assay CV of 4.4%. Five subjects with anorexia nervosa had levels of leptin below the detection limit of the assay and were assigned a value of 0.5 ng/mL.

Radiologic Imaging

Dual energy X-ray absorptiometry and HR-pQCT

Subjects underwent dual energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) to measure areal BMD of the posterior-anterior lumbar spine (L1-L4), lateral spine (L2-L4), left total hip, and left femoral neck using a Hologic Discovery A densitometer (Hologic Inc., Bedford, MA) at their study visit. Coefficients of variation of DXA have been reported as < 2.2% for bone[25].

All participants underwent HR-pQCT of the non-dominant distal radius and tibia (Xtreme CT; Scanco Medical AG, Bruttisellen, Switzerland) with an isotropic voxel size of 82 μm3 as previously described [6]. We used linear microfinite element analysis of HR-pQCT images in order to estimate the biomechanical properties of the distal radius and the distal tibia under uniaxial compression loading, as previously described [26, 27]. The outcomes from the microfinite element analysis included both stiffness (kN/mm) and failure load (kN). A prior study reported strong associations between the biomechanical properties derived from microfinite element analysis and those measured directly via ex vivo testing of elderly human cadaveric radii [28].

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using JMP 13.0 (SAS Institute, Carry, NC) software. Means and standard deviations (SD) are reported and compared using the Student’s t-test unless data were not normally distributed, in which case the median and interquartile range are reported and the Wilcoxon test was used. A p-value of < 0.05 was used to indicate significance. When assessing the relationship between hormonal parameters (IGF-1 and leptin) and bone parameters (DXA and HR-pQCT parameters), we corrected for multiple comparisons (m=14) using the Bonferroni correction with a level of significance of p ≤ 0.004. As estimates of bone strength (stiffness and failure load) were our primary endpoint, we did not include them when correcting for multiple comparisons. Pearson correlation coefficients (for normally distributed data) or Spearman’s coefficients (for non-normally distributed data) were calculated to assess univariate relationships. Least-squares linear regression modeling was performed to control for confounders.

Results

Clinical characteristics

Clinical characteristics of the study subjects are listed in Table 1. The mean % ideal body weight of subjects with anorexia nervosa (77.6% ± 7.6%) was significantly lower than the % ideal body weight of normal-weight subjects (101.2% ± 5.6%; p<0.0001). BMD at the spine and hip were significantly lower in women with anorexia nervosa as compared to the controls. Subjects with anorexia nervosa also had significantly lower IGF-1 and leptin levels as compared to normal-weight controls.

Table 1:

Clinical characteristics of study subjects

| Anorexia Nervosa (n=19) | Normal-Weight Controls (n=19) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 28.3 ± 4.6 | 27.3 ± 3.4 | 0.47 |

| BMI (kg/ m2)* | 17.7 [15.4, 18.3] | 22.4 [21.8, 23.1] | <0.0001 |

| % Ideal body weight | 77.6 ± 7.6 | 101.2 ± 5.6 | <0.0001 |

| Months of amenorrhea* | 36 [6, 67.5] | ------------ | ------- |

| Duration of anorexia nervosa (years) | 10.4 ± 4.5 | ------------ | ------- |

| Bone mineral density | |||

| Lumbar spine (g/cm2)* | 0.81 [0.72, 0.91] | 0.95 [0.90, 1.07] | 0.0004 |

| Lumbar spine Z-score* | −2.1 [−1.2, −2.9] | −1.1 [0.2, −1.3] | 0.0004 |

| Lateral spine BMD (g/cm2)* | 0.60 [0.56, 0.68] | 0.76 [0.73, 0.85] | <0.0001 |

| Lateral spine Z-score* | −2.6 [−1.7, −2.7] | −0.5 [0.5, −1] | <0.0001 |

| Total hip (g/cm2) | 0.77 ± 0.08 | 0.95 ± 0.11 | <0.0001 |

| Total hip Z-score | −1.4 ± 0.7 | 0.0 ± 0.8 | <0.0001 |

| Femoral neck (g/cm2) | 0.66 ± 0.08 | 0.84 ± 0.12 | <0.0001 |

| Femoral neck Z-score | −1.6 ± 0.7 | −0.2 ± 1.0 | <0.0001 |

| IGF-1 (ng/mL) | 172.3 ± 64.6 | 246.1 ± 63.5 | 0.001 |

| Leptin (ng/mL)* | 1.4 [0.5, 3.9] | 9.4 [5.2, 16.9] | <0.0001 |

Mean ± SD

Median [interquartile range]

Parameters of microarchitecture and estimated bone strength

Parameters of bone microarchitecture and estimated bone strength are listed in Table 2. In the radius, women with anorexia nervosa had significantly less trabecular bone volume fraction (BV/TV), trabecular thickness, and cortical thickness compared to normal-weight controls (p ≤ 0.01 for all) and trabecular separation was significantly greater in women with anorexia nervosa as compared to controls (p=0.03). In the tibia, women with anorexia nervosa had significantly less cortical thickness as compared to normal-weight controls (0.95mm [0.89, 1.16] in anorexia nervosa versus 1.21 mm [1.17, 1.28] in controls; p=0.005) and there was a trend towards decreased trabecular thickness (0.076 mm ± 0.015 in anorexia nervosa versus 0.085 mm ± 0.012 in controls; p=0.05) and decreased trabecular bone volume fraction (0.127% ± 0.043 in anorexia nervosa versus 0.150% ± 0.028 in controls; p=0.06). In both the radius and the tibia, stiffness and failure load -- estimates of bone strength -- were significantly lower in women with anorexia nervosa as compared to normal-weight controls.

Table 2:

Parameters of radial and tibial microarchitecture assessed by high resolution peripheral quantitative CT and estimates of bone strength (microfinite element analysis).

| Anorexia Nervosa (n=19) | Normal-Weight Controls (n=19) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Radial microarchitecture parameters | |||

| Trabecular BV/TV (%) | 0.112 ± 0.035 | 0.142 ± 0.026 | 0.005 |

| Trabecular number (1/mm)* | 1.76 [1.63, 1.96] | 1.93 [1.82, 1.99] | 0.07 |

| Trabecular thickness (mm) | 0.064 ± 0.011 | 0.074 ± 0.012 | 0.01 |

| Trabecular separation (mm)* | 0.521 [ 0.444, 0.545] | 0.455 [ 0.437, 0.477] | 0.03 |

| Cortical thickness (mm)* | 0.70 [ 0.62, 0.77] | 0.81 [ 0.75, 0.87] | 0.01 |

| Radial estimates of strength: | |||

| Stiffness (kN/mm) | 65.2 ± 16.1 | 76.6 ± 13.1 | 0.02 |

| Failure load (kN) | 3.3 ± 0.8 | 3.9 ± 0.6 | 0.02 |

| Tibial microarchitecture parameters | |||

| Trabecular BV/TV (%) | 0.127 ± 0.043 | 0.150 ± 0.028 | 0.06 |

| Trabecular number (1/mm)* | 1.73 [1.47, 1.92] | 1.68 [1.54, 1.91] | 0.52 |

| Trabecular thickness (mm) | 0.076 ± 0.015 | 0.085 ± 0.012 | 0.05 |

| Trabecular separation (mm)* | 0.508 [0.455, 0.600] | 0.521 [0.430, 0.564] | 0.30 |

| Cortical thickness (mm)* | 0.95 [0.89, 1.16] | 1.21[1.17, 1.28] | 0.005 |

| Tibial estimates of strength: | |||

| Stiffness (kN/mm) | 179.5 ±40.6 | 219.7 ± 29.5 | 0.001 |

| Failure load (kN) | 9.1 ± 2.0 | 11.0 ± 1.4 | 0.001 |

Mean ± SD

Median [interquartile range]

Association between IGF-1, leptin and bone parameters

IGF-1 and bone parameters

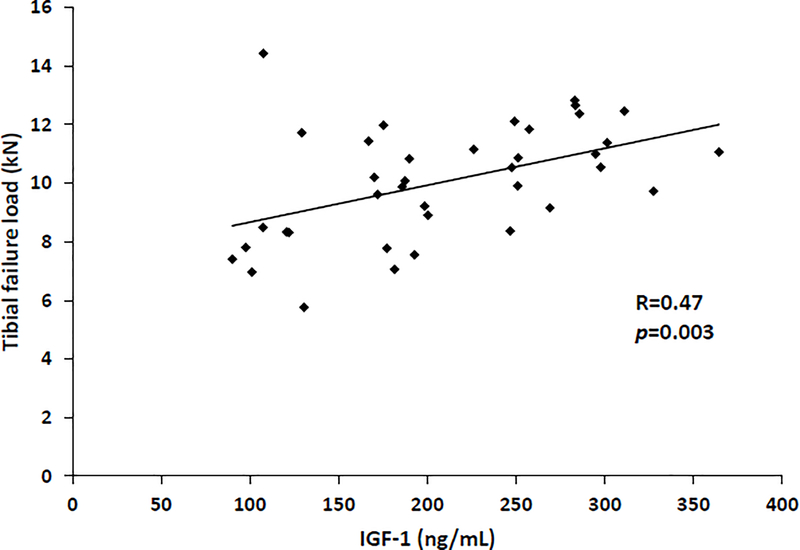

In the group as a whole, IGF-1 was positively associated with BMD at the femoral neck (R=0.55, p= 0.0004) and total hip (R=0.55, p=0.0003). In the group as a whole, IGF-1 was also significantly and positively associated with radial trabecular number (rho=0.53, p=0.0006) and inversely associated with radial trabecular separation (rho= −0.56, p=0.0003). In the tibia, IGF-1 was positively associated with estimates of bone strength: stiffness (R=0.46, p=0.004) and failure load (R=0.47, p=0.003) (Figure 1).

Figure 1:

IGF-1 is positively associated with tibial failure load (R=0.47; p=0.003) in a population of women with anorexia nervosa and normal-weight controls.

In the women with anorexia nervosa (n=19), IGF-1 was significantly associated with BMD at the femoral neck (R=0.74, p=0.0003) and total hip (R=0.71, p=0.0006). In contrast, in the group of normal-weight controls, there were no significant associations between BMD and IGF-1.

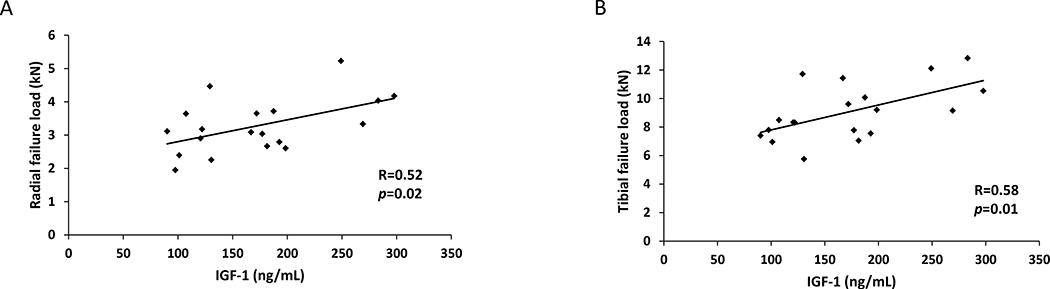

In the women with anorexia nervosa, there were also significant positive associations between IGF-1 and estimates of bone strength in both the radius and tibia. In the radius, stiffness (R=0.52, p=0.02) and failure load (R=0.52, p=0.02) (Figure 2A) were both significantly positively associated with IGF-1 and there was a similar association in the tibia (stiffness: R=0.55, p=0.01 and failure load: R=0.58, p=0.01) (Figure 2B). These results all remained significant after controlling for duration of amenorrhea (p<0.04 for all). When controlling for BMI, the association between IGF-1 and tibial stiffness and failure load remained significant (p≤0.04 for both), whereas the association between IGF-1 and radial stiffness and failure load was not significant and only a trend was noted (p=0.09 for both). In contrast, in the normal-weight controls, there were no significant associations between IGF-1 and stiffness or failure load in the radius or tibia.

Figure 2:

IGF-1 is positively associated with radial failure load (R=0.52; p=0.02) (Panel A) and tibial failure load (R=0.58; p=0.01) (Panel B) in women with anorexia nervosa.

Leptin and bone parameters

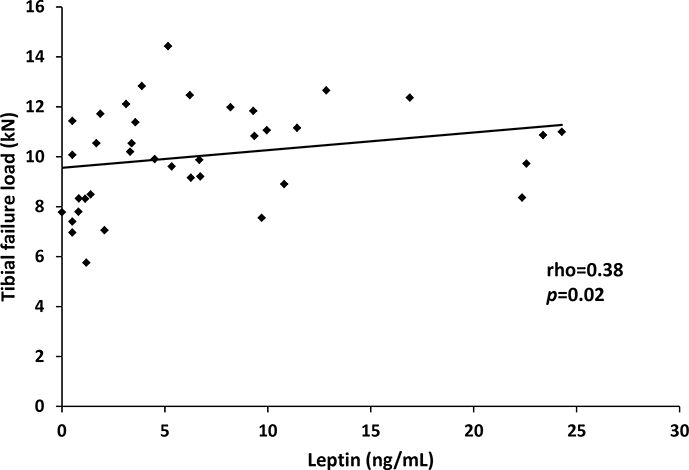

In the group as a whole, leptin was significantly and positively associated with BMD at the lumbar spine (rho = 0.46, p=0.004), lateral spine, (rho=0.64, p<0.0001), total hip (rho = 0.57, p=0.0002) and femoral neck (rho = 0.53, p=0.0006). Leptin was also associated with estimates of bone strength in the tibia: stiffness (rho = 0.38, p=0.02) and failure load (rho = 0.38, p=0.02) (Figure 3). After controlling for amenorrhea, the associations between leptin and stiffness (p=0.98) and failure load (p=0.93) were no longer significant, suggesting that leptin’s association with estimated bone strength is predominantly due to the presence/absence of amenorrhea.

Figure 3:

Leptin is positively associated with tibial failure load (rho = 0.38; p = 0.02) in a population of women with anorexia nervosa and normal-weight controls.

There were no significant associations between leptin and BMD, microarchitectural parameters, or estimated bone strength when analyzing the groups (women with anorexia nervosa and normal-weight controls) separately.

Discussion

We have shown that in women with anorexia nervosa, IGF-1 is significantly and positively associated with stiffness and failure load in the radius and tibia, two estimates of bone strength. Although in a group inclusive of women with anorexia nervosa and normal-weight controls, leptin was positively associated with estimated bone strength in the tibia, when controlling for amenorrhea, the relationship was no longer significant suggesting that estrogen status is a significant determinant of the association between leptin and bone strength.

Approximately 85% of women with anorexia nervosa have bone mineral density values more than one-standard deviation below an age-comparable mean [2]. Importantly, this low bone mass is associated with a significantly increased rate of fractures [2–4]. Over 30% of women with anorexia nervosa report a history of fractures [2]and a prospective study following women ages 19–37 years demonstrated a seven-fold increased risk of non-vertebral fractures compared to women of similar age [3]. Therefore, understanding potential determinants of the increased risk of fracture in anorexia nervosa is critical.

Although BMD is an important predictor of fracture in postmenopausal women, it is not as effective in predicting fracture risk in premenopausal populations, including adolescents with anorexia nervosa. Compared to normal-weight controls, adolescent girls with anorexia nervosa report a 59% higher prevalance of fracture but lower BMD is not associated with prevalence of fracture in this population [5]. Predicting and therefore preventing fracture risk in individuals with anorexia nervosa will therefore require modalities other than DXA.

HR-pQCT allows for the assessment of both trabecular and cortical parameters of bone microarchitecture at the radius and tibia, which have been shown to predict fracture independent of BMD in postmenopausal women [6]. Failure load and stiffness, two estimates of bone strength can be derived from HR-pQCT images using microfinite element analysis and in a postmenopausal population, stiffness and failure load also contribute to fracture risk independently of BMD [7]. Our data confirm prior studies demonstrating that women with anorexia nervosa have impaired bone microarchitecture [29–32]. Although trabecular parameters of microarchitecture were less impaired at the weight-bearing tibia as compared to the radius in our population of women with anorexia nervosa, suggesting that some impairment may be overcome at a weight-bearing site, there was a more significant difference between the groups with respect to estimated bone strength at the tibia as compared to the radius. Therefore, estimated bone strength may potentially be an independent contributor to fracture risk in individuals with anorexia nervosa. Given the increased fracture risk observed in this population compared to normal weight controls [3, 4], further studies will be critical to determine whether bone strength, as estimated by finite element analysis, can aid in the prediction of fracture in women with anorexia nervosa.

To better understand potential determinants of estimated bone strength in anorexia nervosa, we examined the association between estimated bone strength and IGF-1 and leptin, two nutritionally-dependent hormones which have both been associated with low BMD in women with anorexia nervosa [15–17]. We found strong significant associations between IGF-1 and estimated bone strength in both the radius and tibia in women with anorexia nervosa but not in the normal-weight population. This may suggest that there is a threshold effect for IGF-1, such that once a level of “sufficiency” has been achieved, IGF-1 becomes a less important predictor of bone strength. Importantly, IGF-1 has been shown to be a potential determinant of BMD [13] and fractures in healthy postmenopausal women [14] and of vertebral fractures in postmenopausal women with type 2 diabetes mellitus [33]. Therefore, our findings associating IGF-1 and parameters of bone microarchitecture and estimated bone strength in women with anorexia nervosa may have implications for other disease models, including postmenopausal osteoporosis and type 2 diabetes mellitus.

In contrast, although we found strong associations between leptin and tibial bone strength in the group as a whole, in the population of women with anorexia nervosa alone, we did not find a significant association. In fact, when we controlled for amenorrhea, the association between leptin and estimated bone strength lost significance, suggesting that leptin’s association with estimated bone strength is driven mainly by estrogen status. In animal models, leptin appears to have direct anabolic effects on bone [34], but in the model of human starvation, it is possible that leptin’s association with bone may be driven primarily by its effects on the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis, and therefore its effects on estrogen-status. Future studies will be necessary to delineate the direct effects of leptin on bone from those due its effects on the gonadal axis in human models of starvation, as these studies will be of critical importance in understanding the pathophysiology of bone loss in states of chronic undernutrition.

Limitations of our study include our small sample size, which limits our ability to include multiple variables in a regression model, as well as the cross-sectional nature of the study, which does not allow us to assess for causality. Although our sample size was small, the fact that we were able to detect a strong, significant association between IGF-1 and stiffness and failure load in a group of 19 women with anorexia nervosa suggests that IGF-1 is an important determinant of estimated bone strength in this population. Further studies will be necessary to investigate the effects of recombinant human IGF-1 on bone strength and fracture risk in women with anorexia nervosa.

Acknowledgements

We would like to that the nurses and bionutritionists of the MGH Clinical Research Center for their expert care. The project described was supported by NIH grants R24 DK084970 and UL1 1TR002541 (Harvard Clinical and Translational Science Center, from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

This work was supported in part by the following grants from the National Institutes of Health:

UL1 1TR002541

R24 DK084970

Footnotes

Disclosures: Pouneh Fazeli, Alexander Faje, Erinne Meenaghan, Stephen Russell, Megi Resulaj, Hang Lee, Clifford Rosen, Mary Bouxsein and Anne Klibanski declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This Author Accepted Manuscript is a PDF file of a an unedited peer-reviewed manuscript that has been accepted for publication but has not been copyedited or corrected. The official version of record that is published in the journal is kept up to date and so may therefore differ from this version.

References

- 1.American Psychiatric Association (2013) Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-5). 5th edition:Washington, DC [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miller KK, Grinspoon SK, Ciampa J, Hier J, Herzog D, Klibanski A (2005) Medical findings in outpatients with anorexia nervosa. Archives of internal medicine 165:561–566 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rigotti NA, Neer RM, Skates SJ, Herzog DB, Nussbaum SR (1991) The clinical course of osteoporosis in anorexia nervosa. A longitudinal study of cortical bone mass. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association 265:1133–1138 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nagata JM, Golden NH, Leonard MB, Copelovitch L, Denburg MR (2017) Assessment of Sex Differences in Fracture Risk Among Patients With Anorexia Nervosa: A Population-Based Cohort Study Using The Health Improvement Network. Journal of bone and mineral research : the official journal of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research 32:1082–1089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Faje AT, Fazeli PK, Miller KK, et al. (2014) Fracture risk and areal bone mineral density in adolescent females with anorexia nervosa. The International journal of eating disorders 47:458–466 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boutroy S, Bouxsein ML, Munoz F, Delmas PD (2005) In vivo assessment of trabecular bone microarchitecture by high-resolution peripheral quantitative computed tomography. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism 90:6508–6515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boutroy S, Van Rietbergen B, Sornay-Rendu E, Munoz F, Bouxsein ML, Delmas PD (2008) Finite element analysis based on in vivo HR-pQCT images of the distal radius is associated with wrist fracture in postmenopausal women. Journal of bone and mineral research : the official journal of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research 23:392–399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Miller KK, Grinspoon S, Gleysteen S, Grieco KA, Ciampa J, Breu J, Herzog DB, Klibanski A (2004) Preservation of neuroendocrine control of reproductive function despite severe undernutrition. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism 89:4434–4438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Welt CK, Chan JL, Bullen J, Murphy R, Smith P, DePaoli AM, Karalis A, Mantzoros CS (2004) Recombinant human leptin in women with hypothalamic amenorrhea. The New England journal of medicine 351:987–997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Garfinkel PE, Brown GM, Stancer HC, Moldofsky H (1975) Hypothalamic-pituitary function in anorexia nervosa. Archives of general psychiatry 32:739–744 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Counts DR, Gwirtsman H, Carlsson LM, Lesem M, Cutler GB Jr. (1992) The effect of anorexia nervosa and refeeding on growth hormone-binding protein, the insulin-like growth factors (IGFs), and the IGF-binding proteins. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism 75:762–767 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yakar S, Rosen CJ, Beamer WG, et al. (2002) Circulating levels of IGF-1 directly regulate bone growth and density. The Journal of clinical investigation 110:771–781 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Langlois JA, Rosen CJ, Visser M, Hannan MT, Harris T, Wilson PW, Kiel DP (1998) Association between insulin-like growth factor I and bone mineral density in older women and men: the Framingham Heart Study. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism 83:4257–4262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Garnero P, Sornay-Rendu E, Delmas PD (2000) Low serum IGF-1 and occurrence of osteoporotic fractures in postmenopausal women. Lancet 355:898–899 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fazeli PK, Bredella MA, Misra M, Meenaghan E, Rosen CJ, Clemmons DR, Breggia A, Miller KK, Klibanski A (2010) Preadipocyte factor-1 is associated with marrow adiposity and bone mineral density in women with anorexia nervosa. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism 95:407–413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Legroux-Gerot I, Vignau J, Biver E, Pigny P, Collier F, Marchandise X, Duquesnoy B, Cortet B (2010) Anorexia nervosa, osteoporosis and circulating leptin: the missing link. Osteoporosis international : a journal established as result of cooperation between the European Foundation for Osteoporosis and the National Osteoporosis Foundation of the USA 21:1715–1722 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grinspoon S, Miller K, Coyle C, Krempin J, Armstrong C, Pitts S, Herzog D, Klibanski A (1999) Severity of osteopenia in estrogen-deficient women with anorexia nervosa and hypothalamic amenorrhea. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism 84:2049–2055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grinspoon S, Baum H, Lee K, Anderson E, Herzog D, Klibanski A (1996) Effects of short-term recombinant human insulin-like growth factor I administration on bone turnover in osteopenic women with anorexia nervosa. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism 81:3864–3870 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Misra M, McGrane J, Miller KK, Goldstein MA, Ebrahimi S, Weigel T, Klibanski A (2009) Effects of rhIGF-1 administration on surrogate markers of bone turnover in adolescents with anorexia nervosa. Bone 45:493–498 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fazeli PK, Bredella MA, Freedman L, Thomas BJ, Breggia A, Meenaghan E, Rosen CJ, Klibanski A (2012) Marrow fat and preadipocyte factor-1 levels decrease with recovery in women with anorexia nervosa. Journal of bone and mineral research : the official journal of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research 27:1864–1871 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fazeli PK, Faje AT, Cross EJ, Lee H, Rosen CJ, Bouxsein ML, Klibanski A (2015) Serum FGF-21 levels are associated with worsened radial trabecular bone microarchitecture and decreased radial bone strength in women with anorexia nervosa. Bone 77:6–11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fazeli PK, Faje A, Bredella MA, Polineni S, Russell S, Resulaj M, Rosen CJ, Klibanski A (2018) Changes in marrow adipose tissue with short-term changes in weight in premenopausal women with anorexia nervosa. European journal of endocrinology / European Federation of Endocrine Societies [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schorr M, Fazeli PK, Bachmann KN, et al. (2019) Differences in trabecular plate and rod structure in premenopausal women across the weight spectrum. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Frisancho AR, Flegel PN (1983) Elbow breadth as a measure of frame size for US males and females. The American journal of clinical nutrition 37:311–314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Johnson J, Dawson-Hughes B (1991) Precision and stability of dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry measurements. Calcified tissue international 49:174–178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pistoia W, van Rietbergen B, Lochmuller EM, Lill CA, Eckstein F, Ruegsegger P (2002) Estimation of distal radius failure load with micro-finite element analysis models based on three-dimensional peripheral quantitative computed tomography images. Bone 30:842–848 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Macneil JA, Boyd SK (2008) Bone strength at the distal radius can be estimated from high-resolution peripheral quantitative computed tomography and the finite element method. Bone 42:1203–1213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mueller TL, Christen D, Sandercott S, Boyd SK, van Rietbergen B, Eckstein F, Lochmuller EM, Muller R, van Lenthe GH (2011) Computational finite element bone mechanics accurately predicts mechanical competence in the human radius of an elderly population. Bone 48:1232–1238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Milos G, Spindler A, Ruegsegger P, Seifert B, Muhlebach S, Uebelhart D, Hauselmann HJ (2005) Cortical and trabecular bone density and structure in anorexia nervosa. Osteoporosis international : a journal established as result of cooperation between the European Foundation for Osteoporosis and the National Osteoporosis Foundation of the USA 16:783–790 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Walsh CJ, Phan CM, Misra M, Bredella MA, Miller KK, Fazeli PK, Bayraktar HH, Klibanski A, Gupta R (2010) Women with anorexia nervosa: finite element and trabecular structure analysis by using flat-panel volume CT. Radiology 257:167–174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lawson EA, Miller KK, Bredella MA, Phan C, Misra M, Meenaghan E, Rosenblum L, Donoho D, Gupta R, Klibanski A (2010) Hormone predictors of abnormal bone microarchitecture in women with anorexia nervosa. Bone 46:458–463 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Frolich J, Hansen S, Winkler LA, Andresen AK, Hermann AP, Stoving RK (2017) The Role of Body Weight on Bone in Anorexia Nervosa: A HR-pQCT Study. Calcified tissue international 101:24–33 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kanazawa I, Yamaguchi T, Yamamoto M, Yamauchi M, Yano S, Sugimoto T (2007) Serum insulin-like growth factor-I level is associated with the presence of vertebral fractures in postmenopausal women with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Osteoporosis international : a journal established as result of cooperation between the European Foundation for Osteoporosis and the National Osteoporosis Foundation of the USA 18:1675–1681 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Turner RT, Kalra SP, Wong CP, Philbrick KA, Lindenmaier LB, Boghossian S, Iwaniec UT (2013) Peripheral leptin regulates bone formation. Journal of bone and mineral research : the official journal of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research 28:22–34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]