Abstract

Rationale & Objective:

It is relatively unusual for US patients with advanced chronic kidney disease (CKD) to forgo initiation of maintenance dialysis. Our objective was to describe practice approaches of US nephrologists who have provided conservative care for members of this population.

Study Design:

Qualitative study using semi-structured interviews.

Setting & Participants:

A national sample of 21 nephrologists experienced in caring for patients with advanced CKD who decided not to start dialysis.

Analytical approach:

Grounded theory methods to identify dominant themes reflecting nephrologists’ experiences with and approaches to conservative care for patients with advanced CKD.

Results:

Nephrologists who participated in this study were primarily from academic practices (n=14) and urban areas (n=15). Two prominent themes emerged from qualitative analysis reflecting nephrologists’ experiences with and approaches to conservative care: 1) Person-centered practices, which described a holistic approach to care that included basing treatment decisions on what mattered most to individual patients, framing dialysis as an explicit choice, being mindful of sources of bias in medical decision-making and being flexible to the changing needs, values and preferences of patients; and, 2) Improvising a care infrastructure, which described the challenges of managing patients conservatively within health systems that are not optimally configured to support their needs. Participating nephrologists described cobbling together resources, assuming a range of different healthcare roles, preparing patients to navigate health systems in which initiation of dialysis served as a powerful default and championing the principles of conservative care among their colleagues.

Limitations:

The themes identified here likely are not generalizable to most US nephrologists.

Conclusion:

Insights from a select group of US nephrologists who are early adopters of conservative care signal the need for a stronger cultural and health system commitment to building care models capable of supporting patients who choose to forgo dialysis.

Keywords: conservative care, palliative care, end-of-life care, nondialytic care, kidney failure, patient choice, renal supportive care, qualitative research, medical decision-making, chronic kidney disease (CKD), advanced CKD, dialysis initiation, quality of life (QoL), elderly, geriatrics, nephrologist attitudes, hospice, goals of care, patient autonomy, advance care planning (ACP)

Introduction

Patients who reach the advanced stages of chronic kidney disease (CKD) often face decisions about whether and when to initiate treatment with maintenance dialysis. Although dialysis is commonly regarded as a life-prolonging therapy for patients with advanced CKD, it does not always achieve the intended effect of lengthening life and restoring health and quality of life. Especially at older ages, the potential benefits of dialysis in promoting longevity can be quite limited1 and outweighed by the demands and potential burdens and complications of treatment.2–5

In Australia, Canada and several developed countries in Europe and Asia, care processes focused on managing the signs and symptoms of advanced CKD have been created to meet the needs of patients who do not want to start dialysis. Data from some of these programs have suggested that for older adults (aged ≥75 years) with a high burden of comorbidity and functional impairment, whether patients start dialysis or are managed conservatively makes little difference for life-expectancy6–13 and quality of life.14–16 In the US, it is relatively unusual for patients with advanced CKD to choose conservative care,17 and very few dedicated services to support these patients exist in this country.18 Available literature suggests that most US nephrologists have limited experience caring for patients who choose not to start dialysis,19–21 and are not accustomed to offering a conservative option to patients faced with the prospect of kidney failure.22,23 Although there is growing recognition of the importance of conservative care within the US nephrology community,24,25 nephrology training and continuing education programs26 and clinical practice guidelines offer little instruction in this area.27,28

To gain a deeper understanding of emerging approaches to conservative care in the US, we conducted a qualitative study of US nephrologists with experience caring for patients with advanced CKD who had chosen to forgo dialysis.

Methods

Study design

We performed a qualitative study using grounded theory methods. This is a systematic and inductive analytical approach to exploring social processes that enables theoretical concepts about the studied phenomena to be constructed from the source data.29 In grounded theory, data collection and analysis occur simultaneously, and concepts that emerge during analysis are further developed by recursively refining methods to collect subsequent data that elaborate on concepts. This iterative approach allows for generation of explanatory models that are grounded in the empirical data.

Study participants

Given the limited availability of US nephrologists who provide conservative care, 19–23 we elected to use a purposive snowball sampling strategy30,31 that would allow us to target recruitment of nephrologists from across the US experienced with caring for patients with advanced CKD who had decided not to pursue dialysis. Snowball sampling is a method for recruiting hard-to-reach groups that leverages participants’ social and professional networks to identify additional subjects. We developed an initial list of potential US informants for in-depth interviews on conservative care practices based on a literature search of English-language articles and presentations at professional nephrology meetings related to conservative care published between January 2007 and June 2017. To ensure that our study captured the experiences of a representative group of nephrologists within this select group, we recruited nephrologists from a range of geographic regions, practice settings and educational backgrounds. We then asked these informants to nominate colleagues and acquaintances who could provide valuable perspectives on conservative care. We continued to recruit participants and conduct interviews until reaching thematic saturation,31 that is, when no new themes were identified in subsequent interviews. Subjects indicated their informed consent using a web-based consent form. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Washington.

Data collection

Nephrologists were asked to complete a survey that included questions about their demographic characteristics and clinical practice. One investigator (S.P.Y.W.) then conducted either an in-person or phone interview with each participant between November 2017 and June 2018. Interviews were conducted using a semi-structured interview guide designed to elicit information about each nephrologist’s approach to, experiences with and perspectives on caring for patients with progressive advanced CKD who decide to forgo maintenance dialysis. Two authors (S.P.Y.W and R.A.E.) developed the interview guide, which was iteratively refined as interviews were analyzed to enhance the quality and relevance of responses (Item S1). All interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim.

Data analysis

We used open, axial and selective coding methods32 to analyze transcripts. First, two authors (S.P.Y.W. and S.B.) independently reviewed each transcript line-by-line and openly coded for emergent themes related to nephrologists’ experiences and perspectives on conservative care (open coding). The two authors met in-person at regular intervals to review transcripts and codes and appraise the consistency in coding strategies, discrepancies in interpretation of passages, thoroughness in observations and proximity to thematic saturation. After all transcripts were coded, these authors together reviewed all codes and associated quotations to identify relationships, patterns and trends in the data (axial coding). All authors then reviewed the themes, their constituent codes and associated quotations, iteratively refining theme definitions. We recorded analytical and theoretical memos to capture our thinking process and observations of the data. The backgrounds of the authors (nephrology, palliative care, geriatrics, medical anthropology, bioethics) allowed for interpretation of the data from diverse perspectives.31 We selected dominant themes based on the consistency with which these emerged from most or all interviews,33 and assembled themes into a final schema describing conservative care practices (selective coding). We also performed member-checking,31 in which study results were shared with all study participants, and their comments were considered in finalizing the analyses. We used Atlas.ti v.8 to annotate transcripts and organize quotations, codes and memos.

Results

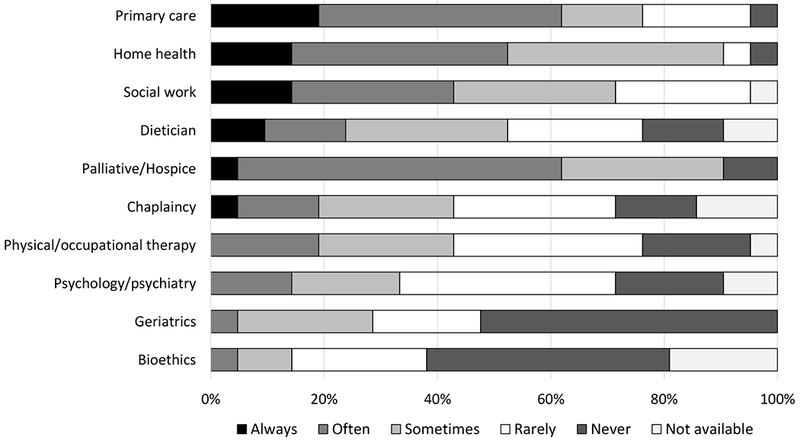

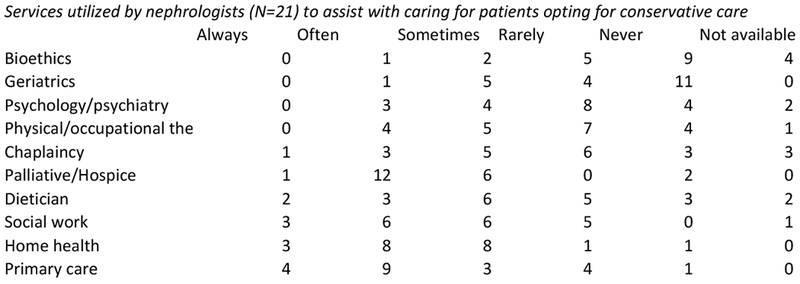

We approached 31 nephrologists, of whom 21 provided informed consent and participated in a semi-structured interview. Mean interview duration was 55.0±8.6 minutes. Study participants practiced in 16 different states and had been in practice for a mean of 20.2 years (Table 1). Most reported that they worked in academic settings (n=14) and urban areas (n=15). Nephrologists reported using ancillary services to varying degrees to assist with caring for patients who opted to forgo initiation of dialysis (Figure 1). The most commonly used services included primary care, home health, social work, nutrition, palliative care and/or hospice and chaplaincy.

Table 1.

Nephrologist characteristics

| Characteristic | Value |

|---|---|

| Age, years | 47.7 +/− 14.3 |

| Duration in clinical practice, years | 20.2 +/− 14.6 |

| No. of states represented | 16 |

| No. of unique practices represented | 19 |

| Male sex | 62 (13) |

| Race, % (n) | |

| White | 67 (14) |

| Black | 5 (1) |

| Asian | 24 (5) |

| Mixed | 5 (1) |

| Other professional training, % (n) | |

| Palliative care and/or hospice | 43 (9) |

| Bioethics | 5 (1) |

| Practice type, % (n) | |

| Academic | 67 (14) |

| Private solo | 0 |

| Private group | 10 (2) |

| Private multi-specialty group | 14 (3) |

| Other | 10 (2) |

| Urban (vs rural) practice setting | 71 (15) |

| No. of patients seen per month, % (n) | |

| <50 | 38 (8) |

| 50-100 | 24 (5) |

| 100-150 | 14 (3) |

| 150-200 | 10 (2) |

| >200 | 10 (2) |

| No. of conservatively managed patients in entire career, % (n) | |

| <10 | 33 (7) |

| 10-20 | 19 (4) |

| 20-30 | 14 (3) |

| >30 | 33 (7) |

Figure 1.

Services utilized by nephrologists (N=21) to assist with caring for patients opting for conservative care

Two dominant and inter-related themes emerged from qualitative analysis reflecting participants’ approaches to conservative care: 1) a person-centered approach to care; and, 2) improvising a care infrastructure. Exemplary quotes illustrating each theme are provided in Boxes 1–2.

Box 1. Person-centered care: Exemplar quotes from interviews.

Patient-centered decision making

Quote 1:

“I try to talk to [patients], let them know I see them as people, not cases. I try to let them see me as people and not some kind of omnipotent problem-solver. We try to establish a human rapport, and basically, the message is, “you’re in a pickle, you’ve got to decide what’s important to you, and I’ll try to help you get whatever we can.”” – Nephrologist 13

Quote 2:

“I really try to start out with learning who [patients] are and what their experience has been and how they see their health…I really dive into it from a values-based conversation and learn about them, learn about their values and then incorporate that into thinking about treatment” – Nephrologist 5

Quote 3:

“I don’t present the medical facts to the patients and ask them to play doctor. I try and distill it down for them…I say something like, “Can you help me decide, figure out how to take care of you? I’m a little bit confused about whether or not we should start xyz medicine. I think it could help you with your fatigue, your hemoglobin’s very low, but it requires you to give yourself an injection. What do you think?” ” – Nephrologist 1

Quote 4:

“Most decisions I make for a person receiving conservative care maybe fit in 1 of 2 categories: How do I keep them safe?…[W]hat can I do to help them maintain their current quality of life along the lines of their goals of care? ” – Nephrologist 17

Quote 5:

“for many patients it’s not particularly positive to continually harp on them like, “So you’re not going to do dialysis?”…To continually bring up death and what this decision is, instead of saying, “we’re supporting you with medical management of kidney disease, and there may be ultimately a time where we transition to hospice. Right now, we’re focusing on your symptom burden.” ” – Nephrologist 11

Presenting dialysis as a choice

Quote 6:

“I say, “There’s no law to have dialysis, it’s a choice, it’s a treatment you can choose to have but you don’t have to have it…” [S]ome people who are thinking that they want dialysis aren’t deterred. For people who don’t want it, they feel that I’m supporting them in giving them permission to follow their instincts. ” – Nephrologist 10

Quote 7:

“for patients who aren’t sure and even for patients who just don’t want to go to dialysis at all, I try to get all of them to go the dialysis education programs…so that they can see what they’re deciding not to do…But often times they’re like, “Oh yeah, that’s not for me. I don’t want to do that. I don’t think that’s how I want to spend the rest of my life. I appreciate you for offering it but I would like to take the other road.” ” – Nephrologist 18

Quote 8:

“I always include when I discuss dialysis, “And there are people that decide that they just don’t want dialysis and if you choose that”--and they’ll ask me--”what does that look like?” I’ll talk about it with them. ” – Nephrologist 12

Quote 9:

“I probably don’t explicitly discuss the option of not doing dialysis in all circumstances, and that may be because, in some cases, it seems very clear that the patient’s very set in their goals and preferences, and the treatment decision seems consistent with their overall goals of care and prognosis. ” – Nephrologist 15

Quote 10:

“the approach that I hear [other providers] do often is “You’re going to die without dialysis. You can do conservative care but you’re going to die without dialysis.” I don’t present it like that…it’s more of a skewed presentation that dialysis is the right answer…That’s not really empowering the patient or family in making a decision for conservative management…[R]ather, “this is an appropriate treatment for many people and they can have good lives, feel well for a portion of that life, and we continue to actively take care of you.” ” – Nephrologist 4

Having insight into own biases

Quote 11:

“The [cases] that are difficult are the ones that have potential for a good life [on dialysis]…In general, whether I agree or disagree with a decision the patient’s made, once they make the decision, I am usually able to separate my own personal feelings and just kind of go along with it. ” – Nephrologist 6

Quote 12:

“I felt like there was a larger thing kind of tying us together, that she wanted me there for the process…. It’s gratifying that she was able to go the way that she wanted to go…[A] part of me really wanted her to try dialysis to prove that I can make it better for her…And so recognizing that that’s not what this is about, that it’s not about me, it’s about what she wants. ” – Nephrologist 12

Quote 13:

“autonomy is the most important ethical principal and that a patient has an absolute right to refuse any treatment. Absolute, as long as they are capable of understanding what’s being told to them, deliberating the different courses and making a decision. ” – Nephrologist 14

Need for flexibility

Quote 14:

“ [Nephrologists] are like, “Oh yeah, I did conservative care and then they changed their mind”…[W]e beat ourselves up when things don’t go the way we thought it was going to go…I try to normalize it…I always tell them that this is a decision that can change over time. I got patients that I’ve done a Physician Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatment forms with three times because they wanted to make little tweaks or they made a change in their thinking…[T]his is an evolving process” – Nephrologist 5

Quote 15:

“ [The patient] said, “I don’t want to do dialysis,” and the whole family was in shock…[T]hey talk about it [and] he’s like, “well, okay, fine, I’ll do dialysis.” He gets a fistula, it’s mature, it’s ready to go, then he doesn’t want to do dialysis. So this is a back and forth situation…[I]n this particular patient, you just kind of talk about it every time…you just have to roll with it. ” – Nephrologist 21

Quote 16:

“ [Caring for patients who forgo dialysis] is really hard for me to protocolize and that’s why I think it’s so great. It’s really so individualized and very, very dynamic…[Y]ou don’t know where patients or families are going to be when they come in to you, so it’s a little bit hard to plan it out. ” – Nephrologist 8

Quote 17:

“I really want the patient to be engaged in this process…the answer is really to be flexible, just acknowledge that this is real life playing out. It’s not just these patients don’t read a textbook or they’re not on pathways necessarily, even though we doctors may like to think we’ve put our patients on pathways, that’s comforting to us. That’s not necessarily how their lives play out. ” – Nephrologist 1

Box 2. Improvising a care infrastructure: Exemplar quotes from interviews.

Defining scope of responsibility

Quote 18:

“I’ve been in the room with my colleague, the patient, and the wife, and have been involved in that initial conversation. I’ve had colleagues refer patients to me to discuss conservative care without them being present but just with the patient and family. I’ve had colleagues who have had that conversation without me and then they transition the patient to me to follow. Sometimes the primary nephrologist would see the patient and then I would see them afterwards and check in on how things were going, check in on symptoms, and try to continue conversations about advanced care planning and things along that nature. It really depended on the provider and how comfortable the provider was with conservative therapy. ” – Nephrologist 4

Quote 19:

“I was the touchy-feely nephrologist…Whenever a patient was doing poorly and the staff thought they need to have a family conference, they’d ask me to do it even if it wasn’t my patient per se…I was willing to do that whereas my colleagues were less comfortable in that role. ” – Nephrologist 7

Quote 20:

“At [a prior medical center], I was only doing palliative care so I really tried to wear that hat, especially because I didn’t want to infringe upon anybody. They have their practicing nephrologist. ” – Nephrologist 8

Quote 21:

“He initially saw me in my kidney clinic and then transitioned over to [my palliative care clinic], more for practical purposes because I can do some home-based palliative care there…[S]ome of the consults I get on the palliative care side are for primary palliative care, and I get why that happens, because there’s so many other demands on a nephrologist’s time, maybe they don’t have the cognitive and mental, emotional, spiritual space to do that. ” – Nephrologist 2

Filling gaps in care

Quote 22:

“one of the challenges to medical management of kidney disease is that it really in my mind requires frequent visits …[T]hat’s how I keep my late stage sick people out of the hospital. There are practices that are not built for that…[A] nurse practitioner, a social worker and a dietician, we definitely don’t have that set up” – Nephrologist 11

Quote 23:

“If that patient gets admitted or ends up in the care of someone else in a healthcare system that’s not set up to deal with this kind of care, it feels very disorienting to [the patient]…the health care system is designed to treat with dialysis. That is the default pathway in this country, by far. ” – Nephrologist 1

Quote 24:

“I have not found home hospice to meet my patients’ needs as much as I had hoped. As a result of that, I’ve been referring patients to inpatient hospice…I just haven’t felt that they were responsive to my patients’ needs or perhaps knowledgeable about how to manage terminal uremia” – Nephrologist 15

Quote 25:

“The problem is that hospice will not take him as long as he’s getting intravenous infusions. Because of this high output ileostomy, he would not survive more than a couple weeks without the infusions. With the infusions, if I look at the rate of decline of renal function, he might live another six months or a year. ” – Nephrologist 6

Quote 26:

“I give patients my card, it has my cell phone and my home phone on it, and I tell them that they can call…The mechanics of doing the best I can are difficult but doing the best I know how. ” – Nephrologist 10

Quote 27:

“Phone calls, daily phone calls. Being available for them to call me. Being available and not just 9:00 - 17:00 on weekdays. I’m being available to talk through [a crisis]. ” – Nephrologist 18

Quote 28:

“I just stayed with [the patient] and gave him morphine until he stopped breathing…I try to be the one who is there at the bedside, not the nurse, not somebody who the patient didn’t know. ” – Nephrologist 14

Guarding against the greater healthcare system

Quote 29:

“I’m thinking about the situations that end up in the emergency room where someone is potentially going to do something to them that they don’t want or do something in a hurry, and they won’t feel like they’re able to advocate for themselves…So really that process of preparing them as best as possible…Sometimes I just say… “this is what that might look like If we want to know what your symptoms are so that we can give you or your family member the tools to address those symptoms. There’s a phone number you can call for a nurse instead of calling 911.” ” – Nephrologist 9

Quote 30:

“ [Patient] was old and fragile and quite explicit in her desire not to do dialysis…Then she had gone down to visit other kids in [city], and they had gotten worried about her and dragged her off to the emergency department, and they put her on dialysis without discussing it with her at all…[Her granddaughter] was most upset about the fact that the folks down there hadn’t made any effort to find out if there was plan. They just did their thing. ” – Nephrologist 13

Quote 31:

“a lot of it has been helping them feel confident about their decision, affirming it…the way that I empower them is I reinforce why we’re doing what we’re doing, that this is all about them and what it’s important to them. I find that that’s very helpful beyond the point of saying, “If you get to the hospital, please call us so we can protect you”.” – Nephrologist 5

Quote 32:

“You have to involve other palliative care teams, other members within the care team, either intensivists or whoever is involved, or other people who’ve known patients for longer…[A]t the end of the day, when everyone was on the same page, I felt like I was doing the patient right. ” – Nephrologist 21

Challenging norms

Quote 33:

“there were a couple times when one of my colleagues would come to me and talk about a patient who chose not to go on dialysis. He just wanted to make sure that he had covered all the bases. Was the patient educated, etc., about it?…I think he was looking for reassurance, like… “Can I run this by you?” ” – Nephrologist 7

Quote 34:

“I have another patient who is 89 who never wanted dialysis and she was actually a really functional 89. Some of my colleagues were like, “really, you’re not dialyzing her?”… I mean a lot of it is done jokingly…That never feels good. ” – Nephrologist 8

Quote 35:

“I got a phone call from a cardiologist about two or three weeks ago. He wanted to talk to me about doing all these procedures, and why I didn’t want to do [dialysis]. I already talked to the patient about the stuff beforehand, so I told him over the telephone what I thought and then what I recommended and what the patient had told me. What he didn’t tell me is that he had me on speaker phone, and the patient and his wife were sitting there…And of course the patient got a little concerned…[the cardiologist] was hell bent on doing his thing, and he was going to try and run all over me. ” – Nephrologist 13

Quote 36:

“nephrologists put people onto dialysis to extend life, to be proceduralists, to treat patients in this particular way. [I]n caring for patients who don’t want to do dialysis, it can feel conflicting with the way in which we grew up in nephrology…I don’t want to be known as the doctor that encourages death, because that’s not the case. ” – Nephrologist 9

Quote 37:

“A lot of us are cognizant of whether our practice patterns fall within institutional norms or outside of institutional norms. I do think there are really strong pressures to ensure that your practice does not fall too far outside of institutional norms. I think that is tied to the issue of validating a treatment decision. ” – Nephrologist 15

Quote 38:

“I give biannual talks on some sort of palliative care issue related to communities, and most [nephrologists and nurses] attend those so I think that they passively hear that information…I sometimes send articles to our team…I should probably do a better job of trying to help educate our palliative care team” – Nephrologist 19

Quote 39:

“I get positive reinforcement from patients and families…from the nephrologists in my group and the nurses, and from people in the hospital and other people from other departments, other disciplines. It does matter to me that they think that this is a decent and humane and appropriate way to take care of people. ” – Nephrologist 10

Person-centered care

Participants described adopting a person-centered approach to caring for patients with advanced CKD that involved orienting decisions to what matters most to each patient, framing dialysis as an explicit treatment choice, being mindful of sources of bias in medical decision-making and being flexible in accommodating patients’ changing needs, values and preferences (Box 1).

Patient-centered decision-making

The nephrologists whom we interviewed tended to view decisions about dialysis within the broader context of patients’ goals and values rather than based on conventional biomarkers of kidney disease. They reported engaging patients in a process of relationship building and getting to know them as “people” (quote 1). What participants learned about their patients through these conversations then shaped how they framed discussions about treatment options for advanced CKD and the future course of illness (quote 2). They described helping their patients reason through what might be the right decision for them, and placed more emphasis on the process of supporting patients’ choices than on what treatments they ultimately chose (quote 3). Consistent with this approach, study participants looked to their patients to determine what was important to them in formulating treatment targets (quote 4). While most recognized the importance of having ongoing conversations with patients about their values and goals, they were also mindful of not wanting this to be burdensome for patients, and some were careful not to repeatedly question patients about their treatment preferences unless they expressed ambivalence (quote 5).

Presenting dialysis as a choice

The nephrologists with whom we spoke emphasized the importance of presenting dialysis as an explicit treatment “choice” (quote 6). This included ensuring that patients were informed about the benefits and harms of treatment and understood that they could decline this treatment (quote 7). Participants described different strategies for bringing up the option of forgoing dialysis. Some presented this option routinely to all patients alongside other treatment options like dialysis and kidney transplantation (quote 8). Others were more selective, bringing this up only with select patients based on their sense of who might prefer or benefit from a more conservative approach (quote 9). Additionally, most tried to frame the option of not doing dialysis in a positive light and described choosing their words carefully (quote 10). Several participants described how terms such as “allowing a natural death,” “not being dependent on machines” or “active treatment,” could elicit different reactions from patients.

Having insight into own biases

While the nephrologists interviewed for this study reported being supportive of patients’ decisions to forgo dialysis, some spoke of how they did not always agree with these decisions (quote 11). Accepting patients’ decision to forgo dialysis was especially difficult when they thought patients might benefit from dialysis (e.g. younger patients and potential kidney transplant candidates). Nonetheless, participants described setting aside their own personal preferences (quote 12) in order to uphold patient autonomy (quote 13).

Need for flexibility

Study participants spoke of a common experience of caring for patients who initially refused dialysis but then later changed their minds (quote 14) and vice versa (quote 15). Most participants did not seem to view this as problematic, seeing their role as supporting patients over the course of their illness by making ongoing adjustments to patients’ care plans to accommodate their evolving illness experience and changing goals and preferences (quote 16). They noted that this kind of flexibility was not easily accommodated within care pathways that were exclusively focused on either preparation for dialysis or conservative care (quote 17).

Improvising a care infrastructure

All of the nephrologists whom we interviewed spoke of how the health systems within which they practiced did not readily accommodate patients who did not want to pursue dialysis. They described serving in a range of different roles and cobbling together existing resources in order to support their patients. They also described strategies to assist patients with navigating the strong tendency of providers and health systems to default to dialysis and to champion conservative care among their colleagues.

Defining scope of responsibility

While all of the nephrologists enrolled in this study had direct experience caring for patients who had chosen to forgo dialysis, some also served in an informal or formal consultative role within renal and/or palliative care clinics. As consultants, their responsibilities could vary from advising other clinicians to co-managing patients with their primary nephrologists on a variety of issues including complex medical decision-making, advance care planning, and symptom management (quote 18). The level of consultants’ involvement seemed to be largely shaped by the needs and attitudes of their colleagues (quotes 19 & 20). Whether consultants were based in renal or palliative care clinics seemed to be primarily related to which clinic was better resourced to support their role and services (quote 21).

Filling gaps in care

All of the nephrologists interviewed described being committed to caring for patients for the duration of their illness and emphasized the importance of not “abandoning” patients simply because they had chosen to forgo dialysis. Nevertheless, the nephrologists in this study voiced frustration regarding the lack of support systems to assist with conservative care (quote 22). Few had colleagues who had enough experience with conservative care to be able to provide clinical back-up or share off-hours responsibilities and vacation coverage. Most were reluctant to rely on urgent care or emergency room services because of concern that patients might be started on dialysis by clinicians who were unfamiliar or uncomfortable with conservative strategies (quote 23). Many nephrologists in this study also spoke of the challenges of working collaboratively with hospice agencies. They expressed concern about the restrictions that these agencies placed on the use of expensive medications for kidney disease (e.g. erythropoiesis-stimulating agents for anemia) and noted that hospice staff usually had limited experience with managing uremic symptoms (quote 24) and could be hesitant to combine disease-modifying treatments with those directed at palliation (quotes 25). In response to perceived gaps in care, participants described using telemedicine and home health services to extend their reach. Many spoke of how they provided patients with their personal phone numbers (quote 26) and/or kept their pagers on so they could be contacted for acute issues (quotes 27). Some reported making home calls and/or assuming the role of hospice physician to patients nearing death (quote 28).

Interfacing with the wider healthcare system

The nephrologists whom we interviewed spoke of how clarifying patients’ preferences alone did not guarantee that they would receive the kind of care that they desired. Therefore, explicit strategies were developed to help patients ensure that their wishes were upheld when interacting with the wider healthcare system. These included educating patients about the signs and symptoms that they might develop and helping them to formulate a plan of action in the event of a health crisis (quote 29). Our respondents emphasized the importance of documenting patients’ decision to forgo dialysis in the medical record and reported that they routinely completed advance directives and portable medical/physician orders for life-sustaining treatment forms. However, some described instances in which this kind of documentation might either be overlooked or difficult to access in a crisis (quote 30). To handle these kinds of situations, some nephrologists described coaching patients on how to voice their preferences and communicate with other clinicians who might not be familiar with their goals (quote 31). They also worked to build consensus among other clinicians and family members around supporting patients’ treatment preferences in order to increase the likelihood that patients’ wishes would be respected (quote 32).

Challenging norms

Study participants reported varied interactions with colleagues, some of whom were supportive of their work and looked for opportunities to leverage their skills (quote 33), while others were resistant or even reproachful (quote 34). Several participants provided examples of how their efforts to uphold patients’ wishes not to initiate dialysis had been deliberately ignored or undermined by colleagues (quote 35). Many felt as though their approach to care was outside the range of usual nephrology practice (quote 36) and described social pressure to bring their practice into line with that of their colleagues (quote 37). They also described consciously trying to build support for conservative care among their colleagues and staff with varying degrees of success (quote 38). To improve their practice and gain reassurance about their approach to caring for patients, many described seeking support from colleagues at other institutions more familiar with conservative care (quote 39).

Discussion

It is relatively unusual for US patients with advanced CKD to choose not to pursue dialysis, and conservative care practices in the US have generally lagged behind those in place in other developed countries. When we spoke with a select group of nephrologists who are early adopters of conservative care in the US, common themes emerged around formulating person-centered practices and improvising a care infrastructure to support the needs of patients who had chosen not to pursue dialysis.

Nephrology clinical practice guidelines tend to focus largely on slowing progression of kidney disease, minimizing disease complications, and extending life.28 While dialysis is often initiated with these goals in mind, they do not have universal significance to all patients.34,35 Prior qualitative studies highlight that while clinicians may think they have their patients’ best interests at heart, their recommendations to start dialysis may conflict with patients’ own expressed goals and preferences.17,20 The nephrologists interviewed for this study described adopting a person-centered approach to care that is in many ways antithetical to the traditional disease-based framework that characterizes much of nephrology practice.36 Many consciously developed treatment plans that aligned with what patients considered most important and trusted that patients knew what was best for themselves. It is therefore not surprising that many of the nephrologists in this study felt that they were working at the margins of mainstream nephrology practice and the wider health system.

While the nephrologists interviewed for this study saw the importance of offering conservative care and supporting patients’ decisions not to pursue dialysis, studies conducted among the wider US medical community suggest that this is a relatively uncommon approach to care. Prior qualitative work indicates that some nephrologists feel they have little to offer patients who would not be starting dialysis and “sign off’ from patients’ care,20 while others equate conservative care to “giving up” or “no care.”22 Survey results of primary care physicians also support that many deliberately do not seek input from nephrologists in decisions to forgo dialysis.21 In contrast, the nephrologists in this study described adopting different healthcare roles, acquiring skills in symptom management and advance care planning and finding ways to extend their reach beyond the conventional clinic model to meet the needs of patients who had chosen not to undergo dialysis. While more research is needed to determine the acceptability, scalability, and outcomes of the approaches described by the nephrologists in this study, our findings offer insights into the kinds of cultural and practice changes that would likely be needed to support more widespread delivery of conservative care.

In other developed countries, established conservative care programs typically entail a multidisciplinary plan of care that provides medical, psychosocial, and caregiver support to patients who choose to forgo dialysis. In many such programs, these patients enter a specific “care pathway” that offers services distinct from those offered to patients preparing for dialysis.7,12,37–44 While this kind of organization of care has been successful in other countries, it is unclear whether a similar approach can meet the needs of US patients. None of the nephrologists whom we interviewed described having had the benefit of an infrastructure to support the delivery of conservative care, and they often had to be creative in supporting their patients. It is also unclear whether care models that require patients to be proactive in deciding on conservative care vs. dialysis would meet the needs of these patients as many of the nephrologists in this study spoke of the importance of flexibility in supporting patients’ changing goals throughout the course of illness rather than advocating for a particular course of treatment. This finding resonates with those of prior qualitative studies demonstrating that US patients with advanced CKD can be ambivalent about whether they would want dialysis and have difficulty making this decision until they are faced with a crisis.45–48 Ideally, care plans for US patients with advanced CKD would need to be responsive to the changing realities of patients’ experience of illness20,45,49–51 and preserve capacity to provide “the right treatment to the right patient at the right time.”52 Collectively, these findings highlight the need for an explicit infrastructure to not only support the care of patients who have decided to forgo dialysis but also allow flexibility to accommodate those who are undecided.

This study has several limitations. First, because our goal was to learn about the experiences of nephrologists who are at the forefront of developing these practices, we purposively recruited subjects who were most likely to have experience with conservative care. Although we recruited nephrologists from across the US, this is not a representative sample of US nephrologists and likely does not reflect practices in the wider nephrology community. Specifically, many of the nephrologists with whom we interviewed had received formal training in palliative care, and their practices may in part reflect those advocated in the field of palliative medicine. Second, we sought to identify dominant themes reflecting approaches to conservative care relevant to most or all members of this select group with diverse experiences providing this care. We did not sample for nephrologists in such a way as to learn about divergent practices between particular subgroups. In presenting only dominant themes, our findings also do not reflect all the facets of caring for members of this population. Lastly, our results are based on self-reported practices. Because we did not enroll the patients of nephrologists in this study, we do not know to what extent self-reported practices reflect actual practices and how the care described was perceived by their patients.

In conclusion, interviews conducted with a select group of US nephrologists who are early adopters of conservative care suggest that far-reaching cultural, practice, and infrastructural changes would be needed to support more widespread delivery of conservative care in this country and the diverse needs and changing goals of US patients with advanced CKD.

Supplementary Material

Item S1. Interview guide.

Acknowledgments

Support: This work was supported by a grant from National Institutes of Health (1K23DK107799-01A1, PI Wong) which had no role in the study design; collection, analysis and interpretation of data; writing the report; and the decision to submit the report for publication.

Financial Disclosure: In the past three years, Dr. Wong has received teaching honoraria from VitalTalk. Dr. Wong also receives funding from the National Palliative Care Research Center and the VA National Center for Healthcare Ethics. Dr. Thorsteindottir is supported by a grant from the National Institute on Aging (K23AG051679). Dr. O’Hare reports personal fees from University of Pennsylvania, University of Alabama, Hammersmith Hospital, the Society of Dialysis Therapy, Chugai Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd, Kaiser Permanente of Southern California, UpToDate, Fresenius Medical Care, Dialysis Clinic, Inc. and grant support from VA Health Services Research and Development, the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Disorders and the Centers for Disease Control outside the submitted work. The remaining authors declare that they have no relevant financial interests.

Footnotes

Supplementary Material Descriptive Text for Online Delivery

Supplementary File (PDF). Item S1.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Susan P. Y. Wong, Kidney Research Institute, University of Washington, Health Services Research and Development Center, VA Puget Sound Health Care System, 1660 S. Columbian Way, Building 100, Renal Dialysis Unit, Seattle, WA 98108.

Saritha Boyapati, Division of Nephrology, University of Washington.

Ruth A. Engelberg, Division of Pulmonary, Critical Care and Sleep Medicine, University of Washington, Cambia Palliative Care Center of Excellence, University of Washington.

Bjorg Thorsteindottir, Mayo Clinic College of Medicine.

Janelle S. Taylor, Department of Anthropology, University of Washington.

Ann M. O’Hare, Kidney Research Institute, University of Washington, Health Services Research and Development Center, VA Puget Sound Health Care System.

References

- 1.Kurella Tamura M, Desai M, Kapphahn KI, Thomas IC, Asch SM, Chertow GM. Dialysis versus Medical Management at Different Ages and Levels of Kidney Function in Veterans with Advanced CKD. J Am Soc Nephrol 2018;29(8):2169–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jassal SV, Chiu E, Hladunewich M. Loss of independence in patients starting dialysis at 80 years of age or older. N Engl J of Med 2009;361(16):1612–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kurella Tamura M, Covinsky KE, Chertow GM, Yaffe K, Landefeld CS, McCulloch CE. Functional status of elderly adults before and after initiation of dialysis. N Engl J Med 2009;361(16):1539–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Montez-Rath ME, Zheng Y, Tamura MK, Grubbs V, Winkelmayer WC, Chang TI. Hospitalizations and Nursing Facility Stays During the Transition from CKD to ESRD on Dialysis: An Observational Study. J Gen Intern Med 2017;32(11): 1220–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wong SP, Kreuter W, O’Hare AM. Healthcare intensity at initiation of chronic dialysis among older adults. J Am Soc Nephrol 2014;25(1):143–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Murtagh FE, Marsh JE, Donohoe P, Ekbal NJ, Sheerin NS, Harris FE. Dialysis or not? A comparative survival study of patients over 75 years with chronic kidney disease stage 5. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2007;22(7):1955–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smith C, Da Silva-Gane M, Chandna S, Warwicker P, Greenwood R, Farrington K. Choosing not to dialyse: evaluation of planned non-dialytic management in a cohort of patients with end-stage renal failure. Nephron Clin Pract 2003;95(2):c40–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chandna SM, Da Silva-Gane M, Marshall C, Warwicker P, Greenwood RN, Farrington K. Survival of elderly patients with stage 5 CKD: comparison of conservative management and renal replacement therapy. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2011. ;26(5):1608–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Verberne WR, Geers AB, Jellema WT, Vincent HH, van Delden JJ, Bos WJ. Comparative Survival among Older Adults with Advanced Kidney Disease Managed Conservatively Versus with Dialysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2016;11(4):633–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shum CK, Tam KF, Chak WL, Chan TC, Mak YF, Chau KF. Outcomes in older adults with stage 5 chronic kidney disease: comparison of peritoneal dialysis and conservative management. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2014;69(3):308–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rouveure AC, Bonnefoy M, Laville M. Conservative treatment, hemodialysis or peritoneal dialysis for elderly patients: The choice of treatment does not influence the survival [French]. Nephrol Ther 2016;12(1):32–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hussain JA, Mooney A, Russon L. Comparison of survival analysis and palliative care involvement in patients aged over 70 years choosing conservative management or renal replacement therapy in advanced chronic kidney disease. Palliat Med 2013;27(9):829–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kwok W-H, Yong S-P, Kwok O-L. Outcomes in elderly patients with end-stage renal disease: Comparison of renal replacement therapy and conservative management. Hong Kong Journal of Nephrology 2016;19:42–56. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Da Silva-Gane M, Wellsted D, Greenshields H, Norton S, Chandna SM, Farrington K. Quality of life and survival in patients with advanced kidney failure managed conservatively or by dialysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2012;7(12):2002–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yong DS, Kwok AO, Wong DM, Suen MH, Chen WT, Tse DM. Symptom burden and quality of life in end-stage renal disease: a study of 179 patients on dialysis and palliative care. Palliat Med 2009;23(2): 111–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Seow YY, Cheung YB, Qu LM, Yee AC. Trajectory of quality of life for poor prognosis stage 5D chronic kidney disease with and without dialysis. Am J Nephrol 2013;37(3):231–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wong SP, Hebert PL, Laundry RJ, et al. Decisions about Renal Replacement Therapy in Patients with Advanced Kidney Disease in the US Department of Veterans Affairs, 2000-2011. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2016;11(10):1825–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Scherer JS, Wright R, Blaum CS, Wall SP. Building an Outpatient Kidney Palliative Care Clinical Program. J Pain Symptom Manage 2018;55(1):108–116. e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Parvez S, Abdel-Kader K, Pankratz VS, Song MK, Unruh M. Provider Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices Surrounding Conservative Management for Patients with Advanced CKD. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2016;11(5):812–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wong SPY, McFarland LV, Liu CF, Laundry RJ, Hebert PL, O’Hare AM. Care practices for patients with advanced kidney disease who forgo maintenance dialysis. JAMA Intern Med 2019; doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.6197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sekkarie M, Cosma M, Mendelssohn D. Nonreferral and nonacceptance to dialysis by primary care physicians and nephrologists in Canada and the United States. Am J Kidney Dis 2001;38(1):36–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ladin K, Pandya R, Kannam A, et al. Discussing Conservative Management With Older Patients With CKD: An Interview Study of Nephrologists. Am J Kidney Dis 2018; 71(5):627–635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grubbs V, Tuot DS, Powe NR, O’Donoghue D, Chesla CA. System-Level Barriers and Facilitators for Foregoing or Withdrawing Dialysis: A Qualitative Study of Nephrologists in the United States and England. Am J Kidney Dis 2017;70(5):602–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.O’Hare AM, Song MK, Kurella Tamura M, Moss AH. Research Priorities for Palliative Care for Older Adults with Advanced Chronic Kidney Disease. J Palliat Med 2017;20(5):453–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.O’Hare AM, Armistead N, Schrag WL, Diamond L, Moss AH. Patient-centered care: an opportunity to accomplish the “Three Aims” of the National Quality Strategy in the Medicare ESRD program. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2014;9(12):2189–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Combs SA, Culp S, Matlock DD, Kutner JS, Holley JL, Moss AH. Update on end-of-life care training during nephrology fellowship: a cross-sectional national survey of fellows. Am J Kidney Dis 2015;65(2):233–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes. KDIGO 2012 Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Evaluation and Management of Chronic Kidney Disease. Kidney Int 2012;3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.National Kidney Foundation. KDOQI Clinical Practice Guideline for Hemodialysis Adequacy: 2015 update. Am J Kidney Dis 2015;66(5):884–930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Corbin JSA. Basics of qualitative research: techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. London: SAGE Publications; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sadler GR, Lee HC, Lim RS, Fullerton J. Recruitment of hard-to-reach population subgroups via adaptations of the snowball sampling strategy. Nurs Health Sci 2010;12(3):369–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Giacomini MK, Cook DJ. Users’ guides to the medical literature: XXIII. Qualitative research in health care A. Are the results of the study valid? Evidence-Based Medicine Working Group. JAMA 2000;284(3):357–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Strauss AL, Corbin JM. Basics of qualitative research: grounded theory procedures and techniques. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ryan GW, Bernard HR. Techniques to Identify Themes. Field Methods 2003;15(1):85–109. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ramer SJ, McCall NN, Robinson-Cohen C, et al. Health Outcome Priorities of Older Adults with Advanced CKD and Concordance with Their Nephrology Providers’ Perceptions. J Am Soc Nephrol 2018;29(12)2870–2878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wachterman MW, Marcantonio ER, Davis RB, et al. Relationship between the prognostic expectations of seriously ill patients undergoing hemodialysis and their nephrologists. JAMA Intern Med 2013;173(13):1206–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bowling CB, O’Hare AM. Managing older adults with CKD: individualized versus disease-based approaches. Am J Kidney Dis 2012;59(2):293–302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Morton RL, Webster AC, McGeechan K, et al. Conservative Management and End-of-Life Care in an Australian Cohort with ESRD. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2016;11(12):2195–203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Okamoto I, Tonkin-Crine S, Rayner H, et al. Conservative care for ESRD in the United Kingdom: a national survey. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2015;10(1):120–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brown MA, Collett GK, Josland EA, Foote C, Li Q, Brennan FP. CKD in elderly patients managed without dialysis: survival, symptoms, and quality of life. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2015;10(2):260–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kwok AO, Yuen SK, Yong DS, Tse DM. The Symptoms Prevalence, Medical Interventions, and Health Care Service Needs for Patients With End-Stage Renal Disease in a Renal Palliative Care Program. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2016;33(10):952–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.De Biase V, Tobaldini O, Boaretti C, et al. Prolonged conservative treatment for frail elderly patients with end-stage renal disease: the Verona experience. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2008;23(4):1313–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Teruel JL, Burguera Vion V, Gomis Couto A, et al. Choosing conservative therapy in chronic kidney disease. Nefrología (English Edition) 2015;35(3):273–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tonkin-Crine S, Okamoto I, Leydon GM, et al. Understanding by older patients of dialysis and conservative management for chronic kidney failure. Am J Kidney Dis 2015;65(3):443–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Teruel JL, Rexach L, Burguera V, et al. Home Palliative Care for Patients with Advanced Chronic Kidney Disease: Preliminary Results. Healthcare (Basel) 2015;3(4):1064–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kelly-Powell ML. Personalizing choices: patietns’ experiences with making treatment decisions. Research in Nursing & Health 1997;20(3):219–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Morton RL, Tong A, Howard K, Snelling P, Webster AC. The views of patients and carers in treatment decision making for chronic kidney disease: systematic review and thematic synthesis of qualitative studies. BMJ 2010;340:c112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tong A, Cheung KL, Nair SS, Kurella Tamura M, Craig JC, Winkelmayer WC. Thematic synthesis of qualitative studies on patient and caregiver perspectives on end-of-life care in CKD. Am J Kidney Dis 2014;63(6):913–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Russ AJ, Shim JK, Kaufman SR. “Is there life on dialysis?”: time and aging in a clinically sustained existence. Med Anthropol 2005;24(4):297–324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wong SP, Vig EK, Taylor JS, et al. Timing of Initiation of Maintenance Dialysis: A Qualitative Analysis of the Electronic Medical Records of a National Cohort of Patients From the Department of Veterans Affairs. JAMA Intern Med 2016;176(2):228–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schell JO, Patel UD, Steinhauser KE, Ammarell N, Tulsky JA. Discussions of the kidney disease trajectory by elderly patients and nephrologists: a qualitative study. Am J Kidney Dis 2012;59(4):495–503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jennette C, Dereball V, Baldwin J, Cameron S. Renal replacement therapy and barriers to choice: using a mixed methods approach to explore the patient’s perspective. J Nephrol Soc Work 2009;32:15–26. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Institute of Medicine. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington (DC): National Academy Press; 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Item S1. Interview guide.