Abstract

Background

Snowboarding is a very common sport especially among young adults. Common injuries are hand, wrist, shoulder and ankle injuries.

Purpose

of this study was to analyze different injury pattern in children and young adults comparing with adults.

Methods

Patients who were admitted for ambulant or stationary treatment as a result of injury practicing snowboard received a questionnaire and were divided into three groups (children, young adults and adults) according to their age. Between october 2002 and may 2007 1929 injured snowboard sportsmen were included in the study. Data such as location, date and time of accident as well as information about the slope were carried out. In addition snowboard skills were classified and patients were questioned whether they wore special protectors.

Results

32.5% of injured patients were female (n = 626) and 67.5% male (n = 1303) with a mean age of patients of 21.9 (7–66) years. 13% of all patients were in group I (children), 19.2% in group II (young adults) and 67.8% in group III (adults).

Most common injuries with 60% of all accidents were injuries of the hand wrist especially in children beginning with snowboard sports. Injuries on the regular track were most common followed by jumps in the kicker park and rails in the fun-park. 20.6% in group I, 13.6% in group II and 12.8% group III did not wear any protectors.

Conclusion

Children and adolescents presented different injury patterns than adults. Young participants of up to 14 years of age are endangered especially during the first days of learning this sport. Further development of protectors with regard to biomechanical characteristics is important to achieve an optimal protective effect.

Level of evidence

2b

Keywords: Snowboard, Injuries, Fractures, Protective equipment, Helmets

1. Background

Snowboarding is a common winter sport, and it has gained popularity during the last decade.1 The first snowboards date back to 1900 when Toni Lenhardt introduced the “monoglider”. After selling one million wooden boards without binding but with a guiding cord at the tip of the board, further developments were made by Jake Burton Carpenter from New York City.

Nowadays the majority of young snowboarders are in fun-parks, half pipes and off track.2 How this sport is performed combined with acrobatics, stunts, frequent jumps, and back-country snowboarding illustrates a major potential of risks for causing traumas, with a higher rate of injury compared with skiers.3,4 An increased risk of injury is associated with jumping, which is popular among snowboarders.5

Typical for snowboarding is the positioning of the feet on the board with its resulting posture. Both feet are fixated on the board in an oblique/transversal orientation. Hands are free, and poles are not used. Hand and knee protective equipment is used from inline skating and spine protective equipment from motorsport.

Due to different movements, the injury patterns in snowboarding differ from other winter sports, such as skiing, with lesions of hand, wrist, shoulder and ankle occurring.6, 7, 8, 9 Therefore spiral tibial shaft fractures are most common in skiers compared to proximal tibial fractures in snowboarders.10

Up to 75% of skateboarders and snowboarders admitted to hospital sustain head injuries,11 and traumatic brain injuries (TBI) represent serious injuries with one in 10 children severely injured.9 Occurrences of these injuries in small, suburban hills and an urban environment are also described.1

In the literature, a few studies have compared snowboard injuries in different age groups.12,13 However, these were not specific to the snowboarding population. As serious injuries are still frequently reported, we focused on several key issues in our study.

The primary interest was to analyze different injury patterns in children and adolescents compared with adults. We hypothesized there is no difference in injury patterns between these age groups. Factors favoring the occurrence of injuries were also examined. In addition, the effect of wearing special protective equipment, especially for the hand and wrist, and helmets were studied.

2. Materials and methods

All patients injured while snowboarding and who presented at the emergency department of the medical center in Garmisch-Partenkirchen, Germany were admitted in the study.

Between October 2002 and May 2007, data from 1929 injured snowboarders were documented. Due to multiple trauma, 2026 injuries were analyzed.

Patients were divided into three groups. Group I consisted of children (up to 14 years), group II adolescents with readiness to assume a risk (between 15 and 17 years), and adults (18 years or older). These age categories were chosen to depict the trauma patterns in different periods of life.

All patients received the injury questionnaire as part of the medical treatment. These questionnaires were reviewed retrospectively. If patients could not answer the questions because of language difficulties, the questionnaires were filled out with the help of a doctor. For English speaking patients, an English version was used. Incomplete questionnaires were completed or phone. IRB approval was obtained and informed, written consent from all patients (or their parents/guardians).

Data such as name, surname, date of birth, address, date and time of accident and location were obtained and ski patrol documentation of the incidence and/or accident reports where applicable. In addition, information about the slope was obtained, and patients were asked whether the injury occurred on a normal track or offside, during a jump, in the half-pipe, in broad territory or a so-called fun-park. Snowboard skills were classified into different groups such as amateur, advanced I, advanced II (fast snowboarding with proper technique) and competition. Patients were questioned about whether they wore protective equipment, i.e. helmets, knee, spine or wrist protective equipment.

The cause of injury was classified by driving fault, jumps, failure of the material, injuries in the ski lift, collisions, and fatigue. Questions about the consumption of alcohol were not included, because exact information during anamnesis was not expected. The mechanism of falling and the direction of falling was documented.

The examining doctor completed the next section of the questionnaire with medical data, i.e. diagnosis, body side, and the commenced or recommended treatment.

Statistical analysis was performed using SAS for Windows (SAS Institute Inc, North Carolina, USA) between groups I, II and III. Analyses of single parameters were performed with t-test and chi-squared tests.

3. Results

Age of patients was between 7 and 66 years with a mean age of 21.9 years. Distribution of patients was 13% in group I, 19.2% in group II and 67.8% in group III (Fig. 1) with 32.5% female (n = 626) and 67.5% male (n = 1303). These proportions of approximately 2/3 male and 1/3 female were noticed within all age groups.

Fig. 1.

Patients' age distribution.

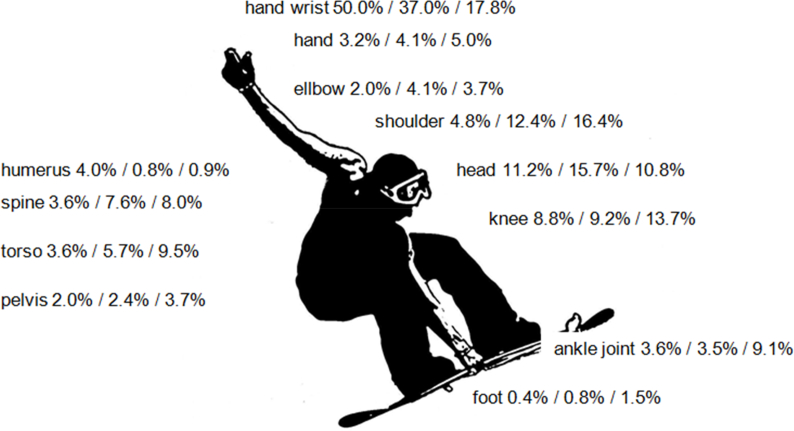

In children, injuries of the upper extremity dominated (68.0%), whereas for adolescents and adults this was 62.4% and 45.6% respectively (Fig. 2). With increasing age, injuries of the lower extremity and the spine were more common. Throughout all age groups, injuries of the hand and wrist were most common between 17.8% (adults) to 50.0% (children). 15.7% of adolescents were admitted with head injuries with 10% of this cohort still wearing helmets.

Fig. 2.

Percentages of injuries in groups I, II and III.

The most common cause of injuries was driving faults when tilting the board and corresponding loss of control with 64.7% in children, 64.0% in adolescents and 57.4% in adults.

The percentage of amateurs was with 46.8% highest in group 1 (children). Injuries on the regular slope were most common with 78.3% in group I, 72.2% in group II (adolescents) and 63.5% in group III (adults). The second most common location of injuries was during a jump in the kicker park followed by rails in the fun-park. The incidence of injuries in the kicker and fun-park increased with increasing age. Less common locations were offside, half-pipe and deep-snow. The incidence of injuries increased until 11 a.m. with a small decrease around 1 p.m. and a second peak and a decrease after 3 p.m. in all age groups.

Correlation of positioning on the board (regular vs. goofy) and the body side of the distal radial fracture was not significant.

In group I (children) the left body side was injured more often independent of the positioning on the board. In group III (adults) there was a correlation between the injured body side and the position on the board.

20.6% in group I, 13.6% in group II and 12.8% group III wore no protective equipment. Highest acceptance of wearing protective equipment was wearing wrist protective equipment, with 39.7% in group I.

4. Discussion

Many studies have analyzed injuries in snowboarding and have stated the possible risks and consequences of this sport.3,5,7,8 Since snowboarding is prevalent among children, adolescents and adults, the consequences of this sport are important for individual age groups. By analyzing the risk profiles in each age group, specific measures can be recommended to prevent injuries.

Bladin et al. found a mean age of 21 years in their cohort of female and male patients.14 In the literature, the mean age of injured patients ranges between 19 and 23 years and corresponds to our finding of 21.9 years.15,16 Also one-third of all injured athletes were under 18 years.

In our study, 32.5% of injured patients were female (n = 626) and 67.5% male (n = 1303). This finding concurs with similar results in the literature17 and proves that readiness to assume risk is higher in males than in females.18

Up to 75% of skateboarders and snowboarders admitted to hospital sustain head injuries.11 The percentage of head injuries is between 9.2 and 17.7%.19 Polites et al. present head injuries in 26% of children snowboarders with a helmet use of 34%.9 In our study 15.7% of adolescents were admitted with head injuries, even though 0% of this cohort still wear helmets. Severe accidents are mainly observed off track in unknown territory.20

In the literature, the prevalence of hand injuries in snowboarding range from 19 to 36%16. In our study, hand injuries constituted 7% of all injuries with a higher percentage of 50% in children and adolescents. Only 13% of all patients wore protective wrist equipment, mostly included in gloves. According to the literature, special protective equipment could reduce the rate of hand and wrist injuries by 85%.21 De Noijer et al. demonstrated that the willingness to wear protective equipment depends on psychosocial influences and is mainly determined by parents and friends.22

Most of the fatal injuries in snowboarding are massive head injuries,23 and head injuries are more frequent among snowboarders than skiers.5,9 In our study, we could not prove that head injuries, and especially injuries such as concussions, can be prevented by wearing helmets. Other studies, however, confirm the effectiveness of helmets in protecting users from head injuries but question their effects on TBI (traumatic brain injury), especially concussion.24 Bailly et al. suggest that initial speed, impacted surface, and pass/fail criteria used in helmet standard performance test do not fully reflect the magnitude and variability of snowboarding backward-fall impacts.25

In our study, the highest rate of head injuries was in adolescents between 15 and 17 years of age. Due to this finding, Austria and Italy introduced the mandatory wearing of a helmet until 14 years of age, although this is not enough. Even though there is no such obligation in Germany, campaigns to motivate adolescents to wear helmets should be encouraged.

Also, a special fall training should be included in snowboard classes, so students learn to distribute their load on the whole body by scrolling instead of falling with their extended wrists. 5% of the patients reviewed had taken such training before.

Fenerty et al. suggest that after helmet legislation was enacted, 100% compliance of helmet use was observed at ski hills in Nova Scotia.26 A multifaceted approach, including education, legislation, and enforcement was effective in achieving full helmet compliance among all ages of skiers and snowboarders.26 Other findings suggest that injury prevention and outreach programs are needed to increase helmet use and reduce the risk of head injury.11

Our study has limitations. In the trauma center, most patients treated were injured in the nearby area. Patients who returned to their hometown for treatments were not included, as equally severely injured patients carried by helicopter to specialized trauma centers. Also, patients who did not present after injury could not be included. No data about fatal injuries is available. Doctors on call collected the medical data and so depending on the level of experience, there is a margin of deviation in diagnostics.

5. Conclusion

One-third of injured patients were under 18. Parents should be involved in best injury prophylaxis to prevent injuries in adulthood.

Children and adolescents showed a high incidence of fractures in the wrist region and distal radius. According to the literature, appropriate protective equipment can decrease the incidence of these fractures significantly. Also, a special fall training should be included in snowboard classes, so students learn to distribute their load on the whole body by scrolling instead of falling with their extended wrists. Head injuries can be prevented by wearing appropriate helmets, and we recommend the mandatory wearing of helmets for children up to 14 years of age.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

IRB approval was obtained and informed, written consent from all patients (or their parents/guardians).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Funding

Not applicable.

Authors' contributions

OB, HK, AJ and MR analyzed and interpreted the patient data. MC, LVE, GSM and JBS performed the statistics as well as the discussion, and were major contributors in writing the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

References

- 1.Stenroos A., Handolin L. Head injuries in urban environment skiing and snowboarding: a retrospective study on injury severity and injury mechanisms. Scand J Surg. 2017 doi: 10.1177/1457496917738866. 1457496917738866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Westphal K. [Carving ski and snowboard: trauma trend in a trendy sport. Fast and with sharp edge into the clinic] MMW - Fortschritte Med. 2007;149(8):10–12. doi: 10.1007/BF03364969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sakamoto Y., Sakuraba K. Snowboarding and ski boarding injuries in Niigata, Japan. Am J Sports Med. 2008;36(5):943–948. doi: 10.1177/0363546507313573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sran R., Djerboua M., Romanow N. Ski and snowboard school programs: injury surveillance and risk factors for grade-specific injury. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2018;28(5):1569–1577. doi: 10.1111/sms.13040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kurpiers N., McAlpine P., Kersting U.G. Predictors of falls in recreational snowboard jumping: an observational study. Injury. 2017;48(11):2457–2460. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2017.08.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hagel B. Skiing and snowboarding injuries. Med Sport Sci. 2005;48:74–119. doi: 10.1159/000084284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.O'Neill D.F., McGlone M.R. Injury risk in first-time snowboarders versus first-time skiers. Am J Sports Med. 1999;27(1):94–97. doi: 10.1177/03635465990270012301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ronning R., Gerner T., Engebretsen L. Risk of injury during alpine and telemark skiing and snowboarding. The equipment-specific distance-correlated injury index. Am J Sports Med. 2000;28(4):506–508. doi: 10.1177/03635465000280041001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Polites S.F., Mao S.A., Glasgow A.E., Moir C.R., Habermann E.B. Safety on the slopes: ski versus snowboard injuries in children treated at United States trauma centers. J Pediatr Surg. 2018;53(5):1024–1027. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2018.02.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stenroos A., Pakarinen H., Jalkanen J., Malkia T., Handolin L. Tibial fractures in alpine skiing and snowboarding in Finland: a retrospective study on fracture types and injury mechanisms in 363 patients. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2016;105(3):191–196. doi: 10.1177/1457496915607410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sadeghian H., Nguyen B., Huynh N., Rouch J., Lee S.L., Bazargan-Hejazi S. Factors influencing helmet use, head injury, and hospitalization among children involved in skateboarding and snowboarding accidents. Perm J. 2017;21 doi: 10.7812/TPP/16-161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bailly N., Afquir S., Laporte J.D. Analysis of injury mechanisms in head injuries in skiers and snowboarders. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2017;49(1):1–10. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0000000000001078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.DeFroda S.F., Gil J.A., Owens B.D. Epidemiology of lower extremity injuries presenting to the emergency room in the United States: snow skiing vs. snowboarding. Injury. 2016;47(10):2283–2287. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2016.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bladin C., Giddings P., Robinson M. Australian snowboard injury data base study. A four-year prospective study. Am J Sports Med. 1993;21(5):701–704. doi: 10.1177/036354659302100511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pino E.C., Colville M.R. Snowboard injuries. Am J Sports Med. 1989;17(6):778–781. doi: 10.1177/036354658901700610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Idzikowski J.R., Janes P.C., Abbott P.J. Upper extremity snowboarding injuries. Ten-year results from the Colorado snowboard injury survey. Am J Sports Med. 2000;28(6):825–832. doi: 10.1177/03635465000280061001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dohjima T., Sumi Y., Ohno T., Sumi H., Shimizu K. The dangers of snowboarding: a 9-year prospective comparison of snowboarding and skiing injuries. Acta Orthop Scand. 2001;72(6):657–660. doi: 10.1080/000164701317269111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lyons R.A., Delahunty A.M., Kraus D. Children's fractures: a population based study. Inj Prev. 1999;5(2):129–132. doi: 10.1136/ip.5.2.129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Machold W., Kwasny O., Gassler P. Risk of injury through snowboarding. J Trauma. 2000;48(6):1109–1114. doi: 10.1097/00005373-200006000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gabl M., Lang T., Pechlaner S., Sailer R. [Snowboarding injuries] Sportverletz Sportschaden. 1991;5(4):172–174. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-993582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hagel B., Pless I.B., Goulet C. The effect of wrist guard use on upper-extremity injuries in snowboarders. Am J Epidemiol. 2005;162(2):149–156. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwi181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.de Nooijer J., de Wit M., Steenhuis I. Why young Dutch in-line skaters do (not) use protection equipment. Eur J Publ Health. 2004;14(2):178–181. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/14.2.178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Levy A.S., Smith R.H. Neurologic injuries in skiers and snowboarders. Semin Neurol. 2000;20(2):233–245. doi: 10.1055/s-2000-9833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bailly N., Laporte J.D., Afquir S. Effect of helmet use on traumatic brain injuries and other head injuries in alpine sport. Wilderness Environ Med. 2018;29(2):151–158. doi: 10.1016/j.wem.2017.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bailly N., Llari M., Donnadieu T., Masson C., Arnoux P.J. Head impact in a snowboarding accident. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2017;27(9):964–974. doi: 10.1111/sms.12699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fenerty L., Heatley J., Young J. Achieving all-age helmet use compliance for snow sports: strategic use of education, legislation and enforcement. Inj Prev. 2016;22(3):176–180. doi: 10.1136/injuryprev-2015-041699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]