Summary

Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome (HGPS) is a rare disorder caused by a point mutation in the Lamin A gene that produces the protein progerin. Progerin toxicity leads to accelerated aging and death from cardiovascular disease. To elucidate the effects of progerin on endothelial cells, we prepared tissue-engineered blood vessels (viTEBVs) using induced pluripotent stem cell-derived smooth muscle cells (viSMCs) and endothelial cells (viECs) from HGPS patients. HGPS viECs aligned with flow but exhibited reduced flow-responsive gene expression and altered NOS3 levels. Relative to viTEBVs with healthy cells, HGPS viTEBVs showed reduced function and exhibited markers of cardiovascular disease associated with endothelium. HGPS viTEBVs exhibited a reduction in both vasoconstriction and vasodilation. Preparing viTEBVs with HGPS viECs and healthy viSMCs only reduced vasodilation. Furthermore, HGPS viECs produced VCAM1 and E-selectin protein in TEBVs with healthy or HGPS viSMCs. In summary, the viTEBV model has identified a role of the endothelium in HGPS.

Keywords: Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome, tissue-engineered blood vessel, microphysiological system, induced pluripotent stem cells, vascular endothelium, smooth muscle cells, shear stress

Highlights

-

•

Smooth muscle and endothelial cells were derived from progeria and healthy donors

-

•

Progeria endothelial cells exhibit altered response to fluid shear stress

-

•

Functional engineered blood vessels were fabricated from iPSC-derived SMCs and ECs

-

•

Progeria donor-derived engineered blood vessels recapitulated the disease phenotype

Atchison and colleagues produced hiPSC-derived vascular smooth muscle cells and vascular endothelial cells from healthy and progeria patients. These cells were used to fabricate functional tissue-engineered blood vessels that express key features of the progeria cardiovascular phenotype. This work provides a novel platform to study progeria and other cardiovascular diseases using iPSC-derived cells in an in vitro platform.

Introduction

Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome (HGPS) is a rare, genetic condition that is caused by a mutation in the Lamin A gene (LMNA) that produces a farnesylated form of the protein known as progerin. In affected individuals, the disease predominantly manifests as a variety of aging symptoms at a very young age, including hair loss, wrinkled skin, subcutaneous fat loss, and joint instability (Xiong et al., 2016). The most devastating and life-threatening disease characteristic, however, is the development of atherosclerosis in the early teenage years. Patients usually die of heart attack or stroke between 10 and 20 years due to the nuclear accumulation of the progerin protein (Olive et al., 2010). Pathological analysis of the arteries of HGPS patients shows a noticeable presence of progerin primarily in the medial vascular smooth muscle cells (SMCs), but also the adventitial fibroblasts and endothelial cells (ECs) (Olive et al., 2010).

Cells of the mesenchymal lineage, including vascular SMCs, are heavily affected by nuclear accumulation of progerin protein. SMC loss or malfunction in HGPS patient arteries is a key cause of the development of atherosclerosis that is eventually fatal to HGPS individuals (Zhang et al., 2014), resulting in thickened vessel walls and calcification. Despite extensive evidence that progerin toxicity in vascular SMCs is linked to the atherosclerotic defects associated with HGPS, the presence of progerin in other vascular cell types, including ECs, suggests that toxicity to these cells may play a role in the development of cardiovascular defects associated with the condition. Previous studies to elucidate the effects of progerin on ECs, however, have shown no evidence of a difference between ECs derived from healthy and HGPS patients (Zhang et al., 2011). This may be due to the lower levels of progerin present in these cells, or the 2D environment in which these cells were studied.

EC dysfunction is a key contributor to the pathobiology of atherosclerosis due to the importance of the endothelium in maintaining vascular homeostasis and vascular tone (Rajendran et al., 2013). The critical role of the endothelium in general atherosclerosis and the presence of progerin in both intimal ECs and atherosclerotic plaque of HGPS patients would suggest that progerin toxicity may not only affect vascular SMCs, but also the endothelium (Gimbrone and García-Cardeña, 2016, Olive et al., 2010). Human ECs overexpressing progerin exhibited decreased expression of key homeostatic genes, KLF2 and NOS3, expressed proinflammatory markers, and released proinflammatory cytokines, which caused dysfunction in healthy ECs when cultured together (Yap et al., 2008). In addition, Lamin A defects induced by the protease inhibitor, Atazanavir, in healthy endothelial progenitor cells (EPCs) showed increased expression of ICAM-1 as well as increased monocyte adhesion (Bonello-Palot et al., 2017). This evidence suggests that Lamin A defects and progerin may adversely affect ECs (Yap et al., 2008).

Despite this evidence, little is known about the endothelial contribution in blood vessels of individuals with HGPS. Most HGPS studies using induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC)-derived sources focus on the cells most heavily affected by progerin toxicity, such as mesenchymal stem cells, fibroblasts, and SMCs, and bypass the study of cell types that express this protein at lower levels, including ECs. This may in part be due to the overall lower levels of LMNA present in ECs which leads to less progerin production (Zhang et al., 2011). Furthermore, previous 2D models have focused on static culture to assess health and function (Kim, 2014). Recently, Osmanagic-Myers et al. (2019) developed a transgenic mouse model in which only ECs expressed progerin, suggesting a role for the endothelium in HGPS. The development of atherosclerosis due to endothelial dysfunction, however, is caused by altered endothelial response to flow (Gimbrone and García-Cardeña, 2016, Yap et al., 2008). Therefore, it is critical to evaluate EC response to physiological shear stresses at the 2D and 3D level to fully to assess their functionality and utility in disease models of the vasculature.

Previously, we developed a 3D tissue-engineered blood vessel (TEBV) model of HGPS using iPS-derived SMCs (iSMCs) from HGPS patients and blood-derived endothelium from healthy individuals (Atchison et al., 2017). This model was capable of replicating the structure and function of small-diameter arterioles using healthy patient cells as well as exhibit known disease characteristics previously cited in HGPS (Fernandez et al., 2016). This model improved upon 2D cell culture models by creating an accurate 3D microenvironment for cell development and was superior to animal models through the use of human cell sources. A key limitation of this model, however, was the mismatch of iSMCs in the medial wall of the TEBVs and human cord blood-derived endothelial progenitor cells (hCB-EPCs) from a separate donor lining the inner lumen. In addition, these iSMCs did not express markers of terminal differentiation, such as myosin heavy chain 11 (MHC11) as is seen in native vascular SMCs. Although this model provided useful information about the SMC effects on the cardiovascular disease development in HGPS, it fails to fully model human vasculature or show the effects of endothelium on the HGPS phenotype. An ideal iPS-derived TEBV model of HGPS would incorporate fully differentiated iPS-derived vascular SMCs and iPS-derived vascular ECs from the same donor iPSC line that function like native human vessels.

To quickly and more efficiently acquire both iPS-derived cell types for donor-specific TEBVs, we adopted a modified protocol from Patsch et al. (2015) to develop iPS-derived smooth muscle cells (viSMCs) and endothelial cells (viECs) that function similar to mature vascular versions of both cell types. Healthy donors viSMCs and viECs show key structural and functional characteristics of vascular SMCs and ECs, while HGPS viSMCs and viECs show reduced function and express various disease characteristics. In addition, HGPS viTEBVs maintain many of the disease characteristics associated with HGPS previously seen in HGPS iSMC TEBVs with hCB-EPCs, including reduced function, excess ECM deposition, and progerin expression. Healthy donor viTEBVs, however, show improved functional response to vasoagonists and increased expression of markers of terminal differentiation compared with iSMC TEBVs, indicating a more mature vascular structure. In addition, we found that viECs on HGPS viTEBVs express key inflammatory markers, such as increased expression of E-selectin and vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 (VCAM1) after multiple weeks of perfusion. TEBVs fabricated with HGPS viECS also show reduced response to acetylcholine independent of the medial wall cell source. This work shows the utility of a viTEBV platform for HGPS disease modeling and suggests a potential role of the endothelium in HGPS cardiovascular disease development.

Results

Phenotypic Characterization of viSMCs Derived from Normal and HGPS iPSCs

To validate the use of a modified protocol to derive viSMCs and viECs from healthy and HGPS donor iPSC lines, we differentiated and characterized two donors of each cell line for key structural and functional markers pre-differentiation and post-differentiation. iPSCs from both HGPS (HGADFN167 [clone 2] and HGADFN0031B) and normal (HGFDFN168 [clone 2] and DU11) cell lines showed key pluripotency markers Oct4 and Tra-1-81 before differentiation, indicating their differentiation potential. They also stained positive for alkaline phosphatase and had normal karyotypes with no clonal abnormalities (Figure S1).

To derive SMCs with comparable structure and function to those found in the vasculature, normal and HGPS viSMCs were differentiated from iPSCs according to the protocol of Patsch et al. (2015) and, after 6 days, plated under contractile conditions consisting of collagen-coated plates and Activin A- and heparin-supplemented serum-free medium (Figures 1 and 2A). On day 6, viSMCs expressed contractile proteins, α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA), calponin, and MHC11, indicating terminally differentiated SMCs (Figures 2B and S2A). Quantification of immunostaining images indicated MHC11 expression in greater than 99% of cells. Flow cytometry analysis also indicated a pure population of SMCs with greater than 90% positive expression of α-SMA and calponin post-differentiation (Figures 2C and S2B). Treatment with the vasoconstrictor U44619 also indicates that normal and HGPS viSMCs are contractile in response to vasoactive drugs (Figures S2C and S2D).

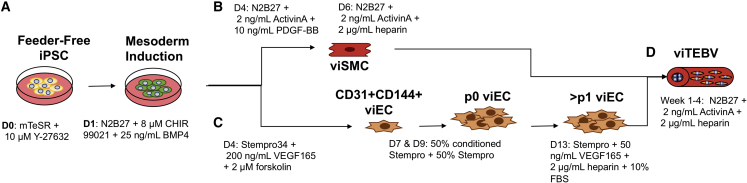

Figure 1.

Schematic Diagram of the Procedure to Produce iPSC-Derived TEBVs from Healthy and HGPS Patients

(A) iPSCs are differentiated into (B) smooth muscle cells (viSMCs) or (C) endothelial cells (viECs) using a 7-day process as described previously by Patsch et al. (2015).

(D) viSMCs are then incorporated into a dense collagen gel construct that is seeded with viECs on the luminal surface to create viTEBVs using the process described previously by Fernandez et al. (2016).

viTEBVs are then incorporated into a flow loop and perfused with steady laminar flow at a shear stress of 6.8 dynes/cm2 for 1 to 4 weeks for further maturation and functional characterization studies.

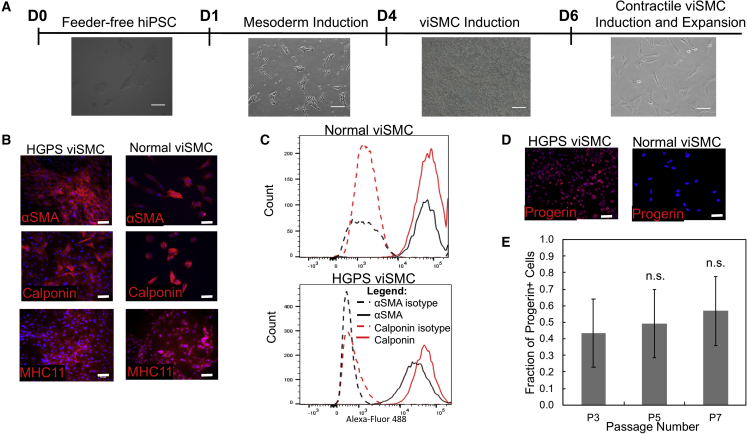

Figure 2.

Characterization of viSMCs from Normal (168 clone 2) and HGPS (167 clone 2) Donors

(A) Phase contrast images of cells at each stage of differentiation from iPSCs at day 0 to mesoderm induction at day 1 to viSMC induction on day 4 to contractile viSMC induction on day 6. Scale bar, 100 μm.

(B) Representative images of immunofluorescence staining with α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA), calponin, and myosin heavy chain 11 on viSMCs from HGPS and normal donors after differentiation and plating in contractile conditions. Scale bar, 50 μm.

(C) Flow cytometry analysis of calponin and α-SMA-positive cells in HGPS and normal viSMCs post-differentiation and corresponding isotype controls.

(D) Representative images of immunofluorescence staining with progerin on viSMCs from HGPS and normal donors after differentiation and five passages. Scale bar, 50 μm.

(E) Quantification of the fraction of progerin-positive cells of HGPS viSMCs at various passages normalized to the total number of nuclei. Data are represented as mean ± SEM. n = 3 independent experiments for each passage. n.s., not significant.

To validate this differentiation protocol for HGPS studies, viSMCs were characterized for progerin expression after multiple passages. HGPS viSMCs at all passages showed progerin-positive cells as indicated by immunofluorescence staining (Figure 2D) and western blot analysis (Figure S2E). Since viSMCs beyond passage 5 showed a majority of progerin-expressing cells, HGPS viSMCs passage 5 and older were used for all subsequent TEBV studies (Figure 2E). viSMCs derived from HGPS iPSCs at older passages also showed various disease characteristics, such as increased senescence through β-galactosidase staining (Figure S2F) and significantly more blebbed nuclei compared with viSMCs derived from normal iPSCs (Figures S3A and S3B).

Phenotypic Characterization of viECs Derived from Normal and HGPS iPSCs

viECs were differentiated from both the normal and HGPS iPSC lines using a modified version of the Patsch et al. (2015) protocol to obtain large numbers of vascular ECs. viECs were differentiated for 6 days instead of 5 days as reported by Patsch et al., with one additional day during the endothelial cell induction phase, which produced larger quantities of viECs with improved structural and functional characteristics. After 7 days, viECs were sorted for CD31+ CD144−, CD31− CD144+, and CD31+ CD144+ cell populations to increase yield. Only CD31− CD144− cells were rejected during sorting. viECs were plated on collagen rather than fibronectin in Stempro-conditioned media consisting of 1:1 fresh Stempro-34 SFM and conditioned Stempro media collected during differentiation. These conditions improved the viability and expandability of sorted cell populations. viECs were later switched to viEC media containing VEGF165, heparin and 10% heat inactivated fetal bovine serum (HI-FBS) to induce a more vascular phenotype (Figures 1 and 3A). After sorting, viECs from all cell lines showed expression of endothelial markers platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule (PECAM), vascular endothelial cadherin (VE-cadherin), vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 (VEGFR2), and von Willebrand factor (Figures 3B, S4A, and S4B). These proteins are necessary for ECs to function and respond to shear stress (Tzima et al., 2005).

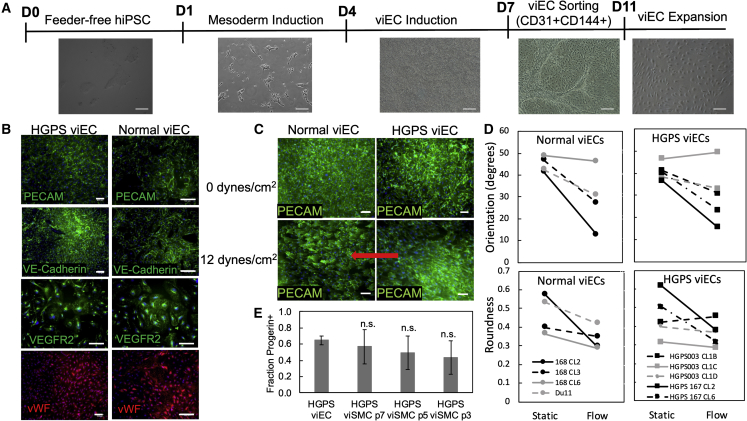

Figure 3.

Characterization of viECs from Normal and HGPS Donors

(A) Phase contrast images of cells at each stage of differentiation from iPSCs at day 0 to mesoderm induction at day 1 to viEC induction on day 4 to viEC sorting on day 7 to viEC expansion. Scale bar, 100 μm.

(B) Representative images of immunofluorescence staining with PECAM, VE-cadherin, von Willebrand factor (vWF), and VEGFR2 on viECs from HGPS (167 clone 2) and normal (168 clone 2) donors after differentiation and sorting. Scale bar, 50 μm.

(C) Representative images of immunofluorescence staining with PECAM on viECs from HGPS (167 clone 2) and normal (168 clone 2) donors after either static culture or exposure to physiological shear stress of 12 dynes/cm2 for 24 h. Red arrow indicates direction of flow. Scale bar, 50 μm.

(D) Quantification of alignment and roundness of normal (168 clones 2, 3, 6, and DU11) and HGPS (167 clones 2 and 6, and 003 clones 1B, 1C, and 1D) viECs after 24 h of static culture or exposure to 12 dynes/cm2. Error bars for each donor were omitted to show trends.

(E) Quantification of the fraction of progerin-positive viECs compared with the fraction of progerin-positive HGPS viSMCs. Data are represented as mean ± SEM. n = 3 independent experiments for each cell type under each condition. #p < 0.0001.

We then tested the ability of viECs to respond to physiological shear stresses by applying 12 dynes/cm2 for 24 h. viECs from normal and HGPS iPSC lines elongated and aligned in the direction of flow (Figure 3C and S4C). All of the viECs from healthy donor iPSCs showed a significant decrease in orientation and roundness (p = 0.0371 and 0.0335, respectively, one-sided t test), whereas viECs from 4/5 clones exhibited a decrease in orientation and roundness (p = 0.0436 and 0.0778, one-sided t test) (Figure 3D). Treatment with tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) for 6 h caused upregulation of the adhesion molecule ICAM-1 and increased nuclear factor κB localization to the nucleus, indicating the ability of these viECs to respond appropriately to inflammatory cytokines like those in native vasculature (Figure S5A). In addition, HGPS viECs showed a majority of progerin-positive cell populations at comparable levels to HGPS viSMCs, as indicated by immunofluorescence staining and western blot (Figures 3E, S4D, and S4E). The majority of viECs expressed progerin once passaged and cultured in viEC medium, similar to viSMCs. viECs did not express progerin at significant levels before culture in viEC medium or directly after sorting (data not shown). Normal and HGPS viECs showed intrinsic characteristics of healthy ECs through tube formation in Matrigel (Figure S5B). HGPS viECs cultured on Matrigel showed significantly less tube length per field compared with normal viECs cultured on Matrigel after 18–24 h (Figure S5C). HGPS viECs also showed a significantly larger fraction of blebbed nuclei compared with normal viECs (Figures S3C and S3D), but did not express leukocyte adhesion molecules when cultured under static conditions (Figure S5D).

viECs exposed to 12 dynes/cm2 for 24 h showed upregulation of the flow-associated genes, Kruppel-like factor (KLF2), and nuclear erythroid 2-related factor 2 (NRF2), compared with static controls (Figures 4A and 4B), similar to hCB-EPCs that were used in previous studies (Brown et al., 2009). After exposure to flow, both normal and HGPS viECs showed a significant upregulation of the atheroprotective genes KLF2 and NRF2 (Figures 4A and 4B), but the response of HGSP viECs was less than that of normal viECs. In addition, expression of the endothelial nitric oxide synthase (NOS3) gene, an essential regulator of nitric oxide by vascular endothelium to control vascular tone, increased after flow in hCB-EPCs (p < 0.001). In viECs from normal iPSCs, NOS3 levels in response to flow did not significantly change from static levels (Figure 4C). Counter to hCB-EPCs and normal viECs, NOS3 expression was significantly downregulated in HGPS viECs after flow exposure (p < 0.0001) (Figure 4C).

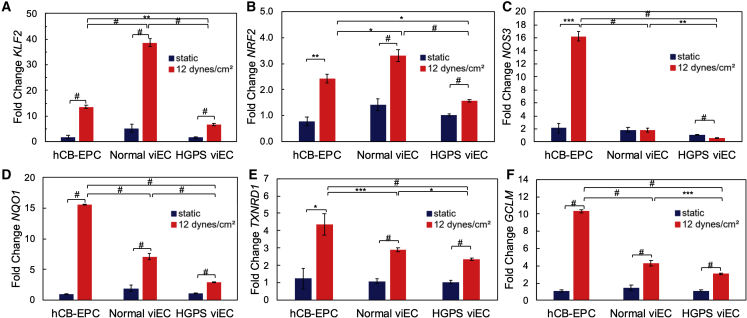

Figure 4.

Gene Expression of hCB-EPCs and viECs after Shear Stress Exposure

qRT-PCR of (A) KLF2, (B) NRF2, (C) NOS3, (D) NQO1, (E) TXNRD1, and (F) GCLM gene expression on hCB-EPCs, HGPS viECs (167 clones 2, 6 and 003 clones 1B, 1C, 1D) and normal viECs (168 clones 2, 3, 6 and DU11) after either static culture or exposure to physiological shear stress of 12 dynes/cm2 for 24 h. Data were normalized to GAPDH expression and gene expression in hCB-EPCs and viECs exposed to 12 dynes/cm2 for 24 h were normalized to respective hCB-EPCs or viECs under static culture. Data are represented as mean ± SEM. n = 5 cell lines for HGPS and 4 cell lines for normal with 2 or 3 independent replicates for each cell line. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001, #p < 0.0001.

Due to previous implications of NRF2 transcription and nuclear location being affected by progerin-expressing cells, we further evaluated the downstream targets of NRF2, heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1), NAD(P)H-quinone oxidoreductase 1 (NQO1), thioredoxin reductase 1 (TXNRD1), glutamate-cysteine ligase catalytic subunit (GCLC), and glutamate-cysteine ligase modifier subunit (GCLM) (Kim et al., 2012). hCB-EPCs showed a significant increase in mRNA expression for NRF2 (Figure 4B) and these NRF2 downstream target genes after exposure to shear stress (Figures 4 and S6). Normal viECs followed the same trend in gene expression as hCB-EPCs after shear stress exposure, but with a slightly diminished response. Interestingly, HGPS viECs showed an altered trend in downstream NRF2 target gene expression compared with hCB-EPCs and normal viECs. HGPS viECs showed a significant increase in expression of these genes after exposure to flow but NQO1, TXNRD1, and GLCM showed a diminished flow response relative to normal viECs (Figures 4D–4F, S6A, and S6B). Overall, HGPS viECs generally showed smaller increases in flow-associated genes relative to normal viECs, further indicating an alteration in endothelial function in the HGPS viECs.

Structural and Functional Characterization of Normal and HGPS viTEBVs

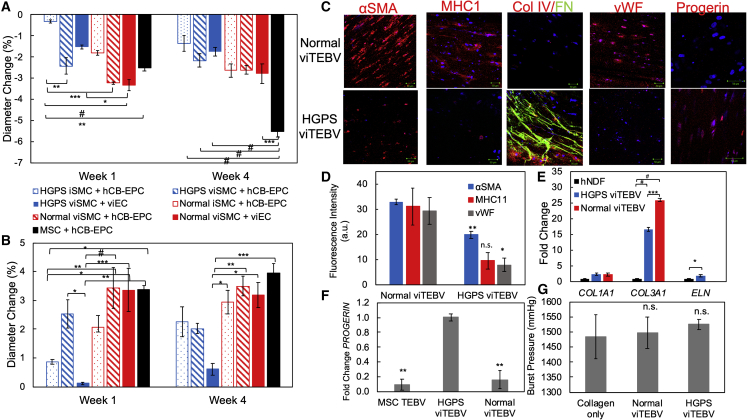

To study the effects of viSMCs and viECs on the cardiovascular phenotype of HGPS, we tested the structural and functional effects of these cells in TEBVs. After 1 week of perfusion, TEBVs fabricated from viSMCs from either normal or HGPS donors showed increased contractile response after exposure to 1 μM phenylephrine compared with TEBVs fabricated from normal or HGPS iSMCs used in our previous TEBV model (Atchison et al., 2017) (Figure 5A). In addition, vasoactivity of TEBVs with normal viSMCs and viECs responded at comparable levels to primary MSC-derived TEBVs, indicating that the Patsch et al. differentiation protocol provides a more functional model. Furthermore, at 1 week, iSMC TEBV vasoactivity is less than viSMC TEBV vasoactivity, while at 4 weeks, iSMC TEBV vasoactivity is less than or equal to viSMC TEBV vasoactivity.

Figure 5.

Characterization of viTEBVs Fabricated from viSMCs and viECs from HGPS (167 clone 2) and Normal (168 clone 2) Donors

(A) Week 1 and week 4 response to 1 μM phenylephrine of TEBVs fabricated from either HGPS viSMCs or iSMCs, normal viSMCs or iSMCs, and seeded with either HGPS viECs, normal viECs, or hCB-EPCs.

(B) Week 1 and week 4 response to 1 μM acetylcholine of TEBVs fabricated from either HGPS viSMCs or iSMCs, normal viSMCs or iSMCs, and seeded with either HGPS viECs, normal viECs, or hCB-EPCs.

(C) Representative images of immunofluorescence staining with α-SMA, myosin heavy chain 11, collagen IV and fibronectin, progerin, or vWF antibodies at week 4 of perfusion on normal 168 and HGPS 167 viTEBVs. Scale bar, 50 μm.

(D) Quantification of protein expression in (C).

(E) qRT-PCR of COL1A1, COL3A1, and ELN gene expression in human neonatal dermal fibroblasts (hNDF), HGPS viTEBVs, and normal viTEBVs. Data were normalized to GAPDH expression and gene expression for each group was normalized to the hNDF group. n = 2 for hNDF group, n = 3 for each viTEBV group.

(F) qRT-PCR of PROGERIN gene expression on MSC TEBV, HGPS viTEBV, and normal viTEBVs after 1 week of perfusion. Progerin expression was set at 100% for HGPS viTEBVs. Data normalized to GAPDH expression. n = 3 for each TEBV group.

(G) Burst pressure of normal and HGPS viTEBVs after 1 week of perfusion compared with collagen constructs without cells. Data are represented as mean ± SEM. n = 3 TEBVs for each TEBV cell type. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001, #p < 0.0001.

Similar to our previous model, functional responses and trends were fairly stable for multiple weeks of perfusion. TEBVs fabricated from healthy donor cells showed significantly higher vasoactivity than those fabricated from HGPS donor cells (Figures 5A and S7A). In addition, viTEBVs fabricated from normal viECs showed comparable dilation in response to 1 μM acetylcholine as TEBVs fabricated from primary hCB-EPCs (Figures 5B and S7B). viTEBVs with HGPS viECs, however, showed a significant decrease in dilation compared with TEBVs containing hCB-EPCs or normal viECs (Figures 5B and S7B).

After 4 weeks of perfusion, viSMCs in viTEBVs expressed not only the contractile proteins α-SMA and calponin as we had observed previously with the iSMC TEBVs (Atchison et al., 2017), but also MHC11, which was not present in iSMC TEBVs, indicating a more accurate vascular phenotype (Figures 5C and S7C). HGPS viTEBVs showed reduced expression of all contractile proteins compared with healthy viTEBV controls (Figure 5D) as well as increased expression of progerin and extracellular matrix proteins, collagen IV and fibronectin, compared with normal viTEBVs (Figures 5C and S7D). Relative to hNDFs, TEBVs made with iPS-derived cells showed higher levels of gene expression of collagen I and collagen III. Collagen I gene expression was similar in HGPS and normal viTEBVs, while collagen III expression was higher in normal viTEBVs. HGPS viTEBVs expressed higher levels of elastin than normal viTEBVs (Figure 5E). Progerin gene expression was also significantly upregulated in HGPS viTEBVs compared with normal viTEBVs and primary cell-derived TEBVs (Figure 5F). viTEBVs from both donors exhibited physiological burst pressures after 1 week of perfusion; however, they were not significantly different than TEBVs without cells (Figure 5G). HGPS viTEBVs also showed larger outer diameter and medial wall thickness compared with controls (Figures S7E and S7F). These results are consistent with the HGPS cardiovascular disease phenotype as well as results from our previous HGPS iSMC TEBV model (Atchison et al., 2017).

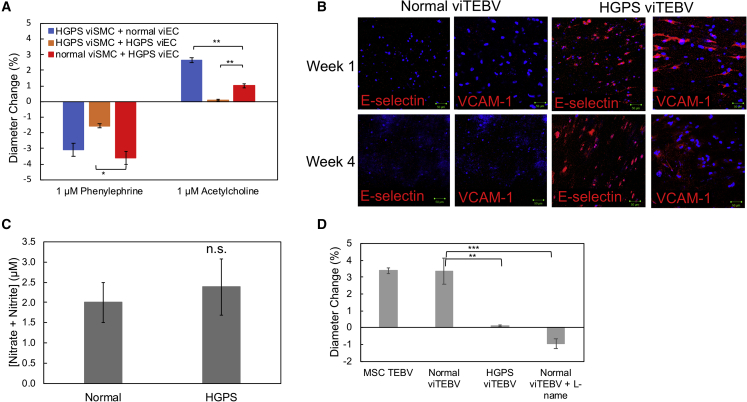

HGPS viEC Effects on Disease Development in HGPS viTEBVs

As mentioned previously, TEBVs containing HGPS viECs showed a significantly reduced response to acetylcholine. To further evaluate if viECs from HGPS donors influenced vascular structure and function, we tested the response of TEBVs fabricated from different combinations of healthy and HGPS viSMCs and viECs after 1 week of perfusion. In response to 1 μM phenylephrine, we saw a significant difference in contractility between TEBVs fabricated from normal viSMCs and HGPS viECs and TEBVs fabricated from HGPS viSMCs and HGPS viECs. Most interestingly, TEBVs fabricated from healthy hCB-EPCs or normal viECs showed comparable dilation responses to 1 μM acetylcholine, while TEBVs fabricated from HGPS viECs showed a reduced response to acetylcholine for either viSMC donor (normal or HGPS) used. viTEBVs fabricated from HGPS-derived viSMCs and viECs not only showed a significantly reduced contractile response after exposure to phenylephrine, but a significantly reduced response to acetylcholine compared with TEBVs fabricated from healthy donor viECs or hCB-EPCs (Figure 6A).

Figure 6.

Effects of HGPS viECs on TEBV Structure and Function

(A) Response to 1 μM phenylephrine and 1 μM acetylcholine of TEBVs fabricated from combinations of either HGPS (167 clone 2) or normal (168 clone 2) viSMCs with either normal (168 clone 2) or HGPS (167 clone 2) viECs.

(B) Representative images of immunofluorescence staining with VCAM-1 and E-selectin antibodies at week 1 and week 4 of perfusion on normal and HGPS viTEBVs. Scale bar, 50 μm.

(C) Total nitrite and nitrate in media collected from HGPS or normal viTEBVs after 1 week of perfusion and 48 h after medium change.

(D) Response to 1 μM acetylcholine of untreated MSC TEBVs, normal viTEBVs, HGPS viTEBVs, and normal viTEBVs treated with 3.2 μM L-name. Data are represented as mean ± SEM. n = 3–4 TEBVs for each TEBV type. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001.

To further explore these effects, we evaluated inflammatory adhesion molecule expression in normal and HGPS viTEBVs. After 1 and 4 weeks of perfusion, E-selectin and VCAM-1 were strongly expressed in HGPS viTEBVs, but not present in healthy donor viTEBVs (Figures 6B and S7D). None of the lines and their clones of normal and HGPS viECs in static conditions expressed any of the adhesion molecules (Figure S5D). This is consistent with previous studies of iPS-derived HGPS ECs in 2D studies (Yap et al., 2008). In addition, TEBVs fabricated with HGPS viSMCs and normal viECs showed little inflammatory protein expression, while TEBVs fabricated from normal viSMCs and HGPS viECs showed expression of both VCAM-1 and E-selectin after 1 week of perfusion (Figure S7G) indicating the specific role of viECs in this inflammatory response.

A decreased responsiveness to acetylcholine and increased inflammatory adhesion molecule expression is associated with reduced nitric oxide production in ECs (Khan et al., 1996); therefore, we measured the total nitrate and nitrite levels in our TEBV media to evaluate nitric oxide production by normal and HGPS viECs. There was little difference in levels of total nitrate and nitrite in media collected from HGPS viTEBVs after 1 week of perfusion compared with normal viTEBVs (Figure 6C). However, HGPS viECs did show downregulation of NOS3 mRNA expression after exposure to shear stress, therefore we tested the nitric oxide inhibitor N(G)-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester (L-NAME) on viTEBVs fabricated from normal viSMCs and viECs to determine if the dilation response of viTEBVs is regulated by nitric oxide. Normal viTEBVs perfused for 1 week and then exposed to 3.2 μM L-NAME for 10 min before acetylcholine exposure showed a significantly reduced dilation response compared with normal viTEBVs without L-NAME similar to HGPS viTEBVs (Figure 6D). These results suggest an effect of HGPS viEC on TEBV function and, therefore, an effect on vascular tone.

Discussion

Despite the vast knowledge of endothelial dysfunction and its role in atherosclerosis, there is still little evidence of how these cells play a role in the development of atherosclerosis in HGPS. Since the patient population is so small for this extremely rare condition, it has been difficult to directly study the vasculature of these patients to parse out the true causes of or cell types responsible for atherosclerotic development. In addition, due to the possible differences in the development of atherosclerosis in the general aging population and HGPS patients, it is difficult to make direct comparisons between the two disease states just yet. Therefore, it is essential that a better cardiovascular model be developed that can directly compare the effects of these cells on vascular structure and function.

Using a differentiation protocol for iPSCs that produced vascular ECs and SMCs, we improved TEBV structure and function over what we obtained previously (Atchison et al., 2017) and produced viTEBVs with cells from the same donor that respond to vasoagonists at comparable levels to TEBVs fabricated with healthy donor primary cells. These viTEBVs also exhibit improved contractile function through the expression of the terminal differentiation marker, MHC11, and demonstrate strong mechanical strength through physiological burst pressures. This improved iPSC-derived viTEBV provides a more sensitive platform that allows for better evaluation off differences in the HGPS disease state at not only the 2D level, but the 3D tissue level as well.

Here, we have extended our TEBV model to incorporate iPS-derived ECs and isolate their role in TEBV structure and function by controlling the cell sources incorporated into our tissue constructs. Most importantly, we have shown that there is a decrease in vasodilation of viTEBVs when HGPS viECs are incorporated into these constructs, no matter the viSMC donor. This indicates a potential role of these cells in HGPS disease development and not just a co-culture effect from the HGPS iSMCs, as was likely the case in previous studies with HGPS iSMC TEBVs.

With the exception of a recent mouse model of HGPS (Osmanagic-Myers et al., 2019), previous studies to evaluate the ECs derived from HGPS iPSCs only focused on the basic function of these endothelial cells in 2D static culture. These studies are very limited in their scope of endothelial function, particularly in terms of their role in the cardiovascular system. This may explain why there is more emphasis on the role of SMCs in HGPS, which have shown a greater defect in structure and function due to the strong presence of progerin. We further evaluated the specific structural and functional role of vascular ECs in 2D, such as response to shear stress. In addition, the viECs are capable of maintaining expression of VEGFR2, PECAM, and VE-cadherin over multiple passages once switched to viEC medium, which helps maintain their flow responsive capabilities over long-term cultures. This also allows us to culture them for longer periods of time, which is essential for developing the disease phenotype seen in HGPS. Previous work has shown that iPS-derived ECs from HGPS patients have reduced mRNA levels of Lamin proteins overall and, therefore, reduced progerin expression compared with iSMCs, MSCs and fibroblasts. This could explain the smaller effects seen in iPS-derived ECs in 2D compared with these other cell types expressing higher levels of Lamin proteins (Zhang et al., 2011). Nonetheless, 2D and 3D flow assays show specific abnormalities present in HGPS viECs compared with primary hCB-EPCs and normal viEC controls. The reduced NOS3 expression is consistent with what was observed in ECs in a mouse model of HGPS (Osmanagic-Myers et al., 2019). This reduced responsiveness of HGPS viECs to flow and altered gene expression may explain profound effects in the vasculature long-term. Also, the HGPS viECs show comparable levels of progerin-positive nuclei compared with the HGPS viSMCs. This may be due to donor variability, differentiation to a more vascular phenotype, our ability to maintain vascular function in the viECs over long-term culture, or any combination of these factors.

In addition, 2D cell culture does not fully replicate an in vivo microenvironment and therefore is not a true depiction of how certain cells or tissues will react in a specific disease state. These TEBV studies show the importance of a 3D microenvironment for parsing out differences in cell structure and function. Although HGPS viECs display the basic characteristics of endothelial function in 2D culture, once incorporated into the TEBV constructs, they exhibit many signs of endothelial dysfunction and activation normally present in general atherosclerosis. These defects in vascular function seen in the 3D tissue constructs are detected in many of the 2D flow studies. For example, HGPS viECs reduce the dilation response after exposure to acetylcholine in TEBVs fabricated with these cells is in accordance with their downregulation of NOS3 after exposure to physiological shear stresses in 2D culture. Interestingly enough, the levels of nitrates and nitrites present in the media were similar between normal and HGPS viTEBVs. However, viTEBV treatment with the nitric oxide inhibitor, L-NAME, reversed the dilation seen in normal viTEBVs indicating that the dilation in viTEBVs may be induced by nitric oxide release from TEBVs in response to acetylcholine exposure. This further indicates the altered vasoactive response of HGPS viECs, which may be in part due to inactivation of or reduced NRF2 activity or other antioxidant genes that cause reactive oxygen species to block the effects of nitric oxide produced by the HGPS viECs. This would be consistent with previous reports of the effects of progerin on the repression of NRF2 activity (Kubben et al., 2016); however, the oxidative state of HGPS viECs within viTEBVs needs to be examined further in order to determine the exact mechanisms behind this altered vasoactive function.

EC activation of adhesion molecules, VCAM-1 and E-selectin, is common in various inflammatory conditions and cardiovascular disease development. HGPS viTEBVs show an increase in expression of both VCAM-1 and E-selectin after 1 and 4 weeks of perfusion compared with normal viTEBVs, indicating a chronic activation of the endothelium in this disease state. ICAM-1 expression, however, was not present at either time point. Various factors play a role in which adhesion molecule will be expressed. For instance, interleukin-4 is known to induce VCAM-1 expression and not ICAM-1 or E-selectin, while TNF-α induces the expression of all three. This difference shows how various disease states can have different effects on the same pathological processes. Further studies are needed to parse out the exact mechanism behind this activation in HGPS viTEBVs. Nonetheless, this work indicates that the endothelium may play a role in atherosclerotic development in HGPS and emphasizes the need to further evaluate the role of these cells in this complex disease state.

Experimental Procedures

Cell Isolation and Culture

Primary skin fibroblasts with the classic G608G HGPS mutation (HGADFN167 clones 2 and 6) and control primary skin fibroblasts (HGFDFN168, clones 2, 3, and 6) were provided by the Progeria Research Foundation and converted to iPSCs by the Duke iPSC Shared Resource Facility. hiPSCs with the classic G608G HGPS mutation (HGPS003, clones 1B, 1C, and 1D) were provided by the Progeria Research Foundation. The normal iPSC line DU11 was converted from the fibroblast line BJ, human foreskin fibroblast line generated from a young postnatal male (Thermo Fisher Scientific). hiPSCs were maintained in feeder-free conditions on hESC-qualified Matrigel (BD Biosciences) in mTeSR1 (STEMCELL Technologies). Cells were passaged at 80%–90% confluency with Accutase (STEMCELL Technologies) and 10 μM ROCK inhibitor Y-27632 (Tocris Bioscience).

hCB-ECs were derived from human umbilical cord blood obtained from the Carolina Cord Blood Bank, and all patient identifiers were removed before receipt. Isolation and culture protocols for hCB-ECs were approved by the Duke University institutional review board and hCB-ECs were derived as described previously (Ingram et al., 2004). hCB-ECs were cultured in EBM-2 (Lonza, Basel, CH, Switzerland) supplemented with EGM-2 Single Quots Kit (Lonza), 1% Pen/Strep (Gibco Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY), and 10% FBS (HI-FBS, Gibco). Medium was changed every other day. hCB-ECs at passages 4–9 were used for all experiments.

viSMC and viEC Differentiation

viSMCs and viECs were differentiated using a modified protocol as described previously (Patsch et al., 2015). In brief, for all differentiations, hiPSCs were dissociated on day 0 with Accutase and replated on Matrigel-coated plates at a density of 37,000–47,000 cells/cm2. It was found that viSMCs differentiated well at lower densities (37,000 cells/cm2), while viECs required higher (47,000 cells/cm2) densities for efficient differentiation for all hiPSC lines. This should be optimized for each specific hiPSC or ESC cell line as this protocol was optimized for the iPSC lines used in this study. On day 1, the medium was replaced with mesoderm induction medium containing N2B27 medium (1:1 mix of Neurobasal and DMEM/F12 with GlutaMAX and supplemented with N2 and B27 (−) vitamin A, all Life Technologies) with 25 ng/mL BMP4 (PeproTech) and 8 μM CHIR99021 (Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, MI). The media were not changed for 3 days to induce a mesoderm state.

For viSMC differentiation, on day 4 the medium was changed to viSMC induction medium consisting of N2B27 medium supplemented with 10 ng/mL PDGF-BB (PeproTech) and 2 ng/mL Activin A (PeproTech). The viSMC induction medium was changed daily. On day 6, cells were dissociated with Accutase and replated on collagen-coated plates in viSMC medium containing 2 ng/mL Activin A and 2 μg/mL heparin (Sigma) to induce a contractile SMC phenotype. The medium was changed every other day and viSMCs were routinely passaged at 80%–90% confluency using Accutase onto collagen-coated plates and continuously cultured in viSMC medium. HGPS viSMCs were used between passages 4–7 and normal viSMCs were used at passages 2–5.

For viEC differentiation, on day 4 the medium was changed to viEC induction medium consisting of Stempro-34 SFM medium (Life Technologies) supplemented with 200 ng/mL VEGF165 (GenScript) and 2 μM forskolin (Sigma). The viEC induction medium was changed daily and conditioned medium was collected on days 5, 6, and 7 to create viEC-conditioned medium consisting of 1:1 fresh Stempro-34 SFM and the collected conditioned medium. On day 7, viECs were dissociated with Accutase and fluorescence-activated cell sorting separated for CD31+ CD144+ cells.

viEC Flow-Assisted Cell Sorting

On day 7 of the viEC differentiation, cells were dissociated with Accutase and neutralized with cold Stempro-34 SFM medium. Cells were spun at 1,000 rpm for 5 min and then washed with MACS buffer containing DPBS with 0.5% BSA and 2 mM EDTA. Cells were resuspended in 200 μL MACS buffer and co-stained for 30 min on ice with 10 μL pre-conjugated FITC CD31 (BioLegend) antibody and PE CD144 (BioLegend) antibody. Cells were rinsed once with MACS buffer and sorted on a Beckman Coulter Astrios Sorter at the Duke Flow Cytometry Shared Resource Facility. Cells were then replated on collagen-coated plates and cultured in viEC-conditioned medium during passage 0 directly after sorting. Media were changed every other day. viECs were routinely passaged at 80%–90% confluency using Accutase onto collagen-coated plates and continuously cultured in viEC medium consisting of Stempro-34 SFM medium with 10% HI-FBS, 50 ng/mL VEGF165, and 2 μg/mL heparin after passage 1. HGPS and normal viECs were used between passages 1 and 4.

viTEBV Fabrication and Functional Testing

viTEBVs were fabricated as described previously (Fernandez et al., 2016, Ji et al., 2016). In brief, 1.5 × 106 normal or HGPS viSMCs were dissociated with Accutase and resuspended in 300 μL of viSMC medium and incorporated in a 2.05 mg/mL rat tail collagen type 1 solution (Corning, Corning, NY) in 0.6% acetic acid. Serum-free 10× DMEM (Sigma Aldrich, Raleigh, NC) was added at a 1:10 ratio to the collagen solution. The pH of the solution was raised to 8.5 by adding 5 M NaOH, causing gelation. Before complete gelation, the solution was placed in a 3-mL syringe mold (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) with the stopper completely removed and a two-way luer lock stopcock attached to the luer lock end of the syringe. An 800-μm diameter steel mandrel was inserted in the middle of the solution in the syringe and held in the center with parafilm wrapped over the syringe opening. The solution gelled for 30 min at room temperature before compression. After gelation, the vessel construct was transferred onto 0.2-μm nylon filter paper (Whatman, Maidstone, UK) on 10 KimWipes. Plastic compression was applied to the construct by suspension in the filter paper for 7 min to remove over 90% of the water content. Once compressed, the TEBVs were placed in custom perfusion chambers and sutured onto grips at both ends.

After gelation and mounting, TEBVs were endothelialized by dissociating adherent hCB-ECs, normal viECs, or HGPS viECs with 0.05% Trypsin/EDTA (Lonza) or Accutase, respectively. The ECs were resuspended at 0.5 × 106 cells in 0.5 mL respective media (EGM2 or viEC media). hCB-ECs or viECs were perfused through the lumen using 1 mL luer lock syringes (BD) connected to the grips of the custom chambers. The TEBVs were evenly endothelialized by rotating the chambers at 10 revolutions per hour for 30 min at 37°C on a rotator. Chambers were attached to a flow circuit containing a 25-mL media reservoir connected by tubing. Continuous, steady, laminar flow at 2 mL/min was applied to the TEBVs by attaching the perfusion circuit to a peristaltic pump that applied a physiological shear stress of 6.8 dynes/cm2 (Masterflex, Gelsenkirchen, Germany). The TEBVs were matured for up to 6 weeks and the medium was changed three times per week. All TEBVs were perfused in viSMC medium.

Vessel vasoactivity was calculated as the change in diameter of the TEBVs after exposure to 1 μM phenylephrine (Sigma) and 1 μM acetylcholine (Sigma). Vasoactivity was measured in the same perfusion circuit that TEBVs were cultured in at room temperature and imaged using a stereoscope (AmScope) while being recorded with ISCapture software. After 30 s of normal perfusion, 1 μM phenylephrine was added to a syringe port (Ibidi) integrated in the flow circuit, and after 5 min 1 μM acetylcholine was added. This process was performed weekly for all studies. Screen shots were taken at 30 s (before phenylephrine addition) to establish baseline, at 5 min (after phenylephrine addition), and at 10 min (after acetylcholine addition). The diameter at each time point was determined by averaging four random widths along the length of the vessel using ImageJ. Vessel diameter measurements were defined at the 30-s time point. Vasoconstriction in response to phenylephrine was calculated as the percent change in diameter from the initial diameter at 30 s before addition of phenylephrine to the diameter at 5 min after addition of phenylephrine. The vasodilation in response to acetylcholine was calculated as the percent change in diameter from the constricted state at 5 min to the diameter at 10 min.

Flow Cytometry Analysis

viSMC and viEC purity was characterized using flow cytometry. Cells were dissociated using Accutase for 3 min (viSMCs) or 1.5 min (viECs) and washed once with DPBS. viSMCs were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 min and permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X- for 5 min. Cells were incubated with 10% goat serum for 30 min at room temperature and then primary antibody was directly added to the cell suspension and incubated for 1 h at room temperature. Unstained cells and isotype-stained cells were used as controls. Cells were washed with DPBS and then incubated with secondary antibodies in 10% goat serum for 1 h at room temperature. Cells were washed twice with DPBS and flow cytometry was run by collecting 10,000 events per sample. Dissociated viECs were stained with fluorophore-conjugated antibodies for CD31 (BioLegend) and CD144 (BD Pharmingen) for 30 min on ice, then washed with DPBS. Unstained and isotype-stained cells were used as controls. Flow cytometry was run by collecting 10,000 events per sample.

Burst Pressure Testing

TEBV burst pressure was measured as described previously (Fernandez et al., 2016). In brief, TEBVs were sealed off at the outlet grip while attached to their respective perfusion chamber. The inlet grip was attached to a differential pressure gauge connected to tubing that was hooked to an air pump and filled with water. TEBVs were filled with water until failure and the maximum pressure at failure was recorded.

qRT-PCR and Primers

Total RNA was extracted from normal and HGPS viECs and viTEBVs using the Aurum Total RNA Mini Kit (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) and an RNeasy Mini Kit (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany). For assessment of TEBV gene expression, TEBV viSMCs and lumen viECs were not separated during RNA extraction to increase RNA yield. RNA was reverse transcribed into cDNA using the iScript cDNA Synthesis Kit (Bio-Rad). RT-PCR was performed in triplicate using the iQ SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad) and the CFX Connect Real-Time PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad). Human GAPDH served as an internal control (VHPS-3541, Real-time primers, Elkins Park, PA). Primer sequences for human PROGERIN, KLF2, NRF2, NQO1, HO-1, TXNRD1, GCLC, GCLM, and NOS3 (eNOS) are listed in Table S1. To account for variability between separate experiments, a normalization factor was calculated by dividing the global average of all conditions within each group by the average of each experiment (Cheng et al., 2016). Normalized values were calculated for each experiment by scaling each data point by the normalization factor of the experiment.

Nitric Oxide Assay

After 1 week of perfusion and 48 h after medium change, 5 mL of medium was removed from the flow circuit and frozen at −20°C. Proteins were removed from the samples and medium used for the standard curve before testing with a 10,000 MWCO spin column (Corning) spun at 10,000 rpm for 7 min. Total nitrate and nitrite were measured using a Colorimetric Assay Kit (Cayman Chemical) as per the kit instructions. Standard curves were measured in medium rather than the provided assay buffer due to the effects of media components (2-mercaptoethanol) on the measured absorbance. Absorbance was measured at 540 nm using a μQuant microplate reader (Bio-Tek). Samples and standards were normalized to pure medium.

viEC Flow Alignment Studies

The effect of physiological shear stresses on HGPS and normal viECs was evaluated as described previously (Fernandez et al., 2014, Mathur et al., 2002). In brief, viECs were seeded at a confluent density onto slide flasks (Nunc) or collagen-coated glass slides and allowed to attach and develop a confluent monolayer in the flasks. Once fully confluent, flasks were incorporated in a previously designed parallel plate flow chamber connected to a circular flow loop. Steady laminar flow was applied using a pre-conditioning treatment as described previously (Mathur et al., 2002) to maintain cell attachment. Once 12 dynes/cm2 was reached, cells were maintained in the flow circuit for 24 h. Alignment was determined by measuring the angle of the cell relative to the direction of flow in ImageJ. An angle of 0° indicated complete alignment and 45° indicates no alignment. Roundness was determined using the following equation:

where A is the cell area and L is the chord length. A roundness of 1 indicates a perfect circle and a roundness of 0 indicates a straight line. For each experiment, orientation and roundness were averaged from measurements of 90–150 cells in each experiment. Two to three flow and corresponding static control experiments were performed for each cell line or clone.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was done using JMP Pro 13 (SAS). Data were analyzed using a one- or two-way ANOVA and post-hoc Tukey test to compare means. Before running the ANOVA, a Levene's test was performed to determine equality of variance. All cases exhibited p > 0.05 and the ANOVA was performed. Repeated measures ANOVA was used for time-dependent assays. Data are represented as mean ± SEM with n = number of independent experiments; p ≤ 0.05 was considered significant.

Author Contributions

L.A., G.A.T., and K.C. designed the project. L.A., N.O.A., E.S.-M., A.L., T.R., and Y.G. performed the experiments. L.A., N.O.A., E.S.-M., A.L., T.R., K.C., and G.A.T. analyzed the data. K.C. and G.A.T. provided reagents. L.A., N.O.A., G.A.T., and K.C. wrote and edited the paper.

Acknowledgments

We thank members of the Cao Lab (University of Maryland) for advice, data analysis, and scholarly discussion, particularly, Dr. Zheng-Mei Xiong. This work was supported by NIH grant R01 HL138252-01 (to G.A.T.), UH3TR000505 (to G.A.T.), UH3TR002142 (to G.A.T.), NSF GRFP grant no 1106401 (to L.A.), and NSF GRFP grant no. DGE1644868 (to N.O.A.). iPSCs from healthy and HGPS individuals were generously provided by the Progeria Research Foundation.

Published: February 6, 2020

Footnotes

Supplemental Information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stemcr.2020.01.005.

Accession Numbers

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Supplemental Information

References

- Atchison L., Zhang H., Cao K., Truskey G.A. A tissue engineered blood vessel model of Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome using human iPSC-derived smooth muscle cells. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:8168. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-08632-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonello-Palot N., Simoncini S., Robert S., Bourgeois P., Sabatier F., Levy N., Dignat-George F., Badens C. Prelamin A accumulation in endothelial cells induces premature senescence and functional impairment. Atherosclerosis. 2017;237:45–52. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2014.08.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown M.A., Wallace C.S., Angelos M., Truskey G.A. Characterization of umbilical cord blood-derived late outgrowth endothelial progenitor cells exposed to laminar shear stress. Tissue Eng. A. 2009;15:3575–3587. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2008.0444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng C.S., Ran L., Bursac N., Kraus W.E., Truskey G.A. Cell density and joint microRNA-133a and microRNA-696 inhibition enhance differentiation and contractile function of engineered human skeletal muscle tissues. Tissue Eng. A. 2016;22:573–583. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2015.0359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez C.E., Obi-onuoha I.C., Wallace C.S., Satterwhite L.L., Truskey G.A., Reichert W.M. Late-outgrowth endothelial progenitors from patients with coronary artery disease: endothelialization of confluent stromal cell layers. Acta Biomater. 2014;10:893–900. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2013.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez C.E., Yen R.W., Perez S.M., Bedell H.W., Povsic T.J., Reichert W.M., Truskey G.A. Human vascular microphysiological system for in vitro drug screening. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:21579. doi: 10.1038/srep21579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gimbrone M.A., García-Cardeña G. Endothelial cell dysfunction and the pathobiology of atherosclerosis. Circ. Res. 2016;118:620–636. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.115.306301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingram D.A., Mead L.E., Tanaka H., Meade V., Fenoglio A., Mortell K., Pollok K., Ferkowicz M.J., Gilley D., Yoder M.C. Identification of a novel hierarchy of endothelial progenitor cells using human peripheral and umbilical cord blood. Blood. 2004;104:2752–2760. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-04-1396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji H., Atchison L., Chen Z., Chakraborty S., Jung Y., Truskey G.A., Christoforou N., Leong K.W. Transdifferentiation of human endothelial progenitors into smooth muscle cells. Biomaterials. 2016;85:180–194. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2016.01.066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan B.V., Harrison D.G., Olbrych M.T., Alexander R.W., Medford R.M. Nitric oxide regulates vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 gene expression and redox-sensitive transcriptional events in human vascular endothelial cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 1996;93:9114–9119. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.17.9114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim C. Disease modeling and cell based therapy with iPSC: future therapeutic option with fast and safe application. Blood Res. 2014;49:7–14. doi: 10.5045/br.2014.49.1.7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim M., Kim S., Lim J.H., Lee C., Choi H.C., Woo C.-H. Laminar flow activation of ERK5 protein in vascular endothelium leads to atheroprotective effect via NF-E2-related factor 2 (Nrf2) activation. J. Biol. Chem. 2012;287:40722–40731. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.381509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubben N., Zhang W., Wang L., Voss T.C., Yang J., Qu J., Liu G., Misteli T. Repression of the antioxidant NRF2 pathway in premature aging. Cell. 2016;165:1361–1374. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathur A.B., Truskey G.A., Reichert W.M. Synergistic effect of high-affinity binding and flow preconditioning on endothelial cell adhesion. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A. 2002;64A:155–163. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.10403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olive M., Harten I., Mitchell R., Beers J., Djabali K., Cao K., Erdos M.R., Blair C., Funke B., Smoot L., Gordon L.B. Cardiovascular pathology in Hutchinson-Gilford progeria: correlation with the vascular pathology of aging. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2010;30:2301–2309. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.110.209460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osmanagic-Myers S., Kiss A., Manakanatas C., Hamza O., Sedlmayer F., Szabo P.L., Fischer I., Fichtinger P., Podesser B.K., Eriksson M., Foisner R. Endothelial progerin expression causes cardiovascular pathology through an impaired mechanoresponse. J. Clin. Invest. 2019;129:531–545. doi: 10.1172/JCI121297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patsch C., Challet-Meylan L., Thoma E.C., Urich E., Heckel T., O’Sullivan J.F., Grainger S.J., Kapp F.G., Sun L., Christensen K., Cowan C.A. Generation of vascular endothelial and smooth muscle cells from human pluripotent stem cells. Nat. Cell Biol. 2015;17:994–1003. doi: 10.1038/ncb3205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajendran P., Rengarajan T., Thangavel J., Nishigaki Y., Sakthisekaran D., Sethi G., Nishigaki I. The vascular endothelium and human diseases. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2013;9:1057–1069. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.7502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tzima E., Irani-Tehrani M., Kiosses W.B., Dejana E., Schultz D.A., Engelhardt B., Cao G., DeLisser H., Schwartz M.A. A mechanosensory complex that mediates the endothelial cell response to fluid shear stress. Nature. 2005;437:426. doi: 10.1038/nature03952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong Z.-M., Choi J.Y., Wang K., Zhang H., Tariq Z., Wu D., Ko E., LaDana C., Sesaki H., Cao K. Methylene blue alleviates nuclear and mitochondrial abnormalities in progeria. Aging Cell. 2016;15:279–290. doi: 10.1111/acel.12434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yap B., Garcia-Cardena G., Gimbrone M.A. Endothelial dysfunction and the pathobiology of accelerated atherosclerosis in Hutchinson-Gilford Progeria syndrome. FASEB J. 2008;22(Suppl 1):471.11. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J., Lian Q., Zhu G., Zhou F., Sui L., Tan C., Mutalif R.A., Navasankari R., Zhang Y., Tse H.F. A human iPSC model of Hutchinson Gilford Progeria reveals vascular smooth muscle and mesenchymal stem cell defects. Cell Stem Cell. 2011;8:31–45. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H., Xiong Z.-M., Cao K. Mechanisms controlling the smooth muscle cell death in progeria via down-regulation of poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase 1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2014;111:E2261–E2270. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1320843111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.