Abstract

Individual condition at one stage of the annual cycle is expected to influence behaviour during subsequent stages, yet experimental evidence of food-mediated carry-over effects is scarce. We used a food supplementation experiment to test the effects of food supply during the breeding season on migration phenology and non-breeding behaviour. We provided an unlimited supply of fish to black-legged kittiwakes (Rissa tridactyla) during their breeding season on Middleton Island, Alaska, monitored reproductive phenology and breeding success, and used light-level geolocation to observe non-breeding behaviour. Among successful breeders, fed kittiwakes departed the colony earlier than unfed controls. Fed kittiwakes travelled less than controls during the breeding season, contracting their non-breeding range. Our results demonstrate that food supply during the breeding season affects non-breeding phenology, movement and distribution, providing a potential behavioural mechanism underlying observed survival costs of reproduction.

Keywords: movement ecology, full annual cycle, carry-over effects, solar geolocation, migration, food

1. Introduction

Reproduction is an expensive life event, costing time, energy and future reproductive value [1–3]. In iteroparous organisms, the allocation of these resources can affect outcomes of the breeding season (within-season effects) and subsequent seasons or life stages (carry-over effects [4,5]). The most commonly reported carry-over effect is a cost of reproduction, whereby breeding incurs costs that are paid via reduced non-breeding survival [6,7]. However, detecting the costs of reproduction can be difficult because greater access to resources allows some individuals to invest more towards both reproduction and survival, mitigating some of the trade-off between current and subsequent reproduction [8,9]. For example, food supplementation experiments often increase the body condition of both parents (survival) and offspring (reproduction, [10–12]). By contrast, individuals in poor pre-breeding condition may shift resources towards self-maintenance by delaying reproduction beyond dates that would optimize offspring survival [1]. While there is a large consensus that costs of reproduction (i.e. reductions in survival) occur widely, especially for migratory species where time and energy spent during breeding leaves individuals in reduced condition for subsequent migrations, it is less clear when within the annual cycle these trade-offs occur.

Understanding mechanisms of carry-over effects requires an experimental approach and, until recently, has been difficult to pinpoint in long-distant migrants due to the challenges of observing animals across seasons. In the past decade, experimental work has produced mechanisms driving carry-over effects on subsequent behaviour and breeding success across taxa (e.g. birds [13], mammals [14], fishes [15], insects [16]). Differences in nutrient stores at season transitions are posed as the primary driver of carry-over effects [5] through mechanisms such as physiological stress [17,18]. For example, reduced winter food supply can decrease body condition and delay spring migration [19] and increased winter food supply can increase breeding success the following summer [20]. Conversely, food availability in the breeding season could influence non-breeding behaviour, in addition to (or combined with) their immediate effects on breeding success.

Several observational studies indicate food availability in one season can affect subsequent behaviour and reproductive outcomes [21–24]. Within the breeding season, food supplementation experiments often demonstrate that increased food advances the timing of reproduction and increases breeding success [10], suggesting that energy status limits both timing of reproduction and reproductive output [1]. Increased food reduces the energetic costs of reproduction [25], indeed individuals with insufficient food resources may fail to reproduce or abandon their breeding attempt, diverting investment from reproduction towards self-maintenance. Thus, food availability can affect reproductive phenology, reproductive success and individual condition, which may subsequently produce carry-over effects at any point throughout the annual cycle.

Potential mechanisms for increased investment in reproduction to cause a survival cost in migratory animals include: (i) a longer breeding season delays migration and individuals with poor resources cannot migrate long distances to productive regions, (ii) a delayed migration causes individuals to occupy lower quality habitats when they arrive on wintering grounds because optimal habitats are already occupied and (iii) individuals with reduced energy reserves at the end of breeding have shorter fasting endurance and require more stopovers, leading to more searching for patches and larger area covered. Each of these mechanisms could lead to reduced survival through starvation.

We used an experimental approach to determine the role of summer food supply on the whole annual cycle of black-legged kittiwakes (Rissa tridactyla), a species in which survival increased after experimental reduction in costs of reproduction [7]. Using a combination of observation at the breeding colony and light-level geolocation during the non-breeding season, we tested the hypothesis that summer food supply affects phenology, reproductive and maintenance investments within the breeding season, which produce cascading effects on behaviour in the non-breeding season. Earlier work has already shown that food-supplemented birds breed earlier and more successfully [11,26], which we confirm. We predicted that, relative to controls, fed kittiwakes would be in better body condition at the end of the breeding season, and have a lower cost of reproduction as demonstrated by (i) earlier departure from the breeding colony, (ii) shorter travel distances during winter and (iii) earlier arrival the following spring.

2. Material and methods

(a). Study system

We monitored 108 black-legged kittiwakes throughout their breeding season on Middleton Island, Alaska (59.48 N, 146.38 W) over 3 years (2009: n = 20; 2010: n = 30; 2011: n = 58, electronic supplementary material, table S1). The kittiwakes nest on an abandoned radar tower equipped with one-way mirrored windows. We considered a breeding attempt successful if at least one chick fledged. We provided a subset of kittiwake pairs with unlimited fish (capelin, Mallotus villosus) via a PVC tube at their nest site, three times daily from May until mid-August (details in [11]), until the breeding attempt failed or chicks fledged. We observed nest contents twice daily to determine the laying date, egg loss, chick loss and fledge date. In late summer, we captured the birds to measure body condition (via body mass and skull length) and deployed leg-mounted, light-level geolocators (2.5 g, Mk9, British Antarctic Survey). We recaptured birds the following spring to retrieve geolocators. The devices recorded a maximum light level and conductivity (wet/dry) at 10 min intervals.

(b). Non-breeding movement

We visually examined all twilights in GeoLight [27] with a light threshold of 30. All geolocators ran for the duration of the non-breeding season, so we used both a deployment and retrieval calibration period (10 days post-deployment; 10 days pre-retrieval), and estimated locations with FLightR [28]. For each geolocation track, we calculated the date of autumn departure from the colony, date of spring arrival to the colony, total distance travelled during the non-breeding season and maximum distance from the colony. Visual inspection of location estimates revealed that migratory movements generally extended west or southeast of Middleton Island (electronic supplementary material, figure S1), and the population exhibited partial migration (electronic supplementary material, figure S2). Because longitudinal estimates are more accurate than latitudinal estimates [29], we defined autumn departure as the first date each individual travelled over three longitudinal degrees (approx. 330 km) from the colony, and spring arrival as the final date the individual entered within three longitudinal degrees from the colony. We excluded 15 individuals from models of departure and arrival date because they left or returned during winter (i.e. departed after 1 December, arrived before 1 January) or stayed within 3° from the colony. We calculated the distance travelled as the sum of the distance between locations from the latest geolocator deployment (1 August) to the earliest retrieval (12 April). In doing so, we standardized the number of locations for each track (range: 505–510 location estimates per track) and produced a measure of total movement relevant for both migratory and non-migratory individuals.

(c). Statistical analyses

We conducted all spatial and statistical analyses in R (v. 3.5.1 [30]). Several birds were followed for multiple years, so we fitted linear and generalized linear mixed-effect models (LMM and GLMM) with lme4 [31] that included individual and year as random intercepts. We tested the statistical significance of fixed effects in LMM with single term deletions (Kenward–Roger's approximation for degrees of freedom [32]), and likelihood ratio tests (LRT) for the significance of fixed effects in GLMM.

To determine the impact of food treatment within the breeding season, we modelled laying date (first egg date, of final clutch if relaid; LMM), number of fledglings produced (poisson GLMM) and fledging date (date single or final chick fledged, fledging age assumed to be 43 days if not observed; LMM) in response to food treatment (fed/control).

To determine the effect of food supply on late-summer body condition, we first calculated late-summer body condition as residuals from a linear regression of body mass in response to skull length (LM), which correlates with lipid content in kittiwakes [33]. We then modelled the body condition index in response to food treatment while controlling for sex (LMM).

To test the effects of food on non-breeding behaviour, we used LMM to model total distance travelled during the non-breeding season, date of autumn departure, and date of spring arrival in response to food treatment, sex, fledging success (0 = no chicks fledged; 1 = one or two chicks fledged) and an interaction between food treatment and fledging success. The full model of spring arrival date produced singular fits for random effects, so we reduced the fixed effects to food treatment and fledging success. We used Pearson's χ2-test to examine the effects of food treatment on migration propensity (Y/N) because models accounting for random structure produced singular fits. To assess individual consistency in non-breeding behaviour, we calculated adjusted repeatability using rptR (bootstrap = 1000, p-values via LRT [34]). Model results can be found in electronic supplementary material, table S2.

3. Results

(a). Within breeding season

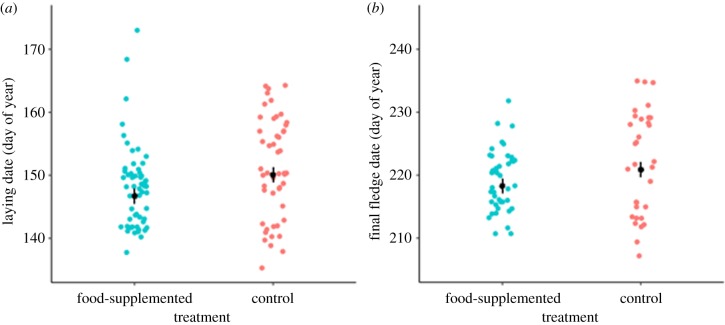

Food supplementation advanced laying phenology by about 3 days (3.3 ± 1.2 days, F1,71 = 7.8, p < 0.01; figure 1a) and although unfed individuals produced fewer fledglings (e−0.46 = 0.63 times fed birds; −0.40 ± 0.18, χ2 = 5.0, d.f. = 1, p < 0.05), final fledglings of unfed birds departed later than fledglings of fed birds (3.1 ± 1.2 days, F1,66 = 6.5, p = 0.73; figure 1b).

Figure 1.

Food supplementation advanced laying phenology (a) and fledging phenology (b). Black points show estimates from LMMs (±s.e.) and coloured points show raw values.

(b). Late-summer body condition

Individuals with larger skulls were heavier (6.9 ± 1.2 g, F1,104 = 35.6, p < 0.001), thus we used the residuals of the mass–skull regression as a size-corrected body condition index. We found that fed birds were 35 g heavier than control birds (35.4 g ± 5.4 g, F1,67 = 42.4, p < 0.001) and males were heavier than females (17.2 ± 5.5 g, F1,72 = 42.4, p < 0.01).

(c). Non-breeding season

We retrieved 96 out of 108 geolocators, of which 63 contained useable light data (electronic supplementary material, table S1). The population exhibited partial migration, with the majority of individuals overwintering southeast of the colony (figure 2a, electronic supplementary material, figure S1).

Figure 2.

(a) Non-breeding utilization distributions (95%) for food-supplemented (N = 32) and control (N = 31) kittiwakes over the 3 year study (2009–2012, circle marks Middleton Island). (b) Among successful breeders, fed kittiwakes departed the colony earlier than controls (p < 0.05). (c) Food supplementation decreased distance travelled during the non-breeding season (p < 0.01). Black points show estimates from LMM (for unsuccessful females, ±s.e.) and coloured points show raw values.

(i). Food supplementation

We found an interactive effect between food treatment and fledging success on autumn departure date (24.5 ± 0.6 days, F1,16 = 4.6, p < 0.05), where failed breeders departed the colony earlier than successful breeders and successful, fed breeders departed earlier than successful, control breeders (figure 2b). Spring arrival date remained similar regardless of food treatment (−4.4 ± 5.7 days, F1,33 = 0.56, p = 0.46; electronic supplementary material, figure S2) and fledging success in the previous year (5.8 ± 6.5 days, F1,40 = 1.07, p = 0.31).

Control birds travelled greater distances in the non-breeding season than fed birds (2560 ± 810 km, F1,48 = 9.7, p < 0.01; figure 2c; electronic supplementary material, figures S3 and S4) and males travelled shorter distances than females (−1903 ± 852 km, F1,45 = 4.9, p < 0.05), but fledging success did not influence distance travelled (1243 ± 822 km, F1,48 = 2.1, p = 0.16). Food treatment did not predict migration propensity (χ2 = 2.4, d.f. = 1, p = 0.12).

(ii). Individual consistency

We retrieved multiple years of geolocation data for 16 individuals (electronic supplementary material, figure S5). We found evidence for individual consistency in departure date (R = 0.739 ± 0.11, CI = [0.517,0.95], p < 0.01), non-significant repeatability for distance travelled during the non-breeding season (R = 0.35 ± 0.22, CI = [0,0.83], p < 0.12), and marginally non-significant repeatability for spring arrival date (R = 0.39 ± 0.23, CI = [0,0.83], p = 0.060).

4. Discussion

Using an experimental approach, we show that food supply in the breeding season influences the subsequent non-breeding movement of black-legged kittiwakes. Increasing summer food supply advanced autumn departure from the breeding grounds, but only among successful breeders. Summer food supply also affected non-breeding movement and distribution, in that food-supplemented individuals travelled smaller distances and contracted their non-breeding range. However, fed and control individuals returned to the breeding grounds at a similar time the following spring.

Summer food supply influenced non-breeding behaviour via the costs of reproduction and shifts in breeding phenology. The effect of summer food supply on autumn departure depended on breeding success, indicating that reduced investment towards reproduction, whether through lower costs of reproduction (fed group) or termination of reproductive attempts (control group), advanced autumn migration. These results are consistent with two experimental studies of differential resource allocation during the breeding season on the migratory behaviour of seabirds [35,36], where individuals that invested less in reproduction departed earlier. If food supply affects the timing of autumn departure by advancing spring phenology, we expected later fledging among the individuals with less food. Feeding advanced spring laying dates—a classic effect of food supplementation [10]—and fledging dates were subsequently earlier in the fed treatment group. However, the later-laying control individuals fledged fewer young, while fed individuals were able to produce additional young without the penalty of later departure. Later departures within the successful control breeders, may, therefore, be driven by differences in investment towards self-maintenance. For example, fed birds were in better body condition in late summer, which is consistent with life-history predictions [8].

Summer food supply could influence non-breeding behaviour through effects on individual condition, whereby individuals with more food are in better condition as they transition to the non-breeding season. Body condition is often linked to the timing of spring migration [19,37], but the role of the condition in the timing of autumn migration is less clear in this system because there are no immediate benefits to earlier arrival on wintering grounds. A previous study found kittiwakes that overwintered at northern locations increased foraging effort during daylight hours [38]; greater foraging efficiency or endurance is required to overwinter in the North Pacific, with short days and low primary productivity. In our study, fed kittiwakes entered the non-breeding season in better body condition than controls and travelled less. Individuals in better condition may migrate shorter distances because they have greater tolerance of harsh winter conditions. However, macronutrient stores are only one of many potential physiological mechanisms that may drive the observed carry-over effects.

Our 3 year study fell within a period of relatively high breeding success for the Middleton Island colony associated with cold ocean conditions and capelin-rich kittiwake diet [39]. Reproductive and behavioural differences between the food-supplemented and control groups are smaller during ‘good years’ [40]. Despite the timing of the study and modest migration distance, we found clear differences in the non-breeding movement due to food supply. In years of lower natural food supply, or in a population with greater migration distance, the differences between treatment groups might have been greater. However, food supply did not appear to drive patterns in partial migration (i.e. no difference in migration propensity).

Variation in non-breeding behaviour—driven by costs of reproduction—in this study could be the behavioural mechanism underlying overwinter survival costs of reproduction observed at a nearby colony [7]. However, we are not able to test for carry-over effects of food supply on fitness here because individuals were fed every summer as part of a long-term food supplementation programme [11]. Therefore, we could not distinguish the effects of current food supplementation from carry-over effects of previous years of food supplementation, and it is possible that the fed birds are a self-selecting portion of the population (e.g. superior competitors for high-quality, fed nest sites). This would require a detailed demographic analysis testing effects of the long-term food supplementation on lifetime reproductive success and survival.

Our study demonstrates that food supply during one stage of the annual cycle can impact subsequent movement behaviour. Although departure phenology was repeatable within individuals, non-breeding behaviour was plastic to different levels of food supply among individuals. It follows that non-breeding ranges may shift with changes in the food supply. Continued pressure on ocean fish stocks through fisheries depletion [41] or climate change [42] could affect summer foraging and breeding performance with consequences for migration and non-breeding outcomes. Long-term monitoring of non-breeding movement through biologging devices holds the potential to observe human-induced shifts in animal migrations and distributions.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank the Middleton Island field technicians. Jonathan Green and two anonymous reviewers provided comments that greatly improved the manuscript.

Ethics

All work was approved by a USGS Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee, with permits from the US Fish and Wildlife Service (MB01629B-2) and Alaska Department of Fish and Game (ADFG 11-08).

Data accessibility

Supporting data and code are provided as electronic supplementary material, and were available to reviewers upon submission.

Authors' contributions

S.W. analysed the data and drafted the manuscript. S.A.H. and D.B.I. conceived of the study, K.H.E. and S.A.H. collected the data, A.M. prepared the data and contributed analyses. All authors made critical revisions to the manuscript, agree to be held accountable for the content therein and approve the final version of the manuscript.

Competing interests

We declare we have no competing interests.

Funding

This work was supported by NSERC (S.W., K.H.E.), a Mackenzie-Munroe Fellowship (S.W.), a Canada Research Chair in Arctic Ecology (K.H.E.), the US Geological Survey, US Fish and Wildlife Service and Institute for Seabird Research and Conservation (S.A.H.).

References

- 1.Drent R, Daan S. 1980. The prudent parent. Ardea 68, 225–252. ( 10.5253/arde.v68.p225) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reznick D. 1985. Costs of reproduction: an evaluation of the empirical evidence. Oikos 44, 257–267. ( 10.2307/3544698) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stearns SC. 1992. The evolution of life histories. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Norris DR. 2005. Carry-over effects and habitat quality in migratory populations. Oikos 109, 178–186. ( 10.1111/j.0030-1299.2005.13671.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Harrison XA, Blount JD, Inger R, Norris DR, Bearhop S. 2011. Carry-over effects as drivers of fitness differences in animals. J. Anim. Ecol. 80, 4–18. ( 10.1111/j.1365-2656.2010.01740.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Daan S, Deerenberg C, Dijkstra C. 1996. Increased daily work precipitates natural death in the kestrel. J. Anim. Ecol. 65, 539–544. ( 10.2307/5734) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Golet GH, Irons DB, Estes JA. 1998. Survival costs of chick rearing in black-legged kittiwakes. J. Anim. Ecol. 67, 827–841. ( 10.1046/j.1365-2656.1998.00233.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Van Noordwijk AJ, de Jong G. 1986. Acquisition and allocation of resources: their influence on variation in life history tactics. Am. Nat. 128, 137–142. ( 10.1086/284547) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reznick D, Nunney L, Tessier A. 2000. Big houses, big cars, superfleas and the costs of reproduction. Trends Ecol. Evol. 15, 421–425. ( 10.1016/S0169-5347(00)01941-8) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boutin S. 1990. Food supplementation experiments with terrestrial vertebrates: patterns, problems, and the future. Can. J. Zool. 68, 203–220. ( 10.1139/z90-031) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gill VA, Hatch SA. 2002. Components of productivity in black-legged kittiwakes Rissa tridactyla: response to supplemental feeding. J. Avian Biol. 33, 113–126. ( 10.1034/j.1600-048X.2002.330201.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Welcker J, Speakman JR, Elliott KH, Hatch SA, Kitaysky AS. 2015. Resting and daily energy expenditures during reproduction are adjusted in opposite directions in free-living birds. Funct. Ecol. 29, 250–258. ( 10.1111/1365-2435.12321) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Legagneux P, Fast PL, Gauthier G, Bêty J. 2011. Manipulating individual state during migration provides evidence for carry-over effects modulated by environmental conditions. Proc. R. Soc. B 279, 876–883. ( 10.1098/rspb.2011.1351) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sanderson JL, Young AJ, Hodge SJ, Kyabulima S, Walker SL, Cant MA. 2014. Hormonal mediation of a carry-over effect in a wild cooperative mammal. Funct. Ecol. 28, 1377–1386. ( 10.1111/1365-2435.12307) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Roussel JM. 2007. Carry-over effects in brown trout (Salmo trutta): hypoxia on embryos impairs predator avoidance by alevins in experimental channels. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 64, 786–792. ( 10.1139/f07-055) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Elliott KH, Betini GS, Dworkin I, Norris DR. 2016. Experimental evidence for within and cross-seasonal effects of fear on survival and reproduction. J. Anim. Ecol. 85, 507–515. ( 10.1111/1365-2656.12487) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schultner J, Moe B, Chastel O, Tartu S, Bech C, Kitaysky AS. 2014. Corticosterone mediates carry-over effects between breeding and migration in the kittiwake Rissa tridactyla. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 496, 125–133. ( 10.3354/meps10603) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schultner J, Moe B, Chastel O, Bech C, Kitaysky AS. 2014. Migration and stress during reproduction govern telomere dynamics in a seabird. Biol. Lett. 10, 20130889 ( 10.1098/rsbl.2013.0889) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cooper NW, Sherry TW, Marra PP. 2015. Experimental reduction of winter food decreases body condition and delays migration in a long-distance migratory bird. Ecology 96, 1933–1942. ( 10.1890/14-1365.1) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Robb GN, McDonald RA, Chamberlain DE, Reynolds SJ, Harrison TJ, Bearhop S. 2008. Winter feeding of birds increases productivity in the subsequent breeding season. Biol. Lett. 4, 220–223. ( 10.1098/rsbl.2007.0622) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Madsen T, Shine R. 2000. Silver spoons and snake body sizes: prey availability early in life influences long-term growth rates of free-ranging pythons. J. Anim. Ecol. 69, 952–958. ( 10.1046/j.1365-2656.2000.00477.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Norris DR, Marra PP, Kyser TK, Sherry TW, Ratcliffe LM. 2004. Tropical winter habitat limits reproductive success on the temperate breeding grounds in a migratory bird. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 271, 59–64. ( 10.1098/rspb.2003.2569) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Descamps S, Boutin S, Berteaux D, McAdam AG, Gaillard JM. 2008. Cohort effects in red squirrels: the influence of density, food abundance and temperature on future survival and reproductive success. J. Anim. Ecol. 77, 305–314. ( 10.1111/j.1365-2656.2007.01340.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Montreuil-Spencer C, Schoenemann K, Lendvai ÁZ, Bonier F. 2019. Winter corticosterone and body condition predict breeding investment in a nonmigratory bird. Behav. Ecol. 30, 1642–1652. ( 10.1093/beheco/arz129) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jodice PG, Roby DD, Hatch SA, Gill VA, Lanctot RB, Visser GH. 2002. Does food availability affect energy expenditure rates of nesting seabirds? A supplemental-feeding experiment with black-legged Kittiwakes (Rissa tridactyla). Can. J. Zool. 80, 214–222. ( 10.1139/z01-221) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gill VA, Hatch SA, Lanctot RB. 2002. Sensitivity of breeding parameters to food supply in black-legged Kittiwakes Rissa tridactyla. Ibis 144, 268–283. ( 10.1046/j.1474-919X.2002.00043.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lisovski S, Hahn S. 2012. GeoLight—processing and analysing light-based geolocator data in R. Methods Ecol. Evol. 3, 1055–1059. ( 10.1111/j.2041-210X.2012.00248.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rakhimberdiev E, Saveliev A, Piersma T, Karagicheva J. 2017. FLightR: an R package for reconstructing animal paths from solar geolocation loggers. Methods Ecol. Evol. 8, 1482–1487. ( 10.1111/2041-210X.12765) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rakhimberdiev E, Winkler DW, Bridge E, Seavy NE, Sheldon D, Piersma T, Saveliev A. 2015. A hidden Markov model for reconstructing animal paths from solar geolocation loggers using templates for light intensity. Mov. Ecol. 3, 25 ( 10.1186/s40462-015-0062-5) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.R Core Team. 2019. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bates D, Maechler M, Bolker B, Walker S. 2014. lme4: linear mixed-effects models using Eigen and S4. R Package Version 1, pp. 1–23.

- 32.Kuznetsova A, Brockhoff PB, Christensen RHB. 2017. lmerTest package: tests in linear mixed effects models. J. Stat. Softw. 82, 1–26. ( 10.18637/jss.v082.i13) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jacobs SR, Elliott K, Guigueno MF, Gaston AJ, Redman P, Speakman JR, Weber JM. 2012. Determining seabird body condition using nonlethal measures. Physiol. Biochem. Zool. 85, 85–95. ( 10.1086/663832) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stoffel MA, Nakagawa S, Schielzeth H. 2017. rptR: repeatability estimation and variance decomposition by generalized linear mixed-effects models. Methods Ecol. Evol. 8, 1639–1644. ( 10.1111/2041-210X.12797) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Catry P, Dias MP, Phillips RA, Granadeiro JP. 2013. Carry-over effects from breeding modulate the annual cycle of a long-distance migrant: an experimental demonstration. Ecology 94, 1230–1235. ( 10.1890/12-2177.1) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fayet AL, Freeman R, Shoji A, Kirk HL, Padget O, Perrins CM, Guilford T. 2016. Carry-over effects on the annual cycle of a migratory seabird: an experimental study. J. Anim. Ecol. 85, 1516–1527. ( 10.1111/1365-2656.12580) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Studds CE, Marra PP. 2007. Linking fluctuations in rainfall to nonbreeding season performance in a long-distance migratory bird, Setophaga ruticilla. Clim. Res. 35, 115–122. ( 10.3354/cr00718) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McKnight A, Irons DB, Allyn AJ, Sullivan KM, Suryan RM. 2011. Winter dispersal and activity patterns of post-breeding black-legged kittiwakes Rissa tridactyla from Prince William Sound, Alaska. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 442, 241–253. ( 10.3354/meps09373) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hatch SA. 2013. Kittiwake diets and chick production signal a 2008 regime shift in the Northeast Pacific. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 477, 271–284. ( 10.3354/meps10161) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lanctot RB, Hatch SA, Gill VA, Eens M. 2003. Are corticosterone levels a good indicator of food availability and reproductive performance in a kittiwake colony? Horm. Behav. 43, 489–502. ( 10.1016/S0018-506X(03)00030-8) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jackson JB, et al. 2001. Historical overfishing and the recent collapse of coastal ecosystems. Science 293, 629–637. ( 10.1126/science.1059199) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Free CM, Thorson JT, Pinsky ML, Oken KL, Wiedenmann J, Jensen OP. 2019. Impacts of historical warming on marine fisheries production. Science 363, 979–983. ( 10.1126/science.aau1758) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Supporting data and code are provided as electronic supplementary material, and were available to reviewers upon submission.