Abstract

Background

Laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (LRYGB) and laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (LSG) are two representative bariatric surgeries. This study aimed to compare the effects of the LSG and LRYGB based on high-quality analysis and massive amount of data.

Methods

For this study databases of PubMed, Web of Science, EBSCO, Medline, and Cochrane Library were searched for articles published until January 2019 comparing the outcomes of LSG and LRYGB.

Results

This study included 28 articles. Overall, 9038 patients (4597, LSG group; 4441, LRYGB group) were included. The remission rate of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) in the LRYGB group was superior to that in the LSG group at the 3-years follow-up. Five-year follow-up results showed that LRYGB had an advantage over LSG for the percentage of excess weight loss and remission of T2DM, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and abnormally low-density lipoprotein.

Conclusions

In terms of the long-term effects of bariatric surgery, the effect of LRYGB was better than of LSG.

Keywords: Sleeve gastrectomy, Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, Effects, Meta-analysis

Background

Worldwide, obesity not only seriously affects the external appearance but also causes various diseases, which threaten people’s health. The usual way to lose weight is through dieting or medication use, which reduces weight by 5 to 10%. However, the resulting weight loss is short term, leading to rebound weight gain. Nowadays, bariatric surgery is widely known, as it has long-lasting effectiveness [1, 2]. Meanwhile, it can also alleviate some complications [3].

Laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (LRYGB) and laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (LSG) are two representative bariatric surgeries. The origin of LRYGB can be traced back to about 50 years ago. As LRYGB has excellent effectiveness on alleviating obesity complications, including type 2 diabetes (T2DM), it is known as the gold standard surgery for obese patients [4–8]. However, impaired micronutrient absorption is more common after LRYGB [9–11]. Some studies had shown that patients treated with LRYGB were more likely to have vitamin B12 deficiency after surgery than patients treated with LSG, but there was no difference in the absorption of folic acid and the effect on serum iron was controversial [11–14].

Moreover, conclusions of studies that compared LRYGB with LSG in the remission of complications remained controversial. Some studies indicated that LRYGB was superior to LSG [5, 15, 16] in the remission of T2DM, while other studies suggested that the remission rates were similar in both groups [17]. Previous studies had shown an advantage for LRYGB in the remission of hypertension [18–20]. With these differences in results, this study aimed to scientifically compare the advantages of LRYGB and LSG based on high-quality analysis and massive amount of data.

Methods

Literature search

This meta-analysis was in line with the recommendations of Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement [21]. Electronic literature search was conducted from inception to January 2019 of various databases including PubMed, EMBASE, Cochrane library, Web of Science, and EBSCO. The following keywords were used: (“laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass” OR “gastric bypass” OR “GB” OR “LRYGB”) AND (“laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy” OR “sleeve gastrectomy” OR “SG” OR “LSG”). Two researchers separately performed the literature search and compared their results. Most of the articles were screened manually by scanning titles and abstracts. Then, through a further check, all initially included studies were downloaded finally.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The primary outcomes of the studies included in the analysis were percentage of excess weight loss (%EWL) and remission rates of T2DM. The secondary outcomes of the studies were remission rates of hypertension and dyslipidemia. Published studies comparing the outcomes of LSG and LRYGB were considered potentially eligible. The follow-up time was at least 3 years. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) non-original article; (2) results did not include %EWL and remission rates of T2DM, hypertension, and dyslipidemia; and (3) no available medium-term (3-year) or long-term (5-year) original data or relevant outcome. Any unclear data were deleted decisively, and we made sure that all data were checked more than twice.

Data extraction and quality assessment

After multiple inspections, a list of articles that finally met the inclusion criteria was created, and a reviewer extracted the following basic indicators from each article (Table 1): study country and year, sample size, follow-up time, number of patients who completed the final follow-up, and study type. The indicators of %EWL and remissions of T2DM, hypertension, and dyslipidemia in each article were extracted.

Table 1.

Characteristics of studies included in the meta-analysis

| Author, year | Country | No. of participants | Follow-up (year) |

No. of remaining | Comorbidities remission (without medication) | Study type | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LSG | LRYGB | LSG | LRYGB | |||||

| Abbatini, 2010 | Italy | 20 | 16 | 3 | 20 | 16 | FPG < 126 mg/dl, HbA1c < 6.5% | Retrospective |

| Ahmed, 2018 | USA | 59 | 57 | 7 | 27 | 26 | NA | Prospective |

| Alexandrou, 2014 | Greece | 40 | 55 | 4 | 40 | 55 | NA | Prospective |

| Dakour Aridi, 2018 | Lebanon | 400 | 175 | 5 | 87 | 118 | NA | Retrospective |

| Boza, 2012 | Chile | 811 | 786 | 3 | 811 | 786 | FPG < 126 mg/dl, HbA1c < 6.5% | Retrospective |

| Carandina, 2014 | France | 34 | 74 | 4 | 34 | 74 | NA | Retrospective |

| Dogan, 2015 | Netherlands | 255 | 430 | 5 | 245 | 245 | NA | Retrospective |

| Du, 2016 | China | 63 | 63 | 3 | 60 | 59 | FPG < 5.6 mmol/l, HbA1c < 6%/BP < 120/80 mmHg | Retrospective |

| Climent, 2018 | Spain | 48 | 103 | 5 | 48 | 103 | NA | Retrospective |

| Gonzalez-Heredia, 2016 | USA | 77 | 12 | 3 | 30 | 8 | NA | Retrospective |

| Ignat, 2017 | France | 55 | 45 | 5 | 41 | 32 | NA | RCT |

| Jammu, 2016 | India | 339 | 295 | 5 | 97 | 143 | NA | Prospective |

| Jimenez, 2012 | Spain | 55 | 98 | 3 | 55 | 98 | FPG < 126 mg/dl, HbA1c < 6.5% for at least 1 year | Prospective |

| Kim, 2019 | Singapore | 256 | 39 | 3 | 71 | 10 | NA | Retrospective |

| Kaseja, 2014 | Poland | 33 | 41 | 3 | 33 | 41 | NA | Prospective |

| Lager, 2018 | USA | 334 | 380 | 4 | 226 | 272 | HbA1c < 6.5%/BP < 120/80 mmHg | Retrospective |

| Lee, 2015 | China | 519 | 519 | 5 | 116 | 218 | NA | Retrospective |

| Leyba, 2014 | Venezuela | 42 | 75 | 5 | 27 | 47 | HbA1c < 6% | Prospective |

| Perrone, 2017 | Italy | 162 | 142 | 5 | 162 | 142 | NA | Retrospective |

| Peterli, 2018 | Switzerland | 112 | 113 | 5 | 101 | 104 | FPG < 100 mg/dl, HbA1c < 6.0% at least 1 year | RCT |

| Rondelli, 2017 | Italy | 280 | 301 | 3 | 259 | 282 | NA | Retrospective |

| Ruiz-Tovar, 2019 | Spain | 200 | 200 | 5 | 182 | 184 | FPG < 110 mg/dl, HbA1c < 6.5%/BP < 135/85 mmHg/FPT < 200 mg/dl, TC < 200 mg/dl, HDL > 40 mg/dl | RCT |

| Salminen, 2018 | Finland | 121 | 119 | 5 | 98 | 95 | FPG < 100 mg/dl, HbA1c < 6.0%/LDL < 115.8 mg/dl | RCT |

| Sepulveda, 2018 | Chile | 57 | 55 | 3 | 41 | 35 | FPG < 100 mg/dl, HbA1c < 6.0% | Retrospective |

| Vidal, 2013 | Spain | 114 | 135 | 4 | 91 | 108 | NA | Retrospective |

| Yang, 2015 | China | 32 | 32 | 3 | 28 | 27 | HbA1c < 6.0% | RCT |

| Zhang, 2014 | China | 32 | 32 | 5 | 26 | 28 | NA | RCT |

| Schauer, 2017 | USA | 47 | 49 | 5 | 47 | 49 | HbA1c < 6.5% | RCT |

LSG laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy; LRYGB laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass; NA no available; FPG fasting plasma glucose; HbA1c glycosylated hemoglobin; BP blood pressure; FPT fasting plasma triglycerides; TC total cholesterol; LDL low-density lipoprotein; HDL high-density lipoprotein; RCT Randomized clinical trial

The quality of included articles was evaluated using the Cochrane risk-of-bias tool and the Newcastle-Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale (NOS) checklist [22, 23]. According to the recommendations of the Cochrane manual, the risk of bias in randomized controlled trial (RCTs) is categorized as low risk, unclear risk, and high risk. Observational studies were assessed by the NOS. Each article was evaluated in three aspects as follows: object selection, inter-group comparability, and outcome measurement. Articles with scores < 6 were considered low-quality articles. Any contradiction between reviewers was resolved by the consensus of two authors and the third reviewer.

Statistical analysis

RevMan 5.3 software was used to integrate statistical results. Weighted mean difference (WMD) was used to collect continuous variables, while odds ratios (OR) was used to analyze dichotomous variables. Heterogeneity was checked by Cochrane Collaboration’s risk of tool, chi-squared test, and I2 statistics and identified when p < 0.1 and I2 > 50%. If the results were heterogeneous, a random-effects model was used to calculate the combined effect size; otherwise, a fixed-effects model was used. The Stata 12.0 Software (Stata, College Station) was used to evaluate the sensitivity and publication bias of the studies. Publication bias was evaluated by Begg’s and Egger’s tests, and p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Begg’s and Egger’s tests of publication bias were not performed to analyze subgroups with less than 10 articles because of the low sensitivity of qualitative and quantitative tests. All statistical tests were two-sided, and p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

The PRISMA flowchart of literature search is shown in Fig. 1. The initial database search retrieved 9482 articles. No article was found through other sources. After removing 5314 duplicates, 4015 publications for non-surgical procedures were excluded. Among the 153 publications that met our criteria, 3 were excluded as they did not compare LSG and LRYGB, 22 were non-original articles, and 21 had no available original data. The follow-up of 52 studies was less than 3 years, and 27 articles had no outcomes relevant to our bariatric surgery. Therefore, 28 articles were included in analysis [1–7, 10, 11, 14, 15, 17–20, 24–36]. After serious consideration, all articles were of great research value and could provide strong evidence for our meta-analysis. Countries included were very representative and vast, including Chile, China, Finland, France, Greece, India, Italy, Lebanon, Netherlands, Poland, Singapore, Spain, Switzerland, USA, and Venezuela.

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram of study inclusion and exclusion

Study characteristics

In total, the characteristics of the 28 studies are shown in Table 1.The included studies consist of seven RCTs, six prospective observational studies, and 15 retrospective observational studies. Overall, 9038 patients (4597 in the LSG group, 4441 in the LRYGB group) were included. All of them were followed for at least 3 years, and 13 studies of them were followed for 5 years or longer. The results of assessment of quality and risk of bias for all included studies were included in Additional file 1: Table S1.

%EWL

%EWL is an essential metric that measures the effect of weight loss after bariatric surgery. A total of 19 articles reported %EWL after surgery. Among them, 13 articles provided 3-year follow-up data, 9 articles provided 5-year follow-up data, and 3 articles provided both 3-year and 5-year data. At 3-year follow-up, %EWL in the LRYGB group was greater than that in the LSG group (WMD = -4.37, 95%Cl = − 8.10-(− 0.64), p = 0.02, random-effects model). Subgroup analysis performed according to the type of study revealed that the postoperative effect of LRYGB group was better than that of LSG group in RCTs (WMD = -11.96, 95%Cl = − 17.62-(− 6.30), p < 0.001). Moreover, no significant difference in the treatment effect between the two groups was found, in either prospective or retrospective studies (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Forest plots of of %EWL (LSG vs LRYGB). (A) Third year and (B) fifth year

Comparison of the outcome of %EWL in the fifth postoperative year showed that patients who underwent LRYGB had greater %EWL than those who underwent LSG (WMD = -2.20, 95%Cl = − 3.83-(− 0.57), p = 0.008, random-effects model). Subgroup analysis of LSG and LRYGB in 5-year follow-up revealed that the LRYGB group has better outcomes than the LSG group in both retrospective studies (WMD = -2.05, 95% Cl = − 2.60-(− 1.50), p < 0.001) and RCTs (WMD = -6.36, 95% Cl = − 12.51-(− 0.20), p = 0.04) (Fig. 2).

Resolution of obesity-related comorbidities

Many studies investigated the improvement of obesity-related comorbidities during the postoperative period. Some publications discussed comorbidities such as arthritis, obstructive sleep apnea, hyperuricemia, and depression. This meta-analysis detected the effect of remission of only hypertension, T2DM, and dyslipidemia.

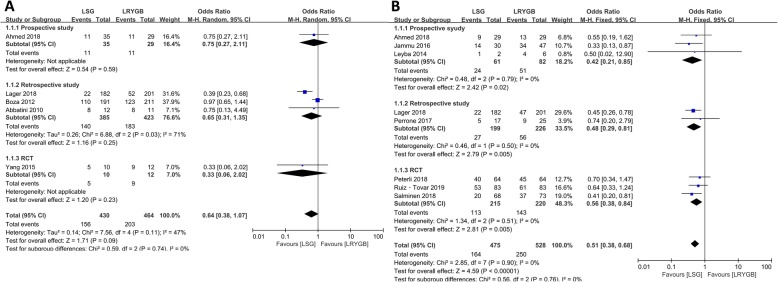

T2DM

Of the 28 articles, 14 mentioned remission rates of T2DM representing 1018 patients (490 in the LSG group, 528 in the LRYGB group). The remission rate of T2DM in the LRYGB group was higher than that in the LSG in 3-years follow-up (OR = 0.68, 95% CI = 0.48–0.95, p = 0.02, fixed-effects model), so was the remission rate in 5-year follow-up (OR = 0.63, 95% CI = 0.41–0.96, p = 0.03, fixed-effects model). Subgroup analysis according to the type of study revealed that the remission rate in LRYGB was higher than that in LSG in prospective studies with 3-year follow-up (OR = 0.46, 95% CI = 0.24–0.89, p = 0.02). In addition, no significant difference was found between retrospective studies and RCTs. At 5-year follow-up, no statistical difference was noted among all prospective studies, retrospective studies, or RCTs. Details are shown in Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Forest plots of remission of T2DM (LSG vs LRYGB). (A) Third year and (B) fifth year

Hypertension

Eleven articles focused on hypertension representing 1456 patients (694 in the LSG group, 762 in the LRYGB group). No statistical difference was observed in hypertension at the 3-year follow-up and all subgroup analyses between LRYGB and LSG. Interestingly, compared with the LSG group, the LRYGB group has higher remission rate of hypertension during the fifth postoperative year (OR = 0.51, 95% CI = 0.38–0.68, p < 0.001, fixed-effects model). In the subgroup analysis, the outcomes of LRYGB were better than those of LSG among all prospective studies, retrospective studies, and RCTs (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Forest plots of remission of hypertension (LSG vs LRYGB). (A) Third year and (B) fifth year

Dyslipidemia

Although no statistical difference in remission of dyslipidemia at 3-year follow-up was found, LRYGB had higher remission rate of dyslipidemia at 5-year follow-up (OR = 0.30, 95% CI = 0.19–0.48, p < 0.001, fixed-effects model). The remission rate of abnormally low-density lipoprotein (LDL) at 5-year follow-up resolved considerably more common in the LRYGB group than in the LSG group (OR = 0.27, 95% CI = 0.11–0.68, p = 0.006, fixed-effects model). Moreover, we did not find significant difference in the treatment effect between the two groups in terms of high-density lipoprotein and triglycerides in the fifth year of follow-up (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Forest plots of remission of dyslipidemia (LSG vs LRYGB). (A) Remission of dyslipidemia in the third year, (B) remission of high triglycerides in the fifth year, (C) remission of low HDL in the fifth year, (D) remission of high LDL in the fifth year, and (E) remission of dyslipidemia in the fifth year

Sensitivity analysis and publication bias

In each group analysis, we excluded each study and the overall effect was consistent. Begg’s and Egger’s test were performed on the results of each group, and the results showed no publication bias (p > 0.05).

Discussion

LSG and LRYGB are the most commonly performed bariatric surgeries in the last decade. They are not only safe and effective for weight loss, but also have a role in alleviating complications. This meta-analysis was based on 27 multi-screened, high-quality highly reviewed articles. The main results of this meta-analysis were as follows: (1) no significant difference was found in %EWL and remission of hypertension and dyslipidemia between the LSG group and the LRYGB group at 3-year follow-up. (2) Five-year follow-up results showed that LRYGB had an advantage over LSG in terms of %EWL, remission of hypertension, dyslipidemia, and abnormally LDL. (3) The remission rate of T2DM was superior in LSG in both 3- and 5-year follow-up.

%EWL

Our mid-term (3-year follow-up) results showed that both groups had good outcomes and that there was no significant difference in %EWL, which might be attributed to a lower initial body mass index (BMI) [37]. Hosam et al. observed that the preoperative BMI had a strong impact on the final outcome of LSG [38]. Interestingly, LRYGB gradually showed its advantages during the 5-year follow-up period, which agreed with the research conclusions of Zhang et al. [6]. As a restrictive procedure, high-calorie and high-sugar foods after LSG could cause rebound weight gain, so patients should strictly follow the postoperative nutritional guidelines. LSG reduces weight by limiting calories, but expanding sleeved stomach caused by dietary failure will lead to weight recovery. Many articles indicated that LRYGB was superior to LSG in weight reduction especially for super-obese patients [3, 6]. Thus, LSG might be converted to LRYGB due to insufficient weight loss or severe reflux esophagitis [5, 27].

Nowadays, the goal of bariatric surgery is not as simple as controlling weight alone. It is equally important to improve complications such as T2DM, dyslipidemia, hypertension, obstructive sleep apnea, liver, and kidney function damage [39]. Bariatric surgery could also be used as potential treatment of metabolic syndrome, and the concept of “metabolic surgery” was born [40].

T2DM

The results of the 3-year and 5-year follow-up showed that the T2DM remission rate of LRYGB was higher than that of LSG. The heterogeneity of the results was very low, and data were highly feasible. Jiménez et al. showed that more than half of patients who underwent LSG bariatric surgery had a T2DM remission after 3 years of follow-up, and this goal was achieved with only 2 years in the LRYGB group. T2DM will recur after a long time, which results in decreased remission rate; therefore, long-term follow-up is more meaningful [25]. Some research results showed that %EWL was a determinant of T2DM remission. To determine the effect of fasting insulin and glucose reduction, the degree of %EWL was more significant than the type of surgery. This may be the reason why LRYGB was more effective than LSG as T2DM treatment [16].

Many studies had shown that hormonal changes also play an important role in weight loss and remission of metabolic disease after surgery. Several theories about hormonal changes were intensively under investigation, but none of them currently stand out as the leading mechanism. According to previous studies, LRYGB and LSG induce similar changes in these hormones expect for ghrelin. Ghrelin is reduced after LSG as large parts of the stomach were resected, whereas ghrelin may increase or remain stable after LRYGB [41, 42]. A recent study showed that LRYGB was characterized by accelerated absorption of glucose and amino acids, whereas protein metabolism after LSG did not differ significantly from controls, suggesting that different mechanisms explain improved glycemic control and weight loss after these surgical procedures [43].

Hypertension

Obesity has become one of the most important causes of hypertension, as 60 to 70% of hypertension in adults can be attributed to obesity [44]. In this study, no statistical difference in midterm hypertension remission rates was found between the two groups, but long-term results showed that LRYGB had an obvious advantage. The results of these studies were similar to our results [2, 10, 15, 20]. The exact mechanism of hypertension and a range of cardiovascular diseases due to obesity have not been confirmed. However, the neuroendocrine system and adipokines were thought to play a leading role. Obesity-related hypertension was also thought to be associated with metabolic syndrome related to glucose intolerance [44, 45]. Previous studies had shown that LRYGB may be the first choice for obese patients with cardiovascular risk [46].

Dyslipidemia

Compared to LSG, LRYGB was a more effective treatment of dyslipidemia [37], but the two groups had similar effects on obesity metabolic disorders [17]. Studies that combined various factors showed that the remission rate of abnormally LDL in LRYGB was higher than that in LSG [27, 32], because LRYGB might have reduced the absorption rate of LDL than did LSG [32]. Other studies have shown that LSG has no significant effect on the reduction of LDL, while LRYGB could cause absorption disorder in individuals; perhaps, this is the reason why LRYGB could improve the overall lipid profile better than LSG [47].

The advantages of LRYGB were as follows: The short-term results of LRYGB might be as effective as those of LSG, but medium- or long-term results could show a clear advantage. LRYGB could ensure a good quality of life and minimum side effects, effectively control metabolic complications including T2DM and hypertension [3, 15], provide better blood glucose control, and lower blood lipid level effect [5].

The advantages of the study were a large population base, detailed subgroup analysis (based on follow-up time divided into 3 years (mid-term) and 5 years (long term), three types of trials, and clear indicators for recovery of complications (included only in remission). In a retrospective review of similar meta-analyses, results of Yang et al.’s meta-analysis were similar to the results of the present study in that LRYGB patients had significantly reduced their weight during the 3- or 5-year follow-up period compared to LSG patients [48]. However, they combined the improvement and remission of complications. Heterogeneity could be introduced because of the different definitions of improvement and remission. This might be the reason why LRYGB had not shown an advantage in treating comorbidities. Huang et al.’s meta-analysis showed that LSG and LRYGB had no significant advantage in short- or long-term blood glucose control, which is contrary to our conclusion, because their patients were followed at 1–2 years, and there are limited studies with 3- or 5-year follow-up periods. In addition, they did not perform subgroup analyses based on the type of trial, which was less convincing than this article [49].

Zhao et al. [50]. included 11 RCTs in their meta-analysis, and the results showed no difference in %EWL and T2DM between the two surgical methods (LSG and LRYGB), which may be attributed to the lack of long-term follow-up data, with only 3 studies providing data of 3 years and 5 years respectively. Sharples [51] included 5 RCTs and concluded demonstrated a significantly greater %EWL in patients undergoing LRYGB compared with LSG. However, there was no significant difference between LRYGB and LSG in rates of resolution or improvement of diabetes. Similarly, HbA1C levels were not significantly different between the two procedures. A meta-analysis involving 33 RCTs showed that LRYGB resulted in greater BMI loss at 1 and 3 years; however, there was insufficient randomized evidence to draw any conclusions regarding weight loss between the 2 procedures at 5 years. No differences between the two procedures were found in remission of type 2 diabetes, despite a trend at every time interval favoring LRYGB, hypertension [52]. However, most of the studies included in this study were short-term follow-up data with high heterogeneity, so the results need careful interpretation.

This study has some limitations. This study included retrospective studies that reduced the overall quality of evidence. We were unable to classify obese people according to the degree of obesity, because it was not explicitly mentioned in the papers. In addition, most of the countries included were Western and were not necessarily suitable for the Asian population. Finally, the criteria for incorporating obese patients were different because varied literature types were included. These deficiencies will affect the scope and accuracy of the findings of this meta-analysis.

Conclusion

In summary in terms of the long-term effects of bariatric surgery, including %EWL and the remission of complications (T2DM, hypertension and dyslipidemia), the effect of LRYGB was better than of LSG.

Additional File

Additional file 1 Table S1 Quality assessment of studies included.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- BMI

Body mass index

- EWL

Percentage of excess weight loss

- LDL

Low-density lipoprotein, 95%CI: 95% confidence intervals

- LRYGB

Laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass

- LSG

Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy

- NOS

Newcastle-Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale

- OR

Odds ratio

- PRISMA

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses, %

- RCT

Randomized controlled trial

- T2DM

Type 2 diabetes mellitus

- WMD

Weighted mean difference

Author’s contributions

Each author contributed significantly to concept and development of the present paper. LG and PC designed this study. LG, XH, SL, DM, and ZS collected the data. LG and XH analyzed the data. SL and DM interpreted the data. ZS, PAK and LG drafted the manuscript. LG and DMN interpreted and revised the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Funding

The authors have no financial support to declare.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Lihu Gu and Xiaojing Huang contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Lihu Gu, Email: gulihuyuazhi@126.com.

Xiaojing Huang, Email: 793711648@qq.com.

Shengnan Li, Email: 1609132951@qq.com.

Danyi Mao, Email: danyimao1@163.com.

Zefeng Shen, Email: 291821586@qq.com.

Parikshit Asutosh Khadaroo, Email: asutoshkhadaro@hotmail.com.

Derry Minyao Ng, Email: derrym.ng@hotmail.com.

Ping Chen, Email: chenpinghwamei@163.com.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1186/s12893-020-00695-x.

References

- 1.Abbatini F, Rizzello M, Casella G, Alessandri G, Capoccia D, Leonetti F, Basso N. Long-term effects of laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy, gastric bypass, and adjustable gastric banding on type 2 diabetes. Surg Endosc. 2010;24:1005–1010. doi: 10.1007/s00464-009-0715-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Du X, Zhang SQ, Zhou HX, Li X, Zhang XJ, Zhou ZG, Cheng Z. Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy versus Roux-en-Y gastric bypass for morbid obesity: a 1:1 matched cohort study in a Chinese population. Oncotarget. 2016;7:76308–76315. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.12536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ignat M, Vix M, Imad I, D'Urso A, Perretta S, Marescaux J, Mutter D. Randomized trial of Roux-en-Y gastric bypass versus sleeve gastrectomy in achieving excess weight loss. Br J Surg. 2017;104:248–256. doi: 10.1002/bjs.10400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dakour Aridi H, Khazen G, Safadi BY. Comparison of outcomes between laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass and sleeve Gastrectomy in a Lebanese bariatric surgical practice. Obes Surg. 2018;28:396–404. doi: 10.1007/s11695-017-2849-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dogan K, Gadiot RP, Aarts EO, Betzel B, van Laarhoven CJ, Biter LU, Mannaerts GH, Aufenacker TJ, Janssen IM, Berends FJ. Effectiveness and safety of sleeve Gastrectomy, gastric bypass, and adjustable gastric banding in morbidly obese patients: a multicenter, retrospective, matched cohort study. Obes Surg. 2015;25:1110–1118. doi: 10.1007/s11695-014-1503-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang Y, Zhao H, Cao Z, Sun X, Zhang C, Cai W, Liu R, Hu S, Qin M. A randomized clinical trial of laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass and sleeve gastrectomy for the treatment of morbid obesity in China: a 5-year outcome. Obes Surg. 2014;24:1617–1624. doi: 10.1007/s11695-014-1258-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vidal P, Ramon JM, Goday A, Benaiges D, Trillo L, Parri A, Gonzalez S, Pera M, Grande L. Laparoscopic gastric bypass versus laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy as a definitive surgical procedure for morbid obesity. Mid-term results Obes Surg. 2013;23:292–299. doi: 10.1007/s11695-012-0828-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li J, Lai D, Wu D. Laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass versus laparoscopic sleeve Gastrectomy to treat morbid obesity-related comorbidities: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Surg. 2016;26:429–442. doi: 10.1007/s11695-015-1996-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lakdawala MA, Bhasker A, Mulchandani D, Goel S, Jain S. Comparison between the results of laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy and laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass in the Indian population: a retrospective 1 year study. Obes Surg. 2010;20:1–6. doi: 10.1007/s11695-009-9981-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Leyba JL, Llopis SN, Aulestia SN. Laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass versus laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy for the treatment of morbid obesity. A prospective study with 5 years of follow-up. Obes Surg. 2014;24:2094–2098. doi: 10.1007/s11695-014-1365-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alexandrou A, Armeni E, Kouskouni E, Tsoka E, Diamantis T, Lambrinoudaki I. Cross-sectional long-term micronutrient deficiencies after sleeve gastrectomy versus Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: a pilot study. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2014;10:262–268. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2013.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Coupaye M, Gorbatchef C, Calabrese D, Sami O, Msika S, Coffin B, Ledoux S. Gastroesophageal reflux after sleeve Gastrectomy: a prospective mechanistic study. Obes Surg. 2018;28:838–845. doi: 10.1007/s11695-017-2942-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kehagias I, Karamanakos SN, Argentou M, Kalfarentzos F. Randomized clinical trial of laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass versus laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy for the management of patients with BMI < 50 kg/m2. Obes Surg. 2011;21:1650–1656. doi: 10.1007/s11695-011-0479-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ruiz-Tovar J, Carbajo MA, Jimenez JM, Castro MJ, Gonzalez G, Ortiz-de-Solorzano J, Zubiaga L. Long-term follow-up after sleeve gastrectomy versus Roux-en-Y gastric bypass versus one-anastomosis gastric bypass: a prospective randomized comparative study of weight loss and remission of comorbidities. Surg Endosc. 2019;33:401–410. doi: 10.1007/s00464-018-6307-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Perrone F, Bianciardi E, Ippoliti S, Nardella J, Fabi F, Gentileschi P. Long-term effects of laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy versus Roux-en-Y gastric bypass for the treatment of morbid obesity: a monocentric prospective study with minimum follow-up of 5 years. Updat Surg. 2017;69:101–107. doi: 10.1007/s13304-017-0426-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pucci A., Tymoszuk U., Cheung W. H., Makaronidis J. M., Scholes S., Tharakan G., Elkalaawy M., Guimaraes M., Nora M., Hashemi M., Jenkinson A., Adamo M., Monteiro M. P., Finer N., Batterham R. L. Type 2 diabetes remission 2 years post Roux-en-Y gastric bypass and sleeve gastrectomy: the role of the weight loss and comparison of DiaRem and DiaBetter scores. Diabetic Medicine. 2017;35(3):360–367. doi: 10.1111/dme.13532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yang J, Wang C, Cao G, Yang W, Yu S, Zhai H, Pan Y. Long-term effects of laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy versus roux-en-Y gastric bypass for the treatment of Chinese type 2 diabetes mellitus patients with body mass index 28-35 kg/m (2) BMC Surg. 2015;15:88. doi: 10.1186/s12893-015-0074-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jammu GS, Sharma R. A 7-year clinical audit of 1107 cases comparing sleeve Gastrectomy, Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, and mini-gastric bypass, to determine an effective and safe bariatric and metabolic procedure. Obes Surg. 2016;26:926–932. doi: 10.1007/s11695-015-1869-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lager Corey J., Esfandiari Nazanene H., Luo Yingying, Subauste Angela R., Kraftson Andrew T., Brown Morton B., Varban Oliver A., Meral Rasimcan, Cassidy Ruth B., Nay Catherine K., Lockwood Amy L., Bellers Darlene, Buda Colleen M., Oral Elif A. Metabolic Parameters, Weight Loss, and Comorbidities 4 Years After Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass and Sleeve Gastrectomy. Obesity Surgery. 2018;28(11):3415–3423. doi: 10.1007/s11695-018-3346-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Salminen P, Helmio M, Ovaska J, Juuti A, Leivonen M, Peromaa-Haavisto P, Hurme S, Soinio M, Nuutila P, Victorzon M. Effect of laparoscopic sleeve Gastrectomy vs laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass on weight loss at 5 years among patients with morbid obesity: the SLEEVEPASS randomized clinical trial. Jama. 2018;319:241–254. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.20313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M, Ghersi D, Liberati A, Petticrew M, Shekelle P, Stewart LA. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst Rev. 2015;4:1. doi: 10.1186/2046-4053-4-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Green S, Higgins JPT, Alderson P, et al. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011]. The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011.

- 23.Stang A. Critical evaluation of the Newcastle-Ottawa scale for the assessment of the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. Eur J Epidemiol. 2010;25:603–605. doi: 10.1007/s10654-010-9491-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Boza C, Gamboa C, Salinas J, Achurra P, Vega A, Perez G. Laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass versus laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy: a case-control study and 3 years of follow-up. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2012;8:243–249. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2011.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jimenez A, Casamitjana R, Flores L, Viaplana J, Corcelles R, Lacy A, Vidal J. Long-term effects of sleeve gastrectomy and Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery on type 2 diabetes mellitus in morbidly obese subjects. Ann Surg. 2012;256:1023–1029. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318262ee6b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Carandina S, Maldonado PS, Tabbara M, Valenti A, Rivkine E, Polliand C, Barrat C. Two-step conversion surgery after failed laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding. Comparison between laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass and laparoscopic gastric sleeve. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2014;10:1085–1091. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2014.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee WJ, Pok EH, Almulaifi A, Tsou JJ, Ser KH, Lee YC. Medium-term results of laparoscopic sleeve Gastrectomy: a matched comparison with gastric bypass. Obes Surg. 2015;25:1431–1438. doi: 10.1007/s11695-015-1582-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gonzalez-Heredia R, Sanchez-Johnsen L, Valbuena VS, Masrur M, Murphey M, Elli E. Surgical management of super-super obese patients: Roux-en-Y gastric bypass versus sleeve gastrectomy. Surg Endosc. 2016;30:2097–2102. doi: 10.1007/s00464-015-4465-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kaseja K, Majewski WD, Kolpiewicz B. A comparison of EFECTIVENESS, and an assessment of the quality of LIFE of patients after laparoscopic sleeve GASTRECTOMY and roux-en-y gastric bypass. Ann Acad Med Stetin. 2014;60:7–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rondelli F, Bugiantella W, Vedovati MC, Mariani E, Balzarotti Canger RC, Federici S, Guerra A, Boni M. Laparoscopic gastric bypass versus laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy: a retrospective multicenter comparison between early and long-term post-operative outcomes. Int J Surg. 2017;37:36–41. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2016.11.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Peterli R, Wolnerhanssen BK, Peters T, Vetter D, Kroll D, Borbely Y, Schultes B, Beglinger C, Drewe J, Schiesser M, Nett P, Bueter M. Effect of laparoscopic sleeve Gastrectomy vs laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass on weight loss in patients with morbid obesity: the SM-BOSS randomized clinical trial. Jama. 2018;319:255–265. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.20897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Climent E, Benaiges D, Flores-Le Roux JA, Ramon JM, Pedro-Botet J, Goday A. Changes in the lipid profile 5 years after bariatric surgery: laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass versus laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2018;14:1099–1105. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2018.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sepulveda M, Alamo M, Preiss Y, Valderas JP. Metabolic surgery comparing sleeve Gastrectomy with Jejunal bypass and Roux-en-Y gastric bypass in type 2 diabetic patients after 3 years. Obes Surg. 2018;28:3466–3473. doi: 10.1007/s11695-018-3402-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ahmed B, King WC, Gourash W, Belle SH, Hinerman A, Pomp A, Dakin G, Courcoulas AP. Long-term weight change and health outcomes for sleeve gastrectomy (SG) and matched Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) participants in the longitudinal assessment of bariatric surgery (LABS) study. Surgery. 2018;164:774–783. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2018.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kim G, Tan CS, Tan KW, Lim SPY, So JBY, Shabbir A. Sleeve Gastrectomy and Roux-en-Y gastric bypass Lead to comparable changes in body composition in a multiethnic Asian population. J Gastrointest Surg. 2019;23:445–450. doi: 10.1007/s11605-018-3920-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schauer PR, Bhatt DL, Kirwan JP, Wolski K, Aminian A, Brethauer SA, Navaneethan SD, Singh RP, Pothier CE, Nissen SE, Kashyap SR. Bariatric surgery versus intensive medical therapy for diabetes - 5-year outcomes. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:641–651. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1600869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.El Chaar M, Hammoud N, Ezeji G, Claros L, Miletics M, Stoltzfus J. Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy versus laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: a single center experience with 2 years follow-up. Obes Surg. 2015;25:254–262. doi: 10.1007/s11695-014-1388-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Elbanna H, Ghnnam W, Negm A, Youssef T, Emile S, El Metwally T, Elalfy K. Impact of preoperative body mass index on the final outcome after laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy for morbid obesity. Ulus Cerrahi Derg. 2016;32:238–243. doi: 10.5152/UCD.2016.3275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhang N, Maffei A, Cerabona T, Pahuja A, Omana J, Kaul A. Reduction in obesity-related comorbidities: is gastric bypass better than sleeve gastrectomy? Surg Endosc. 2013;27:1273–1280. doi: 10.1007/s00464-012-2595-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vix M, Diana M, Liu KH, D'Urso A, Mutter D, Wu HS, Marescaux J. Evolution of glycolipid profile after sleeve gastrectomy vs. Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: results of a prospective randomized clinical trial. Obes Surg. 2013;23:613–621. doi: 10.1007/s11695-012-0827-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Batterham RL, Cummings DE. Mechanisms of diabetes improvement following bariatric/metabolic surgery. Diabetes Care. 2016;39:893–901. doi: 10.2337/dc16-0145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ryan KK, Tremaroli V, Clemmensen C, Kovatcheva-Datchary P, Myronovych A, Karns R, Wilson-Perez HE, Sandoval DA, Kohli R, Backhed F, Seeley RJ. FXR is a molecular target for the effects of vertical sleeve gastrectomy. Nature. 2014;509:183–188. doi: 10.1038/nature13135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Svane MS, Bojsen-Moller KN, Martinussen C, Dirksen C, Madsen JL, Reitelseder S, Holm L, Rehfeld JF, Kristiansen VB, van Hall G, Holst JJ, Madsbad S. Postprandial Nutrient Handling and Gastrointestinal Hormone Secretion After Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass vs Sleeve Gastrectomy. Gastroenterology. 2019;156:1627–1641.e1621. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2019.01.262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kotchen TA. Obesity-related hypertension: epidemiology, pathophysiology, and clinical management. Am J Hypertens. 2010;23:1170–1178. doi: 10.1038/ajh.2010.172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Narkiewicz K. Obesity and hypertension--the issue is more complex than we thought. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2006;21:264–267. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfi290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Peterli R, Wolnerhanssen BK, Vetter D, Nett P, Gass M, Borbely Y, Peters T, Schiesser M, Schultes B, Beglinger C, Drewe J, Bueter M. Laparoscopic sleeve Gastrectomy versus Roux-Y-gastric bypass for morbid Obesity-3-year outcomes of the prospective randomized Swiss multicenter bypass or sleeve study (SM-BOSS) Ann Surg. 2017;265:466–473. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Benaiges D, Flores-Le-Roux JA, Pedro-Botet J, Ramon JM, Parri A, Villatoro M, Carrera MJ, Pera M, Sagarra E, Grande L, Goday A. Impact of restrictive (sleeve gastrectomy) vs hybrid bariatric surgery (Roux-en-Y gastric bypass) on lipid profile. Obes Surg. 2012;22:1268–1275. doi: 10.1007/s11695-012-0662-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yang P, Chen B, Xiang S, Lin XF, Luo F, Li W. Long-term outcomes of laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy versus Roux-en-Y gastric bypass for morbid obesity: results from a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2019;15:546–555. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2019.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Huang X, Liu T, Zhong M, Cheng Y, Hu S, Liu S. Predictors of glycemic control after sleeve gastrectomy versus Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: a meta-analysis, meta-regression, and systematic review. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2018;14:1822–1831. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2018.08.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhao H, Jiao L. Comparative analysis for the effect of Roux-en-Y gastric bypass vs sleeve gastrectomy in patients with morbid obesity: evidence from 11 randomized clinical trials (meta-analysis) Int J Surg. 2019;72:216–223. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2019.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sharples Alistair J., Mahawar Kamal. Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomised Controlled Trials Comparing Long-Term Outcomes of Roux-En-Y Gastric Bypass and Sleeve Gastrectomy. Obesity Surgery. 2019;30(2):664–672. doi: 10.1007/s11695-019-04235-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lee Y, Doumouras AG, Yu J, Aditya I, Gmora S, Anvari M, Hong D. Laparoscopic sleeve Gastrectomy versus laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: a systematic review and meta-analysis of weight loss, comorbidities, and biochemical outcomes from randomized controlled trials. Ann Surg. 2019;23:1–15. [DOI] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1 Table S1 Quality assessment of studies included.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.