Abstract

Background:

Extracts of Piper betel are used for the treatment of various ailments since ages due to its essential properties like antioxidant, anticancer, anti-allergic etc. In the present study antioxidant activity for Piper betel leaf extract and Eugenol was assessed. Eugenol was taken as marker compound.

Methods:

Nitric oxide, Hydroxyl radical and Reducing power assay methods were carried out for assessment of antioxidant activity of Piper betel.

Results:

The antioxidant activity for Nitric oxide, Hydroxyl radical and Reducing power assay at 1000 to 62.5μg/ml was performed. The antioxidant activity of Piper betel leaf extract exhibited the IC50 value for Nitric oxide and Hydroxyl radical >1000 whereas Eugenol exhibited the IC50 value 114.34± 0.46 and 306.44 ± 5.28 respectively, for reducing power assay (RPA) Piper betel leaf extract and Eugenol revealed the RPA value ranging from 0.44-0.08 and 0.53-0.12.

Conclusion:

The benefits of Piper betel have been mentioned in our ancient texts. Keeping in view the emergence of various diseases and the benefits of Piper betei, there is need that every effort should be made to revive this treasure of nature into our daily supplement.

Keywords: Antioxidant activity, Eugenol, Piper betel

Introduction

Piper betel is a potential nontoxic natural antioxidant. The intake and chewing of betel leaves have an effect on the moving parts of salivary gland and induce salivation which is the first step of digestion. Leaf extracts and purified compounds of P. betel have antiseptic, antibacterial, antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, anti-cancer, and immunomodulatory efficacy. It contains various phytochemicals, such as alkaloids, flavonoids, steroids, saponins, and tannins, and it also contains sugar, diastases, and essential oil. Ayurveda also states Betel Leaf (BL) and its components act as heartbeat regulators in relaxing the blood vessels thereby reducing hypertension.[1]

As it is reported that seasonal variation is seen in the constituents of herbal plants, it is of foremost importance to analyze/check the plant constituents before carrying out any study.[2]

Thus, the following study was undertaken to evaluate the antioxidant potential of P. betel.

A molecule with one or more unpaired electron in its outer shell is called a free radical.[3,4,5,6,7]

The theory of oxygen-free radicals has been known about 50 years ago.[6] However, only within the last 2 decades has there been an explosive discovery of their roles in the development of diseases and also of the health protective effects of antioxidants.

When cells use oxygen to generate energy, free radicals are created as a consequence of adenosine triphosphate production by the mitochondria. These by-products are generally reactive oxygen species (ROS) as well as reactive nitrogen species (RNS) that result from the cellular redox process. These species play a dual role as both toxic and beneficial compounds. The delicate balance between their two antagonistic effects is clearly an important aspect of life.

At low or moderate levels, ROS and RNS exert beneficial effects on cellular responses and immune function. At high concentrations, they generate oxidative stress, a deleterious process that can damage all cell structures.[8]

Antioxidants, as class of compounds able to counteract oxidative stress and mitigate its effects on individuals' health, gained enormous attention from the biomedical research community, because these compounds not only showed a good degree of efficacy in terms of disease prevention and/or treatment but also because of the general perception that they are free from important side effects.[9]

Medicinal plants have been known for millennia and are highly esteemed all over the world as a rich source of therapeutic agents for the prevention of diseases and ailments.[10] Large number of plants are constantly being screened for their chemical and pharmacological properties.[11] By the application of modern techniques of isolation and pharmacological evaluation, many new plant drugs find their way to medicine as purified substances.[12]

Scientifically, studies have reported the biological benefits of P. betel to include inhibition of platelet aggregation,[13] antidiabetic activities,[14] immunomodulatory properties,[15] and antiallergic activities.[16] Some of these observed biological activities were attributed to the high antioxidant activities of this plant.[17,18]

Eugenol, one of the principal constituent of P. betel leaf, has also been shown to possess anti-inflammatory effects in various animal models of studies with various inflamogens.[19,20]

Materials and Methods

Collection of plant materials

P. betel leaves were collected from local market. The leaves were identified and authenticated at Department of Horticulture, College of Agriculture, Professor Jayashankar Telangana State Agricultural University, Rajendranagar, Hyderabad and the voucher specimen was deposited. Ethical committee approval is already obtained on 03/10/2016.

Chemicals

All chemicals and reagents were of analytical grade, purchased from Merck.

Method

Outline of the method The antioxidant activity for NO, hydroxyl radical, and reducing power assay (RPA) at 1000 to 62.5 μg/ml was performed.

Determination of antioxidant activity for NO radical

Preparation of test substance In 1 ml of dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), 21 mg of P. betel leaf extract was dissolved to obtain the concentration of 1000 μg/ml conc. Further solution was serially diluted to 1000---62.5 μg/ml to get lower concentration.

Preparation of standard In 1 ml of DMSO, 21 mg of rutin was dissolved to obtain solutions of 1000 μg/ml which is serially diluted to get lower conc. of 62.5, 125, 250, 500, and 1000 μg/ml. Preparation of sodium nitroprusside In 100 ml of distilled water, 0.29 g of sodium nitroprusside was dissolved.

Preparation of 0.1% naphthyl ethylene diaminedihydrochloride (NEDD) In 100 ml of distilled water, 0.1 g of NEDD was dissolved. Preparation of sulphanilic acid In 100 ml of 5% orthophosphoric acid, 1 g of sulphanilic acid was dissolved.

Antioxidant activity for NO radical

In the test 0.1 ml of P. betel leaf extract and eugenol was taken separately and to this 0.4 ml of 10 mM sodium nitroprusside, 0.1 ml of Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS) was added. For control and control blank 0.1 ml of DMSO was taken in the place of test. For test blank and control blank 0.4 ml of distilled water was added in place of sodium nitroprusside. The reaction mixture was incubated at 250 C for 150 min. After incubation 50 μl of reaction mixture was transferred to microtiter plate and to this reaction mixture 0.1 ml of sulphanilic acid was added and kept for 5 min. Then 0.1 ml of NEDD was added to all and allows it to stand for 30 min in diffused light. A pink colored chromophore was formed according to the concentration of the test samples. Same procedure was repeated for standard by replacing the test sample with standard. Test and control were performed in triplicate and test blank and control blank were conducted in singlet. An antioxidant activity was determined by measuring the pink colored chromophore released from NEDD at 540 nm in Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) reader.

Determination of antioxidant activity for hydroxyl radical

Preparation of test substance In 1 ml of DMSO, 20 mg of P. betel leaf extract and eugenol was dissolved completely to obtain the concentration of 1000 μg/ml. Further solution was serially diluted to 1000---62.5 g/ml to get lower concentration.

Preparation of standard In 1 ml of DMSO, 20 mg of rutin was dissolved to obtain solutions of 1000 μg/ml which is serially diluted to get lower conc. of 62.5, 125, 250, 500, and 1000 μg/ml.

Preparation of iron- Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) In 100 ml of distilled water 0.13% of ferrous ammonium sulphate and 0.26% of (EDTA) ethylene diamine tetra acetic acid was dissolved.

Preparation of 0.018% EDTA In 100 ml of distilled water, 0.018 g of EDTA was dissolved. Preparation Of 0.85% DMSO In 100 ml of phosphate buffer pH 7.4, 0.85 ml of DMSO was dissolved.

Preparation of 0.22% ascorbic acid

In 100 ml of distilled water, 0.22 g of ascorbic acid was added.

Preparation of 17.5% trichloroacetic acid (TCA) In 100 ml of distilled water, 17.5 ml of concentrated (TCA) TCA was added and diluted.

Preparation of Nash Reagent Weigh accurately about 17.5 g of ammonium acetate and dissolve in distilled water. To the above solution 0.3 ml of glacial acetic acid and 0.2 ml of acetyl acetone was added and the final volume was made up to 100 ml with distilled water.

Antioxidant activity for hydroxyl radical In test and test blank 0.1 ml of P. betel leaf extract and eugenol was taken separately and to the control and control blank 0.1 ml of DMSO was taken in the place of test. For test and control 0.1 ml of iron-EDTA, 0.05 ml of EDTA and 0.05 ml of 0.22% of ascorbic acid was added. To the test blank and control blank in place of all reagents distilled water was added. To all the Eppendorf tube 0.1 ml of 0.85% DMSO was added. The reaction mixture was incubated at 800--900°C for 15 min. After incubation, 0.3 ml of Nash reagent was added to test and control. In order to stop the reaction 0.1 ml of 17.5% TCA was added to the test and control. To the test blank and control blank 0.4 ml of distilled water was added and kept at room temperature for 15 min. 100 μl of reaction mixture was transferred to microtiter plate and the reaction mixture was turned to yellow color according to the concentration of the test samples. Same procedure was repeated for standard by replacing test sample with standard. Test and control were performed in triplicate and test blank and control blank were conducted in singlet. An antioxidant activity was determined by measuring at 405 nm in ELISA reader.

Determination of antioxidant activity for ferric ion RPA

Preparation of test substance In 2 ml of DMSO, 20 mg of P. betel leaf extract and eugenol was dissolved completely to obtain the concentration of 1000 μg/ml. Further solution was serially diluted to 1000---62.5 g/ml to get the lower concentration.

Preparation of standard In 2 ml of DMSO, 20 mg of ascorbic acid was dissolved to obtain solutions of 1000 μg/ml which is serially diluted to get lower conc. of 62.5, 125, 250, 500, and 1000 g/ml.

Preparation of 1% potassium ferric cyanide In 100 ml of distilled water, 1 g of potassium ferric cyanide was dissolved.

Preparation of 10% TCA In 10 ml of distilled water, 1 ml of concentrated TCA was added and diluted.

Preparation of 0.1% ferric chloride In 100 ml of distilled water, 0.1 g of ferric chloride was dissolved.

Antioxidant activity for ferric ion RPA

In test 0.5 ml of P. betel leaf extract and eugenol was taken separately and to this add 2.5 ml of PBS and 2.5 ml of potassium ferric cyanide was added. For control and control blank 0.5 ml of DMSO was added in the place of test. For test blank and control blank 2.5 ml of distilled water was added in place of potassium ferric cyanide. The reaction mixture was incubated at 500°C for 30 min. After incubation 2.5 ml of 10% TCA was added to the test and control and to the test blank and control blank 2.5 ml of distilled water was taken in place of TCA. The reaction mixture was centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 10 min. The 5 ml of supernatant was mixed with equal volume of distilled water. Then, 1 ml of 0.1% FeCl3 was added to the test and control, in place of FeCl3 distilled water was added to the test blank and control blank. The reaction mixture was incubated at room temperature for 10 min. After incubation 100 μl of reaction mixture was transferred to microtiter plate. Same procedure was repeated for standard by replacing test sample with standard. Test and control were performed in triplicate and test blank and control blank were conducted in singlet. Higher the absorbance represents the stronger the reducing power. An antioxidant activity was determined by measuring at 700 nm in ELISA reader.

Results and Discussion

Leaves of P. betel L. (Family, Piperaceae) are commonly used as a masticator in Asia and as a traditional medicine in different countries, such as India, Malaysia, Indonesia, Philippines, Thailand, China, and many other western countries. Its leaf extract has been reported to stimulate pancreatic lipase activity and to inhibit radiation-induced lipid peroxidation. The extract also increases the activities of antioxidants. Its hepatoprotective effect is well understood. In fact, the P. betel phenolics were found to protect photosensitization-mediated lipid peroxidation in rat liver and to enhance antioxidant activities. Indomethacin-induced gastric ulceration was cured by beetle leaf phenolics. Further, its methanolic leaf extract was found to exhibit immunomodulatory activity.[21]

Antioxidants are compounds capable of inhibiting the oxidation processes which occur under the influence of atmospheric oxygen or reactive oxygen species. They are used for the stabilization of polymeric products, of petrochemicals, foodstuffs, cosmetics, and pharmaceuticals. Antioxidants are involved in the defense mechanism of the organism against the pathologies associated with the attack of free radicals. NO is generated from amino acid L-arginine by the enzymes in the vascular endothelial cells, certain neuronal cells, and phagocytes. Low concentrations of NO, are sufficient in most cases to affect the physiological functions of the radical. NO is a diffusible-free radical that plays many roles as an effectors molecule in diverse biological systems including neuronal messenger, vasodilatation, and antimicrobial and antitumor activities. Chronic exposure to NO radical is associated with various carcinomas and inflammatory conditions including juvenile diabetes, multiple sclerosis, arthritis, and ulcerative colitis.[22]

In this study, the antioxidant activity of test substances was evaluated by NO, hydroxyl radical, and RPA.

Methanolic extract of P. betel leaf was tested for antioxidant property by analyzing various in vitro antioxidant models, NO assay, hydroxyl radical test assay, and RPA.

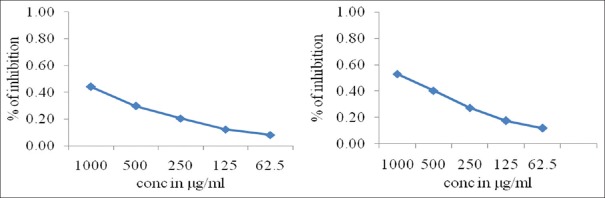

In NO assay, the P. betel leaf extract showed scavenging potential IC50 of >1000 indicating less scavenging activity compared to eugenol, whereas IC50 of that of eugenol was 114.34 ± 0.46 [Table 1], Graphical representation [Figure 1].

Table 1.

The antioxidant activity of test substances for nitric oxide radical

| Test Substance | Conc. µg/ml | IC50 (µg/ml) |

|---|---|---|

| Piper betel leaf extract | 1000 | >1000 |

| 500 | ||

| 250 | ||

| 125 | ||

| 62.5 | ||

| Eugenol | 1000 | 114.34±0.46 |

| 500 | ||

| 250 | ||

| 125 | ||

| 62.5 |

Figure 1.

Graphical representation of nitric oxide antioxidant activity of eugenol

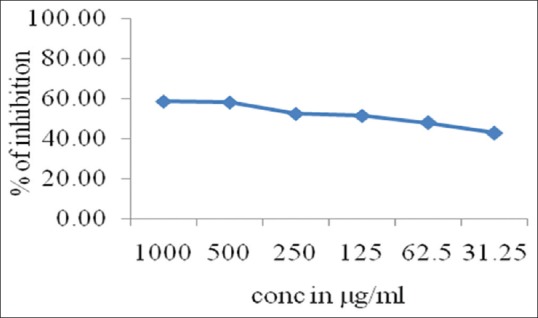

In hydroxyl radical test assay, the P. betel leaf extract showed scavenging potential IC50 of >1000 indicating less scavenging activity compared to eugenol, whereas IC50 of that of eugenol was 306.44 ± 5.28 Table 2, Graphical representation [Figure 2].

Table 2.

The antioxidant activity of test substances for hydroxyl radical

| Test substance | Conc. µg/ml | IC50 (µg/ml) |

|---|---|---|

| Piper betel leaf extract | 1000 | >1000 |

| 500 | ||

| 250 | ||

| 125 | ||

| 62.5 | ||

| Eugenol | 1000 | 306.44±5.28 |

| 500 | ||

| 250 | ||

| 125 | ||

| 62.5 |

Figure 2.

Graphical representation of hydroxyl radical antioxidant activity of eugenol

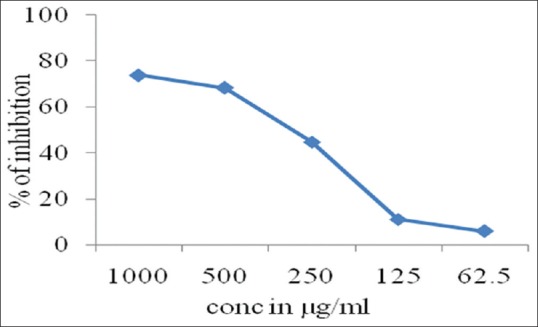

The antioxidant activity of P. betel leaf extract test substances for RPA showed dose-dependent increase in absorbance, showing good antioxidant activity compared to eugenol [Table 3], Graphical representation [Figure 3].

Table 3.

The antioxidant activity of test substances for reducing power assay

| Test substance | Conc. µg/ml | IC50 (µg/ml) |

|---|---|---|

| Piper betel leaf extract | 1000 | 0.44±0.0139 |

| 500 | 0.30±0.0061 | |

| 250 | 0.20±0.0284 | |

| 125 | 0.12±0.0015 | |

| 62.5 | 0.08±0.0006 | |

| Eugenol | 1000 | 0.53±0.0127 |

| 500 | 0.40±0.0106 | |

| 250 | 0.27±0.0040 | |

| 125 | 0.17±0.0017 | |

| 62.5 | 0.12±0.0076 |

Figure 3.

Graphical representation of RPA antioxidant activity of Piper betel leaf extract and eugenol

Conclusion

Antioxidant activity of test substances was evaluated by the standard methods. The P. betel leaf extract showed less antioxidant activity in NO and hydroxyl radical assays compared to the eugenol, whereas in RPA, P. betel leaf extract, showed good antioxidant activity. Eugenol showed good antioxidant activity in NO, hydroxyl radical and RPAs.

The benefits of P. betel have been mentioned in our ancient text. Keeping in view the emergence of various diseases, there is need that every effort should be made to revive this treasure of nature into our daily supplement.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Ekambaram P, Balan C. Efficacy of salivary and diastase extracts of Piper betle in modulating the cellular stress in placental trophoblast during preeclampsia. Pharmacognosy Res. 2019;11:25–30. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Soni U, Brar S, Gauttam VK. Effect of seasonal variation on secondary metabolites of medicinal plants. Int J Pharm Sci Res. 2015;6:3654–62. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Halliwell B, Gutteridge JMC. Free Radicals in Biology and Medicine. 4th ed. Oxford, UK: Clarendon Press; 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bahorun T, Soobrattee MA, Luximon-Ramma V, Aruoma OI. Free radicals and antioxidants in cardiovascular health and disease. Internet J Med Update. 2006;1:1–17. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Valko M, Izakovic M, Mazur M, Rhodes CJ, Telser J. Role of oxygen radicals in DNA damage and cancer incidence. Mol Cell Biochem. 2004;266:37–56. doi: 10.1023/b:mcbi.0000049134.69131.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Valko M, Leibfritz D, Moncol J, Cronin MT, Mazur M, Telser J. Free radicals and antioxidants in normal physiological functions and human disease. Review. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2007;39:44–84. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2006.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Droge W. Free radicals in the physiological control of cell function.Review. Physiol Rev. 2002;82:47–95. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00018.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pham-Huy LA, He H, Pham-Huy C. Free radicals, antioxidants in disease and health. Int J Biomed Sci. 2008;4:89–96. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pizzino G, Irrera N, Cucinotta M, Pallio G, Mannino F, Arcoraci V, et al. Oxidative stress: Harms and benefits for human health. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2017;2017:8416763. doi: 10.1155/2017/8416763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Halliwell B. Drug antioxidant effects? A basis for drug selection. Drugs. 1991;42:569–605. doi: 10.2165/00003495-199142040-00003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kaur C, Kapoor HC. Antioxidant activity and phenolic content of some Asianvegetables. Int J Food Sci Technol. 2002;37:153–61. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hertog MGL, Sweetnam PM, Fehily AM, Elwood PC, Kromhout D. Antioxidant flavonols and ischemic heart disease in a welsh population of men: The caerphilly study. Am J Clin Nutr. 1997;65:1489–94. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/65.5.1489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jeng JH, Chen SY, Liao CH, Tung YY, Lin BR, Hahn LJ, et al. Modulation of platelet aggregation by areca nut and betel. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(02)00749-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Arambewela LSR, Arawwawala LDAM, Ratnasooriya WD. Antidiabetic activities of aqueous and ethanolic extracts of Piper betle leaves in rats. J Ethnopharmacol. 2005;102:239–45. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2005.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Singh M, Shakya S, Soni VK, Dangi A, Kumar N, Bhattacharya SM. The n-hexane and chloroform fractions of Piper betle L. trigger different arms of immune responses in BALB/c mice and exhibit antifilarial activity against human lymphatic filarid Brugia malayi. Int Immunopharmacol. 2009;9:716–28. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2009.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wirotesangthong M, Inagaki N, Tanaka H, Thanakijcharoenpath W, Nagai H. Inhibitory effects of Piper betle on production of allergic mediators by bone marrow-derived mast cells and lung epithelial cells. Int Immunopharmacol. 2008;8:453–7. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2007.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dasgupta N, De B. Antioxidant activity of Piper betle L. leaf extract in vitro. Food Chem. 2004;88:219–24. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Majumdar B, Chaudhuri S, Ray A, Bandyopadhyay S. Potent antiulcerogenic activity of ethanol extract of leaf of Piper betle Linn. by antioxidative mechanism. Indian J Clin Biochem. 2002;17:49–57. doi: 10.1007/BF02867942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dohi T, Terada H, Anamura S, Okamoto H, Tsujimoto A. The anti-inflammatory effects of phenolic dental medicaments as determined by mouse ear edema assay. Jpn J Pharmacol. 1989;49:535–9. doi: 10.1254/jjp.49.535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee YY, Hung SL, Pai SF, Lee YH, Yang SF. Eugenol suppressed the expression of lipopolysaccharide-induced proinflammatory mediators in human macrophages. J Endod. 2007;33:698–702. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2007.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Panda S, Sharma R, Kar A. Antithyroidic and hepatoprotective properties of high-resolution liquid chromatography–Mass spectroscopy-standardized Piper betle leaf extract in rats and analysis of its main bioactive constituents. Pharmacognosy Mag. 2018;14:658–64. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Garrat DC. The Quantitative Analysis of Drugs. 3rd ed. Japan: Chapman and Hall Ltd; 1964. pp. 456–8. [Google Scholar]