Abstract

Introduction and Context:

Sexual health in schools is neglected in most developing countries,[1] however, it is emerging as a major need of the hour. This article captures the author's experience as a family physician in a boarding school setting in India highlighting the need and possible solutions pertaining to sexual health in the school community.

Setting:

An international boarding school in India with approximately 600 students, 500 teachers, and administrators who lived on the school campus and 500 support staff who lived off-campus.

Materials and Methods:

Three events prodded the author to explore perceptions and needs pertaining to sexual health in the school community. Being a difficult area of inquiry, this was done as informal qualitative research by dialoguing with six groups of people in the school community: School counselors, parents, student supervisors such as teachers, advisors and dorm parents, school administrators, support staff, and the students and the responses were collated.

Observations:

A mere 17.9% of grade 5 to 12 students, of age-groups 10 to 19 never had a conversation with their parents about sexuality. Students were largely ignorant or misinformed on most sexuality-related issues but engaged well when offered anonymity or safe space. Though all stakeholders in the school agreed that students needed an age-appropriate, gender and culture-sensitive, scientific and comprehensive sex education, parental responses were mixed.

Conclusion:

The author's journey as a family physician in a school setting has prompted exploration of a wholistic model for the provision of comprehensive sexual health in schools and the emerging role of a family physician in schools.

Keywords: Family physician, primary care physician, school health, school health education, school physician, sex education, sexual health

Introduction and Context

Sexual health is a neglected area in developing countries,[1] more so in schools, and India is no exception. Obviously, the focus is on so many other persistent health issues that developing countries face. However, the fact is, sexual health in school students is emerging as a major area of need in these countries. This article captures the author's experience as a family physician in a boarding school setting in India highlighting the need and possible solutions pertaining to sexual health in the school community.

The beginning of a journey

As a family physician, the author has experience working with children and adolescents for more than 13 years, but the close exposure started in February 2017, when on a sabbatical, the author joined as a school physician in an international boarding school in north India with 65% students from India and 35% students from other countries. The school community comprised of approximately 600 students (mostly boarders), 500 teachers, and administrators who lived on the school campus and 500 support staff who lived off-campus. The author's initial weeks in the school was spent with various stakeholders, doing a subjective needs assessment of health issues in the school, and sexual health emerged as one of the top five needs.

The series of events

And the first three of the following series of events, pictorially depicted in Figure 1, sensitized the author to the sexual health needs and perceptions in a school community:

Figure 1.

Series of Events and Summary of the author's Journey in Exploring Sexual Health Perceptions and Needs in a Boarding School Community

Open space on sexuality: When the author joined the school community as the school physician in February 2017, one of the sessions in the 4-day staff retreat was on “students and sexuality” facilitated by one of the learning support teachers and he presented the common questions students were asking about sexuality. The author was intrigued by the variety of questions the students had asked and the appalling ignorance and misconceptions that resonated in them.

Sexuality week: During the study period, March 20th to 24th, 2017 was planned to be observed as the “sexuality week”. A variety of programs were organized, and sexual health lectures were given, and teachers were encouraged to initiate discussions on this subject in their respective classes. The author was thrilled because she has seen this as a lacuna in most schools in India, both rural and urban. When the author worked in rural parts of India as a family physician, she has seen the consequences of this lacuna with adolescents coming with anything from teenage pregnancy to STIs (sexually transmitted infections). Moreover, the scenario was no different in the urban areas too. During this “sexuality week”, the author had the school clinic open for 2 h in the evenings specifically for the students to come and discuss issues related to sexuality and many students came to talk about a wide variety of topics such as homosexuality, pregnancy, contraception, sexual abuse, and so on.

Sexuality panel discussion: The author was part of a panel discussion that was arranged for students of grades 9 to 12. The questions that came up, anonymous as well as face-to-face, highlighted the misconceptions among students on various sexuality-related issues.

These three events had been tried in this school for the first time and the author's observations are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Positives and Negatives of the Three Sexual Health Related Events: The author’s Observations

| Positives | |

|---|---|

| It was apparent from the “Open Space’” program that students were indeed asking questions related to sexual health | |

| The latter two events gave an opportunity for the students to broach this subject with trusted adults | |

| The possibility to ask anonymous questions gave them an opportunity to express freely | |

| The students were more willing to talk about this one-on-one during the protected time in the school clinic | |

| The embarrassment of talking about the topic grew less and less over that week | |

| The author drafted a leaflet called “Managing your Sexuality wisely”, trying to answer some of the anonymous questions asked by the students, in a conversational and student-friendly style. | |

| The sexuality panel discussion gave them a forum to express their doubts and views regarding sexuality | |

| Negatives | |

| The students seemed to be asking sexuality-related questions only to the teacher who ran the “Open Space” and maybe a handful of others but were in general not broaching the topics with other teachers for which the rapport they shared with them and the teachers’ willingness to talk about such matters seemed to be major factors. | |

| Responses to questions from various adults were unstandardized and ambiguous | |

| There were too many points of view shared which the author felt were confusing for the students. | |

| A lot of subjective views were shared. The scientific basis of many of the issues related to sexuality was not considered. | |

| This is a school with a great deal of diversity. There was a lack of sensitivity to cultural, family, and religious background of the students. | |

| The students did not have a pre-existing good foundation for a healthy understanding of sexuality. There was no graded exposure to students over the years and suddenly everything was let loose for a week which did not go well. | |

| Most student questions on various aspects of sexual health exposed ignorance and misinformation | |

Materials and Methods

The above mentioned three events prodded the author to do some more exploring sexual health perceptions and needs which she knew was a hard area, however, she felt a moral responsibility to do so. Hence, this was carried out as informal qualitative research, after obtaining ethics committee approval on 5th Feb 2018, by informally dialoguing with six groups of people in the school community: school counselors, parents, students, supervisors (teachers, advisors, and dorm parents), school administrators, support staff and most importantly the students and the responses collated.

Observations

Perceptions of school counselors

The school had four school counselors. The author had both formal and informal discussions with them, and their perceptions are as follows:

Students do come to school counselors with questions related to sexual health, often linked with relationship issues. There is a need for more focused counseling services for sexuality-related issues.

Students need a graded exposure to sexuality-related issues in an age-appropriate and gender-sensitive manner. This needs to include the scientific basis of issues related to sexuality, natural outcomes of sexuality-related choices and should be sensitive to culture, religion, and background. A curriculum needs to be developed for this type of sex education

Rather than discussing sex-related issues with responsible adults, students resort to peers or unreliable sites for information and this often leads to unhealthy sexual choices and consequences that need to be addressed.

Perceptions of parents

The author talked informally with parents about starting sex education in school and asked their perspectives. As this is a boarding school, parents come mostly just twice a year. The author informally interviewed 35 parents and encountered varied emotions and responses; the summary of their responses is captured in Table 2

Table 2.

Summary of Parental Response to Sexual Health Education in School

| Emotion | Response | Numbers |

|---|---|---|

Bewildered Bewildered |

What! How can you think of exposing our children to things that they do not even know about!! | 6 |

Angry Angry |

It is a bad idea…look at the West… how has sex education helped? It has only ruined their society… | 2 |

Denial Denial |

My child is very innocent! I don’t think they see or discuss such things…we are from a very conservative background (they honestly have no clue what their child talks here in school) | 7 |

Equivocal Equivocal |

Well, not sure if it is good or bad for our kids | 5 |

Happy Happy |

Wow! That is a great idea! Please go ahead! | 10 |

Thrilled Thrilled |

Yes, that’s wonderful!! We are with you!!! One parent even started listing various topics to be included in this | 5 |

Perceptions of student supervisors (teachers, advisors, and dorm parents)

The author had multiple informal discussions with 41 teachers (8 from early years, 15 from middle years, and 18 from upper years) and 12 dorm parents (6 from middle years and 6 from upper years)

All of them felt that a graded curriculum for promoting healthy sexuality can be very helpful to the students.

Watching pornography (despite many sites being firewalled by the school), sexual experimentations, relationship breakup issues seem to be predominant issues expressed by dorm parents.

Some had apprehensions as to how far one should go with this

Others expressed that they feared that there may be repercussions from the parental side.

Perceptions of school administration

The school administration had already perceived the need due to the various sexuality-related disciplinary issues handled in the past.

A task group was formed to streamline the school sexuality policy.

A few meetings were held to look at the anonymous questions collected from students on sexuality and the school's stand on various issues was discussed.

The decision was made to start a wholistic PSHE (personal, social, and health education) curriculum for the students, which includes sexual health as well.

Perceptions of students

A team consisting of the author, five nurses, and four school counselors started running teaching sessions on sexual health. They started with the kindergarten students and taught students about good touch-bad touch and so on and went up to more details with the PSHE curriculum for the older grades up to Grade 10. Lesson outlines were sent to parents for their consent and they had an option to opt-out if they felt, for whatever reason, it was inappropriate for their child.

Observations on student perceptions:

On a personal level, it was an eye-opener for the author to see firsthand how less the students knew about the right things on sexuality, irrespective of which grade they were.

It was also heartwarming to see the students warm up to the topic and slowly break out of their shells to discuss

A sense of trust and rapport was formed between students and “trusted adults”

At the end of each session, anonymous questions regarding sexuality were collected from the students, which helped to get a feel of what the students were grappling with and to tailor the teaching materials accordingly.

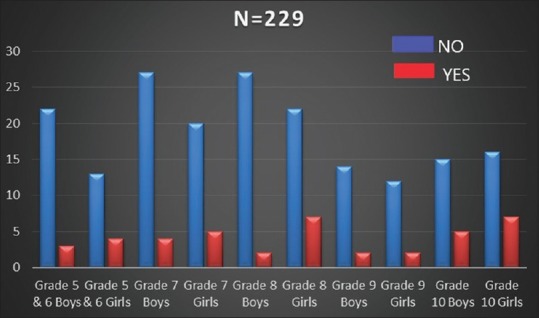

Cultural inhibitions: The author's reflective journey through these happenings also brought her face to face with the cultural issues which are obstacles for students to have an open conversation about sexual issues. The author asked the students during some of the sessions if any of them discussed anything related to sexuality with their parents. The summary of responses is depicted in Figure 2:

Figure 2.

Whether Students Ever Discussed Sexuality Related Issues with Parents or not

Only 17.9% of students in grades 5 to 12 (age-groups of 10 to 19) have ever had a conversation with their parents about sexuality. The 8th-grade boys recorded the lowest of 7%. Among middle year students, girls (29%) in general, more than the boys (11%), seem to talk more with their parents regarding sexual things, but when we're asked specifically, it was found that most parents had talked to the girls only about menarche and menstruation-related things. Overall, these interactions with students increased the author's understanding of needs and gaps.

Perceptions of support staff

Nearly 5 out of 150 Class-IV workers who underwent routine annual health exams had sexually transmitted diseases. On informal conversations with support staff, the author found that many in this group of employees have skewed perceptions on various sexuality-related issues and lacked knowledge even on crucial must-know things.

Discussions with peers and the health team

In May 2017, the author had multiple discussions with some of her peers, especially, a South African family physician, An Australian public health specialist who heads Global Health in Singapore, an Indian GP who is also an academician.

Few things that stood out from these discussions:

Sexual health and the right education on sexuality-related issues is a big need in the Indian context and seems to be a need in many other developing nations as well.

A lot of Western literature and curriculum are available on this subject but those relevant to Indian/Asian population is appallingly low

A multi-pronged strategy is needed to get this introduced into schools and it needs advocacy at multiple levels of stakeholders

The author had a few sessions with the health team in the school and all members felt that this may be something worthwhile working on.

Discussion

The WHO emphasizes a positive and respectful approach to sexuality and sexual relationships, as well as the possibility of having pleasurable and safe sexual experiences, free of coercion, discrimination, and violence.[2] Primarily, during adolescence (10–19 years) provision of effective sex education and other supportive sexual health services can be crucial preventative tools.[3] Failure to fully address the sexual health issues in children and adolescents results in several negative sexual and reproductive health outcomes,[4] such as teenage pregnancy, unsafe abortions, sexually transmitted infection (STI), HIV/AIDS, and sexual violence, the rates of which are already on the rise. The gender inequality in India[5] and growth in technology leading to cybersex crimes don't make the situation any less grim.[6] Cyber-bullying and sexting are just some of the modern challenges that young people face. These lead to larger questions about how we can appeal to the hearts of school children and help them consider the consequences of their actions and to correctly exercise their sexual rights responsibly.

The global scenario

In many developed nations, sexual health in schools is restricted to sex education and just provision of contraception and thus lack comprehensiveness. To combat 850,000 teen pregnancies,[7] 9.1 million youth with STIs,[8] the US government-funded the Personal Responsibility Education Program. In the USA, by the age of 18, 70% of girls and 62% of boys have initiated vaginal sex.[9] In the UK, from the 1990s, Sex and Relationships Education (SRE) is officially on the national curriculum and now personal, social, health, and economic education (PSHE) is given statutory status.[10] In the rest of Europe, the Sex Education Forum (SEF), favoring mandatory sex education in all English schools, points to Finland and Holland as good examples. In China, according to state requirements, school-based sexuality education should be delivered within the context of health education in all secondary schools.[11]

In many developing nations, provision for sexual health education in schools is rudimentary with huge issues with implementation and comprehensiveness. For many of the governments, resource allocation, training, and cultural aspects present major obstacles. Nigeria's development is compromised by the sexual health issues afflicting one-third of its population which is between the ages of 10 and 24.[12] But Nigeria reports having translated school-based comprehensive sexuality education (CSE) into near-nationwide implementation.[13] Patchy implementation of school-based sexual health interventions is happening in Uganda.[14] Sex Education in schools became a compulsory part of the South African school curriculum when outcomes-based education (OBE) was implemented in 1994.[15,16] In Nepal, UNFPA supports the delivery of quality CSE and reproductive health services in schools.[17] In Thailand, though all public schools provide CSE instruction, the “lecture” methodology does not help students to develop their thinking skills.[18] Cambodia unveiled CSE in 2013 but is being implemented only in 5 out of 24 provinces.

The Indian scenario

About 28% of the total Indian population of 1.2 billion is below age 15 and 68% of them attend some form of school.[19] India is home to more than 243 million adolescents who account for a quarter of the country's population.[20] Sathe and Sathe's study among school-going adolescents in Pune revealed several misconceptions regarding menstruation, masturbation, nocturnal emission, premarital sex, pregnancy, and so on.[21] Another study by Ramadugu et al.[22] shows a high incidence of sexual contact in school-going boys and girls.

Sex education at the school level has attracted strong objections and apprehension from all areas of the society, including parents, teachers, and politicians and is banned in 6 out of 29 states. Some opponents argue that sex education has no place in India with its rich cultural traditions and ethos.[23] Both teachers and parents are uncomfortable talking about sexuality, leaving the children at the mercy of unstandardized sites, books, and peer misinformation which often give them a skewed understanding of sexuality. Even in schools where sex education has been tried, it has been superficial and does not empower the individual student with enough evidence-based scientific, ethical, and moral knowledge about sexuality so as help them make informed healthy sexual choices. Khandelwal noted that “Sex education has barely anything to do with sex in the various schools of Delhi-NCR”.[24,25] The new family life education (FLE) curriculum lacks components that are essential to comprehensive sexuality education.[26]

The sexual and reproductive health needs of adolescents in India are currently overlooked or not understood by the Indian healthcare system. The well-known sexual medicine expert Dr. Kothari highlights the lack of proper knowledge on sexual health among doctors and the public which has spawned misinformation and “faith cures” at the cost of the hapless patients.[27] Many school-going children in India, both boys and girls, are victims of sexual abuse.[28,29] Mass media has had a highly influential, yet mixed impact. Those exposed to sexually implicit content on the television and internet are more likely to initiate early sex, which comes with a host of negative implications that they are often unequipped to deal with.[30]

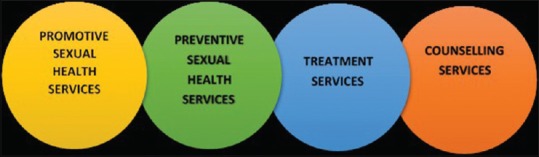

There are guidelines by the Committee on the Rights of the Child (CRC, WHO), 2013 need to be adhered to when providing sex education.[31] India is under obligation to provide free and compulsory comprehensive sexuality education, as it is one of the signatories to the 1994 United Nations International Conference on Population and Development (ICPD).[32] All these unequivocally call for a 'wholistic model' for the provision of comprehensive sexual health in schools, which UNFPA (United Nations Population Fund) captures so well[33]:

Based on all these and the author's personal journey in exploring the perceptions and needs for sexual health in the school, the author would like to propose a wholistic model of comprehensive sexual health in schools with a four-pronged approach [Figure 3]:

Figure 3.

The Four-Pronged Approach to Wholistic Model of Comprehensive Sexual Health Provision in School Community

Prong 1: Promotive sexual health services[34]

This can be offered in low resource settings by any appropriately trained teacher, school counselor or health worker and in high resource settings by family physician or pediatrician, or any trained doctor or nurse.

This should be a comprehensive sexuality education with a rights-based and gender-focused approach. This should ideally go beyond information but should help young people to explore and nurture positive values regarding their sexual and reproductive health, include discussions about family life, relationships, culture, and gender roles, and also addresses human rights, ethics and moral values, gender equality, and threats such as discrimination and sexual abuse. In addition, the skills they develop from sexuality education should be linked to more general life-skills, such as communication, listening, decision-making, negotiation and learning to ask for and identify sources of help and advice from parents, caregivers, and professionals.[34] Age and culturally appropriate information should be delivered in a safe environment for participants.[35,36]

Promotive services should also involve “health protection” in terms of establishing solid school sexual health policy,[37] school substance abuse policy, and so on.

Prong 2: Preventive sexual health services

In low resource settings, preliminary level screening and prevention can be done by an appropriately trained teacher, school counselor, or health worker and referred to when problems are identified. In high resource settings a family physician or a pediatrician, or any trained doctor or nurse can offer advanced level screening and prevention. This should involve screening for STIs,[38] high-risk behavior,[39] mental health issues, substance abuse, sexual abuse as well as provision for vaccinations e.g. HPV.

Prong 3: Treatment services

Treatment services can be offered by a family physician or a pediatrician, or any trained doctor or nurse. This should involve treating STIs, mental health issues, substance-related issues, etc.

Prong 4: Counseling services

Counseling services can be offered in low resource settings by any appropriately trained teacher, school counselor or health worker and in high resource settings by a family physician or a pediatrician, or any trained doctor or nurse. This should involve counseling regarding STIs, relationship issues, any other sexuality-related issues brought up by the students, mental health issues, substance-related issues, counseling for parents, and so on.

Conclusion

The author's journey as a family physician in a school setting has opened the author's eyes to the sexual health perceptions and needs in a school community and prompted her to explore the possibility of a wholistic model for the provision of comprehensive sexual health in schools with the four-pronged approach described in the article. The author is still figuring out how such a wholistic model can be established at minimum cost, time and manpower, and how to develop advocacy for this. Moreover, this journey has led the author to firmly believe that a family physician has emerging significant roles to play in “spaces between the home and the clinic” and schools, for sure is one such space.

Financial support and sponsorship

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Tsui AO, Wasserheit JN, Haaga JG, editors. Reproductive Health in Developing Countries: Expanding Dimensions, Building Solutions. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 1997. National Research Council (US) Panel on Reproductive Health. Summary Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK233272/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.WHO. Defining sexual health. Geneva: WHO; 2006. Available from: http://www.who.int/topics/sexual_health/en/ [Google Scholar]

- 3.WHO. The sexual and reproductive health of younger adolescents research issues in developing countries: Background paper for a consultation. Geneva: WHO; 2011. Available from: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/44590/1/9789241501552_eng.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organization. Measuring sexual health: Conceptual and practical considerations. Geneva: WHO; 2010. Available from: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/70434/1/who_rhr_10.12_eng.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 5.Namasivayam A, Osuorah DC, Syed R, Antai D. The role of gender inequities in women's access to reproductive health care: A population-level study of Namibia, Kenya, Nepal, and India. Int J Womens Health. 2012;4:351–64. doi: 10.2147/IJWH.S32569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Evening Standard UK: Cyber sex crimes against children have surged by 44%, NSPCC reveals: 1st June 2017. Available from: http://www.standard.co.uk/news/crime/cyber-sex-crimes-children-increase-44-nspcc-a3554031.html .

- 7.Shaik S, Rajkumar RP. Internet access and sexual offences against children: An analysis of crime bureau statistics from India. Open Journal of Psychiatry & Allied Sciences. 2015;6:112–6. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Klein JD Committee on Adolescence. Adolescent pregnancy: Current trends and issues. Pediatrics. 2005;116:281–6. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-0999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weinstock H, Berman S, Cates W., Jr Sexually transmitted diseases among American youth: Incidence and prevalence estimates, 2000. Perspectives Reprod Sexual Health. 2004;36:6–10. doi: 10.1363/psrh.36.6.04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.PSHE Association. Available from: https://www.pshe-association.org.uk/curriculum-and-resources/curriculum .

- 11.Aresu A. Sex education in modern and contemporary China: Interrupted debates across the last century. International Journal of Educational Development. 2009;29:532–41. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shittu LA, Zachariah MP, Ajayi G, Oguntola JA, Izegbu MC, Ashiru OA. The negative impacts of adolescent sexuality problems among secondary school students in Oworonshoki Lagos. Sci Res Essay. 2007;2:23–8. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huaynoca S, Chandra-Mouli V, Yaqub N, Jr, Denno DM. Scaling up comprehensive sexuality education in Nigeria: From national policy to nationwide application. Sex Educ. 2014;14:191–209. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shuey DA, Babishangire BB, Omiat S, Bagarukayo H. Increased sexual abstinence among in-school adolescents as a result of school health education in Soroti District, Uganda. Health Educ Res. 1999;14:411–9. doi: 10.1093/her/14.3.411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Francis DA. Sexuality education in South Africa: Three essential questions. International Journal of Educational Development. 2010;30:314–9. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thaver L. 2012: Sexual and HIV/AIDS Education in South African Secondary Schools. Available from: http://wwwosisaorg/buwa/south-africa/sexual-and-hivaids-education-south- african-secondary-schools .

- 17.UN Fact Sheet 2016: Comprehensive Sexuality Education in Nepal. Available from: http://un.org.np/sites/default/files/Factsheet%20sexuality%20education_0.pdf .

- 18.UNICEF 2016: Review of Implementation of Comprehensive Sexuality Education. Thailand: Available from: https://www.unicef.org/thailand/comprehensive_sexuality_education.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 19.National family health survey 2015-16. Mumbai: International Institute of Population sciences; 2016. Available from: http://rchiips.org/NFHS/pdf/NFHS4/India.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 20.UNICEF India Press Reslease: 2011. Available from : http://unicef.in/PressReleases/87/Adolescence-An-Age-of-Opportunity .

- 21.Sathe AG, Sathe S. Knowledge and behavior and attitudes about adolescent sexuality amongst adolescents in Pune: A situational analysis. J Fam Welfare. 2005;51:49–59. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ramadugu S, Ryali V, Srivastava K, Bhat PS, Prakash J. Understanding sexuality among Indian urban school adolescents. Industrial Psychiatry J. 2011;20:49–55. doi: 10.4103/0972-6748.98416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ismail S, Shajahan A, Sathyanarayana Rao TS, Wylie K. Adolescent sex education in India: Current perspectives. Indian J Psychiatry. 2015;57:333–7. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.171843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Available from: http://www.dnaindia.com/india/report-sex-education in-schools- limited-to-good-badtouch-2428007limited-to-good-badtouch-2428007 .

- 25.Tripathi N, Sekher TV. Youth in India ready for sex education Emerging evidence from national surveys. PLoS One. 2013;8:e71584. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0071584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.TARSHI. A Review of the Revised Sexuality Education Curriculum in India. 2007. [Last accessed on 2015 Sep 05]. pp. 1–13. Available from: http://www.tarshi.net/downloads/review_of_sexuality_education_curriculum.pdf .

- 27. Available from: http://www.thehindu.com/news/cities/Hyderabad/Discussing-sexual-education-still-a-taboo-expert/article11433896.ece .

- 28.Jejeebhoy SJ, Bhot S. New Delhi: 2003 Non–consensual sexual experiences of young people: A review of the evidence from developing countries. Population Council Working paper No16. pp. 23–5. http://citeseerxistpsuedu/viewdoc/downloaddoi=10111759529&rep=rep1&type=pdf .

- 29.India: Ministry of Women and Child Development, Govt of India; 2007. Study on Child Abuse. Available from: https://www.childlineindia.org.in/pdf/MWCD-Child-Abuse-Report.pdf .

- 30.Shashi Kumar R, Das RC, Prabhu HR, Bhat PS, Prakash J, Seema P, et al. Interaction of media, sexual activity and academic achievement in adolescents. Med J Armed Forces India. 2013;69:138–43. doi: 10.1016/j.mjafi.2012.08.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Behere PB, Mulmule AN, Datta SS. Psychosocial intervention of sexual offenders. Health Agenda. 2015;3:2. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kumar VB, Kumar P. Right to sexuality education as a human right. J Fam Welf. 2011;57:23–9. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Available from: http://www.unfpa.org/comprehensive-sexuality-education .

- 34.Inman DD, van Bakergem KM, LaRosa AC, Garr DR. Evidence-based health promotion programs for schools and communities. Am J Prev Med. 2011;40:207–19. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2010.10.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Andrew G, Patel V, Ramakrishna J. Sex, studies or strife What to integrate in adolescent health services. Reprod Health Matters. 2003;11:120–9. doi: 10.1016/s0968-8080(03)02167-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kirby D, Laris BA, Rolleri LA. [Youth Research Working Paper, No. 2] Research. Triangle Park, NC: Family Health International; 2005. Impact of sex and HIV education programs on sexual behaviors of youth in developing and developed countries. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rabbitte M. The role of policy on sexual health education in schools: Review; The role of policy on sexual health education in schools: Review. J Sch Nurs. 2019;35:27–38. doi: 10.1177/1059840518789240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.PETER HAM, CLAUDIA ALLEN, PhD, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, Virginia: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommendations for adolescent screening and counseling. Am Fam Physician. 2012;86:1109–16. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Eaton DK, Kann L, Kinchen S, Shanklin S, Flint KH, Hawkins J, et al. Youth risk behavior surveillance–United States, 2011. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2012;61:1–162. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]