Abstract

BACKGROUND & AIMS:

Affordable point-of-care (POC) tests for hepatitis C (HCV) viraemia are needed to improve access to treatment in low and middle income countries (LMICs). Our aims were to determine the target limit of detection (LOD) necessary to diagnose the majority of persons with HCV eligible for treatment, and identify characteristics associated with low-level viraemia (LLV) (defined as the lowest 3% of the distribution of HCV RNA) to understand those at risk of being mis-diagnosed.

METHODS:

We established a multi-country cross-sectional dataset of first available quantitative HCV RNA linked to demographic and clinical data. We excluded individuals on HCV treatment. We analyzed the distribution of HCV RNA and determined critical thresholds for detection of HCV viraemia. We then performed logistic regression to evaluate factors associated with LLV, and derived relative sensitivities for significant covariates.

RESULTS:

The dataset included 66,640 individuals with HCV viraemia from Georgia (44.4%), Canada (40.9%), India (8.1%), Cambodia (2.6%), Egypt (1.6%), Pakistan (1.3%), Cameroon (0.4%), Indonesia (0.2%), Thailand (0.2%), Vietnam (0.1%), Malaysia (0.05%), and Mozambique (0.02%). The 97% LOD was 1,318 IU/mL (95% CI 1298.4, 1322.3). Factors associated with LLV were younger age 18–30 vs. 51–64 years (OR 2.56 95% CI 2.19, 2.99), female vs. male sex (OR 1.32, 95% CI 1.18, 1.49), and advanced fibrosis stage F4 vs. F0–1 (OR 1.44, 95%CI 1.21, 1.69). Only the younger age group had a decreased relative sensitivity below 95% at 93.3%.

CONCLUSIONS:

In this global dataset, a test with an LOD of 1,318 IU/mL would identify 97% of viraemic HCV infections among almost all populations. This LOD will help guide manufacturers in the development of affordable POC diagnostics to expand HCV testing and linkage to care in LMICs.

Keywords: Hepatitis C Virus, diagnosis, point-of-care

LAY SUMMARY:

We created and analyzed a dataset from 12 countries with 66,640 participants with chronic hepatitis C virus infection. We determined that about 97% of those with viraemic infection had 1300 International Units/mL or more of circulating virus at the time of diagnosis. While current diagnostic tests can detect as little as 12 International Units/mL of virus, our findings suggest that increasing the level of detection closer to 1300 would maintain good test accuracy and will likely allow for more affordable portable tests to be developed for use in low and middle income countries.

INTRODUCTION

Globally, viral hepatitis is responsible for 1.34 million deaths [1] [2] and more than 50 million of the estimated 70 million cases of chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) occur in low and middle income countries (LMICs) [3]. The World Health Organisation (WHO) defined goals towards the elimination of viral hepatitis as a public health threat, with a 90% reduction in new infections, and a 65% reduction in mortality by 2030 [1, 4]. Achievement of these targets requires scale-up of access to affordable testing and treatment alongside interventions for HCV prevention (harm reduction and safe blood donation and injections) [5]. Progress in treatment scale-up is encouraging with more than 3 million treated with direct acting antivirals since 2015, however, testing coverage and diagnosis rates are still less than 10% in LMICs [6].

Approximately 15–45% of persons infected with HCV will spontaneously clear the virus [7, 8] and therefore confirmation of HCV viraemia is necessary to identify those needing treatment. The standard diagnostic algorithm recommended by WHO includes an initial HCV antibody test followed by confirmatory testing for viraemia with either a nucleic acid test (NAT) for HCV RNA or core antigen (HCVcAg) where RNA tests are not available [9–11]. High proportions of those with positive antibody fail to have confirmatory testing and are never linked to treatment [12, 13]. Further, available tests for viraemia are expensive, and require advanced laboratory facilities, electricity, water, and refrigerated reagents. Few LMICs have testing policies or the requisite laboratory infrastructure in place [13, 14] [15].

Innovations in testing technology, and research to inform optimal implementation strategies for HCV in LMICs are needed [9, 16] [15]. A rapid, affordable, easy-to-use test for confirmation of HCV viraemia at the point-of-care (POC) that can be deployed on a large scale has the potential to improve outcomes across the diagnosis and care continuum, particularly in high HCV prevalence settings [16–18].

Presently, there are no data to inform limits of detection (LOD) for WHO prequalification criteria for a POC HCV viraemia test. Thus, POC tests are held to the same standards as laboratory-based NAT. The laboratory-based Abbott RealTime HCV viral load test, for example, is able to detect and measure HCV RNA down to 12 international units per milliliter (IU/mL) with >99% sensitivity; similarly, the Roche COBAS®TaqMan® HCV Test reports an LOD of 15 IU/mL [19]. The laboratory-based Abbott ARCHITECT HCVcAg test has an LOD corresponding to 3,000 IU/mL with 93.4% sensitivity [20]. Requiring POC assays to achieve the same prequalification criteria as laboratory assays may limit the ability to expand HCV testing and treatment in LMICs. The POC Genedrive® HCV assay, however, acquired European in-vitro diagnostics approval this year with an LOD of 2362 IU/mL [21], but is not yet WHO prequalified. Additionally, Cepheid Xpert® HCV Viral Load finger-stick assay detects as little as 40 IU/mL and can utilize consolidated near-patient Xpert platforms or the POC Omni version [22].

A consensus target product profile (TPP) in 2017 outlined price targets and operational characteristics for a near patient HCV viraemia test [18] including but not limited to: a minimal LOD of 1000–3000 IU/mL, minimal test sensitivity of 95%, test cost <$15 though ideally <$5, and instrument cost <$20,000 but ideally <$2,000. Currently, available platforms struggle to meet these price targets. Data are needed to estimate the clinical sensitivity of the potential minimum LOD recommendations. Integrating NAT data outlined above with the goals from the TPP, we hypothesize that a POC assay with an LOD of 1,000 IU/mL (3 log IU/ml) would have >97% clinical sensitivity for confirming HCV viraemia. A single-step POC test would allow for accessible, low-cost testing of viraemia without loss to follow-up in LMICs, despite having a lower analytical sensitivity [18, 23, 24]. Our objective is to determine the requisite LOD for an affordable POC assay to diagnose the majority of persons with chronic HCV, and to identify characteristics of those with low-level viraemia (LLV) who might be missed by a less sensitive test.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Study Design

We assembled a cross-sectional dataset of the first available HCV RNA measurement for HCV antibody positive persons with viraemia from high, moderate, and low HCV prevalence settings in twelve countries (Cambodia, Cameroon, Canada, Egypt, Georgia, India, Indonesia, Malaysia, Mozambique, Pakistan, Thailand, and Vietnam) with representation of the six major HCV genotypes, a broad range of liver fibrosis stages, and varying prevalence of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and hepatitis B virus (HBV) co-infection. To test our hypothesis, we analyzed the distribution of HCV RNA at the time of diagnosis, and performed bivariate and multivariable analyses to identify demographic and clinical characteristics associated with LLV, defined as those in the lowest 3% of the distribution of HCV viral load (i.e., those missed by a test with 97% clinical sensitivity).

We performed a cross-sectional analysis of initial HCV viral load data and linked demographic (age, sex, country of testing) and clinical (HIV and HBV co-infection, HCV genotype, fibrosis stage) data collected between January 1, 2007 and June 1, 2017. We included males and females of all ages with detectable quantitative HCV RNA. We excluded participants with missing age or sex demographics and those on HCV treatment. We grouped countries by WHO regions: African, Americas, Eastern Mediterranean, European, South East Asia, and Western Pacific.

Data Sources

We identified potential patient cohorts for inclusion from two main sources: the WHO global hepatitis programme contacts database that includes implementing partners and international HCV researchers, and a PubMed literature search using the search terms “HCV RNA quantification” and “cohort study” to identify additional cohorts of persons with HCV infection. Criteria for potential inclusion in this analysis were available HCV RNA quantification linked to comprehensive demographic and clinical data among populations outside of the United States. We contacted study authors, and established a working group with all respondents who agreed to share data. Supplement Figure 1 shows a flow-chart of contributing sites and countries, and Table 1 summarises characteristics of the source data, including: HCV epidemiology of the country or region of origin (prevalence, population affected, World Bank country classification), patient inclusion and exclusion criteria if from a research cohort, and reason for HCV testing.

Table 1.

Data source characteristics including site, country, World Health Organization region, dates of sample collection, country hepatitis C virus (HCV) epidemiology and World Bank economy classification, sample size, sample population, testing purpose* (targeted, clinical, routine, reference laboratory, mixed), and enrollment inclusion and exclusion criteria (for research cohorts).

| Site, Location, Region | Dates of Collection | Country HCV Epidemiology[3, 39], Economy[40] | Sample Size, Population | Testing Purpose* | Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria and Cohort Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Centre Pasteur, Yaoundé, Cameroon, African | 2010 – 2016 | Viraemic prevalence: 0.7% Pop. Infected: baby boomers, iatrogenic Genotype Distribution: G1 44.8%, G2 24.3%, G4 30.7% Economy: Lower-middle | 4,861, Specialty clinics | Clinical | |

| British Columbia Center for Disease Control Hepatitis C Testers Cohort (BC-HTC), Vancouver, Canada, Americas | Jan. 2007 – Dec. 2016 | Viraemic prevalence: 0.6% Pop. Infected: IDU, ex-IDU, iatrogenic, unknown. Incident infections are occurring in PWID, males 2x more likely than females Genotype Distribution: G1 50.3%, G2 15.4%, G3 22.3%, G4 2.3% Economy: High | 27,448, General | Reference laboratory | BC-HTC includes data for >95% of all individuals tested for HCV in the province of British Columbia. Data is collected and merged from the province public health laboratory [41]. |

| Egyptian Liver Research Institute and Hospital, Mansoura, Egypt, Eastern Mediterranean | Viraemic prevalence: 6.3–14.7% Pop. Infected: general, iatrogenic Genotype Distribution: G1 3.8%, G3 0.8%, G4 93.1% Economy: Lower-Middle | 1,063, General | |||

| Georgia HCV Elimination Program, Tbilisi, Georgia, European | April 2015 – May 2017 | Viraemic prevalence: 4.2–7.7% Pop. Infected: IDU, iatrogenic transmission, 50% of prison population Genotype Distribution: G1 61%, G2 11.0%, G3 27% Economy: Lower-Middle | 29,568, General | Mixed: targeted, routine, clinical | The Georgia HCV Elimination Program is a partnership between the Georgia Ministry of Health, the US Centers for Disease Control, and Gilead Sciences [42–44] |

| Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF), 1. Cambodia, Western Pacific 2. Mozambique, African 3. Pakistan, Eastern Mediterranean | Sept. – Dec 2016 | Cambodia Viraemic prevalence: 2.3% Pop Infected: IDU, MSM, iatrogenic Genotype Distribution: G1 24.0%, G3 20.0%, G6 56.0% Economy: lower-middle Mozambique Viraemic prevalence: no data Genotype Distribution: no data Economy: low Pakistan Viraemic prevalence: 3.8–6.7% Pop. Infected: IDU, iatrogenic Genotype Distribution: G1 10.9%, G2 3.8%, G3 79%, G41.6%, G5 0.1%, G6 0.1%, Mixed 8.3% Economy: lower-middle | Cambodia: 1737, general Mozambique: 13, HIV infected Pakistan: 1293, general | Targeted | Cambodia & Mozambique: Observational cohorts. Inclusion: ≥ 18 years old, detectable HCV RNA, able to provide written informed consent Pakistan: Retrospective analysis of operational data. Inclusion: >= 18 years old, detectable HCV RNA. |

| TREAT Asia, Kirby Institute Jakarta, Indonesia; Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia; Bangkok, Thailand; Hanoi, Vietnam South East Asia | Dec 2013-Jan 2015 | Viraemic prevalence: Region = 0.7–1.2% Pop. Infected: IDU, MSM, iatrogenic Genotype Distribution: G1 35.2%, G2 11.1%, G3 19.9%, G4 0.9%, G5 0.4%, G6 30.8%, Mixed 1.7% Economy: Indonesia – Lower-Middle Malaysia – Upper-Middle Thailand – Upper-Middle Vietnam – Lower-Middle | 413, HIV infected | Targeted | Inclusion: HIV-infected patients under care at participating sites. Detectable HCV antibody within 6 months of enrollment. Exclusion: < 18 years old, CD4 count < 200, Child-Pugh score > A, ascites, encephalopathy, bleeding esophageal varices, liver cancer, pregnant, breastfeeding or the male partner of a pregnant female [45]. |

| Y.R. Gaitonde Centre for AIDS Research and Education, Chennai, India, South East Asia | 2010 – 2016 | Viraemic prevalence: 0.5% Pop. Infected: IDU, iatrogenic Genotype Distribution: G1 24.0%, G3 54.4%, G4 5.8%, G5 0.2%, Mixed 15.6% Economy: Lower-middle | 5,476, IDU, MSM, HIV infected | Mixed: targeted and routine | Four study cohorts: 1. Respondent-driven sampling strategy used for recruitment. Inclusion: >18 years old, self-report of IDU in prior 2 years, provide informed consent, valid referral coupon. [46] 2. Inclusion: > 18 years old, provide written informed consent, report IDU in prior 6 months [47]. 3. CDOT [48] 4. Inclusion: > 18 years old, provide informed consent, self-reported history of IDU in prior 5 years, no intention of migrating for 2 years during study period [49]. |

Pop = Population; IDU = injection drug user(s); G1 = genotype 1; G2 = genotype 2; G3 = genotype 3; G4 = genotype 4; G5 = genotype 5; G6 = genotype 6; US = United States; HIV = human immunodeficiency virus; AIDS = acquired immunodeficiency syndrome

1) targeted among specific high-risk populations (injection drug users, birth cohorts, healthcare workers), 2) clinical (testing of those with clinical signs or symptoms or laboratory features suggestive of hepatitis), 3) and routine from large-scale screening (antenatal clinics, blood donors, seroprevalence surveys).

We determined the main source of patient samples and basis for HCV testing from study protocols or direct communication with collaborators. Reason for testing was categorized as: 1) targeted among specific high-risk populations (persons who inject drugs, birth cohorts, healthcare workers), or 2) clinically indicated (ie. testing of those with clinical signs or symptoms or laboratory features suggestive of hepatitis), or 3) routine as part of large-scale screening programmes (ie. antenatal clinics, blood donors, seroprevalence surveys). We included data from one large reference laboratory in a high-income setting (Canada) as a comparison to LMICs.

Data Concatenation

We predefined a protocol for data concatenation. We outlined categories and associated dummy variables for all categorical variables (age, sex, country, WHO region, HCV genotype, Fibrosis stage). HCV viral load measurements at each site were reported in IU/mL. Sample specifics (serum or plasma) and platform used for quantification were collected where available. We determined fibrosis stage either from transient elastography (FibroScan®) results reported in Metavir stage, or calculated from Fibrosis-4 score [25, 26] as these scores correlate well with FibroScan® [27–29]. For those with a Fibrosis-4 score < 1.45, we assigned Metavir stage F0-F1. For scores between 1.45 and 3.25, we assigned stage F2-F3, and scores above 3.25 we assigned to stage F4.

Statistical Analysis

We employed descriptive statistics to derive the HCV viral load distribution in log10 IU/mL for initial HCV RNA among all patients in the combined dataset. From this distribution, we identified the LOD levels of HCV RNA in IU/mL corresponding to the 95%, 97%, and 99% percentiles—i.e. the level of HCV RNA below which the infection would be missed. To estimate the 95% confidence interval (CI) for each LOD, we performed bootstrap and Markov chain Monte Carlo method [30] to randomly simulate a population of 10,000 patients from the total dataset. We then calculated the LOD at the 95%, 97%, and 99% percentiles from this sample population, and repeated the procedure 10,000 times to obtain an LOD range for each percentile. We then calculated the 95% CIs from these sample distributions.

We defined LLV as HCV RNA in the lowest 3% of the distribution, below the LOD corresponding to the 97th percentile determined above. We then calculated summary statistics for covariates of interest and tested associations between each covariate and the odds of having LLV. We used a stepwise approach to construct a multivariable logistic regression model of the odds of LLV. Covariates remained in the multiple logistic regression model when their p-value was ≤ 0.05 and we found no substantial multicollinearity. We tested for effect modification with predefined stratified analyses: 1) HIV subset analysis 2) HBV subset analysis 3) fibrosis stage with transient elastography data only. We also assessed the effect of varying the fibrosis classification thresholds of the Fibrosis-4 score. First, we shifted the cutoffs toward F4: scores < 1.20, we assigned stage F0-F1, 1.20 to 3.0 stage F2-F3, and scores > 3.0 stage F4. We then shifted the cutoffs away from F4: scores < 1.60 stage F0-F1, 1.60 to 3.45 stage F2-F3, and scores > 3.45 stage F4.

Next, we performed data imputation for the missing exposures of interest (HIV co-infection, HBV co-infection, HCV genotype, fibrosis stage) to create a dataset for sensitivity analyses. We employed parametric regression imputation with a prediction model to impute the missing values for fibrosis stage [31]. We utilized prevalence data specific to each country for HCV genotype, HIV and HBV co-infection, and imputed missing data for these variables within each country cohort. For example, we used the genotype distributions described in each country as the probabilities of having each genotype, then employed Markov-chain Monte-Carlo techniques to stochastically assign a genotype to each individual. We used the same method adapting country and sex specific HIV and HBV prevalence data.

We then used the imputed dataset to test associations between each covariate and the odds of having LLV with bivariate and multivariable logistic regression, and compared the results with the non-imputed total population dataset. Finally, we quantitatively compared the performance of the LOD from the total population dataset among the covariates with significant associations with LLV in the imputed dataset by deriving the relative percentiles from HCV RNA distributions for subsets from each significant covariate. We used R version 1.0.136 to perform all statistical analyses.

RESULTS

Dataset Characteristics

We combined data across all countries of Cambodia, Canada, Cameroon, Egypt Georgia, India, Indonesia, Malaysia, Mozambique, Pakistan, Thailand, and Vietnam to generate a dataset of 66,640 individuals with viraemic HCV infection (supplement Figure 1). Table 1 contains data source characteristics, and summarises country-level HCV prevalence data and genotype distribution.

Characteristics for the total population cohort (TPC) are presented in Table 2. Females comprised 24.4% (16,320) of participants with a median age of 48 years. Among those also tested for HIV (54.3%) and HBV (50.7%), 10.9% (3,945) were HIV co-infected, and 21.4% (7,221) were HBV co-infected. We identified the HCV genotype distribution as follows: 40.9% (27,245) genotype 1, 13.9% (9,287) genotype 2, 22.7% (15,157) genotype 3, 3.0% (2,030) genotype 4, <1% (13) genotype 5, 1.3% (889) genotype 6, < 1% (170) with mixed genotype, and 17.8% (11,849) with missing genotype data. We categorized 12,880 (38.1%) individuals as Metavir fibrosis stage F0-F1, 12,242 (36.3%) as F2-F3, and 8,644 (25.6%) as F4 among the 33,766 individuals with available fibrosis staging data (FibroScan® or Fibrosis-4 score).

Table 2.

Characteristics of 66,640 participants in a combined cross-sectional dataset from Cambodia, Canada, Cameroon, Egypt, Georgia, India, Indonesia, Malaysia, Mozambique, Pakistan, Thailand, and Vietnam with chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV). The association of covariates with low-level viraemia, HCV RNA < 1318 international units per milliliter, is indicated by the bivariate odds ratios (OR) and adjusted odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals (95% CI)—statistically significant OR are in bold font.

| Variable | Total Cohort N (Col%) | Low-level Viraemia* N (Row%) | OR (95% CI) | aOR1 (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | ||||

| <18 | 75(0.1) | 4(5.3) | 2.39(0.73,5.79) | 1.73(0.52,4.22) |

| 18–30 | 5883(8.8) | 396(6.7) | 3.06(2.68,3.49) | 2.56(2.19,2.99) |

| 31–50 | 31724(47.6) | 962(3.0) | 1.33(1.19,1.48) | 1.30(1.16,1.45) |

| 51–64 | 24173(36.3) | 556(2.3) | REF | REF |

| ≥65 | 4785(7.2) | 84(1.8) | 0.76(0.60,0.95) | 0.75(0.59,0.94) |

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 16320(24.4) | 526(3.2) | 1.1(1.00,1.22) | 1.32(1.18,1.49) |

| Male | 50320(75.5) | 1476(2.9) | REF | REF |

| Country | ||||

| Cambodia | 1730(2.6) | 34(1.9) | 0.66(0.46,0.92) | |

| Cameroon | 293(0.4) | 3(1.0) | 0.34(0.08,0.89) | |

| Canada | 27277(40.9) | 805(3.0) | REF | |

| Egypt | 1063(1.6) | 5(0.5) | 0.16(0.06,0.34) | |

| Georgia | 29569(44.4) | 780(2.6) | 0.89(0.81,0.98) | |

| India | 5430(8.1) | 360(6.6) | 2.33(2.05,2.65) | |

| Indonesia | 141(0.2) | 2(1.4) | 0.47(0.08,1.49) | |

| Malaysia | 34(0.05) | 1(2.9) | 1.51 (0.08,7.35) | |

| Mozambique | 13(0.02) | 1(7.7) | 4.16(0.23,22.02) | |

| Pakistan | 854(1.3) | 11(1.3) | 0.43(0.22,0.74) | |

| Thailand | 142(0.2) | 1(0.7) | 0.23(0.01,1.04) | |

| Vietnam | 94(0.1) | 1(1.1) | 0.35(0.02,1.59) | |

| WHO Region | ||||

| African | 306(0.5) | 3(1.0) | 0.33(0.08,0.85) | 0.21(0.05,0.65) |

| Americas | 27277(40.9) | 805(3.1) | REF | REF |

| E. Med | 1917(2.9) | 16(0.8) | 0.28(0.16,0.44) | 0.05(0.02,0.09) |

| European | 29569(44.4) | 780(2.6) | 0.89(0.81,0.98) | 0.13(0.07,0.27) |

| S.E. Asia | 5841(8.8) | 364(6.2) | 2.19(1.92,2.48) | 0.66(0.54,0.81) |

| W. Pacific | 1730(2.6) | 34(1.9) | 0.66(0.46,0.92) | 0.21(0.12,0.36) |

| HIV | ||||

| Co-Infected | 3945(5.9) | 191(4.8) | 1.57(1.34,1.84) | 1.01(0.83,1.21) |

| Negative | 32253(48.4) | 1012(3.1) | REF | REF |

| Missing Data | 30442(45.7) | 799(2.6) | NA | NA |

| HBV | ||||

| Co-Infected | 7221(10.8) | 214(3.0) | 1.08(0.92,1.25) | 1.14(0.97,1.34) |

| Negative | 26579(39.9) | 734(2.8) | REF | REF |

| Missing Data | 32840(49.3) | 1054(3.2) | NA | NA |

| HCV Genotype | ||||

| Genotype 1 | 27245(40.9) | 623(2.3) | REF | REF |

| Genotype 2 | 9287(13.9) | 261(2.8) | 1.24(1.07,1.43) | 1.25(1.07,1.45) |

| Genotype 3 | 15157(22.7) | 405(2.7) | 1.17(1.03,1.33) | 1.17(1.03,1.34) |

| Genotype 4 | 2030(3.0) | 28(1.4) | 0.59(0.39,0.86) | 1.14(0.75,1.67) |

| Genotype 5 | 13(0.02) | 1(7.7) | 3.55(0.19,18.08) | 4.22(0.05,17.15) |

| Genotype 6 | 889(1.3) | 12(1.3) | 0.58(0.31,0.99) | 0.61(0.31,1.12) |

| Mixed | 170(0.3) | 4(2.4) | 1.03(0.32,2.44) | 0.97(0.29,2.3) |

| Missing | 11849(17.8) | 669(5.6) | NA | NA |

| Fibrosis Stage | ||||

| F0-F1 | 12460(18.7) | 313(2.5) | REF | REF |

| F2-F3 | 11923(17.8) | 242(2.0) | 0.80(0.68,0.95) | 0.89(0.76,1.07) |

| F4 | 8366(12.5) | 239(2.9) | 1.14(0.96,1.35) | 1.43(1.19,1.70) |

| Missing | 33891(50.9) | 1115(3.4) | NA | NA |

Col% = column percent; Row% = row percent; REF = reference group; NA = not applicable; WHO = World Health Organization, E. = eastern; S.E. = South East; W. = western; HIV = human immunodeficiency virus; HBV = hepatitis B virus

Low-level viraemia = HCV RNA < 1318 IU/mL

aOR derived from a multivariable model adjusting for age, sex, country, HCV genotype, and fibrosis stage.

HCV Viral Load Distribution & Limit of Detection Analyses

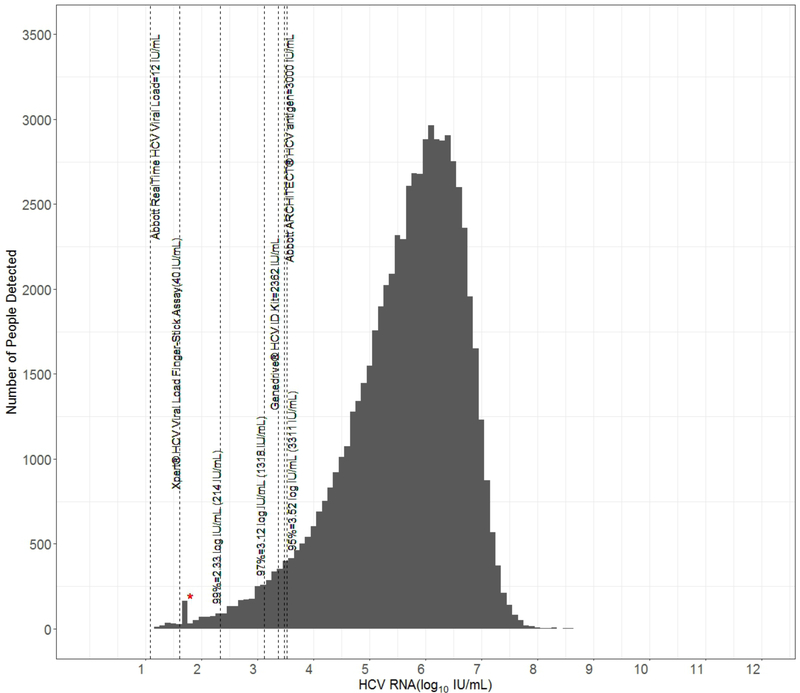

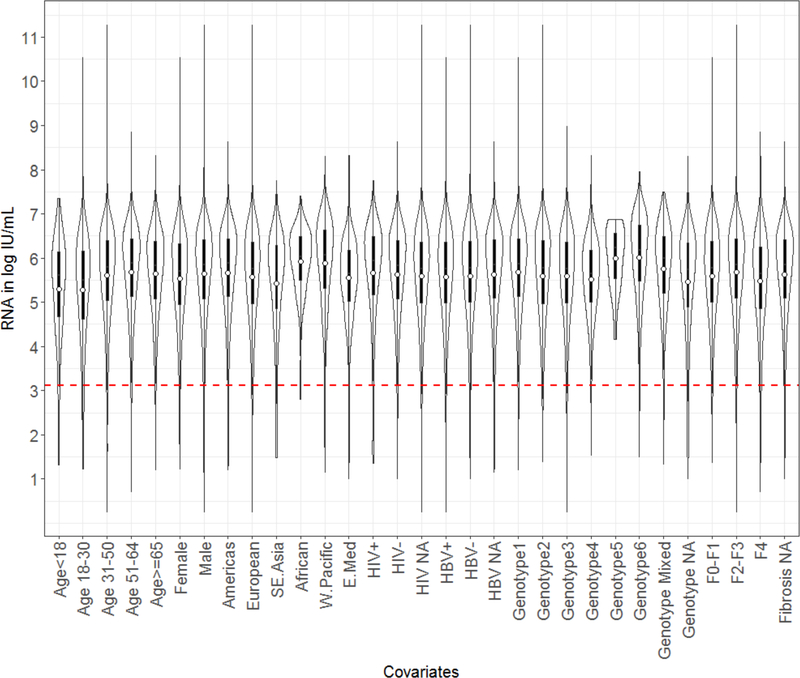

The HCV RNA (log10 IU/mL) frequency distribution is depicted in Figure 1. We derived the LOD for the 95%, 97% and 99% percentiles as: 3,311 IU/mL (95%CI 3256.3, 3368), 1318 IU/mL (95% CI 1298.4, 1322.3), and 214 IU/mL (95% CI 207.1, 218.6) respectively. We further visualized the HCV RNA distribution to compare the mean HCV RNA for each covariate with violin plots (Figure 2). Violin plots depict a box plot where, a circle denotes the median and the interquartile range is shown by box in solid black. Overlaid on this box plot is a kernel density plot indicating more data where the plot is thicker and less where it narrows. We then derived violin plots for each country to illustrate the viral load distribution by site as a surrogate approach to control for variation in quantification platforms and sampling techniques (Supplement Figure 2). The mean RNA lies between 5 and 6 log IU/mL in all cohorts.

Figure 1.

Frequency distribution of HCV RNA (log10 IU/mL) among participants in a combined cross-sectional dataset from Cambodia, Canada, Cameroon, Egypt, Georgia, India, Indonesia, Malaysia, Mozambique, Pakistan, Thailand, and Vietnam with chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV). The analytic level of detection for: a) centralized nucleic acid tests (NAT) Xpert® HCV Viral Load (40 IU/mL) and Abbott RealTime HCV Viral load (12 IU/mL), b) point of care NAT Genedrive® HCV ID Kit (2362 IU/mL) and c) Abbott ARCHITECT HCV core antigen (HCVcAg) test (in IU/ml; 3000IU/ml approximately equivalent to 3 fmol/L) are marked in comparison to the limits of detection (LOD) derived for the 99th, 97th, and 95th percentiles in the dataset. *Marks the lower LOD for tests performed in India that were detected but not quantified.

Figure 2.

Violin plot of the HCV RNA distribution (log10 IU/mL) for each covariate in the total population cohort. In each violin plot, a circle denotes the median and the interquartile range is shown by box in solid black. Overlaid on this box plot is a kernel density plot indicating more data where the plot is thicker and less where it narrows. The dashed horizontal marker indicates the 1318 IU/mL level of detection derived from the HCV RNA frequency distribution.

Identification of subgroups with low-level viraemia (LLV)

We derived the odds of association with LLV for each covariate with the following groups selected as reference because each contained the largest volume from the reference laboratory dataset in Canada: 51–64 years of age, male sex, Canada, Americas, genotype 1. Bivariate analyses indicated increased odds of LLV < 1,318 IU/mL for those 18–30 and 31–50 years of age, participants from India, the South East Asian region, HIV co-infected, and genotypes 2 and 3 (Table 2). The OR among those 18–30 years of age compared to the 51–64 year-old reference group was the highest at 3.06 (95% CI 2.68, 3.49). India had 2.33 (95% CI 2.05, 2.65) times the odds compared to Canada. South East Asia had an OR of 2.19 (95% CI 1.92, 2.48) compared to the Americas. HIV co-infected persons had an OR for LLV of 1.57 (95% CI 1.34, 1.84) compared to those without HIV. Lastly, genotype 2 had an OR of 1.24 (95% CI 1.07, 1.43) and genotype 3 OR 1.17 (95% CI 1.03, 1.33) compared to genotype 1.

In a multivariable model controlling for age, sex, WHO Region, HIV and HBV co-infections, genotype, and fibrosis stage, the 18–30 year age group, female sex, genotypes 2 and 3, and fibrosis stage F4 remained associated with increased odds for LLV (Table 2). Persons 18–30 years of age had an adjusted OR (aOR) of 2.56 (95% 2.19, 2.99) compared to the 51–64-year-old age group. For female sex, the aOR was 1.32 (95% CI 1.18, 1.49) compared to males. The aORs for genotype 2 and 3 compared to genotype 1 were 1.24 and 1.17, respectively. Lastly, for advanced fibrosis stage F4, the aOR increased to 1.44 (95% CI 1.21, 1.69) compared to stage F0–1. We did not detect significant interaction between: 1) sex and fibrosis stage, 2) genotype and country, 3) genotype and sex, 4) genotype and age group.

Stratified and Sensitivity Analyses

Stratified analyses for HIV and HBV co-infection did not suggest an effect measure modification for either covariate (Tables 2 and 3). A subset analysis of those with Fibroscan® results did not differ from that of the total dataset population (Supplement Table 4). Similarly, sensitivity analyses varying the cutoff thresholds for fibrosis stage classification by Fibrosis-4 scores did not impact the associations found for fibrosis stage and LLV (data not shown).

Characteristics for the cohort after missing data imputation for HIV, HBV, genotype, and fibrosis stage are presented in supplement Table 6. Now 6.3% (4169) are classified as HIV-coinfected (compared to 5.9% in the TPC and 10.9% among those tested, Table 2), and 12.2% (8161) as HBV co-infected (10.8% in TPC, 21.4% among those tested). The genotype distribution was similar to the TPC. Fibrosis stage categories were also similar to those with data in the TPC. In the imputation regression analyses, significant associations with LLV remained after multivariable adjustment for: age groups 18–30 (aOR 2.44) and 31–50 (aOR 1.29) years, female sex (aOR 1.31), participants from South East Asia (aOR 1.59), and fibrosis stage F4 (aOR 1.14) (Supplement Table 5). The increased odds among HIV co-infection, and HCV genotypes 2 and 3 in the total population cohort attenuated in the imputed dataset.

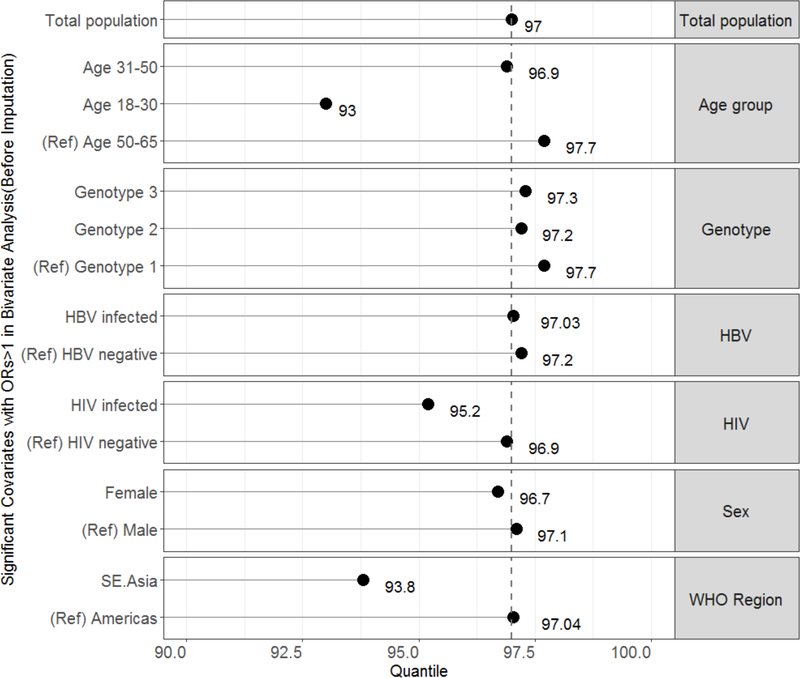

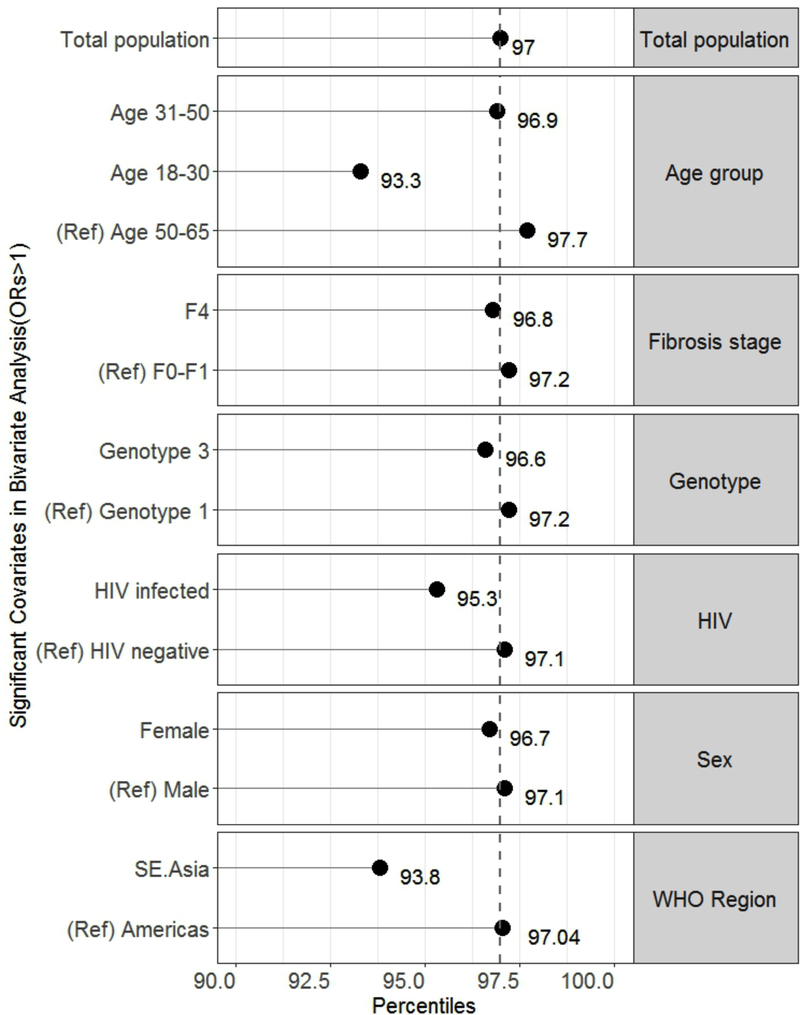

Relative percentiles for significant covariates

While an HCV RNA of 1318 IU/mL correlated to the 97th percentile in the total population dataset, the relative percentiles corresponding to the 1318 IU/mL LOD for significant covariates were: 93% for age group 18–30, 96.7% for females, 93.8% for participants from South East Asia, 95.3% for HIV co-infected, and 96.8% for fibrosis stage F4 (Figure 3a). Though genotypes 2 and 3 had increased odds for LLV, the relative percentiles remained > 97%. All percentiles were similar in the imputed dataset sensitivity analyses (Figure 3b).

Figure 3.

Graph of relative percentiles of HCV viraemia corresponding with the limit of detection derived from the total population dataset (1318 IU/mL) for covariates significantly associated with low-level viraemia in the (A) total population dataset and (B) imputed dataset. The reference (ref) groups are included for each category. The dashed vertical line marks the 97th percentile from the total population dataset.

DISCUSSION

This dataset of 66,640 individuals from twelve countries representative of six global regions represents the largest and most comprehensive dataset assembled to address the issue of clinical sensitivity of different LODs for detection of HCV viraemia. Our data confirm that with an LOD of 1,318 IU/mL (3.12 log IU/mL) 97% of viraemic HCV infections would be identified. These data further support the recent European Association for the Study of the Liver recommendation for an LOD of 1,000 IU/mL among diagnostic nucleic acid assays for use in LMICs [32]. While several covariates were associated with increased odds for LLV below 1,318 IU/mL, we report a relative sensitivity below 95% only for the 18–30 year age group (93.6% sensitivity) and among participants in South East Asia (93.8% sensitivity); genotypes 2 and 3 were associated with LLV but the relative sensitivity remained > 97%. The prevalence of LLV among the 18–30 year age group in this study may reflect fluctuating viraemia that occurs with early HCV infection [33, 34]. Of note, many of the participants from sites in South East Asia were active injection drug users and may also have had early HCV infection. We have insufficient data in the TPC to conduct a subset analysis of people who inject drugs.

Our findings differ from previous studies that evaluated HCV viral load quantification as many were designed to evaluate predictors of high-level viraemia; however, the degree of LLV we describe is similar to an evaluation of 2,472 persons with genotype 1 infection [35]. Another study of 148 persons with HCV infection found lower levels of circulating HCV RNA among those with decompensated cirrhosis [36]. We captured a trend toward LLV, but this was not sufficient to alter the relative sensitivity of the LOD in this sub-population. From the available data, we could not identify those who had decompensated cirrhosis within the F4 stage. Therefore, the OR may be slightly diminished by the number of participants with compensated cirrhosis in this group who still have abundant healthy hepatocytes that allow for HCV replication. Prior studies reported higher HCV RNA levels among those with HIV [37, 38]. In contrast, our data suggest increased odds for LLV among those with HIV co-infection and a decrease in the sensitivity of the LOD to 95.2%. Data on use of antiretroviral therapy and level of viral load suppression were not available from all data sources, and therefore level of HCV viral load among those with advanced stage HIV either not receiving or failing on therapy, could not be compared to those with well-controlled HIV infection on effective antiretroviral therapy. Lastly, these studies were designed to investigate outcomes or treatment predictors and had much smaller sample sizes that limit their power to evaluate the LLV frequency.

The main strengths of this study are the large sample size powered to investigate covariates of interest and the wide representation of different geographic regions and genotypes. Regions with high HCV prevalence (Egypt, Georgia) were well represented as well as lower prevalence settings (Cameroon).

There are several limitations to this study. Identified and included patient cohorts were those with available HCV RNA linked with clinical and demographic data and therefore may not be generalizable. We conducted a secondary analysis of data from populations that were tested for HCV for a range of reasons for testing. There were also different methods for data collection at each site. While some data represent a broad sample of tests performed in the general population at a reference laboratory, other data were collected as part of research protocols with strict inclusion and exclusion criteria. There was missing data for several covariates (HIV and HBV co-infection, HCV genotype, fibrosis stage) in 20–52% of the participants. We performed sensitivity analyses including a comparative regression model using imputed data to better characterize bias introduced by missing data and found the introduced bias overall to be limited.

This study investigated the viral load distribution among those with chronic HCV infection from 12 countries in different geographic regions to estimate the requisite clinical sensitivity of a POC test for HCV diagnosis and inform sub-populations that may be at risk for false negative testing. Our findings suggest that a test with an LOD of 1,318 IU/mL, which is about 100 times higher (less sensitive) than the current gold-standard nucleic acid tests, will likely detect 97% of viraemic HCV infections. While an increase in LOD may not impact cost and development of near patient molecular technologies, it sets an achievable LOD for immunoassays such as those that involve HCV core antigen detection. Comparative and cost-effectiveness analyses will be needed to investigate settings that may benefit the most, and to quantify how a less sensitive test might impact the diagnosis, treatment and cure cascade in LMICs. A product specification that allows for an LOD of 1,318 IU/mL could facilitate development of an affordable non-molecular POC test that could dramatically increase rates of HCV testing and treatment initiation in LMICs, thus substantially impacting health outcomes for chronic HCV infection on a population-level.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We wish to acknowledge the following individuals for their contributions to this study:

C. Fortas, Epicentre MSF, Paris, France; F Averhoff and M Nasrullah, Centers for Disease Control, Division of Viral Hepatitis, Atlanta, USA; E Yunihastuti, A Widhani, A Sanityoso, and J Kurniawan, Faculty of Medicine Universitas Indonesia - Dr. Cipto Mangunkusumo General Hospital, Jakarta, Indonesia; A Kamarulzaman, SF Syed Omar, V Pillai, and I Azwa, University Malaya Medical Centre, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia; Kiat Ruxrungtham, A Avihingsanon, Salyavit Chittmittrapap, and P Phanuphak, HIV-NAT/Thai Red Cross AIDS Research Centre, Bangkok, Thailand; NV Trung, NTH Dung, BV Huy and Hoi LT, National Hospital for Tropical Diseases, Hanoi, Vietnam; AH Sohn, JL Ross, N Durier*, and B Petersen, TREAT Asia, amfAR - The Foundation for AIDS Research, Bangkok, Thailand; T Applegate, G Matthews, MG Law, and D Boettiger, The Kirby Institute, UNSW Sydney, Australia.

Funding

The U.S. National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (grant number 1KL2TR001411), and the National Institute on Drug Abuse (grant number P30DA040500) funded this project. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. The WHO contribution was supported through a UNITAID enabling grant. The FIND contribution was also supported by UNITAID, grant 2016–04 FIND. The screening component for the Medecins Sans Frontières study in Mozambique was supported by UNITAID, grant N° SPHQ14-LOA-217. The screening component of the TREAT Asia study, a program of amfAR, The Foundation for AIDS Research was supported by the U.S. National Institutes of Health’s National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, and National Cancer Institute, as part of the International Epidemiology Databases to Evaluate AIDS (IeDEA; U01AI069907), and amfAR. The Kirby Institute is funded by the Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing, and is affiliated with the Faculty of Medicine, UNSW Sydney. The British Columbia Centre for Disease Control is funded by the British Columbia Ministry of Health and is affiliated with the University of British Columbia Faculty of Medicine.

* Current affiliation: Dreamlopments LTD, Bangkok, Thailand

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: none to report

REFERENCES

- [1].World Health Organization. Global Hepatitis Report 2017. 2017. [cited; Available from: http://www.who.int/hepatitis/publications/global-hepatitis-report2017/en/

- [2].Global Tuberculosis Control Report Geneva; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- [3].Gower E, Estes C, Blach S, Razavi-Shearer K, Razavi H. Global epidemiology and genotype distribution of the hepatitis C virus infection. J Hepatol 2014;61:S45–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].World Health Organization. Global Health Sector Strategy on Viral Hepatitis 2016–2021: Towards Ending Hepatitis. 2016. [cited; Available from: http://www.who.int/hepatitis/strategy2016-2021/ghss-hep/en/

- [5].Hill A, Simmons B, Gotham D, Fortunak J. Rapid reductions in prices for generic sofosbuvir and daclatasvir to treat hepatitis C. J Virus Erad 2016;2:28–31. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].World Health Organization. Progress report on access to hepatitis C treatment:Focus on overcoming barriers in low- and middle-income countries. 2018. [cited; Available from: http://www.who.int/hepatitis/publications/hep-c-access-report-2018/en/

- [7].Jauncey M, Micallef JM, Gilmour S, Amin J, White PA, Rawlinson W, et al. Clearance of hepatitis C virus after newly acquired infection in injection drug users. J Infect Dis 2004;190:1270–1274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Mohd Hanafiah K, Groeger J, Flaxman AD, Wiersma ST. Global epidemiology of hepatitis C virus infection: new estimates of age-specific antibody to HCV seroprevalence. Hepatology 2013;57:1333–1342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Easterbrook PJ. Who to test and how to test for chronic hepatitis C infection - 2016 WHO testing guidance for low- and middle-income countries. J Hepatol 2016;65:S46–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].World Health Organization. Guidelines on Hepatitis B and C Testing. 2017. [cited; Available from: http://www.who.int/hepatitis/publications/guidelines-hepatitis-c-b-testing/en/

- [11].World Health Organization. Guidelines on Hepatitis B and C Testing: Policy Brief. 2017. [cited; Available from: http://www.who.int/hepatitis/publications/hepatitis-testing-recommendation-policy/en/

- [12].McGibbon E, Bornschlegel K, Balter S. Half a diagnosis: gap in confirming infection among hepatitis C antibody-positive patients. Am J Med 2013;126:718–722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Ishizaki A, Bouscaillou J, Luhmann N, Liu S, Chua R, Walsh N, et al. Survey of programmatic experiences and challenges in delivery of hepatitis B and C testing in low- and middle-income countries. BMC Infect Dis 2017;17:696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Roberts T, Cohn J, Bonner K, Hargreaves S. Scale-up of Routine Viral Load Testing in Resource-Poor Settings: Current and Future Implementation Challenges. Clin Infect Dis 2016;62:1043–1048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].FIND. Strategy for Hepatitis C, 2015–2020. https://www.finddx.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/HepatitisC_Strategy_WEB.pdf. Access date October 11, 2018.

- [16].Peeling RW, Boeras DI, Marinucci F, Easterbrook P. The future of viral hepatitis testing: innovations in testing technologies and approaches. BMC Infect Dis 2017;17:699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Trianni A, Paneer N, Denkinger C. High-priority target product profile for hepatitis C diagnosis in decentralized settings: Report of a consensus meeting. Vienna, Austria: FIND; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- [18].Ivanova Reipold E, Easterbrook P, Trianni A, Panneer N, Krakower D, Ongarello S, et al. Optimising diagnosis of viraemic hepatitis C infection: the development of a target product profile. BMC Infect Dis 2017;17:707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Maasoumy B, Vermehren J. Diagnostics in hepatitis C: The end of response-guided therapy? J Hepatol 2016;65:S67–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Freiman JM, Tran TM, Schumacher SG, White LF, Ongarello S, Cohn J, et al. Hepatitis C Core Antigen Testing for Diagnosis of Hepatitis C Virus Infection: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med 2016;165:345–355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Llibre A, Shimakawa Y, Mottez E, Ainsworth S, Buivan TP, Firth R, et al. Development and clinical validation of the Genedrive point-of-care test for qualitative detection of hepatitis C virus. Gut 2018;67:2017–2024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Grebely J, Lamoury FMJ, Hajarizadeh B, Mowat Y, Marshall AD, Bajis S, et al. Evaluation of the Xpert HCV Viral Load point-of-care assay from venepuncture-collected and finger-stick capillary whole-blood samples: a cohort study. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Fytili P, Tiemann C, Wang C, Schulz S, Schaffer S, Manns MP, et al. Frequency of very low HCV viremia detected by a highly sensitive HCV-RNA assay. J Clin Virol 2007;39:308–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Peeling RW, Mabey D. Point-of-care tests for diagnosing infections in the developing world. Clin Microbiol Infect 2010;16:1062–1069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Sterling RK, Lissen E, Clumeck N, Sola R, Correa MC, Montaner J, et al. Development of a simple noninvasive index to predict significant fibrosis in patients with HIV/HCV coinfection. Hepatology 2006;43:1317–1325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Vallet-Pichard A, Mallet V, Nalpas B, Verkarre V, Nalpas A, Dhalluin-Venier V, et al. FIB-4: an inexpensive and accurate marker of fibrosis in HCV infection. comparison with liver biopsy and fibrotest. Hepatology 2007;46:32–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Bachofner JA, Valli PV, Kroger A, Bergamin I, Kunzler P, Baserga A, et al. Direct antiviral agent treatment of chronic hepatitis C results in rapid regression of transient elastography and fibrosis markers fibrosis-4 score and aspartate aminotransferase-platelet ratio index. Liver Int 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Sanchez-Conde M, Montes-Ramirez ML, Miralles P, Alvarez JM, Bellon JM, Ramirez M, et al. Comparison of transient elastography and liver biopsy for the assessment of liver fibrosis in HIV/hepatitis C virus-coinfected patients and correlation with noninvasive serum markers J Viral Hepat. England; 2010. p. 280–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Xiao G, Yang J, Yan L. Comparison of diagnostic accuracy of aspartate aminotransferase to platelet ratio index and fibrosis-4 index for detecting liver fibrosis in adult patients with chronic hepatitis B virus infection: a systemic review and meta-analysis. Hepatology 2015;61:292–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Efron B The bootstrap and Markov chain Monte Carlo. J Biopharm Stat 2011;21:1052–1062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Schafer JL. Analysis of Incomplete Multivariate Data. USA: Chapman & Hall; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- [32].Pawlotsky J-M, Negro F, Aghemo A, Berenguer M, Dalgard O, Dusheiko G, et al. EASL Recommendations on Treatment of Hepatitis C 2018. Journal of Hepatology. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Glynn SA, Wright DJ, Kleinman SH, Hirschkorn D, Tu Y, Heldebrant C, et al. Dynamics of viremia in early hepatitis C virus infection. Transfusion 2005;45:994–1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Hajarizadeh B, Grebely J, Applegate T, Matthews GV, Amin J, Petoumenos K, et al. Dynamics of HCV RNA levels during acute hepatitis C virus infection. J Med Virol 2014;86:1722–1729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Ticehurst JR, Hamzeh FM, Thomas DL. Factors affecting serum concentrations of hepatitis C virus (HCV) RNA in HCV genotype 1-infected patients with chronic hepatitis. J Clin Microbiol 2007;45:2426–2433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Duvoux C, Pawlotsky JM, Bastie A, Cherqui D, Soussy CJ, Dhumeaux D. Low HCV replication levels in end-stage hepatitis C virus-related liver disease. J Hepatol 1999;31:593–597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Matthews-Greer JM, Caldito GC, Adley SD, Willis R, Mire AC, Jamison RM, et al. Comparison of hepatitis C viral loads in patients with or without human immunodeficiency virus. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol 2001;8:690–694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Hajarizadeh B, Grady B, Page K, Kim AY, McGovern BH, Cox AL, et al. Factors associated with hepatitis C virus RNA levels in early chronic infection: the InC3 study. J Viral Hepat 2015;22:708–717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Blach S, Zeuzem S, Manns M, Altraif I, Duberg A-S, Muljono DH, et al. Global prevalence and genotype distribution of hepatitis C virus infection in 2015: a modelling study. The Lancet Gastroenterology & Hepatology 2017;2:161–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].World Bank. World Bank List of Economies. 2017. [cited; Available from: https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519-world-bank-country-and-lending-groups [Google Scholar]

- [41].Janjua NZ, Kuo M, Chong M, Yu A, Alvarez M, Cook D, et al. Assessing Hepatitis C Burden and Treatment Effectiveness through the British Columbia Hepatitis Testers Cohort (BC-HTC): Design and Characteristics of Linked and Unlinked Participants. PLoS One 2016;11:e0150176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Gvinjilia L, Nasrullah M, Sergeenko D, Tsertsvadze T, Kamkamidze G, Butsashvili M, et al. National Progress Toward Hepatitis C Elimination — Georgia, 2015–2016. MMWR 2016;65:1132–1135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Mitruka K, Tsertsvadze T, Butsashvili M, Gamkrelidze A, Sabelashvili P, Adamia E, et al. Launch of a Nationwide Hepatitis C Elimination Program--Georgia, April 2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2015;64:753–757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Nasrullah M, Sergeenko D, Gvinjilia L, Gamkrelidze A, Tsertsvadze T, Butsashvili M, et al. The Role of Screening and Treatment in National Progress Toward Hepatitis C Elimination - Georgia, 2015–2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2017;66:773–776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Durier N, Yunihastuti E, Ruxrungtham K, Kinh NV, Kamarulzaman A, Boettiger D, et al. Chronic hepatitis C infection and liver disease in HIV-coinfected patients in Asia. J Viral Hepat 2017;24:187–196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Solomon SS, Mehta SH, Srikrishnan AK, Solomon S, McFall AM, Laeyendecker O, et al. Burden of hepatitis C virus disease and access to hepatitis C virus services in people who inject drugs in India: a cross-sectional study. Lancet Infect Dis 2015;15:36–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Solomon SS, Srikrishnan AK, McFall AM, Kumar MS, Saravanan S, Balakrishnan P, et al. Burden of Liver Disease among Community-Based People Who Inject Drugs (PWID) in Chennai, India. PLoS One 2016;11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Solomon SS, Sulkowski MS, Amrose P, Srikrishnan AK, McFall AM, Ramasamy B, et al. Directly observed therapy of sofosbuvir/ribavirin +/− peginterferon with minimal monitoring for the treatment of chronic hepatitis C in people with a history of drug use in Chennai, India (C-DOT). J Viral Hepat 2018;25:37–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Mehta SH, Vogt SL, Srikrishnan AK, Vasudevan CK, Murugavel KG, Saravanan S, et al. Epidemiology of hepatitis C virus infection & liver disease among injection drug users (IDUs) in Chennai, India. Indian J Med Res 2010;132:706–714. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.