Abstract

Objective:

Adiponectin is a fat-derived hormone that secretes exclusively by adipocytes and has antiatherosclerotic effects. Peripheral arterial occlusive disease (PAOD) is associated with an increased risk of death in hemodialysis (HD) patients. The aim of this study was to evaluate the relationship between serum adiponectin levels and PAOD by ankle–brachial index (ABI) in HD patients.

Materials and Methods:

Blood samples were obtained from 100 HD patients. Serum adiponectin levels were measured using a commercial enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kit. ABI values were measured using the automated oscillometric method (VaSera VS-1000). ABI values that <0.9 were included in the low ABI group.

Results:

Among the 100 HD patients, 18 of them (18.0%) were in the low ABI group. Compared with patients in the normal ABI group, the patients in the low ABI group had a higher prevalence of diabetes (P = 0.043), older age (P = 0.027), and lower serum adiponectin level (P = 0.003). In addition, the multivariable logistic regression analysis showed that adiponectin (Odds ratio [OR]: 0.927, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.867–0.990, P = 0.025) and age (OR: 1.054, 95% CI: 1.002–1.109, P = 0.043) were the independently associated with PAOD in HD patients.

Conclusion:

In this study, serum adiponectin level was found to be associated with PAOD in HD patients.

KEYWORDS: Adiponectin, Ankle–brachial index, Hemodialysis, Peripheral artery occlusive disease

INTRODUCTION

Peripheral arterial occlusive disease (PAOD) is a common systemic vascular problem, which is mainly caused by atherosclerosis [1]. Patients with PAOD have either partial or total obstruction of proximal or distal arteries of the lower extremities [2]. The signs and symptoms of PAOD are variable; many patients present with the classic symptom of claudication [3]. PAOD is a strong predictor for all-cause mortality and is associated with increased cardiovascular mortality in hemodialysis (HD) patients; therefore, it is important to diagnose and treat PAOD in such patients as early as possible [4,5,6,7]. Although the golden diagnostic tool for PAOD is angiography, it is rarely used for follow-up of progression of the disease due to its invasiveness. On the other hand, ankle–brachial index (ABI) is a noninvasive diagnostic test, which can be used for subsequent monitoring of PAOD. ABI is a reliable test with 95% sensitivity in the diagnosis of PAOD when the result is <0.9 [8].

Adiponectin is a kind of adipokines that is a 244 amino acid and 30-kDa protein and is known to have antiatherogenic, anti-inflammatory, and insulin-sensitizing effects [9,10]. Patients with obesity, metabolic syndrome, and diabetes mellitus (DM) were found to have lower serum adiponectin levels [11]. Serum adiponectin level is negatively associated to estimate glomerular filtration rate where a higher level of adiponectin is noted in patients with end-stage renal disease (ESRD) [12]. Lower serum adiponectin level is a predictor of poorer cardiovascular disease (CVD) outcomes in chronic kidney disease (CKD) patients [13]. Since CVD is the main cause of mortality among CKD and ESRD patients, it is important to investigate the correlation of adiponectin in this special population [14]. Adiponectin is found to have antiatherogenic effects and is helpful in the prevention of atherosclerotic vascular diseases [15]. One study demonstrated a significant negative correlation between serum adiponectin levels and CVD among HD patients [16]. In addition, another study in 2016 found that lower serum adiponectin levels were associated with higher prevalence of PAOD in HD patients without DM [17]. In addition, Lim et al. found that serum adiponectin seems inversely associated with PAOD in HD patients [18]. This study aims to examine the correlation between serum adiponectin levels and diagnosis of PAOD among HD patients.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients

Patients older than 20 years of age, receiving standard 4-h dialysis three times per week, using standard bicarbonate dialysate and had been on dialysis for at least 6 months from our HD program were invited to participate in our study. The study was conducted from March 2015 to July 2015 at a medical center in Hualien, Taiwan. A total of 141 participants were enrolled and participants were excluded if they had any acute infection (n = 5), heart failure (n = 1), malignancy (n = 6), taking cilostazol or pentoxifylline during blood sampling period (n = 3), or if they refused to sign consent form for the study (n = 26). Finally, a total of 100 HD patients were recruited for our study. The study was approved by the Protection of Human Subjects Institutional Review Board of Tzu Chi University and Hospital (IRB103-136-A). Hypertension was diagnosed if patients' systolic blood pressure was ≥140 mmHg and/or diastolic blood pressure was ≥90 mmHg or if they have received any antihypertensive medication in the previous 2 weeks. Type 2 DM was diagnosed if a patient's fasting plasma glucose was ≥126 mg/dL or if they were using anti-diabetic therapy [19]. The Kt/V and urea reduction ratio were measured before dialysis and immediately after dialysis using a formal, single-compartment dialysis urea kinetic model.

Anthropometric analysis

Body weight was measured to the nearest half-kilogram with the patient in light clothing and without shoes before and after HD. Height was measured to the nearest half-centimeter after HD. Waist circumference was measured to the nearest half-centimeter at the shortest point below the lower rib margin and the iliac crest after HD. Body mass index was defined as the post-HD body weight (kilograms) divided by height squared (meters). The standard tetrapolar whole body (hand-foot) technique was used for bioimpedance measurements of body fat mass by using a single-frequency (50-kHz) analyzer (Biodynamic-450, Biodynamics Corporation, Seattle, USA) after HD by the same operator [20,21].

Biochemical determinations

Blood samples of approximately 5 mL were taken before the start of HD and were immediately centrifuged at 3000 g for 10 min after collection. Serum samples were stored at 4°C and used for biochemical analyses within 1 h of collection. Serum levels of blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, glucose, total cholesterol, triglyceride, albumin, globulin, total calcium, and phosphorus were measured using an autoanalyzer (Siemens Advia 1800, Siemens Healthcare GmbH, Henkestr, Germany). Serum adiponectin levels (SPI-BIO, Montigny le Bretonneux, France) and intact parathyroid hormone (iPTH) (Diagnostic Systems Laboratories, Webster, Texas, USA) were measured using a commercial enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kit [20].

Ankle-brachial index measurements

The ABI values were measured using an ABI-form device (VaSera VS-1000, Fukuda Denshi Co, Ltd, Tokyo, Japan) that automatically and simultaneously measures BP in both arms and ankles of patients using an oscillometric method [21,22]. ABI was calculated as the ratio of the ankle SBP divided by the arm SBP, and the lower value of the ankle SBP was used for the calculation. Monitoring cuffs were placed around four extremities. Patients' electrocardiograms and heart sounds were recorded when they were at rest and in the supine position for at least 10 min. These parameters were measured repetitively over patients' both legs and the means were calculated. PAOD was diagnosed when ABI was <0.9 [23]. In this study, ABI values <0.9 were used to define the low ABI group [21,22].

Statistical analysis

Data were tested for normal distribution using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Data were expressed as means ± standard deviation for normally distributed data and as medians and interquartile ranges for nonnormal distributed data. Student's independent t-test (two-tailed) was used to compare parameters with normal distribution and the Mann–Whitney U-test was used for nonnormal distributed data. The serum glucose, triglyceride, and iPTH datasets showed skewed nonnormal distributions initially and became normally distributed after recalculation by transformation to the logarithm to the base 10. Chi-square test was used to analyze the data expressed as the number of patients. Variables that were significantly associated with PAOD in HD patients were evaluated for independence by multivariable logistic regression analysis. Receiver operating curve (ROC) was used to calculate the area under the curve (AUC) to identify the value of adiponectin to predict PAOD in HD patients. All statistical analyses employed SPSS for Windows (version 19.0; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

The anthropometric, biochemical data, comorbidity, and drugs used of all HD participants are shown in Table 1. The mean age of the 100 HD patients was 64.8 years, and they had received HD for 83.9 months. Among 100 HD recipients, 18 patients (18.0%) were in the low ABI group. Compared with patients in the normal ABI group, the patients in the low ABI group had older age (P = 0.027) and lower serum adiponectin level (P = 0.003). Compared with patients in the normal ABI group, the patients in the low ABI group had a higher prevalence of diabetes (P = 0.043). There was no statistically significant difference in sex, comorbid conditions with hypertension, or usage of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin-receptor blockers, β-blockers, calcium-channel blockers, fibrates, or statins.

Table 1.

Clinical variables of the 100 hemodialysis patients with normal or low ankle brachial index group

| Characteristics | All patients (n=100) | Normal ABI group (n=82) | Low ABI group (n=18) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 64.80±13.66 | 63.39±14.03 | 71.22±9.79 | 0.027* |

| HD duration (months) | 83.93±68.31 | 82.83±68.34 | 88.93±69.89 | 0.733 |

| Height (cm) | 157.65±8.65 | 157.41±9.01 | 158.72±7.02 | 0.565 |

| Pre-HD body weight (kg) | 59.60±13.36 | 58.49±13.10 | 64.63±13.79 | 0.078 |

| Post-HD body weight (kg) | 57.47±13.03 | 56.34±12.73 | 62.62±13.51 | 0.064 |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 88.49±12.21 | 87.48±11.91 | 93.11±12.82 | 0.076 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 23.08±4.80 | 22.68±4.60 | 24.92±5.37 | 0.073 |

| Body fat mass (%) | 26.82±7.64 | 26.44±7.49 | 28.57±8.28 | 0.286 |

| Left-ABI | 1.04±0.19 | 1.11±0.15 | 0.77±0.12 | <0.001* |

| Right-ABI | 1.02±0.16 | 1.06±0.13 | 0.86±0.19 | <0.001* |

| SBP (mmHg) | 143.32±26.54 | 144.47±27.23 | 138.06±23.04 | 0.355 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 77.29±17.22 | 77.84±17.63 | 74.78±15.39 | 0.497 |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dL) | 143.84±32.70 | 147.18±34.15 | 133.17±22.87 | 0.127 |

| Triglyceride (mg/dL) | 109.50 (75.75-173.25) | 107.00 (72.50-169.75) | 116.00 (94.50-180.50) | 0.412 |

| Glucose (mg/dL) | 128.50 (107.75-160.75) | 128.50 (110.00-151.00) | 129.00 (104.00-233.50) | 0.612 |

| Albumin (mg/dL) | 4.12±0.47 | 4.16±0.50 | 3.94±0.26 | 0.068 |

| Globulin (mg/dL) | 3.17±0.60 | 3.20±0.63 | 3.04±0.46 | 0.334 |

| Blood urea nitrogen (mg/dL) | 62.65±14.93 | 63.57±14.60 | 58.44±16.08 | 0.188 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 9.02±2.01 | 9.19±2.14 | 8.27±1.03 | 0.079 |

| Total calcium (mg/dL) | 8.98±0.74 | 8.98±0.77 | 8.99±0.59 | 0.939 |

| Phosphorus (mg/dL) | 4.70±1.28 | 4.69±1.31 | 4.74±1.17 | 0.884 |

| iPTH (pg/mL) | 195.90 (57.28-373.78) | 227.25 (66.78-497.13) | 152.45 (28.90-219.70) | 0.060 |

| Adiponectin (µg/mL) | 45.79±10.41 | 47.20±9.45 | 39.36±12.35 | 0.003* |

| Urea reduction rate | 0.74±0.04 | 0.74±0.04 | 0.73±0.04 | 0.196 |

| Kt/V (Gotch) | 1.36±0.17 | 1.37±0.17 | 1.32±0.16 | 0.203 |

| Female, n (%) | 55 (55.0) | 47 (57.3) | 8 (44.4) | 0.320 |

| DM, n (%) | 35 (35.0) | 25 (30.5) | 10 (55.6) | 0.043* |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 52 (52.0) | 44 (53.7) | 8 (44.4) | 0.479 |

| Current smoking | 11 (11.0) | 8 (9.8) | 3 (16.7) | 0.396 |

| ACE inhibitor or ARB use, n (%) | 25 (25.0) | 22 (26.8) | 3 (16.7) | 0.367 |

| β-blocker, n (%) | 29 (29.0) | 26 (31.7) | 3 (16.7) | 0.203 |

| CCB, n (%) | 39 (39.0) | 34 (41.5) | 5 (27.8) | 0.281 |

| Statin, n (%) | 18 (18.0) | 14 (17.1) | 4 (22.2) | 0.607 |

| Fibrate, n (%) | 12 (12.0) | 9 (11.0) | 3 (16.7) | 0.501 |

*P<0.05 was considered statistically significant. Values for continuous variables given as means±SD and test by student’s t-test, variables not normally distributed given as medians and interquartile range and test by Mann-Whitney U-test, Data are expressed as number of patients and analysis was done using the Chi-square test. ABI: Ankle brachial indices, HD: Hemodialysis, Kt/V: Fractional clearance index for urea, ACE: Angiotensin-converting enzyme, ARB: Angiotensin-receptor blocker, CCB: Calcium-channel blocker, SD: Standard deviation, BMI: Body mass index, SBP: Systolic blood pressure, iPTH: Intact parathyroid hormone, DM: Diabetes mellitus

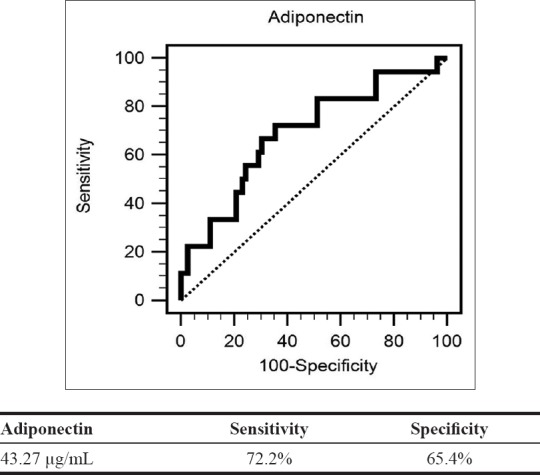

The multivariable logistic regression analysis revealed that the serum adiponectin has significant statistic negative correlation with PAOD in HD patients (Odds ratio [OR]: 0.927, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.867–0.990, P = 0.025). Age was also found to be positively associated with these patients (OR: 1.054, 95% CI: 1.002–1.109, P = 0.043) [Table 2]. A ROC curve for PAOD prediction was plotted to verify the optimum cutoff for adiponectin, which was 43.27 μg/mL. The AUC for adiponectin was 0.691 (95% CI: 0.591–0.780, P = 0.008), with a sensitivity and specificity of 72.2%, 65.4%, respectively [Figure 1].

Table 2.

Multivariable logistic regression analysis of the factors correlated to peripheral arterial occlusive disease among 100 hemodialysis patients

| Variables | OR | 95% CI | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adiponectin, 1 (µg/mL) | 0.927 | 0.867-0.990 | 0.025* |

| Age, 1 (year) | 1.054 | 1.002-1.109 | 0.043* |

| DM (present) | 2.103 | 0.666-6.660 | 0.205 |

*P<0.05 was considered statistically significant. Analysis data were done using the multivariable logistic regression analysis (adopted factors: Age, diabetes, and adiponectin). OR: Odds ratio, CI: Confidence interval, DM: Diabetes mellitus

Figure 1.

Receiver operating characteristic curve analysis to predict peripheral arterial occlusive disease in hemodialysis patients. The area under the curve receiver operating characteristic indicates the diagnostic power of adiponectin at predicting peripheral arterial occlusive disease in hemodialysis patients. The area under the curve for adiponectin was 0.691 (95% confidence interval: 0.591–0.780, P = 0.008)

DISCUSSION

The main observations of our study revealed that HD patients in the PAOD group had lower serum adiponectin level, higher prevalence of DM and older age. In addition, serum adiponectin and age were independently associated with PAOD in HD patients.

The prevalence of PAOD increases sharply with age, with about 20% of those afflicted >60 years of age, increasing to nearly 50% in those aged ≥85 years [24]. Aging is associated with functional, structural, and mechanical changes in arteries, which is an important condition leading to CVD [25]. Our finding also showed age is a positive predictor of PAOD in HD patients. Increase in traditional cardiovascular risk factors, such as DM is also an important determinant of PAOD in all countries [1,2,3,24]. During 11 years' follow-up, 16% of patients were diagnosed PAOD at baseline and 24% developed new PAOD in Type 2 DM [26]. Type 2 DM in PAOD patients accelerates atherothrombotic disease and strongly increases the incidence of cardiovascular events than those with neither PAOD nor Type 2 DM, or Type 2 DM only, or those with PAOD only [27]. In our study, it revealed that HD patients with DM were significantly more in PAOD than the normal ABI group.

The anti-inflammatory, antiatherogenic, and insulin-sensitizing effects of adiponectin were shown to be protective in patients with metabolic syndrome [28,29,30]. The mechanism of vascular remodeling of adiponectin may be explained by it is property to inhibit crucial steps in the development of atherosclerosis; it includes (1) inhibiting the expression of scavenger receptor A1 of macrophages, further attenuating foam cell formation and ameliorating oxidized low-density lipoprotein uptake [31], (2) inhibiting expression of adhesion molecules, such as intracellular adhesion molecule-1, vascular cellular adhesion moleculae-1 and E-selectin [9,31], (3) inhibiting proliferation and migration of smooth muscle cells [32], and (4) diminishing platelet aggregation and thrombus formation [33]. Therefore, in patients with low serum adiponectin levels, they are more prone to pathological inflammatory responses due to weakening protective effect against the atherosclerotic changes [28]. Our finding showed a reverse correlation of plasma adiponectin with PAOD in HD patients after multivariable logistic regression analysis. The results of our study were consistent with previous two studies from Zhou et al. and Lim et al. [17,18]. Both studies revealed that lower serum adiponectin was found in the HD patients with PAOD compared to those without PAOD. The participants in the Zhou et al. study excluded patients with DM [17]. Our study is the same as Lim et al. those HD patients including with DM [18]. Furthermore, the serum adiponectin level was also independently associated with PAOD in HD patients with DM. However, if the HD patients without DM in our study, we did not find the statistically significant associated between serum adiponectin and PAOD. Further studies are needed to investigate the relationship between PAOD and adiponectin levels in HD patients without DM.

The limitation of our study is a small population of patients with PAOD, as a cross-sectional study, and these patients were from a single center. Another limitation is that use of the ABI test to diagnose PAOD may affect by patient's height [34]. The other limitation is ABI could not completely represent of PAOD in HD patients because of high prevalence of medial artery calcification in these patients [35]. Moreover, occlusive disease distal to the ankle is not detected by the ABI test. In addition, other established risk factors for PAOD such as smoking, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia were not shown a correlation in this study. Therefore, further multicentered, prospective, cohort study should be conducted to confirm the causal-effective relationship between serum adiponectin and PAOD in HD patients.

CONCLUSION

Low serum adiponectin levels are a risk factor for PAOD in HD patients. Further long-term prospective studies are needed to elucidate the causal relationship between serum adiponectin and PAOD in HD patients.

Financial support and sponsorship

This study was supported by a grant from the Ministry of Science and Technology, Taiwan (MOST-104-2314-B-303-010).

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Patel MR, Conte MS, Cutlip DE, Dib N, Geraghty P, Gray W, et al. Evaluation and treatment of patients with lower extremity peripheral artery disease: Consensus definitions from Peripheral Academic Research Consortium (PARC) J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;65:931–41. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.12.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.European Stroke Organisation, Tendera M, Aboyans V, Bartelink ML, Baumgartner I, Clément D, et al. ESC guidelines on the diagnosis and treatment of peripheral artery diseases: Document covering atherosclerotic disease of extracranial carotid and vertebral, mesenteric, renal, upper and lower extremity arteries: The Task Force on the Diagnosis and Treatment of Peripheral Artery Diseases of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Eur Heart J. 2011;32:2851–906. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehr211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gerhard-Herman MD, Gornik HL, Barrett C, Barshes NR, Corriere MA, Drachman DE, et al. 2016 AHA/ACC guideline on the management of patients with lower extremity peripheral artery disease: Executive summary: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association task force on clinical practice guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;69:1465–508. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yang Y, Ning Y, Shang W, Luo R, Li L, Guo S, et al. Association of peripheral arterial disease with all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in hemodialysis patients: A meta-analysis. BMC Nephrol. 2016;17:195. doi: 10.1186/s12882-016-0397-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dua A, Lee CJ. Epidemiology of peripheral arterial disease and critical limb ischemia. Tech Vasc Interv Radiol. 2016;19:91–5. doi: 10.1053/j.tvir.2016.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Otsubo S, Kitamura M, Wakaume T, Yajima A, Ishihara M, Takasaki M, et al. Association of peripheral artery disease and long-term mortality in hemodialysis patients. Int Urol Nephrol. 2012;44:569–73. doi: 10.1007/s11255-010-9883-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Al Thani H, El-Menyar A, Hussein A, Sadek A, Sharaf A, Singh R, et al. Prevalence, predictors, and impact of peripheral arterial disease in hemodialysis patients: A cohort study with a 3-year follow-up. Angiology. 2013;64:98–104. doi: 10.1177/0003319711436078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hiatt WR. Medical treatment of peripheral arterial disease and claudication. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:1608–21. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200105243442108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ouchi N, Kihara S, Arita Y, Maeda K, Kuriyama H, Okamoto Y, et al. Novel modulator for endothelial adhesion molecules: Adipocyte-derived plasma protein adiponectin. Circulation. 1999;100:2473–6. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.100.25.2473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Trimarchi H, Muryan A, Dicugno M, Forrester M, Lombi F, Young P, et al. In hemodialysis, adiponectin, and pro-brain natriuretic peptide levels may be subjected to variations in body mass index. Hemodial Int. 2011;15:477–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1542-4758.2011.00562.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kadowaki T, Yamauchi T, Kubota N, Hara K, Ueki K, Tobe K, et al. Adiponectin and adiponectin receptors in insulin resistance, diabetes, and the metabolic syndrome. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:1784–92. doi: 10.1172/JCI29126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Martinez Cantarin MP, Waldman SA, Doria C, Frank AM, Maley WR, Ramirez CB, et al. The adipose tissue production of adiponectin is increased in end-stage renal disease. Kidney Int. 2013;83:487–94. doi: 10.1038/ki.2012.421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zoccali C, Mallamaci F, Tripepi G, Benedetto FA, Cutrupi S, Parlongo S, et al. Adiponectin, metabolic risk factors, and cardiovascular events among patients with end-stage renal disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2002;13:134–41. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V131134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Collins AJ, Foley RN, Chavers B, Gilbertson D, Herzog C, Johansen K, et al. 'United states renal data system 2011 annual data report: Atlas of chronic kidney disease & end-stage renal disease in the United States. Am J Kidney Dis. 2012;59:A7, e1–420. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2011.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Iwashima Y, Horio T, Suzuki Y, Kihara S, Rakugi H, Kangawa K, et al. Adiponectin and inflammatory markers in peripheral arterial occlusive disease. Atherosclerosis. 2006;188:384–90. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2005.10.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.El-Shafey EM, Shalan M. Plasma adiponectin levels for prediction of cardiovascular risk among hemodialysis patients. Ther Apher Dial. 2014;18:185–92. doi: 10.1111/1744-9987.12065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhou Y, Zhang J, Zhang W, Ni Z. Association of adiponectin with peripheral arterial disease and mortality in nondiabetic hemodialysis patients: Long-term follow-up data of 7 years. J Res Med Sci. 2016;21:50. doi: 10.4103/1735-1995.184000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lim PS, Hu CY, Wu MY, Wu TK, Chang HC. Plasma adiponectin is associated with ankle-brachial index in patients on haemodialysis. Nephrology (Carlton) 2007;12:546–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1797.2007.00839.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alberti KG, Zimmet PZ. Definition, diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus and its complications. Part 1: Diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus provisional report of a WHO consultation. Diabet Med. 1998;15:539–53. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9136(199807)15:7<539::AID-DIA668>3.0.CO;2-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hou JS, Wang CH, Lai YH, Lin YL, Kuo CH, Subeq YM, et al. Negative correlation of serum adiponectin levels with carotid-femoral pulse wave velocity in patients treated with hemodialysis. Biol Res Nurs. 2018;20:462–8. doi: 10.1177/1099800418768887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lai YH, Wang CH, Tsai JP, Hou JS, Lee CJ, Hsu BG, et al. High serum leptin level is associated with peripheral artery disease in adult peritoneal dialysis patients. Ci Ji Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2018;30:85–9. doi: 10.4103/tcmj.tcmj_8_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hsu BG, Lee CJ, Yang CF, Chen YC, Wang JH. High serum resistin levels are associated with peripheral artery disease in the hypertensive patients. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2017;17:80. doi: 10.1186/s12872-017-0517-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ferreira AC, Macedo FY. A review of simple, non-invasive means of assessing peripheral arterial disease and implications for medical management. Ann Med. 2010;42:139–50. doi: 10.3109/07853890903521070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sigvant B, Lundin F, Wahlberg E. The risk of disease progression in peripheral arterial disease is higher than expected: A meta-analysis of mortality and disease progression in peripheral arterial disease. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2016;51:395–403. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2015.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rubio-Ruiz ME, Pérez-Torres I, Soto ME, Pastelín G, Guarner-Lans V. Aging in blood vessels. Medicinal agents FOR systemic arterial hypertension in the elderly. Ageing Res Rev. 2014;18:132–47. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2014.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kallio M, Forsblom C, Groop PH, Groop L, Lepäntalo M. Development of new peripheral arterial occlusive disease in patients with type 2 diabetes during a mean follow-up of 11 years. Diabetes Care. 2003;26:1241–5. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.4.1241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Saely CH, Schindewolf M, Zanolin D, Heinzle CF, Vonbank A, Silbernagel G, et al. Single and combined effects of peripheral artery disease and of type 2 diabetes mellitus on the risk of cardiovascular events: A prospective cohort study. Atherosclerosis. 2018;279:32–7. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2018.09.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Arita Y, Kihara S, Ouchi N, Takahashi M, Maeda K, Miyagawa J, et al. Paradoxical decrease of an adipose-specific protein, adiponectin, in obesity. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1999;257:79–83. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.0255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Matsuzawa Y, Funahashi T, Nakamura T. Molecular mechanism of metabolic syndrome X: Contribution of adipocytokines adipocyte-derived bioactive substances. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1999;892:146–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb07793.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Weyer C, Funahashi T, Tanaka S, Hotta K, Matsuzawa Y, Pratley RE, et al. Hypoadiponectinemia in obesity and type 2 diabetes: Close association with insulin resistance and hyperinsulinemia. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86:1930–5. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.5.7463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ouchi N, Kihara S, Arita Y, Nishida M, Matsuyama A, Okamoto Y, et al. Adipocyte-derived plasma protein, adiponectin, suppresses lipid accumulation and class A scavenger receptor expression in human monocyte-derived macrophages. Circulation. 2001;103:1057–63. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.8.1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Arita Y, Kihara S, Ouchi N, Maeda K, Kuriyama H, Okamoto Y, et al. Adipocyte-derived plasma protein adiponectin acts as a platelet-derived growth factor-BB-binding protein and regulates growth factor-induced common postreceptor signal in vascular smooth muscle cell. Circulation. 2002;105:2893–8. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000018622.84402.ff. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Adamczak M, Wiecek A. The adipose tissue as an endocrine organ. Semin Nephrol. 2013;33:2–13. doi: 10.1016/j.semnephrol.2012.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Criqui MH, Aboyans V. Epidemiology of peripheral artery disease. Circ Res. 2015;116:1509–26. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.303849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Floege J, Ketteler M. Vascular calcification in patients with end-stage renal disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2004;19(Suppl 5):V59–66. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfh1058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]