Unmet Needs for Therapeutic Innovation

Diabetes is a global health emergency with 425 million people affected in the year 2017 and a projection for 629 million by 2045. Half develop diabetic kidney disease, and its prevalence is rising progressively in concert with the overall diabetes epidemic, largely driven by type 2 diabetes (1). In addition to being the most common cause of ESKD worldwide, diabetic kidney disease greatly amplifies risks of cardiovascular complications and death. Even with treatment of the major risk factors, hyperglycemia and hypertension, diabetic kidney disease risks remain high. Intensive glycemic control does not reduce cardiovascular risks and has only a modest effect on diabetic kidney disease in established type 2 diabetes. Therefore, human suffering and societal costs of diabetic kidney disease are enormous and the unmet need for therapeutic innovation is urgent.

Until the advent of the sodium glucose cotransporter (SGLT2) inhibitor class of antihyperglycemic agents, the last major advance in treatment for diabetic kidney disease was reported almost 20 years ago when angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) compared with placebo were found to reduce risk of serum creatinine doubling or ESKD by nearly 20% mostly independent of hypertension control (2,3). Notably, risks of cardiovascular disease and death were not reduced in the ARB trials. Many subsequent studies of interventions including dual agent renin-angiotensin system blockade, bardoxolone, protein kinase C-β inhibition, erythrocyte stimulating agents, and antifibrotic and anti-inflammatory therapies failed to generate treatment advances because of adverse safety signals, lack of efficacy, or business and regulatory decisions (1). In the meantime, a robust armamentarium for cardiovascular disease was developed and implemented. Risks of myocardial infarction and stroke were cut by more than half in people with diabetes during the past two decades, whereas risk of ESKD was essentially a zero-sum game. This dearth of therapies contributed to lack of progress, a particular concern because patients with type 2 diabetes who survive cardiovascular events remain at high risk for ESKD.

Lessons Learned from Clinical Trials

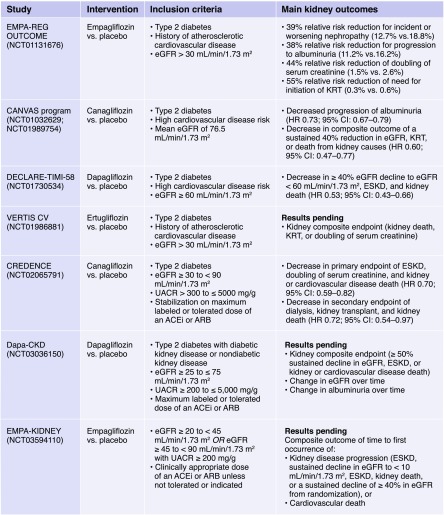

Over the past decade, the US Food and Drug Administration has mandated postmarket approval cardiovascular safety trials of antihyperglycemic agents, including SGLT2 inhibitors (see Box 1). The first reported such trial for SGLT2 inhibitors, the Empagliflozin Cardiovascular Outcome Event Trial in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Patients (EMPA-REG OUTCOME), enrolled patients with type 2 diabetes and established cardiovascular disease (n=7020) (4). Approximately 30% had CKD at baseline. Unpredictably at the time, empagliflozin reduced risks of three-point major adverse cardiovascular events (myocardial infarction, stroke, and cardiovascular death [MACE]), cardiovascular and all-cause mortality, and hospitalization for heart failure, along with a 39% reduction in the secondary kidney disease outcome (albuminuria progression, serum creatinine doubling, ESKD, death). The second reported cardiovascular safety trial, the Canagliflozin Cardiovascular Assessment Study (CANVAS), was performed in >10,000 participants, of whom approximately two thirds had established cardiovascular disease (5). The CANVAS trial reported similar decreases in three-point MACE and hospitalization for heart failure along with reduction in risk of 40% eGFR decline, ESKD, or death due to kidney disease. More recently, the Multicenter Trial to Evaluate the Effect of Dapagliflozin on the Incidence of Cardiovascular Events (DECLARE TIMI-58), which included patients with the lowest overall cardiovascular risk profile (approximately 40% established cardiovascular disease), reported that the coprimary outcome of cardiovascular death or hospitalization for heart failure was significantly reduced (6). Furthermore, the composite of doubling of serum creatinine, ESKD or death due to kidney disease was virtually halved.

Box 1.

ACEi, angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB, angiotensin II receptor blocker; CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; UACR, urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio.

The Evaluation of the Effects of Canagliflozin on Renal and Cardiovascular Outcomes in Participants with Diabetic Nephropathy (CREDENCE) trial was the first to test an SGLT2 inhibitor for efficacy and safety in participants with type 2 diabetes selected specifically for CKD (7). They comprised 4401 patients with eGFR 30–90 (mean baseline 56) ml/min per 1.73 m2 and severely elevated albuminuria (urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio >300 mg/g). CREDENCE was designed to determine kidney protective effects on a background of standard of care (angiotensin converting enzyme [ACE] inhibitor or ARB). Canagliflozin reduced the primary outcome of ESKD, serum creatinine doubling, or death from kidney or cardiovascular causes by 30%. These risks were meaningfully diminished such that the number needed to treat to prevent ESKD, serum creatinine doubling, or kidney disease death was 28 and for ESKD alone was 43. Additionally, three-point MACE and hospitalization for heart failure were also significantly decreased. In sum, the CREDENCE trial demonstrated substantial kidney and cardiovascular protection in patients with diabetic kidney disease on top of standard of care.

Convening Clinical Transformation

A transformative advance, as heralded by CREDENCE, requires implementation by an entire community of clinicians who care for patients with type 2 diabetes. Focused effort is necessary to increase awareness, detection, and intervention for diabetic kidney disease. We strongly encourage SGLT2 inhibitor therapy for these patients. The American Diabetes Association has recently updated the Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes for use of an SGLT2 inhibitor according to the inclusion criteria from CREDENCE to reduce risk of CKD progression, cardiovascular events, or both (class A recommendation) (8). Clinicians have a responsibility to identify SGLT2 inhibitor candidates and to safely and effectively deploy these agents. For a historical context on barriers to dissemination and implementation, it is instructive to review the evolution of ACE inhibitor and ARB use for treatment of diabetic kidney disease. Long after positive results from the original clinical trials in type 2 diabetes were released, clinical adoption remains low, at least in part because of concern about adverse effects, particularly hyperkalemia and initial decrease in eGFR. Nevertheless, with knowledge and experience, these side effects can usually be avoided or managed. A large number of patients who are candidates for ACE inhibitors and ARBs still do not receive them. Whether this is driven by excessive caution, lack of knowledge, or process failure is unclear. SGLT2 inhibitors have been associated with noteworthy adverse effects. Higher risks of genital mycotic infections and ketoacidosis warrant monitoring and caution. However, rates of previously reported adverse events with canagliflozin (lower extremity amputation, bone fracture) did not differ between active treatment and placebo groups in CREDENCE (7). For safe usage, patient education and engagement are central, including “sick-day” management during acute illness and other stressors when SGLT2 inhibitors, ACE inhibitors and ARBs, and other relevant medications ought to be temporarily stopped.

A vital therapeutic goal for patients with diabetic kidney disease is control of hyperglycemia while avoiding hypoglycemia. In clinical practice, SGLT2 inhibition exerts only modest glycemic lowering and is therefore currently used as an add-on therapy, usually to metformin. In patients with CKD, antihyperglycemic options are limited because of risks of hypoglycemia or adverse side effect profiles for many oral agents and insulin. Although SGLT2 inhibitors have nominal glycemic efficacy at lower eGFR levels, combination treatment with an incretin mimetic, the dipeptidyl peptidase 4 inhibitor saxagliptin, was recently shown to improve glycemic control without promoting hypoglycemia. Another incretin class, the glucagon like peptide-1 agonists, more potently lower blood glucose without promoting hypoglycemia. Moreover, dulaglutide and liraglutide prevent albuminuria onset and progression as well as eGFR decline, particularly in patients with eGFR <60 ml/min per 1.73 m2 (9,10). Future research should therefore address when, and if, combinations of incretin mimetics and SGLT2 inhibitors may be applied for hyperglycemic management and kidney protection. At the same time CREDENCE was released, the Study Of Diabetic Nephropathy with Atrasentan in patients with type 2 diabetes and CKD reported that atrasentan reduced risk of serum creatinine doubling, ESKD, or death from kidney failure by 35% in responders and 28% in a combined population of responders and nonresponders (on the basis of albuminuria lowering). For diabetic and nondiabetic CKD alike, this emerging menu of therapeutic agents mitigates multiple direct (glomerular hyperfiltration, cellular injury via inflammation and oxidative stress, sodium retention) and indirect (hyperglycemia, hypertension, and obesity) mechanisms of kidney damage. Whether nondiabetic patients with CKD thought to share biologic mechanisms (e.g., hypertension, obesity) will receive similar benefit is an important area of research. For SGLT2 inhibitors, the DAPA-CKD and EMPA-KIDNEY trials (see Box 1) are recruiting participants with and without diabetes to define whether non-glycemic effects of these agents reduce risks of clinical end points in patients with diverse CKD etiologies.

It is time to spread the word that new therapies for diabetic kidney disease have arrived. With accumulated evidence in >40,000 patients who have participated in the EMPA-REG, CANVAS, DECLARE TIMI-58, and CREDENCE trials, this is an opportune moment to move forward with SGLT2 inhibitors (4–7). As in the clinical trials, it is also critical to deliver the standard-of-care, an ACE inhibitor or an ARB, as background therapy. Given the remarkable reduction in risks of heart failure and ESKD, SGLT2 inhibition is expected to be quite cost-effective, another important topic for ongoing research. Therefore, the “ask” of payers and drug makers is to make these agents available and affordable. Facilitators to delivering the right treatment to the right patient at the right time must be prioritized. The present challenge is to assure that breakthrough benefits of SGLT2 inhibitors are safely provided to a steadily growing population of patients with diabetic kidney disease who may benefit.

Disclosures

Dr. Cherney reports receiving grants of research support and personal fees for honoraria from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly and Company, Janssen, Merck, and Sanofi and personal fees for honoraria from AbbVie, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Mitsubishi-Tanabe, and Prometic, outside of the submitted work. Dr. Tuttle reports consulting fees from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly and Company, Gilead, and Goldfinch Bio; travel support from Boehringer Ingelheim and Eli Lilly and Company; and speaker fees from Eli Lilly and Company, outside of the submitted work.

Acknowledgments

The Diabetic Kidney Disease Task Force of the American Society of Nephrology is composed of Susan Quaggin, Raymond Harris, Frank Brosius, Alan Kliger, David Cherney, Katherine Tuttle, Tod Ibrahim, Meaghan Allain, Susan Stark, and David White. All contributed to the concepts, development, and editing of this article.

The content of this article does not reflect the views or opinions of the American Society of Nephrology (ASN) or CJASN. Responsibility for the information and views expressed therein lies entirely with the author(s).

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

References

- 1.Alicic RZ, Rooney MT, Tuttle KR: Diabetic kidney disease: Challenges, progress, and possibilities. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 12: 2032–2045, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brenner BM, Cooper ME, de Zeeuw D, Keane WF, Mitch WE, Parving HH, Remuzzi G, Snapinn SM, Zhang Z, Shahinfar S; RENAAL Study Investigators: Effects of losartan on renal and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes and nephropathy. N Engl J Med 345: 861–869, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lewis EJ, Hunsicker LG, Clarke WR, Berl T, Pohl MA, Lewis JB, Ritz E, Atkins RC, Rohde R, Raz I; Collaborative Study Group: Renoprotective effect of the angiotensin-receptor antagonist irbesartan in patients with nephropathy due to type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 345: 851–860, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wanner C, Inzucchi SE, Lachin JM, Fitchett D, von Eynatten M, Mattheus M, Johansen OE, Woerle HJ, Broedl UC, Zinman B; EMPA-REG OUTCOME Investigators: Empagliflozin and progression of kidney disease in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 375: 323–334, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Neal B, Perkovic V, Mahaffey KW, de Zeeuw D, Fulcher G, Erondu N, Shaw W, Law G, Desai M, Matthews DR; CANVAS Program Collaborative Group: Canagliflozin and cardiovascular and renal events in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 377: 644–657, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wiviott SD, Raz I, Bonaca MP, Mosenzon O, Kato ET, Cahn A, Silverman MG, Zelniker TA, Kuder JF, Murphy SA, Bhatt DL, Leiter LA, McGuire DK, Wilding JPH, Ruff CT, Gause-Nilsson IAM, Fredriksson M, Johansson PA, Langkilde AM, Sabatine MS; DECLARE–TIMI 58 Investigators: Dapagliflozin and cardiovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 380: 347–357, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Perkovic V, Jardine MJ, Neal B, Bompoint S, Heerspink HJL, Charytan DM, Edwards R, Agarwal R, Bakris G, Bull S, Cannon CP, Capuano G, Chu PL, de Zeeuw D, Greene T, Levin A, Pollock C, Wheeler DC, Yavin Y, Zhang H, Zinman B, Meininger G, Brenner BM, Mahaffey KW; CREDENCE Trial Investigators: Canagliflozin and renal outcomes in type 2 diabetes and nephropathy. N Engl J Med 380: 2295–2306, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.American Diabetes Association: 11. Microvascular complications and foot care: Standards of medical care in diabetes-2019. Diabetes Care 42[Suppl 1]: S124–S138, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gerstein HC, Colhoun HM, Dagenais GR, Diaz R, Lakshmanan M, Pais P, Probstfield J, Botros FT, Riddle MC, Rydén L, Xavier D, Atisso CM, Dyal L, Hall S, Rao-Melacini P, Wong G, Avezum A, Basile J, Chung N, Conget I, Cushman WC, Franek E, Hancu N, Hanefeld M, Holt S, Jansky P, Keltai M, Lanas F, Leiter LA, Lopez-Jaramillo P, Cardona Munoz EG, Pirags V, Pogosova N, Raubenheimer PJ, Shaw JE, Sheu WH, Temelkova-Kurktschiev T; REWIND Investigators: Dulaglutide and renal outcomes in type 2 diabetes: An exploratory analysis of the REWIND randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 394: 131–138, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tuttle KR, Lakshmanan MC, Rayner B, Busch RS, Zimmermann AG, Woodward DB, Botros FT: Dulaglutide versus insulin glargine in patients with type 2 diabetes and moderate-to-severe chronic kidney disease (AWARD-7): A multicentre, open-label, randomised trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 6: 605–617, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]