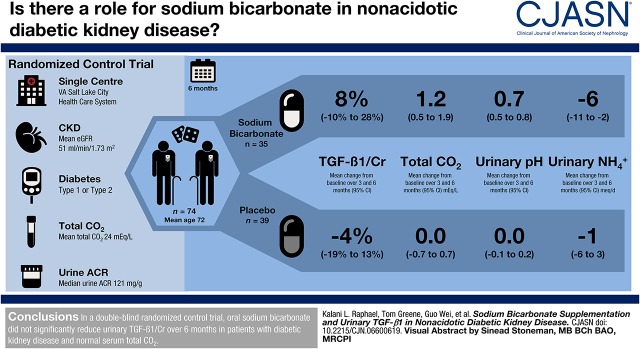

Visual Abstract

Keywords: diabetes mellitus, chronic kidney disease, TGF-beta, acidosis, humans, human LCN2 protein, lipocalin, creatinine, sodium bicarbonate, diabetic nephropathies, carbon dioxide, human FN1 protein, fibronectins, veterans, ammonium compounds, human HAVCR1 protein, hepatitis A virus cellular receptor 1, kidney function tests, bicarbonate, transforming growth factors, chronic renal insufficiency, albumins

Abstract

Background and objectives

In early-phase studies of individuals with hypertensive CKD and normal serum total CO2, sodium bicarbonate reduced urinary TGF-β1 levels and preserved kidney function. The effect of sodium bicarbonate on kidney fibrosis and injury markers in individuals with diabetic kidney disease and normal serum total CO2 is unknown.

Design, setting, participants, & measurements

We conducted a randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled study in 74 United States veterans with type 1 or 2 diabetes mellitus, eGFR of 15–89 ml/min per 1.73 m2, urinary albumin-to-creatinine ratio (UACR) ≥30 mg/g, and serum total CO2 of 22–28 meq/L. Participants received oral sodium bicarbonate (0.5 meq/kg lean body wt per day; n=35) or placebo (n=39) for 6 months. The primary outcome was change in urinary TGF-β1-to-creatinine from baseline to months 3 and 6. Secondary outcomes included changes in urinary kidney injury molecule-1 (KIM-1)-to-creatinine, fibronectin-to-creatinine, neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin (NGAL)-to-creatinine, and UACR from baseline to months 3 and 6.

Results

Key baseline characteristics were age 72±8 years, eGFR of 51±18 ml/min per 1.73 m2, and serum total CO2 of 24±2 meq/L. Sodium bicarbonate treatment increased mean total CO2 by 1.2 (95% confidence interval [95% CI], 0.3 to 2.1) meq/L, increased urinary pH by 0.6 (95% CI, 0.5 to 0.8), and decreased urinary ammonium excretion by 5 (95% CI, 0 to 11) meq/d and urinary titratable acid excretion by 11 (95% CI, 5 to 18) meq/d. Sodium bicarbonate did not significantly change urinary TGF-β1/creatinine (difference in change, 13%, 95% CI, −10% to 40%; change within the sodium bicarbonate group, 8%, 95% CI, −10% to 28%; change within the placebo group, −4%, 95% CI, −19% to 13%). Similarly, no significant effect on KIM-1-to-creatinine (difference in change, −10%, 95% CI, −38% to 31%), fibronectin-to-creatinine (8%, 95% CI, −15% to 37%), NGAL-to-creatinine (−33%, 95% CI, −56% to 4%), or UACR (1%, 95% CI, −25% to 36%) was observed.

Conclusions

In nonacidotic diabetic kidney disease, sodium bicarbonate did not significantly reduce urinary TGF-β1, KIM-1, fibronectin, NGAL, or UACR over 6 months.

Introduction

Diabetes mellitus is a major global health problem and is a leading cause of CKD. There are few interventions that prevent progression of diabetic kidney disease to ESKD, and identifying novel strategies that preserve kidney function in patients with diabetes is a major priority.

Results from early-phase studies suggest that treatment with oral alkali may preserve the eGFR (1–5). Importantly, preservation of the eGFR with alkali treatment was observed in studies that included patients with metabolic acidosis (1–3) as well as those with normal serum total CO2 (4,5). The finding in the latter circumstance is particularly intriguing because most patients with CKD have normal serum total CO2 and are not treated with alkali on the basis of current practice standards (6–8). This raises the possibility that alkali might be prescribed before metabolic acidosis develops, with the goal of preserving the eGFR. If so, this would lead to a major paradigm shift in how alkali is utilized in CKD.

Studies investigating the effects of alkali supplementation on kidney injury and function in patients with normal total CO2 have thus far been conducted exclusively in the setting of hypertensive CKD (4,5). Although it is plausible that these findings might apply to patients with diabetes, the kidney effects of alkali supplementation might be different in those with diabetes. One mechanism by which alkali may preserve the eGFR in patients with CKD and normal serum total CO2 is by attenuating kidney ammonia production, as high levels of ammonia in the kidney activate the complement pathway leading to tubulointerstitial fibrosis (9). Along these lines, urinary ammonium excretion was directly associated with urinary levels of the profibrotic molecule TGF-β1 in patients with CKD (10). In prior studies in hypertensive CKD, alkali lowered urinary acid excretion and urinary TGF-β1 levels in those with (3,11) and without metabolic acidosis (12). Although kidney ammonia production is stimulated by nonvolatile acid (13), gluconeogenesis in proximal tubule cells also forms ammonia during the conversion of glutamine to α-ketoglutarate (14). In diabetes mellitus, kidney gluconeogenesis is upregulated and although alkali suppresses gluconeogenesis in vitro, it is unclear if this occurs in humans (15,16). Thus, alkali may mitigate acid-induced kidney ammonia production, but may not attenuate kidney ammonia production owing to gluconeogenesis in patients with diabetes. Hence, the effects of alkali on TGF-β1, tubulointerstitial fibrosis, and eGFR may be different in individuals with diabetic kidney disease than in those with hypertensive CKD.

We conducted a randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled study in individuals with diabetic kidney disease and normal serum total CO2 to test the hypothesis that sodium bicarbonate reduces urinary TGF-β1 levels (primary outcome) over 6 months. Secondary outcomes were urinary levels of kidney injury molecule-1 (KIM-1), fibronectin, neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin (NGAL), and urinary albumin-to-creatinine ratio (UACR), which have been implicated as biomarkers of CKD progression risk (17–20).

Materials and Methods

Study Design and Population

This was a single-center, randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled study in 74 United States veterans with diabetic kidney disease at the Veterans Affairs Salt Lake City Health Care System (VASLCHCS). Key inclusion criteria were age >18 years, type 1 or 2 diabetes mellitus, serum total CO2 of 22–28 meq/L, eGFR of 15–89 ml/min per 1.73 m2, and UACR≥30 mg/g. Key exclusion criteria were use of oral alkali, serum potassium <3.5 meq/L, use of five or more antihypertensive agents, systolic BP >140 mm Hg or diastolic BP >90 mm Hg, diagnosis of congestive heart failure with New York Heart Association class 3 or 4 symptoms, chronic immunosuppressive therapy, kidney transplantation, significant fluid overload, or lean body wt >100 kg (21). Participants were enrolled from November 2012 through October 2017.

Intervention and Randomization

Participants were randomly assigned (1:1) to receive either sodium bicarbonate or placebo for 6 months. An investigational pharmacist created the randomization sequence using a random number generator in blocks of ten, randomized the participants, and maintained the sequence throughout the trial. Both participants and investigators were masked to the treatment assignments. The daily dose of sodium bicarbonate was 0.5 meq/kg lean body wt, and half the dose was taken twice daily. This dose was selected because it preserved the eGFR in a prior study of hypertensive patients with CKD with normal serum total CO2 (5).

Study Outcomes

The primary outcome was mean change in urinary TGF-β1-to-creatinine from baseline, assessed at both 3 months and 6 months postrandomization. TGF-β1 was chosen as the primary outcome because it is an important mediator of tubulointerstitial fibrosis in diabetic kidney disease (22–26) and prior studies found that alkali treatment reduced urinary levels of TGF-β1 (3,11,12). Initial secondary outcomes of the trial were changes in urinary levels of the alternative pathway of complement fragment Bb and membrane attack complex; however, we were unable to measure these because of technical difficulties. We therefore measured urinary levels of KIM-1-to-creatinine, fibronectin-to-creatinine, NGAL-to-creatinine, and UACR and designated these as secondary outcomes. Finally, we explored the effect of sodium bicarbonate on the eGFR, creatinine clearance, and BUN.

Study Visits and Measurements

Participants had in-person visits at baseline and 3 and 6 months postrandomization. Trained study coordinators enrolled participants and obtained demographic, comorbidity, and medication data using standardized forms. BP was measured three times, 1 minute apart, after 5 minutes of quiet rest at each study visit; the average was used for data analysis. Twenty-four-hour urine samples were collected under mineral oil at baseline and 3 and 6 months postrandomization. Urine pH was measured using a pH meter. Urinary ammonium and titratable acid were measured using the formalin-titrimetric method (10). TGF-β1, KIM-1, fibronectin, and NGAL were measured using Human Quantikine ELISA kits from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN). All other laboratory measurements were performed by the VASLCHCS clinical laboratory. The GFR was estimated using the CKD Epidemiology Collaboration formula (27).

Study Oversight

The study was funded by US Department of Veterans Affairs Clinical Sciences Research and Development Service and was approved by Institutional Review Boards of the University of Utah and VASLCHCS. All participants signed an informed consent document. The study was performed under the principles embodied in the Declaration of Helsinki. A Data Monitoring Committee, established by the Department of Veterans Affairs Clinical Sciences Research and Development Service, provided oversight of the study. The study was registered at Clinicaltrials.gov (identifier NCT01574157).

Sample Size and Power Calculation

Sample size calculations were on the basis of prior data in which sodium citrate reduced urinary TGF-β1-to-creatinine by 16.3 ng/g, or 17%, from the mean baseline level of 94.0 (SD 28.7) ng/g creatinine (3), and from Song et al. (28) who reported a pooled SD of 25% in the percent change in urinary TGF-β1-to-creatinine over 16 weeks in 21 patients. If the Pearson correlation among the percent changes in the urinary TGF-β1 levels from baseline to the two follow-up assessments were not to exceed 0.90, the estimated SD of the average percent change over the 3- and 6-month assessments would not exceed 24%. Under these assumptions, 32 patients with complete follow-up in each treatment group would provide ≥80% power at a two-sided α=0.05 in the primary analysis to detect a 17% difference in the average percent change between the treatment groups. A sample size of 37 enrolled participants in each group was targeted, allowing for a loss to follow-up of up to 14%.

Statistical Analyses

Baseline characteristics by treatment group were summarized using means, medians, or frequencies, as appropriate. Linear mixed-effects models were used to estimate the average effect of the randomized treatment on the mean level of each outcome across the month 3 and month 6 visits. The models used an unstructured covariance matrix to account for serial correlation, and were parameterized such that each outcome shared a common mean baseline value across treatment groups. Assumption of a common baseline mean across treatment groups is approximately equivalent to adjustment for the baseline levels of the outcome and is recommended under the randomized design to increase statistical power. Given their right-skewness, urinary TGF-β1-to-creatinine, KIM-1-to-creatinine, fibronectin-to-creatinine, NGAL-to-creatinine, and UACR were natural log-transformed before analysis, then the resulting model coefficients were converted to percent differences in geometric means. Imputation of missing data were not performed, so that results of the mixed models assume that data were missing at random after accounting for nonmissing baseline and follow-up measurements. Statistical analyses were performed with Stata 15 (College Station, TX) and SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute).

Results

Baseline characteristics of the randomized participants are shown in Table 1. Mean (SD) age was 72 (8) years, 97% were men, and 92% were non-Hispanic white. Mean (SD) eGFR was 51 (18) ml/min per 1.73 m2 and median (interquartile range) UACR was 121 (58–370) mg/g. Mean (SD) values of acid-base indices were serum total CO2 of 24 (2) meq/L, urinary ammonium of 34 (20) meq/d, urinary titratable acid of 32 (15) meq/d, and urinary pH 5.5 (0.4). Clinical characteristics were similar between the groups.

Table 1.

Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of study participants

| Characteristic | Total (n=74) | Sodium Bicarbonate (n=35) | Placebo (n=39) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||

| Age, yr | 72 (8) | 70 (8) | 73 (8) |

| Male, n (%) | 72 (97) | 34 (97) | 38 (97) |

| Non-Hispanic white, n (%) | 68 (92) | 32 (91) | 36 (92) |

| Comorbidities | |||

| eGFR, ml/min per 1.73 m2 | 51 (18) | 50 (20) | 52 (16) |

| Systolic BP, mm Hg | 128 (12) | 129 (12) | 127 (11) |

| Use of ACE-i/ARB, n (%) | 62 (84) | 28 (80) | 34 (87) |

| Weight, kg | 101 (20) | 100 (18) | 101 (22) |

| Lean body wt, kg | 68 (9) | 67 (8) | 68 (9) |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 33 (6) | 33 (6) | 33 (6) |

| Coronary artery disease, n (%) | 15 (20) | 6 (17) | 9 (23) |

| Congestive heart failure, n (%) | 5 (7) | 1 (3) | 4 (10) |

| Laboratory data | |||

| Serum total CO2, meq/L | 24 (2) | 24 (3) | 24 (2) |

| Serum K+, meq/L | 4.2 (0.4) | 4.2 (0.4) | 4.3 (0.4) |

| Hemoglobin A1C, % | 7.5 (1.1) | 7.5 (1.0) | 7.6 (1.3) |

| Urinary albumin-to-Cr, mg/ga | 121 (58–370) | 121 (84–412) | 131 (46–324) |

| Urinary pH | 5.5 (0.4) | 5.6 (0.4) | 5.4 (0.4) |

| Urinary NH4+, meq/d | 34 (20) | 36 (18) | 33 (21) |

| Urinary titratable acid, meq/d | 32 (15) | 32 (14) | 31 (16) |

| Urinary TGF-β1-to-Cr, ng/ga | 112 (74–157) | 122 (79–186) | 103 (68–147) |

| Urinary KIM-1-to-Cr, ng/mga | 0.89 (0.58–1.87) | 0.91 (0.57–1.87) | 0.88 (0.59–1.89) |

| Urinary fibronectin-to-Cr, ng/mg | 102 (74–173) | 107 (75–194) | 97 (65–147) |

| Urinary NGAL-to-Cr, ng/mga | 11.1 (6.5–23.8) | 10.5 (7.0–23.6) | 11.9 (6.3–24.0) |

Continuous variables shown as mean (SD). ACE-i, angiotensin converting enzyme-inhibitor; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; Cr, creatinine; KIM-1, kidney injury molecule-1; NGAL, neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin.

Shown as median (interquartile range).

The mean (SD) prescribed dose of sodium bicarbonate (n=35) was 2.9 (0.4) g/d. Nineteen (54%) participants were prescribed 2600 mg/d (4 pills/d), 15 (43%) were prescribed 3250 mg/d (5 pills/d) and one (3%) was prescribed 1950 mg/d (3 pills/d). In the placebo group (n=39), 21 (54%), 14 (36%), two (5%), and two (5%) participants were prescribed 4, 5, 6, and 3 pills/d, respectively.

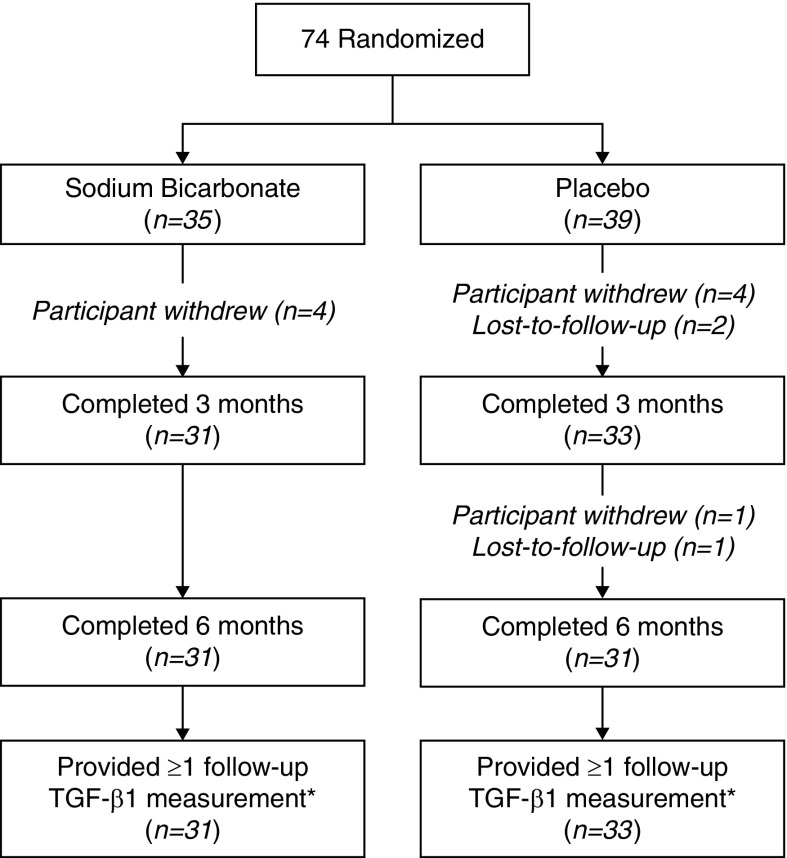

The disposition of study participants is shown in Figure 1. In the sodium bicarbonate group, 31 out of 35 (89%) participants completed the month 3 and 6 visits. In the placebo group, 33 (85%) completed the 3-month visit and 31 (79%) completed the 6-month visit. Two participants in placebo stopped treatment before the month 3 visit but completed all study visits; one had an allergic response to the placebo and one stopped because of weight gain. Pills were returned to assess adherence at 99 of the 126 (79%) follow-up visits. In the sodium bicarbonate group, adherence was ≥80% in 84% of pill counts (n=50), and in the placebo group, adherence was ≥80% in 80% of pill counts (n=49).

Figure 1.

Disposition of study participants. *The primary analysis used a mixed effects model that included baseline urinary TGF-β1 measurements from all randomized patients and all nonmissing follow-up TGF-β1 measurements.

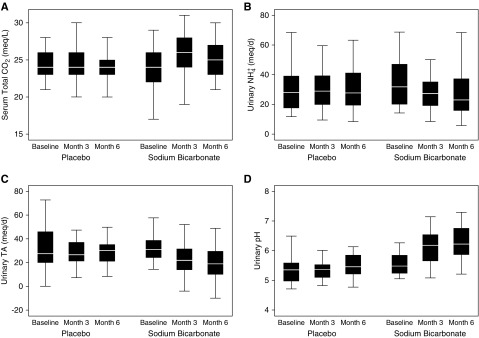

Effect of Sodium Bicarbonate on Acid-Base Indices

When compared with placebo, the sodium bicarbonate intervention increased mean serum total CO2 concentration by 1.2 meq/L and urinary pH by 0.6–0.7, and decreased mean urinary titratable acid excretion by 11–12 meq/d (Figure 2, Table 2). In comparison with titratable acid excretion, the treatment effect on urinary ammonium excretion was less robust. Mean urinary ammonium excretion was 7 meq/d lower at month 3, 4 meq/d lower at month 6, and 5 meq/d lower over the follow-up period (Figure 2, Table 2).

Figure 2.

Sodium bicarbonate increased serum total CO2 and urinary pH and reduced urinary ammonium and titratable acid excretion. The horizontal white line within the box represents the median value. The lower boundary of the box represents the 25th percentile. The upper boundary of the box represents the 75th percentile. Whiskers represent the highest and lowest nonoutlier values (outliers include those that are >1.5 interquartile ranges away from the 25th to 75th percentiles).

Table 2.

Effect of the sodium bicarbonate intervention on acid-base indices

| Measurement | Serum Total CO2 (meq/L) | Urinary NH4+ (meq/d) | Urinary TA (meq/d) | Urinary pH | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sodium Bicarbonate | Placebo | Sodium Bicarbonate | Placebo | Sodium Bicarbonate | Placebo | Sodium Bicarbonate | Placebo | |

| Within-group Δ from baseline | ||||||||

| At mo 3 | 1.3 (0.4 to 2.1) | 0.1 (−0.8 to 0.9) | −8 (−13 to −3) | −1 (−5 to 4) | −10 (−15 to −5) | 2 (−3 to 7) | 0.6 (0.5 to 0.8) | 0.0 (−0.2 to 0.1) |

| At mo 6 | 1.0 (0.3 to 1.8) | −0.2 (−0.9 to 0.6) | −5 (−11 to 1) | −1 (−7 to 5) | −11 (−16 to −5) | 0 (−5 to 6) | 0.7 (0.6 to 0.9) | 0.1 (−0.1 to 0.3) |

| Over mo 3 and 6 | 1.2 (0.5 to 1.9) | 0.0 (−0.7 to 0.7) | −6 (−11 to −2) | −1 (−6 to 3) | −10 (−15 to −6) | 1 (−4 to 6) | 0.7 (0.5 to 0.8) | 0.0 (−0.1 to 0.2) |

| Sodium Bicarbonate versus Placebo | Sodium Bicarbonate versus Placebo | Sodium Bicarbonate versus Placebo | Sodium Bicarbonate versus Placebo | |||||

| Difference in change from baseline | ||||||||

| At mo 3 | 1.2 (0.0 to 2.4) | −7 (−13 to −1) | −12 (−19 to −5) | 0.7 (0.5 to 0.8) | ||||

| At mo 6 | 1.2 (0.1 to 2.2) | −4 (−12 to 4) | −11 (−19 to −3) | 0.6 (0.4 to 0.8) | ||||

| Over mo 3 and 6 | 1.2 (0.3 to 2.1) | −5 (−11 to 0) | −11 (−18 to −5) | 0.6 (0.5 to 0.8) | ||||

Data are shown as mean (95% confidence intervals). Positive values for difference in change indicate that the change was greater in the sodium bicarbonate group. TA, titratable acid.

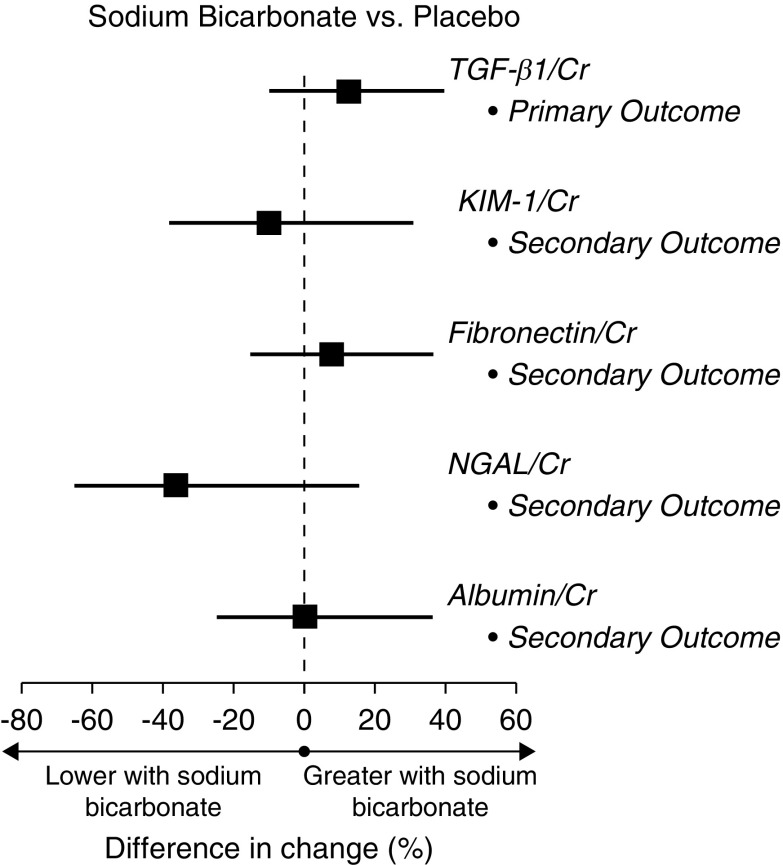

Effect of Sodium Bicarbonate on the Primary (Urinary TGF-β1) and Secondary Outcomes (Urinary KIM-1, Fibronectin, NGAL, and UACR)

There was a moderate imbalance in mean baseline values of urinary TGF-β1-to-creatinine between the treatment groups, although this was not statistically significant (Table 1). Within-group changes in urinary TGF-β1-to-creatinine over months 3 and 6 were not statistically significant in the sodium bicarbonate group (8%; 95% confidence interval [95% CI], −10% to 28%) or in the placebo group (−4%; 95% CI, −19% to 13%) (Table 3). In the primary analysis, which assessed the difference in mean change from baseline over 3 and 6 months between the groups, randomization to the sodium bicarbonate intervention did not significantly affect urinary TGF-β1-to-creatinine, with an estimated relative geometric increase of 13% (95% CI, −10% to 40%) compared with placebo (Figure 3, Table 3). The effect of the treatment on the individual 3 and 6 month assessments were similar. Sodium bicarbonate also had no statistically significant effect on the secondary outcomes KIM-1-to-creatinine, fibronectin-to-creatinine, NGAL-to-creatinine, or UACR over 3 and 6 months (Figure 3, Table 3). The results were similar for each assessment at each individual time point.

Table 3.

Effects of the sodium bicarbonate intervention on the primary (urinary TGF-β1) and secondary outcomes (urinary fibronectin, KIM-1, NGAL, and albumin)

| Outcome | Primary Outcome | Secondary Outcomes | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TGF-β1/Cr | Fibronectin/Cr | KIM-1/Cr | NGAL/Cr | Albumin/Cr | ||||||

| Sodium Bicarbonate | Placebo | Sodium Bicarbonate | Placebo | Sodium Bicarbonate | Placebo | Sodium Bicarbonate | Placebo | Sodium Bicarbonate | Placebo | |

| Within-group Δ from baseline | ||||||||||

| At mo 3 | 2% (−18% to 27%) | −11% (−28% to 10%) | 6% (−19% to 37%) | 3% (−20% to 32%) | −7% (−36% to 36%) | −13% (−40% to 25%) | −35% (−59% to 2%) | 2% (−34% to 58%) | 22% (−2 to 52) | 9% (−12% to 36%) |

| At mo 6 | 13% (−6% to 36%) | 3% (−15% to 24%) | 12% (−9% to 38%) | −1% (−20% to 23%) | −16% (−38% to 14%) | 12% (−18% to 52%) | −21% (−46% to 16%) | 10% (−26% to 64%) | 9% (−19% to 46%) | 19% (−12% to 60%) |

| Over mo 3 and 6 | 8% (−10% to 28%) | −4% (−19% to 13%) | 9% (−9% to 31%) | 1% (−16% to 21%) | −11% (−33% to 17%) | −2% (−25% to 29%) | −29% (−49% to 0%) | 6% (−24% to 48%) | 21% (−3% to 51%) | 12% (−11% to 40%) |

| Sodium Bicarbonate versus Placebo | Sodium Bicarbonate versus Placebo | Sodium Bicarbonate versus Placebo | Sodium Bicarbonate versus Placebo | Sodium Bicarbonate versus Placebo | ||||||

| Difference in change from baseline | ||||||||||

| At mo 3 | 15% (−13% to 53%) | 3% (−27% to 45%) | 7% (−36% to 81%) | −36% (−65% to 16%) | 12% (−18% to 52%) | |||||

| At mo 6 | 10% (−14% to 41%) | 13% (−16% to 51%) | −25% (−50% to 13%) | −28% (−58% to 22%) | −9% (−40% to 38%) | |||||

| Over mo 3 and 6 | 13% (−10% to 40%) | 8% (−15% to 37%) | −10% (−38% to 31%) | −33% (−56% to 4%) | 1% (−25% to 36%) | |||||

Data are shown as geometric mean percentage change (95% confidence intervals). Positive values for difference in change indicate that the change was greater in the sodium bicarbonate group. Cr, creatinine; KIM-1, kidney injury molecule-1; NGAL, neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin.

Figure 3.

Sodium bicarbonate had no statistically significant effect on the primary or secondary outcomes. Shown are the geometric mean percentage differences in change from baseline over 3 and 6 months between the groups for each outcome; the horizontal bars indicate the 95% confidence interval. Cr, creatinine; KIM-1, kidney injury molecule-1; NGAL, neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin.

Exploratory Evaluation of the Effect of Sodium Bicarbonate on Kidney Function

Mean eGFR over the follow-up period was 3.4 ml/min per 1.73 m2 higher in the sodium bicarbonate; however, this was not statistically significant (Table 4). BUN levels were statistically significantly lower during follow-up in the sodium bicarbonate group (Table 4). There was no significant difference between the groups with respect to creatinine clearance or 24-hour urinary creatinine excretion during follow-up (Table 4).

Table 4.

Effects of the sodium bicarbonate intervention on exploratory outcomes (kidney function) and BP, total body weight, and serum potassium

| Variable | Difference in Change from Baseline to mo 3 (95% CI) | Difference in Change from Baseline to mo 6 (95% CI) | Difference in Change from Baseline to mo 3 and 6 (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| eGFR, ml/min per 1.73 m2 | 2.8 (−1.2 to 6.8) | 4.0 (−0.5 to 8.5) | 3.4 (−0.1 to 6.8) |

| BUN, mg/dl | −6 (−9 to −2) | −6 (−10 to −1) | −6 (−9 to −2) |

| Creatinine clearance, ml/min | 0 (−11 to 11) | 5 (−9 to 20) | 3 (−8 to 13) |

| 24-h urinary creatinine, mg/d | −103 (−381 to 175) | −6 (−320 to 308) | −55 (−290 to 180) |

| Systolic BP, mm Hg | 6 (0 to 13) | 2 (−5 to 9) | 4 (−2 to 10) |

| Diastolic BP, mm Hg | 2 (−2 to 7) | −1 (−4 to 4) | 1 (−2 to 5) |

| Total body wt, kg | −1.3 (−3.0 to 0.5) | −0.9 (−3.0 to 1.2) | −1.1 (−2.8 to 0.6) |

| Serum potassium, meq/L | −0.1 (−0.2 to 0.1) | −0.1 (−0.3 to 0.1) | −0.1 (−0.2 to 0.1) |

Positive values for difference in change indicate that the change was greater in the sodium bicarbonate group. 95% CI, 95% confidence interval.

Exploratory Evaluation of Effects on BP, Weight, and Serum Potassium Concentration

In the sodium bicarbonate group, systolic BP was statistically significantly higher (6 mm Hg; 95% CI, 0 to 13 mm Hg) at month 3 but not at month 6 (Table 4). The mean systolic BP over months 3 and 6 was 4 mm Hg higher in the sodium bicarbonate group, but this difference was not statistically significant. Diastolic BP was similar between the groups during follow-up (Table 4). Sodium bicarbonate treatment did not increase total body weight or lower serum potassium concentration relative to the placebo group (Table 4).

Discussion

Alkali supplementation is recommended for patients with CKD with metabolic acidosis to mitigate adverse effects of metabolic acidosis on bone and muscle health (6). Treatment of metabolic acidosis with alkali may also preserve kidney function (1–5). In this study, we investigated the kidney effects of sodium bicarbonate supplementation in patients with diabetic kidney disease and normal serum total CO2, a setting in which alkali is not administered on the basis of current practice standards. In contrast to hypertensive patients with CKD (12), sodium bicarbonate did not lower urinary TGF-β1 levels in patients with diabetic kidney disease and normal serum total CO2. Sodium bicarbonate supplementation also had no statistically significant effect on urinary levels of KIM-1, NGAL, fibronectin, or albumin.

One intriguing finding in this study is that sodium bicarbonate had a modest effect on urinary ammonium excretion relative to titratable acid excretion. Whereas mean titratable acid excretion during follow-up was 11 meq/d lower in the sodium bicarbonate group relative to the placebo group, ammonium excretion was only 5 meq/d lower during follow-up. When considering the mean baseline levels of ammonium and titratable acid excretion were 34 and 32 meq/d, respectively, the dose of sodium bicarbonate used here resulted in a 15% reduction in ammonium excretion as compared with a 34% reduction in titratable acid excretion. We believe the modest effect on ammonium excretion could potentially explain the absence of a treatment effect on urinary TGF-β1. Our overarching hypothesis was that sodium bicarbonate treatment would reduce kidney ammoniagenesis, reduce tissue levels of ammonia, attenuate activation of the alternative pathway of complement in the kidney, and reduce tubulointerstitial fibrosis. The failure to substantially reduce urinary ammonium excretion suggests that kidney ammonia production, and consequently tissue levels of ammonia, were not considerably affected, potentially explaining why the sodium bicarbonate intervention did not lower urinary TGF-β1 levels.

It is unlikely that the modest effect on urinary ammonium excretion was owing to poor adherence, because sodium bicarbonate treatment resulted in statistically significant effects on serum total CO2 concentration, urinary titratable acid, and urinary pH. It is possible that a higher dose of sodium bicarbonate might have produced a more pronounced effect on urinary ammonium excretion and preliminary results from the Bicarbonate Administration to Stabilize eGFR pilot trial support this hypothesis. Nevertheless, the imbalanced effect of sodium bicarbonate on urinary ammonium and urinary titratable acid excretion observed here suggests that kidney ammonia production was maintained through pathways that are not directly related to the acid/alkali load. As mentioned, kidney gluconeogenesis in proximal tubule cells is upregulated in diabetes and is a potential source of kidney ammonia (15). Because we did not investigate the effect of alkali treatment on gluconeogenesis, we can only speculate that this may explain these findings. It will be important to study the effect of alkali supplementation on urinary ammonium excretion in other studies involving patients with diabetic kidney disease, and if our findings are confirmed, determining the underlying mechanisms would be of interest. Hypokalemia is another stimulus of kidney ammonia production (29). However, serum potassium <3.5 meq/L was an exclusion criterion and sodium bicarbonate had little effect on serum potassium concentration during the study. Kidney function is also a determinant of kidney ammonia production, and lower eGFR is associated with lower urinary ammonium excretion (10,30). A mild, but not statistically significant, increase in the eGFR in the sodium bicarbonate group was observed during the study. However, it is unclear why sodium bicarbonate treatment would reduce titratable acid excretion more than ammonium excretion in response to a mild increase in the eGFR.

Sodium bicarbonate also had no statistically significant effect on markers of kidney tubule (KIM-1, NGAL) or glomerular injury (fibronectin), although urinary NGAL excretion was reduced by 33%. In the kidney, NGAL is derived from proximal tubule cells, the loop of Henle, and the collecting duct, whereas KIM-1 is primarily derived from proximal tubule cells. The reduction in NGAL but not KIM-1 suggests that sodium bicarbonate may have attenuated injury in the loop of Henle and/or the collecting duct. These are regions with high tissue concentrations of ammonia owing to the interstitial concentration gradient. The mild reduction in ammonium excretion, however, suggests that the decrease in NGAL might not be mediated by ammonia. Alternatively, endothelin-1, angiotensin II, and aldosterone facilitate kidney acid secretion in the collecting duct and have been implicated in the pathogenesis of acid-mediated kidney injury (31–33). By reducing the acid load, sodium bicarbonate treatment may have attenuated the activity of these molecules thereby reducing collecting duct injury and urinary NGAL levels. Given the multiple secondary outcomes assessed, the urinary NGAL findings should be interpreted with caution and confirmed in other studies.

In terms of safety, we did not observe a consistent effect on BP. Mean systolic BP was statistically significantly higher (6 mm Hg) at month 3 in the sodium bicarbonate arm, but no appreciable difference was observed at month 6. We also did not observe an increase in total body weight or a reduction in the serum potassium concentration.

This study enrolled individuals with CKD and normal total CO2. Hence, these findings may not apply to individuals with metabolic acidosis. Results from early-phase studies in patients with CKD with metabolic acidosis suggest that alkali treatment preserves kidney function (1–3), and large-scale trials to determine the efficacy of this intervention on kidney and other organ systems should be conducted in this setting. With respect to those with normal total CO2, future studies investigating the kidney protective effects of alkali supplementation should consider administering a higher dose of sodium bicarbonate than the one used here.

A strength of this study is that it was randomized, double-blinded, and placebo-controlled. We also evaluated the effect of sodium bicarbonate treatment on several markers of kidney injury. A limitation of this study is that the vast majority of participants were men and non-Hispanic white, consistent with the veteran population in our region; hence, the results may not apply to other individuals with diabetic kidney disease. Although this was a small study, it is unlikely that a larger sample size would have affected our primary outcome, as urinary TGF-β1 levels were modestly increased with treatment. Finally, the study was underpowered and of insufficient duration to make reliable conclusions about the effect of sodium bicarbonate on kidney function.

In conclusion, sodium bicarbonate did not reduce urinary levels of TGF-β1 in patients with diabetic kidney disease and normal serum total CO2. The modest effect of sodium bicarbonate on urinary ammonium excretion may explain this finding.

Disclosures

Dr. Beddhu is supported by grants from Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, and the National Institutes of Health, outside of the submitted work. Dr. Beddhu also reports receiving consultant fees from Reata Pharmaceuticals outside of the submitted work. Dr. Cheung is supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Greene is supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health and reports receiving statistical consulting fees from DURECT Corporation, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, and Pfizer, Inc., outside of the submitted work. Dr. Raphael is supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health and US Department of Veterans Affairs Clinical Sciences Research and Development Service outside the submitted work. Dr. Raphael reports a one-time consulting fee from Tricida, Inc. in October 2016 outside the submitted work. Mr. Bullshoe, Ms. Tuttle, and Mr. Wei have nothing to disclose.

Funding

This study was supported by the US Department of Veterans Affairs Clinical Sciences Research and Development Service Career Development Award (IK2 CX000537, to Dr. Raphael).

Data Sharing Statement

Reidentified data reported in this manuscript will be shared upon request after publication, pursuant to a Data Use Agreement describing use of the data set and prohibiting the recipient from identifying or reidentifying (or taking steps to identify or reidentify) any individual whose data are included in the data set.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Beddhu, Dr. Cheung, Dr. Greene, and Dr. Raphael designed the study. Dr. Raphael enrolled participants. Mr. Bullshoe and Dr. Raphael performed laboratory measurements. Dr. Greene, Dr. Raphael, and Mr. Wei analyzed the data. Mr. Bullshoe, Dr. Raphael, and Ms. Tuttle prepared the figures and tables. Dr. Raphael drafted and revised the manuscript. All authors contributed significantly to the analysis and interpretation of the data, critically revised the manuscript, approved the final version of the manuscript, and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

The investigators wish to acknowledge the study participants and the following members of the research team: Jennifer Zitterkoph, Megan Varner, Katherine Mackin, and Sarah Neagle.

The contents do not represent the views of the US Department of Veterans Affairs or the US Government.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

References

- 1.de Brito-Ashurst I, Varagunam M, Raftery MJ, Yaqoob MM: Bicarbonate supplementation slows progression of CKD and improves nutritional status. J Am Soc Nephrol 20: 2075–2084, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dubey AK, Sahoo J, Vairappan B, Haridasan S, Parameswaran S, Priyamvada PS: Correction of metabolic acidosis improves muscle mass and renal function in chronic kidney disease stages 3 and 4: A randomized controlled trial [published online ahead of print July 24, 2018]. Nephrol Dial Transplant. Available at: 10.1093/ndt/gfy214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Phisitkul S, Khanna A, Simoni J, Broglio K, Sheather S, Rajab MH, Wesson DE: Amelioration of metabolic acidosis in patients with low GFR reduced kidney endothelin production and kidney injury, and better preserved GFR. Kidney Int 77: 617–623, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goraya N, Simoni J, Jo CH, Wesson DE: Treatment of metabolic acidosis in patients with stage 3 chronic kidney disease with fruits and vegetables or oral bicarbonate reduces urine angiotensinogen and preserves glomerular filtration rate. Kidney Int 86: 1031–1038, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mahajan A, Simoni J, Sheather SJ, Broglio KR, Rajab MH, Wesson DE: Daily oral sodium bicarbonate preserves glomerular filtration rate by slowing its decline in early hypertensive nephropathy. Kidney Int 78: 303–309, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) CKD Work Group. KDIGO 2012 clinical practice guideline for the evaluation and management of chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int Suppl 3: 1–150, 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moranne O, Froissart M, Rossert J, Gauci C, Boffa JJ, Haymann JP, M’rad MB, Jacquot C, Houillier P, Stengel B, Fouqueray B; NephroTest Study Group : Timing of onset of CKD-related metabolic complications. J Am Soc Nephrol 20: 164–171, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Raphael KL, Zhang Y, Ying J, Greene T: Prevalence of and risk factors for reduced serum bicarbonate in chronic kidney disease. Nephrology (Carlton) 19: 648–654, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nath KA, Hostetter MK, Hostetter TH: Pathophysiology of chronic tubulo-interstitial disease in rats. Interactions of dietary acid load, ammonia, and complement component C3. J Clin Invest 76: 667–675, 1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Raphael KL, Gilligan S, Hostetter TH, Greene T, Beddhu S: Association between urine ammonium and urine TGF-β1 in CKD. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 13: 223–230, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goraya N, Simoni J, Jo CH, Wesson DE: A comparison of treating metabolic acidosis in CKD stage 4 hypertensive kidney disease with fruits and vegetables or sodium bicarbonate. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 8: 371–381, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goraya N, Simoni J, Jo C, Wesson DE: Dietary acid reduction with fruits and vegetables or bicarbonate attenuates kidney injury in patients with a moderately reduced glomerular filtration rate due to hypertensive nephropathy. Kidney Int 81: 86–93, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Welbourne T, Weber M, Bank N: The effect of glutamine administration on urinary ammonium excretion in normal subjects and patients with renal disease. J Clin Invest 51: 1852–1860, 1972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goodman AD, Fuisz RE, Cahill GF Jr: Renal gluconeogenesis in acidosis, alkalosis, and potassium deficiency: Its possible role in regulation of renal ammonia production. J Clin Invest 45: 612–619, 1966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eid A, Bodin S, Ferrier B, Delage H, Boghossian M, Martin M, Baverel G, Conjard A: Intrinsic gluconeogenesis is enhanced in renal proximal tubules of Zucker diabetic fatty rats. J Am Soc Nephrol 17: 398–405, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Meyer C, Stumvoll M, Nadkarni V, Dostou J, Mitrakou A, Gerich J: Abnormal renal and hepatic glucose metabolism in type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Clin Invest 102: 619–624, 1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bolignano D, Lacquaniti A, Coppolino G, Donato V, Campo S, Fazio MR, Nicocia G, Buemi M: Neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin (NGAL) and progression of chronic kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 4: 337–344, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hosohata K, Ando H, Takeshita Y, Misu H, Takamura T, Kaneko S, Fujimura A: Urinary Kim-1 is a sensitive biomarker for the early stage of diabetic nephropathy in Otsuka Long-Evans Tokushima Fatty rats. Diab Vasc Dis Res 11: 243–250, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nowak N, Skupien J, Smiles AM, Yamanouchi M, Niewczas MA, Galecki AT, Duffin KL, Breyer MD, Pullen N, Bonventre JV, Krolewski AS: Markers of early progressive renal decline in type 2 diabetes suggest different implications for etiological studies and prognostic tests development. Kidney Int 93: 1198–1206, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Peralta CA, Katz R, Bonventre JV, Sabbisetti V, Siscovick D, Sarnak M, Shlipak MG: Associations of urinary levels of kidney injury molecule 1 (KIM-1) and neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin (NGAL) with kidney function decline in the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA). Am J Kidney Dis 60: 904–911, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Janmahasatian S, Duffull SB, Ash S, Ward LC, Byrne NM, Green B: Quantification of lean bodyweight. Clin Pharmacokinet 44: 1051–1065, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yu L, Border WA, Huang Y, Noble NA: TGF-beta isoforms in renal fibrogenesis. Kidney Int 64: 844–856, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen S, Hong SW, Iglesias-de la Cruz MC, Isono M, Casaretto A, Ziyadeh FN: The key role of the transforming growth factor-beta system in the pathogenesis of diabetic nephropathy. Ren Fail 23: 471–481, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen S, Jim B, Ziyadeh FN: Diabetic nephropathy and transforming growth factor-beta: Transforming our view of glomerulosclerosis and fibrosis build-up. Semin Nephrol 23: 532–543, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dronavalli S, Duka I, Bakris GL: The pathogenesis of diabetic nephropathy. Nat Clin Pract Endocrinol Metab 4: 444–452, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hills CE, Squires PE: TGF-beta1-induced epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition and therapeutic intervention in diabetic nephropathy. Am J Nephrol 31: 68–74, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH, Zhang YL, Castro AF 3rd, Feldman HI, Kusek JW, Eggers P, Van Lente F, Greene T, Coresh J; CKD-EPI (Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration) : A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med 150: 604–612, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Song JH, Cha SH, Lee HJ, Lee SW, Park GH, Lee SW, Kim MJ: Effect of low-dose dual blockade of renin-angiotensin system on urinary TGF-beta in type 2 diabetic patients with advanced kidney disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant 21: 683–689, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tolins JP, Hostetter MK, Hostetter TH: Hypokalemic nephropathy in the rat. Role of ammonia in chronic tubular injury. J Clin Invest 79: 1447–1458, 1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vallet M, Metzger M, Haymann JP, Flamant M, Gauci C, Thervet E, Boffa JJ, Vrtovsnik F, Froissart M, Stengel B, Houillier P; NephroTest Cohort Study group : Urinary ammonia and long-term outcomes in chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int 88: 137–145, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wesson DE, Dolson GM: Endothelin-1 increases rat distal tubule acidification in vivo. Am J Physiol 273: F586–F594, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wesson DE, Jo CH, Simoni J: Angiotensin II-mediated GFR decline in subtotal nephrectomy is due to acid retention associated with reduced GFR. Nephrol Dial Transplant 30: 762–770, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wesson DE, Simoni J: Acid retention during kidney failure induces endothelin and aldosterone production which lead to progressive GFR decline, a situation ameliorated by alkali diet. Kidney Int 78: 1128–1135, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]