Abstract

Objective.

This study evaluated the benefits of olanzapine versus placebo for adult outpatients with anorexia nervosa.

Method:

This randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of adult outpatients with anorexia nervosa was conducted at five sites in North America. Participants were randomized 1:1 to olanzapine or placebo and seen weekly for 16 weeks. The primary outcomes were rate of change in body weight and in obsessionality, assessed via the Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive-Scale (YBOCS).

Results.

The mean body mass index of the 152 participants was 16.7 kg/m2. One-hundred forty-six (96.1%) were women. Seventy-five participants were randomized to receive olanzapine and 77 to receive placebo. There was a statistically significant treatment by time interaction (F[1,1435] = 4.98; p = 0.026) indicating that the increase in body mass index over time was greater in the olanzapine group (0.259 ± 0.051 versus 0.095 ± 0.053 kg/m2 per month, respectively). There was no significant difference between the olanzapine and placebo groups in change in the YBOCS obsessions subscale over time (−0.325 versus −0.017 units per month; F[1,93] = 0.27; p = 0.60). There were no significant differences between olanzapine and placebo groups in the frequency of abnormalities on blood tests assessing potential metabolic disturbances.

Conclusions.

This study documented a modest therapeutic effect of olanzapine versus placebo on weight in outpatients with anorexia nervosa, but no significant benefit for psychological symptoms. Nevertheless, the finding is notable, as achieving change in weight is notoriously challenging in this disorder.

Trial registration.

clinicaltrials.gov Identifier:

Introduction

Anorexia Nervosa (AN) is a severe eating disorder characterized by the persistent maintenance of an abnormally low body weight associated with distinct psychological features including distortion of body image and, often, a lack of recognition of the seriousness of the low body weight (1). In the last several decades, family-based methods of treatment have been developed and demonstrated to be effective for younger patients (2). However, among adult patients, AN is often refractory to psychological treatment, and is associated with one of the highest mortality rates of any psychiatric disorder (3).

Efforts to develop effective pharmacological interventions for AN have been disappointing (4). Although patients with AN frequently experience significant symptoms of anxiety and depression, placebo-controlled trials of antidepressants for acute treatment or for relapse prevention following successful acute treatment have shown little or no evidence of efficacy (5, 6). Over 50 years ago, open trials in AN of the first antipsychotic medication, chlorpromazine, initially led to great enthusiasm, which waned over time with the appreciation of significant side effects (7). Small controlled trials of the antipsychotic medications pimozide and sulpiride in the 1980’s proved disappointing (8, 9). The introduction of second-generation antipsychotics rekindled interest in the potential utility of this class of medication, as has the documentation of dopaminergic disturbances in AN (10). In recent years, several small trials suggested potential benefit, especially of olanzapine the use of which is associated with substantial weight gain in other disorders, such as schizophrenia. Bissada et al. (11) found that, when employed in a 10-week structured day program, olanzapine, compared with placebo, was associated with a more rapid achievement of target BMI and a reduction in obsessional symptoms. Attia et al. (12), in an 8-week outpatient trial of 23 patients, reported that olanzapine was associated with more rapid weight gain than placebo. On the other hand, in a 10-week trial, Kafantaris et al. (13) found no benefit of olanzapine versus placebo among 20 adolescents with AN, nor did Brambilla et al. in a trial among 30 adults (14). A recent meta-analysis suggested that the research to date does not support the use of second generation antipsychotics for patients with AN (15); however, this conclusion is based only on small studies. Because of the lack of an effective pharmacological intervention and these mixed results, as well as biological plausibility, the current study was initiated to evaluate, in a large multisite, placebo-controlled trial, the efficacy of olanzapine in promoting weight gain and improving psychological symptoms among outpatients with AN.

Methods

This randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled 16-week trial of olanzapine versus placebo for outpatients with AN was conducted at five sites from December, 2010 to December, 2016: New York State Psychiatric Institute/Columbia University Medical Center, Weill Cornell Medical Center, University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, Johns Hopkins Medicine, and Toronto Center for Addiction and Mental Health. This was a parallel design with 1:1 randomization. The protocol was approved by the institutional review boards at each site, in accord with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, and a data safety and monitoring board oversaw the conduct of the trial. Participants provided written informed consent after receiving a complete description of the study.

Patient Recruitment:

Individuals were eligible to participate if they had a diagnosis of AN according to DSM-IV criteria (16) (with the exception of the requirement for amenorrhea), were between the ages of 18 and 65 years, and had a BMI greater than or equal to 14.0 kg/m2, and less than or equal to 18.5 kg/m2. Diagnosis was assessed via the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID) (17) and confirmed by clinician interview. Individuals were excluded from participation if 1) they had a medical problem that required urgent attention, including a serum potassium ≤ 2.5 mEq/L, a fasting blood glucose ≥ 120 mg/dL or a non-fasting glucose ≥ 140 mg/dL, an EKG with QTc > 480 msec, serum cholesterol or triglyceride level ≥ 1.5 times upper limit of normal; 2) had a psychiatric problem that required immediate attention, including acute suicidality, or a current diagnosis of substance abuse or dependence, schizophrenia, schizophreniform disorder, or bipolar illness; 3) had a neurologic problem, including movement disorder (e.g., tardive dyskinesia), history of a seizure disorder, or dementia; 4) had an allergy to olanzapine or a documented failure to respond to or inability to tolerate olanzapine 10 mg/day.

Eligible participants were required to have taken no antipsychotic medication or other medication known to affect weight in the previous four weeks. Participants could be on a stable dose of other psychotropic medications, and/or engaged in outpatient psychotherapy, if they had not consistently gained weight (> 3lbs) over the 4 weeks prior to study participation. Participants could not be in intensive outpatient treatments such as partial hospital or day programs.

Recruitment occurred primarily through clinical referrals and local media. If an initial telephone screening suggested potential eligibility, in-person screening with a study physician was scheduled.

Randomization:

Randomization lists, stratified by site and subtype, were generated by a computer program utilizing a random number generator seeded by time of day. Randomization assignments were kept by the pharmacy at each site. All clinical staff involved in the care of the patients, as well as study coordinators and statisticians, remained blind to medication assignment during the study. Olanzapine (2.5 mg) and matching placebo pills were provided gratis by Eli Lilly and Company.

Treatment:

Medication was dispensed in double-blind fashion after completion of baseline assessments. Participants met with a study psychiatrist weekly for 16 weeks. Medication was initiated at 2.5 mg/day (1 pill/day) for two weeks, then increased to 5 mg/day (2 pills/day) for 2 weeks. At week 4, the dose was increased to the maximum of 10 mg/day (4 pills/day). The titration was halted, or the dose was decreased, if the participant reported significant adverse effects.

The interactions with the psychiatrist during the weekly visits were guided by a manual (“MedPlus”), designed to enhance medication adherence. The 20–30-minute visits included a general review of symptoms and possible side effects, and support for continued study participation. Participants also received two sessions of nutrition counseling during the first month following randomization.

Participants could receive up to seven days of inpatient hospital care for acute problems without being withdrawn from the study. Treatment with study medication was terminated if 1) the participant met study exclusion criteria (e.g., BMI fell below 14.0 kg/m2), 2) weight decreased at four consecutive visits or fell to <90% of study baseline weight, or 3) the participant voluntarily withdrew, for example, to obtain a higher level of care.

Outcome Measures:

Height and weight were measured at baseline, and weight, the primary physical outcome measure, was measured at each weekly assessment. Overall illness severity and change were assessed by a study psychiatrist weekly using 7-point CGI-Severity (1=not at all; 7=among the most extremely ill patients) and CGI-Improvement (1=very much improved; 7=very much worse) scales. These were anchored to assessments of weight, eating behavior, and mood (see Supplementary Data 1).

The primary psychological outcome was obsessionality, assessed via the Yale Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale interview (YBOCS) (18, 19). As identified in the study’s exploratory aims, symptoms of eating disorder severity, depression, and anxiety were examined using the following assessments, collected at baseline, eight, and 16 weeks following randomization: Eating Disorder Examination (EDE) (20), Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) (21), and the Zung Anxiety Inventory (22). In order to encourage data contribution from all participants for intent-to-treat analyses, including those who may have stopped taking study medication, participants were compensated for their time for completing assessments at weeks 8 ($50) and 16 ($100).

Safety and Tolerability:

The severity of each of 22 somatic symptoms was assessed at each visit by a physician using a four-point scale (none, mild, moderate, and severe). Participants were also screened for the presence of involuntary movements using the Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale (AIMS) (23). Blood tests to assess potential metabolic problems and an EKG were obtained monthly.

Adherence:

Medication diaries and monthly pill counts, as well as mid-point and end of study measurement of serum olanzapine levels, were used to assess adherence.

Statistical Methods

Sample Size Calculation:

The study was designed to randomize 160 patients with equal allocation to olanzapine and placebo to provide >90% power to detect a difference of 0.57 pounds/week between groups. This threshold was selected based on the effect size calculated from previously published preliminary data (12).

Data Analysis:

Baseline characteristics were compared between olanzapine and placebo groups using two sample t-tests for continuous variables. Linear mixed effects models with random intercepts and random slopes were used to assess differences over time between the two groups on primary and secondary continuous measures following intent-to-treat principles, including all available assessments from all participants randomized. Each model included main effects of treatment and of time as well as their interaction to assess within-group change over time and between-group effects adjusting for study site and subtype.

Several exploratory analyses were also carried out. “Per-protocol” analyses were conducted including data only from participants who continued to take medication under double-blind conditions. The statistical tests for the per-protocol analyses were the same as the intent-to-treat analyses. Sequential propensity scores were estimated at each week and included as time-dependent weights in an inverse probability weighting (IPW) method to compute per-protocol effect (24). CGI-Improvement and CGI-Severity ratings were dichotomized as in other studies (25): much or very much improved as responder and no change or worse as non-responder; moderately or more severe as severe and mildly or less severe as non-severe. CGI ratings were analyzed using a generalized linear mixed effects model to estimate the odds of reduced CGI-Severity and of CGI-Improvement at week 16. Frequencies of somatic symptoms rated as moderate or severe and of laboratory abnormalities were compared in placebo and olanzapine groups at end of treatment (i.e., at the last visit when the participants were taking study medication) using chi-square tests. The Wilcoxon rank sum test was performed to compare medication dose at week 16. Statistical analysis was conducted using SAS 9.4 and Stata v.13 and all tests were two-sided with significance level equal to 0.05. Analyses of secondary outcome measures and exploratory analyses were not corrected for multiple comparisons.

Results

Patient Characteristics:

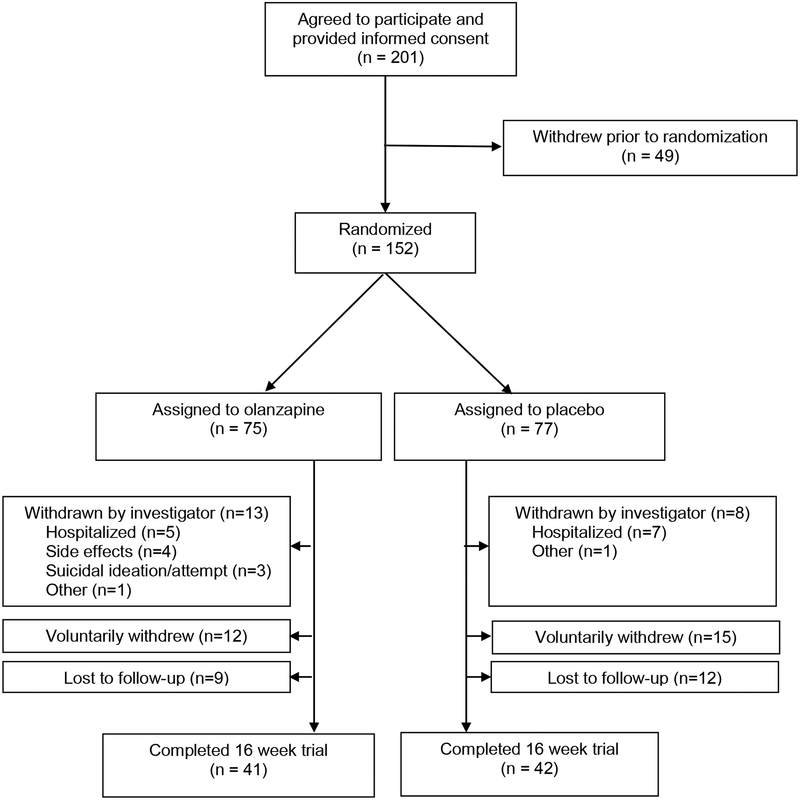

Two-hundred-one patients signed informed consent and 152 patients were assigned to medication or placebo (olanzapine n=75; placebo n=77; See Figure 1).

Figure 1.

CONSORT diagram

Demographic and clinical characteristics at baseline in placebo and olanzapine groups and across sites are summarized by site in Table 1. There were no statistically significant differences between the placebo and olanzapine groups. There were statistically significant differences among sites in mean BMI, age, and YBOCS-compulsions. Co-occurring psychiatric diagnoses included mood disorder (current: 32.9%, past: 36.8%), prior alcohol abuse (7.2%) or dependence (11.8%), prior substance abuse (5.3%) or dependence (7.2%), anxiety disorder (current: 40.1%; past: 18.4%), and prior eating disorder other than AN (9.2%). The mean number of comorbid diagnoses was 2.1 ± 1.4. Psychotropic medication use included antidepressants (n=45, 29.6%), sedative/hypnotics (n=23, 15.1%), or another psychotropic medication (n=19, 12.5%). Eighty-nine participants (58.6%) were taking no psychotropic medications.

Table 1.

Baseline Demographic and Clinical Characteristics (mean ± SD)

| By Medication | By Site | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Olanzapine (n=75) | Placebo (n=77) | Columbia (n=55) | Cornell (n=16) | Hopkins (n=25) | Pittsburgh (n=23) | Toronto (n=33) | |

| Age (years)* | 28.0 ± 10.9 | 30.0 ± 11.0 | 27.4 ± 10.6 | 36.6 ± 12.2 | 30.2 ± 12.0 | 28.8 ± 9.5 | 27.3 ± 10.0 |

| Duration of illness (years) | 10.5 ± 9.5 | 12.6 ± 11.7 | 10.4 ± 11.2 | 18.5 ± 11.1 | 13.6 ± 9.4 | 9.8 ± 7.5 | 10.6 ± 11.0 |

| Female (n, %) | 70 (94.6%) | 75 (97.4%) | 52 (94.6%) | 15 (93.8%) | 24 (100%) | 22 (95.7%) | 32 (97.0%) |

| Restricting Subtype (n, %) | 36 (48.0%) | 39 (50.7%) | 23 (41.8%) | 11 (68.8%) | 17 (68.0%) | 11 (47.8%) | 13 (39.4%) |

| Body Mass Index (kg/m2)* | 16.8 ± 1.2 | 16.7 ± 1.2 | 16.7 ± 1.2 | 17.3 ± 0.8 | 17.3 ± 0.9 | 16.7 ± 1.0 | 16.1 ± 1.2 |

| YBOCS, total | 16.5 ± 10.5 | 16.4 ± 10.0 | 17.2 ± 10.2 | 17.5 ± 8.8 | 13.3 ± 10.1 | 13.8 ± 11.7 | 19.0 ± 9.3 |

| YBOCS, obsessions | 7.64 ± 5.79 | 7.26 ± 5.50 | 8.07 ± 5.53 | 8.19 ± 5.69 | 6.08 ± 5.23 | 6.74 ± 5.96 | 7.58 ± 5.92 |

| YBOCS, compulsions* | 8.85 ± 5.60 | 9.18 ± 5.39 | 9.13 ± 5.53 | 9.31 ± 4.25 | 7.20 ± 5.21 | 7.09 ± 6.37 | 11.42 ± 4.70 |

| EDE, weight concerns | 3.02 ± 1.75 | 2.79 ± 1.73 | 2.71 ± 1.88 | 2.94 ± 1.51 | 2.79 ± 1.61 | 3.50 ± 1.70 | 2.87 ± 1.70 |

| EDE, restraint | 3.36 ± 1.60 | 2.89 ± 1.71 | 2.80 ± 1.76 | 2.93 ± 1.87 | 3.35 ± 1.38 | 3.10 ± 1.58 | 3.66 ± 1.61 |

| EDE, eating concerns | 2.08 ± 1.52 | 2.07 ± 1.50 | 1.87 ± 1.53 | 1.48 ± 1.29 | 2.44 ± 1.41 | 1.93 ± 1.49 | 2.52 ± 1.53 |

| EDE, shape concerns | 2.94 ± 1.76 | 2.94 ± 1.90 | 2.50 ± 1.88 | 2.97 ± 1.50 | 3.36 ± 1.73 | 3.40 ± 1.73 | 3.01 ± 1.95 |

| CES-D | 25.9 ± 12.7 | 28.3 ± 13.7 | 26.2 ± 13.3 | 23.2 ± 10.1 | 25.4 ± 13.8 | 27.7 ± 14.7 | 31.6 ± 12.7 |

| Zung Anxiety Inventory | 38.1 ± 6.6 | 38.8 ± 6.3 | 38.4 ± 7.0 | 38.6 ± 5.7 | 36.6 ± 4.8 | 38.7 ± 7.6 | 39.7 ± 6.1 |

| CGI Severity | 4.53 ± 0.93 | 4.52 ± 1.01 | 4.82 ± 0.75 | 4.56 ± 0.81 | 3.96 ± 0.84 | 4.43 ± 0.66 | 4.52 ± 1.39 |

YBOCS: Yale Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale. EDE: Eating Disorder Examination. CES-D: Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale

Significant difference across sites: (Age: F4,146 = 2.60, p = 0.038; BMI: F4,147 = 4.80, p = 0.001; YBOCS, compulsions: F4,146 = 3.19, p = 0.015

Primary Outcome Measures (see Table 2):

Table 2.

Estimate of change per month of BMI and psychological measures in olanzapine and placebo groups and of odds of change in CGI and effect sizes

| Olanzapine (n = 75) |

Placebo (n = 77) |

Effect size** (95% Confidence Interval) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BMI (kg/m2) | 0.259 | 0.095 | F[1,1435] = 4.98; p = 0.026 | 0.629(0.106, 1.151) |

| YBOCS, total | −0.800 | −0.762 | F[1,92] = 0.01; p = 0.94 | −0.027 (−0.419, 0.365) |

| YBOCS, obsessions | −0.325 | −0.017 | F[1,93] = 0.27; p = 0.60 | −0.063 (−0.443, 0.319) |

| YBOCS, compulsions | −0.499 | −0.561 | F[1,92] = 0.05; p = 0.82 | −0.011 (−0.395, 0.373) |

| EDE, weight concerns | 0.018 | −0.062 | F[1,91] = 1.22, p = 0.27 | 0.300 (−0.045, 0.644) |

| EDE, restraint | −0.094 | −0.122 | F[1,91] = 0.14, p = 0.71 | 0.342 (0.0005,0.683) |

| EDE, eating concerns | −0.084 | −0.081 | F[1,90] = 0.00, p = 0.96 | 0.051 (−0.284, 0.385) |

| EDE, shape concerns | 0.083 | −0.105 | F[1,91] = 7.10, p = 0.01 | 0.387 (0.055, 0.720) |

| CES-D | −0.585 | −0.934 | F[1,269] = 0.29; p = 0.59 | −0.106 (−0.493, 0.280) |

| Zung Anxiety | −0.225 | −0.216 | F[1,237] = 0.00; p = 0.98 | −0.133 (−0.600, 0.334) |

| CGI Severity* | 0.29 | 0.41 | t1356 = 0.41; p = 0.68 | Difference in rates: −6.4% (−36.8%, 24.0%) Odds Ratio: 0.716(0.146,3.521) |

| CGI Improvement† | 0.28 | 0.091 | t1213= 1.68; p = 0.094 | Difference in rates: 13.8% (−32.4%, 60.0%) Odds Ratio: 3.118(0.825, 11.782) |

odds of being severe

odds of improvement

Effect sizes for continuous outcome are calculated as the estimated difference between olanzapine and placebo groups at week 16 divided by the baseline standard deviation of the outcome; effect sizes for binary outcomes are calculated as differences in rates and odds ratios comparing olanzapine and placebo groups.

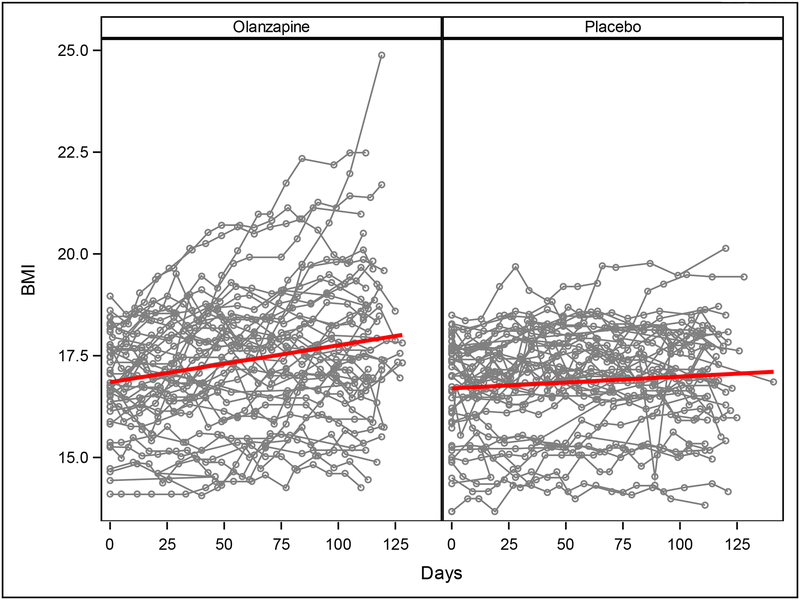

In the intent-to-treat, multilevel-model longitudinal analysis, which included all available data from all 152 patients randomized, olanzapine was associated with a significantly greater rate of weight gain (0.259 ± 0.051 kg/m2 per month) than placebo (0.095 ± 0.053 kg/m2 per month; F1,1435 = 4.98, p = 0.026) (Figure 2). There was no significant interaction between drug assignment and either subtype (Restricting versus Binge-Purge, F2,1435 =1.38, p=0.25) or treatment site (F8,1435= 1.06, p=0.39) on rate of change of BMI. There was no significant difference between olanzapine and placebo groups in rate of change in the YBOCS total score or in the YBOCS subscales.

Figure 2.

Change in BMI on olanzapine and placebo. Each fine line represents all available BMIs for one patient. The heavier lines depict the rate of change in BMI on olanzapine and placebo as estimated by multilevel-model longitudinal analysis.

Secondary Outcome Measures (see Table 2):

Individuals in the olanzapine group had a threefold greater likelihood of being rated much or very much improved at week 16, although this did not reach statistical significance (OR: 3.118, CI: 0.825, 11.782; p = 0.094); there was no significant difference between the groups in the likelihood of a reduction in CGI-Severity. There was no significant difference between olanzapine and placebo groups in rate of change in the EDE subscales for weight concerns, restraint, or eating concerns, the CES-D, or the Zung Anxiety Inventory. There was a significantly greater rate of increase on the EDE-shape concerns subscale in the olanzapine (0.083 ± 0.049 per month) vs. the placebo group (−0.105 ± 0.053 per month; F1,91=7.10, p = 0.01); there was no significant association between the increase in EDE shape concerns and rate of increase in BMI (F1,91=2.10, p=0.15). The results of the per-protocol analysis showed a similar pattern for both primary and secondary outcome measures (see Supplementary Table 1).

Adherence to protocol:

Ninety-eight participants (64.5%) continued to take the study medication at week 8, and 82 (53.9%) at week 16. There was no significant difference over time between the olanzapine and placebo groups in the likelihood of discontinuing study medication (log-rank p=0.65, see Supplementary Figure 1).

The average medication dose at week 16 was significantly lower in the olanzapine group: olanzapine 3.11 ± 1.07 pills/day (7.77 mg/day) vs placebo 3.76 ± 0.67 pills/day (Wilcoxon rank sum statistic S = 1863; p<0.001). Among patients in active treatment in the study, the mean plasma level of olanzapine in the olanzapine group was 19.0 ± 12.8 ng/mL week 8 and 18.5 ± 18.2 ng/mL at week 16.

There was no significant difference between the olanzapine and placebo groups in number of patients hospitalized during the study (8 (10.7%) vs 3 (3.9%), respectively; chi-square = 2.59, p = 0.11); nor was there a difference between the olanzapine and placebo groups in number of days hospitalized among those who were admitted to hospital (5.1 +1.6 days vs. 4.3 + 2.1 days; t = 0.67, p = 0.52). Three of the 75 patients on olanzapine were withdrawn for suicidal ideation or a suicide attempt, compared to no patient on placebo (p = 0.12, Fisher’s Exact Test).

Somatic effects:

At study termination, there were no significant differences in the frequency of abnormal results between olanzapine and placebo groups on blood tests to assess metabolic abnormalities (serum concentrations of cholesterol, triglycerides, high density lipoproteins (HDL), low density lipoproteins (LDL), the ratio of cholesterol to HDL, hemoglobin A1C, alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) (See Supplementary Table 2).

At study termination, a significantly smaller fraction of the patients in the olanzapine group was rated as having moderate or severe symptoms of trouble concentrating (14.5% vs 32.7%, χ2 = 5.45, p = 0.02), difficulty sitting still (6.5% vs 18.2%, χ2 = 3.81, p = 0.05), trouble falling asleep (9.7% vs 30.9%, χ2 = 8.32, p = 0.004), and trouble staying asleep (14.5% vs 40.0%, χ2 = 9.72, p = 0.002). There were also lower frequencies of complaints of headache (4.8% vs 14.5%, χ2 = 3.22, p = 0.07), tremors or shakiness (0.0% vs 5.5%, χ2 = 3.47, p = 0.06) and nervousness (14.5% vs 27.3%, χ2 = 2.91, p = 0.09) in the olanzapine group, although these differences did not reach statistical significance (See Supplementary Table 3).

Discussion

This multisite, randomized, controlled trial of olanzapine versus placebo with 152 participants is, to our knowledge, the largest medication trial conducted, to date, in AN. The study was conducted at five sites experienced in the treatment of AN, and patients with a range of other psychiatric disorders and on psychotropic medications were enrolled, lending support to the generalizability of the findings to treatment-seeking adults with AN.

The results of both the intent-to-treat and per-protocol analyses indicate that, in an outpatient setting, olanzapine offers modest benefit in weight gain, with those assigned to olanzapine gaining approximately 0.165 kg/m2 more per month than those assigned to placebo, equivalent to approximately one pound more per month for a woman of average height (5’5”). In other words, those on olanzapine gained 0.259 kg/m2 per month, equivalent to ~1.5 lb per month. There was also a tendency for patients in the olanzapine group to be more likely to be rated by their clinician as much or very much improved over time, which did not reach statistical significance. These results confirm and extend the results of several smaller trials (11, 12). Unlike Bissada et al. (11), however, we were unable to detect a therapeutic effect of olanzapine vs placebo on obsessionality, a characteristic psychological feature of AN.

The olanzapine was well-tolerated, and the rates of medication discontinuation in the olanzapine and placebo groups did not differ significantly (Supplementary Figure 1). That these rates of participation were adequate to measure an effect contrasts with previous reports that argued that medication studies of AN are futile (26). Three patients in the olanzapine group versus none in the placebo group were withdrawn because of suicidal ideation (n=2) or an attempt (n=1). This difference was not statistically significant, and individuals with AN are known to be at increased risk for suicide (27). In other clinical populations, data do not suggest an association between olanzapine and suicide (28). Blood measures of lipid, hepatic, and glucose metabolism showed no differences at the end of study in rates of abnormality in the olanzapine and placebo groups. The frequency of several somatic symptoms was significantly reduced at the end of study in the olanzapine compared to the placebo group, suggesting that olanzapine may have relieved some of the physical symptoms often experienced by individuals with AN.

We found a weight gain effect associated with olanzapine, but one that is more modest than the substantial, usually undesirable weight gain seen when olanzapine is used to treat other disorders (29). Whether or not weight gain associated with olanzapine in this study is secondary to the same mechanisms responsible for the more substantial weight gain described in other populations is unknown. The current study suggests that weight gain, as well as other effects that have been described in association with olanzapine (e.g., sedation, metabolic effects) are relatively mild in AN, generally well-tolerated, and potentially therapeutic.

Unfortunately, we found no evidence that olanzapine significantly impacted the characteristic psychopathological features of AN such as overconcern with gaining weight and obsessionality. In fact, the shape concerns subscale score of the EDE increased more among patients on olanzapine than among those on placebo. However, since the olanzapine and placebo groups did not differ significantly in change over time in the other secondary measures, including the three other subscales of the Eating Disorder Examination, and because there was not a significant relationship between change in the shape concerns subscale and rate of change in BMI, we cannot be certain that the difference between groups on the shape concerns subscale was not due to chance.

The failure to replicate the effect of olanzapine on obsessionality noted by Bissada et al. (11) may also relate to the challenges in measuring the psychological features of AN, as compared with objective measurement of weight. Underlying neurobiological mechanisms of AN are poorly understood. This, combined with the multiple neurobiological targets of olanzapine, raises challenges for this study in selecting the most useful metrics for measuring psychological variables that may associate with the change seen with olanzapine. Exploration of the psychological and genetic factors associated with response to olanzapine may be useful, both for personalizing care and for identifying targets for studying mechanisms of illness and for developing new treatment approaches.

The strengths of the current study, including its relatively large sample size, its being conducted at multiple sites, and its inclusion of patients with multiple other psychiatric disorders and on other psychotropic medications suggest the results are generalizable. Several limitations should also be noted, including a significant dropout rate, short duration, and its being conducted at tertiary centers very familiar with this population. Nonetheless, the current results suggest that olanzapine may provide a modest therapeutic benefit for outpatient adults with AN, a group much in need of effective treatment strategies. Olanzapine clearly does not alone constitute a sufficient treatment intervention and should be provided in the context of appropriate psychological and behavioral therapy. Furthermore, although longer than most previous trials of medication in AN, this study assessed the impact of olanzapine over only 16 weeks. Future studies should examine how best to combine olanzapine with other treatment interventions and assess longer-term outcomes. More broadly, the current study underscores the challenges of treating AN and the need for research to improve understanding of its relative refractoriness to both psychological and pharmacological treatments.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

The authors wish to thank DSMB members Maria LaVia, David Lowenthal and Ross Crosby for their input throughout the study. Additionally, authors wish to acknowledge Allegra Broft, Michael Devlin, Alexis Fertig, Sean Kerrigan, Laurel Mayer, Graham Redgrave, Matthew Shear, Lauren Belak, Christine Call, Janelle Coughlin, Gabriella Guzman, Jessica Lerman, Melanie Lipton, Margaret Martinez, Lily Offit, Melissa Prusky, Devin Rand-Giovanetti for their assistance.

Grant support: This work was supported, in part, by grant R01MH085921 from the National Institute for Mental Health. Eli Lilly and Company provided olanzapine and matched placebo pills, but did not provide financial support.

Footnotes

Disclosures: Drs. Attia and Steinglass receive royalties from UpToDate. Dr. Walsh receives royalties from UpToDate, McGraw-Hill, Guilford Press and Oxford University Press. Dr. Kaplan receives support from Shire. Dr. Wildes receives support from the American Psychological Association. Dr. Marcus serves on the Scientific Advisory Board for Weight Watchers International, Inc. Mr. Wu and Drs. Guarda, Schreyer, Wang and Yilmaz have nothing to disclose.

These data were presented, in part, at the XXII Annual Meeting of the Eating Disorders Research Society, New York, NY, October 29, 2016.

References

- 1.American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition Arlington,VA, American Psychiatric Association; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lock J, Le Grange D, Agras WS, Moye A, Bryson SW, Jo B. Randomized clinical trial comparing family-based treatment with adolescent-focused individual therapy for adolescents with anorexia nervosa. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67:1025–1032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arcelus J, Mitchell AJ, Wales J, Nielsen S. Mortality Rates in Patients With Anorexia Nervosa and Other Eating Disorders: A Meta-analysis of 36 Studies. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2011;68:724–731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Frank GK, Shott ME. The Role of Psychotropic Medications in the Management of Anorexia Nervosa: Rationale, Evidence and Future Prospects. CNS Drugs. 2016;30:419–442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Walsh BT, Kaplan AS, Attia E, Olmsted M, Parides M, Carter JC, Pike KM, Devlin MJ, Woodside B, Roberto CA, Rockert W. Fluoxetine after weight restoration in anorexia nervosa: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2006;295:2605–2612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Attia E, Haiman C, Walsh BT, Flater SR. Does fluoxetine augment the inpatient treatment of anorexia nervosa? Am J Psychiatry. 1998;155:548–551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dally PJ, Sargant W. A new treatment of anorexia nervosa. Br Med J. 1960;1:1770–1773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vandereycken W Neuroleptics in the short-term treatment of anorexia nervosa. A double-blind placebo-controlled study with sulpiride. Br J Psychiatry. 1984;144:288–292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vandereycken W, Pierloot R. Pimozide combined with behavior therapy in the short-term treatment of anorexia nervosa. A double-blind placebo-controlled cross-over study. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1982;66:445–450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Frank GK, Bailer UF, Henry SE, Drevets W, Meltzer CC, Price JC, Mathis CA, Wagner A, Hoge J, Ziolko S, Barbarich-Marsteller N, Weissfeld L, Kaye WH. Increased dopamine D2/D3 receptor binding after recovery from anorexia nervosa measured by positron emission tomography and [11c]raclopride. Biol Psychiatry. 2005;58:908–912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bissada H, Tasca GA, Barber AM, Bradwejn J. Olanzapine in the treatment of low body weight and obsessive thinking in women with anorexia nervosa: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165:1281–1288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Attia E, Kaplan AS, Walsh BT, Gershkovich M, Yilmaz Z, Musante D, Wang Y. Olanzapine versus placebo for out-patients with anorexia nervosa. Psychol Med. 2011;41:2177–2182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kafantaris V, Leigh E, Hertz S, Berest A, Schebendach J, Sterling WM, Saito E, Sunday S, Higdon C, Golden NH, Malhotra AK. A placebo-controlled pilot study of adjunctive olanzapine for adolescents with anorexia nervosa. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2011;21:207–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brambilla F, Garcia CS, Fassino S, Daga GA, Favaro A, Santonastaso P, Ramaciotti C, Bondi E, Mellado C, Borriello R, Monteleone P. Olanzapine therapy in anorexia nervosa: psychobiological effects. International Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2007;22:197–204 110.1097/YIC.1090b1013e328080ca328031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dold M, Aigner M, Klabunde M, Treasure J, Kasper S. Second-Generation Antipsychotic Drugs in Anorexia Nervosa: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Psychother Psychosom. 2015;84:110–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.APA: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed, Text Revision. Washington, D.C., American Psychiatric Association Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 17.First M, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Janet BW. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Disorders. 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goodman WK, Price LH, Rasmussen SA, Mazure C, Fleischmann RL, Hill CL, Heninger GR, Charney DS. The Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale. I. Development, use, and reliability. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1989;46:1006–1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goodman WK, Price LH, Rasmussen SA, Mazure C, Delgado P, Heninger GR, Charney DS. The Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale. II. Validity. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1989;46:1012–1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fairburn CG, Cooper PJ: The Eating Disorder Examination. in Binge Eating: Nature, Assessment, and Treatment. Edited by Fairburn CG, Wilson GT. New York, Guilford Press; 1993. pp. 317–360. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zung WWK. A rating instrument for anxiety disorders Psychosomatics (Washington, DC: ). 1971;12:371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lane RD, Glazer WM, Hansen TE, Berman WH, Kramer SI. Assessment of tardive dyskinesia using the Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1985;173:353–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hernan MA, Robins JM. Per-Protocol Analyses of Pragmatic Trials. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:1391–1398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shear MK, Reynolds CF 3rd, Simon NM, Zisook S, Wang Y, Mauro C, Duan N, Lebowitz B, Skritskaya N. Optimizing Treatment of Complicated Grief: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2016;73:685–694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Halmi KA, Agras WS, Crow S, Mitchell J, Wilson GT, Bryson SW, Kraemer HC. Predictors of treatment acceptance and completion in anorexia nervosa: implications for future study designs. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:776–781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zerwas S, Larsen JT, Petersen L, Thornton LM, Mortensen PB, Bulik CM. The incidence of eating disorders in a Danish register study: Associations with suicide risk and mortality. J Psychiatr Res. 2015;65:16–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pompili M, Baldessarini RJ, Forte A, Erbuto D, Serafini G, Fiorillo A, Amore M, Girardi P. Do Atypical Antipsychotics Have Antisuicidal Effects? A Hypothesis-Generating Overview. Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lieberman JA, Stroup TS, McEvoy JP, Swartz MS, Rosenheck RA, Perkins DO, Keefe RS, Davis SM, Davis CE, Lebowitz BD, Severe J, Hsiao JK, Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness I. Effectiveness of antipsychotic drugs in patients with chronic schizophrenia. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:1209–1223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.