Abstract

Autotrophs form the base of all complex food webs and seemingly have done so since early in Earth history. Phylogenetic evidence suggests that early autotrophs were anaerobic, used CO2 as both an oxidant and carbon source, were dependent on H2 as an electron donor, and used iron-sulfur proteins (termed ferredoxins) as a primary electron carrier. However, the reduction potential of H2 is not typically low enough to efficiently reduce ferredoxin. Instead, in modern strictly anaerobic and H2-dependent autotrophs, ferredoxin reduction is accomplished using one of several recently evolved enzymatic mechanisms, including electron bifurcating and coupled ion translocating mechanisms. These observations raise the intriguing question of why anaerobic autotrophs adopted ferredoxins as central electron carriers only to have to evolve complex machinery to reduce them. Here, we report calculated reduction potentials for H2 as a function of observed environmental H2 concentration, pH and temperature. Results suggest that a combination of alkaline pH and high H2 concentration yield H2 reduction potentials low enough to efficiently reduce ferredoxins. Hyperalkaline, H2 rich environments have existed in discrete locations throughout Earth history where ultramafic minerals are undergoing hydration through the process of serpentinization. These results suggest that serpentinizing systems, which would have been common on early Earth, naturally produced conditions conducive to the emergence of H2-dependent autotrophic life. The primitive process of hydrogenotrophic methanogenesis is used to examine potential changes in methanogenesis and Fd reduction pathways as these organisms diversified away from serpentinizing environments.

This article is part of a discussion meeting issue ‘Serpentinite in the earth system’.

Keywords: ferredoxin, hydrogen, autotroph, methanogen, serpentinization, ultramafic

1. Introduction

Ferredoxins (Fds) are ubiquitous in biology and link oxidation and reduction reactions in a diversity of metabolisms, including those of anaerobes, aerobes, phototrophs, chemotrophs, autotrophs and heterotrophs [1]. These small soluble proteins have active sites composed of iron–sulfur (Fe–S) clusters (i.e. 2Fe-2S or 4Fe-4S clusters) [2] that can accept or donate electrons with a concomitant change in the oxidation state of the iron atom(s) between + 2 and +3. These proteins have been widely argued to be among the most primitive of electron carriers [3]. The electrochemical potential of Fe–S clusters, including those of Fds, can range from −0.60 to +0.50 V [4], thereby encompassing the array in potentials associated with oxidation–reduction reactions that fuel life in reduced environments reminiscent of those on early Earth as well as oxidized environments that characterize surface locales on modern Earth [5].

Genes encoding Fds are enriched in the genomes of anaerobes relative to aerobes and facultative anaerobes [6], a finding that is consistent with the central role of Fds in anaerobic energy metabolism [7]. This is particularly true for the genomes of strictly anaerobic, hydrogenotrophic methanogens [6], a group of organisms often advocated as having the most primitive of extant metabolisms [8,9]. Rationales for the primacy of hydrogenotrophic methanogens are manifold. Firstly, isotopic analysis of methane in fluid inclusions in ancient rocks dated to approximately 3.46 Ga suggest the presence of ancestors of methanogens at this time [10] and phylogenetic data suggest that these ancestral cells were likely dependent on H2 as electron donor [9,11]. Secondly, hydrogenotrophic methanogens can use CO2 as their sole source of carbon as well as their electron acceptor, resulting in the production of methane (CH4). This potentially alleviated a major barrier for early autotrophic life since CO2 was likely widely available on a volcanically active early Earth while organic carbon and other potential oxidants (e.g. oxygen, nitrate, sulfate) capable of supporting life are likely to have been far less available [12]. Finally, methanogens rely on the reductive acetyl CoA pathway, or the Wood Ljungdahl (WL) pathway [8], for carbon fixation. The WL pathway forms acetyl CoA from CO2 in an overall thermodynamically favourable reaction [13] and has been suggested to be the most ancestral of extant carbon fixation pathways [8,9]. Thus, methanogens and other early evolving organisms that use the WL pathway (e.g. acetogens) do not expend the limited energy supplied by their primitive anaerobic metabolisms to generate reduced carbon like other autotrophs operating less efficient pathways.

The typical Fds involved in the energy metabolism of hydrogenotrophic methanogens and acetogens are highly reduced, having standard state (25°C, pH 7.0, 1 M reactant and product concentrations) reduction potentials (E°) relative to the standard hydrogen electrode of approximately −0.41 to −0.50 V [14,15]. This is possibly a consequence of selection to harbour an Fe–S cluster with a low enough potential to allow for the initial reduction of CO2, which is estimated to be approximately −0.50 V [16]. However, the E°’ of H2, the source of electrons supporting the energy metabolism of these cells and organic carbon synthesis via the WL pathway, is approximately −0.41 V [17,18], which is not of low enough potential to efficiently reduce the Fe–S cluster(s) in low potential Fd (Reaction 1).

| Reaction 1 |

This is particularly true considering that Fd in cells is generally 90% reduced [19], thus favouring preservation of reactants.

Nonetheless, numerous anaerobic, hydrogenotrophic methanogens and acetogens have been characterized in laboratory and natural settings (e.g. [17,20]). How do contemporary anaerobic cells reduce low potential Fd with H2 as an electron carrier? At least two distinct enzymatic mechanisms have evolved to overcome this thermodynamic barrier in H2 oxidizing anaerobic autotrophs: electron bifurcating Fd reduction and ion (proton or sodium) translocating Fd reduction [7,14]. Electron bifurcation involves the endergonic reduction of low potential Fd by an electron donor with a higher potential. This is only possible when the same donor is also coupled to concomitant exergonic oxidation by an even higher potential acceptor [17,18]. Twelve multimeric bifurcating enzyme complexes have been described to date and all are involved in the reduction of Fd; however, only three of these multimeric complexes are known to use H2 as the hydride donor [7,15,21]. These include the trimeric/tetrameric [FeFe]-hydrogenases, the hexameric [FeFe]-hydrogenase-CO2 reductase and the hexameric [NiFe]-hydrogenase-heterodisulfide reductase (Mvh-Hdr). In ion translocating Fd reduction, the unfavourable thermodynamics associated with Fd reduction with H2 are overcome by coupling the chemical reaction to depletion of an electrochemical ion (i.e. sodium ion or proton) gradient across a membrane [7]. Two classes of membrane-bound enzyme complexes are known to catalyse this function: the energy converting [NiFe]-hydrogenases (Ech or Eha/Ehb) and the Fd:NAD+ oxidoreductase (Rnf). Both complexes couple the reversible reduction of Fd and oxidation of H2 (Ech/Eha/Ehb) or NADH (Rnf) with the translocation of sodium ions or protons into the cell [22–24].

Based on the fundamental role of electron bifurcating complexes and ion translocating Fd oxidoreductase enzymes in the energy metabolism of hydrogenotrophic methanogenic or acetogenic anaerobes [7], these enzymes or processes are often advocated as having been integrated into the energy metabolism of primitive lifeforms on early Earth [25–27]. In support of this hypothesis, the genomes of hydrogenotrophic acetogens and methanogens that could be classified based on previous physiological characterization encode one or more H2-dependent electron bifurcating or ion translocating Fd oxidoreductase enzyme homologs (electronic supplementary material, table S1). However, a recent analysis of the taxonomic distribution and evolutionary history of bifurcating enzymes revealed that none of the twelve known bifurcating complexes are likely to have been a property of the Last Universal Common Ancestor (LUCA) of Archaea and Bacteria [28]. Rather, evidence suggests that the twelve known bifurcating complexes emerged independently multiple times after the divergence of Archaea and Bacteria from the LUCA. Likewise, phylogenetic analyses of Ech/Eha/Ehb suggest that these enzymes are likely to have emerged in methanogenic Archaea after their divergence from LUCA, with acquisition among Bacteria taking place more recently [11]. Finally, Rnf enzymes are found in several lineages of anaerobic Bacteria but are only found in several late diverging methanogenic Archaea (e.g. Methanosarcinales; [23]) and are absent in more ancestral methanogens (e.g. Methanococcales, Methanobacteriales; electronic supplementary material, table S1), suggesting that they too may be recently evolved. Collectively, these observations raise key new questions regarding how Fd was reduced in ancestral, autotrophic and anaerobic cells such as methanogens prior to the advent of complex mechanisms that allow for its reduction in contemporary cells.

Here, we provide thermodynamic calculations of the potential of Fd and H2 across a range of environmental conditions to identify those that may be suitable for direct reduction of Fd with H2 in early evolving anaerobic autotrophs in the absence of bifurcating or ion-translocating hydrogenases. Results are discussed at the level of the possible ancestral pathways that enabled autotrophy in early evolving hydrogenotrophic anaerobes and the role of ion-translocating and bifurcating hydrogenases in the diversification of ancestors of anaerobic, H2-dependent autotrophs away from environmental realms that may have favoured the direct reduction of Fd with H2.

2. Material and methods

(a). Relationship between the mode of carbon metabolism and distribution of bifurcating enzyme homologs

A database of organisms with complete genomes (n = 4,588) created in our previous analysis of the taxonomic distribution on bifurcating enzyme homologs [28] was subjected to classification of their ability to integrate oxygen into their energy metabolism based on information acquired from the Department of Energy's Integrated Microbial Genomes and Microbiomes (DOE-IMG). All identified anaerobic taxa were further characterized as hydrogen oxidizing autotrophic acetogens or methanogens based on the available literature (electronic supplementary material, table S1). This curated list of organisms was then cross-referenced with our published database describing the distribution of bifurcating enzyme homologs in their genomes [28]. In addition, the genomes of these organisms were screened for homologs of ferredoxin:NAD+ oxidoreductase (Rnf) and the group 4 membrane-bound [NiFe]-hydrogenase (Ech/Eha/Ehb). Briefly, Rnf protein homologs from Azotobacter vinelandii (ACO81179-ACO81185) and a homolog of the large subunit of group 4 [NiFe]-hydrogenase from Pyrococcus abyssi (WP_010867842) were subjected to analysis via phmmer available in the HMMER (v.3) software package (hmmer.org) to extract protein homologs. Extracted homologs of [NiFe]-hydrogenases were aligned using Clustal Omega [29] and filtered to contain the conserved residues that demarcate these enzymes as identified in a previous study [30].

(b). Redox potential calculations

The ability of a compound to donate or accept electrons is dictated by its redox potential (E), which can be calculated using equation (2.1):

| 2.1 |

where E° represents the standard redox potential of reaction in volts (V), R designates the ideal gas constant (approx. 8.314 J mol−1 K−1), T is the temperature in Kelvin (K), n is the number of electrons transferred in the reaction, F is the Faraday constant (approx. 96 485 J V−1 mol−1), αOx is the activity of the oxidized form of the compound and αRed is the activity of the reduced form. Redox potential calculations for H2 were performed across a range of H2 activities (0.0001 to 10 mM), temperatures (0 to 100°C) and pH values (4.0; 7.0; 10) using equation (2.1). In addition, the redox potential of H2 in natural environments was calculated using reported (electronic supplementary material, table S2) dissolved H2 concentrations, temperatures and pH values. Activity coefficients were assumed equal to one for all dissolved compounds (activity = concentration) since the ionic strength was not always reported.

3. Results and discussion

The non-standard state electrochemical potential (E) of a half-reaction is dependent on how the E° is modified by temperature, pressure, and the concentrations of reactants and products. In the case of the half-reaction describing the oxidation of H2 (Reaction 2), the potential is dependent on pH since protons (H+) are a product of the specified reaction. Thus, the potential of H2 (thermodynamic drive toward products) will be lower in environments with lower H+ activity.

| Reaction 2 |

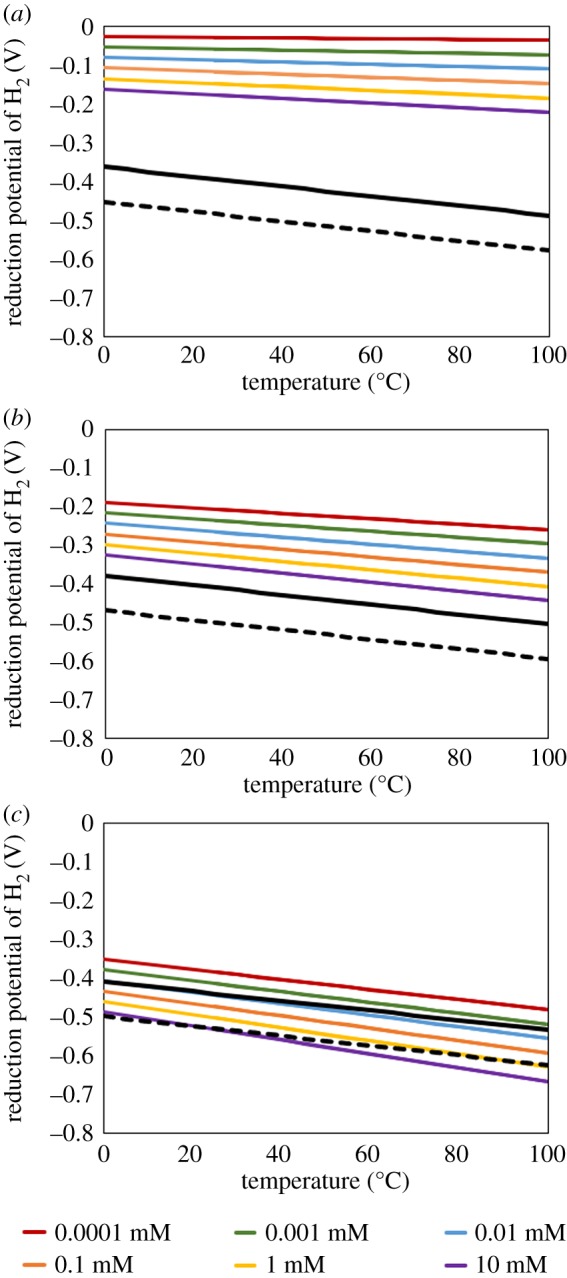

Using thermodynamic data, we calculated the E of the half-reaction describing the oxidation of H2 (Reaction 2, hereafter referred to as the potential of H2) as a function of temperature, proton concentration (i.e. pH), and H2 concentration to identify conditions that may be conducive to the direct reduction of low potential Fds associated with anaerobic autotrophs (E° = −0.41 to −0.50 V at pH 7.0, 25°C), both today and in the geological past. To facilitate comparison of Fd reduction potentials relative to Reaction 1, we also calculated the E of Fds across a range of temperatures and pH (figure 1). The temperature dependence of the E of Fds (E° = −0.41 to −0.50 V) was calculated by extrapolating measurements of Fd purified from Pyrococcus furiosus as a function of temperature (−0.00123 V/°C) [31]. The pH dependence of the E of Fds was calculated by extrapolating the maximum measured effect of pH on the measured E of Fd (0.030 V/pH unit) [32] purified from a variety of taxa (range = 0.002 to 0.030 V/pH unit) [32–34]. These calculations assumed a single electron transfer per Fd (Reaction 1) since ancestral Fds are thought to have comprised a single Fe–S cluster [3] and assumed a constant concentration of Fd (1 M). Importantly, ionic strength has also been shown to influence the E of purified Fd [34]. However, the inverse relationship between ionic strengths ranging from 0 (slightly lower than freshwater) to 1.0 (greater than seawater) and the measured E of Fd is minimal (0.061 V) and is therefore not considered further in the calculations presented here.

Figure 1.

Reduction potential of H2 (Reaction 1) as a function of temperature and H2 concentration in water with a pH of 4.0 (a), 7.0 (b) and 10.0 (c). The black line in each panel depicts the calculated midpoint potential of Fds with an E°′ of −0.41 V while the dashed black line in each panel depicts the calculated midpoint potential of Fds with an E°′ of −0.50 V. Calculations of the midpoint potential of Fds assumed a concentration of 1 M. The temperature and pH dependence of the midpoint potentials calculated for Fds were assumed to be 0.00123 V/°C [31] and 0.030 V/ pH unit [32], respectively. (Online version in colour.)

The calculated E of H2 dissolved in water with a pH of 4.0, when considered over a range of dissolved H2 concentrations from 100 nM to 10 mM and temperatures from 0 to 100°C, ranged from −0.03 V to −0.22 V (figure 1a). More negative potentials were associated with higher concentrations of dissolved H2 and higher temperature; the effects of these parameters were additive. In water with a pH of 7.0 and over the same range of dissolved H2 concentrations and temperatures, the E of H2 varied from −0.19 V to −0.44 V with more negative potentials in solutions with higher concentrations of dissolved H2 and higher temperature (figure 1b). Finally, dissolved H2 in water with a pH of 10.0 and over the same range of dissolved H2 concentrations and temperatures had calculated E that ranged from −0.35 V to −0.67 V (figure 1c). In water with a pH of 10.0, the calculated E of H2 at a concentration of greater than 1 mM would be low enough to efficiently reduce low potential Fd (E° = −0.41 V) at temperatures greater than 25°C. The reduction of lower potential Fd (E° = −0.50 V) at pH 10.0 requires higher H2 concentrations (greater than 10 mM) and temperatures (greater than 100°C). As previously mentioned, the relationship between the E of Fd and pH was calculated using the maximum measured inverse slope of 0.030 V/pH unit. Thus, it is possible that efficient reduction of low potential Fds could take place in a setting with a lower pH, temperature, and H2 concentration than those specified above. Alternatively, it is possible that the potential of Fds vary with pH in a more Nernstian-like manner, whereby a decrease in the potential of 0.059 V/pH unit would be expected. If so, a higher concentration of H2, a higher pH, and/or temperature would be required to reduce low potential Fds than those specified above.

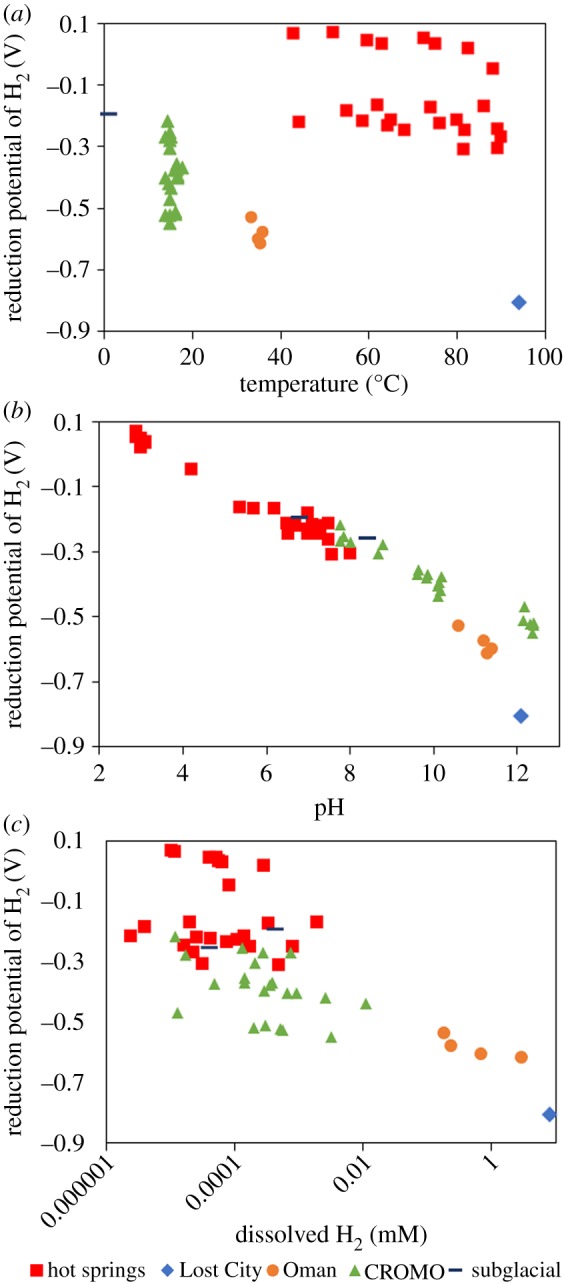

To identify environmental types with conditions that may support efficient reduction of low potential Fds, the dissolved H2 concentrations (range = 2.3 nM–2.9 mM), temperatures (range = 0.4–90.0°C), and pH values (range = 2.9–12.4) of waters from various early Earth analogue environments that had temperatures less than 122°C, the current upper temperature limit for life [35], were compiled (electronic supplementary material, table 2). These environments were chosen because of (i) available temperature, pH and H2 concentration data, (ii) their potential to host non-photosynthetic, chemosynthetic cells thought to reflect the earliest forms of life [9,11] and (iii) previous suggestions of their relevance as habitats supporting descendants of early forms of life [36–40]. The following environment types met these criteria: marine and terrestrial hydrothermal springs, subglacial environments overlying basalt bedrock, and marine and terrestrial subsurface environments where water is in contact with ultramafic rocks (i.e. serpentinites).

The calculated E of H2, when plotted as function of temperature (figure 2a), pH (figure 2b) or H2 concentration (figure 2c), from a variety of environments identified natural conditions that could conceivably favour the efficient direct reduction of low potential Fd with H2. These include subsurface fluids in contact with ultramafic rocks in the Coast Range Ophiolite Microbial Observatory (CROMO) in the USA (green triangles), the Samail Ophiolite in the Sultanate of Oman (orange dots), and the Lost City hydrothermal field in the Atlantic Ocean (blue diamonds). Common to each of these three environmental types is a combination of alkaline pH (figure 2b) and high H2 concentration (figure 2c) that span a range of temperatures (figure 2a). The alkaline pH and elevated H2 concentrations in each of these environment types is due to hydration of ultramafic rock rich in olivine and pyroxene, which stimulates a series of reactions collectively known as serpentinization that generate hydroxide ions and molecular H2 [41]. The process of serpentinization is thought to have been more prevalent on early Earth where highly reduced mineralogy was likely more widespread in an undifferentiated crust [36,42]. In turn, and as shown here, hyperalkaline, H2-rich conditions are potentially conducive to the direct and efficient reduction of Fd in anaerobic autotrophs if suitable catalysts are available, leading to the suggestion that serpentinizing systems hosted the earliest evolving, Fd- and H2-dependent anaerobic autotrophs.

Figure 2.

Reduction potential of H2 (Reaction 1) in early Earth analogue natural environmental samples as a function of temperature (a), pH (b) and H2 concentration (c). H2 concentrations, pH, temperatures and calculated E for H2 are presented in electronic supplementary material, table S2. (Online version in colour.)

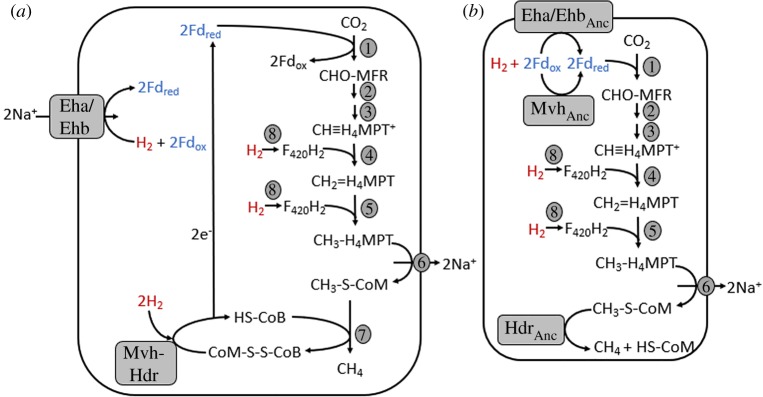

The primary catalysts or enzymes involved in the reversible oxidation of H2 in modern cells are [FeFe]- and [NiFe]-hydrogenases. While [FeFe]-hydrogenases are unlikely to be a property of the LUCA [43], [NiFe]-hydrogenase have been suggested to have been associated with the LUCA where they likely functioned in H2 oxidation [9,11]. It is worth noting that both Fe and Ni, the metals that form the active site of [NiFe]-hydrogenase, are common components of serpentinite rocks [36]. H2 oxidation via [NiFe]-hydrogenases in contemporary hydrogenotrophic methanogens occurs in the cytoplasm (figure 3) [17], and this may have also been true for ancestors of these cells. If primordial hydrogenases were also localized in the cytoplasm, the calculations presented above must be modified to accommodate shifts in the reduction potential of H2 when it is oxidized within the cell. This is because contemporary cells tend to maintain or buffer the pH of the cytoplasm within a narrower range than the pH outside the cell [44] but cannot regulate temperature or H2 concentration. The same is likely to be true for primitive autotrophic cells.

Figure 3.

A simplified depiction (a) of the energy metabolism of contemporary hydrogenotrophic methanogens as modified from Thauer et al. [17] and the linear pathway (b) as proposed herein for the ancestor of hydrogenotrophic methanogens. The bifurcating Mvh-Hdr and the ion translocating Eha/Ehb[NiFe]-hydrogenases are depicted, as is the proposed non-bifurcating ancestor of Mvh (MvhAnc). Enzymes and their enzyme category numbers (EC) shown as numbers are as follows: 1, formylmethanofuran (MFR) dehydrogenase (EC: 1.2.7.12); 2, formylmethanofuran:tetrahydromethanopterin (H4MPT) formyltransferase (EC: 2.3.1.101); 3, Methenyltetrahydromethanopterin cyclohydrolase (EC: 3.5.4.27); 4, F420H2-dependent methylenetetrahydromethanopterin dehydrogenase (EC: 1.5.98.1); 5, coenzyme F420-dependent N5,N10 methylenetetrahydromethanopterin reductase (EC: 1.5.98.2); 6, methyl-H4MPT–coenzyme M methyltransferase (EC 2.1.1.86); 7, methyl coenzyme M reductase (EC 2.8.4.1); 8, coenzyme F420 reducing [NiFe]-hydrogenase (EC 1.12.98.1). Enzyme abbreviations are as follows: Eha/EhbAnc, the putative ancestor of energy converting [NiFe]-hydrogenase (Eha/Ehb); MvhAnc, the ancestor of soluble [NiFe]-hydrogenase (Mvh); HdrAnc, the ancestor of soluble heterodisulfide reductase (Hdr). Fds are assumed to accept a single electron in the schematics. (Online version in colour.)

Hyperalkaliphiles maintain a cytoplasmic pH that is up to 2 units lower than that of their external environment [44], which would increase the E of H2 as it diffuses into the cell. As an example, for a cell inhabiting a pH 12.0 environment (assumed cytoplasmic pH of 10.0) at 25°C to efficiently reduce low potential Fds with E° of −0.41 V (E = −0.50 V) and −0.50 V (E = −0.59 V), H2 would need to be at a concentration of 1 mM and 1 M, respectively. Again, these are likely maximum H2 concentrations required based on the assumed relationship between E and pH (0.030 V/pH unit). Environments enriched in ultramafic minerals and undergoing active low-temperature serpentinization generate water with strongly alkaline pH, concentrations of H2 that approach 10 mM, and are often at temperatures that exceed 25°C (i.e. Oman, Lost City; figure 2). However, based on available data, it is unclear whether a cytoplasmic pH of 10.0 is physiologically feasible in an autotroph since available CO2 would speciate to carbonate which has a low solubility and is not the carbon source for methanogenesis [17]. That said, methanogens have been grown with calcium or magnesium carbonate as their sole carbon source [45] in growth medium with a pH as high as 10.0 [46]. These organisms grow presumably by consuming CO2 that had equilibrated in solution [45]. Moreover, putatively hydrogenotrophic methanogens have been detected in several environments undergoing active serpentinization [47], including well waters sampled from the Samail Ophiolite in Oman with pH of up to 11.3 [48,49]. This indicates that the low solubility of inorganic carbon in hyperalkaline environments and constraints that it imposes on the availability of CO2 can be overcome, at least in modern methanogen cells.

Primitive autotrophic, H2-dependent cells also faced the need to innovate mechanisms to shuttle electrons that minimized energy loss and that had potentials close to the H2/H+ redox couple. Low potential Fds would efficiently meet this need in environments where the E of H2 was more reduced, such as in alkaline hydrothermal vents or other environments with ultramafic rocks that are undergoing active serpentinization. As a modern example, the calculated E of H2 in fluids from hydrothermal vents at Lost City (pH 12.1, [H2] = 7.8 mM, 94°C; electronic supplementary material, table S2) is −0.73 V (figure 2) or −0.66 V at a cytoplasmic pH of 10.0. These values are close to the calculated E of a typical anaerobic Fd, which is estimated to range from −0.58 to −0.67 V at 95°C at a cytoplasmic pH of 10.0. Importantly, it is also likely that ancestral Fds comprised a far simpler protein environment than contemporary Fds [3], perhaps consisting of as few as 7 amino acids [50,51]. Fe–S clusters in such primitive Fds would presumably be more solvent exposed, which in turn would be expected to poise their E more positive than contemporary anaerobic Fds [4]. This, in turn, may have allowed early autotrophic anaerobes to exploit H2 as an electron donor in a broader range of environments where reduction of these primitive Fds was favourable, including those with lower H2 concentrations or with slightly less alkaline pH where inorganic carbon would have been more bioavailable. However, as depicted in figures 1 and 2, environments with temperature, pH, and H2 conditions that may have been favourable for the reduction of low potential Fds represent only a fraction of those that were likely available on early Earth. We suggest that the emergence of complex enzymes enabling electron bifurcating Fd reduction and ion (proton or sodium) translocating Fd reduction [7,14] was triggered by the diversification of anaerobic life away from environments that favoured efficient and direct Fd reduction and into environments where the thermodynamics and kinetics of Fd reduction with H2 were less favourable. These would have included environments with lower H2 concentrations, lower temperatures, less alkaline pH or a combination of these factors.

The emergence of electron bifurcating and ion-translocating [NiFe]-hydrogenase enzymes was accomplished by recruitment of flavoprotein/heterodisulfide reductase [28] and ion transporter modules [11], respectively, thereby providing a mechanism to reduce Fd and meet the bioenergetic needs of early anaerobic autotrophs in environments less favourable for direct and efficient enzymatic reduction of Fd with H2. A likely consequence of these diversifications is the presence of electron bifurcating and/or ion-translocating [NiFe]-hydrogenase enzyme homologs involved in reversible H2 oxidation in the genomes of all anaerobic H2 oxidizing methanogens and acetogens (electronic supplementary material, table S1), suggesting that such mechanisms are obligate in these derived cells. It remains to be determined if anaerobic H2-dependent methanogens or acetogens that lack genes coding for bifurcating and ion-translocating enzymes can be found in contemporary environments undergoing active serpentinization (i.e. Lost City or the Samail Ophiolite, Oman), or if approximately 3.8 Ga of evolution has erased all vestiges of these ancestral organisms. Further cultivation efforts focused on such organisms from environments with high pH and high H2 concentrations are necessary to address this question directly. Alternatively, it may be possible to evaluate this question by reconstructing the metabolisms of difficult to cultivate methanogens or acetogens through assembly and binning of metagenomic sequence data followed by robust informatics and evolutionary analyses.

What might such an ancestral anaerobic H2 oxidizing methanogen or acetogen cell comprise? If the hypothesis that bifurcating and ion-translocating [NiFe]-hydrogenase enzymes were not components of the progenitors of anaerobic autotropic cells [28] turns out to be correct and that these early autotrophic cells harboured metabolisms with characteristics that are reminiscent of contemporary H2-dependent methanogens [9], a very different picture of the metabolism of primitive hydrogenotrophic methanogens emerges. Whereas the pathway of contemporary hydrogenotrophic methanogenesis is cyclic with the first and last steps linked by the oxidation and reduction of low potential Fd, respectively (figure 3a) [17], it is possible that an earlier version of this pathway was not cyclic but rather linear where the first and last steps were unlinked. For example, in the last step of hydrogenotrophic methanogenesis, soluble bifurcating Mvh-Hdr functions to couple the oxidation of H2 with the simultaneous endergonic reduction of Fd and heterodisulfide in coenzyme M-coenzyme B (CoM-CoB); the reduced Fd that is generated is then used to drive the exergonic reduction of CO2 and methanofuran to form N-formylmethanofuran [17]. Membrane-associated ion-translocating [NiFe]-hydrogenase enzymes (Ech/Eha/Ehb) function to supply additional reduced Fd for the initial reduction of CO2 to form N-formylmethanofuran [17]. In an early Earth environment that favoured the direct reduction of Fd with H2, a soluble [NiFe]-hydrogenase without bifurcating functionality (termed MvhAnc) could conceivably generate reduced Fd without coupling it to the reduction of CoM-CoB; CoM-CoB reduction could have been catalysed by a soluble heterodisulfide reductase (HdrAnc) (figure 3b). A membrane bound [NiFe]-hydrogenase without ion-translocating capabilities (termed Eha/EhbAnc) could have conceivably also supplied additional reduced Fd via direct reduction with H2 (figure 3b), although it is unclear if such an enzyme would provide a selective advantage to a cell where MvhAnc was also present. As such, this putative ancestral methanogenesis pathway would be linear rather than cyclic. Moreover, the eventual emergence of bifurcating enzymes would help to explain the evolution of the cyclic pathway of methanogenesis that we see perpetuated in extant hydrogenotrophic methanogens from a simpler linear pathway in a manner similar to that proposed for the Kreb's cycle [52].

An origin for autotrophic life in an anoxic, alkaline environment undergoing active serpentinization, as suggested by the data presented here, is consistent with other data suggesting these environment types may have been conducive to the origin of autotrophic cells. For such cells to originate, they would have needed a constant source of chemically transducible energy, a requirement that is met in the form of abundant H2 in environments undergoing active serpentinization [42] and/or in the form of naturally occurring proton gradients when serpentinized fluids (pH ∼ 10–11) mix with ocean waters in equilibrium with atmospheric CO2 (pH ∼ 6) [37]. Likewise, electrons of sufficiently reduced potential would have needed to be efficiently captured for use in the reduction of CO2 [15,17], a problem that is potentially overcome by H2 oxidizing, Fd-reducing [NiFe]-hydrogenases and the low potentials associated with H2 in hyperalkaline serpentinizing systems (figure 2). However, the hyperalkaline pH also presents a potential problem for primitive autotrophic cells since CO2 speciates towards carbonate which is less bioavailable. Contemporary hydrogenotrophic methanogens, however, are capable of growth at pH of up to 10.0 [45,46] and have been detected in serpentinizing environments with even more alkaline pH (11.3) [48,49]; the same may have been true for their ancestors. It is possible that in such modern environments, autotrophic cells overcome limitations of inorganic carbon by using more soluble and hydrogenated forms of carbon such as carbon monoxide or formate, which can also be produced abiotically from H2 and under serpentinizing conditions [53]. Indeed, formate has been detected in natural serpentinizing environments such as Lost City [54] and in Oman [48]. Under formatotrophic methanogenic growth conditions, oxidation of low potential H2 may simply augment the metabolism of these autotrophic cells. Collectively, the characteristics of environments undergoing active serpentinization make them attractive targets for understanding the possible origin of autotrophic metabolism, and perhaps metabolism in general. The ideas presented here are testable by probing extant life inhabiting alkaline serpentinite hosted, H2 rich environments via biochemical, genetic and physiological approaches and through metabolic reconstructions enabled by phylogenomic approaches.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Tori Hoehler and Mike Kubo for use of unpublished CROMO geochemical data. We thank Gerrit Schut, Eric Shepard, Robert Szilagyi and Eric Roden for numerous insightful discussions related to the ideas presented herein.

Data accessibility

All data presented herein are available in electronic supplementary material or through communication with the authors.

Authors' contributions

E.S.B., M.J.A. and A.S.T. designed the study. S.P. conducted informatics analyses. All authors contributed to data analysis and interpretation, manuscript preparation and approve of the version to be published.

Competing interests

We have no competing interests.

Funding

This work was supported as part of the Rock Powered Life NASA Astrobiology Institute funded by the National Aeronautics and Space Administration under award no. NNA15BB02A and the Biological Electron Transfer and Catalysis Energy Frontier Research Center funded by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science and Basic Energy Sciences under award no. DE-SC0012518.

References

- 1.Meyer J. 1988. The evolution of ferredoxins. Trends Ecol. Evol. 3, 222–226. ( 10.1016/0169-5347(88)90162-0) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bruschi M, Guerlesquin F. 1988. Structure, function and evolution of bacterial ferredoxins. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 54, 155–175. ( 10.1016/0378-1097(88)90175-9) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eck RV, Dayhoff MO. 1966. Evolution of the structure of ferredoxin based on living relics of primitive amino acid sequences. Science 152, 363–366. ( 10.1126/science.152.3720.363) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dey A, Jenney FE Jr, Adams MW, Babini E, Takahashi Y, Fukuyama K, Hodgson KO, Hedman B, Solomon EI. 2007. Solvent tuning of electrochemical potentials in the active sites of HiPIP versus ferredoxin. Science 318, 1464–1468. ( 10.1126/science.1147753) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lyons TW, Reinhard CT, Planavsky NJ. 2014. The rise of oxygen in Earth's early ocean and atmosphere. Nature 506, 307–315. ( 10.1038/nature13068) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Major TA, Burd H, Whitman WB. 2004. Abundance of 4Fe-4S motifs in the genomes of methanogens and other prokaryotes. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 239, 117–123. ( 10.1016/j.femsle.2004.08.027) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Buckel W, Thauer RK. 2018. Flavin-based electron bifurcation, ferredoxin, flavodoxin, and anaerobic respiration with protons (Ech) or NAD+ (Rnf) as electron acceptors: a historical review. Front. Microbiol. 9, 401 ( 10.3389/fmicb.2018.00401) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Russell MJ, Martin W. 2004. The rocky roots of the acetyl-CoA pathway. Trends Biochem. Sci. 29, 358–363. ( 10.1016/j.tibs.2004.05.007) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weiss MC, Sousa FL, Mrnjavac N, Neukirchen S, Roettger M, Nelson-Sathi S, Martin WF. 2016. The physiology and habitat of the last universal common ancestor. Nat. Microbiol. 1, 16116 ( 10.1038/nmicrobiol.2016.116) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ueno Y, Yamada K, Yoshida N, Maruyama S, Isozaki Y. 2006. Evidence from fluid inclusions for microbial methanogenesis in the early Archaean era. Nature 440, 516–519. ( 10.1038/nature04584) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boyd ES, Schut G, Adams MWW, Peters JW. 2014. Hydrogen metabolism and the evolution of respiration. Microbe 9, 361–367. ( 10.1128/microbe.9.361.1) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moore EK, Jelen BI, Giovannelli D, Raanan H, Falkowski PG. 2017. Metal availability and the expanding network of microbial metabolisms in the Archaean eon. Nat. Geosci. 10, 629–636. ( 10.1038/ngeo3006) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fuchs G. 1994. Variations of the acetyl-CoA pathway in diversely related microorganisms that are not acetogens. In Acetogenesis (ed. Drake HL.), pp. 506–538, Chapman and Hall; ( 10.1007/978-1-4615-1777-1_19) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Buckel W, Thauer RK. 2013. Energy conservation via electron bifurcating ferredoxin reduction and proton/Na(+) translocating ferredoxin oxidation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1827, 94–113. ( 10.1016/j.bbabio.2012.07.002) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Muller V, Chowdhury NP, Basen M. 2018. Electron bifurcation: a long-hidden energy-coupling mechanism. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 72, 331–353. ( 10.1146/annurev-micro-090816-093440) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thauer RK. 1998. Biochemistry of methanogenesis: a tribute to Marjory Stephenson. Microbiology (Reading, England) 144, 2377–2406. ( 10.1099/00221287-144-9-2377) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thauer RK, Kaster A-K, Seedorf H, Buckel W, Hedderich R. 2008. Methanogenic archaea: ecologically relevant differences in energy conservation. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 6, 579–591. ( 10.1038/nrmicro1931) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Herrmann G, Jayamani E, Mai G, Buckel W. 2008. Energy conservation via electron-transferring flavoprotein in anaerobic bacteria. J. Bacteriol. 190, 784–791. ( 10.1128/jb.01422-07) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bennett BD, Kimball EH, Gao M, Osterhout R, Van Dien SJ, Rabinowitz JD.. 2009. Absolute metabolite concentrations and implied enzyme active site occupancy in Escherichia coli. Nat. Chem. Biol. 5, 593–599. ( 10.1038/nchembio.186) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Müller V. 2003. Energy conservation in acetogenic bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69, 6345–6353. ( 10.1128/aem.69.11.6345-6353.2003) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Peters JW, Miller AF, Jones AK, King PW, Adams MW. 2016. Electron bifurcation. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 31, 146–152. ( 10.1016/j.cbpa.2016.03.007) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hess V, Schuchmann K, Muller V. 2013. The ferredoxin:NAD+ oxidoreductase (Rnf) from the acetogen Acetobacterium woodii requires Na+ and is reversibly coupled to the membrane potential. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 31 496–31 502. ( 10.1074/jbc.M113.510255) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Biegel E, Schmidt S, Gonzalez JM, Muller V. 2011. Biochemistry, evolution and physiological function of the Rnf complex, a novel ion-motive electron transport complex in prokaryotes. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 68, 613–634. ( 10.1007/s00018-010-0555-8) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hedderich R. 2004. Energy-converting [NiFe] hydrogenases from Archaea and extremophiles: ancestors of complex I. J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 36, 65–75. ( 10.1023/b:jobb.0000019599.43969.33) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Martin WF. 2012. Hydrogen, metals, bifurcating electrons, and proton gradients: the early evolution of biological energy conservation. FEBS Lett. 586, 485–493. ( 10.1016/j.febslet.2011.09.031) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nitschke W, Russell MJ. 2012. Redox bifurcations: mechanisms and importance to life now, and at its origin. Bioessays 34, 106–109. ( 10.1002/bies.201100134) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sousa FL, Preiner M, Martin WF. 2018. Native metals, electron bifurcation, and CO2 reduction in early biochemical evolution. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 43, 77–83. ( 10.1016/j.mib.2017.12.010) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Poudel S, Dunham EC, Lindsay MR, Amenabar MJ, Fones EM, Colman DR, Boyd ES. 2018. Origin and evolution of flavin-based electron bifurcating enzymes. Front. Microbiol. 9, 1762 ( 10.3389/fmicb.2018.01762) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sievers F, et al. 2011. Fast, scalable generation of high-quality protein multiple sequence alignments using Clustal Omega. Mol. Syst. Biol. 7, 539 ( 10.1038/msb.2011.75) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Greening C, Biswas A, Carere CR, Jackson CJ, Taylor MC, Stott MB, Cook GM, Morales SE. 2016. Genomic and metagenomic surveys of hydrogenase distribution indicate H2 is a widely utilised energy source for microbial growth and survival. ISME J. 10, 761–777. ( 10.1038/ismej.2015.153) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hagedoorn PL, Driessen MCPF, van den Bosch M, Landa I, Hagen WR. 1998. Hyperthermophilic redox chemistry: a re-evaluation. FEBS Lett. 440, 311–314. ( 10.1016/S0014-5793(98)01466-5) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Magliozzo RS, McIntosh BA, Sweeney WV. 1982. Origin of the pH dependence of the midpoint reduction potential in Clostridiurn pasteurianum ferredoxin: oxidation state-dependent hydrogen ion association. J. Biol. Chem. 257, 3506–3509. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stombaugh NA, Sundquist JE, Burris RH, Orme-Johnson WH. 1976. Oxidation-reduction properties of several low potential iron-sulfur proteins and of methylviologen. Biochemistry 15, 2633–2641. ( 10.1021/bi00657a024) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lode ET, Murray CL, Rabinowitz JC. 1976. Apparent oxidation-reduction potential of Clostridium acidi-urici ferredoxin. Effect of pH, ionic strength, and amino acid replacements. J. Biol. Chem. 251, 1683–1687. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Takai K, et al. 2008. Cell proliferation at 122°C and isotopically heavy CH4 production by a hyperthermophilic methanogen under high-pressure cultivation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 105, 10 949–10 954. ( 10.1073/pnas.0712334105) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sleep NH, Bird DK, Pope EC. 2011. Serpentinite and the dawn of life. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 366, 2857–2869. ( 10.1098/rstb.2011.0129) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Russell MJ, Hall AJ, Martin W. 2010. Serpentinization as a source of energy at the origin of life. Geobiology 8, 355–371. ( 10.1111/j.1472-4669.2010.00249.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sojo V, Herschy B, Whicher A, Camprubi E, Lane N. 2016. The origin of life in alkaline hydrothermal vents. Astrobiology 16, 181–197. ( 10.1089/ast.2015.1406) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Djokic T, Van Kranendonk MJ, Campbell KA, Walter MR, Ward CR. 2017. Earliest signs of life on land preserved in ca. 3.5 Ga hot spring deposits. Nat. Commun. 8, 15263 ( 10.1038/ncomms15263) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Miyakawa S, James Cleaves H, Miller SL. 2002. The cold origin of life: A. implications based on the hydrolytic stabilities of hydrogen cyanide and formamide. Orig. Life Evol. B. 32, 195–208. ( 10.1023/A:1016514305984) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bach W, Paulick H, Garrido CJ, Ildefonse B, Meurer WP, Humphris SE. 2006. Unraveling the sequence of serpentinization reactions: petrography, mineral chemistry, and petrophysics of serpentinites from MAR 15°N (ODP Leg 209, Site 1274). Geophys. Res. Lett. 33, L13306 ( 10.1029/2006GL025681) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schulte M, Blake D, Hoehler T, McCollom T. 2006. Serpentinization and its implications for life on the early Earth and Mars. Astrobiology 6, 364–376. ( 10.1089/ast.2006.6.364) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mulder DW, Boyd ES, Sarma R, Lange RK, Endrizzi JA, Broderick JB, Peters JW. 2010. Stepwise [FeFe]-hydrogenase H-cluster assembly revealed in the structure of HydA(DeltaEFG). Nature 465, 248–251. ( 10.1038/nature08993) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Slonczewski JL, Fujisawa M, Dopson M, Krulwich TA. 2009. Cytoplasmic pH measurement and homeostasis in Bacteria and Archaea. Adv. Microb. Physiol. 55, 1–79, 317. ( 10.1016/s0065-2911(09)05501-5) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kral TA, Birch W, Lavender LE, Virden BT. 2014. Potential use of highly insoluble carbonates as carbon sources by methanogens in the subsurface of Mars. Planet. Space Sci. 101, 181–185. ( 10.1016/j.pss.2014.07.008) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Miller HM, Chaudhry N, Conrad ME, Bill M, Kopf SH, Templeton AS. 2018. Large carbon isotope variability during methanogenesis under alkaline conditions. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 237, 18–31. ( 10.1016/j.gca.2018.06.007) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Crespo-Medina M, Twing KI, Sánchez-Murillo R, Brazelton WJ, McCollom TM, Schrenk MO. 2017. Methane dynamics in a tropical serpentinizing environment: the Santa Elena Ophiolite, Costa Rica. Front. Microbiol. 8, 916 ( 10.3389/fmicb.2017.00916) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rempfert KR, Miller HM, Bompard N, Nothaft D, Matter JM, Kelemen P, Fierer N, Templeton AS. 2017. Geological and geochemical controls on subsurface microbial life in the Samail Ophiolite, Oman. Front. Microbiol. 8, 56 ( 10.3389/fmicb.2017.00056) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fones EM, Colman DR, Kraus EA, Nothaft DB, Poudel S, Rempfert KR, Spear JR, Templeton AS, Boyd ES. 2019. Physiological adaptations to serpentinization in the Samail Ophiolite, Oman. ISME J. 13, 1750–1762. ( 10.1038/s41396-019-0391-2) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gibney BR, Mulholland SE, Rabanal F, Dutton PL. 1996. Ferredoxin and ferredoxin–heme maquettes. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 93, 15 041–15 046. ( 10.1073/pnas.93.26.15041) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mulholland SE, Gibney BR, Rabanal F, Dutton PL. 1999. Determination of nonligand amino acids critical to [4Fe-4S]2+/+ assembly in ferredoxin maquettes. Biochemistry 38, 10 442–10 448. ( 10.1021/bi9908742) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Melendez-Hevia E, Waddell TG, Cascante M. 1996. The puzzle of the Krebs citric acid cycle: assembling the pieces of chemically feasible reactions, and opportunism in the design of metabolic pathways during evolution. J. Mol. Evol. 43, 293–303. ( 10.1007/BF02338838) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.McCollom TM, Seewald JS. 2003. Experimental constraints on the hydrothermal reactivity of organic acids and acid anions: I. Formic acid and formate. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 67, 3625–3644. ( 10.1016/S0016-7037(03)00136-4) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lang SQ, Butterfield DA, Schulte M, Kelley DS, Lilley MD. 2010. Elevated concentrations of formate, acetate and dissolved organic carbon found at the Lost City hydrothermal field. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 74, 941–952. ( 10.1016/j.gca.2009.10.045) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data presented herein are available in electronic supplementary material or through communication with the authors.