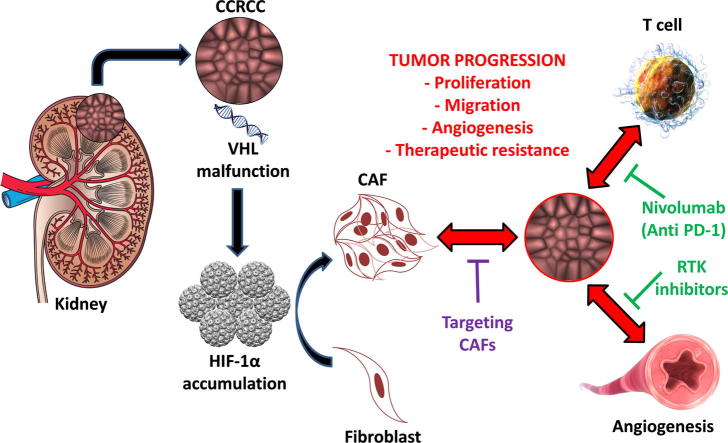

Graphical abstract

Therapeutic strategies targeting tumor cell/stroma interactions in Renal Cell Carcinoma. CAF could be activated due to the accumulation HIF-1α in tumor microenvironment, which is related with VHL gene malfunction in RCC cells. Activation of CAF is associated with RCC progression and therapeutic resistance.

Keywords: Renal cell carcinoma, Cancer associated fibroblast, Fibroblast activation protein, Prognosis, Targeted therapy

Abstract

Cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAF) are a cellular compartment of the tumor microenvironment (TME) with critical roles in tumor development. Fibroblast activation protein-α (FAP) is one of the proteins expressed by CAF and its immunohistochemical detection in routine practice is associated with tumor aggressiveness and shorter patient survival. For these reasons, FAP seems a good prognostic marker in many malignant neoplasms, including renal cell carcinoma (RCC). The start point of this Perspective paper is to review the role of CAF in the modulation of renal cell carcinoma evolution. In this sense, CAF have demonstrated to develop important protumor and/or antitumor activities. This apparent paradox suggests that some type of temporally or spatially-related specialization is present in this cellular compartment during tumor evolution. The end point is to remark that tumor/non-tumor cell interactions, in particular the symbiotic tumor/CAF connections, are permanent and ever-changing crucial phenomena along tumor lifetime. Interestingly, these interactions may be responsible of many therapeutic failures.

Introduction

RCC is an aggressive disease with high impact in Western societies. Standard radio- and chemotherapy regimens are not much effective strategies in improving survival of patients with metastatic disease. A significant advance in the treatment of metastatic RCC has been made in the last decade through the inhibition of the vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), and its receptor (VEGFR), and the mTOR pathway [1]. Likewise, new therapeutic approaches focusing on the tumor microenvironment are being implemented in the last years. In this sense, the blockade of programmed death-1 (PD-1) and its ligand (PD-L1) in intratumor inflammatory cells is showing promising results in clear cell renal cell carcinomas (CCRCC) [2]. Following the idea of targeting not only the neoplastic cells themselves but also the accompanying elements taking part of a tumor, the focus is being also directed against other non-neoplastic cellular compartment: the cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAF).

This paper reviews the role of CAF in renal cell carcinomas and analyzes the clinical relevance of FAP expression in these neoplasms.

Cancer-associated fibroblasts. An overview

Fibroblast activation is a common process in tissues under diverse conditions, for example, in response to injury. During their activation, fibroblasts undergo a phenotypic transformation migrating to the injured area. Once they complete their mission, the degradation of the extracellular matrix (ECM) triggers their apoptosis [3]. Tumors, presumably by epigenetic mechanisms, induce the chronic activation of local fibroblasts, a subgroup of cells collectively known as CAF [4]. These cells are characterized by the expression of a subset of proteins such as α smooth muscle actin (α-SMA), the classic marker of activated fibroblasts, fibroblast specific protein-1, also known as S100A4, desmin and FAP [5], among others. To note, the expression of these proteins is not limited to CAF and their distribution is not homogeneous [6]. This heterogeneity of CAF population can be attributed, at least in part, to their different origins. The main source of CAF is the activation of resident precursors within the tumor [7]. However, endothelial and epithelial cells can undergo endothelial/epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EndMT/EMT) process and become CAF [8], [9]. Bone marrow fibrocytes and mesenchymal stem cells are also a source of CAF [10], [11]. Even pericytes, adipocytes and vascular smooth muscle cells have been described to transform in CAF under appropriate conditions [12]. Thus, although the origin of CAF has been widely reviewed in bibliography, still remains as a controversial issue [13], [4], [14]. Together with the origin cell type, the activation is also a complex process in which different cytokines, growth factor, miRNAs and even exosomes are involved [15], [16].

Although CAF and tumor cells develop a local symbiotic relationship governed by the rules of Ecology [17], the specific functions of CAF in tumorigenesis are still not well understood. Both protumor and antitumor effects have been described in these cells supporting the idea that some type of cellular specialization must occur under pressures already unknown [18], [19], [20]. More specifically, main CAF actions have been related to hallmarks of cancer biology purposed by Hanahan and Weinberg in the beginning of the century and actualized a decade later [21], [22]. For example, they regulate tumor development stages secreting cytokines and growth factors such as VEGF, FGF-2 or SDF-1α and altering the extracellular matrix composition to regulate tumor growth promoting angiogenesis and invasive phenotypes [23]. CAF also have the capacity to reprogram tumor cell metabolism and immunosuppressive effects. For example, by CAF/tumor cell contact, CAF undergo Warburg metabolism and mitochondrial oxidative stress while tumor cells reprogram toward aerobic metabolism in a process strictly regulated by the Hypoxia Inducible Factor 1 (HIF-1). This way cancer cells lose glucose dependence and increase the lactate upload to drive anabolic pathways and in consequence, cell growth [24]. Regarding immunosuppression, Harper and Sainson reviewed direct (by the creation of an inflammatory signature with immunosuppressive function on both adaptive and innate white blood cells) and indirect effects (by the regulation of the stiffness, angiogenesis, hypoxia and metabolism) of CAF to regulate the antitumor immune response [25]. Drug resistance is another crucial factor during tumorigenesis. TME and primarily CAF have a determinant role in drug resistance by both cell adhesion mediated drug resistance and soluble factor mediated drug resistance [26].

Considering the comprehensive role of CAF in tumor development described above, several attempts have been developed to target this stromal population [5]. Inhibitors of CAF specific proteins, prodrugs activated only by CAF and even vaccines to target CAF have been designed, however, all of them have been unsuccessful to date. The identification of biomarkers that may allow distinguishing different CAF subgroups with specific actions would open up new possibilities in this research area.

Renal cell carcinoma. A model of tumor/non tumor cell interaction

RCC is a complex group of tumors originating from diverse epithelial cells of the kidney tubules. The World Health Organization describes more than 15 different histologic subtypes accounting for more than 95% of tumors in the adult kidney [27]. In 2018, kidney tumors represented 2.2% of all cancers, with more than 400,000 cases diagnosed worldwide [28]. These figures make RCC a health problem of major concern. These tumors are more frequent on male population with a 2:1 ratio, and the incidence is much higher in developed countries [29]. Although nomograms and models composed by the sum of different prognostic factors like UISS (UCLA Integrated Staging System) and SSIGN (Stage, Size, Grade and Necrosis) [30] have optimized patient prognosis, only surgery impacts significantly in patient survival. However, about a third of patients who have undergone curative surgery will relapse over time. Targeted therapies such as VEGF/VEGFR and mTOR inhibitors, and immunotherapy, have had promising results improving significantly the survival in selected patients with advanced disease [1] Indeed, sunitinib became first line therapy for metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC) since in 2007 was probed that it duplicates patient progression free survival from 5 to 11 months in comparison of previous treatments [31]. mTOR inhibitors extends this period allowing disease control [32]. Recently, the resurgence of immunotherapy based on immune checkpoint inhibitors such as nivolumab or ipilimumab have changed the standard of care of mRCC. Motzer et al. demonstrated in a study with more than 1000 patients that overall survival and response rate were significantly higher in patients with nivolumab/ipilimumab treatment than with sunitinib [33]. Actually the efforts are focused in the assessment of the combination and sequence of both therapies that will optimize patient benefit [34].

CAF have a protumor effect in RCC. In 2015, Xu et al. [35], showed in vitro that CAF are involved in tumor progression. These authors demonstrated in CAF/tumor cell co-cultures that CAF were implicated in tumor cell proliferation and migration, as well as in the development of mTOR inhibitors resistance [35]. Together with CAF, immune cells such as Tumor Associated Macrophages (TAM) have been suggested to mediate mTOR targeting resistance [36], although there is still no evidence in RCC. Also, CAF seem to have a role in early phases of CCRCC development through its relationship with hypoxia inducible factor 1 (HIF-1α) (see Graphical Abstract). The accumulation of this protein is the consequence of the Von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) gene malfunction, a driver event in CCRCC [37].

Accumulation of hypoxia inducible factors, induce the expression of a set of factors such as vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), stromal cell-derived factor-1 (SDF-1), platelet derived growth factor (PDGF), connective tissue growth factor (CTGF) and fibroblast growth factor 2 (FGF-2). Together, these factors induce the recruitment and activation of fibroblasts and other components of TME such as macrophages. Interactions between these different cell types generate the remodeling of the ECM, a key phenomenon for tumor development and metastasis [38]. Although all these specific mechanisms haven’t been described in RCC yet, expression of cited cytokines has been related to worse overall survival in RCC suggesting their protumor role [39], [40]. Primarily FGF-2, which’s expression in the invasion front correlated with RCC aggressiveness, where CAF develop key functions [40].

Zagzag et al. [41] demonstrated that the loss of function of VHL gene induced the signaling of stromal cell derived factor-1 (SDF-1) through its receptor CXCR4 and described it as a new angiogenic pathway. The expression of SDF-1/CXCR4 by different cellular components of CCRCCs, including CAF, suggests a paracrine signaling which would increase the expression of the receptor and its ligand under hypoxic conditions [41]. SDF-1/CXCR4 signaling has been proved to affect angiogenesis, tumor cell proliferation and chemoresistance by the communication of tumor cells with TME [42]. In RCC in particular, CXCR4 upregulation, a direct effect of HIF 1α accumulation, correlated with metastatic ability and was detected in RCC circulating cells of mRCC patients. These evidences suggest that the SDF-1/CXCR4 biological axis is a main regulator of organ-specific metastases in CCRCC and set out the potential of targeting this signaling pathway [43].

However, the influence of CAF in CCRCC goes further than VHL malfunction (Table 1). An in vivo RCC model showed that the chemokine CCL3 and its specific receptor CCR5 play a key role in the intratumor accumulation of CAF and other inflammatory cells such as granulocytes or macrophages [44]. Consequently, CAF increased the expression of the hepatocyte growth factor (HGF), a major angiogenic factor, and also the MMP-9 accumulation, this way contributing to the development of tumor metastasis [44].

Table 1.

Summary of interactive signaling pathways between CAF and tumor cells in RCC and their specific actions in tumor development.

| Authors | Interactive signaling pathway between CAF and tumor cells | Effect |

|---|---|---|

| Zagzag et al. 2005 [41] | VHL-HIF axis malfunction induces SDF-1/CXCR4 pathway overexpression which presumably increases angiogenesis by paracrine signaling | Protumor |

| Wu et al. 2008 [44] | CCL3/CCR5 axis paracrine signaling recruits fibroblasts to the tumor environment where they induce tumor progression by HGF and MMP-9 overexpression | Protumor |

| Bakhtyar et al. 2013 [45] | CCRCC cells induce periostin expression by CAF which induce tumor cell proliferation and attachment and CAF proliferation | Protumor |

| Xu et al. 2015 [35] | CAF/RCC in-vitro co-culture promotes tumor progression by MAPK/Erk and Akt pathway activation | Protumor |

| Chuanyu et al. 2017 [46] | Periostin promotes migration and invasion of renal cell carcinoma through the integrin/focal adhesion kinase/c-Jun N-terminal kinase pathway | Protumor |

The symbiotic relationship between tumor cells and CAF is illustrated by the upregulation of stromal periostin (PN) detected in CCRCC [45]. This adhesion protein secreted in the ECM has been detected in many cancers and has been related to cell motility, invasion and EMT processes. In vivo and in vitro experiments have demonstrated that tumor RCC cells induce the expression of PN by stromal cells [46]. Furthermore, the expression of PN is located in the boundary region between the xenograft tumor mass and the non-tumor tissue. Such expression is coincident with α-SMA expression, the classic marker of activated fibroblasts, both in primary and metastatic CCRCC. Functionally, PN enhances significantly CCRCC cell line attachment, NIH3T3 cell proliferation, and AKT activation [45].

All in all, the studies analyzed above demonstrate the implication of CAF in proliferation, angiogenesis, metastasis development and drug resistance during RCC tumorigenesis. This fact has postulated CAF as potential clinical tools for RCC diagnosis, prognosis and treatment. Several interstitial collagenases, which are mainly secreted by CAF [47], have demonstrated to have prognostic relevance in some neoplasms. The expression levels of MMP-2 and MMP-9, for example, have been correlated with tumor progression in a wide variety of neoplasms, included RCC [48], [49].

On the other hand, the expression of Fer, a non-receptor tyrosine kinase, in stromal cells, including fibroblasts and immune cells, correlated with a better prognosis in RCC [50]. This finding contrasts with Fer expression in tumor cells, where it has been linked with tumor aggressiveness and shorter survivals [51]. Fer expression in the stroma has been associated with a lower intra-tumor macrophage density (measured by CD68+ expressing cells) and correlated positively with CD57+ cell density, a common marker of NK cells in humans. Overall, these results suggest that stromal Fer may act as a suppressor of tumor progression in RCC although the clarification of the specific mechanisms involved in this process is unclear.

Gupta et al. [52] developed a fibroblast-derived ECM based on a 3D culture model to assess the clinical relevance of stromal markers in combination with their analysis in pathologic specimens. The authors concluded that palladin was a useful biomarker of poor prognosis in non-metastatic RCC [52]. In addition, they suggested that the assessment of stromal progression could be added to tumor stage as a useful clinical prognostic variable since stromal transformation not always correlates with tumor stage [52]. The authors remarked the usefulness of 3D culture models as surrogates of in vivo models, considering their capacity to mimic them by the increase of stromal markers as α-SMA, palladin and urokinase receptor associated protein [52].

The usefulness of FAP as a biomarker in CCRCC has been described recently [53], [54]. FAP is a transmembrane serine protease expressed by CAF in epithelial tumors originated in a wide variety of tissues [55]. Although the specific actions of this protease remain unclear, a relationship with the urokinase-mediated plasminogen activation system has been observed. Actually, FAP may form protein complexes with the urokinase plasminogen activator receptor (uPAR), its main substrate being α2-antiplasmin [56]. uPAR has been closely related to an aggressive behavior in cancer and has been proposed as a potential new therapeutic target [57].

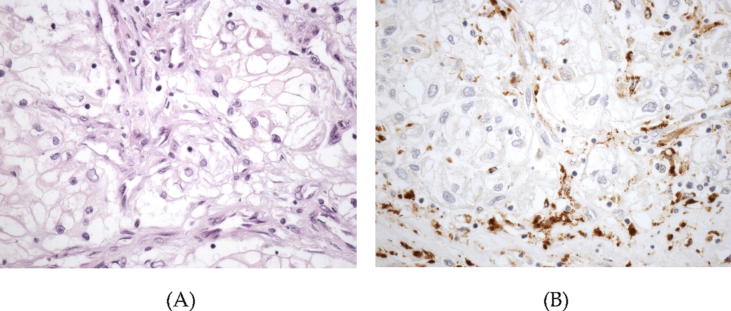

The immunohistochemical expression of FAP in formalin-fixed paraffin embedded tumor samples (see Fig. 1) correlated with high tumor diameter, high grade and high stage in a series of 208 CCRCC [53]. Furthermore, this protein was a strong predictor of aggressiveness, the survival rate of patients with FAP positive tumors being significantly lower [53]. Another study analyzing 59 CCRCC and their paired metastases showed a correlation between FAP expression in CAF and histological parameters of aggressive behavior like necrosis and sarcomatous phenotype [54]. Furthermore, FAP expression in primary CCRCC was associated with the development of synchronous lymph node metastases [54].

Fig. 1.

High power view of a high grade clear cell renal cell carcinoma (A) showing positive immunostaining with fibroblast activation protein restricted to the cancer-associated fibroblasts within the tumor (B) (original magnification, ×400).

FAP positive cells have been described as SDF-1 synthesizers. In fact, the induction of SDF-1 expression by FAP+ CAF has been described to promote tumorigenesis and the escape of immune surveillance in melanoma and pancreatic ductal carcinoma [58], [59]. Moreover, targeting this SDF-1 resulting from FAP+ CAF has been proved to synergize with immunotherapy [60]. Unravelling if this effect occurs in RCC would have a direct impact in the era of immunotherapy resurgence.

CAF are main responsible of ECM remodeling in TME by the production and secretion of proteases [61], [62] Fibroblast activation protein has a unique dual enzymatic activity (both collagenase and serine-peptidase), that enables the reorganization of collagen and fibronectin fibers to promote tumor cell invasion in pancreatic cells [63]. Strong relationship of FAP with RCC aggressiveness suggests a similar role for CAF and FAP in this tumor [54].

Conclusions and future perspectives. Targeting CAF, a new front against tumor microenvironment

In the era of personalized medicine and targeted therapies the comprehension of the tumor as a society composed by different elements extends the scope of action of anti-cancer drugs. This aspect acquires special relevance in RCC due to its radio- and chemo-resistant identity. In fact, tyrosine-kinase receptor inhibitors-based antiangiogenic treatment and PD-1/PD-L1 targeting immunotherapy are the main treatments that significantly improve patients’ survival. An effective targeting of CAF, one of the most important cell population in tumor microenvironment, seems the ideal complement considering their protumor role.

The fact that FAP is exclusively expressed in CAF, makes this protein an attractive target to develop CAF-mediated anti-tumor drugs. Different strategies have been designed such as inhibitors of its enzymatic activity [64], [65], prodrugs activated by its activity [66], FAP targeting antibodies [67], vaccines and even CAR-T cell technology [68]. Some of them are still being tested in clinical trials.

Although these strategies seem promising, targeting CAF in an effective manner appears much more complex than inhibiting the function of a specific protein. Unraveling if CAF conform subgroups specialized in different actions marks a milestone in the comprehension of the role of CAF in cancer in general and in RCC in particular. Similarly, understanding the impact of FAP expression by a subset of CAF will measure the usefulness of FAP targeting strategies. Removing the protumor cohort of CAF and potentiating the effect of those with antitumor activity is still utopic. However, reeducating those foes to friends as recently was proposed by Chen et al. would undoubtedly suppose a step forward in the war against cancer [69].

Grants

This work was partially funded by the ELKARTEK 18/10 grant from the Basque Government. PE was beneficiary of Dokberri grant for recent PhDs from the University of the Basque Country (UPV/EHU).

Compliance with ethics requirements

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors have declared no conflict of interest

Biographies

Peio Errarte, PhD. Postdoctoral Researcher at the University of Basque Country UPV/EHU, with 10 years experience in oncological translational research. I have developed my career between UPV/EHU and Oncology area of Biodonostia Health Research Insitute, including a short stay in the international institute CIBQA in Chile. Along this time, I have published 10 articles in internationally recognized peer-reviewed journals. Currently, I’m working in the assessment of the role of tumor microenvironment and the analysis of its different components as potential prognostic biomarkers and drug targets in urological tumors.

Gorka Larrinaga, MD, PhD, Professor of Physiology with 15 years’ experience in oncological translational research. I have participated in more than 25 research projects, published more than 40 publications in internationally recognized peer-reviewed journals and supervised 6 doctoral thesis. My research area is the study of different biomarkers in tumor microenvironment from solid tumors (mainly urological and colorectal).

Jose I. Lopez, MD, PhD Head and Professor of Pathology with 30 years of clinical activity interested in translational uro-oncology. More than 170 publications in internationally recognized peer-reviewed journals including Cell, Cancer Cell, NPJ Precis Oncol, Am J Surg Pathol, J Pathol J Mol Diagn, Histopathology, J Urol, etc. Consultant pathologist in the TRACERx Renal Consortium UK, H-index: 35, Total citations: 4341.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Cairo University.

Contributor Information

Peio Errarte, Email: peio.errarte@ehu.eus.

Gorka Larrinaga, Email: gorka.larrinaga@ehu.eus.

José I. López, Email: jilpath@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Hsieh J.J., Purdue M.P., Signoretti S., Swanton C., Albiges L., Schmidinger M. Renal cell carcinoma. Nat Rev Dis Prim. 2017;3:17009. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2017.9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nunes-Xavier C.E., Angulo J.C., Pulido R., López J.I. A critical insight into the clinical translation of PD-1/PD-L1 blockade therapy in clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Curr Urol Rep. 2019;20:1. doi: 10.1007/s11934-019-0866-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marsh T., Pietras K., McAllister S.S. Fibroblasts as architects of cancer pathogenesis. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1832:1070–1078. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2012.10.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kalluri R. The biology and function of fibroblasts in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2016;16:582–598. doi: 10.1038/nrc.2016.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tao L., Huang G., Song H., Chen Y., Chen L. Cancer associated fibroblasts: An essential role in the tumor microenvironment (Review) Oncol Lett. 2017 doi: 10.3892/ol.2017.6497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sugimoto H., Mundel T.M., Kieran M.W., Kalluri R. Identification of fibroblast heterogeneity in the tumor microenvironment. Cancer Biol Ther. 2006;5:1640–1646. doi: 10.4161/cbt.5.12.3354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arina A., Idel C., Hyjek E.M., Alegre M.-L., Wang Y., Bindokas V.P. Tumor-associated fibroblasts predominantly come from local and not circulating precursors. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2016;113:7551–7556. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1600363113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zeisberg E.M., Potenta S., Xie L., Zeisberg M., Kalluri R. Discovery of endothelial to mesenchymal transition as a source for carcinoma-associated fibroblasts. Cancer Res. 2007;67:10123–10128. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-3127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kalluri R., Weinberg R.A. The basics of epithelial-mesenchymal transition. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:1420–1428. doi: 10.1172/JCI39104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Quante M., Tu S.P., Tomita H., Gonda T., Wang S.S.W., Takashi S. Bone marrow-derived myofibroblasts contribute to the mesenchymal stem cell niche and promote tumor growth. Cancer Cell. 2011;19:257–272. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.01.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kurashige M., Kohara M., Ohshima K., Tahara S., Hori Y., Nojima S. Origin of cancer-associated fibroblasts and tumor-associated macrophages in humans after sex-mismatched bone marrow transplantation. Commun Biol. 2018;1:131. doi: 10.1038/s42003-018-0137-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hosaka K., Yang Y., Seki T., Fischer C., Dubey O., Fredlund E. Pericyte–fibroblast transition promotes tumor growth and metastasis. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2016;113:E5618–E5627. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1608384113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Anderberg C., Pietras K. On the origin of cancer-associated fibroblasts. Cell Cycle. 2009;8:1461–1462. doi: 10.4161/cc.8.10.8557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.LeBleu V.S., Kalluri R. A peek into cancer-associated fibroblasts: origins, functions and translational impact. Dis Model Mech. 2018;11:dmm029447. doi: 10.1242/dmm.029447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Räsänen K., Vaheri A. Activation of fibroblasts in cancer stroma. Exp Cell Res. 2010;316:2713–2722. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2010.04.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yang X., Li Y., Zou L., Zhu Z. Role of exosomes in crosstalk between cancer-associated fibroblasts and cancer cells. Front Oncol. 2019;6 doi: 10.3389/fonc.2019.00356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.López-Fernández E., López J.I. The impact of tumor eco-evolution in renal cell carcinoma sampling. Cancers (Basel) 2018;10. doi: 10.3390/cancers10120485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cirri P., Chiarugi P. Cancer-associated-fibroblasts and tumour cells: a diabolic liaison driving cancer progression. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2012;31:195–208. doi: 10.1007/s10555-011-9340-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Trimboli A.J., Cantemir-Stone C.Z., Li F., Wallace J.A., Merchant A., Creasap N. Pten in stromal fibroblasts suppresses mammary epithelial tumours. Nature. 2009;461:1084–1091. doi: 10.1038/nature08486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gieniec K.A., Butler L.M., Worthley D.L., Woods S.L. Cancer-associated fibroblasts—heroes or villains? Br J Cancer. 2019;121:293–302. doi: 10.1038/s41416-019-0509-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pietras K., Östman A. Hallmarks of cancer: Interactions with the tumor stroma. Exp Cell Res. 2010;316:1324–1331. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2010.02.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hanahan D., Weinberg R.A. Hallmarks of cancer: The next generation. Cell. 2011;144:646–674. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ferrara N. Pathways mediating VEGF-independent tumor angiogenesis. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2010;21:21–26. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2009.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fiaschi T., Marini A., Giannoni E., Taddei M.L., Gandellini P., De Donatis A. Reciprocal metabolic reprogramming through lactate shuttle coordinately influences tumor-stroma interplay. Cancer Res. 2012;72:5130–5140. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-1949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Harper J., Sainson R.C.A. Regulation of the anti-tumour immune response by cancer-associated fibroblasts. Semin Cancer Biol. 2014;25:69–77. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2013.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Meads M.B., Gatenby R.A., Dalton W.S. Environment-mediated drug resistance: a major contributor to minimal residual disease. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9:665–674. doi: 10.1038/nrc2714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Srigley J.R., Delahunt B., Eble J.N., Egevad L., Epstein J.I., Grignon D. The International Society of Urological Pathology (ISUP) vancouver classification of Renal Neoplasia. Am J Surg Pathol. 2013;37:1469–1489. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e318299f2d1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ferlay J., Colombet M., Soerjomataram I., Mathers C., Parkin D.M., Piñeros M. Estimating the global cancer incidence and mortality in 2018: GLOBOCAN sources and methods. Int J Cancer. 2019;144:1941–1953. doi: 10.1002/ijc.31937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Znaor A., Lortet-Tieulent J., Laversanne M., Jemal A., Bray F. International variations and trends in renal cell carcinoma incidence and mortality. Eur Urol. 2015;67:519–530. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2014.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Abel E.J., Masterson T.A., Karam J.A., Master V.A., Margulis V., Hutchinson R. Predictive nomogram for recurrence following surgery for nonmetastatic renal cell cancer with tumor thrombus. J Urol. 2017;198:810–816. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2017.04.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Motzer R.J., Hutson T.E., Tomczak P., Michaelson M.D., Bukowski R.M., Rixe O. Sunitinib versus interferon alfa in metastatic renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:115–124. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa065044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Motzer R.J., Escudier B., Oudard S., Hutson T.E., Porta C., Bracarda S. Efficacy of everolimus in advanced renal cell carcinoma: a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled phase III trial. Lancet. 2008;372:449–456. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61039-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Motzer R.J., Tannir N.M., McDermott D.F., Arén Frontera O., Melichar B., Choueiri T.K. Nivolumab plus ipilimumab versus sunitinib in advanced renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:1277–1290. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1712126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Considine B., Hurwitz M.E. Current status and future directions of immunotherapy in renal cell carcinoma. Curr Oncol Rep. 2019;21:34. doi: 10.1007/s11912-019-0779-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Xu Y., Lu Y., Song J., Dong B., Kong W., Xue W. Cancer-associated fibroblasts promote renal cell carcinoma progression. Tumour Biol. 2015;36:3483–3488. doi: 10.1007/s13277-014-2984-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Conciatori F., Bazzichetto C., Falcone I., Pilotto S., Bria E., Cognetti F. Role of mTOR signaling in tumor microenvironment: an overview. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19 doi: 10.3390/ijms19082453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.López J.I. Renal tumors with clear cells. A review. Pathol Res Pract. 2013;209:137–146. doi: 10.1016/j.prp.2013.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gilkes D.M., Semenza G.L., Wirtz D. Hypoxia and the extracellular matrix: drivers of tumour metastasis. Nat Rev Cancer. 2014;14:430–439. doi: 10.1038/nrc3726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shim M., Song C., Park S., Choi S.-K., Cho Y.M., Kim C.-S. Prognostic significance of platelet-derived growth factor receptor-β expression in localized clear cell renal cell carcinoma. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2015;141:2213–2220. doi: 10.1007/s00432-015-2019-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Horstmann M., Merseburger A.S., von der Heyde E., Serth J., Wegener G., Mengel M. Correlation of bFGF expression in renal cell cancer with clinical and histopathological features by tissue microarray analysis and measurement of serum levels. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2005;131:715–722. doi: 10.1007/s00432-005-0019-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zagzag D., Krishnamachary B., Yee H., Okuyama H., Chiriboga L., Ali M.A. Stromal cell-derived factor-1α and CXCR4 expression in hemangioblastoma and clear cell-renal cell carcinoma: von Hippel-Lindau loss-of-function induces expression of a ligand and its receptor. Cancer Res. 2005;65:6178–6188. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-4406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Meng W., Xue S., Chen Y. The role of CXCL12 in tumor microenvironment. Gene. 2018;641:105–110. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2017.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pan J., Mestas J., Burdick M.D., Phillips R.J., Thomas G.V., Reckamp K. Stromal derived factor-1 (SDF-1/CXCL12) and CXCR4 in renal cell carcinoma metastasis. Mol Cancer. 2006;5:56. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-5-56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang H., Wu Q., Liu Z., Luo X., Fan Y., Liu Y. Downregulation of FAP suppresses cell proliferation and metastasis through PTEN/PI3K/AKT and Ras-ERK signaling in oral squamous cell carcinoma. Cell Death Dis. 2014;5 doi: 10.1038/cddis.2014.122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bakhtyar N., Wong N., Kapoor A., Cutz J.-C., Hill B., Ghert M. Clear cell renal cell carcinoma induces fibroblast-mediated production of stromal periostin. Eur J Cancer. 2013;49:3537–3546. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2013.06.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chuanyu S., Yuqing Z., Chong X., Guowei X., Xiaojun Z. Periostin promotes migration and invasion of renal cell carcinoma through the integrin/focal adhesion kinase/c-Jun N-terminal kinase pathway. Tumour Biol. 2017;39 doi: 10.1177/1010428317694549. 1010428317694549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ala-aho R, Kähäri V-M. Collagenases in cancer. Biochimie n.d.;87:273–86. 10.1016/j.biochi.2004.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 48.Brinckerhoff C.E., Rutter J.L., Benbow U. Interstitial collagenases as markers of tumor progression. Clin Cancer Res. 2000;6:4823–4830. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kugler A., Hemmerlein B., Thelen P., Kallerhoff M., Radzun H.J., Ringert R.H. Expression of metalloproteinase 2 and 9 and their inhibitors in renal cell carcinoma. J Urol. 1998;160:1914–1918. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mitsunari K., Miyata Y., Watanabe S.-I., Asai A., Yasuda T., Kanda S. Stromal expression of Fer suppresses tumor progression in renal cell carcinoma and is a predictor of survival. Oncol Lett. 2017;13:834–840. doi: 10.3892/ol.2016.5481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Miyata Y., Kanda S., Sakai H., Greer P.A. Feline sarcoma-related protein expression correlates with malignant aggressiveness and poor prognosis in renal cell carcinoma. Cancer Sci. 2013;104:681–686. doi: 10.1111/cas.12140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gupta V., Bassi D.E., Simons J.D., Devarajan K., Al-Saleem T., Uzzo R.G. Elevated expression of stromal palladin predicts poor clinical outcome in renal cell carcinoma. PLoS ONE. 2011;6 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0021494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.López J.I., Errarte P., Erramuzpe A., Guarch R., Cortés J.M., Angulo J.C. Fibroblast activation protein predicts prognosis in clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Hum Pathol. 2016;54 doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2016.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Errarte P., Guarch R., Pulido R., Blanco L., Nunes-Xavier C.E., Beitia M. The expression of fibroblast activation protein in clear cell renal cell carcinomas is associated with synchronous lymph node metastases. PLoS ONE. 2016;11 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0169105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Garin-Chesa P., Old L.J., Rettig W.J. Cell surface glycoprotein of reactive stromal fibroblasts as a potential antibody target in human epithelial cancers. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:7235–7239. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.18.7235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Artym V.V., Kindzelskii A.L., Chen W.-T., Petty H.R. Molecular proximity of seprase and the urokinase-type plasminogen activator receptor on malignant melanoma cell membranes: dependence on beta1 integrins and the cytoskeleton. Carcinogenesis. 2002;23:1593–1601. doi: 10.1093/carcin/23.10.1593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Montuori N., Pesapane A., Rossi F.W., Giudice V., De Paulis A., Selleri C. Urokinase type plasminogen activator receptor (uPAR) as a new therapeutic target in cancer. Transl Med @ UniSa. 2016;15:15–21. 27896223. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sorrentino C., Miele L., Porta A., Pinto A., Morello S. Activation of the A2B adenosine receptor in B16 melanomas induces CXCL12 expression in FAP-positive tumor stromal cells, enhancing tumor progression. Oncotarget. 2016;7:64274–64288. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.11729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Fearon D.T. The Carcinoma-Associated Fibroblast Expressing Fibroblast Activation Protein and Escape from Immune Surveillance. Cancer Immunol Res. 2014;2:187–193. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-14-0002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Feig C., Jones J.O., Kraman M., Wells R.J.B., Deonarine A., Chan D.S. Targeting CXCL12 from FAP-expressing carcinoma-associated fibroblasts synergizes with anti-PD-L1 immunotherapy in pancreatic cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:20212–20217. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1320318110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Erdogan B., Webb D.J. Cancer-associated fibroblasts modulate growth factor signaling and extracellular matrix remodeling to regulate tumor metastasis. Biochem Soc Trans. 2017;45:229–236. doi: 10.1042/BST20160387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Liu T., Zhou L., Li D., Andl T., Zhang Y. Cancer-associated fibroblasts build and secure the tumor microenvironment. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2019;7 doi: 10.3389/fcell.2019.00060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lee H.-O., Mullins S.R., Franco-Barraza J., Valianou M., Cukierman E., Cheng J.D. FAP-overexpressing fibroblasts produce an extracellular matrix that enhances invasive velocity and directionality of pancreatic cancer cells. BMC Cancer. 2011;11:245. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-11-245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Poplawski S.E., Lai J.H., Li Y., Jin Z., Liu Y., Wu W. Identification of selective and potent inhibitors of fibroblast activation protein and prolyl oligopeptidase. J Med Chem. 2013;56:3467–3477. doi: 10.1021/jm400351a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Eager R.M., Cunningham C.C., Senzer N., Richards D.A., Raju R.N., Jones B. Phase II trial of talabostat and docetaxel in advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 2009;21:464–472. doi: 10.1016/j.clon.2009.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kim M.-G., Shon Y., Kim J., Oh Y.-K. Selective activation of anticancer chemotherapy by cancer-associated fibroblasts in the tumor microenvironment. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2017;109 doi: 10.1093/jnci/djw186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hofheinz R.-D., Al-Batran S.-E., Hartmann F., Hartung G., Jäger D., Renner C. Stromal antigen targeting by a humanised monoclonal antibody: an early phase II trial of sibrotuzumab in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. Onkologie. 2003;26:44–48. doi: 10.1159/000069863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wang L.-C.S., Lo A., Scholler J., Sun J., Majumdar R.S., Kapoor V. Targeting fibroblast activation protein in tumor stroma with chimeric antigen receptor T cells can inhibit tumor growth and augment host immunity without severe toxicity. Cancer. Immunol Res. 2014;2:154–166. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-13-0027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Chen X., Song E. Turning foes to friends: targeting cancer-associated fibroblasts. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2018 doi: 10.1038/s41573-018-0004-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]