Graphical abstract

Keywords: Vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, Treatment, Vancomycin, vanA cluster

Highlights

-

•

MRSA infection is a global threat to public health.

-

•

Vancomycin is one of the first-line drugs for the treatment of MRSA infections.

-

•

MRSA with complete resistance to vancomycin have emerged in recent years.

-

•

The total number of VRSA isolates is updated in this paper.

-

•

Resistance mechanisms, characteristics of VRSA infections, as well as clinical treatments are reviewed.

Abstract

The infection caused by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) is a global threat to public health. Vancomycin remains one of the first-line drugs for the treatment of MRSA infections. However, S. aureus isolates with complete resistance to vancomycin have emerged in recent years. Vancomycin-resistant S. aureus (VRSA) is mediated by a vanA gene cluster, which is transferred from vancomycin-resistant enterococcus. Since the first VRSA isolate was recovered from Michigan, USA in 2002, 52 VRSA strains have been isolated worldwide. In this paper, we review the latest progresses in VRSA, highlighting its resistance mechanism, characteristics of VRSA infections, as well as clinical treatments.

Introduction

Due to the metabolic versatility and pharmic resistance, Staphylococcus aureus is well adapted in varied environments. Approximately 25–30% of healthy individuals are colonized by S. aureus on their skins and nasopharyngeal membranes, where S. aureus exists as a member of normal microbiota and does not cause infections on normal immune status [1]. However, S. aureus can cause a variety of serious infections upon invading the bloodstream or internal tissues. S. aureus is a leading human pathogen that causes a variety of clinical manifestations ranging from relatively benign skin and soft tissue infections to severe and life-threatening systemic diseases [2], and remains a challenging public health issue due to the emergence and dissemination of multidrug resistant strains, for example, methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) [1], [3].

Methicillin resistance is conferred by mecA or mecC gene, which is located on the staphylococcal chromosomal cassette, and encodes penicillin-binding protein 2A (PBP2A) or PBP2ALGA, the enzymes that are responsible for crosslinking the peptidoglycans of bacterial cell wall [4]. Both enzymes show a low affinity for β-lactams, thereby leading to resistance to this category of antibiotics [5], [6]. Vancomycin has been one of the first line drugs to treat MRSA infections for decades [7], [8], [9]. However, the clinical isolates of S. aureus with intermediate and complete resistance to vancomycin have emerged within the past two decades [10], [11], and have become a serious public health concern [12]. In this paper, we review the latest advances in the studies of vancomycin-resistant S. aureus (VRSA), including resistance mechanism, infection characteristics, and clinical treatments of VRSA infections.

Vancomycin discovery and action mechanism

Vancomycin is one of the oldest antibiotics, and has been in clinical use for nearly 60 years. Dr. Kornield, an organic chemist of Eli Lilly, isolated vancomycin from Streptomyces orientalis in the deep jungles of Borneo in 1957 [13]. Vancomycin is active against Gram-positive bacteria, such as Staphylococci, Enterococci, Streptococci, Pneumococci, Listeria, Corynebacterium, and Clostridia. Currently, vancomycin is generally used for infections caused by MRSA and for the treatment of patients allergic to semisynthetic penicillin or cephalosporins [13].

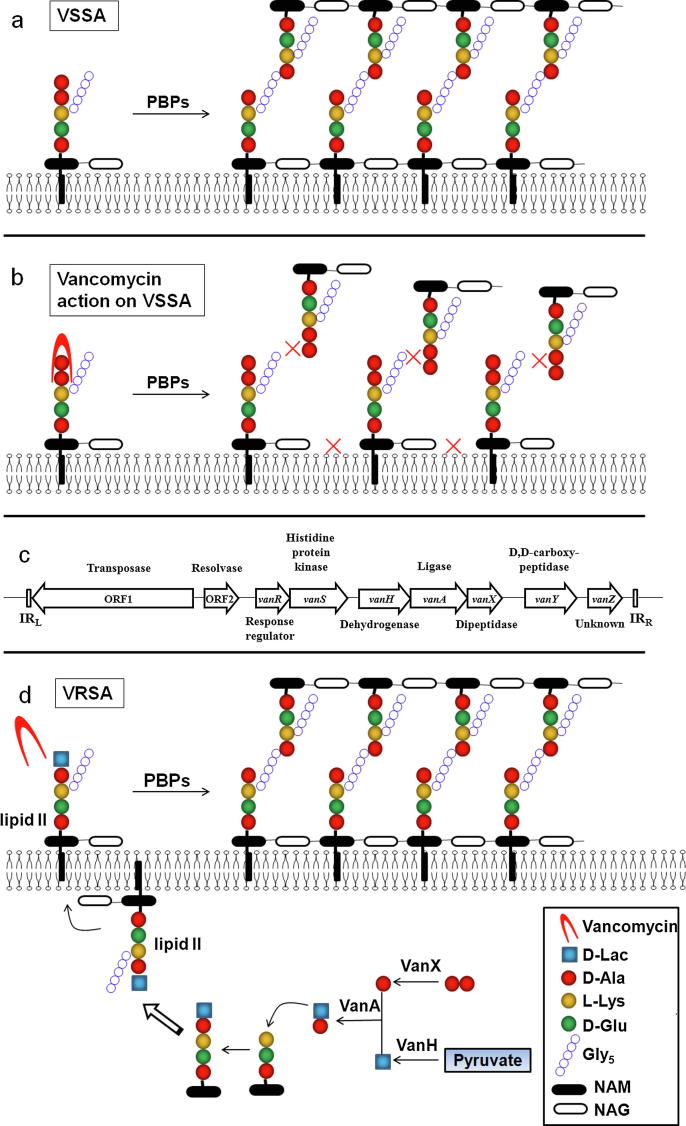

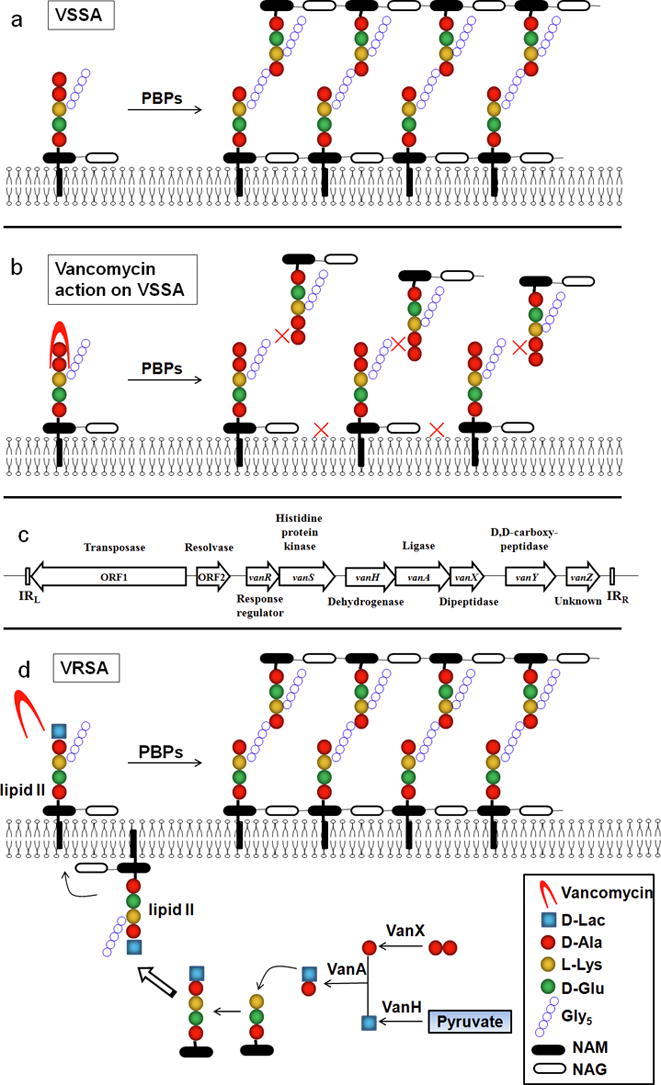

Vancomycin exerts its bactericidal action via interrupting proper cell wall synthesis in the susceptible bacteria. Most bacterial membranes are coated with a cell wall structure that protects cells from swelling and bursting due to intracellular high osmolarity. During propagation, the cell wall structure including peptidoglycan needs to be enlarged. To do that, the precursor lipid II is added to the nascent peptidoglycan via transglycosylation and transpeptidation by the penicillin-binding proteins (PBPs) (Fig. 1a). The hydrophilic molecule of vancomycin can form hydrogen bond interactions with the terminal D-alanyl-D-alanine (d-Ala–d-Ala) moieties of the precursor lipid II. The binding of vancomycin leads to conformational alteration that prevents the incorporation of the precursor to the growing peptidoglycan chain and the subsequent transpeptidation, thereby leading to cell wall decomposition and bacterial lysis (Fig. 1b) [14]. However, the complex structure of vancomycin blocks its penetration through the outer membrane of Gram-negative bacteria, and exerts limited bactericidal effect on Gram-negative bacteria.

Fig. 1.

Resistant mechanism of vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. (a) Schematic diagram of normal peptidoglycan synthesis. (b) Schematic diagram of vancomycin action. (c) Organization of the vanA cluster. (d) Resistant mechanism of vancomycin-resistant S. aureus. D-Ala: D-Alanine; D-lac: D-lactate; L-Lys: L-Lysine; D-Glu: D-glutamate; Gly5: Pentaglycine; NAM: N-acetylmuramic acid; NAG: N-acetylglucosamine.

Vancomycin resistance and mechanism in S. aureus

The isolates of S. aureus with reduced susceptibility to vancomycin are classified into three groups by the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. These are vancomycin-susceptible S. aureus (VSSA) with MIC ≤ 2 μg/ml, vancomycin-intermediate S. aureus (VISA) with MIC of 4–8 μg/ml, and VRSA with MIC ≥ 16 μg/ml. In confirming whether an isolate belongs to VRSA, the presence of vanA or other van resistance determinants should be demonstrated by molecular methods [15].

VISA

Isolates of VISA, which are associated with hospitalization, persistent infection, prolongation, and/or failure of vancomycin therapy, have been recovered worldwide [12]. VISA strains are generally believed to be initiated from heterogeneous vancomycin-intermediate S. aureus (hVISA), which is defined as an S. aureus strain with a vancomycin MIC within the susceptible range (≤2 μg/ml) determined by conventional methods, while a cell subpopulation is in the vancomycin-intermediate range (≥4 μg/ml) [16], [17].

The molecular mechanisms underlying VISA development are incompletely defined [14], [18], [19]. However, many efforts have been made to identify genetic determinants associated with vancomycin-intermediate resistance via comparative genomics, transcriptomics, and proteomics of VISA and its isogenic VSSA, and led to the identification of multiple mutations in genes responsible for VISA formation [14], [20], [21]. It is generally accepted that VISA is a result of the gradual mutation accumulation of the VISA-associated genes [22]. Of particular importance are the genes encoding two-component regulatory systems, such as WalKR [23], [24], [25], GraSR [26], and VraSR [14], [26], [27]. Although their genetic lineages varied, VISA strains generally display common phenotypes, including thickened cell wall, reduced autolytic activity, and decreased virulence [12]. The mechanism linking the diverse mutant genes to the VISA common phenotypes is unclear and should be investigated further.

VRSA

Vancomycin became a therapeutic agent for the treatment of serious infections caused by MRSA in the late 1980 s [28], [29]. Almost at the same time, vancomycin-resistant enterococci (VRE) were first identified in Europe [30], [31], [32], [33], and quickly became endemic in hospital intensive care units. Vancomycin resistance in VRE was mediated by transposons mainly found on plasmids, which raised considerable concern about the risk of dissemination of vancomycin-resistant determinants to universally susceptible microorganisms of medical importance, especially S. aureus [33], [34]. This concern was subsequently confirmed by the successful transfer of the van element from Enterococcus faecalis to a MRSA strain in mix-infected mice [35].

In 2002, the first VRSA strain was recovered in Michigan, USA [11], [36]. In the same year, the second VRSA strain was isolated in Pennsylvania, USA [37]. Since then, a total of 52 VRSA strains carrying van genes have been reported (Table 1), including 14 isolated in USA [37], [38], [39], [40], 16 in India [41], [42], [43], 11 in Iran [44], [45], [46], 9 in Pakistan [47], [48], 1 in Brazil [49], [50], and 1 in Portugal [51].

Table 1.

Characteristics of VRSA isolates.

| Country (No.) | City/State | Patient (Sex/age) |

Isolation time | Isolation site of VRSA | Typing and clonal complex | Vancomycin use in previous 3 months | Enterococci co-isolated | References* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| US (1) | Michigan | Female/40 | 2002.06 | Foot ulcer, catheter exit-site, catheter tip | USA100, t062, CC5 | Yes | VR E. faecalis | [29], [35] |

| US (2) | Pennsylvania | Male/70 | 2002.09 | Foot ulcer | USA100, t002, CC5 | No (exposure in 1997.09) | – | [29], [37], [75], [81] |

| US (3) | New York | Female/63 | 2004.03 | Urine | USA800, t002, CC5 | No (exposure in 2003.11) | VR E. faecium | [29], [39], [75] |

| US (4) | Michigan | Male/78 | 2005.02 | Toe wound | USA100, t002, CC5 | Yes | VR E. faecalis | [29], [75] |

| US (5) | Michigan | Female/58 | 2005.10 | Postpanniculectomy surgical infection | USA100, t002, CC5 | Yes | VR E. faecalis | [29], [75] |

| US (6) | Michigan | Male/48 | 2005.12 | Sole wound | T062, CC5 | Yes | VR E. faecalis VR E. avium | [29], [75] |

| US (7) | Michigan | Female/43 | 2006.10 | Triceps wound | USA100, t002, CC5 | Yes | – | [29], [75] |

| US (8) | Michigan | Female/48 | 2007.10 | Plantar foot wound | USA100, t002, CC5 | Yes | – | [75], [79], [89] |

| US (9) | Michigan | Female/54 | 2007.12 | Plantar foot wound | USA100, t002, CC5 | Yes | VR E. faecalis | [75], [79], [89] |

| US (10) | Michigan | Female/53 | 2009.12 | Sole wound | USA100, t002, CC5 | NA | VR E. faecalis VR E. galinarum VR E. raffinosus VR E. faecium | [75] |

| US (11) | Delaware | Female/64 | 2010.04 | Surgical wound drainage | USA100, t002, CC5 | NA | VR E. faecalis | [75] |

| US (12) | Delaware | Female/83 | 2010.08 | Vaginal swab | t045, CC5 | NA | VR E. galinarum | [75] |

| US (13) | Delaware | Male/70 | 2012.06 | Foot wound | USA1100, t019, CC30 | Yes | VR E. faecalis | [75] |

| US (14) | Delaware | NA | 2015.02 | Toe wound | USA100, t002, CC5 | No | VR E. faecalis | [76] |

| India (1) | Kolkata | NA | 2002.01–2005.12 | Outpatient pus sample | NA | NA | NA | [41] |

| India (2–6) | Uttar Pradesh | NA | NA | Postoperative wound | NA | NA | NA | [90] |

| India (7) | Andhra Pradesh | NA | 2008.03–2008.10 | Wound swab | NA | NA | NA | [42] |

| India (8) | Andhra Pradesh | NA | 2008.03–2008.10 | Wound swab | NA | NA | NA | [42] |

| India (9) | Andhra Pradesh | NA | 2008.03–2008.10 | Urine | NA | NA | NA | [42] |

| India (10) | Andhra Pradesh | NA | 2008.03–2008.10 | Ear swab | NA | NA | NA | [42] |

| India (11) | Andhra Pradesh | NA | 2008.03–2008.10 | Blood | NA | NA | NA | [42] |

| India (12) | Andhra Pradesh | NA | 2008.03–2008.10 | Throat swab | NA | NA | NA | [42] |

| India (13–16) | Bangalore | NA | 2003.04–2007.12 | Swabs from healthy individuals | NA | NA | NA | [91] |

| Iran (1) | Tehran | Male/67 | 2005 | Post-heart surgery wound | NA | NA | NA | [44] |

| Iran (2) | Tehran | Female/51 | 2008.01 | Foot ulcer | NA | NA | NA | [45] |

| Iran (3) | Mashhad | Male/26 | 2011.09–2011.12 | Bronchial aspirate | agr group I, ST1283, t037 | No | – | [46] |

| Iran (4) | Tehran | Male/>35 | 2014.12–2015.09 | Urine | NA | Yes | NA | [92] |

| Iran (5) | Tehran | Female/>35 | 2014.12–2015.09 | Urine | NA | Yes | NA | [92] |

| Iran (6) | Tehran | NA | 2014.03–2017.02 | Throat | ST5, t002, CC5 | Not sure (exposure within previous 11 months) | NA | [93] |

| Iran (7) | Tehran | NA | 2014.03–2017.02 | bronchial aspirate | ST239, t037, CC8 | Not sure (exposure within previous 11 months) | NA | [93] |

| Iran (8) | Tehran | NA | 2014.03–2017.02 | Wound | ST239, t037, CC8 | Not sure (exposure within previous 11 months) | NA | [93] |

| Iran (9) | Kerman | Female/76 | 2015.02 | Bronchial aspirate | t030 | NA | NA | [94] |

| Iran (10) | Kerman | Female/66 | 2015.04 | Bronchial aspirate | t030 | NA | NA | [94] |

| Iran(11) | Guilan | NA | 2017 | Blood | t030 | NA | NA | [95] |

| Pakistan (1) | Karachi | NA | NA | Blood | NA | NA | NA | [47] |

| Pakistan (2–9) | Faisalabad | NA | 2016.03–2016.07 | Pus from wounds, ear and skin | NA | NA | NA | [48] |

| Portugal (1) | Lisbon | Female/74 | 2013.05 | Toe amputation wound | ST105 | Yes | VR E. faecalis | [51] |

| Brazil (1) | São Paulo | Male/35 | 2012.08 | Blood, VR-MRSA;Blood, VR-MSSA | ST8, t292, CC8 | Yes | VR E. faecalis | [49], [50] |

NA: not available; -: Negative.

Mechanism underlying vancomycin resistance of VRSA

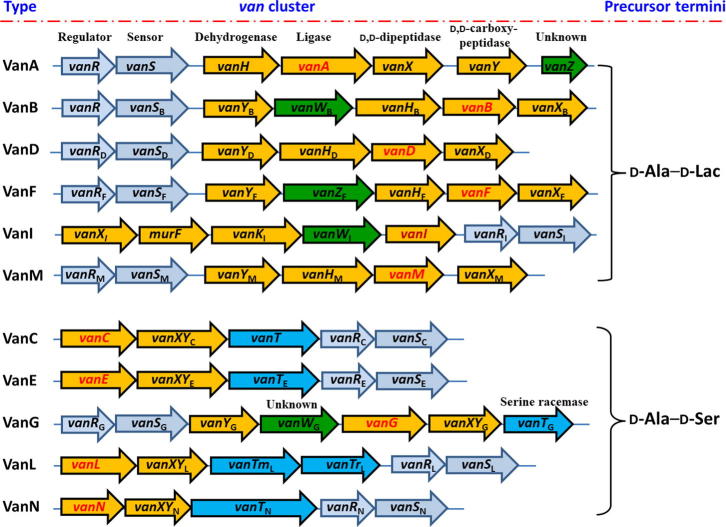

Vancomycin resistance in bacteria is mediated by van gene clusters that are found in pathogens (such as E. faecalis, E. faecium, S. aureus, and Clostridium difficile), glycopeptide-producing actinomycetes (such as Amycolotopsis orientalis, Actinoplanes teichomyceticus, and Streptomyces toyocaensis), anaerobic bacterium of the human bowel flora (such as Ruminococcus species), as well as a biopesticide Paenibacillus popilliae [52], [53], [54], [55], [56]. Vancomycin resistance is classified into several gene clusters based on the DNA sequence of the ligase van gene homologues that encode the key enzyme for the synthesis of d-alanyl–d-lactate (d-Ala–d-Lac) or d-alanyl–d-serine (d-Ala–d-Ser). At least 11 van gene clusters that confer vancomycin-resistance, responding for VanA, VanB, VanD, Van F, VanI, VanM, VanC, VanE, VanG, VanL, and VanN phenotypes, have been described to date [53], [57], [58], [59], [60]. The organization of these van clusters are shown in Supplementary Fig. 1. The genes that encode d-Ala:d-Lac ligases, such as vanA, vanB, vanD, van F, vanI, and vanM, often result in high-level vancomycin resistance with MICs > 256 mg/ml, while the genes that encode d-Ala:d-Ser ligases, including vanC, vanE, vanG, vanL, and vanN, generally result in low-level resistance with MICs of 8–16 mg/ml [61].

Acquired vancomycin resistance is most prevalent among Enterococcus and is still rare in other pathogenic bacteria [15]. The vancomycin-resistant mechanism has been elucidated in Enterococcus species, which are also the main reservoir of acquired vancomycin resistance [15]. Although 11 van gene clusters have been discovered to confer vancomycin resistance, only the vanA gene cluster is responsible for the isolated VRSA strains [15].

Five proteins encoded by the vanA gene cluster, VanS, VanR, VanH, VanA and VanX are essential for vancomycin resistance [62]. The original vanA gene cluster is carried in a transposon Tn1546 (Fig. 1c). VanS and VanR form a two-component system, and upregulate the expression of the cluster genes in the presence of vancomycin. VanH, VanA, and VanX modify the precursors from the native D-Ala-D-Ala to the resistant D-Ala-D-Lac. To do that, VanH serves as a dehydrogenase that reduces pyruvate to form d-Lac. VanX acts as a d,d-dipeptidase that hydrolyzes the native d-Ala–d-Ala to prevent it being used in the synthesis of peptidoglycan. VanA ligates D-Lac to D-Ala to produce the resistant D-Ala-D-Lac, which replaces d-Ala–d-Ala in the synthesis of peptidoglycan (Fig. 1d).

As above-mentioned, the action target of vancomycin is the terminal d-Ala–d-Ala moieties of the precursor lipid II, with which vancomycin forms hydrogen bond interactions and prevent subsequent transglycosylation and transpeptidation. However, the modified d-Ala–d-Lac leads to an almost 1000-fold decrease in affinity with vancomycin [63]. Therefore, vancomycin loses its bactericidal effect on strains with modified peptidoglycan precursor [15] (Fig. 1d).

Deletion of any one of these Van components leads to recovery of vancomycin activity, making them promising targets for new drug development [64]. For example, hydroxyethylamines, posphinate and phosphonate transition-state analogues have been demonstrated to be inhibitors of VanA [65], [66]. Phosphinate based, covalent inhibitors, and sulfur containing compounds have been explored to be inhibitors of VanX [67]. These inhibitors can be used in combination with vancomycin to prevent the decreased binding affinity of vancomycin with its target.

Characteristics of VRSA infections

Up to date, there have been reports of 52 VRSA isolates with definite determination of the vanA gene via PCR assay. Their main characteristics are listed in supplementary Table S1. The analysis of these cases yielded the following common characteristics.

Co-infection and co-colonization of VRE and MRSA Vancomycin resistance is achieved via the transfer of resistance determinants from a donor, usually VRE, to a recipient, usually MRSA. Therefore, co-infection and co-colonization of VRE with MRSA are common in clinical cases. In many cases, VRE strains were isolated along with VRSA (Table 1). VRE and MRSA co-infection and co-colonization are particularly common in the intensive care unit and long-term cared patients [68], [69], [70], [71]. Indwelling device use, recent antibiotic use, diabetes, and open wounds are believed to predict the co-colonization situation [72], [73], [74].

Prior use history of vancomycin In most cases, patients had a history of vancomycin use within three months prior to VRSA isolation. Vancomycin apparently serves as a selective pressure for drug resistance conferred by the vanA gene cluster.

Precursor diseases for VRSA infection Patients infected by VRSA generally suffered from several precursor diseases, including diabetes, end-stage renal failure, and gangrenous wound or surgical wound. Biofilms formed in wound or catheter facilitated the transfer of vancomycin-resistant plasmids from VRE to S. aureus [39].

Majority of VRSA isolates belongs to clonal complex 5 (CC5) lineage The molecular types of most VRSA isolates with typing data are categorized to CC5 phylogenetic lineage. Notably, in 14 characterized US VRSAs, 13 strains belong to the CC5 lineage [75], [76], which is the most prevalent clones causing hospital-associated infections in the Western Hemisphere [77]. The mechanisms underlying the predominant role of CC5 lineage in VRSA formation have not been determined to date.

Effective antibiotic for VRSA Fortunately, VRSA isolates are susceptible to multiple antibiotics [78] (Table S1), which made antibacterial therapy an effective option in the clinical treatment of VRSA infections. Datomycin and linezolid are two commonly selected antibiotics for VRSA infection treatment (Table S1).

Treatment of VRSA infections

Due to the scarcity of the VRSA infection cases, no treatment guideline is currently available. Out of all reported VRSA cases, only a few provided detailed clinical data. According to these treatment experiences and CDC recommendations, the treatment of VRSA infections in general should include, but not be limited to the following.

Systemic antimicrobial therapy

Except for vancomycin resistance, VRSA isolates commonly remain susceptible to multiple antimicrobial agents (Table S1). It was reported that >90% of 13 VRSA isolates were susceptible to ceftaroline, daptomycin, linezolid, minocyline, tigecycline, rifampin, and trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole [78]. Therefore, a systemic antimicrobial therapy with effective antibiotics is generally implemented upon VRSA isolation determination by a clinical laboratory [29], [36], [79], [80].

Wound care

Bacterial colonization is the first step in development of infections. As described in the previous section, co-infection and co-colonization of VRE and MRSA is favorable for the development of VRSA. Wound is the most common source of VRSA isolates and provides an environment for co-infection and co-colonization of MRSA and VRE. Therefore, aggressive wound care is generally implemented in the VRSA infection treatment (Table S1) [29], [36], [80]. Wound management not only contributes to the removal of VRSA but also blocks further possible plasmid delivery via eliminating the favorable environment for co-colonization.

Prevention of hospital transmission

Hospital-acquired infections are commonly associated with high morbidity and mortality. In order to prevent hospital transmission, infection control precautions, including patient isolation, contact investigation, decolonization (when necessary), and prompt notification to infection control and local health authorities, should be initiated promptly upon VRSA determination in a laboratory [29], [36], [37]. Fortunately, no in-hospital communication has been reported so far.

In cases with detailed clinical data, clinical treatments were effective in part [36], [79] but have failed in several cases due to the deterioration of the primary diseases [46], [49], [81]. Accumulation of more cases is necessary for recommendation of a treatment guideline for VRSA infections.

Will VRSA be widespread in future?

The emergence of vancomycin resistance has ended the dominant status of vancomycin in the therapy of Gram-positive bacterial infections. Fortunately, the occurrence of VRSA infection remains rare. This phenomenon is prominent, especially in comparison with the rapid emergence and spread of vancomycin resistance in Enterococci. This phenomenon may be explained by a few possible reasons listed as following.

Role of staphylococcal restrictive modification

In S. aureus cells, two restrictive modification systems, namely, SauI and type III-like restriction system, block horizontal gene transfer into S. aureus from other species and control the spread of resistant genes between the isolates of different S. aureus lineages [82], [83].

Restriction of vancomycin use

Prior vancomycin treatment was involved in most cases of VRSA infection. The use of vancomycin is a risk factor for infection and colonization with VRE [84], [85], and can increase the emergence of VRSA. Current controlled use of vancomycin (from the first line of antibiotics down to the final line of antibiotics against Gram-positive bacteria) reduces the selection pressure of vancomycin resistance.

Limitation of VRSA transmission in S. aureus

In most reported cases of VRSA infection, VRSA isolates arose from the independent transfer of the van gene cluster on a conjugative element from a VRE donor to a S. aureus recipient [75], [86], [87]. Epidemiologic and laboratory investigations have been used to assess the risk for transmission of VRSA to other patients, healthcare workers, and close family members. No VRSA transmission has been observed to date, and the mechanism underlying this limitation is of interesting for further investigation.

Instability of Tn1546 transposon carried plasmid in VRSA

The vancomycin-resistant phenotypes of several VRSA isolates are unstable. For example, an isolate designated as VRSA 595, which was recovered from a 63-year-old female patient at a long-term care facility in New York (US 3), reverted to a vancomycin-susceptible phenotype after two subcultures [39]. The VRSA isolate recovered in Pennsylvania (US 2) is genetically instable with a high rate of spontaneous loss of the vancomycin resistance determinant, thereby resulting in low-level vancomycin-resistant phenotype [88].

Conclusions

-

1.

Vancomycin has been an effective agent against the MRSA infections for decades. It is likely remains domination as long as resistance to vancomycin is under control, as well as new antibiotic with superior performance are not available.

-

2.

Although the case number of VRSA infection is limited, VRSA is still a potential threat to public health. Intensive surveillance of vancomycin-resistance, proper use of antibiotics, and adherence to infection control guidelines in health-care settings are essential for preventing emergence and dissemination of VRSA strains.

-

3.

The identification and study of new resistant determinants are important for surveillance of vancomycin-resistance.

-

4.

The modification of the terminal dipeptide moieties of the precursor lipid II is the main cause of failure of vancomycin action. Future research should focus on how to reverse the modification.

-

5.

Most patients with VRSA infection suffered from underlying diseases, vaccination for susceptible populations may be a feasible way to reduce the infections caused by S. aureus including VRSA.

Compliance with ethics requirements

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors have declared no conflict of interest

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Department of Science and Technology of Sichuan province under Grant [number 2019YJ0693 to YC], Southwest Medical University-Traditional Medicine Hospital Affiliated to Southwest Medical University under Grant [number 2018XYLH-017 to YC], the National Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant [numbers 81672071 and 81471993 to XR].

Biographies

Yanguang Cong undertook his graduate training at Third Military Medical University of China. His postdoctoral studies were continued at Louisiana State University Health Science Center (New Orleans) of United States. He is currently working as an Associated Professor and deputy director in Department of Clinical Laboratory, Traditional Medicine Hospital Affiliated to Southwest Medical University, China. His research is focused on bacterial pathogenicity and drug resistance. He has more than 70 peer reviewed research papers and two patents.

Sijin Yang is a professor and the president of Traditional Medicine Hospital Affiliated to Southwest Medical University, China. He is expert in treatment of cardiovascular diseases, cerebrovascular diseases, as well as clinical infections. He serves as a chief expert of Health Commission of Sichuan province. He has more than 200 peer reviewed research articles and 20 monographs.

Prof. Xiancai Rao obtained his PhD from Third Military Medical University of China in 2002, and then worked as a Postdoc at Boston University Medical Center and Louisiana State University of United States. He is currently a Professor and Head of Department of Microbiology, Third Military Medical University of China. His broad research interests concern drug resistance of Staphylococcus aureus, pathogenicity of Chlamydia trachomatis, and vaccine development of Dengue virus. He has more than 100 peer reviewed research articles and three patents.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Cairo University.

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jare.2019.10.005.

Contributor Information

Sijin Yang, Email: ysjimn@sina.com.

Xiancai Rao, Email: raoxiancai@126.com.

Appendix A. Supplementary material

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

Supplementary Fig. 1.

References

- 1.Rasigade J.P., Vandenesch F. Staphylococcus aureus: a pathogen with still unresolved issues. Infect Genet Evol. 2014;21:510–514. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2013.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chambers H.F., Deleo F.R. Waves of resistance: Staphylococcus aureus in the antibiotic era. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2009;7(9):629–641. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Taylor TA, Unakal CG. Staphylococcus aureus, in StatPearls. Treasure Island; FL: 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kim C., Milheirico C., Gardete S., Holmes M.A., Holden M.T., de Lencastre H. Properties of a novel PBP2A protein homolog from Staphylococcus aureus strain LGA251 and its contribution to the beta-lactam-resistant phenotype. J Biol Chem. 2012;287(44):36854–36863. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.395962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hartman B.J., Tomasz A. Low-affinity penicillin-binding protein associated with beta-lactam resistance in Staphylococcus aureus. J Bacteriol. 1984;158(2):513–516. doi: 10.1128/jb.158.2.513-516.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Turner N.A., Sharma-Kuinkel B.K., Maskarinec S.A., Eichenberger E.M., Shah P.P., Carugati M. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: an overview of basic and clinical research. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2019;17(4):203–218. doi: 10.1038/s41579-018-0147-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mermel L.A., Allon M., Bouza E., Craven D.E., Flynn P., O'Grady N.P. Clinical practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of intravascular catheter-related infection: 2009 Update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;49(1):1–45. doi: 10.1086/599376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sorrell T.C., Packham D.R., Shanker S., Foldes M., Munro R. Vancomycin therapy for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Ann Intern Med. 1982;97(3):344–350. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-97-3-344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pakyz A.L., MacDougall C., Oinonen M., Polk R.E. Trends in antibacterial use in US academic health centers: 2002 to 2006. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(20):2254–2260. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.20.2254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hiramatsu K., Aritaka N., Hanaki H., Kawasaki S., Hosoda Y., Hori S. Dissemination in Japanese hospitals of strains of Staphylococcus aureus heterogeneously resistant to vancomycin. Lancet. 1997;350(9092):1670–1673. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)07324-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chang S., Sievert D.M., Hageman J.C., Boulton M.L., Tenover F.C., Downes F.P. Infection with vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus containing the vanA resistance gene. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(14):1342–1347. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa025025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McGuinness W.A., Malachowa N., DeLeo F.R. Vancomycin Resistance in Staphylococcus aureus. Yale J Biol Med. 2017;90(2):269–281. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rubinstein E., Keynan Y. Vancomycin revisited - 60 years later. Front Public Health. 2014;2:217. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2014.00217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hu Q., Peng H., Rao X. Molecular events for promotion of vancomycin resistance in vancomycin intermediate Staphylococcus aureus. Front Microbiol. 2016;7:1601. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.01601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Werner G., Strommenger B., Witte W. Acquired vancomycin resistance in clinically relevant pathogens. Future Microbiol. 2008;3(5):547–562. doi: 10.2217/17460913.3.5.547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Howden B.P., Davies J.K., Johnson P.D., Stinear T.P., Grayson M.L. Reduced vancomycin susceptibility in Staphylococcus aureus, including vancomycin-intermediate and heterogeneous vancomycin-intermediate strains: resistance mechanisms, laboratory detection, and clinical implications. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2010;23(1):99–139. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00042-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hiramatsu K. Vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: a new model of antibiotic resistance. Lancet Infect Dis. 2001;1(3):147–155. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(01)00091-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sieradzki K., Tomasz A. Alterations of cell wall structure and metabolism accompany reduced susceptibility to vancomycin in an isogenic series of clinical isolates of Staphylococcus aureus. J Bacteriol. 2003;185(24):7103–7110. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.24.7103-7110.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cui L., Murakami H., Kuwahara-Arai K., Hanaki H., Hiramatsu K. Contribution of a thickened cell wall and its glutamine nonamidated component to the vancomycin resistance expressed by Staphylococcus aureus Mu50. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2000;44(9):2276–2285. doi: 10.1128/aac.44.9.2276-2285.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gardete S., Tomasz A. Mechanisms of vancomycin resistance in Staphylococcus aureus. J Clin Invest. 2014;124(7):2836–2840. doi: 10.1172/JCI68834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Howden B.P., McEvoy C.R., Allen D.L., Chua K., Gao W., Harrison P.F. Evolution of multidrug resistance during Staphylococcus aureus infection involves mutation of the essential two component regulator WalKR. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7(11):e1002359. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Katayama Y., Sekine M., Hishinuma T., Aiba Y., Hiramatsu K. Complete Reconstitution of the Vancomycin-Intermediate Staphylococcus aureus Phenotype of Strain Mu50 in Vancomycin-Susceptible S. aureus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2016;60(6):3730–3742. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00420-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Peng H., Hu Q., Shang W., Yuan J., Zhang X., Liu H. WalK(S221P), a naturally occurring mutation, confers vancomycin resistance in VISA strain XN108. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2017;72(4):1006–1013. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkw518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hu J., Zhang X., Liu X., Chen C., Sun B. Mechanism of reduced vancomycin susceptibility conferred by walK mutation in community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strain MW2. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2015;59(2):1352–1355. doi: 10.1128/AAC.04290-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McEvoy C.R., Tsuji B., Gao W., Seemann T., Porter J.L., Doig K. Decreased vancomycin susceptibility in Staphylococcus aureus caused by IS256 tempering of WalKR expression. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2013;57(7):3240–3249. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00279-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yoo J.I., Kim J.W., Kang G.S., Kim H.S., Yoo J.S., Lee Y.S. Prevalence of amino acid changes in the yvqF, vraSR, graSR, and tcaRAB genes from vancomycin intermediate resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J Microbiol. 2013;51(2):160–165. doi: 10.1007/s12275-013-3088-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gardete S., Kim C., Hartmann B.M., Mwangi M., Roux C.M., Dunman P.M. Genetic pathway in acquisition and loss of vancomycin resistance in a methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) strain of clonal type USA300. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8(2):e1002505. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rehm S.J., Tice A. Staphylococcus aureus: methicillin-susceptible S. aureus to methicillin-resistant S. aureus and vancomycin-resistant S. aureus. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;51(Suppl 2):S176–S182. doi: 10.1086/653518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sievert D.M., Rudrik J.T., Patel J.B., McDonald L.C., Wilkins M.J., Hageman J.C. Vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in the United States, 2002–2006. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46(5):668–674. doi: 10.1086/527392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Uttley A.H., George R.C., Naidoo J., Woodford N., Johnson A.P., Collins C.H. High-level vancomycin-resistant enterococci causing hospital infections. Epidemiol Infect. 1989;103(1):173–181. doi: 10.1017/s0950268800030478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Leclercq R., Derlot E., Weber M., Duval J., Courvalin P. Transferable vancomycin and teicoplanin resistance in Enterococcus faecium. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1989;33(1):10–15. doi: 10.1128/aac.33.1.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Uttley A.H., Collins C.H., Naidoo J., George R.C. Vancomycin-resistant enterococci. Lancet. 1988;1(8575–6):57–58. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(88)91037-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Leclercq R., Derlot E., Duval J., Courvalin P. Plasmid-mediated resistance to vancomycin and teicoplanin in Enterococcus faecium. N Engl J Med. 1988;319(3):157–161. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198807213190307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shlaes D.M., Bouvet A., Devine C., Shlaes J.H., Al-Obeid S., Williamson R. Inducible, transferable resistance to vancomycin in Enterococcus faecalis A256. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1989;33(2):198–203. doi: 10.1128/aac.33.2.198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Noble W.C., Virani Z., Cree R.G. Co-transfer of vancomycin and other resistance genes from Enterococcus faecalis NCTC 12201 to Staphylococcus aureus. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1992;72(2):195–198. doi: 10.1016/0378-1097(92)90528-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Centers for Disease C, Prevention Staphylococcus aureus resistant to vancomycin--United States, 2002. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2002;51(26):565–567. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Centers for Disease, C. and Prevention, Vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus--Pennsylvania, 2002. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep, 2002; 51(40): p. 902. [PubMed]

- 38.Centers for Disease, C. and Prevention, Vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus--New York, 2004. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep, 2004; 53(15): p. 322-3. [PubMed]

- 39.Weigel L.M., Donlan R.M., Shin D.H., Jensen B., Clark N.C., McDougal L.K. High-level vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolates associated with a polymicrobial biofilm. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2007;51(1):231–238. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00576-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Askari E., Tabatabai S., Arianpoor A., Nasab M. VanA-positive vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: systematic search and review of reported cases. Infect Diseases Clin Practice. 2013;21(2):91–93. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Saha B., Singh A.K., Ghosh A., Bal M. Identification and characterization of a vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolated from Kolkata (South Asia) J Med Microbiol. 2008;57(Pt 1):72–79. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.47144-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Thati V., Shivannavar C.T., Gaddad S.M. Vancomycin resistance among methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolates from intensive care units of tertiary care hospitals in Hyderabad. Indian J Med Res. 2011;134(5):704–708. doi: 10.4103/0971-5916.91001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tiwari H.K., Sen M.R. Emergence of vancomycin resistant Staphylococcus aureus (VRSA) from a tertiary care hospital from northern part of India. BMC Infect Dis. 2006;6:156. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-6-156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Aligholi M., Emaneini M., Jabalameli F., Shahsavan S., Dabiri H., Sedaght H. Emergence of high-level vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in the Imam Khomeini Hospital in Tehran. Med Princ Pract. 2008;17(5):432–434. doi: 10.1159/000141513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dezfulian A., Aslani M.M., Oskoui M., Farrokh P., Azimirad M., Dabiri H. Identification and characterization of a high vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus harboring VanA gene cluster isolated from diabetic foot ulcer. Iran J Basic Med Sci. 2012;15(2):803–806. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Azimian A., Havaei S.A., Fazeli H., Naderi M., Ghazvini K., Samiee S.M. Genetic characterization of a vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolate from the respiratory tract of a patient in a university hospital in northeastern Iran. J Clin Microbiol. 2012;50(11):3581–3585. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01727-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mirani Z.A., Jamil N. Effect of sub-lethal doses of vancomycin and oxacillin on biofilm formation by vancomycin intermediate resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J Basic Microbiol. 2011;51(2):191–195. doi: 10.1002/jobm.201000221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Azhar A., Rasool S., Haque A., Shan S., Saeed M., Ehsan B. Detection of high levels of resistance to linezolid and vancomycin in Staphylococcus aureus. J Med Microbiol. 2017;66(9):1328–1331. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.000566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rossi F., Diaz L., Wollam A., Panesso D., Zhou Y., Rincon S. Transferable vancomycin resistance in a community-associated MRSA lineage. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(16):1524–1531. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1303359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Panesso D., Planet P.J., Diaz L., Hugonnet J.E., Tran T.T., Narechania A. Methicillin-susceptible, vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Brazil. Emerg Infect Dis. 2015;21(10):1844–1848. doi: 10.3201/eid2110.141914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Melo-Cristino J., Resina C., Manuel V., Lito L., Ramirez M. First case of infection with vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in Europe. Lancet. 2013;382(9888):205. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61219-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hong H.J., Hutchings M.I., Buttner M.J. Biotechnology, and U.K. biological sciences research council, vancomycin resistance VanS/VanR two-component systems. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2008;631:200–213. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-78885-2_14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Xu X., Lin D., Yan G., Ye X., Wu S., Guo Y. vanM, a new glycopeptide resistance gene cluster found in Enterococcus faecium. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2010;54(11):4643–4647. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01710-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Patel R., Piper K., Cockerill F.R., 3rd, Steckelberg J.M., Yousten A.A. The biopesticide Paenibacillus popilliae has a vancomycin resistance gene cluster homologous to the enterococcal VanA vancomycin resistance gene cluster. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2000;44(3):705–709. doi: 10.1128/aac.44.3.705-709.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ammam F., Marvaud J.C., Lambert T. Distribution of the vanG-like gene cluster in Clostridium difficile clinical isolates. Can J Microbiol. 2012;58(4):547–551. doi: 10.1139/w2012-002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Domingo M.C., Huletsky A., Giroux R., Picard F.J., Bergeron M.G. vanD and vanG-like gene clusters in a Ruminococcus species isolated from human bowel flora. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2007;51(11):4111–4117. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00584-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Courvalin P. Vancomycin resistance in Gram-positive cocci. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;42(Suppl 1):S25–S34. doi: 10.1086/491711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Boyd D.A., Willey B.M., Fawcett D., Gillani N., Mulvey M.R. Molecular characterization of Enterococcus faecalis N06–0364 with low-level vancomycin resistance harboring a novel D-Ala-D-Ser gene cluster, vanL. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2008;52(7):2667–2672. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01516-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lebreton F., Depardieu F., Bourdon N., Fines-Guyon M., Berger P., Camiade S. D-Ala-d-Ser VanN-type transferable vancomycin resistance in Enterococcus faecium. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2011;55(10):4606–4612. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00714-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kruse T., Levisson M., de Vos W.M., Smidt H. vanI: a novel D-Ala-D-Lac vancomycin resistance gene cluster found in Desulfitobacterium hafniense. Microb Biotechnol. 2014;7(5):456–466. doi: 10.1111/1751-7915.12139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hollenbeck B.L., Rice L.B. Intrinsic and acquired resistance mechanisms in enterococcus. Virulence. 2012;3(5):421–433. doi: 10.4161/viru.21282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Arthur M., Courvalin P. Genetics and mechanisms of glycopeptide resistance in enterococci. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1993;37(8):1563–1571. doi: 10.1128/aac.37.8.1563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Arias C.A., Murray B.E. The rise of the Enterococcus: beyond vancomycin resistance. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2012;10(4):266–278. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Walsh C.T., Fisher S.L., Park I.S., Prahalad M., Wu Z. Bacterial resistance to vancomycin: five genes and one missing hydrogen bond tell the story. Chem Biol. 1996;3(1):21–28. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(96)90079-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sova M., Cadez G., Turk S., Majce V., Polanc S., Batson S. Design and synthesis of new hydroxyethylamines as inhibitors of D-alanyl-D-lactate ligase (VanA) and D-alanyl-D-alanine ligase (DdlB) Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2009;19(5):1376–1379. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2009.01.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ellsworth B.A., Tom N.J., Bartlett P.A. Synthesis and evaluation of inhibitors of bacterial D-alanine:D-alanine ligases. Chem Biol. 1996;3(1):37–44. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(96)90082-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Chen A.Y., Adamek R.N., Dick B.L., Credille C.V., Morrison C.N., Cohen S.M. Targeting metalloenzymes for therapeutic intervention. Chem Rev. 2019;119(2):1323–1455. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.8b00201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Franchi D., Climo M.W., Wong A.H., Edmond M.B., Wenzel R.P. Seeking vancomycin resistant Staphylococcus aureus among patients with vancomycin-resistant enterococci. Clin Infect Dis. 1999;29(6):1566–1568. doi: 10.1086/313530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Warren D.K., Nitin A., Hill C., Fraser V.J., Kollef M.H. Occurrence of co-colonization or co-infection with vancomycin-resistant enterococci and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in a medical intensive care unit. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2004;25(2):99–104. doi: 10.1086/502357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Furuno J.P., Perencevich E.N., Johnson J.A., Wright M.O., McGregor J.C., Morris J.G., Jr Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and vancomycin-resistant Enterococci co-colonization. Emerg Infect Dis. 2005;11(10):1539–1544. doi: 10.3201/eid1110.050508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Reyes K., Malik R., Moore C., Donabedian S., Perri M., Johnson L. Evaluation of risk factors for coinfection or cocolonization with vancomycin-resistant enterococcus and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J Clin Microbiol. 2010;48(2):628–630. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02381-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Heinze K., Kabeto M., Martin E.T., Cassone M., Hicks L., Mody L. Predictors of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and vancomycin-resistant enterococci co-colonization among nursing facility patients. Am J Infect Control. 2019;47(4):415–420. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2018.09.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Flannery E.L., Wang L., Zollner S., Foxman B., Mobley H.L., Mody L. Wounds, functional disability, and indwelling devices are associated with cocolonization by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and vancomycin-resistant enterococci in southeast Michigan. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;53(12):1215–1222. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Hayakawa K., Marchaim D., Bathina P., Martin E.T., Pogue J.M., Sunkara B. Independent risk factors for the co-colonization of vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecalis and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in the region most endemic for vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolation. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2013;32(6):815–820. doi: 10.1007/s10096-013-1814-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Limbago B.M., Kallen A.J., Zhu W., Eggers P., McDougal L.K., Albrecht V.S. Report of the 13th vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolate from the United States. J Clin Microbiol. 2014;52(3):998–1002. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02187-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Walters M.S., Eggers P., Albrecht V., Travis T., Lonsway D., Hovan G. Vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus - Delaware. 2015 MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64(37):1056. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6437a6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Challagundla L., Reyes J., Rafiqullah I., Sordelli D.O., Echaniz-Aviles G., Velazquez-Meza M.E. Phylogenomic classification and the evolution of clonal complex 5 methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in the Western Hemisphere. Front Microbiol. 2018;9:1901. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.01901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Saravolatz L.D., Pawlak J., Johnson L.B. In vitro susceptibilities and molecular analysis of vancomycin-intermediate and vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolates. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;55(4):582–586. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Finks J., Wells E., Dyke T.L., Husain N., Plizga L., Heddurshetti R. Vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, Michigan, USA, 2007. Emerg Infect Dis. 2009;15(6):943–945. doi: 10.3201/eid1506.081312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Friaes A., Resina C., Manuel V., Lito L., Ramirez M., Melo-Cristino J. Epidemiological survey of the first case of vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infection in Europe. Epidemiol Infect. 2015;143(4):745–748. doi: 10.1017/S0950268814001423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Whitener C.J., Park S.Y., Browne F.A., Parent L.J., Julian K., Bozdogan B. Vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in the absence of vancomycin exposure. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;38(8):1049–1055. doi: 10.1086/382357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Waldron D.E., Lindsay J.A. Sau1: a novel lineage-specific type I restriction-modification system that blocks horizontal gene transfer into Staphylococcus aureus and between S. aureus isolates of different lineages. J Bacteriol. 2006;188(15):5578–5585. doi: 10.1128/JB.00418-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Corvaglia A.R., Francois P., Hernandez D., Perron K., Linder P., Schrenzel J. A type III-like restriction endonuclease functions as a major barrier to horizontal gene transfer in clinical Staphylococcus aureus strains. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107(26):11954–11958. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1000489107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Montecalvo M.A., Horowitz H., Gedris C., Carbonaro C., Tenover F.C., Issah A. Outbreak of vancomycin-, ampicillin-, and aminoglycoside-resistant Enterococcus faecium bacteremia in an adult oncology unit. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1994;38(6):1363–1367. doi: 10.1128/aac.38.6.1363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Rubin L.G., Tucci V., Cercenado E., Eliopoulos G., Isenberg H.D. Vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecium in hospitalized children. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 1992;13(12):700–705. doi: 10.1086/648342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Kos V.N., Desjardins C.A., Griggs A., Cerqueira G., Van Tonder A., Holden M.T. Comparative genomics of vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strains and their positions within the clade most commonly associated with Methicillin-resistant S. aureus hospital-acquired infection in the United States. MBio. 2012;(3):3. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00112-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Weigel L.M., Clewell D.B., Gill S.R., Clark N.C., McDougal L.K., Flannagan S.E. Genetic analysis of a high-level vancomycin-resistant isolate of Staphylococcus aureus. Science. 2003;302(5650):1569–1571. doi: 10.1126/science.1090956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Perichon B., Courvalin P. Heterologous expression of the enterococcal vanA operon in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2004;48(11):4281–4285. doi: 10.1128/AAC.48.11.4281-4285.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Perichon B., Courvalin P. VanA-type vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2009;53(11):4580–4587. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00346-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Anjilika D., Chauhan S., Singh S. Detection of emerging VRSA/VISA strains carrying vanA resistance gene through PCR in Agra region. J Ecophysiol Occup Health. 2008;8(3):143–146. [Google Scholar]

- 91.Goud R., Gupta S., Neogi U., Agarwal D., Naidu K., Chalannavar R. Community prevalence of methicillin and vancomycin resistant Staphylococcus aureus in and around Bangalore, southern India. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2011;44(3):309–312. doi: 10.1590/s0037-86822011005000035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Yousefi M., Fallah F., Arshadi M., Pourmand M.R., Hashemi A., Pourmand G. Identification of tigecycline- and vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strains among patients with urinary tract infection in Iran. New Microbes New Infect. 2017;19:8–12. doi: 10.1016/j.nmni.2017.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Shekarabi M., Hajikhani B., Salimi Chirani A., Fazeli M., Goudarzi M. Molecular characterization of vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strains isolated from clinical samples: A three year study in Tehran. Iran. PLoS One. 2017;12(8):e0183607. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0183607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Fasihi Y., Saffari F., Mansouri S., Kalantar-Neyestanaki D. The emergence of vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in an intensive care unit in Kerman Iran. Wien Med Wochenschr. 2018;168(3–4):85–88. doi: 10.1007/s10354-017-0562-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Asadpour L., Ghazanfari N. Detection of vancomycin nonsusceptible strains in clinical isolates of Staphylococcus aureus in northern Iran. Int Microbiol. 2019 doi: 10.1007/s10123-019-00063-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.