Abstract

Aims

To evaluate the effectiveness and safety of topical β‐receptor blocker in treating superficial infantile haemangiomas (SIH) and compare the effectiveness and safety of topical β‐receptor blocker against other therapies.

Methods

A search of the literature using PubMed, Embase, Cochrane Review database, China National Knowledge Infrastructure and Wanfang were performed to identify the studies that estimated the effectiveness and safety of topical β‐receptor blocker in treating SIH, the fixed‐effect or random‐effects meta‐analytical techniques were applied to assess the outcomes.

Results

Twenty studies, involving 2098 patients, were included to conduct this analysis. Topical propranolol and topical timolol were discovered to be as effective as oral propranolol in treating SIH (propranolol, odds ratio [OR] = 0.486, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.165, 1.426, P = .189; timolol, OR = 0.955; 95%CI 0.700, 1.302; P = .769), and topical timolol was more effective than topical imiquimod (OR = 2.561; 95%CI 1.182, 5.550; P = .017), observation (OR = 18.458; 95%CI 5.660, 60.191; P < .001) and topical saline solutions (OR = 19.193; 95%CI 8.837, 41.683; P < .001) in treating SIH. The comparison between topical propranolol and oral propranolol led to no discovery of significant difference in the incidence of adverse effects (OR = 1.258; 95%CI 0.471, 3.358; P = .647). Compared with oral propranolol, topical timolol was associated with fewer incidences of adverse effects (OR = 0.191; 95%CI 0.043, 0.858; P = .031). No significant difference in the incidence of adverse effects was found when topical timolol and topical imiquimod were compared (OR = 0.077; 95%CI 0.005, 1.206; P = .068).

Conclusion

This meta‐analysis provided evidence that topical β‐receptor blockers (propranolol and timolol), especially timolol, may replace oral propranolol as a first‐line treatment for SIH.

Keywords: haemangioma, imiquimod, Meta‐analysis, propranolol, timolol

What is already known about this subject

It has been suggested in some reports that topical β‐receptor blocker provides an effective and safe alternative to oral propranolol for the treatment of superficial infantile haemangiomas (SIH). However, due to the lack of adequate evidence on the effectiveness and safety of topical β‐blockers, they cannot be recommended as a standard therapy to treat SIH.

What this study adds

This meta‐analysis provided evidence to demonstrate that topical β‐receptor blockers (propranolol and timolol), especially timolol, have a potential to replace oral propranolol as a first‐line treatment for SIH.

1. INTRODUCTION

Infant haemangioma is known as the most commonly seen true benign vascular neoplasm in infancy, with an incidence of 5–10% in infants. Infants with premature, low birth weight infants, Caucasian race and females have demonstrated a higher rate of morbidity.1, 2 Although a majority of superficial infantile haemangiomas (SIH) are self‐limited, some SIH have a potential to cause ulcers, bleeding or cosmetic disfigurement. Therefore, medication treatments are sometimes recommended to prevent the formation of potential scar and unpredictable permanent disfigurement.

Medication treatments for SIH include propranolol, timolol, glucocorticoid and imiquimod. In 2008, Léauté‐Labrèze et al.3 made a discovery, when performing propranolol treatment for an infant haemangioma patient with hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy and another underage haemangioma patient with increased cardiac output, that haemangiomas showed a shrinking size, reduced surface tension, softened texture and lightened colour. Subsequently, they performed oral propranolol treatment for 9 infants with haemangioma in the maxillofacial region. The effectiveness was found to be satisfactory in all 9 patients 24 h after the treatment. The report on this research attracted a great deal of attention from scholars worldwide.3 There has been increasing research supporting oral propranolol as a first‐line treatment for infant haemangiomas, which ensures effectiveness treatment with a wide margin of safety.2, 4, 5 While controversy still exists concerning the safety of systemic propranolol as there have been some studies reporting the occurrence of such severe adverse effects as bronchial asthma, hypotension, hyperkalaemia and hypoglycaemia.6, 7, 8 A few reports have demonstrated that topical propranolol or topical timolol provides an effective and safe alternative to oral propranolol in the treatment of SIH. In the 2015 recommendations made by an European expert group, it was stated that topical β‐blockers have the potential to become the first‐line treatment for superficial and small haemangiomas.9 However, due to lack of adequate evidence to prove the effectiveness and safety of topical β‐blockers, they are not suitable for recommendation as a standard therapy to treat infant haemangiomas.9 Therefore, a thorough review was conducted in this study of the existing literature focus on the treatment of SIH, to evaluate how safe oral propranolol would be in the treatment of SIH. Moreover, a meta‐analysis was conducted to compare the effectiveness and safety of topical β‐receptor blockers with other therapies.

2. METHODS

2.1. Literature search

A systematic search of literature (up to October 2019) was conducted to identify relevant studies on topical β‐blockers in the treatment of SIH by using PubMed, Embase, Cochrane Review database, China National Knowledge Infrastructure and Wanfang database. The search was conducted using the search terms: haemangioma and (adrenergic β‐antagonists or propranolol or timolol or metoprolol or atenolol). Besides, the reference lists of eligible articles were also searched.

2.2. Study selection

The studies were required to meet the following major criteria: (i) randomized controlled trial (RCT) or cohort study (CS); (ii) SIH; (iii) topical β‐blocker vs other monotherapy or observation in the treatment of SIH; (iv) the efficacy or safety of propranolol and other treatments were assessed in the treatment of SIH. In cases where the same study was published multiple times, only 1 study containing the maximum number of samples and information was included. Abstracts and unpublished reports were excluded.

2.3. Data extraction

The following data obtained from studies were extracted by 2 reviewers independently: last name of the first author, year of publication, design of the study, ages, duration of treatment, regimen and dose, sample sizes, diseased region, outcome, and adverse events. Any disagreement of data extraction was discussed and resolved by consensus.

2.4. Outcomes of interest

We were interested in performing comparison of the effectiveness and safety of topical β‐blockers with placebo, observation, oral propranolol or topical imiquimod in the treatment of SIH.

2.5. Adjudication of outcomes

There are 2 methods to make assessment of medication treatment of SIH for its effectiveness. These methods are as follows:

Haemangioma regression was evaluated on a 4‐point scale as follows: class IV, reduction in size of 75–100%; class III, reduction in size of 50– 75%; class II, reduction in size of 25–50%; class I, reduction in size of <25%. Classes III and IV were considered as effective treatment, and classes I and II were regarded as ineffective treatment.

Haemangioma response was evaluated based on a classification system as follows: class 3, the lesion of haemangiomas became softer, smaller and lighter in colour; class 2, the lesion of haemangioma stopped growing, with no significant change in colour, size or texture; class 1, the lesion of haemangiomas continued growth. Class 2 and class 1 were considered as ineffective in promoting regression, while class 3 was regarded as effective in promoting regression.

2.6. Quality assessment

The Cochrane Handbook was used to extract and assess the risk of bias of RCTs10: (i) The patients were allocated on a random basis; (ii) concealed allocation to treatment groups at the time of randomization; (iii) blind method for participants and personnel; (iv) blinding of outcome assessment (patient‐reported outcomes; detection bias); (v) blinding of outcome assessment (all‐cause mortality; detection bias); (vi) complete outcome data; and (vii) other bias. Each item was scored as score = 1 means that the criterion is met or score = 0 means that it fails to meet the criterion. A quality score from 0 to 7 was obtained by summing the standards. The Newcastle–Ottawa scale was applied to assess the quality of CSs, with a quality score ranging from 0 to 9 stars as obtained by summing the standards; a high‐quality CS was defined as having a minimum of 7 stars.

2.7. Statistical analysis

The meta‐analysis was conducted using Review Manager Software 5.3 (Nordic Cochrane Centre, UK) and Stata 15 (Stata Corporation, USA). Pooled odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) were calculated in the dichotomous outcomes. Random‐effect/fixed‐effect meta analytical techniques were applied for the analysis. I2 and χ2 tests were conducted to assess heterogeneity. I2 > 50% was regarded as substantial heterogeneity. The random‐effect model was applied when I2 > 50%; the fixed‐effect model would be used otherwise. A descriptive analysis of adverse drug reactions was conducted.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Study selection

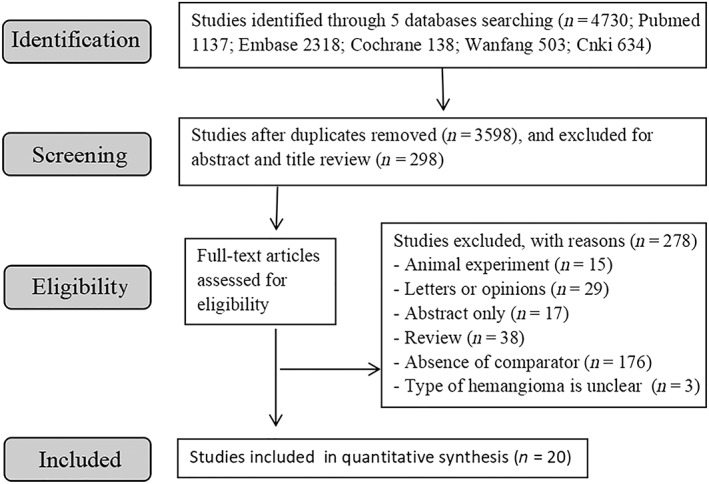

In total, 4730 studies were identified initially after the literature search, of which 20 studies met the inclusion criteria in this meta‐analysis (after duplicates removed).11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30 The selection process is shown in Figure 1, and the characteristics of the included reports are indicated in Tables 1 and 2.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the selection process for the studies

Table 1.

The characteristics of the 17 eligible studies evaluating haemangioma regression

| Studies | Design | Age (mo) | Duration of treatment (mo) | Regimen and dose | n | Diseased region | Outcome | AE | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | II | III | IV | ||||||||

| Yu 201411 | RCT | 8.33 (1–12) | 6.37 (5–9) | Topical propranolol 1% ointment, twice daily | 21 | 14 face or neck, 2 trunk, 4 extremities, 3 buttock | 3 | 5 | 8 | 5 | 0 |

| 9.13 (3–12) | 4.33 (3–18) | Propranolol orally, 0.75 mg/kg, twice daily | 21 | 12 face or neck, 3 trunk, 6 extremities, 1 buttock | 2 | 2 | 5 | 12 | 2 | ||

| Lu 201312 | RCT | 3.8 (1.5–11) | NA | Topical propranolol 1% ointment, 2 or 3 times daily | 20 | 14 head and face or neck, 1 trunk, 3 extremities, 2 perineum | 3 | 7 | 8 | 2 | 5 |

| 3.4 (1–10) | NA | Propranolol orally, 1 mg/kg/d, 2 or 3 times daily | 20 | 10 head and face or neck, 4 trunk, 4 extremities, 2 perineum | 2 | 5 | 10 | 3 | 3 | ||

| Zhu 201713 | RCT | 3–19 | 3 | Topical propranolol 0.5% ointment, 3 times daily | 30 | 18 head and face or neck, 6 chest, 4 extremities, 2 multiple location | 1 | 6 | 12 | 11 | 3 |

| 3–19 | 3 | Propranolol orally, 2/3 mg/kg, 3 times daily | 30 | 20 head and face or neck, 5 chest, 4 extremities, 1 multiple location | 2 | 8 | 10 | 10 | 0 | ||

| Chen 201714 | RCT | 1–16 | NA | Topical propranolol ointment, 2 or 3 times daily | 20 | NA | 1 | 10 | 7 | 2 | 1 |

| 1–16 | NA | Propranolol orally, 2 mg/kg/d, 2 or 3 times daily | 18 | NA | 0 | 2 | 6 | 10 | 6 | ||

| Li 201515 | RCT |

1–11 |

NA | Topical 0.5% timolol maleate solution, twice daily | 40 | 35 head and face or neck, 22 extremities, 18 trunk, 3 perineum | 4 | 8 | 13 | 15 | 1 |

| NA | Observation | 31 | 20 | 7 | 4 | 0 | NA | ||||

| Chambers 201216 | CS | NA | 2 | Topical 0.25% timolol maleate gel, twice daily | 5 | 5 periocular | 0 | 5 | 0 | ||

| NA | 2 | Observation | 4 | 5 periocular | 4 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| Chen 201517 | RCT | 1–5 | 6 | Topical 0.5% timolol maleate solution, 3 times daily | 23 | NA | 3 | 6 | 12 | 2 | 1 |

| 1–5 | 6 | Saline solutions, 3 times daily | 23 | NA | 1 | 17 | 4 | 1 | NA | ||

| Wang 201718 | RCT | 1–12 | 6 | Topical 0.5% timolol maleate solution, twice daily | 40 | 24 head and face or neck, 10 extremities, 6 trunk | 4 | 7 | 21 | 8 | NA |

| 1–12 | 6 | Saline solutions, twice daily | 40 | 25 head and face or neck, 9 extremities, 16 trunk | 28 | 9 | 3 | 0 | NA | ||

| Yu 201719 | RCT | 1–8 | 6 | Topical 0.5% timolol maleate solution, twice daily | 42 | 47 head, 11 extremities, 19 trunk | 4 | 7 | 22 | 9 | 1 |

| 1–8 | 6 | Saline solutions, twice daily | 35 | 25 | 8 | 2 | 0 | NA | |||

| Wu 201820 | CS | 5.4 (mean) | 7.3 (mean) | Topical 0.5% timolol maleate hydrogel, 3 times daily | 362 | 200 head and neck, 84 extremities, 78 trunk | 13 | 43 | 170 | 136 | 12 |

| 6.1 (mean) | 6.0 (mean) | Oral propranolol, 2.0 mg/kg per day | 362 | 221 head and neck, 81 extremities, 60 trunk | 11 | 36 | 199 | 116 | 14 | ||

| Zhao 201621 | CS | 2–12 | 1–6 | Topical timolol, 0.5% ointment, 3 times daily | 57 | 65 head and face or neck, 12 extremities, 21 trunk, 9 perineum | 9 | 11 | 17 | 20 | 0 |

| 2–12 | 1–6 | Oral propranolol, 1.5–2.0 mg/kg/d | 50 | 8 | 11 | 13 | 18 | 0 | |||

| Zhang 201722 | CS | 2–18 | 6 | Topical timolol, 0.5% ointment, twice daily | 27 | 37 head and face or neck, 12 extremities and trunk, 1 perineum | 3 | 7 | 10 | 7 | 1 |

| 2–18 | 6 | Oral propranolol,1.5–2.0 mg/kg/d | 23 | 3 | 5 | 9 | 6 | 8 | |||

| Zhao 201323 | RCT | 4–13 | 6 | Topical timolol, 0.5% ointment, once daily | 71 | 105 head and face or neck, 7 extremities, 20 trunk, 9 perineum | 2 | 16 | 49 | 4 | 16 |

| 4–13 | 6 | Oral propranolol, 1 mg/kg once daily | 70 | 5 | 18 | 45 | 2 | 52 | |||

| Gong 201524 | RCT | 2–9 | 6 | Topical timolol, 0.5% ointment, twice daily | 13 | NA | 3 | 8 | 0 | ||

| 2–9 | 6 | Oral propranolol, 1.5 mg/kg once daily | 13 | NA | 2 | 9 | 3 | ||||

| Zhao 201625 | RCT | 1–12 | 3–6 | Topical timolol, 0.5% solution, twice daily | 25 | 19 head and face or neck, 4 extremities, 2 trunk | 3 | 3 | 6 | 12 | 0 |

| 1–12 | 3–6 | Topical 5% imiquimod cream, 3 times per week | 25 | 17 head and face or neck, 5 extremities, 3 trunk | 7 | 5 | 6 | 6 | 0 | ||

| Hu 201326 | CS | 1–9 | 4 | Topical timolol, 0.5% solution, once daily | 54 | 20 head and face or neck, 13 extremities, 9 trunk | 41 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 12 |

| 1–9 | 4 | Topical 5% imiquimod cream, once every other day | 54 | 44 | 5 | 3 | 2 | 34 | |||

| Qiu 201327 | CS | 1–4.5 | 2–7 | Topical timolol, 0.5% solution, once daily | 20 | 12 head and face or neck, 4 extremities, 4 trunk | 1 | 0 | 4 | 15 | 0 |

| 1–8.5 | 2–7 | Topical 5% imiquimod cream, once every other day | 20 | 12 head and face or neck, 4 extremities, 4 trunk | 2 | 2 | 3 | 13 | 13 | ||

NA, not reported; AE, adverse events; CS, cohort study; RCT, randomized controlled trial.

Table 2.

The characteristics of the 4 eligible studies evaluating haemangioma response

| Studies | Design | Age (mo) | Duration of treatment (mo) | Regimen | n | Diseased region | Outcome | AE | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Class 1 | Class 2 | Class 3 | ||||||||

| Luo 201328 | CS | 1–12 | 3 | Topical timolol maleate solution, 3 times daily | 89 | 51 head and face, 22 extremities, 16 trunk | 7 | 31 | 51 | 0 |

| 1–12 | 3 | Observation | 20 | NA | 13 | 6 | 1 | NA | ||

| Yu 201529 | CS | 1–18 | 6 | Topical timolol maleate solution, 3–4 times daily | 176 | 87 head and face or neck, 54 extremities, 22 trunk, 13 perineum | 14 | 60 | 102 | 4 |

| 2–11 | 6 | Observation | 34 | NA | 17 | 13 | 4 | NA | ||

| Chambers 201216 | CS | NA | 2 | Topical 0.25% timolol maleate gel, twice daily | 5 | NA | 0 | 0 | 5 | 0 |

| NA | 2 | Observation | 4 | NA | 3 | 0 | 1 | NA | ||

| Yu 201330 | CS | 1–12 | NA | Topical 0.5% timolol maleate solution, 3 times daily | 101 | 65 head and face or neck, 27 extremities, 32 trunk | 8 | 36 | 57 | 0 |

| 1–12 | NA | Observation | 23 | 15 | 7 | 1 | NA | |||

NA, not reported; AE, adverse events; CS, cohort study

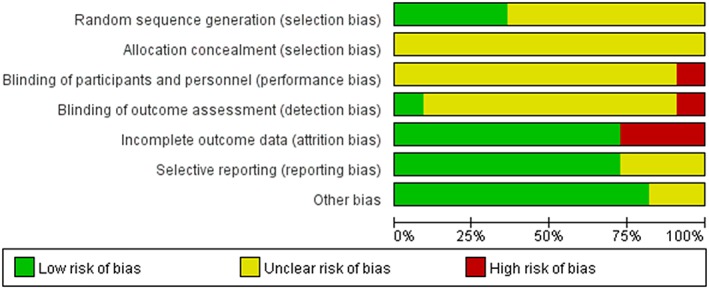

3.2. Quality assessment

The quality of RCTs was evaluated by assessing the risk of bias as summarized in Figure 2. All fully published studies were of comparable quality with their quality scores ranging from 2 to 6. Most of the included RCTs demonstrated high and moderate quality with a low risk of bias. The quality of CSs was evaluated as shown in Table 3. All the included CSs demonstrated the high‐quality with a minimum of 7 stars.

Figure 2.

Summary table of review authors' judgements for each risk of bias item for each randomized controlled trial

Table 3.

The quality of cohort studies

4. POOLED ANALYSES

4.1. Meta‐analysis on the effectiveness of topical β‐blockers vs oral propranolol, topical imiquimod, topical saline solutions and observation in SIH

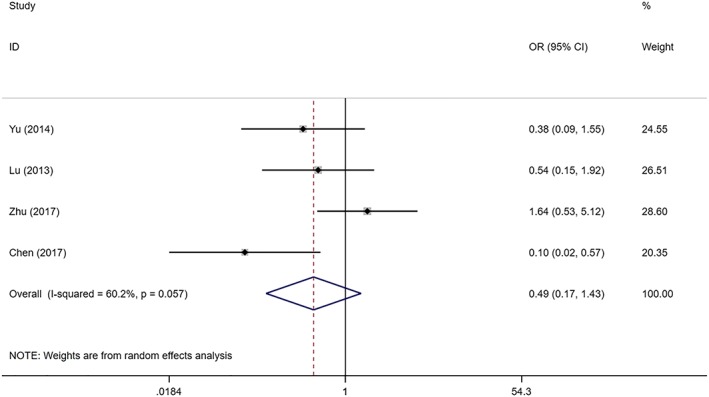

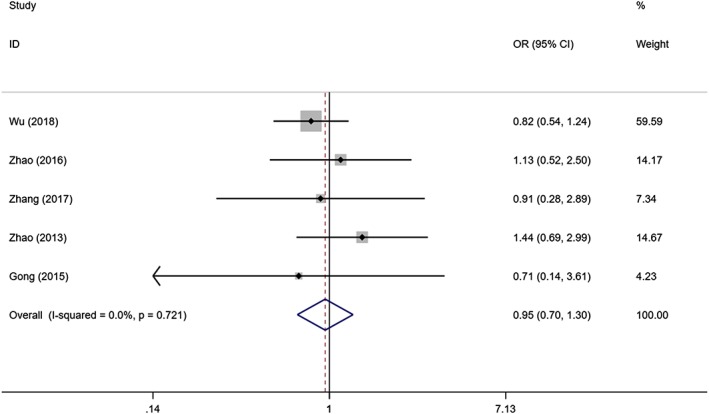

4.1.1. Topical β‐blockers vs oral propranolol

Four studies with 91 SIH patients and 89 controls compared the effectiveness of topical propranolol and oral propranolol in the treatment of SIH. There was substantial heterogeneity among the studies (I2 = 60.2%, P = .057). As revealed by the combined results, topical propranolol was as effective as oral propranolol in the treatment of SIH (OR = 0.486; 95%CI 0.165, 1.426, P = .189; Figure 3). Five studies with 530 SIH patients and 518 controls compared the effectiveness of topical timolol with oral propranolol. There was no significant heterogeneity among the studies (I2 < 0.1%, P = .721). The combined results demonstrated that topical timolol was as effective as oral propranolol in treating SIH (OR = 0.955; 95%CI 0.700, 1.302; P = .769; Figure 4).

Figure 3.

Forest plot of the efficacy of topical propranolol compared with oral propranolol in the treatment of superficial infantile haemangioma

Figure 4.

Forest plot of the efficacy of topical timolol compared with oral propranolol in the treatment of superficial infantile haemangioma

4.1.2. Topical β‐blockers vs topical imiquimod

Three studies involving 99 SIH cases and 99 controls evaluated the effectiveness of topical timolol and topical imiquimod. There was no evidence of heterogeneity among the studies (I2 < 0.1%, P = .778). As demonstrated by the combined results, topical timolol was more effective than topical imiquimod in the treatment of SIH (OR = 2.561; 95%CI 1.182, 5.550; P = .017).

4.1.3. Topical timolol vs observation

Two studies involving 45 SIH cases and 35 controls evaluated the effectiveness of topical timolol and observation. There was no significant heterogeneity among the studies (I2 < 0.1%, P = .402). As revealed by the combined results, topical timolol was more effective than observation in treating SIH (OR = 18.458; 95%CI 5.660, 60.191; P < .001).

Four studies involving 371 SIH cases and 81 controls evaluated the regression rate of topical timolol and observation. There was no significant heterogeneity discovered among the studies (I2 < 0.1%, P = .751). The combined results demonstrated that topical timolol achieved a higher regression rate compared to observation in the treatment of SIH (OR = 16.195; 95%CI 7.006, 37.435; P < .001).

4.1.4. Topical timolol vs topical saline solutions

Three studies involving 105 SIH cases and 98 controls evaluated the effectiveness of topical timolol and topical saline solutions. There might be moderate heterogeneity among the studies (I2 = 61.8%, P = .073). As demonstrated by the combined results, topical timolol was more effective than topical saline solutions in the treatment of SIH (OR = 19.193; 95%CI 8.837, 41.683; P < .001).

4.2. Meta‐analysis on the safety of topical β‐blockers vs oral propranolol, and topical imiquimod in SIH

The most common adverse effects caused by oral propranolol include stomach and intestinal disorders, night‐time crying, cyanotic lips and descent of heart rate, most of which are classed as systemic adverse reactions (Table 4). The adverse effects caused by topical propranolol include eczema, ulcer and skin rash, most of which fall into the category of localized adverse reactions. The adverse effects caused by localized treatment with topical timolol include desquamation, nocturnal crying and Erythema, and most of which are classed as localized adverse reactions (Table 5). It is possible that the localized treatment with imiquimod could cause different adverse effects at the same time, with such common complications as eczema, peeling and ulcer, and most of them are classed into localized adverse reaction.

Table 4.

Adverse reactions of oral propranolol

| Adverse reaction | No. cases (n = 365) |

|---|---|

| Nocturnal crying | 25 (6.79%) |

| Gastrointestinal disturbance | 24 (6.58%) |

| Cyanosis around the mouth | 9 (2.47%) |

| Heart rate reduction or hypotension | 7 (1.92%) |

| Sleep disorder | 5 (1.37%) |

| Lethargy and loss of appetite | 2 (0.55%) |

| Hypoglycaemia | 1 (0.27%) |

| Wheeze | 1 (0.27%) |

Table 5.

Adverse reactions of topical timolol

| Adverse reaction | No. cases (n = 765) |

|---|---|

| Desquamation | 10 (1.31%) |

| Nocturnal crying | 9 (1.18%) |

| Erythema | 7 (0.92%) |

| Diarrhoea | 6 (0.78%) |

| Eczema | 3 (0.39) |

| Cyanosis around the mouth | 1 (0.13%) |

| Ulcer | 1 (0.13%) |

| Skin redness | 1 (0.13%) |

| Crusting | 1 (0.13%) |

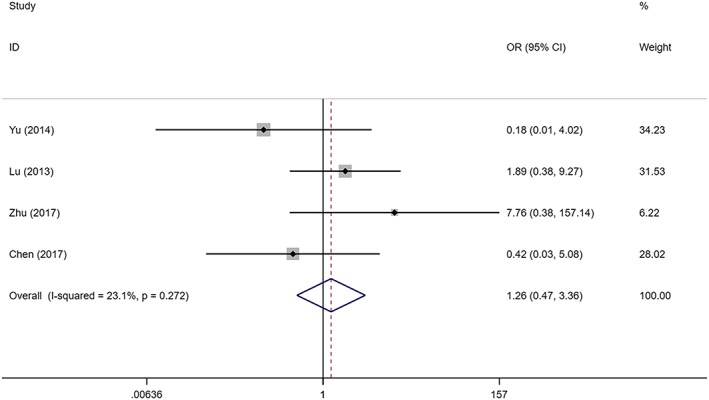

Four studies with 91 SIH patients and 89 controls evaluated topical propranolol and oral propranolol for their safety. Heterogeneity among the studies was not remarkable (I2 = 23.1%, P = .272). As demonstrated by the combined results, there was no significant difference in the incidence of adverse effects when topical propranolol was compared against the oral propranolol in the treatment of SIH (OR = 1.258; 95%CI 0.471, 3.358; P = .647; Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Forest plot of the safety of topical propranolol compared with oral propranolol in the treatment of superficial infantile haemangioma

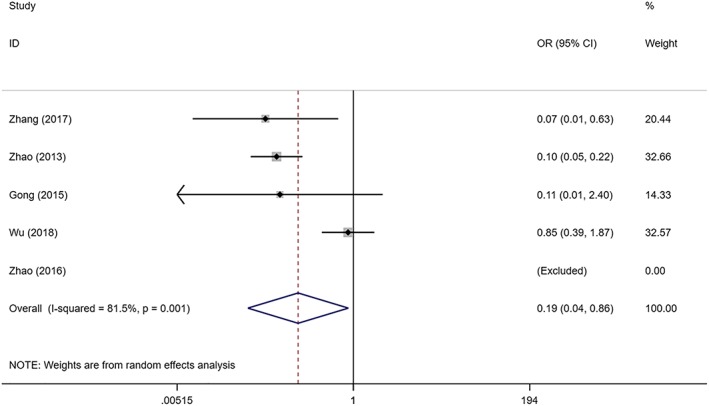

Five studies with 530 SIH patients and 518 controls evaluated the safety of topical timolol and oral propranolol. It was speculated that there was substantial heterogeneity among the studies (I2 = 81.5%, P = .001). The combined results demonstrated that topical timolol led to fewer incidence of adverse effects when compared with oral propranolol in treating SIH (OR = 0.191; 95%CI 0.043, 0.858; P = .031; Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Forest plot of the safety of topical timolol compared with oral propranolol in the treatment of superficial infantile haemangioma

Three studies involving 99 SIH cases and 99 controls evaluated the safety of topical timolol and topical imiquimod. It was speculated that there was substantial heterogeneity among the studies (I2 = 70.8%, P = .064). No significant difference in the incidence of adverse effects was found when topical timolol and topical imiquimod were compared (OR = 0.077; 95%CI 0.005, 1.206; P = .068). This was probably performed by the use of random‐effects model, which added to the difficulty in identifying significant differences in safety between topical timolol and topical imiquimod.

5. DISCUSSION

Propranolol therapy is considered the first‐line treatment for infantile haemangiomas in recent years; it is an effective treatment with fewer adverse effects.2, 4, 5 However, some serious adverse events have been reported, such as bronchial asthma, severe hypotension and hypoglycaemia. Therefore, alternative topical β‐blocker treatments are being explored for SIH. However, to date, there is no report on large multicentre, double‐blind, randomized trials to validate the effectiveness and safety of β‐receptor blockers in the treatment of SIH. In consideration of this, we compared the effectiveness and safety of topical β‐receptor blockers against other therapies by conducting a meta‐analysis. The major finding was that topical timolol was as effective as oral propranolol and more effective than imiquimod by comparing the response rate in the treatment of SIH, and topical timolol resulted in lower incidence of adverse events when compared with oral propranolol.

Infant haemangiomas show a well‐known natural history that can be separated histologically and clinically into at least 2 dynamic evolutionary phases: proliferation and involution. Localized blanching or localized macular telangiectatic erythema is regarded as the precursor of proliferating phase.1, 31 As the proliferation of haemangioma endothelial cells continues, the infant haemangioma becomes more elevated, which leads to a rubbery consistency.1, 31 As time passes, haemangiomas will come into involution, the infantile haemangioma softens, shrinks from the centre outward, and changes to less red in colour. The involution has a possibility to end up causing residual skin changes, including anetoderma, and redundant and fibrofatty skin.1, 31 Propranolol and timolol are classed as non‐selective receptors suspected to have a similar mechanism in the treatment of infantile haemangioma. The antihypertensive timolol was approximately 4 times as effective as propranolol,32 and the duration of cardiac effects was roughly 10 times as effective as propranolol.33 The exact mechanism of β‐receptor blocker therapy of infant haemangiomas is not fully understood so far. Timolol and propranolol are speculated to have a similar mechanism in the treatment of infantile haemangioma. The potential mechanisms are as follows: propranolol may cause blood vessels of infant haemangioma to contract by blocking adrenergic receptor and inhibiting the activity of endothelial nitric oxide synthase; propranolol may inhibit the angiogenesis of haemangioma by inhibiting the activity of vascular endothelial growth factor, matrix metalloproteinase‐9 and hypoxia inducible factor‐1α34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39; Propranolol has a potential to promote the apoptosis of haemangioma cells by inhibiting Renin Angiotensin System Activation and activating the expression of cysteine aspartate protease 3 (Caspase 3) and Caspase 9.40, 41

Imiquimod is a nucleoside analogue of imidazoquinoline family that plays an important role in the induction of chemokines, proinflammatory cytokines and other mediators by inhibiting activity towards toll‐like receptors 7 and 8, and imiquimod has important antitumour activity. In some studies, the use of imiquimod usually produces satisfactory outcomes in the treatment of SIH. However, in our meta‐analysis, topical timolol was found to be more effective than topical imiquimod (OR = 2.561; 95%CI 1.182, 5.550; P = .017) in treating SIH.

In general, the frequency of timolol treatment varies from 1 to 3 times per day. Qiu et al.42 suggested that performing timolol treatment 5 or 6 times per day may produce a more desirable effect than if it is carried out 3 times on a daily basis, without any exacerbation of the adverse effects. It is also believed that the dosage of timolol bears no association with the effectiveness of treatment. However, due to a small number of research samples (n = 107),42 this remains to be confirmed. To our knowledge, a comparison of the effectiveness and safety of different timolol formulations has not been previously reported, and there is still no unified standard for the dosage and application rates of timolol treatment. Formulations, dose concentrations and application rates of timolol were not considered in the research due to the small number of related studies, which might give rise to a potential bias. In addition, dosage was not considered either, since the most appropriate dosage of oral propranolol varied from 1 population to another, which might also result in a potential bias. Moreover, most of the included studies did not indicate the use of the blind method, which might give rise to a potential bias. By contrast, limited related studies and cases were included, so these observations should be further confirmed in the double‐blinded, multicentre and RCTs.

In conclusion, this meta‐analysis provided evidence that topical β‐receptor blocker (propranolol and timolol), especially timolol, may replace oral propranolol as a first‐line treatment for SIH.

COMPETING INTERESTS

There are no competing interests to declare. No outside funding was provided for this analysis.

Lin Z, Zhang B, Yu Z, Li H. The effectiveness and safety of topical β‐receptor blocker in treating superficial infantile haemangiomas: A meta‐analysis including 20 studies. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2020;86:199–209. 10.1111/bcp.14196

PI statement: The authors confirm that the Principal Investigator for this paper is Lin Zhenying and that he had direct clinical responsibility for patients.

REFERENCES

- 1. Greenberger S, Bischoff J. Infantile hemangioma‐mechanism(s) of drug action on a vascular tumor. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2011;1:1‐10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Yun YJ, Gyon YH, Yang S, Lee YK, Park M. A prospective study to assess the efficacy and safety of oral propranolol as first‐line treatment for infantile superficial hemangioma. Korean J Pediatr. 2015;58(12):484‐490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Léauté‐Labrèze C, Dumas de la Roque E, Hubiche T, Boralevi F, Thambo JB, Taïeb A. Propranolol for severe hemangiomas of infancy. N Engl J Med. 2008;24:2649‐2651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Sharma VK, Fraulin FO, Dumestre DO, Walker L, Harrop AR. Beta‐blockers for the treatment of problematic hemangiomas. Can J Plast Surg. 2013;21(1):23‐28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Nguyen HP, Pickrell BB, Wright TS. Beta‐blockers as therapy for infantile hemangiomas. Semin Plast Surg. 2014;28(2):87‐90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Holland KE, Frieden IJ, Frommelt PC, Mancini AJ, Wyatt D, Drolet BA. Hypoglycemia in children taking propranolol for the treatment of infantile hemangioma. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:775‐778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Stringari G, Barbato G, Zanzucchi M, et al. Propranolol treatment for infantile hemangioma: a case series of sixty‐two patients. Pediatr Med Chir. 2016;38:69‐74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kim SK, Yun SJ, Kim SJ, Lee SC, Won YH, Lee JB. The efficacy and adverse effects of propranolol in the treatment of infantile hemangiomas. Korean J Dermatol. 2013;51:698‐704. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hoeger PH, Harper JI, Baselga E, et al. Treatment of infantile haemangiomas: recommendations of a European expert group. Eur J Pediatr. 2015;174(7):855‐865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Higgins JP, Green S. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. New Jersey: The Cochrane Collaboration; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Yu QP, Li H, Yu HX, Wang PP, Niu JJ. Comparison of oral and topical propranolol in the treatment of infantile strawberry hemangiomas. Chin J Leprosy Skin Dis. 2014;30:671‐673. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lu YC. Clinical observation and plasma concentration monitoring of propranolol gel on infantile hemangiomas. Fujian Med Univ. 2013;07:1‐45. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Zhu YL, Tan SJ. Efficacy and safety of propranolol hydrochloride gel in the external application treatment on superficial hemangioma in infants. Guangzhou Med J. 2017;6:40‐42. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Chen JW, Yuan B, Zhang ZZ, et al. Efficacy and safety of different routes of administration of propranolol in superficial and small infantile hemangioma. Chin J Clin Res. 2017;5:639‐641. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Li W, Chen W, Liu XH, Wang WJ. Treatment of infantile hemangiomas with timolol eye drops: a series of 40 cases. Shaanxi Med J. 2015;10:1406‐1407. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Chambers CB, Katowitz WR, Katowitz JA, Binenbaum G. A controlled study of topical 0.25% Timolol maleate gel for the treatment of cutaneous infantile capillary hemangiomas. Ophthal Plast Recons. 2012;28:103‐106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Chen YL. Clinical observation of timolol maleate in the treatment of superficial hemangioma in infants. Chin Med Cosmetol. 2015;5:89‐90. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Wang J, Zhao JH. Observation of therapeutic effect of Timolol maleate eye drops on superficial hemangioma in infants. Inner Mongolia Med J. 2017;49:1422‐1424. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wu HW, Wang X, Zhang L, Zheng JW, Liu C, Wang YA. Topical Timolol vs. Oral propranolol for the treatment of superficial infantile hemangiomas. Front Oncol. 2018;8:1‐6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Yu MM, Gong WP. Effect of timolol maleate eye drops on superficial hemangioma in infants. Chin J Rural Med Pharm. 2017;24:28‐29. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Zhao YM. Evaluation of the efficacy and safety of topical timolol and oral propranolol in the treatment of superficial infantile hemangiomas. Chin Baby. 2016;15:105‐105. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Zhang KC, Xu DP, Cheng MS, Wang XK. Evaluation of the efficacy and safety of 0.5% timolol maleate solution or oral propranolol in the treatment of superficial infantile hemangiomas. Chin J Oral Maxil Surg. 2017;15:529‐533. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Zhao Q, Liu X, Chen X, Yang WC. Efficacy and safety of topical timolol in the treatment of superficial hemangiomas in infants. Shandong Med J. 2013;53:86‐87. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Gong H, Xu DP, Li YX, Cheng C, Li G, Wang XK. Evaluation of the efficacy and safety of propranolol, timolol maleate, and the combination of the two, in the treatment of superficial infantile haemangiomas. Brit J Oral Max Surg. 2015;53:836‐840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Zhao H, Guo G, Liu G, Li JX, Cui XQ. Timolol eye drops in treatment of infantile hemangioma. Chin J New Drugs Clin re. 2016;11:36‐38. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hu L, Wei L, Ma G, et al. Treatment of proliferating superficial infantile hemangioma with imiquimod and timolol maleate. Chin J Aesth Plast Surg. 2013;24:607‐611. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Qiu Y, Ma G, Yang J, et al. Imiquimod 5% cream versus timolol 0.5% ophthalmic solution for treating superficial proliferating infantile haemangiomas: a retrospective study. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2013;38(8):845‐850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Luo CF, Li SM, Su BL, et al. Safety and short‐term efficacy of timolol for the treatment of superficial infantile hemangiomas. Chin J Pediatr Surg. 2013;34:241‐244. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Yu LJ, Xu JC, Su BL, Xiong QX, Luo CF. A clinical study of Timolol maleate eye drops for the treatment of superficial infantile hemangiomas. Chin J Plast Surg. 2015;31:440‐445. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Yu LJ, Li SM, Su BL, et al. Treatment of superficial infantile hemangiomas with timolol: evaluation of short‐term efficacy and safety in infants. Exp Ther Med. 2013;6(2):388‐390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Darrow DH, Greene AK, Mancini AJ, Mancini AJ. Diagnosis and Management of Infantile Hemangioma. Pediatrics. 2015;136(4):786‐791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Georg L, Frohlich ED. A comparison of timolol and propranolol in essential hypertension. Am Heart J. 1975;89:437‐442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Achong MR, Piafsky KM, Ogilvie RI. Duration of cardiac effects of timolol and propranolol. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1976;2:148‐152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Zhang L, Mai HM, Zheng J, et al. Propranolol inhibits angiogenesis via down‐regulating the expression of vascular endothelial growth factor in hemangioma derived stem cell. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2013;42:1286‐1286. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Chim H, Armijo BS, Miller E, Gliniak C, Serret MA, Gosain AK. Propranolol induces regression of hemangioma cells through HIF‐1α mediated inhibition of VEGF‐A. Ann Surg. 2016;256:146‐156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Pan WK, Li P, Guo ZT. Propranolol induces regression of hemangioma cells via the down‐regulation of the PI3K/Akt/eNOS/VEGF pathway. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2015;62(8):1414‐1420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Thaivalappil S, Bauman N, Saieg A, Movius E, Brown KJ, Preciado D. Propranolol‐mediated attenuation of MMP‐9 excretion in infants with hemangiomas. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2013;139(10):1026‐1031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Annabi B, Lachambre MP, Plouffe K, Moumdjian R, Béliveau R. Propranolol adrenergic blockade inhibits human brain endothelial cells tubulogenesis and matrix metalloproteinase‐9 secretion. Pharmacol Res. 2009;60(5):438‐445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Zou HX, Jun J, Zhang WP, Sun ZJ, Zhao YF. Propranolol inhibits endothelial progenitor cell homing: a possible treatment mechanism of infantile hemangioma. Cardiovasc Pathol. 2013;22(3):203‐210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Arneja JS. Pharmacologic therapies for infantile hemangioma: is there a rational basis? Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012;128:499‐507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Ji Y, Li K, Xiao XM, Zheng S, Xu T, Chen SY. Effects of propranolol on the proliferation and apoptosis of hemangioma‐derived endothelial cells. J Pediatr Surg. 2012;47(12):2216‐2223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Qiu YJ, Chen MY, Chang L, et al. Effect of Timolol maleate gel‐forming solution in the treatment of superficial infantile hemangiomas: a prospective, randomized, double‐blind, controlled trial. J Tissue Eng Reconstr Surg. 2014;4:203‐206. [Google Scholar]