Abstract

Background

Omega-5-gliadin (O5G) allergy, also known as wheat-dependent exercise-induced anaphylaxis, is commonly reported in the Western, but not Asian, populations. Although significant differences in O5G allergy presentation across different populations are likely but there have been no previous reports on this important topic.

Objective

To report on the prevalence and characteristics of O5G allergy in Hong Kong (HK) compared with the United Kingdom (UK).

Methods

O5G allergy patients attending Queen Mary Hospital (HK cohort), and Guy's and St Thomas' Hospital, London (UK cohort) were studied and compared.

Results

A total of 46 O5G allergy patients (16 HK; 30 UK) were studied. In the HK cohort, 55% of all patients previously labeled as “idiopathic anaphylaxis” were diagnosed with O5G allergy. Exercise was the most common cofactor in both cohorts, followed by alcohol and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAID). A higher proportion of the HK cohort reported NSAID as a cofactor (13% vs. 0%, p = 0.048). In the HK cohort, more patients presented with urticaria and cardiovascular manifestations (100% vs. 77%, p = 0.036; 100% vs. 70%, p = 0.015, respectively); the range of presentation was more diverse in the UK cohort. In HK fewer patients adhered to wheat avoidance (50% vs. 87%, p = 0.007) and more patients avoided cofactors only (44% vs. 10%, p = 0.008).

Conclusion

O5G allergy appears relatively underdiagnosed in HK. Urticaria and cardiovascular manifestations are common; NSAID plays an important role as a cofactor and patients are less concordant with dietary avoidance measures than in the Western population.

Keywords: Allergy, Wheat, Cofactor, Food, Anaphylaxis

INTRODUCTION

The diagnosis of food-dependent exercise-induced anaphylaxis (FDEIA), a subset of exercise-induced anaphylaxis (EIA), can be difficult and often overlooked. Omega-5-gliadin (O5G) allergy, a type of FDEIA as known as wheat-dependent EIA, is mediated by specific IgE (sIgE) antibodies against this wheat component. It is one of the most common and studied forms of FDEIA and an increasingly recognized cause of anaphylaxis [1,2]. Severe systemic manifestations usually occur when wheat is consumed in the presence of cofactors such as exercise, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), alcohol or infections [3]. Despite the potentially fatal consequences of anaphylaxis, the prevalence and burden of FDEIA remain unknown, especially in allergist-deficient regions such as Hong Kong (HK) [4].

Even though O5G allergy was first described by a Japanese group in the 1980s the majority of cases have been reported from the West [5]. Indeed, the first published report in HK was not until 2017 [6]. Similar to other immunological and allergological conditions, significant clinical differences can be expected between O5G allergy patients from different populations. They can be attributed to a number of variables including genetics, dietary preferences, cultural differences, environmental factors, disease awareness and access to healthcare [7]. There have been no previous reports comparing O5G allergy patients across different populations and ethnicities. Studies of interethnic heterogeneity are especially important in the era of personalized medicine; extrapolation of data from western cohorts may not reflect real-life observations in the Chinese patients. This study is the first to report on the prevalence and characteristics of O5G allergy in HK Chinese and the clinical differences compared to a large cohort of patients from the UK.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

All available medical records of patients attending the Immunology and Allergy specialist clinics of Queen Mary Hospital (HK) from May 2018 to October 2019 were reviewed and patients with O5G allergy were analyzed (hereafter referred to as the “HK cohort”). Since mid-2018, Queen Mary Hospital has been the only referral centre with a formal immunology/allergy service under HK's public health system (the Hospital Authority) which provides about 90% of inpatient care in HK [8]. It receives allergy referrals from across the entire territory and patients represent the general population of HK referred for anaphylaxis during the study period. Similarly, all available medical records of O5G allergy patients referred to Guy's and St Thomas' National Health Service Foundation Trust (London, UK) between November 2016 to September 2019 were reviewed and analyzed (hereafter referred to as the “UK cohort”). All O5G allergy patients met all of the following for diagnosis: (1) compatible clinical history of O5G allergy: ingestion of wheat together with a cofactor (e.g., exercise, NSAIDs, alcohol) ≤4 hours prior to reaction, (2) specific IgE (sIgE) to O5G (≥0.35 KUA/L), and (3) fulfilled criteria for anaphylaxis according to the European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology [9].

For all O5G allergy patients, the following anonymous data was collected: demographics (including age, sex, ethnicity); history of asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, chronic urticaria (>6 weeks); concomitant food allergy, working diagnosis prior to allergy consultation, clinical manifestation (urticaria, angioedema, respiratory manifestations [dyspnea, wheeze, stridor, hypoxemia], gastrointestinal manifestations [nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain], or cardiovascular manifestations [hypotension, dizziness, presyncope, syncope]), investigation results (skin prick tests [SPTs] to wheat and sIgE to O5G and wheat), reported cofactors, time between wheat ingestion and cofactor exposure, delay in diagnosis of O5G allergy and patient self-reported avoidance measures. Wheat SPT was performed with an Inmunotek (Madrid, Spain) (HK) and Allergopharma (Darmstadt, Germany) solutions (UK). sIgE measurements were performed using ImmunoCAP (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA, USA). Hospitalization records and prescription data for adrenaline autoinjectors (AAIs) prior to referral were available for the HK cohort only and extracted anonymously.

Written consent or ethical clearance for this retrospective anonymized study was not required according to the UK law. All data collected was obtained solely for clinical reasons and no patient-identifiable information was available to clinicians who were not part of the clinical care team.

Association analysis was performed to study the differences in clinical characteristics between the UK and HK cohorts. Categorical variables were expressed as number (percentage) and continuous variables as median (standard error of the mean when appropriate). Chi-square test and independent samples t test were used to compare categorical and continuous variables between cohorts, respectively. A p value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. IBM SPSS Statistics ver. 20.0 (IBM Co., Armonk, NY, USA) was used for all analyses.

RESULTS

Prevalence of O5G allergy and AAI prescriptions in HK

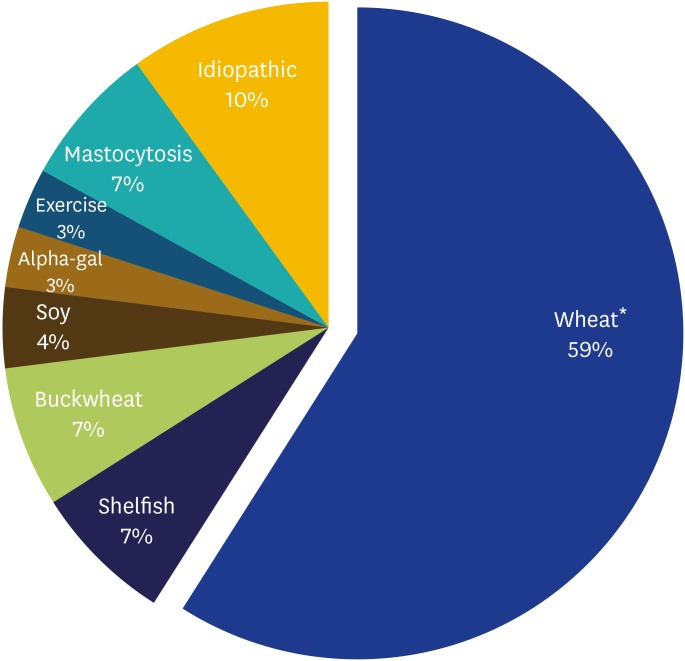

During the 18-month study period, 221 patients attended Queen Mary Hospital for a specialist Immunology & Allergy consultation. Over 10% (29 of 221) were referred for “idiopathic anaphylaxis” i.e., anaphylaxis without an identifiable cause. After thorough allergy workup, specific etiologies were identified in 90% (26 of 29) of these patients (Fig. 1). The majority (59%, 17 of 29) were diagnosed with wheat-related anaphylaxis: O5G allergy in 94% (16 of 17) and a primary wheat allergy in 6% (1 of 17). One hundred percent of O5G allergy patients had attended hospital for anaphylaxis on more than one occasion prior to first consultation. Only 31% of O5G allergy patients were prescribed an AAI prior to allergy consultation.

Fig. 1. Pie chart showing etiologies of previously labeled “idiopathic anaphylaxis” in Hong Kong (n = 29). *Out of 17/29 cases of wheat-related anaphylaxis, 16 were omega-5-gliadin allergy, and 1 was primary wheat allergy.

Clinical characteristics of HK vs. UK O5G allergy patients

The patient characteristics, cofactors, clinical manifestations, and investigation results of O5G allergy patients are shown in Table 1. The entire HK cohort was Chinese; only 1 patient was Chinese in the UK cohort. Otherwise, both cohorts were similar. There was an almost equal male to female ratio and median age at presentation (34 years). There were no significant differences in delay in diagnosis, comorbidities of asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, chronic urticaria or other food allergies. All O5G allergy patients had positive sIgE to O5G and there was no difference in the rate of SPT positivity or absolute sIgE values for wheat/O5G.

Table 1. Association analysis of patient characteristics, cofactors, clinical manifestations and investigation results of omega-5-gliadin allergy patients in Hong Kong (HK) and United Kingdom (UK).

| Characteristic | Combined (n = 46) | HK Cohort (n = 16) | UK Cohort (n = 30) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male sex | 23 (50) | 10 (63) | 13 (43) | 0.216 | |

| Age of onset (yr) | 34 (16–69) | 34 (16–69) | 34 (17–69) | 0.988 | |

| Chinese ethnicity | 17 (37) | 16 (100) | 1 (3) | <0.001* | |

| Asthma or COPD | 4 (9) | 1 (6) | 3 (10) | 0.667 | |

| Other suspected food allergies | 9 (20) | 4 (25) | 5 (17) | 0.497 | |

| Chronic urticaria | 18 (39) | 6 (38) | 12 (40) | 0.869 | |

| Delay in diagnosis (yr) | 2 (0–37) | 5 (0–20) | 1.5 (0–37) | 0.837 | |

| Cofactors | |||||

| Exercise | 43 (94) | 16 (100) | 27 (90) | 0.191 | |

| Alcohol | 13 (28) | 2 (13) | 11 (37) | 0.083 | |

| NSAID | 2 (4) | 2 (13) | 0 (0) | 0.048* | |

| Time between wheat ingestion and cofactor exposure (min) | 30 (0–480) | 17.5 (15–60) | 60 (0–480) | 0.079 | |

| Clinical manifestations | |||||

| Urticaria | 39 (85) | 16 (100) | 23 (77) | 0.036* | |

| Angioedema | 13 (28) | 5 (31) | 8 (27) | 0.742 | |

| Respiratory manifestations | 14 (30) | 5 (31) | 9 (30) | 0.930 | |

| Gastrointestinal manifestations | 5 (11) | 3 (19) | 1 (3) | 0.077 | |

| Cardiovascular manifestations | 37 (80) | 16 (100) | 21 (70) | 0.015* | |

| Investigation results | |||||

| Wheat SPT positivity | 20 (63)§ | 9 (82)† | 11 (55)‡ | 0.135 | |

| Omega-5-gliadin sIgE (kUA/L) | 11.8 ± 1.65 | 12.61 ± 3.11 | 11.37 ± 1.95 | 0.738 | |

| Wheat sIgE (kUA/L) | 1.69 ± 0.63 | 1.14 ± 0.40 | 2.09 ± 1.05 | 0.682 | |

Values are presented as number (%), median (range), or mean ± standard deviation.

COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; NSAID, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug; SPT, skin prick test.

*p < 0.05, statistically significant difference. †SPT was performed in 11/16 patients. ‡SPT was performed in 20/30 patients. §SPT was performed in 31/46 patients.

Most common cofactor was exercise, more NSAIDs as cofactor in HK

O5G allergy patients often experience multiple episodes of anaphylaxis and report multiple cofactors. Exercise was the cofactor reported by all patients in the HK cohort and 90% of the UK cohort, followed by alcohol and NSAIDs. A significantly higher proportion of the HK cohort reported NSAIDs as cofactor than the UK cohort (13% vs. 0%, p = 0.048). There was no significant difference in the time intervals between wheat ingestion and cofactor exposure.

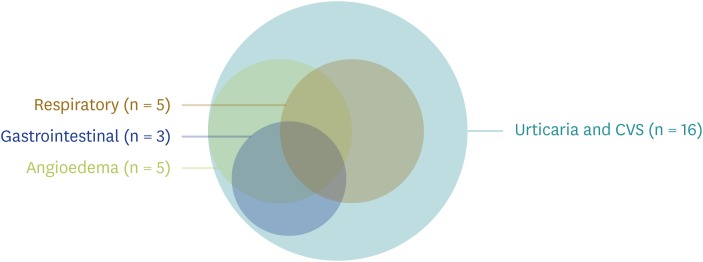

Urticaria and cardiovascular manifestations dominate in HK

The clinical manifestations in the HK and UK cohorts are presented as proportional Venn diagrams (Figs. 2, 3). All HK patients presented with both urticaria and cardiovascular manifestations. Around a third of them had concomitant angioedema and respiratory or gastrointestinal manifestations with various degrees of overlap. Although urticaria and cardiovascular manifestations also occurred in the majority of patients in the UK cohort, their occurrence was significantly lower than the HK cohort (100% vs. 77%, p = 0.036; 100% vs. 70%, p = 0.015, respectively) and there was a more diverse range, and with less overlap, of clinical manifestations (Fig. 3).

Fig. 2. Venn diagram depicting the frequency and overlap of clinical symptoms during index reactions of omega-5-gliadin allergy patients in Hong Kong (n = 16). CVS, cardiovascular system.

Fig. 3. Venn diagram depicting the frequency and overlap of clinical symptoms during index reactions of omega-5-gliadin allergy patients in United Kingdom (n = 30).

Lower adherence to wheat avoidance in HK cohort

On follow-up, adherence to wheat avoidance and/or cofactor avoidance was checked with all O5G allergy patients (Table 2). In comparison to the UK cohort, significantly fewer patients reported adherence to wheat avoidance (50% vs. 87%, p = 0.007) and significantly more patients were avoiding cofactors only (44% vs. 10%, p = 0.008). One patient from each cohort refused to avoid both wheat and cofactors (p = 0.063).

Table 2. Differences between avoidance measures and recurrence rate of omega-5-gliadin allergy patients in Hong Kong (HK) and United Kingdom (UK).

| Variable | Combined (n = 46) | HK Cohort (n = 16) | UK Cohort (n = 30) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Avoids wheat (and cofactors) | 34 (74) | 8 (50) | 26 (87) | 0.007 |

| Only avoids cofactors | 10 (22) | 7 (44) | 3 (10) | 0.008 |

| No avoidance | 2 (4) | 1 (6) | 1 (3) | 0.644 |

DISCUSSION

This is the first study to report on the prevalence and characteristics of O5G allergy in HK Chinese and the interethnic differences in clinical parameters across different populations.

Wheat-related anaphylaxis and O5G allergy made up around 60% of the “idiopathic anaphylaxis” cases in HK. No cases of O5G allergy were diagnosed prior to allergy consultation. Despite multiple episodes of hospitalization for anaphylaxis, only around 30% of O5G allergy patients were ever prescribed an AAI prior to allergy consultation – lower than reports from the western cohorts [10]. This might reflect lack of awareness of this condition and its potential severity among the public and physicians in HK.

This study identified important clinical differences among O5G allergy patients in the East (HK) versus West (UK). Clinicians should consider these important clinical differences as population-specific management and healthcare intervention may be warranted. Firstly, O5G allergy patients from the HK cohort presented with significantly more urticaria and cardiovascular manifestations. Furthermore, as shown in Figs. 2 and 3, there was also a much less diverse range of clinical presentations compared to the UK cohort. In fact, every patient in the HK cohort had presented with both urticaria and symptoms of cardiovascular involvement prior to referral for allergy review. Although an underlying biological explanation e.g., genetic predisposition for more severe manifestations in Chinese) is possible, a more likely explanation is the difference in referral threshold among physicians and the lack of access to allergists in HK [4]. It may be inferred that patients who do not present with ‘typical’ signs of allergy, such as urticaria or severe manifestations such as hypotension might not be recognized by physicians and thought not to warrant a specialist referral. Together with the alarmingly low AAI prescription rates despite multiple episodes of hospitalization of anaphylaxis for every O5G allergy patient this highlights the urgency of intervention in this locality. Future longitudinal and interventional studies are required to investigate these interethnic discrepancies.

Secondly, although exercise was the most common implicated cofactor, more O5G allergy patients from the HK cohort reported NSAID intake as a cofactor. Though the pathophysiology of O5G allergy is incompletely understood but it has been postulated that NSAID may affect gastrointestinal permeability and enhance absorption of O5G [11,12,13]. This observation may reflect a genuine susceptibility to NSAID in Asian patients, which echoes recent studies suggesting Asian ethnicity as a risk factor for a higher risk of bleeding complications with Aspirin [14]. Alternatively, it might be due to differences in prescribing practices or use of NSAID in the community. In HK, drug dispensing regulations are not strictly enforced and medications such as NSAIDS may be more easily accessible. For example, patients can often obtain some commonly used medications without prescriptions in independently owned pharmacies of HK [15]. The role of NSAID as a cofactor, especially in Asians, warrants further ethnicity-specific studies.

Finally, we also report a lower adherence to wheat avoidance in the HK cohort [2]. Every patient with a diagnosis of O5G allergy in both HK and UK cohorts were counselled to follow strict wheat avoidance (or adhere to a strict gluten-free diet) rather than avoiding cofactors alone [16]. However, only half of O5G allergy patients in the HK cohort self-reported adherence to strict dietary avoidance on follow-up, and significantly more likely to avoid cofactors only. This difference is likely due to a combination of patient insight (Chinese patients often do not believe in adult onset FDEIA) and the sheer difficulty to adhere to a wheat-free diet in HK. There is also a lack of allied health professionals, such dedicated allergy dietitians, to facilitate patient education and implementation. Unlike in the West, avoiding wheat or following a gluten-free diet is extremely difficult in Asian cuisines. For example, the lack of availability and considerably higher cost of gluten-free products remains a significant barrier for patients in HK. The problem is further compounded by inadequate food allergen labelling in restaurants. This highlights the need for greater emphasis in patient education and the training of more specialist allergy allied health professionals for patient support in the East. From a public health standpoint, this study serves to provide epidemiological data and analysis for future studies on the socio-economic impact of food allergy awareness. In HK, food regulations require manufactures to label all prepackaged foods containing wheat. Laws to protect patients dining at restaurants are currently not in place. In the UK, although allergen labelling is not required in restaurants or fast food outlets, allergen information must be available on request. In the United States, 5 states passed laws to increase safety of customers with food allergies, including use of food allergy awareness posters and the presence of a certified food safety manager.

The main limitations of this study stems from its retrospective nature and limitations of medical records review. Hospitalization records and AAI prescriptions were only available for the HK cohort and comparisons could not be performed. Patient adherence is self-reported and retrospective data collection includes potential ascertainment or recall bias. Reasons for poor patient adherence were not available. The follow-up period for the 2 cohorts was not long enough to study if there were any genuine differences in disease outcomes or anaphylaxis recurrence, despite differing levels of patient adherence. Further studies are required to ascertain if these interethnic differences are due to genuine biological or environmental differences (or both); but nevertheless, highlights the urgent need for prospective, ethnic-specific investigation.

In conclusion, O5G allergy appears severely underdiagnosed in HK and makes up for around 60% of so-called “idiopathic anaphylaxis” cases. Less than a third of cases were prescribed AAI prior to the allergy consultation despite all patients having experienced recurrent anaphylactic episodes requiring multiple hospital admissions. Compared to the West, O5G allergy patients in HK had more urticaria and cardiovascular manifestations, were more likely to report NSAID as a cofactor and were less concordant with wheat avoidance. These differences are likely a combination of biological and environmental differences, as well as disparities in access to healthcare. Nonetheless, this calls for urgent population-specific interventions that focus on healthcare education and interventions in Eastern countries.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors have no financial conflicts of interest.

- Conceptualization: Philip Hei Li, Iason Thomas.

- Data curation: Philip Hei Li, Iason Thomas, Jane Chi-Yan Wong.

- Formal analysis: Philip Hei Li, Iason Thomas, Jane Chi-Yan Wong.

- Methodology: Philip Hei Li, Iason Thomas.

- Project administration: Philip Hei Li, Krzysztof Rutkowski, Chak-Sing Lau.

- Visualization: Philip Hei Li.

- Writing - original draft: Philip Hei Li, Iason Thomas, Jane Chi-Yan Wong.

- Writing - review & editing: Philip Hei Li, Iason Thomas, Jane Chi-Yan Wong, Krzysztof Rutkowski, Chak-Sing Lau.

References

- 1.Morita E, Kunie K, Matsuo H. Food-dependent exercise-induced anaphylaxis. J Dermatol Sci. 2007;47:109–117. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2007.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kennard L, Thomas I, Rutkowski K, Azzu V, Yong PFK, Kasternow B, Hunter H, Cabdi NMO, Nakonechna A, Wagner A. A multicenter evaluation of diagnosis and management of omega-5 gliadin allergy (also known as wheat-dependent exercise-induced anaphylaxis) in 132 adults. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2018;6:1892–1897. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2018.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Scherf KA, Brockow K, Biedermann T, Koehler P, Wieser H. Wheat-dependent exercise-induced anaphylaxis. Clin Exp Allergy. 2016;46:10–20. doi: 10.1111/cea.12640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee TH, Leung TF, Wong G, Ho M, Duque JR, Li PH, Lau CS, Lam WF, Wu A, Chan E, Lai C, Lau YL. The unmet provision of allergy services in Hong Kong impairs capability for allergy prevention-implications for the Asia Pacific region. Asian Pac J Allergy Immunol. 2019;37:1–8. doi: 10.12932/AP-250817-0150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kushimoto H, Aoki T. Masked type I wheat allergy. Relation to exercise-induced anaphylaxis. Arch Dermatol. 1985;121:355–360. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li PH, Lau CS. Immunology in food allergy and anaphylaxis. Hong Kong Bull Rheum Dis. 2017;17:26. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee AJ, Thalayasingam M, Lee BW. Food allergy in Asia: how does it compare? Asia Pac Allergy. 2013;3:3–14. doi: 10.5415/apallergy.2013.3.1.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hospital Authority. Hospital Authority annual report 2017-2018 [Internet] Hong Kong: Hospital Authority; 2018. [cited 2019 Dec 9]. Available from: http://www.ha.org.hk/ho/corpcomm/AR201718/PDF/HA_Annual_Report_2017-2018.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Muraro A, Roberts G, Worm M, Bilò MB, Brockow K, Fernández Rivas M, Santos AF, Zolkipli ZQ, Bellou A, Beyer K, Bindslev-Jensen C, Cardona V, Clark AT, Demoly P, Dubois AE, DunnGalvin A, Eigenmann P, Halken S, Harada L, Lack G, Jutel M, Niggemann B, Ruëff F, Timmermans F, Vlieg-Boerstra BJ, Werfel T, Dhami S, Panesar S, Akdis CA, Sheikh A EAACI Food Allergy and Anaphylaxis Guidelines Group. Anaphylaxis: guidelines from the European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. Allergy. 2014;69:1026–1045. doi: 10.1111/all.12437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Le TA, Al Kindi M, Tan JA, Smith A, Heddle RJ, Kette FE, Hissaria P, Smith WB. The clinical spectrum of omega-5-gliadin allergy. Intern Med J. 2016;46:710–716. doi: 10.1111/imj.13091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wölbing F, Fischer J, Köberle M, Kaesler S, Biedermann T. About the role and underlying mechanisms of cofactors in anaphylaxis. Allergy. 2013;68:1085–1092. doi: 10.1111/all.12193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Matsuo H, Morimoto K, Akaki T, Kaneko S, Kusatake K, Kuroda T, Niihara H, Hide M, Morita E. Exercise and aspirin increase levels of circulating gliadin peptides in patients with wheat-dependent exercise-induced anaphylaxis. Clin Exp Allergy. 2005;35:461–466. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2005.02213.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Christensen MJ, Eller E, Mortz CG, Brockow K, Bindslev-Jensen C. Wheat-dependent cofactor-augmented anaphylaxis: a prospective study of exercise, aspirin, and alcohol efficacy as cofactors. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2019;7:114–121. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2018.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huang WY, Saver JL, Wu YL, Lin CJ, Lee M, Ovbiagele B. Frequency of intracranial hemorrhage with low-dose aspirin in individuals without symptomatic cardiovascular disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Neurol. 2019 doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2019.1120. May 13 [Epub] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee CP. Health care system and pharmacy practice in Hong Kong. Can J Hosp Pharm. 2018;71:140–148. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Christensen MJ, Eller E, Mortz CG, Brockow K, Bindslev-Jensen C. Exercise lowers threshold and increases severity, but wheat-dependent, exercise-induced anaphylaxis can be elicited at rest. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2018;6:514–520. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2017.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]