Highlights

-

•

ALERT-B provides an effective screening tool for gastroenterological late effects.

-

•

84.4% and 95.7% of patients demonstrated complications at 6 and 12 months post-treatment.

-

•

ROC curves at baseline indicated an AUC of 0.867 compared to the GSRS diarrhoea subscale.

-

•

ROC curves at baseline indicated an AUC of 0.765 compared to the EPIC bowel subscale.

Keywords: Prostate cancer, Radiotherapy, Gastroenterological late effects, ROC analysis

Abstract

There is an increasing need to measure treatment-related side effects in normal tissues following cancer therapy. The ALERT-B (Assessment of Late Effects of RadioTherapy - Bowel) questionnaire is a screening tool that is composed of four items related specifically to bowel symptoms. Those patients that respond with a “yes” to any of these items are referred on to gastroenterologist in order to improve the long-term consequences of these side effects of radiological treatment. Here we wish to test the ability of this questionnaire to identify these subsequent gastroenterological complications by tracking prostate cancer patients that were positive with respect to ALERT-B. We also carry out receiver-operator curve (ROC) analysis for baseline data for an overall ALERT-B questionnaire score with respect to subscale data for the Gastrointestinal Symptom Rating Scale (GSRS) and the Expanded Prostate Cancer Index Composite (EPIC-26) questionnaire. 84.4% and 95.7% of patients identified by the ALERT-B questionnaire demonstrated complications diagnosed at 6 and 12 months post-treatment, respectively. ROC curve analysis of baseline data showed that ALERT-B detected clinically relevant levels of side effects established at baseline by the GSRS diarrhoea subscale (AUC = 0.867, 95% CI = 0.795 to 0.926) and at the minimally important level of side effects for the EPIC bowel subscale (AUC = 0.765, 95% CI = 0.617 to 0.913). These results show that ALERT-B provides a simple and effective screening tool for identifying gastroenterological complications after treatment for prostate cancer.

1. Introduction

Prostate cancer is the one of the most common cancers in men in the UK. There were 47,151 new cases of prostate cancer identified in the UK in 2015 [1] and 11,631 deaths attributed to the disease in 2016 [1]. Almost 95% of men diagnosed with prostate cancer in England and Wales survive for one year or more and 84% survive ten years or more [1]. Much evidence exists that relates to both the short- and long-term effects of standard therapies such as prostatectomy and radiotherapy [2]. Radiotherapy for men with prostate cancer is administered via external beam radiotherapy (EBRT), low-dose-rate (LDR) brachytherapy or high-dose-rate (HDR) brachytherapy [3]. These treatments can be administered singly or together, perhaps also with hormone therapy or surgery. 17,000 cancer patients in the UK were estimated to receive pelvic radiotherapy each year [4]. The measurement (and reporting) of treatment-related side effects in normal tissues following cancer therapy is an important topic generally [5], [6], [7], [8]. Specifically relating to prostate cancer, it has been reported that 90% of patients [9], [10] develop a permanent change in their bowel habit and 50% experience reduced quality of life [9], [10], [11], and furthermore 20% to 40% of these patients rate the effect on quality of life as moderate or severe [12]. Although caution needs to be used in terms of generalizability, this also indicates that such side effects can be both common and severe in some patient groups.

Despite the significant impact that these bowel habit changes can have on quality of life, only one in five patients who develop gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms after pelvic radiotherapy are referred to a gastroenterologist [12]. A discussion of the possible reasons for this is given in a protocol paper for the EAGLE study [13], which aims to implement an innovative service to improve the care offered to men diagnosed with prostate cancer. The Optimising Radiotherapy Bowel Injury Therapy (ORBIT) trial [14] demonstrated that these symptoms can be diagnosed accurately and that they can be treated effectively at very modest cost compared to the cost of the cancer treatment itself, and that this approach leads to improvements in pelvic radiation-induced GI symptoms as measured by Inflammatory Bowel Disease Questionnaire-Bowel (IBDQ-B) scores. The ORBIT trial showed that patients who were offered targeted interventions from clinicians who followed a detailed algorithm had better improvements in GI symptoms when compared to patients who were given usual care [14], thus indicating the potential benefits to both patients and clinicians. The EAGLE study uses the ALERT-B (Assessment of Late Effects of RadioTherapy - Bowel) questionnaire [15], [16], which is composed of four items that require a “no” or “yes” response, namely: 1) get up at night to poo; 2) accidents, such as soiling or wet wind; 3) blood from your bottom; and, 4) bowel or tummy problems affecting your daily life. The questionnaire is presented in Appendix A. Patients who reply “yes” to any of the questions are then referred on to a gastroenterologist. A literature review and expert consensus meeting [15] identified these four items for ALERT-B. ALERT-B was face tested for its usability and acceptability using cognitive interviews with 12 patients experiencing late gastrointestinal symptoms after pelvic radiotherapy in order to identify potential problems with the ALERT-B screening tool before its use in larger studies or in clinical practice. Cronbach’s α was found [15] to be 0.61 for ALERT-B. This is slightly lower than the generally accepted cut-off for ‘adequate’ given by a value of a 0.7. (Cronbach’s α is strongly affected by the number of items included in the calculation, with higher numbers of items tending to increase the value of α). Furthermore, item-scale correlations were high, r > 0.6, which indicated again that ALERT-B is internally consistent. Note that exploratory factor analysis was also carried out successfully [15]. In summary, these results indicated moderate to good levels of internal reliability for the ALERT-B screening tool.

A 2013 systematic review [16] details results for 29 different questionnaires that measure (self-reported) symptoms in localized prostate cancer. “Psychometric” analyses such as Cronbach’s α and exploratory factor analysis (etc.) were seen to be common methods of validation in this review [16], although the authors found that only seven such questionnaires were acceptable in terms of “broad domain coverage, ability to differentiate objective and subjective experience, good internal consistency and validation in at least two populations and/or having achieved two types of validations.” Furthermore, it was noticeable that only two studies in this review [17], [18] examined measures for their sensitivity (proportion of patients that truly are positive and that are classified as correctly as positive), specificity (proportion of patients that truly are negative and that are classified as correctly as negative), positive predictive value (PPV; proportion of positive predictions that are correct), and/or negative predictive value (NPV; proportion of negative predictions that are correct). Despite this general lack of evidence, such information is extremely important in terms of the clinical validation of these questionnaires. Here we present results for clinical diagnoses at 6 and 12 months for those patients that were initially tested as positive via the ALERT-B questionnaire at baseline. We also carry out receiver operator characteristic (ROC) curve analysis on baseline data for the ALERT-B questionnaire by using the Gastrointestinal Symptom Rating Scale (GSRS) questionnaire [19] subscale data and (separately) the (EPIC) questionnaire (also collected at baseline) as proxies for “ground truth” data. GSRS is a validated questionnaire for patients with general gastrointestinal complaints [19], [20], [21], [22]. Cronbach’s α for the GSRS questionnaire ranges from 0.60 to 0.85 in patients with duodenal ulcer and from 0.61 to 0.83 in patients with gastro-oesophageal reflux disease [19], [20], [21]. The GSRS has been used in many areas of gastrointestinal research [19], [20], [21], [22], [23], [24], [25] and it been used to assess cancer patients with both gastrointestinal and extra-gastrointestinal cancers [26], [27], [28]. The GSRS measures 15 gastrointestinal symptoms using a four-point scale. It assesses five subscales: reflux syndrome (heartburn and acid regurgitation); acute pain syndrome (abdominal pain, hunger pains and nausea); indigestion syndrome (borborygmi, abdominal distension, eructation and increased flatus); diarrhoea syndrome (diarrhoea, loose stools and urgent need to defecate); constipation syndrome (constipation, hard stools and feeling of incomplete evacuation). A subscale score of zero indicates the symptom is absent, whereas a score of three [23] indicates that the patient experiences great social and activity-related impairment as a result of negative physiologic symptoms. The original 50-item EPIC questionnaire covered urinary incontinence, irritation/obstruction items, bowel, sexual and hormonal domains, each with function and bother subscales [29]. A shorter 26 item version of EPIC was designed and validated [30]. EPIC-26 has shown satisfactory test-retest reliability and internal consistency for the urinary, bowel, sexual, and hormonal subscales [30]. All EPIC subscale scores are transferred linearly onto a 0–100 scale as per the EPIC scoring manual [31], where a higher score indicates better function or reduced “bother”. Our aim is to show that the ALERT-B provides a simple and effective method of detecting gastroenterological late effects after radiotherapy for prostate cancer.

2. Materials and methods

Ethical approval for this study was given by the North Wales Research Ethics Committee (REC) (Central & East) Proportionate Review Sub-Committee (reference 13/WA/0243) and the study was sponsored by Cardiff University (SPON1238-14). Patients were recruited from three centres in the United Kingdom, namely, Cardiff (Clinical Nurse Specialist (CNS) led), Sheffield (physician led), and Brighton (CNS led). Initially, those patients who attended urology/oncology follow-up clinics after receiving radiotherapy treatment for prostate cancer generally within 3 months previously (see Table 1) were asked to consent to the registration phase by a trained health care professional working at the oncology clinic. Those patients who consented then completed the ALERT-B tool, thus also establishing a baseline for the study. Patients were excluded thereafter if they met one or more of the following criteria: any factor that affects their ability to communicate their wishes; an inability to comprehend what is being asked of them; a lack of capacity to consent; or, cancer recurrence. Definitive diagnoses by the clinical management team were found at 6 months and 12 months only for patients that were “positive” according to ALERT-B at baseline, and so we can find a form of PPV only. (Caution should be exercised here though due to missing data at 6 and 12 months). The GSRS and ALERT-B questionnaires were completed by patients at baseline and subscale scores for the GSRS were found as per the GSRS scoring manual. In order to obtain measures of sensitivity and specificity, we use subscales for the GSRS questionnaire as proxies for the “ground truth” at baseline. An overall ALERT-B score was found for each patient by adding together the scores for the 4 individual items (where 0 = no and 1 = yes). Cut-offs for the GSRS subscale scores (in the range 1 to 7) of any value greater than 1 (i.e., any complications/symptoms at all no matter how small) and separately any score greater than or equal to 3 (i.e., a “clinically important” level [23]) again in order to provide proxies for “ground truth” positives or negatives for all subscales (pain, reflux, diarrhoea, indigestion, constipation) independently. The cut-off for the minimally important difference for the EPIC questionnaire subscale data is given by 5% [32], [33], and so the minimum level of clinically important effects is taken to be 95 for the EPIC subscales. ROC curves were then found for the ALERT-B data against these proxies. All statistical calculations were carried out using SPSS V23. (More details relating to “materials and methods” for this study have previously been published [13]).

Table 1.

Patient and treatment characteristics at baseline. (Age was collected for 236 subjects and all other fields for those subjects that scored positive via ALERT-B. Note also that there was some missing data).

| Age (years) | Mean | Standard deviation | Median | |

| 72.9 | 6.6 | 68.3 | ||

| Time to baseline from radiotherapy | n | Percentage (%) | ||

| 0 to 3 months | 50 | 87.7 | ||

| 3 to 9 months | 3 | 5.3 | ||

| 9 to 15 months | 3 | 5.3 | ||

| Total | 57 | 100 | ||

| Treatment | EBRT alone | 56 | 98.3 | |

| EBRT + Brachytherapy | 1 | 1.7 | ||

| Total | 57 | 100 | ||

| Dose fractionation schedules | 2-Gy equivalent dose (α/β = 3 Gy)1 | n | Percentage (%) | |

| 46 Gy/23 fractions (with HDR boost) | 46.00 Gy | 2 | 3.5 | |

| 52.5 Gy/20 fractions | 59.06 Gy | 2 | 3.5 | |

| 55 Gy/20 fractions | 63.25 Gy | 1 | 1.8 | |

| 57 Gy/19 fractions | 68.40 Gy | 1 | 1.8 | |

| 60 Gy/60 fractions | 48.00 Gy | 1 | 1.8 | |

| 60 Gy/20 fractions | 72.00 Gy | 14 | 24.6 | |

| 70 Gy/20 fractions | 91.00 Gy | 1 | 1.8 | |

| 70 Gy/37 fractions | 68.49 Gy | 10 | 17.5 | |

| 74 Gy/37 fractions | 74.00 Gy | 23 | 40.4 | |

| 74 Gy/5 fractions | 263.44 Gy | 1 | 1.8 | |

| 74 Gy/25 fractions | 88.21 Gy | 1 | 1.8 | |

| Total | 57 | 100 | ||

| Androgen deprivation therapy | n | Percentage (%) | ||

| Yes | 39 | 68.4 | ||

| No | 18 | 31.6 | ||

| Total | 57 | 100 | ||

| Staging | T1 | 6 | 11.1 | |

| T2 | 27 | 50.0 | ||

| T3 | 21 | 38.9 | ||

| Total | 54 | 100 | ||

| Gleason Grade | 1 | 1 | 1.9 | |

| 2 | 36 | 66.7 | ||

| 3 | 15 | 27.8 | ||

| 4 or 5 | 2 | 3.7 | ||

| Total | 54 | 100 | ||

Dose per fraction (DPF) = total dose/number of fractions; effective dose = total dose × {1 + DPF/(α/β)} = total dose × {1 + DPF/3}; equivalent dose = effective dose/{1 + 2/(α/β)} = 3 × effective dose/5.

3. Results

339 patients were screened initially, and 91 answered “yes” to any of the four items in the ALERT-B questionnaire. Of these 339 patients, 314 also completed the GSRS questionnaire at baseline. The median age at screening was 68.3 years (approximate range: 53 to >86). These patients were referred to a gastroenterologist, of whom 58 patients accepted this referral. Patient and treatment characteristics at baseline are shown in Table 1. 56% of these patients at baseline were recruited in Cardiff, 39% in Sheffield, and 5% in Brighton. As part of the EAGLE study, 58 patients were included overall at baseline, 36 patients at 6 months (±2 months), and 23 patients at 12 months (±2 months). Of these 58 patients at baseline, 56 returned EPIC questionnaire data. The large amounts of missing data at 6 and 12 months compared to baseline precluded the use of imputation methods. (Note that the main results of the EAGLE study are not presented here as we wish to focus purely on the ability of the ALERT-B screening tool to detect gastroenterological side effects).

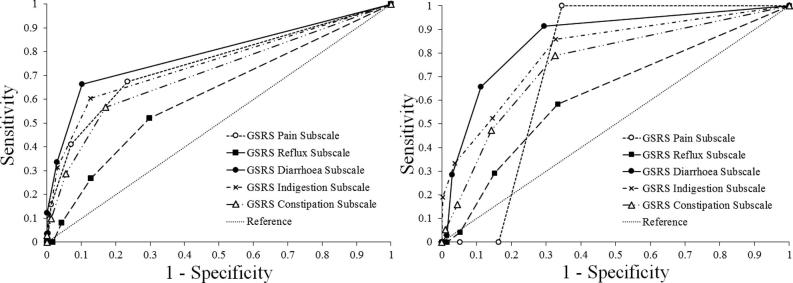

Specific diagnoses collected from 33 patients at 6 months and 23 patients at 12 months and the results are shown in Table 2. (Note that 3 out of the 36 patients at 6 months did not receive diagnosis at this time point). At 6 months, 5 patients (15%) were diagnosed as having no complications, 19 patients (58%) as a single complication, and 9 (27%) as two complications. At 12 months, 1 patient (4%) was diagnosed as having no complications, 6 patients (26%) as a single complication, and 8 (35%) as two complications, 6 (26%) as three complications, and 2 (9%) as four complications. The number of complications rose from a mean of 1.12 per person and a median of 1 per person at 6 months to a mean of 2.09 per person and a median of 2 per person at 12 months, which constitutes a significant increase in the number of complications (Wilcoxon signed-rank test: z = 3.345, P(2-tailed) < 0.001). However, some caution should be exercised here due to missing data. One of the 33 patients at 6 months responded “no” to all ALERT-B items at baseline, although this patient did also demonstrate some symptoms at this point and so they were referred on to the gastroenterology team. Hence, proportions for specific diagnoses are shown in Table 3 for 32 patients at 6 months and all 23 patients at 12 months that received a positive score from the ALERT-B questionnaire (i.e., at least one “yes”). Radiation proctopathy and “diagnoses of special interest” increased from 6 to 12 months, although these increases were not significant (P > 0.05). There was a significant increase (P = 0.016) in radiation proctopathy and a diagnosis of at least one other complication or symptom going from 6 months to 12 months. Finally, results for the proportion relating to “at least one complication” (arguably a form of PPV) increased from 84.4% at 6 months to 95.7% at 12 months, although this was not significant (P > 0.05). 339 patients completed the ALERT-B questionnaire at baseline and 315 patients also returned GSRS data at this point. ROC curves for this data are presented in Fig. 1. These results suggest that the ALERT-B questionnaire performs better for higher cut-off (GSRS subscale score ≥ 3) rather than the lower cut-off than compared (GSRS subscale score > 1). Indeed, ALERT-B would be expected to capture higher levels of complications compared to any symptoms at all (no matter how small). The highest areas under the curve (AUC) and associated 95% confidence intervals for the AUC were for the GSRS diarrhoea subscale. This reflects the focus of the ALERT-B tool, which addresses bowel symptoms only. Note that AUC = 0.79 (95% CI = 0.738 to 0.843) for diarrhoea subscale scores > 1 and AUC = 0.867 (95% CI = 0.795 to 0.926) for diarrhoea subscale scores ≥ 3. These results for the bowel subscale are significantly different to the “reference” line (i.e., the 95% CI does not include the critical value of AUC = 0.5). The highest AUC for ALERT-B compared to EPIC questionnaire data was for the bowel subscale. As expected, all of the other subscales (urinary incontinence, urinary irritation/obstruction, sexual, and hormonal) had lower values for the AUCs, which were not significantly different to the critical value of AUC = 0.5. Note also that these calculations were hampered by a very small sample size (n = 56) which strongly affects the reliability of the results for these ROC curves, and so these results are not presented here for these specific EPIC subscales. Despite this limitation however, an of AUC = 0.765 (95% CI = 0.617 to 0.913) was obtained for a cut-off of less than or equal to 95 (i.e., the minimum level of clinically important effects [32], [33]) for the EPIC bowel subscale score, which is another encouraging result.

Table 2.

Number and percentages of specific diagnoses collected from 33 patients at 6 months and 23 patients at 12 months.

| Diagnosis | 6 months |

12 months |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Percentage (%) | n | Percentage (%) | |

| Diverticular disease | 9 | 27 | 4 | 17 |

| Pelvic floor/sphincter weakness | 0 | 0 | 6 | 26 |

| Colonic adenoma | 6 | 18 | 5 | 22 |

| Lactose/fructose intolerance | 0 | 0 | 4 (2/2) | 17 |

| Bile salt malabsorption | 4 | 12 | 4 | 17 |

| Dietary issues | 3 | 9 | 4 | 17 |

| Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth | 2 | 6 | 3 | 13 |

| “Other” such as vitamin B12 deficiencies, alcohol excess etc. | 5 | 15 | 6 | 26 |

Table 3.

Number (percentages in brackets) of patients with specific diagnoses from 32 patients at 6 months and 23 patients at 12 months that received a positive score from the ALERT-B questionnaire “diagnoses of special interest” = a diagnosis of any of the following: bile salt malabsorption, small intestinal bacterial overgrowth, lactose intolerance, vitamin b12 insufficiency, floor/sphincter.

| At least one complication (P = 0.5) | Radiation proctopathy (P = 0.125) | Radiation proctopathy & at least one other (P = 0.016) | “Diagnoses of special interest” (P = 0.063) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6 months | 27 (84.4%) | 8 (25.0%) | 4 (12.5%) | 7 (21.9%) |

| 12 months | 22 (95.7%) | 12 (52.2%) | 11 (47.8%) | 12 (52.2%) |

Fig. 1.

Receiver operator characteristic (ROC) curve using GSRS as a proxy for ground-truth. (Left) ground truth for GSRS subscale scores > 1. (Right) ground truth for GSRS subscale scores ≥ 3.

4. Discussion

Patient-reported outcome measures of the side effects of cancer treatment are routinely tested psychometrically by standard methods such as Cronbach’s alpha and exploratory factor analysis. Rather less attention has been given to measures of clinical validity based on some “ground truth” that has been established, e.g., by clinical diagnosis. In this instance, 84.4% and 95.7% of those patients identified as a “positive” by ALERT-B subsequently went on to demonstrate clinically diagnosed complications at 6 and 12 months post-treatment, respectively. However, caution must be exercised in interpreting these results as a PPV owing to the amount of missing data (43% at 6 months and 60% at 12 months), which can bias estimates. Nevertheless, it is important to note that all of the patients identified by ALERT-B are those we would expect to have gained clinical benefit from the systematic screening for symptoms. Furthermore, 25% of patients retained at 6 months and 52% of patients at 12 months identified by ALERT-B had a diagnosis of radiation proctopathy; these could have been diagnosed with direct referral for flexible sigmoidoscopy. 12.5% of patients retained at 6 months and 47.8% of patients at 12 months identified by ALERT-B were diagnosed with radiation proctopathy and at least one other complication or symptom; these patients would be expected to gain a clinical benefit from systematic algorithmic management (with subsequent assessment and systematic investigation thereafter) and not “just” direct referral for flexible sigmoidoscopy. Finally, ROC curve analysis suggested that ALERT-B at baseline performed well in comparison to a “ground truth” based on baseline subscale scores for the GSRS diarrhoea and EPIC bowel subscales (especially) at clinically relevant levels. For GSRS diarrhoea subscale scores (≥3), the AUC was 0.867 (95% CI = 0.795 to 0.926). For EPIC bowel subscale scores (≤95), the AUC was AUC = 0.765 (95% CI = 0.617 to 0.913).

5. Conclusion

The ALERT-B questionnaire provides a simple and effective screening tool for detecting gastroenterological late effects after radiotherapy for prostate cancer. ALERT-B is an integral part of the EAGLE study, which aims to implement an innovative service to improve the care offered to men diagnosed with prostate cancer. Specifically, patients identified by ALERT-B will be offered targeted interventions from clinicians via a detailed algorithm, which will lead to improvements in gastrointestinal symptoms.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

The work represented in this manuscript, including the posts of AN and SS was supported by core funding from Marie Curie to the Marie Curie Palliative Care Research Centre, Cardiff University (grant reference: MCCC-FCO-14-C). The results presented here were conducted as part of the EAGLE study, funded by Prostate Cancer UK’s TrueNTH initiative (Grant Reference 250-55).

Appendix A

Fig. A1.

The ALERT-B questionnaire.

References

- 1.Cancer Research UK, Prostate Cancer Statistics, http://www.cancerresearchuk.org/healthprofessional/prostate-cancer-statistics [Accessed: April 2019].

- 2.Peschel R.E., Colberg J.W. Surgery, brachytherapy, and external-beam radiotherapy for early prostate cancer. Lancet Oncol. 2003;4(4) doi: 10.1016/s1470-2045(03)01035-0. 233–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Garnick M.B. Prostate cancer: screening, diagnosis, and management. Ann Intern Med. 1993;118(10):804–818. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-118-10-199305150-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Henson C.C., Andreyev H.J., Symonds R.P., Peel D., Swindell R., Davidson S.E. Late onset bowel dysfunction after pelvic radiotherapy: a National survey of current practice and opinions of clinical oncologists. Clin Oncol. 2011;23(8):552–557. doi: 10.1016/j.clon.2011.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dishe S., Warburton M.F., Jones D., Lartigau E. The recording of morbidity related to radiotherapy. Radiother Oncol. 1989;16:103–108. doi: 10.1016/0167-8140(89)90026-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bentzen S.M., Dörr W., Anscher M.S., Denham J.W., Hauer-Jensen M., Marks L.B. Normal tissue effects: reporting and analysis. Sem Radiat Oncol. 2003;13:189–202. doi: 10.1016/S1053-4296(03)00036-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Trotti A., Bentzen S.M. The need for adverse effects reporting standards in oncology clinical trials. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:19–22. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.10.911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Farnell D.J.J., Mandall P., Anandadas C., Routledge J., Burns M.P., Logue J.P. Development of a patient-reported questionnaire for collecting toxicity data following prostate brachytherapy. Radiother Oncol. 2010;97(1):136–142. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2010.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Olopade F., Blake P., Dearnaley D., Khoo V., Tait D., Norman A. The inflammatory bowel disease questionnaire and the Vaizey incontinence questionnaire are useful to identify gastrointestinal toxicity after pelvic radiotherapy. Br J Cancer. 2005;92:1663–1670. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Andreyev J. Gastrointestinal symptoms after pelvic radiotherapy: a new understanding to improve management of symptomatic patients. Lancet Oncol. 2007;8:1007–1017. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(07)70341-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gami B., Harrington K., Blake P., Dearnaley D., Tait D., Davies J. How patients manage gastrointestinal symptoms after pelvic radiotherapy. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;18:987–994. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2003.01760.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Andreyev H.J.N., Benton B.E., Lalji A., Norton C., Mohammed K., Gage H. Algorithm-based management of patients with gastrointestinal symptoms in patients after pelvic radiation treatment (ORBIT): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2014;382(9910):2084–2092. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61648-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Taylor S., Demeyin W., Muls A., Ferguson C., Farnell D.J.J., Cohen D., Andreyev J., Green J., Smith L., Ahmedzai S., Pickett S., Nelson A., Staffurth J. Improving the Wellbeing of Men by Evaluating and Addressing the Gastrointestinal Late Effects of Radical Treatment for Prostate Cancer (EAGLE): study protocol for a mixed-method implementation project. BMJ Open. 2016;6 doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Andreyev H.J., Benton B.E., Lalji A., Norton C., Mohammed K., Gage H. Algorithm-based management of patients with gastrointestinal symptoms in patients after pelvic radiation treatment (ORBIT): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2014;382:2084–2092. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61648-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Taylor S., Demeyin W., Muls A., Ferguson C., Farnell D.J.J., Cohen D. The three item ALERT-B questionnaire provides a validated screening questionnaire to detect chronic gastrointestinal symptoms after pelvic radiotherapy in cancer survivors. Clin Oncol. 2016;28(10):e139–e147. doi: 10.1016/j.clon.2016.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rnic K., Linden W., Tudor I., Pullmer R., Vodermaier A. Measuring symptoms in localized prostate cancer: a systematic review of assessment questionnaires. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2013;16:111–122. doi: 10.1038/pcan.2013.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Justice A.C., Rabeneck L., Hays R.D., Wu A.W., Bozzette S.A. Sensitivity, specificity, reliability, and clinical validity of provider-reported symptoms: a comparison with self-reported symptoms. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 1999;21:126–133. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hosseini M., Ebrahimi S.M., Alinaghi S.A.S., Mahmoodi M. Sensitivity and specificity of International Prostate Symptom Score (IPSS) for the screening of Iranian patients with prostate cancer. Acta Med Iran. 2010;49:451–455. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Svedlund J., Sjödin I., Dotevall G. GSRS–a clinical rating scale for gastrointestinal symptoms in patients with irritable bowel syndrome and peptic ulcer disease. Dig Dis Sci. 1988;33(2):129–134. doi: 10.1007/BF01535722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Revicki D.A., Wood M., Wiklund I., Crawley J. Reliability and validity of the gastrointestinal symptom rating scale in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease. Qual Life Res. 1997;7(1):75–83. doi: 10.1023/a:1008841022998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kulich K.R., Madisch A., Pacini F., Piqué J.M., Regula J., Van Rensburg C.J. Reliability and validity of the gastrointestinal symptom rating scale (GSRS) and quality of life in reflux and dyspepsia (QOLRAD) questionnaire in dyspepsia: a six-country study. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2008;6:12. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-6-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dimenäs E., Glise H., Hallerbäck B., Hernqvist H., Svedlund J., Wiklund I. Well-being and gastrointestinal symptoms among patients referred to endoscopy owing to suspected duodenal ulcer. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1995;30(11):1046–1052. doi: 10.3109/00365529509101605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wiklund I., Carlsson J., Vakil N. Gastroesophageal reflux symptoms and well-being in a random sample of the general population of a Swedish community. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101(1):18–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.00343.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Iwarzon M., Gardulf A., Lindberg G. Functional status, health-related quality of life and symptom severity in patients with chronic intestinal pseudo-obstruction and enteric dysmotility. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2009;44(6):700–707. doi: 10.1080/00365520902840806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lohiniemi S., Mäki M., Kaukinen K., Laippala P., Collin P. Gastrointestinal symptoms rating scale in coeliac disease patients on wheat starch-based gluten-free diets. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2000;35(9):947–949. doi: 10.1080/003655200750023002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liedman B., Svedlund J., Sullivan M., Larsson L., Lundell L. Symptom control may improve food intake, body composition, and aspects of quality of life after gastrectomy in cancer patients. Dig Dis Sci. 2001;46(12):2673–2680. doi: 10.1023/a:1012719211349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Namikawa T., Kitagawa H., Okabayashi T., Sugimoto T., Kobayashi M., Hanazaki K. Double tract reconstruction after distal gastrectomy for gastric cancer is effective in reducing reflux esophagitis and remnant gastritis with duodenal passage preservation. Langenbeck’s Arch Surgery. 2011;396(6):769–776. doi: 10.1007/s00423-011-0777-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Russo F., Linsalata M., Clemente C., D’Attoma B., Orlando A., Campanella G. The effects of fluorouracil, epirubicin, and cyclophosphamide (FEC60) on the intestinal barrier function and gut peptides in breast cancer patients: an observational study. BMC Cancer. 2013;13(1):56. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-13-56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Szymanski K.M., Wei J.T., Dunn R.L., Sanda M.G. Development and validation of an abbreviated version of the expanded prostate cancer index composite instrument for measuring health-related quality of life among prostate cancer survivors. Urology. 2010;76(5):1245–1250. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2010.01.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wei J.T., Dunn R.L., Litwin M.S., Sandler H.M., Sanda M.G. Development and validation of the expanded prostate cancer index composite (EPIC) for comprehensive assessment of health-related quality of life in men with prostate cancer. Urology. 2000;56(6):899–905. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(00)00858-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sanda M, Wei J, Litwin M. Scoring Instructions for the Expanded Prostate cancer Index Composite Short Form (EPIC-26). Available from: https://medicine.umich.edu/dept/urology/research/epic accessed to 7th Feb. 2020.

- 32.Pinkawa M., Holy R., Piroth M.D., Klotz J., Pfister D., Heidenreich A. Interpreting the clinical significance of quality of life score changes after radiotherapy for localized prostate cancer. Curr Urol. 2011;5(3):137–144. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Skolarus T.A., Dunn R.L., Sanda M.G., Chang P., Greenfield T.K., Litwin M.S. Minimally important difference for the expanded prostate cancer index composite short form. Urology. 2015;85(1):101–106. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2014.08.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]