Abstract

The systematic review presented in this article aims to reveal what supports and hampers refugee children in telling their, often traumatic, life stories. This is important to ensure that migration decisions are based on reliable information about the children’s needs for protection. A systematic review was conducted in academic journals, collecting all available scientific knowledge about the disclosure of life stories by refugee minors in the context of social work, guardianship, foster care, asylum procedures, mental health assessment, and therapeutic settings. The resulting 39 studies were thoroughly reviewed with reference to what factors aided or hampered the refugee children’s disclosure of their life stories. The main barriers to disclosure were feelings of mistrust and self-protection from the side of the child and disrespect from the side of the host community. The facilitators for disclosing life stories were a positive and respectful attitude of the interviewer, taking time to build trust, using nonverbal methods, providing agency to the children, and involving trained interpreters. Social workers, mentors, and guardians should have time to build trust and to help a young refugee in revealing the life story before the minor is heard by the migration authorities. The lack of knowledge on how refugee children can be helped to disclose their experiences is a great concern because the decision in the migration procedure is based on the story the child is able to disclose.

Keywords: community violence, cultural contexts, memory and trauma, war, mental health and violence

Introduction

Being able to share important details of aversive experiences might be a matter of life and death for refugee children. After having fled from the home country, they request protection in a new, host country. If those children are not able to explain why the authorities should provide protection, they risk being deported without a proper assessment of the threats they might encounter upon return (Arnold, 2018, p. 174).

The migration authorities, on the other side, have the obligation to assess the best interests of the child and to make sure that these interests are a primary consideration in the decision-making process (Kalverboer, Beltman, van Os, & Zijlstra, 2017). Assessing the best interests of the child is not possible without hearing the child in an adequate manner (United Nations Committee on the Rights of the Child, 2013, para. 43, 53–54). Therefore, for the migration authorities, knowledge on how to support refugee children in disclosing relevant elements of their life story is crucial. Moreover, professionals who work with refugee children in foster families, at reception centers, or in care institutions could benefit from a better understanding on how they could comfort the child in their professional talks about the children’s previous life experiences. Providing knowledge on what helps and hampers refugee children in telling their life stories is the aim of the systematic review presented in this article.

This study focuses on unaccompanied children as well as on children accompanied by their parents or caregivers who are forced to leave their home country and seek protection in another country. In most cases, these children ask for asylum and therefore can be defined as asylum-seeking children in the legal sense. Legally, these children are called “refugees” once their asylum claim has been accepted. We use the term “refugee children” for children who seek protection in another country, whether on the grounds of being a refugee in the sense of the 1951 Refugee Convention or other forms of perceived danger in the home country (United Nations [UN], 1951; United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees [UNHCR], 1994). In line with the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC), we mean by children: people under the age of 18 (CRC, art. 1).

The Refugee Convention (UN, 1951) entitles persons who have a well-founded fear for persecution for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group, or political opinion to protection in the country where the asylum request has been lodged (art. 1A). In most countries, for example, in the European Union states, grounds for subsidiary protection on humanitarian grounds are also provided in the national migration law (Gornik, Sedmak, & Sauer, 2017, pp. 6–7). Those rules for refugee determination do not have any special guarantees for children. However, the UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR, 2009, para. 1, 5) highlights the importance to assess refugee children’s need for protection in a child-sensitive manner and by taken their best interests as a primary consideration. Migration authorities have to take into account that “children may not be able to articulate their claims to refugee status in the same way as adults and, therefore, may require special assistance to do so” (UNHCR, 2009, para. 2, 72).

The right to express his or her views on the refugee claim counts for unaccompanied as well as for accompanied children (UNHCR, 2009, para. 8, 70; CRC, art. 12). However, children in families are generally not heard about their own asylum motives (Drywood, 2010; Lidén & Rusten, 2007). For example, in the Netherlands, accompanied children from the age of 15 are interviewed on their asylum request, while unaccompanied children from the age of 6 are heard. In the Netherlands, the refugee child gets first an interview about the details of the journey and identity. This interview may take nearly a whole day. The same counts for the second interview about the asylum motives (van Os, Zijlstra, Knorth, Post, & Kalverboer, 2017). In some other countries, for example, in Austria, Italy, Sweden, and the United Kingdom, this division between initial, screening hearings, and substantial hearing is also made (UNHCR, 2014, pp. 41, 43, 49; Warren & York, 2014, pp. 13–15).

The asylum hearings with children are focused on assessing the credibility of the child’s story (UNHCR, 2014, p. 146; Warren & York, 2014, pp. 25–26). However, a lot of unaccompanied refugee children face difficulties in sharing their life stories (Kohli, 2011). Experiences prior, during, and after the migration may make them hesitant to disclose the life narratives (Colucci, Minas, Szwarc, Guerra, & Paxton, 2015; Thomas, Thomas, Nafees, & Bhugra, 2004). Some children have had instructions from parents or travel agents on what their story should be, once they arrive in the host country. These instructed stories are believed to enlarge their chance of getting a residence permit (Adams, 2009; Chase, 2013; McKelvey, 1994). Kohli (2006) calls these constructed narratives “thin stories” that act as a “key to entry into the country based on its migration policies” (p. 711). Unaccompanied children also often cling to these thin stories in contact with others, like social workers, because they are identified with authorities or because the children suppose this is needed in order to receive protection (Kohli, 2006). Refugee children in Austria, for instance, reported that they felt the asylum procedure is not receptive for their multilayered stories because the immigration authorities are just interested in their thin stories (Dursun & Sauer, 2017, p. 94).

Accompanied children may face difficulties in asylum hearings because they do not know the reasons the family had to leave the country; their parents had kept these reasons secret with the intention to protect their children (Montgomery, 2004). Children who are aware of the reasons the family had to flee their home country may feel they have to show loyalty by confirming the stories of their parents in contact with the migration authorities (Björnberg, 2011; Ottosson & Lundberg, 2013).

Mental health problems may hamper the ability of both unaccompanied and accompanied children to talk about their life stories. Research on the situation of recently arrived refugee children in the host country shows that they have experienced a large number of stressful life events which put them at risk to face post-traumatic stress, depression, and anxiety disorders (van Os, Kalverboer, Zijlstra, Post, & Knorth, 2016). From literature about abused children, it is known that those who suffered from traumatic experiences often have difficulties disclosing their life stories to others (Anderson, Anderson, & Gilgun, 2014; Leander, 2010; Mordock, 2001; Saywitz, Lyon, & Goodman, 2011). Interviewers of traumatized refugee children can be confronted with the same difficulties as forensic interviewers who speak with abused children.

The effect of traumatic experiences may impede the refugee child’s ability to produce a coherent, chronological story, and this may lead to accusations of lying or at least being not credible (Crawley, 2010; UNHCR, 2014, p. 146). When refugees are traumatized, the number of discrepancies rises as interviews take longer or the time between the interviews increases (Herlihy, Scragg, & Turner, 2002; Steel, Frommer, & Silove, 2004). Although discrepancies between two accounts of the same event should not be considered an indicator for the credibility of the asylum story (Herlihy et al., 2002; Herlihy & Turner, 2006; Spinhoven, Bean, & Eurelings-Bontekoe, 2006; Steel et al., 2004), inconsistencies are an important reason for rejecting children’s asylum claims (UNHCR, 2014, pp. 146, 154).

The difficulties concerning trust and the effect of being exposed to traumatic experiences require the involvement of psychologically educated professionals when refugee children are heard about their asylum request. This is confirmed by the United Nations Committee on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC, 2013) in their guidelines for the best interests of the child determination in General Comment No. 14 (GC 14). GC 14 provides guidelines on the implementation of Article 3 of the UNCRC that stipulates the best interests of the child should be a primary consideration when decisions are taken that concern them (UN, 1989). Involved professionals should have knowledge of, inter alia, child development and child psychology (GC 14, para. 94). The committee also highlights the importance of taking into account the views of the child (GC 14, para. 53–54). Gathering the views of the refugee child means looking behind the lines of the asylum-related questions and asking children about their personal and their family’s migration motives (Vervliet, Vanobbergen, Broeckaert, & Derluyn, 2014).

To our knowledge, a systematic review on the barriers and facilitators for refugee’s children’s disclosure has not yet been done. However, the safety and future of the refugee child is highly influenced by the way the child is able to tell his or her life story (Chase, 2010; Crawley, 2010). Knowledge on how refugee children can be supported in sharing aversive experiences is necessary to ensure a best interests of the child determination in the asylum procedure, leading to migration decisions based on more valid and reliable information about the child’s need for protection. In the next sections, the method and results of a systematic review on the barriers to and facilitators for refugee children’s disclosure of their life stories will be presented.

Method

Search Strategy

The selection of search terms is based on the key words in the literature about disclosure by refugee children, the related topics on the views of the refugee child, and the problems concerning memory and credibility discussed in the Introduction section. Table 1 provides an overview of the search terms.

Table 1.

Overview of Search Terms.

| Aspects of the Research Question | Search Terms | |

|---|---|---|

| Content | Disclosure | disclosure OR silence OR silent OR *trust* OR secret* OR open OR |

| Memory | memory OR memories OR credibility OR deception OR inconsistencies OR detail* OR discrepancies OR truth OR | |

| Views of the child | motives OR ambitions OR aspirations OR dreams OR views OR ideas OR opinions OR voices OR | |

| Life stories | journey OR “life story” OR “life stories” OR “life history” OR “life event*” OR narrative*” | |

| Age | Children | AND |

| child* OR young* OR adolescen* OR kid* OR minor* OR infant* OR unaccompanied OR accompanied | ||

| Background | Refugee | AND |

| asylum* OR refugee* OR fled OR flee OR “forced migrat*” | ||

We searched the Web of Science, PsycINFO, SOCindex, ERIC, and Medline databases. Additionally, reference lists were checked in the full-text reviewing phase (Booth, Papaioannou, & Sutton, 2012, p. 78). We limited the results to articles published in academic peer-reviewed journals from January 1995 until January 2016.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Included were studies presenting research in social and behavioral sciences which provide information on how the disclosure of life stories by refugee children was impeded or supported in the context of social work, guardianship, foster care, asylum procedures, mental health assessment, and therapeutic settings, and which are written in English. When two or more studies reported about the same sample, the article that gave the most information on disclosure was included.

We included studies on refugee children, meaning children who were forced to leave their country of origin due to war or other harmful experiences. Studies were included concerning both children who have traveled alone to the host country, being unaccompanied by their parents or other care takers, and children who fled together with their parent(s), referred to as accompanied children.

Excluded were comments, interviews, and literature reviews. From the latter category, the reference lists were screened in order to find the primary resources that answered the research question; these were included.

We excluded studies when the quality of the research was considered insufficient. The quality was assessed by answering 18 appraisal questions that are based on four guiding principles: (1) the research should contribute to the wider knowledge on the topic; (2) the design should be defensible; (3) the research should be rigorous by providing transparency on data collection, analysis, and interpretation; and (4) the research should be credible by offering well-founded arguments about the significance of the results (Petticrew & Roberts, 2006, p. 152; Spencer, Ritchie, Lewis, & Dillon, 2003).

Selection Process

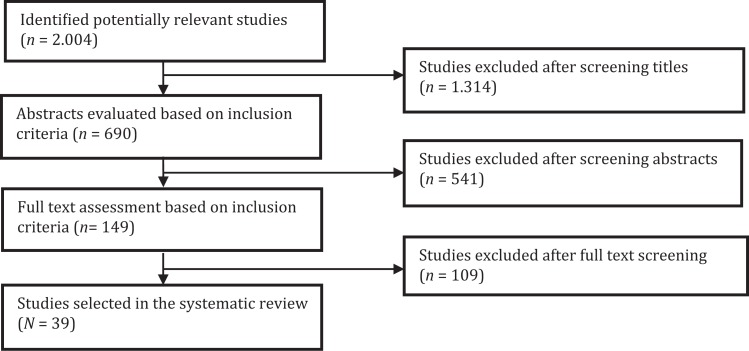

Based on the search terms, 2,535 articles in academic journals were found. Of these, 531 were duplicates, leaving 2,004 articles that were first screened by title to exclude articles that obviously did not meet the inclusion criteria (see Figure 1). The screening resulted in 1,314 excluded articles. The abstracts of the remaining 690 articles were reviewed and categorized on the basis of inclusion and exclusion criteria. After the screening of the abstracts, 541 articles were excluded. The full text of the remaining 149 articles was assessed. The excluded categories in the abstract and full-text screening phase were: does not answer the research question (n = 285); studies concerning adults (n = 210); reviews, books, and editorials (n = 94); studies concerning migrants (n = 38); and physical health studies (n = 20). In addition, three studies were excluded because these were based on the same sample as another study by the same author. One other study was excluded in the full-text phase because the quality of the research was assessed as insufficient. The excluded categories refer to the first exclusion criterion that was found although other exclusion criteria could be present too. Finally, 39 studies were selected for the systematic review.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of study selection process.

Selecting Barriers and Facilitators

The included studies were thoroughly reviewed on which factors supported or impeded the refugee children’s disclosure of their life stories, views, and opinions. These barriers and facilitators can either reflect the difficulties and solutions the interviewers described in their own research methods (how the children were helped to disclose their experiences) or the factors that were described about the subject of the study (what the children or professionals told about disclosure factors).

Results

This section presents the various barriers to and facilitators for the disclosure of life stories by refugee minors, which were found in the selected studies. Table 2 presents the details of the 39 included articles and the main outcomes on the research question.

Table 2.

Overview of Selected Studies.

| Authors (Years) | Study Site | Study Population (Number of Participants, Age Range) | Data Collection Methods | Research Topics | Outcomes of the Research Question |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adams (2009) | United Kingdom | Unaccompanied and accompanied refugee minors (N = 7, 11–18) | Loosely structured interviews, social activities | Anthropologic view on refugee’s narratives | Facilitators: Two or three meetings, directed by the participants themselves, social activities chosen by the children (e.g., going to a café or the beach, window shopping, sharing a family meal, and helping with homework). |

| Almqvist and Brandell-Forsberg (1995) | Sweden | Iranian refugee children (N = 50, 4–8) | Semistructured interview with parents, Erica method (World Technique, Lowenfeld) | Assessment of effects of organized violence and forced migration on children | Facilitators: Opportunity for nonverbal self-expression by selection (content) and way of arranging (figuration) toys, children were encouraged to explain situations and talk about memories, placing dolls representing the child and family members on plates representing the home and host country. Important words were communicated in the own language. |

| Bek-Pedersen and Montgomery (2006) | Denmark | Accompanied refugee adolescents (N = 12, 16–18) | Open interviews, group interviews, observation, and interviews with the family | Refugee experience of children in families | Barriers: First interviews were formal and factual because participants did not feel at ease; telling life stories turned out to be a difficult task. Participants used nondisclosure to express their autonomous choice of silence. Facilitators: Interviews were directed by participants by limiting answers to some questions and going into detail with others; during second and group interviews, participants grew more confident and more personal topics could be discussed; and informal interaction during everyday activities. |

| Chase (2010) | United Kingdom | Unaccompanied refugee adolescents (N = 15, 11–23) | Semistructured interviews | Exploring factors affecting well-being | Barriers: Distancing from label of “asylum seeker,” fear for retraumatization, expecting negative reactions on disclosure, expecting others would not understand the situation, and wish to focus on future rather than on past. Association of social workers with aspects of the system related to surveillances. Maintaining a sense of agency and control over their lives. Facilitators: Children were encouraged to speak openly about life events and circumstances they considered as most relevant. Researchers met the child on more than one occasion. Notes were written when the child did not want the interview recorded. |

| Colucci, Minas, Szwarc, Guerra, and Paxton (2015) | Australia | Mental health providers (N = 115) to refugee youth | Focus group discussions (15) | Identifying barriers and facilitators to mental health services | Barriers: Direct probing into traumas, experiences in countries of origin may evoke fear of proving personal information, undergoing assessments and filling out forms, and fear of authority. Facilitators: Supporting clients with practical help, indirect approaches using the client’s interests, building a relationship and trust through being reliable and consistent, addressing “here and now” rather than immediately “digging into the past,” proving assurance of confidentiality. |

| Connolly (2014) | United Kingdom | Unaccompanied refugee minors (N = 29, 12–21) | Narrative interviews | Exploring experiences of children in foster care | Facilitators: Storytelling with focus on free association and human agency, participants could chose aspects that they considered as most relevant and select the order in which their storylines were configured. |

| Connolly (2015) | United Kingdom | Unaccompanied minors (N = 29, 12–21) | Narrative interviews | Exploring experiences with police and migration authorities | Barriers: Children felt confronted with a culture of superiority and a culture of disbelief, which made them feel the “enemy.” Majority felt that standardized and narrow methods during asylum interview restricted their capacity to vocalize their complex reasons for asking asylum. Facilitators: Investing time in fostering and enhancing relationships, providing information packs and individual information. |

| Crawley (2010) | United Kingdom | Unaccompanied adolescents (N = 27, ?) | Interviews | Exploring experiences during asylum interviews | Barriers: Lack of empathy and care in waiting area before the hearing, difficulties with recalling emotionally difficult events were not taking into account, feeling not being taken seriously and believed, feeling constrained by the questions, and lack of basic understanding of experiences in the home country. |

| De Haene, Grietens, and Verschueren (2010) | Belgium | Accompanied refugee children (n = 8, 4–9) and their parents (n = 11) | Individual and couple conversations (4) with parents; semistructured doll play with children | Explorative analysis of attachment relationships in the context of exile | Barriers: Narrating life stories reminded participants of interviews in asylum procedure and touched on experiences of being a victim of coercive power. Fear of remembering painful memories. Facilitators: Same interpreters during the research. Dialogue to encourage spontaneous input, refraining from direct probing into traumatic life events, providing space for autonomy of expressing personal experience; providing emotional closeness when parents experienced distress during conversations, allowing prolonged moments of silence; and establishing a climate of intimacy trough building an empathic relationship. Establishing fragments of meaning from fragmented life stories was positively valued. Doll play elicited children’s attachment narratives. |

| De Haene, Rober, Adriaenssens, and Verschueren (2012) | Belgium | Accompanied Caucasian refugee child (N = 1, 11) | Review and case study | Reflecting on dialogical refugee therapy | Facilitators: Drawing, play therapy, join choice to remain silent, not imposing expression, developing a collaborative encounter, finding respectful balance between remembering and forgetting, and informing the child about therapist’s inner speech and feelings. |

| Deveci (2012) | United Kingdom | Unaccompanied refugee adolescents | Describes the work of a practitioner working with separated children | Exploring holistic relationship approach to promoting well-being | Barriers: Difficulties trusting others, not wanting to talk about the past, inability of social workers to bear the pain of the child. Facilitators: Helping storytelling process by creating creative spaces for exploration, questioning, and expression without the use of language. |

| Due, Riggs, and Augoustinos (2014) | Australia | Accompanied refugee children (N = ?, 5–7) | Longitudinal design, participatory methodology, and variety of visuals methods | Researching educational experiences | Facilitators: Building rapport and establishing trust by spending time, playing, reading together, and home visits. Using nonlanguage-based methods, allowing children to express themselves in their own terms, drawings about experiences, social circle drawings, photos taken by the child, and placing smileys to experiences. Writing “about me” descriptions for children who preferred this method rather than talking. |

| Farley and Tarc (2014) | Sudan | Accompanied refugee child (N = 1, 13) | Case study | Psychoanalytic reading of war drawings | Facilitators: Drawings were consistent with historical records of war events and offered stark and intense symbolization of struggle. Factual and realistic questions about the drawing added details on the scene. |

| Hodes (2000) | United Kingdom | Accompanied and unaccompanied refugee children (N = 5, 11–16) | Review and case vignettes | Reflecting on several issues in mental health care | Barriers: Interviews/therapy reminds children of past experiences such as interrogation or even torture, reluctance to talk about past traumatic events, and wish to look to the future. Facilitators: Respecting refugees’ time orientation, establishing trust over time. |

| Jaffa (1996) | United Kingdom | Unaccompanied refugee (N = 1, 19) | Case study | Treatment of severely traumatized refugee | Facilitator: Time (several sessions) to build a bond of mutual trust. |

| Jones and Kafetsios (2002) | Bosnia | Accompanied refugee children (n = 40, 13–15, in de qualitative part; N = 337, 13–15, in quantitative part) | HSCL, HTQ, interviews with parents and children, lifelines, and observations | Comparing self-report symptom checklist with qualitative methods for assessing mental health | Barriers: Children were initially suspicions of anything connected with psychology. Admission of psychological difficulties was culturally stigmatized. Facilitators: Skilled translator from the community who was familiar with the project. Interviews during two or three sessions, wish for nondisclosure was respected, allowing children to frame their responses in their own terms, and the lead came from the child. Lifeline to explore past and present sense of psychological well-being. |

| Katsounari (2014) | United States | Unaccompanied Latino refugee (N = 1, 16) | Case study | Psychodynamic treatment | Barriers: Language difficulties, use of interpreter. Facilitators: Time to establish working relationship based on trust and a sense of safety, being attentive not to retraumatize the child by delving prematurely into traumatic memories. |

| Keselman, Cederborg, Lamb, and Dahlström (2010) | Sweden | Russian-speaking unaccompanied refugee adolescents (N = 26, 14–18) | Discourse analysis of 26 audio-recorded asylum hearings | Exploring interpreter’s influencing children’s participation during hearings | Barriers: Mistranslations affected the fact-finding process, quality of information was negatively affected when interpreters ignored or “improved” on the style and semantic choices of the minors. Focused questions elicited less accurate information and limited the freely recall of experiences, motives, and standpoints. Facilitators: Asylum-seeking adolescents were eager to disclose information that they understand was important to sustain their asylum claim, proving alternative explanations. Information was most accurate when answering open questions. |

| Kohli (2006) | United Kingdom | Unaccompanied asylum-seeking/refugee children (n = 34) | Interviews with social workers (n = 29) | Exploring responses of social workers to “silent” children | Barriers: Reluctance to talk about the past, too shocked to talk, instructions of those that sent the children; not concerned with looking backward, fear about the future, and silence helps managing distress. Facilitators: Taking time, wait till child is prepared, understanding the meaning of loss, showing interest in the child not as an asylum seeker, sympathetic understanding, capacity to look beyond the given story, making children feel welcome, offering reliable, and enduring companionship. |

| Kohli and Mather (2003) | United Kingdom | Unaccompanied refugee adolescents in service-proving project | Description of experiences in individual and group social work | Reflections on vulnerability and resilience | Barriers: Inability to talk in details about experiences until a “safe” stage of settlement is reached—silence is functional, not ready to talk about traumatic experiences. Facilitators: Simple questions about aspects of the children’s lives at home worked as catalyst to talk in depth about more painful experiences; waiting until children chose to disclose asylum stories. |

| Majumder, O’Reilly, Karim, and Vostanis (2015) | United Kingdom | Unaccompanied refugee adolescents (N = 15, 15–18) | Semistructured interviews | Collecting views on mental health services | Barriers: Feeling different, fundamental distrust of health services, feeling “not safe”; services “do not provide help,” distrust of mental health professionals in the home country, and fear for retraumatization. |

| Miles (2000) | Southeast Asia | Unaccompanied child soldiers (N = 60, 9–16) | Drawing, speaking about drawings | Research on militarized children’s hopes for future | Facilitators: Drawings about themselves in the past, present, and future and about the living context. Children were individually asked to explain what they had drawn, art proved to be useful to opening up communication. |

| Ní Raghallaigh (2014) | Ireland | Unaccompanied refugee adolescents (N = 32, 14–19) | In-depth qualitative interviews | Exploring reasons for mistrust | Barriers: Causes for mistrust: past experiences, being accustomed to mistrust, being mistrusted by others, not knowing people well, and concerns about truth telling. Facilitators: Respecting what children are willing to disclose, attempting building trust over time. |

| Oh (2012) | Thailand | Unaccompanied Burmese refugee children (N = 65, 10–17) | Visual ethnography to generative narratives | Research on refugee children’s feelings and memories | Facilitators: Pictures taken by the children and talking about these proved to be good technique to obtain information about children’s everyday life and could bring up memories of the past, providing insight to the researchers about the children’s experiences. Rapport, trust, and respect needed to be established before the children felt comfortable, researchers were mentors too before the research program started. Children had a say in the scheduling of research sessions. |

| Onyut et al. (2005) | Uganda | Unaccompanied and accompanied Somali refugee children (N = 6, 12–17) | Measurement of PTSD symptoms severity (PDS, Hopkins, and CIDI) | Evaluation of KIDNET therapy | Facilitators: Lifeline/rope, drawing, and role-play to help the children reconstructing their memories. |

| Rodríguez-Jiménez and Gifford (2010) | Australia | Afghan refugee adolescents (N = 16, 14–18) | Participatory media approach to narrate refugees experiences | Refugee’s reflections on belonging, becoming and identity | Barrier: Providing no structure in the beginning paralyzed the participants. Facilitators: Own production of a film about the refugee’s experiences and settlement gave them “a voice.” Experiences were explored in role-play, group games, storytelling, taking photographs of places where they felt comfortable and about their everyday life, and interviewing; space was created for expression not completely dependent on language. |

| Rousseau, Lacroix, Bagilishya, and Heusch (2003) | Canada | Accompanied refugee children (n = 19, 6–7; n = 21, 11–12) | Creative workshops, qualitative analyses of drawings and stories | Using myths to facilitate storytelling | Facilitators: Children were asked to tell a story about a character of their choice who experiences migration, children illustrated, and told stories (also those heard from parents and grandparents) about the home land: use of myths facilitated disclosure of experiences. |

| Rousseau, Measham, and Nadeau (2013) | Canada | Accompanied refugee children (N = 3, 6–7) | Case studies | Explanation of collaborative care model | Barriers: Silence as effective coping strategy in family story. Facilitators: Drawings, art therapy, the caregiver understands that refugee stories are not perfectly coherent and consistent. |

| Ruf et al. (2010) | Germany | Accompanied refugee children (N = 26, 7–16) | Measurement of PTSD symptoms severity | Evaluation of KIDNET therapy | Facilitators: Lifeline with rope, stones, and flowers, drawings were used to facilitate the production of language for the traumatic events. |

| Schauer et al. (2004) | Uganda | Accompanied Somali refugee child (N = 1, 13) | Case study | Description of KIDNET therapy sessions | Facilitator: Lifeline with rope, stones, and flowers was used to unfold the life story. |

| Schweitzer, Vromans, Ranke, and Griffin (2014) | Australia | Accompanied Liberian refugee (N = 1, 14) | Case study | Description of Tree of Life program | Facilitators: Narrative-based expressive arts intervention enabled the refugee child to adopt a preferred self-narrative. Sessions based on metaphors of different aspects of the tree helped the child to share narratives. |

| Servan-Schreiber, Le Lin, and Birmaher (1998) | India | Unaccompanied Tibetan refugee children (N = 61, 8–17) | Psychiatric interview to elicit DMS-IV criteria of PTSD and MDD | Assessing prevalence of PSTD and MDD | Barriers: “Cold” interviews without spending time with children were not possible. Children were shy and reluctant to disclose negative emotions. Facilitator: Interviews had to be preceded by information sessions, introducing the researchers and discussing previous experiences the children had with foreigners. |

| Sirriyeh (2013) | United Kingdom | Unaccompanied refugee minors (n = 21, 13–18) and foster carers (n = 23) | Interviews with carers and with children and focus groups with children (3) | Exploring challenges in hospitality in foster care families | Facilitators: Foster carers could accept and work with complexity in the children’s narratives, chose not to focus on troubling specifies, took the children’s side, and found points of empathy with the overall story. |

| Sourander (1998) | Finland | Unaccompanied refugee children (N = 46, 6–17) | Analyzing clinical and legal documents, CBCL | Researching traumatic events and behavioral symptoms | Barriers: Lack of trust: Structured psychiatric interviews were impossible because of cultural and linguistic barriers and the children’s insecure and distressing situation. Facilitator: Establishing warm empathic relation between interviewer and child. |

| St. Thomas and Johnson (2002) | United States | Accompanied refugee children (N = ?, ?) | Description of groups work method | Play and art activities with traumatized refugee children | Facilitators: After a period of building trust, the children were helped to express their life stories by combining outdoor activities with art, drama, creative expression, and storytelling without pressure or directives, assuring the children that they were in control of the content of play and art. |

| Thomas, Thomas, Nafees, and Bhugra (2004) | United Kingdom | Unaccompanied refugee minors (quantitative part: n = 100, 12–18; qualitative part: n = 67, 12–18) | Retrospective social services case file, legal statement review, and semistructured interview | Research on preflight experiences | Barriers: Reluctance to talk in detail about preflight experiences (one-third refused). Reasons mentioned: “Could not talk about experiences,” “problems in country of origin,” “had to keep experiences secret,” and “did not know why they had to leave.” Facilitator: Refugees could choose place and time for interviews, written notes were taken when refugee did not want the interview to be audio taped. |

| Vickers (2005) | United Kingdom | Unaccompanied African refugee (n = 1, 14), accompanied Balkan refugee (n = 1, 6) | Case studies | Review on cognitive therapy treatment PTSD | Barriers: Strategies to control threat: Suppressing any thoughts about the traumata, avoiding talking about past, and keeping emotional distance from people. Facilitator: Same interpreter during sessions. |

| Warr (2010) | United Kingdom | Counselors (n = 3) and children support advisors (n = 3) for young refugees | Qualitative interviews | Exploring counseling approaches | Facilitators: Creative methods to facilitate expressions of life stories were helpful: lifelines, stones and toy animals, dance groups, games, drawing, and painting. |

| White and Bushin (2011) | Ireland | Accompanied refugee children (n = ±45, ?) | Ten months of weekly sessions using a variety of methods to gain access to children’s experiences | Exploring child-centered participatory research methods | Barrier: Initially distrust with several children refusing to participate. Facilitators: Introduction of the researchers by staff the children knew, over time the children overcame their reluctance, relations of trust and distrust had to be (re)negotiated frequently, and flexibility to allow children to engage with methods in different ways which could be chosen by them. Drawing exercises, life-journeys and lifeline exercises, talk and play, map drawing, model making, photography, interviews, and discussion. |

Note. CBCL = Child Behavior Checklist; CIDI = Composite International Diagnostic Interview; DSM-IV = Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders IV; HSCL = Hopkins Symptom Checklist; HTQ = Harvard Trauma Questionnaire; KIDNET = Narrative Exposure Therapy for the treatment of traumatized children; PDS = Posttraumatic Diagnostic Scale; PTSD = Post Traumatic Stress Disorder.

Barriers to Disclosure

Mistrust

The main barrier that impedes refugee children’s ability to disclose their experiences lies in the mistrust children feel against authorities in general, including caretakers, researchers, migrations authorities, and interpreters (Deveci, 2012; Majumder, O’Reilly, Karim, & Vostanis, 2015; Ní Raghallaigh, 2014; Thomas et al., 2004). Ní Raghallaigh (2014) distinguishes five main categories of reasons for mistrust. First, aversive past experiences in the country of origin have a negative impact on the ability of the young refugees to trust people. These events are often linked with the reason to flee the country and can be both caused by the political situation in the country of origin or by the acts of previous trusted people in the private sphere. Second, some minor refugees say they are accustomed to mistrust; suspicion was a regular norm in their home country. Third, the young people feel they are mistrusted in the host country, which has a negative impact on their ability and willingness to trust others. Fourth, the discontinuity in social relations causes mistrust. The refugees say they just do not know people in the new context well enough in order to be able to detect persons who can be trusted. Fifth, the minor refugees are concerned with truth issues that affect their ability to trust. On the one hand, they fear deportation or repercussions against their relatives back home. On the other hand, some say the mistrust is caused by not sharing a truthful account of their life stories. They feel that lying or being silent about their background is a barrier to a reciprocal relation based on trust (Ní Raghallaigh, 2014). Others report that refugee children say they have to keep their experiences “secret” (Chase, 2010; Thomas et al., 2004), which is associated with the fifth category of reasons for mistrust in the study of Ní Raghallaigh (2014): the need to protect others in the country of origin. However, Kohli (2006) states that keeping secrets may also be just a normal expression of being an adolescent. Previous experiences that cause mistrust are also found in other studies. Refugees might, for instance, be forced to information sharing during interrogations or torture by authorities in the country of origin (Hodes, 2000). Sharing life stories in the host country might trigger then those memories of being a “victim of coercive power” (De Haene, Grietens, & Verschueren, 2010, p. 1669). Refugee children might also have endangered family members’ lives by sharing information in informal meetings with strangers (Colucci et al., 2015). These aversive experiences do not only cause mistrust that hampers children’s disclosure in the host country but might even cause selective mutism (Rousseau, Measham, & Nadeau, 2013).

Self-protection

Refugee children may choose to keep silent because they think it might harm them to talk about their experiences. Nondisclosure helps them to manage stress or cope with serious disturbance (Chase, 2010; Colucci et al., 2015; Kohli, 2006; Kohli & Mather, 2003; Thomas et al., 2004). Avoiding talking about threatening experiences in the past can be an effective strategy to control a current threat of intrusions like involuntary thoughts about traumata, flashbacks, and nightmares and being overwhelmed by these (Vickers, 2005). Some barriers for nondisclosure are related to maintaining a sense of agency and control over their lives, wanting to focus on the future, fearing retraumatization, and wanting to distance themselves from the label of “asylum seeker” (Chase, 2010).

Disrespect

The barrier “disrespect” refers to the child’s perception or expectation of limited trust or respect by others in the host community. In the context of asylum hearings, refugee children say, for instance, they felt confronted with a culture of disbelief, nonunderstanding, and superiority. The narrow and standardized interview methods made it hard for children to tell their life stories (Connolly, 2015). Minors experienced that their difficulties in recalling stressful events were not taken into account. A lack of empathy and care while waiting for the asylum hearing caused distress that was still felt during the interview (Crawley, 2010). Expecting negative or nonunderstanding reactions to disclosure hampers the revealing of life stories (Chase, 2010).

Facilitators for Disclosure

Positive and respectful attitude

Showing interest in the child by seeing them as young people who have to reinvent their lives instead of as “asylum seekers” and by offering reliable and enduring companionship is illustrations of a positive and respectful attitude (Kohli, 2006). By definition, unaccompanied children have to cope with loss of important bonds with the community they come from. An emphatic understanding to loss and pain can also be seen as an aspect of this method to enhance disclosure (Kohli, 2006). Crawley (2010) underlines the importance of making the child feel welcome as a way of showing respect, which is also helpful to facilitate disclosure of refugee children’s life stories. De Haene, Grietens, and Verschueren (2010, p. 1670) emphasize the need of “providing emotional closeness” when participants experience distress during conversations. A respectful attitude of the interviewer means also accepting the complexity in children’s narratives (Rousseau et al., 2013; Sirriyeh, 2013).

Taking time to build trust

A lot of studies describe how spending time with the children was necessary to facilitate the disclosure of the children’s stories. Time was used to build trust and rapport before children felt comfortable enough to share their life stories (Bek-Pedersen & Montgomery, 2006; Due, Riggs, & Augoustinos, 2014; Hodes, 2000; Jaffa, 1996; Katsounari, 2014; Oh, 2012; St. Thomas & Johnson, 2002; White & Bushin, 2011). Talking about the experiences in detail might be impossible until a “safe” phase of resettlement is reached (Kohli & Mather, 2003).

The time that can be spent on building trust varies a lot in different contexts of communication. For the therapist, working on a trustful relationship is an inherent part of the therapeutic process (Colluci et al., 2015; Hodes, 2000; Jaffa, 1996; Katsounari, 2014; St. Thomas & Johnson, 2002). Social workers and foster carers have a more practical view on trust as a necessity for being able to perform their task as service and care providers (Kohli, 2006; Sirriyeh, 2013). However, also in studies reflecting research done under high time pressure constraints (Bek-Pedersen & Montgomery, 2006; Servan-Schreiber, Le Lin, & Birmaher, 1998; Sourander, 1998) and within the context of asylum hearings (Connolly, 2015), the need to build rapport is recognized as a facilitator for refugee children’s disclosure of their life stories.

Some researchers found ways to build trust by helping children with practical needs like helping with homework first or by joining children in social activities like having dinner (Adams, 2009; Colucci et al., 2015). St. Thomas and Johnson (2002) describe how a group of refugee children went for a 3 days hiking to a fishing lodge in the mountains together with professionals from a center that supports children who are coping with grieve. This shared journey provided the children with an opportunity—which they grasped —to talk about personal losses.

Nonverbal methods

A wide variety of nonverbal methods are found to facilitate narrative interviewing of refugee children within the context of research and mental health. Due to age, language difficulties, traumatic experiences, and cultural differences, these children profit from an interviewer’s creative package of working methods. Drawing about experiences, symbolizing social relations, and drawing self-portraits proved to be useful instruments (De Haene, Rober, Adriaenssens, & Verschueren, 2012; Due et al., 2014; Farley & Tarc, 2014; Jones & Kafetsios, 2002; Miles, 2000; Onyut et al., 2005; Rousseau, Lacroix, Bagilishya, & Heusch, 2003; Rousseau et al., 2013; Schweitzer, Vromans, Ranke, & Griffin, 2014; Warr, 2010; White & Bushin, 2011). Lifelines were used to elicit life stories of the refugee children, sometimes by drawing a line, pointing out important life events (Warr, 2010). Others used a rope and asked children to place stones for bad experiences and flowers for good experiences along the rope (Onyut et al., 2005; Ruf et al., 2010; Schauer et al., 2004).

Other nonverbal methods that facilitated disclosure were photographs taken by the children (Due et al., 2014; Oh, 2012; White & Bushin, 2011), making a film (Rodríguez-Jiménez & Gifford, 2010), and doll play or role-play (Almqvist & Brandell-Forsberg, 1995; De Haene et al., 2010: Onyut et al., 2005; Warr, 2010).

In these studies, drawings and lifelines were used as an entrance for speaking rather than as autonomous diagnostic instruments. However, the 500 drawings of Sudanese children from Darfur proved to be very consistent with historical records of the atrocities in Darfur and are even used as supportive evidence in proceedings of the International Criminal Court (Farley & Tarc, 2014).

Providing agency

Providing agency to children is found to be an indispensable facilitator for disclosure. It can have practical implications like giving children a voice in the logistics of the interview setting (Adams, 2009; Chase, 2010; Oh, 2012; Thomas et al., 2004) and the (non)recording of interviews (Chase, 2010; Thomas et al., 2004). Moreover, providing agency is done by following children’s choices in subjects, timing in the communication, and using their own terms in describing symptoms or their well-being instead of following the wordings of formal clinical instruments (Adams, 2009; Almqvist & Brandell-Forsberg, 1995; Bek-Pedersen & Montgomery, 2006; Chase, 2010; Connolly, 2014; De Haene et al., 2010; Jones & Kafetsios, 2002; Kohli & Mather, 2003; Ní Raghallaigh, 2014; Sirriyeh, 2013; St. Thomas & Johnson, 2002). Following the child’s wish for nondisclosure was found to be crucial. This is reflected in “finding a respectful balance between remembering and forgetting” and “not imposing expression” (De Haene et al., 2012, p. 401). Also, the flexibility regarding the children’s choices of most preferred methods of expression worked as a facilitator and can be seen as a way of providing agency to the children (Almqvist & Brandell-Forsberg, 1995; Rodríguez-Jiménez & Gifford, 2010; White & Bushin, 2011). On the other hand, providing no structure at all at the beginning of the activities paralyzed participants in Rodríguez-Jiménez and Gifford’s (2010) research.

Trained interpreters

Research of Keselman, Cederborg, Lamb, and Dahlström (2010) has proven that a skilled interpreter is not only enhancing the refugee children’s sharing of their life stories during asylum hearings but is also crucial for the accuracy of the children’s answers. The validity of the information children share in the asylum hearings is, for instance, negatively affected when the interpreters ignore or “improve” the minors’ own terms and style (Keselman, Cederborg, Lamb, & Dahlström, 2010). Some studies name the use of the same skilled interpreters during various sessions with the same children as a facilitator in the communication with children (De Haene et al., 2010; Jones & Kafetsios, 2002; Vickers, 2005). Other studies mention that refugee children preferred to talk without an interpreter, accepting a lower level of understanding above the discomfort that they felt with an interpreter (Katsounari, 2014; Rousseau et al., 2013). Almqvist and Brandell-Forsberg (1995) learned themselves some key words in the child’s language which they thought were necessary for being able to instruct the interpreters about the important concepts in their assessments.

Discussion

The systematic review presented in this article provides an overview of the facilitators for and barriers to refugee children’s disclosure of their life stories known in the social sciences field. The results address both migration authorities and other professionals who are involved with refugee children. The main barriers that were found were the mistrust the children might feel against interviewers, their self-protection, and a feeling or expectation of being disrespected in the host country. These barriers may make it difficult for refugee minors to share their life stories, also with immigration authorities, who have to find out whether the child is in need of protection. The main facilitators for the refugee children’s disclosure of their life stories are a positive and respectful attitude, taking time to build trust, using nonverbal methods, providing agency, and the involvement of trained interpreters.

In the following paragraphs, we distinguish three areas of tension with practicing the results of this review in the context of the child’s asylum procedure: (1) the need of taking time versus the need of an expeditious asylum procedure, (2) respect for nondisclosure versus assessing the child’s protection needs, and (3) tensions between the different roles of professionals involved with the child and the asylum procedure.

Taking time to build trust was mentioned in nearly all studies as an inevitable tool to help refugee children to share their stories. In the clinical and social work context, taking time to build trust seems to be self-evident. In the world of refugee children involved in asylum procedures, time is an ambiguous concept. Stability and continuity in living circumstances is one of the conditions for a good development of the child (Zijlstra, 2012, pp. 37–38). Therefore, children do also benefit from an assessment of their asylum claim and protection needs being made as quickly as possible (Shamseldin, 2012). Although asylum hearings could endure for several hours, not much time is invested in softening feelings of mistrust (Connolly, 2015; Crawley, 2010). In some sense, this seems to be a “mission impossible,” since in the clinical context, disclosure of refugee’s experiences is a long, dialogical process and not a single event (De Haene et al., 2012; Reitsema & Grietens, 2015), while an asylum hearing is usually a once-only opportunity (UNHCR, 2014, p. 106). Ehntholt and Yule (2006) even state that it can be too difficult for young refugees to share their most painful memories when they still feel the threat that they could be deported. On the other hand, it may be precisely these “most painful memories” that reflect the reason why a child is in need of refugee protection and these should therefore be disclosed to those who decide upon the asylum request within the time constraints of the asylum procedure.

Providing agency to children to encourage their disclosure of life stories has a practical, logistically aspect and refers also to giving the children the lead in the interview. Providing agency is also a difficult concept in the asylum context. In general, children themselves will realize which parts of their life are most relevant to speak about. They are the experts about their own life narratives. Interviewers should encourage children to become the authors of their life stories (van Nijnatten & Van Doorn, 2007). On the other hand, a child who claims to be in need of refugee protection in the host country has to reveal what happened in the home country that caused the “well-founded fear” that should be assessed in the asylum procedure (UN, 1951, art. 1A). Unconditionally respecting silence and providing agency could put the child in danger of being deported to his or her home country, while his or her safety is not guaranteed (McAdam, 2006).

It became evident through this review that just talking is often not enough to encourage refugee children to share their life stories. Using nonverbal methods and undertaking social activities are often mentioned as facilitators. In pedagogy, undertaking social activities has always been seen as an essential opportunity for parents and children to share experiences and feelings in a natural and informal way (Langeveld, 1942; Ter Horst, 1977). Likewise, professionals focused on children’s disclosure of experiences within the asylum context could think about ways to combine doing with talking, for example, by using nonverbal working methods during interviews. However, the question is whether the immigration authorities’ role is suitable for those informal and indirect encouragements to disclose relevant details of the asylum story. They are not professionals educated in clinical diagnostics whose only focus can be to serve the best interests of the child in the disclosing process. Migration authorities have to serve the best interests of the migration policy of the host country as well (Pobjoy, 2017, p. 199). It is imaginable that a broader disclosure, leading to a “thick story,” provides more inconsistencies in the story, which may lead to a rejection of the asylum claim on the ground of credibility issues (Kohli, 2006; Warren & York, 2014, p. 16).

Strengths and Limitations

One of this study’s strengths is the thorough systematic cross-contextual approach to the disclosure of refugee’s life stories. While aiming to highlight the practical implications for the asylum procedure, this overview provides knowledge from other contexts of communication as well.

One of this review’s limitations is that it does not compare the impact the different facilitators have on the extent to which children disclose their life stories. The reported facilitators for the disclosure of life stories show how —not how much —disclosure could be facilitated (or was hampered) working with the refugee children.

Another limitation concerns the validity of the life stories in relation to the use of facilitators for children’s disclosure. This aspect was not the focus of the included studies with one exception: Research on the role of translators did address the accuracy of the retrieved information (Keselman, Cederborg, Lamb, et al., 2010).

Implications for Further Research

While a lot of research has been done on facilitators for the disclosure of traumatic events by abused children in forensic interviews (Saywitz et al., 2011), there is little research on this subject within the context of asylum hearings (UNHCR, 2014). There is an urgent need for such research because important decisions about the refugee child’s protection needs are highly influenced by the way the child is helped to tell about past experiences.

Some described facilitators for disclosure are associated with interview skills: an open and respectful attitude, providing agency, respecting silences, and avoiding direct probing could all be leading to a focus on posing open instead of closed questions. However, completely unstructured interviews with many silences might be frightening for refugee children (Vickers, 2005). Research on how to find a balance between open and closed interview styles is therefore recommended.

Recommendations for Practice

Revealing the life story

For unaccompanied children, it could be fruitful if migration authorities were to postpone the asylum assessment until the mentor or guardian has been able to help the child to reveal his or her life story. These professionals should work with the child soon after arrival to find out what happened to the child to make him or her feel a need for protection and how the best interests of the child were determined by the child itself and those who cared for the child before departure (Bhabha, 2014, p. 204; Vervliet et al., 2014). Providing agency and building trust are easier secured in the relationship between professionals who work on a daily base with the child than for migration authorities who see the child only once or twice; taking time to facilitate the disclosure of the child’s life story is better possible in a dialogical process (Dalgaard & Montgomery, 2015; De Haene et al., 2012; Reitsema & Grietens, 2015). Once the professionals and the child have succeeded in revealing the life story, the migration authorities could assess the story based on the requirements set out in migration policy. At the same time, it is important that professionals involved with refugee children stick to their own roles and ethical principles laid down in codes of conduct. For mental health professionals and social workers ensuring confidentiality, beneficence and nonmaleficence to their clients are leading ethical principles (American Psychological Association, 2017, principles A, B; National Association of Social Workers [NASW], 2017, para. 1.01, 1.07). The core standards for guardians of unaccompanied children stipulate that guardians have the task to advocate decisions to be taken in the best interests of unaccompanied children (Goeman et al., 2011, Core Standards 1, 8). Working with the child, these professionals might come across information that could be useful for the migration authorities’ task to assess the credibility of the child’s asylum claim while sharing this information would not serve the child’s best interests and would violate their ethical principles (American Psychological Association, 2017, para. 1.02; Goeman et al., 2011, pp. 35–36; NASW, 2017, para. 1.06).

Migrations authorities and interpreters trained in child development

Further training in communication with refugee children is needed for all professionals involved in the asylum context (UNHCR, 2014, p. 105). Interpreters for children involved in asylum procedures and migration authorities should be trained in how to establish trust and in child—and cultural-specific interpretation. Interpreters should respect and reflect the child’s answers in their own words and refrain from reframing, judging, and discrediting the child’s voice (Keselman, Cederborg, & Linell, 2010; UNHCR, 2014, pp. 124–131).

A lot of refugee children suffer from traumatic experiences and related mental health problems (Fazel, Reed, Panter-Brick, & Stein, 2012). Therefore, professionals involved in interviewing refugee children, including interpreters, should be trained in how these children may experience difficulties in recalling and describing the adverse events to ensure the professionals’ comprehension of the child’s hesitations in the communication (Saywitz et al., 2011).

The UNCRC encourages involving a multidisciplinary team whenever a best interests of the child determination has to be made (GC 14, para. 94). This review reveals the importance of migration authorities and other professionals like child psychologists, social workers, and interpreters to be able to speak with the refugee child and to listen to narratives as well as silences. Making a decision on a refugee child’s need for protection requires decision makers, interpreters, and those who provide information on the child to be trained in child development in general; and specifically in the problems, refugee children might experience in disclosing their life stories (UNHCR, 1992, para. 214; 2009, para. 72).

Knowing how to support refugee children in disclosing their reasons for asking international protection—and practicing this knowledge—would bring progression to the implementation of the children’s right to participation (CRC, art. 12) because then children will be “recognised as important actors in the realisation of their rights” (Arnold, 2018, p. 58).

Author Biographies

E. C. C. (Carla) van Os, MSc, LLM, is graduated in law as well as orthopedagogy. She works at the Study Centre for Children, Migration and Law on a PhD concerning the best interests of the child determination in the asylum procedure for recently arrived refugee children. The Study Centre writes on request of lawyers or guardians diagnostic behavioral scientific reports about which decision is in the best interests of the child.

A. E. (Elianne) Zijlstra, PhD, is a behavioral scientist at the multidisciplinary Study Centre for Children, Migration and Law, University of Groningen, the Netherlands. She conducts behavioral scientific research on children in legal decision-making in migration law, more specific about the assessment and determination of the best interests of the child. She has a special interest in trauma, vulnerability, and resilience of refugee children.

E. J. (Erik) Knorth, PhD, is full professor of child and youth care at the Department of Special Needs Education and Youth Care, University of Groningen, the Netherlands. His research is on child and family welfare, with a special interest in children and adolescents with emotional and behavioral problems who are (at risk of being) placed in family foster or residential care.

W. J. (Wendy) Post, PhD, is an associate professor of methodology and statistics at the Centre for Special Needs Education and Youth Care, University of Groningen, the Netherlands. The focus in her research is on validity issues (statistical conclusion, internal, construct, and external validity). Her special interests are advanced statistical modeling, measurement theory, and scientific integrity (ethics).

M. E. (Margrite) Kalverboer, PhD, LLM, is a professor by special appointment of Child, Pedagogy and Migration Law at the University of Groningen, the Netherlands. She graduated in law as well as orthopedagogy at the University of Groningen and researches the development of children and their legal position in migration law, civil law, and criminal law. She is the children’s ombudsperson in the Netherlands.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This research was funded by a grant (no. 8393310) from the Foundation for Children’s Welfare Stamps Netherlands.

References

References marked with an asterisk indicate studies included in the meta-analysis.

- *Adams M. (2009). Stories of fracture and claim for belonging: Young migrants’ narratives of arrival in Britain. Children’s Geographies, 7, 159–171. doi:10.1080/14733280902798878 [Google Scholar]

- *Almqvist K., Brandell-Forsberg M. (1995). Iranian refugee children in Sweden: Effects of organized violence and forced migration on preschool children. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 65, 225–237. doi:10.1037/h0079611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychological Association. (2017). Ethical principles and code of psychologists and their code of conduct. Retrieved from http://www.apa.org/ethics/code/

- Anderson G. D., Anderson J. N., Gilgun J. F. (2014). The influence of narrative practice techniques on child behaviors in forensic interviews. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse, 23, 615–634. doi:10.1080/10538712.2014.932878 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold A. (2018). Children’s rights and refugee law. Conceptualising children within the refugee convention. New York, NY: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- *Bek-Pedersen K., Montgomery E. (2006). Narratives of the past and present: Young refugees’ construction of a family identity in exile. Journal of Refugee Studies, 19, 94–112. doi:10.1093/jrslfej003 [Google Scholar]

- Bhabha J. (2014). Child migration and human rights in a global age. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Björnberg U. (2011). Social relationships and trust in asylum seeking families in Sweden. Sociological Research Online, 16, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Booth A., Papaioannou D., Sutton A. (2012). Systematic approaches to a successful literature review. London, England: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- *Chase E. (2010). Agency and silence: Young people seeking asylum alone in the UK. British Journal of Social Work, 40, 2050–2068. doi:10.1093/bjsw/bcp103 [Google Scholar]

- Chase E. (2013). Security and subjective wellbeing: The experiences of unaccompanied young people seeking asylum in the UK. Sociology of Health & Illness, 35, 858–872. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9566.2012.01541.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Colucci E., Minas H., Szwarc J., Guerra C., Paxton G. (2015). In or out? Barriers and facilitators to refugee-background young people accessing mental health services. Transcultural Psychiatry, 52, 766–790. doi:10.1177/1363461515571624 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Connolly H. (2014). “For a while out of orbit”: Listening to what unaccompanied asylum-seeking/refugee children in the UK say about their rights and experiences in private foster care. Adoption & Fostering, 38, 331–345. doi:10.1177/0308575914553360 [Google Scholar]

- *Connolly H. (2015). Seeing the relationship between the UNCRC and the asylum system through the eyes of unaccompanied asylum seeking children and young people. International Journal of Children’s Rights, 23, 52–77. doi:10.1163/15718182-02301001 [Google Scholar]

- *Crawley H. (2010). “No one gives you a chance to say what you are thinking”: Finding space for children’s agency in the UK asylum system. Area, 42, 162–169. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4762.2009.00917.x [Google Scholar]

- Dalgaard N. T., Montgomery E. (2015). Disclosure and silencing: A systematic review of the literature on patterns of trauma communication in refugee families. Transcultural Psychiatry, 0, 1–15. doi:10.1177/1363461514568442 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *De Haene L., Grietens H., Verschueren K. (2010). Holding harm: Narrative methods in mental health research on refugee trauma. Qualitative Health Research, 20, 1664–1676. doi:10.1177/1049732310376521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *De Haene L., Rober P., Adriaenssens P., Verschueren K. (2012). Voices of dialogue and directivity in family therapy with refugees: Evolving ideas about dialogical refugee care. Family Process, 51, 391–404. doi:10.1111/j.1545-5300.2012.01404.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Deveci Y. (2012). Trying to understand: Promoting the psychosocial well-being of separated refugee children. Journal of Social Work Practice, 26, 367–383. doi:10.1080/02650533.2012.658033 [Google Scholar]

- Drywood E. (2010). Challenging concepts of the ‘child’ in asylum and immigration law: The example of the EU. Journal of Social Welfare & Family Law, 32, 309–323. doi:10.1080/09649069.2010.520524 [Google Scholar]

- *Due C., Riggs D. W., Augoustinos M. (2014). Research with children of migrant and refugee backgrounds: A review of child-centered research methods. Child Indicators Research, 7, 209–227. [Google Scholar]

- Dursun A., Sauer B. (2017). Asylum experiences in Austria from a perspective if unaccompanied minors: Best interests of the child in reception procedures and everyday life In Sedmak M., Sauer B., Gornik B. (Eds.), Unaccompanied children in European migration and asylum practices: In whose best interests? (pp. 86–109). New York, NY: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Ehntholt K. A., Yule W. (2006). Practitioner review: Assessment and treatment of refugee children and adolescents who have experienced war-related trauma. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines, 47, 1197–1210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Farley L., Tarc A. M. (2014). Drawing trauma: The therapeutic potential of witnessing the child’s visual testimony of war. Journal of the American Psychoanalytic Association, 62, 835–854. doi:10.1177/0003065114554419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fazel M., Reed R. V., Panter-Brick C., Stein A. (2012). Mental health of displaced and refugee children resettled in high-income countries: Risk and protective factors. Lancet, 379, 266–282. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60051-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goeman M., van Os C., Bellander E., Fournier K., Gallizia G., Arnold S.…Uzelac M. (2011). Closing a protection gap. Core Standards for guardians of separated children. Leiden, the Netherlands: Defence for Children; Retrieved from http://www.corestandardsforguardians.com/images/22/335.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Gornik B., Sedmak M., Sauer B. (2017). Unaccompanied minor migrants in Europe: Between compassion and repression In Sedmak M., Sauer B., Gornik B. (Eds.), Unaccompanied children in European migration and asylum practices: In whose best interests? (pp. 1–15). New York, NY: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Herlihy J., Scragg P., Turner S. (2002). Discrepancies in autobiographical memories—Implications for the assessment of asylum seekers: Repeated interviews study. British Medical Journal (Clinical Research Ed.), 324, 324–327. doi:10.1136/bmj.324.7333.324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herlihy J., Turner S. (2006). Should discrepant accounts given by asylum seekers be taken as proof of deceit? Torture, 16, 81–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Hodes M. (2000). Psychological distressed refugee children in the United Kingdom. Child Psychology & Psychiatry Review, 5, 57–68. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.01912.x [Google Scholar]

- *Jaffa T. (1996). Case report: Severe trauma in a teenage refugee. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 1, 347–351. doi:10.1177/1359104596013004 [Google Scholar]

- *Jones L., Kafetsios K. (2002). Assessing adolescent mental health in war-affected societies: The significance of symptoms. Child Abuse & Neglect, 26, 1059–1080. doi:10.1016/S0145-2134(02)00381-2 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalverboer M., Beltman D., van Os C., Zijlstra E. (2017). The best interests of the child in cases of migration: Assessing and determining the best interests of the child in migration procedures. International Journal of Children’s Rights, 25, 114–139. doi:10.1163/15718182-02501005 [Google Scholar]

- *Katsounari I. (2014). Integrating psychodynamic treatment and trauma focused intervention in the case of an unaccompanied minor with PTSD. Clinical Case Studies, 13, 352–367. doi:10.1177/1534650113512021 [Google Scholar]

- *Keselman O., Cederborg A., Lamb M. E., Dahlström Ö. (2010). Asylum-seeking minors in interpreter-mediated interviews: What do they say and what happens to their responses? Child & Family Social Work, 15, 325–334. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2206.2010.00681.x [Google Scholar]

- Keselman O., Cederborg A., Linell P. (2010). “That is not necessary for you to know!” Negotiation of participation status of unaccompanied children in interpreter-mediated asylum hearings. Interpreting: International Journal of Research & Practice in Interpreting, 12, 83–104. doi:10.1075/intp.12.1.04kes [Google Scholar]

- *Kohli R. K. S. (2006). The sound of silence: Listening to what unaccompanied asylum-seeking children say and do not say. British Journal of Social Work, 36, 707–721. [Google Scholar]

- Kohli R. K. S. (2011). Working to ensure safety, belonging and success for unaccompanied asylum-seeking children. Child Abuse Review, 20, 311–323. doi:10.1093/bjsw/bch305 [Google Scholar]

- *Kohli R. K. S., Mather R. (2003). Promoting psychosocial well-being in unaccompanied asylum seeking young people in the United Kingdom. Child & Family Social Work, 8, 201–212. [Google Scholar]

- Langeveld J. (1942). Handelen en denken in de opvoeding en opvoedkunde [Acting and thinking in education and pedagogy]. Groningen, the Netherlands: Wolters’ Uitgeversmaatschappij. [Google Scholar]

- Leander L. (2010). Police interviews with child sexual abuse victims: Patterns of reporting, avoidance and denial. Child Abuse & Neglect, 34, 192–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lidén H., Rusten H. (2007). Asylum, participation and the best interests of the child: New lessons from Norway. Children & Society, 21, 273–283. doi:10.1111/j.1099-0860.2007.00099.x [Google Scholar]

- *Majumder P., O’Reilly M., Karim K., Vostanis P. (2015). “This doctor, I not trust him, I’m not safe”: The perceptions of mental health and services by unaccompanied refugee adolescents. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 61, 129–136. doi:10.1177/0020764014537236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAdam J. (2006). Seeking asylum under the Convention on the Rights of the Child: A case for complementary protection. International Journal of Children’s Rights, 14, 251–274. doi:10.1163/157181806778458130 [Google Scholar]

- McKelvey R. S. (1994). Refugee patients and the practice of deception. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 64, 368–375. doi:10.1037/h0079542 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Miles G. M. (2000). Drawing together hope: ‘Listening’ to militarised children. Journal of Child Health Care, 4, 137–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery E. (2004). Tortured families: A coordinated management of meaning analysis. Family Process, 43, 349–371. doi:10.1111/j.1545-5300.2004.00027.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mordock J. B. (2001). Interviewing abused and traumatized children. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 6, 271–291. doi:10.1177/1359104501006002008 [Google Scholar]

- National Association of Social Workers (NASW). (2017). Code of ethics of the National Association of Social Workers. Washington, DC: Author. [Google Scholar]

- *Ní Raghallaigh M. (2014). The causes of mistrust amongst asylum seekers and refugees: Insights from research with unaccompanied asylum-seeking minors living in the Republic of Ireland. Journal of Refugee Studies, 27, 82–100. [Google Scholar]

- *Oh S. (2012). Photofriend: Creating visual ethnography with refugee children. Area, 44, 282–288. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4762.2012.01111.x [Google Scholar]

- *Onyut L. P., Neuner F., Schauer E., Ertl V., Odenwald M., Schauer M., Elbert T. (2005). Narrative exposure therapy as a treatment for child war survivors with posttraumatic stress disorder: Two case reports and a pilot study in an African refugee settlement. BMC Psychiatry, 5, 7–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ottosson L., Lundberg A. (2013). “People out of place?” Advocates’ negotiations on children’s participation in the asylum application process in Sweden. International Journal of Law, Policy & the Family, 27, 266–287. [Google Scholar]

- Petticrew M., Roberts H. (2006). Systematic reviews in the social sciences: A practical guide. Malden, MA: Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Pobjoy J. M. (2017). The child in international refugee law. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Reitsema A. M., Grietens H. (2015). Is anybody listening? The literature on the dialogical process of child sexual abuse disclosure reviewed. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 17, 330–340. doi:10.1177/1524838015584368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Rodríguez-Jiménez A., Gifford S. M. (2010). “Finding voice” Learnings and insights from a participatory media project with recently arrived Afghan young men with refugee backgrounds. Youth Studies Australia, 29, 33–41. [Google Scholar]

- *Rousseau C., Lacroix L., Bagilishya D., Heusch N. (2003). Working with myths: Creative expression workshops for immigrant and refugee children in a school setting. Art Therapy, 20, 3–10. doi:10.1080/07421656.2003.10129630 [Google Scholar]

- *Rousseau C., Measham T., Nadeau L. (2013). Addressing trauma in collaborative mental health care for refugee children. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 18, 121–136. doi:10.1111/j.1475-3588.2010.00589.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Ruf M., Schauer M., Neuner F., Catani C., Schauer E., Elbert T. (2010). Narrative exposure therapy for 7- to 16-year-olds: A randomized controlled trial with traumatized refugee children. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 23, 437–445. doi:10.1002/jts.20548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saywitz K. J., Lyon T. D., Goodman G. S. (2011). Interviewing children In Myers J. E. B. (Ed.), The APSAC handbook on child maltreatment (pp. 337–360). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- *Schauer E., Neuner F., Elbert T., Ertl V., Onyut L. P., Odenwald M., Schauer M. (2004). Narrative exposure therapy in children: A case study. Intervention: International Journal of Mental Health, Psychosocial Work & Counselling in Areas of Armed Conflict, 2, 18–32. [Google Scholar]

- *Schweitzer R. D., Vromans L., Ranke G., Griffin J. (2014). Narratives of healing: A case study of a young Liberian refugee settled in Australia. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 41, 98–106. doi:10.1016/j.aip.2013.10.006 [Google Scholar]

- *Servan-Schreiber D., Le Lin B., Birmaher B. (1998). Prevalence of posttraumatic stress disorder and major depressive disorder in Tibetan refugee children. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 37, 874–879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shamseldin L. (2012). Implementation of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child 1989 in the care and protection of unaccompanied asylum seeking children: Findings from empirical research in England, Ireland and Sweden. International Journal of Children’s Rights, 20, 90–121. doi:10.1163/157181811X570717 [Google Scholar]

- *Sirriyeh A. (2013). Hosting strangers: Hospitality and family practices in fostering unaccompanied refugee young people. Child & Family Social Work, 18, 5–14. doi:10.1111/cfs.12044 [Google Scholar]

- *Sourander A. (1998). Behavior problems and traumatic events of unaccompanied refugee minors. Child Abuse & Neglect, 22, 719–727. doi:10.1016/S0145-2134(98)00053-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer L., Ritchie J., Lewis J., Dillon L. (2003). Quality in qualitative evaluation: A framework for assessing research evidence. London, England: Government Chief Social Researcher’s Office. [Google Scholar]