Abstract

Background

The role of prostaglandins for cervical ripening and induction of labour has been examined extensively. Human semen is the biological source that is presumed to contain the highest prostaglandin concentration. The role of sexual intercourse in the initiation of labour is uncertain. The action of sexual intercourse in stimulating labour is unclear, it may in part be due to the physical stimulation of the lower uterine segment, or endogenous release of oxytocin as a result of orgasm or from the direct action of prostaglandins in semen. Furthermore nipple stimulation may be part of the process of initiation.

This is one of a series of reviews of methods of cervical ripening and labour induction using standardised methodology.

Objectives

To determine the effects of sexual intercourse for third trimester cervical ripening or induction of labour in comparison with other methods of induction.

Search methods

The Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group's Trials Register (June 2007) and bibliographies of relevant papers.

Selection criteria

Clinical trials comparing sexual intercourse for third trimester cervical ripening or labour induction with placebo/no treatment or other methods listed above it on a predefined list of labour induction methods.

Data collection and analysis

A strategy was developed to deal with the large volume and complexity of trial data relating to labour induction. This involved a two‐stage method of data extraction.

Main results

There was one included study of 28 women which reported very limited data, from which no meaningful conclusions can be drawn.

Authors' conclusions

The role of sexual intercourse as a method of induction of labour is uncertain. This is an important issue to pregnant women and their partners. There is a need for well‐designed randomised controlled trials to assess the impact of sexual intercourse on the onset of labour. Any future trials investigating sexual intercourse as a method of induction need to be of sufficient power to detect clinically relevant differences in standard outcomes.

Plain language summary

Sexual intercourse for cervical ripening and induction of labour

The role of sexual intercourse as a method for induction of labour is uncertain.

Human sperm contains a high amount of prostaglandin, a hormone‐like substance which ripens the cervix and helps labour to start. Sometimes it is necessary to help start labour and it has been suggested that sexual intercourse may be an effective means. However, there is not enough evidence to show whether sexual intercourse is effective or to show how it compares with other methods. More research is needed.

Background

Sometimes it is necessary to bring on labour artificially because of safety concerns for the mother or baby. This review is one of a series of reviews of methods of labour induction using a standardised protocol. For more detailed information on the rationale for this methodological approach, please refer to the currently published 'generic' protocol (Hofmeyr 2000). The generic protocol describes how a number of standardised reviews will be combined to compare various methods of preparing the cervix of the uterus and inducing labour.

Sexual intercourse at term has been associated with earlier onset of labour and reduced need for induction at 41 weeks' gestation (Tan 2006). It is a non‐medical method allowing the woman greater control over the process of attempting to induce labour. The action of sexual intercourse in stimulating labour remains unclear, it may in part be due to the physical stimulation of the lower uterine segment, or endogenous release of oxytocin as a result of orgasm or from the direct action of prostaglandins in semen. The role of prostaglandins for cervical ripening and induction of labour have been examined extensively. Human semen is the biological source that is presumed to contain the highest prostaglandin concentration (Benvold 1987). Furthermore, nipple stimulation may be part of the process of initiation. The impact of sexual intercourse on the onset of labour is an important issue to pregnant women and their partners. Tan and colleagues found that the likelihood of sexual intercourse at term was affected by women's perceptions of safety (Tan 2006). A survey of women and their partners attending antenatal clinics found that 86% of women and 93% of men wanted to know if sexual intercourse influences the onset of labour, and that knowledge of its impact would have an effect on sexual activity at term (Tomlinson 1999).

Objectives

To determine the effects of sexual intercourse for third trimester cervical ripening or induction of labour in comparison to other methods of induction.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Clinical trials comparing sexual intercourse for cervical ripening or labour induction, with other methods listed above it on a predefined list of methods of labour induction (see 'Methods of the review'); the trials included some form of random allocation to either group; and they reported one or more of the prestated outcomes.

Types of participants

Pregnant women due for third trimester induction of labour, carrying a viable fetus.

Predefined sub‐group analyses will be (see list below): previous caesarean section or not; nulliparity or multiparity; membranes intact or ruptured, and cervix unfavourable, favourable or undefined.

Types of interventions

Trials comparing sexual intercourse with any other intervention above it in the predefined list (see 'Methods of the review').

Types of outcome measures

Clinically relevant outcomes for trials of methods of cervical ripening/labour induction have been prespecified by two authors of labour induction reviews (Justus Hofmeyr and Zarko Alfirevic). Differences were settled by discussion.

Five primary outcomes were chosen as being most representative of the clinically important measures of effectiveness and complications. Sub‐group analyses will be limited to the primary outcomes:

(1) vaginal delivery not achieved within 24 hours (or period specified by trial authors); (2) uterine hyperstimulation with fetal heart rate (FHR) changes; (3) caesarean section; (4) serious neonatal morbidity or perinatal death (e.g. seizures, birth asphyxia defined by trialists, neonatal encephalopathy, disability in childhood); (5) serious maternal morbidity or death (e.g. uterine rupture, admission to intensive care unit, septicaemia).

Perinatal and maternal morbidity and mortality are composite outcomes. This is not an ideal solution because some components are clearly less severe than others. It is possible for one intervention to cause more deaths but less severe morbidity. However, in the context of labour induction at term this is unlikely. All these events will be rare, and a modest change in their incidence will be easier to detect if composite outcomes are presented. The incidence of individual components will be explored as secondary outcomes (see below).

Secondary outcomes relate to measures of effectiveness, complications and satisfaction:

Measures of effectiveness: (6) cervix unfavourable/unchanged after 12 to 24 hours; (7) oxytocin augmentation.

Complications: (8) uterine hyperstimulation without FHR changes; (9) uterine rupture; (10) epidural analgesia; (11) instrumental vaginal delivery; (12) meconium stained liquor; (13) Apgar score less than seven at five minutes; (14) neonatal intensive care unit admission; (15) neonatal encephalopathy; (16) perinatal death; (17) disability in childhood; (18) maternal side‐effects (all); (19) maternal nausea; (20) maternal vomiting; (21) maternal diarrhoea; (22) other maternal side‐effects; (23) postpartum haemorrhage (as defined by the trial authors); (24) serious maternal complications (e.g. intensive care unit admission, septicaemia but excluding uterine rupture); (25) maternal death.

Measures of satisfaction: (26) woman not satisfied; (27) caregiver not satisfied.

'Uterine rupture' includes all clinically significant ruptures of unscarred or scarred uteri. Trivial scar dehiscence noted incidentally at the time of surgery is excluded.

Additional outcomes may appear in individual primary reviews, but will not contribute to the secondary reviews.

While all the above outcomes were sought, only those with data appear in the analysis tables.

The terminology of uterine hyperstimulation is problematic (Curtis 1987). In the reviews we will use the term 'uterine hyperstimulation without FHR changes' to include uterine tachysystole (more than five contractions per 10 minutes for at least 20 minutes) and uterine hypersystole/hypertonus (a contraction lasting at least two minutes) and 'uterine hyperstimulation with FHR changes' to denote uterine hyperstimulation syndrome (tachysystole or hypersystole with FHR changes such as persistent decelerations, tachycardia or decreased short‐term variability). However due to varied reporting there is the possibility of subjective bias in interpretation of these outcomes. Also it is not always clear from trials if these outcomes are reported in a mutually exclusive manner.

Outcomes were included in the analysis: if reasonable measures were taken to minimise observer bias; and data were available for analysis according to original allocation.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group's Trials Register by contacting the Trials Search Co‐ordinator (June 2007).

The Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group's Trials Register is maintained by the Trials Search Co‐ordinator and contains trials identified from:

quarterly searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL);

monthly searches of MEDLINE;

handsearches of 30 journals and the proceedings of major conferences;

weekly current awareness search of a further 36 journals plus monthly BioMed Central email alerts.

Details of the search strategies for CENTRAL and MEDLINE, the list of handsearched journals and conference proceedings, and the list of journals reviewed via the current awareness service can be found in the 'Search strategies for identification of studies' section within the editorial information about the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group.

Trials identified through the searching activities described above are given a code (or codes) depending on the topic. The codes are linked to review topics. The Trials Search Co‐ordinator searches the register for each review using these codes rather than keywords. The initial search was performed simultaneously for all reviews of methods of inducing labour, as outlined in the generic protocol for these reviews (Hofmeyr 2000).

The reference lists of trial reports and reviews were searched by hand.

We did not apply any language restrictions.

Data collection and analysis

A strategy was developed to deal with the large volume and complexity of trial data relating to labour induction. Many methods have been studied, examining the effects of these methods when induction of labour was undertaken in a variety of clinical groups, e.g. restricted to primiparous women or those with ruptured membranes. Most trials are intervention‐driven, comparing two or more methods in various categories of women. Clinicians and parents need the data arranged according to the clinical characteristics of the women undergoing induction of labour, to be able to choose which method is best for a particular clinical scenario. To extract these data from several hundred trial reports in a single step would be very difficult. We developed a two‐stage method of data extraction. The initial data extraction was done in a series of primary reviews arranged by methods of induction of labour, following a standardised methodology. The data were then extracted from the primary reviews into a series of secondary reviews, arranged by the clinical characteristics of the women undergoing induction of labour.

To avoid duplication of data in the primary reviews, the labour induction methods were listed in a specific order, from one to 25. Each primary review included comparisons between one of the methods (from two to 25) with only those methods above it on the list. Thus, the review of intravenous oxytocin (4) included only comparisons with intracervical prostaglandins (3), vaginal prostaglandins (2) or placebo (1). Methods identified in the future will be added to the end of the list. The current list is as follows:

placebo/no treatment;

vaginal prostaglandins;

intracervical prostaglandins;

intravenous oxytocin;

amniotomy;

intravenous oxytocin with amniotomy;

vaginal misoprostol;

oral misoprostol;

mechanical methods including extra‐amniotic Foley catheter;

membrane sweeping;

extra‐amniotic prostaglandins;

intravenous prostaglandins;

oral prostaglandins;

mifepristone;

oestrogens;

corticosteroids;

relaxin;

hyaluronidase;

castor oil, bath, or enema, or both;

acupuncture;

breast stimulation;

sexual intercourse;

homoeopathic methods;

nitric oxide;

buccal or sublingual misoprostol;

hypnosis.

The primary reviews were analysed by the following subgroups:

previous caesarean section or not;

nulliparity or multiparity;

membranes intact or ruptured;

cervix favourable, unfavourable or undefined.

The secondary reviews will include all methods of labour induction for each of the categories of women for which subgroup analysis has been done in the primary reviews. There will thus be six secondary reviews, of methods of labour induction in the following groups of women:

nulliparous, intact membranes (unfavourable cervix, favourable cervix, cervix not defined);

nulliparous, ruptured membranes (unfavourable cervix, favourable cervix, cervix not defined);

multiparous, intact membranes (unfavourable cervix, favourable cervix, cervix not defined);

multiparous, ruptured membranes (unfavourable cervix, favourable cervix, cervix not defined);

previous caesarean section, intact membranes (unfavourable cervix, favourable cervix, cervix not defined);

previous caesarean section, ruptured membranes (unfavourable cervix, favourable cervix, cervix not defined).

Each time a primary review is updated with new data, those secondary reviews which include data which have changed, will also be updated.

The trials included in the primary reviews were extracted from an initial set of trials covering all interventions used in induction of labour (see above for details of search strategy). The data extraction process was conducted centrally. This was co‐ordinated from the Clinical Effectiveness Support Unit (CESU) at the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, UK, in co‐operation with the Pregnancy and Childbirth Group of The Cochrane Collaboration. This process allowed the data extraction process to be standardised across all the reviews.

The trials were initially reviewed on eligibility criteria, using a standardised form and the basic selection criteria specified above. Following this, data were extracted to a standardised data extraction form which was piloted for consistency and completeness. The pilot process involved the researchers at the CESU and previous review authors in the area of induction of labour.

Information was extracted regarding the methodological quality of trials on a number of levels. This process was completed without consideration of trial results. Assessment of selection bias examined the process involved in the generation of the random sequence and the method of allocation concealment separately. These were then judged as adequate or inadequate using the criteria described in Appendix 1 for the purpose of the reviews.

Performance bias was examined with regards to whom was blinded in the trials i.e. patient, caregiver, outcome assessor or analyst. In many trials the caregiver, assessor and analyst were the same party. Details of the feasibility and appropriateness of blinding at all levels was sought.

Individual outcome data were included in the analysis if they met the prestated criteria in 'Types of outcome measures'. Included trial data were processed as described in the Cochrane Reviewers' Handbook (Clarke 2000). Data extracted from the trials were analysed on an intention‐to‐treat basis (when this was not done in the original report, re‐analysis was performed if possible). Where data were missing, clarification is sought from the original authors. If the attrition was such that it might significantly affect the results, these data were excluded from the analysis. This decision rested with the reviewers of primary reviews and is clearly documented. If missing data become available, they will be included in the analyses.

Data were extracted from all eligible trials to examine how issues of quality influence effect size in a sensitivity analysis. In trials where reporting was poor, methodological issues were reported as unclear or clarification sought.

Due to the large number of trials, double data extraction was not feasible and agreement between the three data extractors was therefore assessed on a random sample of trials.

Once the data had been extracted, they were distributed to individual reviewers for entry onto the Review Manager computer software (RevMan 2000), checked for accuracy, and analysed as above using the Review Manager software. For dichotomous data, relative risks and 95% confidence intervals were calculated, and in the absence of heterogeneity, results were pooled using a fixed‐effect model.

The predefined criteria for sensitivity analysis included all aspects of quality assessment as mentioned above, including aspects of selection, performance and attrition bias.

Primary analysis was limited to the prespecified outcomes and sub‐group analyses. In the event of differences in unspecified outcomes or sub‐groups being found, these were analysed post hoc, but clearly identified as such to avoid drawing unjustified conclusions.

Results

Description of studies

We identified one study which included 28 women (Benvold 1987). The study assessed the impact of sexual intercourse with vaginal deposit of semen over a three night period compared with no intercourse. The studies main outcome was change in Bishops score, which was reported in a continuous format. The only extractable data in dichotomous format was Apgar less than seven at five minutes.

Risk of bias in included studies

The method of randomisation and concealment was unclear. The trial was single blind and the outcome assessor was unaware of the allocation when assessing the change in Bishops score.

Effects of interventions

Prespecified outcomes

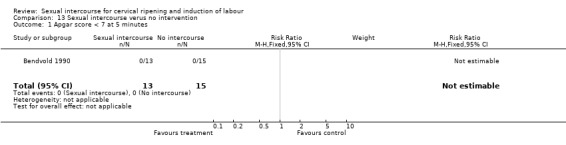

No data are reported for any of the prespecified primary outcomes. There was no difference between five‐minute Apgar score less than seven between the two groups (0% versus 0%).

Non‐prespecified outcomes

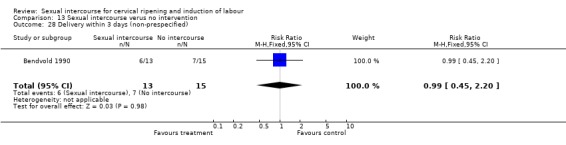

Bishops score between the two groups was not found to differ, with an average change in the coitus group of 1.0 and 0.5 in the control group (P > 0.05). There was no difference in the number of women who delivered within three days of the intervention (46% versus 47%, relative risk 0.99, 95% confidence interval 0.45 to 2.20).

Discussion

There are insufficient data at present to make any conclusions regarding the efficacy of sexual intercourse as a method of induction of labour.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

The role of sexual intercourse as a method of induction of labour is uncertain.

Implications for research.

Observational data suggest sexual intercourse may stimulate the onset of labour, and greater knowledge of this is an important issue to pregnant women and their partners. Non‐medical methods for inducing labour are of interest to women and to poorly resourced countries. There is a need for well‐designed randomised controlled trials to assess the impact of sexual intercourse on the onset of labour. Future trials investigating sexual intercourse as a method of induction need to be of sufficient power to detect clinically relevant differences in standard outcomes.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 24 April 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 2, 2000 Review first published: Issue 2, 2001

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 29 June 2007 | New search has been performed | Search updated. No new trials identified. |

| 1 March 2004 | New search has been performed | Search updated. No new trials identified. |

Acknowledgements

Claire Glenton for translating the Bendvold 1990 paper.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Methodological quality of trials

| Methodological item | Adequate | Inadequate |

| Generation of random sequence | Computer‐generated sequence, random‐number tables, lot drawing, coin tossing, shuffling cards, throwing dice. | Case number, date of birth, date of admission, alternation. |

| Concealment of allocation | Central randomisation, coded drug boxes, sequentially sealed opaque envelopes. | Open allocation sequence, any procedure based on inadequate generation. |

Data and analyses

Comparison 13. Sexual intercourse verus no intervention.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Apgar score < 7 at 5 minutes | 1 | 28 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 28 Delivery within 3 days (non‐prespecified) | 1 | 28 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.99 [0.45, 2.20] |

13.1. Analysis.

Comparison 13 Sexual intercourse verus no intervention, Outcome 1 Apgar score < 7 at 5 minutes.

13.28. Analysis.

Comparison 13 Sexual intercourse verus no intervention, Outcome 28 Delivery within 3 days (non‐prespecified).

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Bendvold 1990.

| Methods | Unclear method of randomisation and concealment. | |

| Participants | 28 term women (> 39 weeks' gestation). | |

| Interventions | The 'coitus' group were asked to have sexual

intercourse for 3 consecutive nights with vaginal semen deposit. The control group were asked to abstain from sexual intercourse for the same period. Both groups were asked to avoid nipple stimulation. A baseline Bishops score was taken and repeated after 3 days. |

|

| Outcomes | Change in Bishops score, Apgar scores. | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Contributions of authors

J Kavanagh and AJ Kelly performed the data extraction and analysis. J Kavanagh, AJ Kelly and J Thomas drafted the review.

Sources of support

Internal sources

Clinical Effectiveness Support Unit, Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, London, UK.

EPPI‐Centre, Social Science Research Unit, Institute of Education, UK.

External sources

No sources of support supplied

Declarations of interest

None known.

Edited (no change to conclusions)

References

References to studies included in this review

Bendvold 1990 {published data only}

- Bendvold E. Coitus and induction of labour [Samleie og induksjon av fodsel]. Tidsskrift for Jordmodre 1990;96:6‐8. [Google Scholar]

Additional references

Benvold 1987

- Benvold E, Gottlieb C, Svanborg K, Bygdeman M, Eneroth P. Concentration of prostaglandins in seminal fluid of fertile men. International Journal of Andrology 1987;10:463‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Clarke 2000

- Clarke M, Oxman AD, editors. Cochrane Reviewers' Handbook 4.1 (updated June 2000). In Review Manager (RevMan) [Computer program]. Version 4.1 Oxford, England: The Cochrane Collaboration, 2000.

Curtis 1987

- Curtis P, Evans S, Resnick J. Uterine hyperstimulation. The need for standard terminology. Journal of Reproductive Medicine 1987;32:91‐5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Hofmeyr 2000

- Hofmeyr GJ, Alfirevic Z, Kelly T, Kavanagh J, Thomas J, Brocklehurst P, et al. Methods for cervical ripening and labour induction in late pregnancy: generic protocol. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2000, Issue 2. [Art. No.: CD002074. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD002074] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

RevMan 2000 [Computer program]

- The Cochrane Collaboration. Review Manager (RevMan). Version 4.0 for Windows. Oxford, England: The Cochrane Collaboration, 2000.

Tan 2006

- Tan PC, Andi A, Azmi N, Noraihan MN. Effect of coitus at term on length of gestation, induction of labour, and mode of delivery. Obstetrics & Gynecology 2006;18:134‐40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Tomlinson 1999

- Tomlinson AJ, Colliver D, Nelson J, Jackson F. Does sexual intercourse at term influence the onset of labour? A survey of attitiudes of patients and their partners. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 1999;19:466‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]