Abstract

Background

For persons with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) the physical, personal, familial, social and vocational consequences are extensive. Occupational therapy (OT), with the aim to facilitate task performance and to decrease the consequences of rheumatoid arthritis for daily life activities, is considered to be a cornerstone in the management of rheumatoid arthritis. Till now the efficacy of occupational therapy for patients with rheumatoid arthritis on functional performance and social participation has not been systematically reviewed.

Objectives

To determine whether OT interventions (classified as comprehensive therapy, training of motor function, training of skills, instruction on joint protection and energy conservation, counseling, instruction about assistive devices and provision of splints) for rheumatoid arthritis patients improve outcome on functional ability, social participation and/or health related quality of life.

Search methods

Relevant full length articles were identified by electronic searches in Medline, Cinahl, Embase, Amed, Scisearch and the Cochrane Musculoskeletal group Specialised Register. The reference list of identified studies and reviews were examined for additional references. Date of last search: December 2002.

Selection criteria

Controlled (randomized and non‐randomized) and other than controlled studies (OD) addressing OT for RA patients were eligible for inclusion.

Data collection and analysis

The methodological quality of the included trials was independently assessed by two reviewers. Disagreements were resolved by discussion. A list proposed by Van Tulder et al. () was used to assess the methodological quality. For outcome measures, standardized mean differences were calculated. The results were analysed using a best evidence synthesis based on type of design, methodological quality and the significant findings of outcome and/or process measures.

Main results

Thirty‐eight out of 58 identified occupational therapy studies fulfilled all inclusion criteria. Six controlled studies had a high methodological quality. Given the methodological constraints of uncontrolled studies, nine of these studies were judged to be of sufficient methodological quality. The results of the best evidence synthesis shows that there is strong evidence for the efficacy of "instruction on joint protection" (an absolute benefit of 17.5 to 22.5, relative benefit of 100%) and that limited evidence exists for comprehensive occupational therapy in improving functional ability (an absolute benefit of 8.7, relative benefit of 20%). Indicative findings for evidence that "provision of splints" decreases pain are found (absolute benefit of 1.0, relative benefit of 19%).

Authors' conclusions

There is evidence that occupational therapy has a positive effect on functional ability in patients with rheumatoid arthritis.

Plain language summary

Occupational therapy for rheumatoid arthritis

Does occupational therapy help people with rheumatoid arthritis? To answer this question, scientists analysed 38 studies. The studies tested over 1700 people who had rheumatoid arthritis. People were either counseled, trained in skills or trained to move or do daily chores with less pain, taught to protect their joints, given splints, taught to use assistive devices, or had no therapy. Not all studies were high quality but this Cochrane Review provides the best evidence about occupational therapy that we have today.

What is occupational therapy and how could it help rheumatoid arthritis? Rheumatoid arthritis is a disease in which the body's immune system attacks its own healthy tissues. The attack happens mostly in the joints of the feet and hands and causes redness, pain, swelling and heat around the joint. People with rheumatoid arthritis can find it difficult to do daily chores such as dressing, cooking, cleaning and working. Occupational therapists can give advice on how to do every day activities with less pain or advice on how to use splints and assistive devices.

How well does it work? A high quality study showed that people could do daily chores better after having occupational therapy with training, advice and counseling. Two high quality studies showed that people given advice about how to protect their joints could do daily chores better than people with no advice or another type of occupational therapy. But both therapies did not help overall well‐being or pain.

Another high quality study showed that people trained to move or do daily activities could move just as well as and with the same amount of pain as people who did not have occupational therapy. The strength of their grip was also improved immediately after wearing a splint. But hand movement was less after wearing a splint

There was not enough information to say whether advice about using assistive devices is helpful.

What is the bottom line? There is "gold" level evidence that occupational therapy can help people with rheumatoid arthritis to do daily chores such as dressing, cooking and cleaning and with less pain. Benefits are seen with occupational therapy that includes training, advice and counseling and also with advice on joint protection.

Splints can decrease pain and improve the strength of one's grip, but it may decrease hand movement.

Background

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) patients show a reduction in physical capacities compared to healthy persons. Symptoms such as pain, fatigue, stiffness and decreased muscle strength cause difficulties with daily activities like grooming and dressing, cooking a meal, cleaning, shopping, work‐ and leisure activities. The physical, personal, familial, social and vocational consequences of rheumatoid arthritis are extensive. Occupational therapy (OT) is concerned with facilitating people in performing their daily living activities, and in overcoming barriers by maintaining or improving abilities or to compensate for decreased ability in the performance of occupations (Lindquist 1999). The most important interventions in occupational therapy are training of skills, counseling, education of joint protection skills, prescription of assistive devices and the provision of splints (Melvin 1998). Advice/instruction in the use of assistive devices, training of self care activities and productivity activities are the three most often chosen interventions by occupational therapists for rheumatoid arthritis patients (Driessen 1997). Till now, the evidence on the effects of occupational therapy for patients with rheumatoid arthritis on functional performance and social participation has not been reviewed systematically. So far, one narrative review (Clarke 1999) discussed the effectiveness of splinting, joint protection, and provision of aids/equipment for several rheumatic diseases on basis of the results of only a few studies on occupational therapy. One Cochrane review (Egan 2003) addresses the efficacy of splints and orthosis for RA patients, evaluating only a small part of OT interventions. Therefore, we conducted a systematic review of published studies evaluating occupational therapy for rheumatoid arthritis

Objectives

To determine whether OT interventions for RA patients improve outcome on functional ability, social participation and/or health related quality of life.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Studies with one of the following designs have been entered in the review. 1) Randomised controlled clinical trial (RCT): An experiment in which investigators randomly allocate eligible people into treatment and control groups. Cross‐over trials were considered as RCTs according to the Cochrane Collaboration Guidelines (Clarke 2003). 2) Controlled clinical trial (CCT): an experiment in which eligible people are in a non‐randomized way allocated to the treatment and the control groups. 3) Other than controlled designs (OD): patient series and pre‐post studies. Such ODs can only contribute in a limited way to the best evidence synthesis.

Types of participants

Studies with patients who fulfil a clinical diagnosis (as described by the authors of the studies) of rheumatoid arthritis have been included.

Types of interventions

In rheumatoid arthritis occupational therapy can include a variety of interventions. OT interventions were either regarded as "comprehensive OT" (when all six intervention categories were part of the evaluated OT treatment) or were classified into six specific intervention categories: 1) training of motor function; 2) training of skills; 3) instruction on joint protection; 4) counseling; 5) advice and instruction in the use of assistive devices; and 6) provision of splints. All studies with interventions as above specified according to a group of four experienced occupational therapists and reviewer CHME (see: Methods of the review) were eligible for inclusion in this review. All studies with a multi‐disciplinary intervention were excluded.

Types of outcome measures

Studies that used one or more of the following outcome measures have been included:

Primary outcome measures: pain, fatigue, functional abilities (including dexterity), physical independence, quality of life (including well‐being and depression). Information about the used outcome scales can be found in the clinical relevance tables. Table 5, Table 6, Table 7

1. Clinical relevance Table: Pain at follow up.

| Intervention | Study | Treatment group | Outcome scale | N of patients | Baseline mean | End of study | Absolute benefit | Relative benefit |

| Comprehensive OT | Helewa 1991 | individual OT | VAS (0‐100) | 52 | 51.6 | 49.8 | ‐5.6 | ‐10% |

| waiting list | 50 | 56 | 55.4 | |||||

| Kraaimaat 1995 | group OT | IRGL | 28 | 16.6 | 15.4 | 0.8 | 5% | |

| waiting list | 19 | 16.6 | 14.6 | |||||

| Training of motor function | Dellhag 1992 | wax bath + exercise | VAS (0‐100) | 13 | 29.3 | 22.1 | ‐11 | ‐39% |

| no treatment | 13 | 27.7 | 33.1 | |||||

| Hoenig 1993 | tendon gliding exercise and therapy putty | articular index (painful joints) | 10 | 9.9 | 10.1 | ‐6.5 | ‐55% | |

| no intervention | 11 | 13.5 | 16.6 | |||||

| Joint protection | Hammond 1999 | group intervention | VAS (0‐100) | 17 | 41.0 | 37.0 | 9 | 25% |

| no intervention | 18 | 30.0 | 28.0 | |||||

| Hammond 2001 | group instruction | VAS (0‐100) | 65 | 39.3 | 34.7 | ‐4.8 | ‐12% | |

| multi disciplinary group instruction | 62 | 42.7 | 39.5 | |||||

| Neuberger 1993 | self instruction + practice | VAS (0‐10) | 14 | 5.6 | 4.1 | ‐0.9 | ‐17% | |

| no intervention | 11 | 4.6 | 5.0 | |||||

| Assistive devices | Hass 1997 | special selection proces | FSI | 25 | 2.0 | 1.9 | 0.2 | 10% |

| routine care | 16 | 1.8 | 1.7 | |||||

| Splints | Ter Schegget 2000 | SRS splint | VAS (0‐10) | 9 | 2.7 | 2.7 | 0.7 | 36% |

| custom made splint | 9 | 1.1 | 2.0 | |||||

| Tijhuis 1998 | Thermo lynn orthosis | VAS (0‐10) | 10 | 5.4 | 4.7 | 1.0 | 19% | |

| Futuro orthosis | 10 | 5.4 | 3.7 |

2. Clinical relevance Table: Functional ability at follow up.

| Intervention | Study | Treatment group | Outcome (scale) | N of patients | Baseline mean | End of study | absolute benefit | Relative benefit |

| Comprehensive OT | Helewa 1991 | individual OT | questionaire | 52 | 42.8 | 52.2 | 8.7 | 20% |

| waiting list | 50 | 42.3 | 43.5 | |||||

| Kraaimaat 1995 | group OT | IRGL self care | 28 | 25.4 | 24.5 | ‐1.7 | ‐6% | |

| waiting list | 19 | 25.9 | 26.2 | |||||

| Training of motor function | Dellhag 1992 | wax bath + exercise | Sollermantest (dexterity) | 13 | 72.3 | 74.8 | ‐0.2 | 0% |

| no treatment | 13 | 75.2 | 75.0 | |||||

| Hoenig 1993 | tendon gliding exercise and therapy putty | 9 hole peg test (derxterity) | 10 | 26.4 | 28.8 | 3.8 | 15% | |

| no intervention | 11 | 24.3 | 25.0 | |||||

| Joint protection | Furst 1987 | group treatment | HAQ | 18 | 1.7 | 1.8 | 0.1 | 6% |

| self instruction + practice | 10 | 1.4 | 1.7 | |||||

| Hammond 1999 | group intervention | JPBA observation | 17 | 15.0 | 32.5 | 22.5 | 187% | |

| no intervention | 18 | 8.8 | 10.0 | |||||

| Hammond 2001 | group OT instruction | JPBA observation | 65 | 16.2 | 35.5 | 17.5 | 112% | |

| routine treatment | 62 | 15.0 | 18.0 | |||||

| Neuberger 1993 | self instruction + practice | observation | 13 | 2.7 | 5.2 | 1.8 | 66% | |

| no intervention | 14 | 2.7 | 3.4 | |||||

| Assistive devices | Hass 1997 | special selection process | FSI | 25 | 1.4 | 1.6 | 0.3 | 23% |

| routine care | 16 | 1.2 | 1.3 | |||||

3. Clinical relevance Table: Quality of life and participation at follow‐up.

| Intervention | study | Treatment group | Outcome scale | N of patients | Baseline mean | End of study | Absolute benefit | Relative benefit |

| Comprehensive OT | Helewa 1991 | individual OT | Beck scale (depression) | 50 | 13.1 | 11.1 | ‐0.1 | ‐1% |

| waiting list | 46 | 12.4 | 11.2 | |||||

| Kraaimaat 1995 | group OT | IRGL (depression) | 28 | 3.4 | 2.2 | ‐0.3 | ‐9% | |

| waiting list | 19 | 3.2 | 2.5 | |||||

| Joint protection | Furst 1987 | group treatment | PAIS | 18 | 43.2 | 44.7 | 6.5 | 15% |

| self instruction + practice | 10 | 39.4 | 38.2 | |||||

| Hammond 2001 | group instruction | AIMS2 | 65 | 3.4 | 3.2 | 0.1 | 2% | |

| routine instruction | 62 | 3.4 | 3.1 | |||||

| Neuberger 1993 | self instruction + practice | CES‐D (depression | 13 | 12.5 | 12.8 | 0.8 | 5% | |

| no intervention | 14 | 14.5 | 12.0 | |||||

| Assistive devices | Hass | special selection process | SIP | 29 | 11.4 | 8.0 | 2.1 | 21% |

| routine care | 18 | 6.6 | 5.9 |

Secondary process measures (process measures are considered to be indicators of a successful treatment): knowledge about disease management, compliance, self‐efficacy, range of motion, muscle strength

Search methods for identification of studies

Only full length articles or full written reports have been considered for inclusion in the review. The following procedures were used to identify trials: 1. A broad computerized search strategy for identifying RCTs, CCTs and OD was used built upon the following components:

a) search strategy for controlled trials (RCTs, CCTs) as recommended by the Cochrane Collaboration (Dickersin 1994): see Appendix 1. b) search strategy for OD: see Appendix 2. c) Search strategy for rheumatoid arthritis: see Appendix 3. d) Search strategy for occupational therapy interventions: see Appendix 4.

The following databases were searched: a) MEDLINE (1966 until December 2002) b) CINAHL (1982 until December 2002) c) Embase (1974 until December 2002) d) SCISEARCH (1974 until December 2002) e) Cochrane Controlled Trials Register (issue 4 2002) f) The databases of the libraries of medical and rehabilitation literature of two Dutch institutes (NPI / Nivel) g) The database of the Rehabilitation and Related Therapies (RRT) Field of the Cochrane Collaboration h) The specialized trial's register of the Cochrane Musculoskeletal Group

The search strategy has been formulated in WinSpirs (Medline, Cinahl) and was adapted by an experienced medical librarian to make it applicable for the other databases. 2) The same databases were searched to identify reviews about the efficacy of occupational therapy 3) The reference lists of the identified studies and reviews were scanned. 4) Authors of papers reporting trials about the efficacy of OT in RA were contacted by mail and asked for any published of unpublished studies relevant for this systematic review. A list with so far identified trials was enclosed. 5) Authors of abstracts were asked for a full written report.

Data collection and analysis

Selection for inclusion in the review, assessment of the methodological quality and data extraction have been performed in three separate steps. Three reviewers (CHME, EMJS, MAKM) did take part in these procedures. Prior to all three steps assessment procedures were tested in a sample of three articles by two reviewers. A standard form for each step was made.

Selection for inclusion Because of the broad search strategy we expected to find a large number of non relevant articles. The procedure for inclusion of the studies was based on the recommendations by Van Tulder et al (Van Tulder 1997): The first selection, based on titles and abstracts, was independently performed by two reviewers (EMJS and CHME) considering the criteria for 'type of study', 'type of participants' and 'type of outcome measures'. This first selection could result in inclusion of the study, exclusion of the study, or could be indecisive. Disagreements between the two reviewers was discussed. If the first selection was indecisive or if disagreement persisted, a final decision on inclusion has been based on the full article. The second step for inclusion was independently done by two reviewers (EMJS and MAKM), using full reports and considering the criteria stated above. Disagreements regarding inclusion status has been resolved by discussion. If no consensus was met a third reviewer (CHME) decided. Finally, a group of four occupational therapists and reviewer CHME did assess the criteria for 'types for intervention' and if appropriate classify the type of intervention into one of the six different interventions or combinations of interventions. Consensus has been reached by discussion.

Assessment of methodological quality The variety in study designs included in this systematic review necessitated the use of different quality assessment tools. The methodological quality of RCTs and CCTs was rated by a list recommended by Van Tulder (Van Tulder 1997). The list, containing specified criteria proposed by Jadad (Jadad 1996) and Verhagen et al (Verhagen 1998) consists of 11 criteria for internal validity, 6 descriptive criteria and 2 statistical criteria (Appendix 1). One modification was made in the specification of the criterion 'eligibility': the 'condition of interest' (the impairment or disability that indicated referral to occupational therapy) was added as an eligibility criterion, as proposed by Wells (Wells 2000). All criteria are scored as yes, no, or unclear. Studies were considered to be of 'high quality' if at least six criteria for internal validity, three descriptive criteria and one statistical criterion were scored positively.

The methodological quality of the other designs (ODs) has been rated using an adapted version of the Van Tulder list (Appendix 5). Some items (concerning randomization, similarity of patient groups, blinding of care provider, blinding of patient) were considered inapplicable to ODs and removed from the list. Some items were reformulated to make them applicable to one patient group (for instance: "were co‐interventions avoided or comparable?' was reformulated into "were co‐interventions avoided?") or to make the item applicable for the design of the study (for instance: "was the outcome assessor blinded to the intervention" was reformulated into: "was the care‐provider not involved in the outcome assessment?"). The final list of criteria used in ODs consists of seven criteria for internal validity, four descriptive criteria and two statistical criteria (Appendix 5). All criteria were scored as yes, no, or unclear. Studies were considered to be of 'sufficient quality' if at least four out of seven criteria for internal validity, two descriptive criteria and one statistical criterion were scored positively. The methodological quality of the included trials was independently assessed by two reviewers (EMJS, MAHK). Disagreements were resolved by discussion. If no consensus was met a third reviewer (CHME) decided.

Data extraction The following information was systematically extracted by EMJS 1. Study characteristics: number of participating patients, specified criteria for diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis, in and exclusion criteria, type of experimental and control interventions, co‐interventions, features of interventions (duration, frequency, setting), number of drop‐outs. 2. Patient characteristics: type of disease, sex, age, disease duration, disease severity. 3. Outcome and process measures assessed immediately after finishing the intervention, within six months follow up and after six or more months follow up: Continuous variables: baseline values (mean and standard deviation), standardized mean difference with corresponding 95% confidence interval. Dichotomous variables: odds ratio with corresponding 95% confidence interval

Analysis of the results: In this review seven different intervention categories were distinguished: 1) Comprehensive OT, 2) training of motor function, 3) training of skills, 4) instruction on joint protection, 5) counseling, 6) advice / instruction assistive devices, and 7) provision of splints. Analyses were performed separately for each intervention category.

The results of each study were plotted, if possible, as point estimates, i.e., odds ratio with corresponding 95% confidence interval for dichotomous outcomes and standardized mean differences with corresponding 95% confidence interval for continuous outcomes.

We expected to find too much clinical heterogeneity among the studies with regard to patients (severity of the disease), interventions (duration, frequency and setting) and outcome measures (diversity, presentation of the results) to make quantitative analysis (meta‐analysis) appropriate. Instead, we performed a best evidence synthesis by attributing various levels of evidence to the efficacy of OT, taking into account the design of the studies, the methodological quality and the outcome of the original studies. The best‐evidence synthesis (Appendix 6) is based upon the one proposed by Van Tulder (Van Tulder 2003) and was adapted for the purpose of this review.

Additional tables Continuous outcomes results are presented in tables showing the absolute benefit and the relative difference in the change from baseline. Absolute benefit is calculated as the improvement in the treatment group less the improvement in the control group, in the original units. Relative difference in the change from baseline is calculated as the absolute benefit divided by the baseline mean (control group). The relative difference in change is used to provide clinically meaningful information about expected improvement relative to the placebo or untreated group with each intervention. Results from individual trials are presented separately allowing the comparison of the percentage improvement in each trial or combined.

Sensitivity analyses were performed by attributing different levels of quality to the studies: 1) results were re‐analysed excluding low quality studies. 2) results were re‐analysed considering studies to be of "high quality" if 4 or more criteria of internal validity are met. 3) results were re‐analysed excluding studies not reporting on the ACR criteria for diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis (Arnett 1988)

Grading the strength of the evidence The common system of grading the strength of scientific evidence for a therapeutic agent that is described in the CMSG module scope and in the Evidence‐based Rheumatology BMJ book (Tugwell 2003) was used to rank the evidence included in this systematic review. Four categories are used to rank the evidence from research studies from highest to lowest quality: Platinum, Gold, Silver, and Bronze. The ranking is included in the synopsis of this review.

Results

Description of studies

The search strategy resulted in a list of 2694 citations. After selection on title and abstract 155 full articles were obtained. Fifty‐nine publications concerned the efficacy of OT for RA, of which 43 articles, presenting 38 studies, fulfilled all inclusion criteria (16 RCTs, 6 CCTs, 16 ODs) (see characteristics of included studies). Data from four studies were presented in more than one article (Kraaimaat 1995, Huiskes 1991; van Deusen 1987a, van Deusen 1987b, van Deusen 1988; Furst 1987, Gerber 1987, Stern 1996a, Stern 1996b, Stern 1997) . One publication (Neuberger 1993) presented two studies. Fifteen studies (Alderson 1999, Brattström 1970, Chen 1999, Cytowicz 1999, Gault 1969, Karten 1973, Kjeken 1995, Löfkvist 1988, Maggs 1996, Mann 1995, Nicholas 1982, Schulte 1994, Stern 1994, Stern 1996c, Stewart 1990) were excluded: because treatment contrast was a multi disciplinary intervention, because also patients with other rheumatic diseases participated in the study, or because outcome measures were beyond the scope of our review (see characteristics of excluded studies).

Four studies (3 RCTs, Helewa 1991(compared to no treatment), Kraaimaat 1995 (compared to no treatment), Mowat 1980 (compared to alternative treatment)) and 1 OD, McAlphine 1991) evaluated COMPREHENSIVE OCCUPATIONAL THERAPY involving 343 RA patients.

Six RCTs/CCTs (Brighton 1993 (compared to no treatment), Dellhag 1992 (compared to no treatment), van Deusen 1987a (compared to alternative treatment), Hoenig 1993 (Compared to no treatment), Ring 1998 (Compared to alternative treatment), Wagoner 1981(compared to alternative treatment)) and 1 OD (Schaufler 1978) evaluated a TRAINING OF MOTOR FUNCTION intervention involving 258 RA patients.

Five RCTs/CCTs (Furst 1987 (compared to alternative treatment), Hammond 1999a (compared to no treatment), Hammond 2001 (compared to alternative treatment), Neuberger 1993 (two studies, compared to no intervention)) and 4 ODs (Barry 1994, Cartlidge 1984, Hammond 1994, Hammond 1999b) looked at the efficacy of an INSTRUCTION ON JOINT PROTECTION AND ENERGY CONSERVATION programme involving 370 RA patients.

One CCT (Hass 1997 (compared to alternative treatment)) and 1 OD (Nordenskiöld 1994) evaluated the intervention ADVICE/INSTRUCTION IN THE USE OF ASSISTIVE DEVICES involving 212 RA patients.

Sixteen studies focussed on the intervention PROVISION OF SPLINTS involving 606 RA patients. The designs of these studies were seven RCTs / CCTs (Stern 1996a, Ter Schegget 2000, Tijhuis 1998, Anderson 1987, Callinan 1995, Feinberg 1992, Palchik 1990) and nine ODs (McKnight 1982, Nordenskiöld 1990, Pagnotta 1998, Rennie 1996, Agnew 1995, Feinberg 1981, Malcus 1992, McKnight 1992, Spoorenberg 1994). Within these 16 studies six different types of splints were evaluated (working splint, resting splint, three types of anti‐deformity splints, air‐pressure splint). Four RCTs/CCTs (Stern 1996a, Ter Schegget 2000, Tijhuis 1998, Feinberg 1992) compared two splints with each other. Three RCTs/CCTs (Anderson 1987, Callinan 1995, Palchik 1990) compared splint treatment with a non treated control group.

No studies were identified concerning the interventions TRAINING OF SKILLS and COUNSELING.

Risk of bias in included studies

The methodological quality was assessed in 22 RCTs / CCTs and 16 ODs (Table 8). Six RCTs (Hammond 1999a, Hammond 2001, Helewa 1991, Hoenig 1993, Ter Schegget 2000, Tijhuis 1998) had a high methodological quality. All CCTs scored a low methodological quality. In particular, the following criteria were fulfilled in less than one third of the RCTs/CCTs: 'Adequate allocation concealment', 'blinded care provider', 'blinding of patients', 'information on co‐interventions', 'blinded outcome assessor', 'intention to treat analysis' and 'long term follow up'. Given the methodological constraints of other designs, nine ODs (Barry 1994, Cartlidge 1984, Hammond 1994, Hammond 1999b, McKnight 1982, Nordenskiöld 1990, Nordenskiöld 1994, Pagnotta 1998, Rennie 1996) had a sufficient methodological quality. The following criteria were fulfilled in one third or less of the OD studies: 'outcome assessor not involved in treatment' and 'long term follow up'.

4. Assessed methodological quality for RCT's, CCT's and OD's.

| Study design | Study ID | Internal validity | Descriptive | Statistical | total score | meth. quality |

| RCT | Anderson 1987 | b1, f, g, n (see appendix 1 for items) | c, d, m1(see appendix 1 for items) | o, q (see appendix 1 for items) | 4, 3, 2 | low |

| RCT | Brighton 1993 | b1, g, i, n (see appendix 1 for items) | d, m1 (see appendix 1 for items) | o (see appendix 1 for items) | 4, 2, 1 | low |

| RCT | Callinan 1995 | b1, g, j, l, n (see appendix 1 for items) | a, d, k, m1 (see appendix 1 for items) | o (see appendix 1 for items) | 5, 4, 1 | low |

| RCT | Hammond 1999a | b1, g, i, j, n, p (see appendix 1 for items) | a, c, d, k, m1 (see appendix 1 for items) | o, q (see appendix 1 for items) | 6, 5, 2 | high |

| RCT | Hammond 2001 | b1, b2, g, i, j, l, n, p (see appendix 1 for items) | a, c, d, m1, m2 (see appendix 1 for items) | o, q (see appendix 1 for items) | 8, 5, 2 | high |

| RCT | Helewa 1991 | b1, e, f, i, j, l, n, p (see appendix 1 for items) | a, c, d, m1 (see appendix 1 for items) | o, q (see appendix 1 for items) | 8, 4, 2 | high |

| RCT | Hoenig 1993 | b1, e, f, g, i, j, n (see appendix 1 for items) | c, d, k, m1 (see appendix 1 for items) | o (see appendix 1 for items) | 7, 4, 1 | high |

| RCT | Kraaimaat 1995 | b1, g, j, l, n (see appendix 1 for items) | c, d, m1, m2 (see appendix 1 for items) | o, q (see appendix 1 for items) | 5, 4, 2 | low |

| RCT | Mowat 1980 | b1, f, i, j, l, n (see appendix 1 for items) | a, c, d, m1, m2 (see appendix 1 for items) | ‐ | 6, 5, 0 | low |

| RCT | Neuberger 1993p | b1, j (see appendix 1 for items) | d, m1 (see appendix 1 for items) | o (see appendix 1 for items) | 2, 2, 1 | low |

| RCT | Palchik 1990 | b1, l (see appendix 1 for items) | a, k, m1 (see appendix 1 for items) | o (see appendix 1 for items) | 2, 3, 1 | low |

| RCT | Stern 1996a | b1, g, j (see appendix 1 for items) | a, c, d, k, m1 (see appendix 1 for items) | o, q (see appendix 1 for items) | 3, 5, 2 | low |

| RCT | Ter Schegget 1997 | b1, g, j, l, n, p (see appendix 1 for items) | d, k, m1 (see appendix 1 for items) | o, q (see appendix 1 for items) | 6, 3, 2 | high |

| RCT | Tijhuis 1998 | b1, g, j, l, n, p (see appendix 1 for items) | a, c, d, k, m1 (see appendix 1 for items) | o, q (see appendix 1 for items) | 6, 5, 2 | high |

| RCT | Van Deusen 1987a | b1, l, n (see appendix 1 for items) | m1, m2 (see appendix 1 for items) | o (see appendix 1 for items) | 3, 2, 1 | low |

| RCT | Wagoner 1981 | b1, g, j, l, n (see appendix 1 for items) | d, m1 (see appendix 1 for items) | o (see appendix 1 for items) | 5, 2, 1 | low |

| CCT | Dellhag 1992 | f, j, n (see appendix 1 for items) | c, d, m1 (see appendix 1 for items) | ‐ | 3, 3, 0 | low |

| CCT | Feinberg 1992 | h, j, l, n (see appendix 1 for items) | a, c, d, m1 (see appendix 1 for items) | o, q (see appendix 1 for items) | 4, 4, 2 | low |

| CCT | Furst 1987 | j, n, p (see appendix 1 for items) | a, c, d, m1, m2 (see appendix 1 for items) | o,q (see appendix 1 for items) | 3, 5, 2 | low |

| CCT | Hass 1997 | j (see appendix 1 for items) | d, m2 (see appendix 1 for items) | o (see appendix 1 for items) | 1, 2, 1 | low |

| CCT | Neuberger 1993f | j (see appendix 1 for items) | c, d, m1 (see appendix 1 for items) | o, q (see appendix 1 for items) | 1, 3, 2 | low |

| CCT | Ring 1998 | i, l (see appendix 1 for items) | d, k, m1 (see appendix 1 for items) | o, q (see appendix 1 for items) | 2, 3, 2 | low |

| OD | Agnew 1995 | l, p (see appendix 1 for items) | k, m2 (see appendix 1 for items) | o, q (see appendix 1 for items) | 2, 2, 2 | low |

| OD | Barry 1994 | g, i, l, n (see appendix 1 for items) | m1, m2 (see appendix 1 for items) | o, q (see appendix 1 for items) | 4, 2, 2 | high |

| OD | Cartlidge 1984 | f, j, l, n, p (see appendix 1 for items) | a, d, m1 (see appendix 1 for items) | o (see appendix 1 for items) | 5, 3, 1 | high |

| OD | Feinberg 1981 | j (see appendix 1 for items) | a, d, k, m2 (see appendix 1 for items) | o (see appendix 1 for items) | 1, 4, 1 | low |

| OD | Hammond 1994 | g, i, j, l, n (see appendix 1 for items) | a, d, m1 (see appendix 1 for items) | o, q (see appendix 1 for items) | 5, 3, 2 | high |

| OD | Hammond 1999b | g, j, l, n (see appendix 1 for items) | a, d, m1 (see appendix 1 for items) | o, q (see appendix 1 for items) | 4, 3, 2 | high |

| OD | Malcus 1992 | f, j, l (see appendix 1 for items) | a, d, k, m1 (see appendix 1 for items) | o (see appendix 1 for items) | 3, 4, 1 | low |

| OD | McAlphine 1991 | j, n (see appendix 1 for items) | m1 (see appendix 1 for items) | o, q (see appendix 1 for items) | 2, 1, 2 | low |

| OD | McNight 1982 | f, j, l, n (see appendix 1 for items) | a, d, k, m1 (see appendix 1 for items) | o (see appendix 1 for items) | 4, 4, 1 | high |

| OD | McNight 1992 | f, j, n (see appendix 1 for items) | a, d, k, m1 (see appendix 1 for items) | o, q (see appendix 1 for items) | 3, 4, 2 | low |

| OD | Nordenskiold 1990 | f, g, j, l, n, p (see appendix 1 for items) | d, m1 (see appendix 1 for items) | o (see appendix 1 for items) | 6, 2, 2 | high |

| OD | Nordenskiold 1994 | f, g, j, n (see appendix 1 for items) | d, m1 (see appendix 1 for items) | o (see appendix 1 for items) | 4, 2, 1 | high |

| OD | Pagnotta 1998 | f, g, j, l, n, p (see appendix 1 for items) | a, d, k, m1 (see appendix 1 for items) | o, q (see appendix 1 for items) | 6, 4, 2 | high |

| OD | Rennie 1996 | g, j, l, n, p (see appendix 1 for items) | d, m1 (see appendix 1 for items) | o, q (see appendix 1 for items) | 5, 2, 2 | high |

| OD | Schaufler 1978 | j, n, p (see appendix 1 for items) | d, m1 (see appendix 1 for items) | o (see appendix 1 for items) | 3, 2, 1 | low |

| OD | Spoorenberg 1994 | j (see appendix 1 for items) | a, d, k (see appendix 1 for items) | o, q (see appendix 1 for items) | 1, 3, 2 | low |

Effects of interventions

Table 5, Table 6, Table 7 show the relative benefit on Pain, Functional ability and Participation

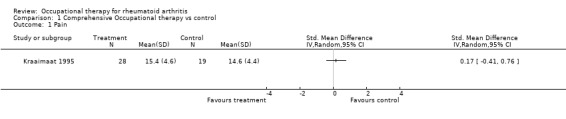

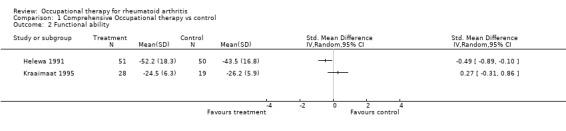

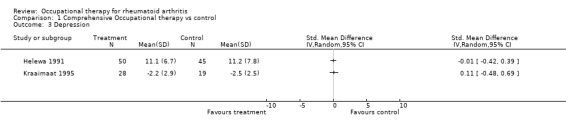

Two RCTs (Helewa 1991, Kraaimaat 1995) comparing COMPREHENSIVE OCCUPATIONAL THERAPY with no treatment measured pain. No statistically significant result were found within 6 to 10 weeks. The relative difference for the outcome pain between those who received OT treatment and those who were on the waiting list ranged from ‐10% to 5%. Helewa 1991(high quality RCT) reported a statistically significant positive effect on functional ability whereas Kraaimaat 1995 (low quality RCT) showed non significant results. The relative difference for functional ability ranged from ‐6% to 20%. Also no significant results were found in these two studies on the outcome measure depression. The relative difference ranged from ‐9% to ‐1%. Mowat 1980 and McAlphine 1991 presented insufficient data to calculate effect sizes. Both low quality studies reported non‐significant results on functional ability. The process measure knowledge was assessed in one study (Mowat 1980) with a follow up of one year. It reported no difference in gain in knowledge between the intervention and the control group who received alternative treatment. No safety/side effects were assessed in any of the included studies. Thus, on the basis of one RCT (Helewa 1991) there is limited evidence for the efficacy of comprehensive OT on functional ability. No evidence is found for the efficacy of comprehensive OT on the other outcome and process measures.

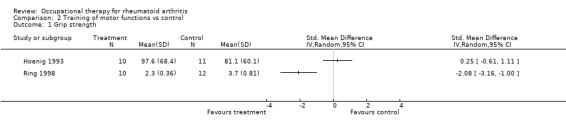

TRAINING OF MOTOR FUNCTION was compared to either no treatment (Brighton 1993, Dellhag 1992, Hoenig 1993) or alternative treatment (Ring 1998, van Deusen 1987a, Wagoner 1981). The outcome measures pain and functional ability were assessed in two (Hoenig 1993, Dellhag 1992) and three (Hoenig 1993, Dellhag 1992, Schaufler 1978) studies, respectively at 3 months, 4 weeks and 4 months. All these studies reported insufficient data to calculate effect sizes. The RCT with a high methodological quality (Hoenig 1993) reported no significant differences between groups on pain and functional ability after training of hand function. The low quality RCT (Dellhag 1992) presented significant results on pain but not on functional ability. For the outcome of pain the relative difference between treated groups ranged from ‐55% to ‐39%. The relative difference for functional ability ranged from 0% to 15%. All studies measured one or two process measures: compliance (van Deusen 1987a, Wagoner 1981), grip strength (Hoenig 1993, Dellhag 1992,Ring 1998, Schaufler 1978) and/or range of motion (van Deusen 1987a, Hoenig 1993, Brighton 1993, Dellhag 1992, Ring 1998, Schaufler 1978). On compliance no significant results were found. The high quality RCT (Hoenig 1993) reported no significant differences in grip strength between groups, whereas the low quality RCT (Brighton 1993), the low quality CCT (Ring 1998) and the low quality OD (Schaufler 1978) did report significant changes in grip strength after training of hand function measured after respectively 4 years, 6 months and 4 months. The relative difference on grip strength for those that received training of motor function and those that did not ranged from ‐40% to 76% (Table 9). The high quality RCT (Hoenig 1993) and one low quality RCT (Brighton 1993) presented non significant results on range of motion. Two low quality RCTs (Dellhag 1992, van Deusen 1987a) and one low quality CCT (Ring 1998) showed significant effect sizes who were derived from significance tests (calculation of standardized mean difference (hedges' g) based on p, F, or t‐ value). The relative difference between the experimental and control group ranged from ‐55% to 8% (Table 10). Two studies assessed safety/side effects (Hoenig 1993, Ring 1998). Hoenig 1993 reported problems with the upper extremities in the patient groups that performed resistance exercises. Ring 1998 reported that the continuos passive motion machine was experienced by some patients as heavy weighted, uncomfortable and fatigue inducing. Thus, On basis of the high methodological quality RCT (Hoenig 1993) there is no evidence for the effectiveness of training of motor function on both outcome and process measures.

5. Clinical relevance Table: Training of motor functions; grip strength.

| Study | Treatment group | Outcome scale | N of patients | Baseline mean | End of study | Absolute benefit | Relative benefit |

| Brighton 1993 | Daily hand exercise | sphygmomanometer | 25 | 84.6 | 105.7 | 61.6 | 76% |

| No treatment | 30 | 77.5 | 44.1 | ||||

| Dellhag 1992 | Wax bath + exercise | Grippit | 13 | 72.4 | 79.2 | ‐6.2 | ‐8% |

| No treatment | 12 | 82.6 | 85.4 | ||||

| Hoenig 1993 | Tendon gliding exercise +therapy putty | modified aneroid manometer | 10 | 84.2 | 97.6 | 16.5 | 22% |

| No treatment | 11 | 68.2 | 81.1 | ||||

| Ring | Continuous passive motion | Jamar dynamometer | 10 | 3.2 | 2.3 | ‐1.4 | ‐40% |

| Routine treatment | 12 | 3.8 | 3.7 | ||||

6. Clinical Relevance Table: Training of Motor functions; range of motion.

| Study | Treatment group | Outcome scale | N of patients | Baseline mean | End of study | Absolute benefit | Relative benefit |

| Brighton 1993 | Daily hand exercise | Goniometer Meta Phalangea Flexion | 25 | 76.7 | 79.0 | 6.3 | 8% |

| No treatment | 30 | 80.4 | 72.7 | ||||

| Dellhag 1992 | Wax bath + exercise | Goniometer Flexion dominant hand | 13 | 62.3 | 52.1 | ‐9.9 | ‐16% |

| No treatment | 13 | 59.4 | 62.0 | ||||

| Hoenig 1993 | Tendon gliding exercise +therapy putty | Goniometer metacarpa phalangea extension | 10 | 9.9 | 10.1 | ‐6.5 | ‐55% |

| No treatment | 11 | 13.5 | 16.6 | ||||

| Ring 1998 | Continuous passive motion | Goniometer mean of all digits | 10 | 34 | 39 | ‐8 | ‐27% |

| Routine treatment | 12 | 25 | 47 | ||||

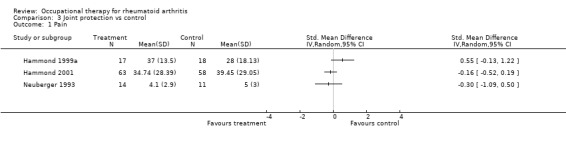

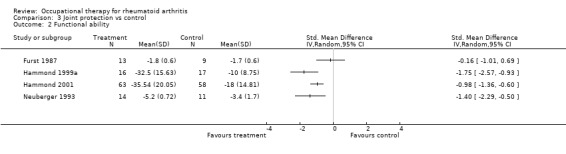

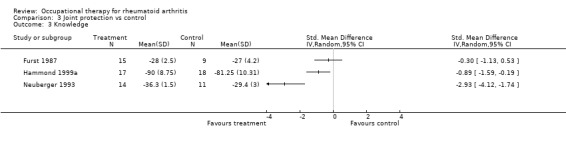

Hammond 1999a and Neuberger 1993 compared in their studies INSTRUCTION ON JOINT PROTECTION AND ENERGY CONSERVATION with no treatment whereas Hammond 2001 and Furst 1987 compared this intervention with alternative treatment. Also four ODs (Barry 1994, Cartlidge 1984, Hammond 1994, Hammond 1999b) evaluated a joint protection instruction in a pre‐post test design. Follow up was measured between 3 weeks and 6 months. Hammond 2001 measured after one year follow up. Eight studies (Furst 1987, Neuberger 1993, Hammond 1999a, Hammond 2001, Barry 1994, Hammond 1994, Hammond 1999b) assessed functional ability. The two high quality RCT (Hammond 1999a, Hammond 2001) found significant improvement on functional ability. This finding was supported by a low quality CCT (Neuberger 1993) and one OD of sufficient quality. The relative difference between experimental and control groups ranged from 6% to 187%. Five studies (Furst 1987, Neuberger 1993, Hammond 1999a, Hammond 2001, Hammond 1999b) measured pain. Both high quality RCTs (Hammond 1999a, Hammond 2001) reported no significant differences between groups. The relative difference for pain ranged from ‐17% to 25%. All but one study (Hammond 1994) measured one or more process measures. Of those, seven studies (Furst 1987, Neuberger 1993, Hammond 1999a, Barry 1994, Cartlidge 1984, Hammond 1999b) assessed knowledge; two RCTs/CCTs (Neuberger 1993, Hammond 1999a) presented a significant increase in knowledge after instruction on joint protection. All sufficient methodological quality ODs (Barry 1994, Cartlidge 1984, Hammond 1999b) supported these findings. Hammond 1999a was the only study that reported safety/side effects. She reported a decrease in grip strength and range of motion but questions wether this is due to improved joint protection behavior or a determinant of increased joint protection behaviour. Thus, on the basis of the results of two high quality RCTs (Hammond 1999a, Hammond 2001) there is strong evidence that instruction on joint protection leads to an improvement of functional ability.

Hass 1997 compared two different ADVICE/INSTRUCTION ABOUT ASSISTIVE DEVICES interventions in a low quality CCT. This study did not report sufficient details to calculate effect sizes and found no significant differences between both groups at 1 year follow up. The relative difference between the experimental and control group on pain was 10%, on functional ability 23% and on participation 21%. The sufficient quality OD (Nordenskiöld 1994) evaluated the use of assistive devices on pain in a pre‐post test. She reported a significant decrease of pain using assistive devices while performing kitchen tasks. No safety/side effects were assessed in the included studies.

Thus, there is insufficient data to determine the effectiveness of advice/instruction of assistive devices.

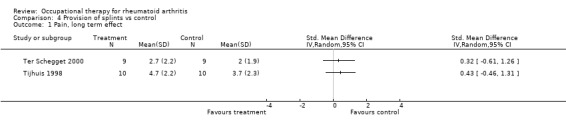

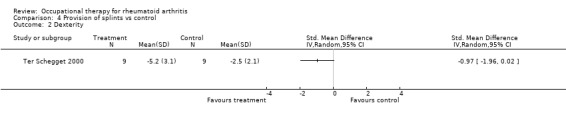

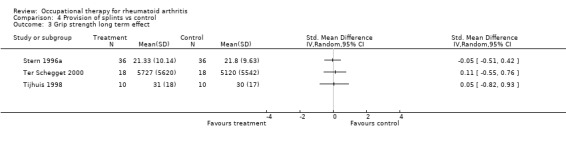

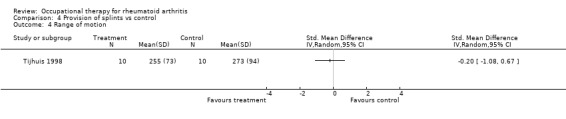

For the intervention PROVISION OF SPLINTS pain was assessed with regard to two aspects. The effect on pain immediately after provision of the splint was evaluated in three studies (Nordenskiöld 1990, Pagnotta 1998, Rennie 1996). Nordenskiöld 1990 and Pagnotta 1998 reported a significant decrease in pain while wearing working splints. The effect on pain after splinting for a period of 1 week to 1.5 year was assessed in ten studies (Stern 1996a, Ter Schegget 2000, Tijhuis 1998, McKnight 1982, Callinan 1995, Feinberg 1992, Feinberg 1981, Malcus 1992, McKnight 1992, Spoorenberg 1994). Only studies which compared splinting with no treatment (McKnight 1982, Callinan 1995) presented positive significant results. The relative difference between groups presented by the high quality RCTs (Ter Schegget 2000, Tijhuis 1998) ranged from 19% to 36%. Five studies (Stern 1996a, Ter Schegget 2000, Pagnotta 1998, Rennie 1996, Spoorenberg 1994) assessed measures of functional ability (dexterity). One low quality RCT (Stern 1996a) presented a significant decline in dexterity after one week of working‐splint‐wear. Fifteen studies measured one or more process measures. Compliance with splinting was assessed by five studies (Callinan 1995, Feinberg 1992, Agnew 1995, Feinberg 1981, Spoorenberg 1994), all with a low methodological quality. One RCT (Feinberg 1992) reported positive significant results on compliance. Grip strength was assessed with regard to two aspects. The effect on grip strength immediately after provision of the splint was evaluated in six studies (Stern 1996b, Ter Schegget 2000, Tijhuis 1998, Nordenskiöld 1990, Rennie 1996, Anderson 1987). Two high quality studies (Nordenskiöld 1990, Rennie 1996) presented an increase in grip strength while wearing a splint. The effect of splinting on grip strength after a period of time was measured in four RCTs/CCTs (Stern 1996b, Ter Schegget 2000, Tijhuis 1998, Callinan 1995). The two high quality RCTs (Ter Schegget 2000, Tijhuis 1998) reported no significant differences between groups. The relative difference ranged from ‐24% to 6% (Table 11). Four studies (Ter Schegget 2000, Tijhuis 1998, Palchik 1990, Feinberg 1981) measured range of motion. The two high quality RCTs (Ter Schegget 2000, Tijhuis 1998) reported no significant differences between groups. One low quality RCT (Palchik 1990) presented significant results after wearing an anti‐boutonniere splint for 6 weeks. The relative difference between groups ranged from ‐75% to 7% (Table 12). Twelve studies reported on safety side effects. Callinan 1995 reported that arm and hand functions were not significantly affected by splint wear. Palchik 1990 shows that patients wearing silver rings for a boutonniere deformity had more difficulties with active flexion following removal of the splint. Stern 1996a (Stern 1996b, Stern 1997) reported a decrease of grip strength when wearing working splints and patients in the study reported removing the splint when doing activities that required dexterity. Ter Schegget 2000 reported that wearing a splint for swan neck deformity did not effect grip strength. Tijhuis 1998 reported that a futuro working splint did not interfere with hand function. Pagnotta 1998 reports that splint wear hinders dexterity. McKnight 1982 (McKnight 1992) shows an increase of carpal tunnel syndrome symptoms when wearing an air pressure splint. Agnew 1995 and Spoorenberg 1994 both report restriction of hand movement while wearing splints. Feinberg 1981 reports no changes in rang of motion after splint wear. Malcus 1992 presents a decrease in range of motion after wearing a anti‐ulnar deviation splint. Thus, there are indicative findings that splints are effective in reducing pain both immediately after provision of the splint and after splinting over a period of time. Also there are indicative findings that splinting has a negative effect on dexterity. Furthermore, indicative findings for a gain in grip strength immediately after provision of the splint have been found.

7. Clinical relevance Table: Provision of splints; grip strength.

| Study | Treatment group | Outcome scale | N of patient | Baseline mean | End of study | Absolute benefit | Relative benefit |

| Anderson 1987 | Palmar working splint | sphygmomanometer | 19 | 92.5 | 103.5 | 6 | 6% |

| no splint | 19 | 92.5 | 97.5 | ||||

| Anderson 1987 | Dorsal working splint | sphygmomanometer | 18 | 92.5 | 97.9 | 0.4 | 0% |

| no splint | 19 | 92.5 | 97.5 | ||||

| Anderson 1987 | Gauntlet working splint | sphygmomanometer | 17 | 92.5 | 76.8 | ‐20.7 | ‐22% |

| no splint | 19 | 92.5 | 97.5 | ||||

| Anderson 1987 | Fabric ready made working splint | sphygmomanometer | 19 | 92.5 | 75.3 | ‐22.3 | ‐24% |

| no splint | 19 | 92.5 | 97.5 | ||||

| Tijhuis 1998 | Thermo lynn working splint | martin vigorimeter | 10 | 31.0 | 30.0 | ‐3 | ‐9% |

| Futuro working splint | 10 | 35.0 | 33.0 |

8. Clinical relevance Table: Provision of splints; range of motion.

| Study | Treatment group | Outcome scale | N of patients | Baseline mean | End of study | Absolute benefit | Relative benefit |

| Palchik 1990 | Gutter splint boutonniere finger | goniometer | 3 | 14.3 | 6.3 | ‐10.4 | ‐75% |

| no splint | 5 | 13.3 | 16.7 | ||||

| Tijhuis 1998 | Thermo lynn working splint | goniometer | 10 | 255 | 255 | ‐18 | ‐7% |

| Futuro working splint | 10 | 257 | 273 |

SENSITIVITY ANALYSES Three sensitivity analyses were performed to check for the robustness of the outcome of the best evidence syntheses. Considering only studies that scored a high or sufficient methodological quality, the outcome of the best evidence syntheses for all interventions, except "provision of splints" are the same as the results presented. Within the category "provision of splints" only the indicative findings for evidence of splinting on the immediate decrease of pain will hold.

Analysing the results with incorporation of studies with a score of 4 items or more on the internal validity criteria, the outcome of the best evidence synthesis are, for all interventions except "comprehensive OT", similar to the results presented. Within the category "comprehensive OT" the results of three studies (Helewa 1991, Kraaimaat 1995, Mowat 1980) instead of one contribute to the best evidence synthesis. Two studies (Kraaimaat 1995, Mowat 1980) reported no significant results on functional abilities whereas one (Helewa 1991) did. As a result the finding of 'limited evidence' changes to 'indicative findings' for the evidence of efficacy of OT on functional ability.

Nineteen studies (Callinan 1995, Feinberg 1981, Feinberg 1992, Furst 1987, Hammond 1994, Hammond 1999a, Hammond 1999b, Helewa 1991, Hoenig 1993, Kraaimaat 1995, Malcus 1992, McAlphine 1991, McKnight 1982, McKnight 1992, Nordenskiöld 1990, Pagnotta 1998, Spoorenberg 1994, Stern 1996a, Tijhuis 1998) reported the ACR criteria for diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis explicitly as inclusion criteria for the patients. Considering only those studies in the analysis results for all intervention categories except "instruction of joint protection" are the same as the results presented. Within the category "instruction of joint protection" one high quality RCT (Hammond 2001) did not report the ACR criteria. Without the results of this study the outcome of the best evidence synthesis changes from strong to limited evidence.

Discussion

In this review the efficacy of several occupational therapy interventions for rheumatoid arthritis was explored. Seven different intervention categories were distinguished. The outcome measures were pain, fatigue, functional ability, and social participation. Process measures such as knowledge about disease management, compliance, self‐efficacy, grip strength, and range of motion were also taken into account. This systematic review established limited evidence for the efficacy of comprehensive OT and strong evidence for the efficacy of the intervention "instruction on joint protection" on functional ability. For the intervention "provision of splints" indicative findings for a decrease in pain were demonstrated. Indicative findings for a negative effect of splinting on dexterity were discovered, as were indicative findings for evidence that grip strength increases after provision of splints.

Our results on the intervention category "provision of splints" are a little different from the results found in the Cochrane Review on splints for rheumatoid arthritis (Egan 2003). They conclude insufficient evidence whereas we conclude indicative findings. Our conclusions are partially based on sufficient quality ODs which were not included in the Egan 2003 review.

RCTs/CCTs and studies with other designs (ODs) were included in this review. Sixteen ODs were identified. A distinction was made between ODs with a sufficient methodological quality and ODs that lacked a sufficient methodological quality. Because of the weakness of the internal validity of ODs, sufficient methodological quality ODs could only state 'indicative findings' in the used best evidence synthesis. The incorporation of the outcomes of ODs resulted in indicative findings for a decrease in pain immediately after provision of the splint. Within the other intervention categories, results of ODs did not contribute to the outcome of the best evidence synthesis because RCTs and/or CCTs were available. However, in most categories of interventions the results of ODs supported the findings of RCTs/CCTs. So, in emerging fields of research, like occupational therapy research is, results of studies other than controlled trials may have some value in judging the effectiveness of interventions when there is a lack of RCTs and CCTs.

Overall, the methodological quality of the studies was rather poor. Only six of the sixteen RCTs had a high methodological quality. No CCTs with a high methodological quality were identified and only half of the sixteen ODs, given the methodological constraints of ODs, were considered of sufficient methodological quality. Bias was possible since most studies did not report on blinding of patients, blinding of care providers and blinded outcome assessors. Since blinding of patients and care providers is rather difficult in allied health interventions, especially the blinding of the outcome assessor is of paramount importance to avert detection bias (Siemonsma 1997, Day 2000)

The nature of the occupational therapy interventions varied widely, even within intervention categories, large differences in interventions with regard to type of treatment, duration, and setting precluded comparing results. Furthermore, poor data presentation impeded the comparisons of results among studies. Only six RCTs presented sufficient data to compute effect sizes. In future research, special attention should be given to the presentation of study results according international standards (Begg 1996). Finally, outcome measures were very heterogeneous: for each outcome and process measure several measurement instruments were used. To overcome this problem international consensus about a 'core set' of outcome measures for the outcome of occupational therapy in rheumatoid arthritis is needed. The first question to be addressed should be which outcomes are most important for occupational therapy. The second question concerns which outcome instruments are most reliable, valid, responsive and easy to obtain.

The power of the studies included in this review was rather poor. To detect a medium effect size of 0.5 (with =0.05, and power at 80%) , the sample size per group needs to be at least 50 (Cohen 1988). Only three controlled studies had a sample size with 50 or more participants per group (Hammond 2001, Hass 1997, Helewa 1991). The findings of this review could be an underestimation of the real evidence for the efficacy of occupational therapy due to the limited power of the studies. On the other hand, the results of this review could also be an overestimation because of publication bias by unpublished small negative studies.

Several items should be considered in future research about the efficacy of occupational therapy. To improve the methodological quality of studies proper randomization procedures should be performed after baseline assessment with special attention to the concealment of allocation. Another important issue is the blinding of the outcome assessor. Since blinding of patients and care providers is almost impossible for OT interventions, procedures to guarantee the blinding of the outcome assessors are needed to prevent bias. Statistical significant differences are more likely to occur in studies with sufficient power. This means that large groups of rather homogenous participants should be included in trials that compare the experimental intervention with no treatment or, if not possible, with a treatment with a clear contrast. Furthermore, outcome measures should be carefully chosen with regard to the aim of the intervention. Studies in which outcome measures are applied that are relevant and responsive are more likely to result in statistically significant differences between groups.

The inventory of studies in this review reveals important gaps in occupational therapy research. No studies were found for the category "Training of skills" and only two studies were found for the intervention "Instruction / advice assistive devices". This is remarkable because "Training of skills" and "Instruction / advice assistive devices" are very common occupational therapy interventions (3). Another finding is the lack of data on the outcome measure social participation. The ultimate goal of occupational therapy is to restore / maintain full participation in all social activities: outcome measures should reflect this aim.

In conclusion, we found strong evidence for the efficacy of instruction of joint protection on functional ability. Studies that evaluated comprehensive OT showed limited evidence for the effectiveness on functional ability. Studies that evaluated splint interventions reported indicative findings for the effectiveness on pain. These results are encouraging for the occupational therapy practice as an important part in the treatment of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Also, this review revealed that important fields of occupational therapy, like "training of skills" and "advice in the use of assistive devices", are under researched and should get more attention. On the basis of this review we recommend that further clinical trials are necessary for each category of interventions. In future studies special attention should be given to the design of trials, the use of responsive, reliable and valid outcome measures, the inclusion of a sufficient number of patients to create statistical power and the presentation of trial results according international standards.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

This review has shown positive effect of comprehensive occupational therapy and instruction on joint protection on the important outcome functional ability. It also revealed an indication of efficacy for splinting on pain and grip strength. Provision of splints may have a decrease of dexterity as a side effect. The reviewers conclude that occupational therapy can help patients with rheumatoid arthritis to overcome problems in performing daily live activities.

Implications for research.

A ' core set' of outcome measures for the outcome of occupational therapy, reflecting the ultimate aim to restore or maintain full participation in all social and daily activities, for rheumatoid arthritis patients is needed. To state the efficacy of occupational therapy interventions, research in specific categories such as training of skills and advice/instruction of assistive devices should be extended. More high quality RCTs are needed.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 8 July 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. CMSG ID: C058‐R |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 2, 2001 Review first published: Issue 1, 2004

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 18 November 2003 | New citation required and conclusions have changed | Substantive amendment |

Notes

For information concerning the multi‐disciplinary education of rheumatoid arthritis patients we refer to the review "Patient Education for rheumatoid arthritis" by Riemsma RP, Kirwan JR, Taal E, Rasker JJ.

This review is an update of the publication: Steultjens EMJ, Dekker J, Bouter LM, Van Schaardenburg D, Van Kuyk MAH, Van den Ende CHM. Occupational therapy for rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review. Arthritis and Rheumatism, Arthritis Care and Research. 2002; 47:672‐685

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Mrs. M.L Dapper and Mr. F.I. Valster for discussing occupational therapy issues and Mrs. E. Weijzen and Mrs. N. Breuning for making the search strategy applicable to all the searched databases.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Search strategy for controlled trials

("randomized controlled trials"[MESH] OR "controlled clinical trials"[MESH] OR "random allocation"[MESH] OR "double‐blind method"[MESH] OR "single blind method"[MESH] OR "cross over studies"[MESH] OR "clinical trials"[MESH] OR "research design"[MESH] OR "epidemiologic research design"[MESH] OR "program evaluation"[MESH] OR crossover stud* OR clinical trial* OR ((singl* OR doubl* OR trebl* OR tripl*) AND (blind* OR mask*)) OR random*

Appendix 2. Search strategy for OD

OR patient serie* OR case serie* OR program* OR experiment* OR observation* OR method* OR effect* ).

Appendix 3. Search strategy for rheumatoid arthritis

("Arthritis, Rheumatoid"[MESH] OR arthritis OR rheumatoid arthritis) AND

Appendix 4. Search strategy for occupational therapy interventions

("occupational therapy"[MESH] OR "activities of daily living"[MESH] OR "self‐help devices"[MESH] OR "splints"[MESH] OR "patient education" [MESH] OR "counseling"[MESH] OR "exercise therapy"[MESH] OR occupational therapy OR activities of daily living OR self care OR assistive devices OR assistive technology OR dexterity OR joint protection OR counsel?ing)

Appendix 5. Criteria of methodological quality

RCTs, CCTs

Patient selection a) were the eligibility criteria specified? b) treatment allocation: a) was a method of randomization performed? b) was the treatment allocation concealed? c) were the groups similar at baseline regarding the most important prognostic indicators? Interventions d) were the index and control interventions explicitly described? e) was the care provider blinded for the intervention? f) were co‐interventions avoided or comparable? g) was the compliance acceptable in all groups? h) was the patient blinded to the intervention? Outcome measurement i) Was the outcome assessor blinded to the interventions? j) were the outcome measures relevant? k) were adverse effects described? l) was the withdrawal/drop out rate described and acceptable? m) timing follow‐up measurements: a) was a short‐term follow‐up measurement performed? b) was a long‐term follow‐up measurement performed? n) was the timing of the outcome assessment in both groups comparable? Statistics o) was the sample size for each group described? p) did the analysis include an intention‐to‐treat analysis? q) were point estimates and measures or variability presented for the primary outcome measures?

OD (other designs)

Patient selection a) were the eligibility criteria specified? Interventions d) was the intervention explicitly described? f) were cointerventions avoided? g) was the compliance acceptable? Outcome measurement i) Was the outcome assessor not involved in the treatment? j) were the outcome measures relevant? k) were adverse effects described? l) was the withdrawal/drop out rate described and acceptable? m) timing follow‐up measurements: a) was a short‐term follow‐up measurement performed? b) was a long‐term follow‐up measurement performed? n) was the timing of the outcome assessment in all patients comparable? Statistics o) was the sample size of the patient group described? p) did the analysis include an intention‐to‐treat analysis? q) were point estimates and measures or variability presented for the primary outcome measures?

Internal validity: b, e, f, g, h, i, j, l, n, p; descriptive criteria: a, c, d, k, m; statistical criteria: o, q.

Appendix 6. Best evidence synthesis

Strong evidence provided by consistent, statistically significant findings in outcome measures in at least two high quality RCTs

Moderate evidence provided by consistent, statistically significant findings in outcome measures in at least one high quality RCT and at least one low quality RCT or high quality CCT

Limited evidence provided by statistically significant findings in outcome measures in at least one high quality RCT or: provided by consistent, statistically significant findings in outcome measures in at least two high quality CCTs ( in the absence of high quality RCTs)

Indicative findings provided by statistically significant findings in outcome and/or process measures in at least one high quality CCTs or low quality RCTs ( in the absence of high quality RCTs) or: provided by consistent, statistically significant findings in outcome and/or process measures in at least two high quality ODs (in the absence of RCTs and CCTs)

No or insufficient evidence in case of results of eligible studies do not meet the criteria for one of the above stated levels of evidence or: in case of conflicting (statistical significant positive and statistical significant negative) results among RCTs and CCTs or: in case of no eligible studies

If the amount of studies that show evidence is less than 50% of the total number of found studies within the same category of methodological quality and study design (RCT, CCT or OD) we stated no evidence.

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Comprehensive Occupational therapy vs control.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Pain | 1 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 2 Functional ability | 2 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 3 Depression | 2 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | Totals not selected |

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Comprehensive Occupational therapy vs control, Outcome 1 Pain.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Comprehensive Occupational therapy vs control, Outcome 2 Functional ability.

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Comprehensive Occupational therapy vs control, Outcome 3 Depression.

Comparison 2. Training of motor functions vs control.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Grip strength | 2 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | Totals not selected |

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Training of motor functions vs control, Outcome 1 Grip strength.

Comparison 3. Joint protection vs control.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Pain | 3 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 2 Functional ability | 4 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 3 Knowledge | 3 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | Totals not selected |

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Joint protection vs control, Outcome 1 Pain.

3.2. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Joint protection vs control, Outcome 2 Functional ability.

3.3. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Joint protection vs control, Outcome 3 Knowledge.

Comparison 4. Provision of splints vs control.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Pain, long term effect | 2 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 2 Dexterity | 1 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 3 Grip strength long term effect | 3 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 4 Range of motion | 1 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | Totals not selected |

4.1. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Provision of splints vs control, Outcome 1 Pain, long term effect.

4.2. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Provision of splints vs control, Outcome 2 Dexterity.

4.3. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Provision of splints vs control, Outcome 3 Grip strength long term effect.

4.4. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Provision of splints vs control, Outcome 4 Range of motion.

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Agnew 1995.

| Methods | OD, retrospective | |

| Participants | RA, new wrist working splint < 12 months, outpatients N = 130 | |

| Interventions | Wrist working splint with instruction in education class | |

| Outcomes | Compliance | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | D ‐ Not used |

Anderson 1987.

| Methods | RCT | |

| Participants | RA, outpatients N = 92 | |

| Interventions | 4 types working splints compared to no treatment | |

| Outcomes | Grip strength | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Barry 1994.

| Methods | OD | |

| Participants | RA, no OT before, outpatients N = 55 | |

| Interventions | Individual OT session 1 hr | |

| Outcomes | Functional ability | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | D ‐ Not used |

Brighton 1993.

| Methods | RCT | |

| Participants | RA, sero‐positive rheumatoid facor > 1 yr, erosion in MCP/PIP, in community N = 44 | |

| Interventions | Hand exercise at home + therapist reinforcement each 3 months versus no treatment | |

| Outcomes | Grip strength Range of Motion | |

| Notes | discrepancy in presentation of number of subjects in text 44 in table 55 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Callinan 1995.

| Methods | RCT, cross‐over design | |

| Participants | RA, presence of hand pain/ morning stiffness, outpatients N = 45 | |

| Interventions | soft resting splint or hard resting splint versus no treatment | |

| Outcomes | Pain Functional ability Compliance Grip strength | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Cartlidge 1984.

| Methods | OD | |

| Participants | RA, comprehend English, outpatients N = 22 | |

| Interventions | four films shown about RA, joint protection, coping with ADL problems | |

| Outcomes | Participation Knowledge | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | D ‐ Not used |

Dellhag 1992.

| Methods | CCT | |

| Participants | RA, < 70 yrs, disease duration >6<10 yrs, class 1‐2, decreased ROM / gripstrength N =52 | |

| Interventions | Wax bath and hand exercise 3 x wk ‐ 4 weeks versus no treatment | |

| Outcomes | Pain Dexterity Grip strength Range of motion | |

| Notes | Other groups received only wax or hand exercise | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | D ‐ Not used |

Feinberg 1981.

| Methods | OD | |

| Participants | RA, provided with resting splint, outpatients N = 50 | |

| Interventions | resting splint +sufficient information for use | |

| Outcomes | Pain Compliance | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | D ‐ Not used |

Feinberg 1992.

| Methods | CCT | |

| Participants | RA, class 1‐2, outpatients N = 46 | |

| Interventions | Resting splint + extensive compliance enhancement versus resting splint + sufficient information for use | |

| Outcomes | Pain Compliance | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | D ‐ Not used |

Furst 1987.

| Methods | CCT | |

| Participants | RA > 1 yr, no energy conservation training received > 18 yrs, in‐ and outpatients N = 28 | |

| Interventions | Group/individual OT education program using specific didactic format versus individual routine OT treatment | |

| Outcomes | Pain Fatigue Functional ability Participation Knowledge Grip strength | |

| Notes | same study as Gerber 1987 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | D ‐ Not used |

Gerber 1987.

| Methods | CCT | |

| Participants | RA > 1 yr, no energy conservation training received > 18 yrs, in‐ and outpatients N = 28 | |

| Interventions | Group/individual OT education program using specific didactic format versus individual routine OT treatment | |

| Outcomes | Pain Fatigue Functional ability Participation Knowledge Grip strength | |

| Notes | same study as Furst 1987 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | D ‐ Not used |

Hammond 1994.

| Methods | OD | |

| Participants | RA, wrist/hand involvement, problems with kitchen task, outpatients N = 11 | |

| Interventions | Group OT education 3,5 hours ‐ 2 sessions | |

| Outcomes | Functional ability | |

| Notes | Study used other measures to establish relationship with joint protection behavior | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | D ‐ Not used |

Hammond 1999a.

| Methods | RCT | |

| Participants | RA, class 3, wrist‐hand involvement, outpatients N = 35 | |

| Interventions | Group OT education based on health belief model / self efficacy theory versus no treatment | |

| Outcomes | Pain Functional ability Knowledge Self‐efficacy Grip strength Range of motion | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Hammond 1999b.

| Methods | OD | |

| Participants | RA, wrist‐hand involvement, problems with kitchen task, outpatients N = 25 | |

| Interventions | Group OT education 2 hours‐2 sessions | |

| Outcomes | Pain Functional ability Knowledge | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | D ‐ Not used |

Hammond 2001.

| Methods | RCT | |

| Participants | < 5 years RA in hand or wrist , reffered for joint protection outpatients N=127 | |

| Interventions | small group OT versus standard education group 4 x 2 hours | |

| Outcomes | Pain Functional ability Quality of Life Self‐efficacy Grip strength Range of motion | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

Hass 1997.

| Methods | CCT | |

| Participants | RA, in community N = 190 | |

| Interventions | Group OT session with improved user information and altered selction proces for assistive devices versus routine prescription of devices | |

| Outcomes | Pain Functional ability Participation | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Helewa 1991.

| Methods | RCT | |

| Participants | RA, limitation in physical function, clinical stable, in community N = 105 | |

| Interventions | Individual OT for 6 weeks versus no treatment | |

| Outcomes | Pain Functional ability Depression: | |

| Notes | between 6‐12 weeks controls received OT treatment | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Hoenig 1993.

| Methods | RCT | |

| Participants | RA, Class 2‐3, in community N = 57 | |

| Interventions | ROM tendon gliding exercises + resistive theraputty 85 versus no treatment | |

| Outcomes | Pain Dexterity Grip strength Range of Motion | |

| Notes | other groups received ROM exercise of resistive theraputty | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Huiskes 1991.

| Methods | RCT | |

| Participants | RA, class 1‐3, minimal age 20, duration of ilness > 1 year, outpatients N = 77 | |

| Interventions | Group OT for 2 hrs/10 weeks versus no treatment | |

| Outcomes | Pain Functional ability Anxiety Knowledge | |

| Notes | Same study as Kraaimaat 1995 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Kraaimaat 1995.

| Methods | RCT | |

| Participants | RA, class 1‐3, minimal age 20, duration of ilness > 1 year, outpatients N = 77 | |

| Interventions | Group OT for 2 hrs/10 weeks versus no treatment | |

| Outcomes | Pain Functional ability Anxiety Knowledge | |

| Notes | Trial designed to test hypothesis on cognitive behavior therapy | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Malcus 1992.

| Methods | OD | |

| Participants | RA, bilateral ulnar deviation, correction to normal position possible, outpatients N = 7 | |

| Interventions | Anti‐ulnar resting splint at night for 1 year | |

| Outcomes | Pain Grip strength | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | D ‐ Not used |

McAlphine 1991.

| Methods | OD | |

| Participants | RA, 1 previous OT assessment N = 24 | |

| Interventions | 1 OT session in hospital follow up if needed in community | |

| Outcomes | Functional ability | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | D ‐ Not used |

McKnight 1982.

| Methods | OD | |

| Participants | RA, bilateral synovitis MCP, PIP, DIP, wrist swelling, joint pain and stiffness, inpatients | |

| Interventions | Air compression splint 10 minutes fingers in extension, 10 minutes in flexion for 5 days | |

| Outcomes | Pain Grip strength | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | D ‐ Not used |

McKnight 1992.

| Methods | OD | |

| Participants | RA, bilateral synovitis MCP, PIP, DIP, wrist, inpatients | |

| Interventions | Isotoner glove 7 nights other hand had Futuro glove | |

| Outcomes | Pain Grip strength | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | D ‐ Not used |

Mowat 1980.

| Methods | RCT | |