Abstract

Currently, patients with extremity soft tissue sarcoma (eSTS) who have undergone curative resection are followed up by a heuristic approach, not covering individual patient risks. The aim of this study was to develop two flexible parametric competing risk regression models (FPCRRMs) for local recurrence (LR) and distant metastasis (DM), aiming at providing guidance on how to individually follow-up patients. Three thousand sixteen patients (1931 test, 1085 validation cohort) with high-grade eSTS were included in this retrospective, multicenter study. Histology (9 categories), grading (time-varying covariate), gender, age, tumor size, margins, (neo)adjuvant radiotherapy (RTX), and neoadjuvant chemotherapy (CTX) were used in the FPCRRMs and performance tested with Harrell-C-index. Median follow-up was 50 months (interquartile range: 23.3–95 months). Two hundred forty-two (12.5%) and 603 (31.2%) of test cohort patients developed LR and DM. Factors significantly associated with LR were gender, size, histology, neo- and adjuvant RTX, and margins. Parameters associated with DM were margins, grading, gender, size, histology, and neoadjuvant RTX. C-statistics was computed for internal (C-index for LR: 0.705, for DM: 0.723) and external cohort (C-index for LR: 0.683, for DM: 0.772). Depending on clinical, pathological, and patient-related parameters, LR- and DM-risks vary. With the present model, implemented in the updated Personalised Sarcoma Care (PERSARC)-app, more individualized prediction of LR/DM-risks is made possible.

Keywords: soft tissue sarcoma, follow-up, flexible parametric competing risk regression model, local recurrence, distant metastasis

1. Introduction

Patients with high-grade extremity soft tissue sarcoma (eSTS) are at risk of developing local recurrences (LR) and even more so of developing distant metastases (DM) after having undergone surgical resection of the primary tumor [1,2,3,4,5]. These rates differ substantially per size, grade, and subtype [6]. Close follow-up regimens are currently used in order to detect LR and DM at stages where they are still potentially treatable by re-resection or metastasectomy, respectively [7]. There is no clear consensus when, by what means, and how often to perform follow-up in eSTS patients, with many centers and guidelines having introduced a heuristic approach: for the first 3 years after surgery, patients would be checked three or four times a year, then biannually for the following two years and annually thereafter [8,9].

Imposing all eSTS patients on these strict follow-up regimens has raised public, scientific, and health economic concerns over the last years. Numerous factors interact with the risk of developing LR or DM, such as histological STS-subtypes, surgical margins, tumor size, grade, administration of neo(adjuvant) radiotherapy (RTX) or chemotherapy (CTX), and patient-derived factors [1,2,3,4,10,11,12]. Consequently, the current approach of “one-size-fits-all” may not account for the unequal risk of recurrence in the heterogeneous eSTS population, involving an excessive number of surveillance imaging, possibly leading to unnecessary delivery of imaging-induced radiation exposure, and the inherent burden for radiology departments, as well as inappropriately refraining from it, a high number of outpatient visits and financial costs and emotional stress for each individual patient [13]. However, an evaluation of prognostic factors for LR and DM taking into consideration the time-varying rate for the occurrence of events in a multicenter cohort, including important patient-(i.e., age, gender), tumor-(e.g., size, grade, histological subtype), and treatment-related features (e.g., margins, (neo)adjuvant CTX/RTX), is currently missing.

Therefore, the aim of the present study was to estimate and validate two models predicting risks of LR and DM over the first 5 years of follow-up by applying flexible parametric competing risk regression modeling in a large, multicenter cohort of patients with primary localized high-grade eSTS. The results have been implemented into the Personalised Sarcoma Care (PERSARC)-app [14] for Individualized Sarcoma Care and follow-up.

2. Results

Patients had undergone surgery with curative intent between January 1994 and October 2014 for the test cohort and between January 2000 and December 2013 for the validation cohort, respectively. There was a slight male predominance (n = 1038; 53.8%) and the median patient age was 59 years (interquartile range (IQR): 44.7–70 years). With 55.8%, 17.9%, and 13.9%, most tumors in the test cohort were located in the thigh (n = 1078), upper arm (n = 346), and lower leg (n = 268), while the lower arm (n = 142), the foot or toes (n = 65), and the hand or fingers (n = 32) were affected in 7.3%, 3.4%, and 1.7%, respectively. Further clinicopathological features for both the test and validation cohort are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics and clinical, pathological, and treatment-related parameters.

| Variables | Test Cohort (n = 1931) | Validation Cohort (n = 1085) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | Missing (%) | N (%) | Missing (%) | p-Value * | ||

| Age (continuous; years; median + IQR) | 59 (44.7–70) | 45 (2.3) | 61 (47–74) | 0 (0.0) | <0.0001 | |

| Gender | Male | 1038 (53.8) | 0 (0.0) | 615 (56.7) | 0 (0.0) | 0.121 |

| Female | 893 (46.2) | 470 (43.3) | ||||

| Tumor Location | Upper Extremity | 520 (26.9) | 1 (0.05) | 312 (28.8) | 0 (0.0) | 0.285 |

| Lower Extremity | 1410 (73.1) | 773 (71.2) | ||||

| Depth | Epifascial | 518 (26.9) | 2 (0.1) | 291 (26.8) | 0 (0.0) | 0.984 |

| Subfascial | 1411 (73.1) | 794 (73.2) | ||||

| Tumor Size (continuous; cm; median + IQR) | 7 (4–11) | 30 (1.6) | 7.5 (5–12) | 5 (0.5) | 0.026 | |

| Histology | Myxoid liposarcoma | 222 (11.6) | 16 (0.8) | 111 (10.2) | 0 (0.0) | <0.0001 |

| MPNST | 83 (4.3) | 43 (4.0) | ||||

| Myxofibrosarcoma | 451(23.6) | 104 (9.6) | ||||

| Synovial Sarcoma | 174 (9.1) | 79 (7.3) | ||||

| UPS | 325 (17.0) | 375 (34.6) | ||||

| Angiosarcoma/Vascular Sarcoma | 22 (1.1) | 20 (1.8) | ||||

| Dedifferentiated/Pleomorphic Liposarcoma | 141 (7.4) | 85 (7.8) | ||||

| Leiomyosarcoma | 221 (11.5) | 118 (10.9) | ||||

| Others | 276 (14.4) | 150 (13.8) | ||||

| Grading | G2 | 719 (37.8) | 30 (1.6) | 382 (35.8) | 19 (1.8) | 0.282 |

| G3 | 1182 (62.2) | 684 (64.2) | ||||

| Margins | R0 | 1494 (77.4) | 0 (0.0) | 768 (70.8) | 0 (0.0) | <0.0001 |

| R1/2 | 437 (22.6) | 317 (29.2) | ||||

| CTX | No | 1408 (73.0) | 1 (0. 05) | 1039 (95.8) | 0 (0.0) | <0.0001 |

| Neoadjuvant | 262 (13.6) | 40 (3.7) | ||||

| Adjuvant | 209 (10.8) | 6 (0.6) | ||||

| Neoadjuvant + Adjuvant | 51 (2.6) | 0 (0.0) | ||||

| RTX | No | 619 (32.9) | 50 (2.6) | 335 (30.9) | 0 (0.0) | <0.0001 |

| Neoadjuvant | 303 (16.1) | 460 (42.4) | ||||

| Adjuvant | 956 (50.8) | 275 (25.4) | ||||

| Neoadjuvant + Adjuvant | 3 (0.2) | 15 (1.4) | ||||

| Follow-up (continuous; months; median + IQR) | 50 (23.3–95) | 11 (0.6) | 56 (21–91) | 0 (0.0) | 0.254 | |

* p-values calculated with Wilcoxon rank sum test for continuous variables, with chi2-test for binary and categorical variables. p-values in bold are considered statistically significant. Abbreviations: CTX = chemotherapy. IQR = interquartile range. MPNST = Malignant Peripheral Nerve Sheat Tumor. RTX = radiotherapy. UPS = Undifferentiated pleiomorphic sarcoma.

Five- and 10-year overall survival (OS) was 73.6% (95%CI: 71.3–75.7) and 62.7% (95%CI: 59.8–65.5) in the test cohort. In the validation cohort, 5- and 10-year OS were 64.9% (95%CI: 61.8–67.8) and 52.9% (95%CI: 48.9–56.8), respectively. Gender, tumor size, histological subtype (except for angiosarcoma/vascular sarcoma (p = 0.127) and dedifferentiated/pleomorphic liposarcoma (p = 0.254), margins, neoadjuvant and adjuvant RTX, as well as adjuvant CTX (all p < 0.05) had a significant influence on risk of LR in the stepwise backward selection of the Fine and Gray model. Grading as a time-dependent effect was kept in the model (p = 0.108), while age (p = 0.082) and neoadjuvant CTX (p = 0.214) were excluded. Consequently, gender, grading, tumor size, neoadjuvant and adjuvant RTX, histological subtype, and adjuvant CTX were included in the flexible parametric competing risk regression model (Table 2).

Table 2.

Estimated coefficients along with their 95% confidence intervals for local recurrence.

| Variables | Coefficient | 95%-CI | p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||||

| Local Recurrence | |||||

| Gender | Male | 1 | 0.011 | ||

| Female | 0.698 | 0.529 | 0.921 | ||

| Grading | G2 | 1 | 0.199 | ||

| G3 | 0.816 | 0.598 | 1.113 | ||

| Tumor size | 1.026 | 1.004 | 1.049 | 0.019 | |

| Margins | R0 | 1 | <0.001 | ||

| R1/R2 | 2.761 | 2.021 | 3.774 | ||

| Histology | Myxoid Liposarcoma | 1 | |||

| MPNST | 4.227 | 1.837 | 9.729 | 0.001 | |

| Myxofibrosarcoma | 4.156 | 2.056 | 8.400 | <0.001 | |

| Synovial Sarcoma | 3.116 | 1.429 | 7.014 | 0.005 | |

| UPS | 3.373 | 1.620 | 7.025 | 0.001 | |

| Angiosarcoma/Vascular Sarcoma | 3.316 | 0.981 | 12.341 | 0.074 | |

| Dedifferentiated/Pleomorphic Liposarcoma | 1.727 | 0.719 | 4.143 | 0.221 | |

| Leiomyosarcoma | 2.779 | 1.294 | 5.966 | 0.009 | |

| Others | 2.385 | 1.123 | 5.065 | 0.024 | |

| Neoadjuvant RTX | No | 1 | <0.001 | ||

| Yes | 0.298 | 0.178 | 0.494 | ||

| Adjuvant RTX | No | 1 | 0.001 | ||

| Yes | 0.603 | 0.447 | 0.814 | ||

| Adjuvant CTX | No | 1 | 0.008 | ||

| Yes | 1.711 | 1.154 | 2.538 | ||

| Restricted cubic spline 1 | 2.104 | 1.851 | 2.392 | <0.001 | |

| Restricted cubic spline 2 | 1.332 | 1.230 | 1.442 | <0.001 | |

| Restricted cubic spline 3 | 0.980 | 0.937 | 1.026 | 0.391 | |

| Restricted cubic spline for time-dependent effect of grading | 0.944 | 0.813 | 1.096 | 0.449 | |

| Constant | 0.048 | 0.024 | 0.097 | <0.001 | |

| Death | |||||

| Gender | Male | 1 | 0.005 | ||

| Female | 0.736 | 0.595 | 0.910 | ||

| Grading | G2 | 1 | <0.001 | ||

| G3 | 2.215 | 1.655 | 2.964 | ||

| Tumor size | 1.065 | 1.048 | 1.081 | <0.001 | |

| Margins | R0 | 1 | 0.296 | ||

| R1/R2 | 1.153 | 0.883 | 1.057 | ||

| Histology | Myxoid Liposarcoma | 1 | |||

| MPNST | 1.205 | 0.664 | 2.187 | 0.540 | |

| Myxofibrosarcoma | 1.208 | 0.795 | 1.836 | 0.375 | |

| Synovial Sarcoma | 1.461 | 0.888 | 2.404 | 0.136 | |

| UPS | 1.150 | 0.753 | 1.758 | 0.517 | |

| Angiosarcoma/Vascular Sarcoma | 4.729 | 2.335 | 9.580 | <0.001 | |

| Dedifferentiated/Pleomorphic Liposarcoma | 1.420 | 0.863 | 2.338 | 0.167 | |

| Leiomyosarcoma | 2.154 | 1.402 | 3.309 | <0.001 | |

| Others | 1.516 | 0.975 | 2.356 | 0.065 | |

| Neoadjuvant RTX | No | 1 | 0.007 | ||

| Yes | 1.543 | 1.127 | 2.111 | ||

| Adjuvant RTX | No | 1 | 0.296 | ||

| Yes | 1.145 | 0.888 | 1.476 | ||

| Adjuvant CTX | No | 1 | 0.022 | ||

| Yes | 0.679 | 0.488 | 0.946 | ||

| Restricted cubic spline 1 | 4.220 | 3.393 | 5.250 | <0.001 | |

| Restricted cubic spline 2 | 1.487 | 1.329 | 1.663 | <0.001 | |

| Restricted cubic spline 3 | 0.965 | 0.921 | 1.011 | 0.139 | |

| Restricted cubic spline for time-dependent effect of grading | 0.714 | 0.580 | 0.889 | 0.002 | |

| Constant | 0.050 | 0.032 | 0.078 | <0.001 | |

p-values in bold are considered statistically significant. CI = Confidence interval. RTX = radiotherapy. CTX = chemotherapy. UPS = undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma. MPNST = Malignant Peripheral Nerve Sheat Tumour.

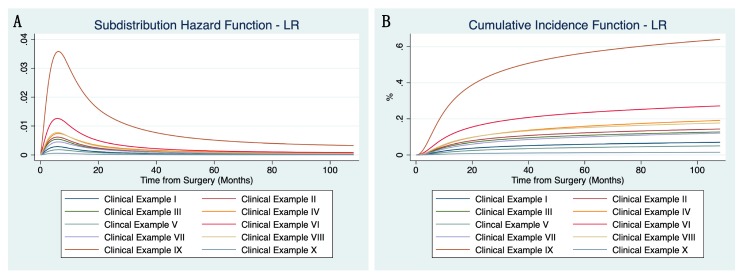

The subdistribution hazard and cumulative incidence functions for LR using ten clinical examples are shown in Figure 1A,B (definition of these examples found in Table S1, together with estimated conditional risks of LR). As an example, a male patient with a G2 myxofibrosarcoma sized 10 cm, with contaminated resection margins (R1/2), no neoadjuvant or adjuvant RTX, and no adjuvant CTX, has a significantly increased risk of developing LR, especially within the first 15 months of follow-up (=clinical example IX). On the other hand, a male patient with a 6 cm large, G3 synovial sarcoma, resected with clear margins (R0), without adjuvant CTX or (neo-)adjuvant RTX, has a moderate LR risk during the first 15 months, and an estimated low risk thereafter (=clinical example VIII).

Figure 1.

Subdistribution hazard function (A) and cumulative incidence function (B) of the flexible parametric competing risk regression model for local recurrence using ten clinical examples (constellation of parameters shown in Tables S1 and S2).

In the stepwise backward selection of the Fine and Gray model for distant metastasis (DM) histological subtype (except for myxofibrosarcoma (p = 0.641), angiosarcoma/vascular sarcoma (p = 0.067) and dedifferentiated/pleomorphic liposarcoma (p = 0.592), grading, tumor size, gender, margins, and neoadjuvant RTX (all p < 0.05) were significantly associated with development of metastases. Age (p = 0.852), adjuvant RTX (p = 0.116), neoadjuvant CTX (p = 0.095), and adjuvant CTX (p = 0.536) were excluded via stepwise backward selection. Thus, histological subtype, grading, tumor size, margins, gender, and neoadjuvant RTX were included in the flexible parametric competing risk regression model (Table 3).

Table 3.

Estimated coefficients along with their 95% confidence intervals for distant metastasis.

| Coefficient | 95%-CI | p-Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||||

| Distant Metastasis | |||||

| Gender | Male | 1 | <0.001 | ||

| Female | 0.720 | 0.605 | 0.857 | ||

| Grading | G2 | 1 | <0.001 | ||

| G3 | 1.737 | 1.412 | 2.136 | ||

| Tumor size | 1.069 | 1.056 | 1.083 | <0.001 | |

| Margins | R0 | 1 | 0.006 | ||

| R1/R2 | 1.347 | 1.087 | 1.669 | ||

| Histology | Myxoid Liposarcoma | 1 | |||

| MPNST | 1.825 | 1.158 | 2.875 | 0.009 | |

| Myxofibrosarcoma | 1.064 | 0.750 | 1.508 | 0.729 | |

| Synovial Sarcoma | 1.986 | 1.343 | 3.976 | 0.001 | |

| UPS | 1.445 | 1.033 | 2.022 | 0.032 | |

| Angiosarcoma/Vascular Sarcoma | 2.016 | 1.022 | 3.797 | 0.043 | |

| Dedifferentiated/Pleomorphic Liposarcoma | 1.209 | 0.786 | 1.861 | 0.387 | |

| Leiomyosarcoma | 2.689 | 1.900 | 3.797 | <0.001 | |

| Other | 1.835 | 1.293 | 2.604 | 0.001 | |

| Neoadjuvant RTX | No | 1 | 0.005 | ||

| Yes | 1.351 | 1.097 | 1.663 | ||

| Restricted cubic spline 1 | 2.928 | 2.591 | 3.308 | <0.001 | |

| Restricted cubic spline 2 | 1.458 | 1.374 | 1.547 | <0.001 | |

| Restricted cubic spline 3 | 0.965 | 0.926 | 1.006 | 0.096 | |

| Restricted cubic spline 4 | 1.040 | 1.020 | 1.062 | <0.001 | |

| Restricted cubic spline 5 | 0.995 | 0.982 | 1.008 | 0.427 | |

| Restricted cubic spline for time-dependent effect of grading | 0.723 | 0.640 | 0.817 | <0.001 | |

| Constant | 0.108 | 0.078 | 0.149 | <0.001 | |

| Death | |||||

| Gender | Male | 1 | 0.864 | ||

| Female | 0.968 | 0.666 | 1.407 | ||

| Grading | G2 | 1 | 0.018 | ||

| G3 | 1.873 | 1.116 | 3.145 | ||

| Tumor size | 1.023 | 0.997 | 1.050 | 0.087 | |

| Margins | R0 | 1 | 0.198 | ||

| R1/R2 | 1.378 | 0.846 | 2.244 | ||

| Histology | Myxoid Liposarcoma | 1 | |||

| MPNST | 2.506 | 0.844 | 7.442 | 0.098 | |

| Myxofibrosarcoma | 3.136 | 1.325 | 7.418 | 0.009 | |

| Synovial Sarcoma | 0.600 | 0.150 | 2.416 | 0.472 | |

| UPS | 1.781 | 0.714 | 4.443 | 0.216 | |

| Angiosarcoma/Vascular Sarcoma | 11.165 * | 3.507 * | 35.542 * | <0.001 * | |

| Dedifferentiated/Pleomorphic Liposarcoma | 3.331 | 1.259 | 8.812 | 0.015 | |

| Leiomyosarcoma | 1.798 | 0.675 | 4.782 | 0.241 | |

| Other | 2.408 | 0.963 | 4.782 | 0.060 | |

| Neoadjuvant RTX | No | 1 | 0.048 | ||

| Yes | 0.541 | 0.295 | 0.993 | ||

| Restricted cubic spline 1 | 3.604 | 2.494 | 5.211 | <0.001 | |

| Restricted cubic spline 2 | 1.270 | 1.060 | 1.523 | 0.010 | |

| Restricted cubic spline 3 | 0.952 | 0.863 | 1.049 | 0.316 | |

| Restricted cubic spline 4 | 0.953 | 0.908 | 1.001 | 0.057 | |

| Restricted cubic spline 5 | 0.974 | 0.569 | 1.199 | 0.097 | |

| Restricted cubic spline for time-dependent effect of grading | 0.826 | 0.569 | 1.199 | 0.314 | |

| Constant | 0.010 | 0.004 | 0.025 | <0.001 | |

p-values in bold are considered statistically significant; CI = Confidence interval. RTX = radiotherapy. CTX = chemotherapy. UPS = undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma. * too few events.

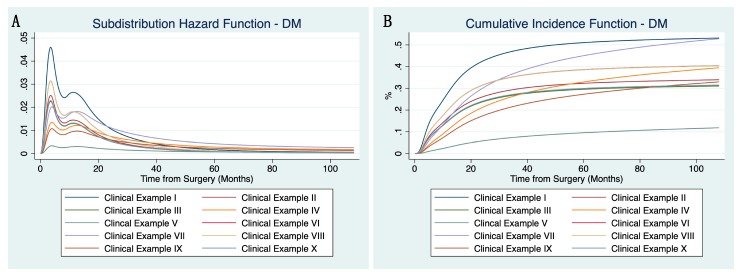

In Figure 2A,B, subdistribution hazard and cumulative incidence functions for DM (using the same ten clinical examples as in Figure 1A,B) are shown. Once again referring to clinical examples IX (male, myxofibrosarcoma, G2, 10 cm, R1/2-margins, no neoadjuvant RTX) and VIII (male, synovial sarcoma, G3, 6cm, R0-margins, no neoadjuvant RTX), risk of DM is lower in clinical example IX in comparison to clinical example VI, while LR-risks are just the opposite, highlighting the importance of an individualized follow-up strategy.

Figure 2.

Subdistribution hazard function (A) and cumulative incidence function (B) of the flexible parametric competing risk regression model for distant metastasis using the same ten clinical examples as in Figure 1A,B (constellation of parameters shown in Tables S1 and S2).

The conditional risks of these ten clinical examples changing over time estimated based on the models presented above are provided in Table S1 for LR and Table S2 for DM. Conditional risks for all possible combinations of prognostic factors may be estimated and have been implemented in the updated version of the PERSARC app.

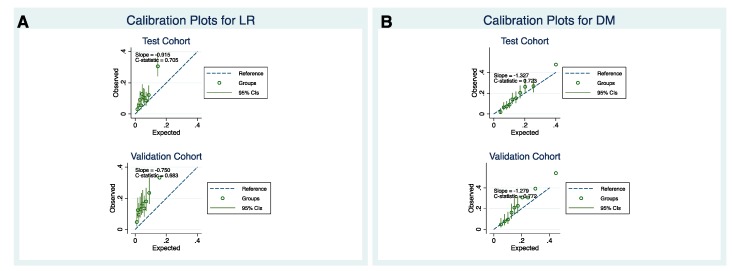

The Harrell C index for LR was equal to 0.705 and 0.683 for the internal and external cohort, respectively. For DM, Harrell C statistics was equal to 0.723 for the internal cohort and 0.772 for the external cohort. Calibration plots for LR (Figure 3A) using test and validation cohort showed that the LR model tended to underestimate the actual patient risk, especially in the validation cohort. On the other hand, calibration plots for DM with test and validation cohort (Figure 3B) showed very good model calibration.

Figure 3.

Calibration plots for the flexible parametric competing risk regression model regarding local recurrence (A) and distant metastasis (B) for the test (top) and validation cohort (bottom).

3. Discussion

In the present retrospective multicenter cohort study, flexible parametric competing risk regression modeling was applied in order to estimate individual three-to-six-month risks for local recurrence and distant metastasis during the first 5 years of follow-up in patients undergoing curative resection for high-grade extremity soft tissue sarcoma. It offers an evidence-based opportunity to individually schedule follow-up visits instead of adhering to calendar-based guidelines [8,9]. The number of radiological investigations for assessing disease status, especially after R0 resections and taking histological subtype into account, could be significantly restricted, reducing patient- and healthcare burden. The advantage of using flexible parametric competing risk regression models to estimate LR- and DM-risks in eSTS-patients is based on the fact that these rates strongly vary upon time (i.e., they do not constantly increase or decrease). To overcome this issue, flexible parametric competing risk regression models represent the baseline distribution function as a restricted cubic spline function of log time instead of a linear function of log time [15]. Moreover, it allows smooth estimation of both the cause-specific hazard rates and cumulative incidence functions. Both models performed well at internal and external calibration, with c-indexes comparable to previously published studies [14,16].

One of the limitations of the present study is its retrospective design, resulting in possible selection biases regarding diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up of patients included, due to slightly differing policies at the respective centers. By incorporating these factors in the statistical models, we aimed at reducing this bias. Moreover, during the study period, several histological STS-subtypes were reclassified (i.e., malignant fibrous histiocytoma to undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma). At some, but not all, participating centers, all histological diagnoses had been reevaluated by pathologists and, if applicable, reclassified according to the current classification systems. In order to limit the impact of this limitation, we only included patients treated in tertiary reference sarcoma centers with experienced and dedicated sarcoma pathologists.

Another limitation of the present study is that the models were developed based on patient cohorts from experienced, tertiary tumor centers. This implies that generalizability of the predicted risks to patients not treated at such centers has to be questioned. Moreover, considering that we did only include patients with high-grade (G2/3), primary eSTS who had undergone surgery with curative intent, the risks estimated are not applicable to patients with low-grade disease or metastases at initial presentation. Furthermore, estimated risks of the current models should be applied with caution after patients have already developed an event (i.e., LR or DM) during follow-up. Due to the retrospective design of the study, not all variables could be ascertained in every patient, thus potentially reducing the statistical power. However, it can be assumed that in this large patient collective, missing data may have little to no bias to the conclusions made, wherefore cases with missing information on clinical and/or pathological variables were not excluded [17].

As outlined in the introduction, current follow-up strategies follow a heuristic approach, with 3- to 4-months intervals for the first three years, followed by biannual check-ups until the end of the 5th year and annual appointments thereafter [8,9].

In clinical practice, it is not only of interest to estimate a patient’s cumulative risk after a specific period of time but also to know about the conditional risks from one follow-up appointment to the next, in case no event had occurred. We addressed this question by calculating conditional risks for LR and DM depending on different, clinically relevant, examples. Notably, the present model allows risk prediction at any constellation of variables, which are at the moment included in the updated PERSARC app. This app allows the patient’s individualized risk of LR and DM to be estimated by entering relevant prognostic parameters, such as histological subtype, tumor size, and resection margins. With the estimated event-risk in time, physicians and patients may decide together when the next follow-up examination should be scheduled. In light of the heterogeneity of eSTS with part significantly differing outcomes, estimated event risks would facilitate planning of an individualized follow-up protocol for each patient.

Arbitrary thresholds of 4% for LR and 2% for DM were chosen in the present study to be of clinical “relevance”, considering that LR is usually detected during clinical examination or even noticed by patients themselves, while DM (most commonly to the lungs) require visualization by chest x-ray or thoraci computed tomography (CT) scan [18,19]. However, thresholds should be changed on patients’ preference and clinical significance.

Previously published studies have well-investigated risks of LR, DM, and overall survival (OS) in large, retrospective cohorts of patients with eSTS [14,16,20,21]. The nomogram for OS by Kattan et al. [21] in 2002 and the two more recent nomograms for DM and OS by Callegaro et al. [16] published in 2016 added significant value to predict individual patient risks. Both studies used Cox-regression models as the basis for their nomograms. In comparison to Cox-regression models, flexible parametric competing risk regression models have a major advantage; while the Cox-regression models only estimate the relative effects (i.e., hazard rates), flexible parametric competing risk regression models estimate the baseline hazard using restricted cubic splines [22]. The cumulative incidence functions of LR and DM predicted from flexible parametric competing risk regression models demonstrate the clear variance in event rates. By applying a flexible parametric competing risk regression model, we aimed at incorporating non-constant hazards, time-varying covariates, and death as the competing event in order to obtain a robust, comprehensible, and accurate prediction of individual patient risks. Moreover, with the clinical examples provided, the risk peaks during the first year of follow-up is clearly visible. Although appointments may be safely skipped in some patients due to very low risks of LR and/or DM, others would benefit from closer follow-up intervals.

Potentially due to the application of the present statistical model, interesting results emerged: Female gender was independently associated with a significantly lower risk of LR and DM. An association between gender and overall survival (OS) has been observed by Maretty-Nielsen et al. and Wu et al. [2,23]. However, an association between gender and LR-free as well as DM-free survival has not been described thus far [24]. Moreover, tumor grading, which is a well-known prognostic factor of LR, was not significantly associated with an altered risk in the current flexible parametric competing risk regression model. This may be explained by the fact that patients with usually fast-growing, highly-aggressive G3 tumors will present with LR at early time points, while in those with relatively slower-growing G2 tumors, LR is most probably detected at a later date. This hypothesis is corroborated by the fact that grading did not meet the proportional hazards assumption, wherefore it was treated as a time-varying covariate. On the other hand, another recently published multicenter study for grade III eSTS did not incorporate grade II in the multivariate model for OS [14]. The current model has broader applicability as it also incorporates patients with grade II eSTS. Additionally, margins as classified in the current study only divide “clear” from “contaminated” margins, not taking into consideration that histological subtypes with infiltrative growth pattern as undifferentiated pleiomorphic sarcoma (UPS) and myxofibrosarcoma potentially require broader margins to markedly reduce LR-risk [25]. Thus, unsurprisingly, also in the current flexible parametric competing risk regression model for LR, these histological subtypes showed significantly higher LR-risks in comparison to other histologies.

4. Materials and Methods

In this retrospective multicenter study, 1931 consecutive patients with primary nonmetastatic high-grade (G2/3) eSTS managed with surgery at a curative intent were included in the test cohort, with patient information deriving from prospectively maintained STS databases at 5 participating tertiary sarcoma referral centers. Patients with missing information on oncological follow-up (i.e., development of LR/DM) had to be excluded (n = 42). Extremity STS were defined as tumors from the shoulder to the fingers (=upper limb) and from the pelvic girdle, excluding intrapelvic STS, to the foot (=lower limb). The validation cohort consisted of 1085 patients with identical inclusion criteria as for the test cohort from two independent tertiary sarcoma referral centers. As described above, patient monitoring after surgery usually followed a standardized approach with clinical examination, radiography using chest X-ray (CXR) or chest CT-scan (chest-CT) for control of DM and sonography or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) for control of LR.

Demographic variables (patient age at diagnosis, gender), tumor-related parameters (tumor size, depth, location, grading, histological subtype), treatment (histological margins, (neo)adjuvant CTX/RTX), and outcome variables (date of LR or DM, date of death/last follow-up) were reported. Histological resection margins were divided into “clear” margins (=R0) and “contaminated” margins (=R1/2), as classification and definition of margin status have changed over time [26,27,28]. Histological subtypes were classified into 9 categories, with myxoid liposarcoma as the reference, compliant with previous studies and the current World Health Organisation (WHO) classification (Table 1) [6,16]. The FNCLCC grading system (Fédération Française des Centres de Lutte Contre le Cancer/French Federation of Centres for the Fight against Cancer) was used to categorize tumors into either intermediate (=G2) or high-grade (G3) [29]. (Neo-)adjuvant RTX and CTX had been administered in case a high risk of LR or DM had been anticipated by the multidisciplinary tumor board, according to locally preferred guidelines, LR was defined as a radiologically and/or histologically confirmed tumor recurrence. DM must have been confirmed by radiography (sonography, MRI, CXR, chest-CT) and/or histologically. In the case of pulmonary nodules without subsequent surgical exploration, an increase in size of the suspected metastasis must have been present. Patient, tumor, and treatment-related factors were ascertained using medical records, histological reports, and prospectively maintained databases at the respective centers.

Ethics approval was obtained in each participating center. The study was performed according to the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Medical University of Graz, Austria (IRB-approval-number: 31-046 ex 18/19; date of approval: 24 May 2019).

Statistical Analysis

We focused on the first five years of follow-up to predict the conditional risk at the usually scheduled follow-up times (every 3 months from 1st to 3rd year; every 6 months in 4th and 5th year), i.e., the risk of experiencing an event at X + Y, given that the patient has not developed an event before X months. The variables age and tumor size were centered at their mean value in order to allow prediction at the average in case variables were not specified upon calculation. We used the Royston and Parmar approach to fit a flexible parametric competing risk regression model in order to estimate the risk of LR and DM, with death as the competing event [30]. In this model, the baseline distribution is modeled as a restricted cubic spline function of log time [15,22]. Splines constitute flexible mathematical functions defined by piecewise polynomials together with distinct constraints, ensuring that the overall curve is smooth [22]. A feature of restricted cubic splines as used in the present model is that the fitted function is forced to be linear before the first and after the last knot [31]. As automatic stepwise backward selection of variables is currently not available for the flexible parametric competing risk regression model, variable selection for the LR and DM models was based on a stepwise backward procedure using a multivariable Fine and Gray model [32]. Variables with a p-value < 0.05 were excluded from the model, except for histology, where all subtypes were kept in the analyses. The LR and DM models were fit on the log cumulative subdistribution hazard scale, directly modeling the cause-specific cumulative incidence function. Grading was incorporated in the model as a time-dependent effect for LR and DM, as it did not meet the proportional hazards assumption. The number of knots of the flexible parametric competing risk regression model for LR and DM was chosen based on the lowest AIC (=Akaike Information Criterion) after fitting several models with knots from 0 to 5. For the flexible parametric competing risk regression model estimating the risk of LR, two knots turned out as most accurate, while for the model predicting the risk of DM, four knots were used (with no internal knots for grading as a time-dependent covariate). Cumulative incidence functions were estimated based on the defined models. Conditional risks at the 3–6-months intervals were calculated based on the cumulative incidence functions of the flexible parametric competing risk regression model. Threshold was set to 4% for LR, considering that they are often palpable and diagnosed during the clinical examination or by patients themselves [18]. On the other hand, a 2% threshold for DM was chosen, as DM (and most commonly lung metastases) can only safely be diagnosed by chest X-ray or CT-scans of the thorax [19]. Model discrimination was tested using the Harrell C index, estimating the probability of concordance between observed and predicted outcomes. A value of 0.5 indicates no predictive discrimination, while a value of 1.0 indicates a perfect separation of patients with different outcomes [33]. Furthermore, calibration plots were compiled to assess model calibration in the test and validation cohort.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, the present study provides a model to individually predict patient’s LR and DM risks during follow-up, applying a flexible parametric competing risk regression approach. These models are at the moment being included in the updated version of the PERSARC app for Individualized Sarcoma Care and follow-up. Although a risk-threshold of 4% for LR and 2% for DM was chosen in the present study, the “optimal” threshold upon which an individual patient should undergo imaging with MRI, chest-CT, or CXR, is still subjected to experts’ opinion and should be further discussed with patients concerned.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/2072-6694/12/1/47/s1, Table S1: Conditional Risks for Local Recurrence–Threshold 4%; Table S2: Conditional Risks for Distant Metastasis–Threshold 2%.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.A.S., A.L., R.L.H., and J.S. (Joanna Szkandera); data curation, M.A.S., D.C., J.W., A.H., L.L., M.B., P.-U.T., V.v.P., M.F., J.P., M.W., R.W., S.P.D.D., W.J.v.H., J.M.R., M.S., A.G. (Armin Gerger), M.P., H.S., B.L.-A., D.A., and A.G. (Alessandro Gronchi); formal analysis, J.S. (Josef Smolle); investigation, D.C., J.W., A.H., L.L., M.B., P.-U.T., V.v.P., J.P., M.W., R.W., S.D., W.J.v.H., J.M.R., M.S., A.G. (Alessandro Gronchi), M.P., H.S., B.L.-A., and A.G. (Armin Gerger); methodology, M.v.d.S., M.F., S.D., J.S. (Josef Smolle), R.L.H., and J.S. (Joanna Szkandera); project administration, M.v.d.S., A.L., R.L.H., and J.S. (Joanna Szkandera); supervision, M.v.d.S., D.A., and R.L.H.; validation, V.v.P., M.F., D.A. and J.S. (Joanna Szkandera); visualization, M.A.S. and J.S. (Josef Smolle); writing—Original draft, M.A.S., M.v.d.S., A.L., R.L.H., and J.S. (Joanna Szkandera); writing—Review and editing, D.C., J.W., A.H., L.L., M.B., P.-U.T., V.v.P., J.P., M.W., R.W., S.P.D.D., W.J.v.H., J.M.R., M.S., A.G. (Armin Gerger), M.P., H.S., B.L.-A., D.A., and A.G. (Alessandro Gronchi). All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Dutch Cancer Society (DCS)—KWF Kankerbestrijding [UL2015-8028]. The funding source had no role in the design of this study; execution, analyses, and interpretation of the data; report writing; or decision to submit the article for publication.

Conflicts of Interest

Author van de Sande reports grants from Daiichi Sankyo, outside the submitted work. The remaining authors (Maria A Smolle, Dario Callegaro, Jay Wunder, Andrew J. Hayes, Lukas Leitner, Marko Bergovec, Per-Ulf Tunn, Veroniek van Praag, Marta Fiocco, Joannis Panotopoulos, Madeleine Willegger, Reinhard Windhager, Sander Djikstra, Winan J van Houdt, Jakob M Riedl, Michael Stotz, Armin Gerger, Martin Pichler, Herbert Stöger, Bernadette Liegl-Atzwanger, Josef Smolle, Dimosthenis Andreou, Andreas Leithner, Alessandro Gronchi, Rick L. Haas, and Joanna Szkandera) have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Italiano A., Le Cesne A., Mendiboure J., Blay J.Y., Piperno-Neumann S., Chevreau C., Delcambre C., Penel N., Terrier P., Ranchere-Vince D., et al. Prognostic factors and impact of adjuvant treatments on local and metastatic relapse of soft-tissue sarcoma patients in the competing risks setting. Cancer. 2014;120:3361–3369. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maretty-Nielsen K., Aggerholm-Pedersen N., Safwat A., Jorgensen P.H., Hansen B.H., Baerentzen S., Pedersen A.B., Keller J. Prognostic factors for local recurrence and mortality in adult soft tissue sarcoma of the extremities and trunk wall: A cohort study of 922 consecutive patients. Acta Orthop. 2014;85:323–332. doi: 10.3109/17453674.2014.908341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Novais E.N., Demiralp B., Alderete J., Larson M.C., Rose P.S., Sim F.H. Do surgical margin and local recurrence influence survival in soft tissue sarcomas? Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2010;468:3003–3011. doi: 10.1007/s11999-010-1471-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Willeumier J., Fiocco M., Nout R., Dijkstra S., Aston W., Pollock R., Hartgrink H., Bovee J., van de Sande M. High-grade soft tissue sarcomas of the extremities: Surgical margins influence only local recurrence not overall survival. Int. Orthop. 2015;39:935–941. doi: 10.1007/s00264-015-2694-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Singer S., Demetri G.D., Baldini E.H., Fletcher C.D. Management of soft-tissue sarcomas: An overview and update. Lancet Oncol. 2000;1:75–85. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(00)00016-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fletcher C.D., Bridge J.A., Hodgendoorn P.C.W., Mertens F. WHO Classification of Tumours of Soft Tissue and Bone. IARC; Lyon, France: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smolle M.A., van Praag V.M., Posch F., Bergovec M., Leitner L., Friesenbichler J., Heregger R., Riedl J.M., Pichler M., Gerger A., et al. Surgery for metachronous metastasis of soft tissue sarcoma—A magnitude of benefit analysis using propensity score methods. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 2018;45:242–248. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2018.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Casali P.G., Abecassis N., Bauer S., Biagini R., Bielack S., Bonvalot S., Boukovinas I., Bovee J., Brodowicz T., Broto J.M., et al. Soft tissue and visceral sarcomas: ESMO-EURACAN Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann. Oncol. 2018;29:iv51–iv67. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdy096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.von Mehren M., Randall R.L., Benjamin R.S., Boles S., Bui M.M., Ganjoo K.N., George S., Gonzalez R.J., Heslin M.J., Kane J.M., 3rd, et al. Soft Tissue Sarcoma, Version 2.2018, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J. Natl. Compr. Cancer Netw. 2018;16:536–563. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2018.0025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gingrich A.A., Bateni S.B., Monjazeb A.M., Darrow M.A., Thorpe S.W., Kirane A.R., Bold R.J., Canter R.J. Neoadjuvant Radiotherapy is Associated with R0 Resection and Improved Survival for Patients with Extremity Soft Tissue Sarcoma Undergoing Surgery: A National Cancer Database Analysis. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2017;24:3252–3263. doi: 10.1245/s10434-017-6019-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gronchi A., Ferrari S., Quagliuolo V., Broto J.M., Pousa A.L., Grignani G., Basso U., Blay J.Y., Tendero O., Beveridge R.D., et al. Histotype-tailored neoadjuvant chemotherapy versus standard chemotherapy in patients with high-risk soft-tissue sarcomas (ISG-STS 1001): An international, open-label, randomised, controlled, phase 3, multicentre trial. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18:812–822. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(17)30334-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Posch F., Partl R., Doller C., Riedl J.M., Smolle M., Leitner L., Bergovec M., Liegl-Atzwanger B., Stotz M., Bezan A., et al. Benefit of Adjuvant Radiotherapy for Local Control, Distant Metastasis, and Survival Outcomes in Patients with Localized Soft Tissue Sarcoma: Comparative Effectiveness Analysis of an Observational Cohort Study. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2018;25:776–783. doi: 10.1245/s10434-017-6080-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Royce T.J., Punglia R.S., Chen A.B., Patel S.A., Thornton K.A., Raut C.P., Baldini E.H. Cost-Effectiveness of Surveillance for Distant Recurrence in Extremity Soft Tissue Sarcoma. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2017;24:3264–3270. doi: 10.1245/s10434-017-5996-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.van Praag V.M., Rueten-Budde A.J., Jeys L.M., Laitinen M.K., Pollock R., Aston W., van der Hage J.A., Dijkstra P.D.S., Ferguson P.C., Griffin A.M., et al. A prediction model for treatment decisions in high-grade extremity soft-tissue sarcomas: Personalised sarcoma care (PERSARC) Eur. J. Cancer. 2017;83:313–323. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2017.06.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Royston P., Lambert P.C. Flexible Parametric Survival Analysis Using Stata: Beyond the Cox Model. Stata Press; College Statoin, TX, USA: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Callegaro D., Miceli R., Bonvalot S., Ferguson P., Strauss D.C., Levy A., Griffin A., Hayes A.J., Stacchiotti S., Pechoux C.L., et al. Development and external validation of two nomograms to predict overall survival and occurrence of distant metastases in adults after surgical resection of localised soft-tissue sarcomas of the extremities: A retrospective analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17:671–680. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(16)00010-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kang H. The prevention and handling of the missing data. Korean J. Anesthesiol. 2013;64:402–406. doi: 10.4097/kjae.2013.64.5.402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Puri A., Ranganathan P., Gulia A., Crasto S., Hawaldar R., Badwe R.A. Does a less intensive surveillance protocol affect the survival of patients after treatment of a sarcoma of the limb? updated results of the randomized TOSS study. Bone Jt. J. 2018;100-B:262–268. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.100B2.BJJ-2017-0789.R1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hovgaard T.B., Nymark T., Skov O., Petersen M.M. Follow-up after initial surgical treatment of soft tissue sarcomas in the extremities and trunk wall. Acta Oncol. 2017;56:1004–1012. doi: 10.1080/0284186X.2017.1299937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rueten-Budde A.J., van Praag V.M., PERSARC studygroup. van de Sande M.A.J., Fiocco M. Dynamic prediction of overall survival for patients with high-grade extremity soft tissue sarcoma. Surg. Oncol. 2018;27:695–701. doi: 10.1016/j.suronc.2018.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kattan M.W., Leung D.H., Brennan M.F. Postoperative nomogram for 12-year sarcoma-specific death. J. Clin. Oncol. 2002;20:791–796. doi: 10.1200/JCO.20.3.791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lambert P.C., Royston P. Further development of flexible parametric models for survival analysis. Stata J. 2009;9:265–290. doi: 10.1177/1536867X0900900206. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wu J., Qian S., Jin L. Prognostic factors of patients with extremity myxoid liposarcomas after surgery. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 2019;14:90. doi: 10.1186/s13018-019-1120-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Trovik C.S., Bauer H.C., Alvegard T.A., Anderson H., Blomqvist C., Berlin O., Gustafson P., Saeter G., Walloe A. Surgical margins, local recurrence and metastasis in soft tissue sarcomas: 559 surgically-treated patients from the Scandinavian Sarcoma Group Register. Eur. J. Cancer. 2000;36:710–716. doi: 10.1016/S0959-8049(99)00287-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fujiwara T., Stevenson J., Parry M., Tsuda Y., Tsoi K., Jeys L. What is an adequate margin for infiltrative soft-tissue sarcomas? Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 2019 doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2019.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kainhofer V., Smolle M.A., Szkandera J., Liegl-Atzwanger B., Maurer-Ertl W., Gerger A., Riedl J., Leithner A. The width of resection margins influences local recurrence in soft tissue sarcoma patients. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 2016;42:899–906. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2016.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tunn P.U., Kettelhack C., Durr H.R. Standardized approach to the treatment of adult soft tissue sarcoma of the extremities. Recent Results Cancer Res. 2009;179:211–228. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-77960-5_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wittekind C., Compton C.C., Greene F.L., Sobin L.H. TNM residual tumor classification revisited. Cancer. 2002;94:2511–2516. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Trojani M., Contesso G., Coindre J.M., Rouesse J., Bui N.B., de Mascarel A., Goussot J.F., David M., Bonichon F., Lagarde C. Soft-tissue sarcomas of adults; study of pathological prognostic variables and definition of a histopathological grading system. Int. J. Cancer. 1984;33:37–42. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910330108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mozumder S.I., Rutherford M.J., Lambert P.C. stpm2cr: A flexible parametric competing risks model using a direct likelihood approach for the cause-specific cumulative incidence function. Stata J. 2017;17:462–489. doi: 10.1177/1536867X1701700212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Durrleman S., Simon R. Flexible regression models with cubic splines. Stat. Med. 1989;8:551–561. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780080504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fine J.P., Gray R.J. A proportional hazards model for the subdistribution of a competing risk. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1999;94:496–509. doi: 10.1080/01621459.1999.10474144. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Harrell F.E., Jr., Lee K.L., Mark D.B. Multivariable prognostic models: Issues in developing models, evaluating assumptions and adequacy, and measuring and reducing errors. Stat. Med. 1996;15:361–387. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0258(19960229)15:4<361::AID-SIM168>3.0.CO;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.