Abstract

Vibrio cholerae, the causative agent of the severe diarrheal disease cholera, has evolved signal transduction systems to control the expression of virulence determinants. It was previously shown that two cysteine residues in the periplasmic domain of TcpP are important for TcpP dimerization and activation of virulence gene expression by responding to environmental signals in the small intestine such as bile salts. In the cytoplasmic domain of TcpP, there are another four cysteine residues, C19, C51, C58, and C124. In this study, the functions of these four cysteine residues were investigated and we found that only C58 is essential for TcpP dimerization and for activating virulence gene expression. To better characterize this cysteine residue, site-directed mutagenesis was performed to assess the effects on TcpP homodimerization and virulence gene activation. A TcpPC58S mutant was unable to form homodimers and activate virulence gene expression, and did not colonize infant mice. However, a TcpPC19/51/124S mutant was not attenuated for virulence. These results suggest that C58 of TcpP is indispensable for TcpP function and is essential for V. cholerae virulence factor production and pathogenesis.

Keywords: Vibrio cholerae, TcpP, cysteine residue, virulence gene regulation, pathogenesis

Introduction

Vibrio cholerae is a Gram-negative, facultative human pathogen and is the causative agent of cholera. The Vibrio life cycle begins with a free swimming phase in aquatic environments. Upon oral ingestion, V. cholerae passages through the stomach to reach the small intestine, its primary site of colonization. During its life cycle, V. cholerae changes its transcriptional profile in different environmental niches to facilitate survival and colonization fitness (Zhu and Mekalanos, 2003; Moorthy and Watnick, 2005; Matson et al., 2007; Nielsen et al., 2010; Mandlik et al., 2011). During the early infection, in vivo virulence gene expression is induced by a number of host signals, including anoxic environment and chemicals present in the small intestine (Kovacikova et al., 2010; Yang et al., 2013; Fan et al., 2014; Hay et al., 2017; Midgett et al., 2017). In late infection stages, virulence genes are repressed and a coordinated “escape response” allows the organism to detach from the intestinal surface in preparation for exit from the host (Larocque et al., 2005; Nielsen et al., 2006, 2010).

The membrane-bound transcriptional regulator TcpP plays a critical role in V. cholerae virulence. A TcpP partner protein, TcpH, stabilizes TcpP and enhances its activity (Krukonis et al., 2000; Crawford et al., 2003; Beck et al., 2004). TcpP, in conjugation with ToxR, activates the transcription of toxT, the master regulator of numerous virulence factors in V. cholerae (Krukonis et al., 2000; Krukonis and DiRita, 2003; Haas et al., 2015). The two cysteine residues in the periplasmic domain of TcpP are critical for its activation of toxT (Yang et al., 2013; Morgan et al., 2016; Xue et al., 2016). Intermolecular disulfide bond formation in TcpP results in homodimerization and the activation of virulence gene expression (Yang et al., 2013). And the formation of intramolecular disulfide bond in TcpP enhances the stability of TcpP (Morgan et al., 2016). There are another four cysteine residues in the cytoplasmic domain of TcpP, the functions of which are under investigation. The sulfur atom in the cysteine is strategically positioned in some regulatory proteins to function as a sensor of reactive oxygen species (ROS) or reactive nitrogen species (RNS) (Vazquez-Torres, 2012). AphB, the transcriptional activator of TcpP in V. cholerae, apply the signaling properties of thiol switches to regulate virulence and ROS relevant genes expression to increase the fitness of V. cholerae during its life cycle (Liu et al., 2011, 2016a,b). A growing number of Gram-positive and Gram-negative pathogens are now known to apply the signaling properties of thiol switches in order to increase fitness during their associations with vertebrate hosts (Vazquez-Torres, 2012).

The transmembrane protein TcpP contains four cysteines in the cytoplasmic domain which may play roles in regulating virulence gene expression in V. cholerae. We mutated one of these cysteines, C58, to serine and found that this TcpP mutant cannot homodimerize and loses transcriptional activation activity. Here we further investigated the role of TcpP C58 in the context of V. cholerae infection.

Materials and Methods

Bacterial Strains, Plasmids and Growth Conditions

Strains, plasmids, and oligonucleotides used in this study are summarized in Supplementary Table S1. All V. cholerae strains used in this study were derived from E1 Tor C6706 (Joelsson et al., 2006), and were propagated in LB media containing appropriate antibiotics at 37°C unless otherwise noted. Transcriptional lux reporters of toxT promoter regions in the pBBR-lux vector (Liu et al., 2011) have been described previously (Yang et al., 2013). Plasmids for overexpressing TcpP or mutants were either described previously (Yang et al., 2013) or were constructed by cloning the PCR-amplified coding regions into pBAD24 (Guzman et al., 1995) or pACYC117 (Chang and Cohen, 1978). In-frame deletion strains used in this study were described in previous publications (Liu et al., 2011; Yang et al., 2013). TcpP truncation and chimeric mutants as well as cysteine mutations were constructed by using overlap extension PCR (Higuchi et al., 1988).

Measurement of Virulence Gene Expression and Virulence Factor Production

Overnight cultures of V. cholerae strains containing virulence promoter luxCDABE transcriptional fusions were subcultured at a dilution of 1:100 in LB with or without bile salts indicated and grown anaerobically until OD600 ≈ 0.2. Luminescence was measured using a Bio-Tek Synergy HT spectrophotometer and normalized for growth against OD600. Luminescence expression was reported as light units/OD600. TCP production was measured by Western blot analysis using an anti-TcpA polyclonal antibody (Zhu et al., 2002).

TcpP Cytoplasmic Domain Expression and Purification

The DNA fragment encoding the cytoplasmic domain of TcpP (AAs 1–135) was amplified from genomic DNA. The PCR products were inserted into a modified pET-28a vector encoding an N-terminal His6 tag. Escherichia coli BL21(DE3)/pLysS cells were transformed with the plasmid containing the target gene and transformed cells were used for protein expression by autoinduction (Thompson et al., 1994). Proteins were expressed and purified on nickel columns according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Novagen).

Gel Retardation Assay of TcpP Cytoplasmic Domain With toxT Promoter

His6 tag fused protein of TcpPcyto was expressed and purified as described above. DNA fragments of the toxT (VC0838) promoter region were generated using PCR and purified with QIAquick PCR Purification Kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. DNA (50 ng) was incubated with varying concentrations of purified protein and incubated in binding buffer (50 mM Tris–HCl, pH 8.0, 250 mM NaCl, 5.0 mM MgCl2, 2.5 mM DTT, 2.5 mM EDTA and 20% glycerol) for 30 min at room temperature. Protein-DNA complexes were separated electrophoretically on a native 5% polyacrylamide gel at 100 V in 0.5 × Tris-acetate-EDTA (TAE) buffer and visualized using ethidium bromide staining.

In vitro Redox State Determination of TcpP Cytoplasmic Domain

The in vitro redox state of TcpP cytoplasmic domain was assessed using AMS trapping experiments as (Denoncin et al., 2013). 100 ng of freshly purified TcpPcyto protein was precipitated by 10% (vol/vol) trichloroacetic acid (TCA). Precipitated proteins were washed three times with cold acetone, suspended in a buffered solution containing 100 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.5 and 1% (wt/vol) SDS, with or without 10 mg/mL AMS, and incubated in the dark at 30°C for 30 min followed by 37°C for 10 min. AMS alkylation was stopped by the addition of SDS loading buffer [2% (wt/vol) SDS, 50 mM Tris, 10% (vol/vol) Glycerol, 142 mM 2-mercaptoethanol]. Proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE, and immunoblot analyses were performed.

Bacterial Two-Hybrid System to Determine TcpP Mutant Interaction

To analyze the dimerization of TcpP mutant, β-galactosidase measurements were performed as described previously (Yang et al., 2013). Briefly, overnight cultures of E. coli BTH101 containing both pUT-18C-fusion and pKT25-fusion constructs (Karimova et al., 1998) were subcultured at a dilution of 1:100 in LB medium containing 0.5 mM isopropyl-β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside and incubated without shaking at 30°C for 8 h. Cultures were then assayed for β-galactosidase activity (Karimova et al., 1998).

Differential Thiol Trapping Assay of Disulfide Bond

The thiol/disulfide state of the cytoplasmic cysteines of TcpP was monitored in vivo by differential thiol trapping (Tetsch et al., 2011). V. choleraeΔtcpPH strains carrying the plasmid pacyc-TcpPC207/218S-cFLAG or PBAD-TcpPC58S-nFLAG were grown in LB medium to an OD600 of about 0.5. Subsequently, overproduction of the TcpP mutant-FLAG derivatives was induced by addition of 0.1% (w/v) arabinose for 5 min. Bacterial cells were collected and resuspended in PBS containing 100 mM iodoacetamide, and then incubated at 37°C with 1,300 rpm agitation for 1 h. This first alkylation procedure irreversibly modified all free thiol groups. Subsequently, cells were harvested and lysed in 1 mL ice-cold 10% (w/v) TCA and stored on ice for at least 6 h or at 4°C overnight. The TCA treated cells were centrifuged (16,000 g, 4°C, 15 min), and the resulting pellet was washed twice with 500 μl of ice-cold acetone. The supernatant was removed and the pellet was resuspended in 900 μl of 100 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.5), 1% (w/v) SDS supplemented with 50 mM DTT to reduce disulfide bonds. After 1 h of incubation in the dark (37°C, gentle agitation at 1,300 rpm), 100 μl ice-cold 100% (w/v) TCA was added, and the sample was stored on ice for at least 6 h. After centrifugation, the resulting pellet was again washed twice with 500 μl of ice-cold acetone. Finally, the pellet was resuspended in 50 μl of Tris-SDS buffer, with or without 10 mM AMS, and incubated at 30°C for 30 min followed by 37°C for 10 min. AMS alkylation was stopped by the addition of SDS loading buffer. Proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE, and immunoblot analyses were performed. TcpP was detected using a monoclonal anti-FLAG antibody(Sigma–Aldrich).

In vivo Competition Assays

All animal experiments were carried out in strict accordance with the animal protocols that were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Zhejiang A&F University (Permit Number: ZJAFU/IACUC_2011-10-25-02). Five-days-old ICR mice purchased from the animal facility of Zhejiang Academy of Medical Sciences were raised in the animal facility of Zhejiang A&F University and separated from their dams 1 h before infection. Subsequently, they were anesthetized by inhalation of isoflurane gas and then inoculated by oral gavage with 50 μL of an appropriate dilution of the 1:1 mixture (WT and mutant), resulting in an infection dose of ∼106 cfu per mouse. To determine the exact inputs, appropriate dilutions of the inocula were plated on LB-Sm/X-Gal plates. After 22 h, the mice were euthanized, and the small intestines from each mouse were collected by dissection. The small intestines were mechanically homogenized in LB broth with 15% glycerol, and appropriate dilutions were plated on LB-Sm/X-Gal. The competitive index was calculated as the ratio of mutant to wild type colonies normalized to the input ratio.

Results

TcpP C58 Is Indispensable for Activating Virulence Gene Expression

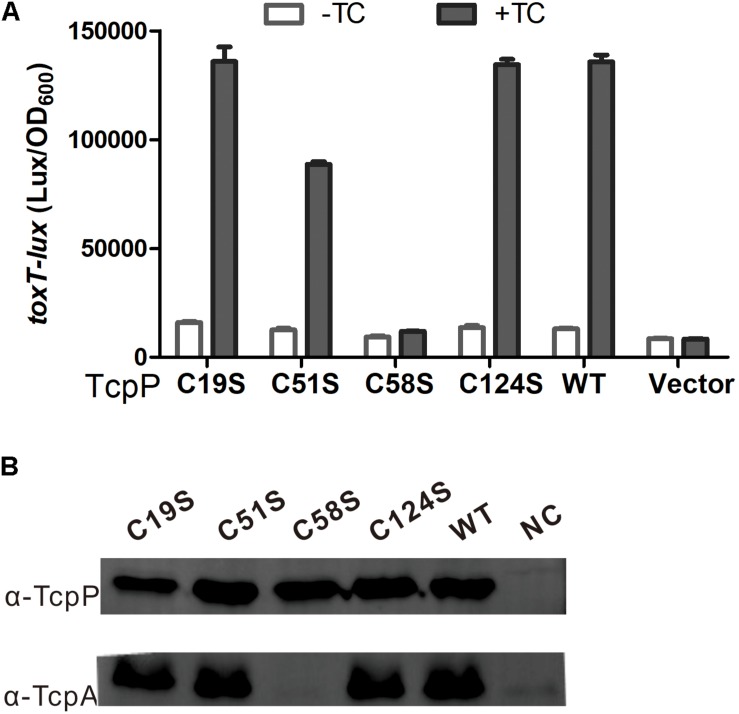

Previous studies showed that the two cysteines (C207 and C218) in the periplasmic domain of TcpP are crucial for TcpP activity (Yang et al., 2013). Bile salts induce TcpP to form an intermolecular disulfide bond between these two cysteines to dimerize by interfering with the redox potential of the Dsb proteins (Yang et al., 2013; Xue et al., 2016). In the cytoplasmic domain of TcpP, there are four additional cysteines C19, C51, C58, and C124. To study if these four cysteines are also indispensable for TcpP activity, we mutagenized these four cysteines to serines respectively and analyzed their activities by quantifying toxT transcription. We found that TcpPC19S, TcpPC51S, and TcpPC124S activated toxT expression to the same level as TcpP wild type (TcpPWT), but TcpPC58S did not (Figure 1). The TcpPC58S mutant was still localized to the bacterial membrane (Supplementary Figure S1).

FIGURE 1.

C58 is indispensable for TcpP activation of virulence gene expression. (A) V. cholerae ΔtcpP strains containing PBAD-controlled plasmids harboring TcpP or its cysteine mutant derivatives and a PtoxT-lux transcriptional fusion plasmid were grown in LB with 0.01% arabinose in the presence or absence of taurocholate acid at 37°C until OD600 ≈ 0.2. Luminescence was measured and reported as light units/OD600. Data are the means ± SD (n = 3). (B) V. choleraeΔtcpP strains containing PBAD-TcpP wild type or cysteine mutant plasmids grown in LB with 0.01% arabinose in the presence of 1 mM TC for 6 h. Cell lysates (0.1 mg) were applied to SDS-PAGE, and subjected to Western blotting using an anti-TcpP or anti-TcpA antibody.

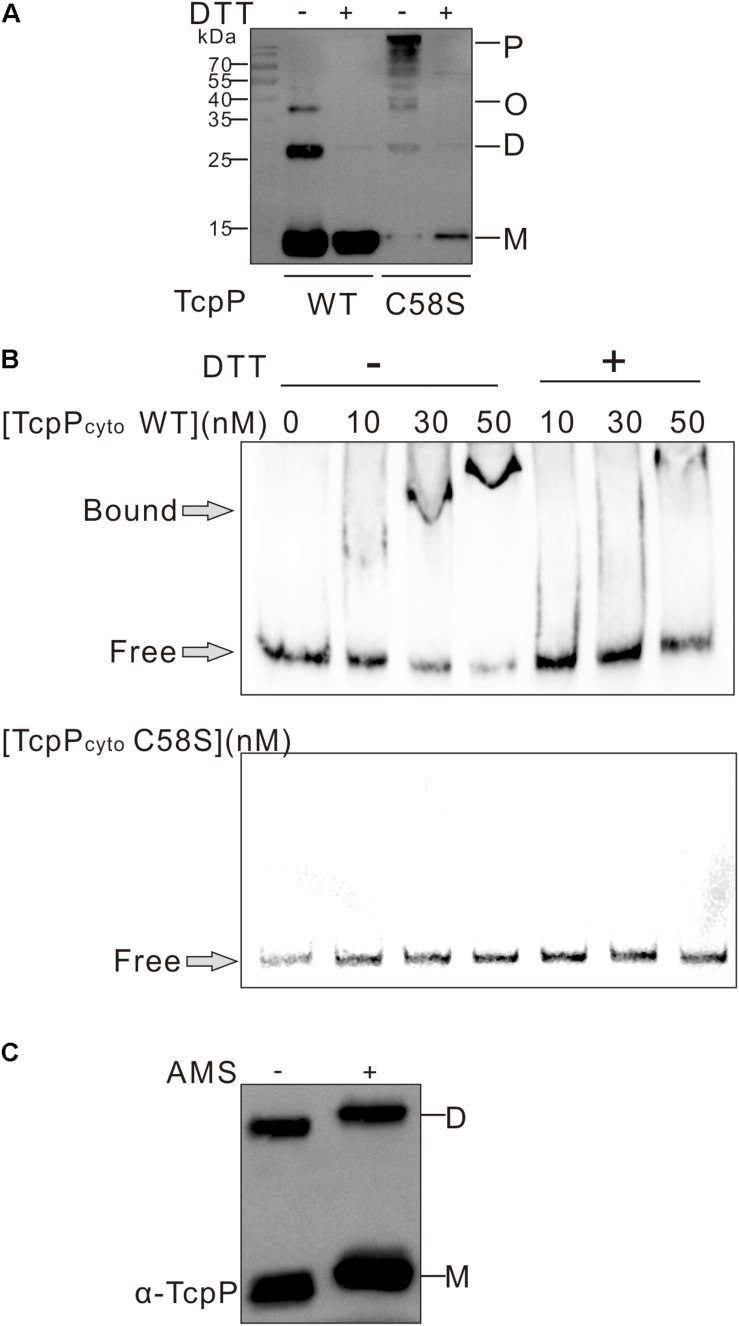

TcpPC58S Cyto-Domain Cannot Bind DNA in vitro

The cytoplasmic domain of TcpP contains an N-terminal winged helix-turn-helix (wHTH) DNA binding domain of the OmpR family (Martinez-Hackert and Stock, 1997; Krukonis and DiRita, 2003). To determine if the C58S mutation affects TcpP binding to DNA, we performed gel retardation assays of TcpPcyto WT or TcpPcyto C58S, which each contain the N-terminal 135 amino acids of TcpP. Both the cytoplasmic domain of TcpPcyto WT and TcpPcyto C58S could be expressed and purified as soluble protein. However, sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) of these two purified proteins showed that under non-reducing conditions, TcpPcyto C58S formed oligomers or polymers, while TcpPcyto WT mainly exists as monomer or dimer (Figure 2A). Under non-reducing conditions TcpPcyto WT bound toxT promoter DNA as a function of increasing protein concentrations, while TcpPcyto C58S did not bind DNA under the same conditions (Figure 2B).

FIGURE 2.

TcpP cytoplasmic domain binding to DNA in vitro. (A) The cytoplasmic domain of TcpP WT or C58S including the first 135 amino acids of the N termini was purified under non-reducing conditions. Proteins treated with (+) or without (–) DTT were separated using SDS-PAGE and subjected to Western blotting using an anti-TcpP antibody. P, polymer; O, oligomer; D, dimer; M, monomer. (B) Gel shift assays using purified TcpPcyto WT or C58S and DNA containing ∼400 bp of the regulatory regions identified in toxT promoter. (C) Free thiol group assay of TcpPcyto WT protein by AMS trapping. One hundred ng of protein was precipitated using 10% TCA and proteins containing free thiol groups were trapped with AMS. TcpPcyto was detected by Western blot using anti-TcpP antibody.

The lack of DNA binding by TcpPcyto C58S suggested that TcpPcyto binding to DNA requires disulfide bond formation. By analyzing the redox status TcpPcyto WT, we found that TcpPcyto WT is not totally oxidized but still contains free thiol groups either in the monomer or the dimer form of the protein (Figure 2C). This might indicate that proper disulfide bond forming could help TcpPcyto WT folding and DNA binding.

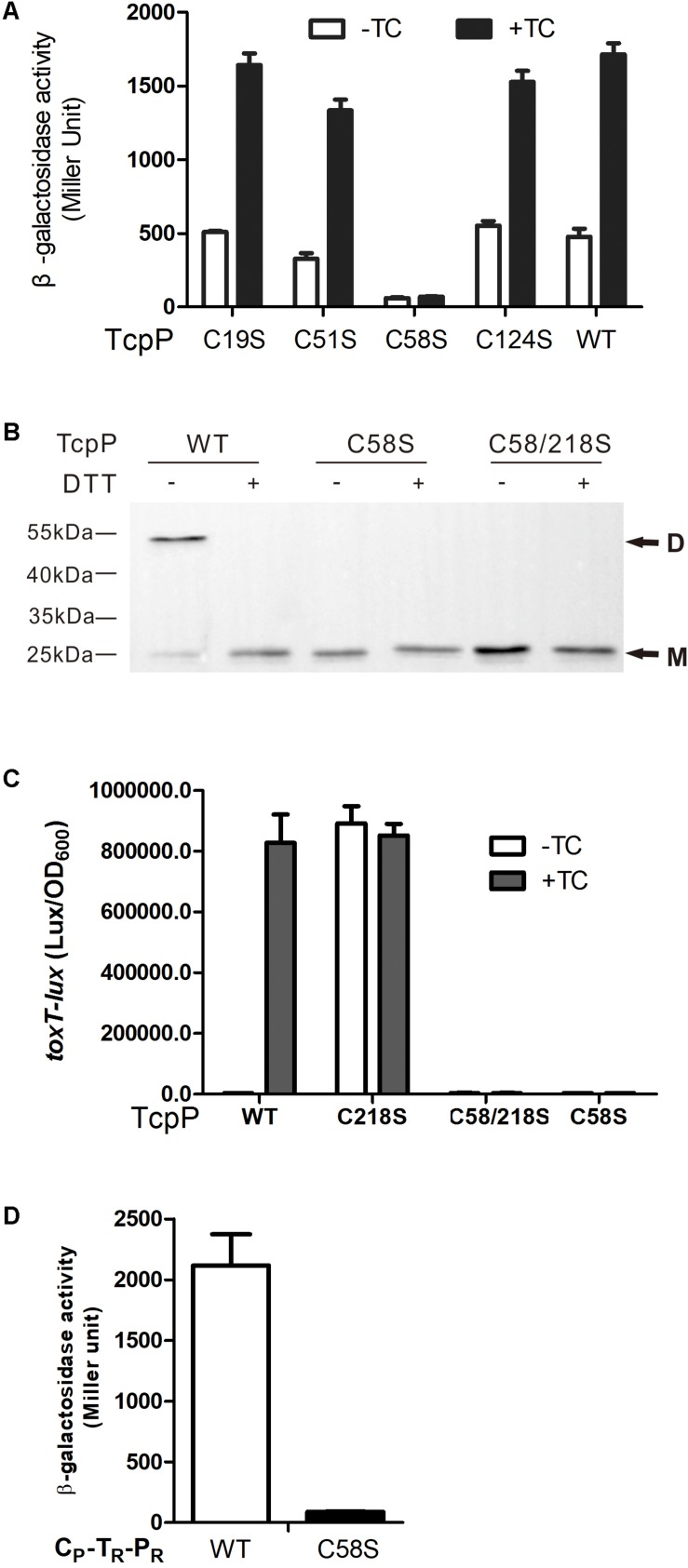

C58 Is Indispensable for TcpP Homodimerization

We previously found that TcpPC218S which can constitutively form homodimer activates toxT expression in the absence of bile salts, while TcpPC207S losing the ability of homodimerization cannot activate toxT expression (Yang et al., 2013). We tested the hypothesis that the TcpPC58S mutant cannot homodimerize by performing bacterial two-hybrid and protein immunoblotting studies. TcpPC58S failed to form homodimers in both assays (Figures 3A,B). TcpP is an inner-membrane protein of V. cholerae. To test if mutagenizing C218S can recover TcpPC58S activity, we constructed a TcpPC58/218S mutant. However, like TcpPC58S, TcpPC58/218S failed to activate toxT expression (Figure 3C) and did not form dimers (Figure 3B). By testing the dimerization of the chimeric protein of TcpP and ToxR (CP-TR-PR), another inner-membrane protein of V. cholerae and also a master regulator of virulence gene expression, we also found that the chimeric protein can form homodimers, but when the 58th cysteine of TcpP was substituted to serine, the mutant could not dimerize (Figure 3D). These results indicated that the cytoplasmic domain of TcpP plays an important role in protein homodimerization and activity.

FIGURE 3.

C58 of TcpP is indispensable for protein dimerization. (A) Full-length TcpP wild type or its cysteine mutant was fused with the T25 and T18 domains of adenylate cyclase (CyaA) from Bordetella pertussis, respectively, and the T25, T18 fusion pairs were introduced into E. coli cyaA mutants (Karimova et al., 1998). Cultures were grown at 30°C for 8 h without shaking and β-galactosidase activity was measured and reported as Miller Units (Miller, 1972). Data are means ± SD (n = 3). (B) V. cholerae ΔtcpP containing PBAD-controlled plasmids harboring TcpP or its cysteine mutant derivatives fused with N-terminal FLAG tags were grown in LB containing 0.01% arabinose in the presence of taurocholate acid at 37°C for 6 h. Cell lysates (0.1 mg) were applied to SDS-PAGE with (+) or without (–) 50 mM of DTT, and subjected to Western blotting using an anti-FLAG antibody. D, dimer; M, monomer. (C) E. coli DH5a strains containing PBAD-controlled plasmids harboring TcpP or its cysteine mutant derivatives and a PtoxT-lux transcriptional fusion plasmid were grown in LB with 0.01% arabinose in the presence or absence of taurocholate acid at 37°C until OD600 ≈ 0.2. Luminescence was measured and reported as light units/OD600. Data are the means ± SD (n = 3). (D) Chimeric TcpP was fused with the T25 and T18 domains and the T25, T18 fusion pairs were introduced into E. coli cyaA mutants (Karimova et al., 1998). Cultures were grown at 30°C for 8 h without shaking and β-galactosidase activity was measured and reported as Miller Units (Miller, 1972). Data are means ± SD (n = 3).

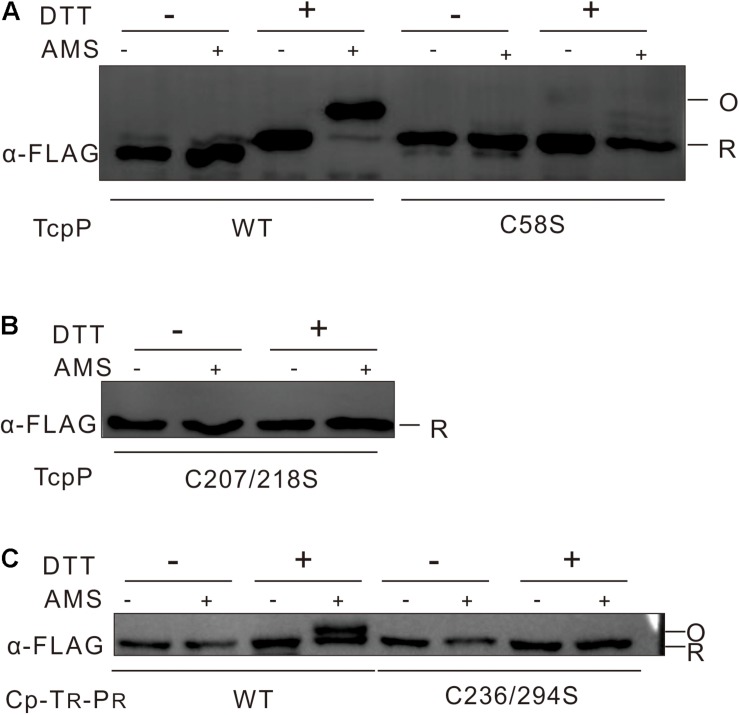

TcpP Cytoplasmic Domain Contains No Disulfide Bonds

We next wanted to determine whether TcpP needs to form disulfide bonds between C58 to activate virulence gene expression in V. cholerae. We first tested the disulfide bond formation of TcpPWT and TcpPC58S by performing AMS labeling assay. We found that TcpPWT contains disulfide bonds, but could not use this information to determine whether disulfide bonds form between the cysteines in the cytoplasmic domain, because it is very likely that disulfide bonds formed between C207 and C218 would be oxidized by DsbA in the periplasm (Xue et al., 2016). Surprisingly, no disulfide bonds were detected in the TcpPC58S mutant (Figure 4A), indicating that the mutagenesis of C58 not only changes the conformation of the TcpP cytoplasmic domain but also the periplasmic domain.

FIGURE 4.

No disulfide bond could be detected in TcpP cytoplasmic domain. (A) V. cholerae ΔtcpP containing PBAD-controlled plasmids harboring TcpP or its cysteine mutant derivatives fused with C-terminal FLAG tags were incubated at 37°C until OD600 ≈ 0.5. To label free thiol groups irreversibly, 100 mM iodoacetamide was added directly to the living cells. After TCA precipitation and extensive washing, oxidized thiol groups were reduced by addition of 50 mM DTT (+) in denaturing buffer or not (–). These reduced cysteines were then alkylated by addition of 10 mM AMS (+) or not (–). Samples were mixed with non-reducing SDS-sample buffer and loaded onto 12.5% SDS-polyacrylamide gels. TcpP was detected by Western blot analysis of the FLAG-tagged proteins. Blot shown is representative of at least three separate experiments. (B) Disulfide bond assay of V. cholerae ΔtcpP strain containing PBAD-controlled plasmids harboring TcpPC207/218S was used the same methods as described in panel A. (C) Disulfide bond assay of E. coli strain containing chimeric TcpP was used the same methods as described in panel A.

To detect specifically disulfide bond formation in the cytoplasmic domain of TcpP, we then tested the disulfide bond formation of TcpPC207/218S mutant by the same methods. No disulfide bond formation could be observed in this case (Figure 4B). To determine whether disulfide bonds form between C58 residues when TcpP dimerizes, we created a chimeric protein consisting of the cytoplasmic domain of TcpP and the transmembrane and periplasmic domains of ToxR (CP-TR-PR) with both of the 236th and 294th cysteine of ToxR substituted to serine. This chimeric protein activated toxT transcription and formed homodimers (Supplementary Figure S2). This chimeric protein did not form disulfide bonds (Figure 4C), suggesting that the disulfide bonds formed in TcpPWT are likely between C207 and C218, and that it is unlikely that disulfide bonds form in the cytoplasmic domain of TcpP.

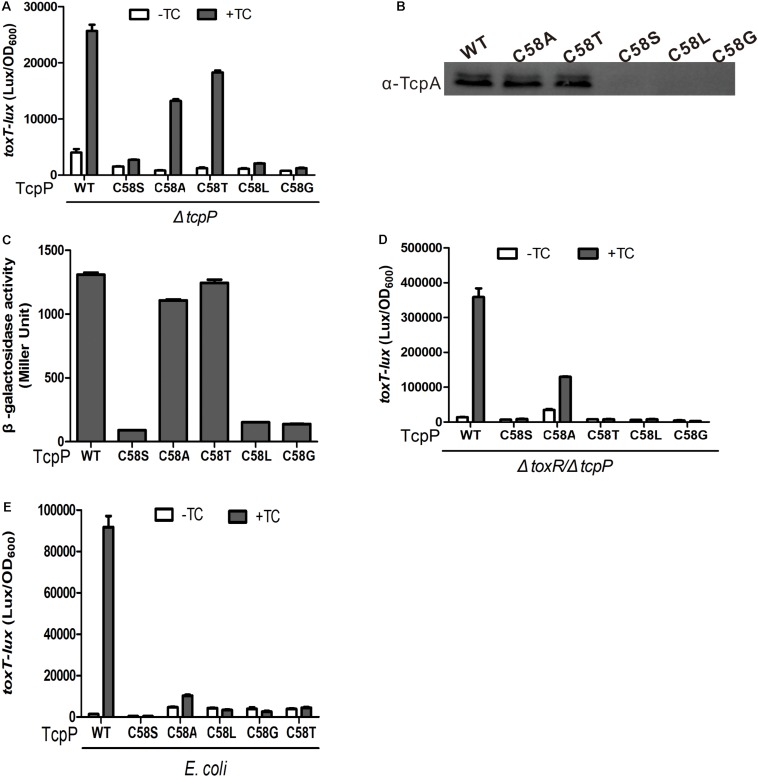

TcpPC58A and TcpPC58T Can Activate Virulence Gene Expression

To further investigate the characteristics of the 58th cysteine of TcpP, we constructed four additional TcpP mutants in which the 58th cysteine was substituted to glycine (G), alanine (A), leucine (L), or threonine (T). We found that both TcpPC58A and TcpPC58T activated virulence gene expression to the same level as TcpPWT (Figure 5A), while TcpPC58G and TcpPC58L, similar to TcpPC58S, lost activity (Figures 5A,B). As expected, the mutagenesis of C58A or C58T of TcpP had no effect on protein homodimerization (Figure 5C). However, in V. cholerae toxR and tcpP double knock-out mutant or in E. coli, these TcpP mutants did not activate toxT expression (Figures 5D,E), indicating that the efficiency of activating toxT expression decreases and is more dependent on ToxR. Thus, although dimerization of TcpP does not require inter- or intra-molecular disulfide bonds in the cytoplasmic domain, the 58th cysteine residue is essential for TcpP to function properly.

FIGURE 5.

TcpP mutants activity and homodimerization assay. (A) V. cholerae ΔtcpP containing PBAD-controlled plasmids harboring TcpP or its cysteine mutant derivatives were grown in LB with 0.01% arabinose in the presence or absence of 1 mM TC at 37°C until OD600 ≈ 0.2. Luminescence was measured and reported as light units/OD600. Data are the means ± SD (n = 3). (B) V. cholerae ΔtcpP containing PBAD-controlled plasmids harboring TcpP or its cysteine mutant derivatives were grown in LB with 0.01% arabinose in the presence of 1 mM TC for 6 h. Then, 0.1-mg cell lysates were applied to SDS-PAGE and subjected to Western blotting using an anti-TcpA antibody. (C) Full-length TcpP wild type or cysteine mutants were fused with the T25 and T18 domains of adenylate cyclase (CyaA) from B. pertussis, respectively, and the T25, T18 fusion pairs were introduced into E. coli cyaA mutants (Karimova et al., 1998). Cultures were grown at 30°C for 8 h without shaking and β-galactosidase activity was measured and reported as Miller Units (Miller, 1972). Data are means ± SD (n = 3). (D) PBAD-controlled plasmids harboring TcpP or its cysteine mutant derivatives and a PtoxT-lux transcriptional fusion plasmid in V. cholerae ΔtoxR/ΔtcpP (D) or E. coli DH5α (E) strains were grown in LB with 0.01% arabinose in the presence or absence of 1 mM TC at 37°C until OD600 ≈ 0.2. Luminescence was measured and reported as light units/OD600. Data are the means ± SD (n = 3).

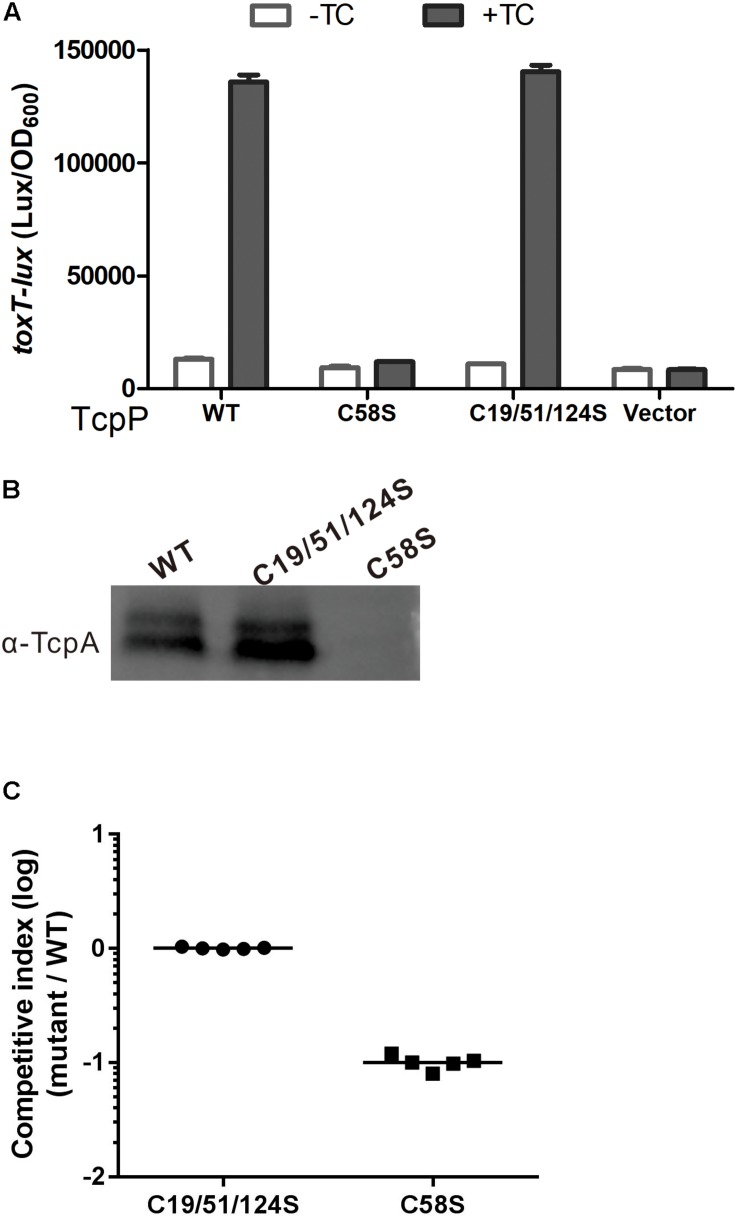

TcpPC19/51/124S Activates Virulence Gene Expression the Same as TcpPWT

To test if C58 alone is sufficient for TcpP to activate virulence gene expression, we constructed a TcpPC19/51/124S mutant. We found that TcpPC19/51/124S can activate virulence gene expression and form homodimers in the presence of bile salts similarly to TcpPWT (Figures 6A,B).

FIGURE 6.

TcpPC19/51/124S activates virulence gene expression similarly to TcpPWT. (A) V. cholerae ΔtcpP strains containing PBAD-controlled plasmids harboring TcpP or its cysteine mutant derivatives and a PtoxT-lux transcriptional fusion plasmid and PBAD vector control were grown in LB with 0.01% arabinose in the presence or absence of taurocholate acid at 37°C until OD600 ≈ 0.2. Luminescence was measured and reported as light units/OD600. Data are the means ± SD (n = 3). (B) V. choleraeΔtcpP strains containing PBAD-TcpP wild type or cysteine mutant plasmids grown in LB with 0.01% arabinose in the presence of taurocholate acid for 6 h. Cell lysates (0.1 mg) were applied to SDS-PAGE and subjected to Western blotting using an anti-TcpP or anti-TcpA antibody. (C) In vivo competition assay using an infant mouse model. Five-days-old ICR infant mice were inoculated with the mixture of TcpP cysteine mutant and WT at 1:1 ratio. Intestinal homogenates were collected 22 h later, and the ratio of mutant-to-WT bacteria was determined and normalized against input ratios.

The infant mouse model is the most commonly used animal model to study the infection and colonization of V. cholerae in the mammal intestine (Matson, 2018). The competition assays applied in this model, in which both a mutant and a wild type V. cholerae strain are infected to the same mouse and their colonization would be compared, are often used to identify factors that contribute to the virulence of V. cholerae (Angelichio et al., 1999; Matson, 2018). By using the infant mouse model to do the competitive experiment, we found that TcpPC19/51/124S and TcpPWT showed similar colonization efficiency, while TcpPC58S was significantly attenuated (Figure 6C). These results indicate that C58 alone is sufficient for TcpP to activate virulence gene expression and plays an important role for V. cholerae to colonize in the infant mouse intestine.

Discussion

Vibrio cholerae, which resides in aquatic environments as well as human intestines during its infection cycle, coordinates the transcription of virulence genes by sensing different environmental signals (Krukonis and DiRita, 2003; Matson et al., 2007). We previously reported that TcpP senses bile salt signals in the small intestine through the two cysteines in its periplasmic domain to activate the ToxT regulon (Yang et al., 2013; Xue et al., 2016). And Morgan et al. (2016) found that the formation of an intramolecular periplasmic disulfide bond in TcpP protects TcpP and TcpH from degradation in V. cholerae. In this study, we further investigated the functions of the cysteines in the cytoplasmic domain of TcpP, and we found that C58 is essential for TcpP homodimerization and activating virulence gene expression.

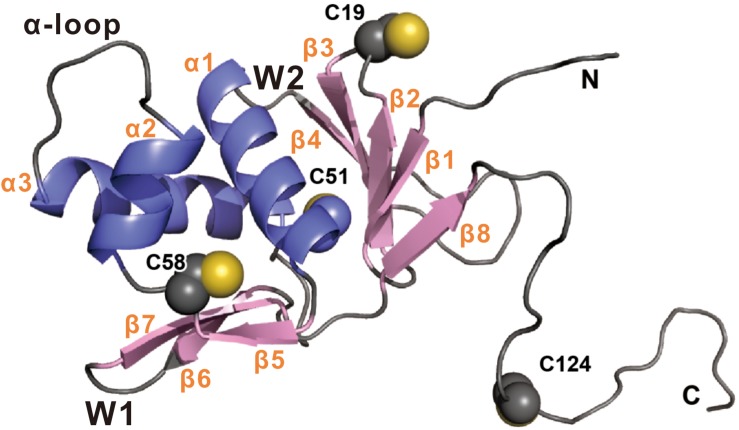

Vibrio cholerae virulence is controlled by a regulatory pathway that responds to environmental signals (Matson et al., 2007). Under anaerobic conditions, TcpP is synthesized and induced by bile salts to mediate derepression and activation of ToxT, together with another membrane localized activator, ToxR (Krukonis and DiRita, 2003; Liu et al., 2011; Yang et al., 2013). Both TcpP and ToxR are members of OmpR/PhoB wHTH transcriptional activator family, and secondary structure predictions suggest that they share similar structural organization in their N termini (Martinez-Hackert and Stock, 1997; Figure 7). There is no structure available for TcpP, so we built a homology model based on the crystal structure of PhoB (Okamura et al., 2000; Figure 7). According to this model, the residue of C19 is located in the second β turn of the N-terminal β-sheet, while C51 and C58 flank the β5 strand that connects helices α1 and α2 (Figure 7). The C-terminus of TcpP115–140 is predicted to be disordered. Therefore, the position of C124 cannot be precisely mapped. This model shows that the side chain of C58 is facing inwards toward the structural core formed by three helices in the cytoplasmic domain of TcpP (Figure 7). We speculate that mutation of C58 may cause perturbation of the overall fold or dynamics of the TcpP monomer, which, in turn, may have an impact on the dimer formation of TcpP. We found that the cytoplasmic domain of TcpP mutant C58S cannot fold properly or bind to DNA in vitro (Figure 2). Mutating C58 to serine also prevented disulfide bond formation between the periplasmic C207 and C218 residues (Figure 3A). This indicates that the conformation of the cytoplasmic domain of TcpP can affect the folding of the periplasmic domain. Mutating C58 to alanine or threonine might not affect the structure of TcpP as significantly as that to serine, leucine or glycine. So the TcpP mutants C58S, C58L, and C58G were inactive, irrespective of the presence of ToxR, either, while C58A and C58T exhibited near wild type activity when coexpressed with ToxR (Figure 5). However, we found no evidence suggesting that disulfide bonds are required to form between C58 to promote TcpP homodimerization. Future structural studies may be needed to understand better this phenotype.

FIGURE 7.

Homology model of TcpP1–135 was built using the online intFold server (McGuffin et al., 2019). The structure is shown in cartoon representation with β strand and α helix colored pink and blue, respectively. The side-chains of Cys19, Cys51, Cys58, and Cys124 are shown as spheres. Secondary structural and biologically relevant elements are labeled. α, α helix; β, β strand; W, wing.

Another Vibrio species, Vibrio parahaemolyticus also possesses a TcpP homolog, VtrA, which regulates the expression of Vp-PAI genes by directly responding to bile salt concentrations (Li et al., 2016). Unlike TcpP, VtrA has only one cysteine residue in its cytoplasmic domain, C43; yet, we found that like TcpP C58S, the VtrA C43S mutant also failed to homodimerize and is unable to activate the expression of downstream virulence genes (Supplementary Figure S3). This might indicate that the cysteine residue of C58 in TcpP and C43 in VtrA regulate protein function by the same mechanism. Although the other three cysteine residues (C19, C51, and C124) were not found to play any role in TcpP homodimerization and virulence gene activation (Figure 6), we did find that these three cysteines play an important role for V. cholerae to survive in other environmental niches.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation, to any qualified researcher.

Ethics Statement

The animal study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Zhejiang A&F University (Permit Number: ZJAFU/IACUC_2011-10-25-02). Written informed consent was obtained from the owners for the participation of their animals in this study.

Author Contributions

MS, NL, and YX performed the research (the acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of the data). MS, NL, YX, ZZ, and MY analyzed the data. ZZ and MY designed the research and wrote the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank the laboratory members for discussion and reviewing the manuscript. We also thank Dr. Jinzhong Lin (Fudan University) for helpful discussions.

Footnotes

Funding. This work was funded by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Number 31770151), the Science Development Foundation of Zhejiang A&F University (Grant Number 2013FR012), and the Natural Science Foundation of Zhejiang Province (Grant Number LZ20C010001) to MY. The funding body had no role in the design of the experiments or the interpretation of the data.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmicb.2020.00118/full#supplementary-material

References

- Angelichio M. J., Spector J., Waldor M. K., Camilli A. (1999). Vibrio cholerae intestinal population dynamics in the suckling mouse model of infection. Infect. Immun. 67 3733–3739. 10.1128/iai.67.8.3733-3739.1999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck N. A., Krukonis E. S., DiRita V. J. (2004). TcpH influences virulence gene expression in Vibrio cholerae by inhibiting degradation of the transcription activator TcpP. J. Bacteriol. 186 8309–8316. 10.1128/JB.186.24.8309-8316.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang A. C., Cohen S. N. (1978). Construction and characterization of amplifiable multicopy DNA cloning vehicles derived from the P15A cryptic miniplasmid. J. Bacteriol. 134 1141–1156. 10.1128/jb.134.3.1141-1156.1978 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawford J. A., Krukonis E. S., DiRita V. J. (2003). Membrane localization of the ToxR winged-helix domain is required for TcpP-mediated virulence gene activation in Vibrio cholerae. Mol. Microbiol. 47 1459–1473. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03398.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denoncin K., Nicolaes V., Cho S. H., Leverrier P., Collet J. F. (2013). Protein disulfide bond formation in the periplasm: determination of the in vivo redox state of cysteine residues. Methods Mol. Biol. 966 325–336. 10.1007/978-1-62703-245-2_20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan F., Liu Z., Jabeen N., Birdwell L. D., Zhu J., Kan B. (2014). Enhanced interaction of Vibrio cholerae virulence regulators TcpP and ToxR under oxygen-limiting conditions. Infect. Immun. 82 1676–1682. 10.1128/IAI.01377-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guzman L. M., Belin D., Carson M. J., Beckwith J. (1995). Tight regulation, modulation, and high-level expression by vectors containing the arabinose PBAD promoter. J. Bacteriol. 177 4121–4130. 10.1128/jb.177.14.4121-4130.1995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haas B. L., Matson J. S., DiRita V. J., Biteen J. S. (2015). Single-molecule tracking in live Vibrio cholerae reveals that ToxR recruits the membrane-bound virulence regulator TcpP to the toxT promoter. Mol. Microbiol. 96 4–13. 10.1111/mmi.12834 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hay A. J., Yang M., Xia X., Liu Z., Hammons J., Fenical W., et al. (2017). Calcium enhances bile salt-dependent virulence activation in Vibrio cholerae. Infect. Immun. 85 e707–e716. 10.1128/IAI.00707-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higuchi R., Krummel B., Saiki R. K. (1988). A general method of in vitro preparation and specific mutagenesis of DNA fragments: study of protein and DNA interactions. Nucleic Acids Res. 16 7351–7367. 10.1093/nar/16.15.7351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joelsson A., Liu Z., Zhu J. (2006). Genetic and phenotypic diversity of quorum-sensing systems in clinical and environmental isolates of Vibrio cholerae. Infect. Immun. 74 1141–1147. 10.1128/IAI.74.2.1141-1147.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karimova G., Pidoux J., Ullmann A., Ladant D. (1998). A bacterial two-hybrid system based on a reconstituted signal transduction pathway. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95 5752–5756. 10.1073/pnas.95.10.5752 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovacikova G., Lin W., Skorupski K. (2010). The LysR-type virulence activator AphB regulates the expression of genes in Vibrio cholerae in response to low pH and anaerobiosis. J. Bacteriol. 192 4181–4191. 10.1128/JB.00193-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krukonis E. S., DiRita V. J. (2003). DNA binding and ToxR responsiveness by the wing domain of TcpP, an activator of virulence gene expression in Vibrio cholerae. Mol. Cell 12 157–165. 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00222-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krukonis E. S., Yu R. R., Dirita V. J. (2000). The Vibrio cholerae ToxR/TcpP/ToxT virulence cascade: distinct roles for two membrane-localized transcriptional activators on a single promoter. Mol. Microbiol. 38 67–84. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.02111.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larocque R. C., Harris J. B., Dziejman M., Li X., Khan A. I., Faruque A. S., et al. (2005). Transcriptional profiling of Vibrio cholerae recovered directly from patient specimens during early and late stages of human infection. Infect. Immun. 73 4488–4493. 10.1128/IAI.73.8.4488-4493.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li P., Rivera-Cancel G., Kinch L. N., Salomon D., Tomchick D. R., Grishin N. V., et al. (2016). Bile salt receptor complex activates a pathogenic type III secretion system. eLife 5:e15718. 10.7554/eLife.15718 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z., Wang H., Zhou Z., Naseer N., Xiang F., Kan B., et al. (2016a). Differential thiol-based switches jump-start Vibrio cholerae pathogenesis. Cell Rep. 14 347–354. 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.12.038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z., Wang H., Zhou Z., Sheng Y., Naseer N., Kan B., et al. (2016b). Thiol-based switch mechanism of virulence regulator AphB modulates oxidative stress response in Vibrio cholerae. Mol. Microbiol. 102 939–949. 10.1111/mmi.13524 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z., Yang M., Peterfreund G. L., Tsou A. M., Selamoglu N., Daldal F., et al. (2011). Vibrio cholerae anaerobic induction of virulence gene expression is controlled by thiol-based switches of virulence regulator AphB. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108 810–815. 10.1073/pnas.1014640108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandlik A., Livny J., Robins W. P., Ritchie J. M., Mekalanos J. J., Waldor M. K. (2011). RNA-Seq-based monitoring of infection-linked changes in Vibrio cholerae gene expression. Cell Host Microbe 10 165–174. 10.1016/j.chom.2011.07.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Hackert E., Stock A. M. (1997). Structural relationships in the OmpR family of winged-helix transcription factors. J. Mol. Biol. 269 301–312. 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matson J. S. (2018). Infant mouse model of Vibrio cholerae infection and colonization. Methods Mol. Biol. 1839 147–152. 10.1007/978-1-4939-8685-9_13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matson J. S., Withey J. H., DiRita V. J. (2007). Regulatory networks controlling Vibrio cholerae virulence gene expression. Infect. Immun. 75 5542–5549. 10.1128/IAI.01094-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGuffin L. J., Adiyaman R., Maghrabi A. H. A., Shuid A. N., Brackenridge D. A., Nealon J. O., et al. (2019). IntFOLD: an integrated web resource for high performance protein structure and function prediction. Nucleic Acids Res. 47 W408–W413. 10.1093/nar/gkz322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Midgett C. R., Almagro-Moreno S., Pellegrini M., Taylor R. K., Skorupski K., Kull F. J. (2017). Bile salts and alkaline pH reciprocally modulate the interaction between the periplasmic domains of Vibrio cholerae ToxR and ToxS. Mol. Microbiol. 105 258–272. 10.1111/mmi.13699 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller J. (1972). Experiments in Molecular Genetics. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press. [Google Scholar]

- Moorthy S., Watnick P. I. (2005). Identification of novel stage-specific genetic requirements through whole genome transcription profiling of Vibrio cholerae biofilm development. Mol. Microbiol. 57 1623–1635. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04797.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan S. J., French E. L., Thomson J. J., Seaborn C. P., Shively C. A., Krukonis E. S. (2016). Formation of an intramolecular periplasmic disulfide bond in TcpP protects TcpP and TcpH from degradation in Vibrio cholerae. J. Bacteriol. 198 498–509. 10.1128/JB.00338-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen A. T., Dolganov N. A., Otto G., Miller M. C., Wu C. Y., Schoolnik G. K. (2006). RpoS controls the Vibrio cholerae mucosal escape response. PLoS Pathog. 2:e109. 10.1371/journal.ppat.0020109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen A. T., Dolganov N. A., Rasmussen T., Otto G., Miller M. C., Felt S. A., et al. (2010). A bistable switch and anatomical site control Vibrio cholerae virulence gene expression in the intestine. PLoS Pathog. 6:e1001102. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamura H., Hanaoka S., Nagadoi A., Makino K., Nishimura Y. (2000). Structural comparison of the PhoB and OmpR DNA-binding/transactivation domains and the arrangement of PhoB molecules on the phosphate box. J. Mol. Biol. 295 1225–1236. 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tetsch L., Koller C., Donhofer A., Jung K. (2011). Detection and function of an intramolecular disulfide bond in the pH-responsive CadC of Escherichia coli. BMC Microbiol. 11:74. 10.1186/1471-2180-11-74 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson J. D., Higgins D. G., Gibson T. J. (1994). CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 22 4673–4680. 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vazquez-Torres A. (2012). Redox active thiol sensors of oxidative and nitrosative stress. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 17 1201–1214. 10.1089/ars.2012.4522 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue Y., Tu F., Shi M., Wu C. Q., Ren G., Wang X., et al. (2016). Redox pathway sensing bile salts activates virulence gene expression in Vibrio cholerae. Mol. Microbiol. 102 909–924. 10.1111/mmi.13497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang M., Liu Z., Hughes C., Stern A. M., Wang H., Zhong Z., et al. (2013). Bile salt-induced intermolecular disulfide bond formation activates Vibrio cholerae virulence. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110 2348–2353. 10.1073/pnas.1218039110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu J., Mekalanos J. J. (2003). Quorum sensing-dependent biofilms enhance colonization in Vibrio cholerae. Dev. Cell 5 647–656. 10.1016/s1534-5807(03)00295-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu J., Miller M. B., Vance R. E., Dziejman M., Bassler B. L., Mekalanos J. J. (2002). Quorum-sensing regulators control virulence gene expression in Vibrio cholerae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99 3129–3134. 10.1073/pnas.052694299 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation, to any qualified researcher.