Abstract

Two of the most economically important plants in the Artocarpus genus are jackfruit (A. heterophyllus Lam.) and breadfruit (A. altilis (Parkinson) Fosberg). Both species are long-lived trees that have been cultivated for thousands of years in their native regions. Today they are grown throughout tropical to subtropical areas as an important source of starch and other valuable nutrients. There are hundreds of breadfruit varieties that are native to Oceania, of which the most commonly distributed types are seedless triploids. Jackfruit is likely native to the Western Ghats of India and produces one of the largest tree-borne fruit structures (reaching up to 45 kg). To-date, there is limited genomic information for these two economically important species. Here, we generated 273 Gb and 227 Gb of raw data from jackfruit and breadfruit, respectively. The high-quality reads from jackfruit were assembled into 162,440 scaffolds totaling 982 Mb with 35,858 genes. Similarly, the breadfruit reads were assembled into 180,971 scaffolds totaling 833 Mb with 34,010 genes. A total of 2822 and 2034 expanded gene families were found in jackfruit and breadfruit, respectively, enriched in pathways including starch and sucrose metabolism, photosynthesis, and others. The copy number of several starch synthesis-related genes were found to be increased in jackfruit and breadfruit compared to closely-related species, and the tissue-specific expression might imply their sugar-rich and starch-rich characteristics. Overall, the publication of high-quality genomes for jackfruit and breadfruit provides information about their specific composition and the underlying genes involved in sugar and starch metabolism.

Keywords: jackfruit, breadfruit, A. heterophyllus, A. altilis, starch synthesis

1. Introduction

The family Moraceae contains at least 39 genera and approximately 1100 species [1,2,3]. Species diversity of the family is primarily centered in the tropics with variation in inflorescence structures, pollination forms, breeding systems, and growth forms [2]. Within the Moraceae family, the genus Artocarpus is comprised of approximately 70 species [2,4]. The most recent evidence indicates that Borneo was the center of diversification of the Artocarpus genus and that species diversified throughout South and Southeast Asia [2]. All members of the genus have unisexual flowers and produce exudate from laticifers. Inflorescences consist of up to thousands of tiny flowers, tightly packed and condensed on a receptacle [2]. In most species, the perianths of adjacent female flowers are partially to completely fused together and develop into a highly specialized multiple fruit called a syncarp, which is formed by the enlargement of the entire female head. Syncarps of different species range in size from a few centimeters in diameter to over half a meter long in the case of jackfruit [2,5]. Many Artocarpus species are important food sources for forest fauna, and about a dozen species are important crops in the regions where they are from [2,6].

Jackfruit (A. heterophyllus Lam.) is thought to have originated in in the Western Ghats of India and is cultivated as an important food source across the tropics. It is monecious, and thought to be pollinated by gall midges [7]. In some areas it is propagated mainly by seeds [8], however, clonal propagation via grafting is increasing in areas where it is grown for commercial use [9]. On average it contains more than 100 seeds per fruit with viability of less than a month [10,11]. The male flowers are tiny and clustered on an oblong receptacle, typically 5–10 cm in length. Limited studies exist on the range of cultivated varieties of jackfruit, but they are often grouped into two main types, varieties with edible fleshy perianth tissue (often referred to as “flakes”) that are either (a) small, fibrous, soft, and spongy, or (b) larger, less sweet crisp fruit [10,12]. The latter type is often more commercially important.

Breadfruit (A. altilis [Parkinson] Fosberg) is most likely derived from the progenitor species A. camansi Blanco, which is native to New Guinea [10,13]. As humans migrated and colonized the islands of Remote Oceania, indigenous people selected and cultivated varieties from the wild ancestor over thousands of years [13], giving rise to hundreds of cultivated varieties [10,13,14,15]. Cultivated varieties were traditionally propagated clonally by root cuttings but can now be commercially propagated by tissue culture [16,17]. Among the hundreds of varieties, some are diploid (2n = 2x = ~56) and may produce seeds, while other varieties are seedless triploids (3n = 2x = ~84), and still others are of hybrid origin with another species, A. mariannensis Trécul [13,18,19,20]. A small subset of the triploid diversity is what has been introduced outside of Oceania [19,21].

To diversify the global food supply, enhance agricultural productivity, and eradicate malnutrition, it is necessary to focus on crop improvement of plants that are utilized in rural societies as a local source of nutrition and sustenance. This study is part of the African Orphan Crops Consortium (AOCC), an international public-private partnership. A goal of this global initiative is to sequence, assemble, and annotate the genomes of 101 traditional African food crops [22,23]. Both breadfruit and jackfruit are nutritious [24,25,26,27] and have the potential to increase food security, especially in tropical areas. Until now limited genomic information has been available for the Artocarpus genus as a whole. Microsatellite markers have been used to characterize cultivars and wild relatives of breadfruit [8,19,21,28], jackfruit [29], and other Artocarpus crop species [6,30,31]. Additionally, an assembled and annotated reference transcriptome of A. altilis has been generated [20]. Twenty-four transcriptomes of breadfruit and its wild relatives revealed signals of positive selection that may have resulted from local adaptation or natural selection [20]. Finally, a low coverage whole genome sequence has been published for A. camansi [32], but full genome sequences for jackfruit and breadfruit are still not available. Here, we report high-quality annotated draft genome sequences for both jackfruit and breadfruit. The results help explain their energy-dense fruit composition and the underlying genes involved in sugar and starch metabolism.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Collection, NGS Library Construction, and Sequencing

Genomic DNA was extracted from fresh leaves of A. heterophyllus (ICRAFF 11314) and A. altilis (ICRAFF 11315), grown at the World AgroForestry (ICRAF) campus in Kenya, using a modified CTAB method [33]. Extracted DNA was used to construct four paired-end libraries (170, 350, 500, and 800 bp) and four mate-pair libraries (2, 6, 10, and 20 Kb) following the standard protocols provided by Illumina (San Diego, CA, USA). Subsequently, the sequencing was performed on a HiSeq 2000 platform (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) using a whole genome shotgun sequencing strategy. To improve the data quality, the poor quality reads were filtered using SOAPfilter (v2.2) [34] with the following parameters: (1) low-quality bases with Q = below 7 and 15 for A. altilis and A. heterophyllus, respectively were trimmed from forward and reverse reads; (2) reads with ≥30% low quality bases (quality score ≤ 15); (3) reads with ≥10% uncalled (“N”) bases; (4) reads with adapter contamination or PCR duplicates; (5) reads with undersized insert sizes were discarded. Finally, more than 100 high-quality reads were obtained for each species (see Supplementary Materials: Table S1).

For transcriptome sequencing, the RNA was extracted from different tissues of A. altilis (various leaf stages, leaf buds, and roots) and A. heterophyllus (various leaf stages, leaf bud, stem, bark, roots, germinated seed, and seedling). The RNA was extracted using the PureLink RNA Mini Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Carlsbad, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. For each sample, RNA libraries were constructed by following the TruSeq RNA Sample Preparation Kit (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) manual, and were then sequenced on the Illumina HiSeq 2500 platform (paired-end, 100-bp reads), generating more than 47 Gb of sequence data for each species. Data were then filtered using a similar criterion as used to filter DNA NGS data, with a slight modification: (1) reads with ≥10% low-quality bases (quality score ≤ 15) were removed; and (2) reads with ≥5% uncalled (“N”) bases were removed (see Supplementary Materials: Table S2). All of the transcriptome data were compiled, and the combined version was used to check the completeness of the whole genome sequence assembly.

2.2. Evaluation of Genome Size

Clean reads of the paired-end libraries (170, 250, and 500 bp) were used to estimate the genome size by k-mer frequency distribution and heterozygosity analysis. The genome size was estimated based on the following formula:

| G = N × (L − 17 + 1)/K_depth | (1) |

where N represents the number of used reads, L represents the read length, K represents the k-mer value in the analysis, and K_depth refers to the location of the main peak in the distribution curve [35]. The heterozygosity was evaluated by the GCE software [36].

2.3. De Novo Genome Assembly

The de novo genome assembly tool, Platanus (Platanus, RRID: SCR_015531) [37], was used to construct the contigs and scaffolds in three steps: contig assembling, scaffolding and gap closing. In contig assembling, paired-end libraries ranging from 170 to 800 bp were used with the parameters “-d 0.5 -K 39 -u 0.1 -m 300”. In the scaffolding step, paired-end and mate-pair information were used to with parameters “-u 0.1”. Lastly, the paired-end reads were used for gap closing using GapCloser version 1.12 (GapCloser, RRID: SCR_015026) [34], with the parameters “-l 150 -t 32 -p 31”.

2.4. Genome Assembly Evaluation

The genome assembly completeness was assessed using BUSCO (Benchmarking Universal Single-Copy Orthologues), version 3.0.1 (BUSCO, RRID: SCR_015008) [38]. Next, the unigenes generated by Bridger software [39] from the transcriptome data of each species were aligned to the assembled genomes using BLAT (BLAT, RRID: SCR_011919) [40] with default parameters. In order to confirm the accuracy of the assembly, some of the paired-end libraries (170, 250, and 350 bp) were aligned to the assembled genomes, and the sequencing coverage was calculated using SOAPaligner, version 2.21 (SOAPaligner/soap2, RRID: SCR_005503) [41].

We calculated the GC content and average depth with 10 kb non-overlapping windows. The distribution of GC content indicated a relative pure single genome without contamination or GC bias (Supplementary Materials: Figure S3). Moreover, the GC content of A. altilis and A. heterophyllus genomes were also compared with three rosids species (Fragaria vesca, Malus domestica, and Morus notabilis).

2.5. Repeat Annotation

Repetitive sequences were identified by using RepeatMasker (version 4-0-5) [42], with a combined library consisting of the Repbase library and a custom library obtained through careful self-training. The custom library was composed of three parts: the MITE, LTR, and an extensive library, which were constructed as described below. First of all, the library of miniature inverted-repeat transposable elements (MITEs) was created by annotation using MITE-hunter [43] with default parameters. Secondly, the library of long terminal repeats (LTR) was constructed using LTRharvest [44] integrated in Genometools (version 1.5.8) [45] with parameters “-minlenltr 100 -maxlenltr 6000 -mindistltr 1500 -maxdistltr 25,000 -mintsd 5 -maxtsd 5 -similar 90 -vic 10” to detect LTR candidates with lengths of 1.5 kb to 25 kb, including two terminal repeats ranging from 100 bp to 6000 bp with ≥ 85% similarity. In order to improve the quality of the LTR library, we used several strategies to filter the candidates. As intact PPT (poly purine tract) or PBS (primer binding site) was necessary to define LTR, we subsequently used LTRdigest [46] with a eukaryotic tRNA library [47] to identify these features, and then removed the elements without appropriate PPT or PBS locations. Subsequently, to remove contamination, like local gene clusters and tandem local repeats, 50 bp of flanking sequences on both sides of each LTR candidate were aligned using MUSCLE (MUSCLE, RRID:SCR_011812) [48] with default parameters: if the identity ≥ 60%, the candidate was taken as a false positive and removed. LTR candidates which nested with other types of elements were also removed. Exemplars for the LTR library were extracted from the filtered candidates using a cutoff of 80% identity in 90% of sequence length. Furthermore, the regions annotated as LTRs and MITEs in the genome were masked, and then put into RepeatModeler version 1-0-8 RepeatModeler, RRID: SCR_015027) to predict other repetitive sequences for the extensive library.

Finally, the MITE, LTR and extensive libraries were integrated into the custom library, which was combined with the Repbase library and then taken as the input for RepeatMasker to identify and classify repetitive elements genome wide.

2.6. Gene Prediction

Repetitive regions of the genome were masked before gene prediction. Based on the RNA, homologous and de novo prediction evidence, the protein-coding genes were identified using the MAKER-P pipeline (version 2.31) [49]. For RNA evidence, the clean transcriptome reads were assembled into inchworms using Trinity version 2.0.6 [50], and then fed to MAKER-P as EST evidence. For homologous evidence, the protein sequences from four relative species in the rosids (F. vesca, M. domestica, M. notabilis, Prunus persica, Ziziphus jujuba) were downloaded and provided as protein evidence.

For de novo prediction evidence, a series of training attempts were made to optimize different ab initio gene predictors. At first, a set of transcripts were generated by a genome-guided approach using Trinity with parameters “--full_cleanup --jaccard_clip --genome_guided_max_intron 10,000 --min_contig_length 200”. The transcripts were then mapped back to the genome using PASA (version 2.0.2) [51] and a set of gene models with real gene characteristics (e.g., size and number of exons/introns per gene, features of spicing sites) was generated. The complete gene models were picked for training Augustus [52]. Genemark-ES (version 4.21) [53] was self-trained with default parameters. The first round of MAKER-P was run based on the evidence above with default parameters except “est2genome” and “protein2genome” set to “1”, yielding only RNA- and protein-supported gene models. SNAP [54] was then trained with these gene models. Default parameters were used to run the second and final round of MAKER-P, producing final gene models.

Furthermore, non-coding RNA genes in the A. altilis and A. heterophyllus genomes were also annotated. The BLAST tool was employed to search ribosomal RNA (rRNA) against the A. thaliana rRNA database, and to search microRNAs (miRNA) and small nuclear RNA (snRNA) against ther Rfam database (Rfam, RRID: SCR_004276) (release 12.0) [55]. tRNAscan-SE (tRNAscan-SE, RRID: SCR_010835) [56] was used to scan transfer RNA (tRNA) in the genome sequences.

2.7. Functional Annotation of Protein-Coding Genes

Functional annotation of protein-coding genes was based on sequence similarity and domain conservation by aligning translated coding sequences to public databases. The protein-coding genes were first queried against protein sequence databases, such as KEGG (KEGG, RRID: SCR_012773) [57], NR database (NCBI), COG [58], SwissProt, and TrEMBL [59] for best-matches using BLASTP with an E-value cut-off of 1 × 10−5. Secondly, InterProScan 55.0 (InterProScan, RRID: SCR_005829) [60] was used as an engine to identify the motif and domain-based on Pfam (Pfam, RRID: SCR_004726) [61], SMART (SMART, RRID: SCR_005026) [62], PANTHER (PANTHER, RRID: SCR_004869) [63], PRINTS (PRINTS, RRID: SCR_003412) [64] and ProDom (ProDom, RRID: SCR_006969) [65,66].

2.8. Ks-Distribution Analysis

The coding sequences and annotations for Morus notabilis were downloaded from the NCBI, reference RefSeq assembly accession GCF_000414095.1 [66]. The coding sequences and annotations for Ziziphus jujube [67] were downloaded from the Plaza4 database [68]. The headers of the fasta files, as well as the ninth columns of the gff3 files were edited to make the datasets compatible with the software packages used for downstream analysis.

Ks-distribution analyses were performed, using the wgd-package [69]. For each species, the paranome was obtained by performing an all-against-all BlastP [70], with MCL clustering [71]. Codon multiple sequence alignment was done using MUSCLE [48]. Ks-distributions were constructed using codeml from the PAML4 package [72] and Fast-Tree [73] for inferring phylogenetic trees used in the node weighting procedure, other software used by the wgd. Thereafter, i-ADHoRe [74] was used to get anchor-point distributions and produce dot-plots. Lastly, Gausian mixture modes were fitted using 1–5 components.

2.9. One vs. One Synteny

One-vs.-one synteny analysis was performed for pairs of the above-mentioned species, using the “work-flow 2” script that is part of the wgd-package [69]. In order to compare A. altilis, A. heterophyllus, we use MCScanX to detect the synteny and collinearity, and MCscan (Python version) for the visualization.

2.10. Gene Family Construction

Protein and nucleotide sequences from A. altilis, A. heterophyllus, and seven species (A. thaliana, F. vesca, M. domestica, M. notabilis, P. mume, P. persica, Z. jujuba) were retrieved to construct gene families using OrthoMCL software [75] based on an all-versus-all BLASTP alignment with an E-value cutoff of 1 × 10−5.

2.11. Collinearity Analysis

Collinearity of the largest orthologous scaffolds were determined and plotted using MCscan and the JCVI utility libraries v0.9.14 [76,77].

2.12. Phylogenetic Analysis and Divergence Time Estimation

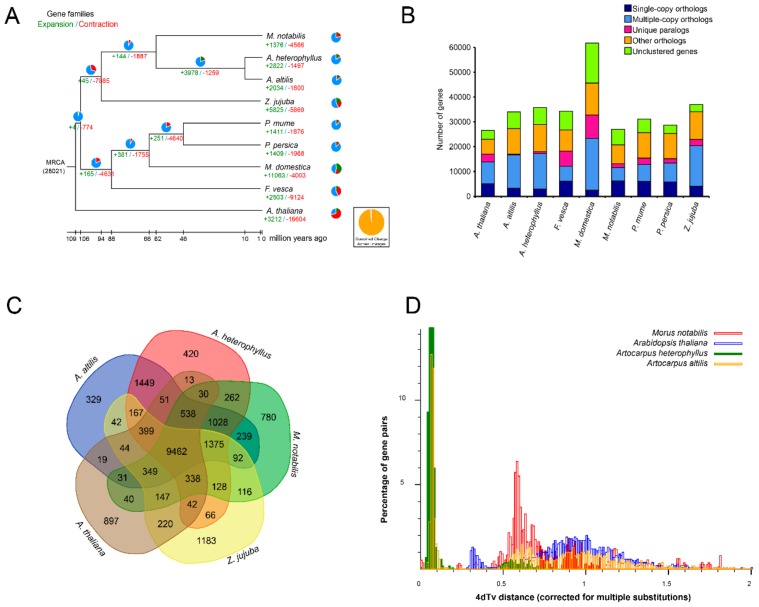

We identified 486 single-copy genes in the nine species, and subsequently used them to build the phylogenetic tree. Coding DNA sequence (CDS) alignments of each single-copy family were constructed following the protein sequence alignment with MUSCLE (MUSCLE, RRID: SCR_011812) [48]. The aligned CDS sequences of each species were then concatenated to a super gene sequence. The phylogenetic tree was constructed with PhyML-3.0 (PhyML, RRID: SCR_014629) [78] with the HKY85+ Gamma substitution model on extracted four-fold degenerate sites. Divergence time was calculated using the Bayesian relaxed molecular clock approach using MCMCTREE in PAML (PAML, RRID: SCR_014932) [72], based on the published calibration times (divergence between Arabidopsis thaliana and Rosales was 108-109 Mya, divergence between P. mume and P. persica was 24–72 Mya) [66]. The divergence time between M. notabilis and Artocarpus was predicted to be 61.8 (54.1–76.0) Mya (Figure 1A). Subsequently, to study gene gain and loss, CAFE (CAFE, RRID:SCR_005983) [79] was employed to estimate the universal gene birth and death rate λ (lambda) under a random birth and death model with the maximum likelihood method. The results for each branch of the phylogenetic tree were estimated (Figure 1A). Enrichment analysis on GO and the pathway of genes in expanded families in the Artocarpus lineage were also calculated.

Figure 1.

Phylogenetic and evolutionary analysis. (A,B) Gene conservation and gene family expansion and contraction in A. heterophyllus and A. altilis. The scale bar indicates 10 million years. The values at the branch points indicate the estimates of divergence time (mya), while the green numbers show the divergence time (million years ago, Mya), and the red nodes indicate the previously published calibration times. (C) The distribution of gene families among the model species and Artocarpus genus. (D) Distribution of 4DTv distance between collinearity gene pairs among A. heterophyllus, A. altilis, M. notabilis, and Arabidopsis thaliana.

2.13. Identification of Starch Biosynthesis-Related Genes

Using the amino acid, starch biosynthesis-related genes in soybean as bait, we performed an ortholog search in A. altilis, A. heterophyllus, M. notabilis, Z. jujuba, P. mume, P. persica, F. vesca, M. domestica, and A. thaliana.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Genome Sequencing and Assembly

A total of eight libraries were constructed including four short-insert libraries (170 bp, 350 bp, 500 bp, and 800 bp) and four mate-pair libraries (2 kb, 5 kb, 10 kb, and 20 kb) for Illumina Hiseq2000 sequencing. In total, 273 Gb and 227 Gb of raw data was generated from A. heterophyllus and A. altilis, respectively (Supplementary Materials: Table S1). We used the GCE software to evaluate the heterozygosity, and the results showed that the heterozygous ratio is 1.13% and 0.911% for A. altilis and A. heterophyllus, respectively. The K-mer distributions of A. altilis and A. heterophyllus showed two distinct peaks (Supplementary Materials: Figures S1 and S2), the first peak was the heterozygous peak, the second peak was the homozygous peak, where the second peak was confirmed as the main one for each of the species. Based on K-mer frequency methods [36], the A. heterophyllus and A. altilis genomes were estimated to be 1005 MB and 812 Mb, respectively (Supplementary Materials: Figure S1, Table S3). The genome sizes of A. altilis and A. heterophyllus were relatively close to the genome size of species in the genus Artocarpus based on existing data in the 1C-values database of 1.2 pg.

Using the SOAPdenovo2 program [41], all of the A. heterophyllus high-quality reads were assembled into 108,267 scaffolds, totaling 982 Mb (Table 1). The N50s of contigs and scaffolds were 27 kb and 548 kb, with the longest being 255 kb and 3.1 Mb, respectively (Table 1, Supplementary Materials: Figure S3). Similarly, for A. altilis, the N50s of contigs and scaffolds were 17 kb and 1.5 Mb with the longest being 174 kb and 7.4 Mb respectively (Table 1, Supplementary Materials: Figure S3). These results indicate the high quality of the assemblies for both species. The GC content of the A. heterophyllus and A. altilis genomes were 32.9% and 32.3%, respectively. The GC depth graphs and distributions indicated there was no contamination in the genome assemblies (Supplementary Materials: Figure S4).

Table 1.

Statistics of the genome assembly of A. altilis and A. heterophyllus.

| A. altilis | A. heterophyllus | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameters | Contig | Scaffold | Contig | Scaffold | ||||

| Length (bp) | Number | Length (bp) | Number | Length (bp) | Number | Length (bp) | Number | |

| N90 | 3361 | 52,085 | 183,851 | 637 | 4902 | 39,073 | 77,281 | 2115 |

| N50 | 16,898 | 13,662 | 1,536,010 | 151 | 26,681 | 9516 | 547,861 | 527 |

| N10 | 47,070 | 1284 | 5,076,803 | 14 | 82,850 | 846 | 1,422,119 | 54 |

| Total length | 803,695,923 | 833,038,871 | 930,343,435 | 982,020,585 | ||||

| Maximum length | 174,221 | 7,444,155 | 255,416 | 3,088,173 | ||||

| Total number ≥ 100 bp | 180,971 | 98,152 | 162,440 | 108,267 | ||||

| Total number ≥ 2000 bp | 61,693 | 4338 | 52,444 | 7263 | ||||

| N content (%) | 3.52 | 5.26 | ||||||

Evaluation of the quality and completeness of the draft genome assembly was done with the Benchmarking Universal Single-Copy Orthologs (BUSCO) datasets [38]. Of the total of 1440 BUSCO ortholog groups searched in the A. heterophyllus assembly, 932 (64.7%) BUSCO genes were “complete single-copy”, 437 (30.3%) were “complete duplicated”, 15 (1%) were “fragmented”, and 56 (4%) were “missing” (Table 2). Similarly, in A. altilis, 988 (68.6%) BUSCO genes were “complete single-copy”, 383 (26.6%) were “complete duplicated”, 14 (~1%) were “fragmented”, and 55 (3.8%) were “missing” (Table 2), suggesting that the quality of the genome assembly is high. From the 1440 core Embryophyta genes, 1371 (95.2%) and 1369 (95.1%) were identified in the A. altilis and A. heterophyllus assemblies, respectively (Table 2). We observed a significant difference in the number of duplicated core genes in A. altilis and A. heterophyllus (Table 2), which might be ascribed to the genome duplication in these species. The results also indicated that the assembly covered more than 90% of the expressed unigenes, (Table 3). As expected, after the comparative GC content analysis the close peak positions showed A. altilis, A. heterophyllus, and M. notabilis are closer than other species in GC content (Supplementary Materials: Figure S5).

Table 2.

BUSCO evaluation of genome assembly of A. altilis and A. heterophyllus.

| BUSCOs | A. altilis | A. heterophyllus | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | P (%) | N | P (%) | |

| Complete BUSCOs | 1371 | 95.20 | 1369 | 95.00 |

| Complete single-copy | 988 | 68.60 | 932 | 64.70 |

| Complete duplicated | 383 | 26.60 | 437 | 30.30 |

| Fragmented | 14 | 1.00 | 15 | 1.00 |

| Missing | 55 | 3.80 | 56 | 4.00 |

Abbreviation: BUSCO, Benchmarking universal single-copy orthologs; N, number; P, percentage of complete BUSCOs compared to the total BUSCOs.

Table 3.

The gene coverage based on transcriptome data.

| Species | Dataset | Number | Total Length (bp) | Base Coverage by Assembly (%) | Sequence Coverage by Assembly (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A. altilis | All | 141,626 | 165,794,671 | 87.7 | 97.92 |

| >200 bp | 141,626 | 165,794,671 | 87.7 | 97.92 | |

| >500 bp | 79,410 | 146,265,291 | 86.81 | 97.62 | |

| >1000 bp | 49,485 | 125,138,638 | 85.97 | 96.99 | |

| A. heterophyllus | All | 14,858 | 6,364,445 | 90.39 | 98.89 |

| >200 bp | 14,858 | 6,364,445 | 90.39 | 98.89 | |

| >500 bp | 2949 | 2,853,909 | 84.41 | 96.74 | |

| >1000 bp | 765 | 1,386,949 | 74.83 | 92.16 |

3.2. Gene Annotation

A combination of de novo and homology-based methods (using transcript data as evidence) were used to identify repeat sequences. We found that up to 51.01% of the A. heterophyllus and 52.04% of the A. altilis assembled sequences were repeat sequences, comprised mostly of transposable elements and tandem repeats. Interestingly, the amounts of these elements were higher than what is observed in orange (20%, 367 Mb) [80], peach (29.6%, 265 Mb) [81], pineapple (38.3%, 526 Mb) [82], and others (Table 4). This is consistent with the finding that larger fruit tree genomes often retained higher percentages of repetitive elements compared to the smaller fruit tree genomes [83]. Among the repetitive sequences, 37.0% and 46.0% were of the long terminal repeat (LTR) type, respectively (Table 4), indicating LTRs are the most abundant transposable elements in A. heterophyllus and A. altilis genomes.

Table 4.

Classification of predicted transposable elements in the genome of A. altilis and A. heterophyllus.

| A. altilis | A. heterophyllus | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Repeat Type | in Genome (%) | Length (bp) | in Genome (%) | Length (bp) |

| SINE | 0 | 1187 | 0.03 | 384,983 |

| LINE | 0.14 | 1,214,650 | 0.99 | 9,775,316 |

| LTR | 45.95 | 382,841,531 | 36.99 | 363,293,617 |

| DNA | 2.95 | 24,608,939 | 3.76 | 36,982,825 |

| Satellite | 0 | 34,585 | 0.3 | 3,001,478 |

| Simple repeat | 0.03 | 253,818 | 0.04 | 485,582 |

| Unknown | 5.4 | 45,013,282 | 12.23 | 120,128,962 |

| Total | 52.04 | 433,486,547 | 51.01 | 500,968,186 |

Using a comprehensive annotation strategy, we annotated a total of 35,858 A. heterophyllus genes and 34,010 A. altilis genes (Table 5). This was close to the number of genes (39,282) predicted in Dimocarpus longan, an exotic round to oval Asian fruit [83]. The average A. heterophyllus gene length was 3472 bp, the average length of the coding sequence (CDS) was 1241 bp, and the average number of exons per gene was 5.5 (Table 5, Supplementary Materials: Figure S6). We predicted a total of 466 rRNA, 159 miRNA, 1554 snRNA genes and 713 tRNA in A. altilis; and a total of 2706 rRNA, 168 miRNA, 1005 snRNA genes and 689 tRNA in A. heterophyllus (Table 6). Of 35,858 A. heterophyllus protein-coding genes, 35,076 (97.8%) had Nr homologs, 34,968 (97.5%) had TrEMBL homologs, 27,632 (77.1%) had InterPro homologs and 27,741 (77.4%) had SwissProt homologs (Table 7). Similar to A. heterophyllus, the average A. altilis gene size was 3545 bp, the average length of the CDS was 1253 bp, and the average number of exons per gene was 5.5 (Table 5). Of 34,010 A. altilis protein-coding genes, 33,353 (98.1%) had Nr homologs, 33,240 (97.7%) had TrEMBL homologs, 26,422 (77.7%) had InterPro homologs, and 26,689 (78.5%) had SwissProt homologs (Table 7). BUSCO evaluation showed that more than 89% of 1440 core genes were complete, suggesting an acceptable gene annotation for A. altilis and A. heterophyllus genomes (Supplementary Materials: Table S4)

Table 5.

Statistics of gene models of A. altilis, A. heterophyllus, and other species in Rosids.

| A. altilis | A. heterophyllus | F. vesca | M. domestica | M. notabilis | P. persica | Z. jujuba | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protein-coding gene number | 34,010 | 35,858 | 34,301 | 61,721 | 27,085 | 28,701 | 37,526 |

| Mean gene length (bp) | 3545.4 | 3472.2 | 2824.6 | 2692.5 | 2866.8 | 2464.8 | 3313.5 |

| Mean cds length (bp) | 1252.6 | 1241.5 | 1174.7 | 1141.4 | 1086.9 | 1210.8 | 1353.0 |

| Mean exons per gene | 5.4 | 5.5 | 5.1 | 4.8 | 4.6 | 4.9 | 5.5 |

| Mean exon length (bp) | 227.8 | 226.5 | 232.5 | 236.7 | 236.4 | 243.6 | 246.0 |

| Mean intron length (bp) | 509.6 | 497.7 | 407.1 | 405.8 | 494.6 | 315.8 | 435.7 |

Table 6.

Annotation of non-coding RNA genes in the A. altilis and A. heterophyllus genomes.

| Species | Type | Copy (w) | Average Length (bp) | Total Length (bp) | % of Genome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A. altilis | miRNA | 159 | 126.7 | 20,145 | 0.002418 |

| tRNA | 713 | 75.3 | 53,705 | 0.006447 | |

| rRNA | 466 | 183.2 | 85,353 | 0.010246 | |

| 18S | 76 | 551.4 | 41,907 | 0.005031 | |

| 28S | 98 | 125.5 | 12,296 | 0.001476 | |

| 5.8S | 32 | 135.6 | 4338 | 0.000521 | |

| 5S | 260 | 103.1 | 26,812 | 0.003219 | |

| snRNA | 1554 | 105.4 | 163,744 | 0.019656 | |

| CD-box | 1410 | 102.6 | 144,676 | 0.017367 | |

| HACA-box | 52 | 130.1 | 6765 | 0.000812 | |

| splicing | 92 | 133.7 | 12,303 | 0.001477 | |

| A. heterophyllus | miRNA | 168 | 126.3 | 21,227 | 0.002162 |

| tRNA | 689 | 75.2 | 51,813 | 0.005276 | |

| rRNA | 2706 | 268.2 | 725,709 | 0.073900 | |

| 18S | 654 | 737.5 | 482,306 | 0.049114 | |

| 28S | 920 | 123.6 | 113,667 | 0.011575 | |

| 5.8S | 242 | 151.6 | 36,699 | 0.003737 | |

| 5S | 890 | 104.5 | 93,037 | 0.009474 | |

| snRNA | 1005 | 108.2 | 108,724 | 0.011071 | |

| CD-box | 814 | 102.5 | 83,426 | 0.008495 | |

| HACA-box | 68 | 127.4 | 8665 | 0.000882 | |

| splicing | 123 | 135.2 | 16,633 | 0.001694 |

Table 7.

Statistics of functional annotation of protein-coding genes in the A. altilis and A. heterophyllus genomes.

| A. altilis | A. heterophyllus | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Values | Number | Percentage | Number | Percentage |

| Total | 34,010 | 100.0% | 35,858 | 100.0% |

| Nr | 33,353 | 98.1% | 35,076 | 97.8% |

| Swissprot | 26,689 | 78.5% | 27,741 | 77.4% |

| KEGG | 24,860 | 73.1% | 25,804 | 72.0% |

| COG | 12,875 | 37.9% | 13,408 | 37.4% |

| TrEMBL | 33,240 | 97.7% | 34,968 | 97.5% |

| Interpro | 26,422 | 77.7% | 27,632 | 77.1% |

| GO | 17,428 | 51.2% | 18,336 | 51.1% |

| Overall | 33,394 | 98.2% | 35,109 | 97.9% |

| Unannotated | 616 | 1.8% | 749 | 2.1% |

3.3. Gene Family Evolution and Comparison

Orthologous clustering analysis was conducted with the A. altilis and A. heterophyllus genomes following comparison with seven other plant genomes: A. thaliana, F. vesca, M. domestica, M. notabilis, P. mume, P. persica, and Z. jujuba. A Venn diagram shows that A. altilis, A. heterophyllus, A. thaliana, M. notabilis, and Z. jujuba contain a core set of 9462 gene families in common; there were 1028 orthologous families shared by three Moraceae species; while 329 gene families containing 515 genes were specific to A. altilis; and 420 gene families containing 907 genes were specific to A. heterophyllus (Figure 1C).

Of the 35,845 protein-coding genes in the A. heterophyllus genome, 28,969 were grouped into 15,768 gene families (of which 242 were A. heterophyllus-unique families) (Figure 1B, Supplementary Materials: Table S5). Of the 33,986 A. altilis protein-coding genes, 27,354 were grouped into 15,614 gene families (of which 136 were A. altilis-unique families) (Figure 1B, Supplementary Materials: Table S5).

Phylogenetic analysis showed that A. heterophyllus and A. altilis were more closely related to mulberry than to Jujube (Figure 1A), further supporting a previous phylogeny of Artocarpus [2]. CAFE [79] was used to identify gene families that had potentially undergone expansion or contraction. We found a total of 2822 expanded gene families and 1497 contracted families in A. heterophyllus, as well as 2034 expanded and 1800 contracted families in A. altilis (Figure 1A). The genes in the expanded and contracted families were assigned to Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathways [84]. The A. heterophyllus-expanded gene families were remarkably enriched in metabolism related pathways/functions, including starch and sucrose metabolism (ko00500, p = 0.003), glycan degradation (ko00511, p = 0.007), glycolysis/gluconeogenesis (ko00010, p = 0.016), and others (Supplementary Materials: Table S7). KEGG enrichment analysis of A. altilis revealed that pathways associated with photosynthesis, such as carbon fixation in photosynthetic organisms (ko00710, p = 0.017), other types of O-glycan biosynthesis (ko00514, p = 0.018), and photosynthesis (ko00195, p = 0.006) were particularly enriched (Supplementary Materials: Table S7).

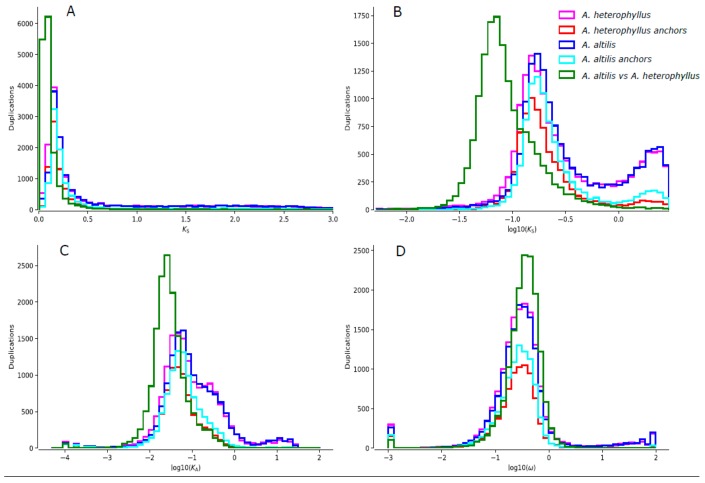

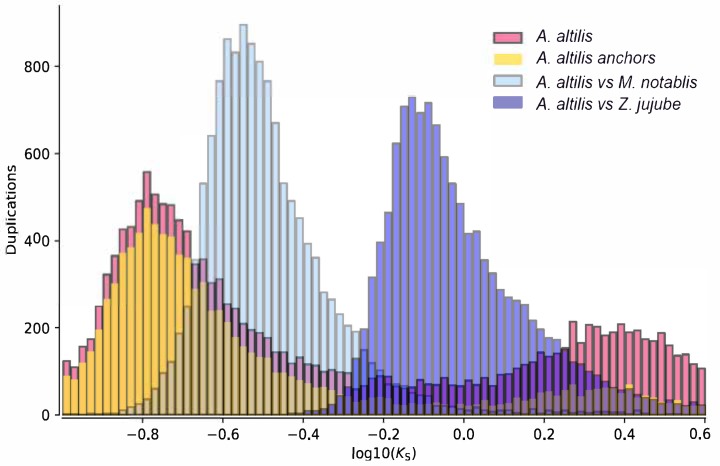

Collinearity between the largest orthologous scaffolds were determined (Figure S7B) and the result indicates conserved shared synteny. In order to determine whether there is any evidence for whole genome duplications in A. heterophyllus and A. altilis, the distance–transversion rates at four-fold degenerate sites (4DTv) was calculated (Figure 1D, Supplementary Materials: Figure S7A). Two 4DTv values that peaked at 0.07 and 0.08 for orthologs between A. heterophyllus, and between A. altilis, respectively, which highlighted the recent whole-genome duplication of these two species. The results of the Ks distributions mostly corroborate the findings of the 4DTv analysis. The results suggest that the whole genome duplication event was shared by A. altilis and A. heterophylus. Their divergence is recent, as suggested by the overlap of their WGD peaks (Figure 2), meaning that they have equal substitution, duplication, and loss rates. Thus, for further analysis (one-vs.-one synteny with the close relatives M. notabilis and Z. jujube), only A. altilis was used. These results suggest that the Artocarpus genome duplication event occurred after divergence from the common ancestor they share with M. notabilis (Figure 3), thus, between 62 and 10 MYA. A total of 33,614 gene pairs were identified in 2694 syntenic blocks.

Figure 2.

A graph showing the A. heterophyllus Ks distributions (pink) and the Ks distributions of its anchor pairs (red), A altilis Ks distributions (dark blue) and the distributions of its anchor pairs (light blue) overlaid with the Ks distributions of the one-to-one orthologs of A. heterophyllus, and A. altilis (green). (B) log transformed version of (A). (C,D) are the log transformed Ka and ω distributions, respectively.

Figure 3.

Ks distribution (dark pink) and anchor pair Ks distribution (yellow) of A. altilis in overlay with the results of whole paranome distributions between A. altilis and M. notabilis (light blue) and A. altilis and Z. jujube (dark blue).

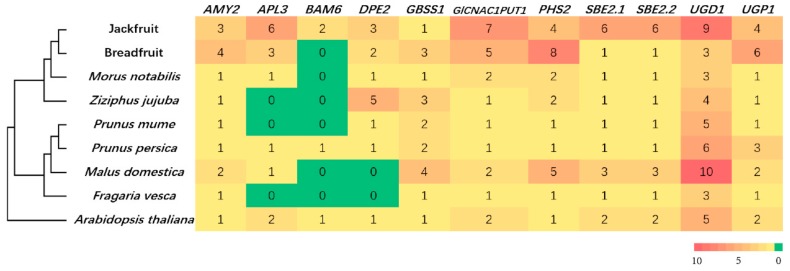

3.4. Gene Family Expansion and Tissue Specific Expression of Starch Synthesis-Related Genes

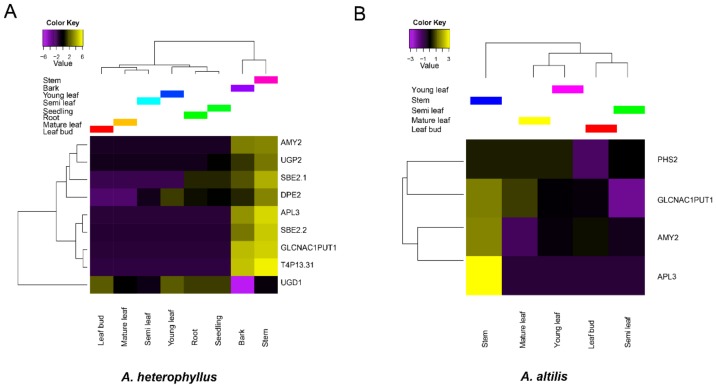

The copy number of starch synthesis related genes were compared between A. heterophyllus, A. altilis, closely related species, as well as some other starch-rich plant species (Figure 4). We observed a remarkable copy number expansion of the UGD1 gene in A. heterophyllus compared with the other species. The enzyme encoded by UGD1, catalyzes the conversion of Glucose-1-P into UDP-GlcA, thereby stalling the starch synthesis process [85] (Figure 4). Interestingly, the tissue-specific expression pattern of UGD1 contrasts with other starch synthesis genes in A. heterophyllus (Figure 5A). For instance, in A. heterophyllus there is a suppression of UDPG transcription in the stem, while the other starch biosynthesis genes are activated. However, differential expression of UGD1 was not shown in A. altilis (Figure 5B). This unusual expression pattern of UGD1, as well as the gene copy number expansion, might lead to the failure of starch accumulation in A. heterophyllus rather than A. altilis. However, this needs to be further validated by real-time qPCR for confirmation of the tissue-specific expression. For the GO enrichment, expansion of gene families were related to small molecule binding or single organism signaling (Supplementary Materials: Table S6) in A. altilis. Moreover, there were some expansion of gene families related to molecule binding, reproductive process, and cellular response to stimulus in A. heterophyllus. Gene families belonging to expanded pathways in A. altilis were mainly related to plant-pathogen interaction, lysine biosynthesis or photosynthesis. In contrast, the gene families that were expanded in A. heterophyllus belonged to pathways involving secondary metabolite biosynthesis, phenylpropanoid biosynthesis, and fatty acid metabolism. In contrast, the biosynthesis of secondary metabolites, phenylpropanoid biosynthesis, and fatty acid metabolism were enriched in the expanded gene families in A. heterophyllus (Supplementary Materials: Table S7).

Figure 4.

Copy number expansion of starch synthesis-related genes in A. heterophyllus and A. altilis.

Figure 5.

Tissue specific expression of starch synthesis-related genes in A. heterophyllus and A. altilis.

4. Conclusions

Here, we report the characterization of the genomes of jackfruit (A. heterophyllus) and breadfruit (A. altilis). The publication of these high-quality draft genomes and annotations may provide plant breeders and other researchers with useful information regarding trait biology and their subsequent improvement. In particular, we highlight genes unique to A. heterophyllus and A. altilis due to their high sugar and starch content, respectively, which are desirable characteristics in these edible plants. The information provided in the draft genome annotations can be used to accelerate genetic improvement of these crops. The availability of these genomes on the AOCC ORCAE platform (https://bioinformatics.psb.ugent.be/orcae/aocc) will enable various stakeholders to access and improve the annotations of these genomes.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/2073-4425/11/1/27/s1, Figure S1. K-mer (K = 17) analysis of the two genomes, Figure S2. Distribution of sequencing depth of the assembly data, Figure S3. Distribution of the length and number of the scaffold in two species, Figure S4. The distribution of GC content, Figure S5. Comparison of GC content across closely related species, Figure S6. Statistics of gene models in A. altilis, A. heterophyllus, F. vesca, M. domestica, M. notabilis, Prunus persica, and Ziziphus jujube, Figure S7. The collinearity between two species, Table S1. Statistics of the raw and clean data of DNA sequencing, Table S2. Summary statistics of the transcriptome data, Table S3. Estimation of the genome size based on K-mer statistics, Table S4. BUSCO evaluation of the annotated protein-coding genes in A. altilis and A. heterophyllus, Table S5. Analysis of gene families of different species, Table S6. Enriched GO terms (level 3) of genes in families with expansion, Table S7. Enriched pathways of genes in families with expansion.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: R.K., X.X., A.V.D., X.L., H.L.; data curation, S.K.S., M.L., B.S., S.-M.K., N.J.C.Z., Y.V.d.P.; formal analysis, S.K.S., M.L., A.Y., S.J.; funding acquisition, P.S.H., A.M., A.V.D., X.X., H.Y., X.L., H.L.; investigation, S.K.S., S.M., P.S.H.; methodology, M.L.; project administration, X.X., P.S.H., H.Y., X.L., H.L.; resources, R.K., S.M., R.J., S.-M.K., N.J.C.Z., Y.V.d.P., J.F., H.L.; software, M.L.; supervision, P.S.H., H.Y., A.V.D., Y.V.d.P., X.L., H.L.; validation, M.L.; visualization, A.Y.; writing—original draft, S.K.S.; writing—review and editing, M.L., A.Y., R.K., S.J., B.S., S.M., P.S.H., A.M., R.J., S.-M.K., N.J.C.Z., X.X., H.Y., A.V.D., Y.V.d.P., J.F., X.L., H.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by National Key Research and Development Program of China (No. 2016YFE0122000), the Shenzhen Municipal Government of China, (no. JCYJ20150831201123287 and No. JCYJ20160510141910129), the Guangdong Provincial Key Laboratory of Genome Read and Write (no. 2017B030301011), Illumina Greater Good Initiative and the NMPA Key Laboratory for Rapid Testing Technology of Drugs. We also thank Arthur Zwanepoel for his insights and technical assistance. This work is part of 10KP project.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Availability of Supporting Data

The genome and transcriptome data are deposited in the CNGB Nucleotide Sequence Archive (CNSA: http://db.cngb.org/cnsa; accession number CNP0000715, CNP0000486), and all the annotations are also available via AOCC ORCAE platform (https://bioinformatics.psb.ugent.be/orcae/aocc).

References

- 1.Zerega N.J., Supardi N., Motley T.J. Phylogeny and recircumscription of Artocarpeae (Moraceae) with a focus on Artocarpus. Syst. Bot. 2010;35:766–782. doi: 10.1600/036364410X539853. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Williams E.W., Gardner E.M., Harris R., III, Chaveerach A., Pereira J.T., Zerega N.J. Out of Borneo: Biogeography, phylogeny and divergence date estimates of Artocarpus (Moraceae) Ann. Bot. 2017;119:611–627. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcw249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zerega N.J., Gardner E.M. Delimitation of the new tribe Parartocarpeae (Moraceae) is supported by a 333-gene phylogeny and resolves tribal level Moraceae taxonomy. Phytotaxa. 2019;388:253–265. doi: 10.11646/phytotaxa.388.4.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.The Plant List. [(accessed on 24 April 2019)]; Available online: http://www.theplantlist.org/

- 5.Jarrett F. The syncarp of Artocarpus—A unique biological phenomenon [tropical fruits, tropical Asia] Gard. Bull. 1977;29:35–39. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang M.M., Gardner E.M., Chung R.C., Chew M.Y., Milan A.R., Pereira J.T., Zerega N.J. Origin and diversity of an underutilized fruit tree crop, cempedak (Artocarpus integer, Moraceae) Am. J. Bot. 2018;105:898–914. doi: 10.1002/ajb2.1094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gardner E.M., Gagné R.J., Kendra P.E., Montgomery W.S., Raguso R.A., McNeil T.T., Zerega N.J. A flower in fruit’s clothing: Pollination of jackfruit (Artocarpus heterophyllus, Moraceae) by a new species of gall midge, Clinodiplosis ultracrepidata sp. nov. (Diptera: Cecidomyiidae) Int. J. Plant Sci. 2018;179:350–367. doi: 10.1086/697115. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Witherup C., Ragone D., Wiesner-Hanks T., Irish B., Scheffler B., Simpson S., Zee F., Zuberi M.I., Zerega N.J. Development of microsatellite loci in Artocarpus altilis (Moraceae) and cross-amplification in congeneric species. Appl. Plant Sci. 2013;1:1200423. doi: 10.3732/apps.1200423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Campbell R.J., Ledesma N. The Exotic Jackfruit. Fairchild Tropical Botanic Garden; Coral Gables, FL, USA: 2003. p. 72. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Morton J.F., Dowling C.F. Fruits of Warm Climates. Volume 20534 JF Morton; Miami, FL, USA: 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Simon L., Shyamalamma S., Narayanaswamy P. Morphological and molecular analysis of genetic diversity in jackfruit. J. Hortic. Sci. Biotechnol. 2007;82:764–768. doi: 10.1080/14620316.2007.11512302. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Odoemelam S. Functional properties of raw and heat processed jackfruit (Artocarpus heterophyllus) flour. Pak. J. Nutri. 2005;4:366–370. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zerega N.J., Ragone D., Motley T.J. Complex origins of breadfruit (Artocarpus altilis, Moraceae): Implications for human migrations in Oceania. Am. J. Bot. 2004;91:760–766. doi: 10.3732/ajb.91.5.760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ragone D. Breadfruit—Artocarpus altilis (Parkinson) Fosberg. In: Rodrigues S., de Oliveira Silva E., de Brito E.S., editors. Exotic Fruits. Academic Press; New York, NY, USA: 2018. [(accessed on 26 June 2019)]. pp. 53–60. Available online: [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lincoln N.K., Ragone D., Zerega N., Roberts-Nkrumah L.B., Merlin M., Jones A. Grow us our daily bread: A review of breadfruit cultivation in traditional and contemporary systems. Hortic. Rev. 2018;46:299–384. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Murch S.J., Ragone D., Shi W.L., Alan A.R., Saxena P.K. In vitro conservation and sustained production of breadfruit (Artocarpus altilis, Moraceae): Modern technologies for a traditional tropical crop. Naturwissenschaften. 2008;95:99–107. doi: 10.1007/s00114-007-0295-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moo-Young M. Comprehensive Biotechnology. Elsevier; Amsterdam, The Netherlands: 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zerega N., Ragone D., Motley T. Species limits and a taxonomic treatment of breadfruit (Artocarpus, Moraceae) Syst. Bot. 2005;30:603–615. doi: 10.1600/0363644054782134. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zerega N., Wiesner-Hanks T., Ragone D., Irish B., Scheffler B., Simpson S., Zee F. Diversity in the breadfruit complex (Artocarpus, Moraceae): Genetic characterization of critical germplasm. Tree Genet. Genomes. 2015;11:4. doi: 10.1007/s11295-014-0824-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Laricchia K.M., Johnson M.G., Ragone D., Williams E.W., Zerega N.J., Wickett N.J. A transcriptome screen for positive selection in domesticated breadfruit and its wild relatives (Artocarpus spp.) Am. J. Bot. 2018;105:915–926. doi: 10.1002/ajb2.1095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zerega N.J., Ragone D. Toward a global view of breadfruit genetic diversity. Trop. Agric. 2016;93:77–91. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chang Y., Liu M., Liu X. The draft genomes of five agriculturally important African orphan crops. GigaScience. 2018;8 doi: 10.1093/gigascience/giy152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hendre P.S., Muthemba S., Kariba R., Muchugi A., Fu Y., Chang Y., Song B., Liu H., Liu M., Liao X. African Orphan Crops Consortium (AOCC): Status of developing genomic resources for African orphan crops. Planta. 2019;250:989–1003. doi: 10.1007/s00425-019-03156-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jones A.M.P., Ragone D., Aiona K., Lane W.A., Murch S.J. Nutritional and morphological diversity of breadfruit (Artocarpus, Moraceae): Identification of elite cultivars for food security. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2011;24:1091–1102. doi: 10.1016/j.jfca.2011.04.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu Y., Ragone D., Murch S.J. Breadfruit (Artocarpus altilis): A source of high-quality protein for food security and novel food products. Amino Acids. 2015;47:847–856. doi: 10.1007/s00726-015-1914-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jones A.M.P., Baker R., Ragone D., Murch S.J. Identification of pro-vitamin A carotenoid-rich cultivars of breadfruit (Artocarpus, Moraceae) J. Food Compos. Anal. 2013;31:51–61. doi: 10.1016/j.jfca.2013.03.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ranasinghe R., Maduwanthi S., Marapana R. Nutritional and Health Benefits of Jackfruit (Artocarpus heterophyllus Lam.): A Review. Int. J. Food Sci. 2019;2019 doi: 10.1155/2019/4327183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.De Bellis F., Malapa R., Kagy V., Lebegin S., Billot C., Labouisse J.P. New development and validation of 50 SSR markers in breadfruit (Artocarpus altilis, Moraceae) by next-generation sequencing. Appl. Plant Sci. 2016;4:1600021. doi: 10.3732/apps.1600021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Witherup C., Zuberi M.I., Hossain S., Zerega N.J. Genetic Diversity of Bangladeshi Jackfruit (Artocarpus heterophyllus) over Time and Across Seedling Sources. Econ. Bot. 2019;73:233–248. doi: 10.1007/s12231-019-09452-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gardner E.M., Laricchia K.M., Murphy M., Ragone D., Scheffler B.E., Simpson S., Williams E.W., Zerega N.J. Chloroplast microsatellite markers for Artocarpus (Moraceae) developed from transcriptome sequences. Appl. Plant Sci. 2015;3:1500049. doi: 10.3732/apps.1500049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gardner E.M. Evolutionary Transitions: Phylogenomics and Pollination of Artocarpus (Moraceae) Northwestern University; Evanston, IL, USA: 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gardner E.M., Johnson M.G., Ragone D., Wickett N.J., Zerega N.J. Low-coverage, whole-genome sequencing of Artocarpus camansi (Moraceae) for phylogenetic marker development and gene discovery. Appl. Plant Sci. 2016;4:1600017. doi: 10.3732/apps.1600017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.DNA Extraction for Plant Samples by CTAB. [(accessed on 24 December 2019)]; Available online: https://www.protocols.io/view/dna-extraction-for-plant-samples-by-ctab-pzqdp5w/metadata.

- 34.Luo R., Liu B., Xie Y., Li Z., Huang W., Yuan J., He G., Chen Y., Pan Q., Liu Y., et al. SOAPdenovo2: An empirically improved memory-efficient short-read de novo assembler. GigaScience. 2012;1:18. doi: 10.1186/2047-217X-1-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Teh B.T., Lim K., Yong C.H., Ng C.C.Y., Rao S.R., Rajasegaran V., Lim W.K., Ong C.K., Chan K., Cheng V.K.Y. The draft genome of tropical fruit durian (Durio zibethinus) Nat. Genet. 2017;49:1633. doi: 10.1038/ng.3972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liu B., Shi Y., Yuan J., Hu X., Zhang H., Li N., Li Z., Chen Y., Mu D., Fan W. Estimation of genomic characteristics by analyzing k-mer frequency in de novo genome projects. arXiv. 20131308.2012 [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kajitani R., Yoshimura D., Okuno M., Minakuchi Y., Kagoshima H., Fujiyama A., Kubokawa K., Kohara Y., Toyoda A., Itoh T. Platanus-allee is a de novo haplotype assembler enabling a comprehensive access to divergent heterozygous regions. Nat. Commun. 2019;10:1702. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-09575-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Simao F.A., Waterhouse R.M., Ioannidis P., Kriventseva E.V., Zdobnov E.M. BUSCO: Assessing genome assembly and annotation completeness with single-copy orthologs. Bioinformatics. 2015;31:3210–3212. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btv351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chang Z., Li G., Liu J., Zhang Y., Ashby C., Liu D., Cramer C.L., Huang X. Bridger: A new framework for de novo transcriptome assembly using RNA-seq data. Genome Biol. 2015;16:30. doi: 10.1186/s13059-015-0596-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kent W.J. BLAT--the BLAST-like alignment tool. Genome Res. 2002;12:656–664. doi: 10.1101/gr.229202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li R., Yu C., Li Y., Lam T.W., Yiu S.M., Kristiansen K., Wang J. SOAP2: An improved ultrafast tool for short read alignment. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1966–1967. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tarailo-Graovac M., Chen N. Using RepeatMasker to identify repetitive elements in genomic sequences. Curr. Protoc. Bioinform. 2009;25:4–10. doi: 10.1002/0471250953.bi0410s25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Han Y., Wessler S.R. MITE-Hunter: A program for discovering miniature inverted-repeat transposable elements from genomic sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:e199. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ellinghaus D., Kurtz S., Willhoeft U. LTRharvest, an efficient and flexible software for de novo detection of LTR retrotransposons. BMC Bioinform. 2008;9:18. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-9-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gremme G., Steinbiss S., Kurtz S. GenomeTools: A comprehensive software library for efficient processing of structured genome annotations. IEEE/ACM Trans. Comput. Biol. Bioinform. 2013;10:645–656. doi: 10.1109/TCBB.2013.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Steinbiss S., Willhoeft U., Gremme G., Kurtz S. Fine-grained annotation and classification of de novo predicted LTR retrotransposons. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:7002–7013. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chan P.P., Lowe T.M. GtRNAdb 2.0: An expanded database of transfer RNA genes identified in complete and draft genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:D184–D189. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv1309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Edgar R.C. MUSCLE: Multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:1792–1797. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Campbell M.S., Holt C., Moore B., Yandell M. Genome Annotation and Curation Using MAKER and MAKER-P. Curr. Protoc. Bioinform. 2014;48:4–11. doi: 10.1002/0471250953.bi0411s48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Haas B.J., Papanicolaou A., Yassour M., Grabherr M., Blood P.D., Bowden J., Couger M.B., Eccles D., Li B., Lieber M., et al. De novo transcript sequence reconstruction from RNA-seq using the Trinity platform for reference generation and analysis. Nat. Protoc. 2013;8:1494–1512. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2013.084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Haas B.J., Salzberg S.L., Zhu W., Pertea M., Allen J.E., Orvis J., White O., Buell C.R., Wortman J.R. Automated eukaryotic gene structure annotation using EVidenceModeler and the Program to Assemble Spliced Alignments. Genome Biol. 2008;9:R7. doi: 10.1186/gb-2008-9-1-r7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Stanke M., Schoffmann O., Morgenstern B., Waack S. Gene prediction in eukaryotes with a generalized hidden Markov model that uses hints from external sources. BMC Bioinform. 2006;7:62. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-7-62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lomsadze A., Ter-Hovhannisyan V., Chernoff Y.O., Borodovsky M. Gene identification in novel eukaryotic genomes by self-training algorithm. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:6494–6506. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Korf I. Gene finding in novel genomes. BMC Bioinform. 2004;5:59. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-5-59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nawrocki E.P., Burge S.W., Bateman A., Daub J., Eberhardt R.Y., Eddy S.R., Floden E.W., Gardner P.P., Jones T.A., Tate J., et al. Rfam 12.0: Updates to the RNA families database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:D130–D137. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lowe T.M., Chan P.P. tRNAscan-SE On-line: Integrating search and context for analysis of transfer RNA genes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:W54–W57. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tanabe M., Kanehisa M. Using the KEGG database resource. Curr. Protoc. Bioinform. 2012;38:1–12. doi: 10.1002/0471250953.bi0112s38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tatusov R.L., Koonin E.V., Lipman D.J. A Genomic Perspective on Protein Families. Science. 1997;278:631–637. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5338.631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Boeckmann B., Bairoch A., Apweiler R., Blatter M.C., Estreicher A., Gasteiger E., Martin M.J., Michoud K., O’Donovan C., Phan I., et al. The SWISS-PROT protein knowledgebase and its supplement TrEMBL in 2003. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:365–370. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Jones P., Binns D., Chang H.Y., Fraser M., Li W., McAnulla C., McWilliam H., Maslen J., Mitchell A., Nuka G., et al. InterProScan 5: Genome-scale protein function classification. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:1236–1240. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Finn R.D., Mistry J., Tate J., Coggill P., Heger A., Pollington J.E., Gavin O.L., Gunasekaran P., Ceric G., Forslund K., et al. The Pfam protein families database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:D211–D222. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Letunic I., Doerks T., Bork P. SMART 6: Recent updates and new developments. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:D229–D232. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mi H., Muruganujan A., Casagrande J.T., Thomas P.D. Large-scale gene function analysis with the PANTHER classification system. Nat. Protoc. 2013;8:1551–1566. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2013.092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Attwood T.K., Bradley P., Flower D.R., Gaulton A., Maudling N., Mitchell A.L., Moulton G., Nordle A., Paine K., Taylor P. PRINTS and its automatic supplement, prePRINTS. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:400–402. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Corpet F., Servant F., Gouzy J., Kahn D. ProDom and ProDom-CG: Tools for protein domain analysis and whole genome comparisons. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:267–269. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.He N., Zhang C., Qi X., Zhao S., Tao Y., Yang G., Lee T.-H., Wang X., Cai Q., Li D. Draft genome sequence of the mulberry tree Morus notabilis. Nat. Commun. 2013;4:2445. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Liu M.-J., Zhao J., Cai Q.-L., Liu G.-C., Wang J.-R., Zhao Z.-H., Liu P., Dai L., Yan G., Wang W.-J. The complex jujube genome provides insights into fruit tree biology. Nat. Commun. 2014;5:5315. doi: 10.1038/ncomms6315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Van Bel M., Diels T., Vancaester E., Kreft L., Botzki A., Van de Peer Y., Coppens F., Vandepoele K. PLAZA 4.0: An integrative resource for functional, evolutionary and comparative plant genomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;46:D1190–D1196. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx1002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zwaenepoel A., Van de Peer Y. wgd—Simple command line tools for the analysis of ancient whole-genome duplications. Bioinformatics. 2018;35:2153–2155. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bty915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Altschul S.F., Madden T.L., Schäffer A.A., Zhang J., Zhang Z., Miller W., Lipman D.J. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: A new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Van Dongen S.M. Ph.D. Thesis. Utrecht University; Utrecht, The Netherlands: 2000. Graph Clustering by Flow Simulation. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Yang Z. PAML 4: Phylogenetic analysis by maximum likelihood. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2007;24:1586–1591. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msm088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Price M.N., Dehal P.S., Arkin A.P. FastTree 2–approximately maximum-likelihood trees for large alignments. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e9490. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Proost S., Fostier J., De Witte D., Dhoedt B., Demeester P., Van de Peer Y., Vandepoele K. i-ADHoRe 3.0—Fast and sensitive detection of genomic homology in extremely large data sets. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;40:e11. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Li L., Stoeckert C.J., Jr., Roos D.S. OrthoMCL: Identification of ortholog groups for eukaryotic genomes. Genome Res. 2003;13:2178–2189. doi: 10.1101/gr.1224503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Wang Y., Tang H., Debarry J.D., Tan X., Li J., Wang X., Lee T.-h., Jin H., Marler B., Guo H., et al. MCScanX: A toolkit for detection and evolutionary analysis of gene synteny and collinearity. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:e49. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr1293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Tang H., Bowers J.E., Wang X., Ming R., Alam M., Paterson A.H. Synteny and collinearity in plant genomes. Science. 2008;320:486–488. doi: 10.1126/science.1153917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Guindon S., Dufayard J.F., Lefort V., Anisimova M., Hordijk W., Gascuel O. New algorithms and methods to estimate maximum-likelihood phylogenies: Assessing the performance of PhyML 3.0. Syst. Biol. 2010;59:307–321. doi: 10.1093/sysbio/syq010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.De Bie T., Cristianini N., Demuth J.P., Hahn M.W. CAFE: A computational tool for the study of gene family evolution. Bioinformatics. 2006;22:1269–1271. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Xu Q., Chen L.-L., Ruan X., Chen D., Zhu A., Chen C., Bertrand D., Jiao W.-B., Hao B.-H., Lyon M.P. The draft genome of sweet orange (Citrus sinensis) Nat. Genet. 2013;45:59. doi: 10.1038/ng.2472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Verde I., Abbott A.G., Scalabrin S., Jung S., Shu S., Marroni F., Zhebentyayeva T., Dettori M.T., Grimwood J., Cattonaro F. The high-quality draft genome of peach (Prunus persica) identifies unique patterns of genetic diversity, domestication and genome evolution. Nat. Genet. 2013;45:487. doi: 10.1038/ng.2586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Ming R., VanBuren R., Wai C.M., Tang H., Schatz M.C., Bowers J.E., Lyons E., Wang M.-L., Chen J., Biggers E. The pineapple genome and the evolution of CAM photosynthesis. Nat. Genet. 2015;47:1435. doi: 10.1038/ng.3435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Lin Y., Min J., Lai R., Wu Z., Chen Y., Yu L., Cheng C., Jin Y., Tian Q., Liu Q. Genome-wide sequencing of longan (Dimocarpus longan Lour.) provides insights into molecular basis of its polyphenol-rich characteristics. Gigascience. 2017;6:gix023. doi: 10.1093/gigascience/gix023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Kanehisa M., Goto S. KEGG: Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:27–30. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Oka T., Jigami Y. Reconstruction of de novo pathway for synthesis of UDP-glucuronic acid and UDP-xylose from intrinsic UDP-glucose in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. FEBS J. 2006;273:2645–2657. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2006.05281.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The genome and transcriptome data are deposited in the CNGB Nucleotide Sequence Archive (CNSA: http://db.cngb.org/cnsa; accession number CNP0000715, CNP0000486), and all the annotations are also available via AOCC ORCAE platform (https://bioinformatics.psb.ugent.be/orcae/aocc).