Abstract

Objective(s):

The contraception mandate of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) could reduce unintended pregnancies by increasing access and affordability of contraceptive resources, such as long-acting reversible contraceptives (LARCs). The objective of this study was to assess: (1) whether unintended pregnancies decreased following the contraception mandate, and (2) whether this decrease differed by demographic characteristics (race/ethnicity, insurance, or relationship status).

Study Design:

We used data on sexually active, fecund women of reproductive age from the National Survey of Family Growth (NSFG) (unweighted n=7,409). We used logistic regression to compare odds of unintended pregnancy between pre-mandate (2008–2010) and post-mandate (2013–2015) periods, both overall and stratified by demographic characteristics.

Results:

Paralleling an increase in LARC use (p<0.01), the percentage of women experiencing unintended pregnancy in the prior year decreased from 5.5% to 4.9% (p=0.45), and the percentage of pregnancies that were unintended in the prior year decreased from 44.7% to 37.9% (p=0.21) following the mandate. Overall, the odds of experiencing unintended pregnancy decreased 15% from the pre-mandate to post-mandate period (OR: 0.85, 95% CI: 0.62, 1.17; p=0.32), with the greatest reduction in odds observed in women with government-sponsored insurance (OR: 0.63, 95% CI: 0.41, 0.97; p=0.04).

Conclusions:

Unintended pregnancy decreased in NSFG respondents in the two years following the contraception mandate, but this observation may have been due to chance. The current study, however, is limited by its early study period which could under-estimate the mandate’s full effect. More effort is required to identify and address additional barriers to contraception and reproductive autonomy.

Keywords: Affordable Care Act, unintended pregnancy, contraception, policy, reproductive health

1.0. Introduction

Nearly 50% of all US pregnancies are unintended, meaning that they are mis-timed or unwanted[1]. Unintended pregnancies are associated with increased maternal strain (psychosocial, physical, and financial) and increased risk of delayed prenatal care and preterm birth[2–5]. Unintended pregnancies account for nearly $21 billion in public expenditures annually, as of 2010[6]. Furthermore, unintended pregnancies are disproportionately prevalent among women who are younger (18–24 years), unmarried, of lower income, of lower educational attainment, and women of color[2,3,5,7]. The most effective prevention of unintended pregnancy is consistent use of long-acting reversible contraceptives (LARCs), such as intra-uterine devices and implants, but many women are unable to utilize these methods due to access and/or cost barriers[4,5,7,8]. In response, the Affordable Care Act (ACA) sought to increase access and reduce cost barriers to contraceptive resources (products and services) through its contraception mandate[9].

As of August 1, 2012, the ACA contraception mandate required that all new health insurance plans provide FDA-approved female contraception and contraceptive services, without patient cost-sharing[9,10]. This mandate reduced out-of-pocket costs[11–15], and while evidence is mixed[11,15–18], some research suggests the mandate increased use of specific contraceptives such as LARCs[14,19,20]. Patterns of contraceptive use and effects of the mandate on contraceptive use also appear to differ by race/ethnicity, insurance type, and relationship status[7,19,21–25]. Whether the ACA contraception mandate reduced unintended pregnancies (i.e., via increased access and affordability of contraceptive resources), and whether that decrease was uniform across women of reproductive age, or if it differed by demographic characteristics (race/ethnicity, insurance type, or relationship status) remains unknown.

Determining the benefit of such policy as it relates to contraceptive use and unintended pregnancies is relevant in considering future policy-level intervention.[10,26,27]. Thus, the objective of the current study was to assess whether unintended pregnancies decreased following the ACA contraception mandate and whether this decrease was uniform across demographic subgroups.

2.0. Material and Methods

2.1. Design & Data Source

We used cross-sectional data from the 2006–2010 and 2013–2015 cycles of the National Survey of Family Growth (NSFG), a nationally representative survey of non-institutionalized men and women aged 15–44 years in the United States. Interviews of sampled individuals focused on reproductive health, family life, marriage, divorce, pregnancy, infertility, and use of contraception. More information on survey and sampling methodology, along with the publicly available datasets used in this analysis, can be found athttps://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nsfg/[28,29].

2.2. Study Population

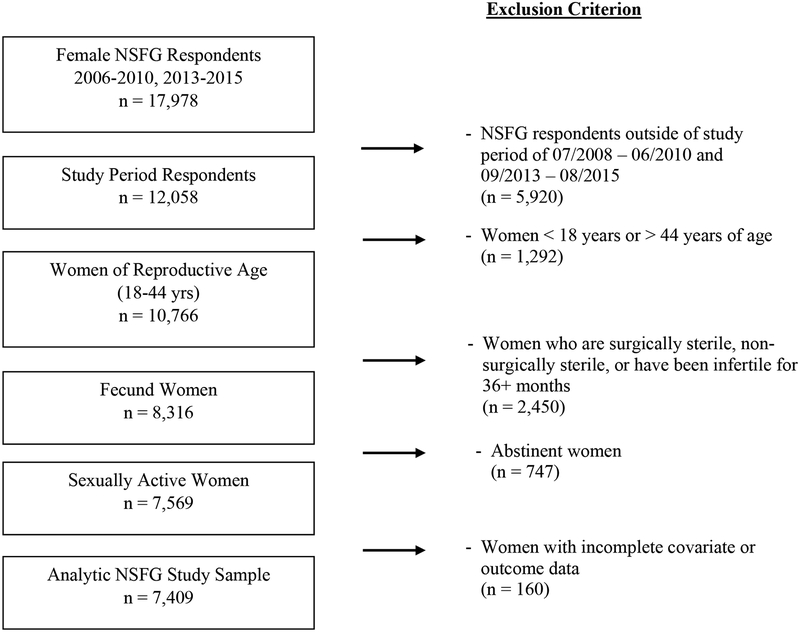

We included all NSFG interview responses from self-reported sexually-active and fecund women of reproductive age (18–44 years) from July 2008-June 2010 and September 2013-August 2015. We chose these inclusion dates to create comparable pre and post-mandate periods and loosely control for seasonality in unintended pregnancies. We included 24 months in both pre-mandate and post-mandate periods, with all four seasons equally represented in both periods (Table A.1). This resulted in an analytic sample size of n=7,409 (Figure 1) with n=939 pregnancies.

Figure 1.

Unweighted Analytic Sample Flow Chart for U.S. Women (18–44) in National Survey of Family Growth (NSFG), 2008–2010, 2013–2015

2.3. Outcome, Exposure, & Third Variable Measurements

We measured the outcome, unintended pregnancy in the prior 12 months, among all women (individual-level) as well as among pregnancies only (pregnancy-level). Interviewees were asked to recount lifetime pregnancy history (regardless of pregnancy outcome), and from this, we created a dichotomous outcome variable using conception date, interview date, and pregnancy intention to determine whether each pregnancy in the year prior to interview was unintended (unwanted or mis-timed) or intended. We calculated the proportion of all women who had at least one unintended pregnancy in the year prior to the interview.

The ACA contraception mandate was implemented nation-wide on August 1, 2012. As such, we defined the unexposed (“pre-mandate”) period to include surveys from July 2008-June 2010, and we defined the exposed (“post-mandate”) period to include interviews from September 2013-August 2015. We used the NSFG interview date to identify a respondent as part of the pre-mandate or post-mandate period.

We considered potential confounders to be factors known to be related to unintended pregnancy that may also have secular trends during the study period (insurance type, race/ethnicity, age, income level as a percent of federal poverty level (FPL), educational level, and relationship status.) We also considered contraception use in the prior year and current LARC use, which could represent either mediating or confounding pathways between the mandate and unintended pregnancy. We hypothesized the mandate would reduce unintended pregnancy by increasing the use of contraception (any or LARCs) through increased affordability and access to contraceptive resources. Without individual-level data to indicate temporality, however, we cannot determine whether contraception and/or LARC use is an intermediate effect or confounds the relationship between the mandate and unintended pregnancy.

2.4. Statistical Analyses

We described our sample using frequencies and weighted percentages for the entire study population and stratified by period. We formally compared distributions of sample characteristics in the pre- and post-mandate periods using chi-square analyses. Additionally, we graphically depicted LARC use and unintended pregnancy in each period. We performed unadjusted and adjusted logistic regression analyses on both the individual-level and pregnancy-level outcome (i.e., we assessed changes in the odds of an individual woman experiencing an unintended pregnancy and changes in the odds of a pregnancy being unintended). Because a small number of women (n=59) had multiple pregnancies in the prior year, we limited pregnancy-level analyses to only the most recent pregnancy in the 12 months prior to interview. As our independent variable, we considered period of interview. Thus, our unadjusted model (Model 1) can be written as:

In this model: β0 provides an estimate of the logit(PUnintendedPregnancy) in the pre-mandate period (period=0) and β1 provides an estimate of the difference in logit(PUnintendedPregnancy) in the postmandate period compared to the pre-mandate period. That is, β1 allows us to formally test if the odds of unintended pregnancy differ between pre- and post-mandate periods.

In our adjusted analyses, we considered potential confounders (insurance type, race/ethnicity, age group, income level, educational level, and relationship status) in Model 2. We further adjusted for contraceptive use in the past year in Model 3, and LARC use in Model 4. Finally, we stratified Model 1 by race/ethnicity, insurance type, and relationship status because we hypothesized that the effect of the mandate on unintended pregnancy would differ by these factors.

We performed a sensitivity analysis limiting our sample to women who reported using contraception in the prior year. Previously published evidence of increased LARC use paralleled by decreased sterilization and no change in non-use suggests women may be more likely to switch from one contraceptive to another than switch from non-use to use[19]. Thus, we hypothesized the mandate would have greater benefit among women who were already using contraception. All statistical analyses utilized NSFG weights and were completed using SAS 9.4. Institutional review board review was not needed for the analyses of these de-identified, secondary data.

3.0. Results

3.1. Sample Characteristics

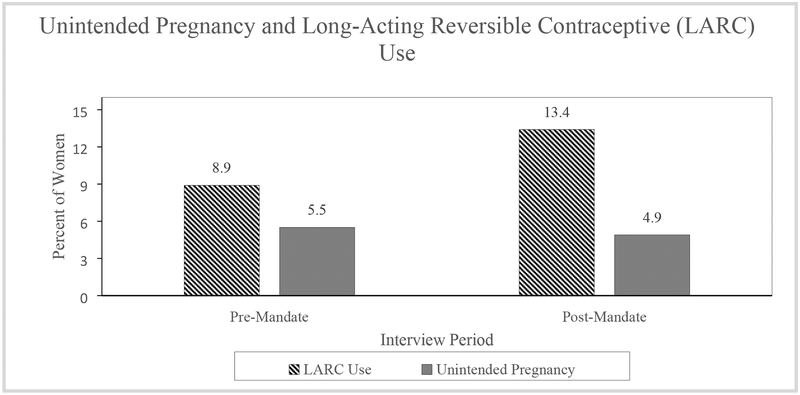

Table 1 provides a summary of sample characteristics. The majority of the sample respondents were: ≤ 34 years old (72.3%), non-Hispanic white (58.6%), privately insured (62.0%), single and non-cohabitating (45.2%), and utilizing contraceptives in the prior year (82.1%). Further, the majority of the sample respondents had an income between 100% and 399% of the FPL (53.5%) and a high school diploma or some college education (56.1%). These characteristics were fairly consistent between pre-mandate and post-mandate periods, with only four significant changes from pre-mandate to post-mandate: insurance coverage increased (p<0.01), highest and lowest income levels increased (p<0.01), education level increased (p<0.01), and current LARC use increased (p<0.01). Overall, 5.2% of the sample had experienced an unintended pregnancy in the prior year, with 5.5% of respondents in the pre-mandate period and 4.9% of respondents in the post-mandate period experiencing an unintended pregnancy (p=0.45). The percentage of pregnancies that were unintended decreased from 44.7% in the pre-mandate period to 37.9% in the post-mandate period. (p=0.21) The percentage of women experiencing an unintended pregnancy and using LARC during the pre- and post-mandate periods can be seen in Figure 2.

Table 1:

NSFG Analytic Sample Characteristics (n=7,409)

| Overall n (%)* | Pre-ACA Contraception Mandate n (%)* | Post-ACA Contraception Mandate n (%)* | P-Value*** | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||||

| Age Group | 0.46 | |||

| 18–25 years | 2,704 (35.3) | 1,466 (36.4) | 1,238 (34.3) | |

| 26–34 years | 2,925 (37.0) | 1,549 (36.9) | 1,376 (37.1) | |

| 35–44 years | 1,780 (27.7) | 906 (26.7) | 874 (28.7) | |

| Race/Ethnicity | 0.33 | |||

| Hispanic | 1,764 (18.7) | 937 (17.3) | 827 (19.9) | |

| NH White | 3,542 (58.6) | 1,921 (61.1) | 1,621 (56.2) | |

| NH Black | 1,618 (15.3) | 843 (15.0) | 775 (15.5) | |

| NH Other | 485 (7.5) | 220 (6.6) | 265 (8.4) | |

| Insurance Coverage | <0.01 | |||

| Private or Medi-gap | 3,960 (62.0) | 2,082 (60.5) | 1,878 (63.4) | |

| Government-sponsored** | 1,874 (19.3) | 893 (17.5) | 981 (20.9) | |

| Single service, Indian Health Service, or uninsured | 1,575 (18.8) | 946 (22.0) | 629 (15.7) | |

| Income Level | <0.01 | |||

| <100% FPL | 2,189 (23.3) | 1,074 (21.3) | 1,115 (25.2) | |

| 100–399% FPL | 3,840 (53.5) | 2,226 (60.2) | 1,614 (47.1) | |

| ≥400% FPL | 1,380 (23.2) | 621 (18.5) | 759 (27.6) | |

| Education Level | <0.01 | |||

| Less than HS | 1,195 (12.2) | 784 (15.7) | 411 (8.9) | |

| HS/Some college | 4,238 (56.1) | 2,139 (55.7) | 2,099 (56.6) | |

| College graduate | 1,353 (21.1) | 723 (20.3) | 630 (21.9) | |

| More than college | 623 (10.5) | 275 (8.3) | 348 (12.7) | |

| Relationship Status | 0.16 | |||

| Married | 2,272 (38.7) | 1,211 (38.3) | 1,061 (39.0) | |

| Single & cohabitating | 1,193 (16.2) | 593 (14.9) | 600 (17.3) | |

| Single & non-cohabitating | 3,944 (45.2) | 2,117 (46.8) | 1,827 (43.6) | |

| Contraception Use | ||||

| Contraception Use in Past 12 Months | 6,038 (82.1) | 3,208 (82.7) | 2,830 (81.5) | 0.37 |

| Current LARC use | 793 (11.2) | 326 (8.9) | 467 (13.4) | <0.01 |

| Unintended Pregnancy | ||||

| Individual | 468 (5.2) | 261 (5.5) | 207 (4.9) | 0.45 |

| Pregnancy**** | 457 (41.1) | 254 (44.7) | 203 (37.9) | 0.21 |

NSFG = National Survey of Family Growth, ACA = Affordable Care Act, NH = Non-Hispanic, FPL = Federal poverty level, HS = High school, LARC = Long-acting reversible contraceptives

Unweighted frequency and weighted percentage are provided. Frequency is based on individual-level dataset.

Includes Medicaid, Medicare, state-sponsored, CHIP, military (VA, CHAMPUS, TRICARE, CHAMP-VA), or other governmental

P-value of chi-square analyses comparing characteristic distributions before and after the ACA contraception mandate

Frequency is based on pregnancy-level dataset.

Figure 2:

Percentage of women experiencing unintended pregnancy and utilizing long-acting reversible contraceptives (LARCs) in the pre-mandate and post-mandate period in the NSFG 2008–2010, 2013–2015 analytic sample (unweighted n=7,409)

3.2. The Contraception Mandate and Unintended Pregnancy

3.2.1. Individual-level

In unadjusted analyses, the odds of unintended pregnancy in the post-mandate period were 0.89 (95% CI: 0.65, 1.21; p=0.45) times the odds in the pre-mandate period (Table 2, Model 1). After controlling for age, race/ethnicity, insurance, income, education, and relationship status, the odds of unintended pregnancy in the post-mandate period were 0.85 (95% CI: 0.62, 1.17; p=0.32) times the odds in the pre-mandate period (Table 2, Model 2).

Table 2:

Estimated relative odds of unintended pregnancy from pre-mandate to post-mandate at the individual level, as estimated from the unadjusted and adjusted logistic regression analyses of the NSFG 2008–2010, 2013–2015 analytic sample (unweighted n=7,409)

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | |

| Post-Mandate v. | 0.89 | 0.85 | 0.85 | 0.88 |

| Pre-Mandate | (0.65, 1.21) | (0.62, 1.17) | (0.62, 1.16) | (0.64, 1.21) |

OR=Odds Ratio, CI=Confidence Interval, LARC = Long-Acting Reversible Contraceptive

Model 1 includes: Period

Model 2 includes: Model 1 + Age Group + Race/Ethnicity + Insurance + Income Level + Education Level + Relationship Status

Model 3 includes: Model 2 + Contraceptive Use in Past Year

Model 4 includes: Model 2 + Current LARC Use

Similarly, the odds of unintended pregnancy in pre- and post-mandate periods did not differ significantly when contraceptive use in the past year was added to the covariates (p=0.31), nor when current LARC use was considered (p=0.42) (Table 2, Models 3 and 4). The sensitivity analysis corroborated these findings. (Table A.2)

To explore differences by demographic factors, we stratified Model 1 by race/ethnicity, insurance type, and relationship status (Table 3). Evidence of a reduction in odds of unintended pregnancy was found among women with ‘government-sponsored’ insurance group (OR=0.63, 95% CI: 0.41, 0.97; p=0.04). Null findings were supported for all other racial/ethnic, insurance type, and relationship status groups.

Table 3:

Estimated relative odds of unintended pregnancy from pre-mandate to post-mandate at the individual level, as estimated from the stratified unadjusted logistic regression analyses of the NSFG 2008–2010, 2013–2015 analytic sample (n=7,409) [OR (95% CI) presented]

| Post-Mandate v. Pre-Mandate | OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|

| Race/Ethnicity | |

| NH White/NH Other (unweighted n=4,027) | 0.88 (0.57, 1.37) |

| NH Black (unweighted n=1,618) | 0.89 (0.57, 1.41) |

| Hispanic (unweighted n=1,764) | 0.82 (0.50, 1.34) |

| Insurance Status | |

| Private or Medi-Gap (unweighted n=3,960) | 1.16 (0.70, 1.93) |

| Government-sponsored** (unweighted n=1,874) | 0.63 (0.41, 0.97) |

| Single service, Indian Health Service, or uninsured (unweighted n=1,575) | 0.76 (0.41, 1.39) |

| Relationship Status | |

| Married (unweighted n=2,272) | 0.75 (0.44, 1.27) |

| Unmarried (unweighted n=5,137) | 0.96 (0.68, 1.36) |

OR=Odds Ratio, CI=Confidence Interval, NH = Non-Hispanic

Model includes: Period

Includes Medicaid, Medicare, state-sponsored, CHIP, military (VA, CHAMPUS, TRICARE, CHAMP-VA), or other governmental

3.2.2. Pregnancy-level

Findings in the pregnancy-level analyses (unadjusted, adjusted, sensitivity, and subgroup) were consistent with the null findings of the individual-level analyses (Tables A.3–A.5).

4.0. Discussion

Our results from a nationally representative sample of sexually active fecund women aged 18–44 in the US show that, although the overall odds of a woman having an unintended pregnancy and the odds of a pregnancy being unintended were lower in the two years following the ACA contraception mandate, these observed declines may have been due to chance. Subgroup analyses, however, indicated a significant 37% decrease in the odds of unintended pregnancy for women with ‘government-sponsored’ insurance. This was not observed in any other demographic subgroups, and could suggest that the joint-effect of the mandate with other ACA provisions (e.g. Medicaid expansion and the healthcare insurance marketplace) may have contributed to a greater reduction in unintended pregnancy.

Although we hypothesized that the contraception mandate would reduce unintended pregnancy via improved affordability and access to contraceptive resources, cost and access may represent only two of many barriers that women face in obtaining adequate resources to prevent unintended pregnancy. Other potential barriers – that would not be impacted by the mandate – include personal and partner contraceptive preferences, reproductive autonomy in sexual partnerships, prescribing biases, and stigma[7,30–32]. Furthermore, the mandate influenced access and affordability for women with health insurance, but did not influence who had health insurance. For this reason, the mandate’s effect on unintended pregnancy may have been limited prior to the full roll-out of the ACA.

Prior to the full roll-out of the ACA, the mandate only affected the health insurance coverage of women who were insured through non-exempt/non-grandfathered plans and either: (1) did not have contraceptive coverage through their plan, or (2) had cost-sharing for contraceptives with their plan[10]. The mandate had the potential to increase access for the former group of women, and the potential to increase affordability for the latter. Prior to the mandate, Medicaid and the vast majority of private plans (89%) already covered contraceptives – often with cost-sharing in private plans[33,34]. As such, the mandate’s greatest potential benefit was in reducing out-of-pocket costs for insured women that already had contraceptive coverage. While reducing the cost-burden may motivate changes in contraceptive choice, these changes may not influence unintended pregnancy if the women affected were already at lower risk for unintended pregnancy because of their access to contraceptive resources prior to the mandate.

We are not aware of any other studies that look at the effect of the ACA contraception mandate on unintended pregnancy, but our finding in the unadjusted analyses that LARC use increased post-mandate is consistent with prior studies[14,19,20] – although one study indicated that this increase occurred with a decrease in sterilization and no change in nonuse[19]. Our finding is inconsistent, however, with prior studies that did not find significant increases in LARC use post- mandate[15,18]. Studies with null findings utilized study periods of 2010–2013 and 20122015 while studies with positive findings utilized study periods of 2008–2015, 2006–2015, and 2008–2014. Administrative health plan data of employer-sponsored plans and weighted survey data were used both in studies with null and positive findings. Thus, differences in findings may be due to study period definition.

Our study is strengthened by the fact that it uses nationally representative data collected through probabilistic sampling methodologies. Our study is, however, limited by its cross-sectional design, limited follow-up length, and self-reported outcome measure. With only cross-sectional data available, we cannot track individuals’ behavior over time, so we are unable to track individual contraceptive choice or consistency. An ideal analytic approach might have been a difference-in-difference analysis comparing changes in unintended pregnancy among those affected by the mandate and those not affected; in the absence of data on women’s exact health insurance plan, we could not conduct such an analysis. Moreover, we did observe a decrease in unintended pregnancy—overall and among most subgroups—following the mandate, but this may have been due to chance. Due to a short follow-up period and self-reported outcome, the mandate’s effect could be under-estimated in this study. While the mandate was implemented on August 1, 2012, its benefit would not have been instantaneous. Our post-period may precede the mandate’s effect by including interviews from as early as September 2013. Further, the full effect of the mandate includes its independent effect and its joint effect with other ACA provisions since the number of women affected by the mandate likely increased as insurance coverage increased with the full roll-out of the ACA in 2014. To capture the joint effect, we would need more recent NSFG data. The CDC advises that at least 24 months of NSFG data be used to produce valid estimates[35]. Thus, we cannot use a subset of the 2013–2015 cycle to isolate the joint effect. Additionally, if women with pregnancies that ended in abortion are less likely to disclose these pregnancies, self-reported pregnancy history could result in under-estimation of total number of pregnancies and Unintended pregnancies. Since this under-estimation is unlikely to differ by period, this would result in non-differential measurement error, which could bias results in the direction of the null. Replication in a larger dataset with more power would be useful, but few large, national datasets include information on unintended pregnancy both before and after the mandate.

Despite these limitations, we believe these analyses provide insight regarding the short term benefit and limitations of one provision of the ACA. While there was evidence that the mandate is associated with greater use of the most effective methods of contraception such as LARCs, our results suggest that the ACA contraception mandate alone is not associated with reduced unintended pregnancy two years following its implementation. With more than $20 billion in public expenditures going toward unintended pregnancies annually, and nearly half of all pregnancies being unintended – the burden of which is borne disproportionately by women who are younger, of lower socioeconomic status, and women of color – these results suggest more effort is required to identify and address additional barriers to effective contraception and reproductive autonomy.

Supplementary Material

Implications.

This study considers whether the roll-out of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) contraception mandate is associated with a reduction in unintended pregnancy. This contributes to evaluation of the ACA’s impact, and more broadly, to the development of policy-level interventions that deconstruct barriers to contraceptive resources and reproductive autonomy.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Claudia Holzman, Professor of Epidemiology and Biostatistics at Michigan State University, for her thoughtful inquiries, and the discussion they provoked, regarding the methodology used in this manuscript.

Funding. This research was funded by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (R01HD095951, PI: Margerison).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declarations of interest: The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- [1].Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Unintended Pregnancy Prevention 2015. https://www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/unintendedpregnancy/index.htm (accessed December 5, 2018).

- [2].Finer LB, Henshaw SK Disparities in Rates of Unintended Pregnancy In the United States, 1994 and 2001. Perspect Sex Reprod Health 2006;38:90–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Finer LB, Zolna MR Declines in Unintended Pregnancy in the United States, 2008–2011. N Engl J Med 2016;374:843–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Carper TR, Kane A, Sawhill I Following the Evidence to Reduce Unplanned Pregnancy and Improve the Lives of Children and Families. Ann Am Acad 2018;6788:199–205. [Google Scholar]

- [5].Guttmacher Institute. Unintended Pregnancy in the United States. New York, NY: 2019. [Google Scholar]

- [6].Sonfield A, Kost K Public Costs from Unintended Pregnancies and the Role of Public Insurance Programs in Paying for Pregnancy-Related Care. New York, NY: 2015. [Google Scholar]

- [7].Parks C, Peipert JF Eliminating Health Disparities in Unintended Pregnancy with Long-Acting Reversible Contraception (LARC). Am J Obstet Gynecol 2017;214:681–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Gyllenberg F, Juselius M, Gissler M, Heikinheimo O Long-Acting Reversible Contraception Free of Charge, Method Initiation, and Abortion Rates in Finland. Am J Public Health 2018;108:538–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Tschann M, Soon R Contraceptive Coverage and the Affordable Care Act. Obstet Gynecol Clilnics North Am 2017;42:605–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Sobel L, Salganicoff A, Gomez I State and Federal Contraceptive Coverage Requirements: Implications for Women and Employers Requirements. San Franciso, CA; Washington DC: 2018. [Google Scholar]

- [11].Arora P, Desai K Impact of Affordable Care Act coverage expansion on women’s reproductive preventive services in the United States. Prev Med (Baltim) 2016;89:224–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Finer LB, Sonfield A, Jones RK Changes in out-of-pocket payments for contraception by privately insured women during implementation of the federal contraceptive coverage requirement. Contraception 2014;89:97–102. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2013.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Sonfield A, Tapales A, Jones RK, Finer LB Impact of the federal contraceptive coverage guarantee on out-of-pocket payments for contraceptives: 2014 update. Contraception 2015;91:44–8. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2014.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Dalton VK, Carlos RC, Kolenic GE, Moniz MH, Tilea A, Kobernik EK, et al. The impact of cost sharing on women’s use of annual examinations and effective contraception. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2018;219:93.e1–93.e13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Pace LE, Dusetzina SB, Keating NL Early impact of the Affordable Care Act on uptake of longacting reversible contraceptive methods. Med Care 2017;54:811–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Kim NH, Look KA Effects of the Affordable Care Act’s contraceptive coverage requirement on the utilization and out-of-pocket costs of prescribed oral contraceptives. Res Soc Adm Pharm 2018;14:479–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Riddell L, Taylor R, Alford O Impact of the Affordable Care Act on Use of Covered Contraceptives in Women Ages 20–25. Popul Health Manag 2018;21:231–4. doi: 10.1089/pop.2017.0050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Bearak JM, Jones RK Did Contraceptive Use Patterns Change after the Affordable Care Act ? A Descriptive Analysis. Women’s Heal Issues 2017;27:316–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Kavanaugh ML, Jerman J Contraceptive method use in the United States: trends and characteristics between 2008, 2012 and 2014. Contraception 2018;97:14–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Carlin CS, Fertig AR, Dowd BE Affordable Care Act’s Mandate Eliminating Contraceptive Cost Sharing Influenced Choices Of Women With Employer Coverage. Health Aff 2016;35:1608–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Wu J, Meldrum S, Dozier A, Stanwood N, Fiscella K Contraceptive nonuse among US women at risk for unplanned pregnancy. Contraception 2008;78:284–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Jones J, Mosher W, Daniels K Current contraceptive use in the United States, 2006–2010, and changes in patterns of use since 1995. Natl Health Stat Report 2012:1–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Raine T, Minnis AM, Padian NS Determinants of contraceptive method among young women at risk for unintended pregnancy and sexually transmitted infections. Contraception 2003;68:19–25. doi: 10.1016/S0010-7824(03)00107-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Frost JJ, Singh S, Finer LB Factors Associated with Contraceptive Use and Nonuse, United States, 2004. Perspect Sex Reprod Health 2007;39:90–9. doi: 10.1363/3909007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Dehlendorf C Racial/ethnic disparities in contraceptive use: Variation by age and women’s reproductive experiences. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2015;210:1–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].O’Donnell J Trump offers broad leeway to employers to drop birth control coverage. USA Today 2017. https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/2017/10/06/trump-offer-broad-leway-employersrefuse-provide-birth-control-coverage-without-religious-reason/738869001/ (accessed December 5, 2018). [Google Scholar]

- [27].Brindis CD, Freund KM, Baecher-Lind L, Bairey Merz CN, Carnes M, Gulati M, et al. The Risk of Remaining Silent: Addressing the Current Threats to Women’s Health. Women’s Heal Issues 2017;27:621–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS). 2006–2010 National Survey of Family Growth Public Use Data and Documentation 2011. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nsfg/nsfg_2006_2010_puf.htm.

- [29].National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS). 2013–2015 National Survey of Family Growth Public Use Data and Documentation 2016. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nsfg/nsfg_2013_2015_puf.htm.

- [30].Madden T, Allsworth JE, Hladky KJ, Secura GM, Peipert JF Intrauterine contraception in Saint Louis: A survey of obstetrician and gynecologists’ knowledge and attitudes. Contraception 2011;81:1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Nikolajski C, Miller E, McCauley H, Akers A, Schwarz EB, Freedman L, et al. Race and reproductive coercion: A qualitative assessment. Women’s Heal Issues 2016;25:216–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Katz J, Poleshuck EL, Beach B, Olin R Reproductive Coercion by Male Sexual Partners: Associations With Partner Violence and College Women’s Sexual Health. J Interpers Violence 2017;32:3301–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Sonfield A, Benson Gold R, Frost JJ, Darroch JE. U.S. Insurance Coverage of Contraceptives and the Impact Of Contraceptive Coverage Mandates, 2002. Perspect Sex Reprod Health 2004;36:72–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Social Security Act, sec. 1916. (a)(2)(D). n.d.

- [35].Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ) about the NSFG. 2013–2015 NSFG User’s Guid, Hyattsville, MD: 2015, p. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.