Abstract

Background

Cotton Verticillium wilt is one of the most devastating diseases for cotton production in the world. Although this diseases have been widely studied at the molecular level from pathogens, the molecular basis of V. dahliae interacted with cotton has not been well examined.

Results

In this study, RNA-seq analysis was carried out on V. dahliae samples cultured by different root exudates from three cotton cultivars (a susceptible upland cotton cultivar, a tolerant upland cotton cultivar and a resistant island cotton cultivar) and water for 0 h, 6 h, 12 h, 24 h and 48 h. Statistical analysis of differentially expressed genes revealed that V. dahliae responded to all kinds of root exudates but more strongly to susceptible cultivar than to tolerant and resistant cultivars. Go analysis indicated that ‘hydrolase activity, hydrolyzing O-glycosyl compounds’ related genes were highly enriched in V. dahliae cultured by root exudates from susceptible cotton at early stage of interaction, suggesting genes related to this term were closely related to the pathogenicity of V. dahliae. Additionally, ‘transmembrane transport’, ‘coenzyme binding’, ‘NADP binding’, ‘cofactor binding’, ‘oxidoreductase activity’, ‘flavin adenine dinucleotide binding’, ‘extracellular region’ were commonly enriched in V. dahliae cultured by all kinds of root exudates at early stage of interaction (6 h and 12 h), suggesting that genes related to these terms were required for the initial steps of the roots infections.

Conclusions

Based on the GO analysis results, the early stage of interaction (6 h and 12 h) were considered as the critical stage of V. dahliae-cotton interaction. Comparative transcriptomic analysis detected that 31 candidate genes response to root exudates from cotton cultivars with different level of V. dahliae resistance, 68 response to only susceptible cotton cultivar, and 26 genes required for development of V. dahliae. Collectively, these expression data have advanced our understanding of key molecular events in the V. dahliae interacted with cotton, and provided a framework for further functional studies of candidate genes to develop better control strategies for the cotton wilt disease.

Keywords: Root exudates; Transcriptome; Verticillium dahliae; Hydrolase activity, hydrolyzing O-glycosyl compounds hydrolase

Background

Verticillium dahliae (V. dahliae), a fungal pathogen causing Verticillium wilt, is extremely persistent in the soil and has a broad host range [1, 2]. Microsclerotia of V. dahliae overcome the mycostatic activity of the soil and germinate towards roots in the presence of root exudates [3]. The hyphae enter host plants by formation of an infection structure, known as hyphopodium, to develop a penetration peg to pierce root epidermal cells [4]. They enter and clog the xylem vessels, resulting in leaf curl, necrosis, defoliation, vascular tissue wilt, and discoloration [5]. During its life cycle, cotton is continuously threatened by V. dahliae. More than half of the cotton fields in China are affected by V. dahliae and can lead to 30–50% reduction in yield, and even totally wipe out the crop. Verticillium wilt is one of the most severe cotton diseases not only in China but also in other countries. Outbreak of the disease causes substantial economic loss due to significant reduction in fiber yield and quality.

To combat the challenge of V. dahliae, resistance cotton has evolved multiple layers of defense mechanisms, including tissue composition, physiological and biochemical resistance, during the long time period of coexistence and arm race [6–10]. In recent years, with the application of genomics, transcriptomics and proteomics, great progress has been made in understanding the molecular mechanism underlying cotton’s resistance against V. dahliae, and a number of genes related to V. dahliae resistance have been identified [11–16]. On the other hand, in view of the co-evolving relationship between cotton and V. dahliae, it is also of vital importance to study the molecular mechanisms determining the pathogenicity of V. dahliae. With the completion of genome sequencing of V. dahliae and the development of bioinformatics tools, genomic and transcriptomic sequence information of V. dahliae provide us opportunity for better understanding the pathogenicity of V. dahliae. Analyses of V. dahliae transcriptomes during microsclerotia formation and early infection stage have given us a snapshot of the genes important for development, microsclerotia formation and infection of V. dahliae [17–20]. For instance, VdPKAC1, VMK1, VdMsb, VdGARP1, VDH1, Vayg1 and VGB were found to be involved in the microsclerotia formation and pathogenic process of V. dahliae [3, 21–26]; VdSNF1 and VdSSP1 are related to cell wall degradation [27, 28]; VdNEP, VdpevD1, VdNLP1 and VdNLP2 encode effector proteins are involved in the pathogenic reaction [29–32]; VdFTF1, Vta2 and VdSge1 encode transcriptional factors regulating pathogenic genes [33–35]. However, due to the complexity of the pathogenic molecular mechanism of V. dahliae, we still know little about the role of these genes in the interaction between V. dahliae and cotton.

Successful pathogens must be able to recognize and overcome host-plant defense responses [36]. V. dahliae invades cotton through the root system [4, 37], therefore, the biological effect of the root exudates is expected to be crucial for successful infection of V. dahliae. Not surprisingly, root exudates have been found to be closely related to plant resistance [38, 39]. The root exudates of cotton are rich in amino acids and sugars. Compared with the root exudates from the susceptible cotton cultivars, the root exudates from resistant cotton cultivars lacked aspartic acid, threonine, glutamic acid, alanine, isoleucine, leucine, phenylalanine, lysine and proline, but contained arginine that was absent in the susceptible cottons. No significant difference of saccharide was found in the root exudates between the susceptible and resistant cultivars, but the root exudates of the susceptible cultivars had a much higher concentrations of glucose, fructose and sucrose than that of the resistant ones [40]. Root exudates from the resistant and susceptible cottons inhibited and promoted the growth of V. dahliae, respectively [40–42]. However, we know nothing about the molecular basis behind this observation.

In this study, we investigated the effects of root exudates from cotton cultivars susceptible, tolerant or resistant to V. dahliae on the development of the pathogen and performed a time course expression analysis of V. dahliae genes using RNA-seq to (1) compare transcriptomic profiles of V. dahliae in response to root exudates from cottons with different level of V. dahliae resistance, (2) identify biological processes in V. dahliae affected by different root exudates based on analysis of Gene Ontology (GO) terms of the differentially expressed genes, and (3) identify genes involved in the initial steps of roots infection and likely in pathogenesis of V. dahliae. We expect that identification of pathogenic genes in V. dahliae would provide us clues to develop novel strategies for breeding novel cotton germplasm resistant to V. dahliae and/or effective crop management schemes to minimize the infection of V. dahliae.

Methods

Cotton cultivars and V. dahliae strain

Two Upland cotton (G. hirsutum L.) cultivars Xinluzao 8 (X) and Zhongzhimian 2 (Z), and one Sea island (G. barbadense L.) cultivar Hai7124 (H) used in this study were collected from the Institute of Cotton Research of Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences (Anyang, China) and Shihezi Academy of Agricultural Sciences (Shihezi, China). The 3 cotton cultivars were authorized for only scientific research purpose, and were deposited in the original institutes and College of Agriculture in Shihezi University. The highly virulent V. dahliae strain, V991, was provided and confirmed by the Institute of Cotton Research of Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences (Anyang, China). The growth conditions of the cotton cultivars, the preparation of V.dahliae spore suspensions for infection assays and determination of Disease Index after inoculation were described previously [43, 44].

Collection of root exudates

Xinluzao 8, Zhongzhimian 2 and Hai7124 are susceptible, tolerant and resistant to V. dahliae, respectively. Cotton seeds were surface sterilized by immersion in 1% (w/v) NaClO and rinsed three times with sterile distilled water. After germination in petri dish, the seeds were sown in sand that were treated by soaking in dilute suphuric acid and sterilized by high temperature. For each cultivar 18 germinated seeds were evenly planted in 2 pots and were grown in a greenhouse with a photoperiod of 16 h light/8 h darkness at 28 °C. The cotton seedlings were fed with Hoagland nutrient solution every 3 days (3d). After 45d, the plants were removed from sand, and the sand was immersed with 2 L distilled water to sufficiently dissolve root exudates. The water solution was then filtered with a bacterial filter (0.22 μm in diameter) and concentrated to 0.5 L in a freeze dryer.

V. dahliae strain culture

V. dahliae strain, V991, was maintained in 20% glycerol at − 80 °C at the Key Laboratory of Oasis Eco-agriculture in Shihezi University. The stored conidia of V991 were incubated on a potato–dextrose agar plate for 1 week and then inoculated into Czapek broth for 5d at 25 °C 180 rpm under dark donditions. The fresh conidia and spores were then collected to be used in the root exudate treatment experiments. For each cultivar, 0.5 g of V991 conidia and spores were suspended in 5 mL of root exudates. After cultured for 6, 12, 24 or 48 h at 25 °C 220 rpm in 10 mL centrifugal tubes, V991 conidia and spores (Vd-X-6, Vd-X-12, Vd-X-24, Vd-X-48, Vd-Z-6, Vd-Z-12, Vd-Z-24, Vd-Z-48, Vd-H-6, Vd-H-12, Vd-H-24 and Vd-H-48) were collected for RNA extraction. The same amount of V991 conidia and spores suspended in water and cultured for 0, 6, 12, 24 or 48 h were done in parallel (Vd-0, Vd-W-6, Vd-W-12, Vd-W-24 and Vd-W-48). Each time point had two biological replicates. In total, 34 samples were collected and used in RNA-seq.

RNA extraction

Total RNA of V. dahliae was isolated using the RNA simple total RNA kit (Tiagen, Beijing, China) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. All RNA samples were treated with RNase-free DNase I. Degradation and contamination of RNA were assessed by using agarose gel electrophoresis. The RNA purity and integrity were determined by a NanoDrop® 2000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, Wilmington, DE, USA) and an Agilent 2100 bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). The RNA concentration was measured by a Qubit® 2.0 Fluorometer (Thermo Scientific, Wilmington, DE, USA). High quality RNA samples were chosen for RNA-Seq analyses.

RNA-Seq library construction and sequencing

RNA-Seq library preparation and sequencing were performed at Novogene Bioinformatics Technology Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China) using the standard Illumina protocols. Briefly, mRNAs were enriched from 1.5 μg total RNA by using magnetic beads with Oligo (dT), and then fragmented by adding fragmentation buffer. The short fragments were used as templates to synthesize the first stranded cDNAs with random hexamers. Double-stranded cDNAs were then synthesized by using DNA Polymerase I and RNase H and purified with AMPure XP beads. The purified double-stranded cDNAs was then end repaired, added A tail and ligated with sequencing adapters. The products were enriched with PCR to create the final cDNA libraries. Finally, the library was sequenced on the Illumina Hiseq™ 4000 platform (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA, 2010).

RNA-Seq data analysis and identification of differentially expressed genes

Raw reads were pre-processed by removing low quality sequences and adaptor using Trimmomatic [45]. The Q30 values, GC content, and sequence duplication levels were calculated for the clean data. All downstream analysis used the clean data with high quality. The resulting high-quality clean reads were then aligned to V. dahliae sequence from genome database (http//www.broadinstitute.org/annotation/genome/Verticillium dahliae/Blast.html) using the HISAT software [46]. Following alignment, raw read counts for each V. dahliae gene were generated and normalized to FPKM (fragments per kilobase of exon model per million mapped fragments) [47]. The expression level of each gene was analyzed using the union model implemented in the HTSeq software [48]. Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were identified by using the DEGseq software with the following criteria: a fold change> 2.0 and an adjusted p value<0.05 [49]. Gene ontology (GO) term enrichment analysis of DEGs was performed based on the Wallenius non-central hyper-geometric distribution using the GOseq software [50].

qRT-PCR confirmation of differentially expressed genes

Total RNA from V. dahliae was isolated as mentioned above. One microgram of total RNA was used for first-strand cDNA synthesis with the M-MLV reverse transcriptase (TaKaRa, Dalian) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The cDNAs were then used as templates for quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) experiments. The gene specific primers used in qRT-PCR are listed in Table 1, and the V. dahliae tubulin gene was used as an internal control. The qRT-PCR assays were performed with SYBR Premix Ex Taq (TaKaRa) on a LightCycler 480 system (Roche, USA). All reactions were measured in triplicate. The relative expression ratio of each gene was calculated from the cycle threshold (CT) values using the 2-ΔΔCT method.

Table 1.

Primers used in qRT-PCR to validate RNA-seq data

| Accession no. | Gene description | Primiers |

|---|---|---|

| VDAG_10074 | tubulin | 5' TCCACCTTCGTCGGTAACTC 3' |

| 5' GCCTCCTCCTCGTACTCCTC 3' | ||

| VDAG_01193 | high-affinity nicotinic acid transporter | 5' GTGCCATCTCCGGCTTCATC 3' |

| 5' TTGCGTTGTCACCCTTCTCG 3' | ||

| VDAG_01866 | xylosidase/arabinosidase | 5' CAGCTCCGTGCTCAATGTGCC 3' |

| 5' TCCAACTGAGATGCCCGCCTT 3' | ||

| VDAG_03038 | periplasmic trehalase | 5' GGCAACAACCTCACTCGC 3' |

| 5' GCACTACGGCTACCAAACTTCT 3' | ||

| VDAG_03526 | alpha-glucuronidase | 5' GTGACGGCGGACAACTCTAC 3' |

| 5' TGCACGCCCTTGAATGTAAT 3' | ||

| VDAG_04513 | hexose transporter protein | 5' TCAACATTGCCATCCAGGTC 3' |

| 5' CGAAGCACAGCTCGAAGAAG 3' | ||

| VDAG_07563 | sugar transporter STL1 | 5' AGTGCCCGTCGTCTACTTCTT 3' |

| 5' GTTCTTGCCGTAACGCCTC 3' | ||

| VDAG_08286 | alpha-glucosides permease MPH2/3 | 5' GTATCGGCCAGACCAACCA 3' |

| 5' CATCGCCACCATTTAACCC 3' | ||

| VDAG_09088 | MFS transporter | 5' AGGAGAAGAAGGCCGTCGTG 3' |

| 5' CCGTAAAGATTGCCGTGGTC 3' |

Results

Identification of cotton resistance to V. dahliae infection

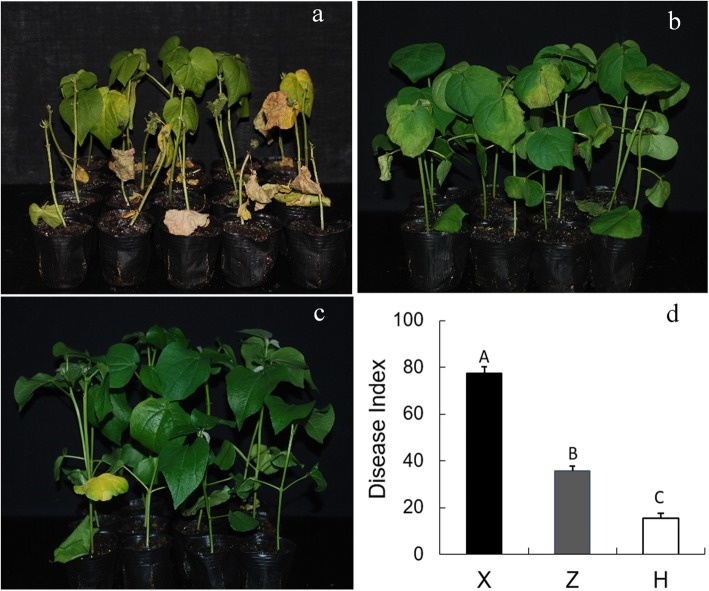

In this study, three cotton cultivars with different level of V. dahliae resistance were selected for collection of root exudates. As can be seen from the Fig. 1, severe leaf wilt disease symptoms and premature defoliation were visually apparent for Xinluzao 8, moderate but typical leaf wilt symptoms were observed in Zhongzhimian 2, whereas only weak wilt disease symptoms were observed in Hai 7124 at 20 days post inoculation. Compared with Xinluzao 8, Zhongzhimian 2 and Hai 7124 exhibited various degrees of resistance to V991 infection with significantly reduced Disease Index in inoculated seedlings (Fig. 1d). According to our results about identification of cotton resistance to V. dahliae and previous reports [43, 51], Xinluzao 8, Zhongzhimian 2 and Hai7124 were used as cultivars of susceptible, tolerant and resistant to V. dahliae, respectively.

Fig. 1.

Disease symptoms of V991 infection on Xinluzao 8, Zhongzhimian 2 and Hai 7124. The photograph was taken at 20 days post-inoculation. a. Disease symptoms of V991 infection on Xinluzao 8. b. Disease symptoms of V991 infection on Zhongzhimian 2. c. Disease symptoms of V991 infection on Hai 7124. d. Disease index of V991 on Xinluzao 8 (X), Zhongzhimian 2 (Z) and Hai 7124 (H). Different capital letters indicate significant differences (p < 0.01) using Duncan’s multiple range test

RNA-seq and transcriptome profiles of V. dahliae

To explore the transcriptomic profiling of V991 interacting with root exudates from cotton cultivars with different level of V. dahliae resistance, we generated a total of 34 RNA-seq datasets, 24 from V. dahliae treated by cotton root exudates (Vd-X-6, Vd-X-12, Vd-X-24, Vd-X-48, Vd-Z-6, Vd-Z-12, Vd-Z-24, Vd-Z-48, Vd-H-6, Vd-H-12, Vd-H-24 and Vd-H-48, each with two replicates), 8 from V. dahliae treated by water (Vd-W-6, Vd-W-12, Vd-W-24 and Vd-W-48, each with two replicates) and 2 from untreated V. dahliae, i.e. Vd-0.

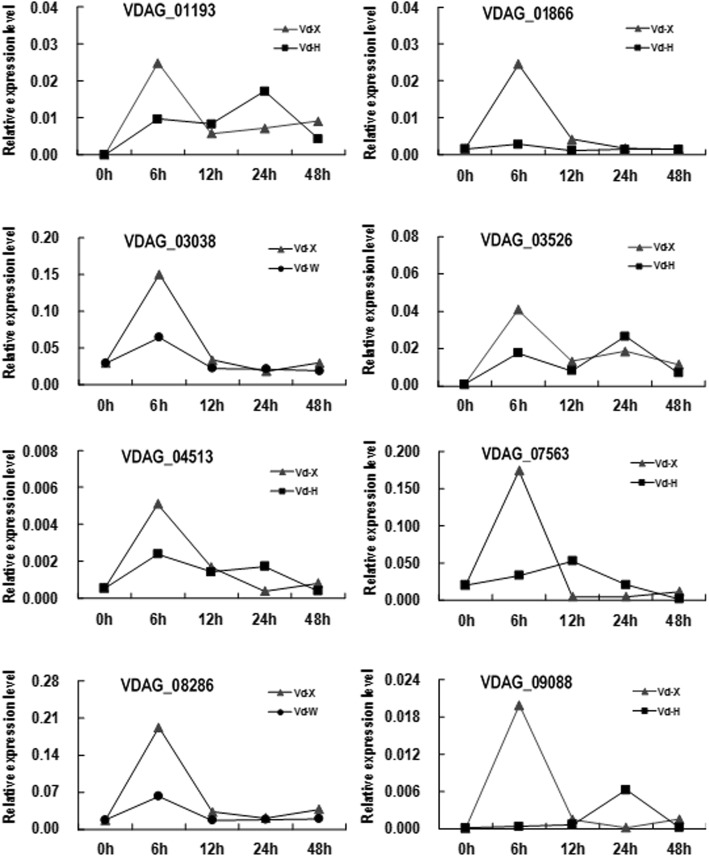

An overview of the sequencing results is outlined in Table 2. After discarding the low-quality reads, the total number of clean reads per library ranged from 13 to 22 million, and clean bases ranged from 1.97 to 3.22 Gb. Between 11,657,068 and 19,529,825 of these reads were uniquely mapped to the V. dahliae reference genome. The genic distribution of the uniquely mapped reads indicated that most reads (>88.2%) were mapped to exons, and the others were distributed between introns (0.2–0.3%) and intergenic regions (6.7–11.6%) (Additional file 3: Table S1). The Pearson’s correlation coefficients (R2) of FPKM distribution between the two biological replicates for each sample were high in each treatment (R2 = 0.945–0.987, p<0.001), indicating a good level of reproducibility of the RNA-seq data (Additional file 1: Figure S1). The RNA-seq results were also confirmed to be reliable by qRT-PCR using 8 randomly selected genes (Table 1, Fig. 2) (Additional file 2: Figure S2). For example, the expression levels of these genes peaked at 6 h in Vd-X, but showed no obvious change in Vd-H and Vd-W.

Table 2.

Summary of RNA-seq reads generated in the study

| Sample name | Raw reads | Clean reads | Clean bases | Error rate (%) | Q20 (%) | Q30 (%) | GC content (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vd-X-6a | 20,755,066 | 19,829,720 | 2.97G | 0.03 | 94.52 | 86.95 | 58.14 |

| Vd-X-6b | 20,008,568 | 19,162,740 | 2.87G | 0.03 | 95.13 | 88.19 | 58.81 |

| Vd-X-12a | 20,745,450 | 19,871,376 | 2.98G | 0.03 | 94.57 | 87.09 | 57.72 |

| Vd-X-12b | 17,752,478 | 15,961,608 | 2.39G | 0.02 | 97.07 | 91.35 | 58.61 |

| Vd-X-24a | 18,562,576 | 17,673,746 | 2.65G | 0.03 | 94.78 | 87.43 | 58.56 |

| Vd-X-24b | 18,713,224 | 17,855,894 | 2.68G | 0.03 | 94.55 | 86.95 | 58.54 |

| Vd-X-48a | 22,863,130 | 21,469,914 | 3.22G | 0.03 | 94.65 | 87.59 | 51.86 |

| Vd-X-48b | 21,450,220 | 20,335,092 | 3.05G | 0.03 | 94.82 | 87.74 | 53.99 |

| Vd-Z-6a | 19,384,506 | 18,572,808 | 2.79G | 0.03 | 94.54 | 86.96 | 58.28 |

| Vd-Z-6b | 18,947,746 | 16,766,560 | 2.51G | 0.02 | 95.94 | 89.19 | 58.19 |

| Vd-Z-12a | 19,116,156 | 16,262,760 | 2.44G | 0.02 | 96.47 | 90.18 | 58.60 |

| Vd-Z-12b | 15,846,552 | 13,820,768 | 2.07G | 0.02 | 97.05 | 90.95 | 56.33 |

| Vd-Z-24a | 22,527,850 | 19,634,838 | 2.95G | 0.02 | 97.92 | 93.16 | 58.10 |

| Vd-Z-24b | 22,678,986 | 19,618,638 | 2.94G | 0.02 | 97.87 | 93.04 | 57.99 |

| Vd-Z-48a | 18,786,644 | 18,043,658 | 2.71G | 0.02 | 94.62 | 87.75 | 51.51 |

| Vd-Z-48b | 16,083,890 | 15,364,870 | 2.3G | 0.02 | 94.84 | 88.07 | 53.31 |

| Vd-H-6a | 17,277,272 | 15,290,714 | 2.29G | 0.03 | 96.78 | 90.34 | 56.08 |

| Vd-H-6b | 23,964,812 | 21,120,448 | 3.17G | 0.02 | 97.89 | 93.15 | 58.23 |

| Vd-H-12a | 16,150,508 | 13,729,988 | 2.06G | 0.02 | 97.11 | 90.87 | 58.16 |

| Vd-H-12b | 22,302,818 | 19,253,012 | 2.89G | 0.02 | 97.81 | 92.96 | 56.86 |

| Vd-H-24a | 14,972,868 | 13,927,336 | 2.09G | 0.03 | 96.72 | 90.13 | 57.15 |

| Vd-H-24b | 14,514,160 | 13,125,772 | 1.97G | 0.03 | 96.76 | 90.26 | 56.60 |

| Vd-H-48a | 18,826,776 | 16,337,922 | 2.45G | 0.02 | 96.20 | 89.63 | 46.23 |

| Vd-H-48b | 17,007,508 | 14,591,964 | 2.19G | 0.02 | 95.70 | 89.13 | 53.93 |

| Vd-W-6a | 15,061,222 | 13,654,598 | 2.05G | 0.03 | 96.88 | 90.43 | 57.86 |

| Vd-W-6b | 22,050,470 | 21,031,720 | 3.15G | 0.02 | 96.27 | 90.86 | 56.02 |

| Vd-W-12a | 22,264,268 | 21,134,386 | 3.17G | 0.02 | 96.08 | 90.46 | 55.72 |

| Vd-W-12b | 20,529,690 | 19,622,372 | 2.94G | 0.02 | 95.78 | 89.43 | 57.29 |

| Vd-W-24a | 15,761,394 | 15,360,174 | 2.3G | 0.02 | 94.86 | 88.07 | 54.29 |

| Vd-W-24b | 23,275,930 | 22,685,328 | 3.4G | 0.02 | 95.71 | 89.64 | 58.51 |

| Vd-W-48a | 18,328,720 | 17,868,854 | 2.68G | 0.02 | 94.97 | 88.46 | 48.13 |

| Vd-W-48b | 22,437,742 | 21,421,106 | 3.21G | 0.03 | 94.41 | 87.08 | 57.12 |

| Vd-0a (CKa) | 16,237,488 | 15,825,126 | 2.37G | 0.02 | 95.37 | 88.77 | 58.51 |

| Vd-0b (CKb) | 14,193,496 | 13,833,776 | 2.08G | 0.02 | 95.30 | 88.54 | 58.72 |

Fig. 2.

The qRT-PCR analyses of the expression of 8 DEGs selected from all DEGs. The 8 DEGs included VDAG_03038 encoding periplasmic trehalase, VDAG_03526 encoding Alpha-glucuronidase, VDAG_04513 encoding hexose transporter protein, VDAG_05015 encoding beta-galactosidase, VDAG_07563 encoding sugar transporter STL1, VDAG_08212 encoding lactose permease, VDAG_08286 encoding alpha-glucosides permease MPH2/3, VDAG_09088 encoding MFS transporter. The V. dahliae tubulin gene (VDAG_10074) was used an internal control. All reactions were measured in triplicate. The expression ratio of the gene was calculated from cycle threshold (CT) values using the 2-ΔΔCT method

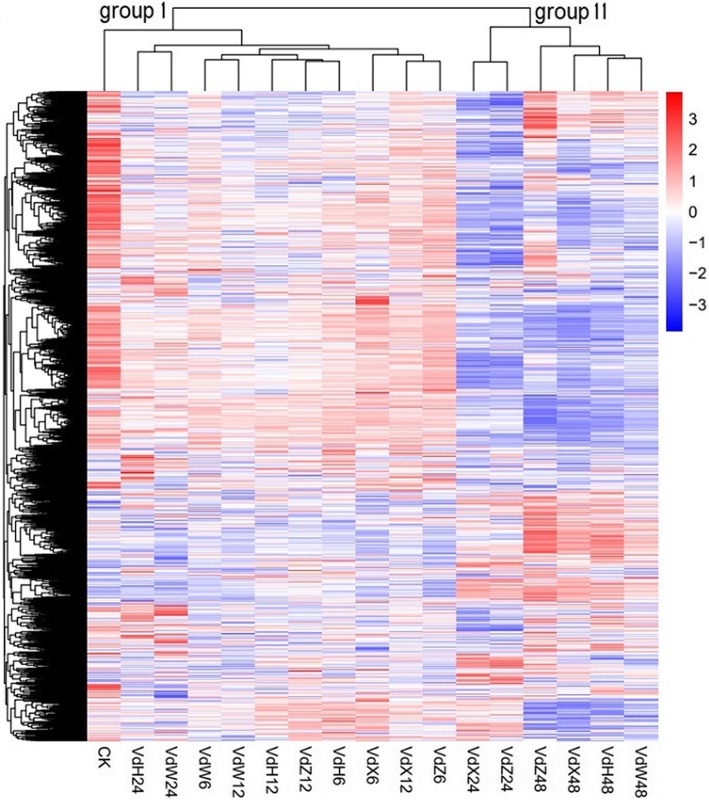

Based on hierarchical clustering using the FPKM values of all genes, it was found that the 17 samples were classified into two groups (Fig. 3). Group I contained all the Vd-6 (Vd-X-6, Vd-Z-6, Vd-H-6 and Vd-W-6) and Vd-12 (Vd-X-12, Vd-Z-12, Vd-H-12 and Vd-W-12) samples as well as Vd-H-24 and Vd-W-24. The expression profiles of these 10 samples were close to that of Vd-0 (CK), which was also clustered in group I. Group II contained all the four Vd-48 (Vd-X-48, Vd-Z-48, Vd-H-48 and Vd-W-48) samples and two Vd-24 (Vd-X-24 and Vd-Z-24) samples. The clustering tree indicated that the gene expression patterns of the two early time points (Vd-6 and Vd-12) were very similar but clearly different from that of the latest time point (Vd-48). The four Vd-24 samples were clustered into the two groups, but were distinct from other samples in the same group by forming a sub-group, suggesting that 24 h could be a transition point regarding the effect of root exudates on the growth of V. dahliae.

Fig. 3.

Hierarchical clustering of samples was performed using FPKM values of all genes identified in V. dahliae. The log10 (FPKM+ 1) values were normalized and clustered. Red and blue bands represent high and low gene expression genes, respectively. The color ranges from red to blue, indicating that log10 (FPKM + 1) is from large to small

Identification of differentially expressed genes (DEGs)

DEGs would offer insights into the metabolic and regulatory changes in V. dahliae when interacting with root exudates from cottons with different V. dahliae resistance, we thus identified DEGs (p<0.05, fold change >2.0) in each interaction using Vd-0 (CK) as a control. Regarding the treatments (root exudates or water), the largest number of DEGs was found in Vd-X vs CK (4602), followed by Vd-Z vs CK (3896), Vd-H vs CK (3227), and Vd-W vs CK (2392) (Table 3), suggesting that V. dahliae responded to all kind treatments, but responded more strongly to root exudates from the susceptible cultivar (X) than to those from the tolerant (Z) and resistant cultivars (H). Regarding the effect of treated time, the general trend for Vd-X vs CK, Vd-H vs CK and Vd-W vs CK was that the number of DEGs increased with the increased time of treatment, but for Vd-Z vs CK, there were more DEGs at 24 h than other time points. In all three treatments with root exudates, it seemed there were more up-regulated DEGs than down-regulated DEGs at 6 h, but more down-regulated DEGs than up-regulated ones at other time points (12 h, 24 h and 48 h) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Statistics of differentially expressed genes of samples vs Vd-0 (CK)

| Comparisons | Number of DEGs | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Up-regulated | Down-regulated | Total | |||

| Vd-X vs CK | Vd-X-6 h vs CK | 209 | 93 | 302 | 4602 |

| Vd-X-12 h vs CK | 199 | 102 | 301 | ||

| Vd-X-24 h vs CK | 814 | 1104 | 1918 | ||

| Vd-X-48 h vs CK | 948 | 1133 | 2081 | ||

| Vd-Z vs CK | Vd-Z-6 h vs CK | 181 | 43 | 224 | 3896 |

| Vd-Z-12 h vs CK | 193 | 279 | 472 | ||

| Vd-Z-24 h vs CK | 887 | 1128 | 2015 | ||

| Vd-Z-48 h vs CK | 820 | 1212 | 1185 | ||

| Vd-H vs CK | Vd-H-6 h vs CK | 253 | 155 | 408 | 3227 |

| Vd-H-12 h vs CK | 171 | 306 | 477 | ||

| Vd-H-24 h vs CK | 422 | 178 | 600 | ||

| Vd-H-48 h vs CK | 716 | 1026 | 1742 | ||

| Vd-W vs CK | Vd-W-6 h vs CK | 61 | 114 | 175 | 2392 |

| Vd-W-12 h vs CK | 134 | 189 | 479 | ||

| Vd-W-24 h vs CK | 301 | 178 | 626 | ||

| Vd-W-48 h vs CK | 367 | 745 | 1112 | ||

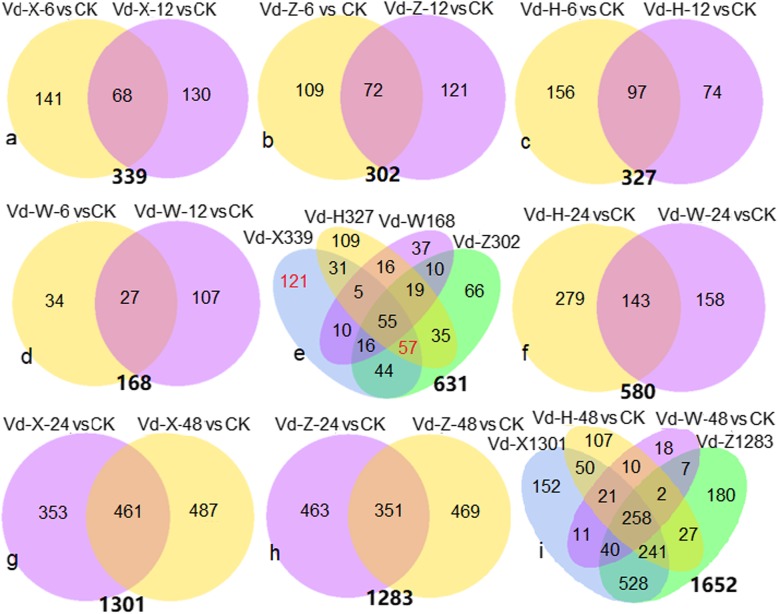

To determine the genes of V. dahliae interacted with root exudates, the up-regulated genes in Vd-X, Vd-Z, Vd-H and Vd-W samples in the group I were examined, respectively. By combining up-regulated DEGs in Vd-6 vs CK and Vd-12 vs CK, a total of 339, 302, 327 and 168 DEGs were acquired in Vd-X vs CK, Vd-Z vs CK, Vd-H vs CK and Vd-W vs CK, respectively (Fig. 4a, b, c, d). These DEGs (339, 302, 327, 168) were combined together to get 631 DEGs (Fig. 4e). Although Vd-H-24 h and Vd-W-24 h were clustered in the groupI, they were analyzed separately because the number of up-regulated genes in Vd-H-24 h (422) and Vd-W-24 h (301) were obviously greater than other samples in group I (Table 3). By combining up-regulated DEGs in Vd-H-24 h vs CK (422) and Vd-W-24 h vs CK (301), a total of 580 DEGs were obtained (Fig. 4f).

Fig. 4.

Overview of serial analysis of up-regulated DEGs identified in samples vs CK (Vd-0). a. Venn diagram of up-regulated DEGs in Vd-X-6 vs CK and Vd-X-12 vs CK. b. Venn diagram of up-regulated DEGs in Vd-Z-6 vs CK and Vd-Z-12 vs CK. c. Venn diagram of up-regulated DEGs in Vd-H-6 vs CK and Vd-H-12 vs CK. d. Venn diagram of up-regulated DEGs in Vd-W-6 vs CK and Vd-W-12 vs CK. e. Number of up-regulated DEGs identified in Vd-X vs CK (339), Vd-Z vs CK (302), Vd-H vs CK (327) and Vd-W vs CK (168). f. Venn diagram of up-regulated DEGs in Vd-H-24 vs CK and Vd-W-24 vs CK. g. Venn diagram of up-regulated DEGs in Vd-X-24 vs CK and Vd-X-48 vs CK. h. Venn diagram of up-regulated DEGs in Vd-Z-24 vs CK and Vd-Z-48 vs CK. i. Number of up-regulated DEGs identified in Vd-H-48 h (716), Vd-W-48 h vs CK (367), Vd-X vs CK (1201) and Vd-Z vs CK (1283). The Venn diagram in (a, b, c, d, e, f) represent serial analysis of up-regulated DEGs by comparing V. dahliae samples in the groupIwith CK. The Venn diagram in (g, h, i) represent serial analysis of up-regulated DEGs by comparing V. dahliae samples in the groupIIwith CK

The up-regulated genes in Vd-X, Vd-Z, Vd-H and Vd-W samples in the group II were also examined, respectively. By combining up-regulated DEGs in Vd-24 vs CK and Vd-48 vs CK, a total of 1301 and 1283 DEGs were acquired in Vd-X vs CK and Vd-Z vs CK (Fig. 4g, h), respectively. When these DEGs (1301, 1283) were combined together with DEGs in Vd-H-48 vs CK (716) and Vd-W-48 vs CK (367) comparisons, a total of 1652 DEGs were obtained (Fig. 4i).

Gene ontology analyses of DEGs

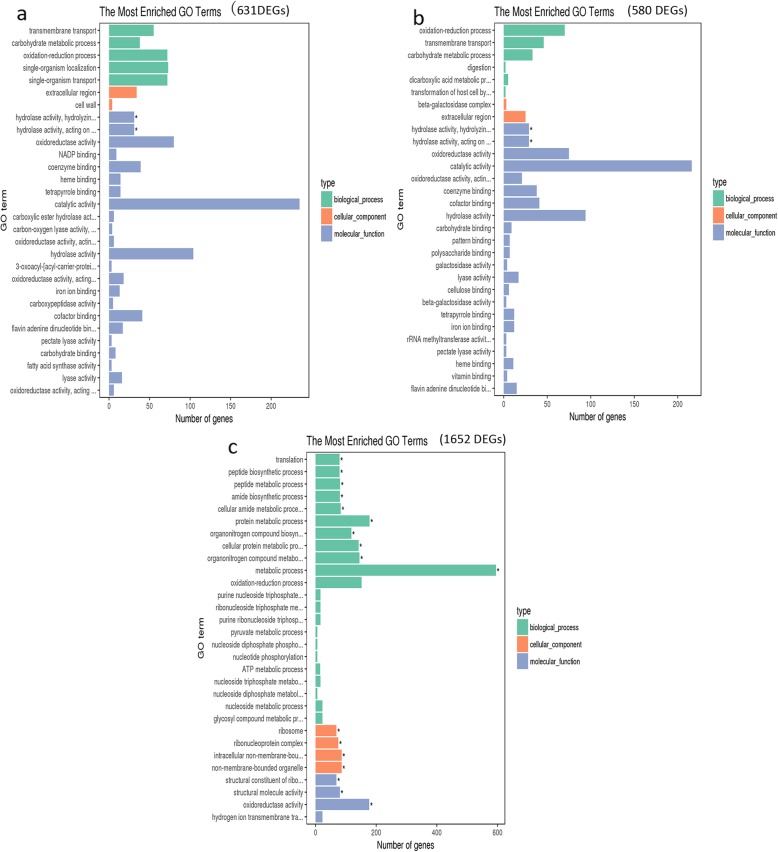

To further understand the function of these DEGs, we performed gene ontology (GO) analyses to classify the up-regulated genes in group I and group II samples, respectively. For the group I, up-regulated DEGs (631) were mainly enriched in molecular function category (Fig. 5a; Additional file 4: Table S2). ‘hydrolase activity, hydrolyzing O-glycosyl compounds’ (p = 1.22E-05), ‘hydrolase activity, acting on glycosyl bonds’ (p = 2.15E-05) and ‘oxidoreductase activity’ (p = 0.000309) were the top three significantly enriched terms in the molecular function category. ‘transmembrane transport’ (p = 3.77E-05), ‘carbohydrate metabolic process’ (p = 0.001034), ‘oxidation-reduction process’ (p = 0.001933) were the top three significantly enriched terms in the biological process category. ‘extracellular region’ (p = 0.000219) is the most significantly enriched term in the cellular component category. The enriched terms of 580 DEGs in Vd-H-24 vs CK combined with Vd-W-24 vs CK comparisons (Fig. 5b; Additional file 4: Table S2) were similar to that of 631 DEGs (Fig. 5a), suggesting that Vd-H-24 and Vd-W-24 were at the same stage of V. dahliae development as the other samples in group I. Therefore, it can be inferred that the response of V. dahliae to island cotton was more prolonged compared with upland cotton.

Fig. 5.

The most enriched GO terms of the up-regulated DEGs in V. dahliae samples vs CK. a. The most enriched GO terms of 631 up-regulated genes in samples of groupI (Vd-X, Vd-Z, Vd-H and Vd-W at 6 h and 12 h of cultured). b. The most enriched GO terms of 580 up-regulated genes in samples of groupI (Vd-H-24 h and Vd-W-24 h). c. The most enriched GO terms of 1652 up-regulated genes in samples of groupII (Vd-H-48 h, Vd-W-48 h, Vd-X and Vd-Z at 24 h and 48 h of cultured)

For DEGs (1652) that were up-regulated in the group II, the GO terms changed greatly compared with the group I (Fig. 5c; Additional file 4: Table S2). These DEGs were mainly enriched in biological process category. ‘translation’ (p = 1.67E-10), ‘peptide biosynthetic process’ (p = 4.18E-10) and ‘peptide metabolic process’ (p = 6.47E-10) were the top three significantly enriched terms in the biological process category. ‘structural constituent of ribosome’ (p = 3.70E-12) was the most significantly enriched term in molecular function category. ‘ribosome’ (p = 6.66E-12) and ‘ribonucleoprotein complex’ (p = 1.81E-06) were the significantly terms enriched in the component category.

It was notable that some genes were related to hydrolase activity, hydrolyzing O-glycosyl compounds and transmembrane transport which have been reported to be closely related to the pathogenicity of fungi, such as cell wall-degrading enzymes, sugar transporter and MFS transporter [52–55]. This GO terms were significantly enriched in samples of group I, suggesting that these samples were at the critical stage of V. dahliae-cotton interaction (6 h and 12 h). Therefore, V. dahliae samples at 6 h and 12 h were used for further analysis.

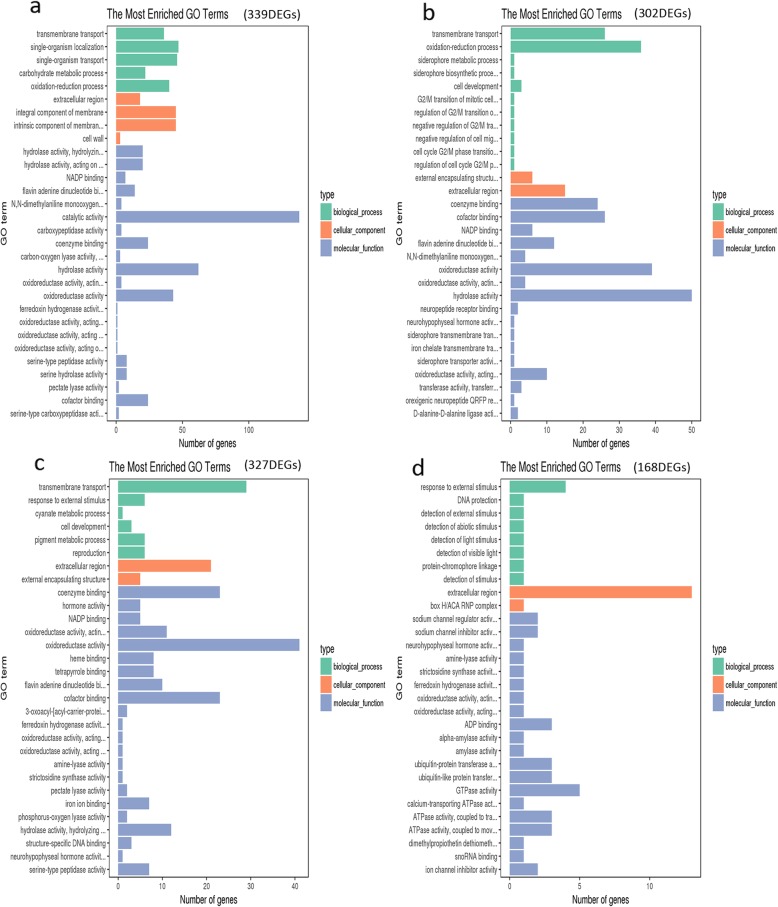

In order to find the differences of V. dahliae interacted with different root exudates, we further performed the GO analyses to classify the up-regulated genes in Vd-X vs CK (339), Vd-Z vs CK (302), Vd-H vs CK (327), Vd-W vs CK (168), respectively (Fig. 6). In addition to Vd-W vs CK (Fig. 6; Additional file 5: Table S3), it was found that ‘transmembrane transport’ was the most significantly enriched term in all the other comparisons examined (Fig. 6a, b, c). Additionally, the enriched GO terms ‘coenzyme binding’, ‘NADP binding’, ‘cofactor binding’, ‘oxidoreductase activity’, ‘flavin adenine dinucleotide binding’, ‘extracellular region’ were commonly found in Vd-X (339), Vd-Z vs CK (302) and Vd-H vs CK (327) comparisons. However, ‘hydrolase activity, hydrolyzing O-glycosyl compounds’ was the most significantly enriched term in Vd-X vs CK (339) (Fig. 6a), but was not obviously enriched in Vd-Z vs CK (302), Vd-H vs CK (327) and Vd-W vs CK (168) (Fig. 6b, c, d).

Fig. 6.

The most enriched GO terms of the up-regulated genes at 6 h and 12 h. a. The enriched GO terms of up-regulated genes in Vd-X vs CK (339). b. The enriched GO terms of up-regulated genes in Vd-Z vs CK (302). c. The enriched GO terms of up-regulated genes in Vd-H vs CK (327). d. The enriched GO terms of up-regulated genes in Vd-W vs CK (168)

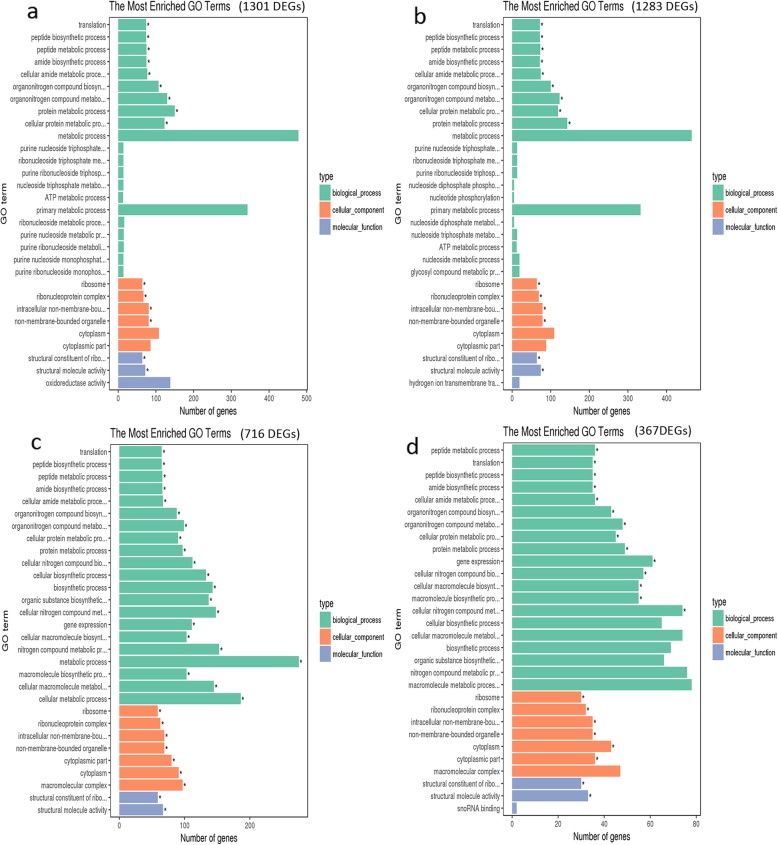

We also performed GO analyses to classify the up-regulated genes in Vd-X vs CK (1301), Vd-Z vs CK (1283), Vd-H vs CK (716), Vd-W vs CK (367), respectively (Fig. 7; Additional file 6: Table S4). As expected, the GO enriched terms of the up-regulated genes in Vd-X vs CK (1301), Vd-Z vs CK (1283), Vd-H-48 vs CK (716), Vd-W-48 vs CK (367) were very similar. It was found that ‘translation’, ‘peptide biosynthetic process’ and ‘peptide metabolic process’ were the top three significantly enriched terms in the biological process category. ‘ribosome’, ‘ribonucleoprotein complex’ and ‘intracellular non-membrane-bou’ were the top three significantly enriched term in the component category. ‘structural constituent of ribosome’ and ‘structural molecule activity’ were the significantly terms enriched in molecular function category. No ‘transmembrane transport’ and ‘hydrolase activity, hydrolyzing O-glycosyl compounds’ Go enriched terms were found in these samples of group II, again suggesting that 6 h and 12 h were the critical stage of V. dahliae-cotton interaction, while 24 h and 48 h were not.

Fig. 7.

The most enriched GO terms of the up-regulated genes in group II, respectively. a. The enriched GO terms of up-regulated genes in Vd-X vs CK (1301). b. The enriched GO terms of up-regulated genes in Vd-Z vs CK (1283). c. The enriched GO terms of up-regulated genes in Vd-H-48 vs CK (716). d. The enriched GO terms of up-regulated genes in Vd-W-48 vs CK (367)

Genes response to root exudates from different cotton cultivars in V.dahliae

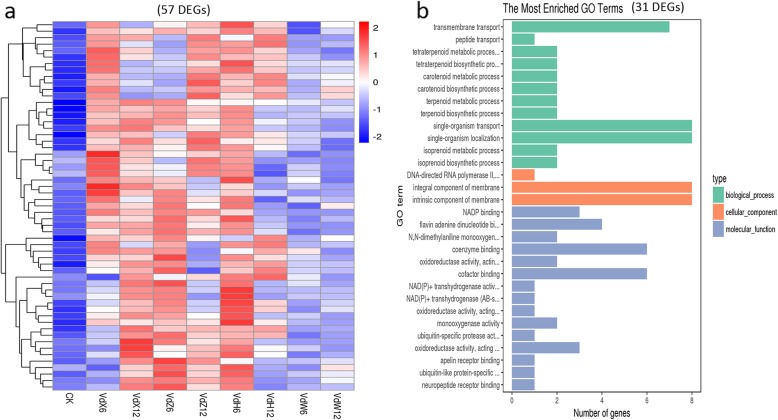

GO analyses for the up-regulated DEGs found that transmembrane transport was the most significantly enriched GO term in Vd-X vs CK (339), Vd-Z vs CK (302), Vd-H vs CK (327) comparisons, but not enriched in Vd-W vs CK (168), suggesting that genes related to this term were closely related to the initial steps of the roots infections. Several other GO enriched terms, ‘coenzyme binding’, ‘NADP binding’, ‘cofactor binding’, ‘oxidoreductase activity’, ‘flavin adenine dinucleotide binding’, ‘extracellular region’ were commonly enriched in Vd-X vs CK (339), Vd-Z vs CK (302), Vd-H vs CK (327), suggesting that genes related to these GO terms were also required for the initial steps of the roots infections. Although the main enriched GO terms were similar, the DEGs were quite different in Vd-X vs CK (339), Vd-Z vs CK (302) and Vd-H vs CK (327). Only 57 genes (Fig. 4e) were found to be commonly up-regulated in Vd-X, Vd-Z and Vd-H at the early stages of interaction. The Heatmap of 57 genes indicated that the expression level of these genes were obviously up-regulated in Vd-X, Vd-Z, and Vd-H at one or two time points of cultured, but not obviously up-regulated in Vd-W (Fig. 8a). These genes were considered as potential candidates for involvement in the initial steps of the roots infections. The 57 genes included 31 genes with known functions (Table 4), and 26 genes with unknown functions. Of 31 genes with known functions, it is notable that 7 genes were related to transmembrane transport (Fig. 8b; Additional file 7: Table S5), including 4 sugar transporter genes (VDAG_09835, VDAG_02051, VDAG_03649, VDAG_09983), 1 pantothenate transporter liz1 gene (VDAG_02269), 1 DUF895 domain membrane protein gene (VDAG_07864) and 1 Inner membrane transport protein yfaV gene (VDAG_00832) (Table 4). Few genes have been reported to be related to pathogenicity of V. dahliae, such as a gene encoding cyclopentanone 1,2-monooxygenase [18], two genes encoding thiamine transporter protein [56, 57]. Functional analysis for these candidate genes may be useful for the study of the molecular basis of V. dahliae interacted with cotton.

Fig. 8.

Heatmap and GO analyses of up-regulated genes in Vd-X, Vd-Z and Vd-H, respectively. a. Heatmap of 57 genes found to be up-regulated in Vd-X, Vd-Z and Vd-H at one or two time points of cultured (6 h and 12 h). The log-transformed expression values range from − 2 to 2. Red and blue bands represent high and low gene expression levels, respectively. b. The most enriched GO terms of the 31 DEGs with known functions

Table 4.

Up-regulated genes with known functions in Vd-X, Vd-Z and Vd-H at early stages of interaction

| Code | Gene ID | Enzyme name | FPKM value | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CK | VdX6 | VdX12 | VdZ6 | VdZ12 | VdH6 | VdH12 | VdW6 | VdW12 | |||

| 1 | VDAG_02051 | High-affinity glucose transporter ght2 | 29.4802 | 22.04664 | 84.23955 | 47.6086 | 60.97154 | 93.52616 | 103.058 | 46.62293 | 30.56167 |

| 2 | VDAG_03649 | Sugar transporter | 0.338716 | 1.026522 | 0.972863 | 0.571231 | 1.115773 | 0.729055 | 1.128715 | 0.509536 | 0.50572 |

| 3 | VDAG_09835 | Hexose transporter | 1.465257 | 3.968813 | 3.936814 | 4.569835 | 3.108347 | 4.246236 | 2.397604 | 1.989069 | 1.935044 |

| 4 | VDAG_09983 | Sugar transporter | 0.826351 | 1.330852 | 1.620789 | 1.96333 | 0.809208 | 1.517935 | 1.816533 | 1.172747 | 1.108737 |

| 5 | VDAG_00832 | Inner membrane transport protein yfaV | 1.328122 | 2.69694 | 3.987047 | 4.988756 | 2.544548 | 6.30185 | 3.71284 | 2.102835 | 2.608609 |

| 6 | VDAG_00833 | Thiol-specific monooxygenase | 2.812437 | 3.372149 | 6.229075 | 6.864658 | 4.642015 | 6.132306 | 2.821518 | 3.31251 | 3.406964 |

| 7 | VDAG_02269 | Pantothenate transporter liz1 | 0.574735 | 10.51644 | 3.593005 | 0.612767 | 8.552547 | 5.701658 | 0.157546 | 0.281539 | 0.041829 |

| 8 | VDAG_07864 | DUF895 domain membrane protein | 0 | 0.358107 | 0.365747 | 0.645067 | 0.105314 | 0.505642 | 0.342338 | 0.213305 | 0.133121 |

| 9 | VDAG_01073 | NAD (P) H-dependent D-xylose reductase | 15.75744 | 20.66968 | 30.75152 | 33.81787 | 26.80472 | 28.37045 | 28.33363 | 16.91421 | 18.73819 |

| 10 | VDAG_01137 | Thiamine thiazole synthase | 614.5958 | 1120.375 | 879.3086 | 769.972 | 1351.333 | 1043.097 | 1213.615 | 780.4955 | 914.2021 |

| 11 | VDAG_01672 | Conidial development protein fluffy | 12.03245 | 22.95618 | 16.67069 | 14.22671 | 23.65364 | 22.70368 | 24.9867 | 13.75736 | 15.00116 |

| 12 | VDAG_02162 | Oviduct-specific glycoprotein | 0.227984 | 0.693403 | 0.423062 | 0.620165 | 0.335718 | 0.664225 | 0.702286 | 0.371898 | 0.391474 |

| 13 | VDAG_02175 | Beta-glucosidase | 0 | 0.230686 | 0.231927 | 0.374579 | 0.232406 | 0.403597 | 0.098718 | 0.036308 | 0.102984 |

| 14 | VDAG_02633 | Beta-lactamase family protein | 3.050937 | 6.146087 | 5.612143 | 6.318416 | 5.777795 | 7.129429 | 6.223959 | 3.304537 | 4.690835 |

| 15 | VDAG_02843 | Fibronectin | 2.255216 | 3.641777 | 4.31623 | 4.346089 | 2.988267 | 4.024384 | 4.227908 | 3.217397 | 3.142531 |

| 16 | VDAG_02844 | Ubiquitin carboxyl-terminal hydrolase | 1.953236 | 4.647556 | 3.491474 | 2.867615 | 4.295582 | 3.838786 | 3.769097 | 2.859783 | 2.493258 |

| 17 | VDAG_03942 | Beta-lactamase family protein | 3.714124 | 111.1741 | 18.61932 | 8.608223 | 65.63955 | 58.8475 | 0.267788 | 5.385614 | 1.313926 |

| 18 | VDAG_03943 | Cyclopentanone 1,2-monooxygenase | 3.091277 | 213.913 | 27.61544 | 13.96051 | 120.0825 | 92.52951 | 0.866178 | 8.16749 | 2.187358 |

| 19 | VDAG_04707 | Helicase SWR1 | 81.01633 | 152.1582 | 107.6387 | 110.2411 | 147.0122 | 139.7217 | 137.8717 | 105.301 | 132.1303 |

| 20 | VDAG_05314 | N-(5-amino-5-carboxypentanoyl)-L-cysteinyl-D-valine synthase | 9.774005 | 25.65614 | 14.10339 | 15.6124 | 19.11988 | 27.47597 | 19.27068 | 15.58876 | 16.02938 |

| 21 | VDAG_05458 | Acetylxylan esterase | 0.553047 | 2.897187 | 2.187976 | 2.776539 | 2.587627 | 1.928449 | 0.968931 | 0.862581 | 0.885039 |

| 22 | VDAG_06953 | Kinesin light chain | 0.425595 | 1.336314 | 0.641706 | 0.95834 | 1.168227 | 1.627748 | 1.075756 | 0.38034 | 0.897279 |

| 23 | VDAG_08600 | Thiopurine S-methyltransferase family protein | 28.38327 | 41.42097 | 71.57507 | 56.80394 | 59.66433 | 60.43575 | 62.81802 | 37.98759 | 38.88032 |

| 24 | VDAG_08689 | Retinol dehydrogenase | 1.932819 | 2.608155 | 6.598116 | 8.790265 | 6.5672 | 4.225019 | 3.010194 | 3.177277 | 3.647746 |

| 25 | VDAG_08954 | Carboxylic ester hydrolase | 0.956565 | 3.376228 | 5.336164 | 4.806672 | 3.062654 | 6.82588 | 2.173958 | 2.390473 | 1.772136 |

| 27 | VDAG_08979 | URE2 protein | 4.080627 | 6.68038 | 7.958957 | 8.914888 | 7.624858 | 8.220244 | 5.710169 | 4.310528 | 4.728051 |

| 26 | VDAG_09114 | Galactose oxidase | 0.076631 | 0.245438 | 0.555276 | 0.588735 | 0.221988 | 0.772877 | 0.178927 | 0.184511 | 0.193227 |

| 28 | VDAG_09269 | NAD (P) transhydrogenase | 1.434656 | 5.410515 | 2.93751 | 2.364836 | 2.830261 | 3.377882 | 1.639596 | 1.075059 | 1.322266 |

| 29 | VDAG_09707 | Amidase | 0.340497 | 0.597686 | 1.138296 | 0.675114 | 0.853334 | 1.090583 | 0.668288 | 0.390384 | 0.487727 |

| 30 | VDAG_10195 | Vacuolar protein sorting-associated protein | 10.90674 | 26.16851 | 16.17757 | 16.16115 | 23.07354 | 25.98232 | 21.03424 | 16.03954 | 16.69196 |

| 31 | VDAG_10402 | Isoamyl alcohol oxidase | 1.289472 | 3.463787 | 3.225775 | 3.469081 | 3.14358 | 3.691591 | 2.373917 | 2.260947 | 2.547368 |

Genes response to root exudates from susceptible cotton cultivar in V. dahliae

GO analyses for the up-regulated DEGs found that ‘hydrolase activity, hydrolyzing O-glycosyl compounds’ was the most significantly enriched term in molecular function category in Vd-X (339) (p = 8.78E-05) (Fig. 6a), but not in Vd-Z (302), Vd-H (327), Vd-W (168) (Fig. 6b, c, d) suggesting that genes related to this term would be contribute to the pathogenesis of V. dahliae. A total of 20 genes related to this term were found in Vd-X (339), including 16 genes (1–16) reported to be related to cell wall degradation (Table 5) [58].

Table 5.

List of 20 genes in ‘hydrolase activity, hydrolyzing O-glycosyl compounds’ term

| Code | Gene ID | Enzyme name | FPKM value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CK | VdX6 | VdX12 | VdX24 | VdX48 | |||

| 1 | VDAG_01555 | Alpha-glucosidase | 0.525139 | 1.351249 | 0.631004 | 0.348396 | 0.365856 |

| 2 | VDAG_01781 | Polygalacturonase | 4.42107 | 9.593065 | 6.264324 | 4.446467 | 3.902134 |

| 3 | VDAG_01866 | Xylosidase/arabinosidase | 2.999633 | 6.737425 | 3.158829 | 1.499116 | 1.280038 |

| 4 | VDAG_02175 | Beta-glucosidase | 0 | 0.230686 | 0.231927 | 0.113611 | 0.277088 |

| 5 | VDAG_02469 | Glucan 1,3-beta-glucosidase | 9.092852 | 19.9074 | 14.55665 | 10.28952 | 7.637805 |

| 6 | VDAG_02542 | Beta-glucosidase | 1.740641 | 3.559025 | 2.760439 | 1.618581 | 1.613549 |

| 7 | VDAG_03038 | Trehalase | 4.037018 | 10.34559 | 4.171279 | 3.42203 | 2.780894 |

| 8 | VDAG_03553 | Alpha-N-arabinofuranosidase | 2.017713 | 2.840681 | 4.043869 | 1.883232 | 2.186114 |

| 9 | VDAG_03526 | Alpha-glucuronidase | 3.077552 | 7.649031 | 3.025971 | 2.462925 | 2.180948 |

| 10 | VDAG_03790 | Endo-1,4-beta-xylanase | 0.988496 | 3.303921 | 1.049834 | 1.031276 | 1.380458 |

| 11 | VDAG_05708 | Endoglucanase II | 0.335166 | 0.833922 | 1.422978 | 0.420705 | 1.30643 |

| 12 | VDAG_06072 | alpha-1,2-Mannosidase | 9.973456 | 12.06809 | 20.52097 | 6.852838 | 6.954053 |

| 13 | VDAG_06165 | Endo-1,4-beta-xylanase | 0.808652 | 1.606539 | 1.930602 | 1.34546 | 0.837317 |

| 14 | VDAG_07983 | Mixed-linked glucanase | 2.264495 | 5.11995 | 2.258442 | 0.964882 | 0.623151 |

| 15 | VDAG_09516 | Glucanase | 0.565726 | 1.419057 | 0.616539 | 0.988646 | 0.415697 |

| 16 | VDAG_09739 | Galactan 1,3-beta-galactosidase | 0 | 0.361516 | 0.129547 | 0.044338 | 0.086698 |

| 17 | VDAG_02162 | Oviduct-specific glycoprotein | 0.227984 | 0.693403 | 0.423062 | 0.287278 | 0.208611 |

| 18 | VDAG_05270 | Ankyrin repeat and protein kinase domain-containing protein | 0.050289 | 0.467369 | 0.237746 | 0.317916 | 0.584707 |

| 19 | VDAG_07990 | Secreted protein | 0.318378 | 0.605114 | 1.132354 | 0.273572 | 0.134914 |

| 20 | VDAG_08742 | RTA1 protein | 1.754573 | 3.368212 | 2.766573 | 3.690469 | 2.091908 |

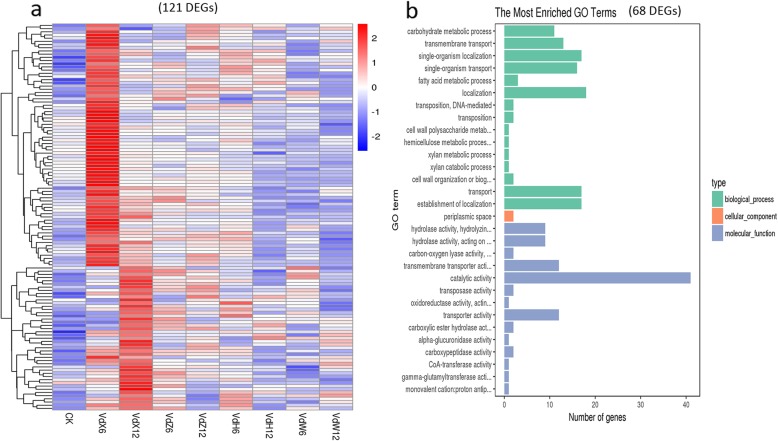

A total of 121 DEGs unique to Vd-X (Fig. 4e) whose expression were up-regulated only in root exudates from susceptible cotton cultivar (X) were thought to be the candidate genes related to pathogenesis of V. dahliae. The Heatmap of 121 genes indicated that the expression level of these genes were obviously up-regulated in Vd-X, and only few genes were also up-regulated in Vd-Z, Vd-H, and Vd-W at one or two time points of cultured (Fig. 9a). The 121 DEGs included 68 genes with known functions (Table 6), 57 genes with unknown functions. Of 68 DEGs with known functions, it is notable that 9 genes related to hydrolase activity, hydrolyzing O-glycosyl compounds (Fig. 9b; Additional file 8: Table S6) encode cell wall-degrading proteins, including endo-1,4-beta-xylanase (VDAG_03790, VDAG_06165), xylosidase/arabinosidase (VDAG_01866), mixed-linked glucanase (VDAG_07983), glucanase (VDAG_09516), trehalase (VDAG_03038), Alpha-glucosidase (VDAG_01555), Alpha-glucuronidase (VDAG_03526), Alpha-N-arabinofuranosidase (VDAG_03553), 13 genes were related to transmembrane transport, including 6 sugar transporter genes (VDAG_07141, VDAG_04513, VDAG_08286, VDAG_09121, VDAG_07563, VDAG_03714), 3 vitamin transporter genes (VDAG_01193, VDAG_09734, VDAG_08086), 2 oligopeptide transporter (VDAG_06060, VDAG_05125), 1 MFS transporter gene (VDAG_09088), 1 quinate permease gene (VDAG_02089). Functional analysis for these candidate genes may be useful for the study of the pathogenicity molecular basis of V. dahliae.

Fig. 9.

Heatmap and GO analyses of up-regulated genes only in Vd-X at 6 h or 12 h. a. Heatmap of 121 genes found to be up-regulated only in Vd-X at 6 h or 12 h of cultured. The log-transformed expression values range from − 2 to 2. Red and blue bands represent high and low gene expression levels, respectively. b. The most enriched GO terms of the 68 DEGs with known functions

Table 6.

Up-regulated Genes with known functions only in Vd-X at early stages of interaction

| Code | Gene ID | Enzyme name | FPKM value | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CK | VdX6 | VdX12 | VdZ6 | VdZ12 | VdH6 | VdH12 | VdW6 | VdW12 | |||

| 1 | VDAG_01555 | Alpha-glucosidase | 0.525139 | 1.351249 | 0.631004 | 0.605564 | 0.620046 | 0.590879 | 0.45985 | 0.402997 | 0.450216 |

| 2 | VDAG_01866 | Xylosidase/arabinosidase | 2.999633 | 6.737425 | 3.158829 | 3.239391 | 2.54392 | 3.426193 | 2.85372 | 2.522221 | 2.049945 |

| 3 | VDAG_03038 | Trehalase | 4.037018 | 10.34559 | 4.171279 | 3.328726 | 3.723864 | 3.169099 | 3.525587 | 2.688863 | 2.205004 |

| 4 | VDAG_03553 | Alpha-N-arabinofuranosidase | 2.017713 | 2.840681 | 4.043869 | 3.204145 | 2.274602 | 3.487533 | 2.467085 | 2.319605 | 1.751206 |

| 5 | VDAG_03526 | Alpha-glucuronidase | 3.077552 | 7.649031 | 3.025971 | 2.906985 | 3.357615 | 3.521792 | 2.073764 | 2.32711 | 2.3016 |

| 6 | VDAG_03790 | Endo-1,4-beta-xylanase | 0.988496 | 3.303921 | 1.049834 | 0.937063 | 0.564055 | 0.872658 | 0.73547 | 0.559991 | 0.670659 |

| 7 | VDAG_06165 | Endo-1,4-beta-xylanase | 0.808652 | 1.606539 | 1.930602 | 1.213314 | 1.249954 | 1.229588 | 1.647082 | 0.870066 | 1.601574 |

| 8 | VDAG_07983 | Mixed-linked glucanase | 2.264495 | 5.11995 | 2.258442 | 2.232694 | 2.349181 | 1.691225 | 0.893242 | 1.840287 | 1.631545 |

| 9 | VDAG_09516 | Glucanase | 0.565726 | 1.419057 | 0.616539 | 0.766083 | 1.168563 | 0.644183 | 0.590824 | 0.426934 | 0.643502 |

| 10 | VDAG_01193 | High-affinity nicotinic acid transporter | 0.922962 | 4.474884 | 2.389495 | 1.367505 | 2.293024 | 1.158877 | 1.052356 | 1.003427 | 0.855293 |

| 11 | VDAG_02089 | Quinate permease | 0.246652 | 1.239759 | 0.27095 | 0.039896 | 0.305545 | 0.133467 | 0.052949 | 0.090075 | 0 |

| 12 | VDAG_02826 | Voltage-gated potassium channel subunit beta-1 | 0.52636 | 1.770148 | 1.55752 | 0.539201 | 0.500666 | 0.471194 | 0.446343 | 0.28894 | 0.387249 |

| 13 | VDAG_03714 | Sugar transporter | 0 | 0.329793 | 0.192273 | 0.038948 | 0.105726 | 0.067001 | 0.051691 | 0.087935 | 0.148554 |

| 14 | VDAG_04513 | Hexose transporter protein | 2.194243 | 6.031784 | 2.31866 | 2.734094 | 2.48747 | 2.407533 | 1.509354 | 1.42593 | 1.515528 |

| 15 | VDAG_05125 | Oligopeptide transporter 1 | 0.10654 | 0.48534 | 0.340637 | 0.244306 | 0.11979 | 0.146367 | 0.035656 | 0.11036 | 0.100641 |

| 16 | VDAG_06060 | Oligopeptide transporter 2 | 1.273316 | 3.507472 | 1.424591 | 1.091823 | 1.400967 | 1.407274 | 0.863739 | 0.954953 | 0.987525 |

| 17 | VDAG_07141 | H+/hexose cotransporter 1 | 1.174547 | 3.193565 | 2.110352 | 1.578545 | 2.020917 | 2.37435 | 1.543719 | 1.33677 | 1.028067 |

| 18 | VDAG_07563 | Sugar transporter STL1 | 3.617449 | 23.46294 | 4.627167 | 4.448156 | 3.630124 | 4.030519 | 3.522212 | 2.785485 | 1.485532 |

| 19 | VDAG_08086 | Vitamin H transporter 1 | 1.611487 | 2.873923 | 3.84332 | 1.865509 | 3.010686 | 2.468418 | 1.583815 | 1.710399 | 2.150159 |

| 20 | VDAG_09088 | MFS transporter | 0.338652 | 3.60446 | 0.393707 | 0.739129 | 0.402541 | 0.835313 | 0.099841 | 1.023219 | 0.125486 |

| 21 | VDAG_09121 | Maltose permease MAL31 | 2.060967 | 3.647271 | 3.112186 | 2.227495 | 2.585063 | 3.214763 | 2.716028 | 2.03735 | 2.722908 |

| 22 | VDAG_09734 | Major myo-inositol transporter iolT | 8.604817 | 27.04882 | 11.02109 | 8.86173 | 9.040651 | 10.25533 | 5.441678 | 7.247084 | 5.418201 |

| 23 | VDAG_00798 | Calphotin | 2.4298 | 4.795505 | 3.519256 | 3.892562 | 3.226339 | 4.260004 | 3.460753 | 2.902065 | 2.982781 |

| 24 | VDAG_01176 | 4-coumarate-CoA ligase | 0.286 | 1.403583 | 0.44009 | 0.381114 | 0.556027 | 0.320558 | 0.53875 | 0.105766 | 0.323503 |

| 25 | VDAG_01341 | Methylitaconate delta2-delta3-isomerase | 0.899946 | 1.132172 | 2.138507 | 1.664966 | 1.364732 | 2.236922 | 1.509204 | 1.611162 | 1.286028 |

| 26 | VDAG_01782 | Pectinesterase family protein | 4.733987 | 9.575896 | 5.053127 | 6.412238 | 6.100081 | 6.127981 | 5.954252 | 4.959662 | 6.786958 |

| 27 | VDAG_01783 | Modification methylase Sau96I | 0.081859 | 0.188908 | 0.307139 | 0.230715 | 0.074369 | 0.265676 | 0.115725 | 0.059275 | 0.191795 |

| 28 | VDAG_01869 | Taurine catabolism dioxygenase TauD | 10.85428 | 19.91771 | 15.68955 | 17.54684 | 14.0093 | 16.81377 | 17.27372 | 13.04782 | 16.37882 |

| 29 | VDAG_01837 | Metallo-beta-lactamase superfamily protein | 0.716978 | 2.102556 | 2.371603 | 1.81465 | 1.748865 | 1.727576 | 0.957063 | 1.388916 | 1.043824 |

| 30 | VDAG_03354 | Pectate lyase | 0.259957 | 0.618515 | 1.255778 | 0.930004 | 0.591007 | 0.526287 | 0.19059 | 0.121278 | 0.308629 |

| 31 | VDAG_03792 | Beta-fructofuranosidase | 1.417489 | 5.825462 | 1.214082 | 1.161383 | 1.005343 | 1.333573 | 0.668952 | 0.822075 | 0.921293 |

| 32 | VDAG_03800 | Phosphate transporter | 1.066441 | 0.959226 | 2.010011 | 1.410633 | 1.683093 | 1.10869 | 1.149276 | 1.183568 | 0.876848 |

| 33 | VDAG_03894 | Lipase | 0.079272 | 0.063231 | 0.623916 | 0.415827 | 0.091218 | 0.167024 | 0.219462 | 0.179133 | 0.25405 |

| 34 | VDAG_03891 | Acetamidase | 2.501319 | 6.074764 | 4.124551 | 3.080263 | 3.894677 | 2.879871 | 1.776109 | 1.402326 | 2.302258 |

| 35 | VDAG_03941 | Regulatory protein alcR | 0.474947 | 2.525426 | 0.864933 | 1.051024 | 0.812903 | 0.673834 | 0.263023 | 0.168962 | 0.879413 |

| 36 | VDAG_03970 | 4-trimethylaminobutyraldehyde dehydrogenase | 1.11673 | 4.961036 | 1.515747 | 1.065759 | 1.558865 | 0.886226 | 0.667051 | 0.311335 | 0.77097 |

| 37 | VDAG_04175 | SAM and PH domain-containing protein | 2.508312 | 4.896892 | 2.096234 | 2.206801 | 2.672685 | 2.29161 | 2.247836 | 2.221988 | 1.767456 |

| 38 | VDAG_04685 | AdhA | 0 | 0.749311 | 0.363623 | 0.132737 | 0.418209 | 0.139558 | 0 | 0.184184 | 0 |

| 39 | VDAG_04961 | Aldehyde dehydrogenase | 0.304878 | 0.985035 | 0.491127 | 0.246694 | 0.251239 | 0.381107 | 0.500614 | 0.036883 | 0.037001 |

| 40 | VDAG_05050 | Choline monooxygenase | 1.342722 | 1.170244 | 3.332128 | 1.062762 | 0.474455 | 0.697089 | 0.450456 | 0.508567 | 0.251975 |

| 41 | VDAG_05135 | Carboxypeptidase S1 | 0 | 0.199664 | 0.217901 | 0.076268 | 0.038868 | 0.179948 | 0 | 0.046469 | 0.064716 |

| 42 | VDAG_05297 | 3-alpha-(Or 20-beta)-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase | 0.502718 | 0.859157 | 1.524476 | 1.118018 | 1.276975 | 0.544056 | 0.668099 | 1.077308 | 0.380073 |

| 43 | VDAG_05324 | 3-alpha-(Or 20-beta)-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase | 0.424632 | 2.728921 | 0.853371 | 0.702873 | 0.806426 | 0.900467 | 0.35943 | 0.584218 | 0.73203 |

| 44 | VDAG_05455 | Gamma-glutamyltranspeptidase | 8.097854 | 14.62289 | 7.23067 | 6.837455 | 10.22524 | 8.804363 | 7.083837 | 7.027691 | 7.604183 |

| 45 | VDAG_05780 | Long-chain-alcohol oxidase | 12.20917 | 23.38509 | 13.18572 | 13.34187 | 11.49875 | 13.68543 | 9.477272 | 10.87106 | 12.46451 |

| 46 | VDAG_06126 | Secreted protein | 0.396382 | 2.540219 | 0.349184 | 0.221178 | 0.522292 | 0.419048 | 0.331605 | 0.146586 | 0.504571 |

| 47 | VDAG_06334 | Sodium/bile acid cotransporter 7-A | 5.975553 | 10.44867 | 6.986222 | 7.134331 | 6.986681 | 5.925724 | 5.77749 | 6.149932 | 6.790046 |

| 48 | VDAG_06756 | Aldo-keto reductase yakc | 0 | 0.064868 | 0.430866 | 0.068946 | 0 | 0.085674 | 0.06682 | 0 | 0 |

| 49 | VDAG_06997 | Epoxide hydrolase | 0 | 0.343647 | 0.057084 | 0.180036 | 0.229805 | 0.229429 | 0.137809 | 0 | 0 |

| 50 | VDAG_07057 | Acetyl-coenzyme A synthetase | 23.07698 | 71.91837 | 28.53978 | 25.50788 | 23.87777 | 25.41201 | 15.28279 | 11.00477 | 13.18577 |

| 51 | VDAG_07158 | ECM14 protein | 1.312533 | 1.658648 | 2.765504 | 2.456603 | 2.03252 | 1.488009 | 0.944383 | 1.82507 | 1.283626 |

| 52 | VDAG_07166 | Carnitine O-palmitoyltransferase I | 17.12393 | 31.32699 | 17.35379 | 13.93265 | 19.8167 | 20.48912 | 14.99808 | 12.56235 | 12.11036 |

| 53 | VDAG_07544 | Non-specific lipid-transfer protein | 7.073779 | 14.02016 | 9.853166 | 11.52067 | 6.789217 | 7.23411 | 6.939248 | 6.207376 | 5.102574 |

| 54 | VDAG_07681 | ATP-binding cassette sub-family G member 5 | 0.280493 | 3.096587 | 0.36107 | 0.502172 | 0.490947 | 0.426678 | 0.394345 | 0.556072 | 0.142852 |

| 55 | VDAG_07728 | Adenine deaminase | 0.871341 | 0.730222 | 1.862647 | 1.335189 | 0.613871 | 0.842805 | 0.83656 | 1.780561 | 0.44741 |

| 56 | VDAG_07980 | Peptide hydrolase | 4.547497 | 11.54846 | 6.580591 | 4.869931 | 5.140242 | 5.641155 | 3.053364 | 4.299607 | 2.724793 |

| 57 | VDAG_08067 | Pectate lyase B | 1.597656 | 3.549548 | 2.364415 | 2.864407 | 2.737817 | 2.960574 | 1.770214 | 2.357985 | 1.326954 |

| 58 | VDAG_08286 | Alpha-glucosides permease MPH2/3 | 3.761419 | 10.00247 | 2.846449 | 3.855032 | 2.85363 | 4.066861 | 2.265101 | 2.82029 | 0.99225 |

| 59 | VDAG_08654 | Acetyl-coenzyme A synthetase | 6.311482 | 25.47375 | 11.4497 | 7.045619 | 9.681632 | 9.402415 | 4.885708 | 5.435872 | 4.019251 |

| 60 | VDAG_08703 | Alpha-1,2 mannosyltransferase KTR1 | 0.115893 | 0.332317 | 0.996546 | 0.726013 | 0.607646 | 0.444118 | 0.773915 | 0.233683 | 0.497122 |

| 61 | VDAG_09082 | Succinyl-CoA:3-ketoacid-coenzyme A transferase | 4.461569 | 15.45278 | 8.700468 | 11.87125 | 6.812786 | 6.795712 | 2.9958 | 3.117604 | 3.772685 |

| 62 | VDAG_09253 | Sulfate transporter | 0.621583 | 1.003273 | 1.925273 | 0.996173 | 0.614154 | 0.592044 | 0.590546 | 0.211895 | 0.651484 |

| 63 | VDAG_09313 | Alpha-ketoglutarate-dependent sulfonate dioxygenase | 1.120543 | 1.596103 | 2.703301 | 1.520719 | 1.336662 | 2.082727 | 1.975342 | 1.398853 | 2.107069 |

| 64 | VDAG_09583 | Alcohol oxidase | 0.0371 | 0.946964 | 0.029918 | 0.166105 | 0.170765 | 0.201409 | 0.030483 | 0.029096 | 0 |

| 65 | VDAG_09712 | Succinate/fumarate mitochondrial transporter | 14.67152 | 66.4187 | 23.3401 | 11.31978 | 19.52469 | 18.52314 | 4.75121 | 5.791921 | 6.018953 |

| 66 | VDAG_09813 | C6 transcription factor RegA | 0.355193 | 1.301947 | 0.457038 | 0.47428 | 0.543437 | 0.50541 | 0.322972 | 0.266267 | 0.23939 |

| 67 | VDAG_10171 | Fungal specific transcription factor domain-containing protein | 1.890601 | 3.353588 | 3.570153 | 2.624426 | 2.242321 | 2.5453 | 1.963163 | 2.84132 | 2.766448 |

| 68 | VDAG_10443 | Rhamnogalacturonan lyase | 2.396504 | 4.665757 | 2.848467 | 2.509498 | 2.189874 | 2.620633 | 1.958417 | 2.44632 | 1.750408 |

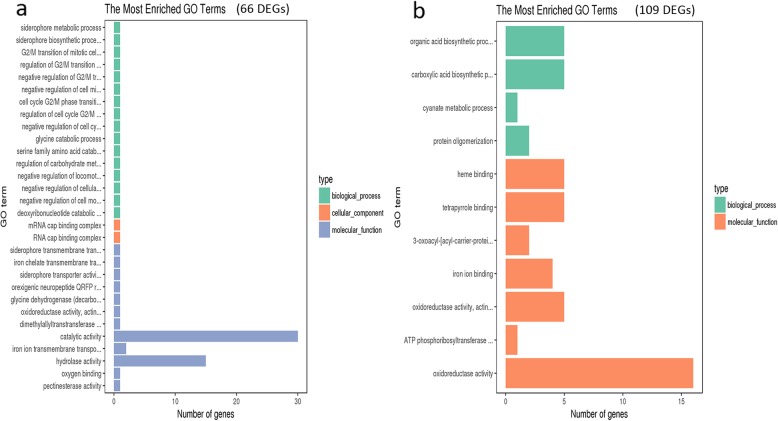

Additionally, GO analysis of 66 DEGs unique to Vd-Z (Fig. 10a) and 109 DEGs unique to Vd-H (Fig. 10b; Additional file 9: Table S7) did not find hydrolase activity, hydrolyzing O-glycosyl compounds and transmembrane transport enriched GO terms, suggesting that the number of DEGs related to hydrolase activity hydrolyzing O-glycosyl compounds and transmembrane transport in Vd-X vs CK (339) were higher than that in Vd-H vs CK (327) and Vd-Z vs CK (302) and these genes may be related to pathogenesis of V. dahliae.

Fig. 10.

GO analyses of DEGs unique to Vd-Z vs CK and Vd-H vs CK. a. GO analysis of 66 DEGs unique to Vd-Z vs CK (307); b. GO analysis of 109 DEGs unique to Vd-H vs CK (327)

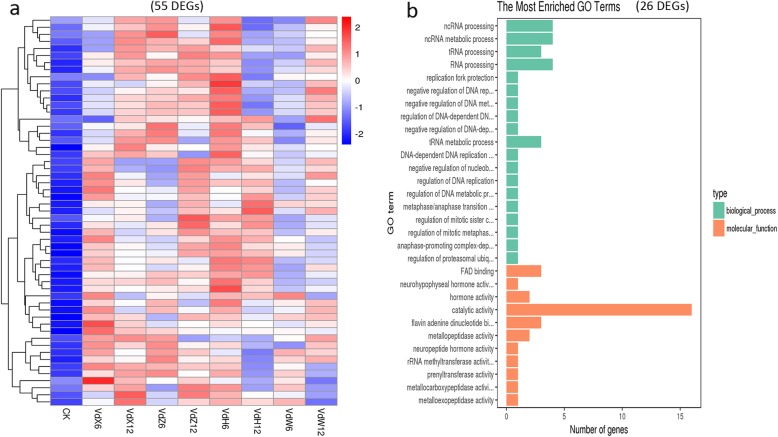

Genes related to development of V. dahliae

A total of 55 genes (Fig. 4e) whose expression were up-regulated in Vd-X, Vd-Z, Vd-H and Vd-W were considered to be required for development of V. dahliae. The Heatmap of 55 genes indicated that the expression level of these genes were obviously up-regulated in Vd-X, Vd-Z, Vd-H and Vd-W at one or two time points of cultured (Fig. 11a), which was consistent with the Veen diagram results. The 55 genes included 26 genes with known functions and 29 genes with unknown functions. Of 26 DEGs with known functions (Table 7), it is notable that several genes were associated with FAD binding and RNA processing (Fig. 11b; Additional file 10: Table S8), such as VDAG_02063, VDAG_05832, VDAG_09806, VDAG_05829, VDAG_02981. Functional analysis for these candidate genes may be useful for the study of the molecular basis of V. dahliae development.

Fig. 11.

Heatmap and GO analyses of up-regulated genes in Vd-X, Vd-Z, Vd-H and Vd-W. a. Heatmap of 55 genes found to be up-regulated in Vd-X, Vd-Z, Vd-H and Vd-W at 6 h or 12 h of cultured. The log-transformed expression values range from − 2 to 2. Red and blue bands represent high and low gene expression levels, respectively. b. The most enriched GO terms of the 26 DEGs with known functions

Table 7.

Up-regulated genes with known functions in Vd-X, Vd-Z, Vd-H and Vd-W at 6 h or 12 h

| Code | Gene ID | Enzyme name | FPKM value | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CK | VdX6 | VdX12 | VdZ6 | VdZ12 | VdH6 | VdH12 | VdW6 | VdW12 | |||

| 1 | VDAG_01200 | Multidrug resistance protein | 2.574203 | 3.176818 | 8.456135 | 10.58305 | 4.440765 | 8.923448 | 3.200822 | 3.971342 | 5.1336 |

| 2 | VDAG_02063 | L-amino-acid oxidase | 0.635877 | 0.5626 | 1.614603 | 1.483211 | 1.348462 | 1.682819 | 1.940567 | 0.826722 | 2.25874 |

| 3 | VDAG_02178 | Quinate permease | 0.058306 | 0.627263 | 0.485426 | 0.606461 | 1.024123 | 0.628178 | 0.873477 | 0.321581 | 0.459276 |

| 4 | VDAG_02520 | Response regulator receiver domain-containing protein | 11.43198 | 30.89575 | 40.29134 | 13.93595 | 49.39211 | 43.4858 | 14.60711 | 33.75135 | 13.91367 |

| 5 | VDAG_02528 | RNA-dependent RNA polymerase | 2.550404 | 6.828783 | 5.918211 | 5.244344 | 7.547659 | 8.333781 | 6.355329 | 6.082573 | 5.05485 |

| 6 | VDAG_02981 | Methyltransferase domain-containing protein | 1.048951 | 2.022277 | 2.645048 | 3.118421 | 2.771815 | 4.705878 | 1.726638 | 1.905085 | 4.283733 |

| 7 | VDAG_03099 | Glucan 1,3-beta-glucosidase | 0.304888 | 1.159252 | 1.177232 | 1.289926 | 1.029788 | 1.617254 | 1.194427 | 0.743662 | 0.829034 |

| 8 | VDAG_03536 | YetA | 14.37066 | 33.60962 | 24.66688 | 23.71565 | 30.52655 | 24.97965 | 27.41519 | 21.24693 | 27.49016 |

| 9 | VDAG_03975 | C6 zinc finger domain-containing protein | 15.00863 | 29.21758 | 18.81392 | 18.84766 | 31.24542 | 29.8705 | 26.07178 | 21.38755 | 27.99133 |

| 10 | VDAG_04598 | Glycogenin-1 | 37.06267 | 68.97229 | 48.17265 | 45.46692 | 77.10089 | 69.11893 | 70.61616 | 54.23442 | 63.30747 |

| 11 | VDAG_05008 | Peptidase M20 domain-containing protein 2 | 0.951232 | 3.683467 | 2.85524 | 2.704868 | 2.485291 | 2.347381 | 2.428679 | 2.431284 | 2.273593 |

| 12 | VDAG_05649 | BNR/Asp-box repeat domain-containing protein | 1.485317 | 5.698776 | 3.41501 | 3.134149 | 4.311877 | 5.442967 | 4.981001 | 3.789991 | 2.962473 |

| 13 | VDAG_05829 | Heat shock protein HSP98 | 2851.294 | 8213.736 | 5839.808 | 8385.88 | 7207.387 | 5492.246 | 3748.727 | 7855.11 | 6926.32 |

| 14 | VDAG_05831 | Phenylalanine ammonia-lyase | 5.327448 | 10.4713 | 14.76473 | 18.7942 | 11.65773 | 24.15234 | 5.273917 | 8.005835 | 11.82046 |

| 15 | VDAG_05832 | FAD binding domain-containing protein | 0.97946 | 5.375452 | 9.59148 | 13.22928 | 11.4021 | 29.036 | 1.738944 | 5.22337 | 11.88564 |

| 16 | VDAG_05836 | Para-hydroxybenzoate-polyprenyltransferase | 0.16421 | 0.23375 | 2.238529 | 1.346959 | 3.046437 | 4.084031 | 0.142631 | 1.331249 | 1.254863 |

| 17 | VDAG_06240 | Phytanoyl-CoA dioxygenase | 3.271209 | 4.96076 | 16.97013 | 14.02229 | 11.25868 | 20.8611 | 5.329389 | 5.988937 | 9.619971 |

| 18 | VDAG_06907 | E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase | 19.52358 | 41.99442 | 38.90181 | 40.99749 | 42.84902 | 65.42277 | 43.04462 | 32.43004 | 37.12453 |

| 19 | VDAG_07183 | Carboxypeptidase A | 0.590637 | 4.817832 | 2.275429 | 1.521062 | 2.023665 | 1.406215 | 0.779928 | 1.725569 | 0.451422 |

| 20 | VDAG_07270 | Mycocerosic acid synthase | 0.563822 | 1.191726 | 1.288242 | 1.182283 | 0.764326 | 1.502613 | 1.056965 | 0.88995 | 0.998817 |

| 21 | VDAG_07344 | Cutinase | 0 | 0.757969 | 0.60793 | 0.962218 | 1.396963 | 2.694802 | 0.561964 | 0.477185 | 1.374841 |

| 22 | VDAG_07854 | Maltose O-acetyltransferase | 2.196192 | 3.946491 | 6.820049 | 7.200627 | 3.16318 | 6.916005 | 5.754764 | 2.764381 | 4.99843 |

| 23 | VDAG_08529 | Anaphase-promoting complex subunit 8 | 13.30899 | 23.23852 | 34.1324 | 40.32327 | 24.52103 | 40.96512 | 25.52018 | 20.15623 | 27.3556 |

| 24 | VDAG_08712 | Cyanide hydratase | 0.511059 | 3.463236 | 24.39127 | 3.558516 | 18.23755 | 11.04813 | 5.794128 | 4.979065 | 1.917549 |

| 25 | VDAG_09806 | FAD binding domain-containing protein | 0.850458 | 1.504143 | 1.687359 | 1.407464 | 1.919441 | 1.757326 | 2.404167 | 1.50623 | 1.979163 |

| 26 | VDAG_10401 | Integral membrane protein | 1.080071 | 3.072609 | 4.37851 | 3.103026 | 2.956657 | 4.107363 | 3.177632 | 2.617038 | 2.934669 |

Discussion

V. dahliae can survive for many years in soil and dead plant tissues, making Verticillium wilt difficult to control, which has been likened to a bottleneck in commercial crop productivity [53, 56]. Only limited studies have focused on pathogenicity-related molecular mechanisms in the fungus, In this study, RNA-Seq was firstly used to explore and compare the transcriptomic profiles of V. dahliae after cultured with root exudates from different cotton varieties. Statistical analysis of DEGs in V. dahliae samples vs CK (Vd-0) revealed that V. dahliae responded to all kinds of root exudates but was more responsive to susceptible cultivar than to tolerant and resistant cultivars. GO analysis revealed the enriched GO terms of up-regulated genes in Vd-X vs CK (339), Vd-Z vs CK (302), Vd-H vs CK (327) were similar. However, the up-regulated genes were quite different in these samples, and only 57 up-regulated genes were found to be common in Vd-X vs CK (339), Vd-Z vs CK (302) and Vd-H vs CK (327), suggesting that the molecular mechanism of the response of V. dahliae to different root exudates from three cotton cultivars was different. GO analysis also found that enriched GO terms of up-regulated genes in Vd-X (339) and Vd-Z (302) at 6 h and 12 h of cultured were obviously different from that of Vd-X (1031) and Vd-Z (1283) at 24 h and 48 h of cultured, suggesting that V. dahliae at 6 h and 12 h of cultured were at different growth stages compared with 24 h and 48 h of cultured. The discovery of enriched GO terms hydrolase activity, hydrolyzing O-glycosyl compounds and transmembrane transport in Vd-X vs CK (339) and Vd-Z vs CK (302) suggested that 6 h and 12 h were the critical stage of V.dahliae-cotton interaction for upland cotton. For Vd-H-24 h, the enriched GO terms were similar to that in Vd-H (327) at 6 h and 12 h of cultured, suggesting that the response of V. dahliae to island cotton was more prolonged compared with upland cotton. Additionally, the number of unique genes in V. dahliae cultured with root from susceptible cotton variety (121 DEGs) was much more than in V. dahliae cultured with tolerant (66 DEGs) and resistant varieties (109 DEGs), including more hydrolase activity hydrolyzing O-glycosyl compounds and transmembrane transport related DEGs, which can partly account for the reasons why V. dahliae can cause disease in susceptible cotton.

Plant pathogenic fungi can produce a range of cell wall-degrading enzymes to facilitate infection and colonization [59, 60], including cellulase, hemicellulase, pectinase, etc. Hydrolytic enzymes, particularly cellulases and pectinases, have been considered to be important for the expression of disease symptoms and pathogenesis of V. dahliae [61, 62]. The cell wall-degrading enzymes are virulence factors, such as such as xyloglucan-specific endoglucanase [63], fungal endopolygalacturonases [64], and also function as pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs). Specifically, the cell wall-degrading enzymes contain carbohydrate-binding modules (CBM), non-catalytic protein domains that are generally associated with carbohydrate hydrolases in fungi, which are known to act as elicitors of the PAMP-triggered immunity (PTI) response in oomycetes [65, 66]. In V. dahliae, two Glycoside hydrolase 12 (GH12) proteins, VdEG1 and VdEG3 acted as PAMPs to trigger cell death and PTI independent of their enzymatic activity in Nicotiana benthamiana.

Although cell wall-degrading enzymes have been received to be related to pathogenicity of fugus, but the direct molecular evidence was not sufficient. In this study, GO analyses for the up-regulated DEGs found that genes related to hydrolase activity, hydrolyzing O-glycosyl compounds was the most significantly enriched term in molecular function category for Vd-X (339), but not in Vd-Z (302), Vd-H (327), Vd-W (168), including 16 cell wall-degrading genes, suggesting these genes would be contribute to the pathogenesis of V. dahliae. Additionally, A total of 121 DEGs unique to Vd-X (339) whose expression were obviously up-regulated after cultured with root exudates from susceptible cotton cultivar, including 9 cell wall-degrading genes. These results provided a proof of the involvement of cell wall-degrading genes in the initial steps of the roots infections and likely in pathogenesis. Recently, functional studies of cell wall-degrading related genes by targeted gene knockout have been carried out to obtain mutants deficient in one or more these genes [60, 67], but were not conclusive due to the multigene families encoding these enzymes [68]. Therefore, it is important to detect which genes were responsible for the pathogenicity of V. dahliae. In this study, 16 cell wall-degrading related genes were significantly up-regulated in Vd-X at early stage of interaction, which can be used as the target genes for studying V. dahliae pathogenicity by gene knockout. Here some genes were up-regulated in V. dahliae cultured by water, maybe resulted from no nutrient in water. Perhaps the starvation of the fungus may induce expression of genes encoding cell wall-degrading enzymes [69].

The adaptation of V. dahliae inside the host plants requires a large number of channel proteins to control the absorption of nutrients across the plasma membrane [56]. Transport proteins are integral transmembrane protein that exist permanently within and span the membrane across which they transport substances. GO analyses found that transmembrane transport term was commonly enriched in Vd-X (339), Vd-Z (302), Vd-H (327), but not enriched in Vd-W (168) at 6 h and 12 h of cultured, suggesting that they were required for the initial steps of the roots infections. Seven genes related to transmembrane transport found to be up-regulated in V. dahliae cultured by different root exudates, and 13 genes related to this term were only up-regulated in V. dahliae cultured by root exudates from susceptible cultivar. The results exhibited that genes related to this term can respond quickly to cotton root exudates, especially to the susceptible cotton, suggesting that genes related to transmembrane transport may be associated with the initial steps of the roots infections and likely in pathogenesis. The content of carbohydrate and amount of amino acids in the root exudates of susceptible cultivar was distinctly more than resistant ones [42]. Thus, V. dahliae can obtain more nutrients to provide its growth in root exudates from susceptible cotton, which may be responsible for the higher expression of transmembrane transport genes at the early stage of interaction in V. dahliae cultured by root exudates from susceptible cotton. However, few transmembrane transport genes for nutrient acquisition have been identified from V. dahliae, and their involvement in the disease process is unknown.

In short, our study firstly revealed the transcriptomes of V. dahliae cultured with root exudates from different cotton cultivars. Our results provided the clear proof at the molecular level for the association of cell wall-degrading and transmembrane transport related genes with pathogenesis of V. dahliae. The results enriched the genomic information on V. dahliae in public databases, and laid a foundation for the evaluation and understanding the molecular mechanisms of V. dahliae interacted with cotton and pathogenicity. The paper provided a framework for further functional studies of candidate genes to develop better control strategies for the cotton wilt disease.

Conclusions

In this study, we present the first comparative transcriptomic profiling analysis of V. dahliae responded to root exudates from a susceptible upland cotton cultivar, a tolerant upland cotton cultivar and a resistant island cotton cultivar. Our study provided a comprehensive examination of the biological processes in V. dahliae affected by different root exudates based on analysis of Gene Ontology (GO) terms of the differentially expressed genes, and described genes that were involved in the initial steps of the roots infections and likely in pathogenesis. Genes related to ‘hydrolase activity, hydrolyzing O-glycosyl compounds’ highly enriched in V. dahliae cultured by root exudates from susceptible cotton at early stage of interaction may be responsible for the pathogenicity of V. dahliae. Genes related to ‘transmembrane transport’ enriched in different root exudates, but not in water may be required for the initial steps of the roots infections. These expression data have advanced our understanding of key molecular events in the V. dahliae interacted with cotton, and provided a framework for further functional studies of candidate genes to develop better control strategies for the cotton wilt disease.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1: Figure S1. Results of the Pearson’s correlation analysis of biological replicates.

Additional file 2: Figure S2. The expression profiles of 8 DEGs related to hydrolase activity hydrolyzing using their FPKM value.

Additional file 3: Table S1. Summary of RNA-seq reads mapped to the reference genome and uniquely mapped’s distribution.

Additional file 4: Table S2. The most enriched GO terms of the up-regulated DEGs in V. dahliae samples vs CK.

Additional file 5: Table S3. The most enriched GO terms of the up-regulated genes in Vd-X, Vd-Z, Vd-H and Vd-W at 6 h and 12 h of cultured, respectively.

Additional file 6: Table S4. The most enriched GO terms of the up-regulated genes in Vd-X, Vd-Z, Vd-H and Vd-W of group II, respectively.

Additional file 7: Table S5. The most enriched GO terms of the 31 DEGs with known functions.

Additional file 8: Table S6. The most enriched GO terms of the 68 DEGs with known functions.

Additional file 9: Table S7. GO analyses of DEGs unique to Vd-Z vs CK (307) and Vd-H vs CK (327).

Additional file 10: Table S8. The most enriched GO terms of the 26 DEGs with known functions.

Acknowledgements

Dr. Jian Ye and Dr. Hongjie Feng is acknowledged for their good suggestions for manuscript. We would like to thank the Institute of Cotton Research of CAAS (Anyang, Henan), Jianghong Qin (Cotton Institute, Shihezi Academy of Agricultural Sciences, Xinjiang), who provided us cotton cultivar seeds. We also would like to thank Dr. Heqin Zhu (Cotton Research Institute, Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences) for providing the V. dahliae strain V991.

Abbreviations

- CBM

Carbohydrate-Binding Modules

- CT

Cycle Threshold

- DEG

Differentially Expressed Gene

- FPKM

Fragments Per Kilobase of exon per Million fragments mapped

- GH

Glycoside Hydrolase

- GO

Gene Ontology

- H

Hai7124

- MFS

the Major Facilitator Superfamily

- PAMP

Pathogen-Associated Molecular Pattern

- PTI

PAMP-Triggered Immunity

- qRT-PCR

Quantitative Real-Time PCR

- RNA-Seq

RNA Sequencing

- V. dahliae

Verticillium dahliae

- Vd

Verticillium dahliae

- X

Xinluzao 8

- Z

Zhongzhimian 2

Authors’ contributions

XZ, YL, and JS conceived and designed the experiments. XZ, WC and ZF performed the experiments. XZ, YL analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript with revision by QZ, YS, and J.S All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (Grant No. 2017YFD0101604, 2016YFD0101901), the Genetically Modified Organisms Breeding Major Project of China (Grant No.2016ZX08005–005), and the Specific Project for Crops Breeding of Shihezi University (Grant No. gxjs-yz03, YZZX201601). These funding sources had no role in the design of the study and collection, analysis, and interpretation of data and in writing the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

The gene sequences used for qRT-PCR analysis were available and download from the public database National Center for Biotechnology Information under the accession codes VDAG_10074, VDAG_01193, VDAG_01866, VDAG_03038, VDAG_03526, VDAG_04513, VDAG_07563, VDAG_08286 and VDAG_09088. All data supporting the findings of our study can be found within the manuscript and additional file tables. The transcriptomic data generated in current study are deposited in the NCBI SRA database with the BioProject accession:PRJNA545805.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The current research did not involve field studies. The cotton cultivars used in this study were obtained from Shihezi Academy of Agricultural Sciences (Shihezi, China) and the Institute of Cotton Research of Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences (Anyang, China). The collection of the plant materials was complied with institutional and national guidelines of China.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Xinyu Zhang, Email: 1554991731@qq.com.

Wenhan Cheng, Email: 363581360@qq.com.

Zhidi Feng, Email: 403677206@qq.com.

Qianhao Zhu, Email: qianhao.zhu@csiro.au.

Yuqiang Sun, Email: sunyuqiang@zstu.edu.cn.

Yanjun Li, Email: lyj20022002@sina.com.cn.

Jie Sun, Email: sunjie@shzu.edu.cn.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1186/s12864-020-6448-9.

References

- 1.Pegg GF, Brady BL. Verticillium wilts. 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Klosterman SJ, Atallah ZK, Vallad GE, Subbarao KV. Diversity, pathogenicity, and management of Verticillium species. Annu Rev Phytopathol. 2009;47:39–62. doi: 10.1146/annurev-phyto-080508-081748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tzima A, Paplomatas EJ, Rauyaree P, Kand S. Roles of the catalytic subunit of cAMP dependent protein kinasee a in virulence and development of the soilbrone plant pathogen Verticillium dahliae. Fungal Genet Biol. 2010;47(5):406–415. doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2010.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhao YL, Zhou TT, Guo HS. Hyphopodium-specific VdNoxB/VdPls1-dependent ROS-Ca2+ signaling is required for plant infection by Verticillium dahliae. PLoS Pathog. 2016;12:e1005793. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sink K, Grey WE. A root-injection method to assess Verticillium wilt resistance of peppermint (Mentha×piperita L) and its use in identifying resistant somaclones of cv black Mitcham. Euphytica. 1999;106(3):223–230. doi: 10.1023/A:1003591908308. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Daayf F, Nicole M, Boher B, Pando A, Geiger JP. Early vascular defense reactions of cotton roots infected with a defoliating mutant strain of Verticillium dahliae. Eur J Plant Pathol. 1997;103(2):125–136. doi: 10.1023/A:1008620410471. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mao S, Js X, Cl L, Mz S. Responses of cotton antioxidant system to Verticillium wilt. Acta Gossypii Sinica. 1996;8(2):92–96. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xia Z, Achar PN. Biochemical changes in cotton infected with Verticillium dahliae. African Plant Protection. 1999;6(6):1148–1158. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bolek Y, Magill CW, Thaxton PM, El-Zik KM, Bell AA. Defense responses of cotton to Verticillium wilt. Natl Cotton Council Beltwide Cotton Conference. 2000;1:133. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shaban M, Miao Y, Ullah A, QadirKhan A, Menghwar H, HamidKhan A, MahmoodAhmed M, AdnanTabassum M, Lf Z. Physiological and molecular mechanism of defense in cotton against Verticillium dahliae. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2018;125:193. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2018.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gao W, Long L, Zhu LF, Xu L, Gao WH, Sun LQ, Liu LL, Zhang XL. Proteomic and virus-induced gene silencing (VIGS) analyses reveal that gossypol, brassinosteroids, and jasmonic acid contribute to the resistance of cotton to Verticillium dahliae. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2013;12(12):3690–3703. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M113.031013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang W, Zhang H, Liu K, Jian G, Qi F, Si N. Large-scale identification of Gossypium hirsutum genes associated with Verticillium dahliae by comparative transcriptomic and reverse genetics analysis. PLoS One. 2017;12(8):e0181609. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0181609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]