Abstract

Background

Pneumonia caused by bacterial pathogens is the leading cause of mortality in children in low‐income countries. Early administration of antibiotics improves outcomes.

Objectives

To identify effective antibiotic drug therapies for community‐acquired pneumonia (CAP) of varying severity in children by comparing various antibiotics.

Search methods

We searched CENTRAL 2012, Issue 10; MEDLINE (1966 to October week 4, 2012); EMBASE (1990 to November 2012); CINAHL (2009 to November 2012); Web of Science (2009 to November 2012) and LILACS (2009 to November 2012).

Selection criteria

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) in children of either sex, comparing at least two antibiotics for CAP within hospital or ambulatory (outpatient) settings.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently extracted data from the full articles of selected studies.

Main results

We included 29 trials, which enrolled 14,188 children, comparing multiple antibiotics. None compared antibiotics with placebo.

Assessment of quality of study revealed that 5 out of 29 studies were double‐blind and allocation concealment was adequate. Another 12 studies were unblinded but had adequate allocation concealment, classifying them as good quality studies. There was more than one study comparing co‐trimoxazole with amoxycillin, oral amoxycillin with injectable penicillin/ampicillin and chloramphenicol with ampicillin/penicillin and studies were of good quality, suggesting the evidence for these comparisons was of high quality compared to other comparisons.

In ambulatory settings, for treatment of World Health Organization (WHO) defined non‐severe CAP, amoxycillin compared with co‐trimoxazole had similar failure rates (odds ratio (OR) 1.18, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.91 to 1.51) and cure rates (OR 1.03, 95% CI 0.56 to 1.89). Three studies involved 3952 children.

In children with severe pneumonia without hypoxaemia, oral antibiotics (amoxycillin/co‐trimoxazole) compared with injectable penicillin had similar failure rates (OR 0.84, 95% CI 0.56 to 1.24), hospitalisation rates (OR 1.13, 95% CI 0.38 to 3.34) and relapse rates (OR 1.28, 95% CI 0.34 to 4.82). Six studies involved 4331 children below 18 years of age.

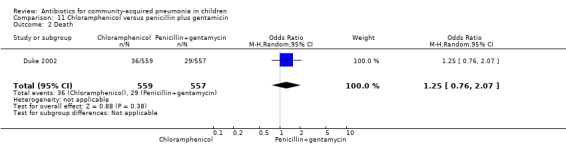

In very severe CAP, death rates were higher in children receiving chloramphenicol compared to those receiving penicillin/ampicillin plus gentamicin (OR 1.25, 95% CI 0.76 to 2.07). One study involved 1116 children.

Authors' conclusions

For treatment of patients with CAP in ambulatory settings, amoxycillin is an alternative to co‐trimoxazole. With limited data on other antibiotics, co‐amoxyclavulanic acid and cefpodoxime may be alternative second‐line drugs. Children with severe pneumonia without hypoxaemia can be treated with oral amoxycillin in an ambulatory setting. For children hospitalised with severe and very severe CAP, penicillin/ampicillin plus gentamycin is superior to chloramphenicol. The other alternative drugs for such patients are co‐amoxyclavulanic acid and cefuroxime. Until more studies are available, these can be used as second‐line therapies.

There is a need for more studies with radiographically confirmed pneumonia in larger patient populations and similar methodologies to compare newer antibiotics. Recommendations in this review are applicable to countries with high case fatalities due to pneumonia in children without underlying morbidities and where point of care tests for identification of aetiological agents for pneumonia are not available.

Plain language summary

Different antibiotics for community‐acquired pneumonia in otherwise healthy children younger than 18 years of age in hospital and outpatient settings

Pneumonia is the leading cause of mortality in children under five years of age. Most cases of community‐acquired pneumonia (CAP) in low‐income countries are caused by bacteria. This systematic review identified 29 randomised controlled trials from many different countries enrolling 14,188 children and comparing antibiotics for treatment of CAP in children. Most were single studies only.

We found that for outpatient treatment of pneumonia, amoxycillin is an alternative treatment to co‐trimoxazole. Oral amoxycillin in children with severe pneumonia without hypoxia (i.e. a decreased level of oxygen), and who are feeding well, may be effective. For very severe pneumonia, a combination of penicillin or ampicillin and gentamycin is more effective than chloramphenicol alone. Reports of adverse events were not available in many studies. Wherever information on adverse events was available, it did not differ between two drugs compared except that gastrointestinal side effects were more commonly reported with erythromycin compared to azithromycin.

Limitations of this review are that only five studies met all the quality assessment criteria and for most comparisons of the efficacy of antibiotics only one or two studies were available.

Background

Pneumonia is the leading single cause of mortality in children aged less than five years, with an estimated incidence of 0.29 and 0.05 episodes per child‐year in low‐income and high‐income countries, respectively. It is estimated that a total of around 156 million new episodes occur each year and most of these occur in India (43 million), China (21 million), Pakistan (10 million) and Bangladesh, Indonesia and Nigeria (six million each) (Rudan 2008). In 2010, out of 7.6 million deaths in children below five years of age, 1.4 million (18.3%) deaths were due to pneumonia (Liu 2012). Reducing mortality due to pneumonia may help in reducing childhood and under five‐year old mortality rates (Liu 2012). The commonest bacterial pathogens isolated in children under five years with pneumonia are Streptococcus pneumoniae (S. pneumoniae) (30% to 50%) and Haemophilus influenzae (H. influenzae) (10% to 30%) (Falade 2011), and 50% of deaths due to pneumonia in this age group are attributed to these two organisms (Shann 1995). To reduce the infant and under five‐year child mortality rate, it is important to reduce mortality due to pneumonia by appropriate intervention in the form of antibiotics. Selection of first‐line antibiotics for empirical treatment of pneumonia is crucial for office practice as well as public health.

Description of the condition

Pneumonia is defined as an infection of the lung parenchyma (alveoli) by microbial agents. It is difficult to identify the causative organism in most cases of pneumonia. The methods used for identification of the aetiologic agents include blood culture, lung puncture, nasopharyngeal aspiration and immune assays of blood and urine tests. Lung puncture is an invasive procedure associated with significant morbidity and hence cannot be performed routinely in most cases. The yield from blood cultures is too low (5% to 15% for bacterial pathogens) to be relied upon (MacCracken 2000). There are few studies that document the aetiology of pneumonia in children below five years of age from low‐income countries. Most studies carried out blood cultures for bacterial aetiology of pneumonia. Some studies carried out nasopharyngeal aspirates and identification of virus and atypical organisms. A review of 14 studies involving 1096 lung aspirates taken from hospitalised children prior to administration of antibiotics reported bacterial pathogens in 62% of cases (Berman 1990). In 27% of patients, the common bacterial pathogens identified were Streptococcus pneumoniae (S. pneumoniae) and Haemophilus influenzae (H. influenzae) (Berman 1990). Studies using nasopharyngeal aspirates for identification of viral agents suggest that about 40% of pneumonia in children below five years of age is caused by viral agents, with the commonest viral pathogen being respiratory syncytial virus (Maitreyi 2000). In infants under three months of age, common pathogens include S. pneumoniae,H. influenzae, gram‐negative bacilli and Staphylococcus (WHOYISG 1999). The causative organisms are different in high‐income countries and include more viral and atypical organisms (Gendrel 1997; Ishiwada 1993; Numazaki 2004; Wubbel 1999). Therefore, treatment regimens may be different in high‐income and low‐income countries. The reference standard for diagnosis of pneumonia is X‐ray film of the chest. However, it does not have the necessary sensitivity and specificity to identify aetiological agents (i e. bacterial or viral). Obtaining an X‐ray film in all suspected pneumonia cases may not be cost‐effective as it does not affect the outcome. Therefore, diagnosis of pneumonia is based on clinical criteria. Treatment of pneumonia includes administration of antibiotics, either in hospital or in an ambulatory setting. Administration of antibiotics for all clinically diagnosed pneumonia may lead to antibiotic prescription even for those cases caused by viral infection. Since clinical or radiological findings cannot differentiate viral or bacterial pneumonia and due to the absence of point of care tests for routine use, empirical treatment with antibiotics in countries with high case fatalities due to pneumonia is recommended by the World health Organization (WHO).

Description of the intervention

Administration of appropriate antibiotics at an early stage of pneumonia improves the outcome of the illness, particularly when the causative agent is bacterial. The WHO has provided guidelines for early diagnosis and assessment of the severity of pneumonia on the basis of clinical features (WHOYISG 1999) and suggests administration of co‐trimoxazole as a first‐line drug. The commonly used antibiotics for community‐acquired pneumonia (CAP) include co‐trimoxazole, amoxycillin, oral cephalosporins and macrolide drugs. Despite evidence of rising bacterial resistance to co‐trimoxazole (IBIS 1999; Timothy 1993), studies conducted in the same time period showed good clinical efficacy of oral co‐trimoxazole for non‐severe pneumonia (Awasthi 2008; Rasmussen 1997; Straus 1998). However, one study reported a doubling of clinical failure rates with co‐trimoxazole treatment when compared to treatment with amoxycillin in severe and radiologically confirmed pneumonia (Straus 1998). A meta‐analysis of all the trials on pneumonia based on the case‐management approach proposed by the WHO (identification of pneumonia on clinical symptoms/signs and administration of empirical antimicrobial agents) has found a reduction in overall mortality as well as pneumonia‐related mortality (Sazawal 2003). Various antibiotics have been used for varying severities of pneumonia. Antibiotics are administered in hospital or in ambulatory settings.

How the intervention might work

Pneumonia is the leading cause of mortality in children below five years of age. It is not easy to identify aetiological agents in children with pneumonia. To meet the public health goal of reducing child mortality due to pneumonia, empirical antibiotic administration is relied upon in most instances. This is necessary in view of the inability of most commonly available laboratory tests to identify causative pathogens.

Why it is important to do this review

Empirical antibiotic administration is the mainstay of treatment of pneumonia in children. Administration of the most appropriate antibiotic as the first‐line treatment may improve the outcome of pneumonia. Many antibiotics are prescribed to treat pneumonia. Therefore, it is important to know which works best for pneumonia in children. The last review of all available randomised controlled trials (RCTs) on antibiotics used for pneumonia in children was published in 2010 (Kabra 2010). Since then, five new trials (Ambroggio 2012; Bari 2011; Nogeova 1997; Ribeiro 2011; Soofi 2012) have been published. Additional information on the epidemiology of pneumonia in children has been published. Therefore, we have updated this review and included new data and also carried out a meta‐analysis on the treatment of severe pneumonia with oral antibiotics.

Objectives

To identify effective antibiotic drug therapies for community‐acquired pneumonia (CAP) of varying severity in children by comparing various antibiotics.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) comparing antibiotics for CAP in children. We considered only those studies using the case definition of pneumonia (as given by the WHO) or radiologically confirmed pneumonia in this review.

Types of participants

We included children under 18 years of age with CAP treated in a hospital or community setting. We excluded studies describing pneumonia post‐hospitalisation in immunocompromised patients (for example, following surgical procedures) or patients with underlying illnesses like congenital heart disease or those in an immune deficient state.

Types of interventions

We compared any intervention with antibiotics (administered by intravenous route, intramuscular route or orally) with another antibiotic for the treatment of CAP.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Clinical cure. The definition of clinical cure is symptomatic and involves clinical recovery by the end of treatment.

Treatment failure rates. The definition of treatment failure is the presence of any of the following: development of chest in‐drawing, convulsions, drowsiness or inability to drink at any time, respiratory rate above the age‐specific cut‐off point on completion of treatment, or oxygen saturation of less than 90% (measured by pulse oximetry) after completion of the treatment. Loss to follow‐up or withdrawal from the study at any time after recruitment indicated failure in the analysis.

Secondary outcomes

The clinically relevant outcome measures were as follows.

Relapse rate: defined as children declared 'cured', but developing recurrence of disease at follow‐up in a defined period.

Hospitalisation rate (in outpatient studies only): defined as the need for hospitalisation in children who were getting treatment or in an ambulatory (outpatient) setting.

Length of hospital stay: duration of total hospital stay (from day of admission to discharge) in days.

Need for change in antibiotics: children required change in antibiotics from the primary regimen.

Additional interventions used: any additional intervention in the form of mechanical ventilation, steroids, vaso‐pressure agents, etc.

Mortality rate.

Search methods for identification of studies

We retrieved studies through a search strategy which included cross‐referencing. We checked the cross‐references of all the studies manually.

Electronic searches

For this update we searched the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) 2012, Issue 10, part of The Cochrane Library, www.thecochranelibrary.com (accessed 7 November 2012); MEDLINE (September 2009 to October week 4, 2012); EMBASE (September 2009 to November 2012); CINAHL (2009 to November 2012); Web of Science (2009 to November 2012) and LILACS (2009 to November 2012). Details of the previous search are in Appendix 1.

To search CENTRAL and MEDLINE we combined the following search strategy with the validated search strategy for identifying child studies developed by Boluyt (Boluyt 2008). We used the Cochrane Highly Sensitive Search Strategy to identify randomised trials in MEDLINE: sensitivity‐ and precision‐maximising version (2008 revision); Ovid format (Lefebvre 2011). We adapted the search strategy to search EMBASE (Appendix 2), CINAHL (Appendix 3), Web of Science (Appendix 4) and LILACS (Appendix 5).

MEDLINE (Ovid)

1 exp Pneumonia/ 2 pneumon*.tw. 3 bronchopneumon*.tw. 4 pleuropneumon*.tw. 5 cap.tw. 6 or/1‐5 7 exp Anti‐Bacterial Agents/ 8 antibiotic*.tw. 9 (amoxycillin* or amoxycillin* or ampicillin* or azithromycin* or augmentin* or benzylpenicillin* or b‐lactam* or beta‐lactam* or clarithromycin* or ceftriaxone* or cefuroxime* or cotrimoxazole* or co‐trimoxazole* or co‐amoxyclavulanic acid or cefotaxime* or ceftriaxone* or ceftrioxone* or cefditoren* or chloramphenicol* or cefpodioxime* or cephradine* or cephalexin* or cefaclor* or cefetamet* or cephalosporin* or erythromycin* or gentamicin* or gentamycin* or levofloxacin* or macrolide* or minocyclin* or moxifloxacin* or penicillin* or quinolone* or roxithromycin* or sulphamethoxazole* or sulfamethoxazole* or tetracyclin* or trimethoprim*).tw,nm. (248104) 10 or/7‐9 11 6 and 10

Searching other resources

We also searched bibliographies of selected articles to identify any additional trials not recovered by the electronic searches.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors (SKK, RL) independently selected potentially relevant studies based on their title and abstract. We retrieved the complete texts of these studies electronically or by contacting the trial authors. Two review authors (SKK, RL) independently reviewed the results for inclusion.

Data extraction and management

A person who was not involved in the review gave all relevant studies a serial number to mask the authors' names and institutions, the location of the study, reference lists and any other potential identifiers. Two review authors (SKK, RL) independently reviewed the results for inclusion in the analysis. We resolved differences about study quality through discussion. We recorded data on a pre‐structured data extraction form. We assessed publication bias using The Cochrane Collaboration's 'Risk of bias' tool (Higgins 2011). We included data from cluster‐RCTs after adjustment for the design effect. We calculated the design effect by 1+(M‐1) ICC; where M is the average cluster size and ICC is the intracluster correlation coefficient (Higgins 2011).

Before combining the studies for each of the outcome variables, we carried out an assessment of heterogeneity using Review Manager (RevMan 2012) software. We performed a sensitivity analysis to check the importance of each study in order to see the effect of inclusion and exclusion criteria. We computed both the effect size and summary measures with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) using RevMan 2012. We used a random‐effects model to combine the study results for all the outcome variables.

We collected data on the primary outcome (cure rate/failure rate) and secondary outcomes (relapse rate, rate of hospitalisation and complications, need for change in antibiotics, need for additional interventions and mortality). When available, we also recorded additional data on potential confounders such as prior antibiotic therapy and nutritional status.

We did multiple analyses, firstly on studies comparing the same antibiotics. We also attempted to perform indirect comparisons of various drugs when studies with direct comparisons were not available. For example, we compared antibiotics A and C when a comparison of antibiotics A and B was available and likewise a separate comparison between antibiotics B and C. We only did this type of comparison if the inclusion and exclusion criteria of these studies, the dose and duration of the common intervention (antibiotic B), baseline characteristics and the outcomes assessed were similar (Bucher 1997).

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

We assessed risk of bias in all included studies using The Cochrane Collaboration's 'Risk of bias' tool (Higgins 2011).

1. Sequence generation: assessed as yes, no or unclear Yes: when the study described the method used to generate the allocation sequence in sufficient detail. No: sequence not generated. Unclear: when it was not described or incompletely described.

2. Allocation concealment: assessed as yes, no or unclear Yes: when the study described the method used to conceal the allocation sequence in sufficient detail. No: described details where allocation concealment was not done. Unclear: when it was not described or incompletely described.

3. Blinding of participants, personnel and outcome assessors: assessed as yes, no or unclear Yes: when it was a double‐blind study. No: when it was an unblinded study. Unclear: not clearly described.

4. Incomplete outcome data: assessed as yes, unclear Yes: describe the completeness of outcome data for each main outcome, including attrition and exclusions from the analysis. Unclear: either not described or incompletely described.

5. Free of selective outcome reporting: assessed as yes, no or unclear Yes: results of study free of selective reporting. Details of all the participants enrolled in the study are included in the paper. No: details of all the enrolled participants not given in the paper. Unclear: details of all the enrolled participants incompletely described.

6. Other sources of bias Among the other sources of potential bias considered was funding agencies and their role in the study. We recorded funding agencies as governmental agencies, universities and research organisations or pharmaceutical companies. We considered studies supported by pharmaceutical companies to be unclear unless the study defined the role of the pharmaceutical companies. We also considered studies not mentioning the source of funding as unclear under this heading.

Measures of treatment effect

The main outcome variables were failure rates or cure rates. Treatment effect in the form of failure rates was calculated by making 2 x 2 tables and calculating odds ratios (ORs) for each comparison. We expressed the results as ORs with 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

Unit of analysis issues

All except one study were RCTs. One was a cluster‐RCT (Awasthi 2008). We included data from cluster‐RCTs after adjustment for the design effect. We calculated the design effect by 1+(M‐1) ICC; where M is the average cluster size and ICC is the intracluster correlation coefficient (Higgins 2011).

Dealing with missing data

We contacted trial authors for missing data. However, we could not retrieve any missing data from any of the studies. We excluded two new studies in this update (Bari 2011; Soofi 2012).

Assessment of heterogeneity

For each of the outcome variables, we carried out an assessment of heterogeneity with Breslow's test of homogeneity in accordance with the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011).

Assessment of reporting biases

Before combining the study results, we checked for publication bias using a funnel plot. For each of the outcome variables (cure rate, failure rate, relapse rate, rate of hospitalisation, the complications needed for change in antibiotics and mortality rate) we used a 2 x 2 table for each study and performed Breslow's test of homogeneity to determine variation in study results.

Data synthesis

For each comparison, we prepared 2 x 2 tables. We calculated ORs and 95% CIs. We used a random‐effects model for all the comparisons.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

In this review we included RCTs that compared two antibiotics in children with pneumonia. We performed a subgroup analysis of children with radiologically confirmed pneumonia. For each of the outcome variables, we carried out an assessment of heterogeneity with Breslow's test of homogeneity using RevMan 2012 (see Data collection and analysis).

Sensitivity analysis

Most comparisons were for two to three trials. If there was significant heterogeneity, we conducted a sensitivity analysis. We conducted multiple analyses after excluding one study data at a time.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

Two review authors (SKK, RL) screened the article titles. We short‐listed 49 trials as potential RCTs to be included and we attempted to collect the full‐text articles. We obtained the full text for 48 trials. A third person who was not involved in the review masked the papers for identifiers. Two review authors (SKK, RL) independently extracted data by using a pre‐designed data extraction form; the extracted data matched completely.

Included studies

We identified 29 studies for inclusion, with the following comparisons.

Azithromycin with erythromycin: four studies (Harris 1998; Kogan 2003; Roord 1996; Wubbel 1999), involving 457 children aged two months to 16 years.

Clarithromycin with erythromycin: one study (Block 1995), involving 357 children below 15 years of age with clinical or radiographically confirmed pneumonia treated in an ambulatory setting.

Co‐trimoxazole with amoxycillin: three studies (Awasthi 2008; CATCHUP 2002; Straus 1998), involving 2347 children aged two months to 59 months. Total numbers of events and effective sample size in one cluster‐randomised controlled trial (Awasthi 2008) were calculated after adjusting for the design effect.

Co‐trimoxazole with procaine penicillin: two studies (Keeley 1990; Sidal 1994), involving 723 children aged three months to 12 years.

Chloramphenicol with penicillin and gentamycin together: one study (Duke 2002), involving 1116 children aged one month to five years.

Single‐dose benzathine penicillin with procaine penicillin: two studies (Camargos 1997; Sidal 1994), involving 176 children between two and 12 years of age in one study (Sidal 1994) and 105 children aged between three months to 14 years in the other similar study (Camargos 1997).

Amoxycillin with procaine penicillin: one study (Tsarouhas 1998), involving 170 children aged six months to 18 years.

Ampicillin with chloramphenicol plus penicillin: one study (Deivanayagam 1996), involving 115 children aged five months to four years.

Co‐trimoxazole with single‐dose procaine penicillin followed by oral ampicillin: one study (Campbell 1988), involving 134 children aged below five years.

Penicillin with amoxycillin: two studies (Addo‐Yobo 2004; Atkinson 2007), involving 1905 children aged three months to 59 months.

Co‐trimoxazole with chloramphenicol: one study (Mulholland 1995), involving 111 children aged under five years.

Cefpodoxime with co‐amoxyclavulanic acid: one study (Klein 1995), involving 348 children aged three months to 11.5 years.

Azithromycin with amoxycillin: one study (Kogan 2003), involving 47 children aged one month to 14 years.

Amoxycillin with co‐amoxyclavulanic acid: one study (Jibril 1989), involving 100 children aged two months to 12 years.

Chloramphenicol in addition to penicillin with ceftriaxone: one study (Cetinkaya 2004), involving 97 children aged between two to 24 months admitted to hospital with severe pneumonia.

Levofloxacin and comparator (co‐amoxyclavulanic acid or ceftriaxone): one study (Bradley 2007) involving 709 children aged 0.5 to 16 years of age with CAP treated in hospital or in an ambulatory setting.

Parenteral ampicillin followed by oral amoxycillin with home‐based oral amoxycillin: one study (Hazir 2008) involving 2037 children between three months to 59 months of age with WHO‐defined severe pneumonia.

Chloramphenicol with ampicillin and gentamicin: one study (Asghar 2008), involving 958 children between two to 59 months with very severe pneumonia.

Penicillin and gentamicin with co‐amoxyclavulanic acid (Bansal 2006), involving 71 children with severe and very severe pneumonia between two months to 59 months of age.

Co‐amoxyclavulanic acid with cefuroxime or clarithromycin: one study (Aurangzeb 2003), involving 126 children between two to 72 months of age.

Ceftibuten with cefuroxime axetil: one study involving 140 children between one to 12 years of age with CAP that was radiographically confirmed (Nogeova 1997).

Oxacillin/ceftriaxone with co‐amoxyclavulanic acid: one study involving 104 children between age two months to five years with very severe pneumonia (Ribeiro 2011).

Excluded studies

We excluded 20 trials.

Four studies were carried out in adult participants (Bonvehi 2003; Fogarty 2002; Higuera 1996; van Zyl 2002).

Three studies included children with severe infections or sepsis (Haffejee 1984; Mouallem 1976; Vuori‐Holopaine 2000).

One study did not provide separate data for children (Sanchez 1998).

Two cluster‐RCTs (Bari 2011; Soofi 2012) compared oral amoxycillin or standard treatment for severe pneumonia in children below five years of age. Patients on conventional treatment received either intravenous antibiotics in hospital or oral medications at home or no treatment. Results were available as oral treatment with amoxycillin in comparison with standard treatment (referral and antibiotics). Separate data on patients who received intravenous antibiotics were not available and data could not be obtained from the trial authors.

Three studies were not RCTs (Agostoni 1988; Ambroggio 2012; Paupe 1992).

Three studies only compared the duration of antibiotic use (Hasali 2005; Peltola 2001; Ruhrmann 1982); of these, one study (Hasali 2005) also did not report the outcome in the form of cure or failure rates.

One studied only sequential antibiotic use (Al‐Eiden 1999).

One compared azithromycin with symptomatic treatment for recurrent respiratory tract infection only (Esposito 2005).

The full‐text article could not be obtained for one study (Lu 2006).

One study (Lee 2008) was excluded because the outcome was not in the form of cure or failure rates.

Risk of bias in included studies

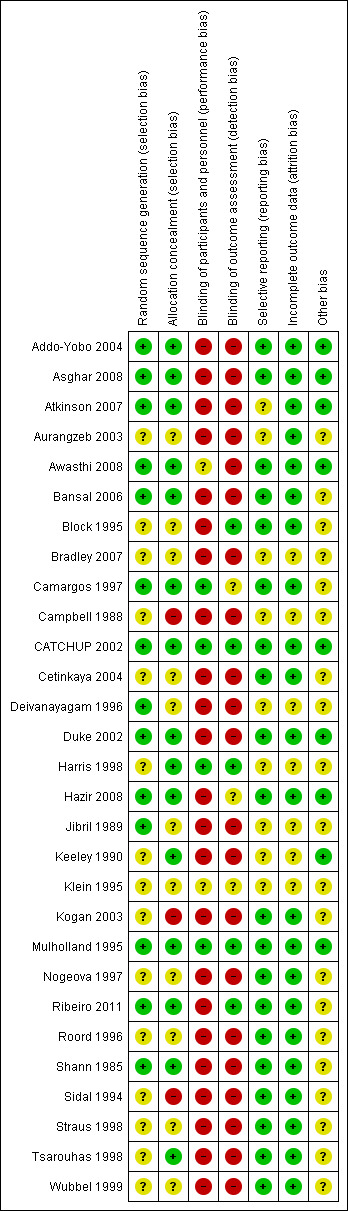

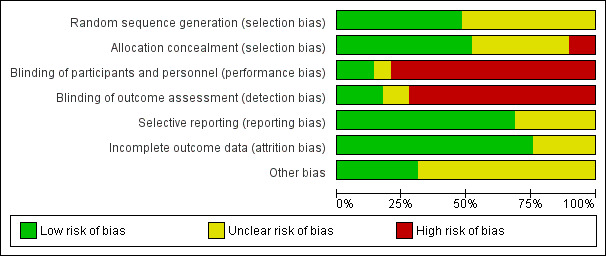

The overall risk of bias is presented graphically and summarised (Figure 1; Figure 2)

1.

'Risk of bias' summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

2.

'Risk of bias' graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

Details of sequence generation were described in 17 studies (Addo‐Yobo 2004; Asghar 2008; Atkinson 2007; Awasthi 2008; Bansal 2006; Camargos 1997; CATCHUP 2002; Cetinkaya 2004; Deivanayagam 1996;Duke 2002; Hazir 2008; Jibril 1989; Keeley 1990; Mulholland 1995; Ribeiro 2011; Roord 1996; Shann 1985), were not clear in 10 studies (Aurangzeb 2003; Block 1995; Bradley 2007; Campbell 1988; Harris 1998; Klein 1995; Nogeova 1997; Straus 1998; Tsarouhas 1998; Wubbel 1999) and sequence was not generated in two studies (Kogan 2003; Sidal 1994).

Allocation

Allocation concealment was adequate in 17 studies (Addo‐Yobo 2004; Asghar 2008; Atkinson 2007; Awasthi 2008; Bansal 2006; Camargos 1997; CATCHUP 2002; Cetinkaya 2004; Deivanayagam 1996; Duke 2002; Harris 1998; Hazir 2008; Keeley 1990; Mulholland 1995; Ribeiro 2011; Shann 1985; Tsarouhas 1998), it was unclear in nine studies (Aurangzeb 2003; Block 1995; Bradley 2007; Campbell 1988; Jibril 1989; Klein 1995; Nogeova 1997; Straus 1998; Wubbel 1999) and no concealment was done in three studies (Kogan 2003; Roord 1996; Sidal 1994).

Blinding

Only five studies (CATCHUP 2002; Cetinkaya 2004; Harris 1998; Mulholland 1995; Straus 1998) were double‐blinded. The rest of the studies were unblinded.

Incomplete outcome data

Data were fully detailed in 20 studies (Addo‐Yobo 2004; Asghar 2008; Atkinson 2007; Aurangzeb 2003; Awasthi 2008; Bansal 2006; Block 1995; Camargos 1997; CATCHUP 2002; Cetinkaya 2004; Duke 2002; Hazir 2008; Kogan 2003; Mulholland 1995; Nogeova 1997; Ribeiro 2011; Roord 1996; Straus 1998; Tsarouhas 1998; Wubbel 1999) and in the remaining studies details of attrition and exclusions from the analysis were unavailable.

Selective reporting

Selective reporting of data was unclear in 12 studies (Atkinson 2007; Aurangzeb 2003; Bradley 2007; Campbell 1988; Deivanayagam 1996; Harris 1998; Jibril 1989; Keeley 1990; Klein 1995; Shann 1985; Sidal 1994; Wubbel 1999). The rest of the studies were free from selective reporting.

Other potential sources of bias

The source of funding was not mentioned in 15 studies (Aurangzeb 2003; Bansal 2006; Camargos 1997; Campbell 1988; Cetinkaya 2004; Deivanayagam 1996; Jibril 1989; Klein 1995; Kogan 2003; Nogeova 1997; Ribeiro 2011; Shann 1985; Sidal 1994; Straus 1998; Tsarouhas 1998). Five studies were funded by pharmaceutical companies (Block 1995; Bradley 2007; Harris 1998; Roord 1996; Wubbel 1999). Eight studies were supported by the WHO, Medical Research Council or universities (Addo‐Yobo 2004; Asghar 2008; Atkinson 2007; Awasthi 2008; Duke 2002; Hazir 2008; Keeley 1990; Mulholland 1995). One study (CATCHUP 2002) was supported by the WHO in addition to pharmaceutical companies. Information on clearance by Ethics Committees or Institutional Review Boards was available for all except four studies (Aurangzeb 2003; Jibril 1989; Keeley 1990; Sidal 1994).

Effects of interventions

Studies comparing ambulatory setting treatment of non‐severe pneumonia

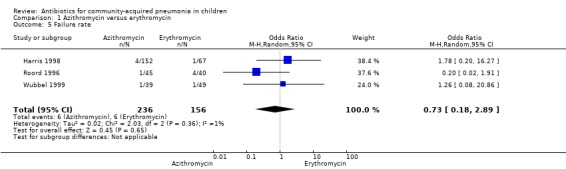

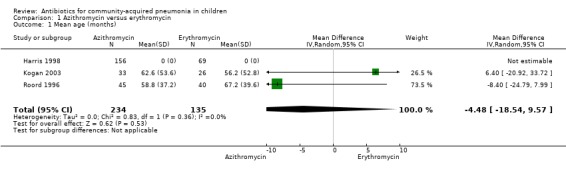

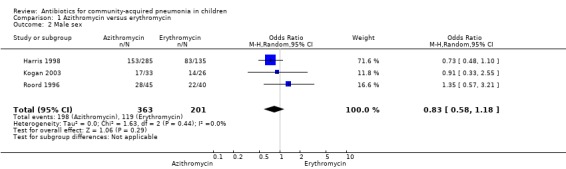

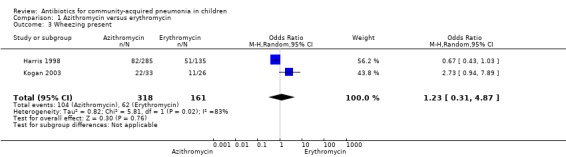

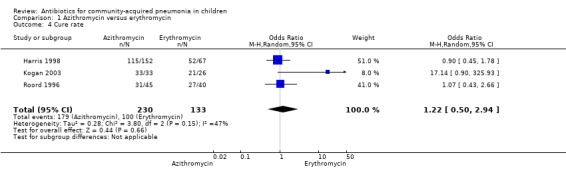

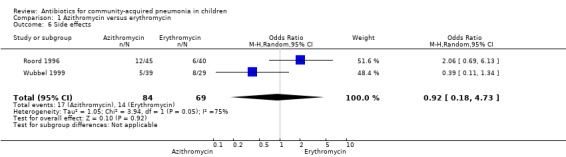

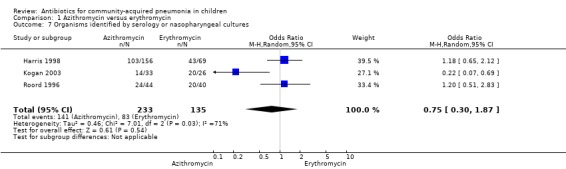

Azithromycin versus erythromycin (Analysis 1)

Four studies (Harris 1998; Kogan 2003; Roord 1996; Wubbel 1999) compared erythromycin with azithromycin and enrolled 623 children. One study (Harris 1998) was double‐blinded with adequate allocation concealment and three studies (Kogan 2003; Roord 1996; Wubbel 1999) were unblinded and did not have adequate allocation concealment. Information on the presence of wheezing was available in two studies (Harris 1998; Kogan 2003): 104 out of 318 (33%) children experienced wheezing in the azithromycin group, while 62 out of 161 (39%) in the erythromycin group experienced wheezing. The failure rates in the azithromycin and erythromycin groups were six out of 236 (2.5%) and six out of 156 (3.8%), respectively (OR 0.73, 95% CI 0.18 to 2.89) (Analysis 1.5) There were no significant side effects in either group. Three studies reported data on aetiologic organisms separately for each of the two treatment groups (Harris 1998; Kogan 2003; Roord 1996); there were 234 organisms identified in the azithromycin group and 135 in the erythromycin group (Roord 1996). The distribution of different organisms was similar in the two groups. There were 24 organisms identified in the fourth study (Wubbel 1999) in 59 participants tested.

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Azithromycin versus erythromycin, Outcome 5 Failure rate.

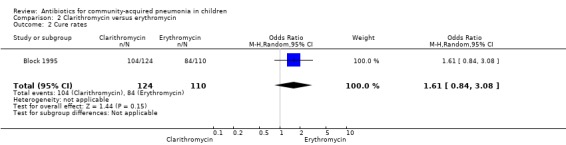

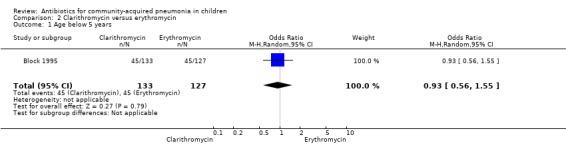

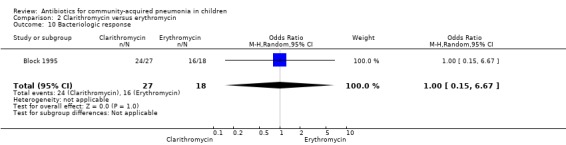

Clarithromycin versus erythromycin (Analysis 2)

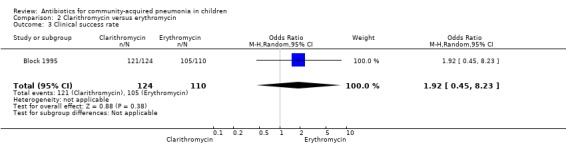

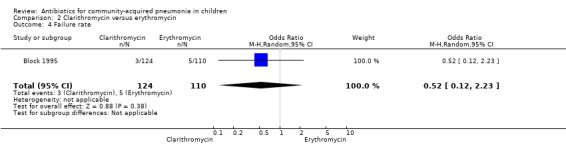

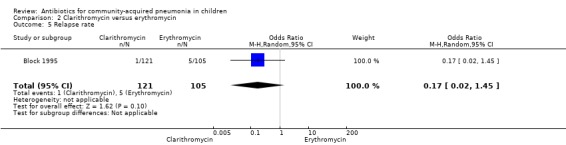

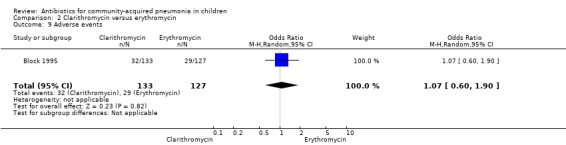

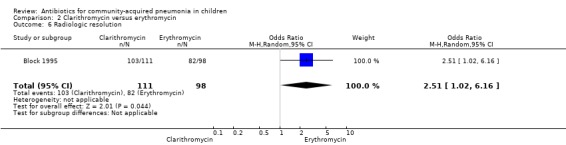

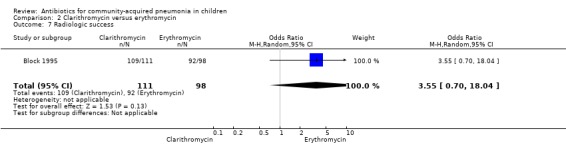

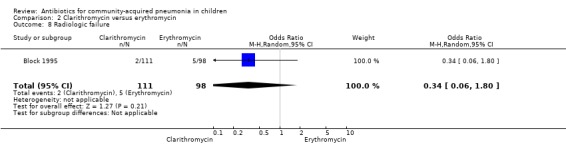

One study (Block 1995) compared erythromycin and clarithromycin; 234 children below 15 years of age with clinical or radiographically confirmed pneumonia were treated in an ambulatory setting. The trial was single‐blinded and allocation concealment was unclear. The following outcomes were similar between the two groups: cure rate (OR 1.61, 95% CI 0.84 to 3.08) (Analysis 2.2), clinical success rate (OR 1.92, 95% CI 0.45 to 8.23) (Analysis 2.3), failure rate (OR 0.52, 95% CI 0.12 to 2.23) (Analysis 2.4) , relapse rate (OR 0.17, 95% CI 0.02 to 1.45) (Analysis 2.5) and adverse events (OR 1.07, 95% CI 0.6 to 1.90) (Analysis 2.9). Resolution of pneumonia (diagnosed radiologically) was more frequent in the clarithromycin group as compared to the erythromycin group (OR 2.51, 95% CI 1.02 to 6.16) (Analysis 2.6). However, there were no differences in the radiologic improvement rates (OR 3.55, 95% CI 0.7 to 18.04) (Analysis 2.7) or radiologic failure rates (OR 0.34, 95% CI 0.06 to 1.80) (,Analysis 2.8) both of which were established with radiological evidence.

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Clarithromycin versus erythromycin, Outcome 2 Cure rates.

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Clarithromycin versus erythromycin, Outcome 3 Clinical success rate.

2.4. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Clarithromycin versus erythromycin, Outcome 4 Failure rate.

2.5. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Clarithromycin versus erythromycin, Outcome 5 Relapse rate.

2.9. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Clarithromycin versus erythromycin, Outcome 9 Adverse events.

2.6. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Clarithromycin versus erythromycin, Outcome 6 Radiologic resolution.

2.7. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Clarithromycin versus erythromycin, Outcome 7 Radiologic success.

2.8. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Clarithromycin versus erythromycin, Outcome 8 Radiologic failure.

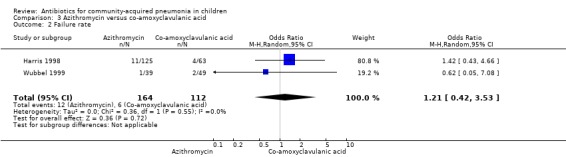

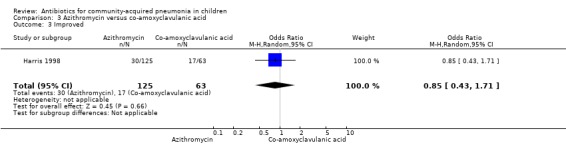

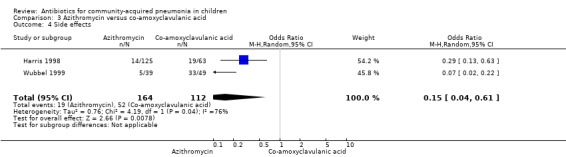

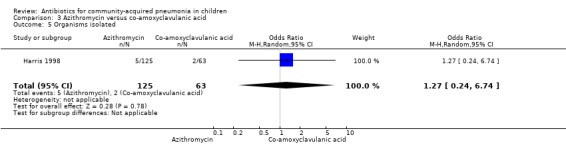

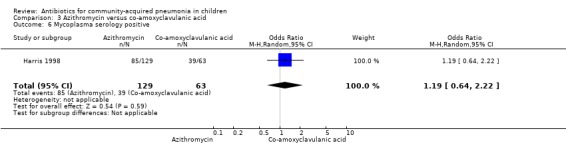

Azithromycin versus co‐amoxyclavulanic acid (Analysis 3)

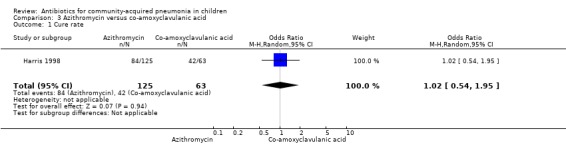

Two studies (Harris 1998; Wubbel 1999) compared these two drugs in 283 children below five years of age. One study (Harris 1998) was double‐blinded and allocation concealment was adequate while the other study (Wubbel 1999) was unblinded with inadequate allocation concealment. The cure rates (available for one study) (OR 1.02, 95% CI 0.54 to 1.95) (Analysis 3.1), failure rates (available for both studies) (OR 1.21, 95% CI 0.42 to 3.53) (Analysis 3.2) and improvement rates (OR 0.85, 95% CI 0.43 to 1.71) (Analysis 3.3) were similar in the two groups. There were fewer side effects reported in the azithromycin group (OR 0.15, 95% CI 0.04 to 0.61) (Analysis 3.4). The organisms isolated were S. pneumoniae in 28 children, H. influenzae in one, Mycoplasma pneumoniae (M. pneumoniae) in 36 and Chlamydia pneumoniae (C. pneumoniae) in 20. The separate data for isolation of organisms in the two groups were available in one study only (Harris 1998). The organisms isolated in this study (Harris 1998) were S. pneumoniae and H. influenzae in one patient each in the azithromycin group. Investigations for mycoplasma were positive in 21 out of the 129 children (16%) tested in the azithromycin group and nine out of the 66 children (14%) tested in the co‐amoxyclavulanic acid group. Investigations for C. pneumoniae were positive in 13 out of the 129 children (10%) tested in the azithromycin group and four out of the 66 children (6%) tested in the co‐amoxyclavulanic acid group.

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Azithromycin versus co‐amoxyclavulanic acid, Outcome 1 Cure rate.

3.2. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Azithromycin versus co‐amoxyclavulanic acid, Outcome 2 Failure rate.

3.3. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Azithromycin versus co‐amoxyclavulanic acid, Outcome 3 Improved.

3.4. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Azithromycin versus co‐amoxyclavulanic acid, Outcome 4 Side effects.

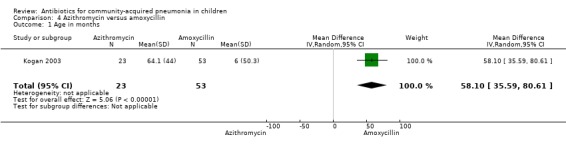

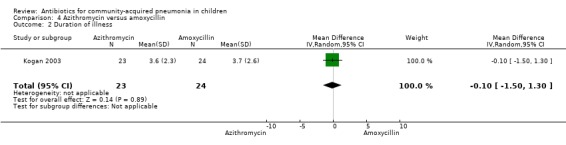

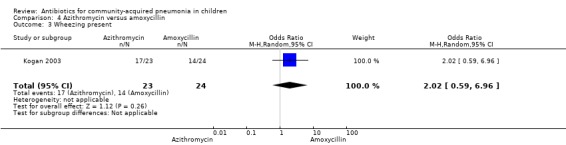

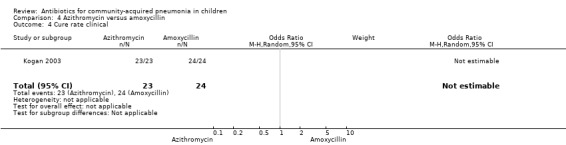

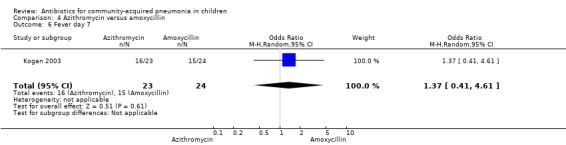

Azithromycin versus amoxycillin (Analysis 4)

One study involving 47 children aged between one month and 14 years with classical pneumonia compared these two drugs (Kogan 2003). Children treated with azithromycin were older than those treated with amoxycillin (OR 58.1, 95% CI 35.59, 80.61). The study was unblinded and allocation concealment was also inadequate. All children recovered at the end of treatment in both the groups. There were 19 organisms identified in the 47 children tested (10 in the azithromycin group and nine in the amoxycillin group). The identification rates were similar in the two groups. Organisms included M. pneumoniae (in five and three children for the azithromycin and amoxycillin groups, respectively), S. pneumoniae (in four and three, respectively) and others (in one and three, respectively).

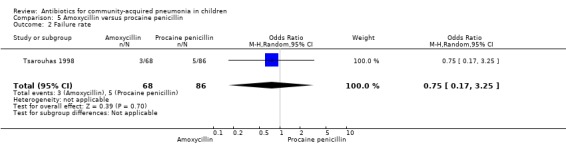

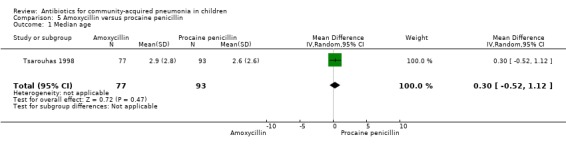

Amoxycillin versus procaine penicillin (Analysis 5)

One study involving 170 children aged six months to 18 years was identified (Tsarouhas 1998). The study was unblinded but allocation concealment was adequate. The age distribution in the two groups was comparable. The failure rates were similar in the two groups (OR 0.75, 95% CI 0.17 to 3.25) (Analysis 5.2).

5.2. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Amoxycillin versus procaine penicillin, Outcome 2 Failure rate.

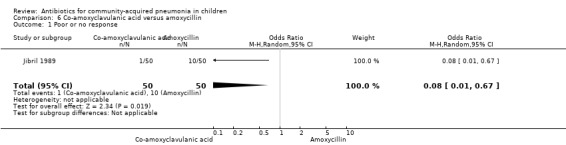

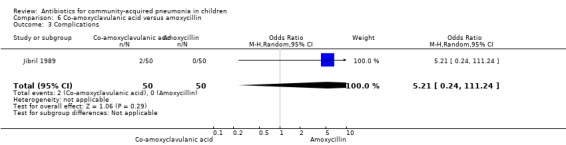

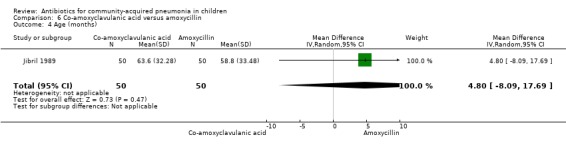

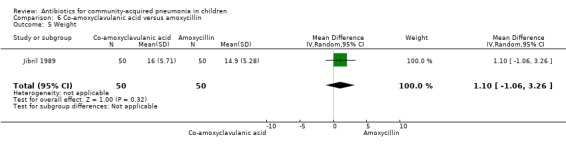

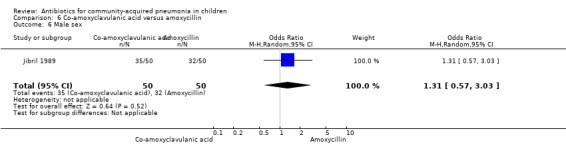

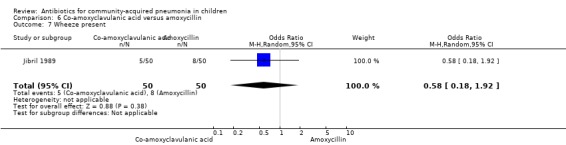

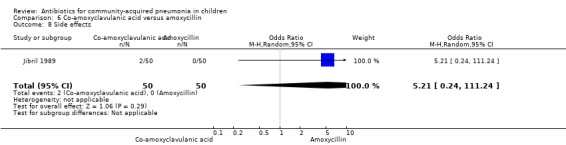

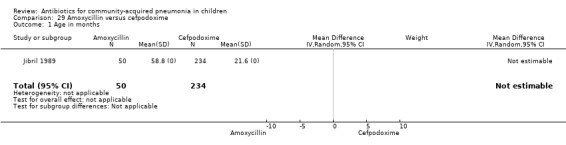

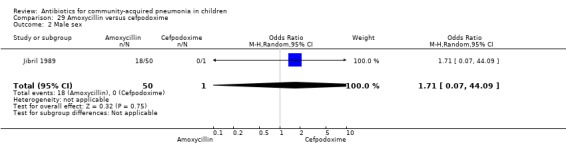

Co‐amoxyclavulanic acid versus amoxycillin (Analysis 6)

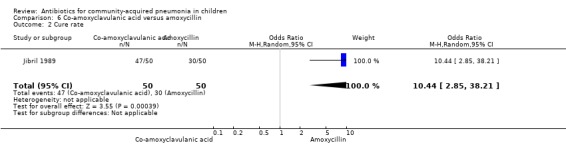

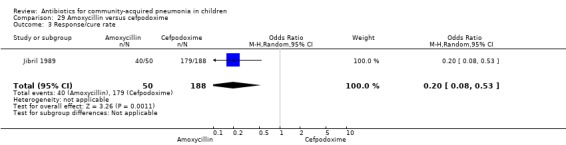

One study involved 100 children between two and 12 years of age. It was an open‐label study on children suffering from clinically diagnosed bacterial pneumonia (Jibril 1989). The study was unblinded and allocation concealment was also inadequate. Age and sex distribution, presence of wheeze and mean weight in the two groups were comparable. Cure rate was better with co‐amoxyclavulanic acid (OR 10.44, 95% CI 2.85 to 38.21) (Analysis 6.2).

6.2. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Co‐amoxyclavulanic acid versus amoxycillin, Outcome 2 Cure rate.

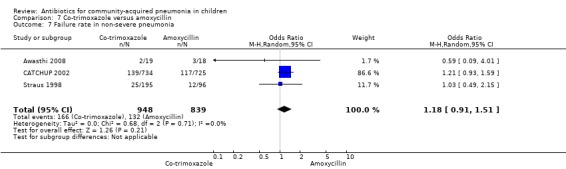

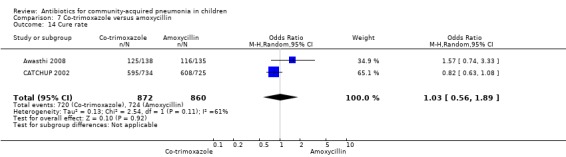

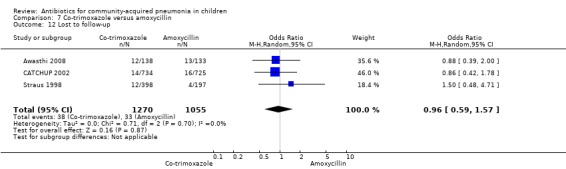

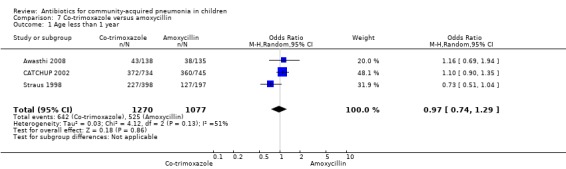

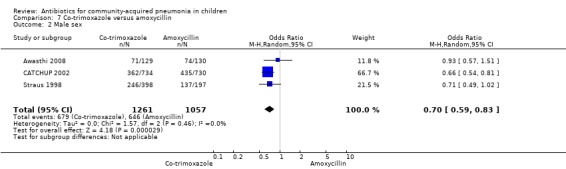

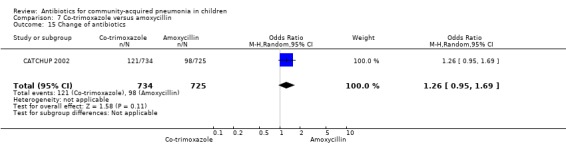

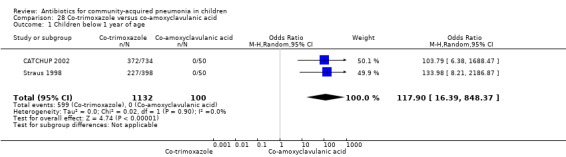

Co‐trimoxazole versus amoxycillin (Analysis 7)

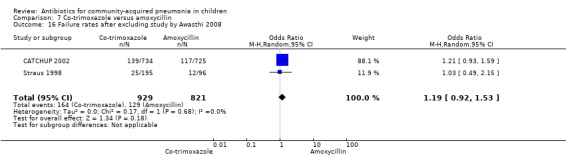

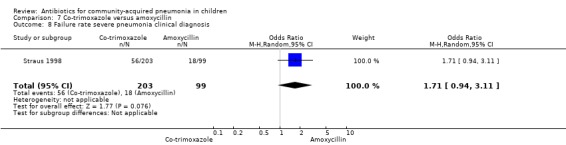

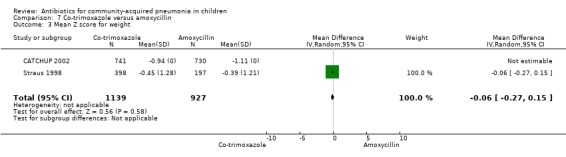

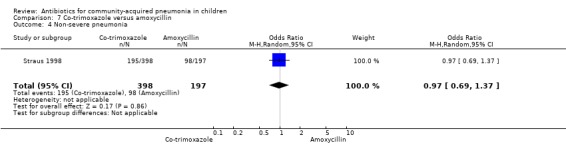

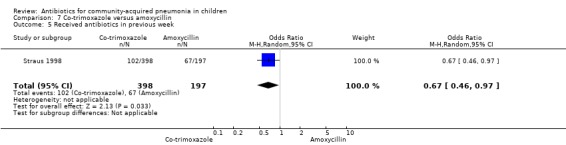

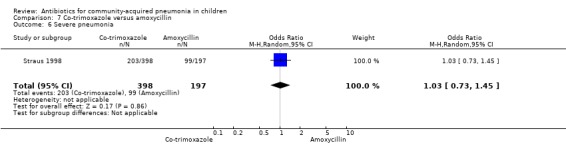

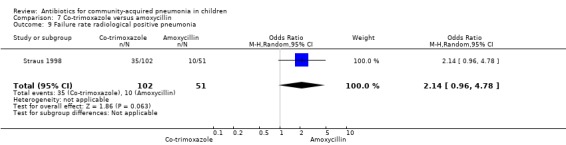

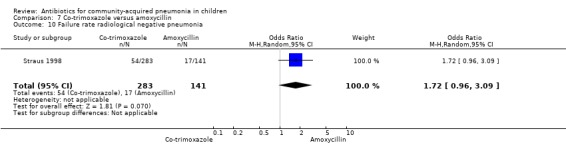

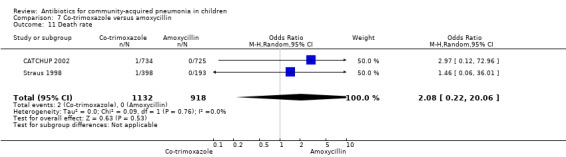

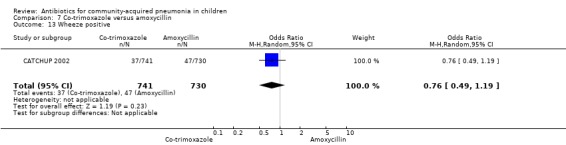

Three multicentre studies (Awasthi 2008; CATCHUP 2002; Straus 1998) involving 2346 children (1270 in the co‐trimoxazole group and 1077 in the amoxycillin group) between two months and 59 months of age have compared co‐trimoxazole and amoxycillin. The diagnosis of pneumonia was based on clinical criteria. Two studies (CATCHUP 2002; Straus 1998) were double‐blinded and allocation concealment was adequate. A third study (Awasthi 2008) was open‐label and cluster‐randomisation was done (the randomisation unit was Primary Health Centre) and in this study assessment of the primary outcome of treatment failure was done on day four for the amoxycillin group and day six for the co‐trimoxazole group; total numbers of events and effective sample size in this study (Awasthi 2008) were calculated after adjusting for the design effect. All studies included children with non‐severe pneumonia; one study (Straus 1998) also included 301 children with severe pneumonia. In pooled data the failure rate in non‐severe pneumonia was similar in the two groups (OR 1.18, 95% CI 0.91 to 1.51) (Analysis 7.7). The cure rate could be extracted in two studies (Awasthi 2008; CATCHUP 2002) and it was not different in either treatment group (OR 1.03, 95% CI 0.56 to 1.89) (Analysis 7.14) Loss to follow‐up was comparable in the two groups (OR 0.96, 95% CI 0.59 to 1.57) (Analysis 7.12). There were only two deaths in both the groups. The organisms isolated from blood cultures were H. influenzae in 79 children (52 in the co‐trimoxazole group and 27 in the amoxycillin group) and S. pneumoniae in 49 children (36 in the co‐trimoxazole group and 13 in the amoxycillin group); the distribution was similar in the two groups. In view of the difference in the time of assessment for the primary outcome in one study (Awasthi 2008), we performed analysis for failure rates in non‐severe pneumonia after excluding this study. The results did not alter significantly; failure rates in the two groups were similar (OR 1.19, 95% CI 0.92 to 1.53) (.Analysis 7.16) Failure rate in severe pneumonia available in one study was similar in the two groups (OR 1.71, 95% CI 0.94 to 3.11) (Analysis 7.8)).

7.7. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Co‐trimoxazole versus amoxycillin, Outcome 7 Failure rate in non‐severe pneumonia.

7.14. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Co‐trimoxazole versus amoxycillin, Outcome 14 Cure rate.

7.12. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Co‐trimoxazole versus amoxycillin, Outcome 12 Lost to follow‐up.

7.16. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Co‐trimoxazole versus amoxycillin, Outcome 16 Failure rates after excluding study by Awasthi 2008.

7.8. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Co‐trimoxazole versus amoxycillin, Outcome 8 Failure rate severe pneumonia clinical diagnosis.

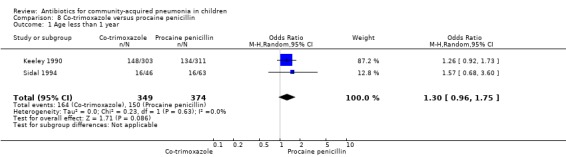

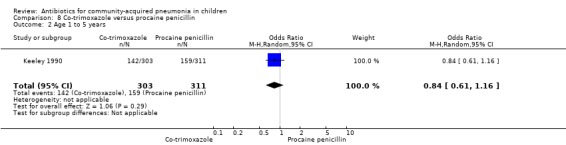

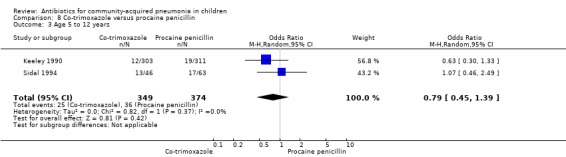

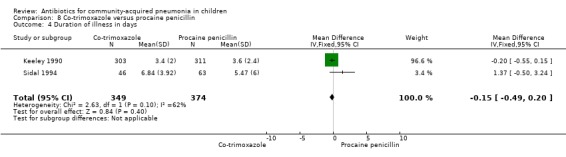

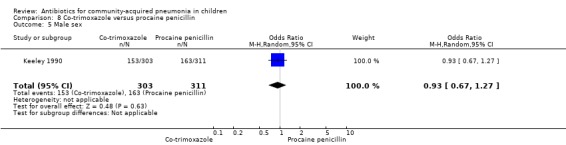

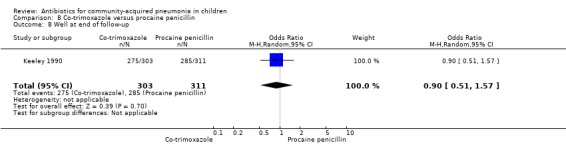

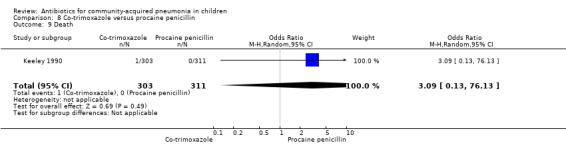

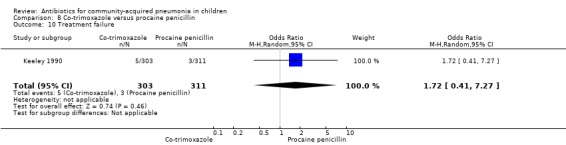

Co‐trimoxazole versus procaine penicillin (Analysis 8)

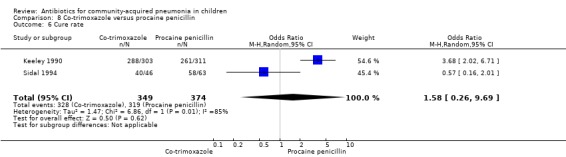

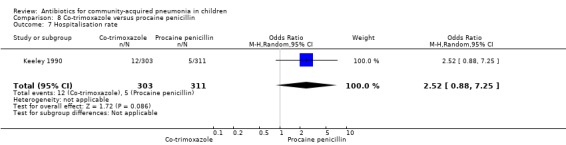

Two studies (Keeley 1990; Sidal 1994) enrolled 723 children between three months and 12 years of age. Both studies were unblinded and allocation concealment was adequate in one study (Keeley 1990). The cure rate was similar in the two groups (OR 1.58, 95% CI 0.26 to 9.69) (.Analysis 8.6) Rate of hospitalisation was available in only one study and was similar in the two groups (OR 2.52, 95% CI 0.88 to 7.25) (.Analysis 8.7) There was only one death.

8.6. Analysis.

Comparison 8 Co‐trimoxazole versus procaine penicillin, Outcome 6 Cure rate.

8.7. Analysis.

Comparison 8 Co‐trimoxazole versus procaine penicillin, Outcome 7 Hospitalisation rate.

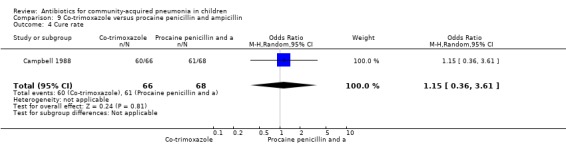

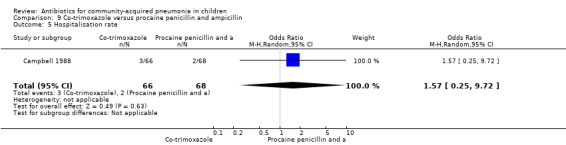

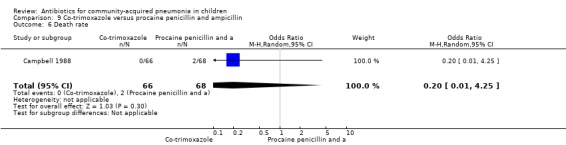

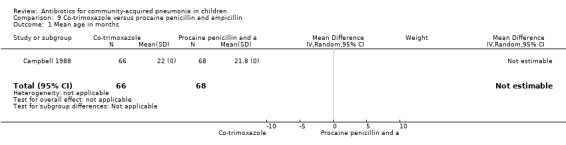

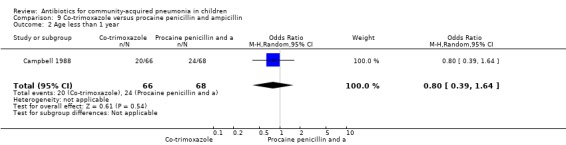

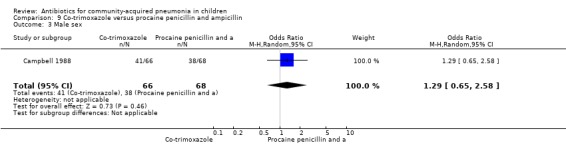

Co‐trimoxazole versus single‐dose procaine penicillin followed by oral ampicillin for five days (Analysis 9)

One study was included that had enrolled 134 children below five years of age with severe pneumonia as defined by WHO criteria (Campbell 1988). The study was unblinded and allocation concealment was not clearly stated. The cure rates (OR 1.15, 95% CI 0.36 to 3.61) (Analysis 9.4), hospitalisation rates (OR 1.57, 95% CI 0.25 to 9.72) (Analysis 9.5) and death rates (OR 0.20, 95% CI 0.01 to 4.25) (Analysis 9.6) were similar for the two groups.

9.4. Analysis.

Comparison 9 Co‐trimoxazole versus procaine penicillin and ampicillin, Outcome 4 Cure rate.

9.5. Analysis.

Comparison 9 Co‐trimoxazole versus procaine penicillin and ampicillin, Outcome 5 Hospitalisation rate.

9.6. Analysis.

Comparison 9 Co‐trimoxazole versus procaine penicillin and ampicillin, Outcome 6 Death rate.

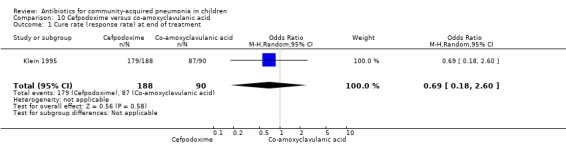

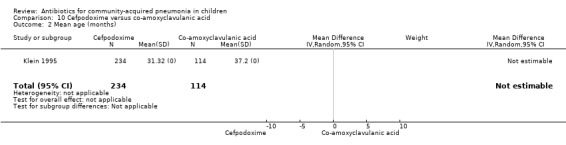

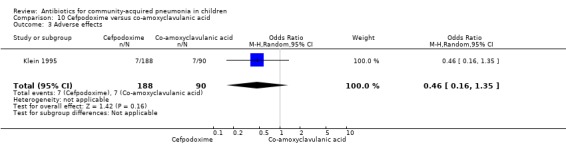

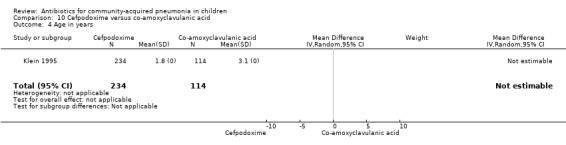

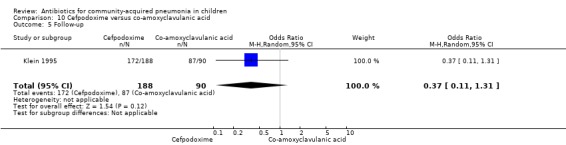

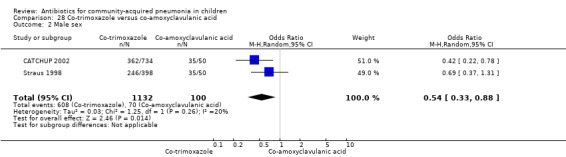

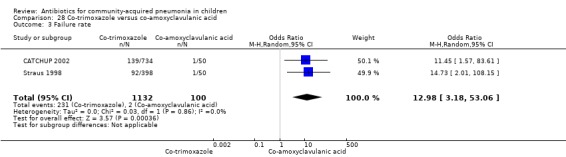

Cefpodoxime versus co‐amoxyclavulanic acid (Analysis 10)

One multicentre study (Klein 1995) enrolled 348 children between three months and 11.5 years of age. The study was unblinded and allocation concealment was inadequate. The age distribution in the two groups was comparable. The response rate at the end of 10 days of treatment was comparable in the two groups (OR 0.69, 95% CI 0.18 to 2.60) (Analysis 10.1). Organisms were isolated in 59 cases. These organisms were H. influenzae in 28 participants (47.5%), S. pneumoniae in 14 (23%), M. catarrhalis in seven (11.9%) and H. parainfluenzae in four (6.8). There was no significant difference in the bacteriologic efficacy of either group (100% versus 96.4%).

10.1. Analysis.

Comparison 10 Cefpodoxime versus co‐amoxyclavulanic acid, Outcome 1 Cure rate (response rate) at end of treatment.

Studies comparing treatment of hospitalised children with severe/very severe pneumonia

Chloramphenicol versus penicillin plus gentamycin (Analysis 11)

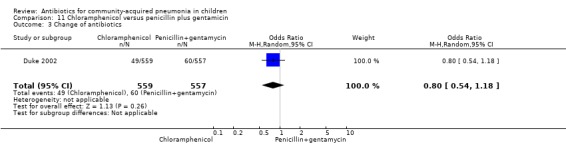

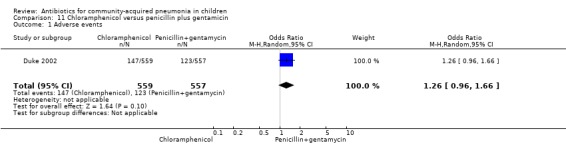

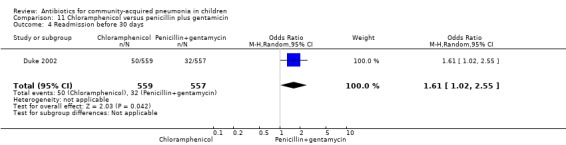

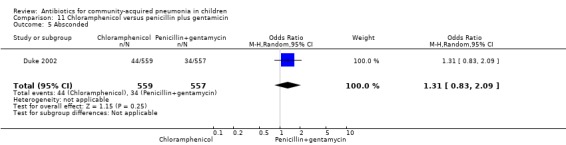

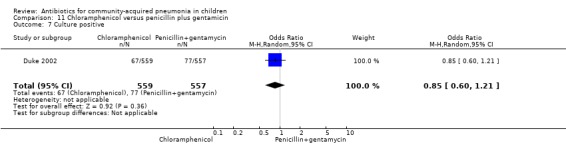

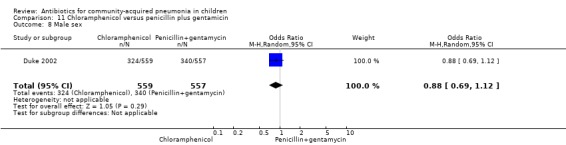

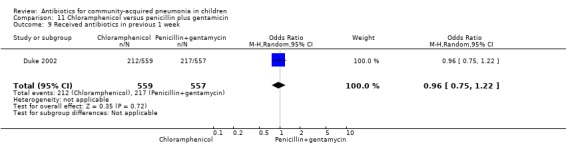

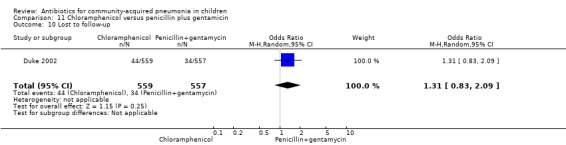

One multicentre study including 1116 children aged between one month and five years compared chloramphenicol with penicillin and gentamycin. This was an open‐label RCT in children with severe pneumonia that was carried out in Papua New Guinea (Duke 2002). Allocation concealment was adequate. There was no significant difference between the two groups in positive cultures, children who had received antibiotics earlier and loss to follow‐up. Need for change in antibiotics (OR 0.80, 95% CI 0.54 to 1.18) (Analysis 11.3), death rates (OR 1.25, 95% CI 0.76 to 2.07) (Analysis 11.2) and adverse events (OR 1.26, 95% CI 0.96 to 1.66) (Analysis 11.1) were similar in the two groups. However, re‐admission rates before 30 days favoured the penicillin‐gentamycin combination over chloramphenicol (OR 1.61, 95% CI 1.02 to 2.55) (Analysis 11.4). Bacterial pathogens were identified in 144 children (67 in children receiving chloramphenicol and 77 in the other group). Isolation rates or sensitivity of the organism and failure rates did not differ between the two groups.

11.3. Analysis.

Comparison 11 Chloramphenicol versus penicillin plus gentamicin, Outcome 3 Change of antibiotics.

11.2. Analysis.

Comparison 11 Chloramphenicol versus penicillin plus gentamicin, Outcome 2 Death.

11.1. Analysis.

Comparison 11 Chloramphenicol versus penicillin plus gentamicin, Outcome 1 Adverse events.

11.4. Analysis.

Comparison 11 Chloramphenicol versus penicillin plus gentamicin, Outcome 4 Readmission before 30 days.

Chloramphenicol with ampicillin and gentamycin (Analysis 12)

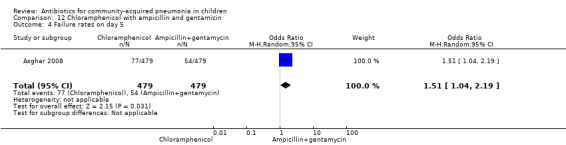

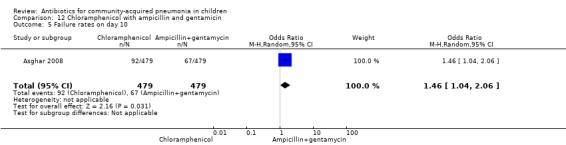

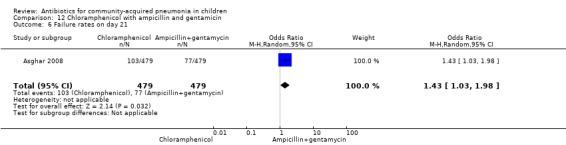

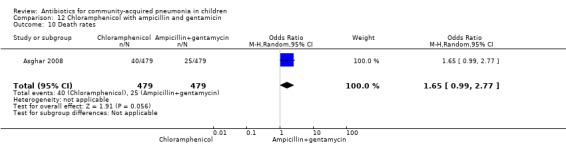

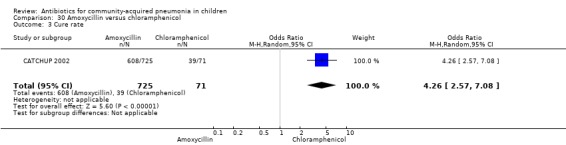

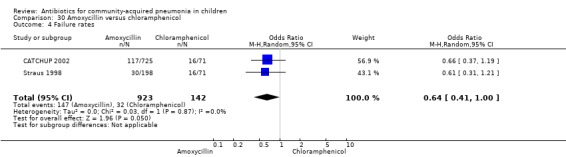

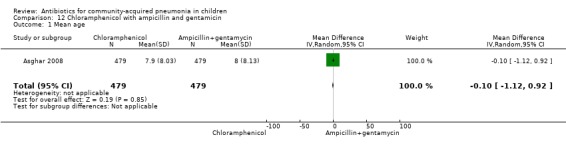

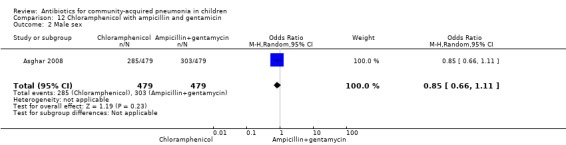

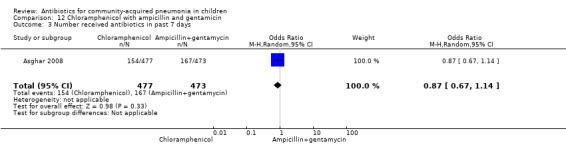

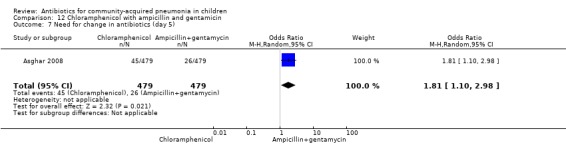

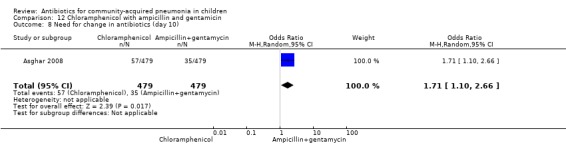

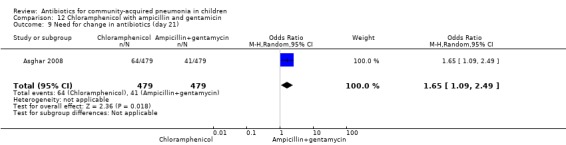

One multicentre study was identified; this study enrolled 958 children who were hospitalised with WHO‐defined very severe pneumonia (Asghar 2008). The study was unblinded and allocation concealment was adequate. Mean age, proportion of boys and number of children who had received antibiotics before enrolment were comparable in the two groups. Failure rates on day five (OR 1.51, 95% CI 1.04 to 2.19) (Analysis 12.4), day 10 (OR 1.46, 95% CI 1.04 to 2.06) (Analysis 12.5) and day 21 (OR 1.43, 95% CI 1.03 to 1.98) (Analysis 12.6) were significantly higher in those receiving chloramphenicol as compared to ampicillin and gentamycin. Death rates were higher in those receiving chloramphenicol (OR 1.65, 95% CI 0.99 to 2.77) (Analysis 12.10).

12.4. Analysis.

Comparison 12 Chloramphenicol with ampicillin and gentamicin, Outcome 4 Failure rates on day 5.

12.5. Analysis.

Comparison 12 Chloramphenicol with ampicillin and gentamicin, Outcome 5 Failure rates on day 10.

12.6. Analysis.

Comparison 12 Chloramphenicol with ampicillin and gentamicin, Outcome 6 Failure rates on day 21.

12.10. Analysis.

Comparison 12 Chloramphenicol with ampicillin and gentamicin, Outcome 10 Death rates.

Chloramphenicol plus penicillin versus ceftriaxone (Analysis 13)

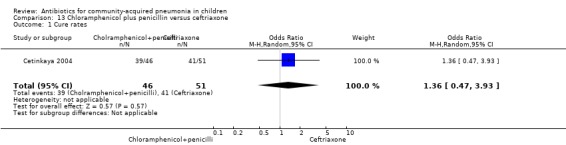

One double‐blind study fulfilled the inclusion criteria; the study enrolled 97 children between 2 and 24 months of age diagnosed with severe CAP with probable bacterial aetiology (Cetinkaya 2004). Allocation concealment was adequate. Ages in the two groups were comparable (details not available). Cure rates in the two groups were similar (OR 1.36, 95% CI 0.47 to 3.93) (Analysis 13.1).

13.1. Analysis.

Comparison 13 Chloramphenicol plus penicillin versus ceftriaxone, Outcome 1 Cure rates.

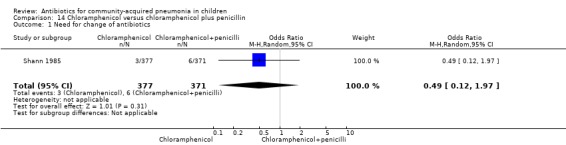

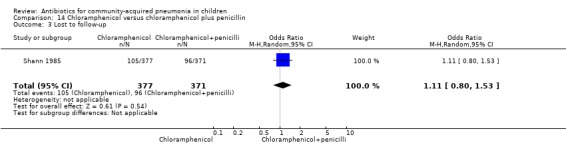

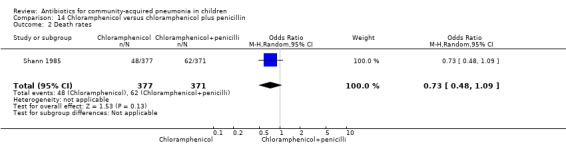

Chloramphenicol alone versus chloramphenicol plus penicillin (Analysis 14)

One study (Shann 1985) from Papua New Guinea involved 748 hospitalised children (age not clear) with severe pneumonia. The study was unblinded but allocation concealment was adequate. Need for change in antibiotics (OR 0.49, 95% CI 0.12 to 1.97) (Analysis 14.1), loss to follow‐up (OR 1.11, 95% CI 0.80 to 1.53) (Analysis 14.3) and deaths rates (OR 0.73, 95% CI 0.48 to 1.09) (Analysis 14.2) were comparable in the two groups.

14.1. Analysis.

Comparison 14 Chloramphenicol versus chloramphenicol plus penicillin, Outcome 1 Need for change of antibiotics.

14.3. Analysis.

Comparison 14 Chloramphenicol versus chloramphenicol plus penicillin, Outcome 3 Lost to follow‐up.

14.2. Analysis.

Comparison 14 Chloramphenicol versus chloramphenicol plus penicillin, Outcome 2 Death rates.

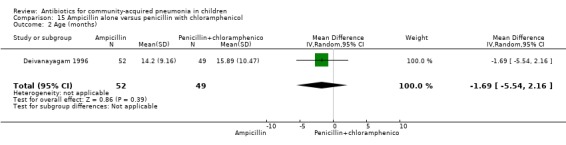

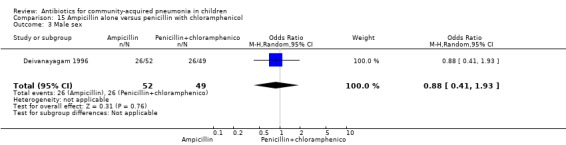

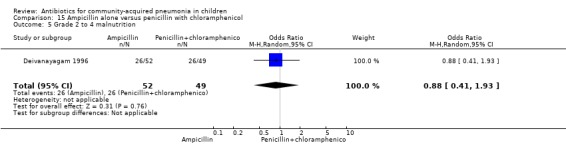

Ampicillin alone versus penicillin with chloramphenicol (Analysis 15)

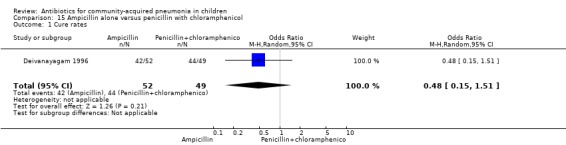

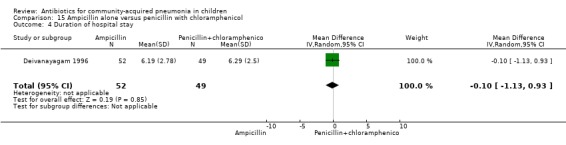

One trial involving 115 children between five months and four years of age was identified (Deivanayagam 1996). The study was unblinded and allocation concealment was adequate. Age and sex distribution and proportion of children with severe malnutrition were comparable in the two groups. The cure rates (OR 0.48, 95% CI 0.15 to 1.51) (Analysis 15.1) and duration of hospitalisation were similar in the two groups (mean difference (MD) 0.1, 95% CI ‐1.13 to 0.93) (Analysis 15.4).

15.1. Analysis.

Comparison 15 Ampicillin alone versus penicillin with chloramphenicol, Outcome 1 Cure rates.

15.4. Analysis.

Comparison 15 Ampicillin alone versus penicillin with chloramphenicol, Outcome 4 Duration of hospital stay.

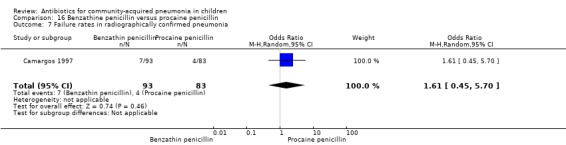

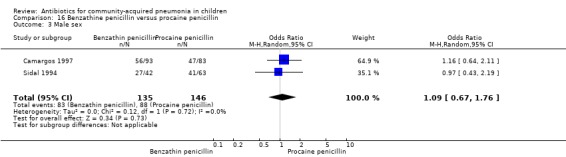

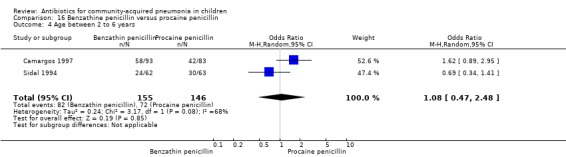

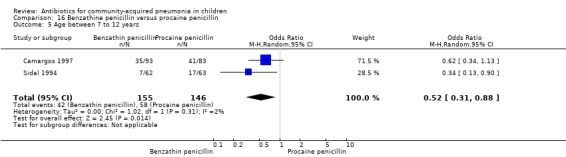

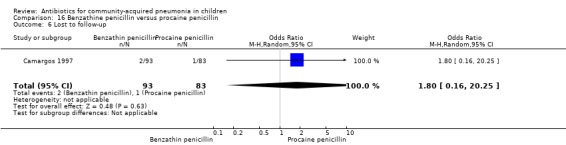

Benzathine penicillin versus procaine penicillin (Analysis 16)

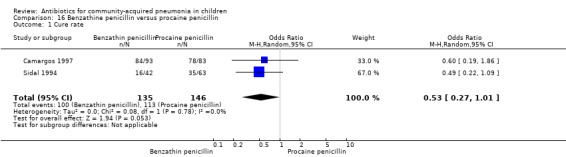

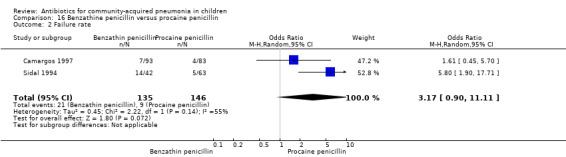

Two studies fulfilled the inclusion criteria; one which included 176 children between two and 12 years of age with chest X‐ray films showing lobar consolidation or infiltration (presumed streptococcal infection) (Camargos 1997) and another study of 105 children between three months and 14 years of age (Sidal 1994). Both studies were unblinded and allocation concealment was adequate in one (Camargos 1997). Cure rates were not significantly different in the two groups (OR 0.53, 95% CI 0.27 to 1.01) (Analysis 16.1). Failure rates were also similar between the groups (OR 3.17, 95% CI 0.9 to 11.11) (Analysis 16.2). Bacterial pathogens were identified in only one study. The isolation rate for S. pneumoniae was six out of 90 blood cultures performed (four participants in the benzathine group and two in the procaine penicillin group). The clinical outcome did not differ in relation to the organism identified.

16.1. Analysis.

Comparison 16 Benzathine penicillin versus procaine penicillin, Outcome 1 Cure rate.

16.2. Analysis.

Comparison 16 Benzathine penicillin versus procaine penicillin, Outcome 2 Failure rate.

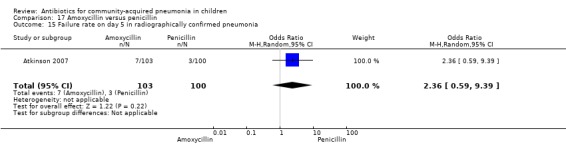

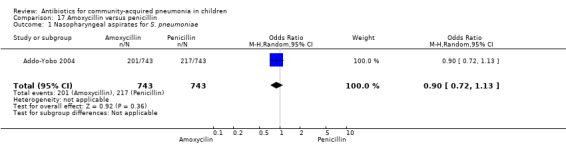

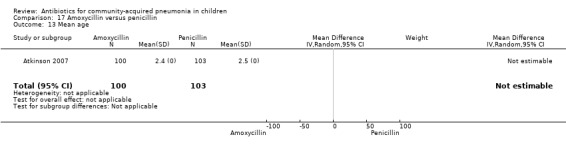

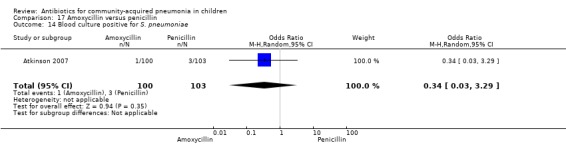

Amoxycillin versus penicillin (Analysis 17)

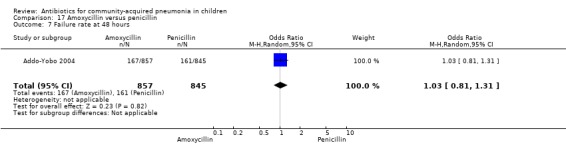

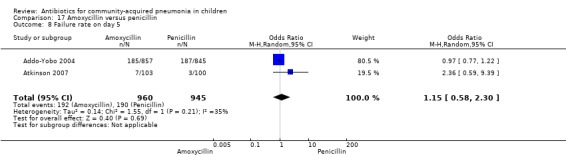

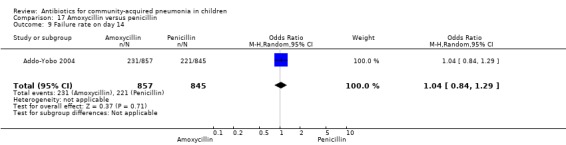

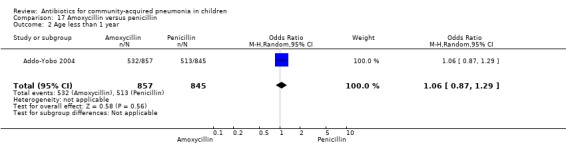

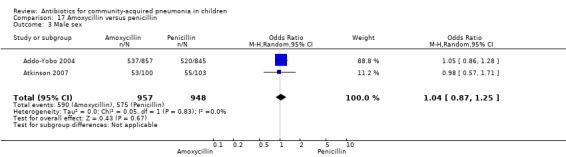

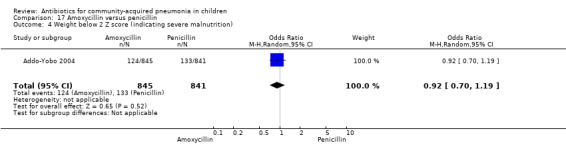

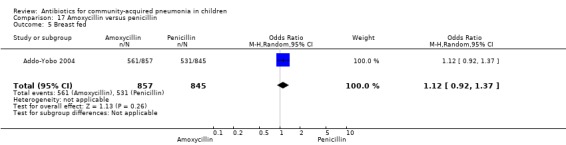

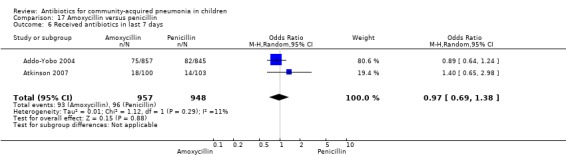

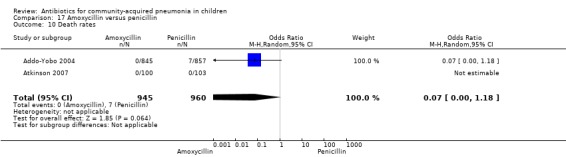

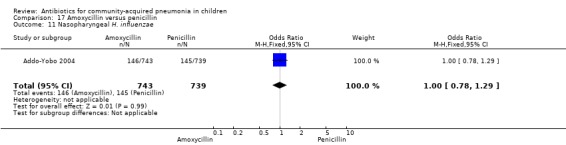

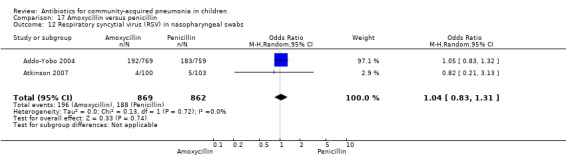

Two multicentre non‐blinded studies were identified; these enrolled 1702 children between three months and 59 months of age, suffering from severe pneumonia (diagnosed on the basis of WHO criteria) (Addo‐Yobo 2004) and 203 children with radiographically confirmed pneumonia (Atkinson 2007). The studies were unblinded and allocation concealment was adequate. The second study (Atkinson 2007) measured outcome as time from randomisation until the temperature was < 38 degrees celsius for 24 hours and oxygen requirement had ceased. However, it provided data on need for change of antibiotics due to worsening of respiratory/radiological findings. For the purposes of this analysis we considered them as failure on day five. Age, sex, severe malnutrition, breast feeding and the number of children who had received antibiotics in the last week were similar in both the groups. The failure rates measured at 48 hours (OR 1.03, 95% CI 0.81 to 1.31) (Analysis 17.7), five days (OR 1.15, 95% CI 0.58 to 2.30) (Analysis 17.8) and 14 days (OR 1.04, 95% CI 0.84 to 1.29) (Analysis 17.9) were similar in both groups. There were seven deaths in the group receiving penicillin in one study (Addo‐Yobo 2004) while no deaths were observed in the other study (Atkinson 2007).

17.7. Analysis.

Comparison 17 Amoxycillin versus penicillin, Outcome 7 Failure rate at 48 hours.

17.8. Analysis.

Comparison 17 Amoxycillin versus penicillin, Outcome 8 Failure rate on day 5.

17.9. Analysis.

Comparison 17 Amoxycillin versus penicillin, Outcome 9 Failure rate on day 14.

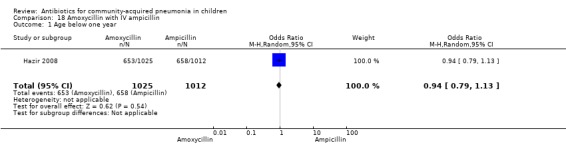

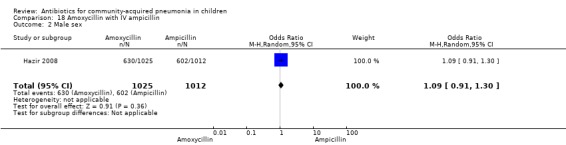

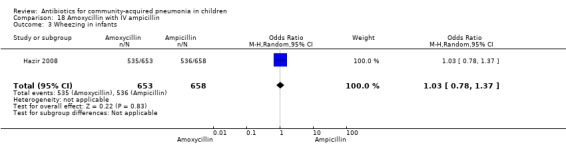

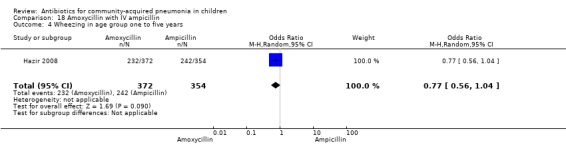

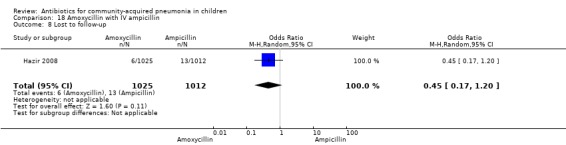

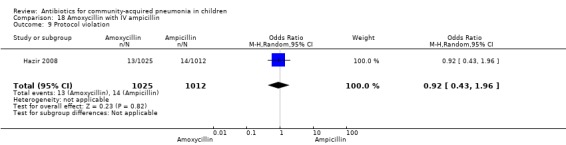

Amoxycillin with intravenous (IV) ampicillin (Analysis 18)

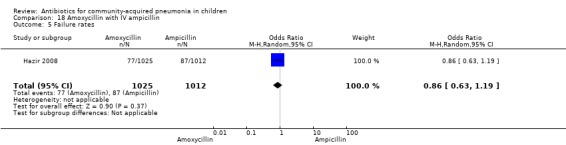

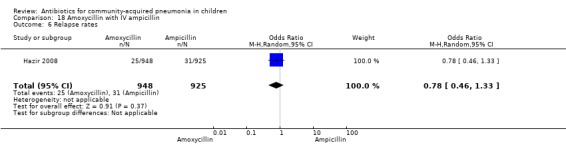

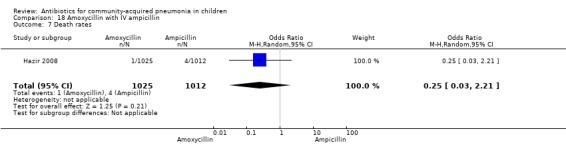

One non‐blinded study involving 237 children between two and 59 months of age with severe pneumonia was identified (Hazir 2008). Allocation concealment was adequate. Number of infants in each group, sex distribution and presence of wheeze were comparable in the two groups. Failure rates (OR 0.86, 95% CI 0.63 to 1.19) (Analysis 18.5), relapse rates (OR 0.78, 95% CI 0.46 to 1.33) (Analysis 18.6) and death rates (OR 0.25, 95% CI 0.03 to 2.21) (Analysis 18.7) were similar in the two groups.

18.5. Analysis.

Comparison 18 Amoxycillin with IV ampicillin, Outcome 5 Failure rates.

18.6. Analysis.

Comparison 18 Amoxycillin with IV ampicillin, Outcome 6 Relapse rates.

18.7. Analysis.

Comparison 18 Amoxycillin with IV ampicillin, Outcome 7 Death rates.

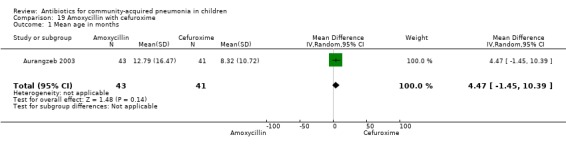

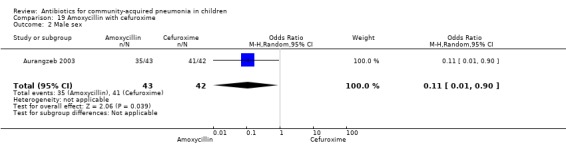

Amoxycillin with cefuroxime (Analysis 19)

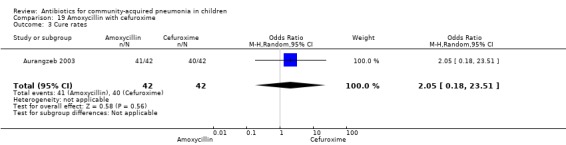

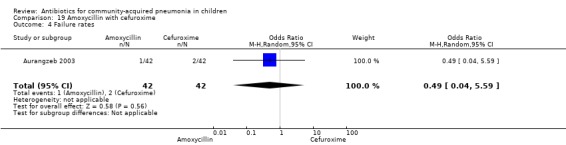

One randomised, non‐blinded controlled study was identified; this included 83 children with non‐severe and severe pneumonia (Aurangzeb 2003). Allocation concealment was unclear. Baseline data in the form of mean age and proportion of boys were similar in the two groups. Cure rates (OR 2.05, 95% CI 0.18 to 23.51) (Analysis 19.3) and failure rates (OR 0.49, 95% CI 0.04 to 5.59) (Analysis 19.4) were similar in the two groups.

19.3. Analysis.

Comparison 19 Amoxycillin with cefuroxime, Outcome 3 Cure rates.

19.4. Analysis.

Comparison 19 Amoxycillin with cefuroxime, Outcome 4 Failure rates.

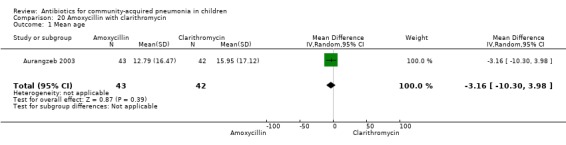

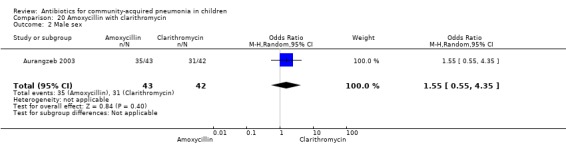

Amoxycillin with clarithromycin (Analysis 20)

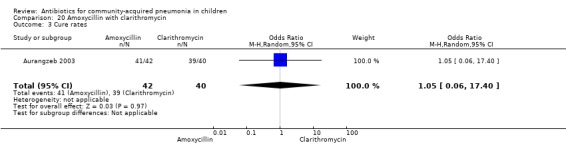

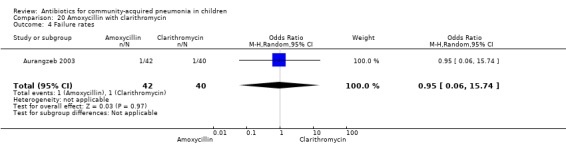

One randomised, non‐blinded controlled study compared these two drugs; 85 children with non‐severe and severe pneumonia were enrolled (Aurangzeb 2003). The sequence generation and allocation concealment in the study is not clear. Baseline data in the form of mean age and proportion of boys were similar in the two groups. Cure rates (OR 1.05, 95% CI 0.06 to 17.40) (Analysis 20.3) and failure rates (OR 0.95, 95% CI 0.06 to 15.74) (Analysis 20.4) were similar in the two groups.

20.3. Analysis.

Comparison 20 Amoxycillin with clarithromycin, Outcome 3 Cure rates.

20.4. Analysis.

Comparison 20 Amoxycillin with clarithromycin, Outcome 4 Failure rates.

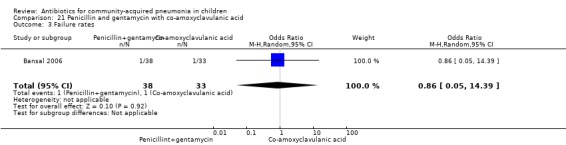

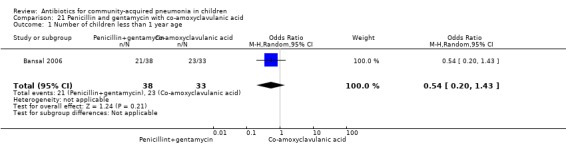

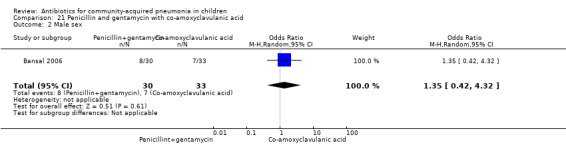

Penicillin and gentamycin with co‐amoxyclavulanic acid (Analysis 21)

One study involving 71 children between two months and 59 months of age with very severe pneumonia fulfilled the inclusion criteria (Bansal 2006). The study was non‐blinded and allocation concealment was adequate. Baseline characteristics, including number of infants and sex distribution, were comparable. Failure rates in the two groups were similar (OR 0.86, 95% CI 0.05 to 14.39) (Analysis 21.3).

21.3. Analysis.

Comparison 21 Penicillin and gentamycin with co‐amoxyclavulanic acid, Outcome 3 Failure rates.

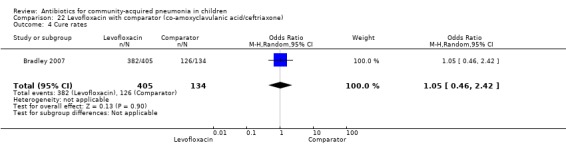

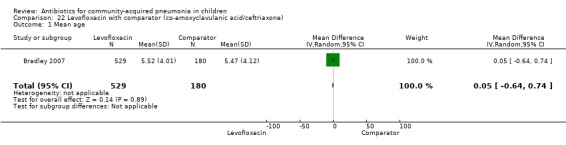

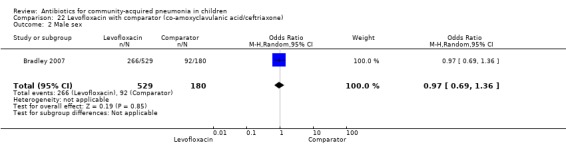

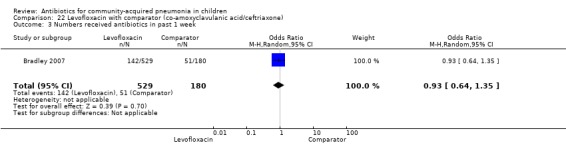

Levofloxacin with comparator group (Analysis 22)

One non‐blinded study, involving 709 children below 16 years of age, compared oral levofloxacin with either ceftriaxone or co‐amoxyclavulanic acid (Bradley 2007). Sequence generation and allocation concealment is not clear from the study. The mean age, sex and number who received antibiotics before enrolment were comparable in the two groups. Cure rates were similar in the two groups (OR 1.05, 95% CI 0.46 to 2.42) (Analysis 22.4).

22.4. Analysis.

Comparison 22 Levofloxacin with comparator (co‐amoxyclavulanic acid/ceftriaxone), Outcome 4 Cure rates.

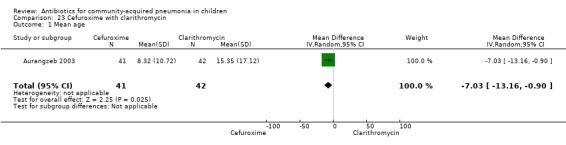

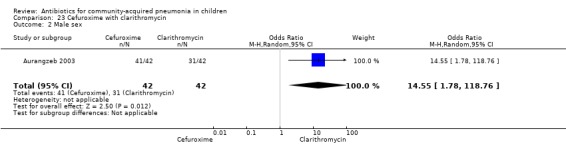

Cefuroxime with clarithromycin (Analysis 23)

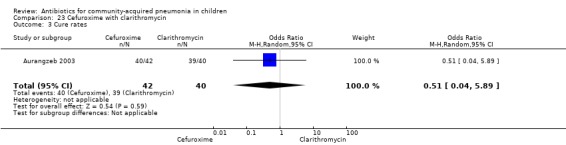

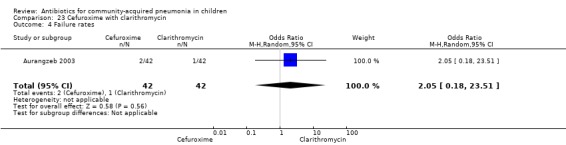

One randomised, non‐blinded, controlled study involving 85 children with non‐severe and severe pneumonia was identified (Aurangzeb 2003). Allocation concealment was unclear. Baseline data in the form of mean age and proportion of boys were similar in the two groups. Cure rates (OR 0.51, 95% CI 0.04 to 5.89) ( Analysis 23.3) and failure rates (OR 2.05, 95% CI 0.18 to 23.51) (Analysis 23.4) were similar in the two groups.

23.3. Analysis.

Comparison 23 Cefuroxime with clarithromycin, Outcome 3 Cure rates.

23.4. Analysis.

Comparison 23 Cefuroxime with clarithromycin, Outcome 4 Failure rates.

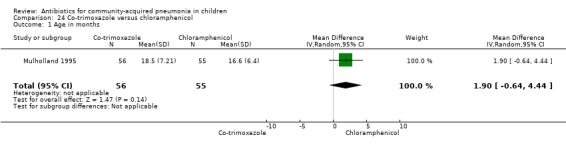

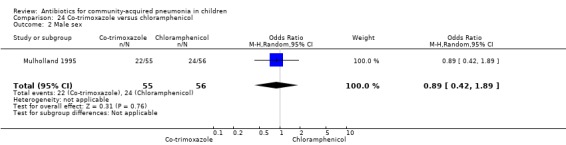

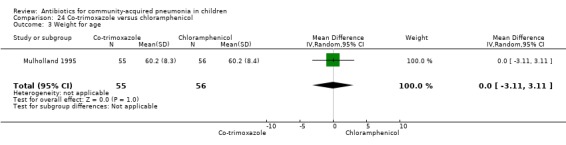

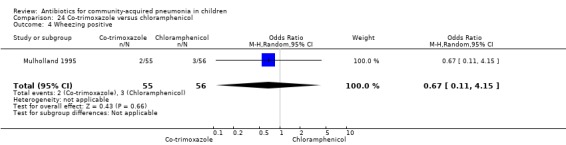

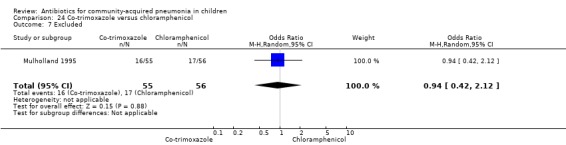

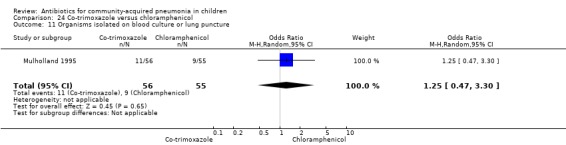

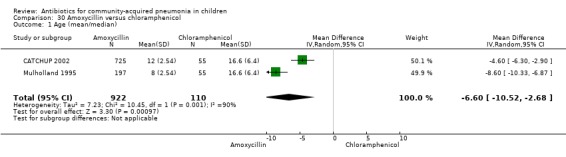

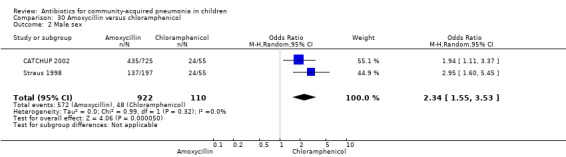

Co‐trimoxazole versus chloramphenicol (Analysis 24)

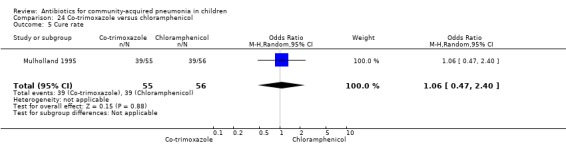

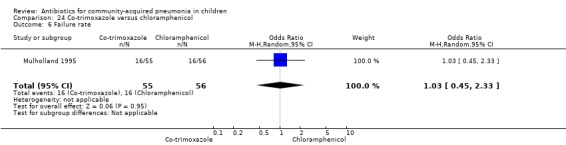

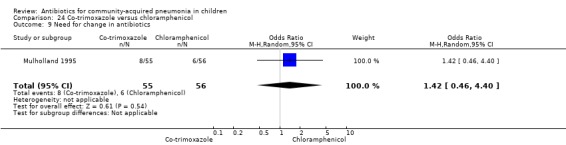

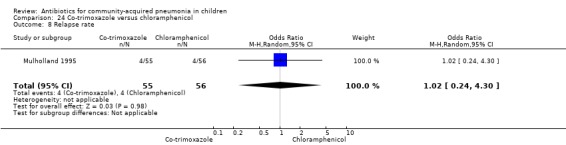

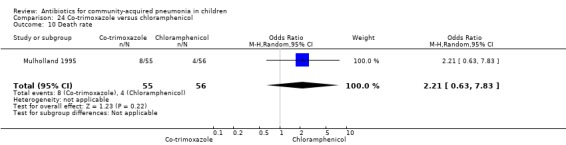

One double‐blind study involving 111 malnourished children under five years of age fulfilled the inclusion criteria for this review (Mulholland 1995). Allocation concealment was adequate. The age and sex distribution, nutritional status, children with wheezing and numbers excluded were similar in the two groups. Cure rates (OR 1.06, 95% CI 0.47 to 2.40) (Analysis 24.5), failure rates (OR 1.03, 95% CI 0.45 to 2.33) (Analysis 24.6), number of participants requiring a change in antibiotics (OR 1.42, 95% CI 0.46 to 4.40) (Analysis 24.9), relapse rates (OR 1.02, 95% CI 0.24 to 4.30) (Analysis 24.8) and death rates (OR 2.21, 95% CI 0.63 to 7.83) (Analysis 24.10) were similar in the two groups.

24.5. Analysis.

Comparison 24 Co‐trimoxazole versus chloramphenicol, Outcome 5 Cure rate.

24.6. Analysis.

Comparison 24 Co‐trimoxazole versus chloramphenicol, Outcome 6 Failure rate.

24.9. Analysis.

Comparison 24 Co‐trimoxazole versus chloramphenicol, Outcome 9 Need for change in antibiotics.

24.8. Analysis.

Comparison 24 Co‐trimoxazole versus chloramphenicol, Outcome 8 Relapse rate.

24.10. Analysis.

Comparison 24 Co‐trimoxazole versus chloramphenicol, Outcome 10 Death rate.

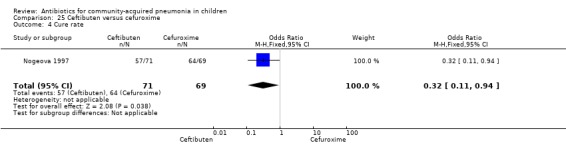

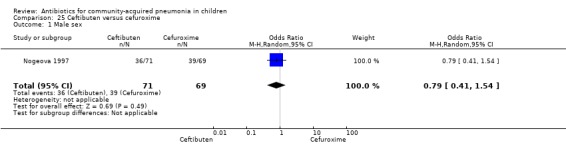

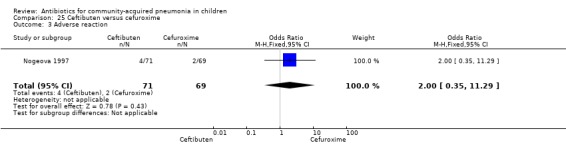

Ceftibuten with cefuroxime axetil (Analysis 25)

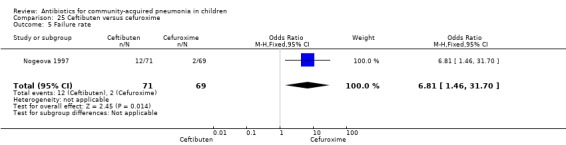

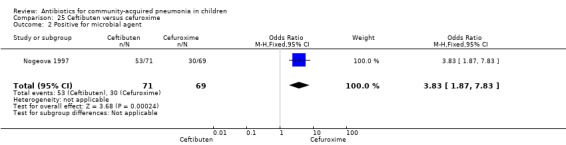

One study involving 140 children between one and 12 years of age with radiographically confirmed CAP compared ceftibuten with cefuroxime axetil (Nogeova 1997). The study was unblinded. Sequence generation and allocation concealment were not clear from the paper. Age and sex distribution were similar in the two groups. Cure rate (OR 0.32 95% CI 0.11 to 0.94) (Analysis 25.4) was significantly higher and failure rate (OR 6.81, 95% CI 1.46 to 31.70) (Analysis 25.5) was significantly lower in children receiving cefuroxime. Organisms were isolated in 83 participants (53 in the ceftibuten group and 30 in the cefuroxime group). Identification of organisms was significantly higher in children who received ceftibuten (OR 3.83, 95% CI 1.87 to 7.83) (Analysis 25.2). Organisms identified in children who received ceftibuten were S. pneumoniae (17), H. influenzae (13), Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus) (eight), group A beta haemolytic streptococcus (seven), Moraxella catarrhalis (M. catarrhalis) (four), respiratory syncytial virus (onr) and Mycoplasma pneumoniae (M. pneumoniae) (one). The organisms identified in children receiving cefuroxime axetil were: S. pneumoniae (seven), H. influenzae (eight), S. aureus (three), group A beta haemolytic streptococcus (four), Moraxella catarrhalis (seven), respiratory syncytial virus (three) and M. pneumoniae (three).

25.4. Analysis.

Comparison 25 Ceftibuten versus cefuroxime, Outcome 4 Cure rate.

25.5. Analysis.

Comparison 25 Ceftibuten versus cefuroxime, Outcome 5 Failure rate.

25.2. Analysis.

Comparison 25 Ceftibuten versus cefuroxime, Outcome 2 Positive for microbial agent.

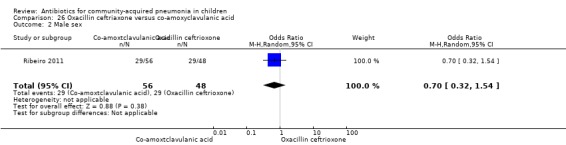

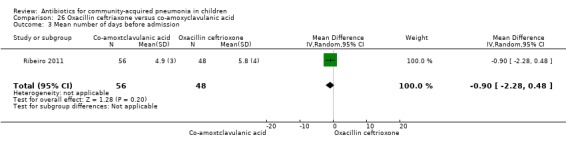

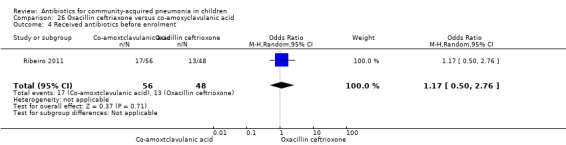

Oxacillin/ceftriaxone with co‐amoxyclavulanic acid (Analysis 26)

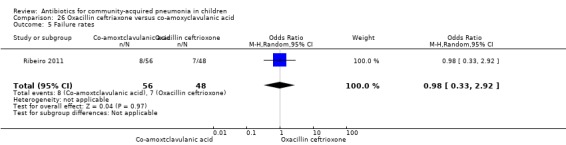

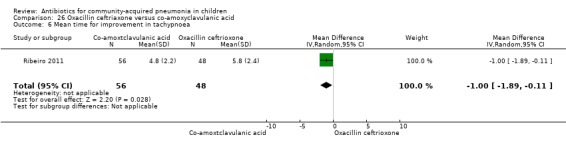

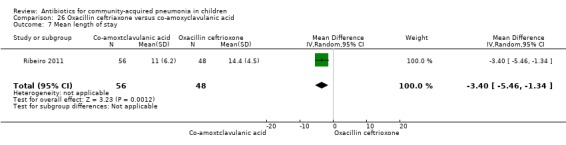

One study involving 104 children aged between two months to five years with very severe pneumonia was included (Ribeiro 2011). The study was unblinded; random sequence generation, allocation concealment and reporting of data were adequate. Age and sex distribution, days before admission in hospital, receipt of antibiotics before enrolment and failure rates (OR 0.98, 95% CI 0.33 to 2.92) (Analysis 26.5) were similar in the two groups of participants. Mean time for improvement (MD ‐1.00 day, 95% CI ‐1.89 to ‐0.11) (Analysis 26.6) and total hospital stay (MD ‐3.40 days, 95% CI ‐5.46 to ‐1.34) (Analysis 26.7) were significantly better in children receiving co‐amoxyclavulanic acid.

26.5. Analysis.

Comparison 26 Oxacillin ceftriaxone versus co‐amoxyclavulanic acid, Outcome 5 Failure rates.

26.6. Analysis.

Comparison 26 Oxacillin ceftriaxone versus co‐amoxyclavulanic acid, Outcome 6 Mean time for improvement in tachypnoea.

26.7. Analysis.

Comparison 26 Oxacillin ceftriaxone versus co‐amoxyclavulanic acid, Outcome 7 Mean length of stay.

Antibiotics in radiographically confirmed pneumonia

Out of 29 studies, 12 (Atkinson 2007; Bansal 2006; Block 1995; Bradley 2007; Camargos 1997; Deivanayagam 1996; Klein 1995; Kogan 2003; Mulholland 1995; Nogeova 1997; Wubbel 1999; Tsarouhas 1998) enrolled children with radiographically confirmed pneumonia. Ten studies (Addo‐Yobo 2004; Asghar 2008; Awasthi 2008; Campbell 1988; CATCHUP 2002; Cetinkaya 2004; Duke 2002; Hazir 2008; Shann 1985; Straus 1998) used clinical criteria to diagnose pneumonia. Three studies (Harris 1998; Ribeiro 2011; Roord 1996) used clinical criteria or radiography for diagnosis of pneumonia. In four studies (Aurangzeb 2003; Jibril 1989; Keeley 1990; Sidal 1994) the role of radiography in the diagnosis of pneumonia was not clear from the description. The following comparisons were carried out in radiographically confirmed pneumonia.

Azithromycin versus erythromycin (Analysis 1)

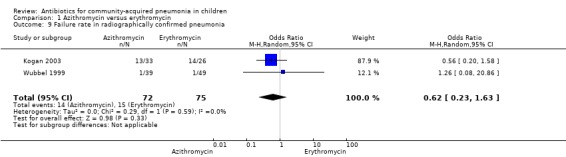

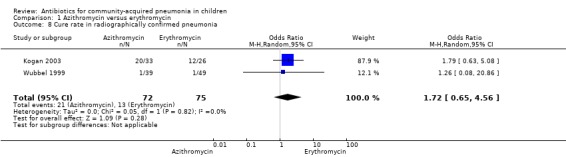

Out of four studies (Harris 1998; Kogan 2003; Roord 1996; Wubbel 1999), radiographs were performed for diagnosis of pneumonia in only two studies (Kogan 2003; Wubbel 1999). A total of 147 children were enrolled in these two studies. Failure rates (OR 0.62, 95% CI 0.23 to 1.63) (Analysis 1.9) and cure rates (OR 1.72, 95% CI 0.65 to 4.56) (Analysis 1.8) were not different in the two groups.

1.9. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Azithromycin versus erythromycin, Outcome 9 Failure rate in radiographically confirmed pneumonia.

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Azithromycin versus erythromycin, Outcome 8 Cure rate in radiographically confirmed pneumonia.

Clarithromycin versus erythromycin (Analysis 2)

One study (Block 1995) compared erythromycin and clarithromycin; 234 children below 15 years of age with radiographically confirmed pneumonia were treated on in an ambulatory setting. Resolution of pneumonia (diagnosed radiologically) was more frequent in the clarithromycin group compared to the erythromycin group (OR 2.51, 95% CI 1.02 to 6.16) (Analysis 2.6). However, there were no differences in radiologic cure rates (OR 3.55, 95% CI 0.7 to 18.04) (Analysis 2.7) or radiologic failure rates (OR 0.34, 95% CI 0.06 to 1.80) (Analysis 2.8).

Erythromycin versus co‐amoxyclavulanic acid (Analysis 3)

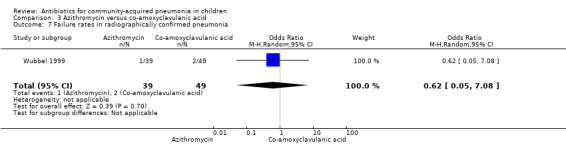

Out of two studies (Harris 1998; Wubbel 1999), one study (Wubbel 1999) involving 88 children enrolled participants with radiographically confirmed pneumonia. Failure rates were similar in the two groups (OR 0.62, 95% CI 0.05 to 7.08) (Analysis 3.7)

3.7. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Azithromycin versus co‐amoxyclavulanic acid, Outcome 7 Failure rates in radiographically confirmed pneumonia.

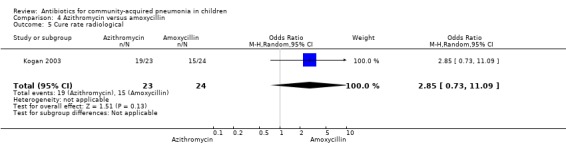

Azithromycin versus amoxycillin (Analysis 4)

One study involving 47 children aged between one month and 14 years with radiographically confirmed pneumonia compared azithromycin and amoxycillin (Kogan 2003). Children treated with azithromycin were older than those treated with amoxycillin (OR 58.1, 95% CI 35.59 to 80.61) (Analysis 4.1). Cure rates were not significantly different in the two groups (OR 2.85, 95% CI 0.73 to 11.09) (Analysis 4.5).

4.1. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Azithromycin versus amoxycillin, Outcome 1 Age in months.

4.5. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Azithromycin versus amoxycillin, Outcome 5 Cure rate radiological.

Amoxycillin versus procaine penicillin (Analysis 5)

One study involving 170 children with radiographically confirmed pneumonia, aged six months to 18 years, was identified (Tsarouhas 1998). The failure rates were similar in the two groups (OR 0.75, 95% CI 0.17 to 3.25) (Analysis 5.2).

Cefpodoxime versus co‐amoxyclavulanic acid (Analysis 10)

One multicentre study (Klein 1995) enrolled 348 children with radiographically confirmed pneumonia aged three months to 11.5 years of age. Cure rates in the two groups were similar (OR 0.69, 95% CI 0.18 to 2.60) (Analysis 10.1).

Studies comparing treatment of hospitalised children with severe/very severe pneumonia

Ampicillin alone versus penicillin with chloramphenicol (Analysis 15)

One trial involving 115 children with radiographically confirmed pneumonia, between five months and four years of age, was identified (Deivanayagam 1996). The study was unblinded and allocation concealment was adequate. The cure rates (OR 0.48, 95% CI 0.15 to 1.51) (Analysis 15.1) and duration of hospitalisation were similar in the two groups (MD 0.1, 95% CI ‐1.13 to 0.93) (Analysis 15.4).

Benzathine penicillin versus procaine penicillin (Analysis 16)

Out of two studies, radiographically confirmed pneumonia was only assessed in one study which included 176 children between two and 12 years of age with chest X‐ray films showing lobar consolidation or infiltration (presumed streptococcal infection) (Camargos 1997). Failure rates were similar between the groups (OR 1.61, 95% CI 0.45 to 5.70) (Analysis 16.7).

16.7. Analysis.

Comparison 16 Benzathine penicillin versus procaine penicillin, Outcome 7 Failure rates in radiographically confirmed pneumonia.

Amoxycillin versus penicillin (Analysis 17)

Out of two studies, children with radiographically confirmed pneumonia were enrolled in one study involving 203 children (Atkinson 2007). The failure rate on day five was similar in the two groups (OR 2.36, 95% CI 0.59 to 9.39) (Analysis 17.15).

17.15. Analysis.

Comparison 17 Amoxycillin versus penicillin, Outcome 15 Failure rate on day 5 in radiographically confirmed pneumonia.

Penicillin and gentamycin with co‐amoxyclavulanic acid (Analysis 21)

One study involving 71 children between two months and 59 months of age with very severe, radiographically confirmed pneumonia fulfilled the inclusion criteria (Bansal 2006). Failure rates in the two groups were similar (OR 0.86, 95% CI 0.05 to 14.39) (Analysis 21.3).

Levofloxacin with comparator group (Analysis 22)

One non‐blinded study, involving 709 children below 16 years of age, compared oral levofloxacin with either ceftriaxone or co‐amoxyclavulanic acid (Bradley 2007). The sequence generation and allocation concealment were not clear from the study. The mean age, sex and number who received antibiotics before enrolment were comparable in the two groups. Cure rates were similar in the two groups (OR 1.05, 95% CI 0.46 to 2.42) (Analysis 22.4).

Co‐trimoxazole versus chloramphenicol (Analysis 24)

One double‐blind study involving 111 malnourished children with radiographically confirmed pneumonia under five years of age fulfilled the inclusion criteria for this review (Mulholland 1995). Cure rates (OR 1.06, 95% CI 0.47 to 2.40) (Analysis 24.5), failure rates (OR 1.03, 95% CI 0.45 to 2.33) (Analysis 24.6), number of participants requiring a change in antibiotics (OR 1.42, 95% CI 0.46 to 4.40) (Analysis 24.9), relapse rates (OR 1.02, 95% CI 0.24 to 4.30) (Analysis 24.8) and death rates (OR 2.21, 95% CI 0.63 to 7.83) (Analysis 24.10) were similar in the two groups.

Ceftibuten with cefuroxime axetil (Analysis 25)

One study (Nogeova 1997) involved 140 children between one and 12 years of age with radiographically confirmed CAP. Cure rate (OR 0.32, 95% CI 0.11 to 0.94) (Analysis 25.4) and failure rate (OR 6.81, 95% CI 1.46 to 31.70) (Analysis 25.5) were significantly better in the children receiving cefuroxime.

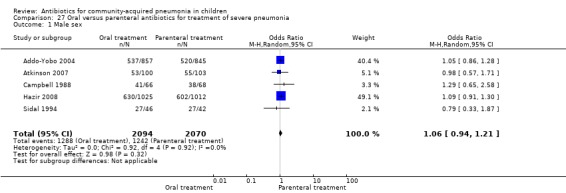

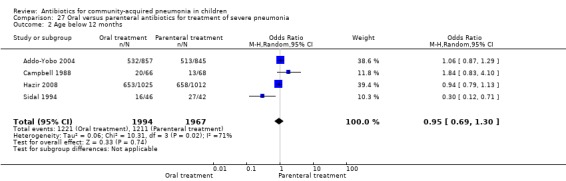

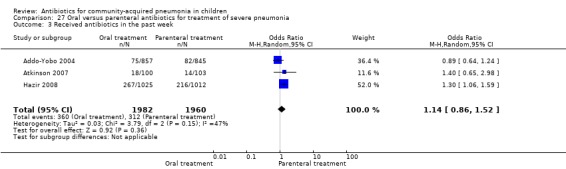

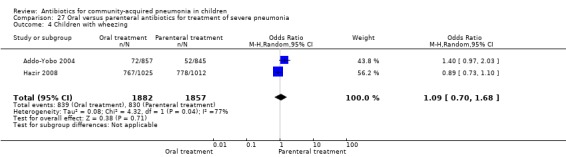

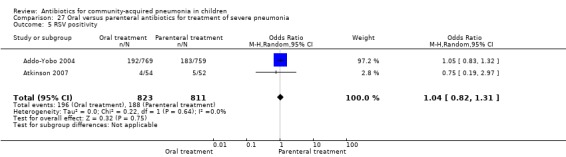

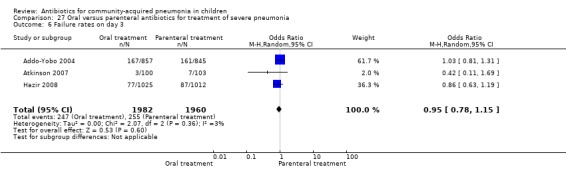

Oral treatment of severe pneumonia with parenteral treatment (Analysis 27)

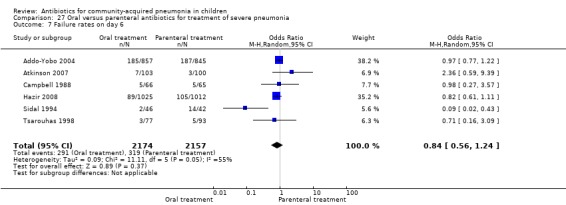

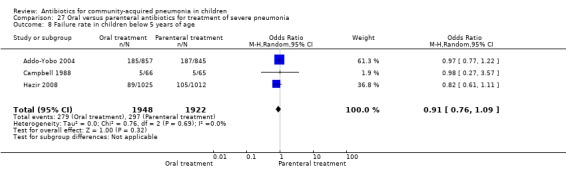

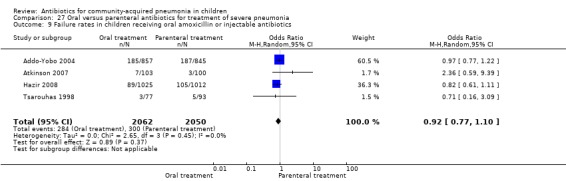

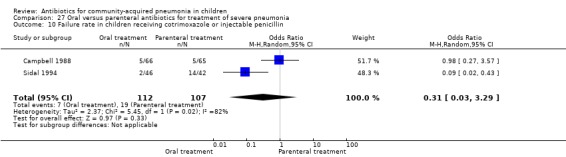

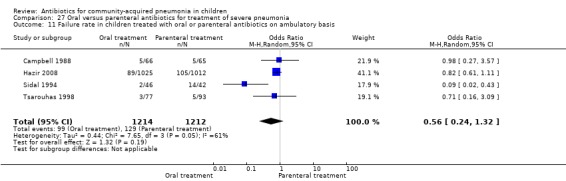

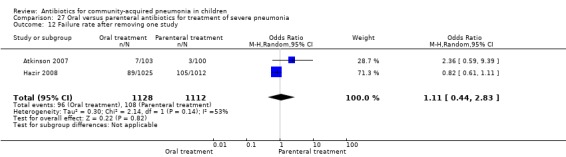

There were six studies (Addo‐Yobo 2004; Atkinson 2007; Campbell 1988; Hazir 2008; Sidal 1994; Tsarouhas 1998) that included children with severe pneumonia and compared oral antimicrobial agents with initial intravenous or intramuscular medications. Four studies compared oral amoxycillin with intravenous penicillin/ampicillin (Addo‐Yobo 2004; Atkinson 2007; Hazir 2008; Tsarouhas 1998). Two studies compared oral cotrimoxazole with intramuscular penicillin (Campbell 1988; Sidal 1994). In four studies (Campbell 1988; Hazir 2008; Sidal 1994; Tsarouhas 1998) children were treated in an ambulatory setting with injections as well as oral medications. A total of 4331 children below 18 years of age were enrolled; 2174 received oral antibiotics (cotrimoxazole or amoxycillin) and 2157 received intravenous or intramuscular antibiotics (penicillin or ampicillin). The baseline characteristics (age and sex distribution) in the two groups and proportion of children who had received antibiotics before enrolment were comparable in the two groups. Failure rates were similar in the two groups (OR 0.84, 95% CI 0.56 to 1.24) (Analysis 27.7). Separate data for children below five years of age were not available. We re‐analysed data after removing studies that also enrolled children above five years of age (Atkinson 2007; Sidal 1994; Tsarouhas 1998). Failure rates were similar in the two groups (OR 0.91, 95% CI 0.76 to 1.09) (Analysis 27.8). Failure rates did not show significant differences when children receiving amoxycillin (OR 0.92, 95% CI 0.77 to 1.10) (Analysis 27.9) or cotrimoxazole (OR 0.31, 95% CI 0.03 to 3.29) (Analysis 27.10) were analysed separately.

27.7. Analysis.

Comparison 27 Oral versus parenteral antibiotics for treatment of severe pneumonia, Outcome 7 Failure rates on day 6.

27.8. Analysis.

Comparison 27 Oral versus parenteral antibiotics for treatment of severe pneumonia, Outcome 8 Failure rate in children below 5 years of age.

27.9. Analysis.

Comparison 27 Oral versus parenteral antibiotics for treatment of severe pneumonia, Outcome 9 Failure rates in children receiving oral amoxicillin or injectable antibiotics.

27.10. Analysis.

Comparison 27 Oral versus parenteral antibiotics for treatment of severe pneumonia, Outcome 10 Failure rate in children receiving cotrimoxazole or injectable penicillin.

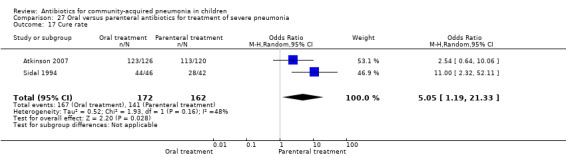

Analysis of studies that treated both the groups in an ambulatory setting (after removing studies that gave both the treatments in hospital) showed that failure rates in the two groups were not different (OR 0.92, 95% CI 0.77 to 1.10) (Analysis 27.9). Cure rates were available in two studies (Atkinson 2007; Sidal 1994) and were significantly better in children receiving oral antibiotics (OR 5.05, 95% CI 1.19 to 21.33).

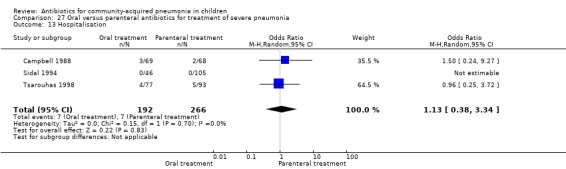

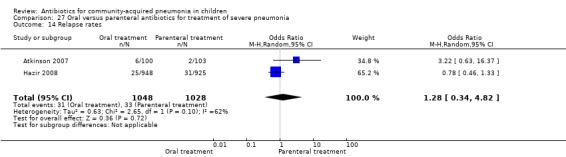

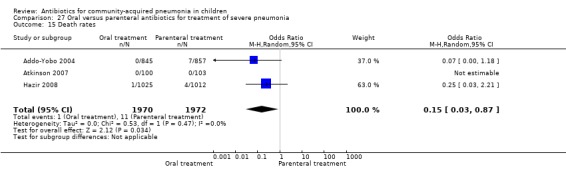

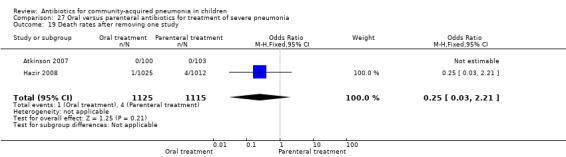

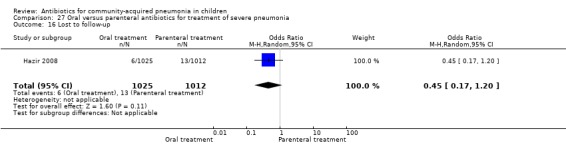

Hospitalisation rate in children receiving treatment in an ambulatory setting was available in three studies (Campbell 1988; Sidal 1994; Tsarouhas 1998). The need for hospitalisation was similar in the two groups (OR 1.13, 95% CI 0.38, 3.34) (Analysis 27.13). Relapse rates were available in two studies (Atkinson 2007; Hazir 2008) and there was no significant difference in the two groups (OR 1.28, 95% CI 0.34 to 4.82) (Analysis 27.14). Death rate was available in three studies (Addo‐Yobo 2004; Atkinson 2007; Hazir 2008) and was significantly higher in those who received injectable treatments (OR 0.15, 95% CI 0.03 to 0.87) (Analysis 27.15). There were no deaths in one study (Atkinson 2007) and seven deaths in another study (but only in those receiving intravenous penicillin (Addo‐Yobo 2004)) and five deaths in the third study (one in the oral group and four in the intravenous ampicillin group) (Hazir 2008). Re‐analysis after removing one study with seven deaths in only one group (Addo‐Yobo 2004) suggests no significant difference between the two groups (OR 0.25, 95% CI 0.03, 2.21) (Analysis 27.19). Data on loss to follow‐up were available in one study (Hazir 2008) and were similar in the two groups (OR 0.45, 95% CI 0.17 to 1.20) (Analysis 27.16).

27.13. Analysis.

Comparison 27 Oral versus parenteral antibiotics for treatment of severe pneumonia, Outcome 13 Hospitalisation.

27.14. Analysis.

Comparison 27 Oral versus parenteral antibiotics for treatment of severe pneumonia, Outcome 14 Relapse rates.

27.15. Analysis.

Comparison 27 Oral versus parenteral antibiotics for treatment of severe pneumonia, Outcome 15 Death rates.

27.19. Analysis.

Comparison 27 Oral versus parenteral antibiotics for treatment of severe pneumonia, Outcome 19 Death rates after removing one study.

27.16. Analysis.

Comparison 27 Oral versus parenteral antibiotics for treatment of severe pneumonia, Outcome 16 Lost to follow‐up.

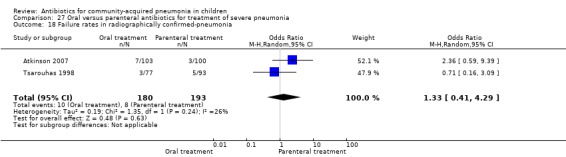

Only two studies (Atkinson 2007; Tsarouhas 1998) enrolled children with radiographically confirmed pneumonia. A total of 373 children were enrolled. The failure rates were similar in the two groups (OR 1.33, 95% CI 0.41 to 4.29) (Analysis 27.18).

27.18. Analysis.

Comparison 27 Oral versus parenteral antibiotics for treatment of severe pneumonia, Outcome 18 Failure rates in radiographically confirmed‐pneumonia.

Identification of aetiological agents

Out of 29 studies reviewed, attempts were made to isolate or demonstrate the aetiological organisms in 14 studies. The methods used in these studies for identification of bacteria were a blood culture, sputum examination or urinary antigen detection. For this review, results of a throat swab for bacterial isolation were ignored. Bacterial pathogens could be identified in blood cultures or serology/sputum in 591 (12%) out of 4882 participants tested. Out of the bacterial pathogens identified, 236 (40%) participants had S. pneumoniae, 150 (25%) had H. influenzae, 69 (12%) had S. aureus and 136 (23%) had other pathogens including the gram‐negative bacilli M. catarrhalis and Staphylococcus albus (S. albus) and Group A beta haemolytic streptococcus (Table 1).

1. Bacterial isolation.

| Study/total tested | S. pneumoniae | H. influenzae | Staphylococcus | Others |

| Asghar 2008/958 | 22 | 8 | 47 | 33 |

| Bansal 2006/71 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Block 1995/122 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Bradley 2007/709 | 21 | 7 | 0 | 3 |

| Camargos 1997/90 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Duke 2002/1116 | 4 | 10 | 10 | 36 |

| Harris 1998/351 | 5 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Klein 1995/348 | 14 | 28 | 0 | 17 |

| Kogan 2003/47 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 4 |

| Mulholland 1995/111 | 10 | 2 | 0 | 8 |

| Nogeova 1997/140 | 24 | 21 | 11 | 22 |

| Roord 1996/95 | 11 | 19 | 1 | 13 |

| Straus 1998/595 | 79 | 49 | 0 | 0 |

| Wubbel 1999/129 | 35 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Total/4882 (12%) | 236 (4.8%) | 150 (3.0%) | 69 (1.4%) | 136 (2.8%) |

| Out of total bacterial isolates (591) | 236/591 (40%) | 150/591 (25%) | 69/591 (12%) | 136/591 (23%) |

Information regarding the sensitivity pattern of bacterial isolates was available in four studies (Asghar 2008; Bansal 2006; Mulholland 1995; Roord 1996). This information was only available for the antibiotics studied and sensitivity was not tested in all the isolates. In the study by Asghar 2008, out of a total of 22 S. pneumoniae isolates, 13/14 were sensitive to chloramphenicol, 12/17 to gentamycin, 15/16 to ampicillin and 12/12 to third‐generation cephalosporins.

Out of a total of eight isolates of H. influenzae, 6/7 were sensitive to chloramphenicol, 12/17 to gentamicin, 15/16 to ampicillin and 6/6 to third‐generation cephalosporins.

Out of a total of 47 isolates of S. aureus, 19/37 were sensitive to chloramphenicol, 29/45 to gentamycin, 15/16 to ampicillin and 6/6 to third‐generation cephalosporins.

In the study by Bansal 2006, all the three isolates of S. pneumoniae were sensitive to penicillin, amoxycillin, erythromycin and gentamycin. However, out of two isolates of H. influenzae, one was sensitive and the other isolate was resistant to penicillin, amoxycillin, erythromycin and gentamycin. The one that was resistant was sensitive to ciprofloxacin, cefotaxime and chloramphenicol. In the study by Mulholland 1995, all 10 isolates of S. pneumoniae were susceptible to co‐trimoxazole and nine of these were also susceptible to chloramphenicol. All three Salmonella spp. isolates were susceptible to co‐trimoxazole and chloramphenicol. A single isolate of H. influenzae was resistant to co‐trimoxazole. In the study by Roord (Roord 1996), all 20 isolates were sensitive to azithromycin while three organisms were resistant to erythromycin.

Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) was tested in five studies. Nasopharyngeal aspirates were tested for RSV in four studies (Atkinson 2007; Addo‐Yobo 2004; Mulholland 1995; Wubbel 1999) involving 1916 children and RSV was identified by positive serology in one study (Nogeova 1997) involving 140 children. RSV was identified in 407 children (20%).

Identification of atypical organisms was attempted in six studies (Block 1995; Bradley 2007; Harris 1998; Kogan 2003; Nogeova 1997; Wubbel 1999). Out of the 1734 participants tested for M. pneumoniae, 385 (22%) tested positive. In participants aged under five years 141 out of 659 (21%) tested positive for mycoplasma. Tests for Chlamydia spp. were positive in 158 out of 1534 (10%) participants. In children under five years, there were positive test results for Chlamydia spp. in 45 out of 658 (7%) participants.

Indirect comparisons